A Comprehensive Review of Reliability Analysis for Pulsed Power Supplies

Abstract

1. Introduction

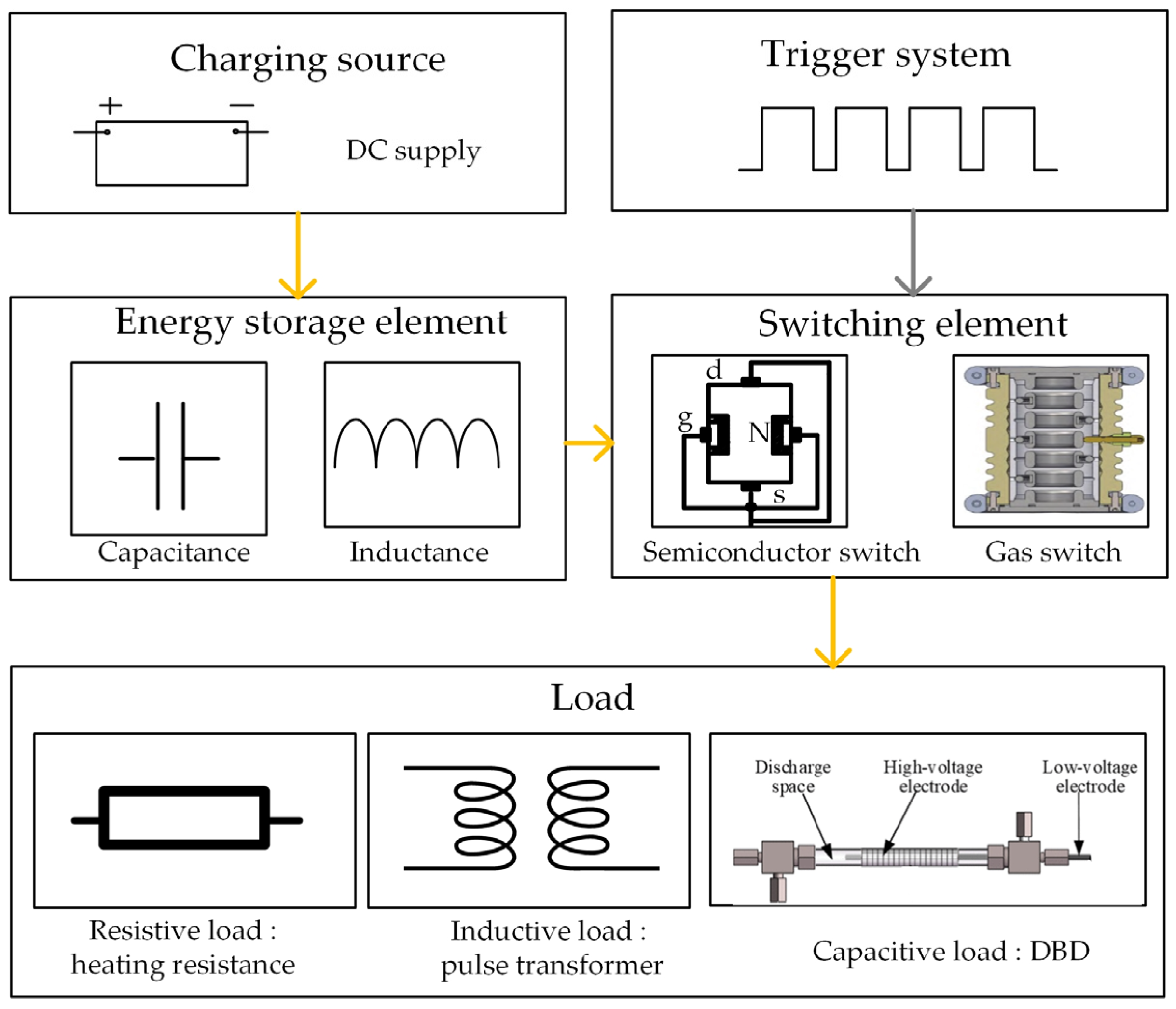

2. Component Reliability

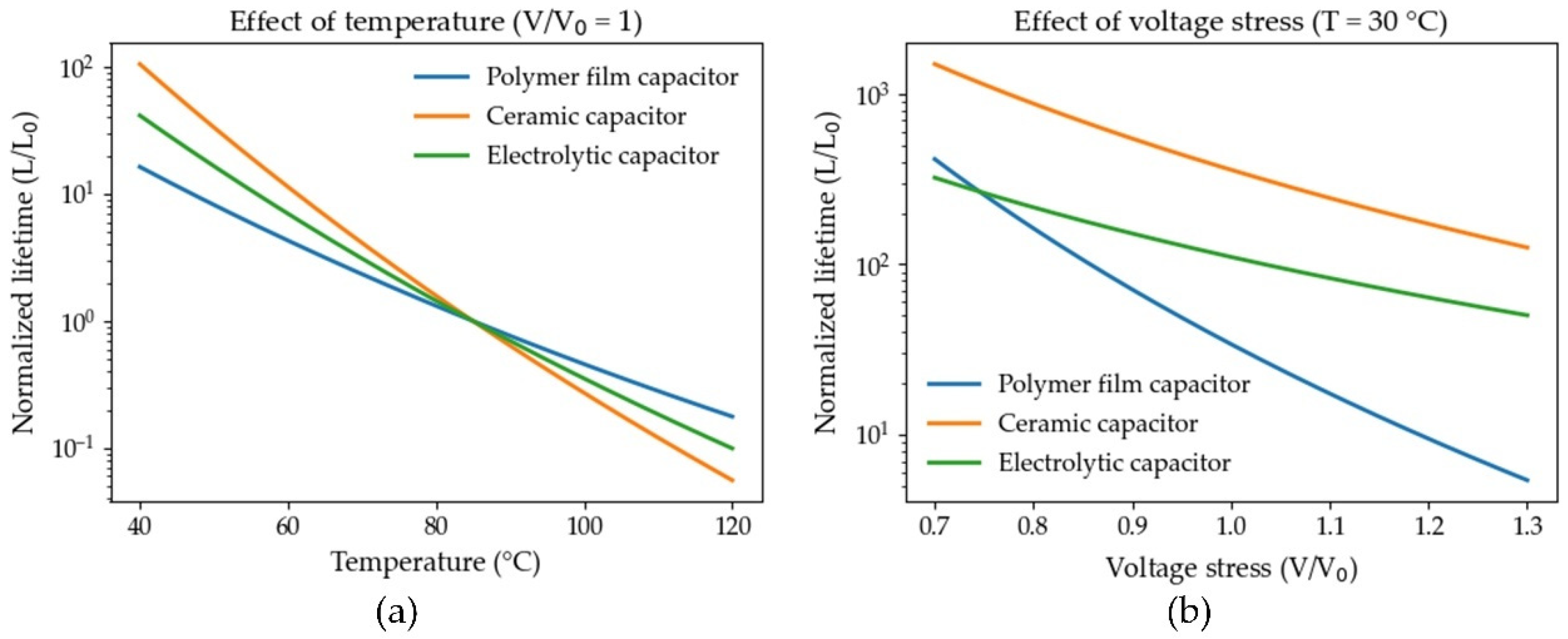

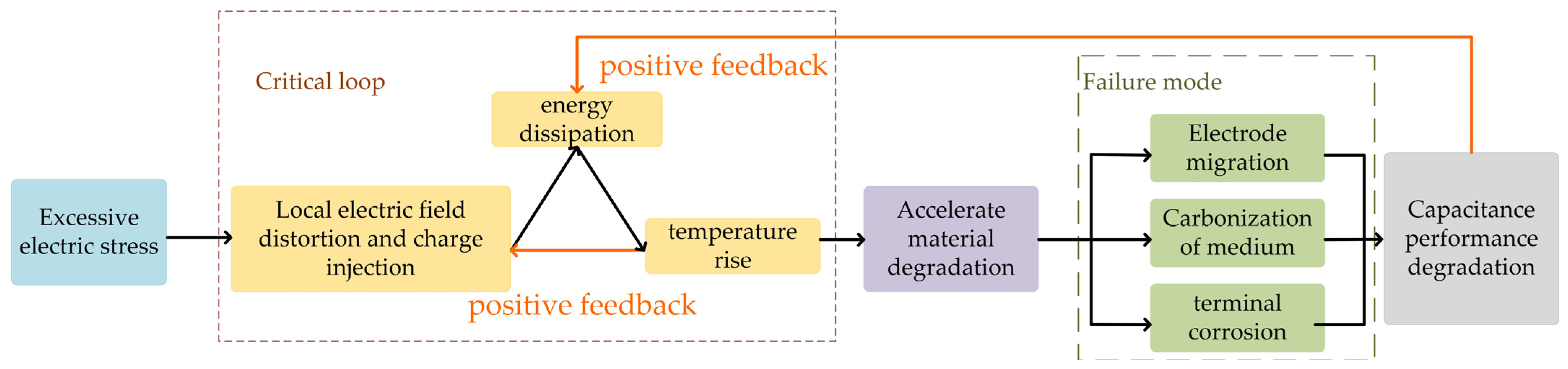

2.1. Energy Storage Elements

2.1.1. Capacitive Storage

2.1.2. Inductive Storage

2.1.3. Flywheel Energy Storage

2.2. Switching Elements

2.2.1. Gas Spark Gap Switch

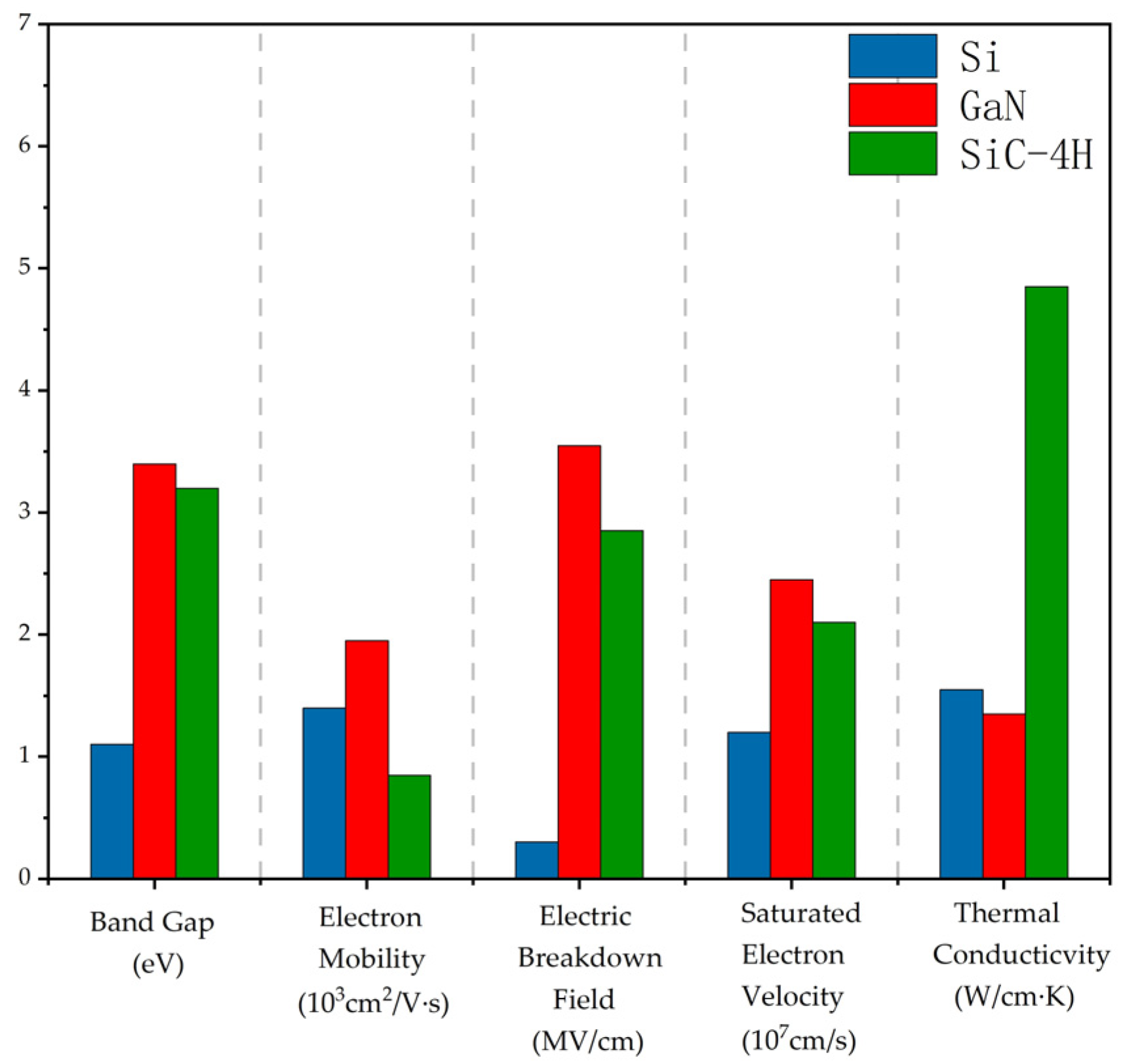

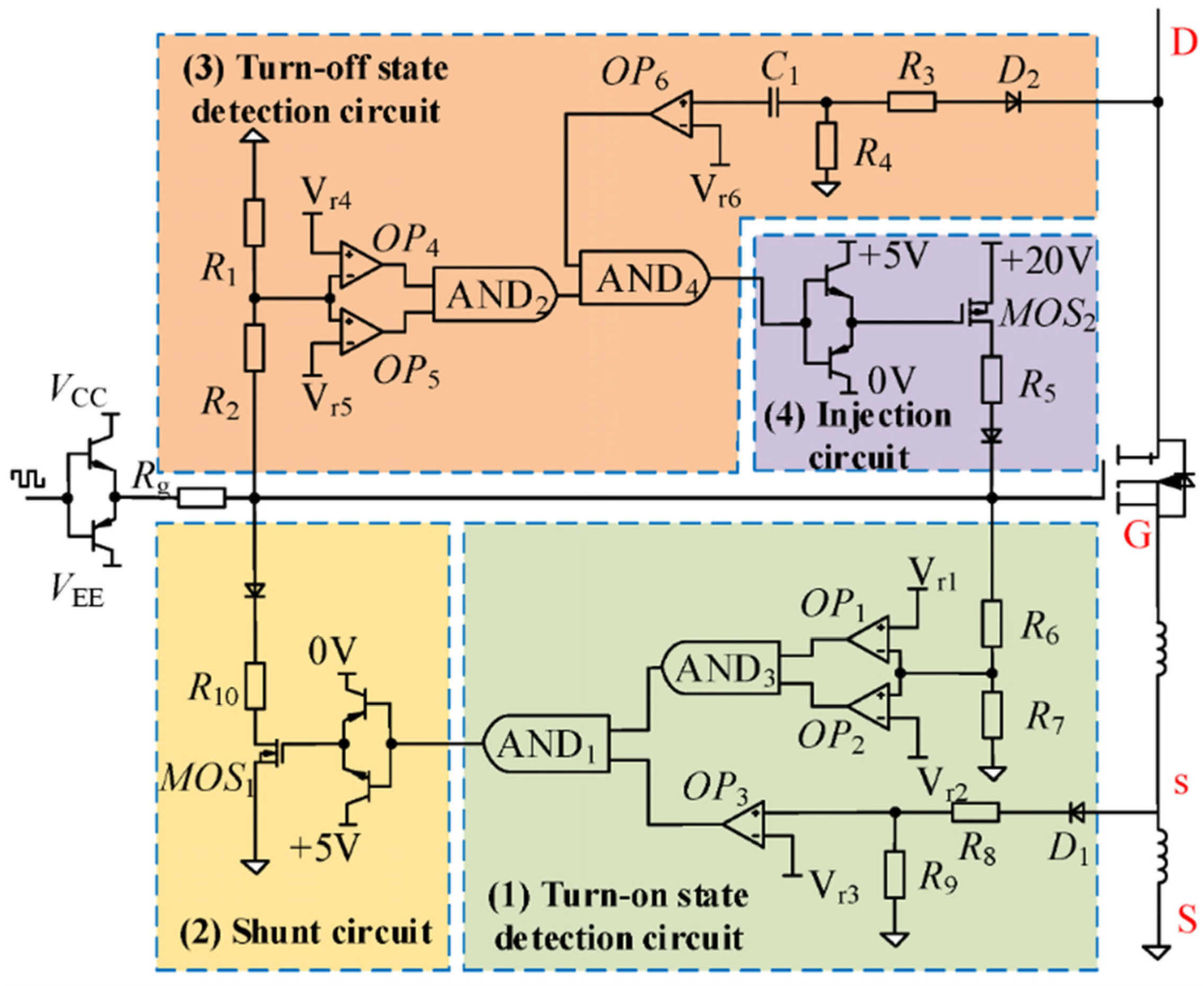

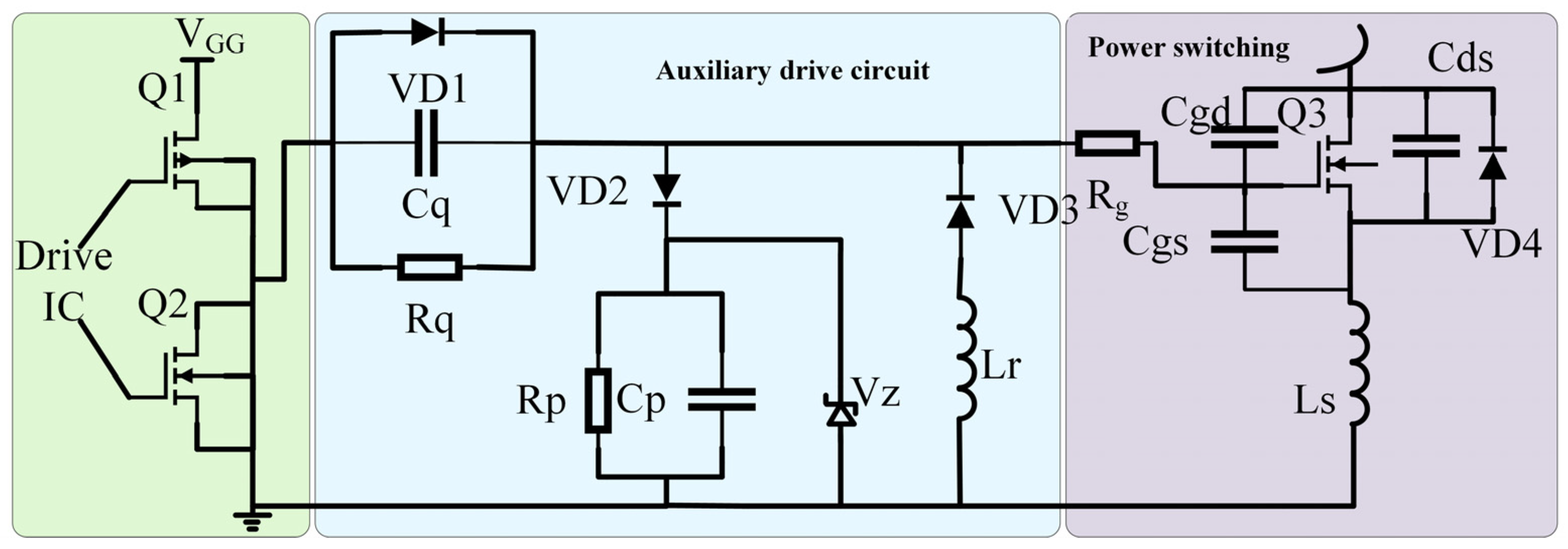

2.2.2. Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Switch

2.2.3. Photoconductive Switch

2.3. Impact of Component Reliability on System Performance

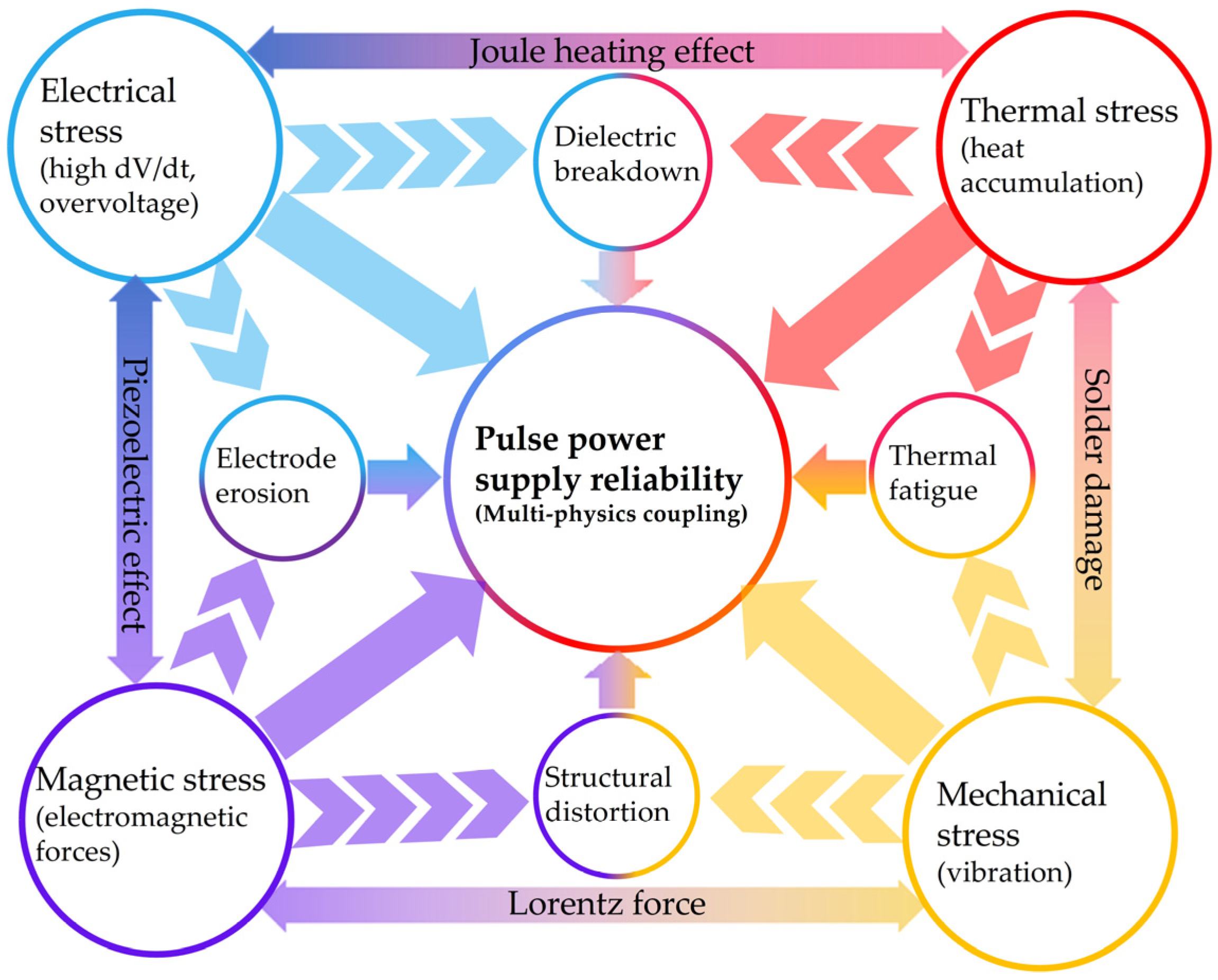

3. System Integration Reliability

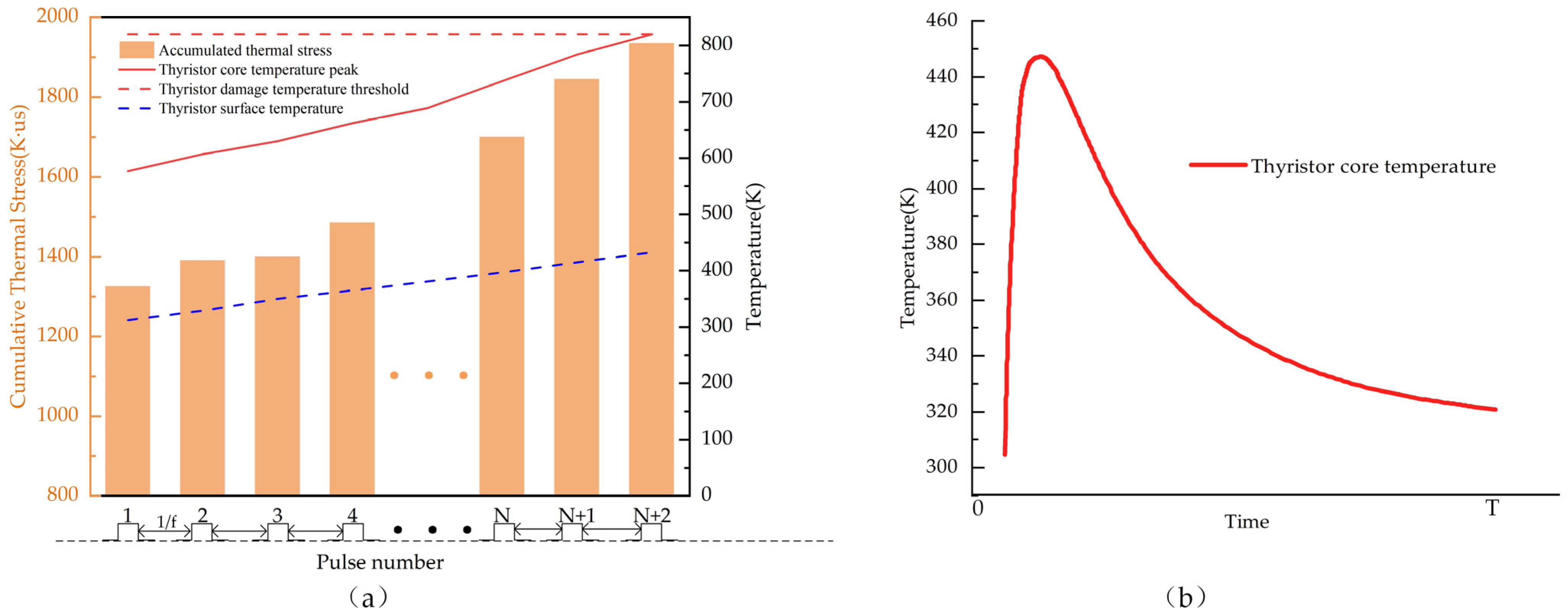

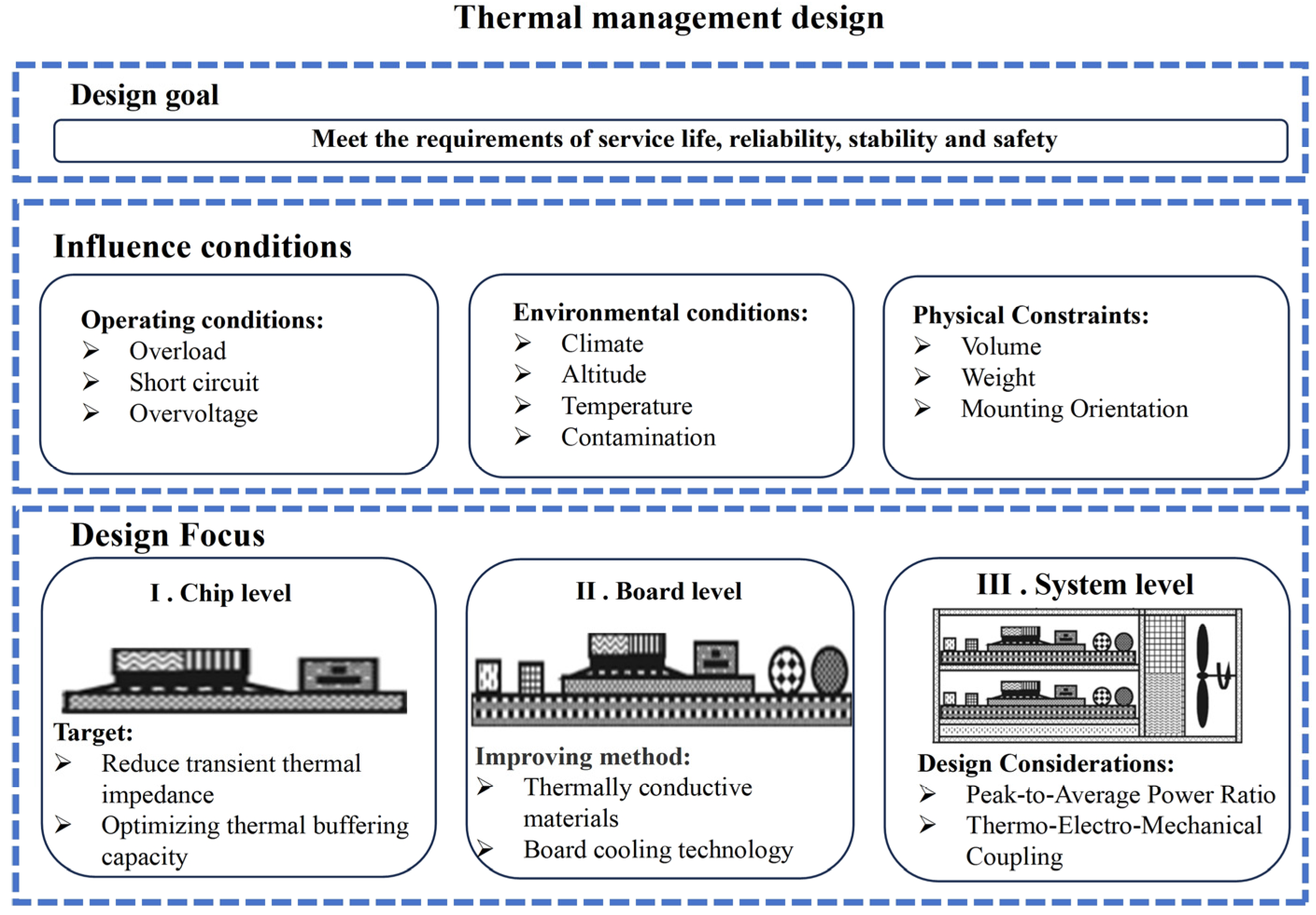

3.1. System-Level Thermal Management

3.2. Multi-Module Synchronous Triggering

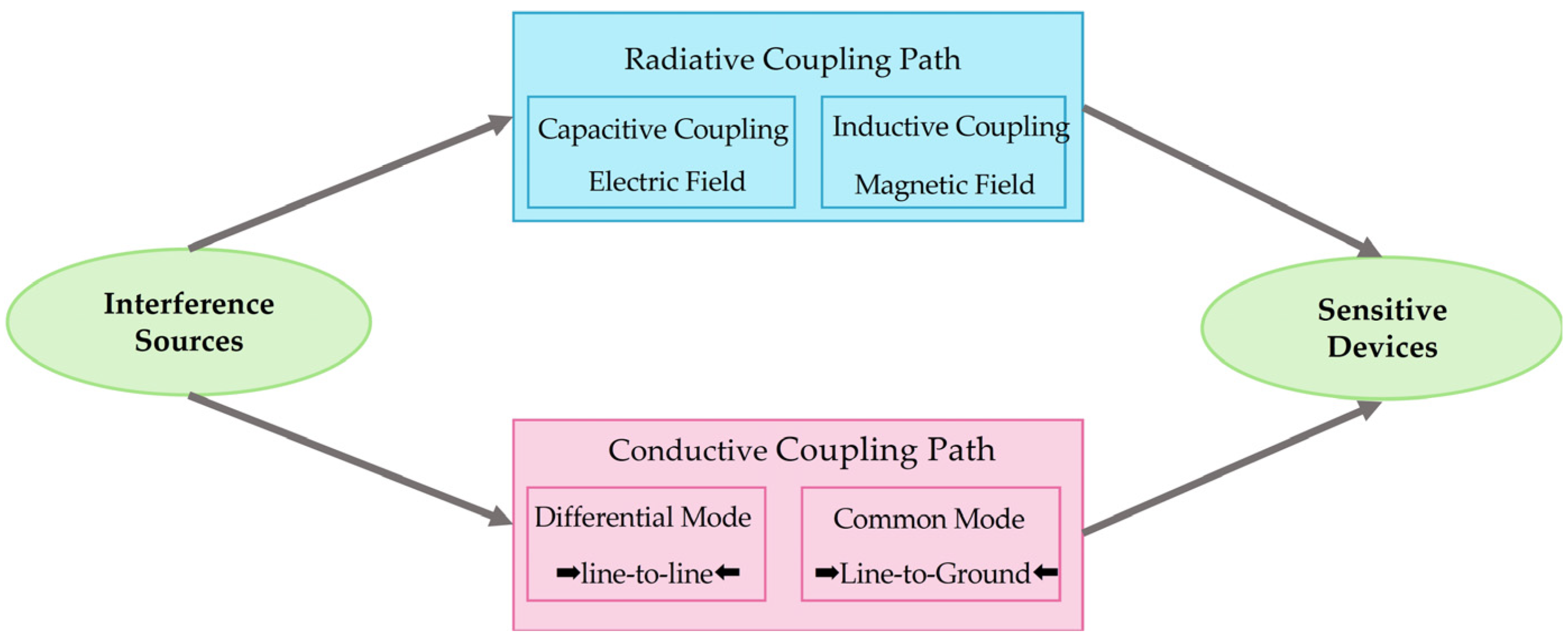

3.3. Electromagnetic Interference

3.4. Reliability Characteristics of Typical Topologies

3.5. Synergistic Impact of System Integration on Reliability

4. Reliability Issues and Solutions in Extreme Environments

4.1. Aerospace

4.2. Navigation

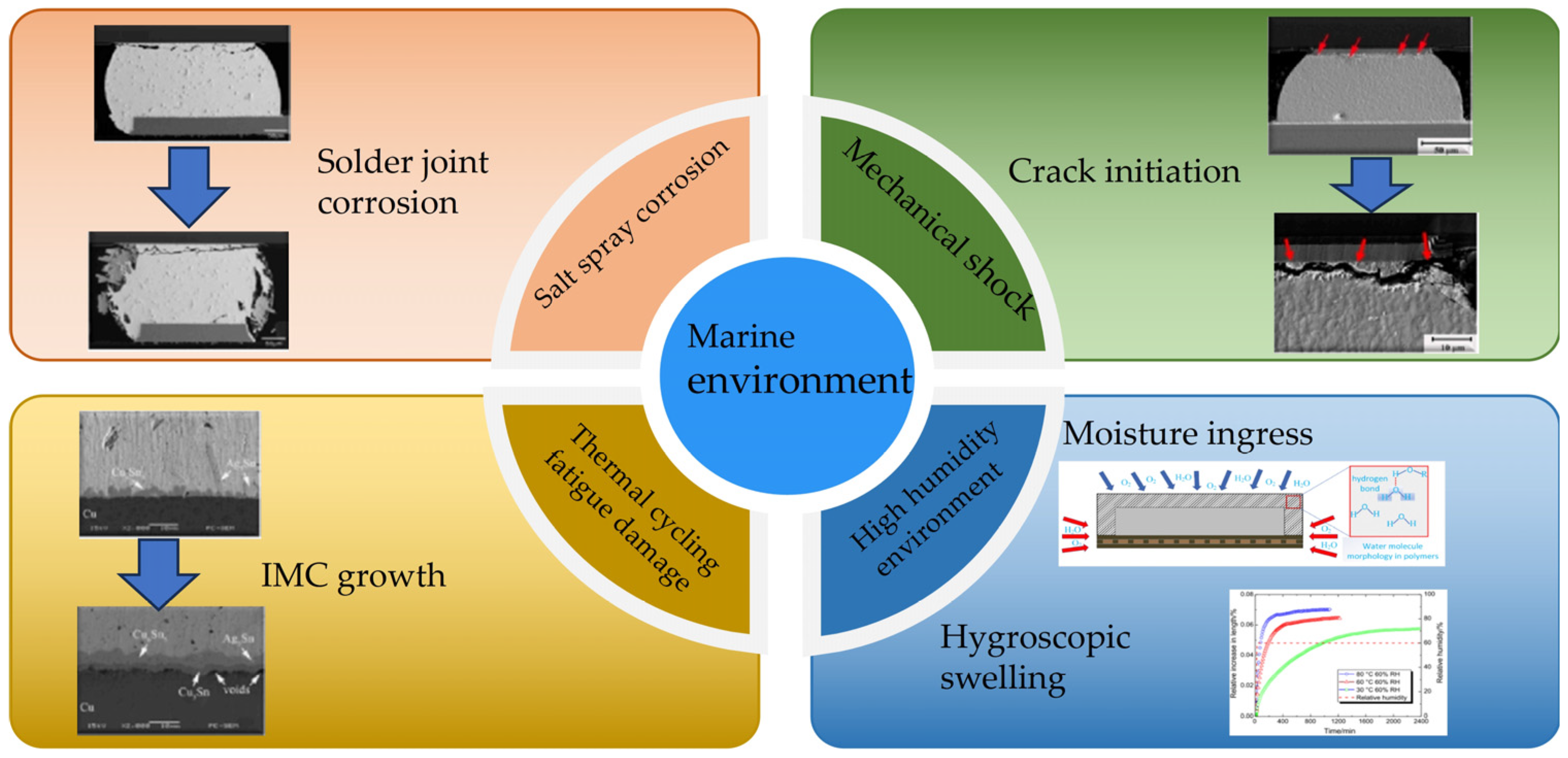

4.3. Geological Exploration and Resource Exploration

4.4. Comparative Analysis and Mitigation Strategies

5. Conclusions and Prospects

- Current research predominantly focuses on failure analysis of individual components or interactions within limited physical fields. There is a notable lack of investigation into the performance interaction and degradation correlation among multiple components under coupled electrical–thermal–magnetic–mechanical stresses. Consequently, a widely accepted system-level prediction model capable of describing the cross-component propagation and evolution of failures has yet to be established.

- Current reliability verification experiments are predominantly conducted under standardized or idealized conditions. They fail to adequately replicate the dynamic coupling of electrical–thermal–magnetic–mechanical stresses and environmental factors inherent in real-world applications. Consequently, there is a significant discrepancy between laboratory data and actual field performance.

- Current condition monitoring technologies are primarily focused on reactive fault detection and alarming. There is a distinct lack of comprehensive capabilities for real-time health assessment and prognostic prediction.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, J.C. Nanosecond pulse techniques. Proc. IEEE 1992, 80, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Hu, H.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Peng, T. Design of pulsed power supply for repetitive pulsed high magnetic field for water electrolysis. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2021, 92, 114708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Gui, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Design of Pulsed Power Supply for Electromagnetic Launch. High Volt. Eng. 2007, 33, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Novac, B.; Istenic, M.; Luo, J.; Smith, I.; Brown, J.; Hubbard, M.; Appelgren, P.; Elfsberg, M.; Hurtig, T.; Möller, C.; et al. A 10-GW pulsed power supply for HPM sources. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2006, 34, 1814–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Wang, S.H.; Sun, F.J.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, N.M. Transient Electromagnetic Field Analysis for the Single-Stage Fast Linear Transformer Driver with Two Different Configurations Using the Finite-Element Method and Finite Integration Technique. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2020, 56, 7515805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, S.; Talukdar, N.; Neog, N.K.; Borthakur, T.K.; Kumar, R.; Verma, R.; Shyam, A. 200 kJ Pulsed Power System for Pulsed Plasma Device. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2017, 45, 1769–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-R.; Ryoo, H.-J.; Ok, S.-B. Pulsed-Power System for Leachate Treatment Applications. J. Power Electron. 2011, 11, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.Y.; Wu, T.F.; Wu, M.W. Bipolar narrow-pulse generator with energy-recovery feature for liquid-food sterilization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyo, W.; Yang, R.; Zhao, W. Effects of combined pulsed electric fields and mild temperature pasteurization on microbial inactivation and physicochemical properties of cloudy red apple juice (Malus pumila Niedzwetzkyana (Dieck)). J. Food Saf. 2017, 37, e12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, L.; Silva, E. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction techniques for obtaining vegetable oils and essential oils: Recent progress and opportunities for the food industry. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golberg, A.; Yarmush, M. Nonthermal Irreversible Electroporation: Fundamentals, Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 60, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Davalos, R.; Bischof, J. A Review of Basic to Clinical Studies of Irreversible Electroporation Therapy. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, F.; Wei, H.; Lou, C.; Qiu, A. Discharge characteristics of trigger brick gas switches for 12-stage linear transformer driver. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2024, 36, 115001. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Lian, H. A High Frequency Bipolar Nanosecond Pulse Generator with High Voltage Gain Based on Inductive Discharge for DBD Application. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 17998–18010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, P.P.; Jency, J.G.; Babu, M.; Kumar, K.; Nirmal, D. Fabrication of ultra flexible super capacitor using polyvinylidene fluoride. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Innovations in Electrical, Electronics, Instrumentation and Media Technology (ICEEIMT), Coimbatore, India, 3–4 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Sun, X.; Yan, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Ma, Y. Review of Energy Storage Capacitor Technology. Batteries 2024, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, F.; Du, G.; Pan, L.; Wang, K.; Gerhard, R.; Plath, R.; Rozga, P.; Trnka, P. Revisiting the thermal ageing on the metallised polypropylene film capacitor: From device to dielectric film. High Volt. 2023, 8, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Cong, P.; Zhang, T.; Zhong, X.; Luo, W. Prediction and experimental verification of erosion resistance of gas switch electrode materials. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 055206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liu, W.; Liu, K. Summary of research on control technology of pulsed power supply in electromagnetic launch system. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference of China Electrotechnical Society: Volume II, Beijing, China, 24–26 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bluhm, H. Pulsed Power Systems: Principles and Applications, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 7–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aghmadi, A.; Mohammed, O. Energy Storage Systems: Technologies and High-Power Applications. Batteries 2024, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, J.; Dong, Z.; Ren, J.; Jia, W.; Guo, F.; Xie, L.; Wu, W.; Yao, X. Failure behavior of dielectric films for peaking capacitor subjected to surface flashover under nanosecond pulses. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 125203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Wan, Q.; Yang, R.; Xiao, H.; Ding, H.; Li, L. A Dual-Capacitors Type Energy Recovery Power System for Repetitive Pulsed High Magnetic Fields. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2013, 170, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, D.-Q.; Shen, W.-Z.; Yan, H.-B.; Mao, L.-J. Reliability of DC-link capacitor in pulsed power supply for accelerator magnet. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2024, 35, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolobov, V.; Barannik, M.; Selivanov, V.; Kuklin, D. A current source with an inductive energy storage for measuring pulse impedances of grounding connections. Instrum. Exp. Tech. 2014, 57, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebfried, O. Review of Inductive Pulsed Power Generators for Railguns. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2017, 45, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.; Sugai, T.; Jiang, W.; Tokuchi, A.; Horie, M.; Ohshio, Y.; Ueno, K. High current pulse forming network switched by static induction thyristor. Matter Radiat. Extremes 2018, 3, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, S.; Lukic, S.M.; Galvan, E.; Franquelo, L.G.; Carrasco, J.M. Energy Storage Systems for Transport and Grid Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 57, 3881–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, J.; Funamoto, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Arai, R. Energy characteristics of a fixed-speed flywheel energy storage system with direct grid-connection. Energy 2018, 165, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, G.S.M.; Faraji, F.; Majazi, A.; Al-Haddad, K. A comprehensive review of Flywheel Energy Storage System technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, L.; Yuan, J.; Xie, W.; Deng, M.; Kong, Y. Electrical and thermal aging analysis of all-film pulsed capacitor. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2024, 36, 025020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Blaabjerg, F. Reliability of Capacitors for DC-Link Applications in Power Electronic Converters-An Overview. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2014, 50, 3569–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Heo, J.; Lee, K.; Ye, B.U.; Kang, B.S.; Yoon, S.-H. Thermal activation energy on electrical degradation process in BaTiO3 based multilayer ceramic capacitors for lifetime reliability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Chen, C.; Feng, R.; Liu, S.; Zhai, G. Reliability assessment of film capacitors oriented by dependent and nonlinear degradation considering three-source uncertainties. Microelectron. Reliab. 2021, 126, 114277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Dou, Z.; Chen, L. Lifetime prediction and reliability analysis for aluminum electrolytic capacitors in EV charging module based on mission profiles. Front. Electron. 2023, 4, 1226006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umran, H.; Wang, F.; He, Y. Ageing: Causes and Effects on the Reliability of Polypropylene Film Used for HVDC Capacitor. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 40413–40430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortai, J.; Bonifaci, N.; Denat, A.; Trassy, C. Diagnostic of the self-healing of metallized polypropylene film by modeling of the broadening emission lines of aluminum emitted by plasma discharge. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 053304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Yadav, O.; DeVoto, D.; Major, J. A review of degradation behavior and modeling of capacitors. In Proceedings of the ASME International Technical Conference and Exhibition on Packaging and Integration of Electronic and Photonic Microsystems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27–30 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.S.; Kim, D.C.; Shin, H.S.; Yeo, D.H.; Lee, J.H. Effect of oxygen vacancies on dielectric property and reliability of anti-ferroelectric PLZT applicable to EV-MLCC. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2024, 47, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laadjal, K.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Multilayer Ceramic Capacitors: An Overview of Failure Mechanisms, Perspectives, and Challenges. Electronics 2023, 12, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Ma, R.; Yuan, S. Transient failure mode of (Ba,Ca)(Ti,Zr)O3 pulsed power capacitor based on electromechanical coupling mechanism. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 7654–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.; Ciufo, P.; Elphick, S.; Robinson, D. Preliminary Evaluation of the Impact of Sustained Overvoltage on Low Voltage Electronics-Based Equipment. Energies 2022, 15, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Chai, M.; Yu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Chen, J.; Xiao, B.; Long, L. Method for monitoring ESR and capacitance based on discharge rule of aluminum electrolytic capacitors. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2020, 40, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Xi, R.; Zhou, C.; He, G.; Yang, F.; Xu, L.; Li, H. Polymer Capacitor Films with Nanoscale Coatings for Dielectric Energy Storage: A Review. Coatings 2024, 14, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.Q.; Wu, X. A case study of high-temperature polyetherimide film capacitor fabrication. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 30, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Wang, Y.; Men, R.; Lei, Z.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, M. High-energy-density polymer dielectrics via compositional and structural tailoring for electrical energy storage. Iscience 2022, 25, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, G.; Jiao, Y.; Feng, L.; Meng, Q.; Yang, N.; Zhu, S.; Lu, M.; Wong, C.-P. High energy density of BaTiO3@ TiO2 nanosheet/polymer composites via ping-pong-like electron area scattering and interface engineering. NPG Asia Mater. 2022, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Zhen, Y.; Cao, X.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Enhanced electrical reliability of Zr-doped BaTiO3 nanoceramics: First-principle calculations and experimental studies. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 108, e20273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Liu, R.; Shen, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Nan, C. Texture Engineering Modulating Electromechanical Breakdown in Multilayer Ceramic Capacitors. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaa, A.; Alhammadi, A.; Lethesh, K.; Susantyoko, R.; Bamgbopa, M. Ionic liquid electrolyte selection for high voltage supercapacitors in high-temperature applications. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1349864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Santiago, A.; Judez, X.; Garbayo, I.; Clemente, J.; Morant-Miñana, M.; Villaverde, A.; González-Marcos, J.; Zhang, H.; Armand, M.; et al. Safe, Flexible, and High-Performing Gel-Polymer Electrolyte for Rechargeable Lithium Metal Batteries. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 8812–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Chi, Q.; Lei, Q. Recent Advances in Multilayer-Structure Dielectrics for Energy Storage Application. Adv. Sci 2021, 8, 2102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, F.; Ennis, J.; Yang, X.; Cooper, R.; Gilbert, J.; Bates, J.; Naruo, C.; Schneider, M.; Keller, N.; Joshi, S.; et al. High energy density capacitors for pulsed power applications. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Pulsed Power Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 28 June–2 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hunstig, M.; Schaermann, W.; Broekelmann, M.; Holtkaemper, S.; Siepe, D.; Hesse, H.J. Smart Ultrasonic Welding in Power Electronics Packaging. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Integrated Power Electronics Systems, Berlin, Germany, 24–26 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Cao, F.; Chen, X.; Lin, Z.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yan, S.; Wang, G. Investigation on Discharge Behavior of Antiferroelectric Multilayer Ceramic Capacitors. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2023, 30, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Nie, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Wu, D.; Yang, Z.; Chao, X. A new family of high temperature stability and ultra-fast charge-discharge KNN-based lead-free ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 9992–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Qiu, T.; Lin, F.; Wang, Y. Reliability criterion of film capacitor based on moisture diffusion in encapsulation. High Volt. 2023, 8, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, F. Modeling of ESR in metallized film capacitors and its implication on pulse handling capability. Microelectron. Reliab. 2015, 55, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhang, X. A High-Resolution Analytical Thermal Modeling Method of Capacitor Bank Considering Thermal Coupling and Different Cooling Modes. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 7674–7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.A.; Fathollahi, A.; Akbari, E.; Saki, M.; Khorgami, E.; Teimouri, A.R.; Chronopoulos, A.T.; Mosavi, A. Reliability Calculation Improvement of Electrolytic Capacitor Banks Used in Energy Storage Applications Based on Internal Capacitor Faults and Degradation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 13146–13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, X. Identification of electrical breakdown faults in shunt capacitor bank elements using instantaneous negative sequence current. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 170, 110962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourizadeh, H.; Hosseinpour, M.; Seifi, A.; Shahparasti, M. A 13-level switched-capacitor-based multilevel inverter with reduced components and inrush current limitation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Barzegarkhoo, R.; Siwakoti, Y.; Khan, S.; Li, L.; Blaabjerg, F. A new switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with soft start and quasi resonant charging capabilities. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 135, 107412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Hassanifar, M.; Votava, M.; Sangwongwanich, A.; Sahoo, S.; Langwasser, M.; Liserre, M.; Blaabjerg, F. Monolithic Data-Driven Condition Monitoring Strategy for MMC Considering C and ESR. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 11339–11354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, H. A remaining useful life prediction method of aluminum electrolytic capacitor based on wiener process and similarity measurement. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 142, 114928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, H.; Yang, D.; Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, S. Residual Magnetism Elimination Method for Large Power Transformers Based on Energy Storage Oscillation. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery 2025, 40, 2759–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Ivanov, E.; Pronikov, A.; Kutsaev, S. High-Voltage Pulsed Power Generator for Beam Injection Systems. Electronics 2025, 14, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, R.B.; Froula, D.H.; Brent, G.; Campbell, E.M.; Reisman, D.B.; Savage, M.E.; Shoup, M.J., III; Stygar, W.A.; Wisher, M.L. Conceptual design of a 15-TW pulsed-power accelerator for high-energy-density-physics experiments. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 2017, 2, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Jeyan, J.V.M.L.; Agarwal, A. Numerical analysis on 10 MJ solenoidal high temperature superconducting magnetic energy storage system to evaluate magnetic flux and Lorentz force distribution. Phys. C-Supercond. 2019, 558, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, G.; Yang, D.; Xu, G.; Xing, Y.; Yao, C.; Abu-Siada, A. Enhanced detection of power transformer winding faults through 3D FRA signatures and image processing techniques. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 242, 111433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Deng, Z.; Ding, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. New advances in solid-state pulse generator based on magnetic switches. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2022, 93, 051501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, T.; Kanesawa, K.; Yamazaki, N.; Mukaigawa, S.; Takaki, K.; Fujiwara, T. Energy efficiency of inductive energy storage system pulsed power generator using fast recovery diode. IEEJ Trans. Fundam. Mater. 2009, 129, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Guo, Y.; Lei, G.; Zhu, J. A Review of Flywheel Energy Storage System Technologies. Energies 2023, 16, 6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Liu, K. Pulse shaping method for compulsator. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2018, 30, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, K.; Zhu, B.; Feng, J.; Ao, P.; Zhang, Z. Analytical Investigation and Scaled Prototype Tests of a Novel Permanent Magnet Compulsator. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 8203309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hao, X. Present status and development trend of pulsed power supplies for railguns. Adv. Technol. Electr. Eng. Energy 2022, 41, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Dai, X.; Xie, B.; Li, W.; Yu, H.; Chen, H. Fatigue Life of Flywheel Energy Storage Rotors Composed of 30Cr2Ni4MoV Steel. Energies 2024, 17, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivasagam, R.; Richard, S. Review on recent developments in pulsed high power systems. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Engineering Facilities Maintenance and Management Technologies (EFM2T’21), Palapye, Botswana, 28–29 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zu, Y.; Guo, J.; Yin, H.; Song, Q.; Tang, X. A solid-state pulse power sub-nanosecond SiC DSRD-based generator with high-voltage and high repetition frequency for pulse discharge water treatment. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 119053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.K.; Mitra, S.; Mondal, J.; Roy, A. Comparative Study of Different High Voltage Switches Used in Pulsed High Voltage Application. Power Res. J. CPRI 2024, 19, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, J. Electrode erosion of a high energy impulse spark gap switch. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2005, 7, 3157–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Cao, N.; Wang, Y.; Xue, P. Research on Self-breakdown Performance of Gas Spark Gap Switch. High Volt. Eng. 2021, 57, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Pei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q. Electrode erosion properties of gas spark switches for fast linear transformer drivers. Phys. Plasmas 2017, 24, 122108–1–122108-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukin, S.N. Pulsed power technology based on semiconductor opening switches: A review. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2020, 91, 011501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, V.; Voss, L.; Flicker, J.D.; Rodriguez, L.G.; Hjalmarson, H.P.; Lehr, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Pickrell, G.; Ghandiparsi, S.; Kaplar, R. Photoconductive Semiconductor Switches: Materials, Physics, and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chung, H.S.-H.; Li, R.T.-H. Characterization and Experimental Assessment of the Effects of Parasitic Elements on the MOSFET Switching Performance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; He, Z.; Guo, R.; Ma, J.; Zhao, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Xu, T. Characterization of the high current triggered vacuum switch. Vacuum 2012, 86, 1911–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholfield, D.W.; Butcher, M.D.; Hilko, B.; Dorr, G. Vacuum switch performance in a 1.2 MJ pulse forming network. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2008, 79, 024703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Tan, X.; Du, T.; Tang, B.; Shang, S.; Li, R.; Li, Z. Electrode erosion research of gas spark gap. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2014, 26, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, A.; Shang, S.; Jin, D. Experimental investigation of electrode erosion of triggered spark gap. In Proceedings of the 27th International Symposium on Discharges and Electrical Insulation in Vacuum (ISDEIV), Suzhou, China, 18–23 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, W.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, M.; Zhou, M.; Yang, W. Modeling of Electrode Erosion Process in Gas Spark Switch. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2023, 43, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Han, R.; Ding, W.; Qiu, A.; Tang, J. Note: Erosion of W-Ni-Fe and W-Cu alloy electrodes in repetitive spark gaps. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2018, 89, 026103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silakhori, K.; Neghabi, M.; Torabi, R. Investigation on electrode erosion effects in high frequency rotary spark gap switches. Optik 2021, 237, 166763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Li, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, M.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Gong, H.; Gan, Y.; Jin, X.; Novac, B.M.; et al. Electrode Erosion and Lifetime Performance of a Compact and Repetitively Triggered Field Distortion Spark Gap Switch. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2020, 48, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Qi, X.; Lin, F. Analysis on Electrode Replacement of Spark-Gap Switches with Graphite Electrodes. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2011, 39, 1874–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gan, Y.; Li, C.; Li, F.; Jin, X.; Song, F. Research on channel resistance and thermal effect characteristics of gas-filled spark gap switch. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2024, 36, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Jin, D.; Tan, X. Statistical analysis of particulate concentration from electrode erosion of gas discharge. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 015202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, G.; Di Fatta, A.; Rizzo, G.; Ala, G.; Romano, P.; Imburgia, A. Comprehensive Review of Wide-Bandgap (WBG) Devices: SiC MOSFET and Its Failure Modes Affecting Reliability. Physchem 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-T.; Gu, Z.-H. Review on Driving Circuits for Wide-Bandgap Semiconductor Switching Devices for Mid- to High-Power Applications. Micromachines 2021, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Wu, B.; Lan, X.; Xia, Y.; Chen, J.; Tang, L. Research on Improving the Avalanche Current Limit of Parallel SiC MOSFETs. Electronics 2025, 14, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grome, C.A.; Ji, W. A Brief Review of Single-Event Burnout Failure Mechanisms and Design Tolerances of Silicon Carbide Power MOSFETs. Electronics 2024, 13, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Blaabjerg, F.; Wang, H.; Liserre, M.; Iannuzzo, F. Catastrophic Failure and Fault-Tolerant Design of IGBT Power Electronic Converters—An Overview. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial-Electronics-Society (IECON), Vienna, Austria, 10–14 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, J.; Reynes, J.-M.; Morel, H.; Frey, P.; Perrotin, O.; Allirand, L.; Azzopardi, S.; Piton, M.; Coccetti, F. Test Methodology for Short-Circuit Assessment and Safe Operation Identification for Power SiC MOSFETs. Energies 2024, 17, 5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszada, M.A.; Gajanur, N.; Mazumder, S.K. Assessing the reliability of SiC MOSFET through inverter-like accelerated test vs. power cycling test. Microelectron. Reliab. 2025, 165, 115589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.; Vainshtein, S.N.; Kostamovaara, J.T. Modified High-Power Nanosecond Marx Generator Prevents Destructive Current Filamentation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 7845–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yin, Y. Reliability of Wide Band Gap Power Electronic Semiconductor and Packaging: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Singh, B.P.; Liu, Y.; Norrga, S. Failure Characterization of Discrete SiC MOSFETs under Forward Power Cycling Test. Energies 2024, 17, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelis, A.J.; Green, R.; Habersat, D.B.; El, M. Basic Mechanisms of Threshold-Voltage Instability and Implications for Reliability Testing of SiC MOSFETs. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2015, 62, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volosov, V.; Bevilacqua, S.; Anoldo, L.; Tosto, G.; Fontana, E.; Russo, A.-L.; Fiegna, C.; Sangiorgi, E.; Tallarico, A.N. Positive Bias Temperature Instability in SiC-Based Power MOSFETs. Micromachines 2024, 15, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckbrodt, J.; Ginot, N.; Batard, C.; Azzopardi, S. Monitoring of Gate Leakage Current on SiC Power MOSFETs: An Estimation Method for Smart Gate Drivers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 8752–8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouaida, R.; Berthou, M.; Leon, J.; Perpina, X.; Oge, S.; Brosselard, P.; Joubert, C. Gate Oxide Degradation of SiC MOSFET in Switching Conditions. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2014, 35, 1284–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AQG 324; Qualification of Power Modules for Use in Power Electronics Converter Units in Motor Vehicles. ECPE European Center for Power Electronics e.V.: Nuremberg, Germany, 2021.

- Janabi, A.; Shillaber, L.; Ying, W.; Mu, W.; Hu, B.; Jiang, Y.; Iosifidis, N.; Ran, L.; Long, T. Substrate Embedded Power Electronics Packaging for Silicon Carbide mosfets. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 9614–9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Yang, F.; Ma, D.; Zhao, C.; Pei, Y.; Gan, Y. Cu Clip-Bonding Method with Optimized Source Inductance for Current Balancing in Multichip SiC MOSFET Power Module. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 7952–7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, R.; Fang, H.; Li, P.; Zhao, L.; Wu, H.; Huang, Z.; Tao, J.; Hu, S. A Novel Deep-Trench Super-Junction SiC MOSFET with Improved Specific On-Resistance. Micromachines 2024, 15, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Y.; Lan, Z.; Hu, X.; Liu, D. Novel SiC Trench MOSFET with Improved Third-Quadrant Performance and Switching Speed. Micromachines 2024, 15, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Liao, A.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Ultra-thermostable embedded liquid cooling in SiC 3D packaging power modules of electric vehicles. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 276, 116499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlicek, N.; Mohn, F. Laser bonding of copper ribbons and clips on SiC power MOSFETs with sintered copper bond buffers. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE Electronics System-Integration Technology Conference (ESTC), Vestfold, Norway, 15–18 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.; Yao, X. Active dv/dt Control with Turn-off Gate Resistance Modulation for Voltage Balancing of Series Connected SiC MOSFETs. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 14–17 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama, H.; Okuda, T.; Hikihara, T. Digital active gate drive of SiC MOSFETs for controlling switching behavior-Preparation toward universal digitization of power switching. Int. J. Circ. Theor. Appl. 2022, 50, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Sun, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zheng, T.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, P. Active Gate Drive Based on Negative Feedback for SiC MOSFETs to Suppress Crosstalk Parasitic Oscillation and Avoid Decreased Efficiency. Electronics 2025, 14, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xing, W. Active Gate Driver with the Independent Suppression of Overshoot and Oscillation for SiC MOSFET Modules. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 2325–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Miao, Y. SiC MOSFET Active Gate Drive Circuit Based on Switching Transient Feedback. Energies 2024, 17, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, N. A Resonant Auxiliary Drive Circuit for SiC MOSFET to Suppress Crosstalk. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2022, 37, 3004–3015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Pei, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, F.; Ferreira, B. Overvoltage and Oscillation Suppression Circuit with Switching Losses Optimization and Clamping Energy Feedback for SiC MOSFET. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 14207–14219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Chen, J.; Jia, P. Analysis of DC-Side Snubbers for SiC Devices Application. Electronics 2022, 11, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Hoene, E.; Davari, P. An RC snubber design method to achieve optimized switching noise-loss trade-off of cascode GaN HEMTs. IET Power Electron. 2024, 17, 1583–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, M.; Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Analysis of carrier dynamics and thermal effect of the GaAs photoconductive semiconductor switch in lock-on mode. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2024, 57, 495101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Dang, X.; Hao, Q.; Li, X. Research on the thermal failure mechanism of an opposed-contact gallium arsenide photoconductive semiconductor switch in avalanche mode. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 215103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, L.; Cai, P.; Feng, C.; Xiao, H.; Wang, X. Properties Investigation and Damage Analysis of GaN Photoconductive Semiconductor Switch Based on SiC Substrate. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Xun, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; He, J.; Zhang, J. Breakdown Behavior of GaAs PCSS with a Backside-Light-Triggered Coplanar Electrode Structure. Electronics 2021, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Shi, Y.; Qian, G.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, T. Performance Enhancement of Planar GaAs Photoconductive Semiconductor Switches by Introducing p-Type Epitaxial Layer. Photonics 2025, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Jiang, L.; Xu, J.; Xiao, H.; Feng, C.; Wang, Q.; He, T.; Zhou, M.; Wang, X. Design of a lateral photoconductive semiconductor switch with a low resistivity region on semi-insulating GaN to enhance breakdown characteristics. Opt. Commun. 2024, 555, 130332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hu, L.; Dang, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Investigation on the Mechanism of Triggering Efficiency of High-Power Avalanche GaAs Photoconductive Semiconductor Switch. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2021, 42, 1646–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wei, J.; Zeng, F.; Jia, C.; Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Qian, B. Influence of the width of triggering region on output characteristics of GaAs photoconductive semiconductor switch. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2023, 35, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pokryvailo, A.; Carp, C.; Scapellati, C. High Performance, High-Power Capacitor Charging: Focus on Pulse-to-Pulse Repeatability. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Palm Springs, CA, USA, 21–25 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oomori, H.; Omura, I. An experimental study on switching waveform design with gate charge control for power MOSFETs. Power Electron. Devices Compon. 2023, 6, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.C. Advanced Materials for Thermal Management of Electronic Packaging, 1st ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, L.; Yang, Z.; Shen, S.; Deng, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Ding, W.; Ding, Z. Heat management technology for solid-state high voltage and high repetitive pulse generators: Towards better effects and reliability. High Volt. 2024, 9, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.L. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 5–138. [Google Scholar]

- de Bock, H.P.; Chamarthy, P.; Jackson, J.L.; Whalen, B. Investigation and Application of an Advanced Dual Piezoelectric Cooling Jet to a Typical Electronics Cooling Configuration. In Proceedings of the 13th IEEE InterSociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm), San Diego, CA, USA, 30 May–1 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sauciuc, I.; Yamamoto, R.; Culic-Viskota, J.; Yoshikawa, T.; Jain, S.; Yajima, M.; Labanok, N.; Amoah-Kusi, C. Carbon Based Thermal Interface Material for High Performance Cooling Applications. In Proceedings of the 14th InterSociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm), Orlando, FL, USA, 27–30 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhao, F.-Y. Thermoelectric cooling technology applied in the field of electronic devices: Updated review on the parametric investigations and model developments. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 148, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orville, T.; Tajwar, M.; Bihani, R.; Saha, P.; Hannan, M.A. Enhancing Thermal Efficiency in Power Electronics: A Review of Advanced Materials and Cooling Methods. Thermo 2025, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, D.; Drummond, K.P.; Sinanis, M.D.; Weibel, J.A.; Garimella, S.V.; Peroulis, D.; Janes, D.B. Design, Fabrication, and Characterization of a Compact Hierarchical Manifold Microchannel Heat Sink Array for Two-Phase Cooling. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 9, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xia, X.; Wang, P.; Zhou, B.; Chen, S.; Shi, Y. Study on the pillars structure impacts on the embedded microchannel heat sink. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT), Dalian, China, 10–13 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sporer, B.J.; Shah, A.P.; Dowhan, G.V.; Shapovalov, R.V.; Packard, D.A.; Wisher, M.; Leckbee, J.J.; Hendricks, K.J.; Hoff, B.W.; Lau, Y.Y.; et al. Multicavity linear transformer driver facility for Z-pinch and high-power microwave research. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2021, 24, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y. Immersion liquid cooling for electronics: Materials, systems, applications and prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 114989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic-Smith, A.; Rogers, D.J. Compact Two-Phase Immersion Cooling with Dielectric Fluid for PCB-Based Power Electronics. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2024, 5, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Wai, L.C.; Feng, H. Development and Demonstration of a Novel Immersion Two Phase Cooling High Power SiC Power Module. In Proceedings of the IEEE 73rd Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Orlando, FL, USA, 30 May–2 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ding, W. High power and high repetition frequency sub-nanosecond pulse generator with two-phase immersion cooling technique. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2021, 92, 034716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manepalli, V.V.; McAfee, R.C.; Randriambololona, A.M.; Graham, S.; Agonafer, D. Dynamic Thermal Management of a MOSFET Power Module Using a Novel Three-Component Phase Change Material. J. Heat Transf. 2025, 147, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleinikov, E.; Barzdenas, V. Comparative Analysis of High-Voltage High-Frequency Pulse Generation Techniques for Pockels Cells. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloya, E.; Lucía, O.; Sarnago, H.; Burdío, J. Heat Management in Power Converters: From State of the Art to Future Ultrahigh Efficiency Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 7896–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorecki, K.; Posobkiewicz, K. Cooling Systems of Power Semiconductor Devices-A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhumal, A.R.; Kulkarni, A.P.; Ambhore, N.H. A comprehensive review on thermal management of electronic devices. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 70, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Chen, P.; Jiang, S.; Zhuang, J.; Rao, J. A Solid-State Marx Generator with Prevention of through Current for Rectangular Pulses. Electronics 2024, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J. Analysis of control signal jitter in the distributed synchronous trigger control system for pulse power combining. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3079, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Cheng, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, R. Research on multi-switch synchronization based on single trigger generator. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 055117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damideh, V.; Btaiche, J.C.; Ho, A.; Spielman, R.B.; Lehr, J.M.; Mehlhorn, T.A.; Hassen, I.; Akoulov, A.; Aranfar, E.; McDonald, A.; et al. Experimental results of a 330 GW impedance-matched Marx generator. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, C.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, J.; Zhao, H.; Liu, K. A Flexible Solid-State Marx Modulator Module Based on Discrete Magnetic Coupling Drivers. Electronics 2023, 12, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.-Y.; Yang, J.-H.; Cheng, X.-B.; Chen, R.; Shu, T. A compact, low jitter, high voltage trigger generator based on fractional-turn ratio saturable pulse transformer and its application. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2022, 93, 084709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Liu, G.; He, M.; Shu, W.; Jiao, Y.; Li, H.; Yao, W.; Liang, X. A Low-Jitter Delay Synchronization System Applied to Ti:sapphire Femtosecond Laser Amplifier. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zou, W.; Zhou, L.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Deng, M.; Liu, D.; Zhu, J.; Lian, K.; et al. Development of a fusion-oriented pulsed power module. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2019, 22, 030401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wei, H.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, H. Fiber-optic controlled high voltage trigger generator for a ten-stage linear transformer driver module. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2025, 96, 065205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, M.S.S.; Shamsi, P.; Ferdowsi, M. EMC Modeling and Conducted EMI Analysis for a Pulsed Power Generator System Including an AC-DC-DC Power Supply. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2020, 48, 4250–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttaqi, K.; Haque, M. Electromagnetic interference generated from fast switching power electronic devices. Int. J. Innov. Energy Syst. Power 2008, 3, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Z.; Hu, M.; Chen, G.; Lu, W. EMI challenges in modern power electronic-based converters: Recent advances and mitigation techniques. Front. Electron. 2023, 4, 1274258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Choi, J.; Warnakulasooriya, T.; Shin, J.-W.; Imaoka, J.; Yamamoto, M. Improved Packaging of Power Module with Low-Permittivity Material for Low Common-Mode Noise and High Reliability. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 14261–14270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Tian, X.; Xue, L.; Bai, H.; Tolbert, L.M.; Cui, H. Integrated Common-Mode Filter for GaN Power Module with Improved High-Frequency EMI Performance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 6897–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Sheng, H.; Lakshmikanthan, S. Reduction and Cancellation Techniques for the Near Field Capacitive Coupling and Parasitic Capacitance of Inductors. In Proceedings of the EEE Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Signal Integrity and Power Integrity (EMC, SI & PI), Long Beach, CA, USA, 30 July–3 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, P.; Davari, P. Comparative Study on Temperature Dependency of dV/dt, dI/dt and EMI Generation for IGBTs, Si and SiC MOSFETs. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Paris, France, 1–5 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bheema, R.K.; Gopu, J.; Bhaskaran, K.; Verma, A.; Chavali, M.; Etika, K.C. A review on recent progress in polymer composites for effective electromagnetic interference shielding properties—structures, process, and sustainability approaches. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 5773–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahapurkar, K.; Gelaw, M.; Tirth, V.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Shahapurkar, P.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Kiran, M.C.; Ahmed, G.M.S. Comprehensive review on polymer composites as electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2022, 30, 09673911221102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W. Review of solid-state linear transformer driver technology. Matter Radiat. Extremes 2018, 3, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Abhishek, A.; Kumar, N.; Verma, B.K. Review of Nanosecond Pulse Generator with High-Power Switching Devices. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2024, 71, 5165–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazarakis, M.G.; Fowler, W.E.; LeChien, K.L.; Long, F.W.; Matzen, M.K.; McDaniel, D.H.; McKee, R.G.; Olson, C.L.; Porter, J.L.; Rogowski, S.T.; et al. High-Current Linear Transformer Driver Development at Sandia National Laboratories. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2010, 38, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.J.; Kang, Q.; Tan, J.; Luo, M.; Xiang, F. A High-Power Pulse Generator Based on Pulse Forming Network and Linear Transformer. Laser Part. Beams 2021, 2021, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Ye, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xia, L. Electric Field Enhancement Breakdown Caused by the Pulse Formation and Transmission of Parallel-Plate Blumlein Line. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2024, 52, 2281–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, B.-Y.; Xie, Y.-Z. Investigation of the waveform quality of a kA-level rectangular pulse generator based on pulse forming network. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2025, 96, 124709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Joshi, D.; Agrawal, P.K. Effect on timing drift due to temperature variation in high voltage pulse power supply. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Power, Energy, Control and Transmission Systems (ICPECTS), Chennai, India, 10–11 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Gao, R.; Ma, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y. Total Ionizing Dose Effects on Lifetime of NMOSFETs Due to Hot Carrier-Induced Stress. Electronics 2025, 14, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.J.; Haque, A.; Khachatrian, A.; Ildefonso, A.; Chernyak, L.; Ren, F. Review-Opportunities in Single Event Effects in Radiation-Exposed SiC and GaN Power Electronics. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 075004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Gao, F. Research Progress on Radiation Damage Mechanism of SiC MOSFETs Under Various Irradiation Conditions. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2024, 71, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, S.; Shi, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, Y. Excellent Vacuum Pulsed Flashover Characteristics Achieved inDielectric Insulators Functionalized by Electronegative Halogen-Phenyl and Naphthyl Groups. Langmuir 2022, 38, 4129–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; An, Y.; Yu, D.; Qi, J. Research Progress in Corrosion Protection Technology for Electronic Components. Metals 2023, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guo, Y.; Su, Y.; Tang, R.; Long, X. Growth kinetics of intermetallic compound in solder joints during thermal cycling: A review. In Proceedings of the 23rd Electronics Packaging and Technology Conference, Singapore, 1–3 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Yao, Q.; Chi, J.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; et al. Progress in semiconductor materials for photocathodic protection: Design strategies and applications in marine corrosion protection. Chemosphere 2023, 323, 138194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongvittayapanu, K.; Srisrual, A.; Fakpan, K. Effect of thermal cycling and vibration on cracking in Sn-3.0 Ag-0.5 Cu solder bump. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 2372–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lee, T.-K.; Liu, K.-C. Impact of 5% NaCl Salt Spray Pretreatment on the Long-Term Reliability of Wafer-Level Packages with Sn-Pb and Sn-Ag-Cu Solder Interconnects. J. Electron. Mater 2011, 40, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J. Delamination of Plasticized Devices in Dynamic Service Environments. Micromachines 2024, 15, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kabiri, M. In-situ characterization of moisture absorption and hygroscopic swelling of an epoxy molding compound for electronic packaging. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 5667–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, N.; Zhao, M.; Hu, X. Experimental Study on the Effect of Sand and Dust on the Performance of Photovoltaic Modules in Desert Areas. Energies 2024, 17, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshatnawi, F.; Enakerakpo, E.; Alhendi, M.; Abdelatty, M.; Umar, A.; Al-Haidari, R.; Shaddock, D.; Hoel, C.; Boyd, L.; Poliks, M.; et al. High stability and reliability additively manufactured metal-insulator-metal capacitors for high-temperature applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, G.C.; Myneni, S.B. Operation at Reduced Atmospheric Pressure and Concept of Reliability Redundancy for Optimized Design of Insulation Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Kareem, A.B.; Song, S.; Hur, J.-W. ANN-Based Reliability Enhancement of SMPS Aluminum Electrolytic Capacitors in Cold Environments. Energies 2023, 16, 6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Energy Storage Type | Energy Storage Form | Lifetime | Influencing Factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitive storage | Electric field | High cyclic stability and longevity | Overvoltage and overheating lead to material denaturation and lifetime reduction | [23,24] |

| Inductive storage | Magnetic field | Exceptional longevity and minimal inductive loss | High voltage and current handling requirements for switching elements. | [25,26,27] |

| Flywheel energy storage | Kinetic energy | Extended service life, requires periodic maintenance | Limited by bearing friction and rotor fatigue | [28,29,30] |

| Capacitor Type | Characteristic Failure Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer film capacitors | Dielectric breakdown Thermal accumulation causes dielectric aging and breakdown | [36,37,38] |

| Ceramic capacitors | Dielectric breakdown Thermal shock cracking | [39,40,41] |

| Electrolytic capacitors | Electrolyte evaporation Oxide film degradation and breakdown | [42,43] |

| Switch Category | Representative Devices | Characteristic Failure Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma switch | Gas spark gap switch Thyratron | Electrode melting and vaporization Particle splashing | [81,82,83] |

| Semiconductor switch | SiC MOSFETs, GaN HEMTs Photoconductive switches | High dV/dt Pulsed short-circuit Severe overcurrent Irreversible electrode degradation Excessive or uneven optical excitation energy | [84,85,86] |

| Vacuum switch | Triggered vacuum switch | Degradation of Vacuum Integrity Contact Erosion and Wear | [87,88] |

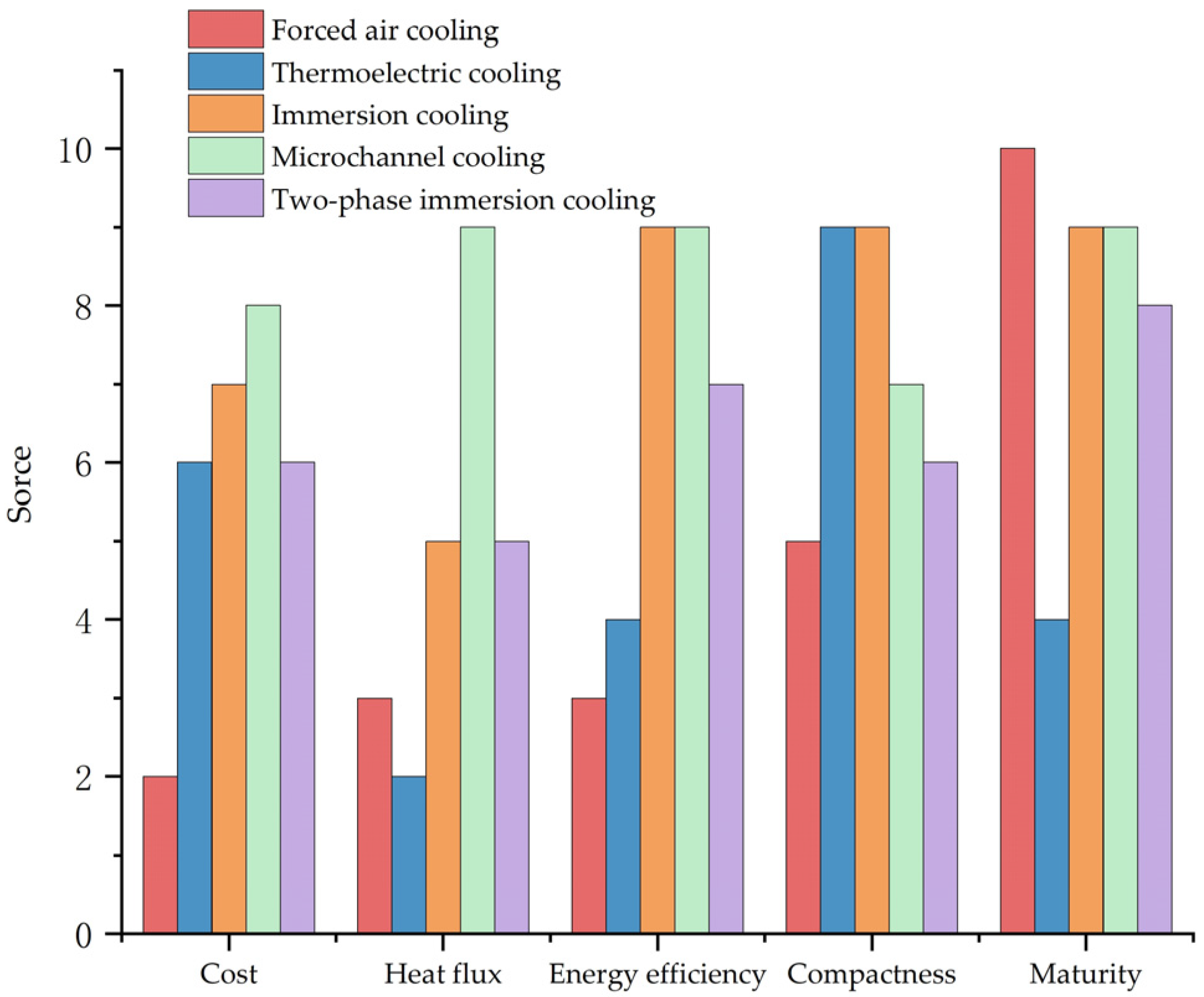

| Cooling Method | Suitable for Hierarchical Levels | Core Strengths | Limitations | Heat Transfer Coefficient (W/m2K) | High Heat Flux (W/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forced air cooling | System-level | Low cost, Simple structure, Large heat dissipation surface area | Limited heat dissipation capacity, High noise Dust accumulation | 2~25 | 10~35 |

| Thermoelectric cooling | Device-level Board-level Compact system-level | Precise temperature control, High reliability | Low efficiency, Self-generated heat degrades output parameters | Not applicable | 1~10 |

| Immersion cooling | Device-level Board-level | High heat dissipation capacity, Compact structure, Low noise | System complexity and risk of leakage | 50~1000 | 50~70 |

| Microchannel cooling | Device-level Board-level | Compact volume Rapid transient response | High cost High pressure drop | 100~20,000 | 100~1000 |

| Two-phase immersion cooling | Device-level Board-level System-level | Excellent heat dissipation, Excellent temperature uniformity, Strong environmental adaptability, Low noise | High cost Complex structure Poor Maintainability | 2500~100,000 | 50~100 |

| Triggering Method | Technical Characteristics | Jitter Precision | Scalability | Cost | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical triggering | Based on corona stabilized triggered switch | 3.1–4.8 ns | Low | Low | [159] |

| Cascaded amplification architecture: comprises an 8-channel digital delay generator (DDG), a pulse generator (PG), and a compact low-inductance Marx generator. | <2 ns | High | Middle | [160] | |

| FPGA timing control and magnetic ring transformers | Jitter depends on FPGA clock | High | Middle | [161] | |

| All-solid-state design, primary windings on individual cores; secondary winding encloses all cores, functioning as the Marx circuit magnetic switch | 0.64–2.53 ns | High | Middle | [162] | |

| FPGA timing control combined with a compensation circuit consisting of an active gated integrator and an output comparator | Picosecond level | High | high | [163] | |

| Optical triggering | Cascaded amplification architecture and high-power ultraviolet laser | <1 ns | High | Very high | [164] |

| Combining DC bias avalanche photoconductive semiconductor switch (PCSS) and spark gap switch | <3 ns | High | Middle | [165] |

| PPS Architecture | Operational Characteristics | Critical Components | Main Failure Mechanisms | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marx generator | High-voltage pulsed output High efficiency Flexible parameter adjustment | Switch Energy storage elements | Dielectric aging Switch Electrode Erosion Synchronization-induced Overvoltage | Electrode material and cooling optimization Low-jitter trigger system |

| Linear transformer driver (LTD) | High efficiency High power density Modular scalability | Magnetic Core Winding Switch Capacitance | Magnetic core loss and heating Dielectric breakdown Winding deformation | High-frequency low-loss magnetic material and liquid cooling Optimization of winding mechanical fixation |

| Pulse Forming Network (PFN) | Precise pulse waveform control Low system complexity High load adaptability | Inductance Capacitance Switch | Breakdown of capacitors and inductors Component overvoltage Breakdown | Overvoltage and Overcurrent protection Improved thermal management strategies |

| Blumlein Pulse Forming Line (BPFL) | Excellent pulse quality High voltage efficiency | Switch Blumlein transmission lines | Overcurrent-induced Switch breakdown Dielectric breakdown of transmission line | Addition of switch snubber circuit |

| Scenario | Environmental Stressors | Dominant Failure Mechanism | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerospace | Vacuum High-energy radiation | Surface flashover Thermal accumulation Oxide layer damage | Radiation-hardened design Derating usage |

| Navigation | High humidity High salinity Thermal cycling | Reduction in insulation resistance Solder joint fatigue | Coating design Advanced soldering technology |

| Desert | Long-term high temperature Sand interference | Thermal feedback loop caused by dust blockage and solar heat | High-temperature resistant design Hermetic sealing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Tong, H.; Wu, H.; Abu-Siada, A.; Li, K.; Yao, C. A Comprehensive Review of Reliability Analysis for Pulsed Power Supplies. Energies 2026, 19, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020518

Zhao X, Tong H, Wu H, Abu-Siada A, Li K, Yao C. A Comprehensive Review of Reliability Analysis for Pulsed Power Supplies. Energies. 2026; 19(2):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020518

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xiaozhen, Haolin Tong, Haodong Wu, Ahmed Abu-Siada, Kui Li, and Chenguo Yao. 2026. "A Comprehensive Review of Reliability Analysis for Pulsed Power Supplies" Energies 19, no. 2: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020518

APA StyleZhao, X., Tong, H., Wu, H., Abu-Siada, A., Li, K., & Yao, C. (2026). A Comprehensive Review of Reliability Analysis for Pulsed Power Supplies. Energies, 19(2), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020518