1. Introduction

Air transport is among the most rapidly growing transport sectors, with 9.3 million flights in 2019 from European Union airports [

1], which reflects the importance of this dynamic industry. Aviation is responsible for approximately 2.4% of total global CO

2 emissions and contributes about 4% to the total global warming generated by human activities [

2,

3,

4], thus creating an urgent need for research on more sustainable and greener solutions. Through Onward, the European Green Deal and the Civil Aviation Organization are targeting net-zero emissions by 2050 or a 55% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 [

2].

A possible solution that would allow us to reach this target is to electrify propulsion systems. Fully electric aircraft (FEA) can radically solve the emission problem; however, hybrid-electric aircraft, requiring a smaller technological step, can be built within the timeframe imposed by the European project objectives. However, there are still limitations and challenges pertaining to this type of aircraft that make their integration into air transportation premature [

5], such as the low energy density of power sources (i.e., batteries), which reduces the operating range [

6].

Transforming traditional aircraft into FEA or HEA poses challenges related to developing subsystems that are better adapted to these models. One such subsystem is the thermal management system (TMS), which is crucial in electric and hybrid-electric aircraft [

2].

For conventional aircraft, the TMS is less critical due to the self-cooling action of the propulsion system [

7]. The main heat sources come from the propulsion system, which is located outside the aircraft fuselage and benefits from direct cooling by the outside air, and the generated heat is expelled with the exhaust gas [

8]. In electric and fully electric aircraft, there are multiple heat sources from components such as batteries, fuel cells, and power electronics [

9,

10]; these parts generate a significant heat load, and almost all are installed inside the aircraft body [

11], making them more difficult to cool and necessitating the design of a complex, larger, and more efficient TMS compared to TMSs used in traditional aircraft.

One challenge in designing a new TMS lies in weight and volume reduction [

10]. Cooling a high heat load, like the one produced by the propulsion system, requires a bulky TMS and additional installation space, creating significant design challenges and driving the need for innovative solutions to minimize weight and total volume [

12]. Several innovative TMS architectures can be found in the literature, such as the one for NASA’s ULI Program that uses an oil cooling loop and PCM for the TMS [

13]. Other, more complex systems, such as absorption refrigeration systems (ARSs) and cryogenic cooling, are still under development and face challenges regarding high volume and weight [

14].

Researchers are already developing less complex TMS using the most common cooling technologies, such as air-to-liquid cooling systems and vapor cycle systems [

15]. These cooling systems are widely used in disciplines such as automotive [

16], conventional aircraft [

15], and industrial equipment [

17]. Its functionality relies on convection and conduction principles, where a working fluid (e.g., water) absorbs heat and dissipates it via a heat sink. While efficient and reliable, scaling this system for large heat loads requires reaching a significant size [

18].

These two cooling systems are widely investigated in the literature as they are well-matured technologies. VCSs for large heat loads tend to be bulky and increase energy consumption, as mentioned in [

19]. The simple liquid-to-air system has been studied by several researchers, who have focused more on the design method and characteristics of the components. The design method mainly focuses on the heat exchanger (HX), which accounts for 80% of the system. However, the results show reduced performance in high-temperature conditions and large heat loads [

20,

21]. This lack of performance has been confirmed by another study investigating five different TMS configurations, which suggests that other innovative concepts and architectures must be explored for future aircraft [

22].

Other cooling systems similar to VCS, called two-phase, became much more widely adopted in electric vehicles [

23]. This system was used for spacecrafts as it has very high efficiency and is characterized by compactness [

24]. Recently, several studies investigated the use of this system as TMS in electric vehicles, while its use in aviation focuses on power electronics and electric-motor cooling in hybrid aircraft [

23,

25,

26]. However, when implementing this system as a TMS for the power systems of FEA and HEA [

27], few studies are available. An example is research focused on large-scale, fuel-cell-powered aircraft. This scarcity makes the study of this TMS particularly interesting due to its characteristics, which are applicable to other kinds of power systems, including those utilizing large battery capacities.

This study presents the first system-level, modular investigation of a P2PL TMS designed specifically for the battery pack of a hybrid-electric aircraft. This work aims to (1) develop an integrated modeling framework combining Python-based component sizing and Siemens Amesim dynamic simulation for this application; (2) apply the framework to a case study of a 1.4 MW aircraft battery with a 70 kW heat load, comprising a complete system mass budget and performance envelope; and (3) validate a pressure-based control strategy capable of maintaining battery temperature within safe limits across the full aircraft operational range, from −20 °C to +50 °C ambient conditions.

To prove the validity of the proposed model, a TMS able to maintain the 70 kW heat load released from the 1.4 MW battery that supplies power to the HEA below 40 °C was simulated and evaluated. The P2PL uses R450a refrigerant as the working fluid. The system’s functionality relies on the latent heat of the working fluid. The target fluid circulates in a cold plate, absorbing the heat load using latent heat and enabling efficient absorption. Meanwhile, the fluid shifts state from liquid to two-phase, continuing through the loop until it becomes condensate, at which point it is pumped again. In conventional cooling systems, heat is absorbed via specific heat, which is significantly lower than latent heat. For example, the specific heat of water used in air-cooled systems is 4.18 kJ/kg·K. However, the latent heat of the same fluid (water) is around 500 times greater, reaching approximately 2260 kJ/kg.

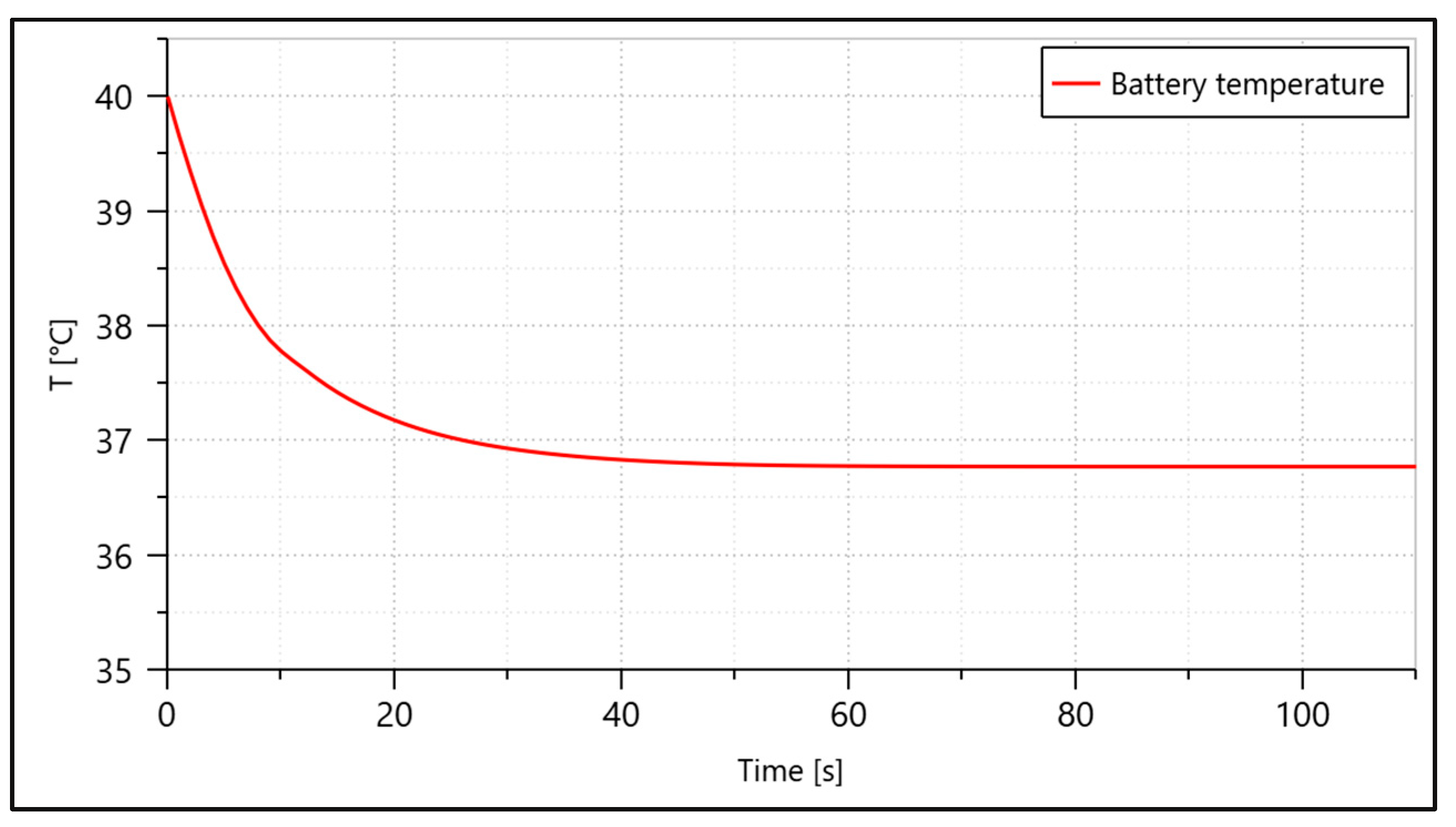

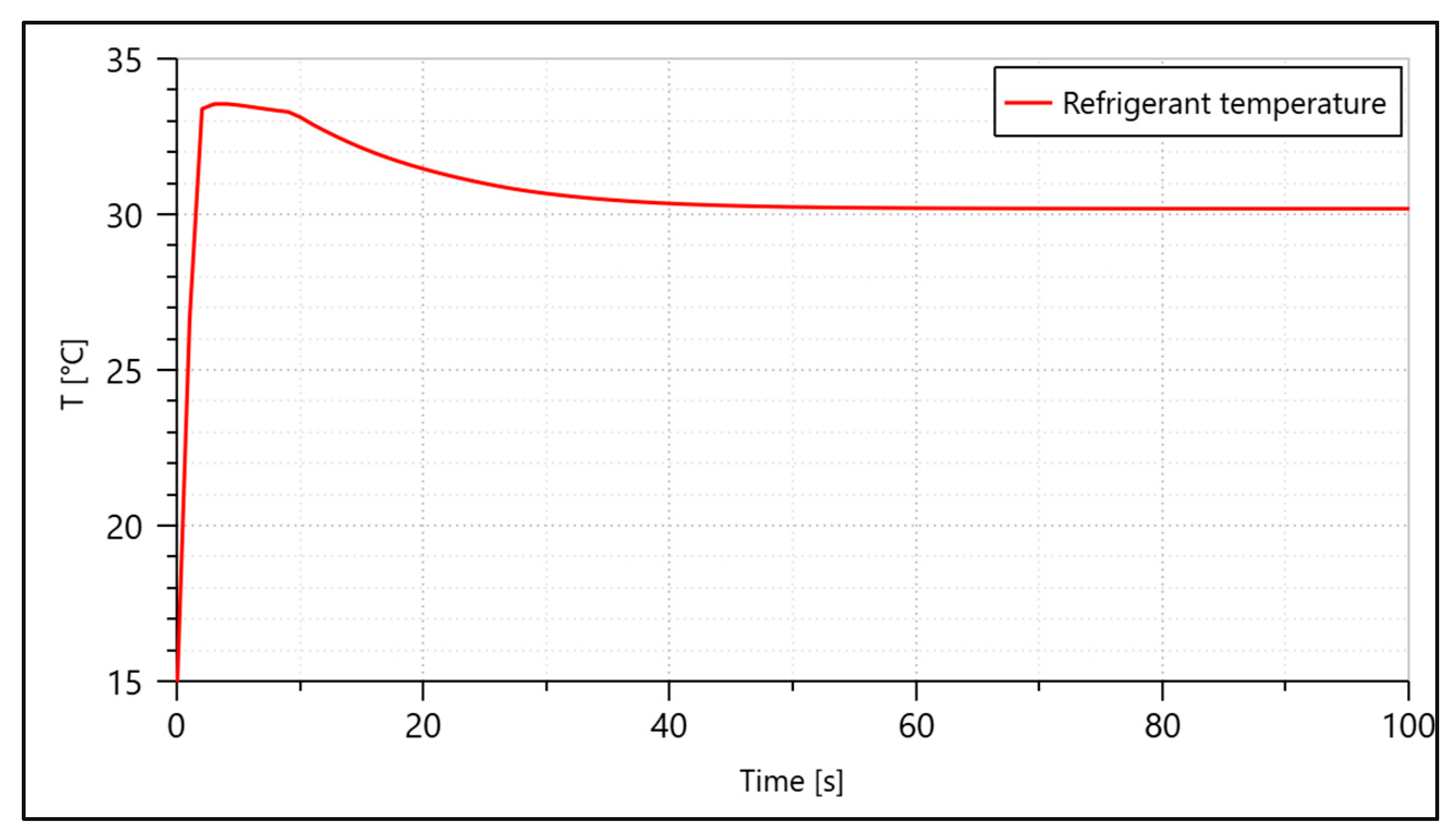

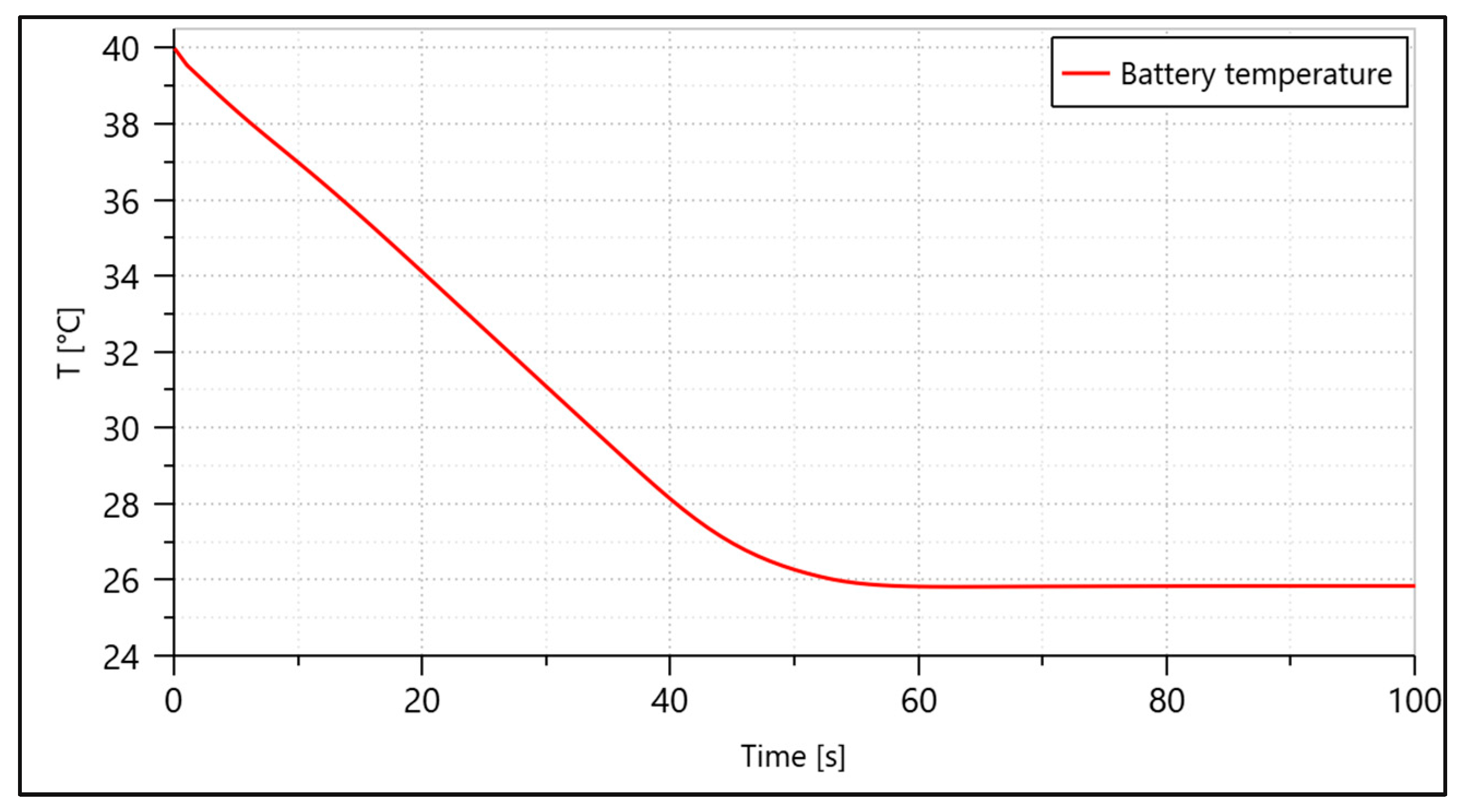

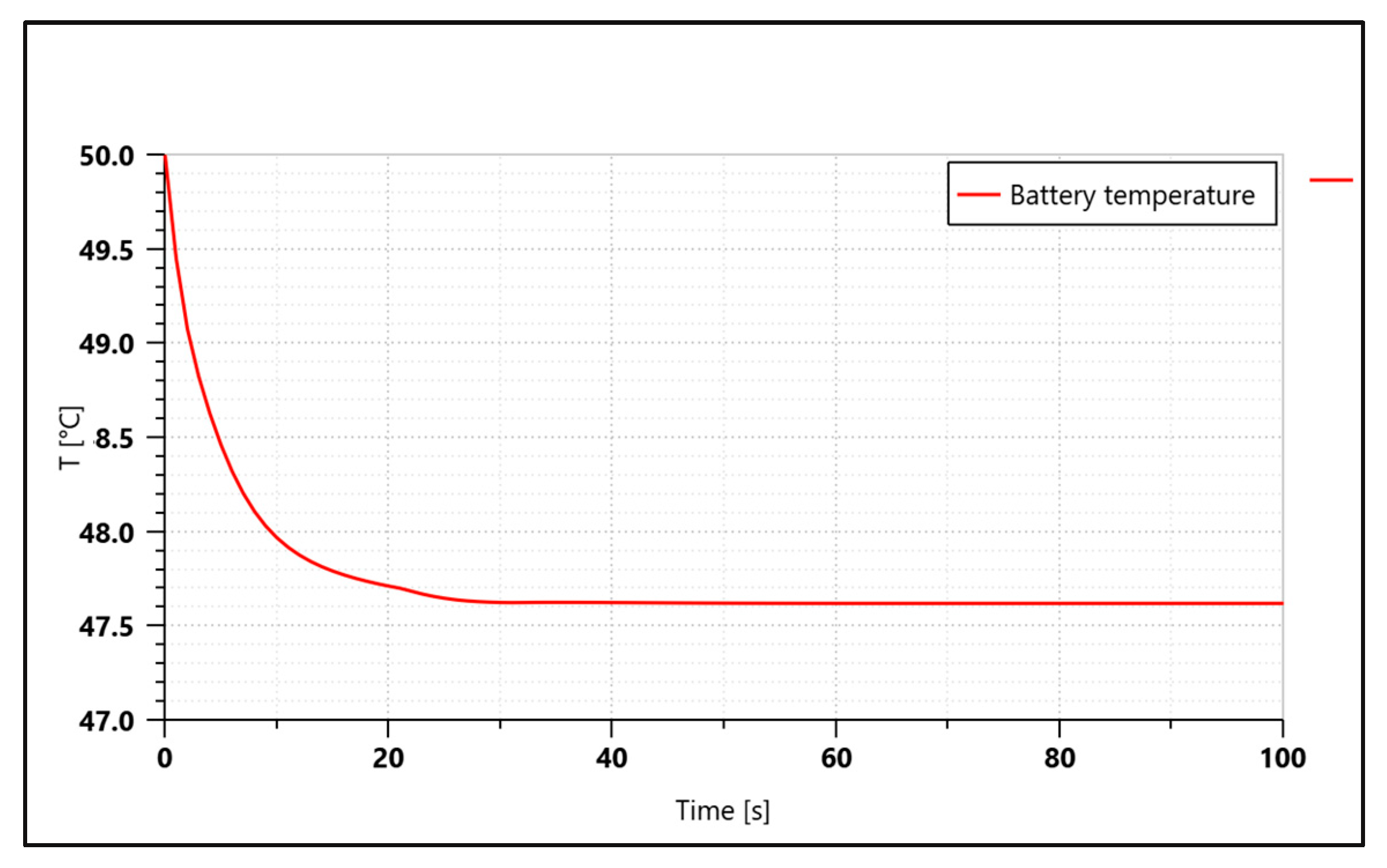

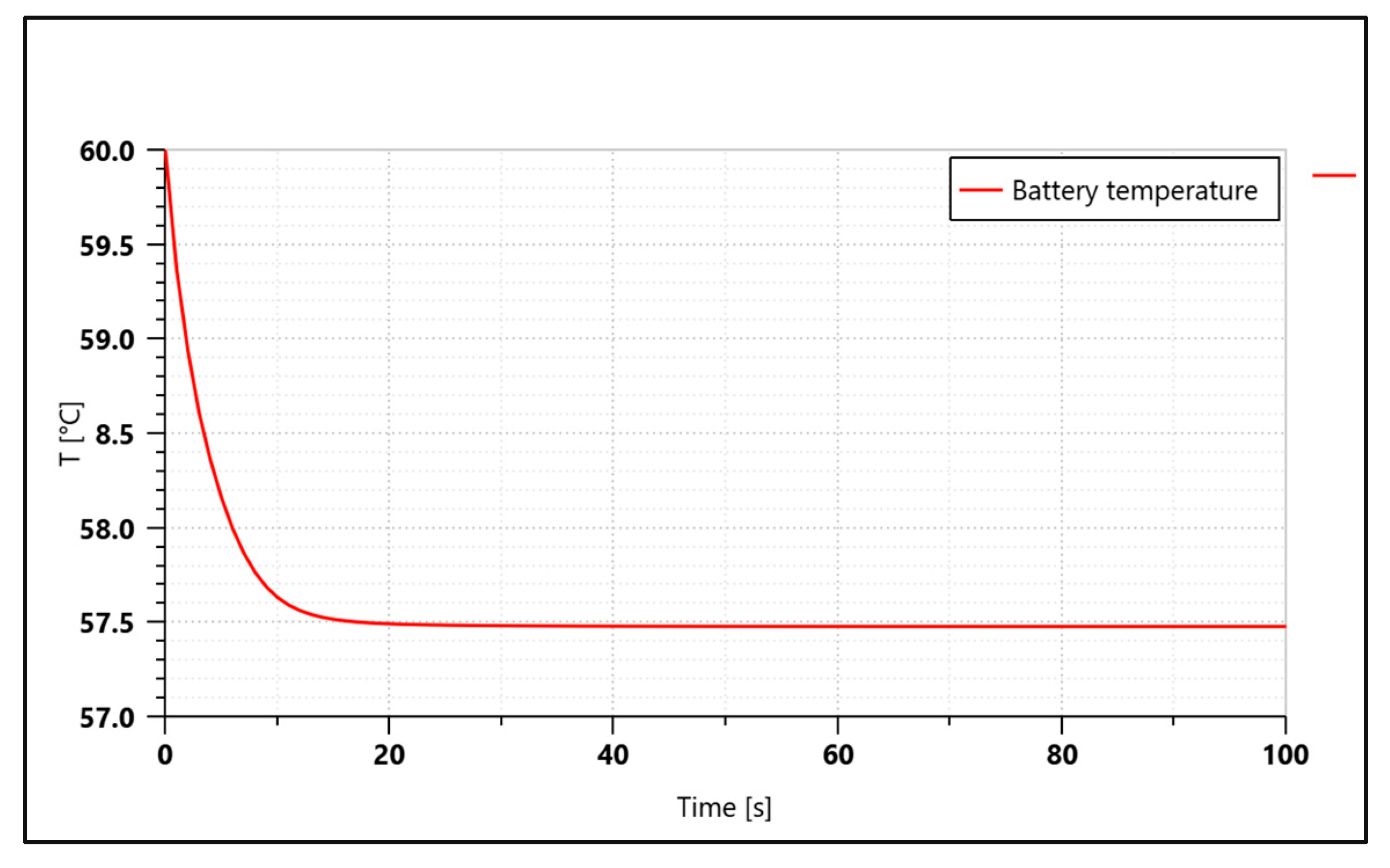

Section 2 outlines the methodology, which consists of a test case considering a 70 kW HEA battery heat load that should be maintained below 40 °C in three different environmental conditions. The second part covers the modularization and simulation model of the TMS. The proposed modeling uses Python code to estimate the size and weight of key system components, including the hydraulic diameter (Dh) of the cold plate and pipes and the condenser heat transfer area. The TMS is then simulated under three environmental conditions: a cold day, a standard day, and a hot day.

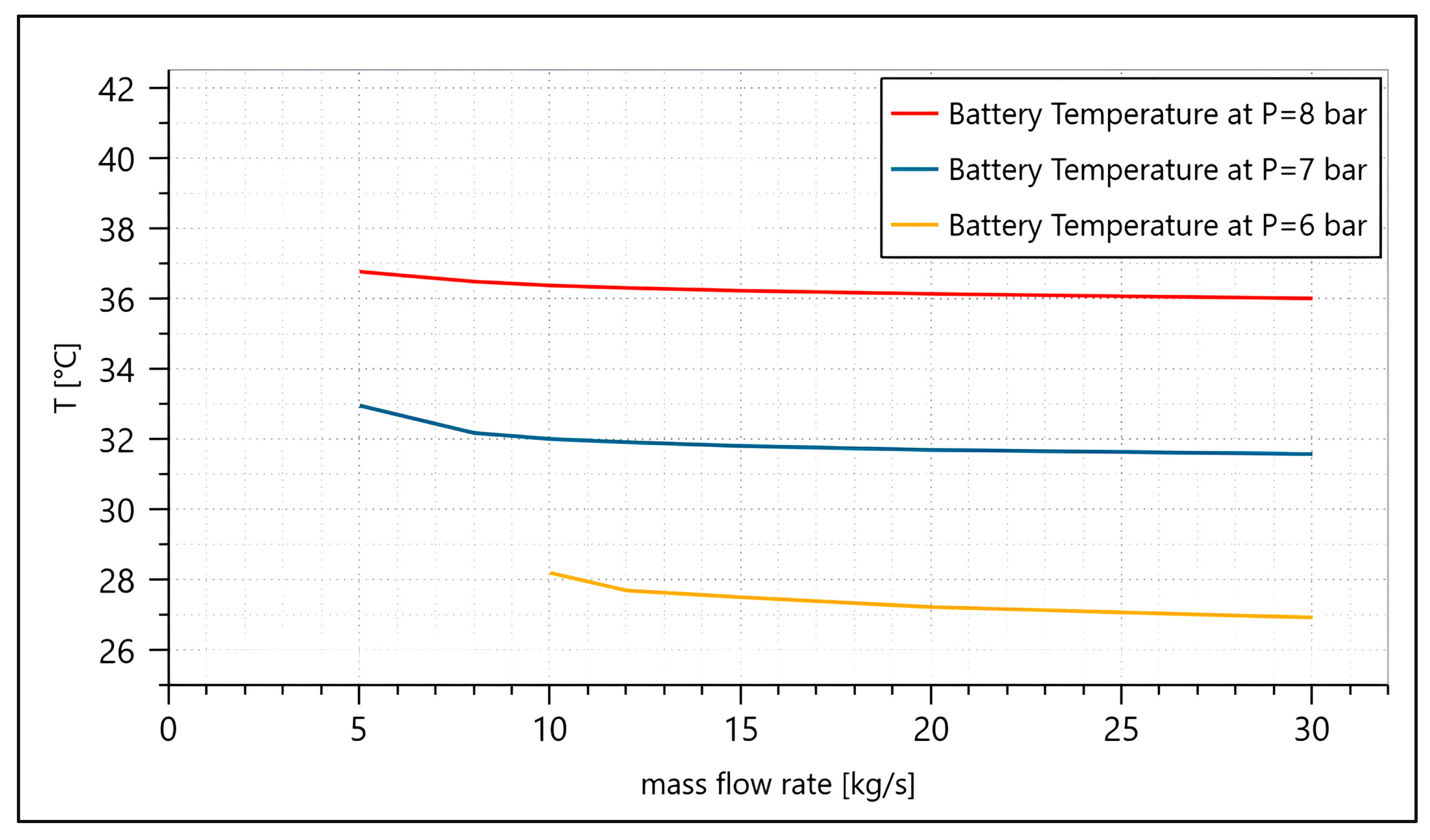

Section 3, the Results and Discussion, explains the outcomes of modeling the size and weight of components, while the simulation outcomes are defined for the three environmental conditions. The final battery temperature during cooling and the refrigerant condensation temperature are determined for cold and standard days, along with an analysis of the TMS operation under different system pressures. For the hot day, the maximum environmental battery temperature is defined as an outcome.

Section 4, Conclusion, summarizes the study and results obtained and outlines prospective future work.

2. Methodology

In this section, the case study is defined together with the environmental conditions, cold, standard, and hot day scenarios. The modeling and simulation of the thermal management system (TMS) are then introduced through a modular approach, and the system is evaluated under representative operating conditions.

2.1. Study Case

To prove the feasibility of the concept, a hybrid aircraft was used as a case study. The aircraft is targeted to be in service by 2030 based on the European directive, and it uses the battery as a second power source to support the takeoff and the rest of the mission profile of the aircraft to reduce polluting emissions. The power of the battery is assumed to be 1.4 MW, while its efficiency is 95%. The heat load generated by the battery is about 70 kW.

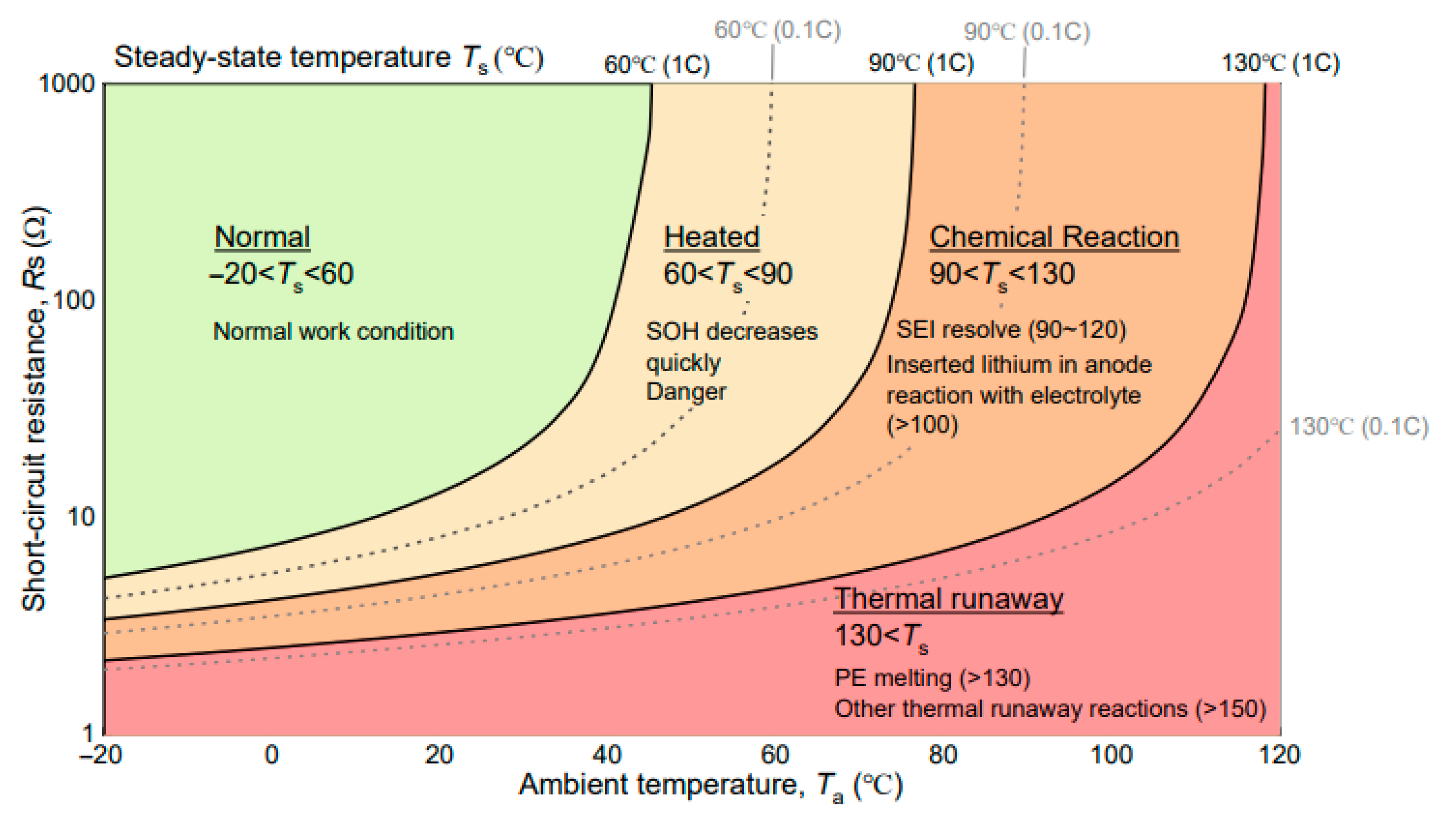

To properly design the TMS, it is important to take into account the battery temperature limitations. As mentioned in

Figure 1, Li-ion batteries used in electric vehicles or aircraft can operate properly at a safe operational temperature between −20 °C and 60 °C, while the optimal working temperature is between 15 °C and 40 °C [

28,

29,

30].

Another factor is the environmental conditions, which typically have a huge impact on system design. The design of the TMS components, especially the heat exchanger, will account for a hot day with a ground temperature of 40 °C. However, the proposed TMS is simulated under three conditions—standard day, hot day, and cold day, as shown in

Table 1—to assess its performance across the entire temperature envelope of the aircraft.

2.2. Modulization and Simulation Model

The design utilizes a thermal model to dimension the key components. This process is based on a computational method implemented in Python code, which defines the required size of the key components, including the following:

The required refrigerant mass flow rate;

DH of the cold plate tubes;

DH of the piping;

The minimum heat transfer area of the heat exchanger.

Based on the given inputs—such as refrigerant characteristics, environmental conditions, fluid input temperatures, and heat exchanger core geometry—the code performs an iterative calculation to define the required sizes. The algorithm begins with an assumed small geometry and grows the part in three dimensions using mathematical correlations and equations for condensation, boiling, and pressure drop until the required design conditions are met. The model also estimates the weight of these components.

The modeling assumptions and boundary conditions are mentioned in

Table A1, while the input parameters for Python sizing algorithm can be found in

Table A2.

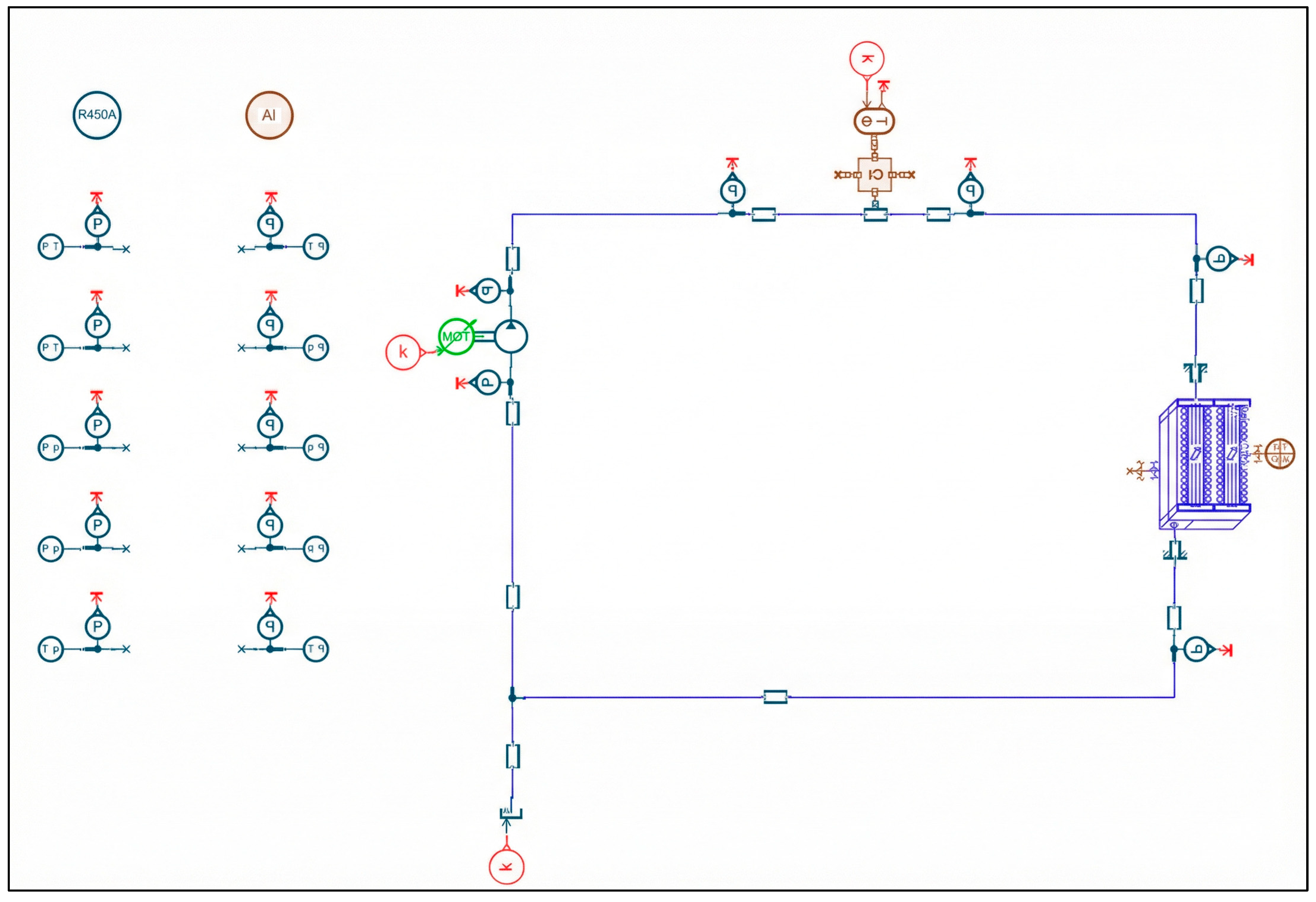

The results obtained from the model are used to build a simulation model in Siemens Simcenter Amesim software version 2310. This model is able to simulate the TMS performance across several environmental conditions.

2.2.1. Fluid Characteristics

The selection of the working fluids is the first step to start designing the system. To properly select the fluid, the following criteria must be fixed based on the case study:

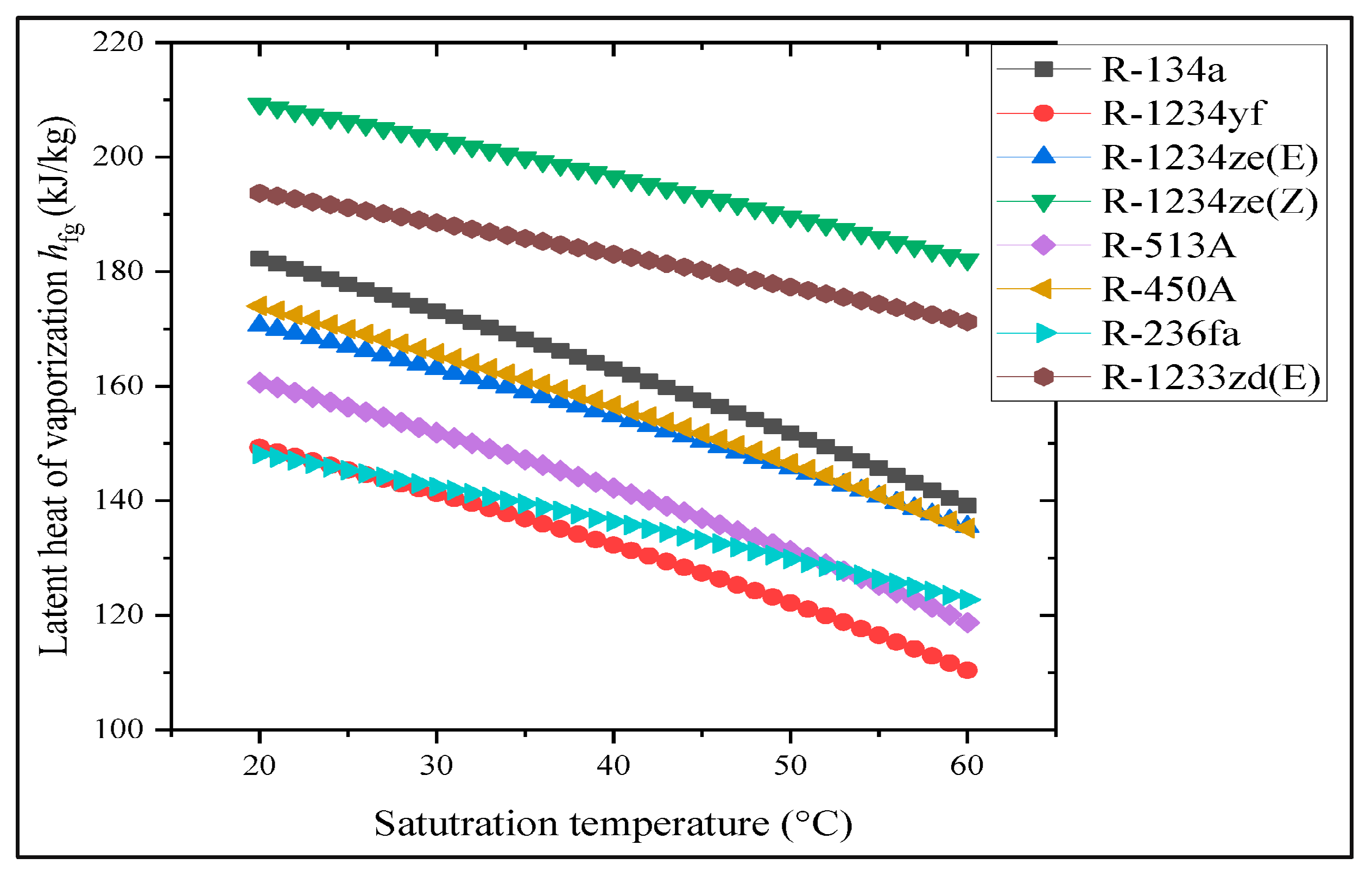

Several fluids demonstrate high efficiency, such as the widely used R134a, characterized by high performance. However, its high GWP leads to consideration of other fluids like R1233zd(E) and R1234ze(Z), noted for high latent heat. R450a is another refrigerant that follows these two in terms of latent heat, as demonstrated in

Figure 2, which shows the latent heat of vaporization and saturation temperature for the considered fluids. These characteristics make them good alternatives to R134a.

Toxicity and flammability must be addressed. 1233zd(E) is ranked ASHRAE Safety Class A2L (low toxicity, mildly flammable), while R450a and R1234ze(Z) meet ASHRAE Safety Class A1 (non-toxic, non-flammable).

Besides safety class and latent heat, the boiling and condensation point is a critical selection criteria. In the P-h diagram, a comparison of these three refrigerants at fixed temperatures of 35 °C and 40 °C, represented in

Table 2, shows saturation pressures of approximately 2.5 bar and 2.92 bar for R1234ze(Z), 1.8 bar and 2.15 bar for R1233zd(E), and 7.86 bar and 9.01 bar for R450A, respectively. This difference represents a major performance advantage for R450A.

The high-pressure difference (ΔP ≈ 1.15 bar) between the evaporation and condensation temperatures enables more stable condensation even with significant pressure drops. In contrast, refrigerants like R1234ze(Z) or R1233zd(E) exhibit a very small pressure difference (ΔP ≈ 0.42 bar), increasing the risk of incomplete condensation and system instability. This behavior was confirmed during simulation tests, where high-latent-heat, low-pressure refrigerants failed to fully condense under equivalent conditions.

R450a represents a good option meeting all criteria. It is composed of 42% R134a and 58% R1234ze(E), achieving lower GWP than R134a while meeting ASHRAE Safety Class A1.

2.2.2. Hydraulic Diameter Sizing

The working fluid passes through the installation piping and then to the evaporator, which works as a cold plate. The remaining necessary geometry to be defined includes the DH for the installation piping, ensuring minimal pressure drop and, more importantly, the DH for the cold plate tubes required to achieve the proper refrigerant boiling point.

These diameters are calculated using the thermal model through the application of two-phase fluid boiling equations to define the heat transfer coefficient (HTC) and pressure drop. Starting with the evaporator’s latent heat equation, the required refrigerant mass flow rate is determined from Equation (1).

where

is the heat load rejected by the battery,

is the refrigerant mass flow, and

is the latent heat of the refrigerant.

The heat transfer coefficient (

) for two-phase inside the cold plate is calculated using the general Kandlikar correlation for saturated two-phase flow boiling in horizontal tubes, applicable to widely used refrigerants [

33].

where

is the single-phase convective coefficient for liquids, calculated via the Dittus–Boelter correlation:

is the boiling number for the nucleate boiling region:

And

is the convection number for the convective boiling region:

The Froude number, Fr, of the possible effects of flow stratification in the horizontal flow is

The two-phase total pressure drop

inside the horizontal tube is represented by the sum of three terms.

where

= 0, the static pressure drop for a horizontal tube, and

is the acceleration pressure drop, calculated using the simplified homogeneous model in Equation (8):

is the frictional pressure drop, also calculated using a homogeneous model, as defined by Equation (9):

where

represents the friction factor, and

is the density averaged by the proportion of gas and liquid.

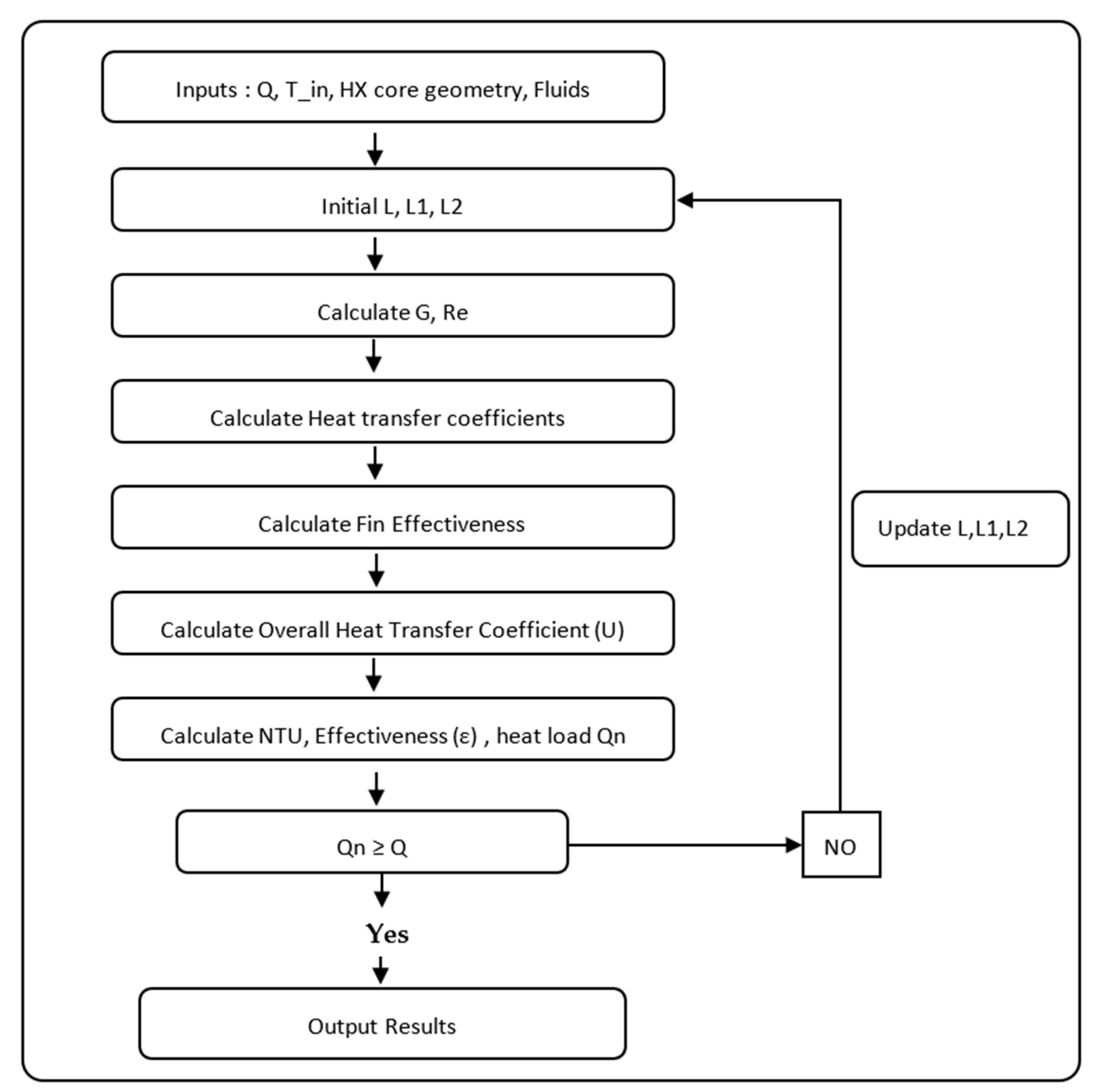

2.2.3. Condenser Sizing

The condenser used is the plate fin heat exchanger. A predefined internal geometry is selected from the literature [

34], while the final dimensions of the condenser are estimated using iterative calculation with a thermal model represented on a flowchart in

Figure 3. The NTU method is utilized for calculation:

The condensation coefficient and HTC are calculated using the Cavallini correlation, which is validated for the R50a refrigerant [

35].

where

is the equivalent Reynolds number, defined by

And

is the liquid Reynold number:

The pressure drop is calculated using the same simplified homogeneous model, Equation (8), as it is able to calculate pressure drop during both condensation and evaporation.

The condenser dry weight is calculated using Equation (17):