Chromium Concentrate Recovery from Solid Tannery Waste in a Thermal Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

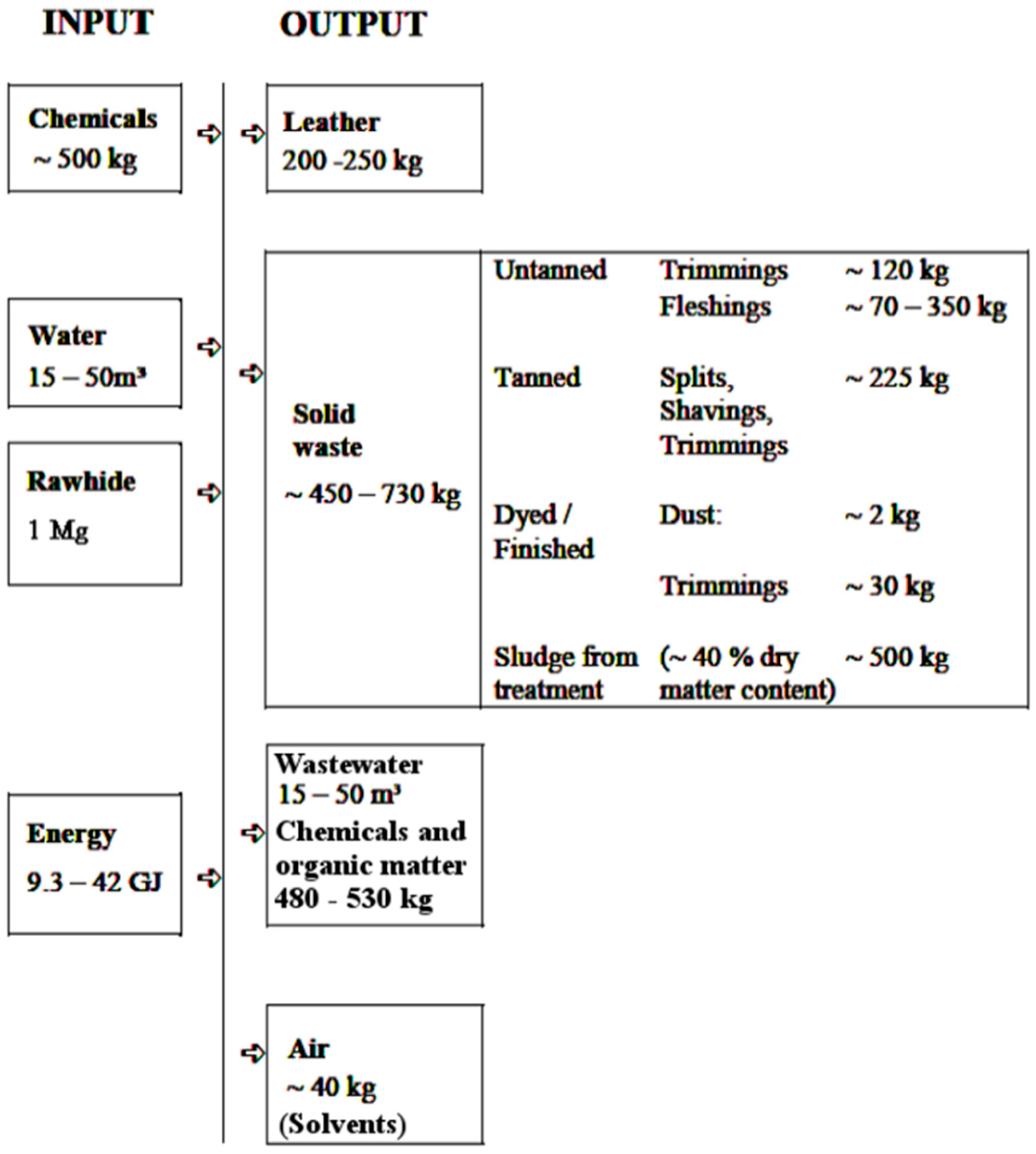

- Untanned solid tannery waste (USTW), such as trimmings (unused pieces of hides) or fleshings (non-leather tissues that have been mechanically scraped off). This waste is prone to biologically-mediated decay.

- Tanned solid tannery waste (TSTW), generated in the operations conducted during or after the proper tanning process, i.e., leather trimmings, splits, shavings and dust. These types of waste are as biologically stable as the leather itself, as they contain the same tanning agent compounds in their inner structure.

- Tannery sludge (TS) obtained as a result of process wastewater treatment. TS contains organic matter leached from hides/leather in tanning operations, as well as excess chemicals used throughout the whole tanning process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

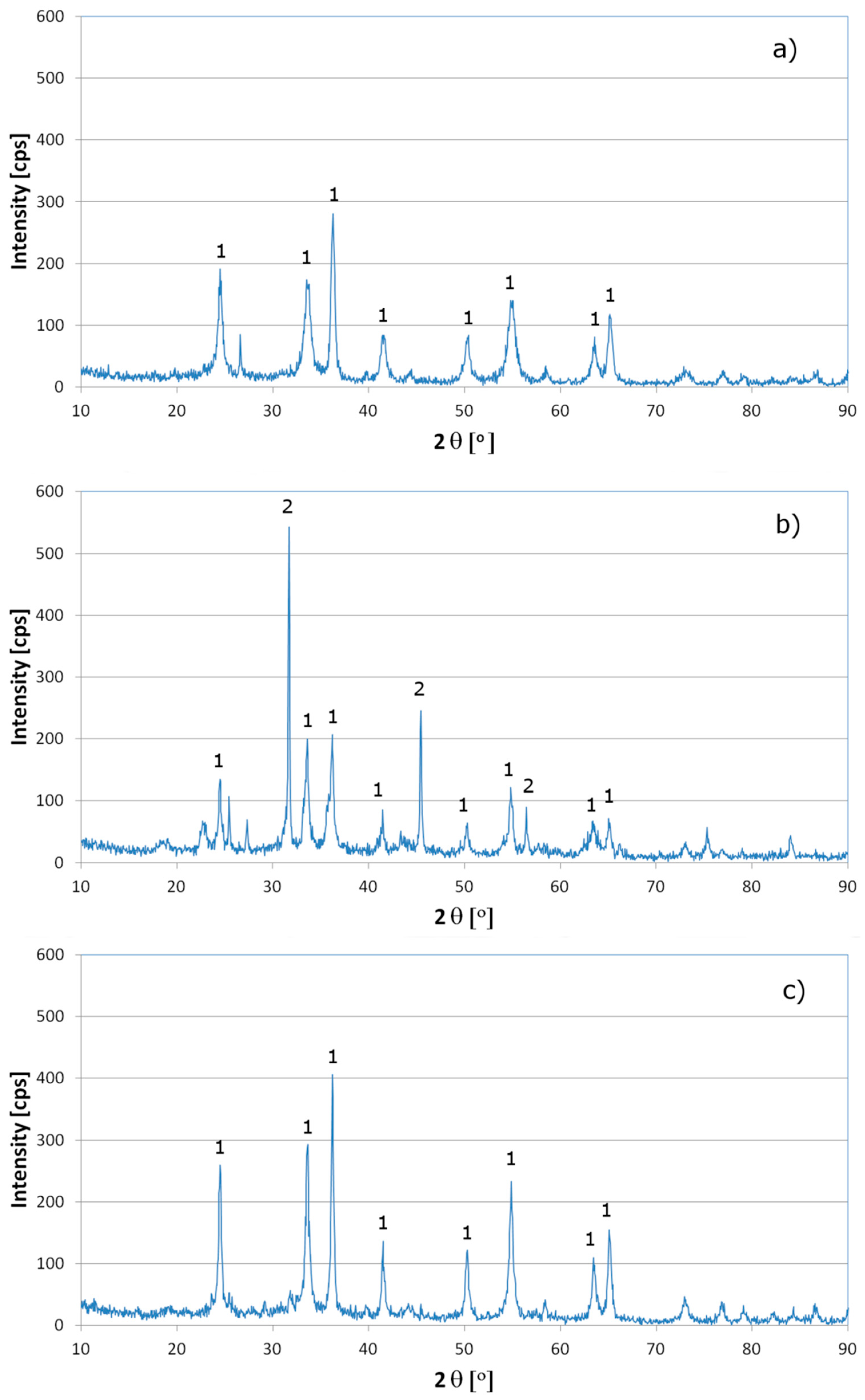

- (1)

- tanned trimmings (lower heating value (LHV) approx. 17,900 kJ·kg−1; MC approx. 10%(w/w));

- (2)

- shavings (LHV approx. 9100 kJ·kg−1; MC approx. 41%(w/w));

- (3)

- mixture of leather trimmings, shavings and buffing dust, in a weight ratio of 2:2:1 (LHV approx. 14,100 kJ·kg−1; MC approx. 23%(w/w)).

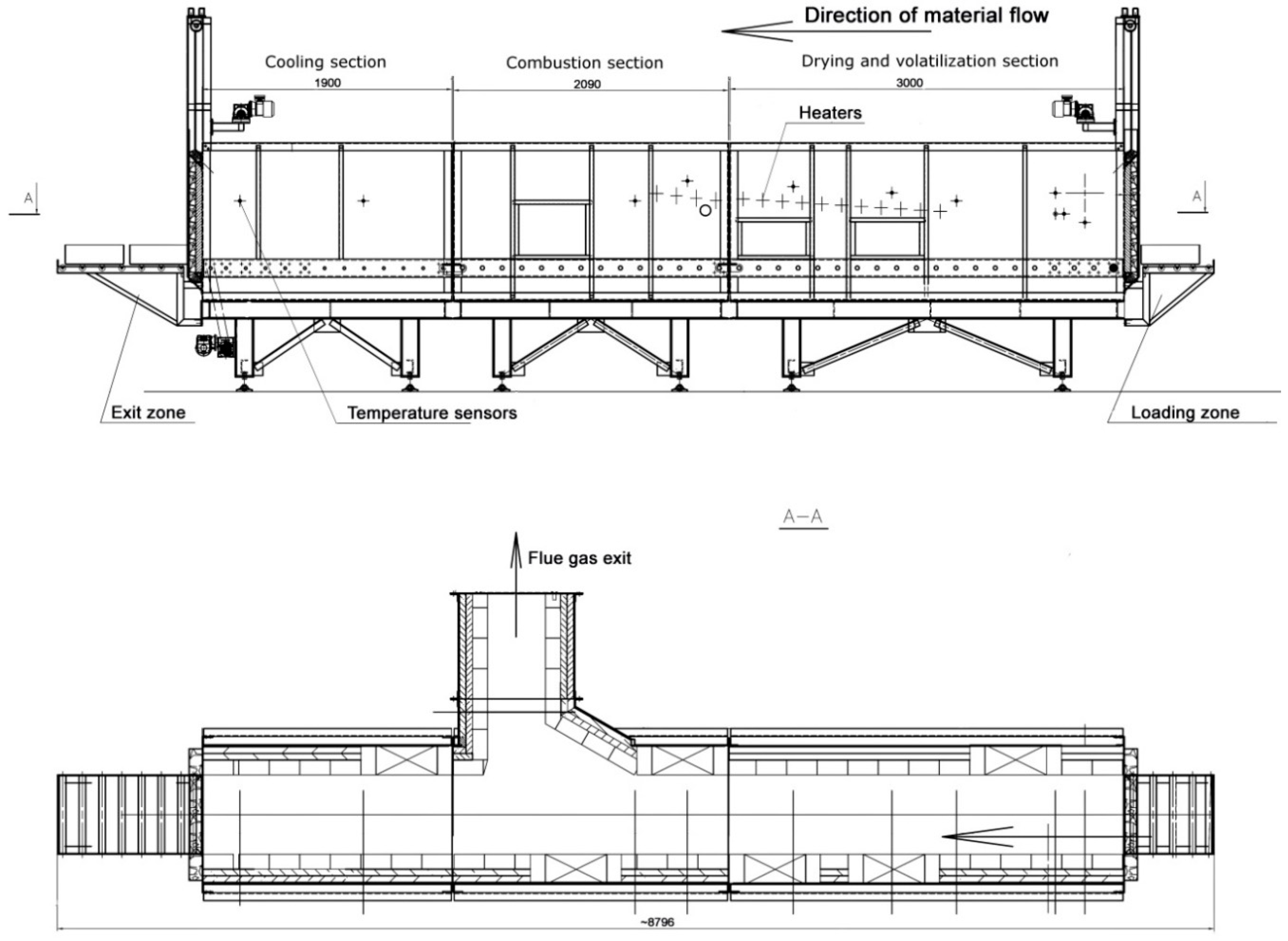

2.2. The Experimental Installation

2.3. Process Conditions

2.4. Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fela, K.; Wieczorek-Ciurowa, K.; Konopka, M.; Wozny, Z. Present and prospective leather industry waste disposal. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 2011, 13, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, J.; Senthilvelan, T.; Panda, R.C.; Kavitha, S. Eco-friendly waste management strategies for greener environment towards sustainable development in leather industry: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 89, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famielec, S.; Wieczorek-Ciurowa, K. Waste from leather industry—Threats to the environment. Technol. Trans. Chem. 2011, 1, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, J.; Han, W. The status and developments of leather solid waste treatment: A mini-review. Waste Manag. Res. 2016, 34, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reference Document on Best Available Techniques for the Tanning of Hides and Skins; European ICCP Bureau: Seville, Spain, 2013; Available online: http://eippcb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/reference/BREF/TAN_Published_def.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Wieczorek-Ciurowa, K.; Famielec, S.; Fela, K.; Woźny, Z. The process of waste incineration in the tanning industry. Chemik 2011, 65, 917–922. [Google Scholar]

- Tahiri, S.; de la Guardia, M. Treatment and valorization of leather industry solid wastes: A review. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2009, 104, 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mwinyihija, M. Ecotoxicological Diagnosis in the Tanning Industry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R. Pre-treatment of tannery sludge for sustainable landfilling. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomaznik, K.; Adamek, M.; Andel, L.; Uhlirova, M. Leather waste—Potential threat to human health, and a new technology of its treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 160, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blowes, D. Environmental chemistry—Tracking hexavalent Cr in groundwater. Science 2002, 295, 2024–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celary, P.; Sobik-Szołtysek, J. Vitrification as an alternative to landfilling of tannery sewage sludge. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2520–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceloux, D.G. Chromium. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, A.S.; Usman, A.R.A.; Al-Makrami, H.A.; Al-Wabel, M.I.; Al-Omran, A. Environmental assessment of tannery wastes in relation to dumpsite soil: A case study from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 11019–11029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Statistical Compendium for Raw Hides and Skins, Leather and Leather Footwear 1999–2015; Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5599e.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Velusamy, M.; Chakali, B.; Ganesan, S.; Tinwala, F.; Shanmugham Venkatachalam, S. Investigation on pyrolysis and incineration of chrome-tanned solid waste from tanneries for effective treatment and disposal: An experimental study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orukoa, R.O.; Selvarajanb, R.; Ogolab, H.J.O.; Edokpayic, J.N.; Odiyo, J.O. Contemporary and future direction of chromium tanning and management in sub Saharan Africa tanneries. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 133, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustini, C.B.; Spier, F.; Costa, M.d.; Gutterres, M. Biogas production for anaerobic co-digestion of tannery solid wastes under presence and absence of the tanning agent. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 130, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhou, R.; Deng, W.; Wanga, M.; Ma, S. Ecological utilization of leather tannery waste with circular economy model. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, J.; Velappan, K.C.; Babu, N.K.C.; Sadulla, S. Solid wastes generation in the leather industry and its utilization for cleaner environment—A review. J. Scient. Indust. Res. 2006, 65, 541–548. [Google Scholar]

- Langmaier, F.; Mokrejs, P.; Kolomaznik, K.; Mladek, M. Biodegradable packing materials from hydrolysates of collagen waste proteins. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, R.; Lu, W.; Zhu, D. Research progress on resource utilization of leather solid waste. J. Leath. Sci. Eng. 2019, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masilamani, D.; Madhan, B.; Shanmugam, G.; Palanivel, S.; Narayan, B. Extraction of collagen form raw trimming wastes of tannery: A waste to wealth approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, O.; Kantrali, I.C.; Yuksel, M.; Saglam, M.; Yanik, J. Conversion of leather wastes to useful products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 49, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priebe, G.P.S.; Kipper, E.; Gusmão, A.L.; Marcilio, N.R.; Gutterres, M. Anaerobic digestion of chrome-tanned leather waste for biogas production. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccin, J.S.; Gomes, C.S.; Mella, B.; Gutterres, M. Color removal from real leather dyeing effluent using tannery waste as an adsorbent. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabaane, L.; Tahiri, S.; Albizane, A.; Krati, M.E.; Cervera, M.L.; Guardia, M.d.l. Immobilization of vegetable tannins on tannery chrome shavings and their use for the removal of hexavalent chromium from contaminated water. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 174, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.C.A.; Goncalves, M.; Oliveira, D.Q.L.; Giluherme, L.R.G.; Geurreiro, M.C.; Dallago, R.M. Solid waste from leather industry as adsorbent of organic dyes in aqueous-medium. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 141, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluska, J.; Turzyński, T.; Kardaś, D. Experimental tests of co-combustion of pelletized leather tannery wastes and hardwood pellets. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluska, J.; Turzyński, T.; Ochnio, M.; Kardaś, D. Characteristics of ash formation in the process of combustion of pelletised leather tannery waste and hardwood pellets. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Jiang, X.; Lv, G.; Yan, J.; Deng, X. Nitrogen-containing gaseous products of chrome-tanned leather shavings during pyrolysis and combustion. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, C.; Srinivas, K.; Sekaran, G. Double pyrolysis of chrome tanned leather solid waste for safe disposal and products recovery. Int. J. Scient. Eng. Res. 2013, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bahillo, A.; Armesto, L.; Cabanillas, A.; Otero, J. Thermal valorization of footwear leather wastes in bubbling fluidized bed combustion. Waste Manag. 2004, 24, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbinnen, B.; Billen, P.; Van Coninckxloo, M.; Vandecasteele, C. Heating temperature dependence of Cr(III) oxidation in the presence of alkali and alkaline earth salts and subsequent Cr(VI) leaching behaviour. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5858–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavouras, P.; Pantazopoulou, E.; Varitis, S.; Voulias, G.; Chrissafis, K.; Dimitrakopulos, G.P.; Mitrakas, M.; Zouboulis, A.I.; Karakostas, T.; Xenidis, A. Incineration of tannery sludge under oxic and anoxic conditions: Study of chromium speciaciation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 283, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, H.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, X. Effect of incineration temperature on chromium speciation in real chromium-rich tannery sludge under air atmosphere. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famielec, S. Environmental effects of tannery waste incineration in a tunnel furnace system. Proc. ECOpole 2015, 9, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, R.H. Production of ferroalloys. In Treatise on Process Metallurgy, Volume 3: Industrial Processes; Seetharaman, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 471–532. [Google Scholar]

- Mineral Commodity Summaries 2020; Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2020/mcs2020.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Koleli, N.; Demir, A. Chromite. In Environmental Materials and Waste: Resource Recovery and Pollution Prevention; Prasad, M.N.V., Shih, K., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Yang, C.; Pan, J.; Lu, L.; Guo, Z.; Liu, X. An integrated approach for production of stainless steel master alloy from a low grade chromite concentrate. Powder Technol. 2018, 335, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, L.; Basson, J.; Nelson, L. The impact of platinum production from UG2 ore on ferrochrome production in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2004, 104, 517–527. [Google Scholar]

- Kemal, M.; Sahu, O. Recovery of Chromium from Tannery Industry Waste Water by Membrane Separation Technology: Health and Engineering Aspects. Sci. Afr. 2019, 4, e00096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, B.; Glanert, A.C.; Gutterres, M. Removal of chromium from tanning wastewater and its reuse. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2015, 95, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, S.; Rabbah, M. Novel low temperature synthesis of spinel nano-magnesium chromites from secondary resources. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 568, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Jin, Y.; Chen, M.; Luo, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y. Study on the removal of chromium(III) from leather waste by a two-step method. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 79, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.R.; Buzin, P.J.W.K.; Heck, N.C.; Schneider, I.A.H. Utilization of ashes obtained from leather shaving incineration as a source of chromium for the production of HC-FeCr alloy. Miner. Eng. 2012, 29, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on Industrial Emissions (integrated pollution prevention and control). Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, L334, 17–119.

- Kotaś, J.; Stasicka, Z. Chromium occurrence in the environment and methods of its speciation. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 107, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.J.; Almeida, M.F.; Pinto, T. Influence of temperature and holding time on hexavalent chromium formation during leather combustion. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 1999, 83, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Beukes, J.P.; Dawson, N.F.; Zyl, P.G.v. Theoretical and practical aspects of Cr(VI) in the South African ferrochrome industry. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2010, 110, 743–750. [Google Scholar]

- Nafziger, R.H. A review of the deposits and beneficiation of lower-grade chromite. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 1982, 82, 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Reck, B.K.; Wang, T.; Graedel, T.E. The energy benefit of stainless steel recycling. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Paktunc, D. Calcium Chloride-Assisted Segregation Reduction of Chromite: Influence of Reductant Type and the Mechanism. Minerals 2018, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angadi, S.I.; Rao, D.S.; Prasad, A.R.; Rao, R.B. Recovery of ferrochrome values from flue dust generated in ferroalloy production—A case study. Min. Process. Extr. Metall. 2011, 120, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanari, N.; Allain, E.; Joussemet, R.; Mochón, J.; Ruiz-Bustinza, I.; Gaballah, I. An overview study of chlorination reactions applied to the primary extraction and recycling of metals and to the synthesis of new reagents. Thermochim. Acta 2009, 495, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wcisło, Z.; Michaliszyn, A.; Ślęzak, W. Wykorzystanie odpadów pogarbarskich z dużą zawartością tlenków chromu w procesie metalotermicznym. Hutnik WH 2013, 11, 724–725. [Google Scholar]

- Ślęzak, W.; Wcisło, Z.; Michaliszyn, A. Odzysk chromu z odpadów w warunkach procesu stalowniczego. Hutnik WH 2013, 11, 726–727. [Google Scholar]

| C | 43.6–48.2 |

| O | 20.8–23.0 |

| N | 13.8–15.1 |

| H | 5.8–6.2 |

| S | 1.0–2.0 |

| Cr | 2.6–3.9 |

| Na 1 | 1.2–3.1 |

| Si 1 | 0.5–1.9 |

| Cl 1 | 0.4–2.1 |

| Fe, Ca | 0.5–1.0 |

| Mg, K, Al | <0.5 |

| Element | Trimmings | Shavings | Mixture of Trimmings, Shavings and Buffing Dust |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.36 |

| H | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| N | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Cr | 53.1 | 39.1 | 44.3 |

| Cr2O3 1 | 77.6 | 57.1 | 64.7 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Famielec, S. Chromium Concentrate Recovery from Solid Tannery Waste in a Thermal Process. Materials 2020, 13, 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13071533

Famielec S. Chromium Concentrate Recovery from Solid Tannery Waste in a Thermal Process. Materials. 2020; 13(7):1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13071533

Chicago/Turabian StyleFamielec, Stanisław. 2020. "Chromium Concentrate Recovery from Solid Tannery Waste in a Thermal Process" Materials 13, no. 7: 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13071533

APA StyleFamielec, S. (2020). Chromium Concentrate Recovery from Solid Tannery Waste in a Thermal Process. Materials, 13(7), 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13071533