Use of Almond Shells and Rice Husk as Fillers of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA) Composites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Preliminary Work: Reactivity Tests

2.2. Preliminary Work: Viscosity Measurement

2.3. Materials and Formulations Selected for Testing

2.4. Mechanical Tests

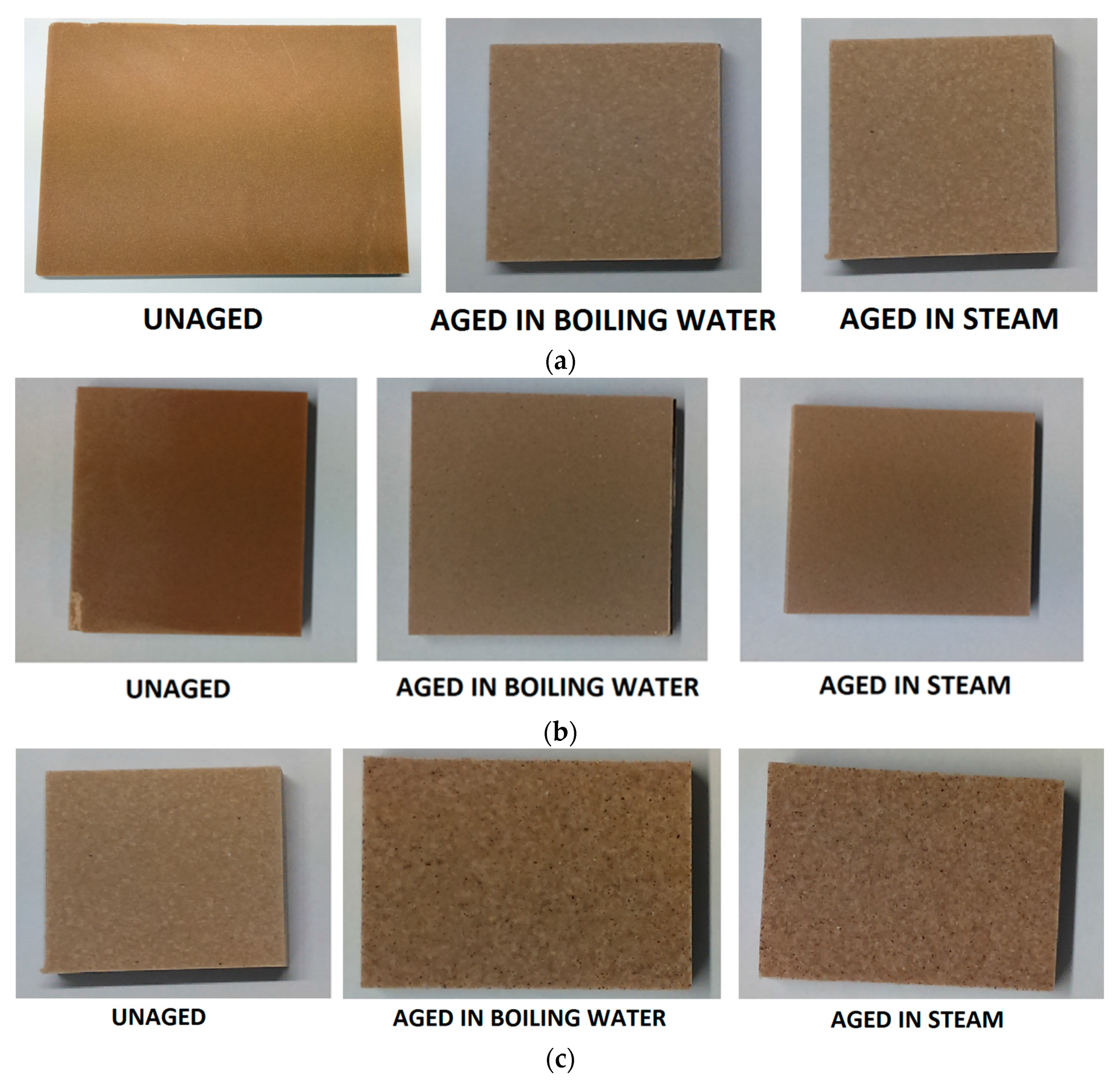

2.5. UV Resistance

2.6. Resistance to Water

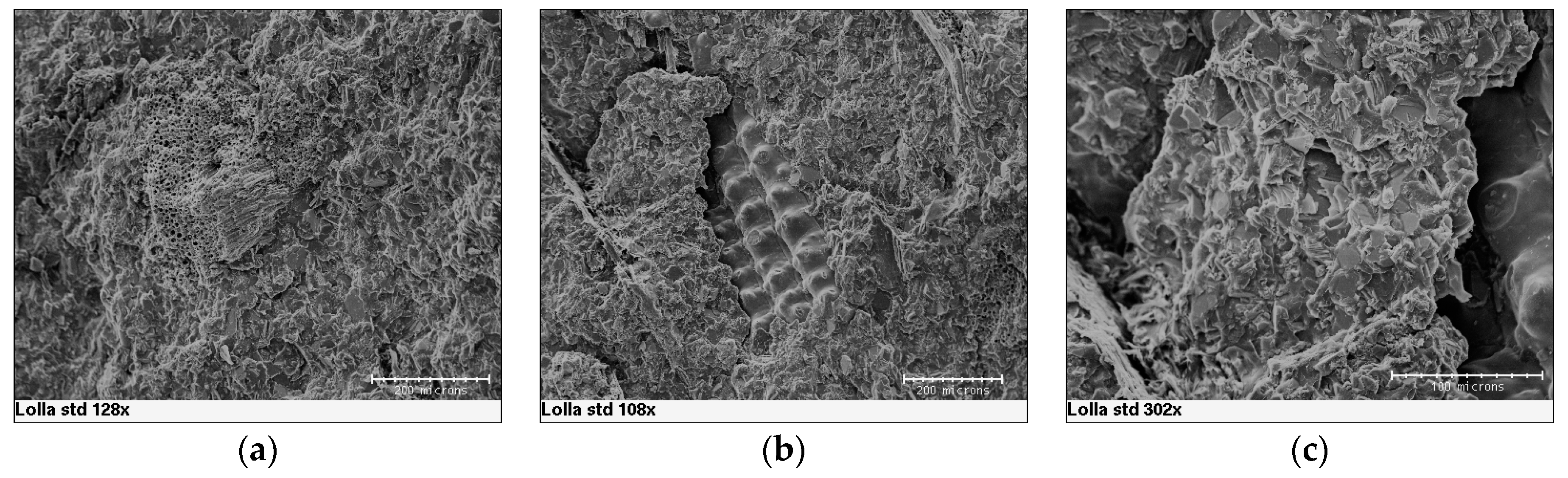

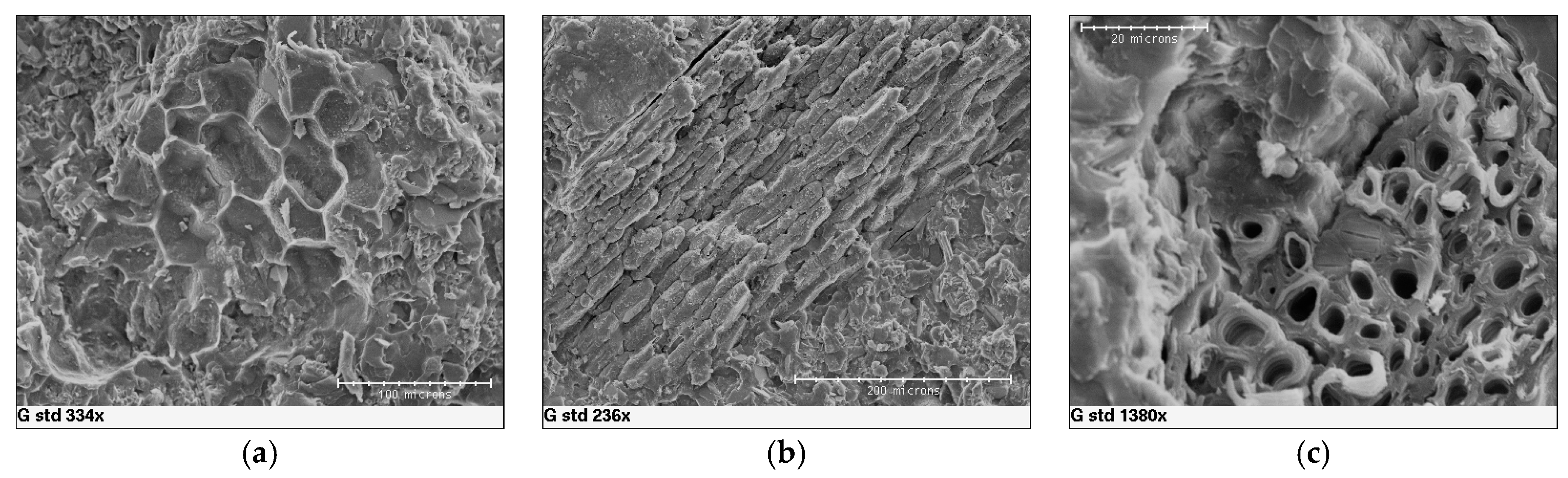

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3. Results

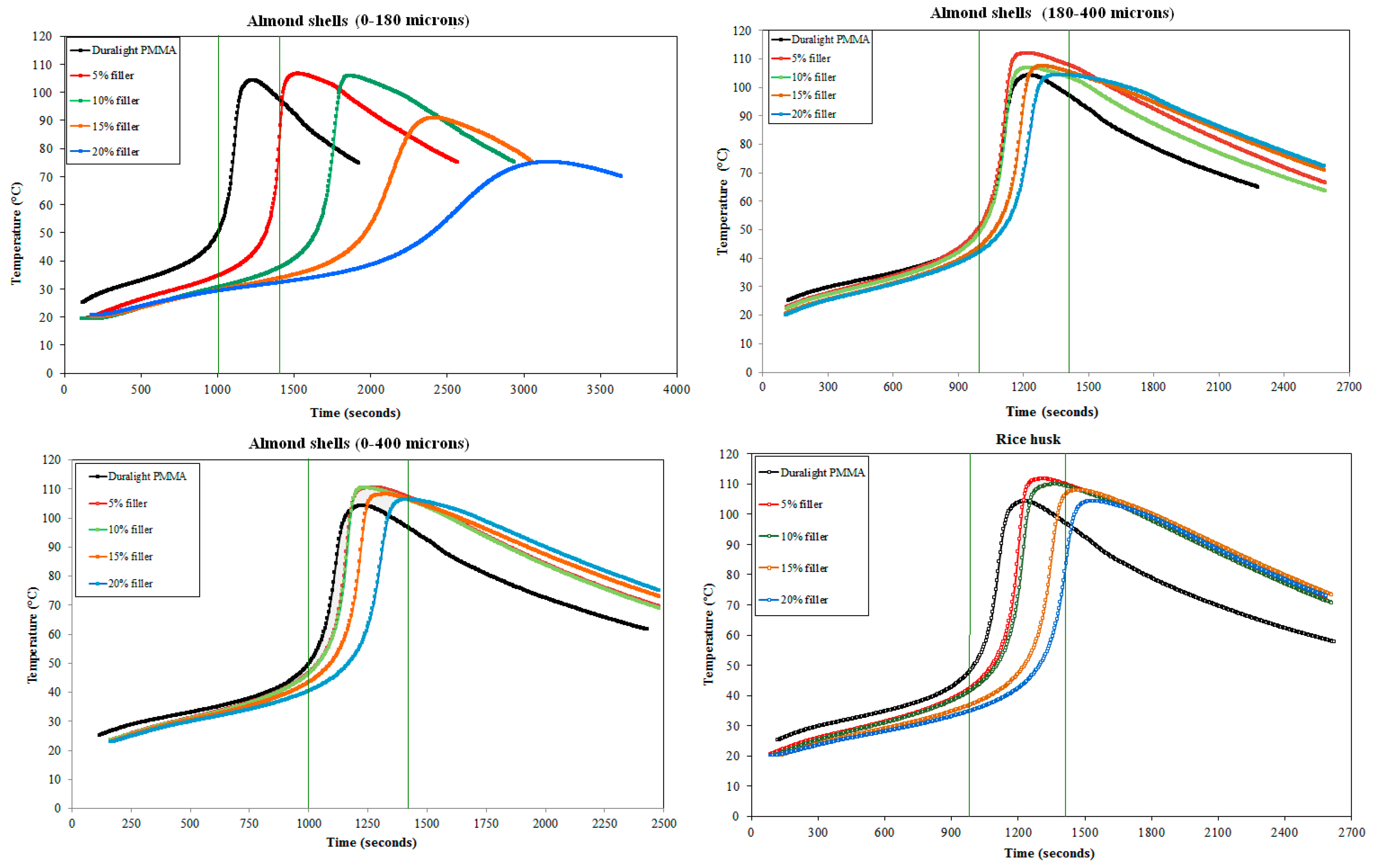

- (1)

- Keeping constant the catalysts amount, the comparison of the rice husk exothermic peaks with the standard Duralight®, makes visible that the reactivity peak obtained with 5 and 10% of rice husk is located in the reactivity range of Duralight®. In order to substitute the highest amount of ATH with the organic filler, the reference formulation contains a 10% of rice husk.

- (2)

- A comparison of the almond shell (0–180 μm) dispersion exothermic peaks with the standard Duralight®, makes visible that the reactivity peak is not reached in the reactivity range of Duralight®. Concerning the temperature, the compliant formulations are those containing 5 and 10% of almond shell (0–180 μm) replacing ATH filler. Hence, the reference formulation contains 10% of almond shells (0–180 μm).

- (3)

- A comparison of the almond shell (180–400 μm) dispersion exothermic peaks with the standard Duralight®, makes visible that all the reactivity peaks are compliant in time and temperature. The reference formulation will contain 15% of almond shells, instead of the 20%, which itself complies to Duralight® standard, because the dispersion with 20% of almond shell has a highly variable viscosity and therefore is likely to have not very consistent properties. This fact can bring to formation of defects during the sheets production (i.e., air bubbles) leading to invalid mechanical characterization.

- (4)

- A comparison of the almond shell (0–400 μm) dispersion exothermic peaks with the standard Duralight®, makes visible that the reactivity peaks obtained with 5, 10 and 15% of almond shells (0–400 μm) are compliant in time and temperature. The reference formulation will contain 10% of almond shells, instead of the 15 or 20%, which themselves comply to Duralight® standard, because the dispersions have high viscosity.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, J.; Jie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, G. Synthesis and characterization of red mud and rice husk ash-based geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindaprasirt, P.; Homwuttiwong, S.; Jaturapitakkul, C. Strength and water permeability of concrete containing palm oil fuel ash and rice husk-bark ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zou, B.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Rong, C.; Wang, Z. A novel mesoporous lignin/silica hybrid from rice husk produced by a sol–gel method. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8402–8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, Z.A.M.; Bakar, A.A. An investigation on the potential of rice husk ash as fillers for epoxidized natural rubber (ENR). Eur. Polym. J. 1995, 31, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsi, S.M.; Pakzad, A.; Amin, A.; Yassar, R.S.; Heiden, P.A. Chemical and nanomechanical analysis of rice husk modified by ATRP-grafted oligomer. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 360, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manap, N.R.A.; Jais, U.S. Influence of concentration of pore forming agent on porosity of SiO2 ceramic from rice husk ash. Mater. Res. Innov. 2009, 13, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Mahender, K.; Mahesh, K. Preparation and thermal stability of poly(methyl methacrylate)/rice husk silica/triphenylphosphine nanocomposites: Assessment of degradation mechanism using model-free kinetics. J. Compos. Mater. 2013, 47, 2027–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, J.A.; Conesa, J.A.; Font, R.; Marcilla, A. Pyrolysis kinetics of almond shells and olive stones considering their organic fractions. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1997, 42, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.; Reguant, J.; Montero, M.A.; Montané, D.; Salvadó, J.; Farriol, X. Hydrolytic pretreatment of softwood and almond shells. Degree of polymerization and enzymatic digestibility of the cellulose fraction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essabir, H.; Nekhlaoui, S.; Malha, M.; Bensalah, M.O.; Arrakhiz, F.Z.; Qaiss, A.; Bouhfid, R. Bio-composites based on polypropylene reinforced with almond shells particles: Mechanical and thermal properties. Mater. Des. 2013, 51, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.M.; García, A.I.; Cabezas, M.A.L.; Reche, A.S. Study of the influence of the almond variety in the properties of injected parts with biodegradable almond shell based masterbatches. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2015, 6, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyziol, L. Fatigue strength of wood polymer composite. J. KONES 2014, 21, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, M.; Tanaka, S.; Miki, T.; Shigematsu, I.; Kanayama, K. Extrudability of solid wood by acetylation and in-situ polymerisation of methyl methacrylate. BioResources 2016, 11, 4025–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothon, R.N. Particulate fillers for polymers. Rapra Rev. Rep. 2001, 12, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.; Tang, J.; Johnson, J.A.; Wang, S. Dielectric properties of ground almond shells in the development of radio frequency and microwave pasteurization. J. Food Eng. 2012, 112, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçin, N.; Sevinç, V. Studies on silica obtained from rice husk. Ceram. Int. 2001, 27, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEUCO GUZZINI S.p.A. Montelupone (IT). Process for Making a Composite Material. European Patent Application EP 2508541 (A1), 12 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, K. The development of the CIE 1976 (L* a* b*) uniform colour space and colour-difference formula. Colouration Technol. 1976, 92, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, M.; Petrović, M.; Krunić, N.; Igić, M.; Janošević, P. Comparative analysis of water sorption by different acrylic materials. Acta Med. Median. 2014, 53, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamoud, A.M. The influence of humidity on the deformation and fracture behaviour of PMMA. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 124, 238–243. [Google Scholar]

- Mezger, T.G. The Rheology Handbook, 2nd ed.; Vincentz Network: Hannover, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sutivisedsak, N.; Cheng, H.N.; Burks, C.S.; Johnson, J.A.; Siegel, J.P.; Civerolo, E.L.; Biswas, A. Use of nutshells as fillers in polymer composites. J. Polym. Environ. 2012, 20, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Rätzsch, M.; Schwanninger, M.; Steiner, M.; Zöbl, H. Yellowing and IR-changes of spruce wood as result of UV-irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2003, 69, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrdy, A.; Kołaczkowski, M. Environmental impacts on the strength parameters of mineral-acrylic (PMMA/ATH) facade panels. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 2015, 134714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-S.; Kim, H.-J.; Son, J.; Park, H.-J.; Lee, B.-J.; Hwang, T.-S. Rice-husk flour filled polypropylene composites; mechanical and morphological study. Compos. Struct. 2004, 63, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Hidalgo, J.; Garmendia, I.; García-Jaca, J. Wood—plastics composites with better fire retardancy and durability performance. Compos. Part A 2009, 40, 1772–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirayesh, H.; Khazaeian, A. Using almond (Prunus amygdalus L.) shell as a bio-waste resource in wood based composite. Compos. Part B 2012, 43, 1475–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rice Husk 0–400 μm | Spindle | Viscosity (cPs) | Temperature (°C) | % Torque min | % Torque max | |||

| 2 RPM | 4 RPM | 10 RPM | ||||||

| 5% | LV3 | 8578 | 8458 | 8182 | 20.6 | 14.3 | 68.2 | |

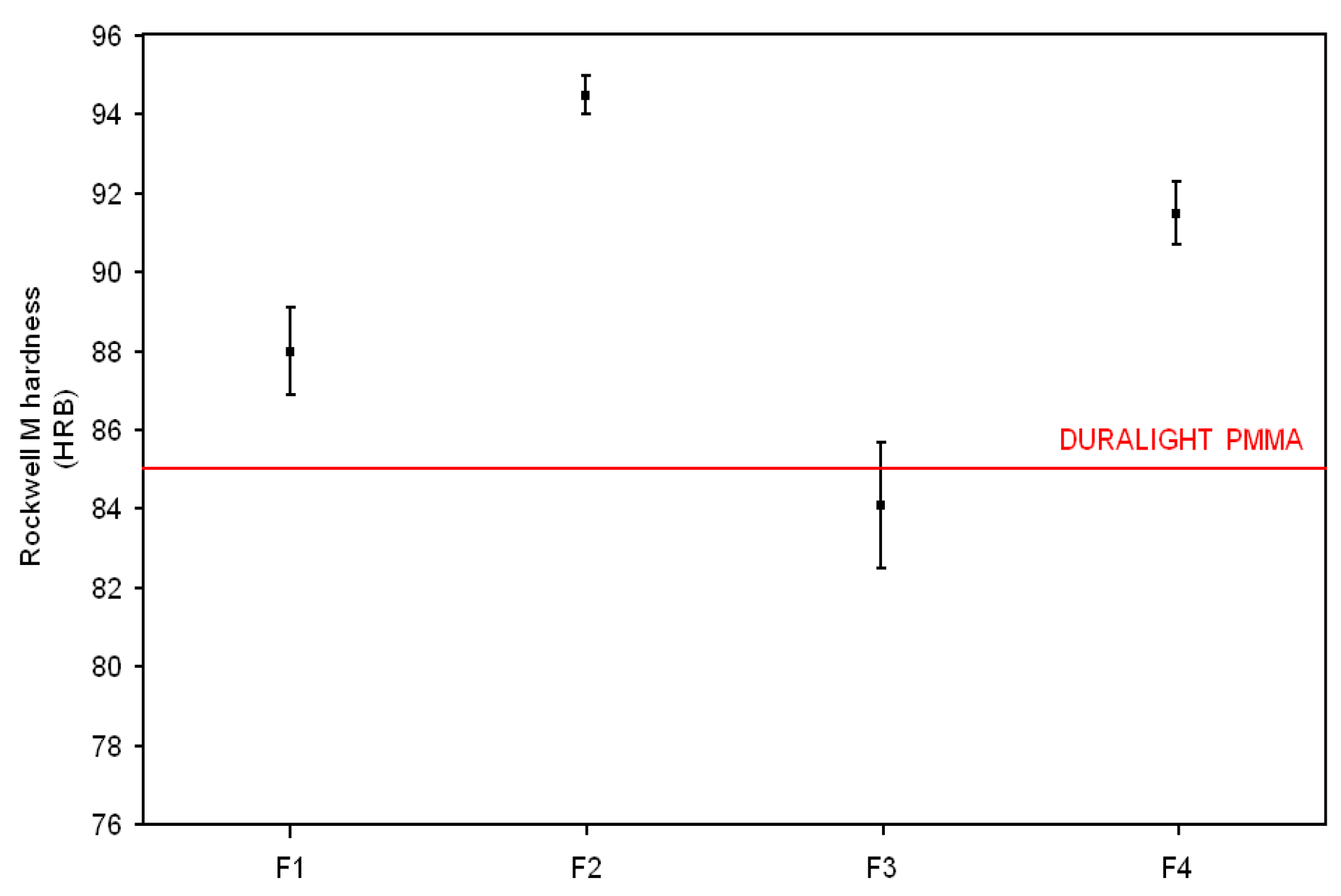

| 10% | LV4 | 14397 | 13197 | 12297 | 19.0 | 4.8 | 20.5 | F1 |

| 15% | LV4 | 30293 | 26994 | 22255 | 20.1 | 10.1 | 37.1 | |

| 20% | LV4 | 48889 | 37342 | 29813 | 21.5 | 16.3 | 49.7 | |

| Almond Shell 0–180 μm | Spindle | Viscosity (cPs) | Temperature (°C) | % Torque min | % Torque max | |||

| 2 RPM | 4 RPM | 10 RPM | ||||||

| 5% | LV4 | 15597 | 14097 | 12237 | 20.5 | 5.2 | 20.4 | |

| 10% | LV4 | 29394 | 24745 | 20576 | 19.7 | 9.8 | 34.3 | F2 |

| 15% | LV4 | 58487 | 46640 | 35272 | 21.2 | 19.5 | 58.8 | |

| 20% | LV4 | 107377 | 84731 | n. d. | 21.4 | 35.8 | 56.5 | |

| Almond Shell 0–400 μm | Spindle | Viscosity (cPs) | Temperature (°C) | % Torque min | % Torque max | |||

| 2 RPM | 4 RPM | 10 RPM | ||||||

| 5% | LV3 | 10138 | 9298 | 8146 | 21.5 | 16.9 | 67.9 | |

| 10% | LV3 | 14217 | 12927 | 11313 | 22.3 | 23.7 | 94.3 | F3 |

| 15% | LV4 | 25195 | 21145 | 17156 | 22.1 | 8.4 | 28.6 | |

| 20% | LV4 | 32093 | 27864 | 23694 | 21.3 | 10.7 | 39.5 | |

| Almond Shell 180–400 μm | Spindle | Viscosity (cPs) | Temperature (°C) | % Torque min | % Torque max | |||

| 2 RPM | 4 RPM | 10 RPM | ||||||

| 5% | LV3 | 9778 | 9088 | 8182 | 20.4 | 16.3 | 68.2 | |

| 10% | LV3 | 9538 | 8728 | 8254 | 20.3 | 15.9 | 68.8 | |

| 15% | LV3 | 12777 | 10888 | 9586 | 20.8 | 21.3 | 79.9 | F4 |

| 20% | LV4 | 12597 | 10798 | 9478 | 22.1 | 4.2 | 15.8 | |

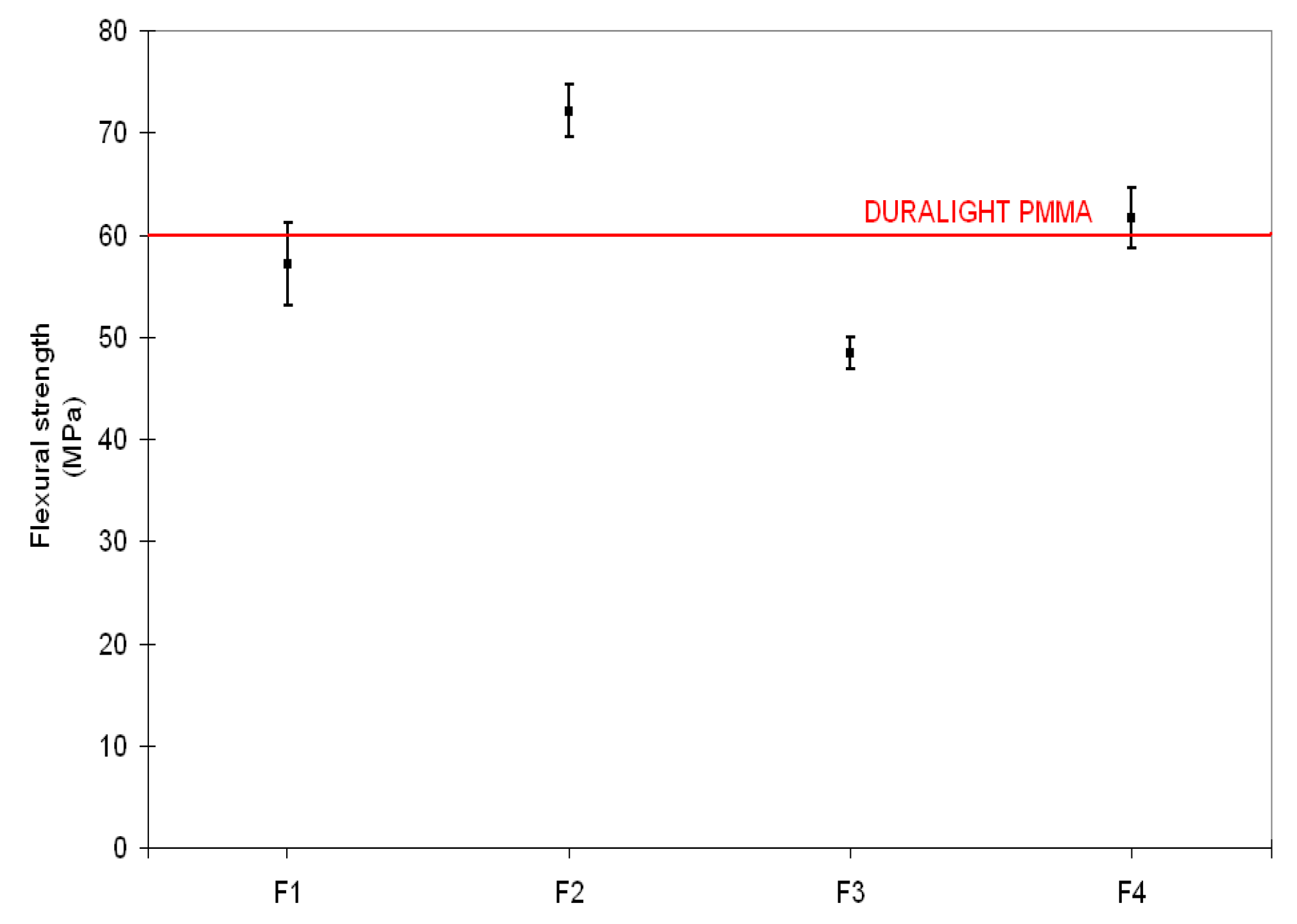

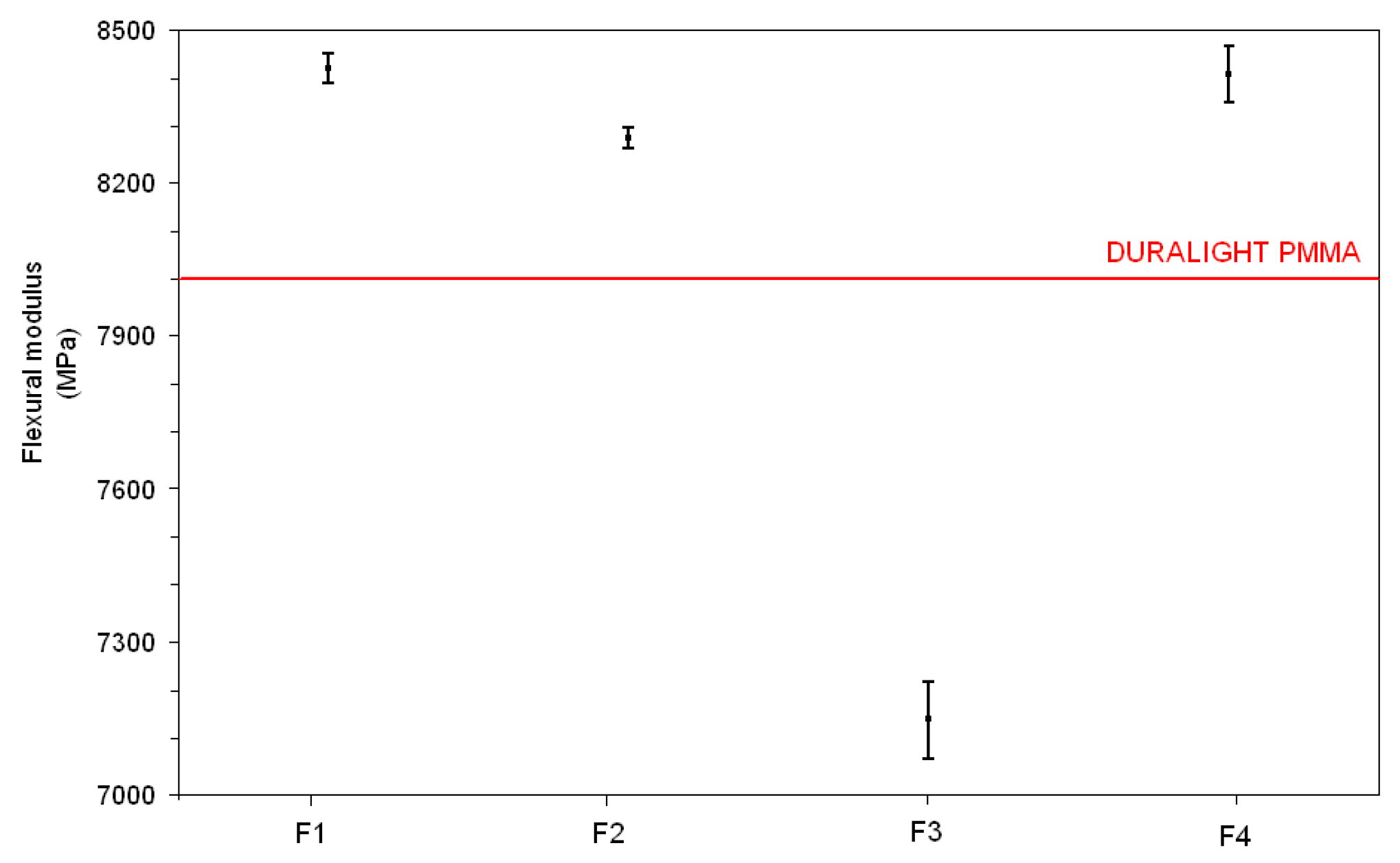

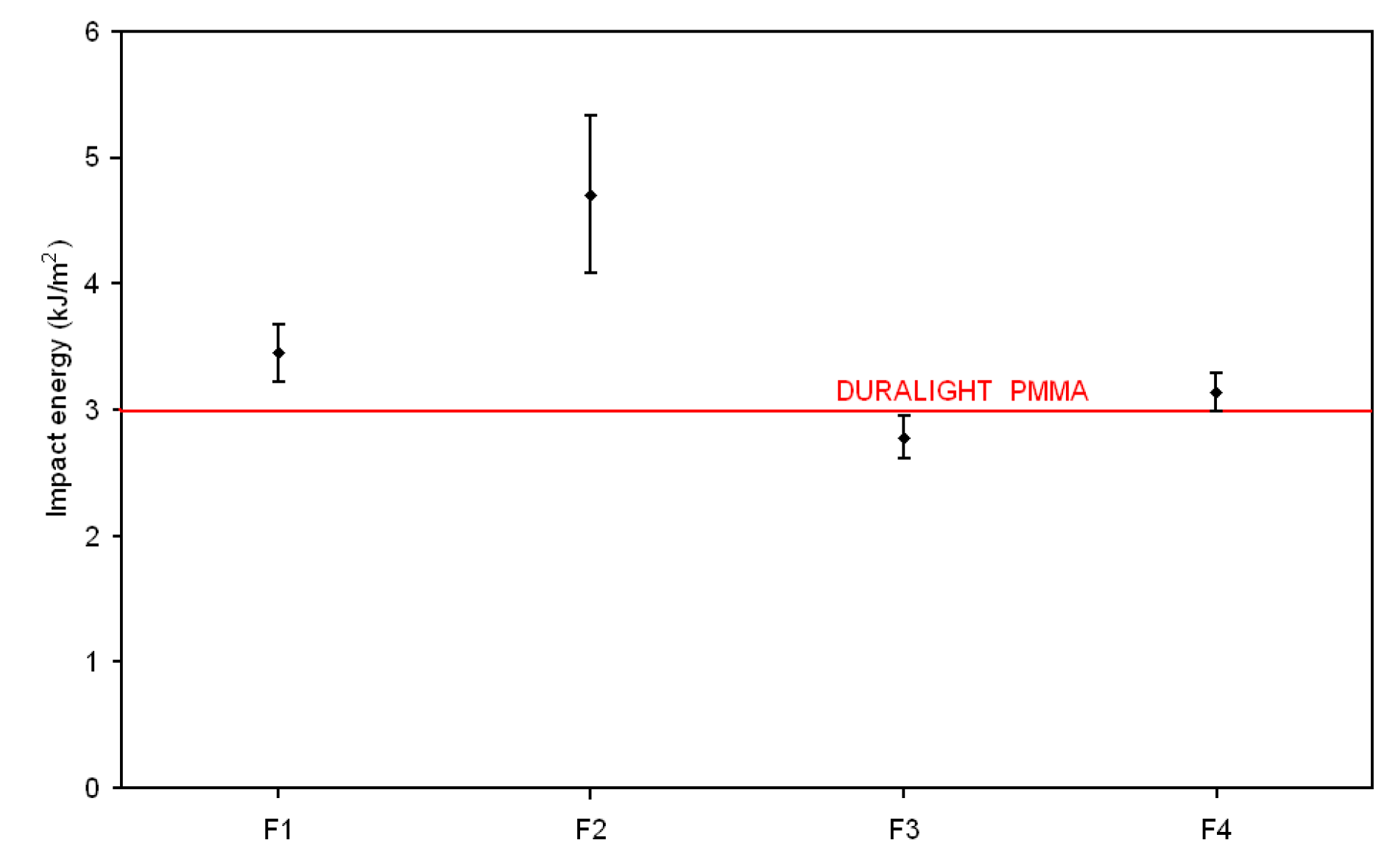

| Component | F1 (%) | F2 (%) | F3 (%) | F4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylic resin | 36.35 | 36.35 | 36.35 | 36.35 |

| Pre-treated ATH (20 µm grade) | 52 | 52 | 47 | 52 |

| Rice husk 0–400 μm | 10 | |||

| Almond shell (0–180 μm) | 10 | 5 | ||

| Almond shell (180–400 μm) | 15 | 5 | ||

| Peroxide | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Accelerator | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Activator | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Exposure | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 250 h | ΔL | 0.86 | −0.47 | 0.54 | 0.51 |

| Δa | −0.16 | 0.14 | −0.61 | −0.38 | |

| Δb | 1.24 | −0.28 | 0.72 | −0.45 | |

| ΔE | 1.52 | 0.56 | 1.08 | 0.78 | |

| 500 h | ΔL | 1.70 | −0.25 | 1.64 | 1.81 |

| Δa | −0.20 | 0.46 | −1.13 | −0.76 | |

| Δb | 1.21 | 0.23 | −0.40 | −0.71 | |

| ΔE | 2.10 | 0.57 | 2.03 | 2.08 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sabbatini, A.; Lanari, S.; Santulli, C.; Pettinari, C. Use of Almond Shells and Rice Husk as Fillers of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA) Composites. Materials 2017, 10, 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10080872

Sabbatini A, Lanari S, Santulli C, Pettinari C. Use of Almond Shells and Rice Husk as Fillers of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA) Composites. Materials. 2017; 10(8):872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10080872

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabbatini, Alessandra, Silvia Lanari, Carlo Santulli, and Claudio Pettinari. 2017. "Use of Almond Shells and Rice Husk as Fillers of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA) Composites" Materials 10, no. 8: 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10080872

APA StyleSabbatini, A., Lanari, S., Santulli, C., & Pettinari, C. (2017). Use of Almond Shells and Rice Husk as Fillers of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA) Composites. Materials, 10(8), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10080872