1. Introduction

Diluted magnetic semiconductors (DMSs) have attracted much attention in optoelectronic and spintronic applications. These promising materials represent potential candidates designated to be typical half-metallic ferromagnets with 100% spin polarization at the Fermi level and this behavior is related to the incorporation of a convenient doped atom. Furthermore, the semiconductors substituted by 3d transition metals (TMs) turn salient, owing to the feasibility of merging magnetism and semiconductor features [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The 3d-TM doped III-V compounds behave as III-V DMS, which captivated a tremendous amount of attention for a viable growth in efficient and miniaturized electronic devices [

16]. Various DMS materials [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] have been exhaustively explored from theoretical and experimental perspectives with the purpose of designing powerful devices such as outstanding smart memory chips, super smart diodes, spin valves, and spin field-effect transistors. Accordingly, it is necessary to find an appropriate system designed for fabricating spintronic devices. A good doping level of GaAs leads to the production of volatile memory chips [

15]. It is also feasible to utilize gallium nitride (GaN)-doped dilute magnetic semiconducting films in magneto-optical applications. The intended usage is in the form of room temperature ferromagnetic layers for a spin-polarized light emitting diode. Thus, it is essential to dope the host GaN film with manganese for these layers, while still maintaining a good crystallinity and semiconducting features with room temperature ferromagnetic properties. After the revelation of half-metallicity in a semi-Heusler alloy [

5], many considerations were emphasized for examining the electronic and magnetic features of various kind of systems in order to discover new half-metallic ferromagnets [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. It was ascertained that the most feasible doping percentage of GaAs systems with Mn dopants is approximately 10% or 20% since they exhibit a hysteric response to an applied magnetic field. Subsequently, the researchers paid further attention to investigating the III-V-based DMS and profound endeavors were effectuated by synthesizing ferromagnetic semiconductors over decades [

2,

3,

4,

5].

In the recent years, the scrutiny on TM doped III-V DMS was intensified in order to discover novel half-metallic ferromagnetic (HMF) materials with a high Curie temperature (

TC), and to enhance their ferromagnetic characteristics [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. It is compulsory to add a considerable amount of magnetic elements (a few percent or more), surpassing the solubility limit in III-V semiconductors, in order to inspect the magnetic cooperative mechanism in DMSs. In the group of III-V semiconductor compounds, gallium phosphide (GaP) represents an interesting system composed of a cubic zinc blende (ZB) structure and it has broad usages in cellular phones and electronic equipment such as semiconductor lasers and optoelectronic devices, etc. GaP is regarded as a convenient host compound to design DMS material and this could be effectuated through doping by TMs, as corroborated via several theoretical and experimental reports [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Based on AC magnetization measurements, the affirmation of a ferromagnetic state in bulk sintered GaP substituted by 3% Mn is procured at

TC of 600 K, which is substantially larger than the previous examinations. The field location and line width of the resonance exhibited a significant temperature related to ferromagnetic resonance spectroscopy (FMR) spectra. Further validation of high temperature ferromagnetism has been detected via a non-resonant derivative signal centered at zero field at 600 K. Significantly, the occurrence of ferromagnetism is joined to the dilute partition of Mn

2+ in the sample and not from the clusters of Mn

2+ or other related impurities [

14,

24,

25,

26]. Subsequently, the augmentation in the electron conductivity of the GaP semiconductor could take place by doping with impurities that possess magnetic properties, such as manganese. The occurrence of a ferromagnetic state in these systems would be fruitful for designing novel microelectronics. During the last few years, extensive theoretical and experimental inspections have been concentrated on the magnetic properties of Mn-doped III-V semiconductors.

It would be valuable to explore gallium manganese phosphate (Ga

1−xMn

xP) alloys with a specific proportion of manganese atoms owing to their technological applications in electronic devices. First-principle calculations of various III-V-DMS compounds have been carried out using the Korringa Kohn Rostoker-Coherent Potential Approximation (KKR-CPA) method, as reported in Ref. [

27]. According to their results, the substitutional Mn in AlP, GaP, and InP systems with a composition of 5% illustrates ferromagnetism at room temperature. Based on both full-potential and pseudopotential schemes, a systematic study of the magnetic features of 3d-TM doped GaAs and GaP materials has previously been carried out [

26,

28]. Hence, the emergence of the ferromagnetism at room temperature, was identified in GaAs and GaP compounds doped by Cr-, V-, and Mn-elements with a concentration of 25%. Intriguingly, these materials could be prospective candidates for spintronic technology applications. In the past two decades, the origin of ferromagnetism in Mn-doped III-V semiconductors is still being investigated, and it is imperative to scrutinize the related electronic properties. Consequently, the examination, computational modeling, and simulation process are carried out because of the difficulty in the synthesis, growth, and characterization of Mn-doped III-V semiconductors. The prediction of numerous attitudes of systems is facilitated by the usage of computational techniques and recent advanced ab-initio calculations. The computational methods have already been employed for various systems by means of the first principle calculations and the theoretical works were consistent with the experimental results. Thus, we are motivated to verify the magnetic response and half-metallic character based on the density functional theory (DFT) approximation.

The experimental measurement of TM-doped GaP [

26] triggered our motivation to analyze the magnetic response and half-metallic character. Furthermore, the solubility limit of TMs in III-V based DMS materials was less than 4% [

26]. Hence, it is essential that the dilute limit of the Mn-doped GaP system is less than 4% for producing credible data and to support the experimental works [

26]. Accordingly, we report a theoretical investigation regarding the electronic structure and magnetic properties of Mn-doped GaP with a doping concentration of

x = 0.03, in addition to higher concentrations

x = 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75. The other goal of current scrutiny is to inspect the change of half-metallicity with the variation of composition until the dilute limit. The examination of magnetic origin in semiconductors with nonmagnetic atoms relies on p-d hybridization, which is the main contributor to HMF. In this work, the examination of the electronic and magnetic features of Ga

1−xMn

xP (

x = 0.03, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75) alloys is handled by employing DFT [

29] in the framework of the all-electron full potential linear augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method. The latter is embodied in the WIEN2k code [

30], which has been demonstrated to be one of the most exact techniques for computing the electronic structure of materials. Accordingly, we applied the state-of-the-art generalized gradient approximation (GGA) combined with Hubbard U approach, and the on-site Coulomb interactions approach [

31,

32,

33,

34] was implemented in the FP-LAPW plus a local orbital method (lo) [

30]. We computed the electronic density of states and magnetic characteristics of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys using the FP-LAPW + lo technique [

30] with both GGA and GGA + U techniques. We thoroughly analyzed the results and predicted the magnetic properties, which are based on the inspection of the density of state results and magnetic moments.

The eventual usage of electron spin within the electronic charge in contemporary devices has resulted in a prominent concern regarding DMS materials. The straightforward knowledge regarding the electronic states of a specific atom would be attainable through X-ray absorption spectra (XAS). Over the past few years, theoretical reports have been carried out on (Ga,Mn)As DMSs to elucidate the measured XAS [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Therefore, we aim to perform ab-initio calculations to examine the electronic structural characteristics of the Mn K-edge X-ray absorption spectrum in Mn-doped GaP material. In the present work, the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra of Mn- in Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys will be elucidated, which could be compared to other half-metallic systems. Subsequently, to reveal this behavior and to shed light on the mechanism of the prominent magnetic properties of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys, we analyze the X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) features for the Mn K-edge spectra. This scrutiny provides the first theoretical indication of XANES spectra at the Mn K-absorption edge in Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys. This finding has been ascertained in previous experimental measurements of the Mn K-edge in GaMnAs.

The paper is organized as follows. The computational details of the employed method will be briefly portrayed in the following section. Using GGA and GGA + U techniques, the magnetic and electronic aspects, essentially the density of states (DOS), will be discussed in

Section 3. The resulting magnetic properties and the Mn K-edge X-ray absorption spectra of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys are also reported with the GGA + U approach. We will end with the conclusions regarding the electronic structure and magnetism of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys.

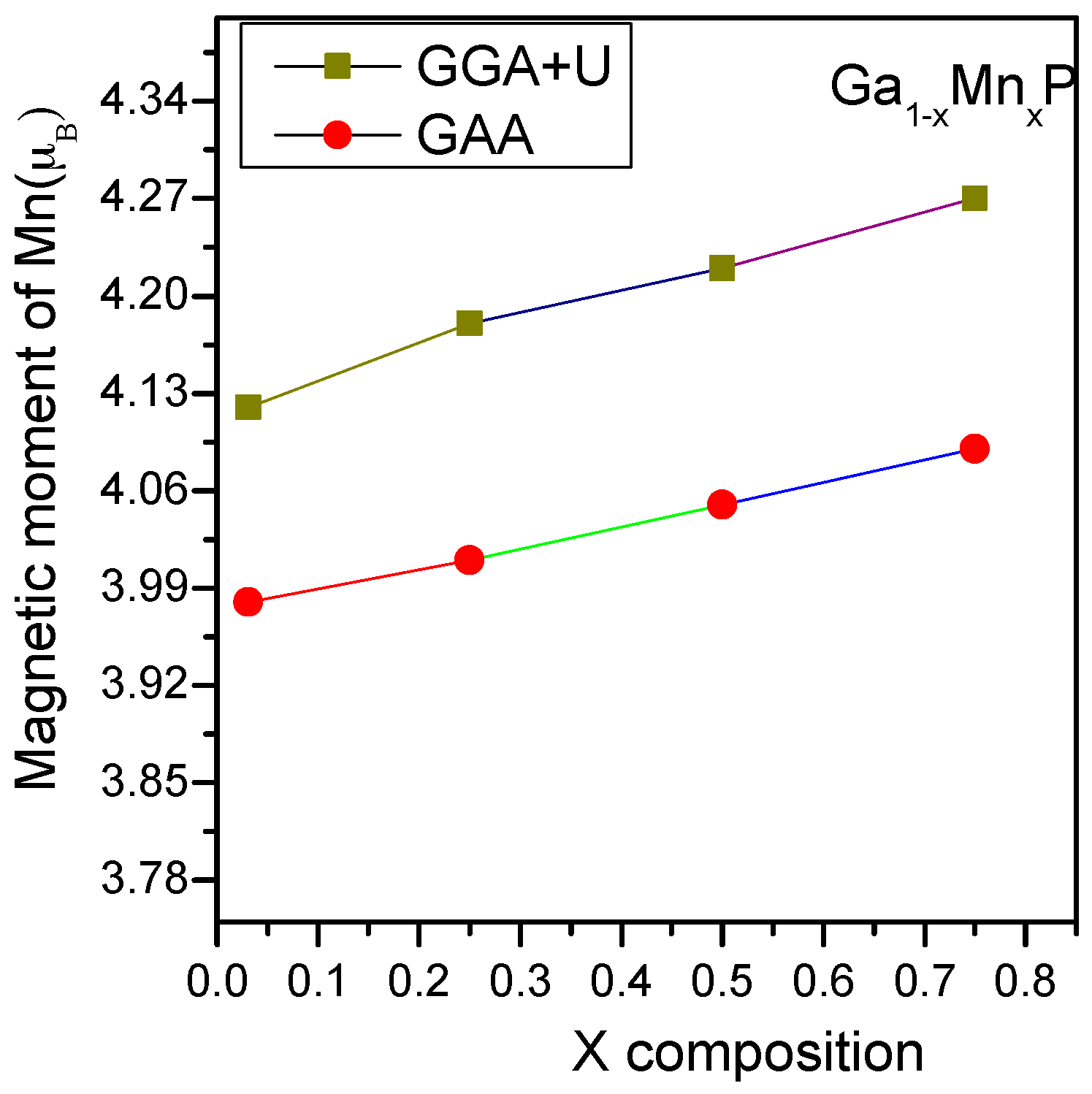

3. Results and Discussion

Using both GGA and GGA + U electronic structure calculations, the lattice parameter of the supercell was optimized in order to compute the electronic and magnetic properties of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys with

x = 0.03, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75. The spin-polarized calculations are handled to evaluate the on-site magnetic moment at the Mn sites for all ferromagnetic structures. For all the studied alloys, the local magnetic moments on the Mn atoms of ferromagnetic states are depicted in

Figure 1. It is remarkable that the results of local moments on Mn atoms determined by GGA + U are slightly higher than those computed with the GGA technique. This is mainly owing to the inclusion of the d-d Coulomb correlation in the Mn atom when using the GGA + U technique. It is evident that a global magnetic moment of approximately 4µ

B is acquired per supercell for all the systems under investigation, which is in gratifying conformity with previous works [

24,

25,

26,

27]. As anticipated, the Mn-doping element represents the major contribution to the global magnetic moment with the change of doping concentration. From

Figure 1, it is evident that by varying the composition of Mn in the GaP system, the localized magnetic moment (GGA + U) displays a small variation in the range of 4.10 µ

B or 4.26 µ

B owing to the larger volume of Ga compared to Mn. This could probably lead to the preference of ferromagnetic order of the manganese atom in the GaP system. In all the studied alloys, the phosphorous neighbors of Mn together induce an insignificant contribution between −0.05 µ

B and −0.09 µ

B, although the Ga second neighbors of Mn together contribute very weakly in the range of 0.04 µ

B–0.07 µ

B to the magnetic moment. In the case of the substitution of a tetravalent Mn-atom instead of a trivalent Ga element, three electrons are considered to set a bonding with P elements and the rest of the electrons are located in the additional states at

EF, which develops magnetic states in the concerned alloys. The Mn-3d states represent the major cause of magnetism in Ga

1−xMn

xP (

x = 0.03, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75) alloys, apart from the p-d hybridization. Moreover, the magnetic behavior of these alloys may be associated with the partially filled t

2g orbitals of Mn-3d states [

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, the emerged magnetic moment on the Ga-/P-element is negligibly insignificant, aligning parallel/antiparallel to the Mn-element, respectively. The present findings assume that the developed magnetism is owing to the exchange interaction between Mn-atoms and the host material. It is also essential to emphasize that this behavior could significantly contribute to determining the inspected spintronic effect [

1,

2,

3,

4].

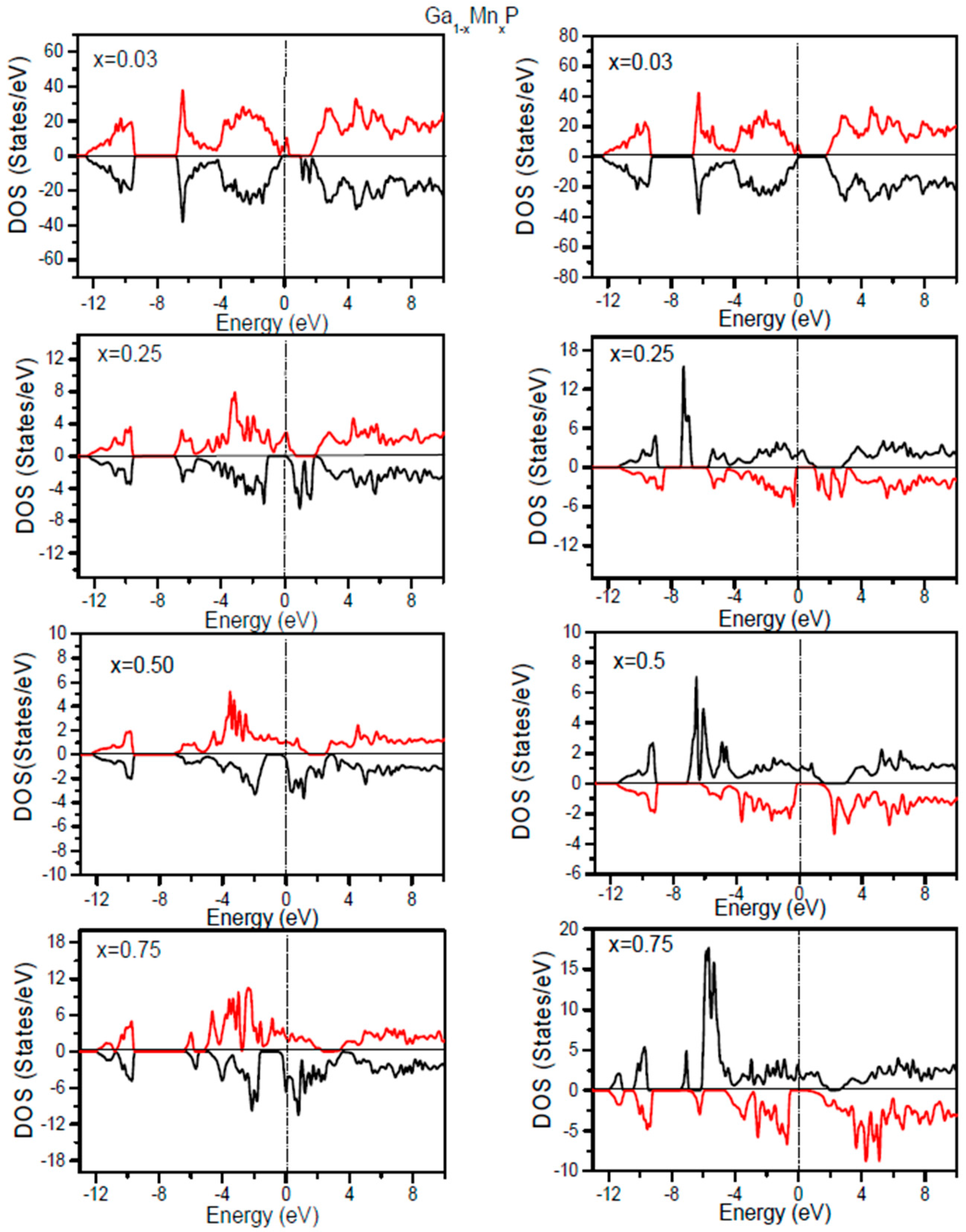

For the comprehension of the electronic structures of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys, it is informative to scrutinize the associated densities of states. By means of the GGA + U approach, the Coulomb interaction effect of the correlation of 3d electrons could be evinced in the total densities of states (TDOS). It is compulsory to discern the magnetic nature of the considered alloys. On the basis of optimized lattice constants, the spin polarized electronic density of states and robustness of half-metallic aspects are computed. In order to acquire a profound vision into the variation of the electronic structure of the ferromagnetic Ga

1−xMn

xP (

x = 0.03, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75) alloys, we calculate the total TDOS using the GGA and GGA + U approaches, as plotted in

Figure 2. Based on the aid of the DOS, it is essential to comprehend the source of states of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys. Evidently, the more electrons are located in the spin-up (↑) state comparatively to the spin-down (↓) state. The occurrence of a band gap around

EF for the minority-spin channel of Ga

1−xMn

xP (

x = 0.03, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75) has been revealed in the resulting GGA + U DOS, whereas some valence states cross

EF for the spin-up state and relocate to the conduction states. Subsequently, these promising materials are predicted to possess a HM aspect. The TDOS of the considered alloys at low doping Mn compositions illustrates an energy gap in the spin-down state owing to the splitting of DOS at

EF, which consequently conducts to HM systems. Note that the binary GaP compound has a semiconducting nature possessing a band gap of 2.32 eV [

14,

26,

27]; whereas its corresponding features are drastically altered by doping with an Mn-atom. It is observed that the incorporation of manganese yields supplementary states in the uppermost section of the valence states for the majority-spin and the downward region of valence states for the minority-spin component, thus leaving a band gap. Therefore, the addition of Mn atoms in the system maintains the semiconductor aspect of GaP for the spin-down state. The metallic character in the spin-up states and semiconductor nature in spin-down states yield Ga

1−xMn

xP ternary alloys as realistic HM ferromagnets. It is evident that the TDOS computed with the GGA + U indicates an HM state for the minority spin channel at various

x compositions, whereas the states near

EF display splitting and the HM gap are increased in comparison with the TDOS results calculated by means of the GGA. This situation is attributed to the correlation effects, which are important in 3d states of Mn. Note that the HM-behavior is present at a low composition of Mn in the GaP compound, whereas the increase of Mn content leads to a metallic state with GGA. Owing to the emergence of this specific mechanism, these prosperous materials are practical for producing a thoroughly spin polarized current. Moreover, they are reliable for maximizing the efficiency of spintronic devices.

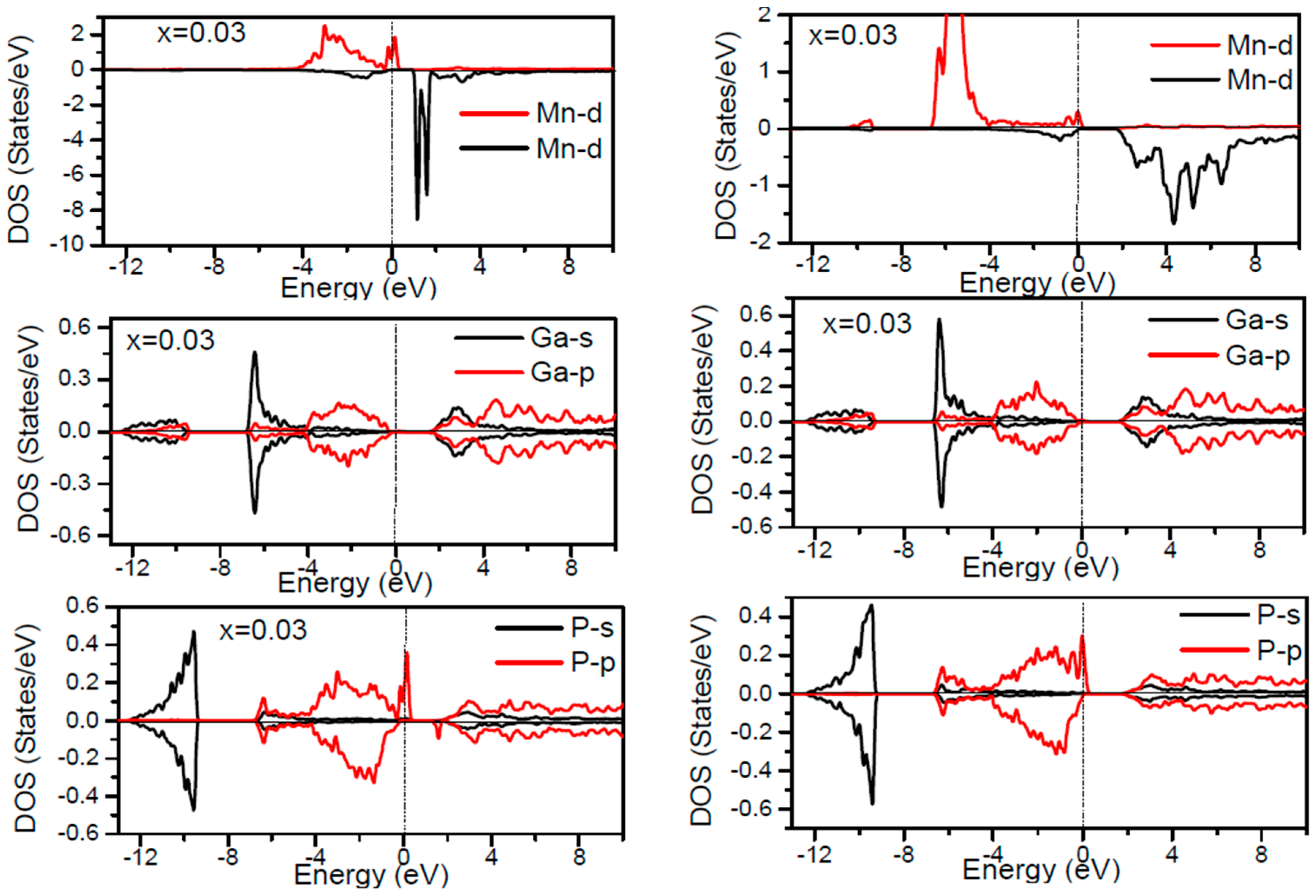

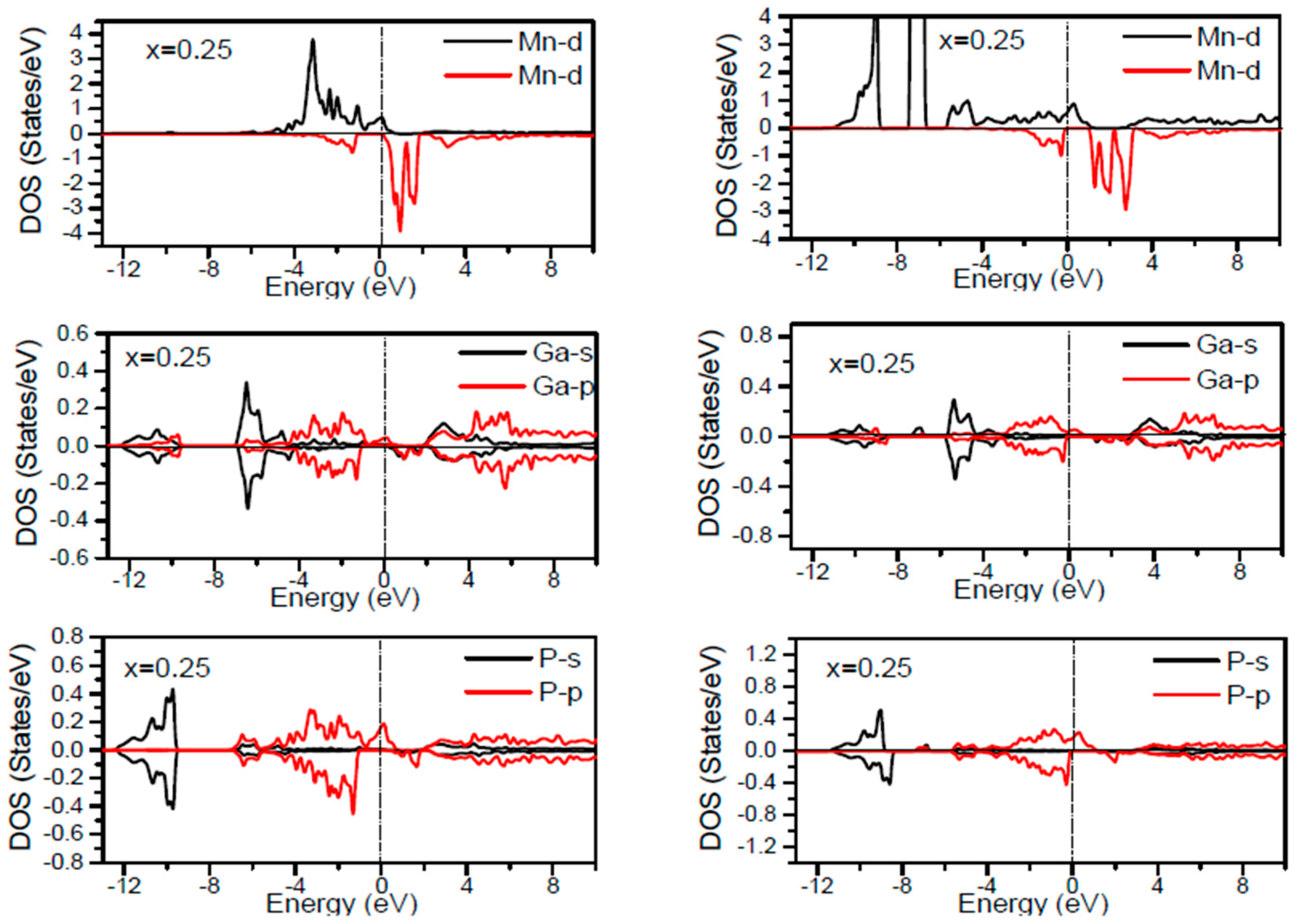

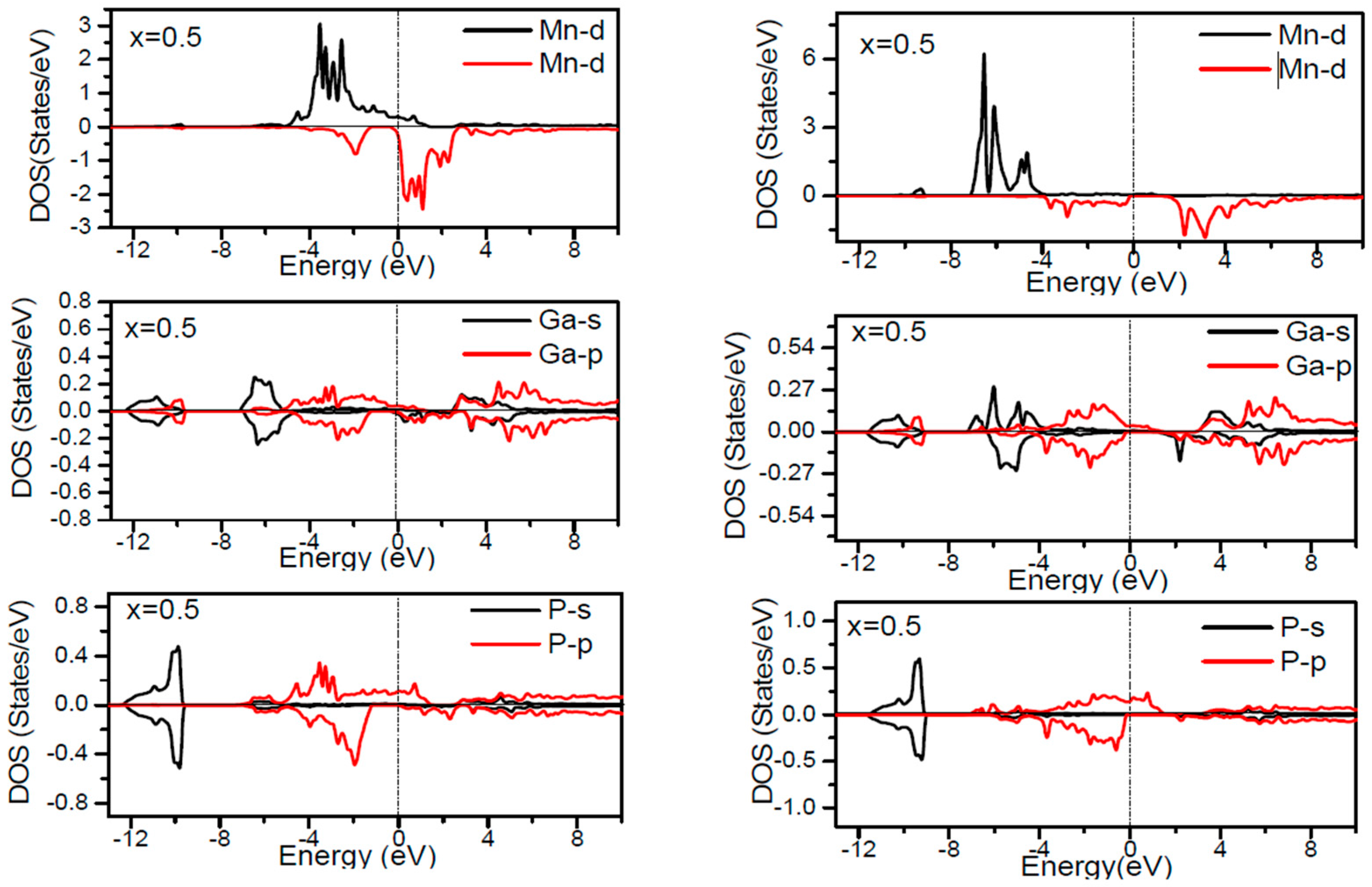

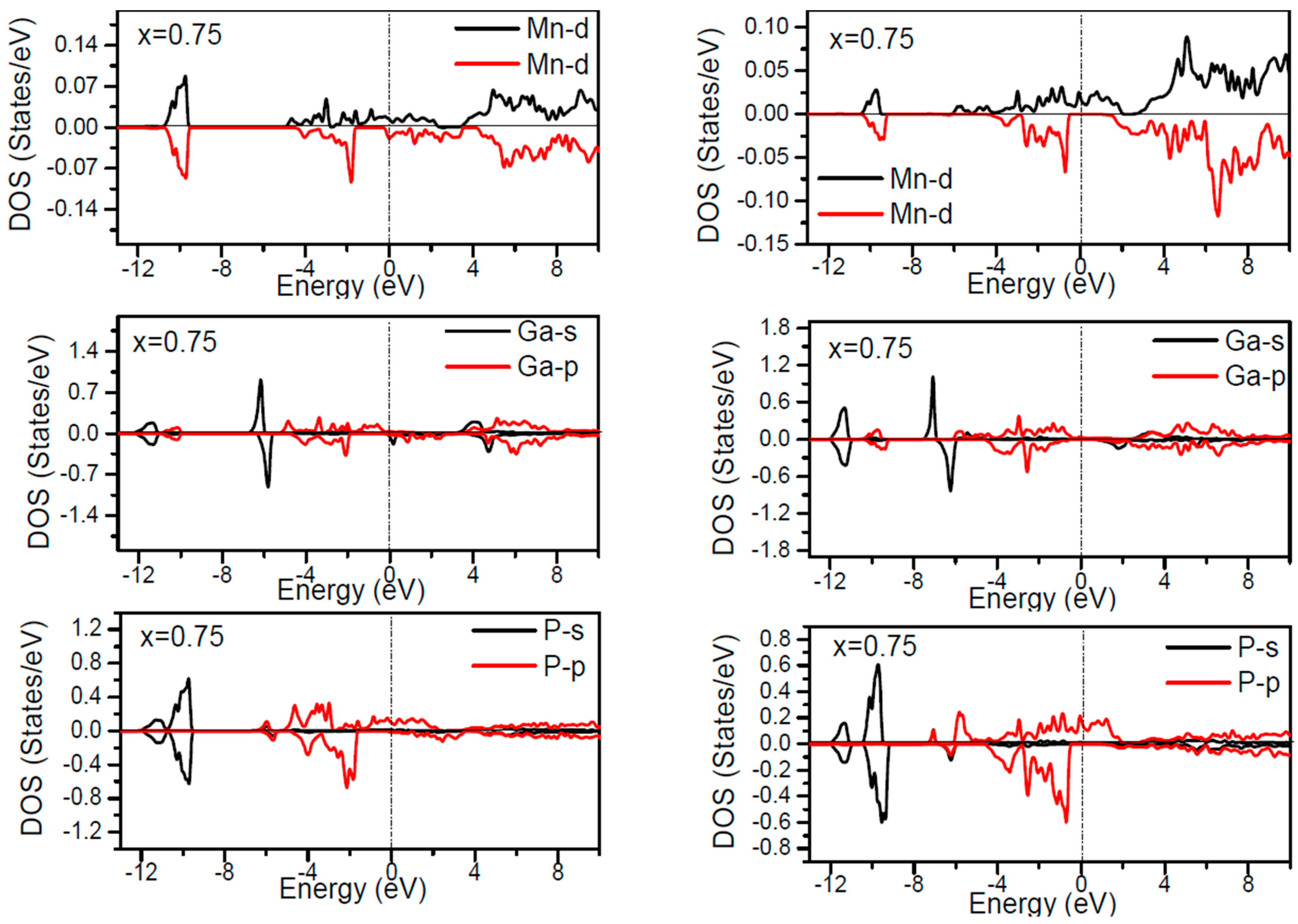

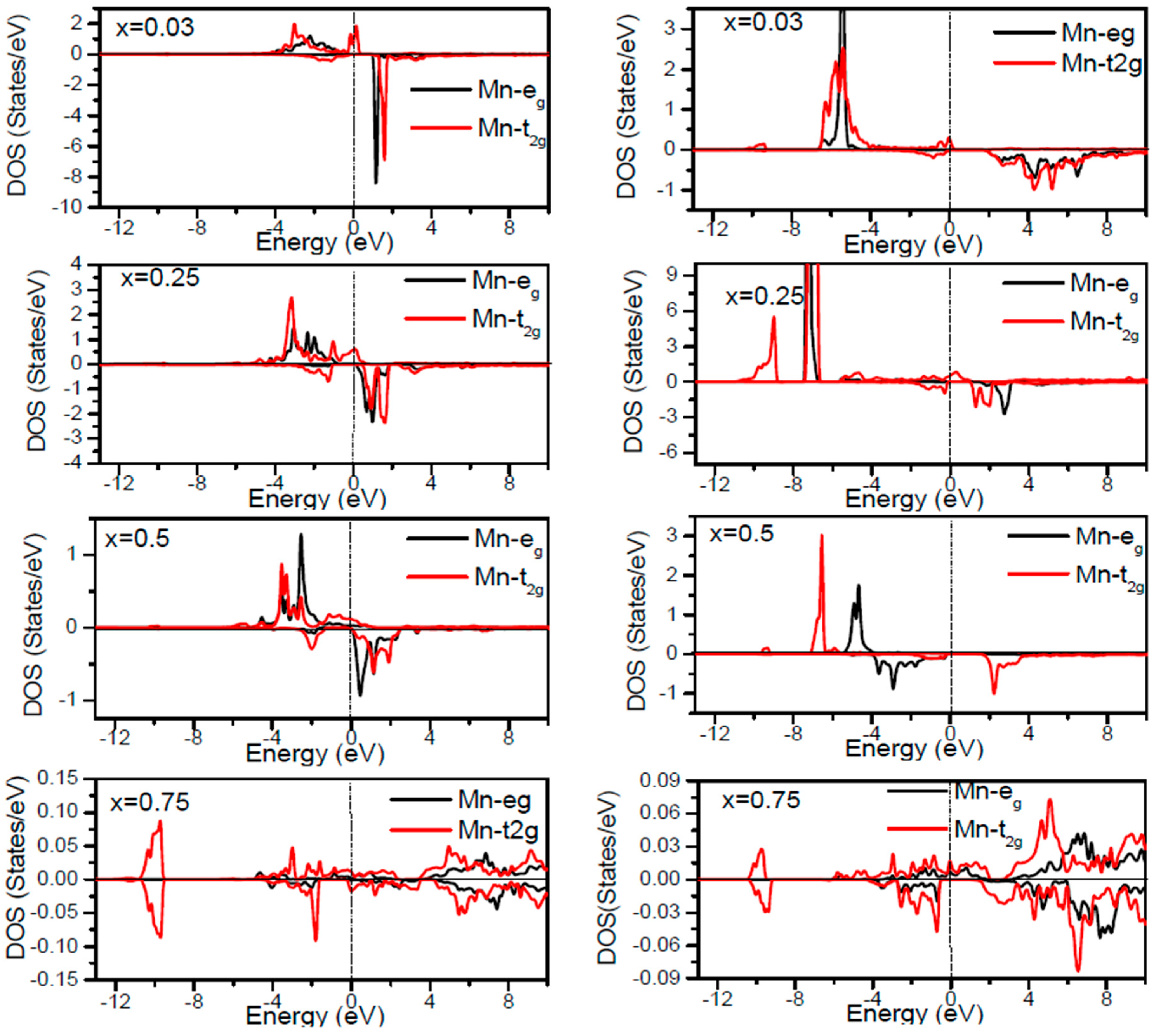

In order to inspect the assistance of different states responsible for the HM character of these systems near

EF, the spin dependent partial DOS (PDOS) of Ga

1−xMn

xP (

x = 0.03, 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75) materials are depicted in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 by employing the GGA and GGA + U approaches. It is evident that the states in the locality of

EF are predominantly due to Mn-3d and P-p levels, with an insignificant participation from the Ga-p levels for the majority spin component (as seen in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In the spin-up states, the bands at

EF illustrate a mixture of Mn-d and P-p like states, which play a valuable role for implying the magnetism at all the various compositions. From the computed DOS, the P-s and Mn 4s states are repelling each other. The P-s state is moved close to the core and Mn-4s into

EF. As is apparent, the uppermost valence band (VB) and lower conduction band (CB) of the minority spin components show that the Mn-d and P-p bands are the most responsible to determine the energy band gap at

EF. Note that the contribution of Ga-s, Ga-p, and P-s bands is mostly insignificant for both spin components. The PDOS computed with GGA + U illustrates a HM state for the minority spin channel at various

x compositions. The states close to

EF are also split and the HM gap is increased compared to the results produced with the GGA. Subsequently, by increasing the Mn- composition from 0.25 to 0.75, the spin-up d-states split and their effective assistance at

EF increases. By the virtue of the theory of crystal field splitting, the emerged HM ferromagnetism in this striking material is assessed through the splitting of P ions. In fact, this would drive to the conversion of 5-fold degenerated Mn-3d orbitals into 3-fold degenerated t

2g (d

xy, d

zx, d

yz), states and doubly degenerated e

g (d

z2, d

x2−y2) states, as clearly noticed in

Figure 7.

According to the DOS results, there are hybridized Mn-3d levels with a P-3p neighbor level of Mn in the case of Mn-doped GaP materials. It is evident that the DOS ranging between −5.5 and 1.5 eV is essentially reflected by the Mn-d and P-p orbitals, with a relatively insignificant participation of Ga-p levels at both spin states (see

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The assistance of Mn-3d states in the spin-up states is separated into two sections: first, the states emerging through the Mn-3d (e

g-doubly degenerate orbitals) states lie at approximately −1.81 eV, and second, the location of Mn 3d t

2g-triply degenerate states, roughly at −0.46 eV, is positioned upward of e

g states (see

Figure 7). Subsequently, these states exhibit a strong hybridization of wave functions for t

2g state and weak hybridization for e

g states, with P-p states leading to the occurrence of bonding and anti-bonding hybrids. Thus, this hybrid conducts to a shift in the valence states of the concerned alloys to higher energies. The extra Mn doped GaP displays a significant repulsion between bonding and anti-bonding states. The hybridization between these states essentially contributes to the determination of ferromagnetic behavior in these materials for various dopant compositions

x. Owing to the considerable p-d hybridization, the partially occupied Mn-t

2g antibonding orbitals participate in the formation of the band gap. This latter is subject to the splitting of the two symmetry states in the spin-down component and thereby the half-metallic gap occurs. However, in these alloys, the net magnetic moment and HM behavior are characterized by the partial occupancy of spin-down state at

EF. As demonstrated in previous research [

24,

25,

26,

27], the d-orbitals of the Mn atom are majorly positioned in the band gap, and they may be separated via the crystal field and exchange interaction. The crystal field produced via the four P nearest-neighbors yields the splitting of Mn-d levels into doubly degenerated e

g states and triply degenerated t

2g states (

Figure 7). Accordingly, the substantial interaction between the 3d-t

2g orbitals of Mn and P-3p orbitals leads to the pushing up of the 3d-t

2g states upward of the e

g states [

15,

16,

17,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The computed GGA + U band gap of minority spin varies between 1.7 and 0.8 eV when varying the

x concentration. However, for a high Mn composition, the compound shows a high spin polarized state within the GGA technique. It is concluded that the studied alloys own ferromagnetic behaviors, which are in good accordance with the previous finding reported experimentally [

14,

24,

36].

Moreover, the presence of a half-metallic gap, which indicates a minimal gap for spin excitation in the minority-spin channel, is an impressive characteristic of these promising systems. To understand the HM nature of these materials, the minimum value of (

EF − E

vtop) or (E

ctot −

EF) should be computed, where E

vtop and E

ctot denote the energy associated with the uppermost valence states and downward conduction states, respectively. In different way, the control of realistic HM ferromagnet is attributed to a non-zero HM gap relatively to the band gap in any spin channel [

12,

15,

17,

24,

25,

26,

27]. On the basis of this deliberation, it is surmised that the augmentation of

x content in Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys from 0.03 to 0.75 leads to the half-metallic nature in these corresponding systems by using the GGA + U approach. However, the presence of a HM gap is found at a low content of Mn when using the GGA approach. Notably, our results illustrate half-metallicity in Ga

0.50Mn

0.50P and Ga

0.25Mn

0.75P alloys by using the GGA + U approach, whereas the previous studies found a metallic state in these systems by using the LSDA approach, which confirms our results [

24,

25,

26]. Our GGA energy gaps are smaller than those obtained with the GGA + U approach since the d-d Coulomb correlation is important for the 3d-state of Mn. The resulting band gap is approximately 1.7 eV for the dilute limit of the magnetic compound (

x = 0.003). It is evident that doping with TM leads to the diminishing of the band gap to a lesser extent than that of the pure GaP compound, i.e., 2.3 eV [

26]. Within the GGA + U approach, a reduced band gap has been detected at approximately 0.8 eV in the minority spin component for high-Mn content doping in GaP, as displayed in

Table 1. The HM gap decreases as the Mn-composition augments in the GaP compound. This situation is attributed to the localized character of Mn-d orbitals at

EF, which reduces with the augmentation of the doped composition from 0.03 to 0.75. The Mn-d orbitals are significantly hybridized with P-p orbitals for the various doping levels (

x = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75), arising in an energy gap for the spin-down state with the greater distribution between bonding (e

g) and antibonding (t

2g) orbitals. Significantly, the half-metallicity was determined to remain intact as the dopant concentration varies between 0.03 and 0.75.

A deep knowledge about optical spectroscopy is important to understand the underlying properties of materials. In this respect, the incorporation of not only the vacant and filled levels of the electronic structure, but also the band character, is required to attain the optical properties. The XAS constitutes a realistic experimental tool for analyzing the valence states of a particular element [

35,

36]. The relation of the XAS intensity (

I) of a peculiar atom (

A) in the dipole approach is denoted as follows:

where the photon frequency is indicated by

and

NAl represents the

l-like partially non-occupied DOS of atom

A. Notably,

A denotes Mn and

l is related to Mn-states. Here, the contribution of Mn 4p states is accompanied by the Mn K-edge spectra. This is mainly attributed to the angular momentum selection rule by means of the dipole approach. In the light of experimental techniques such as XAS and resonant X-ray scattering, we can procure a straightforward guideline of the occupied orbitals. Thus, the non-occupied DOS in the vicinity of the Mn K-edge grants a supplied elucidation regarding the incorporation of the orbitals into the chemical bonding. In order to acquire further comprehension by means of the Mn K-edge XAS spectra of Ga

1−xMn

xP ternary alloys, our calculations of XAS spectra are procured using the GGA + U approach. The valence state of Mn was investigated by means of XANES at the K-edge of Mn. Note that the XANES is sensitive to the valence state of the absorber. Accordingly, XAS has been performed with Mn-doped GaP material to identify the electronic environment of Mn

3+.

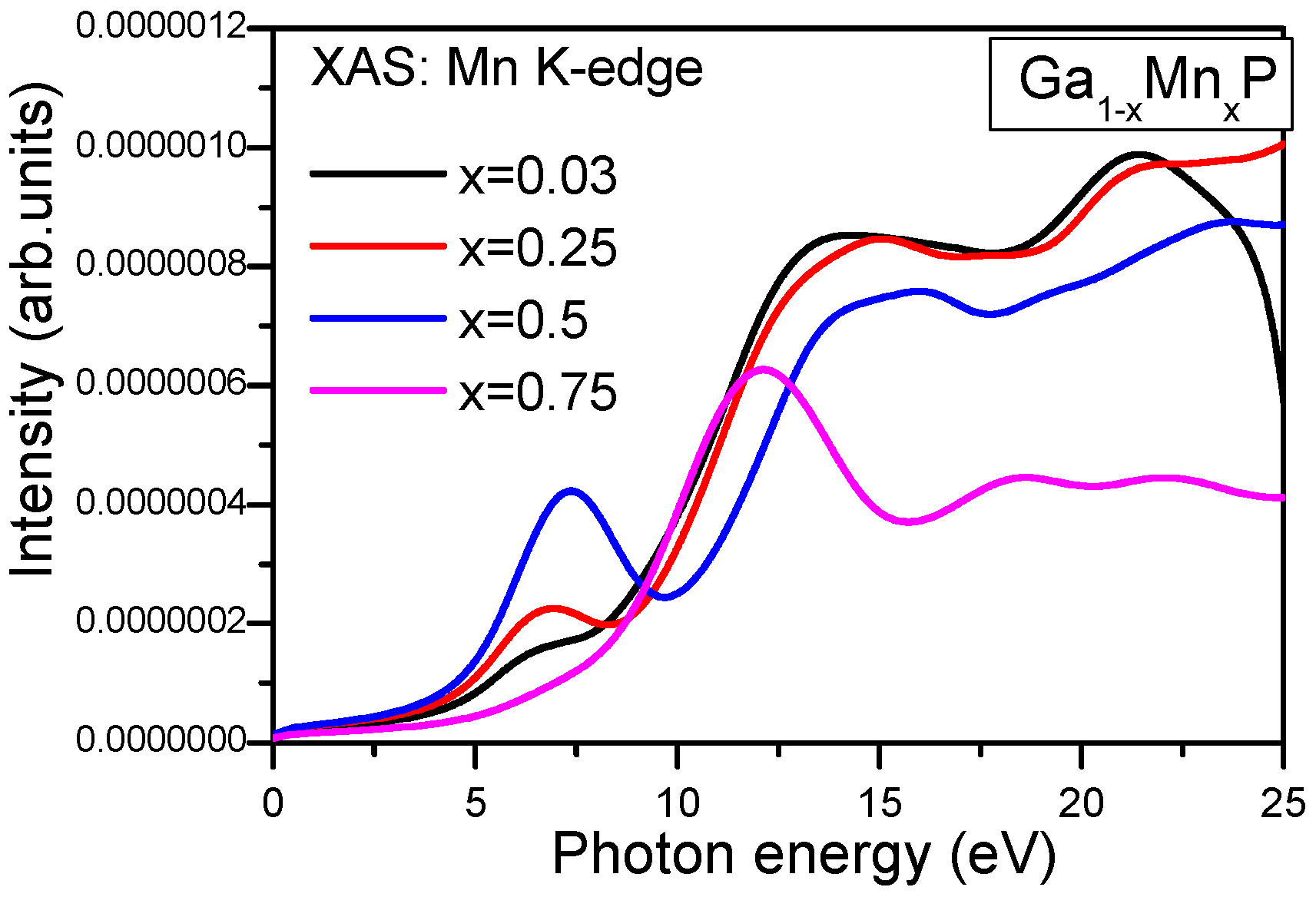

In

Figure 8, we illustrate the edge part of the Mn K-edge X-ray absorption spectra of Ga

1−xMn

xP (

x = 0.03, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75) alloys. At first glance, the plots display some similar features in the XANES spectra of Ga

0.75Mn

0.25P and Ga

0.5Mn

0.5P alloys, which implies a strong effect of p states (see

Figure 8). By considering the aforementioned results, assisted by the computed total and partial (i.e., referred to Mn 3d orbitals) DOS of Ga

1−xMn

xP systems, a qualitative similarity between the main peaks of Ga

0.75Mn

0.25P and Ga

0.50Mn

0.50P emerges, lying above the energy of the K-absorption threshold. According to the dipole selection rule, the allowed transition to bands contain only p states. For this reason, two well resolved pre-edge peaks are developed at 5.0 and 16 eV (see

Figure 8). The Mn K-edge X-ray spectra in Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys illustrate that the pre-edge structures are shifted upward in the energy to elevated photon energies and in intensity versus the change of

x concentration (

Figure 8). The calculated spectra describe a clear splitting in the first two peaks for low Mn-content in GaP materials compared to the relative intensities of XAS of the Ga

0.25Mn

0.75P alloy. The first small pre-peak is positioned at approximately 6.9 eV for

x = 0.03 and 0.25. It is therefore shifted and doubled in intensity for the Ga

0.5Mn

0.5P alloy located at approximately 7.3 eV. It is well noticeable that the pre-edge structure contains a marked single peak at approximately 12.6 eV for

x = 0.03 and 0.25 and is often characterized by weakly permitted dipole transitions from Mn(1s) to Mn(3d/4p) orbitals. Further, the alteration originating from the core hole effect would be dissimilar for the d-orbitals of the pre-edge doublet and the p-orbitals in the conduction states [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. However, the second peak is positioned near 18.6 eV, which is much weaker in the Ga

0.25Mn

0.75P alloy compared to the case of low Mn-content in GaP alloys and subsequently, the intensity of the absorption spectrum is decreased above 20 eV. Notably, the second peak of XAS for low content of Mn is more remarkable around 15.1 eV, which is increased in the intensity of absorption beyond 20 eV. As apparent, in the CB, the Mn -4p states are reflected by the absorption lines at an elevated energy. Otherwise, the second structural peak of the Mn K-edge spectra of the Ga

0.75Mn

0.25P and Ga

0.50Mn

0.50P systems illustrates a wide top spreading from 15 to 20 eV (

Figure 8). Nevertheless, its pattern proposes the presence of two components and partially overlapped peaks.

A remarkable feature about the increase of the intensity of the Mn K-edge spectrum is due to the augmentation of Mn content in GaP. The first pre-edge in XAS signifies that the 3d orbitals (majority-spin channel) are not thoroughly occupied. From the interpretation of XANES, the excited electrons arise from the vacant states upwards of

EF and are produced from the core states. The tetrahedral coordination of ligands (nearest neighbor P ions) enables p-d hybridized states of Mn. In other words, the major K-edge absorption begins and expands into various Mn elements over the section of highly delocalized 4p states. The assignment of p-d hybridized states is positioned at some specific peaks, and this is due to the population of d-electrons in the Mn sphere (4.49 e) and the resulting global magnetic moment (4.0 µ

B/cell) in all alloys. This population value of d-electrons points to the 3+ valence state of Mn (d

4 configuration). It is compelling to compare the current K-edge spectra, in which we infer that the 3+ valence states of Mn exhibit a tetrahedral arrangement of P ligands in the ZB-type lattice. Hence, the first pre-peak is present in the spectra with low dopants. Consequently, the pattern of the XANES spectrum is related to the variation of Mn concentration, implying the addition of more valence states of Mn atoms in the GaP system. It is inferred that a peak in the pre-edge structure corresponds to the 3+ valence state of Mn. Notably, this feature was also detected in GaMnAs systems [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], in accordance with the overall comprehension that Mn behaves as an acceptor in Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys, from which it possesses d

4 configuration.

In overall, the pre-edge structure for the Mn K-edge of these studied alloys contains one or two insignificant spectral peaks, which possess Mn-3d like orbitals. Notably, these striking characteristics are detected in XANES spectral features for various TM materials [

2,

35,

37,

38,

39]. With the modification of the Mn-content in the related alloys, a translation shifts and an additional structure is present. Exclusively, for all the studied alloys, the difference appears in the peak pre-edge structure, which is principally assigned to the Mn-3d/4p orbitals. Hence, the quantitative inspection of XANES is related to the alteration of the Mn K-edge threshold energy and the magnitude of pertinent cation–anion charge transfer in these alloys. It is proposed that the bonding and p-d exchange between Mn and P in these alloys are dramatically similar because the XAS line-shapes are predominantly influenced by the hybridization of the t

2g-symmetric Mn 3d states with the neighboring anion p states. The calculated spectra are consistent with the earlier measurements on GaMnAs alloys [

35]. From the previous experiments based on a detailed analysis of X-ray diffraction and X-ray linear dichroism, it was found that Mn atoms occupy Ga sites with a significant +3 valence state [

2,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. It is anticipated from our theoretical realizations that more investigations about the magnetic properties of Ga

1−xMn

xP alloys will be proposed. From the calculations of the XAS spectra, the Mn-dopant in the GaP compound provides a realistic mapping for interpreting the electronic structure and magnetic features of Ga

1−xMn

xP systems.