Modeling and Performance Assessment of a NeWater System Based on Direct Evaporation and Refrigeration Cycle

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The NeWater System

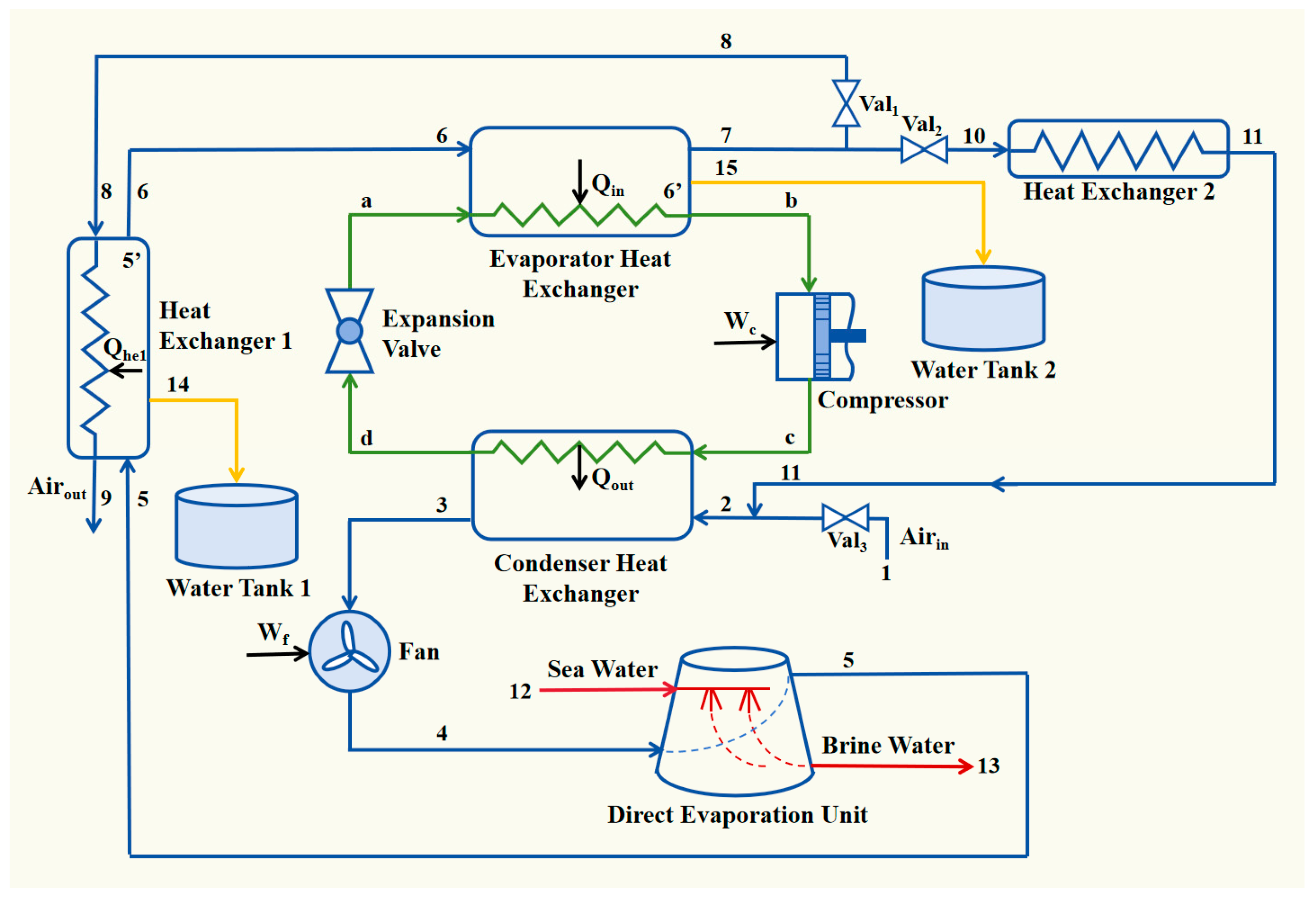

2.1. System Description

2.2. Structure and Operation Modes of the NeWater System

3. Mathematical Modeling of NeWater System

3.1. Model Assumptions

- The system operates under steady-state conditions;

- The apparatus and the cooling water recirculation loop are thermally insulated from the surroundings;

- Heat transfer by radiation is neglected;

- Water loss caused by drift is considered negligible;

- Air and water are uniformly distributed at the inlets, and this uniform distribution is maintained throughout the process;

- The outlet air from the direct evaporation unit is assumed to have a constant relative humidity;

- When air passes through HE1 and HE2, its outlet temperature is predefined by the system conditions.

3.2. Process-Based Mathematical Models

3.3. Performance Evaluation Criteria

- Total water yield ṁcond (kg/s), which reflects the overall production capacity of the system, defined as follows:

- 2.

- The energy rate per unit mass of freshwater produced, ԑ, which is defined as follows:

3.4. The Reference Case

4. Results of Sensitivity Analysis

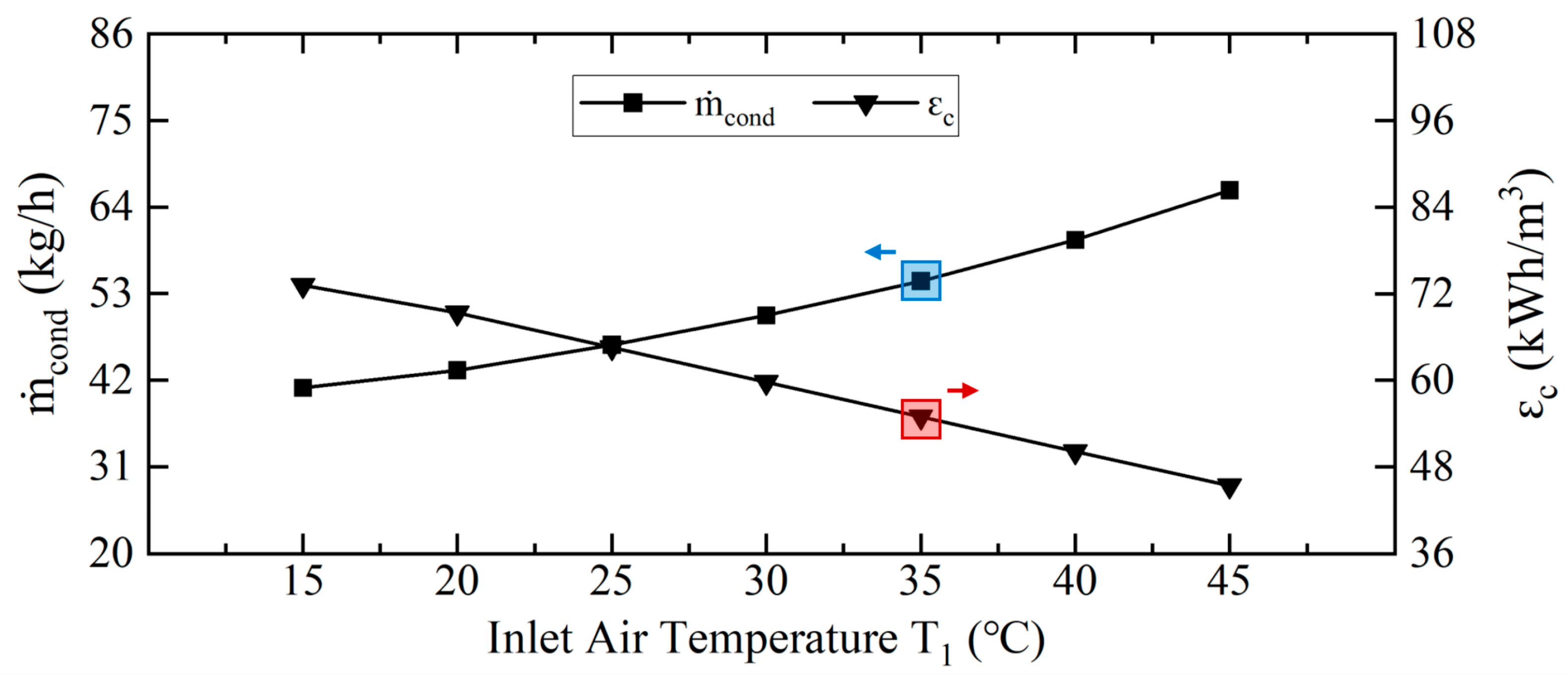

4.1. Effect of Inlet Air Temperature

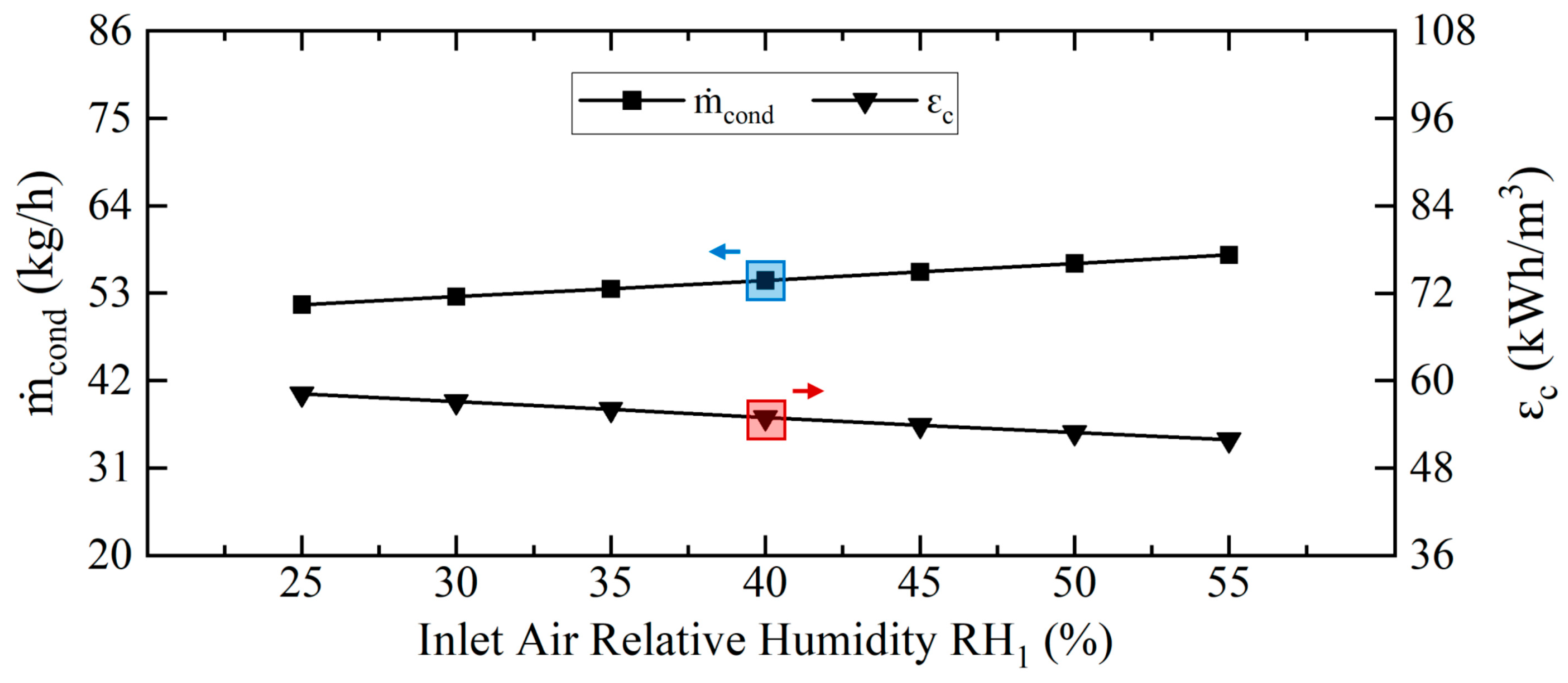

4.2. Effect of Inlet Air Relative Humidity

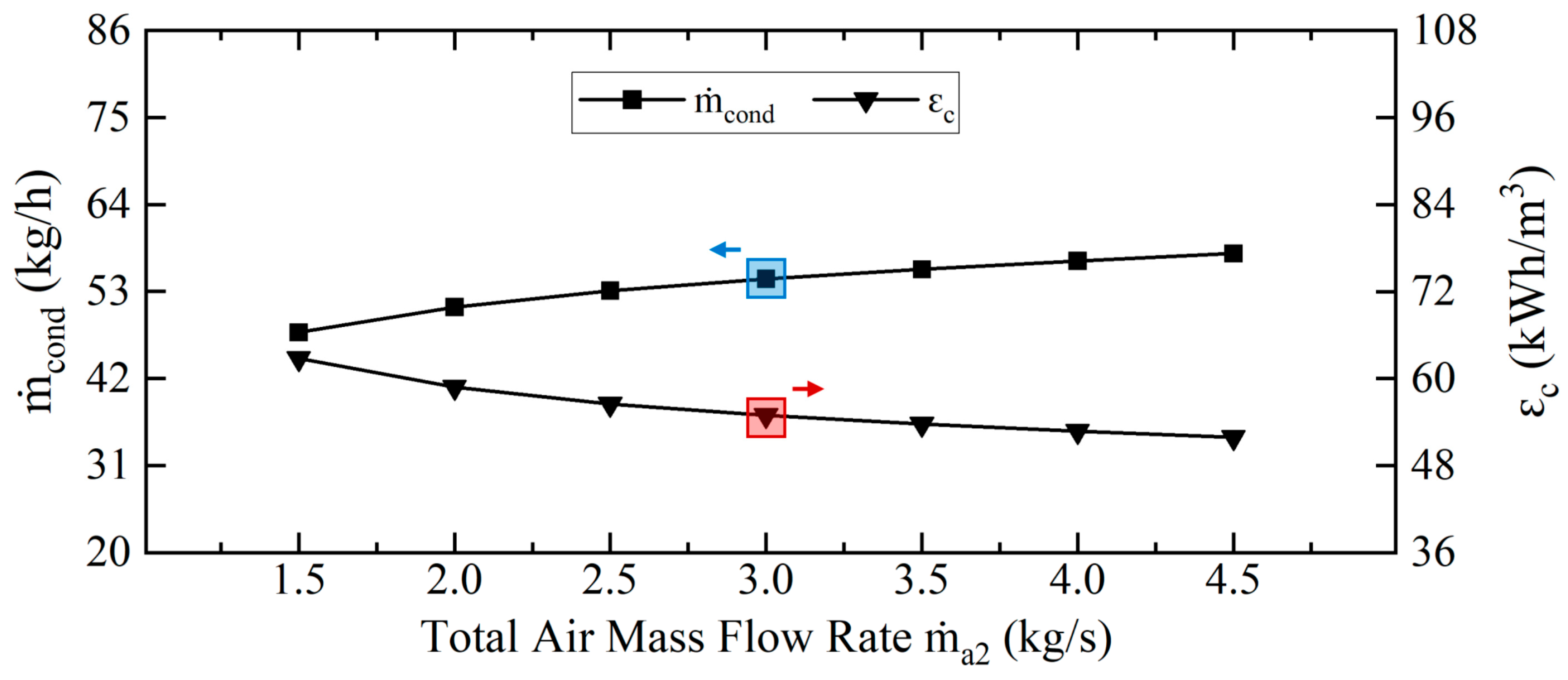

4.3. Effect of Total Air Mass Flow Rate

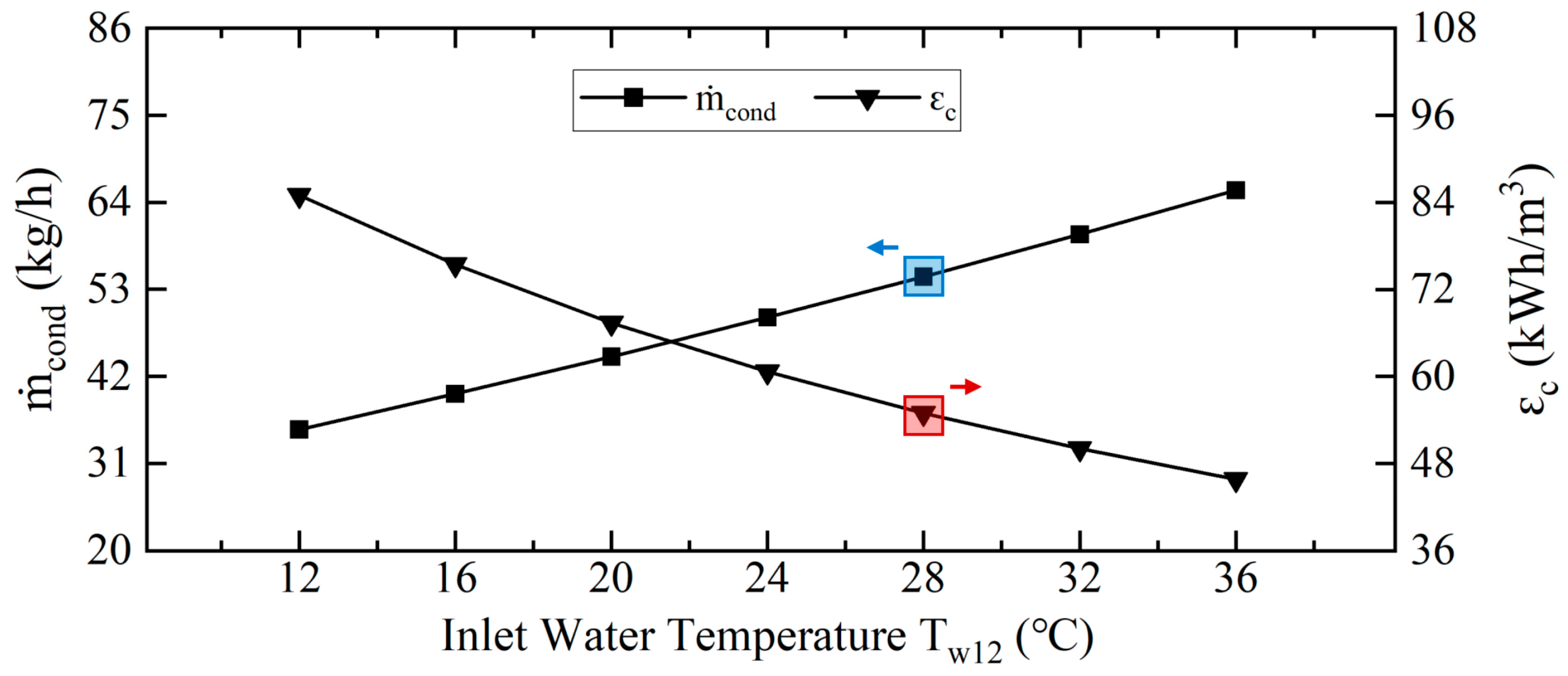

4.4. Effect of Inlet Water Temperature

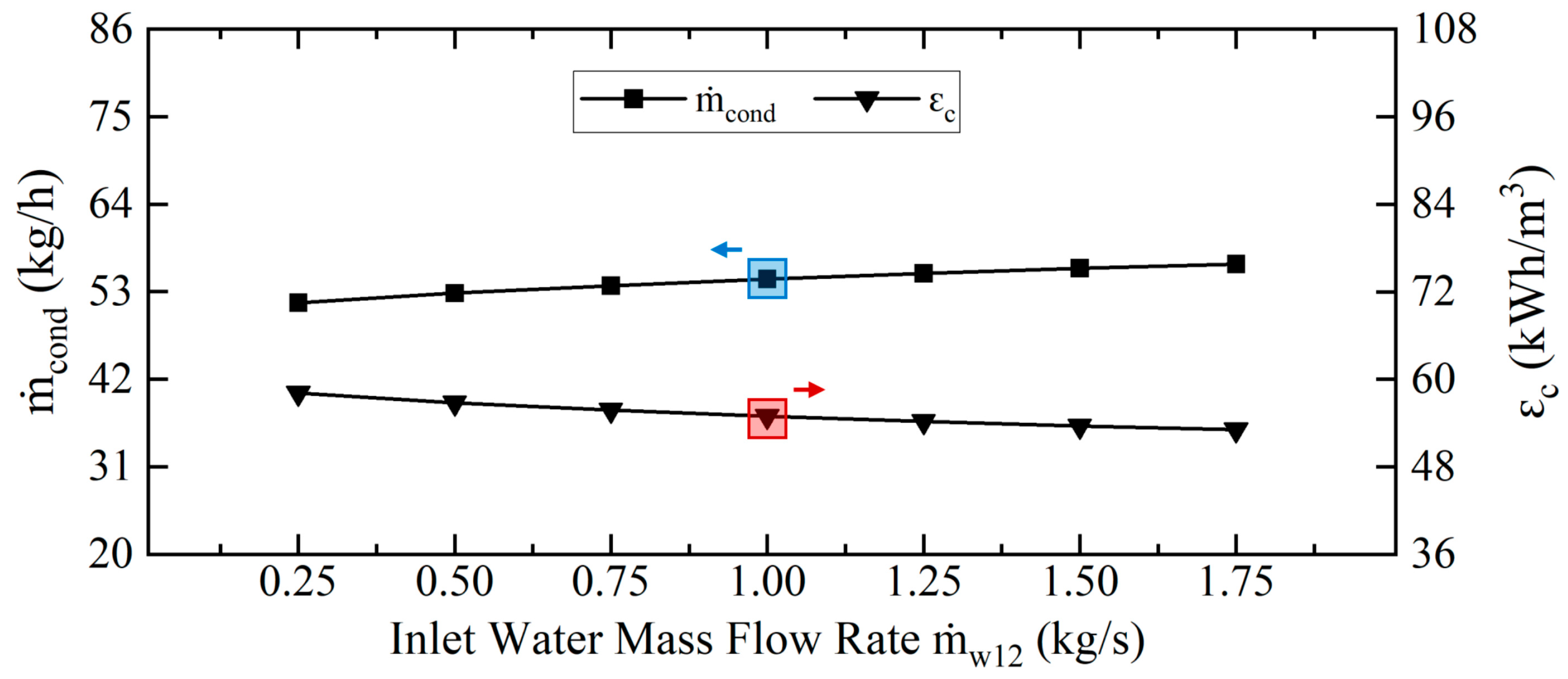

4.5. Effect of Inlet Water Mass Flow Rate

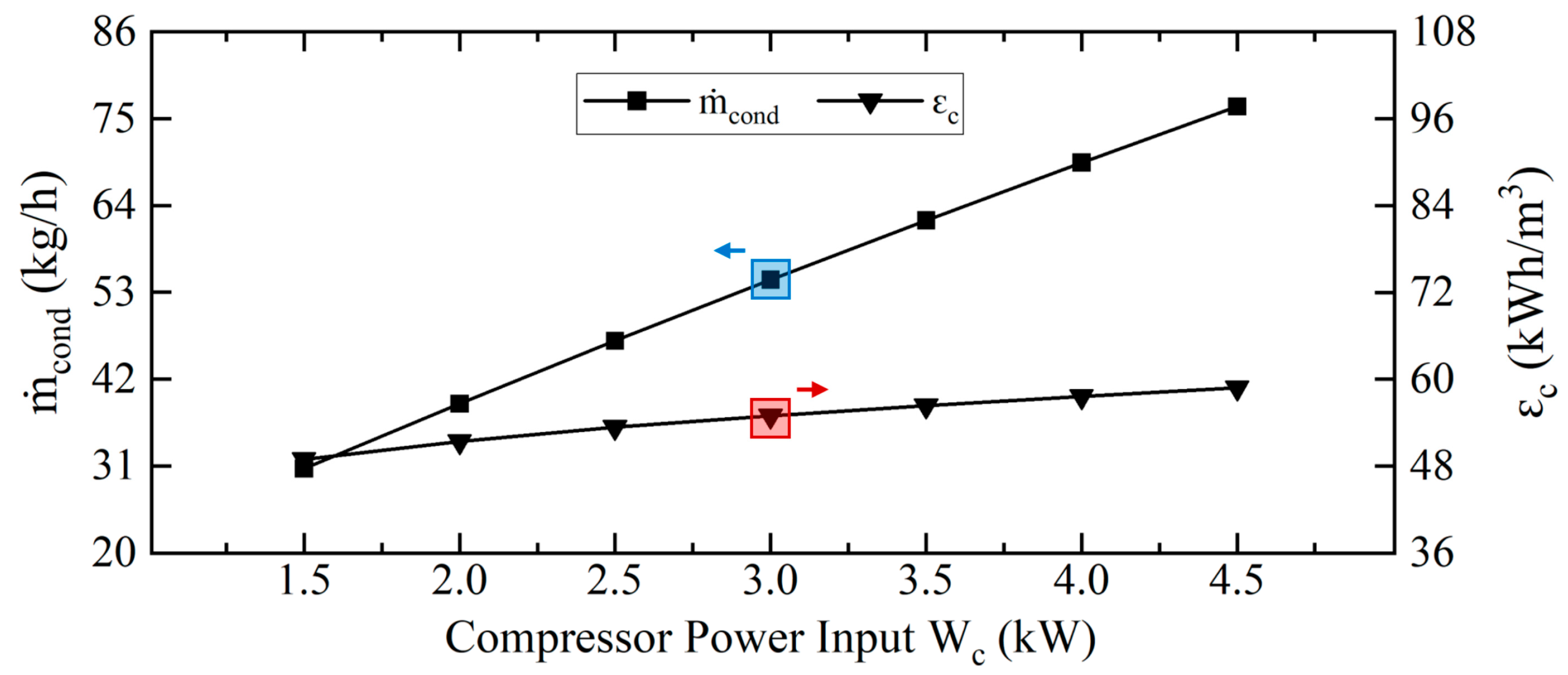

4.6. Effect of Compressor Power Input

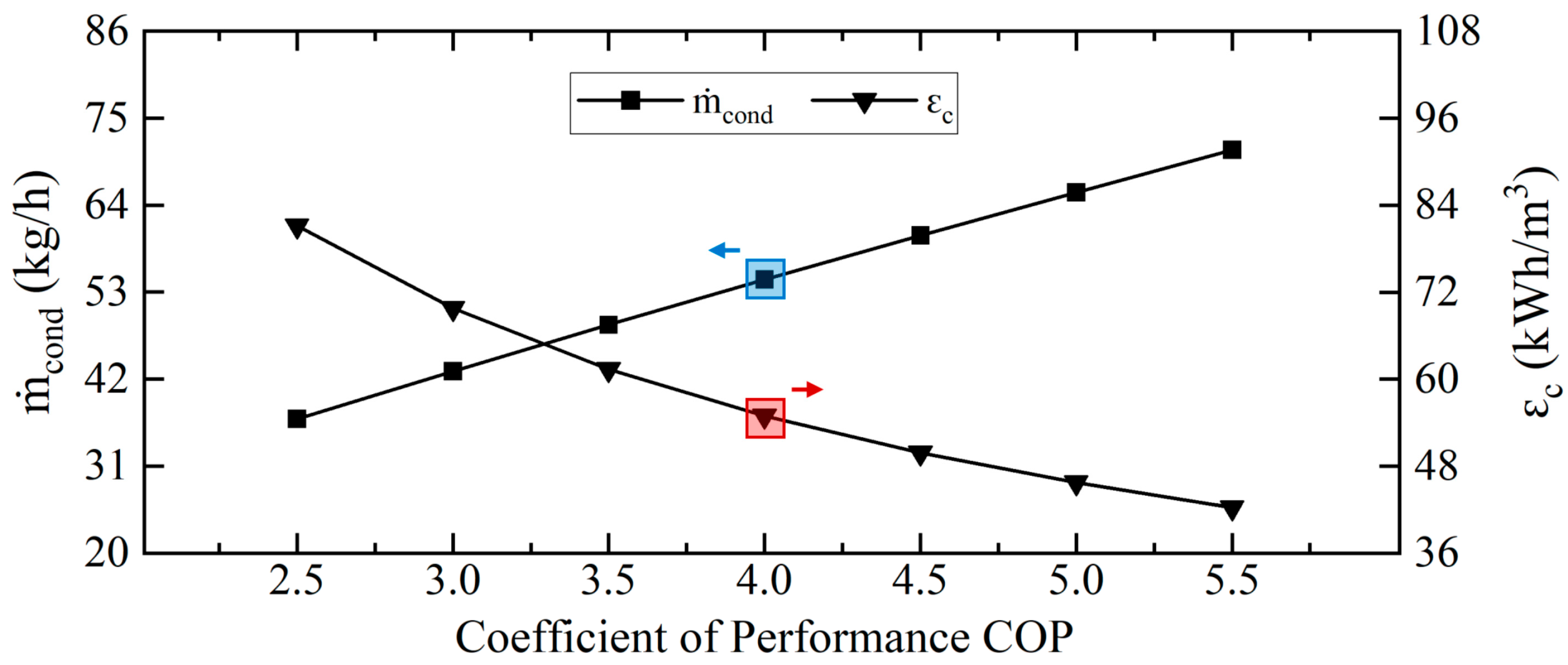

4.7. Effect of Coefficient of Performance

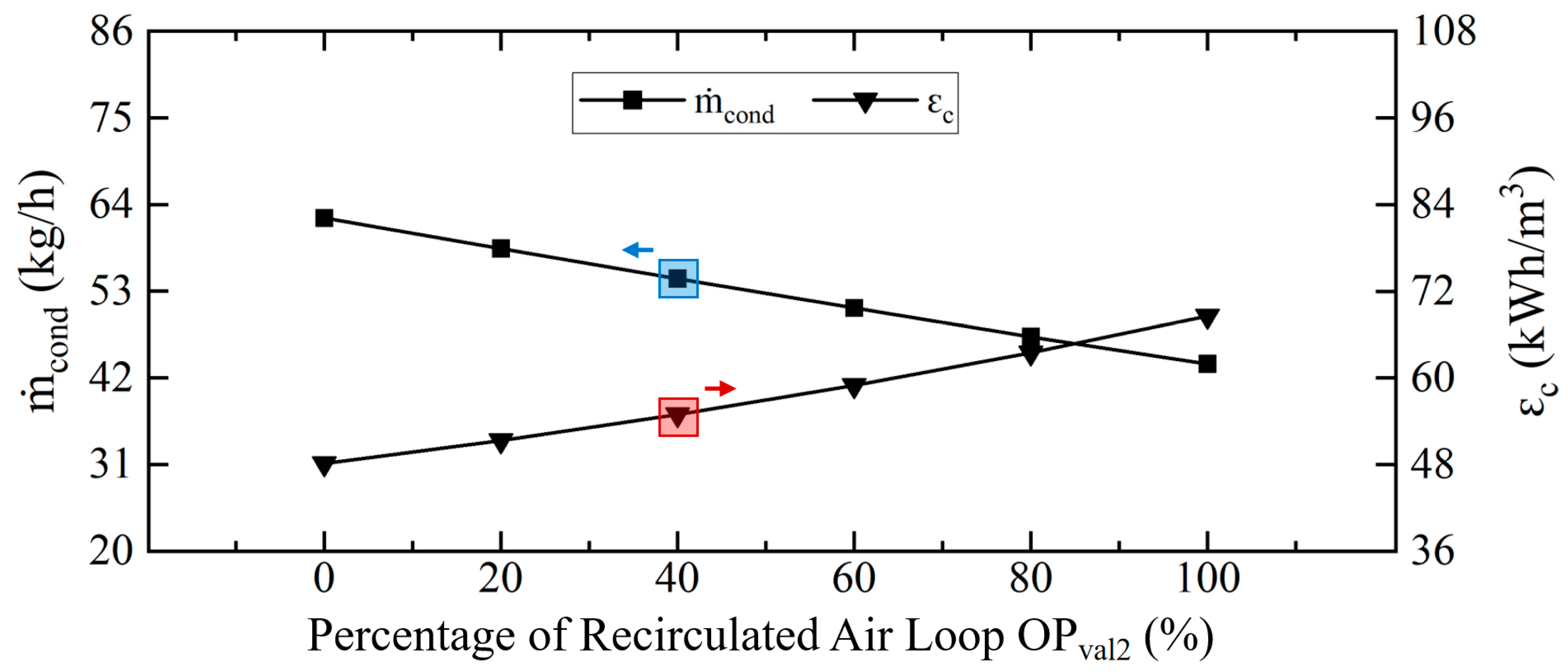

4.8. Effect of Percentage of Recirculated Air Loop

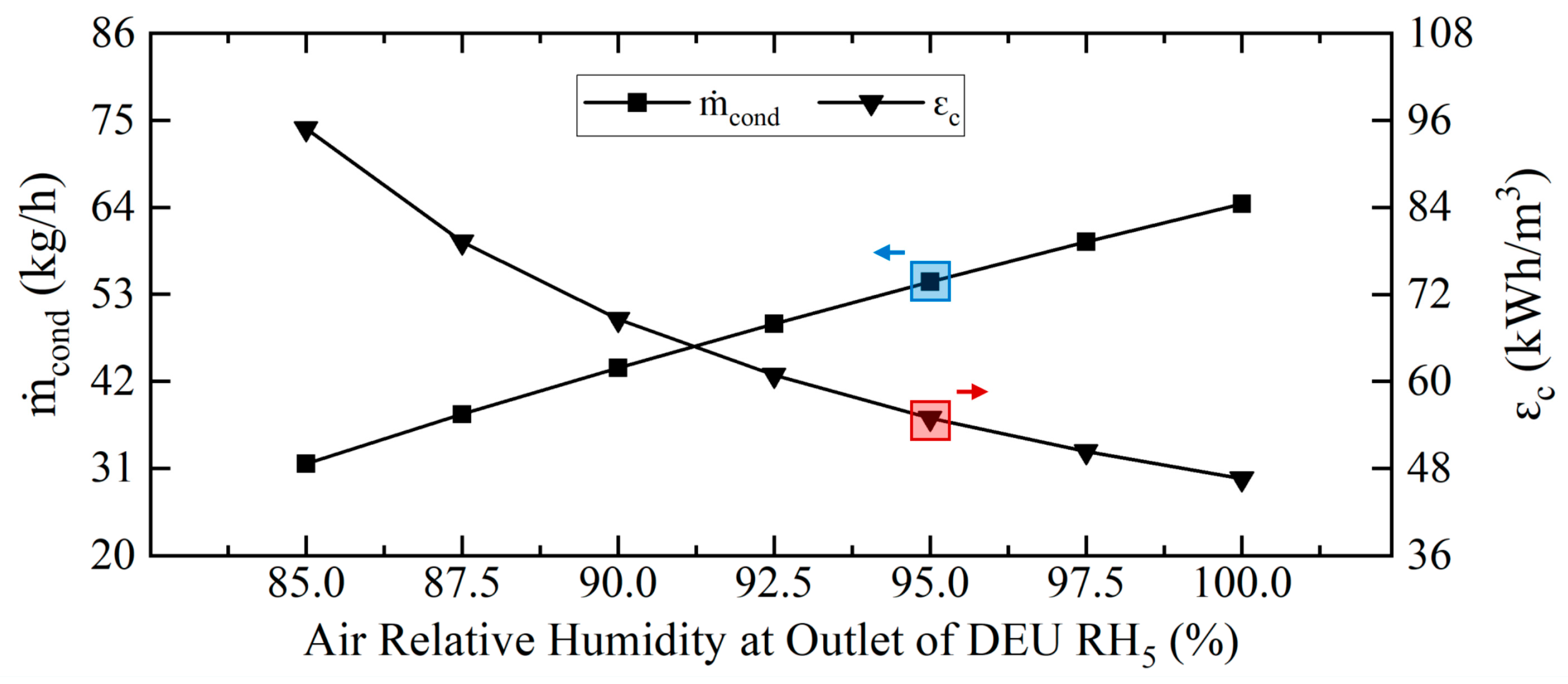

4.9. Effect of Air Relative Humidity at Outlet of DEU

5. Conclusions

- The increase in the ambient air temperature and the relative humidity of the inlet air can significantly improve the performance of the system (including increasing the total water yield and reducing the energy rate per unit mass of freshwater produced), with the effect of air temperature being the most significant, leading to an increase in the total water yield by up to 1.6 times and a reduction in the energy rate by up to 38%.

- Increasing the total air mass circulated through the system can improve the performance of the system, with water yield increasing by up to 21% and energy rate decreasing by up to 38%.

- The increase in the inlet water temperature can enhance heat transfer, reduce the air temperature drop, and increase the moisture content of the air inside the DEU, resulting in the water yield increasing by up to 1.8 times and the energy rate decreasing by up to 46%, while the increase in the inlet water flow rate has less of an impact on the performance of the system and can only slightly increase the water output.

- Increasing the compressor power or system COP can effectively increase the total water yield. An improvement in COP can enhance the efficiency of the VRU and enhance the condensation potential, with water yield increasing by up to 1.9 times and energy consumption per unit of freshwater reduced by up to 48%.

- An improvement in DEU performance, i.e., an increase in the relative humidity at the outlet of the DEU, would improve the system performance effectively. In other words, the design, the structure, and the operation of the DEU are key to system performance, with water yield increasing twofold and energy rate decreasing by up to 51%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | |

| A | Drenching water area (m2) |

| CHE | Condenser heat exchanger |

| CL | Closed loop |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| DEU | Direct evaporation unit |

| EHE | Evaporator heat exchanger |

| h | Specific enthalpy (kJ/kg) |

| hm | Convective mass-transfer coefficient (kg/(m2·s)) |

| HE1 | Cooling recovery heat exchanger |

| HE2 | Ambient air heat exchanger |

| L | Latent heat of vaporization (kJ/kg) |

| ṁ | Mass flow rate of fluid (kg/s) |

| OL | Open loop |

| OP | Valve opening, (%) |

| P | Pressure (Pa) |

| Q | Heat (kW) |

| RH | Air relative humidity (%) |

| T | Temperature, (°C) |

| VRU | Vapor compression refrigeration unit |

| Val | Valve |

| W | Power input (kW) |

| Special characters | |

| ω | Absolute humidity of the air (kg/kg) |

| ε | Efficiency (kWh/m3) |

| Subscripts | |

| a | Air |

| c | Compressor |

| cond | Condensate water |

| evap | Evaporation |

| f | Fan |

| in | Inlet |

| out | Outlet |

| v | Vapor |

| w | Water |

References

- Martínez-Alvarez, V.; Martin-Gorriz, B.; Soto-García, M. Seawater desalination for crop irrigation—A review of current experiences and revealed key issues. Desalination 2016, 381, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, X. Seawater Desalination System Driven by Sustainable Energy: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2024, 17, 5706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, L.; Xu, N.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z. Photothermal fabrics for solar-driven seawater desalination. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 150, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.W., II; Van de Ven, J.D. A Comparison of Power Take-Off Architectures for Wave-Powered Reverse Osmosis Desalination of Seawater with Co-Production of Electricity. Energies 2023, 16, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adityawarman, D.; Lugito, G.; Kawi, S.; Wenten, I.G.; Khoiruddin, K. Advancements and future trends in nanostructured membrane technologies for seawater desalination. Desalination 2025, 597, 118390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacha, H.B.; Abdullah, A.S.; Aljaghtham, M.; Salama, R.S.; Abdelgaied, M.; Kabeel, A.E. Thermo-Economic Assessment of Photovoltaic/Thermal Pan-Els-Powered Reverse Osmosis Desalination Unit Combined with Preheating Using Geothermal Energy. Energies 2023, 16, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, O.; Ali, R.; Hodgson, G.; Smith, D.; Qureshi, E.; McFarlane, D.; Campos, E.; Zarzo, D. Feasibility assessment of desalination application in Australian traditional agriculture. Desalination 2015, 364, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, M.; Alsarayreh, A.A.; Rashid, F.L.; Sowgath, M.T.; Alsadaie, S.; Ruiz-García, A.; Khayet, M.; Ghaffour, N.; Mujtaba, I.M. Hybrid membrane and thermal seawater desalination processes powered by fossil fuels: A comprehensive review, future challenges and prospects. Desalination 2024, 583, 117694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, H.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Atmospheric Water Harvesting: A Review of Material and Structural Designs. ACS Mater. Lett. 2020, 2, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Liu, Y.; Ren, H.; Gong, Z.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Guo, L.; Chen, R.; Wei, J.; Dai, Q.; et al. N, S-carbon quantum dots as inhibitor in pickling process of heat exchangers for enhanced performance in multi-stage flash seawater desalination. Desalination 2024, 589, 117969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Gu, R.; Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, S. Seawater interfacial evaporation in composite gel enables photovoltaic cooling, simultaneous seawater desalination, and enhanced uranium extraction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2420651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.W.; Burhan, M.; Ybyraiymkul, D.; Ng, K.C. Desalination Processes’ Efficiency and Future Roadmap. Entropy 2019, 21, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenvi, S.S.; Isloor, A.M.; Ismail, A.F. A review on RO membrane technology: Developments and challenges. Desalination 2015, 368, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Su, C.; Zhan, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Sun, C.; Kong, Y.; Yang, L.; et al. Thermodynamic and economic analyses of nuclear power plant integrating with seawater desalination and hydrogen production for peak shaving. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 82, 1372–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; An, M.; Kim, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Khaorapapong, N.; Yuan, Z. Bio-inspired 3D architectured aerogel evaporator for highly efficient solar seawater desalination. Nano Energy 2025, 137, 110781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Koo, J.; Lee, S. System Dynamics Modeling of Scale Formation in Membrane Distillation Systems for Seawater and RO Brine Treatment. Membranes 2024, 14, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Khan, B.; Gu, H.; Christofides, P.D.; Cohen, Y. Modeling UF fouling and backwash in seawater RO feedwater treatment using neural networks with evolutionary algorithm and Bayesian binary classification. Desalination 2021, 513, 115129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashtoush, B.; Alshoubaki, A. Atmospheric water harvesting: A review of techniques, performance, renewable energy solutions, and feasibility. Energy 2023, 280, 128186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wong, P.W.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Z.; An, A.K. Transforming Ti3C2Tx MXene’s intrinsic hydrophilicity into superhydrophobicity for efficient photothermal membrane desalination. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ho, D.T.; Sheng, G.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, L.; Schwingenschlögl, U.; et al. An Ultrahigh-Flux Nanoporous Graphene Membrane for Sustainable Seawater Desalination using Low-Grade Heat. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Wen, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Fan, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, L.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. Alkadiyne–Pyrene Conjugated Frameworks with Surface Exclusion Effect for Ultrafast Seawater Desalination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 3075–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.-Z. Fouling resistance improvement with a new superhydrophobic electrospun PVDF membrane for seawater desalination. Desalination 2020, 476, 114246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, R.; Hwang, Y. Reviews of atmospheric water harvesting technologies. Energy 2020, 201, 117630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Fu, H.; Chen, J. Comprehensive review on atmospheric water harvesting technologies. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chao, L.C.; Pan, A.; Ho, T.C.; Lin, K.; Tso, C.Y. Study of the relative humidity effects on the water condensation performance of adsorption-based atmospheric water harvesting using passive radiative condensers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 244, 122702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, O.; Wikramanayake, E.D.; Bahadur, V. Modeling humid air condensation in waste natural gas-powered atmospheric water harvesting systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 118, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Xiang, C.; Poredoš, P.; Wang, R. Hygroscopic Porous Polymer for Sorption-Based Atmospheric Water Harvesting. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2204724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Pan, T.; Lei, Q.; Dong, X.; Cheng, Q.; Han, Y. A Roadmap to Sorption-Based Atmospheric Water Harvesting: From Molecular Sorption Mechanism to Sorbent Design and System Optimization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 6542–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entezari, A.; Esan, O.C.; Yan, X.; Wang, R.; An, L. Sorption-Based Atmospheric Water Harvesting: Materials, Components, Systems, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2210957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; Hua, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, J. Global potential of continuous sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting Global potential of continuous sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting. iScience 2025, 28, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huo, E. Opportunities and challenges of seawater desalination technology. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 960537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Namazi, M.A.; ud Din, M.A.; Ershath, M.M.; Mansour, A. Sustainable seawater desalination: Current status, environmental implications and future expectations. Desalination 2022, 540, 116022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Shi, W.; Guo, Y.; Guan, W.; Lei, C.; Yu, G. Materials engineering for atmospheric water harvesting: Progress and perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2110079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hua, L.; Li, C.; Wang, R. Atmospheric water harvesting: Critical metrics and challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 4867–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.J. Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, A.R.; Welch, T.; Hundy, G.F. Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning, 4th ed.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katinas, C.; d’Entremont, B.; Ray, W.; Willis, M.; Reichardt, T. Assessing parallel path cooling tower performance via artificial neural networks. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2023, 192, 109993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, P.; Serrano, J.M.; Roca, L.; Palenzuela, P.; Lucas, M.; Ruiz, J. A comparative study on predicting wet cooling tower performance in combined cooling systems for heat rejection in CSP plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 253, 123718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input of the Model | |||

| Parameter | Description | Unit | Value |

| T1 | Inlet air temperature | °C | 35 |

| RH1 | Inlet air relative humidity | % | 40 |

| ṁa2 | Total air mass flow rate | kg/s | 3 |

| RH5 | Assumed air relative humidity at outlet of DEU | % | 95 |

| Tw12 | Inlet water temperature (DEU) | °C | 28 |

| ṁw12 | Inlet water mass flow rate (DEU) | kg/s | 1 |

| OPval2 | The percentage of valve opening of valve Val2 | % | 40 |

| Wc | Compressor power input | kW | 3 |

| Wf | Fan power input | kW | 1.5 |

| COP | Coefficient of performance of the refrigeration unit | − | 4 |

| Results of the Reference Case | |||

| Parameter | Description | Unit | Value |

| ṁevap | Evaporation rate (DEU) | kg/h | 25.62 |

| ṁw14 | Condensation water mass flow rate (HE1) | kg/h | 4.54 |

| ṁw15 | Condensation water mass flow rate (EHE) | kg/h | 50.06 |

| ṁcond | The total water yield | kg/h | 54.60 |

| ԑc | The energy rate per unit mass of freshwater produced (compressor) | kWh/m3 | 54.94 |

| ԑc+f | The energy rate per unit mass of freshwater produced (compressor and fan) | kWh/m3 | 82.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huo, Y.; Hu, E.; Wang, J. Modeling and Performance Assessment of a NeWater System Based on Direct Evaporation and Refrigeration Cycle. Energies 2026, 19, 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020468

Huo Y, Hu E, Wang J. Modeling and Performance Assessment of a NeWater System Based on Direct Evaporation and Refrigeration Cycle. Energies. 2026; 19(2):468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020468

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuo, Yilin, Eric Hu, and Jay Wang. 2026. "Modeling and Performance Assessment of a NeWater System Based on Direct Evaporation and Refrigeration Cycle" Energies 19, no. 2: 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020468

APA StyleHuo, Y., Hu, E., & Wang, J. (2026). Modeling and Performance Assessment of a NeWater System Based on Direct Evaporation and Refrigeration Cycle. Energies, 19(2), 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020468