3.1. Physical Properties

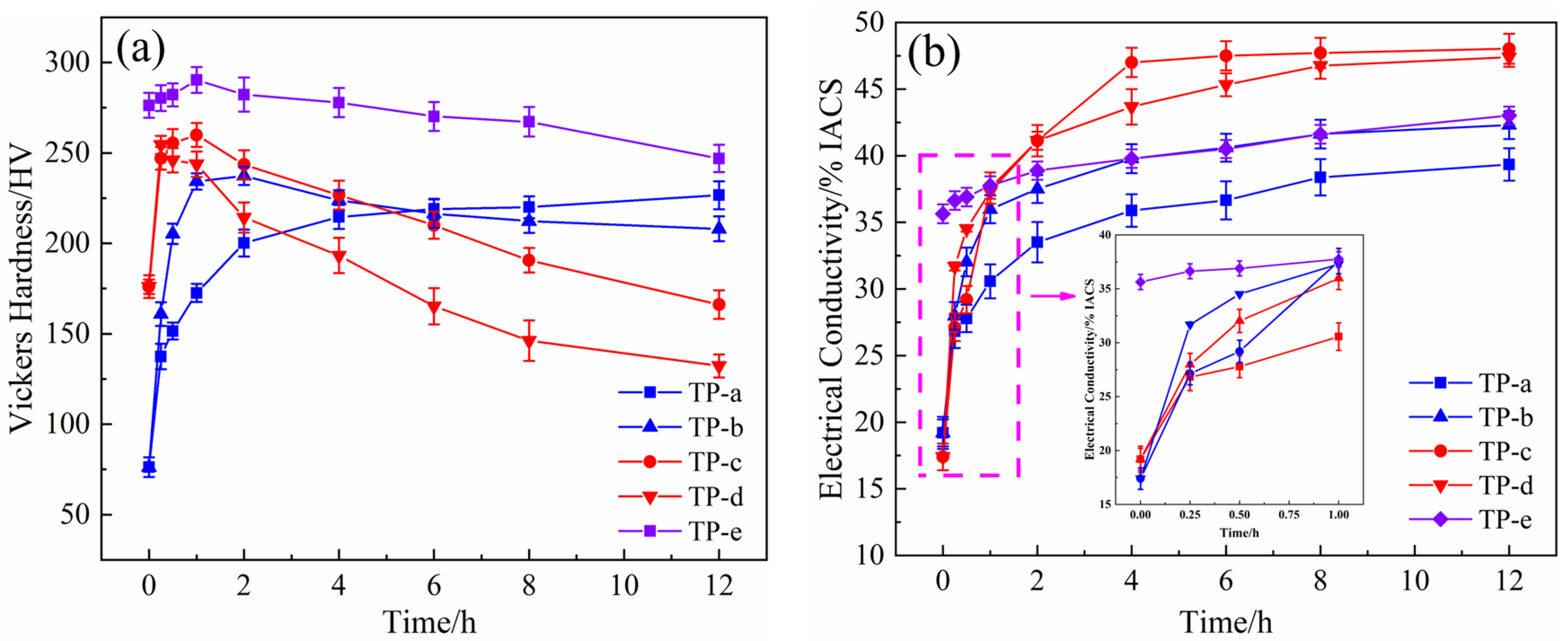

Figure 1 shows the hardness and electrical conductivity curves of Cu-Ni-Si alloys aged at 500 °C for different times. As presented in

Figure 1a, the hardness of the specimens increases rapidly, reaches the peak value, and then decreases during aging. For the different Ni/Si mass ratios of alloys, the hardness shows the same tendency in the whole time period, and the peak aging is generally achieved under the aging condition of 500 °C for 2 h. With regard to the hardness, the relationship between electrical conductivity and aging time in the Cu-Ni-Si alloys with different Ni/Si mass ratios presents the same tendency as shown in

Figure 1b. With the increase in aging time, the electrical conductivity of specimens also increases rapidly in the initial aging, then increases slowly, and finally remains steady in the end.

Figure 2 illustrates the variations of mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of alloys aged at 500 °C with different Ni/Si mass ratios. Under the same aging conditions, the hardness increases to the peak and then drops sharply with the increase in Ni/Si mass ratios as shown in

Figure 2a. The hardness is high when the Ni/Si mass ratio is 3.6–5.1 (NS-2-NS-5) and reaches the maximum value when the Ni/Si ratio is 4.2 (NS-4). For example, the peak value of micro-hardness is 238 HV when the alloy is aged at 500 °C for 2 h. The influence of different Ni/Si mass ratios on the conductivity of alloys is shown in

Figure 2b. This result indicates that the conductivity is good when the Ni/Si ratio is at 4.2–6.2 (NS-4-NS-6) and reaches the peak at a 5.1 ratio (NS-5). Considering the combination of hardness and electrical conductivity, the Ni/Si mass ratio of 4–5 (NS-4) provides good properties, and the peak aging system is at 500 °C for 2 h.

The strength and elongation of alloys with different Ni/Si mass ratios in the peak aging state are presented in

Figure 2c. The tensile and yield strength gradually increases at first and then rapidly decreases after reaching the peak value. On the contrary, the elongations gradually improve with the increase in Ni/Si mass ratios. At high Ni/Si ratio ranges, the elongations notably increase, whereas the strength remarkably decreases. The peak values are obtained when the Ni/Si ratio is 4.2 (NS-4), and the corresponding yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation are 544 MPa, 651 MPa, and 14.3%, respectively.

Figure 3 exhibits the hardness and electrical conductivity of the NS-4 alloy with different combined heat treatments. The hardness and electrical conductivity of specimens aged at 500 °C (TP-b) are higher than those of specimens aged at 450 °C (TP-a). After aging at 500 °C for 2 h, the specimens exhibit a peak hardness of 238 HV and corresponding electrical conductivity of 37.5% IACS. However, the properties of specimens aged at 500 °C (TP-d) are far inferior to those of specimens aged at 450 °C (TP-c) after the cold rolling as shown in

Figure 3a. This finding reveals that over-aging occurs at 500 °C, and the rolling process has declined the peak aging temperature of the alloy. Compared with the specimen at the direct aging state (TP-a, b), the re-aging specimen that underwent cold rolling (TP-c, d) shows better electrical conductivity properties, but its hardness sharply decreases in the late aging period. Therefore, the second cold rolling and aging processes were added to obtain an excellent and stable performance. Sample e (TP-e) underwent first cold rolling, first aging, second cold rolling, and second aging. Its hardness significantly increases, but its conductivity slightly decreases as presented in

Figure 3. After aging at 350 °C for 1 h, the NS-4 alloy shows peak hardness at 290 HV and a corresponding electrical conductivity of 37.5% IACS. Compared with those of the TP-b and TP-c, the peak hardness of the NS-4 alloy is remarkably increased by 22% and 12%, respectively.

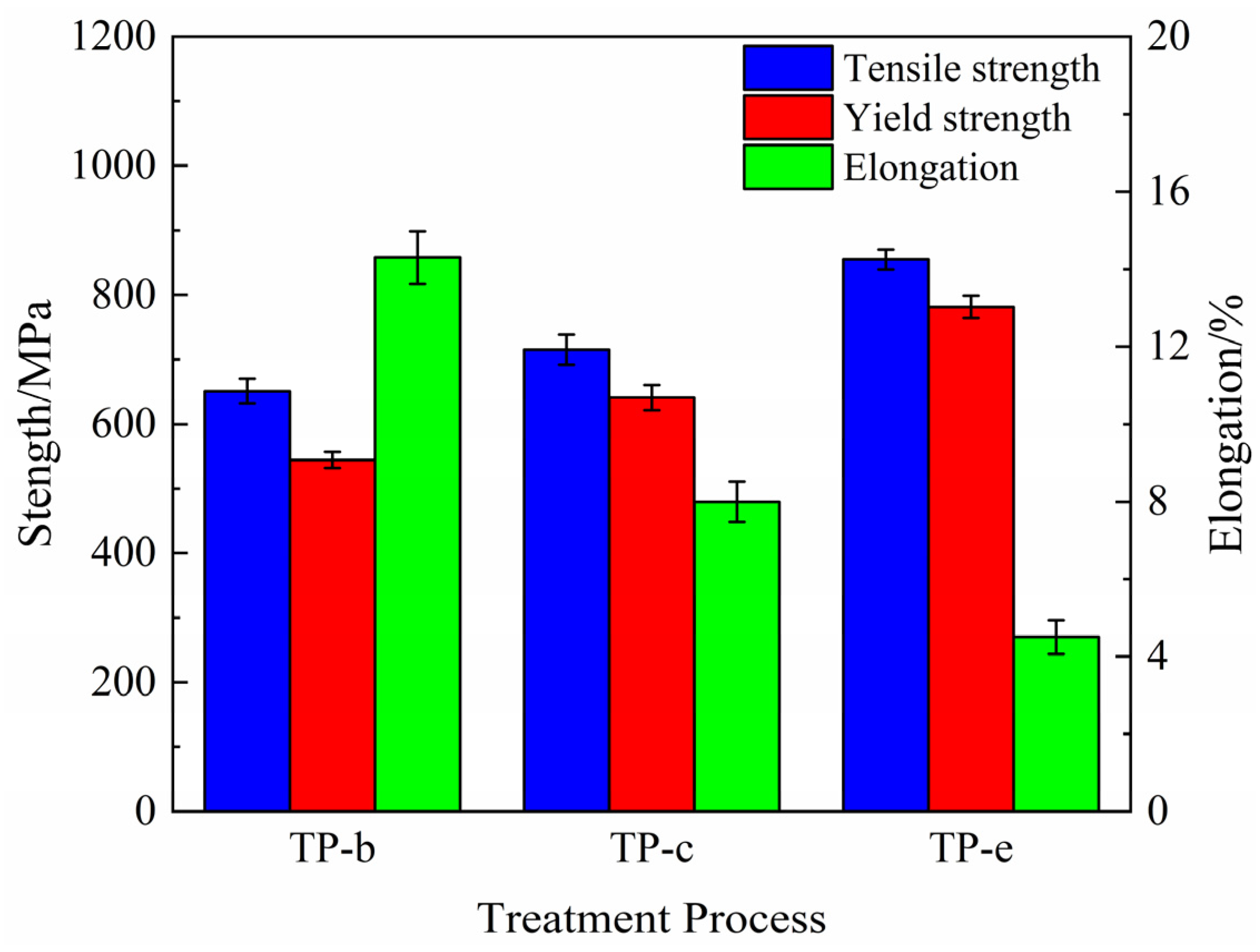

The comparison of results from tensile tests of the NS-4 alloy under peak aging with different heat treatments are shown in

Figure 4. The strength of the alloy remarkably improves after the second cold rolling and aging. Compared with those of the TP-b, the tensile and yield strength of the TP-e reach 855 MPa and 782 MPa at 31% and 44% increases, respectively. These results are ascribed to the increase in dislocation density and the acceleration of the nucleation rate of precipitates by the cold rolling, thus resulting in the enhanced strength.

3.2. Microstructure Observation

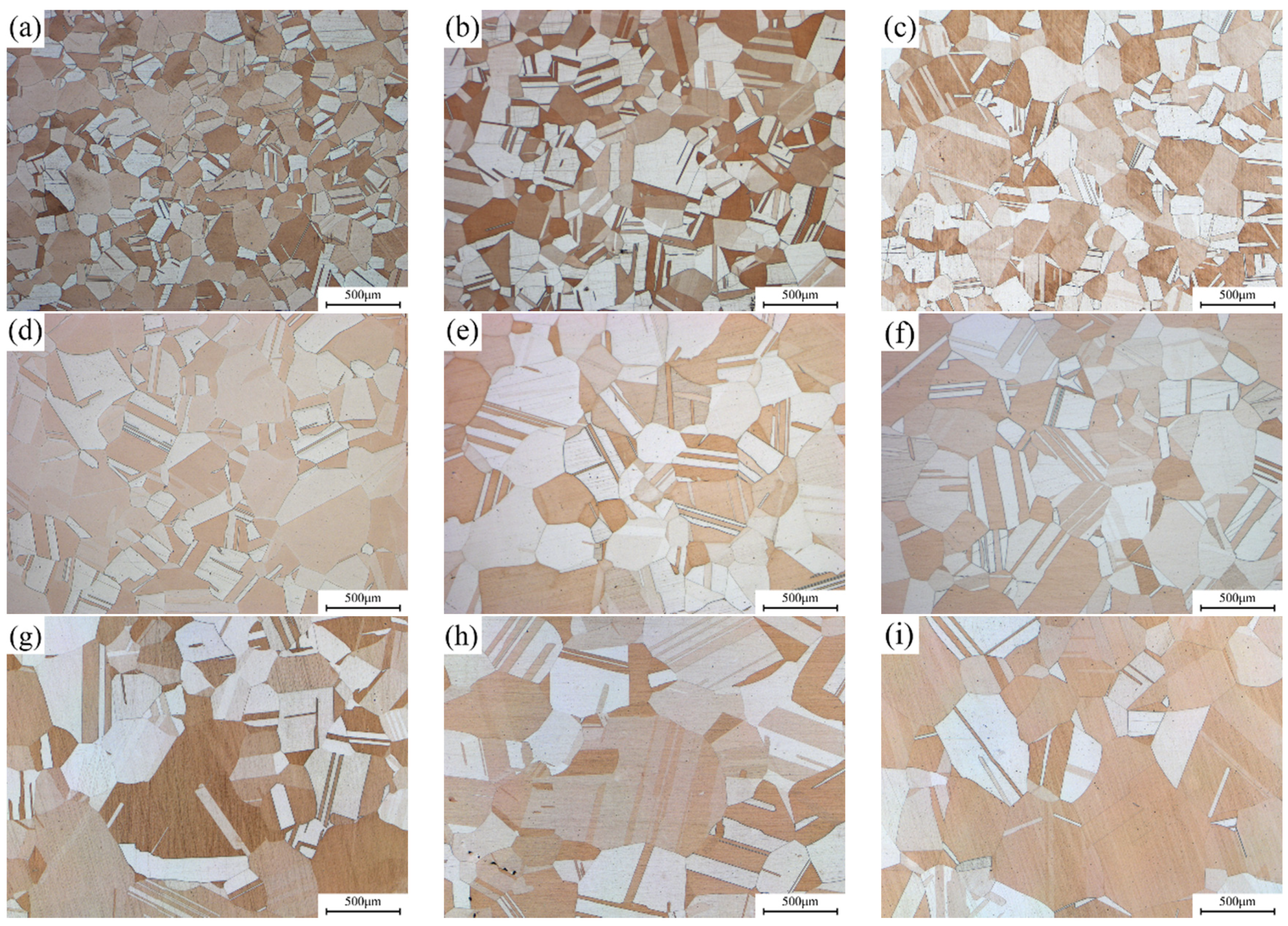

The typical microstructure of Cu-Ni-Si alloys with different Ni/Si mass ratios that underwent solution treatment is shown in

Figure 5. The equiaxed grains with twins and no inter-metallic phase are found in the matrix. This finding suggests that Ni and Si atoms are almost dissolved to form a supersaturated solid solution during the solution treatment, thus resulting in the formation of superfluous vacancies in the interior of the matrix and facilitating the precipitation of Ni-Si phases. In addition, the average grain size continues to increase with the increase in Ni/Si mass ratios.

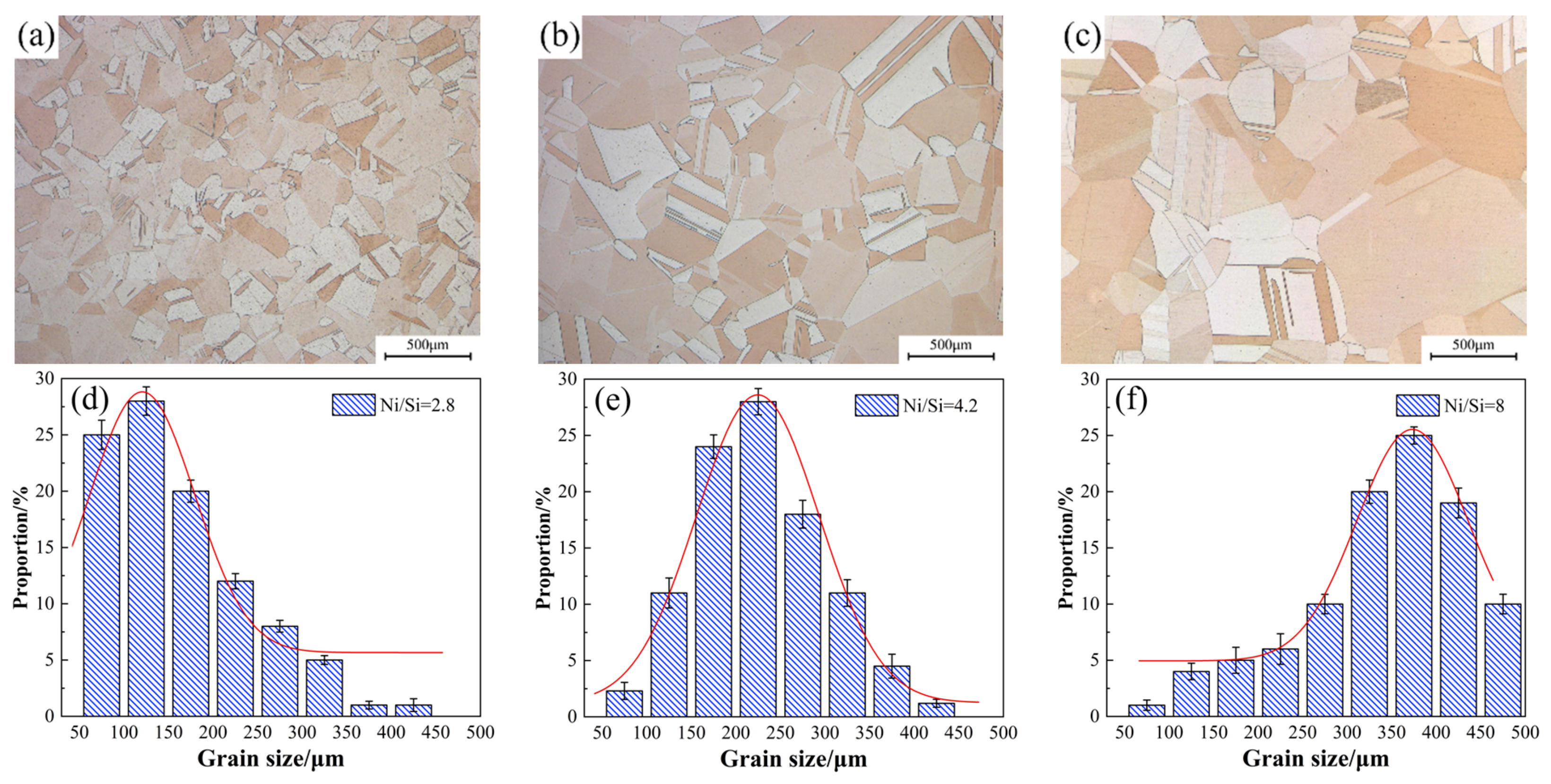

Figure 6 presents the light microscope images of alloy microstructure with different Ni/Si mass ratios at the peak aging state. The precipitated particles could not be observed in the micrograph image mainly due to their small size. Other methods were used for further observation. In addition, the average grain size also gradually increases under the aging state, which is consistent with the solution treatment. The statistics of average grain size under the peak aging state in

Figure 6 basically presents the function of normal distributions. When the Ni/Si mass ratio increases, the average grain size of the specimen also increases from approximately 145 μm to 350 μm and is accompanied by the growth of the number of twin bands.

Figure 7 illustrates the TEM images of alloy microstructure and the particle size distribution of alloys versus different Ni/Si mass ratios along the zone axis of [110]

Cu. A large number of precipitates with disc- and rod-like shapes had formed and are shown in each bright field image. With the increase in the Ni/Si ratio, uniform and fine precipitates are obtained due to the strengthening of the aged alloy. Compared with that of the NS-1 alloy, the average size of the NS-9 alloy decrease doubled, and the particles are approximately 10–11 nm in size. Finely dispersed phase particles are well distributed in the matrix, and the movement of dislocations and grain boundaries are inhibited. This phenomenon substantially contributes to the improvement of mechanical properties.

The crystallographic and morphological features of precipitates are revealed for the Cu-Ni-Si alloy aged at 500 °C for various times.

Figure 8 illustrates the TEM images obtained from the NS-4 alloy in the peak aging state. A large number of bean-shaped precipitation particles are distributed homogenously in the matrix as shown in

Figure 8a. The average size of particles is approximately 13–15 nm, which is highly coherent with the copper matrix. As indicated by the corresponding selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern image in

Figure 8b, three sets of spots are visible near the matrix spots and are marked as A, B, and C. Spots A and B are collinear and perpendicular to each other along the <100>

Cu direction, whereas spot C is distributed in the middle of the (

)

Cu position [

17]. The corresponding OR of precipitates and matrix were measured as follows: (

)

Cu//(

)

δ1//(100)

δ2//(300)

δ3, [

]

Cu//[

]

δ1//[

]

δ2//[

]

δ3. According to the central dark-field image in

Figure 8c, the precipitates have a mutually perpendicular relationship, similar crystal lattice, and ORs with the matrix. The existence of three ordering phases and ORs can be further confirmed through calibration along the [112]

Cu direction in

Figure 8d, the results of which coincide well with the analysis in

Figure 8b. Therefore, according to the crystallographic feature of ordering phases in the Cu-Ni-Si alloy, these diffraction spots are identified as δ-Ni

2Si phases with orthorhombic structure on the basis of the lattice constant (a = 0.706 nm, b = 0.499 nm, c = 0.372 nm) [

5,

6]. In addition, the Ni

2Si phase has the lowest formation enthalpy among the different Ni-Si phases, thereby further confirming that the Ni

2Si phase is the main precipitated phase [

18]. The corresponding crystal OR of precipitates and matrix were calibrated as follows: (

)

Cu//(

)

δ1//(

)

δ2//(

)

δ3, [112]

Cu//[0

]

δ1//[001]

δ2//[103]

δ3.

TEM and HRTEM images of the NS-4 alloy were obtained to identify the morphology and crystal orientation relationship of precipitates as shown in

Figure 9. The different shape characteristic of precipitation particles are observed clearly through the bright field image along the [110]

Cu directions as illustrated in

Figure 9a. From the HRTEM results in

Figure 9b,c, the precipitates of disc and rod shapes are identified in the copper matrix. The relationship between the electron beam and precipitated phase is presented in

Figure 9d. The phase shows a rod-like shape when the angle γ of the precipitation phase and incident direction is 90°, otherwise, the phase appears to be disc-like [

15]. According to the lattice parameters of the Ni

2Si phase (a = 0.706 nm, b = 0.499 nm, c = 0.372 nm) and copper matrix (a = b = c = 0.362 nm) [

19], the lattice dislocation caused by the Ni

2Si phase in the direction of axis b and c is smaller than that in the direction of axis a. The growth in the direction of axis b and c is preferred to efficiently minimize the precipitated energy, and the direction of axis a is shortened to present a disc-shaped structure. As discussed above, the true morphological characteristic of these precipitates is a disc-like shape.

The 3D approach is adopted for alloy element maps to explore in-depth information on the type and distribution of precipitates in a peak aged NS-4 alloy as shown in

Figure 10. A high number density of disc- and rod-like Ni

2Si precipitates is clearly observed, which is in accordance with the descriptions in

Figure 9. Meanwhile, the solute atoms of Ni and Si show strong co-segregation, and the Cu atoms are randomly distributed on the external of these co-segregations in the matrix. These two atoms are uniformly dispersed and alternately distributed within the precipitated phase instead of forming their own atomic cluster structure.

Figure 11a shows the atomic concentration distribution profile of the NS-4 alloy by cutting along the perpendicular direction of precipitates in

Figure 10. After smoothing, the average concentration of Ni and Si atoms inside the precipitate are approximately 65 at. % and 35 at. %.

Figure 11b also shows that the average Ni/Si atomic ratio is 1.75, which is obtained by amplifying the intermediate region of the precipitate in the corresponding atom concentration distribution profile. The atomic configuration is highly consistent with that of the Ni

2Si phase in the NS-4 alloy. The nearest neighbor distribution (NND) curve represents the difference between the experimental value and standard normal distribution curve [

20]. A distinct difference between the two curves indicates serious segregation of solute atoms in the precipitated phase [

21]. The NND curves of Ni and Si atoms are presented in

Figure 11c,d. The two atoms have strong co-segregation and correspond well with the observations in

Figure 10, indicating that the phenomenon occurs in each alloy.

TEM images of the NS-4 alloy under the peak aging state of TP-c are presented in

Figure 12. A large number of dislocations and tangles are observed in the matrix. The type of precipitated phase shows no change according to the SAED pattern image in

Figure 12b. Many dislocation tangles and cell structures are captured in the matrix, as shown in

Figure 12c,d. These dislocation entanglement regions of dislocation cells increase the storage energy of the alloy, which can be used as the precipitation channel of solute atoms.

Figure 13 shows the TEM images obtained from the NS-4 alloy with combined heat treatment of TP-e. Many dislocation tangles and precipitated particles are also observed in the matrix. Compared with those in the TP-c in

Figure 12a, finer precipitated particles and a higher density of dislocations are formed after second cold rolling and aging in

Figure 13a. From the HRTEM images in

Figure 13b, the precipitates of disc- and rod-like shapes are also identified in the matrix. The characteristic of deformation twin substructure is obtained in

Figure 13d, indicating that the severe lattice distortion of alloy occurs during deformation. From the observations in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, the growth and nucleation of the precipitated phase are accelerated by these defects, thus enhancing the strength and hardness of the studied alloy.