1. Introduction

Traditional power generation architectures, historically dominated by synchronous generators, are undergoing fundamental transformation as renewable energy systems proliferate globally. The integration of photovoltaic arrays, wind turbines, fuel cells, and battery energy storage systems (BESS) into electrical grids has catalyzed a paradigm shift in power system operation and control [

1,

2,

3]. These renewable technologies interface with the grid through power electronic converters, forming what is collectively termed inverter-based resources (IBRs). The progressive displacement of rotating synchronous machines by converter-interfaced generation fundamentally alters the mechanisms through which essential grid services are provided [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Critical functions, including system inertia, frequency stability, and voltage regulation, which were once inherently embedded in the electromechanical characteristics of synchronous generators, must now be deliberately synthesized through advanced control strategies as conventional generation assets are gradually retired from service [

10].

The conventional control paradigm for grid-connected inverters has been the grid-following (GFL) approach. In this mode, inverters function as current sources that depend on phase-locked loop mechanisms to track externally provided voltage waveforms for synchronization and power injection. While this strategy demonstrates reliable performance in strong grid environments with well-established voltage references, it has a critical vulnerability: an absolute dependence on stable grid voltage and frequency signals. This fundamental limitation manifests during several operationally significant scenarios. When grid blackouts occur, when microgrids intentionally island from the main grid, or when weak grid conditions compromise reference signal quality, GFL inverters lose their ability to maintain stable operation due to the absence or degradation of the external references they require for synchronization [

4].

Grid-forming (GFM) control has emerged as the principal solution to address these inherent limitations of grid-following operation. The defining characteristic of GFM inverters is their capability to operate as autonomous voltage sources, independently establishing and regulating voltage magnitude and frequency without external synchronization signals [

4,

11]. This self-sustained operational mode enables several critical functionalities, including autonomous operation during islanded conditions, seamless transitions between grid-connected and islanded modes, and the provision of synchronization references for other distributed energy resources within the network [

4,

11,

12]. As power systems evolve toward configurations with diminished conventional generation and increased IBR penetration, the grid-forming capability becomes increasingly essential, rather than merely advantageous [

1,

10,

13]. Within these low-inertia environments, GFM inverters must deliver frequency stabilization during disturbances, maintain voltage regulation under varying load conditions, and ensure overall system resilience—functions that replicate the ancillary services traditionally provided by synchronous generators [

1,

13]. The adoption of grid-forming control thus represents not an incremental improvement but a foundational architectural evolution necessary to ensure the reliability and operational flexibility of future power systems.

Multiple control strategies have been developed and investigated to enable grid-forming functionality, each approach embodying distinct design philosophies and presenting unique performance characteristics. These strategies encompass droop control, Virtual Synchronous Generator (VSG) control, and virtual oscillator control (VOC), forming a diverse landscape of techniques with varying levels of complexity and operational trade-offs. Droop control remains the most established grid-forming strategy, favored for its simplicity and decentralized scalability, as it emulates the steady-state characteristics of synchronous generators through proportional power-frequency and reactive power-voltage relationships [

14,

15,

16]. However, its reliance on steady-state phasor approximations and low-pass filtering limits its dynamic performance, often resulting in sluggish transient response and a lack of inertial support during disturbances. In contrast, VSG control addresses these deficiencies by explicitly embedding the dynamic swing equation and virtual inertia into the control structure. By emulating the kinetic energy exchange of rotating machinery, VSG provides superior frequency stability and transient responsiveness, particularly in low-inertia environments. While high-order VSG models offer detailed fidelity at the cost of computational burden, low-order formulations provide a practical balance, delivering essential inertial support suitable for real-time embedded implementation [

2,

17,

18,

19].

Alternatively, VOC departs from machine emulation by operating entirely in the time domain, leveraging coupled nonlinear oscillators to achieve rapid, communication-free synchronization without the delays associated with phasor transformations [

20,

21,

22]. Although standard VOC offers fast dynamic response, it historically lacked programmable power dispatchability and inherent inertial support, potentially compromising waveform quality under unbalanced conditions. To overcome these limitations, Dispatchable Virtual Oscillator Control (dVOC) was developed, embedding active and reactive power setpoints directly into the oscillator dynamics. This variant retains the robust, global synchronization properties of classical VOC while enabling the precise power control required for modern microgrids, making it a compelling alternative for applications prioritizing speed over inertial emulation [

23,

24].

While Grid-Forming (GFM) strategies effectively secure physical stability, the evolution of modern microgrids into Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) introduces a critical dual dependency on both power and information flow. A dedicated communication layer is now essential for facilitating real-time coordination and data exchange among distributed units, enabling collective responses to load variations and enhancing operational flexibility [

25]. However, this integration exposes the system to severe cyber vulnerabilities, as the control layer is no longer isolated from external threats. Disruptions such as data corruption, packet delays, False Data Injection (FDI), and Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks can propagate directly through control loops, fundamentally altering the physical response of inverter-based resources [

26,

27,

28]. Even minor distortions in communicated measurements or setpoints can trigger unstable dynamics, incorrect load sharing, or degraded voltage profiles. Consequently, ensuring the integrity of this information flows is as critical as maintaining electromechanical stability, necessitating research frameworks that jointly emulate both the physical power system and the cyber infrastructure to assess how communication anomalies influence operational resilience rigorously [

29].

Recent research has increasingly focused on examining how cyber–physical threats compromise the stability and control of power systems and microgrids. In [

30], the vulnerability of load frequency control in a hybrid power system was analyzed under different FDI scenarios. The study demonstrated that manipulating control signals can significantly degrade frequency regulation and increase sensitivity to disturbances. However, the investigation relied solely on software-based simulation, providing no hardware or real-time validation to assess the persistence of attacks or controller behavior under practical constraints. A co-simulation approach integrating a cyber-physical system was introduced in [

31] to study delayed data manipulation on supervisory control and SCADA monitoring. Although the work highlighted the importance of network delay and demonstrated cyber–physical interactions, the implementation was restricted to software-in-the-loop, and thus lacked real controller execution dynamics.

In [

32], a real-time testbed utilizing an RTDS platform and HIL configuration was developed to investigate how denial-of-service (DoS) attacks affect system recovery following faults. Results confirmed that network congestion and communication delays can hinder system recovery after faults. Nonetheless, the study did not investigate cyberattacks that directly compromise control references or measurement integrity. Experimental validation of FDI threats using OPAL-RT-based HIL was presented in [

33]. The platform demonstrated how falsified measurements can disrupt voltage stability and power sharing in laboratory microgrids. While providing valuable practical insights, the work focused on a single microgrid architecture. The co-simulation framework in [

34] utilized RTDS and Mininet to evaluate communication effects in DC microgrid clusters under cyber threats. A testbed employing Typhoon HIL in [

35] assessed FDI and replay attacks on DC microgrids, confirming their impacts on current sharing and voltage stability. However, the experimental scope remained limited to the behavior of single microgrids without coordinated operation.

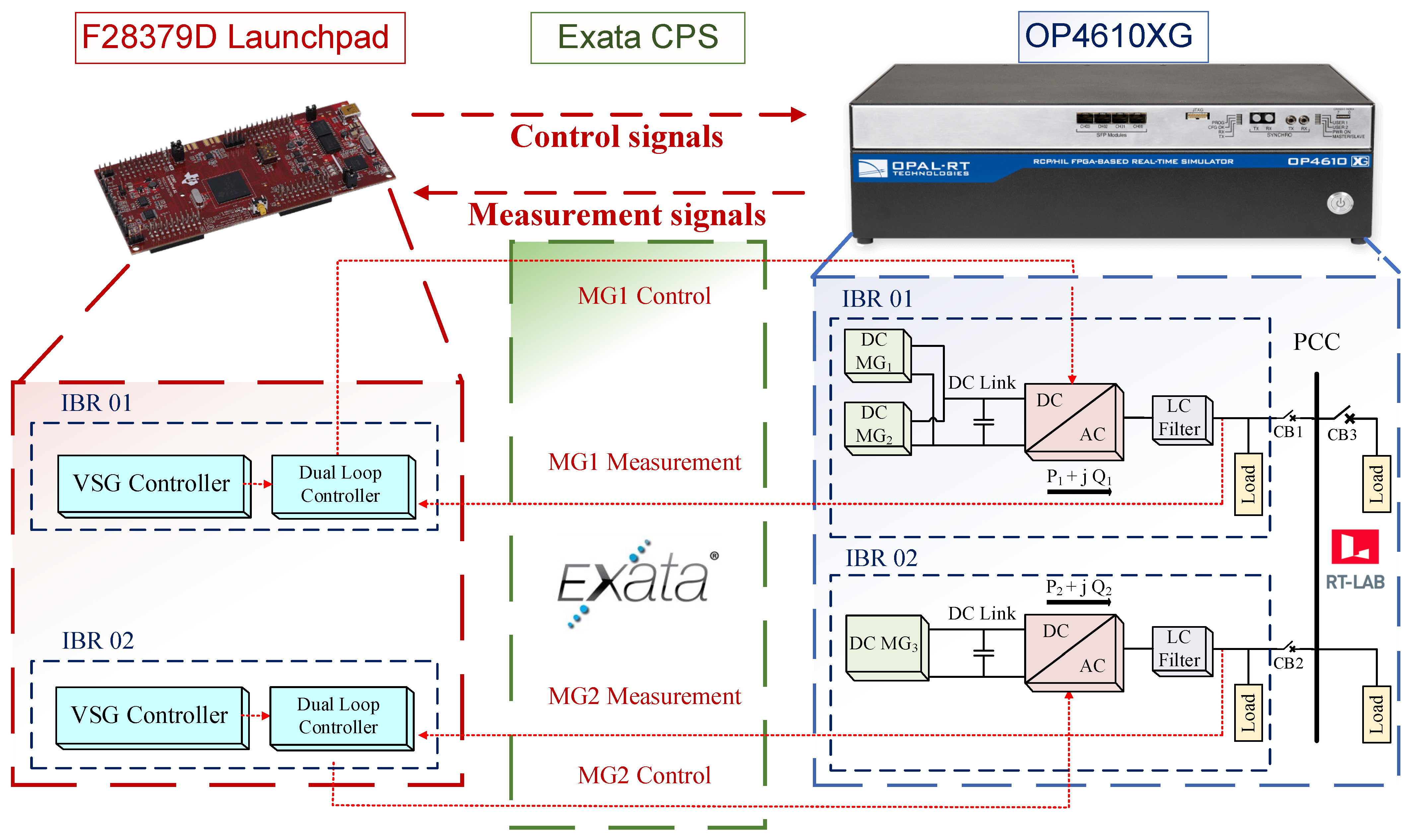

To address these challenges, this study presents a comprehensive Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop (CHIL) assessment of three distinct grid-forming control strategies: conventional Droop control, VSG control, and dVOC. Unlike previous studies that examine GFM performance or cyber-attacks in isolation, this work bridges the gap by providing a comprehensive HIL comparison of how different GFM topologies inherently react to coordinated cyber-physical threats. The study evaluates the operational resilience of these strategies under islanded, parallel, and fault-induced reconfiguration scenarios. Furthermore, recognizing the vulnerability of modern microgrids to cyber threats, this work integrates a high-fidelity network emulator (EXata CPS) to investigate the cyber-physical resilience of the VSG control strategy. Specifically, we validate a proposed resilience layer capable of detecting and mitigating FDI attacks on control references and feedback measurements.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details the microgrid configuration and the mathematical formulation of the three grid-forming control strategies.

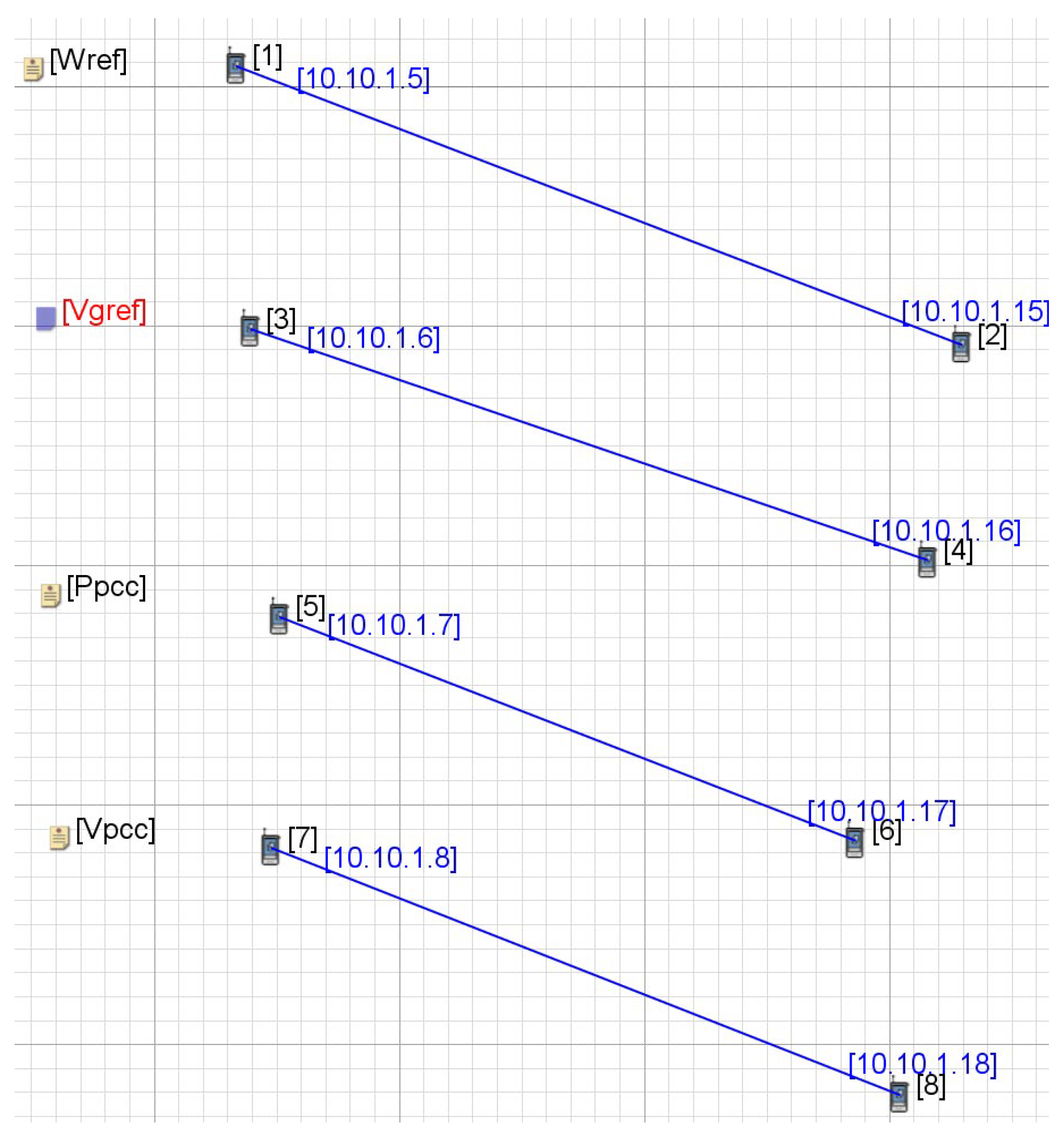

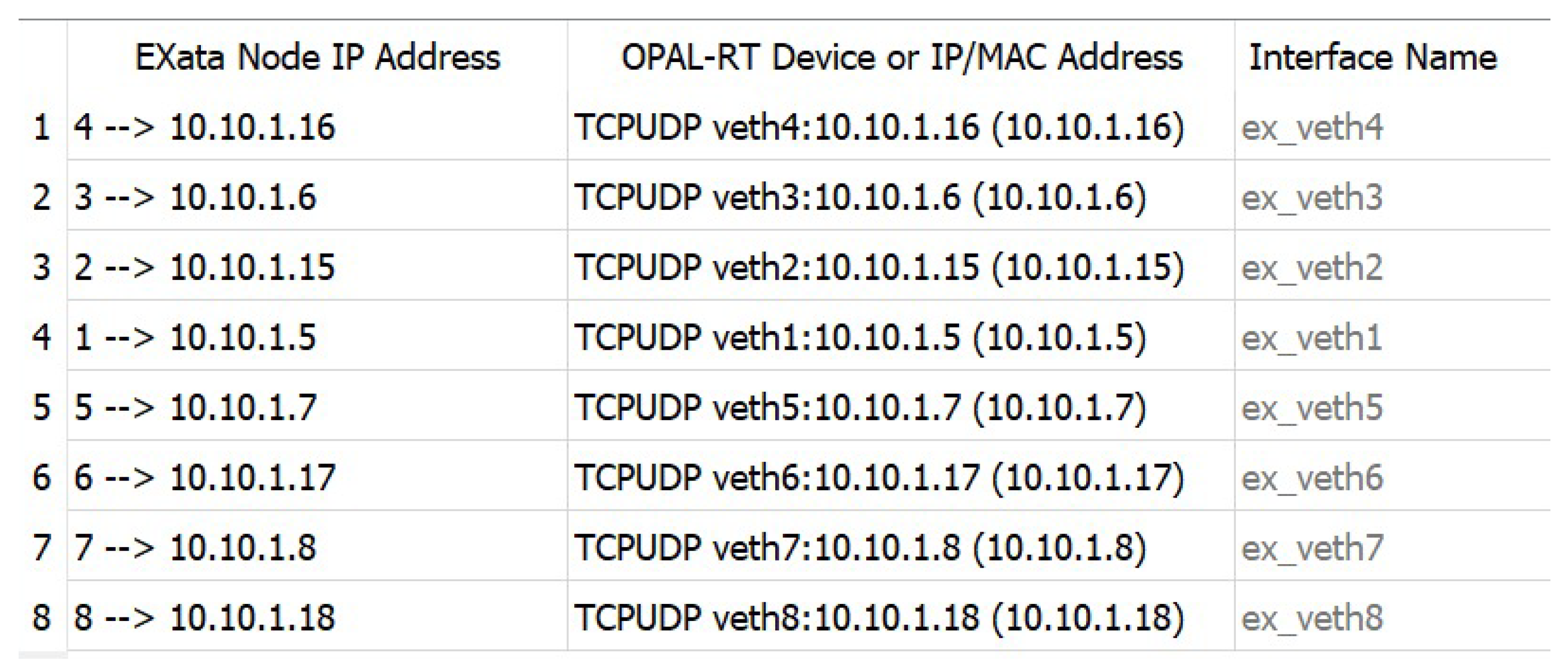

Section 3 describes the cyber-physical architecture, including the co-simulation interface between the OPAL-RT and EXata platforms.

Section 4 presents experimental results that analyze both the physical performance of the controllers during disturbances and their cyber-resilience under attack conditions. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with a summary of findings and a discussion.

2. Microgrid Configuration and Control Strategy

2.1. Microgrid Configuration

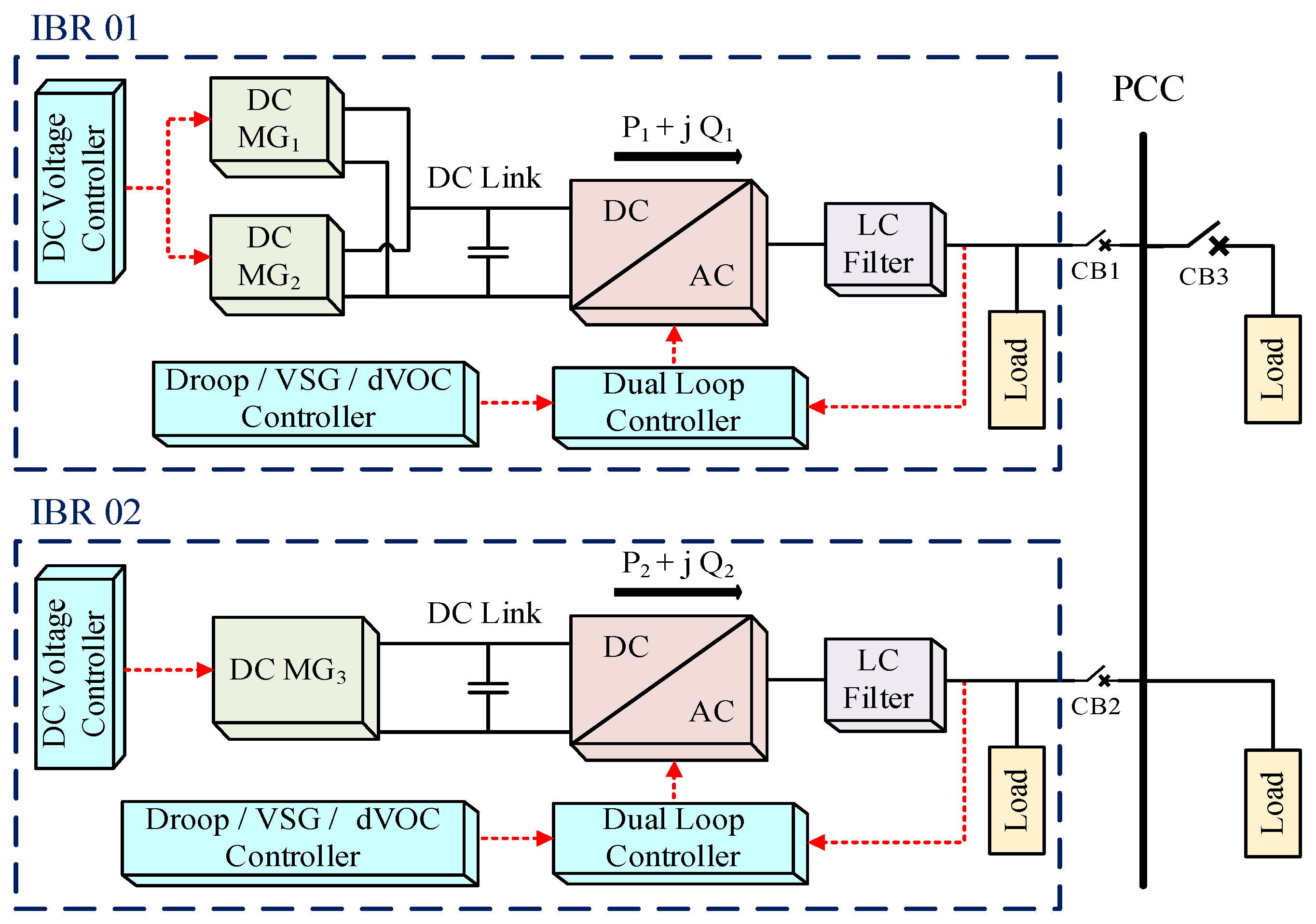

The experimental architecture features a hybrid AC microgrid topology in which two IBRs operate as parallel grid-forming units. As illustrated in

Figure 1, independent operation is ensured through dedicated DC power supplies and autonomous local controllers, while both units collectively maintain voltage magnitude and frequency regulation at a shared AC bus. The interface between each inverter and the AC network comprises three-phase circuit breakers and

filter networks, which provide essential voltage conditioning and protective functionality.

A defining characteristic of this setup is the dual-responsibility load configuration: each grid-forming unit supplies a dedicated local load while simultaneously contributing to a Point of Common Coupling (PCC) where common loads are aggregated. This symmetrical and modular architecture facilitates the evaluation of dynamic interactions across varying load profiles. Operational flexibility is inherent to the design, enabling the investigation of three distinct scenarios: (1) individual islanded operation, where a single unit supplies all system loads; (2) synchronized parallel operation, where load responsibility is shared; and (3) fault-induced reconfiguration, involving transitions between operating modes. Comprehensive real-time instrumentation at each local node and the PCC captures voltage and current measurements to assess stability and control robustness

2.2. Inner Loops Control

The instantaneous active () and reactive () powers are calculated in the synchronous reference frame using the measured voltage and current components, scaled for power invariance, where and .

To eliminate switching noise and decouple the outer control loops from high-frequency inverter dynamics, these raw power signals are processed through a discrete-time first-order Low-Pass Filter (LPF). The cutoff frequency is set to 5 Hz for all three control strategies. While this filtering introduces a measurement time constant ( ms), applying identical filtering parameters to Droop, VSG, and dVOC ensures that the comparison of transient response and settling times is unbiased. The control algorithms are executed on the DSP with a uniform sampling frequency of 10 kHz (), ensuring consistent discrete-time implementation across all experimental cases.

2.2.1. Voltage Control Loop

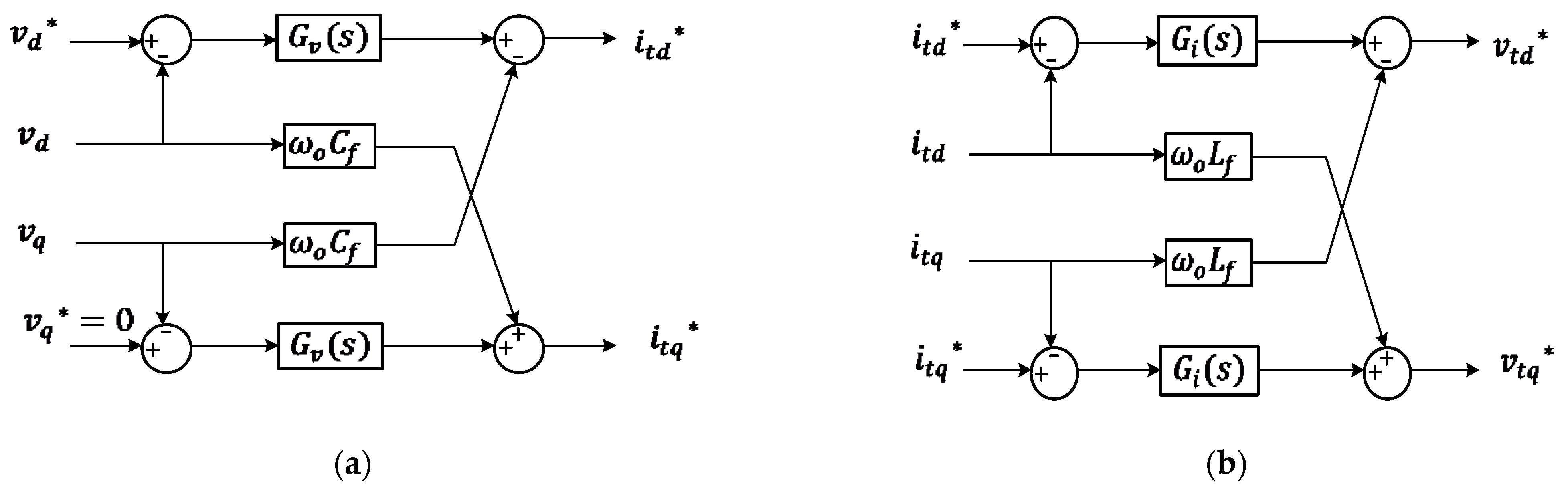

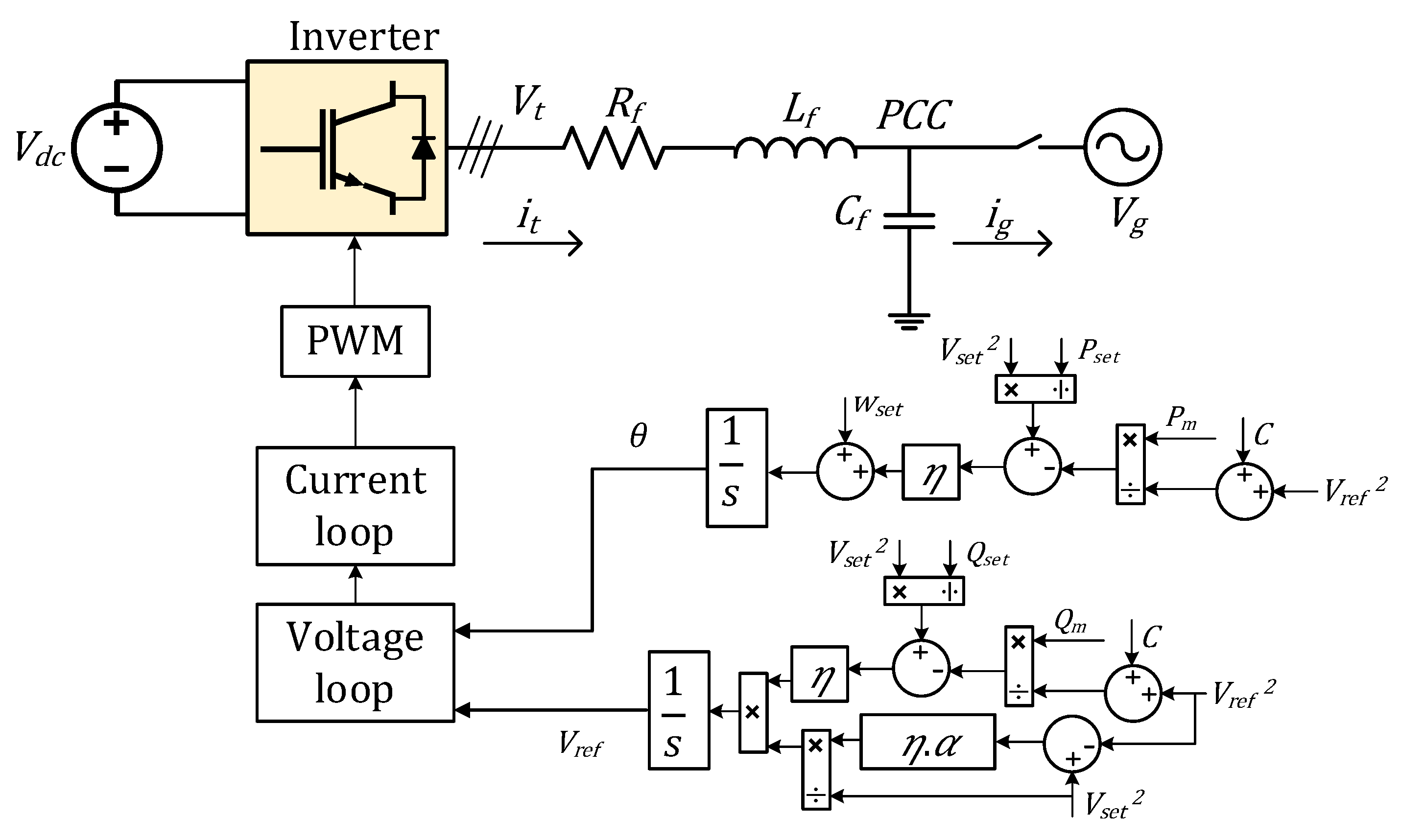

The outer voltage control loop, illustrated in

Figure 2a, is cascaded with the inner current loop to regulate the inverter output voltage within the synchronous

reference frame. This control stage ensures the measured voltages (

,

) track their respective setpoints (

,

) by generating the necessary reference currents (

,

) for the inner loop [

36]. The control logic utilizes a Proportional-Integral (PI) compensator,

, to minimize the voltage error. To improve transient response and reject disturbances, the control law incorporates feedback for the load currents (

,

) and cross-coupling decoupling terms (

,

), as defined in Equations (1)–(3):

where

represents the susceptance of the filter capacitor (corresponding to the

gain), and

and

are the proportional and integral gains, respectively. As indicated in the standard cascaded control design1, the voltage loop bandwidth is selected to be lower than that of the inner current loop to ensure stability and precise steady-state regulation.

2.2.2. Current Control Loop

The inner current control loop, depicted in

Figure 2b, is designed with a high bandwidth to ensure rapid and precise tracking of the reference currents (

,

). This stage utilizes a PI controller,

, to minimize tracking errors, while incorporating cross-coupling decoupling terms (

,

) to compensate for the dynamic interaction [

36]. The control law governing the inverter terminal voltage references (

,

) is given by Equations (4)–(6):

where

represents the filter inductive reactance (

) and

is the PI transfer function characterized by the gains

and

.

2.2.3. Filter Dynamics

The output of filter determines the inverter’s physical dynamics, which suppresses high frequency switching harmonics. The evolution of the state variables—inductor currents and capacitor voltages—is governed by the differential equations that describe the filter inductor (7)–(8) and the filter capacitor (9)–(10). These dynamics are critical for system modeling and control tuning:

Filter Inductor Dynamics:

Filter Capacitor Dynamics:

where

,

, and

denote the filter inductance, resistance, and capacitance, respectively.

The inverter output is interfaced with the AC network through an LC filter whose resonance frequency (

). Using the parameters listed in

Table 1, the LC filter resonance is located at approximately 130 Hz. To prevent excitation of this resonant mode during large-signal disturbances, such as faults and reconnection events, a strict hierarchy of control bandwidths is enforced. The inner current control loop, which regulates the filter inductor current, is designed as the fastest loop. Its bandwidth is primarily determined by the proportional current gain and the filter inductance. It is approximately 636 Hz, ensuring rapid current tracking and active damping of the LC dynamics. The inner voltage control loop regulates the filter capacitor voltage and is intentionally designed with a bandwidth significantly lower than the LC resonance bandwidth. Based on the voltage controller gain and the filter capacitance, the voltage loop bandwidth is approximately 53 Hz, providing a separation factor of about 2.5 with respect to the LC resonance frequency. This ensures that voltage control actions roll off before the resonance peak, thereby avoiding the amplification of oscillatory modes during transients.

The outer grid-forming control loops (Droop, VSG, and dVOC) operate at substantially lower bandwidths. For all strategies, the adequate control bandwidth is dominantly limited by the low-pass filter applied to the active and reactive power measurements, which has a cutoff frequency of 5 Hz. Specifically, the VSG dynamics emulate the swing equation of a synchronous machine, with virtual inertia and damping parameters selected to place the dominant electromechanical mode in the 2–5 Hz range. Similarly, the dVOC convergence gains yield dominant dynamics within a comparable low-frequency range.

This clear separation of time scales, where the current loop is the fastest, followed by the voltage loop, and finally the outer grid-forming loops, ensures that the LC filter resonance is not excited during fault and reconnection events. Consequently, the transient behavior observed in the experimental results is governed by grid-forming control strategies rather than by filter-induced resonant dynamics.

2.3. Droop Control Strategy

Among decentralized power-sharing techniques for inverter-based microgrids, droop control has achieved widespread adoption due to its straightforward implementation, inherent scalability, and seamless compatibility with existing control architectures. The fundamental principle underlying this approach is to replicate the steady-state operational characteristics of synchronous generators in conventional power systems. Specifically, the control methodology establishes proportional relationships between power flows and voltage/frequency variables: active power output influences frequency regulation, while reactive power flow governs voltage magnitude control.

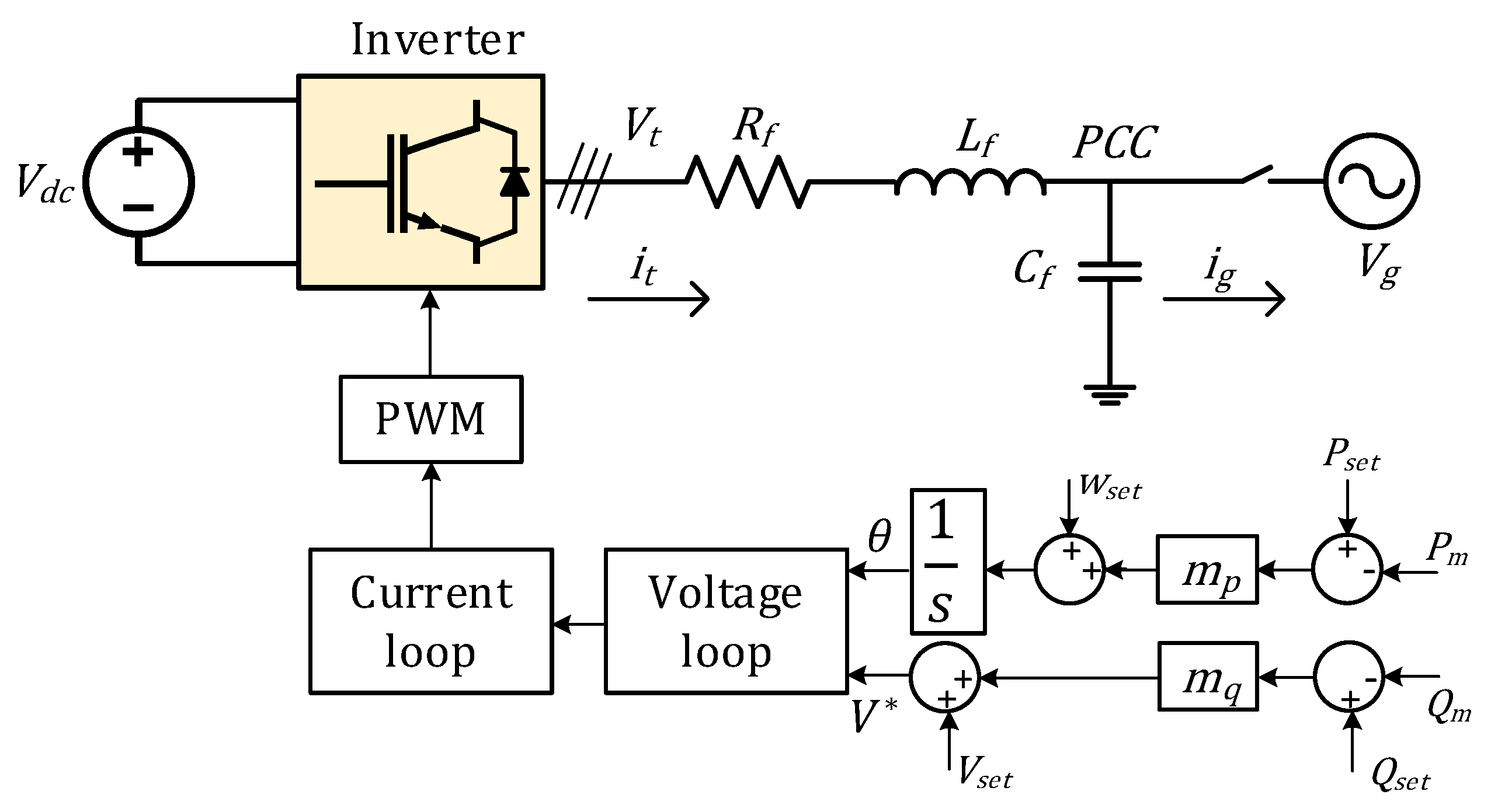

As illustrated in

Figure 3, this strategy emulates the natural response of a generator, where increased real power demand leads to a decrease in frequency, and increased reactive power demand results in a voltage drop. This mechanism enables autonomous load sharing among multiple parallel-connected inverters without necessitating a high-speed communication infrastructure or a central controller [

37]. The mathematical framework governing droop control establishes reference values for frequency and voltage magnitude through the following relationships,

In these expressions, and represent the measured and reference (setpoint) values of frequency, respectively, and and denote the measured and reference voltage magnitudes. Similarly, , , and , correspond to the measured and setpoint values of active and reactive power. The coefficients and define the droop gains for frequency and voltage regulation, respectively.

While the conceptual simplicity and seamless compatibility with existing control architectures contribute to the widespread deployment of droop control, the approach exhibits several inherent limitations that affect performance under challenging operating conditions [

37]. A fundamental shortcoming stems from the control’s reliance on steady-state phasor approximations rather than dynamic electromechanical modeling. Consequently, droop control fails to replicate the transient swing equation behavior of synchronous generators and lacks intrinsic inertial response characteristics [

38]. This deficiency becomes particularly problematic in low-inertia power systems or during fault conditions, where a rapid dynamic response is crucial for maintaining stability.

2.4. VSG Control Strategy

As mentioned, the VSG control strategy represents a fundamentally different approach to grid-forming operation compared to static droop-based methods. While droop control establishes power sharing through proportional steady-state relationships, VSGs replicate the dynamic electromechanical characteristics of conventional synchronous generators by explicitly incorporating inertia and damping mechanisms within the voltage-source inverter control architecture. This emulation of physical machine behavior enables inverters to actively contribute to grid stability in low-inertia power systems, providing transient support that purely algebraic control methods cannot achieve [

17].

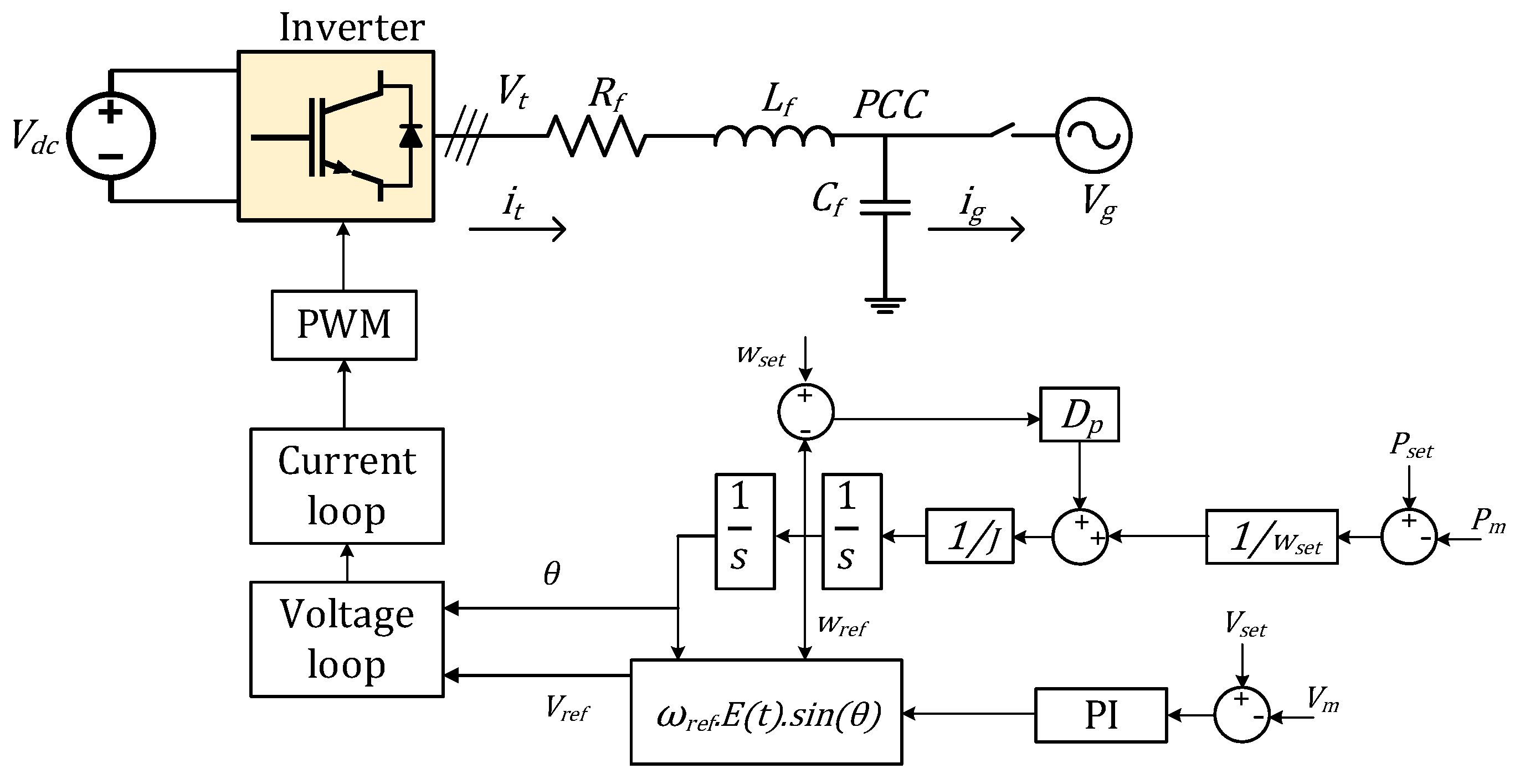

Central to the VSG control framework is the swing equation, a fundamental relationship borrowed from synchronous machine theory that governs rotational dynamics in conventional generators, as shown in

Figure 4. Within the VSG context, this equation determines the evolution of the reference angular frequency in response to instantaneous power imbalances and damping effects. The mathematical representation is expressed as,

where

is the virtual inertia constant,

is the instantaneous reference angular frequency, and

is the virtual damping coefficient [

1]. The angular phase reference

is obtained by integrating the reference frequency.

These power measurements serve dual purposes: they provide feedback for the swing equation, which governs frequency dynamics, and enable reactive power-based voltage regulation to maintain system voltage profiles. Beyond frequency control through the swing equation, VSG implements comprehensive voltage magnitude regulation through an internal electromotive force (EMF) control mechanism. This voltage control law dynamically adjusts the internal voltage source amplitude based on both voltage magnitude deviations from the reference value and reactive power errors, which indicate the system’s voltage support requirements. The governing differential equation is formulated as,

where

is the internal EMF amplitude,

is the voltage control time constant that governs the speed of EMF response,

is the gain that determines how strongly reactive power error influences the EMF.

The culmination of these control elements, frequency regulation via the swing equation, phase generation through frequency integration, and voltage magnitude control through EMF dynamics, produces three-phase voltage references in the stationary

-frame. The transformation from internal control variables to physical voltage commands is accomplished through.

This mathematical structure enables the inverter to autonomously generate synchronized, balanced three-phase voltage waveforms, independent of external synchronization signals or phase-locking mechanisms. The self-sustained voltage generation capability represents a defining characteristic of grid-forming operation, distinguishing VSG from grid-following control methods that require external references [

17].

2.5. Virtual Oscillator Control Strategy

Virtual oscillator control establishes grid-forming behavior by leveraging internal nonlinear oscillator dynamics to generate voltage waveforms, thereby eliminating the need for external synchronization mechanisms, such as Phase-Locked Loops (PLL). Unlike traditional droop methods that rely on averaged power quantities in the frequency domain, VOC operates directly in the time domain. This inherently dynamic approach facilitates rapid, communication-free synchronization among distributed inverters [

39]. The generalized voltage evolution law for VOC strategies is defined as follows [

40],

where

represents the inverter voltage vector,

is the nominal frequency,

is the 90° rotation matrix, and

denotes a nonlinear feedback function dependent on voltage and current.

While classical VOC implementations achieve synchronization, they often lack programmable power dispatchability and may exhibit performance degradation under load imbalances. To address these limitations, dVOC was developed to embed active and reactive power setpoints directly into the oscillator framework, enabling precise power control while maintaining the robust synchronization and almost global asymptotic stability characteristic of VOC, as illustrated in

Figure 5. To facilitate real-time execution on embedded hardware, this work adopts a scalar formulation of dVOC. This approach governs the system dynamics through five coupled time-domain differential equations, regulating frequency, phase, and voltage magnitude. This formulation eliminates the computational burden of matrix operations and low-pass filtering required by vector-based implementations.

The scalar dynamics of dVOC are governed by the following equations. First, the instantaneous frequency

is modulated by the active power tracking error as follows,

where

and

are the reference and measured active power,

and

are the reference and measured voltage magnitudes,

is the response gain, and

is a regularization term to prevent instability at low voltages.

The instantaneous phase angle

is derived by integrating the modulated frequency, generating a continuously evolving phase reference as follows,

Two components drive the dynamics of voltage magnitude. Equation (20) regulates the response to reactive power imbalances, while Equation (21) provides a voltage restoration mechanism as follows,

Here,

serves as the voltage amplitude regulation gain and

ensures numerical stability. Finally, the total voltage magnitude reference

is synthesized by integrating the combined effects of the reactive power and amplitude control dynamics:

This coupled formulation ensures that active/reactive power tracking and voltage regulation are achieved simultaneously within a unified time-domain framework.

2.6. Control Parameter Selection

The key control parameters for each strategy were selected to balance transient stability, oscillation damping, and steady-state load sharing while enforcing a strict bandwidth hierarchy suitable for low-inertia microgrids, as listed in

Table 1:

Droop Control: The active power droop slope () was tuned to define the steady-state load-sharing stiffness, ensuring accurate power distribution without causing frequency deviations exceeding 1%. Similarly, the reactive power slope () was selected to balance voltage regulation against coupling with feeder impedance. Crucially, the bandwidth of the outer droop loop is strictly limited by the measurement low-pass filter. This filter rejects high frequency switching noise and ensures the control dynamics remain well below the system’s LC resonance frequency ( Hz).

Virtual Synchronous Generator Control: The VSG parameters were derived directly from the desired swing equation dynamics.

Virtual Inertia (J): This parameter was calculated to constrain the maximum Rate of Change of Frequency (RoCoF) during a worst-case load step (), governed by . As clarified in terms of transient performance, virtual inertia primarily constrains RoCoF; increasing reduces the initial frequency rate of change during sudden power imbalance events but typically increases the settling time by lowering the system’s natural frequency. Accordingly, was set to 0.05 kg·m2.

Virtual Damping (): The damping coefficient was tuned to define the transient decay characteristics. Considering the characteristic equation of the electromechanical loop (), was selected to achieve a damping ratio of approximately (critical damping). This minimizes power overshoot while ensuring a rapid settling time. Increasing reduces overshoot and oscillations and shortens settling time; however, excessive damping can make the response overly sluggish.

Dispatchable Virtual Oscillator Control:

Synchronization Gain (): This gain sets the overall convergence speed of the oscillator dynamics. While larger reduces settling time, it can increase overshoot or ringing if the effective damping margin is reduced or if the outer-loop bandwidth approaches the inner voltage loop bandwidth limits (53 Hz).

Amplitude Gain (): This parameter weights the contribution to voltage magnitude regulation. Larger accelerates voltage recovery following disturbances but can increase voltage overshoot and transient oscillations. Based on these trade-offs, was selected to maintain frequency separation from the LC resonance, and was set to 10 to provide stiff voltage recovery without instability.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

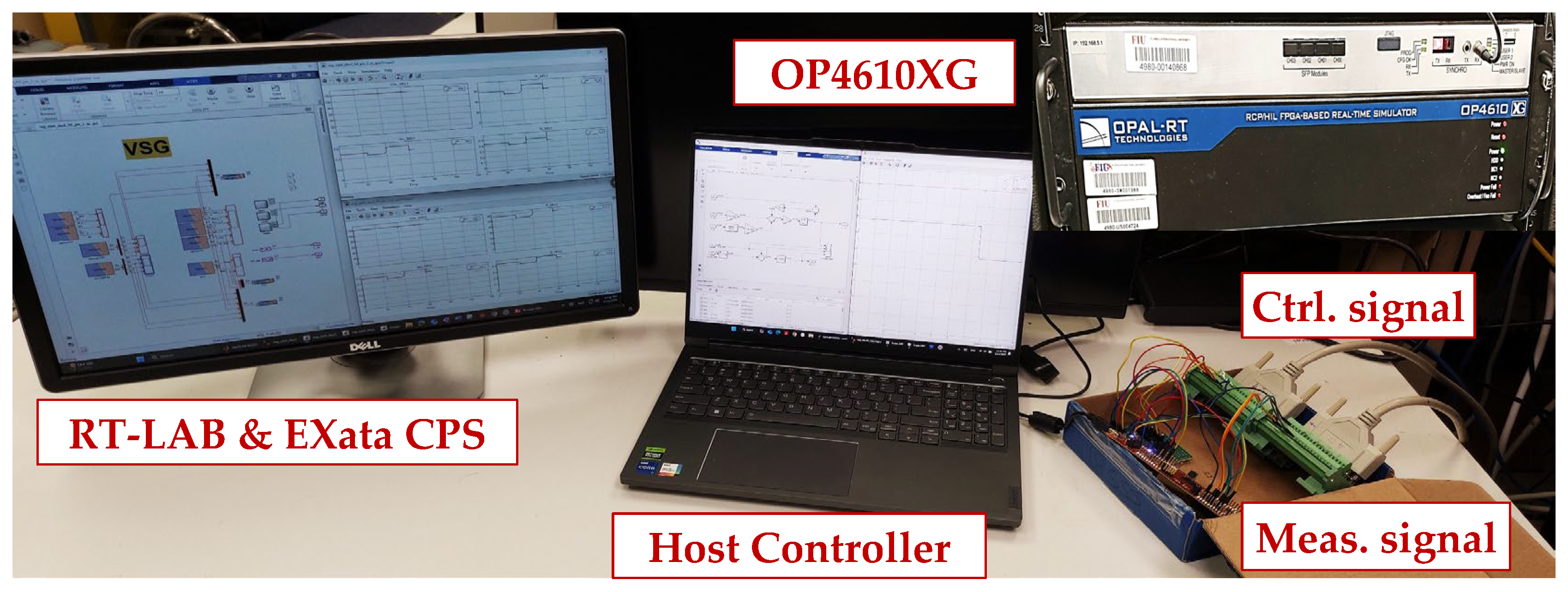

The model architecture is designed to facilitate a seamless transition from offline time-domain simulation in MATLAB 2023b/Simulink to real-time HIL deployment using OPAL-RT and TI C2000 microcontrollers, as illustrated in

Figure 9. The design explicitly accounts for the computational and sampling constraints inherent to embedded implementation. All critical sensing points—comprising inverter-side voltages, currents, and PCC feedback—are routed to a dedicated cyber layer that synthesizes voltage magnitude, generates frequency, and tracks active/reactive power. To ensure valid performance comparisons, the system maintains strict parameter consistency between the simulation environment and the HIL setup. Each IBR is rated at 150 W of active power, with a nominal peak phase voltage of 80 V, and connects to the AC network through a second-order LC filter. Local and common loads are modeled as R-L branches. At the same time, the DC side is energized by a regulated source with internal impedance and bulk capacitance to emulate realistic energy storage behavior. The control structure employs conventional PI regulators for the inner loops, with all key system parameters, including inverter ratings, filter components, and load profiles, summarized in

Table 1. This multi-platform approach provides a rigorous testbed for evaluating control resilience against both physical operational disturbances and cyber-layer vulnerabilities.

While the proposed models and control architecture are inherently scalable to higher power ratings, the experimental validation in this study was intentionally limited to 150 W per unit, representing a scaled laboratory microgrid. This choice reflects practical constraints related to laboratory safety and equipment ratings. Furthermore, the communication network used in the co-simulation was relatively simple; however, increasing network complexity in larger microgrid clusters may introduce additional latency and traffic congestion, further challenging the cyber-resilience of the control layer. It is important to emphasize that although experimental validation was conducted on a scaled 150 W prototype, the results serve to validate the proposed control logic and cyber-resilience algorithms in a hardware-constrained environment. The observed dynamic behaviors and cyber-physical interactions are therefore representative of larger inverter-dominated microgrids, even though the absolute demonstration of the effectiveness of the power level is scaled for laboratory implementation.

4.1. Operational Resilience Scenarios

In this section, the experimental validation focuses on three cardinal scenarios: Islanded, Parallel, and Fault operation. These were selected to rigorously evaluate the fundamental requirements of grid-forming inverters: the ability to autonomously establish voltage, the capability to share load cooperatively, and the resilience to ride through severe physical disturbances.

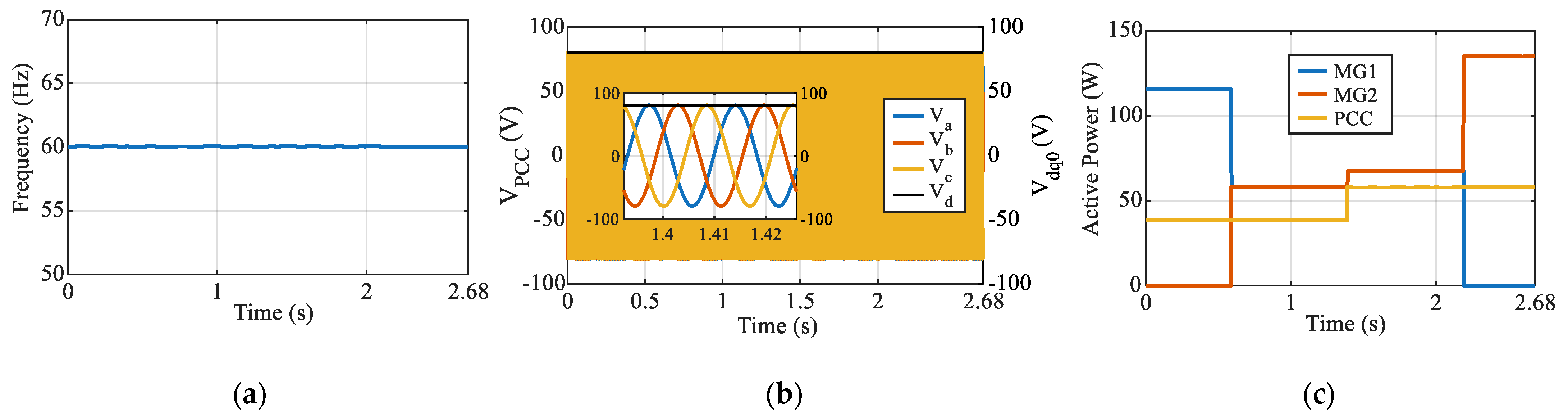

4.1.1. Scenario 1: Islanded Operation

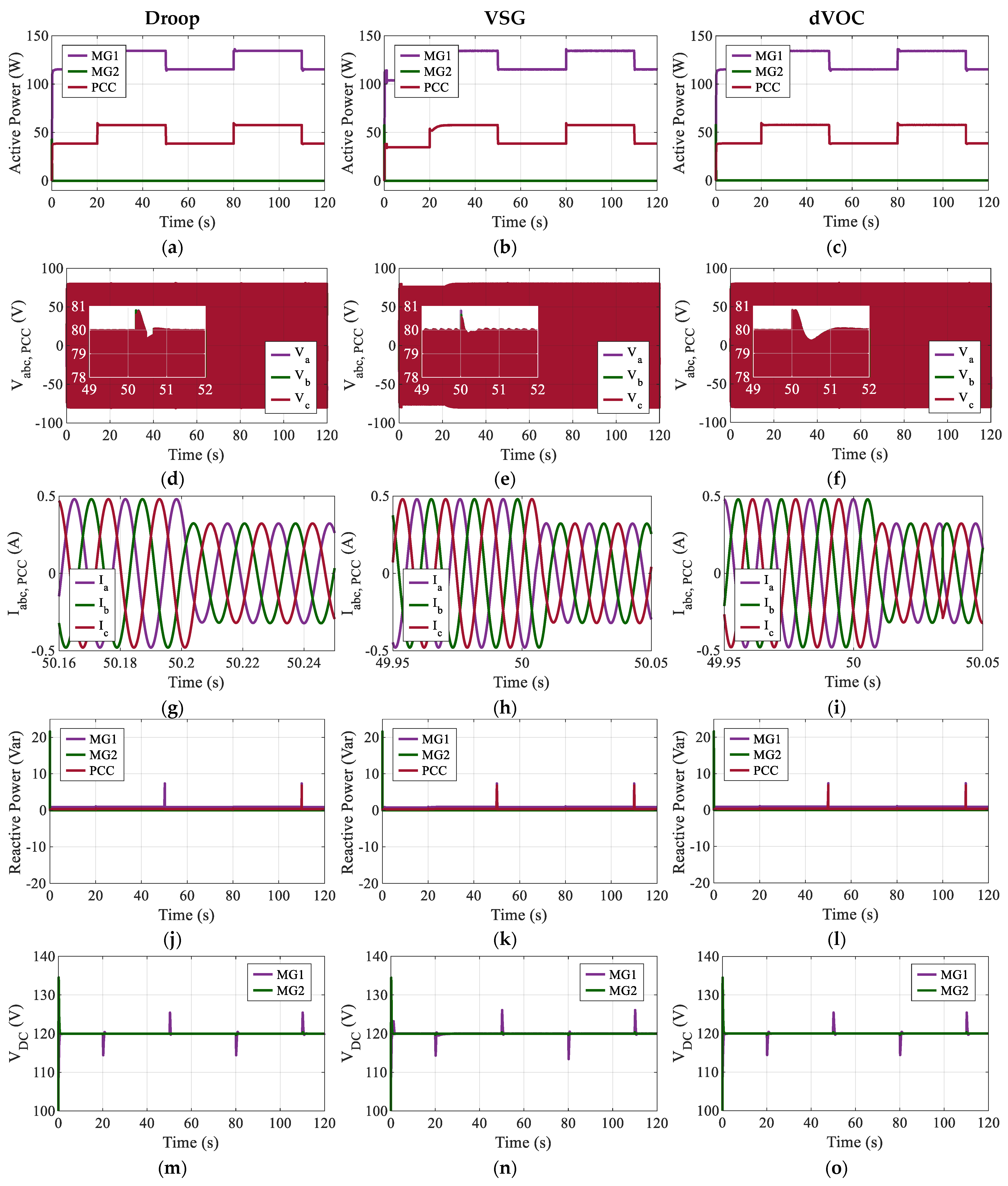

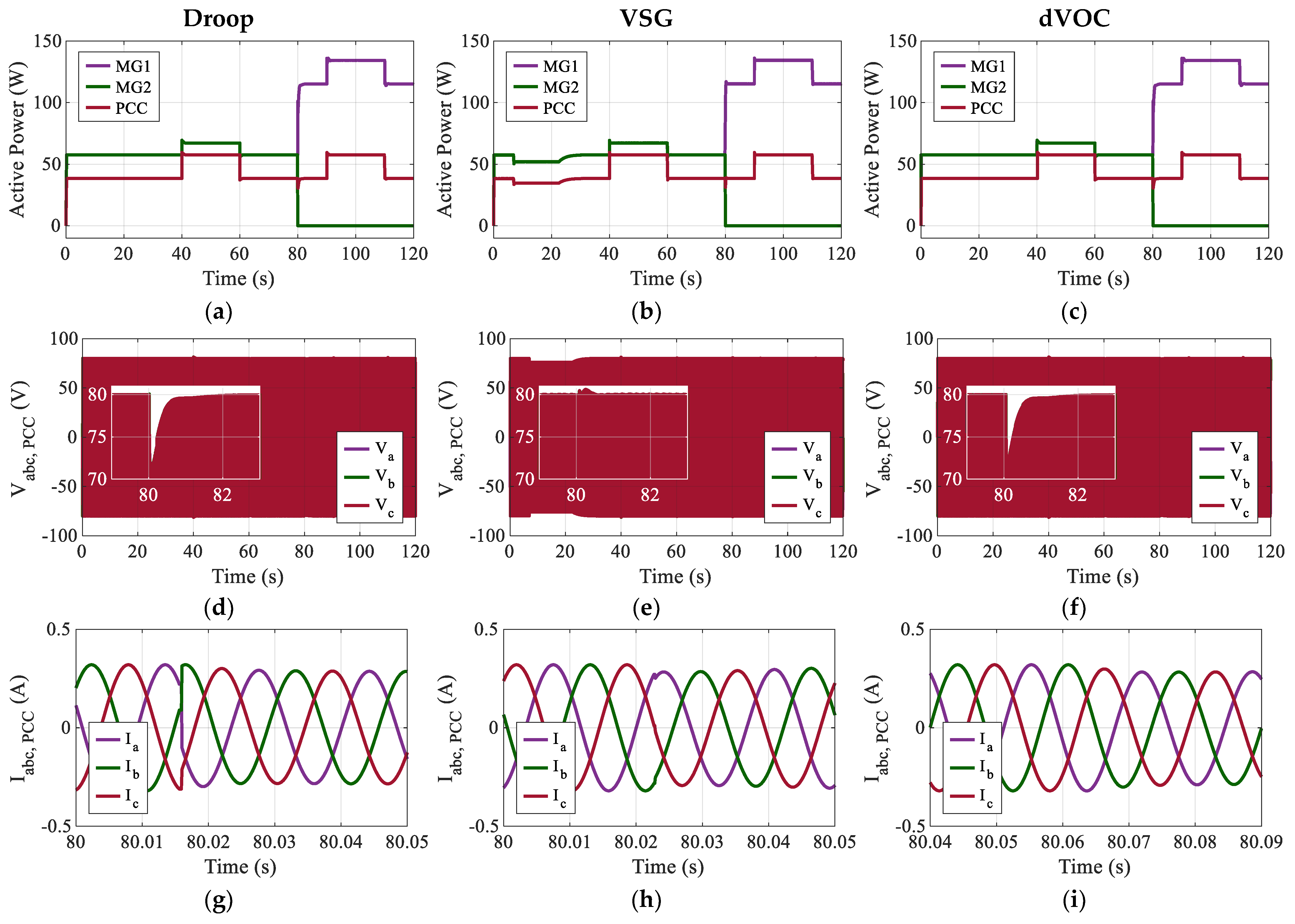

In Case 1, where MG2 is disconnected, MG1 operates as the sole source. As shown in

Figure 10a–c, MG1 supplies the total demand, delivering approximately 135 W during peak loading. Meanwhile, the active power at the PCC ranges from roughly 40 to 60 W. Since MG1 supplies its own local load, the unconnected MG2 load is effectively removed from the system dynamics. In

Figure 10a, employing droop control, MG1 follows the PCC load steps but exhibits a transient power overshoot of 1.273 W with a recovery time of 2.14 s. In comparison, the VSG control in

Figure 10b demonstrates superior active power transient suppression, yielding the lowest power overshoot of 0.548 W and the fastest settling time of 0.63 s, resulting in a visibly smoother response. The dVOC strategy in

Figure 10c tracks the commanded step changes with an overshoot of 1.295 W and a settling time of 1.835 s, achieving performance metrics comparable to droop control but with slightly faster recovery.

In

Figure 10d–f, the PCC phase voltages are regulated around the 80 V reference. Upon load changes, all three controllers effectively limit the voltage peak. According to the quantitative metrics, the voltage peak is approximately 80.8 V (roughly 1% overshoot). The VSG controller in

Figure 10e achieves the fastest voltage recovery, settling in just 0.45 s with a peak of 80.8 V. Droop control in

Figure 10d records a similar peak of 80.82 V but requires 1.4 s to recover. The dVOC response in

Figure 10f exhibits the longest voltage settling time of 1.86 s following the transient, despite maintaining a peak voltage of 80.8177 V, which is comparable to the other methods. While VSG offers the fastest numeric recovery, the waveform in

Figure 10e presents a characteristic medium-term oscillation before fully stabilizing, whereas dVOC shows a slower but monotonic decay. Power quality was evaluated for all three strategies under nominal conditions. The measured Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) voltage was well within the IEEE 519 standard limit of 5%, with values of 1.6378% for Droop, 0.6112% for VSG, and 0.9068% for dVOC, confirming that the VSG strategy provides the highest waveform quality.

In

Figure 10g–i, the PCC phase currents remain balanced and sinusoidal with peak magnitudes adjusting to the load steps. While the waveforms appear visually similar, the transient settling times differ significantly among the controllers. Consistent with the active power results, VSG in

Figure 10h achieves the fastest current settling time of 0.45 s, followed by dVOC in

Figure 10i at 1.0 s, and droop in

Figure 10g at 1.2 s.

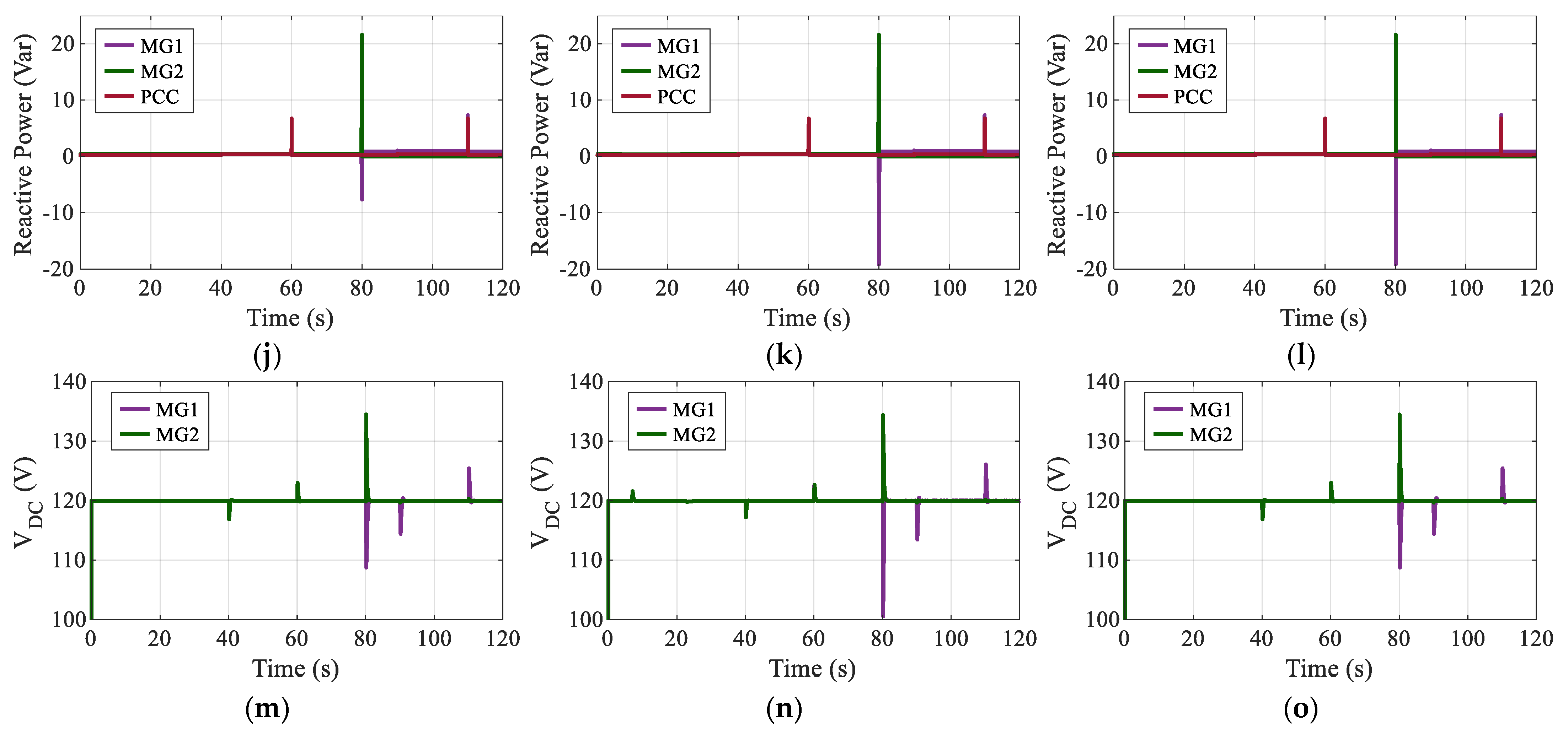

In

Figure 10j–l, the reactive power is regulated near zero. MG1 exhibits brief transient spikes at the load step instants (approx. 50 s and 110 s). VSG again demonstrates the most damped response, with a reactive power overshoot of only 0.0033 Var (normalized/scaled) and a rapid recovery of 0.46 s. In contrast, droop and dVOC exhibit higher transient overshoots of 0.0078 V and 0.007 V, respectively, with identical recovery times of approximately 1.867 s. This confirms that VSG provides tighter reactive power regulation during islanded switching events.

For the DC link voltages in

Figure 10m–o, regulation is maintained around the 120 V reference. The DC bus peak deviation and recovery times vary depending on the control strategy. Droop and dVOC minimize the peak deviation to approximately 5.4 V; however, droop recovers significantly faster (1.06 s) compared to dVOC, which requires 2.218 s to settle—the slowest DC link recovery among the three. VSG allows a slightly higher DC voltage peak deviation of 6.08 V but compensates with the fastest recovery time of 0.97 s. A comprehensive summary of these quantitative results is listed in

Table 2.

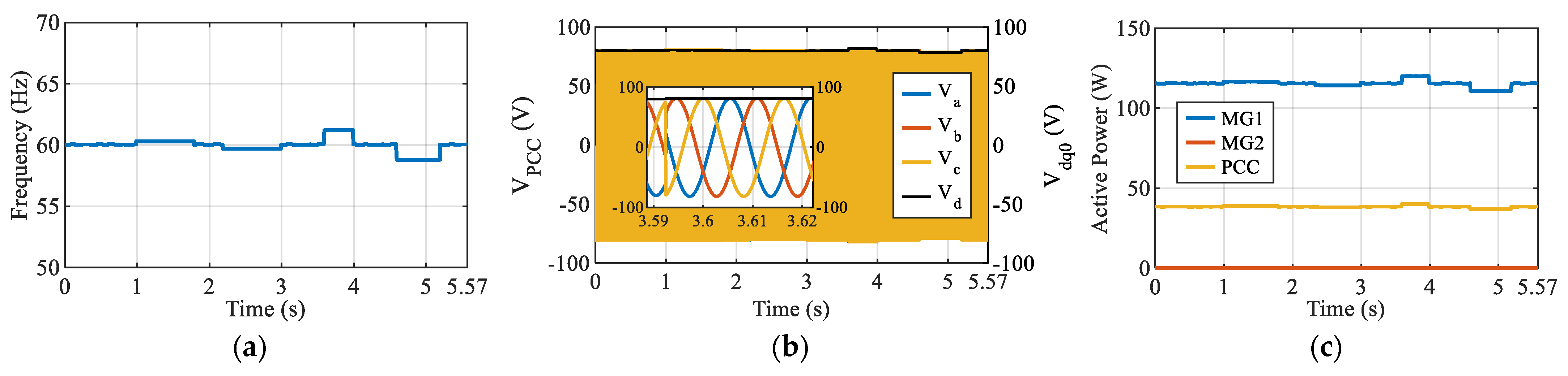

4.1.2. Scenario 2: Parallel Operation

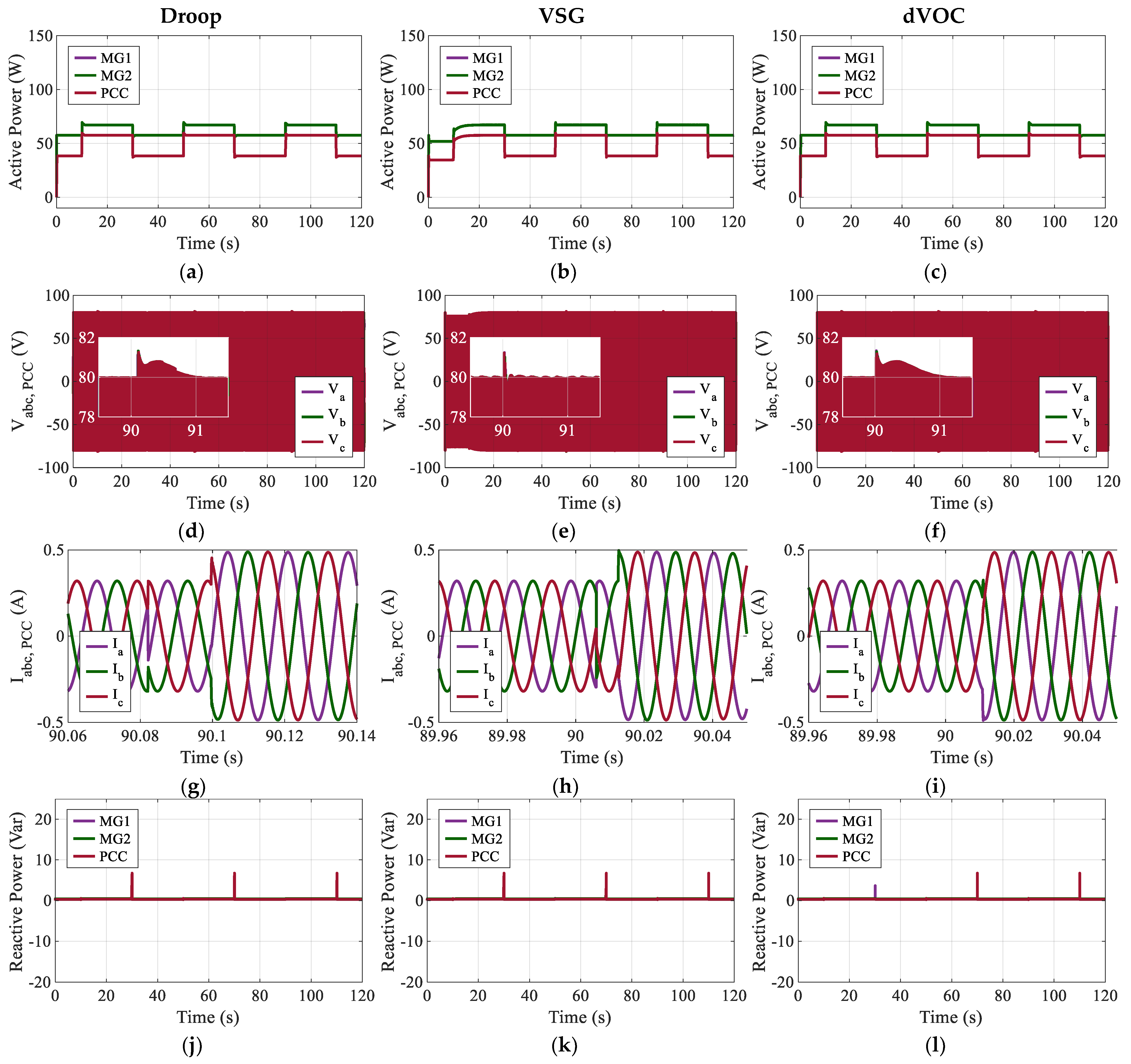

In Case 2, MG1 and MG2 operate in parallel, each supplying its local load while jointly feeding the common variable load at the PCC. Consequently, the active power outputs of MG1 and MG2 exceed the PCC active power, as each unit must cover its local demand in addition to its share of the common load. As shown in

Figure 11a–c, the two microgrid units under droop, VSG, and dVOC control track the step changes in the PCC load effectively. However, the transient performance varies: the VSG controller in

Figure 11b demonstrates the superior response with the lowest power overshoot of 1.73 W and the fastest recovery time of 0.2 s. In contrast, droop control in

Figure 11a and dVOC in

Figure 11c exhibit higher overshoots (1.95 W and 1.98 W, respectively) and significantly longer recovery times of 1.03 s and 1.26 s.

In Case 2, the PCC voltages in

Figure 11d–f remain tightly clustered around the 80 V reference. The zoomed insets reveal that all three controllers produce a similar voltage swell during the load step, peaking at approximately 81.3 V. The primary distinction lies in the recovery speed. The VSG case in

Figure 11e exhibits the fastest decay back toward 80 V, settling in just 0.2 s, whereas the droop response in

Figure 11d takes 1.0 s and dVOC in

Figure 11f takes 1.2 s. While VSG offers the fastest recovery, its waveform shows a slightly more pronounced steady-state ripple compared to the smoother trajectory of the dVOC strategy.

For

Figure 11g–i, the PCC currents under all three controllers appear as balanced, sinusoidal three-phase waveforms. Despite the visual similarity, the settling times differ markedly. The VSG controller in

Figure 11h settles the current in a remarkable 0.144 s. This is substantially faster than the droop controller in

Figure 11g, which takes 0.975 s to settle, and the dVOC controller in

Figure 11i, which takes 1.197 s to settle.

To evaluate whether the improved transient performance of the VSG strategy compromises steady-state accuracy, the relative active power-sharing error () was used as a quantitative metric. It is defined as , where and denote the steady-state active power outputs of the two units, and represents the nominal power rating.

The calculated steady-state errors confirm that steady-state precision is maintained across all topologies. As listed in

Table 2, the Droop and dVOC controllers achieved perfect symmetry with both units settling at 67.18 W (

). Similarly, the VSG strategy settled at 67.2 W per unit, also resulting in a negligible sharing error of

0%. These results indicate that including virtual inertia and damping terms in the VSG control structure improves dynamic stiffness and settling time without introducing steady-state deviations. Consequently, the VSG strategy effectively decouples dynamic performance improvements from steady-state accuracy, achieving fast transient response while maintaining precise power allocation among parallel units.

Regarding reactive power in

Figure 11j–l, MG1, MG2, and the PCC remain regulated close to 0 Var, exhibiting only short transient spikes at the load step instants. In this metric, droop control in

Figure 11j achieves the lowest overshoot of 0.0074 Var (normalized), compared to 0.0115 Var for VSG and 0.0125 Var for dVOC. However, regarding settling time, VSG in

Figure 11k is again the fastest, recovering in 0.1588 s. In contrast, droop and dVOC require 0.8227 s and 1.288 s, respectively.

Finally, for the DC link voltages in

Figure 11m–o, regulation is maintained around the 120 V reference. The VSG controller in

Figure 11n provides the tightest regulation, limiting the peak deviation to 2.695 V and achieving a rapid recovery time of 0.7644 s. Both droop in

Figure 11m and dVOC in

Figure 11o result in a higher peak deviation of roughly 2.99 V and longer recovery times of approximately 1.42 s. A comprehensive summary of these quantitative results is listed in

Table 2.

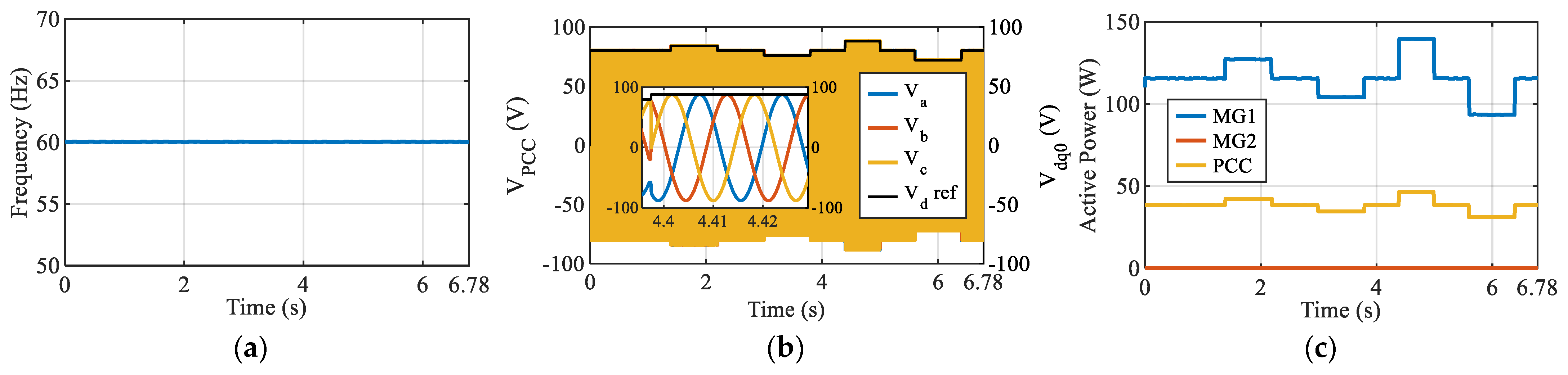

4.1.3. Scenario 3: Fault Operation

In this Scenario, a unit-outage contingency was emulated rather than a bolted electrical short circuit. The disturbance was applied at the PCC interface by forcing MG2 to zero output at thereby representing an inverter trip (open-circuit equivalent with effectively high fault impedance) due to protection action during a severe grid disturbance. Following the trip event, MG1 was required to supply the full system demand, and the PCC voltage and power recovery trajectories were used to quantify the fault-ride-through behavior of droop, VSG, and dVOC under a critical loss-of-unit condition that is frequently encountered in inverter-dominated microgrids.

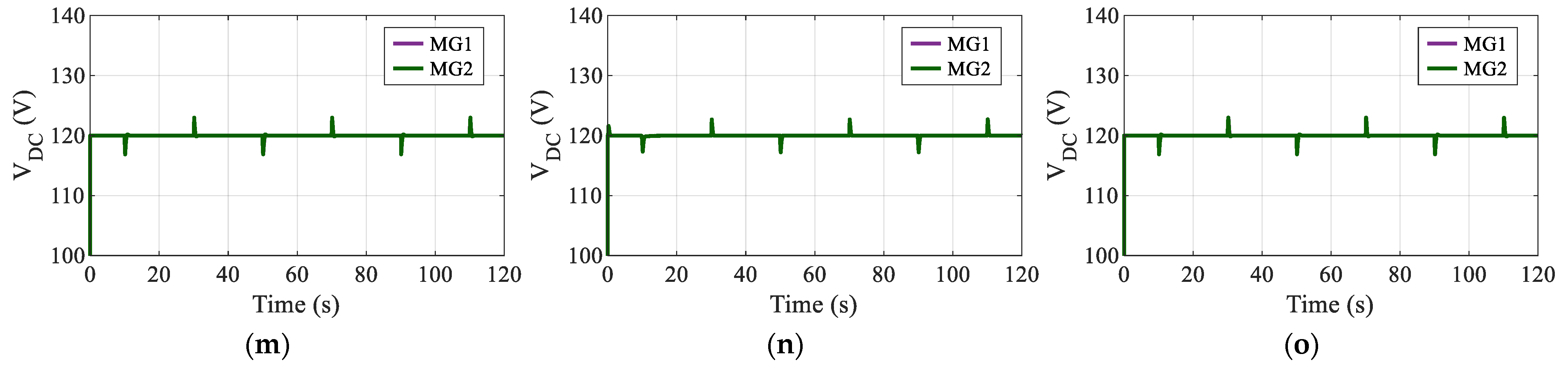

In Case 3,

Figure 12a–c show the active power of MG1, MG2, and the PCC for droop, VSG, and dVOC control. Before the fault (t < 80 s), both inverters operate in parallel, with MG1 and MG2 each supplying roughly 57–67 W, while the PCC power steps between 38 and 57 W. When the fault is applied at t = 80 s, and MG2 is forced to zero output, MG1 must ramp up to support the full system demand. The VSG control in

Figure 12b demonstrates the most robust transient response, achieving the lowest power overshoot of 7.154 W and the fastest settling time of 0.518 s. In contrast, droop control in

Figure 12a and dVOC in

Figure 12c exhibit higher overshoots of approximately 7.84 W and 7.86 W, respectively, with significantly slower recovery times of 3.36 s and 2.13 s.

In Case 3, the PCC voltage waveforms in

Figure 12d–f highlight distinct fault-ride-through behaviors at 80 s. All three controllers experience a voltage sag from the 80 V reference down to approximately 71 V (an ~11% dip). Specifically, the droop controller in

Figure 12d drops to a nadir of 71.371 V, while VSG in

Figure 12e and dVOC in

Figure 12f drop slightly lower to 70.867 V and 70.744 V, respectively. However, the critical difference lies in the recovery speed. The VSG controller recovers the voltage in just 0.525 s, whereas droop control requires 2.96 s and dVOC requires 2.64 s to return to steady state. Although VSG offers the fastest recovery, the waveform in

Figure 12e also reveals a pronounced undervoltage interval between 5 s and 20 s, which explains the temporary reduction in active power observed in the corresponding power plots.

For

Figure 12g–i, the PCC currents during the fault event remain balanced and nearly sinusoidal. Despite the visual similarity, the transient metrics favor the VSG strategy. The VSG controller in

Figure 12h achieves the fastest current settling time of 0.49 s after the fault. This performance surpasses that of the droop controller in

Figure 12g, which settles in 0.6 s, and the dVOC controller in

Figure 12i, which takes the longest at 0.72 s.

In Case 3, the reactive power profiles in

Figure 12j–l remain essentially zero, except for brief spikes at the fault application. At the fault instant (t = 80 s), MG2 exhibits a sharp positive reactive power spike while MG1 shows a corresponding negative spike. The VSG controller in

Figure 12k again provides the most damped response, limiting reactive power overshoot to 0.0534 Var (normalized) and achieving a rapid recovery of 0.67 s. Conversely, both droop control in

Figure 12j and dVOC in

Figure 12l exhibit larger overshoots of roughly 0.059 Var and require substantially longer times (approx. 2.1 s) to settle back to zero.

Finally, regarding the DC link voltages in

Figure 12m–o, a clear trade-off is observed. At the moment of the fault, the VSG controller in

Figure 12n experiences the largest DC voltage deviation, peaking at 19.448 V from the reference, yet recovers the fastest, in 1.3478 s. In comparison, the droop controller in

Figure 12m and the dVOC controller in

Figure 12o maintain tighter peak regulation with a deviation of approximately 11.2 V, but they take more than twice as long to recover, with settling times of 3.13 s and 3.05 s, respectively. A comprehensive summary of these quantitative results is listed in

Table 2.

4.1.4. Comparative Analysis and Selection for Cyber-Physical Evaluation

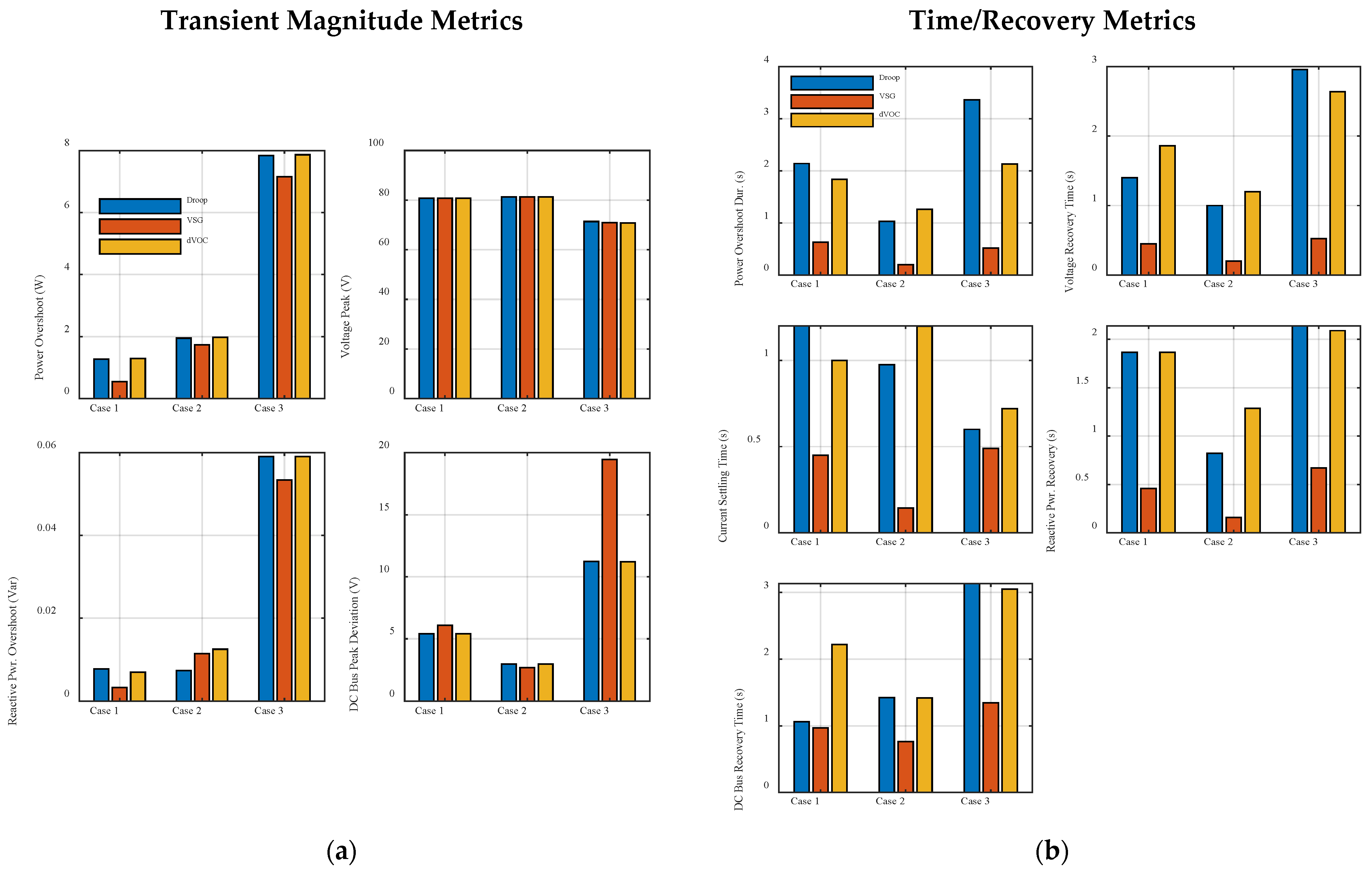

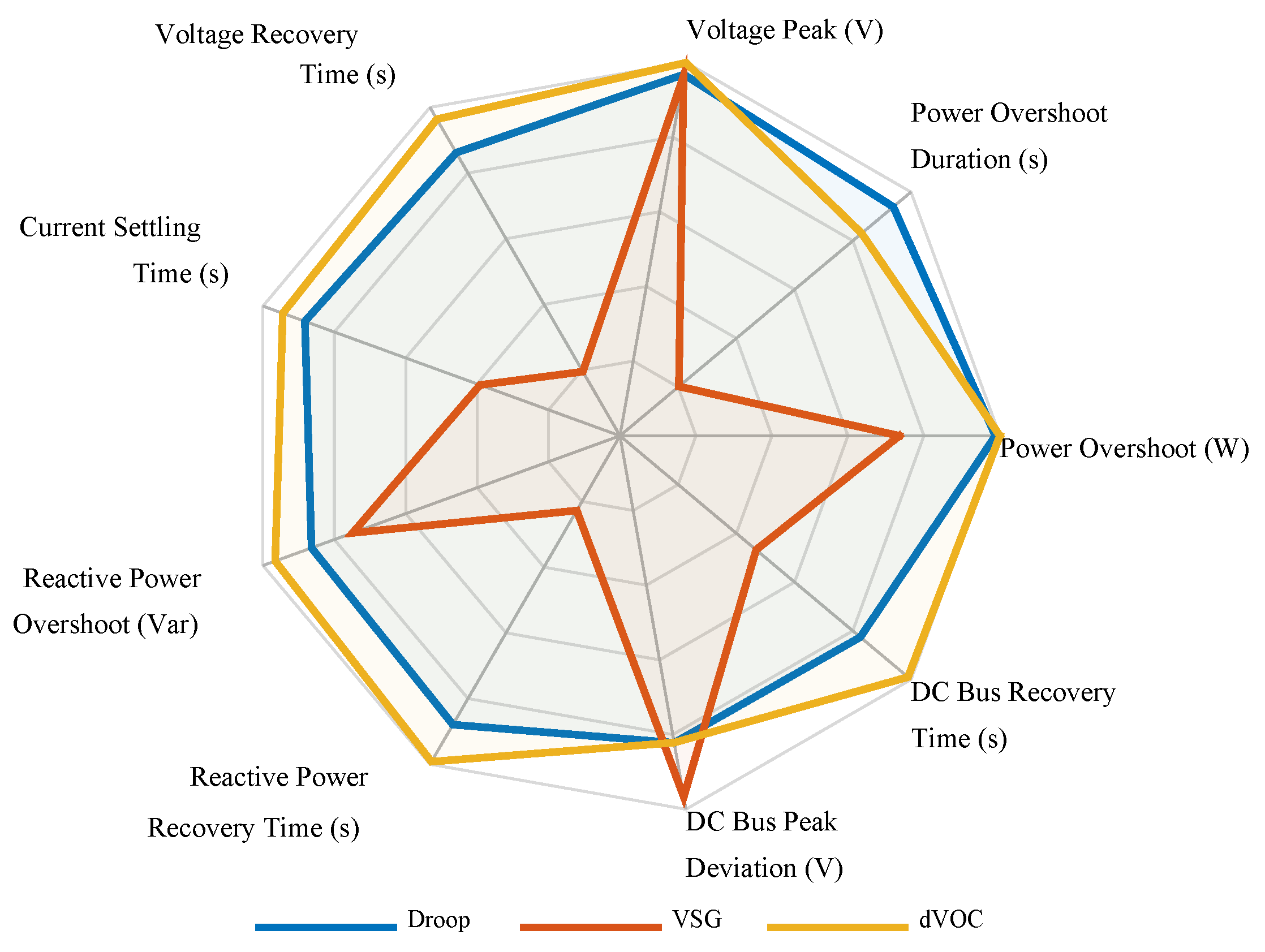

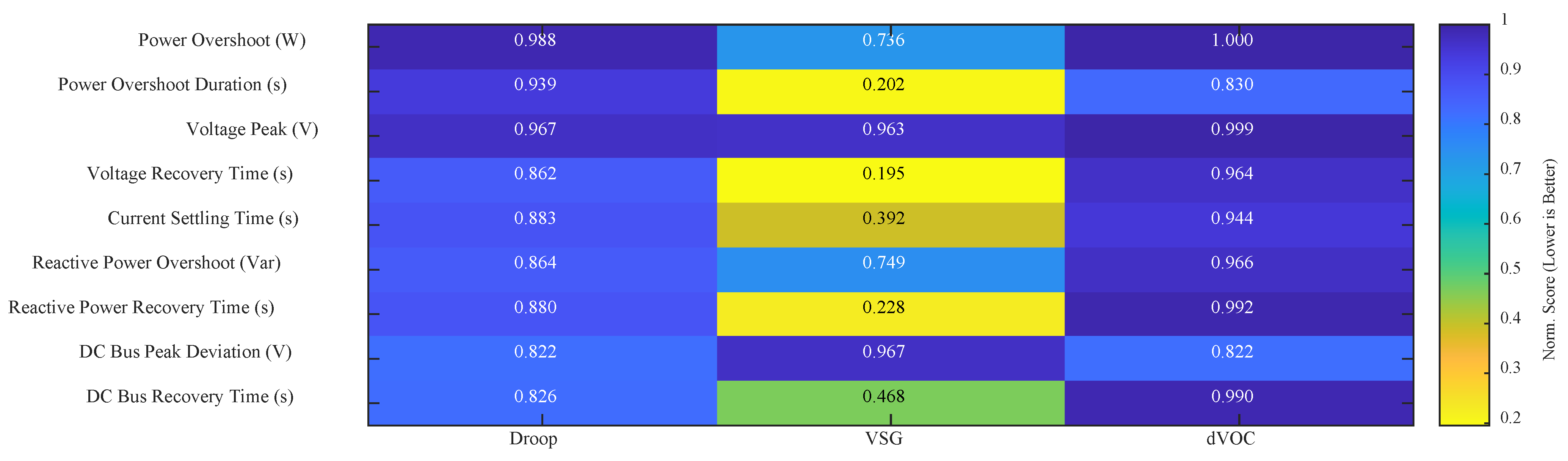

The quantitative analysis in

Table 2 and

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 demonstrates that the VSG controller consistently outperforms Droop and dVOC in dynamic stability and fault ride-through. The superior dynamic performance of the VSG strategy, quantified in

Table 2, can be attributed to the decoupling of transient handling into two distinct physical mechanisms inherent to the swing equation: Virtual Inertia and Virtual Damping.

The Virtual Inertia term (

) functions as an instantaneous energy buffer. During sudden load steps (

Figure 10b) or faults (

Figure 12b), this term physically constrains the rate of change of the voltage phase angle. Unlike Droop control, which relies on algebraic relationships filtered only by a first-order LPF, allowing rapid, often excessive, phase shifts, the VSG inertia forces gradual frequency evolution. This inertial resistance directly correlates with the significantly reduced active power overshoot observed in

Figure 10b (0.548 W) compared to the unbuffered Droop control response (1.273 W).

- 2.

Impact of Virtual Damping on Settling Time:

While inertia manages the initial impact, the Virtual Damping term (

) governs the recovery trajectory. This term introduces active power dissipation proportional to the frequency deviation. In the experimental results, this is evidenced by the rapid settling time (0.63 s) and the absence of prolonged oscillations in the VSG response. In contrast, the Droop and dVOC strategies, which lack this explicit derivative-like damping action, rely on the system’s natural impedance for attenuation, resulting in the extended recovery tails (2.14 s and 1.83 s, respectively) observed in

Figure 10a,c.

It is important to note that this evaluation utilizes linear R-L loads to isolate fundamental transient behavior. While nonlinear loads introduce harmonics typically requiring auxiliary virtual impedance loops, these were excluded to ensure a fair baseline comparison. The selected loads validate the robustness of the VSG’s virtual inertia, which buffers oscillations independent of power factor, contrasting with Droop control’s susceptibility to instability when load impedance characteristics deviate from standard inductive coupling assumptions.

To summarize the comparative performance, the VSG strategy demonstrated superior dynamic characteristics, achieving the fastest settling time and lowest overshoot compared to Droop and dVOC. Specifically, VSG recorded a settling time of 0.63 s with a minimal power overshoot of 0.548 W, whereas Droop and dVOC exhibited significantly slower responses (2.14 s and 1.835 s) and higher overshoots (1.273 W and 1.295 W, respectively). In terms of waveform quality, VSG also minimized harmonic distortion, with a voltage THD of 0.61%, compared to 1.63% for Droop and 0.90% for dVOC. These advantages are visually confirmed by the bar charts in

Figure 13 and the radar chart in

Figure 14, which show that the VSG trace is tightly constrained toward the center for all recovery metrics. Furthermore, the heatmap in

Figure 15 highlights VSG’s superior normalized transient duration scores (~0.2 vs. ~0.9 for others), confirming its suitability for applications requiring high dynamic agility. Given these attributes, the VSG strategy is selected as the primary subject for the subsequent evaluation of cyber-physical resilience. The following section investigates the vulnerability of this high-performance controller to cyber threats and validates a proposed resilience layer designed to protect it against FDI attacks.

4.2. Cyber-Physical Resilience Scenarios

This section presents real-time validation of the proposed cyber–physical microgrid framework, comparing system behavior under nominal conditions with that under several cyberattack scenarios. All experiments were executed on the OPAL-RT real-time simulator, with the communication layer emulated in EXata CPS. The study examines two distinct operating modes:

Open-Loop Operation (Baseline): Reference signals are applied directly to microgrids without feedback-based correction from the hardware controller, representing a vulnerable system state.

Closed-Loop Operation (Resilient): The TI-based VSG controller manages the system using real-time measurement feedback, employing internal consistency checks to validate data integrity.

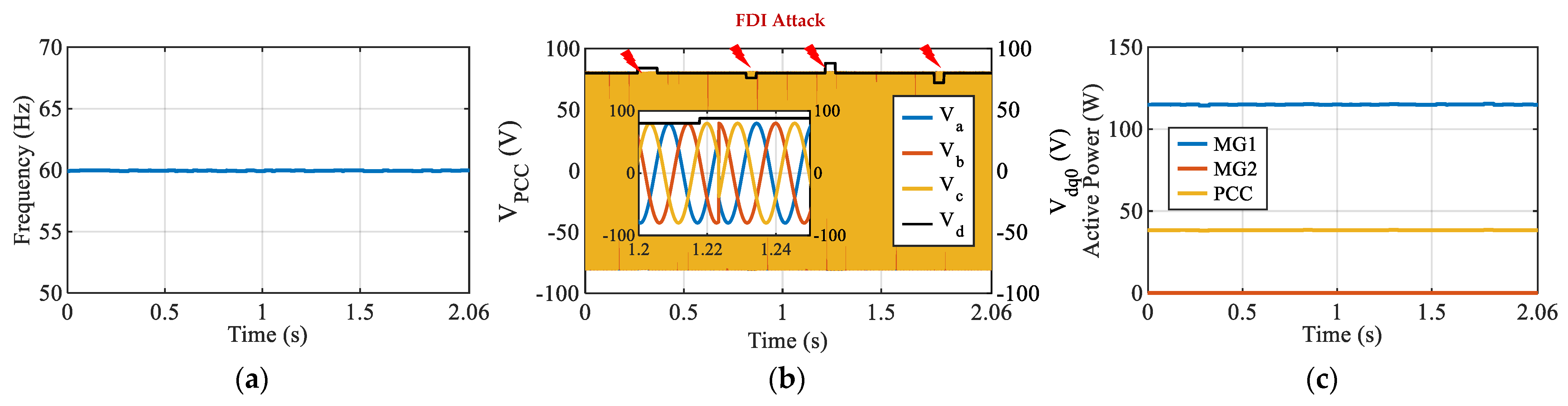

4.2.1. Operation Without TI Control (Open-Loop)

Under baseline operation, both inverter-based microgrids (MG

1 and MG

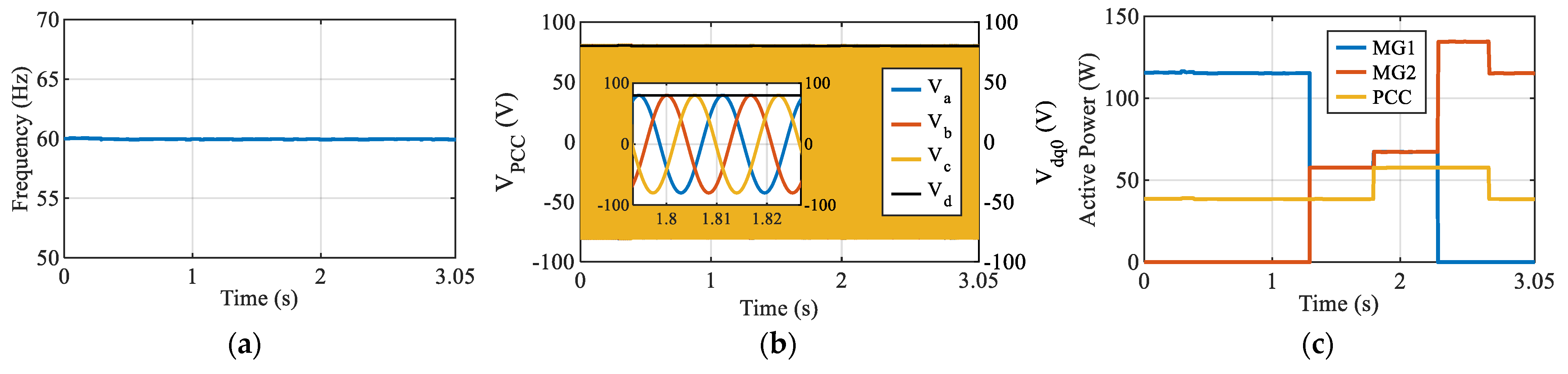

2) supply their individual local loads while jointly supporting the demand at the PCC. As shown in

Figure 16, the system maintains a frequency close to the reference value of 60 Hz, and the PCC voltage (

) is at 80 V. When the shared load varies, each microgrid adjusts its active-power output in proportion to its rating and local control parameters. The coordinated response demonstrates proper load sharing and validates the functionality of the open-loop control architecture under disturbance-free conditions.

- 2.

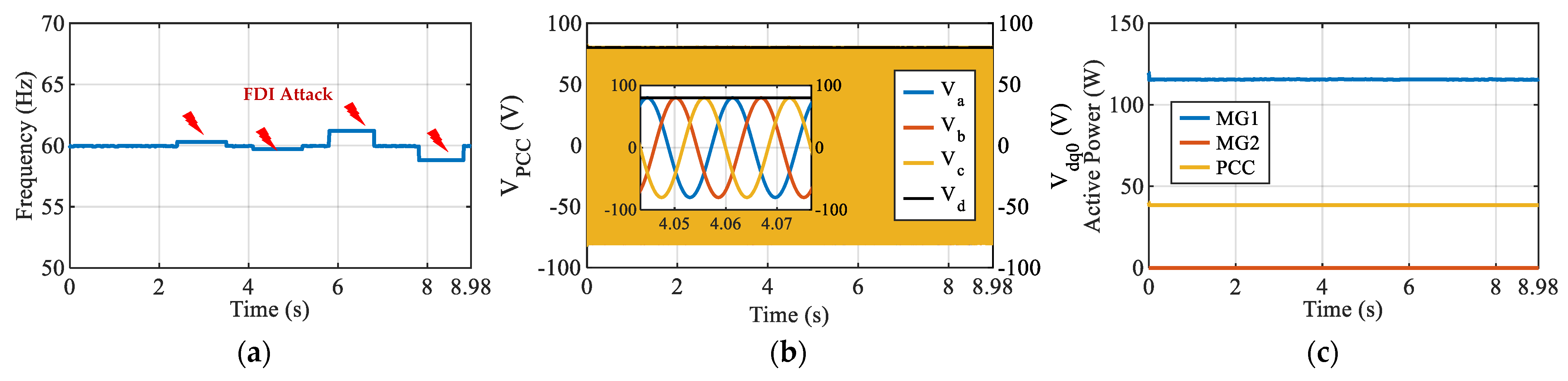

Case 2: Data Modification Attack on the Frequency Reference ()

This scenario assesses the system’s vulnerability to reference tampering. MG2 is disconnected from the PCC, leaving MG1 to bear the entire demand. An attack is introduced by injecting deviations of

and

into the frequency reference (

) sent to MG1. As illustrated in

Figure 17, because the system operates without feedback-based correction, these malicious perturbations directly influence the inverter control loop. An increase in

forces MG1 to increase active power injection, causing a corresponding rise in PCC active power (

), while a decrease reduces injection. The PCC voltage reflects these shifts, confirming that manipulating a single reference signal can propagate through the control layer and manifest as significant physical deviations.

- 3.

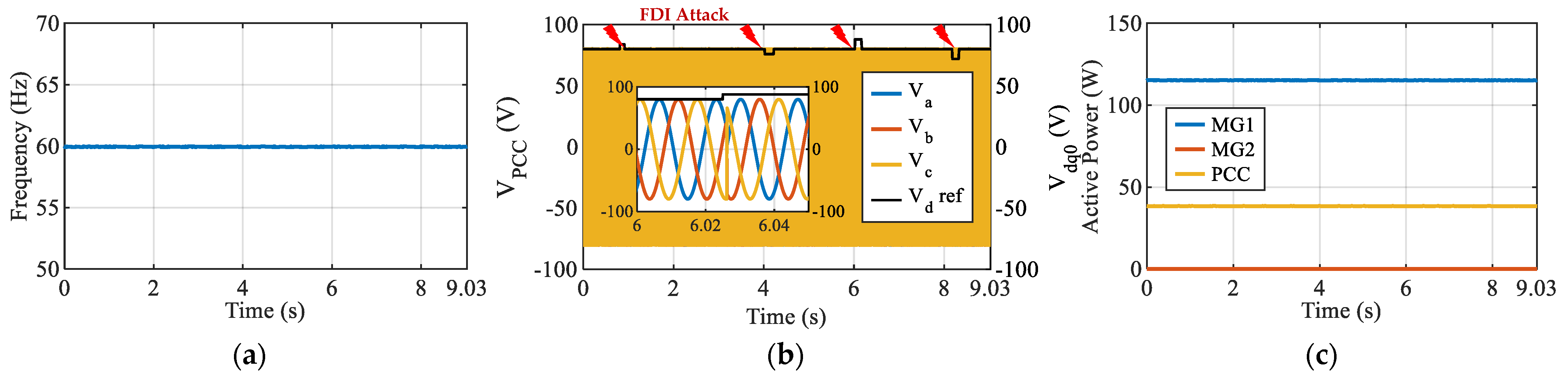

Case 3: Data Modification Attack on Voltage Reference ()

In this attack scenario, MG

1 is responsible for supplying both its local load and the PCC load as in Case 2. The attacker injects an offset into the internal voltage-reference signal (

) governing the VSG’s EMF dynamics. The attack introduces

and

deviations. These specific magnitudes were selected to align with standard microgrid protection guidelines (ANSI C84.1), where protection relays are typically configured to trip when voltage deviations exceed the

threshold. While larger deviations are physically possible during severe faults, the objective of this test is to evaluate the controller’s ability to maintain stability within the continuous operational window, assessing whether the logic can mitigate the attack before protection mechanisms are forced to disconnect the unit. As shown in

Figure 18, these changes distort the PCC voltage profile, demonstrating the system’s vulnerability to reference-level tampering. Because no corrective feedback is available, the open-loop controller responds directly to the falsified signal, leading to noticeable deviations in

. This scenario highlights how voltage-based attacks can compromise system regulation even without directly altering load or frequency references.

4.2.2. Operation with TI Control (Closed-Loop/VSG)

The baseline scenario is repeated with the TI C2000 controller executing the VSG algorithm in real-time. In this closed-loop mode, the hardware controller continuously receives power, voltage, and current measurements from OPAL-RT and dynamically adjusts the reference commands. As shown in

Figure 19, the system’s behavior closely mirrors the nominal open-loop results: active power sharing remains balanced,

stays regulated, and frequency holds at 60 Hz. This confirms that integrating the hardware-level VSG control preserves nominal operation while enabling the enhanced responsiveness required for resilience.

- 2.

Case 2: Resilience to Frequency Reference Attack ()

The frequency reference attack from case 2 in

Section 4.2.1 is re-evaluated with the TI VSG controller active. Unlike in the open-loop case, the proposed resilience layer detects inconsistencies between incoming references and real-time feedback measurements. As illustrated in

Figure 20, the VSG algorithm identifies the falsified input and counteracts it by maintaining its internal control loop integrity. The result is almost no observable deviation in either

or

, demonstrating the CHIL system’s capability to reject control-layer tampering.

- 3.

Case 3: Resilience to Voltage Reference Attack ()

In this scenario, an offset-based manipulation is applied to the internal voltage reference (

) governing the VSG dynamics of MG

1. The attack introduces deliberate deviations of

and

from the nominal reference value, as illustrated in

Figure 18b. Under open-loop operation (Case 3 from

Section 4.2.1), such deviations directly distorted the PCC voltage and power due to the absence of corrective feedback. However, with the TI-based VSG controller active, the closed-loop architecture behaves markedly differently. The controller continuously compares the received voltage reference against the expected nominal value of 80 V. When the falsified

arrives, the VSG logic identifies the inconsistency and prevents the corrupted signal from propagating downstream. Instead of forwarding the manipulated voltage reference to the inverter, the controller overrides the malicious input and injects a corrected reference consistent with the nominal operating point. As shown in

Figure 21, both

and

remain stable and unaffected by the attack. This behavior demonstrates the VSG controller’s capacity to detect abnormal deviations in internal control commands and mitigate their effects before they influence system dynamics.

- 4.

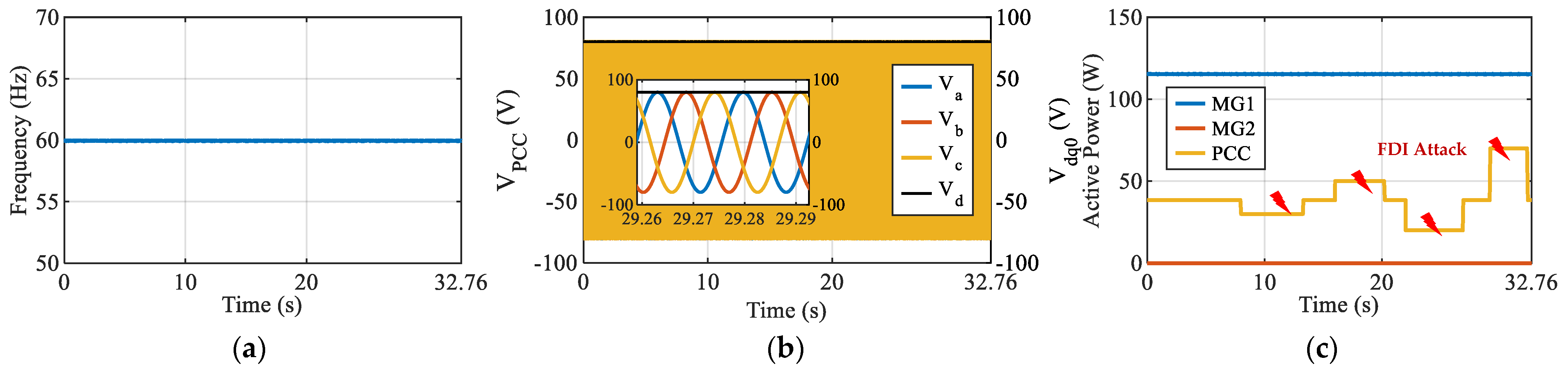

Case 4: Resilience to Power Measurement Attack ()

This scenario targets the measurement channel rather than the control references. The attacker introduces false step changes into the

feedback signal, including fabricated jumps of 30 W, 50 W, 20 W, and 70 W, as shown in

Figure 22. Although the actual physical load remains constant, the VSG receives corrupted measurement data. Instead of reacting blindly to these falsified changes, the hardware controller applies internal consistency checks via the VSG dynamics. The outputs of MG

1 remain essentially unchanged, demonstrating that the controller successfully prevents unintended adjustments caused by compromised measurements. This scenario underscores the resilience of the CHIL-enabled microgrid, showing that the hardware controller can maintain stability even when measurement integrity is threatened.

- 5.

Case 5: Resilience to PCC Voltage Measurement Attack ()

In this scenario, the attacker targets the PCC voltage measurement (

) by injecting

and

deviations in highlight the resilience of the CHIL-enabled microgrid, demonstrating that the hardware controller can maintain stability even when measurement integrity is compromised in the measured d-axis voltage component, mimicking abnormal sensor readings, as shown in

Figure 23. In a non-resilient system, this would induce inappropriate corrective actions. However, the hardware VSG controller evaluates the incoming measurement against expected operating conditions and detects the inconsistency with the system’s nominal 80 V state. The controller isolates the corrupted measurement and substitutes a corrected estimate. Consequently,

and

remain steady, as the inverter does not respond to the falsified measurement. The plots in

Figure 23 confirm that the microgrids’ output values remain unchanged despite the manipulated feedback, demonstrating the controller’s robustness to measurement-based data attacks.