Energy Efficiency and International Regulation of Single-Phase Induction Motors: Evidence from Tests in the Brazilian Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

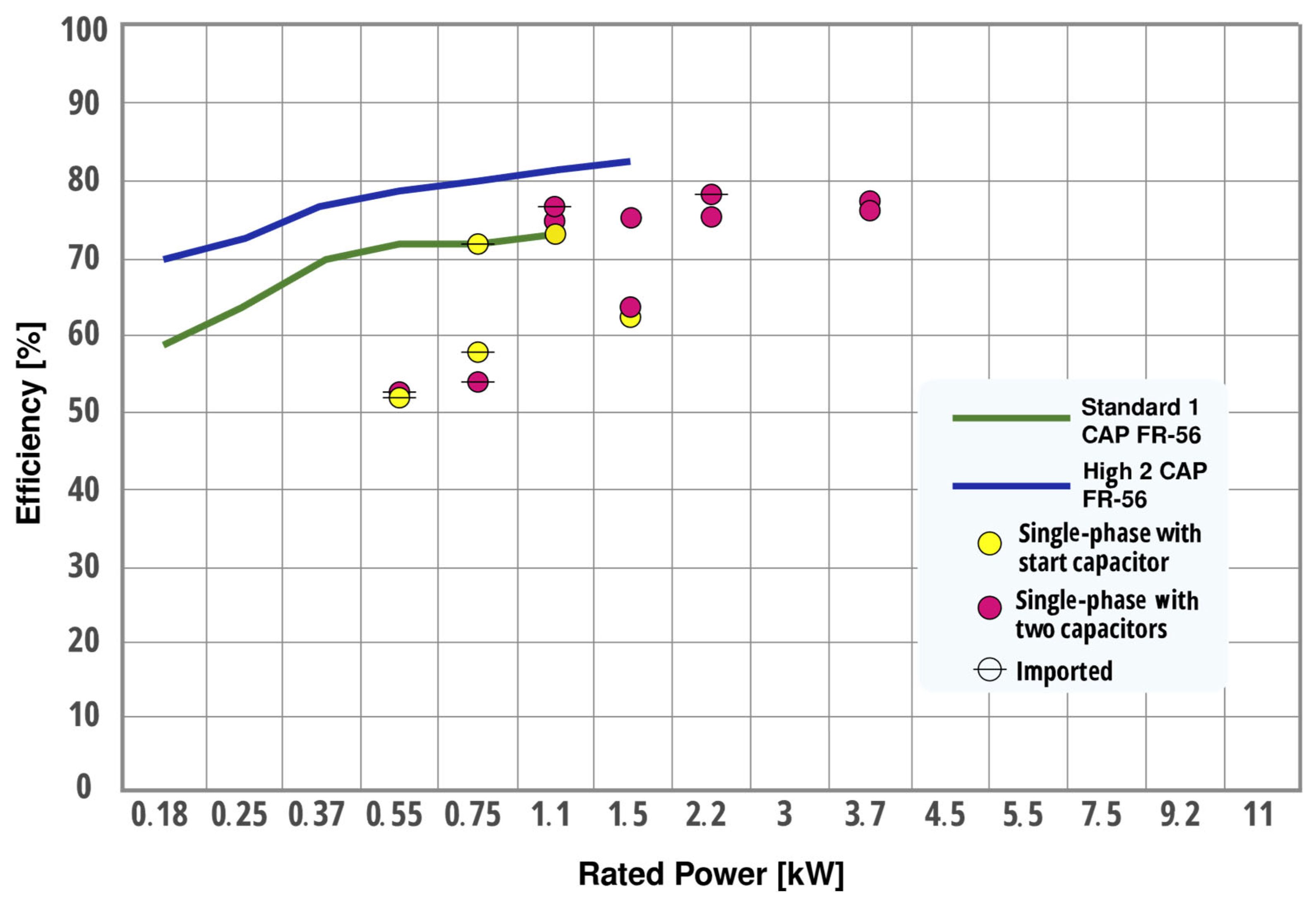

- What are the main types of single-phase induction motors for general use, and what are their technical characteristics and applications?

- Which countries already regulate the commercialization of single-phase motors under MEPS frameworks, and what are the main features and requirements of these regulations?

- What is the actual efficiency of single-phase motors available in the Brazilian market, and how does it compare with MEPS benchmarks?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Laboratory Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Types of Single-Phase Induction Motors for General Use

3.1.1. Split-Phase (SP) Motor

3.1.2. Capacitor-Start Induction-Run (CSIR) Motor

3.1.3. Permanent-Split-Capacitor (PSC) Motor

3.1.4. Capacitor-Start, Capacitor-Run (CSCR) Motor

3.2. Review of International Energy Efficiency Policies for Single-Phase Motors

3.2.1. European Union (Including Switzerland, Turkey, Norway, and Great Britain)

- The annual sales volume of the product, according to Regulation (EU) 2019/1781, must reach at least 200,000 units per year;

- The product must also demonstrate significant energy consumption during the use phase. In addition, the regulation specifies that authorities should not implement it if it substantially increases the product’s cost;

- Many motors are integrated into other products. To maximize energy savings in a cost-effective manner, the regulation also applies to these motors, provided that their efficiency can be independently tested. It specifies that motors integrated into products (e.g., within a gearbox, pump, fan, or compressor) whose energy performance cannot be measured independently of the product, as well as motors with integrated variable speed drives whose performance cannot be assessed separately from the drive, are not covered by the regulation;

- Also excluded are motors intended to operate under adverse conditions, such as unusual temperature ranges (ambient temperatures above 60 °C, below 0 °C, or above 32 °C for water-cooled motors, or below −30 °C for any motor), abnormal pressure conditions (altitudes above 4000 m) or in classified or hazardous locations (for example, explosion-protected areas, radioactive environments or submerged applications). The regulation also excludes motors with integrated batteries, handheld units, motors mounted in equipment that moves them during use, motors with mechanical commutators, units intended for e-mobility, and non-ventilated motors.

3.2.2. United States of America

- Technical aspects, such as recommendations regarding materials and design improvements to enhance motor efficiency;

- Identification of manufacturers already offering motors that met the desired efficiency levels, thereby demonstrating the technical feasibility of achieving the required performance;

- Production and product cost analysis associated with MEPS implementation;

- Economic assessment for consumers, including Net Present Value (NPV) and Payback Period simulations based on the U.S. context;

- Energy and environmental benefits resulting from the adoption of the regulation.

3.2.3. China

3.2.4. Ecuador

3.2.5. Argentina

3.2.6. Ghana

3.2.7. Timeline Summary

3.2.8. General Aspects of International Regulations for Single-Phase Motors

3.3. Actual Efficiency of Single-Phase Motors Available on the Brazilian Market

3.4. Summary of Single-Phase Motor Performance in the Brazilian Market

4. Conclusions

- Expansion of the experimental sample, encompassing motors with a wider range of rated powers, voltages, and specific applications (residential, commercial, and agro-industrial), to provide a more comprehensive characterization of the Brazilian market;

- Assessment under real operating conditions, through in-field efficiency measurements in residential, commercial, and rural installations, in order to verify the consistency between laboratory results and actual in-use performance;

- Incorporation of partial-load testing, complementing rated-load efficiency measurements to better reflect typical duty cycles of single-phase motors;

- Evaluation of regulatory and long-term scenarios, analyzing the potential impacts of mandatory adoption of IE1 and IE2 efficiency levels in Brazil and projecting long-term energy consumption and emission trajectories over 20–30 years;

- Comparative life cycle assessment (LCA), examining not only the environmental performance of single-phase motors, but also alternative solutions such as three-phase motors supplied by single-phase grids through frequency converters in regions without access to three-phase distribution networks;

- Integration with emerging technologies, including power electronics, variable-speed drives, and digital solutions (sensors, IoT, and predictive monitoring), aiming at additional gains in efficiency, reliability, and durability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABNT | Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas |

| BLDC | Brushless DC Motor |

| DOE | U.S. Department of Energy |

| EPCA | Energy Policy and Conservation Act |

| GB | Guobiao (Chinese National Standard prefix) |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IEC | International Electrotechnical Commission |

| ILAC | International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation |

| IR | Índice de Rendimento (Brazilian Efficiency Index) |

| IE | International Efficiency (IE classes) |

| MEPS | Minimum Energy Performance Standards |

| NEMA | National Electrical Manufacturers Association |

| ODP | Open-Drip-Proof (motor enclosure type) |

| PNEf | Plano Nacional de Eficiência Energética |

| PSC | Permanent-Split Capacitor Motor |

| SCIM | Squirrel-Cage Induction Motor |

| SP | Split-phase motor |

| CSIR | Capacitor-Start Induction-Run motor |

| PSC | Permanent-Split-Capacitor motor |

| CSCR | Capacitor-Start, Capacitor-Run motor |

| TEFC | Totally Enclosed Fan-Cooled (motor enclosure type) |

Appendix A

| Equipment | Manufacturer, Country | Model | Measure | Accuracy (at 25 °C and 40–65% Humidity) | Calibration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy analyzer | Yokogawa Electrical Company, Musashino, Tokyo, Japan | WT1800 | voltage; current; active power; power factor; voltage frequency; speed (pulse generated through an inductive sensor with a metal disc with teeth attached to the dynamometer axle) | Voltage, current, and power: 0.05% reading and 0.05% range Hz (30–66): 0.01% reading +0.03% range Hz (1–10 kHz): 0.1% reading +0.05% range | every two years |

| Load cell | Alfa Instrumentos, São Paulo, SP, Brazil | 3107D | weight; torque | 0.01% | every year |

| Mercury thermometer | Incoterm, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil | - | room temperature | 0.1 °C/division | every two year |

| Thermocouple transducer | Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA, USA | 80TK | motor temperature | ±2 °C + ±0.5% reading | every year |

| Milivoltmeter (digital multimeter) | Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA, USA | 8846A | motor temperature | ± (0.25% reading + 0.3% range) | every two year |

References

- Empresa de Pesquisa Energética. Balanço Energético Nacional 2025; Relatório Final/Ano Base 2024; S.n.: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/PublicacoesArquivos/publicacao-885/topico-771/Relat%C3%B3rio%20Final_BEN%202025.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Renewables 2024—Analysis and Forecast to 2030; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/17033b62-07a5-4144-8dd0-651cdb6caa24/Renewables2024.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. The Role of CCUS in Low-Carbon Power Systems; IEA: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ccdcb6b3-f6dd-4f9a-98c3-8366f4671427/The_role_of_CCUS_in_low-carbon_power_systems.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/5b169aa1-bc88-4c96-b828-aaa50406ba80/GlobalEnergyReview2025.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Ministério de Minas E Energia. Plano Nacional de Energia PNE 2050; MME: Brasília, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/secretarias/sntep/publicacoes/plano-nacional-de-energia/plano-nacional-de-energia-2050/relatorio-final/relatorio-final/relatorio-final-do-pne-2050.pdf/@@download/file (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Procel: Procel 20 Anos. Rio de Janeiro. Eletrobras. 2006. Available online: https://catalogo.ipea.gov.br/uploads/170_1.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Geller, H.; Harrington, P.; Rosenfeld, A.H.; Tanishima, S.; Unander, F. Polices for increasing energy efficiency: Thirty years of experience in OECD countries. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, R. Energy-Efficiency Solutions: What Commodity Prices Can’t Deliver. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/118637 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- BRASIL. Lei n° 10.295. Presidência da República Casa Civil. De 17 de Outubro de 2001. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10295.htm (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Nogueira, L.A.H.; Cardoso, R.B.; Cavalcanti, C.Z.B.; Leonelli, P.A. Evaluation of the energy impacts of the Energy Efficiency Law in Brazil. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2014, 24, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério de Minas e Energia. Plano Nacional de Eficiência Energética Premissas e Diretrizes Básicas; MME: Brasília, Brazil, 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/secretarias/sntep/publicacoes/plano-nacional-de-eficiencia-energetica/documentos/plano-nacional-eficiencia-energetica-pdf.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Waide, P.; Brunner, C.U.; International Energy Agency. Energy-Efficiency Policy Opportunities for Electric Motor-Driven Systems. 2011. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/d69b2a76-feb9-4a74-a921-2490a8fefcdf/EE_for_ElectricSystems.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Saidur, R. A review on electrical motors energy use and energy savings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 14, 877–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A.T.; Fong, J.A.C.; Ferreira, F.J.T.E. Energy-Efficient Industrial Motor-Driven Systems and Standards Toward Net Zero Carbon. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/IAS 60th Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Technical Conference (I&CPS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19–23 May 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEMA MG1; Motors and Generators. NEMA—National Electrical Manufacturers Association: Rosslyn, VA, USA, 2021.

- IEC 60034-30-1; Rotating Electrical Machines—Part 30-1 Efficiency Classes of Line Operated AC Motors (IE Code). International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ABNT NBR 17094-2; Máquinas Elétricas Rotativas—Motores de Indução Monofásicos—Parte 2: Métodos de Ensaio de Desempenho. Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022.

- International Energy Agency. Minimum Energy Performance Standards for Motor Systems: Global Overview, IEA-4E EMSA. Available online: https://www.iea-4e.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/emsa-meps-export-v6-1.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Lu, S.-M. A review of high-efficiency motors: Specification, policy, and technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, D.F.; Salotti, F.A.M.; Sauer, I.L.; Tatizawa, H.; De Almeida, A.T.; Kanashiro, A.G. A Performance Evaluation of Three-Phase Induction Electric Motors between 1945 and 2020. Energies 2022, 15, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, D.F.; Salotti, F.A.M.; Sauer, I.L.; Tatizawa, H.; De Almeida, A.T.; Kanashiro, A.G. An assessment of the impact of Brazilian energy efficiency policies for electric motors. Energy Nexus 2021, 5, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60034-2-1; Rotating Electrical Machines—Part 2-1: Standard Methods for Determining Losses and Efficiency from Tests (Excluding Machines for Traction Vehicles). International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Oliveira Junior, A.G. Single-Phase Induction Motors and the Challenge of Energy Efficiency in Brazil: A Critical and Proposed Analysis. Master’s Dissertation, Institute of Energy and Environment, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2025. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, G.; Ciancetta, F.; Fiorucci, E.; Ometto, A. Uncertainty issues in direct and indirect efficiency determination for Three-Phase induction motors: Remarks about the IEC 60034-2-1 standard. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2016, 65, 2701–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.J. Electric Machinery Fundamentals; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, P.S.; Dorrell, D.G.; Weihrauch, N.C.; Hansen, P.E. Synchronous torques in Split-Phase induction motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2009, 46, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldea, I.; Nasar, S.A. The Induction Machines Design Handbook, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Umans, S.; Fitzgerald, A.; Kingsley, C. Electric Machinery: Seventh Edition; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2019/1781 of 1 October 2019 Establishing the Eco-Design Requirements for Electric Motors and Variable Speed Drives Pursuant to Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L 272, 75–93. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019R1781 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- European Parliament & Council. Directive 2009/125/EC of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for the Setting of Ecodesign Requirements for Energy-Related Products (Recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, L 285. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02009L0125-20121204 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- De Almeida, A.T.; Fong, J.; Falkner, H.; Bertoldi, P. Policy options to promote energy efficient electric motors and drives in the EU. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congress of the United States. Energy Policy and Conservation Act. Public Law 94-163, 94th Congress, 22 December 1975. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-89/pdf/STATUTE-89-Pg871.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Energy Conservation Program: Energy Conservation Standards for Small Electric Motors, 75 Fed. Reg. 10,874 (9 March 2010). Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2010/03/09/2010-4358/energy-conservation-program-energy-conservation-standards-for-small-electric-motors (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Energy Conservation Program: Energy Conservation Standards for Electric Motors, 88 Fed. Reg. 36066 (1 June 2023). Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/06/01/2023-10019/energy-conservation-program-energy-conservation-standards-for-electric-motors (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- GB 25958; Minimum Allowable Values of Energy Efficiency and Values of Efficiency Grade for Small-Power Motors, Guobiao Standard. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- GB 18613; Minimum Allowable Values of Energy Efficiency and Values of Efficiency Grades for Motors, Guobiao Standard. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Zeng, L.; Bo, H. Potential for Further Improvement of China’s Electric Motor Energy Efficiency Standards and Its Impact on Carbon Emissions Reductions. In Proceedings of the Energy Efficiency in Motor Driven Systems (EEMODS’24), Luzern, Switzerland, 3–5 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Industrias y Productividad. Servicio ecuatoriano de normalización. Resolución n° 17.524. Diciembre, 2017. Available online: https://www.normalizacion.gob.ec/buzon/reglamentos/RTE-145.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- NTE INEN 2 498; Eficiencia Energética en Motores Eléctricos Estacionarios—Requisitos. Instituto Ecuatoriano de Normalización: Quito, Ecuador, 2009.

- Ministerio de Justicia de La Nación. Disposición 230/2015; Ministerio de Justicia de La Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina. Available online: https://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/250000-254999/251749/norma.htm (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- IRAM 62409; Etiquetado de Eficiencia Energética para Motores de Inducción Monofásicos. Instituto Argentino de Normalización y Certificación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014.

- WEG. Regulamentações Globais de Eficiência para Motores Elétricos de Baixa Tensão. Jaraguá do Sul-SC: Rev 13, julho de 2022. Available online: https://static.weg.net/medias/downloadcenter/h04/h8f/WEG-WMO-regulamentacoes-globais-de-eficiencia-para-motores-eletricos-50065222-brochure-portuguese.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Energy Commission. Energy Efficiency Standards and Labeling (Electric Motors), Regulations 2022. L.I 2456. Gana, 2022. Available online: https://www.energycom.gov.gh/index.php/regulation/energy-efficiency-ie?download=229:energy-commission-energy-efficiency-standards-and-labelling-electric-motors-regulations-2022-li-2456 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Damian, P.; Durand, A.; Fong, J. Opportunities for minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) for electric motors in Ghana. In Proceedings of the European Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ECEEE Summer Study) 2022, Hyères, France, 6–11 June 2022; Available online: https://publica.fraunhofer.de/bitstreams/c7688741-f0cc-4ac6-9054-d4c306cea0dc/download (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- ABNT NBR 17094-1; Máquinas Elétricas Girantes—Parte 1: Motores de Indução Trifásicos—Requisitos. Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018.

| Efficiency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated Power (kW) | 2 Poles | 4 Poles | 6 Poles | 8 Poles |

| 0.12 | 53.6 | 59.1 | 50.6 | 39.8 |

| 0.18 | 60.4 | 64.7 | 56.6 | 45.9 |

| 0.20 | 61.9 | 65.9 | 58.2 | 47.4 |

| 0.25 | 64.8 | 68.5 | 61.6 | 50.6 |

| 0.37 | 69.5 | 72.7 | 67.6 | 56.1 |

| 0.40 | 70.4 | 73.5 | 68.8 | 57.2 |

| 0.55 | 74.1 | 77.1 | 73.1 | 61.7 |

| 0.75 | 77.4 | 79.6 | 75.9 | 66.2 |

| 1.10 | 79.6 | 81.4 | 78.1 | 70.8 |

| 1.50 | 81.3 | 82.8 | 79.8 | 74.1 |

| 2.20 | 83.2 | 84.3 | 81.8 | 77.6 |

| 3.00 | 84.6 | 85.5 | 83.3 | 80.0 |

| 4.00 | 85.8 | 86.6 | 84.6 | 81.9 |

| 5.50 | 87.0 | 87.7 | 86.0 | 83.8 |

| 7.50 | 88.1 | 88.7 | 87.2 | 85.3 |

| 9.20 | 89.4 | 89.8 | 88.7 | 86.9 |

| 11.00 | 90.3 | 90.6 | 89.7 | 88.0 |

| Efficiency (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated Power (HP) | Frame | Open Frame (8 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (2 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (4 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (6 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (8 Poles) |

| 0.25 | 48 | - | 59.5 | 59.5 | 57.5 | - |

| 0.25 | 56 | - | 59.5 | 59.5 | 57.5 | - |

| 0.33 | 48 | - | 64.0 | 64.0 | - | - |

| 0.33 | 56 | 50.5 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 62.0 | 50.5 |

| 0.50 | 48 | - | 68.0 | 66.0 | - | - |

| 0.50 | 56 | 52.5 | 70.0 | 70.0 | 68.0 | 52.5 |

| 0.75 | 48 | - | 70.0 | 70.0 | - | - |

| 0.75 | 56 | - | 72.0 | 72.0 | 70.0 | - |

| 1.00 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1.00 | 56 | - | 72.0 | 72.0 | 72.0 | - |

| 1.50 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1.50 | 56 | - | 74.0 | 74.0 | - | - |

| 2.00 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2.00 | 56 | - | 77.0 | - | - | - |

| 3.00 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Efficiency (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated Power (HP) | Frame | Open Frame (8 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (2 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (4 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (6 Poles) | Enclosed Frame (8 Poles) |

| 0.25 | 48 | 55.0 | 68.0 | 70.0 | 64.0 | 55.0 |

| 0.25 | 56 | 55.0 | 68.0 | 70.0 | 64.0 | 55.0 |

| 0.33 | 48 | 57.5 | 72.0 | 72.0 | 68.0 | 57.5 |

| 0.33 | 56 | 59.5 | 72.0 | 74.0 | 68.0 | 59.5 |

| 0.50 | 48 | 62.0 | 72.0 | 74.0 | 72.0 | 62.0 |

| 0.50 | 56 | 64.0 | 74.0 | 77.0 | 72.0 | 64.0 |

| 0.75 | 48 | - | 75.5 | 75.5 | - | - |

| 0.75 | 56 | 72.0 | 77.0 | 78.5 | 75.5 | 72.0 |

| 1.00 | 48 | - | 77.0 | - | - | - |

| 1.00 | 56 | 74.0 | 78.5 | 80.0 | 77.0 | 74.0 |

| 1.50 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1.50 | 56 | - | 81.5 | 81.5 | 80.0 | - |

| 2.00 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2.00 | 56 | - | 82.5 | 82.5 | - | - |

| Efficiency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Type | Rated Power Range (kW) | Efficiency Grade 1 (%) | Efficiency Grade 2 (%) | Efficiency Grade 3 (%) |

| Capacitor-start single-phase induction motor | 120 W–3.7 kW | 58.1–81.4 | 54.1–78.8 | 50.0–76.0 |

| Capacitor-run single-phase induction motor | 120 W–2.2 kW | 67.5–85.9 | 63.8–83.2 | 60.0–79.7 |

| Dual-value capacitor single-phase induction motor (CSCR) | 250 W–3.7 kW | 73.5–87.8 | 68.5–86.3 | 62.0–82.6 |

| Facts That Exclude Single-Phase Motors from a Regulation Using MEPS | Facts to Be Considered When Adopting a Regulation Using MEPS for Single-Phase Motors |

|---|---|

| It should be integrated into a product in a way that allows it to be tested only as part of the overall system. | Significant sales volume. |

| Having special accessories as an integrated part (variable speed drives, electronic circuits that alter motor operation, brakes, batteries, liquid heat-exchange circuits, etc.). | Significant energy savings during the use phase, provided that the manufacturing phase does not imply high economic and environmental costs. |

| Have special applications (such as extreme high or low temperatures, high altitudes, explosive, corrosive, radioactive, submerged, or humid environments, etc.). | Economic feasibility for the customer. |

| Have a duty cycle other than continuous S1. | Some countries require only MEPS IE2, which tends to result in only motors with two capacitors being available, typically in countries using a 50 Hz power supply. Other countries require IE2 (motor with two capacitors) and also IE1 for less efficient motors (split-phase and starting-capacitor motors), generally in countries using 60 Hz. |

| Single-phase shaded-pole motor. |

| Type | Regulating Country | MEPS | Power (kW) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP * | China | IE1 | 0.12–0.75 | fans, grinders, dishwashers |

| CSIR | USA, China, others | IE1 | 0.18–2.2 | washing machines, compressors, pumps |

| PSC | China | IE1.5 | 0.37–1.5 | compressors |

| CSCR | USA, China, others | IE2 | >0.75 | pumps, compressors |

| Percent Above IR1 | Max Positive Deviation IR1 | Max Negative Deviation IR1 | Mean Absolute Deviation IR1 | Standard Deviation IR1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48.5% | 12.0% | 14.6% | 5.59% | 6.14% |

| Percent Above IR2 | Max Positive Deviation IR2 | Max Negative Deviation IR2 | Mean Absolute Deviation IR2 | Standard Deviation IR2 |

| 3.0% | 2.5% | 20.8% | 10.9% | 12.0% |

| Percent Above Standard/IE1 | Max Positive Deviation Standard/IE1 | Max Negative Deviation Standard/IE1 | Mean Absolute Deviation Standard/IE1 | Standard Deviation Standard/IE1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30.4% | 6.4% | 17.3% | 6.83% | 7.34% |

| Percent ABOVE High/IE2 | Max Positive Deviation High/IE2 | Max Negative Deviation High/IE2 | Mean Absolute Deviation High/IE2 | Standard deviation High/IE2 |

| 0% | - | 18.6% | 9.7% | 11.2% |

| Percent Above IR1 | Max Positive Deviation IR1 | Max Negative Deviation IR1 | Mean Absolute Deviation IR1 | Standard Deviation IR1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46.7% | 6.8% | 12.3% | 6.10% | 6.26% |

| Percent Above IR2 | Max Positive Deviation IR2 | Max Negative Deviation IR2 | Mean Absolute Deviation IR2 | Standard Deviation IR2 |

| 0% | - | 24.7% | 14.1% | 14.68% |

| Percent Above Standard/IE1 | Max Positive Deviation Standard/IE1 | Max Negative Deviation Standard/IE1 | Mean Absolute Deviation Standard/IE1 | Standard Deviation Standard/IE1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% | 1.1% | 21.2% | 7.04% | 10.2% |

| Percent Above High/IE2 | Max Positive Deviation High/IE2 | Max Negative Deviation High/IE2 | Mean Absolute Deviation High/IE2 | Standard Deviation High/IE2 |

| 0% | - | 27.7% | 13.6% | 17.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oliveira Junior, A.G.; Bassi, W.; Salotti, F.A.M.; Tatizawa, H.; Neto, A.Q.d.S.; de Souza, D.F. Energy Efficiency and International Regulation of Single-Phase Induction Motors: Evidence from Tests in the Brazilian Market. Energies 2026, 19, 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030712

Oliveira Junior AG, Bassi W, Salotti FAM, Tatizawa H, Neto AQdS, de Souza DF. Energy Efficiency and International Regulation of Single-Phase Induction Motors: Evidence from Tests in the Brazilian Market. Energies. 2026; 19(3):712. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030712

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira Junior, Abrão Garcia, Welson Bassi, Francisco Antônio Marino Salotti, Hédio Tatizawa, Antônio Quirino da Silva Neto, and Danilo Ferreira de Souza. 2026. "Energy Efficiency and International Regulation of Single-Phase Induction Motors: Evidence from Tests in the Brazilian Market" Energies 19, no. 3: 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030712

APA StyleOliveira Junior, A. G., Bassi, W., Salotti, F. A. M., Tatizawa, H., Neto, A. Q. d. S., & de Souza, D. F. (2026). Energy Efficiency and International Regulation of Single-Phase Induction Motors: Evidence from Tests in the Brazilian Market. Energies, 19(3), 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19030712