1. Introduction

Silicon carbide (SiC) is a promising ceramic material due to its excellent physical-chemical properties, including good mechanical properties at room and high temperatures, high thermal conductivity, high hardness, good dielectric properties, and excellent resistance to corrosion and oxidation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Thus, SiC ceramic can be used in a wide range of industrial and electronical applications such as the photovoltaic and semiconductor industry, structural materials, high-temperature materials, abrasives and traveling-wave tube [

5,

6,

7]. However, due to its strong Si–C covalent bands, high-purity SiC is very difficult to sinter to be fully dense at a low temperature without sintering additives or external pressure [

8].

As well as its excellent mechanical properties and thermal conductivity, SiC is also an superior microwave absorbent. SiC and other substrates can form fine microwave attenuation composites which can be applied as microwave absorbers in traveling wave tubes and electron accelerators to suppress parasitic electromagnetic oscillations and damp higher order modes [

9,

10,

11]. Trends in the electronic components manufacturing and applications result in an urgent desire for high thermal conductive microwave attenuation composites. BeO-based attenuation composite is a kind of excellent material which has high thermal conductivity, but its application is limited due to the toxicity of BeO [

12]. The latest study demonstrates that Aluminum nitride (AlN) is an interesting substrate for microwave attenuation composites because of its high thermal conductivity, low density (3.26 g·cm

−3), high electrical resistivity and thermal expansion coefficient. Those properties, along with its nontoxic characteristics, make AlN a popular substrate material instead of BeO. AlN and SiC also can form a solid solution under certain conditions [

13], which can largely improve the sintering activity, mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, and oxidation resistance of materials [

14,

15,

16].

It is well known that it is difficult for AlN and SiC to achieve high density due to their strong covalent bands. For densification, rare-earth oxides and metallic oxides are often added as sintering additives to fabricate AlN and SiC ceramics. At present, SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics usually are made by hot pressing. However, the hot press sintering has a high cost, long cycle, and low efficiency, and pressureless sintering has gradually become the focus of recent research. However, SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics prepared under the pressureless sintering process condition often require higher sintering temperatures [

17]. Therefore, it is necessary to find suitable sintering additives to reduce the sintering temperature through liquid-phase sintering and mass transfer to obtain dense SiC-AlN multiphase materials.

In this paper, SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics were fabricated by pressureless sintering, in which we chose Y

2O

3-BaO-SiO

2 as sintering additives. Then thermal conductivities and high-frequency dielectric properties were investigated and discussed. The selection of sintering additives refers to the additives used in hot-press sintering, Y

2O

3 is a suitable sintering additive for AlN ceramics. The additives for the preparation of dense SiC ceramics by hot-press sintering are MgO-Al

2O

3-SiO

2, Y

2O

3 (or other rare earth oxides)-Al

2O

3-SiO

2. According to the phase diagram of BaO-SiO

2 and MgO-SiO

2 [

18], the lowest temperature of the liquid phase occurs in the MgO-SiO

2 system is around 1823 K. It is significantly higher than that of BaO-SiO

2 system. When the molar ratio of BaO:SiO

2 is 1:2, the liquid phase temperature is 1696 K. All are liquid phases at 1719 K, which is about 100 K lower than the MgO-SiO

2 system. Therefore, the sintering additives of BaO-SiO

2 system is worth exploring.

2. Materials and Methods

The particle size and some specific parameters of raw materials were designed and are given in

Table 1. To prepare SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics with Y

2O

3-BaO-SiO

2 additives, α-SiC, AlN, Y

2O

3, 1.12 wt. % BaO and 0.88 wt. % SiO

2 (BaO:SiO

2 were 1:2) were mixed by ball milling in alcohol for 6 h in a polypropylene jar at a speed of 180 r/min. Then the slurry mixture was dried, crushed and sieved (140 mesh). Discs with diameter of 27 mm and thickness of 5 mm were prepared by uniaxial pressing at 100 MPa followed by cold isostatic pressing at 300 MPa. Then pressureless sintering was performed at temperatures from 2023 to 2173 K for 1 h in a flowing nitrogen atmosphere. Three series of different Y

2O

3 contents (DY, 4–8 wt. %), temperatures (DT, 2023 K, 2073 K, 2123 K, 2173 K) and different SiC contents (DS, 40 wt. %, 45 wt. %, 50 wt. %, 55 wt. %, 60 wt. %) were processed, where the temperature in DY was 2123 K and 50 wt. % SiC, the SiC content of DT was 50 wt. %, and the temperature in DS was 2123 K respectively.

The density and apparent porosity of samples was determined by the Archimedes method. The theoretical density ρ

th was calculated from the law of mixtures and was not corrected for weight loss during sintering. The calculation method is shown in Equation (1):

where P

i is the volume fraction of each component in the multiphase ceramic, ρ

i is the theoretical density of the corresponding component. Equation (2) of the calculation formula of relative density ρ

re.

X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab, Tokyo, Japan) with CuK

α was used to characterize the crystalline phase of samples. The morphology of fracture surface was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-5900, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Thermal diffusivity (α) was measured by flash method (LFA447, Netzsch, Selbu, Germany). The samples which were used to measure thermal diffusivity at 298 K were processed as disks (Ø12.7 mm × 2 mm). In addition, the experiment was conducted three times in the same conditions, then an average value of three measurements was taken. The thermal conductivity (λ) was calculated according the formula:

where ρ is the density and C

P is heat capacity of specimen. High-frequency dielectric properties of SiC-AlN ceramics were determined by a translation/reflection method using PNA-N5244A network analyzer (Agilent, Polo Alto, CA, USA). Samples of SiC-AlN ceramics were processed into 15.80 mm × 7.90 mm × 2 mm, using a rectangular waveguide transmission line as a fixture. Then, the Agilent PNA-N5244A network analyzer was used to test its complex permittivity in Ku-band (12.4–18 GHz), including dielectric constant and dielectric loss.

3. Results and Discussion

The change of apparent porosity and bulk density of the 50 wt. %SiC-40 wt. %AlN multiphase ceramics with 4–8 wt. %Y

2O

3-1.12 wt. %BaO-0.88 wt. %SiO

2 sintering additive at 2073 K for 1 h are shown in

Figure 1. As can be seen that with the content of Y

2O

3 increased, the apparent porosity of the SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics decreased, and the bulk density gradually increased. When 4 wt. % of Y

2O

3 was added, the density of the sample was poor, and the bulk density was only 3.04 g/cm

3. With the content of Y

2O

3 was up to 8 wt. %, the apparent porosity of the material was obviously reduced, and the density was increased. When the content of Y

2O

3 was increased to 8 wt. %, the porosity rate reached a minimum of 0.28%, the tendency of decreasing the apparent porosity was slow down, and the bulk density changed little, the material is substantially dense. It suggests that this sintering additives were proper for the densification of SiC-AlN ceramics.

Pressureless sintering at 2123 K for 1 h, the relative density of SiC-AlN ceramics with different SiC contents are shown in

Figure 2a. Relative density of the pressureless sintering samples ranged from 97.6% to 89.8% as the content of SiC increased. When the content of SiC increases from 40% to 50%, the relative density gradually decreases from 97.6% to 96.8%, while increasing the content of SiC to 60%, the relative density rapidly drops to 89.8%. The samples cannot be sintered densely while the content of SiC was up to 60%, but when the sintering temperature was less than 2123 K the sample of 50 wt. %SiC-40 wt. %AlN-10 wt. %Y

2O

3-BaO-SiO

2 additives at different temperatures of pressureless sintering for 1 hour, the relationship of relative density and sintering temperature are shown in

Figure 2b. When the sintering temperatures went up, the relative densities ranged from 82.5% to 97.9% (

Figure 2b). This illustrates that SiC content and sintering temperature are two of main factors which influence the sintering property of SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics. There is not enough energy to accelerate mass transport when the content of SiC is too much or the sintering temperature is too low. Except for these two factors, additives content, holding time, and pressure also will affect the densification of the multiphase ceramics.

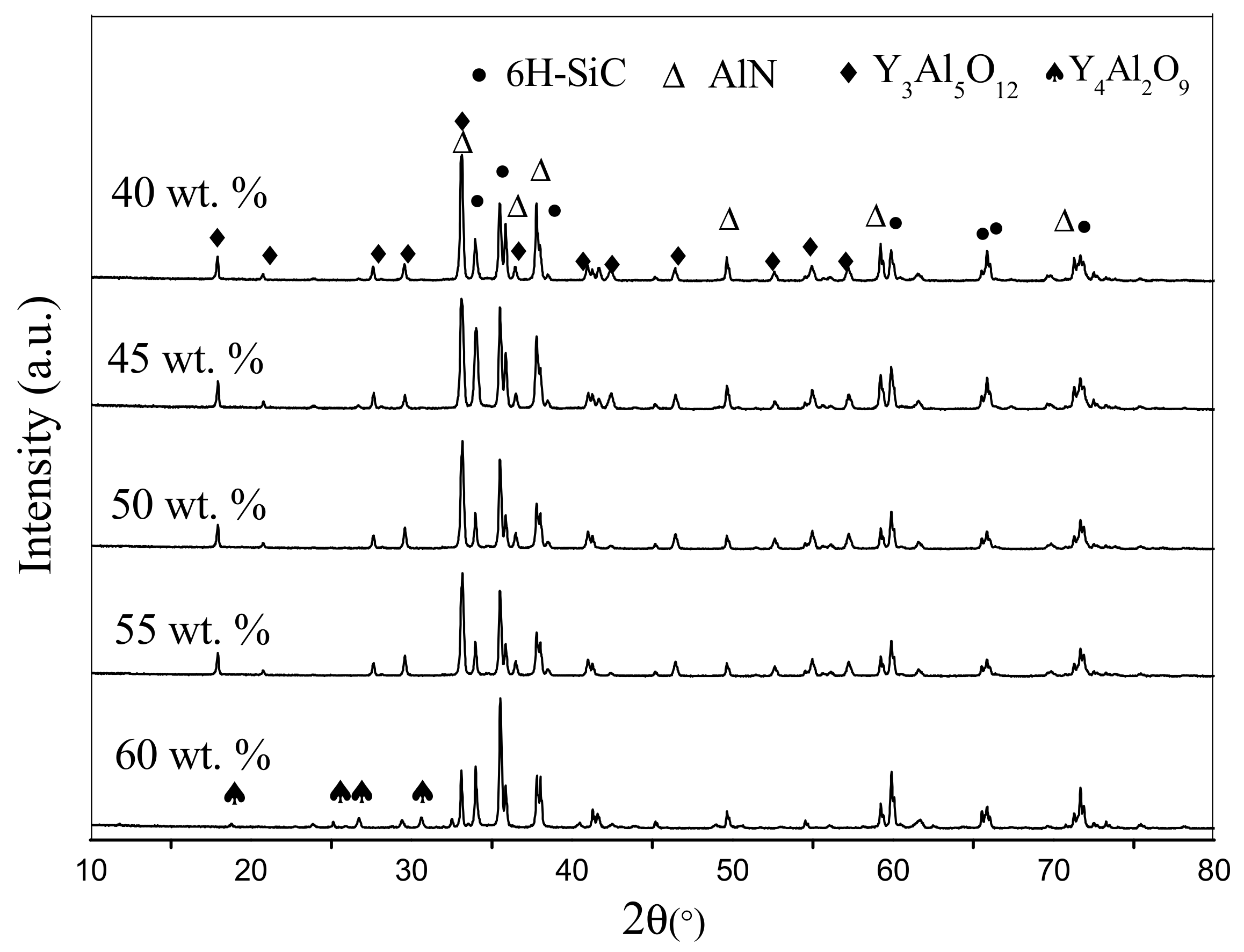

Figure 3 exhibits the XRD pattern of the SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics with different SiC contents. 6H-SiC and AlN are the main phases of samples, and the secondary phase is Y

3Al

5O

12 (YAG). The main phases of the materials are not influenced by the different contents of SiC. In the present samples, Y

2O

3 additive reacted with Al

2O

3, which is always present on the surface of the AlN particle, to form YAG. BaO and SiO

2 would form eutectic mixtures as amorphous materials. As the content of SiC increased to 60 wt. %, the Al

2O

3 brought by AlN largely decreased. Then the excessive Y

2O

3 reacted with YAG to form Y

4Al

2O

9. All the materials formed by sintering additives owned low melting point so that can exist in grain boundary as liquid phase. The liquid phase was responsible for the densification of the samples by liquid-phase sintering [

19].

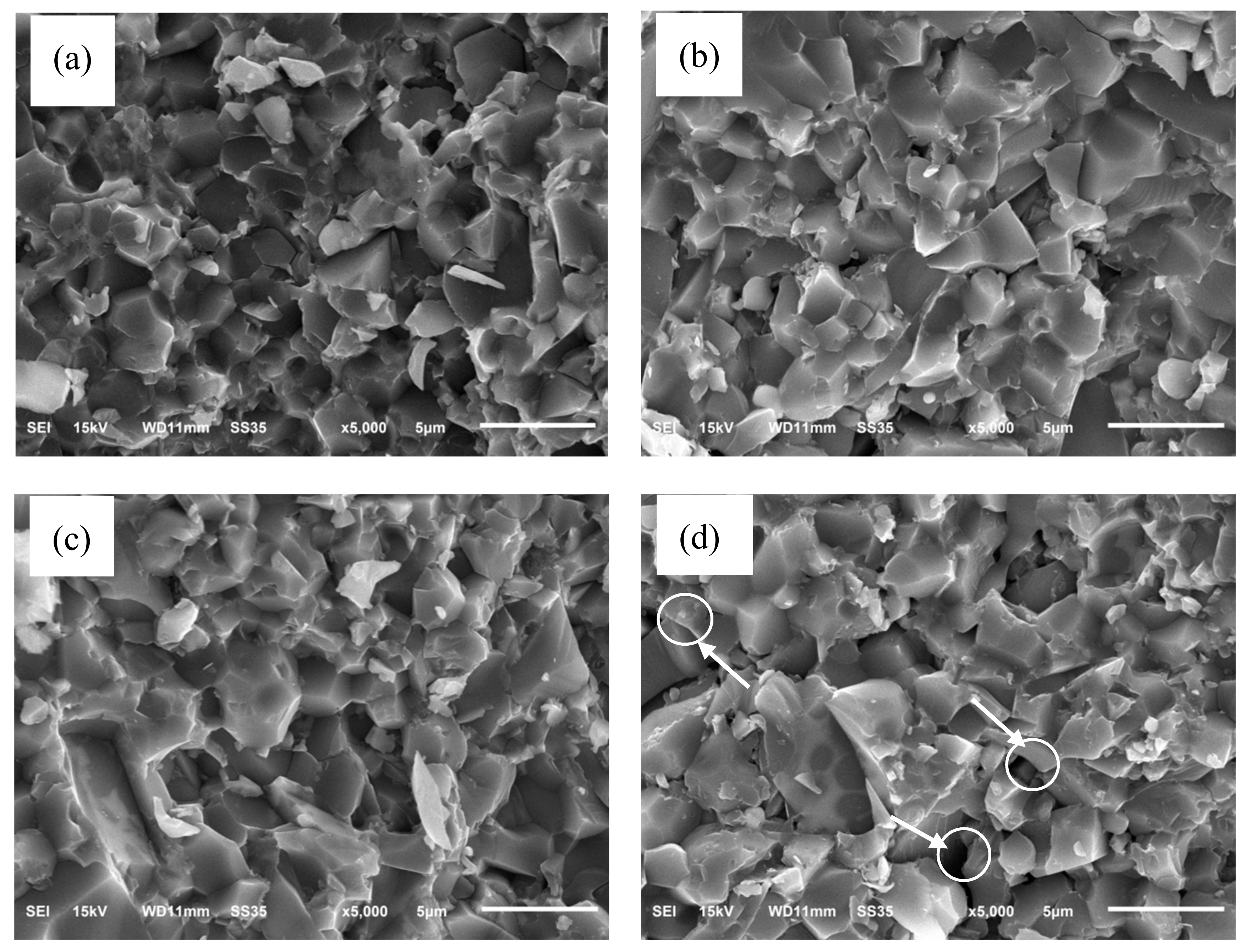

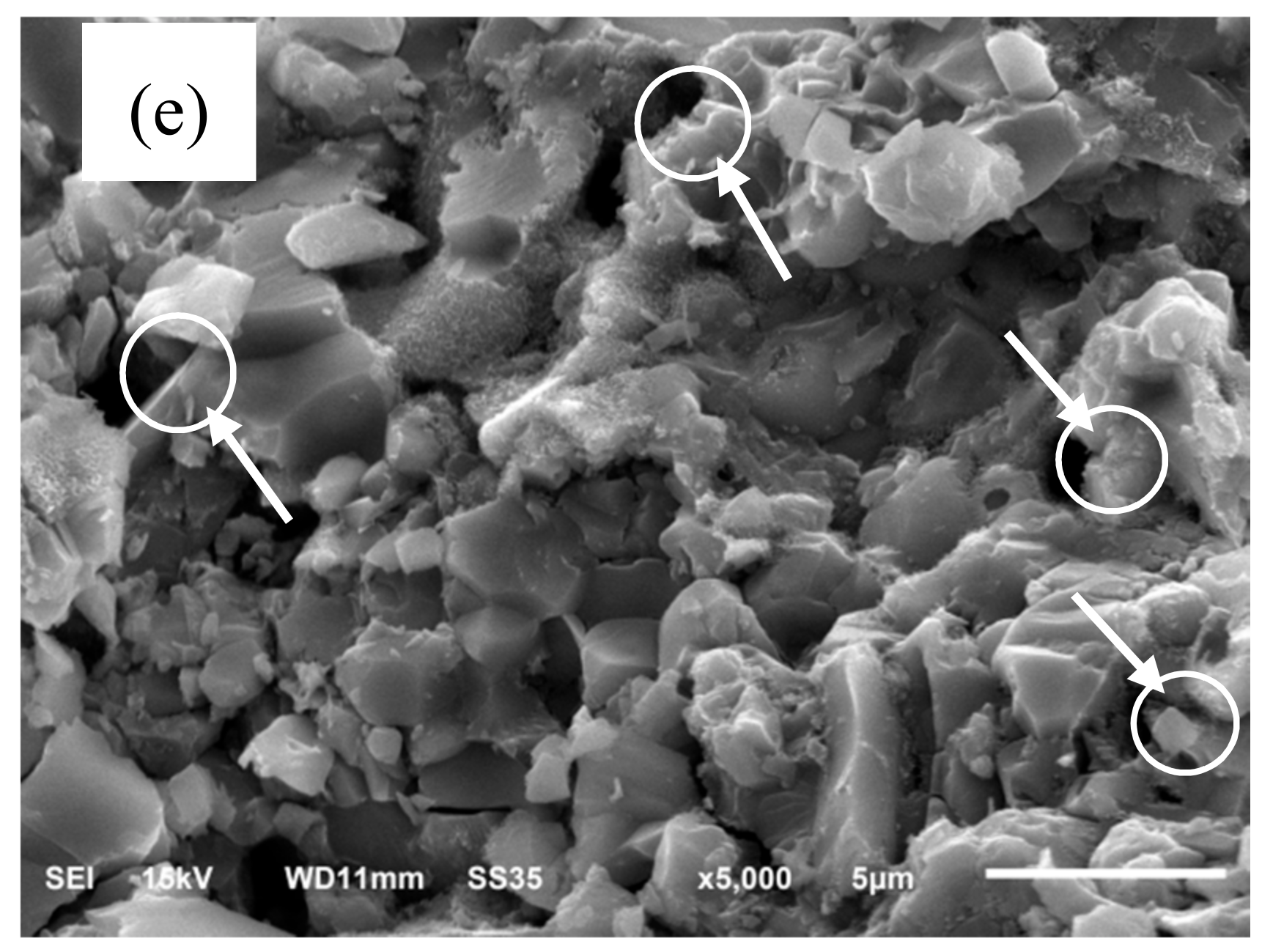

Figure 4 shows typical fracture surfaces of the SiC-AlN ceramics with different SiC contents. Except the sample with 55 wt. % and 60 wt. % SiC, all the other samples exhibited a dense microstructure with little pores. The area indicated by the circles and arrows in

Figure 4 is the pore region, which is in excellent agreement with the result of relative density. Since the self-diffusion coefficient of SiC is lower than that of AlN, as the content of SiC increased, the pores of SiC-AlN ceramics increased. The main fracture mode of the dense samples was intergranular fracture. The grain of sample with 40 wt. % SiC was more uniform than others and its size was about 3 µm. The solid vaporization pressures of AlN far exceeds that of SiC powder, so the evaporation rate of AlN was faster than that of SiC when SiC-AlN ceramics were sintered [

20]. AlN firstly vaporized and then deposited around the SiC particles to prevent the exaggerated growth of SiC grains during the sintering process. As the content of SiC increased, the content of AlN in samples became less so that it is not enough to prevent the growth of grains. It can be seen that more and more big size grains occurred in the samples with the content of SiC increasing in

Figure 4.

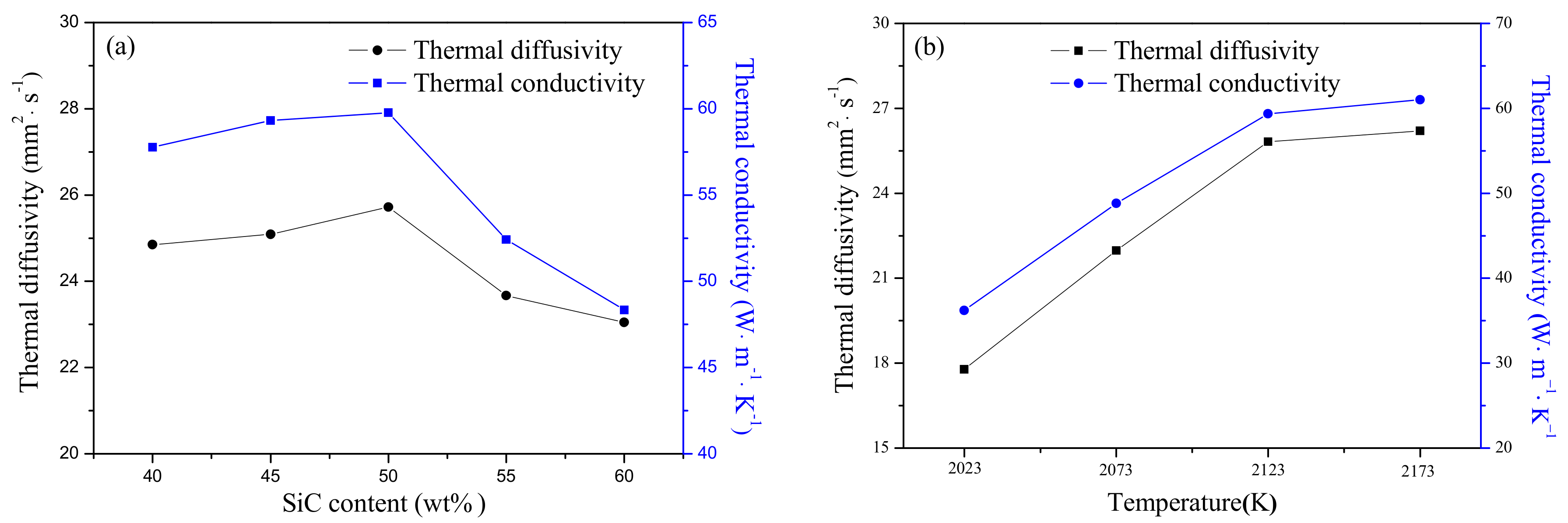

Figure 5 exhibits the thermal properties of SiC-AlN samples at room temperature with different conditions. The content of SiC increased from 40 to 50 wt. %, and the thermal conductivity increased slowly. It is speculated that the main reason is the grain boundary phase formed by the sintering additive is more beneficial for reducing phonon scattering between grains. The main reason for the decrease of the thermal conductivity of 55–60 wt. % SiC samples is the presence of the pores. The highest value of thermal diffusivity was 25.72 mm

2·s

−1 when the content of SiC was 50 wt. %, but it reduced gradually with increasing SiC content. As with the thermal diffusivity, the thermal conductivity reached a peak of 59.78 W·m

−1·K

−1 for the sample of 50 wt. % SiC (

Figure 5a). Both the thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivity went up with increasing sintering temperature to 26.21 mm

2·s

−1 and 61.02 W·m

−1·K

−1, respectively. Polycrystalline SiC ceramics and polycrystalline AlN ceramics all have high thermal conductivity (270 W·m

−1·K

−1 and 200 W·m

−1·K

−1, respectively.) [

21,

22]. However, it had a large difference with the experimental values which achieved by pressureless sintering SiC-AlN ceramics, as shown in

Figure 5. The large difference between monophasic ceramics and multiphase ceramics was attributed to the increased phonon scattering in SiC-AlN ceramics. The main reason was that the formation of SiC-AlN solid solution which largely increase phonon scattering to decrease the thermal conductivity of samples. In addition, the presence of a grain boundary and grain defects in samples also would increase phonon scattering [

23,

24,

25] The phenomenon that grain size grew up with increasing SiC content can be seen in

Figure 4, which will decrease phonon scattering. Thus, the thermal conductivity increased as the increase of SiC content. When SiC content exceeded 50 wt. %, the thermal conductivity sharply decreased due to the existence of porosity. It suggests that the presence of pores reduces thermal conductivity. As the sintering temperature was below 2123 K, the thermal conductivity increased obviously because of the decrease of residual porosity. When exceeding 2123 K, the thermal conductivity of fully dense samples increased slightly, which was mainly affected by the growth of grains in samples. Except for forming a solid solution, the main factor affecting the thermal conductivity in this experiment is the scattering of phonons by grain boundary phases and pores, and the dense samples are mainly affected by the scattering of the grain boundary phase, samples with large porosity have mainly stomatal scattering.

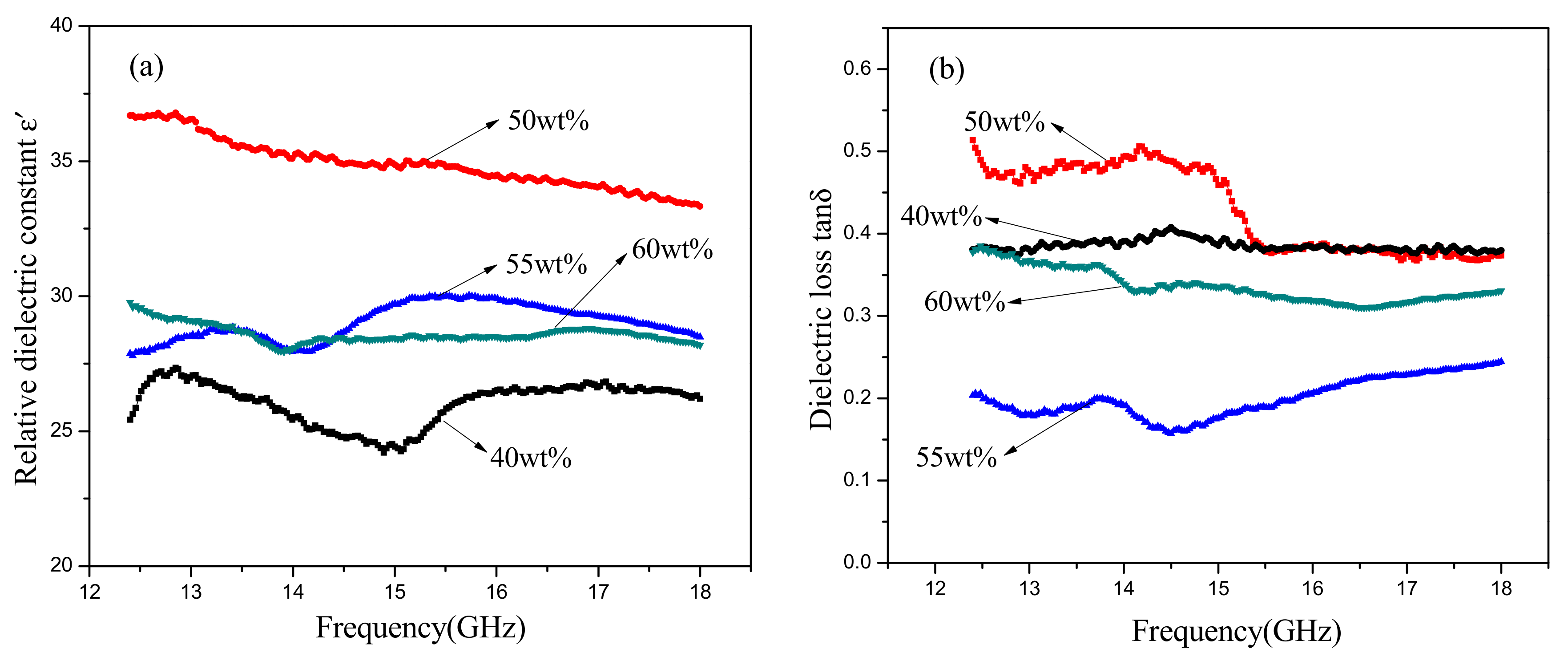

The effect of SiC content on the dielectric properties (12.4–18GHz) of SiC-AlN ceramics is shown in

Figure 6. It can be seen that both the dielectric constant (ε′) and dielectric loss (tan δ) went up to the maximum values (33–37 and 0.4–0.5, respectively) at 50 wt. % SiC and then decreased with increasing SiC content. When SiC content exceeded 55 wt. %, the dielectric properties would decrease due to the existence of porosity. The material factors determining the energy loss in a dielectric is loss factor (ε″) which is decided by the product of the dielectric constant and the dielectric loss. When the content of SiC was 50 wt. %, the energy loss of the samples reached the largest and the microwave of this frequency could be attenuated well. As the frequency increased, the dielectric constant gradually decreased, but the dielectric loss went up to a summit at 14 GHz and then reduced. It can be inferred that the maximum dielectric loss occurred when the period of relaxation process may be the same as the period of the applied field. SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics exhibit space charge polarization resulting from different electrical conductivity between SiC and AlN. The motion of the charge carriers occurs easily through one phase but is interrupted when it reaches a phase boundary. This causes a buildup of charges at the interface which corresponds to a large polarization and high dielectric constant and dielectric loss [

26]. However, a long time for space charge to establish makes it difficult to form space charge polarization. Dipole polarization losses also exist in the samples because of the formation of SiC-AlN solid solution. An Al atom has three valence electrons, but an Si atom has four. When an Al atom dissolves into SiC lattice to replace an Si atom, the compound will capture an electron and form an electropositive hole. As an electromagnetic field is applied and changes, the electronegative Al atoms and the electropositive holes can be considered to be a pair of dipoles, and dipole polarization occurs [

16]. In addition, the defects from solid solution also contribute to dielectric properties of SiC-AlN ceramics. The dielectric constant and dielectric loss of SiC-AlN ceramics are mainly caused by conductivity loss and dipole polarization loss. Therefore, the dielectric properties of dense samples increased when dipole polarization and solid solution increased with the rise of SiC content.

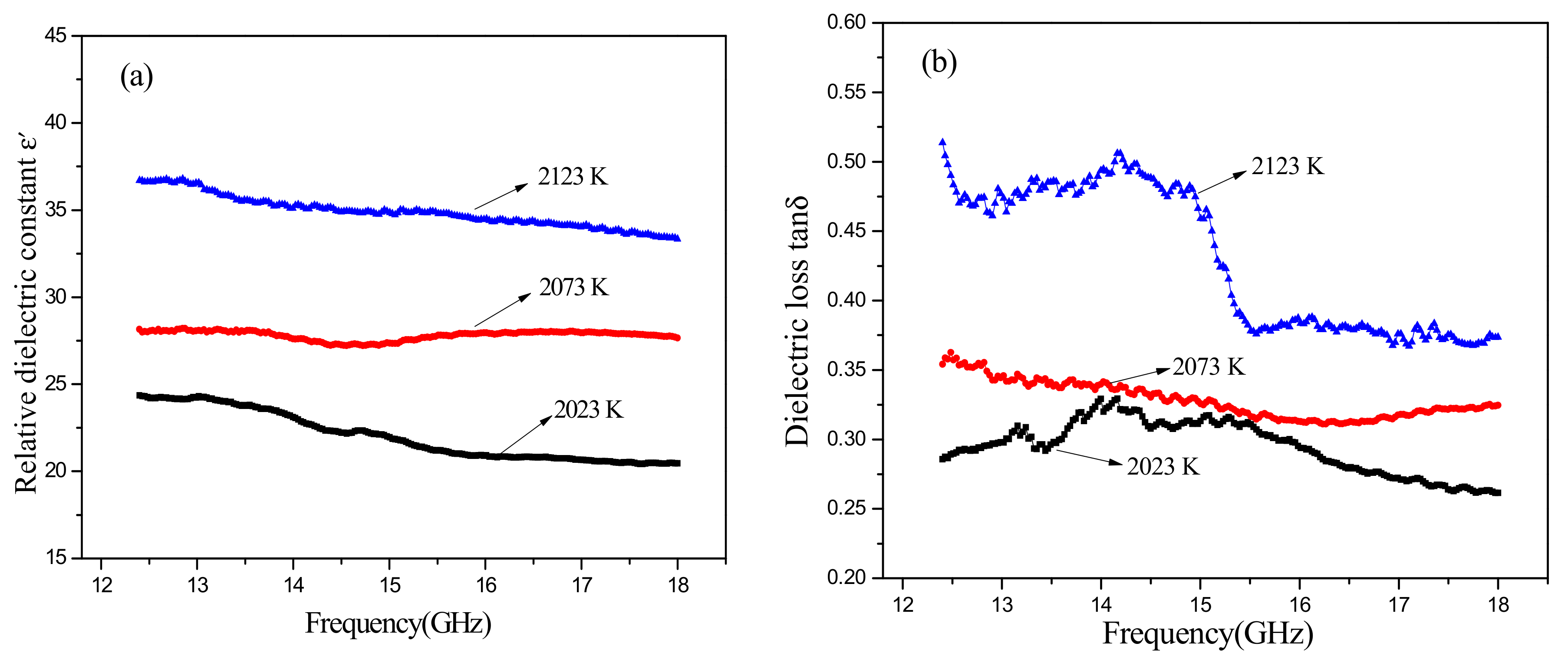

Figure 7 illustrates the dielectric properties of SiC-AlN ceramics with different sintering temperature. The dielectric constant and the dielectric loss rose as the sintering temperature increased. However, the opposite trend was shown with the increase of frequency. Similarly, with

Figure 6b, it finds a dielectric loss peak at 14 GHz in

Figure 6b. It can infer that what affects the dielectric properties of samples is mainly porosity when sintering temperature varied.