A Study on the Micro-Scale Flow Patterns and Ion Regulation Mechanisms in Low-Salinity Water Flooding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Apparatus and Materials

2.2. Experimental Setup and Structure

2.3. Experimental Procedure

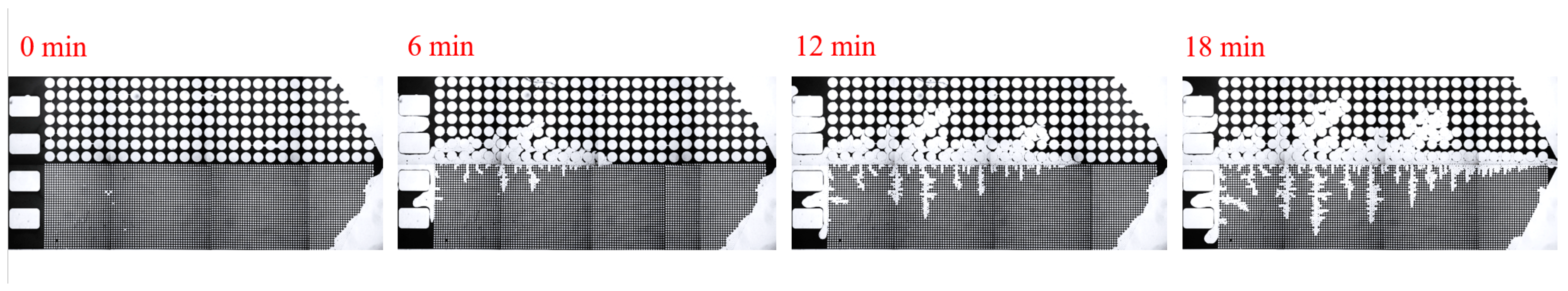

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

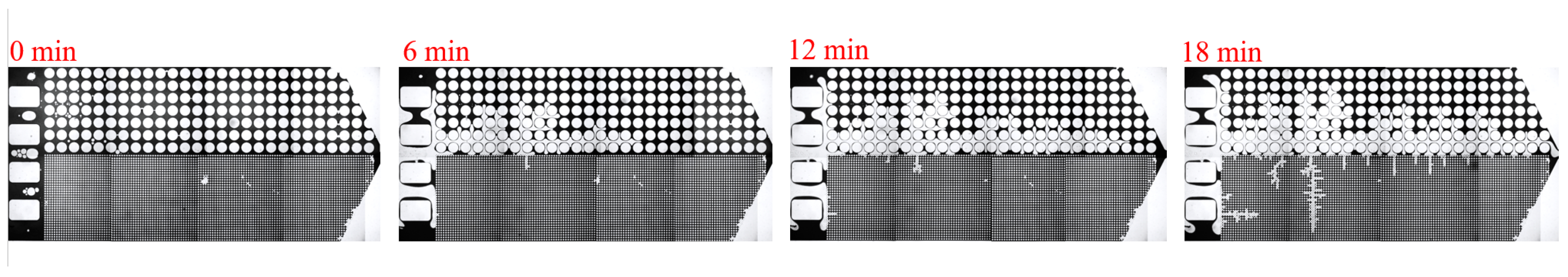

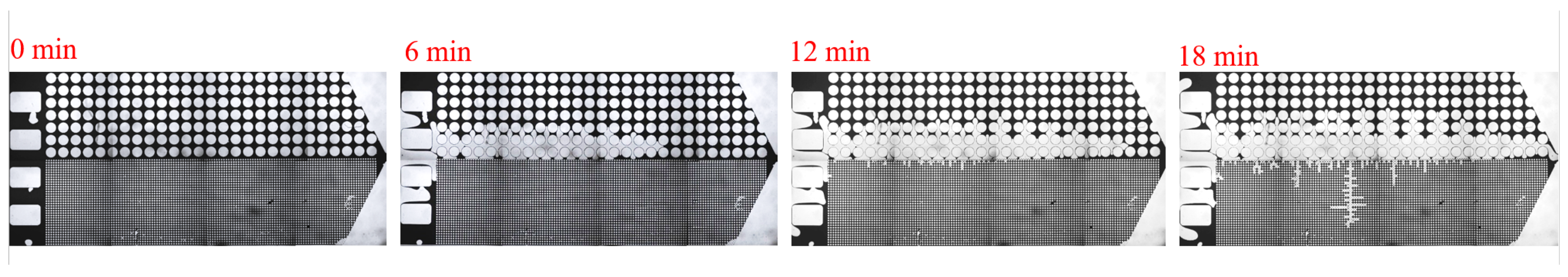

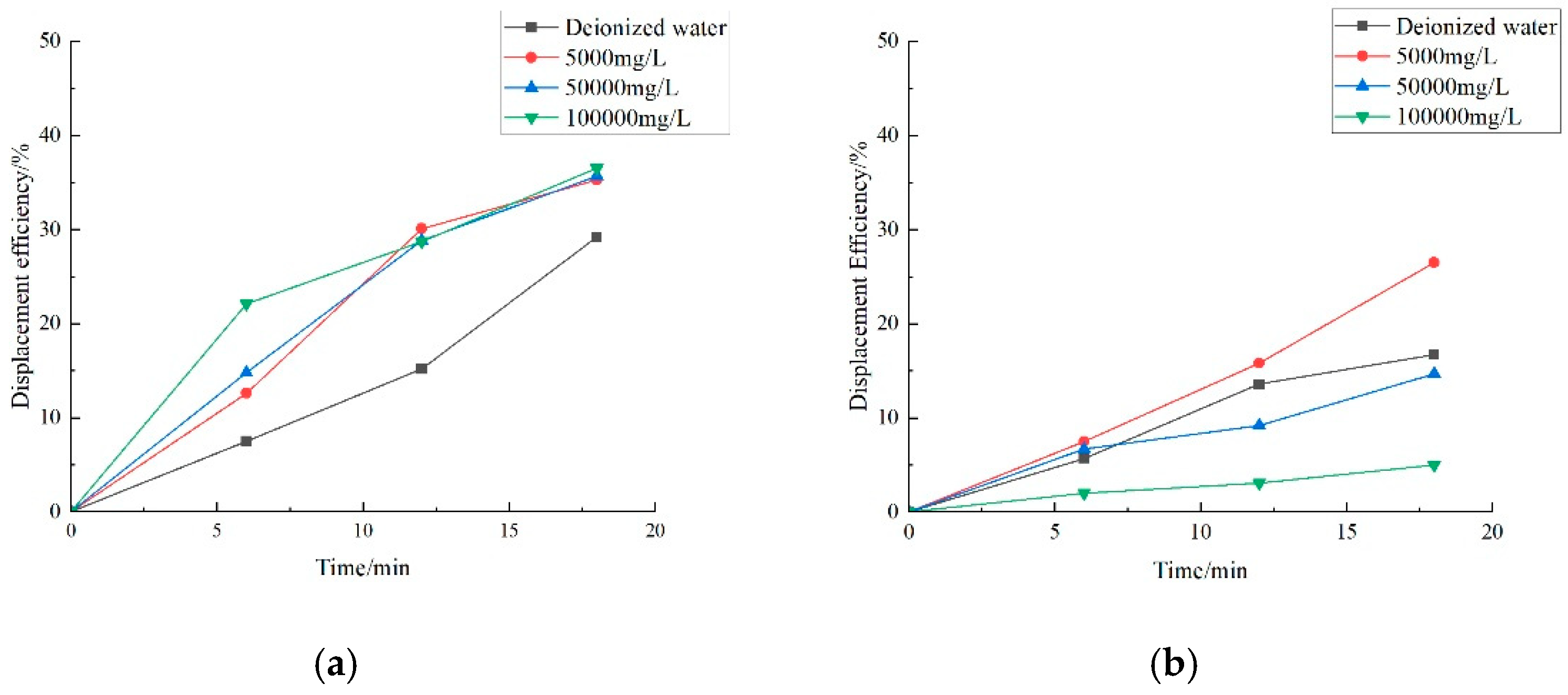

3.1. Effect of Salinity on Displacement Efficiency

3.2. Effect of Key Ion Types on Displacement Efficiency

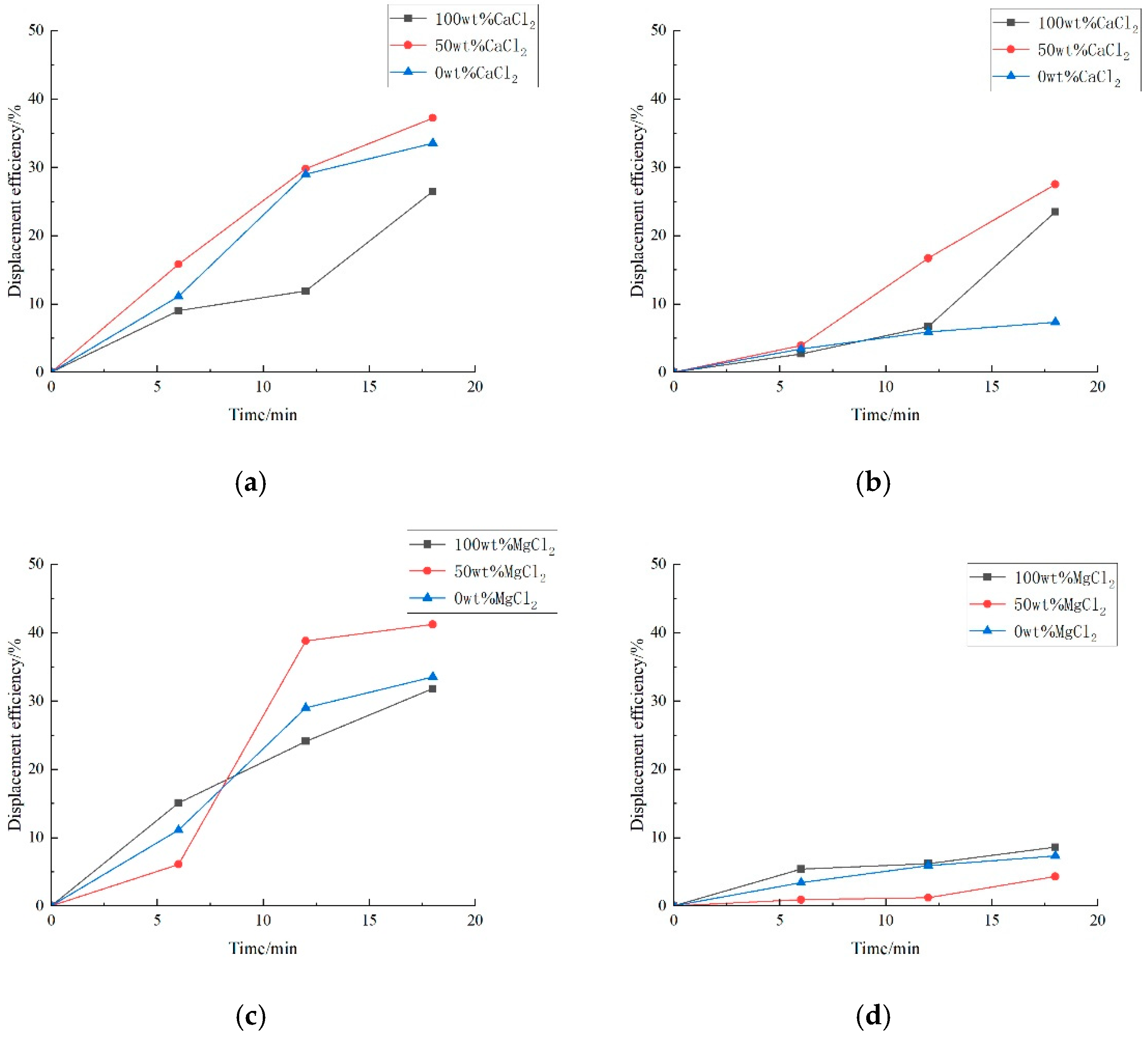

3.2.1. Key Cations

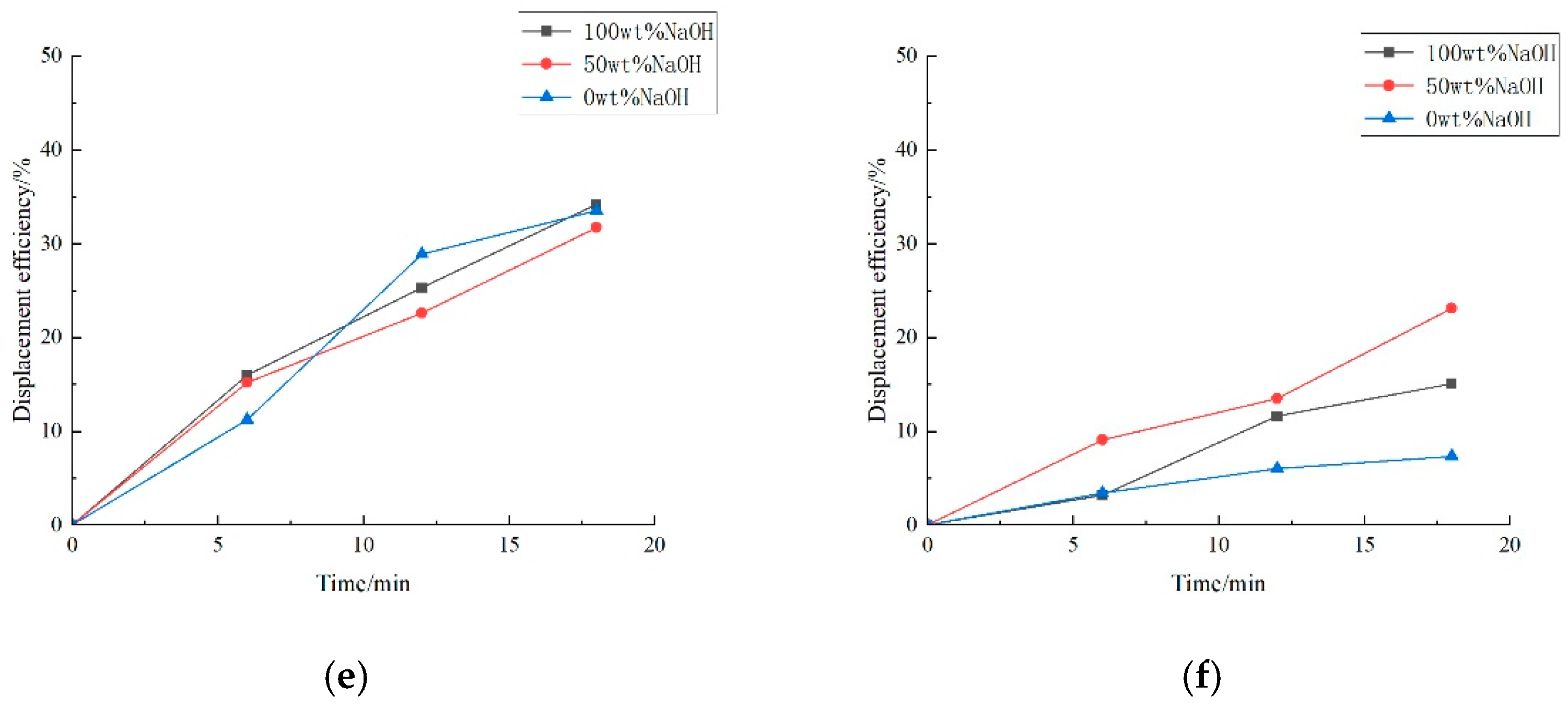

3.2.2. Key Anions

3.3. Effect of Key Ion Concentration on Displacement Efficiency

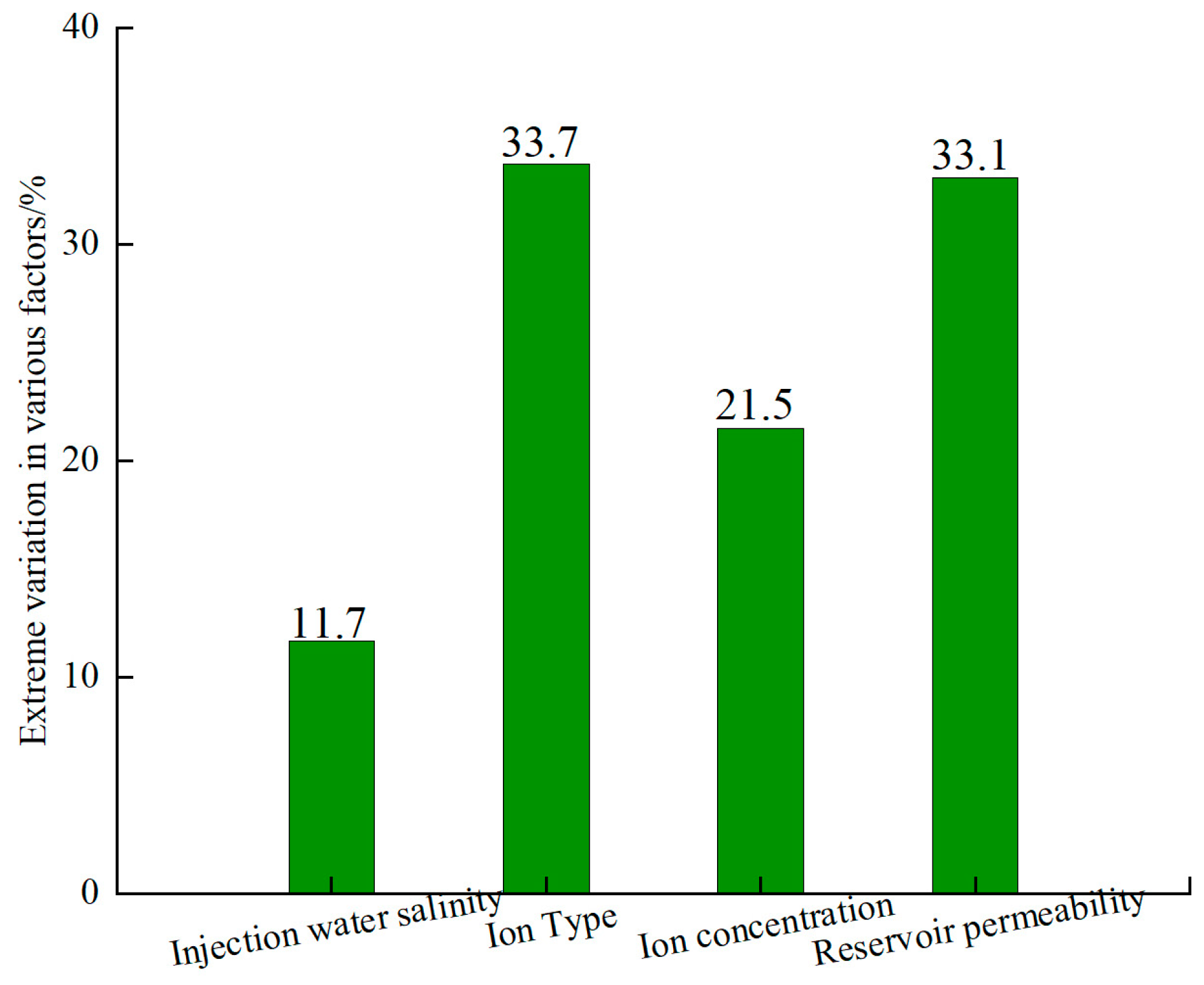

3.4. Analysis of the Significance of Influencing Factors

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, H.; Liu, X.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Radwan, A.E.; Yin, S. Study on Characteristics, Efficiency, and Variations of Water Flooding in Different Stages for Low Permeability Oil Sandstone. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 5245–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhao, G.; Yu, H.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Yuan, B. Study on the Law of Waterflooding Enhancement in Tight Reservoirs. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 087122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabi, O.; Al Kobaisi, M.; Haroun, M. Quantifying the Low Salinity Waterflooding Effect. Energies 2021, 14, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Shi, L.; Ogaidi, A.R.S.; Shan, X.; Ye, Z.; Qin, G.; Liu, J.; Wu, B. Application of Low-Salinity Waterflooding in Heavy Oil Sandstone Reservoir: Oil Recovery Efficiency and Mechanistic Study. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 30782–30793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Fan, P.; Chai, R.; Xue, L. Low-salinity water flooding in Middle East Offshore Carbonate Reservoirs: Adaptation to Reservoir Characteristics and Dynamic Recovery Mechanisms. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 076605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khishvand, M.; Oraki Kohshour, I.; Alizadeh, A.H.; Piri, M.; Prasad, S. A Multi-Scale Experimental Study of Crude Oil-Brine-Rock Interactions and Wettability Alteration during Low-Salinity Waterflooding. Fuel 2019, 250, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, L.; Yang, R.; Mcharo, W.; Tang, R. Relative Permeability Variations during Low-salinity water flooding in Carbonate Rocks with Different Mineral Compositions. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Saw, R.; Mandal, A. Experimental Investigation on Fluid/Fluid and Rock/Fluid Interactions in Enhanced Oil Recovery by Low-salinity water flooding for Carbonate Reservoirs. Fuel 2023, 352, 129156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uoda, M.K.; Hussein, H.Q.; Jalil, R.R. Experimental Investigation of Low Salinity Water to Improve Oil Recovery at Nassiriyah Oil Field. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 6191–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.; Karunarathne, C.I.; Al Jehani, A.S.; Al-Yaseri, A.Z.; Keshavarz, A.; Iglauer, S. Wettability Alteration during Low-salinity water flooding. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chang, Y.; Li, J.; Liang, T.; Guo, X. Mechanisms of Low Salinity Waterflooding Enhanced Oil Recovery and Its Application. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. 2015, 37, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Fan, H.; Wu, Z. Research Progress on Low-salinity water flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Oilfield Chem. 2022, 39, 554–563. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Olvera, G.; Reilly, T.M.; Lehmann, T.E.; Alvarado, V. Effects of Asphaltenes and Organic Acids on Crude Oil-Brine Interfacial Visco-Elasticity and Oil Recovery in Low-Salinity Waterflooding. Fuel 2016, 185, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadia, N.J.; Hansen, T.; Tweheyo, M.T.; Torsæter, O. Influence of Crude Oil Components on Recovery by High and Low Salinity Waterflooding. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 4328–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balavi, A.; Salari, A.; Ayatollahi, S.; Mahani, H. Asphaltene Deposition during Low-Salinity Waterflooding: Effects of Aging, Brine Salinity, and Injection Rate. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 11636–11649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, F.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Ling, C. Microfluidic Study on the Effect of Single Pore-Throat Geometry on Spontaneous Imbibition. Langmuir 2024, 40, 19209–19219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villero-Mandon, J.; Pourafshary, P.; Riazi, M. Oil/Brine Screening for Improved Fluid/Fluid Interactions during Low-salinity water flooding. Colloids Interfaces 2024, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Park, H.; Lee, J.; Sung, W. Enhanced Oil Recovery Efficiency of Low-salinity water flooding in Oil Reservoirs Including Fe2+ Ions. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2019, 37, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Dang, C.; Gorucu, S.E.; Nghiem, L.; Chen, Z. The Role of Fines Transport in Low Salinity Waterflooding and Hybrid Recovery Processes. Fuel 2020, 263, 116542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saedi, H.N.; Flori, R.E. Effect of Divalent Cations in Low-salinity water flooding in Sandstone Reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 283, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, H.; Wang, Y. Investigation on the Micro-Flow Mechanism of Enhanced Oil Recovery by Low-salinity water flooding in Carbonate Reservoir. Fuel 2020, 266, 117156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, E.; Sarmadivaleh, M.; Mohammadnazar, D. Numerical Modeling and Experimental Investigation on the Effect of Low-salinity water flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Carbonate Reservoirs. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2021, 11, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, R.K.; Mandal, A. Impact of phosphate ions on ion-tuned low salinity water flooding in carbonate reservoirs. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 342, 103539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M.; Manaka, M.; Ito, D. Experimental Evidence of Chemical Osmosis-Driven Improved Oil Recovery in Low-salinity water flooding: Generation of Osmotic Pressure via Oil-Saturated Sandstone. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 215, 110731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Fan, P.; Li, F.; Chai, R.; Xue, L. Application and Mechanisms of High-Salinity Water Desalination for Enhancing Oil Recovery in Tight Sandstone Reservoir. Desalination 2025, 614, 119165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Sharma, V.; Singh, A.; Tiwari, P. An Experimental Study of Pore-Scale Flow Dynamics and Heavy Oil Recovery Using Low Saline Water and Chemical Flooding. Fuel 2023, 334, 126756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour Khamaneh, M.; Mahani, H. Pore-Scale Insights into the Nonmonotonic Effect of Injection Water Salinity on Wettability and Oil Recovery in Low-Salinity Waterflooding. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 14764–14777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Asphalt Content (%) | Gelatinous (%) | Aromatic Hydrocarbons (%) | Saturated Hydrocarbons (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.3 | 10.2 | 15 | 71.5 |

| Number | Injection Water Type | Injection Water Salinity (mg/L) | Injection Water Composition | Ion Concentration (mmo/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Groundwater | 50,000 | NaCl (60 wt%), KCl (10 wt%), CaCl2 (15 wt%), MgCl2 (15 wt%) | Na+ 513, Ca2+ 67, Mg2+ 79, K+ 67, Cl− 872 |

| 2 | Injection water | 0 | Deionized water | Ion-free |

| 3 | Injection water | 5000 | NaCl (60 wt%), KCl (10 wt%), CaCl2 (15 wt%), MgCl2 (15 wt%) | Na+ 51.3, Ca2+ 6.7, Mg2+ 7.9, K+ 6.7, Cl− 87.2 |

| 4 | Injection water | 50,000 | NaCl (60 wt%), KCl (10 wt%), CaCl2 (15 wt%), MgCl2 (15 wt%) | Na+ 513, Ca2+ 67, Mg2+ 79, K+ 67, Cl− 872 |

| 5 | Injection water | 100,000 | NaCl (60 wt%), KCl (10 wt%), CaCl2 (15 wt%), MgCl2 (15 wt%) | Na+ 1026, Ca2+ 134, Mg2+ 158, K+ 134, Cl− 1744 |

| 6 | Injection water | 5000 | NaCl | Na+ 85, Cl− 85 |

| 7 | Injection water | 5000 | KCl | K+ 67, Cl− 67 |

| 8 | Injection water | 5000 | CaCl2 | Ca2+ 45, Cl− 90 |

| 9 | Injection water | 5000 | MgCl2 | Mg2+ 53, Cl− 106 |

| 10 | Injection water | 5000 | NaHCO3 | Na+ 60, HCO3− 60 |

| 11 | Injection water | 5000 | Na2CO3 | Na+ 94, CO32− 47 |

| 12 | Injection water | 5000 | Na2SO4 | Na+ 70, SO42− 35 |

| 13 | Injection water | 5000 | NaOH | Na+ 125, OH− 125 |

| 14 | Injection water | 5000 | NaCl (50 wt%), CaCl2 (50 wt%) | Na+ 42, Ca2+ 22, Cl− 86 |

| 15 | Injection water | 5000 | NaCl (50 wt%), MgCl2 (50 wt%) | Na+ 42, Mg2+ 26, Cl− 94 |

| 16 | Injection water | 5000 | NaCl (50 wt%), NaOH (50 wt%) | Na+ 105, Cl− 42, OH− 63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Yao, T.; Cui, Y.; Peng, L.; Ren, Y. A Study on the Micro-Scale Flow Patterns and Ion Regulation Mechanisms in Low-Salinity Water Flooding. Energies 2026, 19, 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020509

Liu X, Yao T, Cui Y, Peng L, Ren Y. A Study on the Micro-Scale Flow Patterns and Ion Regulation Mechanisms in Low-Salinity Water Flooding. Energies. 2026; 19(2):509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020509

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiong, Tuanqi Yao, Yueqi Cui, Lingxuan Peng, and Yirui Ren. 2026. "A Study on the Micro-Scale Flow Patterns and Ion Regulation Mechanisms in Low-Salinity Water Flooding" Energies 19, no. 2: 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020509

APA StyleLiu, X., Yao, T., Cui, Y., Peng, L., & Ren, Y. (2026). A Study on the Micro-Scale Flow Patterns and Ion Regulation Mechanisms in Low-Salinity Water Flooding. Energies, 19(2), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020509