Additive and Substractive Surface Structuring by Femtosecond Laser Induced Material Ejection and Redistribution

Abstract

1. Introduction

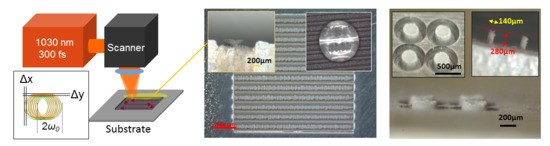

2. Materials and Methods

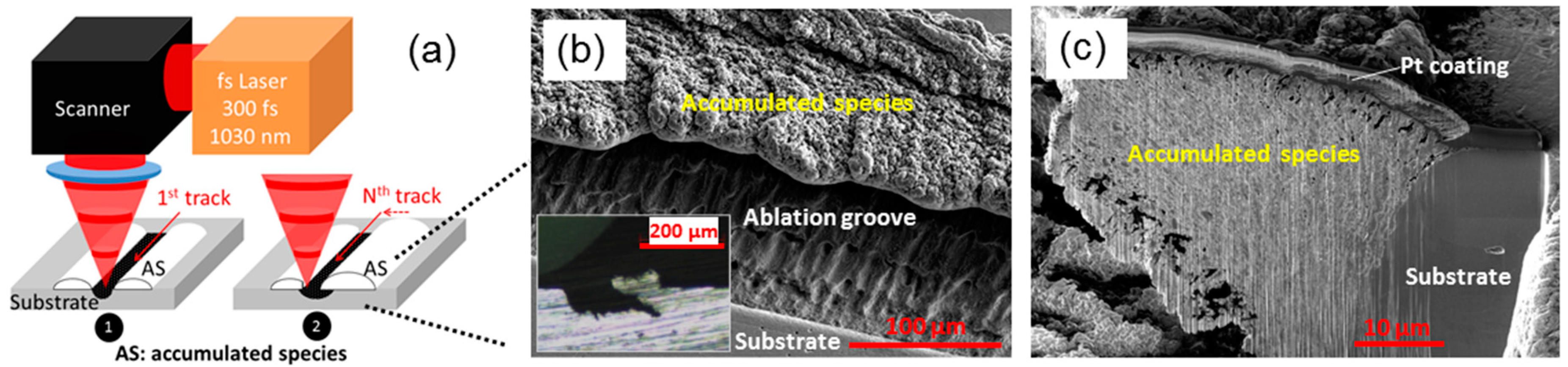

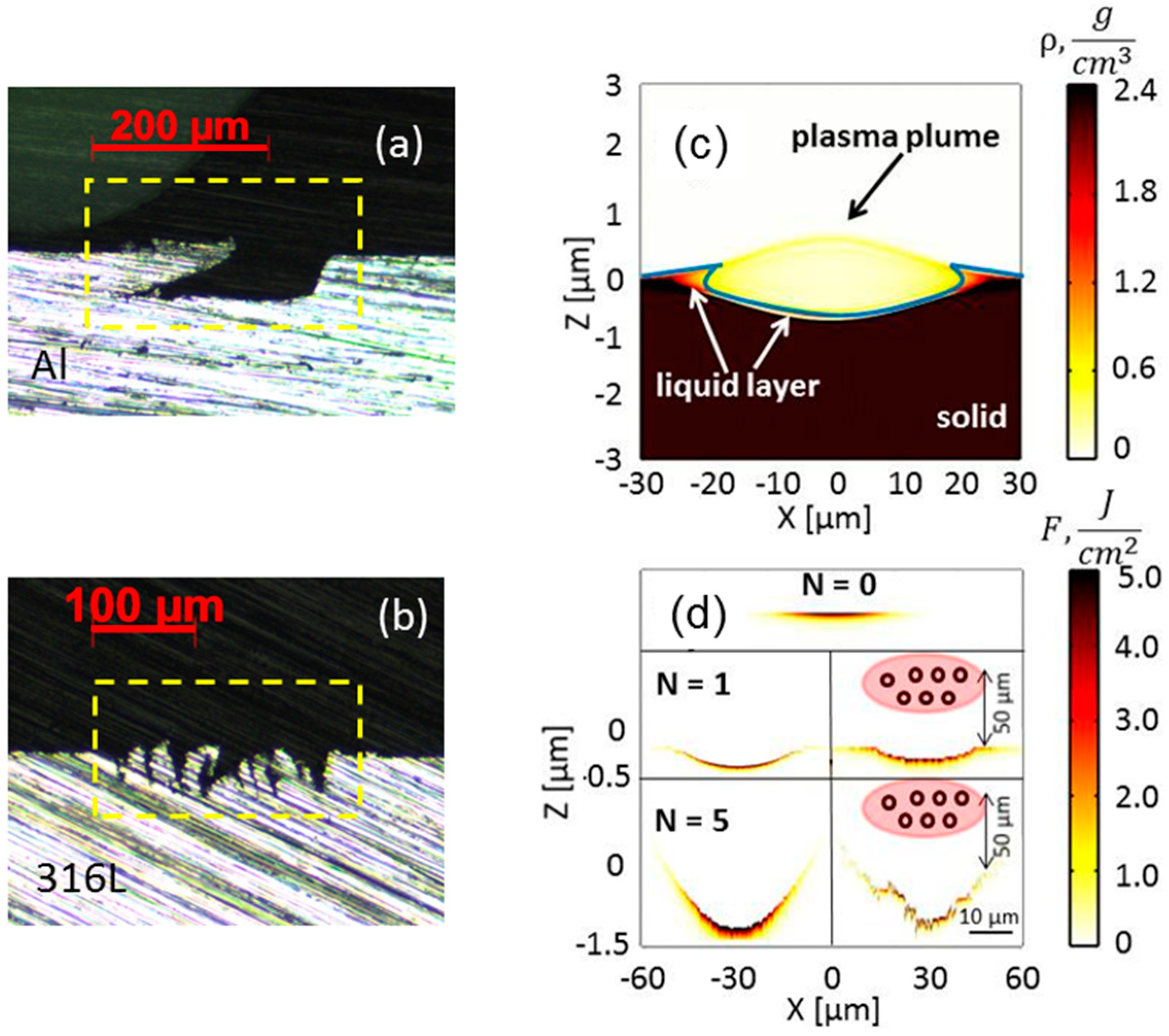

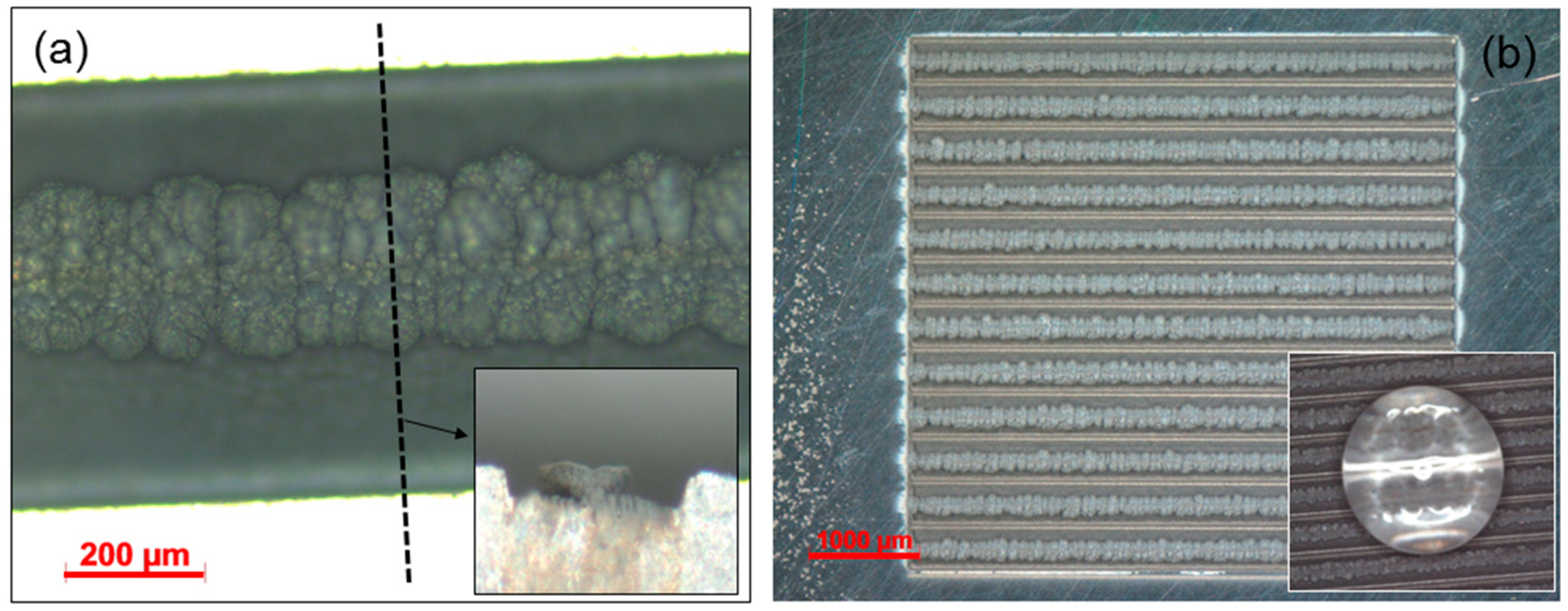

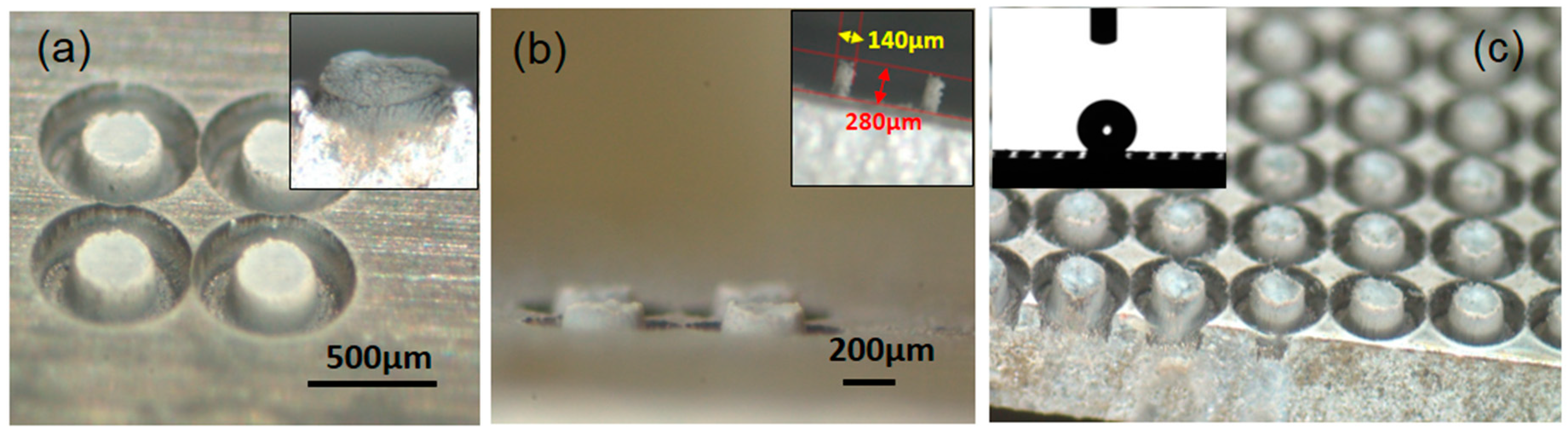

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, D.D.; Meiners, W.; Wissenbach, K.; Poprawe, R. Laser additive manufacturing of metallic components: materials, processes and mechanisms. Int. Mater. Rev. 2012, 57, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedao, X.; Abou Saleh, A.; Rudenko, A.; Douillard, T.; Esnouf, C.; Reynaud, S.; Maurice, C.; Pigeon, F.; Garrelie, F.; Colombier, J.-P. Self-Arranged Periodic Nanovoids by Ultrafast Laser-Induced Near-Field Enhancement. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Pierre, D.; Granier, J.; Egaud, G.; Baubeau, E.; Mauclair, C. Fast Uniform Micro Structuring of DLC Surfaces Using Multiple Ultrashort Laser Spots through Spatial Beam Shaping. Phys. Procedia 2016, 83, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Siegel, J.; Garcia-Lechuga, M.; Epicier, T.; Lefkir, Y.; Reynaud, S.; Bugnet, M.; Vocanson, F.; Solis, J.; Vitrant, G.; et al. Three-Dimensional Self-Organization in Nanocomposite Layered Systems by Ultrafast Laser Pulses. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 5031–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauclair, C.; Cheng, G.; Huot, N.; Audouard, E.; Rosenfeld, A.; Hertel, I.V.; Stoian, R. Dynamic ultrafast laser spatial tailoring for parallel micromachining of photonic devices in transparent materials. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 3531–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonse, J.; Mann, G.; Krüger, J.; Marcinkowski, M.; Eberstein, M. Femtosecond laser-induced removal of silicon nitride layers from doped and textured silicon wafers used in photovoltaics. Thin Solid Films 2013, 542, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Yang, L.; Huang, H.; Bai, S.; Wan, P.; Liu, J. Femtosecond laser additive manufacturing of iron and tungsten parts. Appl. Phys. A 2015, 119, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Huang, H.; Bai, S.; Liu, J. Femtosecond laser melting and resolidifying of high-temperature powder materials. Appl. Phys. A 2015, 118, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaporte, P.; Alloncle, A.-P. Laser-induced forward transfer: A high resolution additive manufacturing technology. Opt. Laser Technol. 2016, 78, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqué, A.; Serra, P. Laser Printing of Functional Materials: 3D Microfabrication, Electronics and Biomedicine; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mingareev, I.; Bonhoff, T.; El-Sherif, A.F.; Meiners, W.; Kelbassa, I.; Biermann, T.; Richardson, M. Femtosecond laser post-processing of metal parts produced by laser additive manufacturing. J. Laser Appl. 2013, 25, 052009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baubeau, E.; Missemer, F.; Bertrand, P. System and Method for Additively Manufacturing by Laser Melting of a Powder Bed 2017. U.S. Patent 15,762,482, 27 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eichstädt, J.; Huis, A.J. Analysis of Irradiation Processes for Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures. Phys. Procedia 2013, 41, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigilei, L.V.; Lin, Z.; Ivanov, D.S. Atomistic Modeling of Short Pulse Laser Ablation of Metals: Connections between Melting, Spallation, and Phase Explosion†. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 11892–11906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmler, A.; Küpper, M.; Walochnik, M.A.; Lanfermann, A.; Schmickler, T.; Bach, A.; Greifenberg, T.; Oreshkin, O.; Willenborg, E.; Wissenbach, K.; et al. Surface structuring by laser remelting of metals. J. Laser Appl. 2017, 29, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedao, X.; Mathieu, L.; Rudenko, A.; Pascale-Hamri, A.; Faure, N.; Colombier, J.-P.; Mauclair, C. Influence of Pulse Repetition Rate on Morphology and Material Removal Efficiency of Ultrafast Laser Ablated Metallic Surfaces. Opt. Laser Eng. Submitted.

- Zuhlke, C.A.; Anderson, T.P.; Alexander, D.R. Formation of multiscale surface structures on nickel via above surface growth and below surface growth mechanisms using femtosecond laser pulses. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 8460–8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisimov, S.I.; Luk’yanchuk, B.S. Selected problems of laser ablation theory. Phys.-Usp. 2002, 45, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombier, J.P.; Combis, P.; Audouard, E.; Stoian, R. Guiding heat in laser ablation of metals on ultrafast timescales: an adaptive modeling approach on aluminum. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 013039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.N.; Zhigilei, L.V. Melt dynamics and melt-through time in continuous wave laser heating of metal films: Contributions of the recoil vapor pressure and Marangoni effects. Int. J. Heat Mass Trans. 2017, 112, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourquard, F.; Loir, A.-S.; Donnet, C.; Garrelie, F. In situ diagnostic of the size distribution of nanoparticles generated by ultrashort pulsed laser ablation in vacuum. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, S.; Hermann, J.; Itina, T. Investigation of nanoparticle generation during femtosecond laser ablation of metals. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 6310–6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoruso, S.; Ausanio, G.; Bruzzese, R.; Vitiello, M.; Wang, X. Femtosecond laser pulse irradiation of solid targets as a general route to nanoparticle formation in a vacuum. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 033406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillermin, M.; Colombier, J.P.; Valette, S.; Audouard, E.; Garrelie, F.; Stoian, R. Optical emission and nanoparticle generation in Al plasmas using ultrashort laser pulses temporally optimized by real-time spectroscopic feedback. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 035430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, N.; Anoop, K.K.; Ausanio, G.; Gill-Comeau, M.; Bruzzese, R.; Amoruso, S.; Lewis, L.J. Ultrashort laser ablation of bulk copper targets: Dynamics and size distribution of the generated nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 243301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, A.; Mauclair, C.; Garrelie, F.; Stoian, R.; Colombier, J.P. Light absorption by surface nanoholes and nanobumps. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 470, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, R.; Perry, G.; Harnois, M.; Coffinier, Y.; Thomy, V.; Senez, V.; Boukherroub, R. From micro to nano reentrant structures: hysteresis on superomniphobic surfaces. Colloid Polym Sci 2013, 291, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qin, Q.H.; Shah, A.; Ras, R.H.A.; Tian, X.; Jokinen, V. Oil droplet self-transportation on oleophobic surfaces. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sedao, X.; Lenci, M.; Rudenko, A.; Pascale-Hamri, A.; Colombier, J.-P.; Mauclair, C. Additive and Substractive Surface Structuring by Femtosecond Laser Induced Material Ejection and Redistribution. Materials 2018, 11, 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11122456

Sedao X, Lenci M, Rudenko A, Pascale-Hamri A, Colombier J-P, Mauclair C. Additive and Substractive Surface Structuring by Femtosecond Laser Induced Material Ejection and Redistribution. Materials. 2018; 11(12):2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11122456

Chicago/Turabian StyleSedao, Xxx, Matthieu Lenci, Anton Rudenko, Alina Pascale-Hamri, Jean-Philippe Colombier, and Cyril Mauclair. 2018. "Additive and Substractive Surface Structuring by Femtosecond Laser Induced Material Ejection and Redistribution" Materials 11, no. 12: 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11122456

APA StyleSedao, X., Lenci, M., Rudenko, A., Pascale-Hamri, A., Colombier, J.-P., & Mauclair, C. (2018). Additive and Substractive Surface Structuring by Femtosecond Laser Induced Material Ejection and Redistribution. Materials, 11(12), 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11122456