Expanding Canonical Spider Silk Properties through a DNA Combinatorial Approach

Abstract

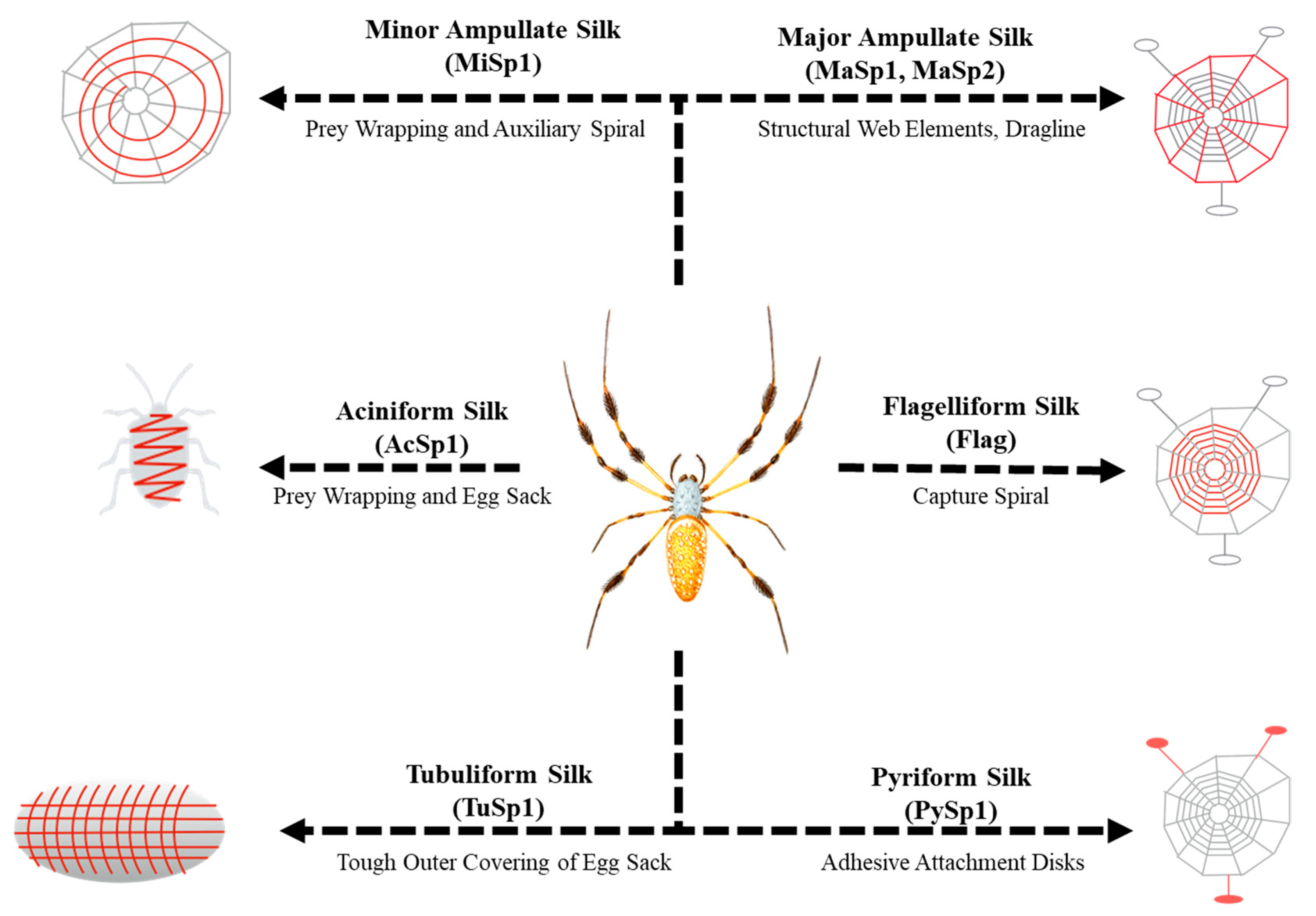

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. pET19b4 Construction

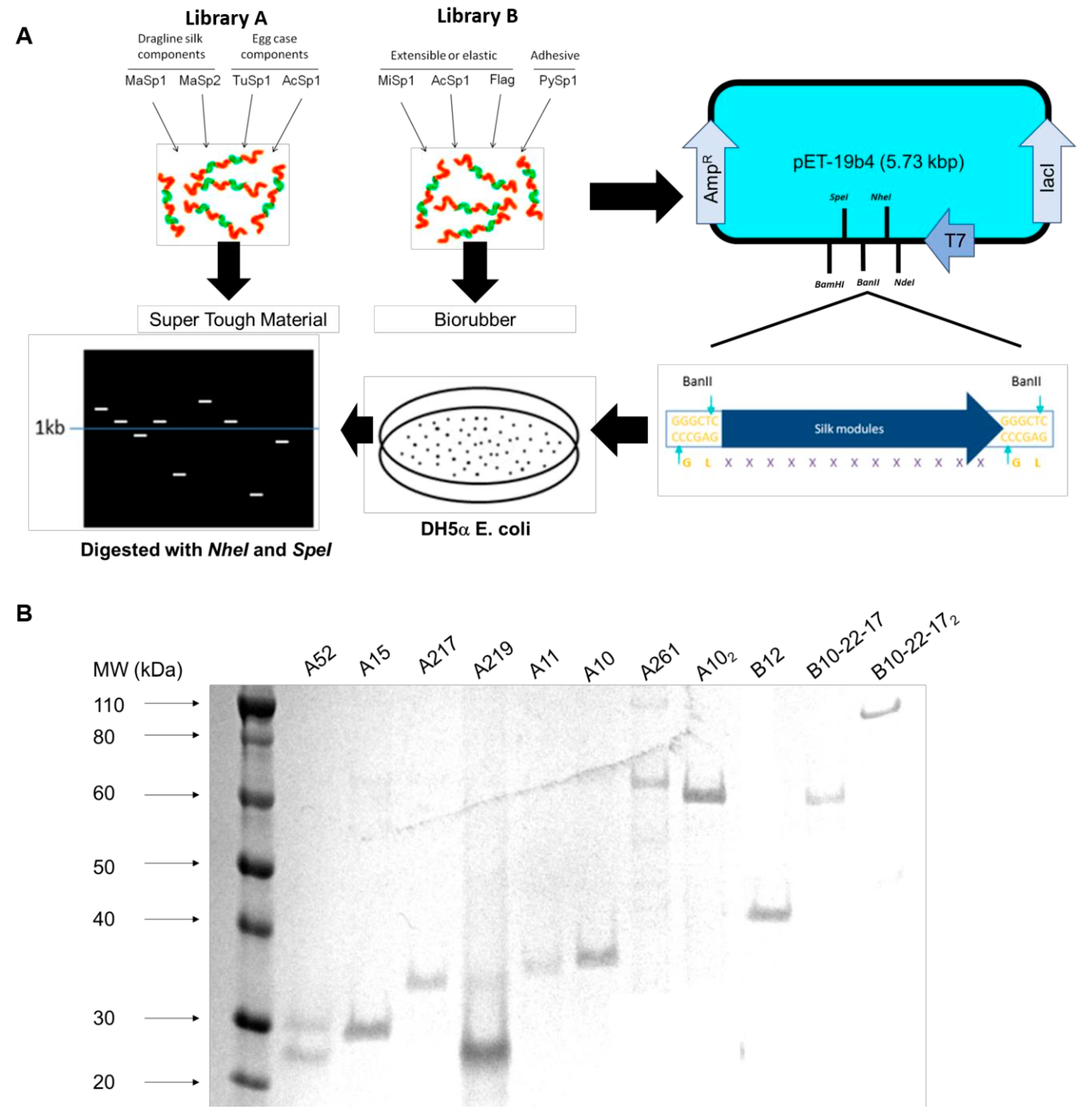

2.2. Plasmid and Library Construction

2.3. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

2.4. Protein Films and Characterization

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.6. Analysis of Primary Sequence Motifs

2.7. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for Mechanical Properties

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Construction of Dynamic Repetitive Core Library

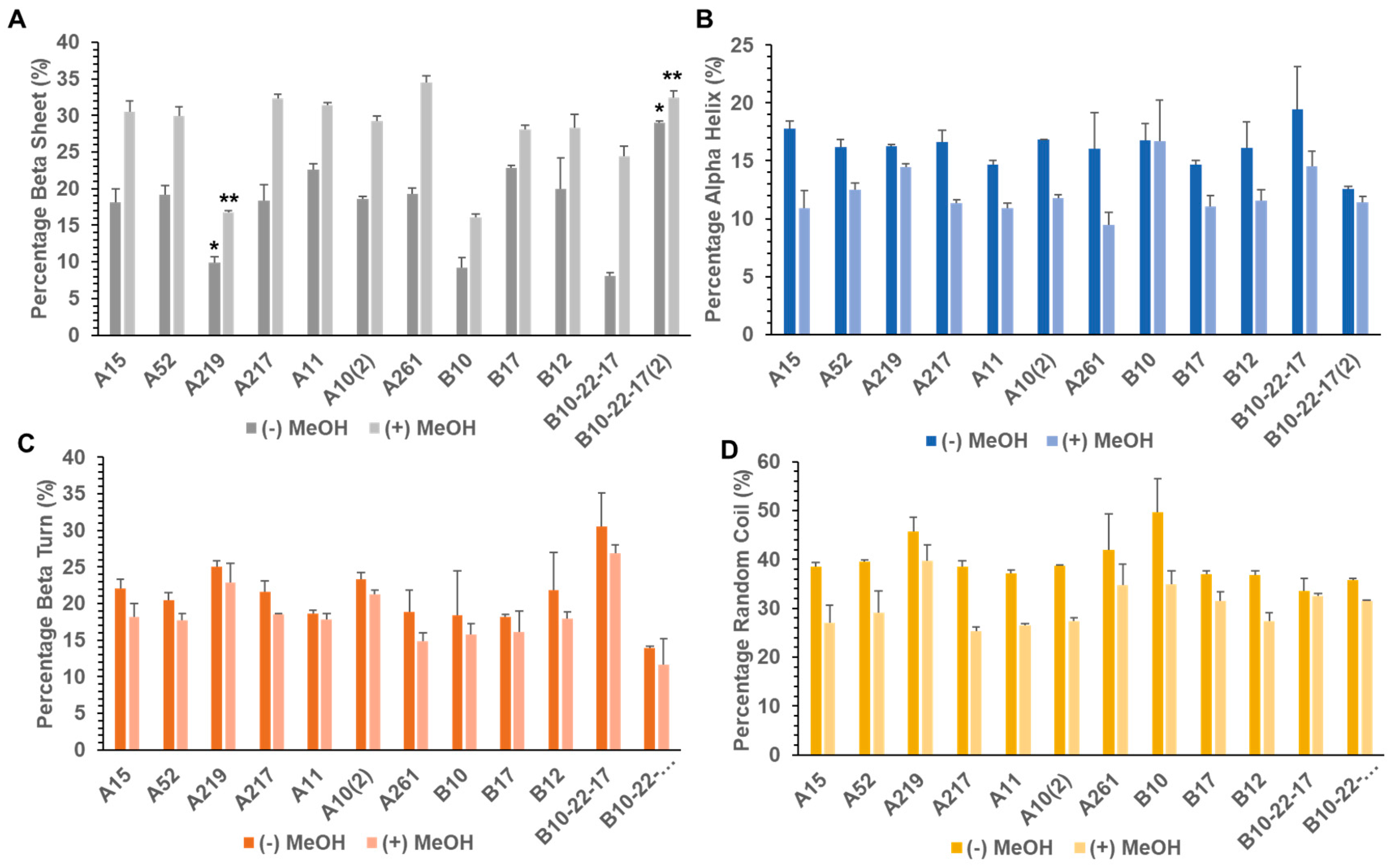

3.2. Secondary Structure of Library A and Library B generated Proteins

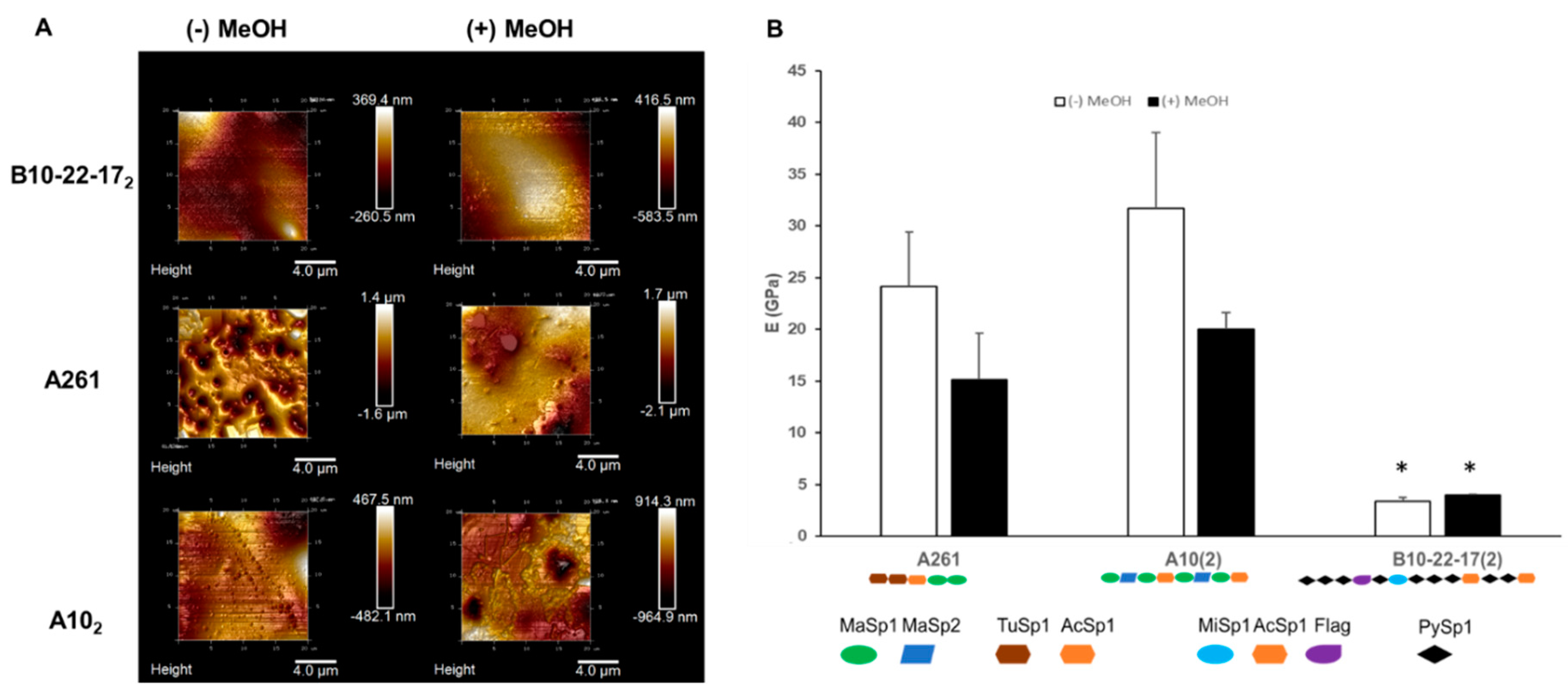

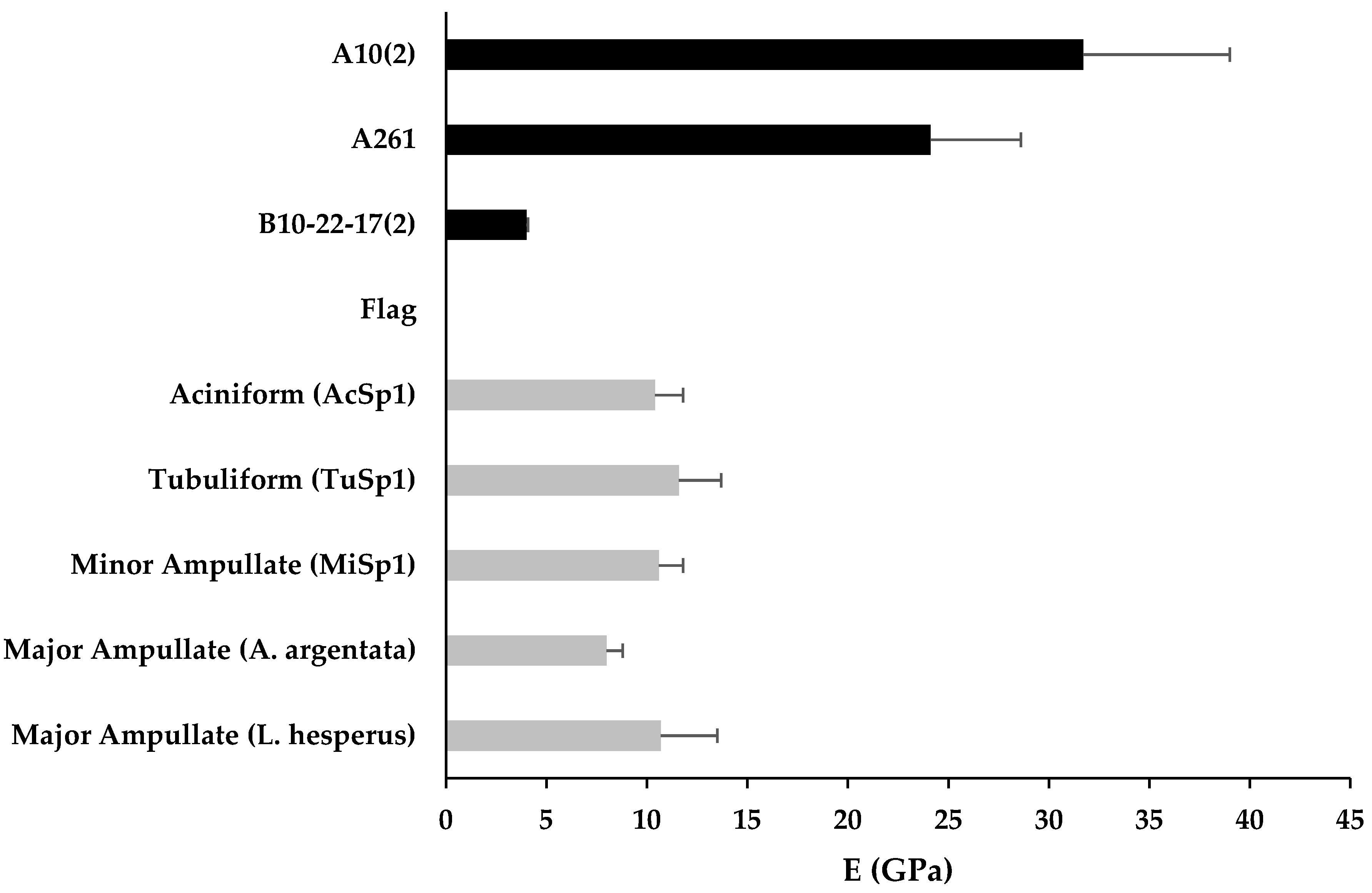

3.3. Mechanical Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yarger, J.L.; Cherry, B.R.; van der Vaart, A. Uncovering the structure–function relationship in spider silk. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisoldt, L.; Smith, A.; Scheibel, T. Decoding the secrets of spider silk. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omenetto, F.G.; Kaplan, D.L. New opportunities for an ancient material. Science 2010, 329, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnarsson, I.; Kuntner, M.; Blackledge, T.A. Bioprospecting finds the toughest biological material: Extraordinary silk from a giant riverine orb spider. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefèvre, T.; Auger, M. Spider silk as a blueprint for greener materials: A review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2016, 61, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.V. Spider silk: Ancient ideas for new biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3762–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluge, J.A.; Rabotyagova, O.; Leisk, G.G.; Kaplan, D.L. Spider silks and their applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibel, T. Spider silks: Recombinant synthesis, assembly, spinning, and engineering of synthetic proteins. Microb. Cell Fact. 2004, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamm, C.; Scheibel, T. Recombinant Production, Characterization, and Fiber Spinning of an Engineered Short Major Ampullate Spidroin (MaSp1s). Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepari, C.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk as a biomaterial. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidebrecht, A.; Scheibel, T. Recombinant Production of Spider Silk Proteins. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 82, pp. 115–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, C.H.; Dai, B.; Sargent, C.J.; Bai, W.; Ladiwala, P.; Feng, H.; Huang, W.; Kaplan, D.L.; Galazka, J.M.; Zhang, F. Recombinant Spidroins Fully Replicate Primary Mechanical Properties of Natural Spider Silk. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 3853–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, T.B.; DeSimone, E.; Scheibel, T. Biomedical Applications of Recombinant Silk-Based Materials. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rising, A.; Widhe, M.; Johansson, J.; Hedhammar, M. Spider silk proteins: Recent advances in recombinant production, structure-function relationships and biomedical applications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humenik, M.; Pawar, K.; Scheibel, T. Nanostructured, Self-Assembled Spider Silk Materials for Biomedical Applications. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; Volume 1174, pp. 187–221. [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen, J.L.; Ghandehari, H. Recombinant protein-based polymers for advanced drug delivery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2696–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokareva, O.; Jacobsen, M.; Buehler, M.; Wong, J.; Kaplan, D.L. Structure-function-property-design interplay in biopolymers: Spider silk. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, M.A.; Clarke, T.H.; Ayoub, N.A.; Hayashi, C.Y. Genomic perspectives of spider silk genes through target capture sequencing: Conservation of stabilization mechanisms and homology-based structural models of spidroin terminal regions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoruk, K.V.; Davydova, L.I.; Kozlov, D.G.; Gubaidullin, D.G.; Glazunov, A.V.; Bogush, V.G.; Debabov, V.G. Fermentation optimization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain producing 1F9 recombinant spidroin. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2015, 51, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werten, M.W.T.; Eggink, G.; Cohen Stuart, M.A.; de Wolf, F.A. Production of protein-based polymers in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 642–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaris, A.; Arcidiacono, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, J.F.; Duguay, F.; Chretien, N.; Welsh, E.A.; Soares, J.W.; Karatzas, C.N. Spider silk fibers spun from soluble recombinant silk produced in mammalian cells. Science 2002, 295, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, J.; Gührs, K.H.; Grosse, F.; Conrad, U. Production of spider silk proteins in tobacco and potato. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwitt, R.; Arcidiacono, S.; Stote, R. Evolution of repetitive proteins: Spider silks from Nephila clavipes (Tetragnathidae) and Araneus bicentenarius (Araneidae). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998, 28, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, T.D.; Young, J.H.; Weisman, S.; Hayashi, C.Y.; Merritt, D.J. Insect silk: One name, many materials. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasingame, E.; Tuton-Blasingame, T.; Larkin, L.; Falick, A.M.; Zhao, L.; Fong, J.; Vaidyanathan, V.; Visperas, A.; Geurts, P.; Hu, X.; et al. Pyriform spidroin 1, a novel member of the silk gene family that anchors dragline silk fibers in attachment discs of the black widow spider, Latrodectus hesperus. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 29097–29108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Mattina, C.; Reza, R.; Hu, X.; Falick, A.M.; Vasanthavada, K.; McNary, S.; Yee, R.; Vierra, C.A. Spider minor ampullate silk proteins are constituents of prey wrapping silk in the cob weaver Latrodectus hesperus. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 4692–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnesa, E.; Hsia, Y.; Yarger, J.L.; Weber, W.; Lin-Cereghino, J.; Lin-Cereghino, G.; Tang, S.; Agari, K.; Vierra, C. Conserved C-terminal domain of spider tubuliform spidroin 1 contributes to extensibility in synthetic fibers. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, N.A.; Garb, J.E.; Tinghitella, R.M.; Collin, M.A.; Hayashi, C.Y. Blueprint for a High-Performance Biomaterial: Full-Length Spider Dragline Silk Genes. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, F.; Porter, D. Spider silk as archetypal protein elastomer. Soft Matter 2006, 2, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Vasanthavada, K.; Kohler, K.; McNary, S.; Moore, A.M.F.; Vierra, C.A. Molecular mechanisms of spider silk. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.; Townley, M.A.; Tillinghast, E.K. Fine structural analysis of secretory silk production in the black widow spider, Latrodectus mactans. Korean J. Biol. Sci. 1998, 2, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garb, J.E.; Haney, R.A.; Schwager, E.E.; Gregorič, M.; Kuntner, M.; Agnarsson, I.; Blackledge, T.A. The transcriptome of Darwin’s bark spider silk glands predicts proteins contributing to dragline silk toughness. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, N.; Nakamura, H.; Ohtoshi, R.; Moran, D.A.P.; Shinohara, A.; Yoshida, Y.; Fujiwara, M.; Mori, M.; Tomita, M.; Arakawa, K. Orb-weaving spider Araneus ventricosus genome elucidates the spidroin gene catalogue. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colgin, M.A.; Lewis, R.V. Spider minor ampullate silk proteins contain new repetitive sequences and highly conserved non-silk-like “spacer regions”. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackledge, T.A.; Hayashi, C.Y. Unraveling the mechanical properties of composite silk threads spun by cribellate orb-weaving spiders. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 3131–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, C.Y.; Blackledge, T.A.; Lewis, R.V. Molecular and mechanical characterization of aciniform silk: Uniformity of iterated sequence modules in a novel member of the spider silk fibroin gene family. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004, 21, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garb, J.E.; Hayashi, C.Y. Modular evolution of egg case silk genes across orb-weaving spider superfamilies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11379–11384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Lewis, R.V. Tubuliform silk protein: A protein with unique molecular characteristics and mechanical properties in the spider silk fibroin family. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2006, 82, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.J.; Bittencourt, D.; Siltberg-Liberles, J.; Rech, E.L.; Lewis, R.V. Piriform spider silk sequences reveal unique repetitive elements. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 3000–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaw, R.C.; Saski, C.A.; Hayashi, C.Y. Complete gene sequence of spider attachment silk protein (PySp1) reveals novel linker regions and extreme repeat homogenization. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 81, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, C.Y.; Lewis, R.V. Evidence from flagelliform silk cDNA for the structural basis of elasticity and modular nature of spider silks. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 275, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, C.Y.; Lewis, R.V. Spider flagelliform silk: Lessons in protein design, gene structure, and molecular evolution. BioEssays 2001, 23, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrianos, S.L.; Teulé, F.; Hinman, M.B.; Jones, J.A.; Weber, W.S.; Yarger, J.L.; Lewis, R.V. Nephila clavipes Flagelliform silk-like GGX motifs contribute to extensibility and spacer motifs contribute to strength in synthetic spider silk fibers. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, B.; Jenkins, J.E.; Sampath, S.; Holland, G.P.; Hinman, M.; Yarger, J.L.; Lewis, R. Reproducing natural spider silks’ copolymer behavior in synthetic silk mimics. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3938–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oroudjev, E.; Soares, J.; Arcdiacono, S.; Thompson, J.B.; Fossey, S.A.; Hansma, H.G. Segmented nanofibers of spider dragline silk: Atomic force microscopy and single-molecule force spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 6460–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, J.T.; McGrath, K.P.; DiGirolamo, C.M.; Kaplan, D.L. Construction, Cloning, and Expression of Synthetic Genes Encoding Spider Dragline Silk. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 10879–10885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Y.; Meng, Q. Structural characterization and mechanical properties of chimeric Masp1/Flag minispidroins. Biochimie 2020, 168, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teulé, F.; Furin, W.A.; Cooper, A.R.; Duncan, J.R.; Lewis, R.V. Modifications of spider silk sequences in an attempt to control the mechanical properties of the synthetic fibers. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 8974–8985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teulé, F.; Addison, B.; Cooper, A.R.; Ayon, J.; Henning, R.W.; Benmore, C.J.; Holland, G.P.; Yarger, J.L.; Lewis, R.V. Combining flagelliform and dragline spider silk motifs to produce tunable synthetic biopolymer fibers. Biopolymers 2012, 97, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Chen, G.; Liu, X.; Meng, Q. Chimeric spider silk proteins mediated by intein result in artificial hybrid silks. Biopolymers 2016, 105, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Ye, X.; Ye, L.; Qian, Q.; Wu, M.; Song, J.; Che, J.; Zhong, B. Extraordinary Mechanical Properties of Composite Silk Through Hereditable Transgenic Silkworm Expressing Recombinant Major Ampullate Spidroin. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwana, Y.; Sezutsu, H.; Nakajima, K.; Tamada, Y.; Kojima, K. High-Toughness Silk Produced by a Transgenic Silkworm Expressing Spider (Araneus ventricosus) Dragline Silk Protein. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xia, L.; Day, B.A.; Harris, T.I.; Oliveira, P.; Knittel, C.; Licon, A.L.; Gong, C.; Dion, G.; Lewis, R.V.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 Initiated Transgenic Silkworms as a Natural Spinner of Spider Silk. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2252–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.R.; Sambrook, J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Fourth Edition). Available online: https://cshlpress.com/default.tpl?action=full&src=pdf&-eqskudatarq=934 (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Xia, X.X.; Xu, Q.; Hu, X.; Qin, G.; Kaplan, D.L. Tunable self-assembly of genetically engineered silk-elastin-like protein polymers. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3844–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Huang, W.; Belton, D.J.; Simmons, L.O.; Perry, C.C.; Wang, X.; Kaplan, D.L. Control of silicification by genetically engineered fusion proteins: Silk-silica binding peptides. Acta Biomater. 2015, 15, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domke, J.; Radmacher, M. Measuring the elastic properties of thin polymer films with the atomic force microscope. Langmuir 1998, 14, 3320–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotsch, C.; Jacobson, K.; Radmacher, M. Dimensional and mechanical dynamics of active and stable edges in motile fibroblasts investigated by using atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Itaya, A. AFM observation of silk fibroin on mica substrates: Morphologies reflecting the secondary structures. Thin Solid Film. 2003, 440, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Rnjak, J.; Weiss, A.S.; Kaplan, D.L. Biomaterials derived from silk-tropoelastin protein systems. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8121–8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, N.A.; Garb, J.E.; Kuelbs, A.; Hayashi, C.Y. Ancient Properties of Spider Silks Revealed by the Complete Gene Sequence of the Prey-Wrapping Silk Protein (AcSp1). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienneau-Hathaway, J.M.; Brassfield, E.R.; Lane, A.K.; Collin, M.A.; Correa-Garhwal, S.M.; Clarke, T.H.; Schwager, E.E.; Garb, J.E.; Hayashi, C.Y.; Ayoub, N.A. Duplication and concerted evolution of MiSp-encoding genes underlie the material properties of minor ampullate silks of cobweb weaving spiders. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, C.Y.; Lewis, R.V. Molecular architecture and evolution of a modular spider silk protein gene. Science 2000, 287, 1477–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, C.L.; Jones, J.A.; Bringhurst, H.N.; Copeland, C.G.; Addison, J.B.; Weber, W.S.; Mou, Q.; Yarger, J.L.; Lewis, R.V. Mechanical and physical properties of recombinant spider silk films using organic and aqueous solvents. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 3158–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Module | Length (AAs) | Sequence (N’→C’) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaSp1 | 35 | GGAGQGGQGGYGQGGYGQGGAGQGGAGAAAAAAAA | [28] |

| MaSp2 | 40 | GGSGPGGYGQGPAAYGPSGPSGQQGYGPGGSGAAAAAAAA | [28] |

| TuSp1 | 184 | ASQAASQSASSSYSAASQSAFSQASSSALASSSSFSSAFSSASSASAVGQVGYQIGLNAAQTLGISNAPAFADAVSQAVRTVGVGASPFQYANAVSNAFGQLLGGQGILTQENAAGLASSVSSAISSAASSVAAQAASAAQSSAFAQSQAAAQAFSQAASRSASQSAAQAGSSSTSTTTTTSQA | [37] |

| MiSp1 | 42 | GAGGYGQGQGAGAGAGAGAGAGGYGQGSGAGAAAGAAASAGA | [26] |

| AcSp1 | 188 | FGLAIAQVLGTSGQVNDANVNQIGAKLATGILRGSSAVAPRLGIDLSGINVDSDIGSVTSLILSGSTLQMTIPAGGDDLSGGYPGGFPAGAQPSGGAPVDFGGPSAGGDVAAKLARSLASTLASSGVFRAAFNSRVSTPVAVQLTDALVQKIASNLGLDYATASKLRKASQAVSKVRMGSDTNAYALA | [62] |

| PySp1 | 40 | ARAQAQAEAAARAQAQAEAAARAQAQAEAAARAQAQAEAA | [25] |

| Flag | 40 | GPGGAGPGGAGPGGAGPGGAGPGGAGPGGAGPGGAGPGGA | [41] |

| Library Colony | Estimated MW (kDa) | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| A10 | 28.8 | MaSp1-MaSp2-MaSp1-AcSp1 |

| A11 | 29.3 | MaSp2-MaSp1-MaSp2-AcSp1 |

| A15 | 21.3 | MaSp1-TuSp1 |

| A46 | 21.9 | MaSp2-TuSp1 |

| A52 | 23.0 | MaSp2-AcSp1 |

| A217 | 27.4 | (MaSp1)3-AcSp1 |

| A219 | 22.0 | (MaSp1)4-(MaSp2)3 |

| A261 | 56.0 | (TuSp1)2-AcSp1-(MaSp1)2 |

| A102 | 56.7 | (MaSp1-MaSp2-MaSp1-AcSp1)2 |

| B10 | 15.2 | (PySp1)3-Flag |

| B12 | 32.7 | PySp1-MiSp1-MaSp1-Flag-AcSp1 |

| B17 | 27.6 | (PySp1)2-AcSp1 |

| B22 | 11.5 | PySp1-MiSp1-PySp1 |

| B10-22-B17 | 55.3 | (PySp1)3-Flag-PySp1-MiSp1-PySp13-AcSp1 |

| B10-22-B172 | 81.4 | (PySp1)3-Flag-PySp1-MiSp1-PySp13-((PySp1)2-AcSp1)2 |

| Sample | Sequence | GPGXX Motifs | GGX Motifs (X = Y,L,Q) | An/GAn Motifs | AAQAA/AASQSA Motifs | Beta Sheet (%) | Beta Turn (%) | Alpha Helix (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B10-22-B172 | (PySp1)3-Flag-PySp1-MiSp1-PySp13-((PySp1)2-AcSp1)2 | 8 | 4 | 0/4 | 0/0 | 32.5 | 11.6 | 15.5 |

| A102 | (MaSp1-MaSp2-MaSp1-AcSp1)2 | 4 | 16 | 6/4 | 0/0 | 29.3 | 21.2 | 11.7 |

| A261 | (TuSp1)2-AcSp1-(MaSp1)2 | 0 | 9 | 2/2 | 2/4 | 34.4 | 14.9 | 9.5 |

| A219 | (MaSp1)4-(MaSp2)3 | 6 | 11 | 7/4 | 0/0 | 16.7 | 22.8 | 14.4 |

| B10-22-B17 | (PySp1)3-Flag-PySp1-MiSp1-PySp13-AcSp1 | 8 | 3 | 0/4 | 0/0 | 24.3 | 26.9 | 14.5 |

| Structural Role |  Elastic β-spiral |  Amorphous 310-helix |  Crystalline β-sheet | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaleel, Z.; Zhou, S.; Martín-Moldes, Z.; Baugh, L.M.; Yeh, J.; Dinjaski, N.; Brown, L.T.; Garb, J.E.; Kaplan, D.L. Expanding Canonical Spider Silk Properties through a DNA Combinatorial Approach. Materials 2020, 13, 3596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163596

Jaleel Z, Zhou S, Martín-Moldes Z, Baugh LM, Yeh J, Dinjaski N, Brown LT, Garb JE, Kaplan DL. Expanding Canonical Spider Silk Properties through a DNA Combinatorial Approach. Materials. 2020; 13(16):3596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163596

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaleel, Zaroug, Shun Zhou, Zaira Martín-Moldes, Lauren M. Baugh, Jonathan Yeh, Nina Dinjaski, Laura T. Brown, Jessica E. Garb, and David L. Kaplan. 2020. "Expanding Canonical Spider Silk Properties through a DNA Combinatorial Approach" Materials 13, no. 16: 3596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163596

APA StyleJaleel, Z., Zhou, S., Martín-Moldes, Z., Baugh, L. M., Yeh, J., Dinjaski, N., Brown, L. T., Garb, J. E., & Kaplan, D. L. (2020). Expanding Canonical Spider Silk Properties through a DNA Combinatorial Approach. Materials, 13(16), 3596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163596