Reservoir Characteristics and Productivity Controlling Factors of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations in the Lu203–Yang101 Well Block, Southern Sichuan Basin, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

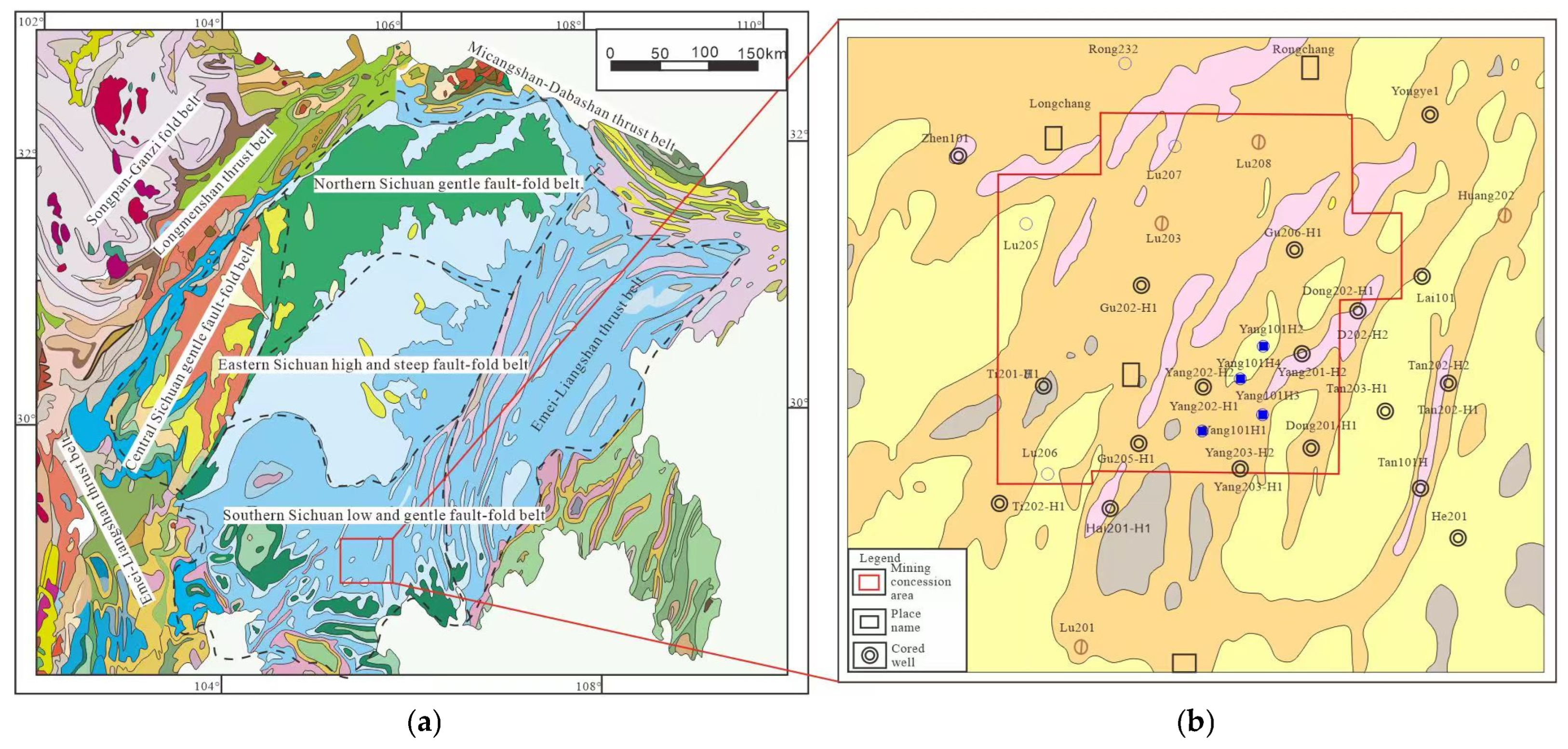

2. Geological Setting

3. Samples and Methods

3.1. Samples

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. TOC

3.2.2. Mineral Composition Testing

3.2.3. Pore Structure Observation

Direct Observation

Indirect Characterization

4. Results

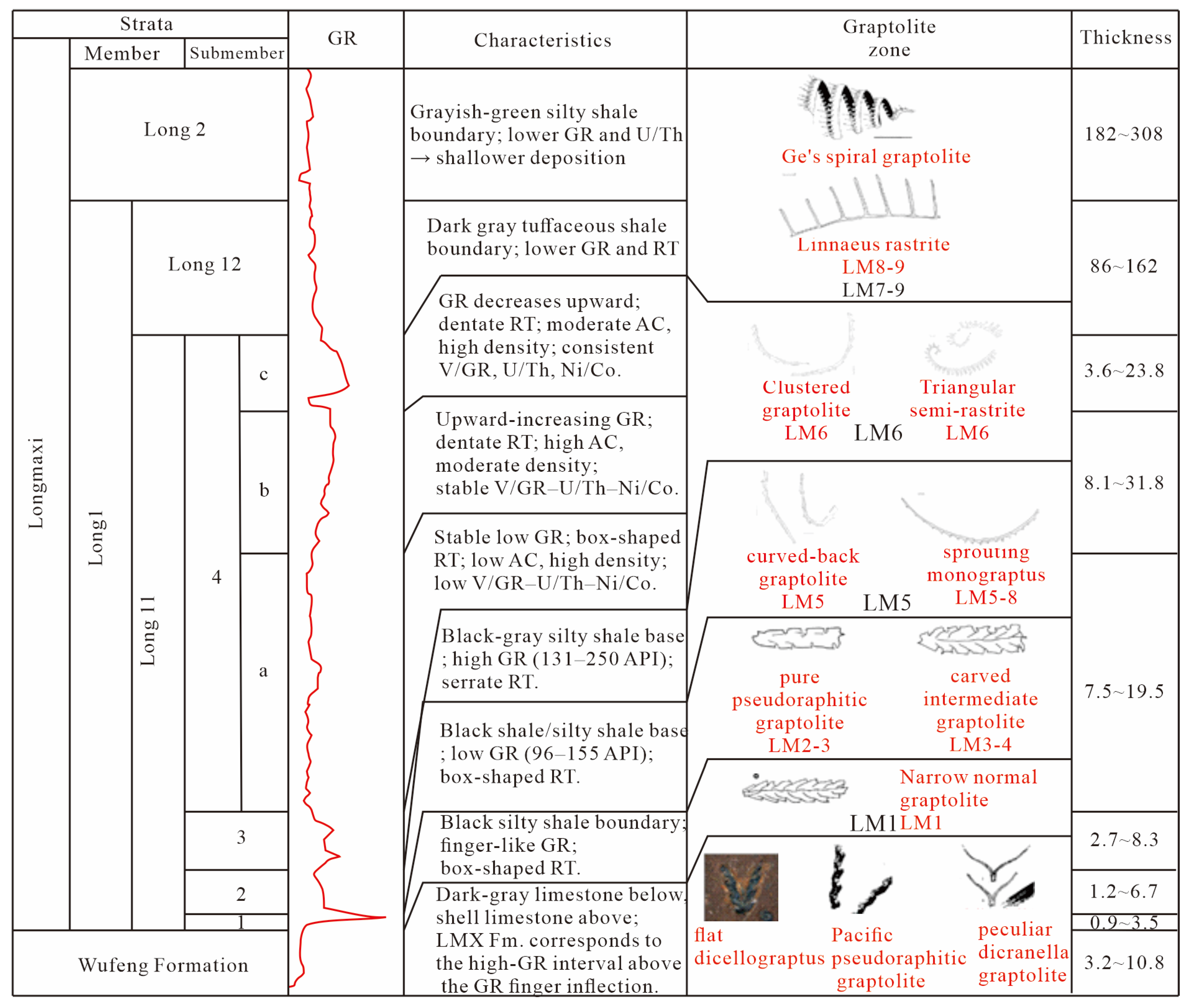

4.1. Macroscopic Reservoir Characteristics

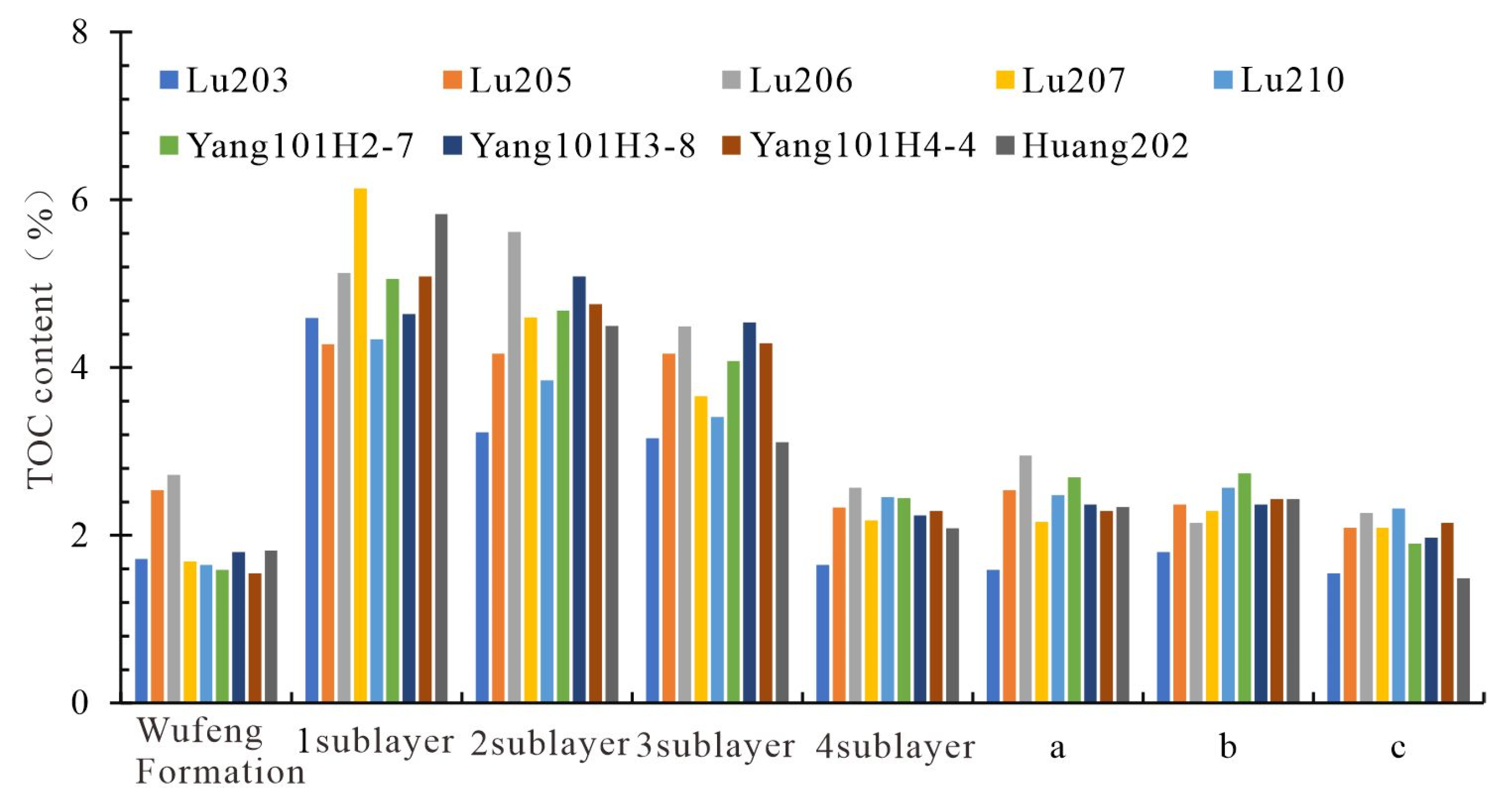

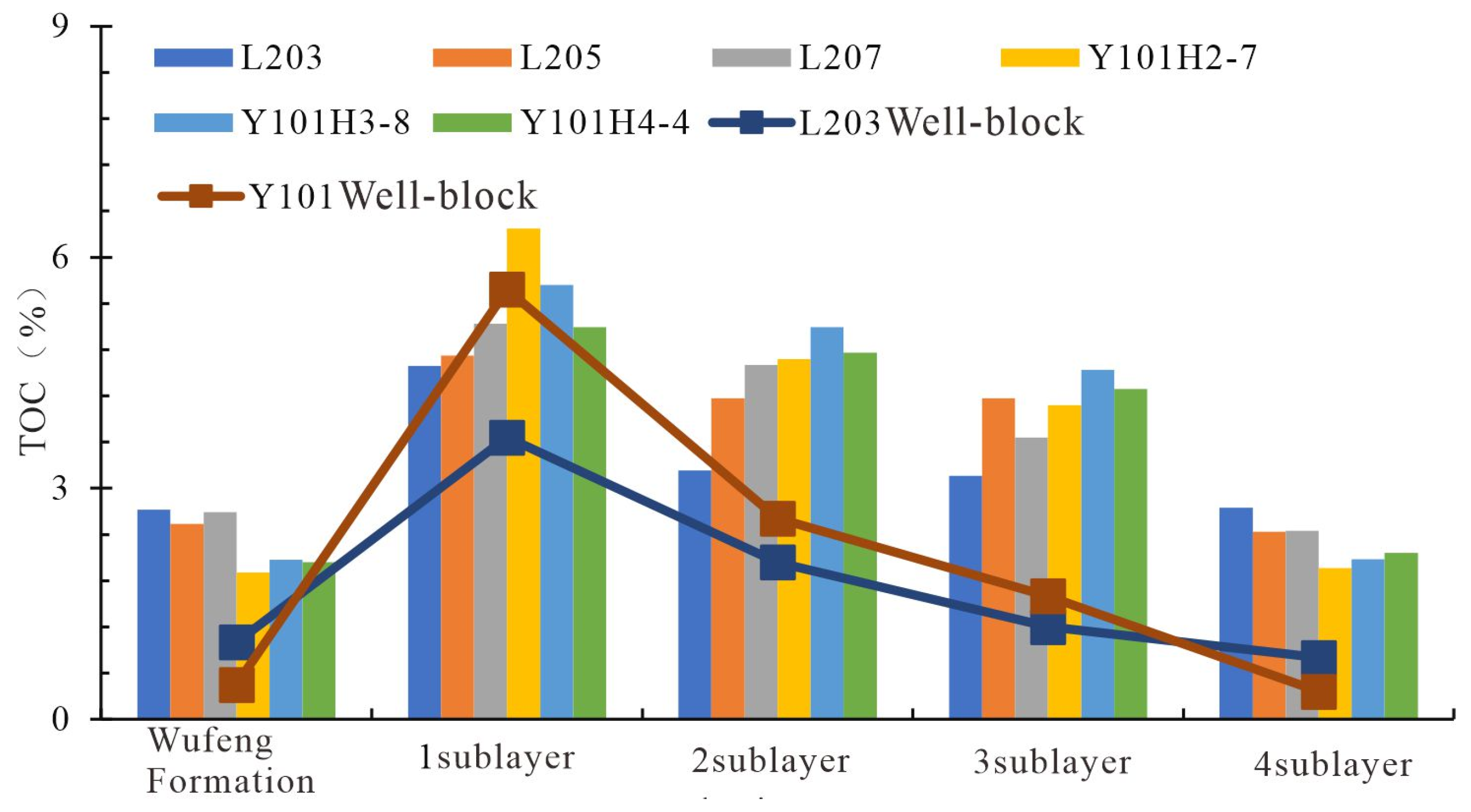

4.1.1. Organic Matter Abundance

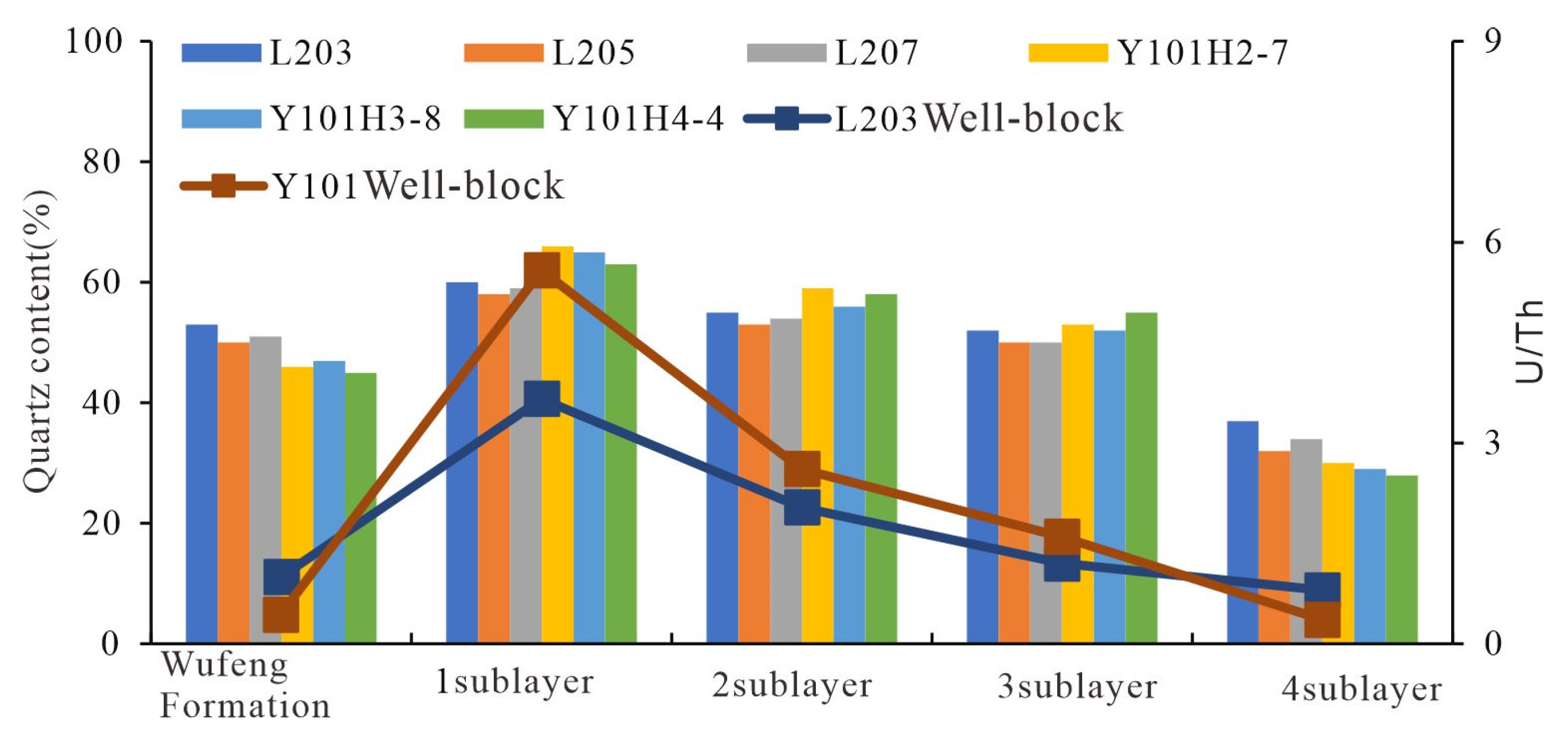

4.1.2. Mineral Composition

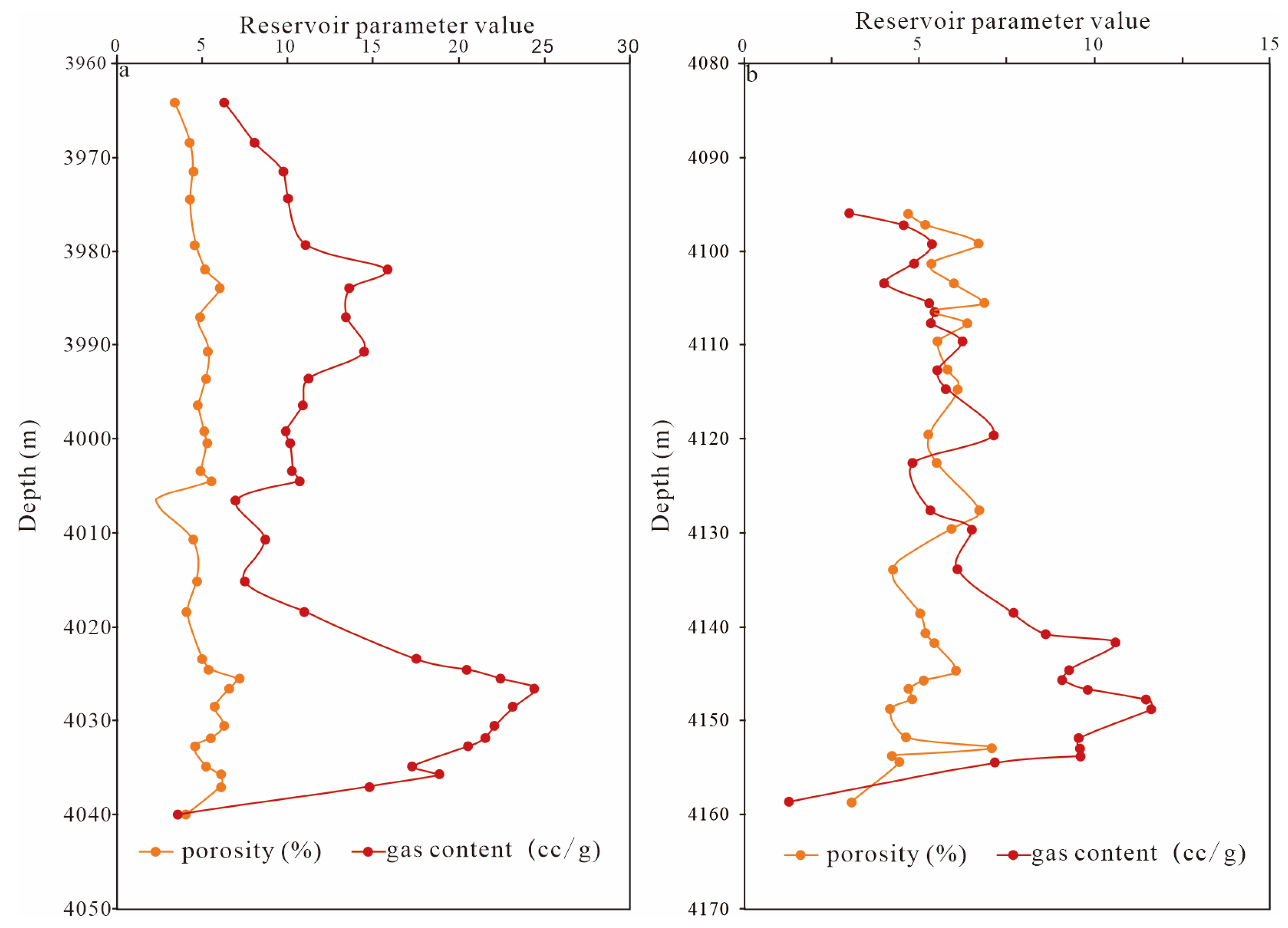

4.1.3. Porosity and Gas Content

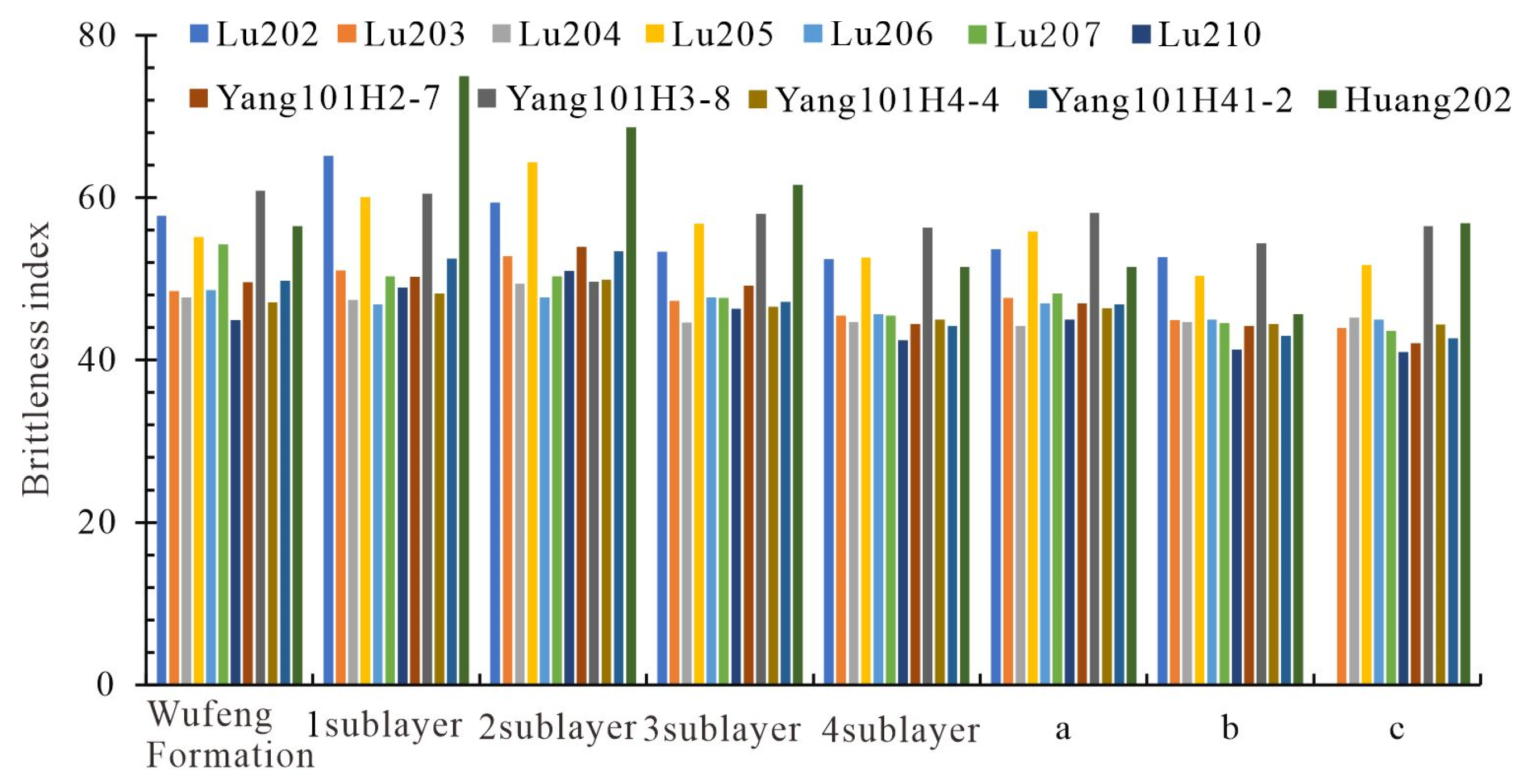

4.1.4. Brittleness and Fracability

4.2. Microscopic Reservoir Characteristics

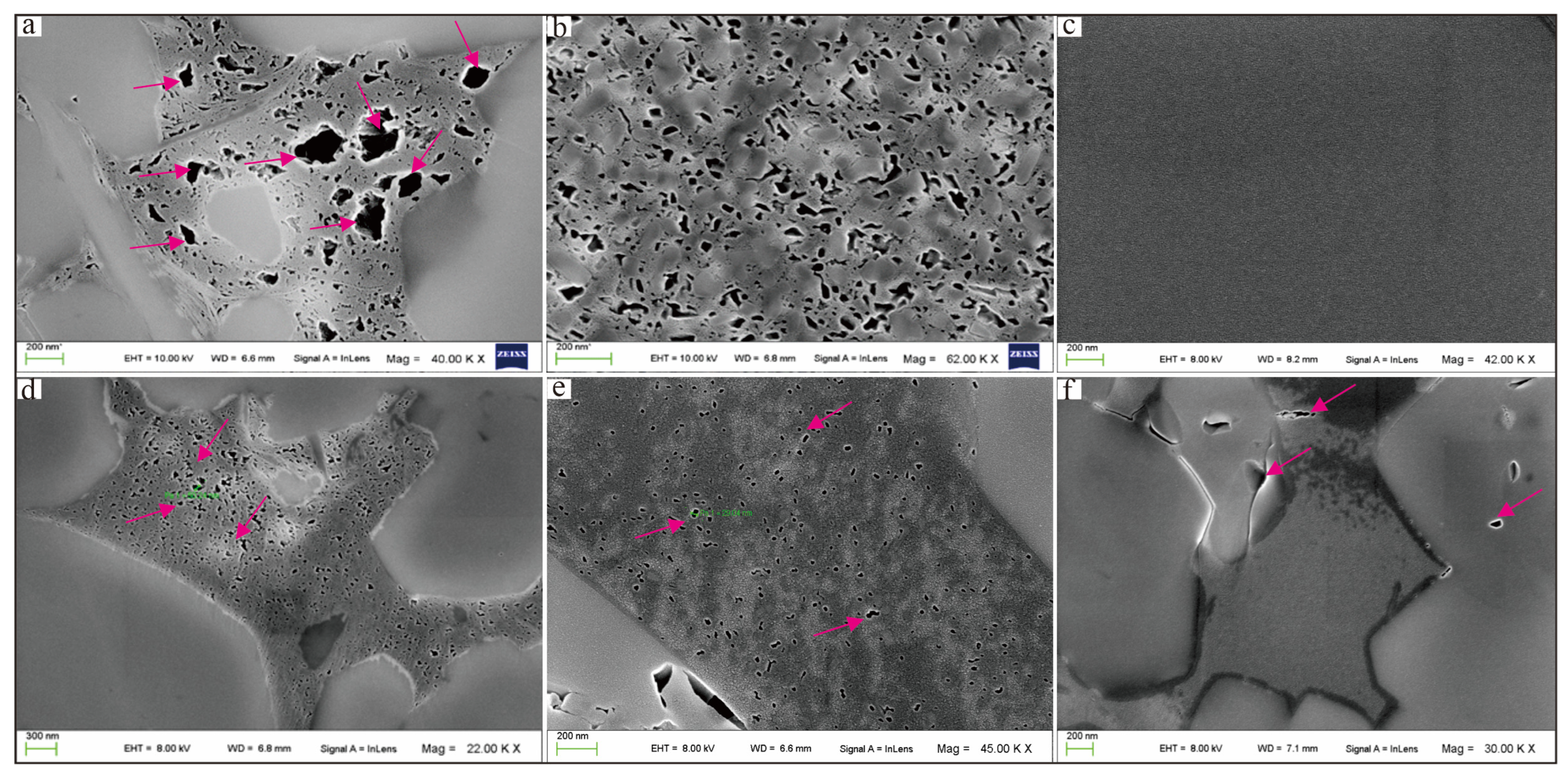

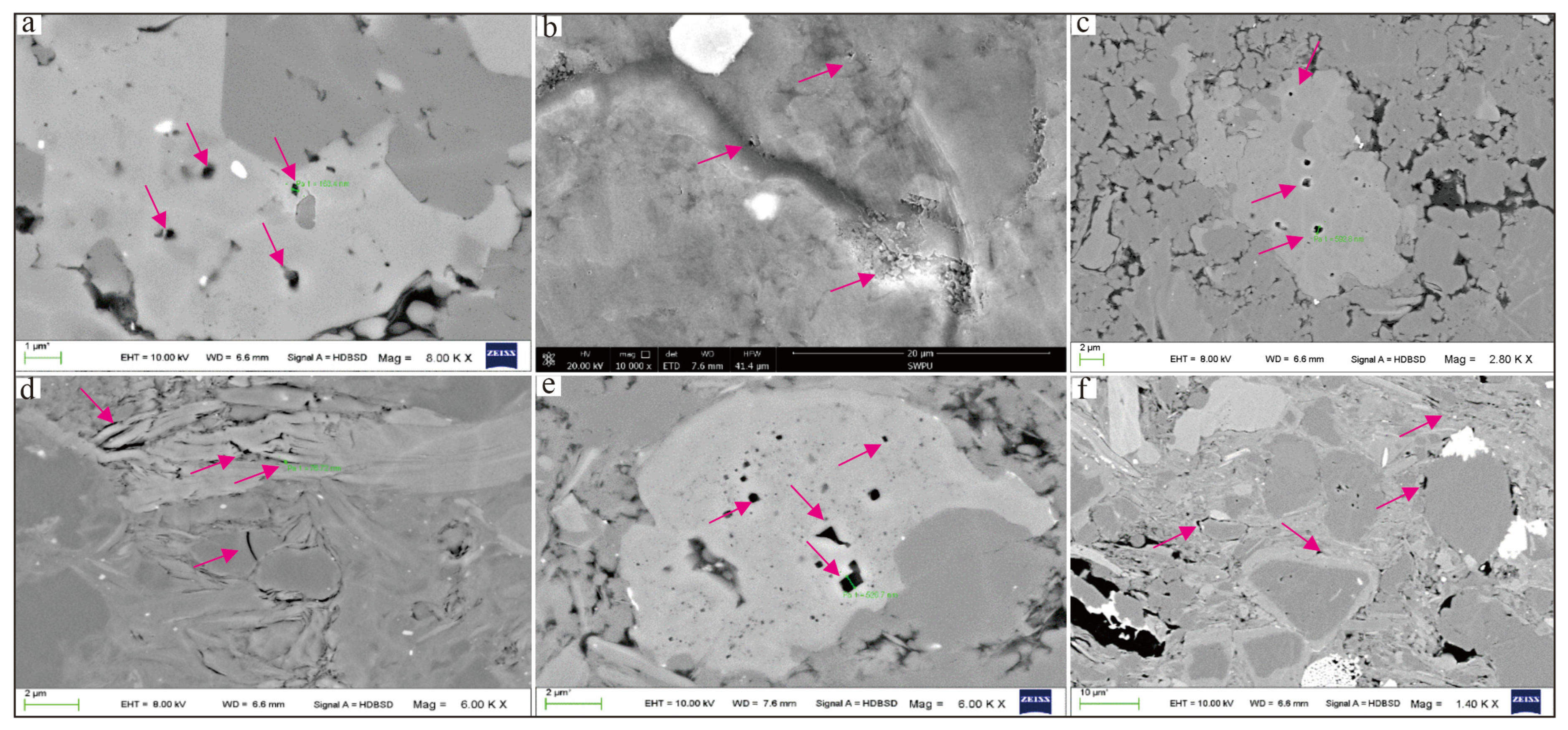

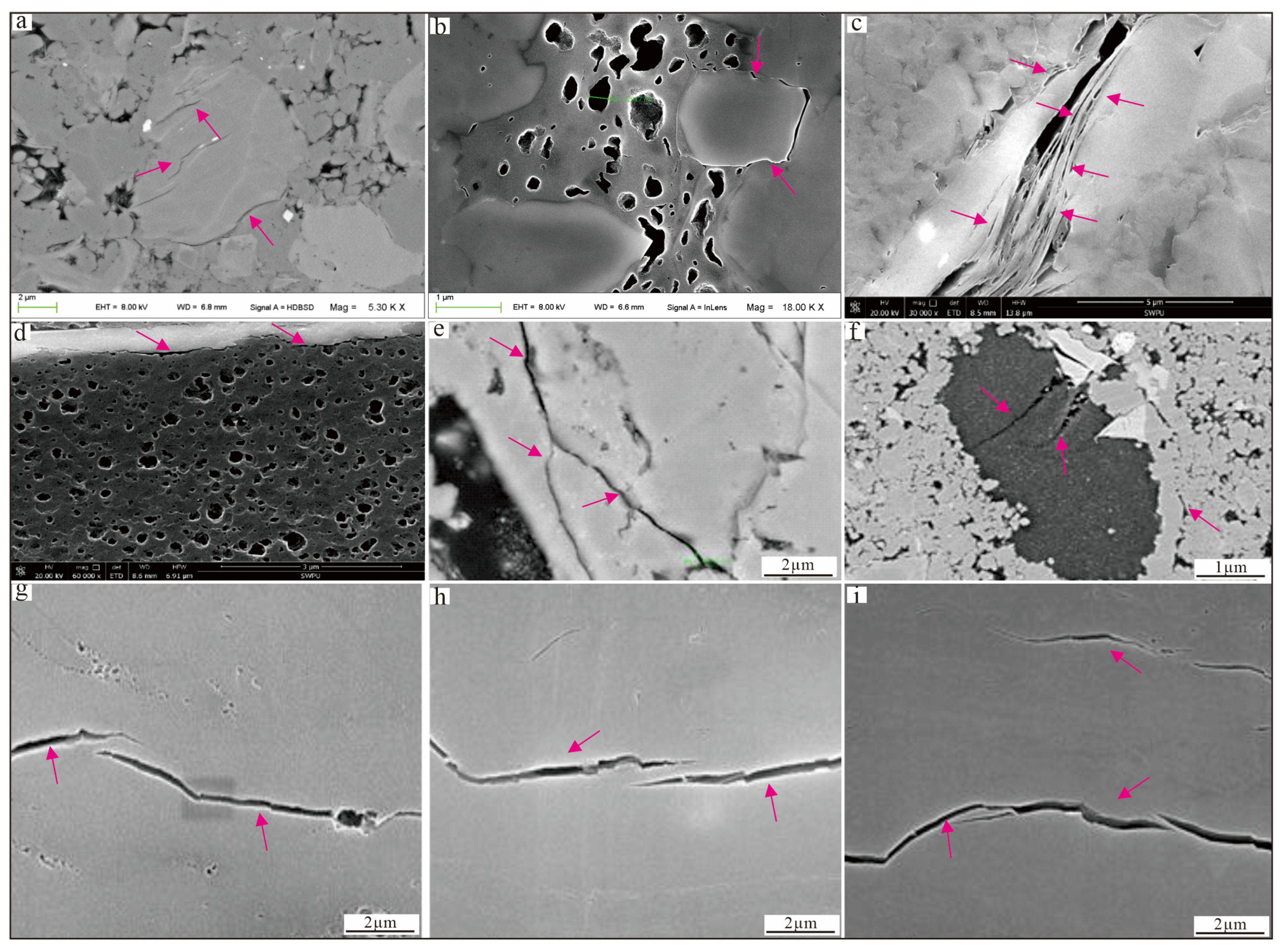

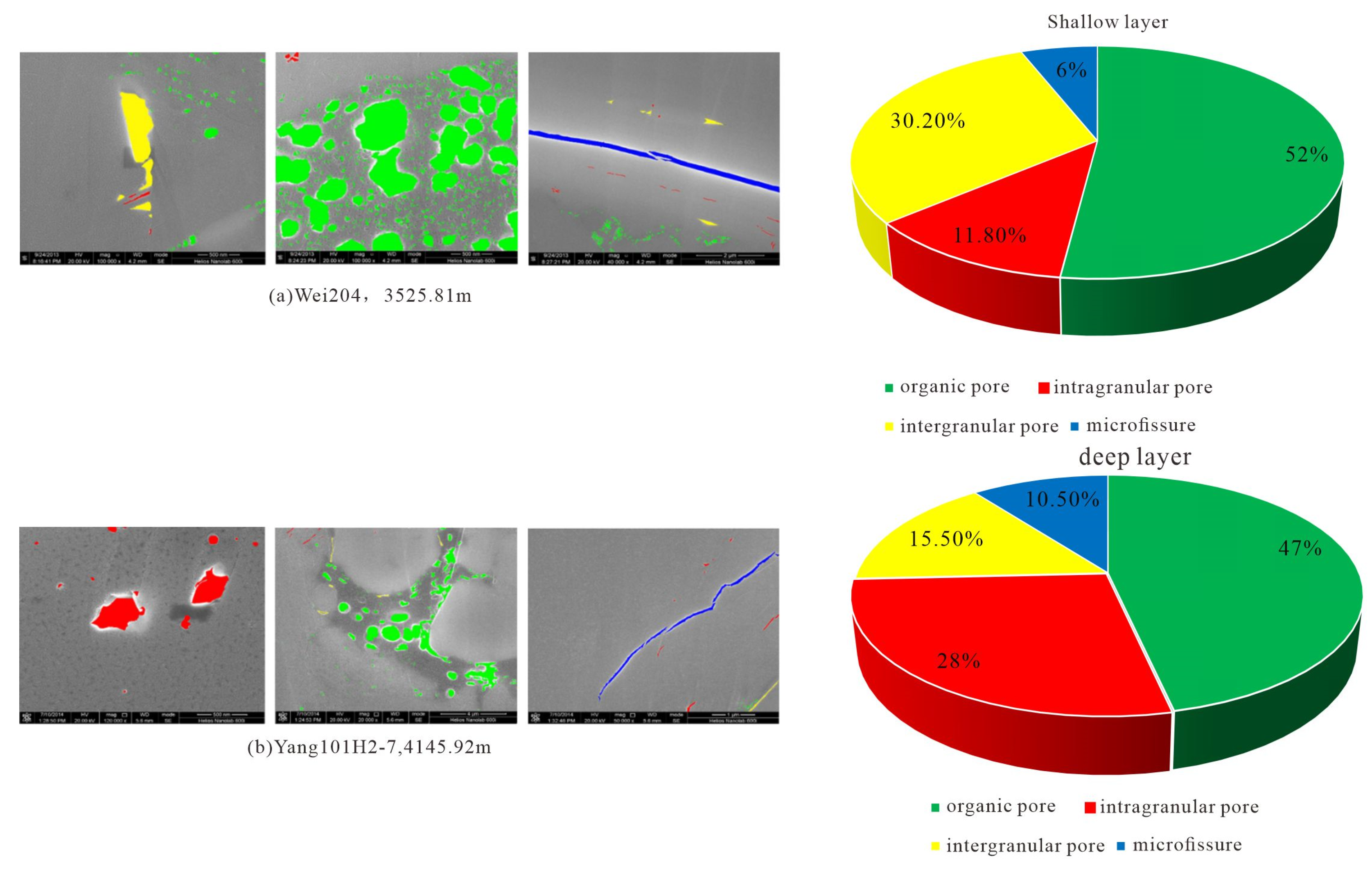

4.2.1. Types and Characteristics of Reservoir Space

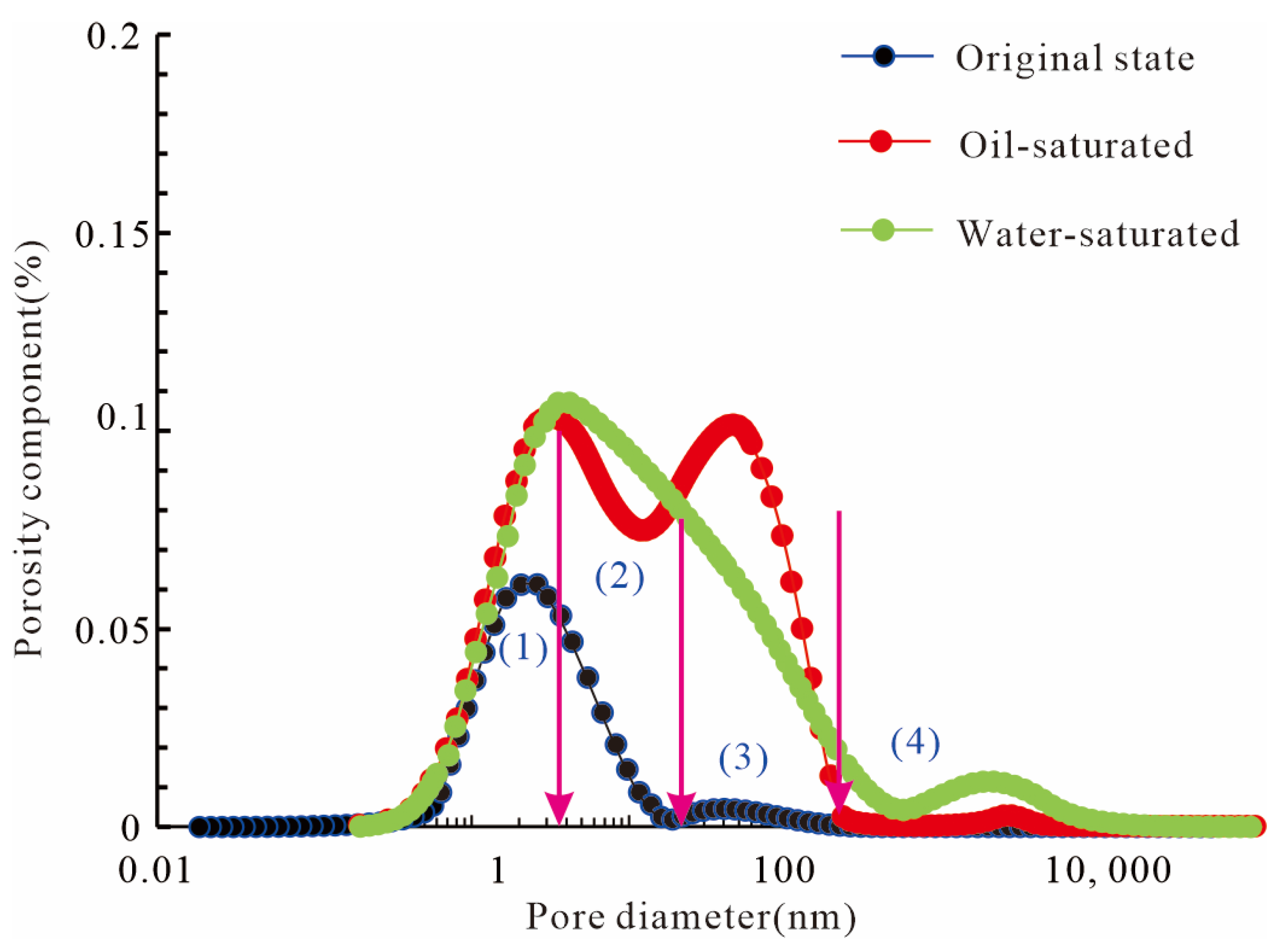

4.2.2. Quantitative Pore Characterization and Pore Size Distribution

4.3. Shale Reservoir Distribution

4.3.1. Vertical Distribution of Reservoirs

4.3.2. Lateral Distribution of Reservoirs

4.3.3. Planar Distribution of Reservoirs

5. Discussion

5.1. A Comparison of Deep vs. Shallow Shale-Reservoir Pore Structure

5.2. Main Controlling Factors for High Productivity in Shale Gas Wells

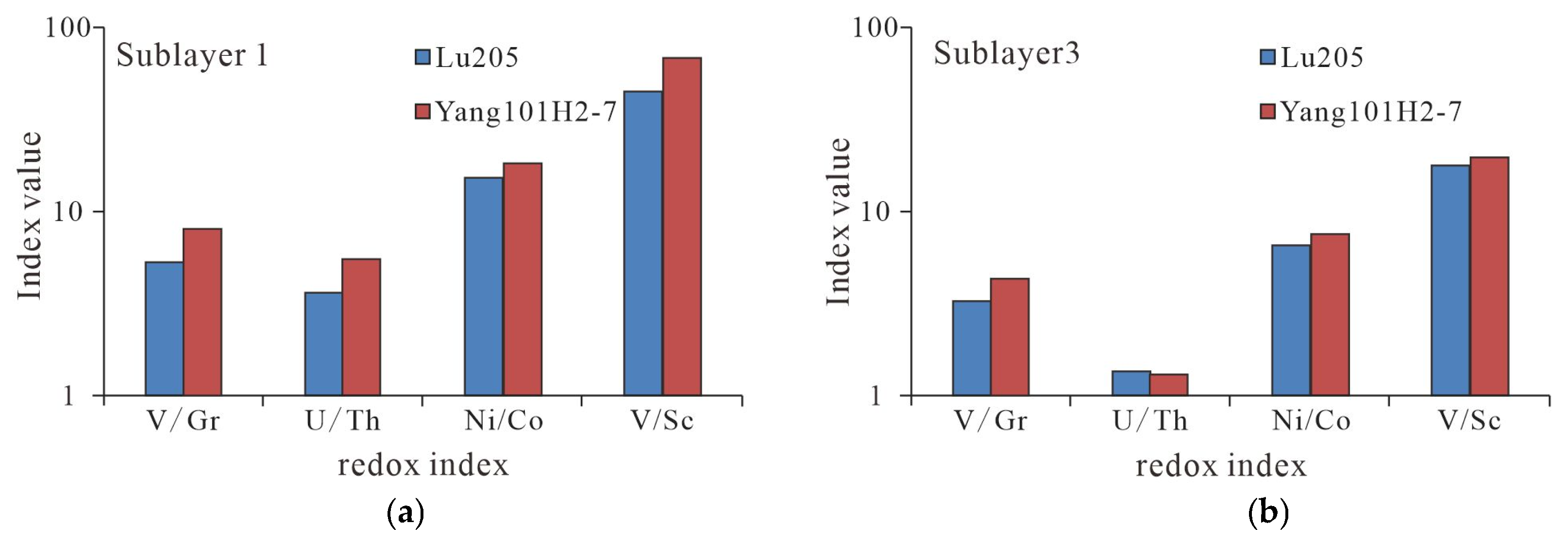

5.2.1. Deep-Water Stagnant Deposition as the Foundation for Quality Shale and High Productivity

5.2.2. Abnormally High Pressure and High Gas Content as Guarantees of High Production

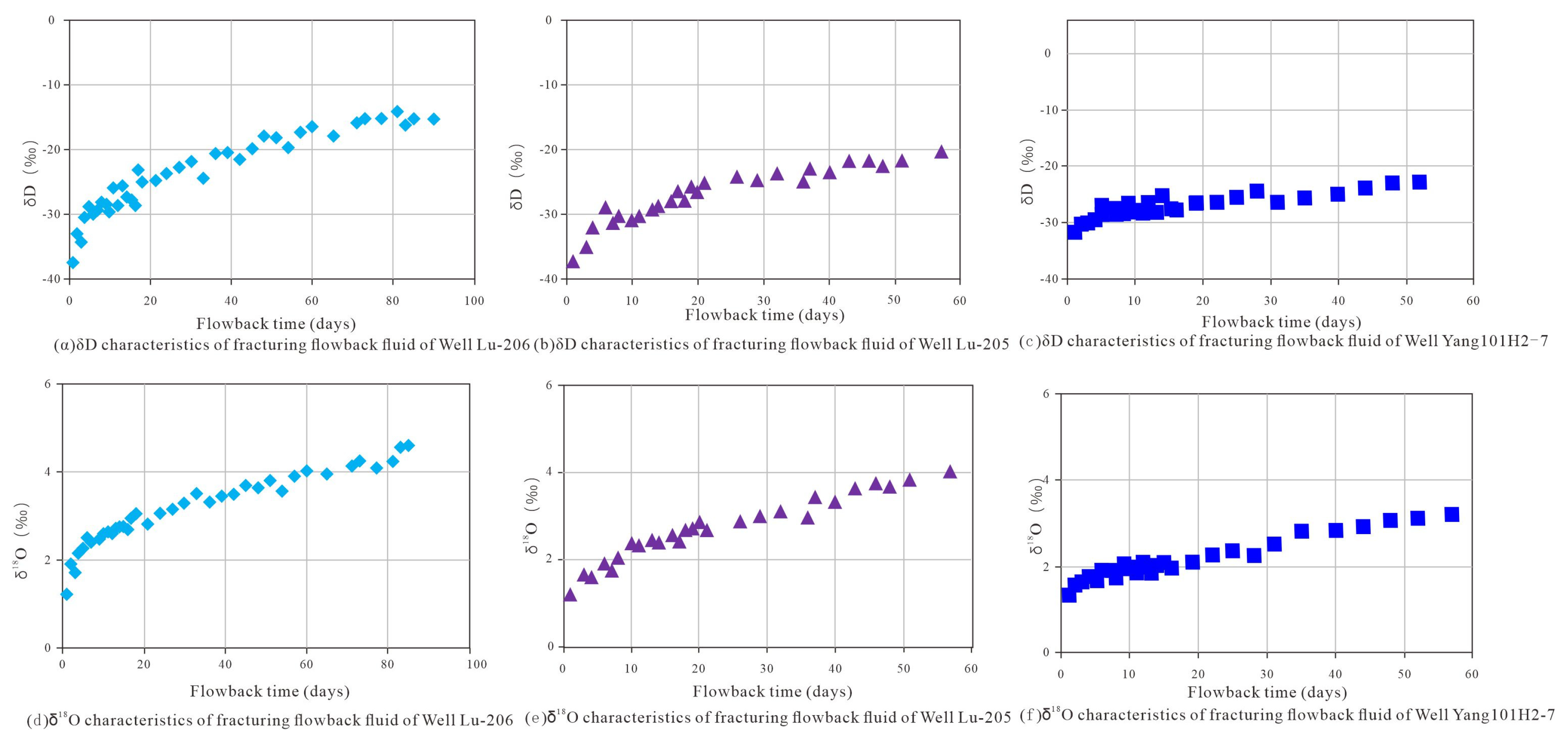

5.2.3. Effective Fracturing as the Key to High Production

6. Conclusions

- Significant macroscopic reservoir heterogeneity with quality intervals concentrated at the bottom. The shales in the study area are overall organic-rich, but vertically, the organic content decreases upward, with the Long11-1 and Long11-2 sublayers having the highest TOC. Porosity and gas content show a similar distribution: the Long11-1-3 sublayers have an average porosity of 4–6% and total gas content of 6–10 m3/t, significantly better than the overlying Long11-4 and basal WF. Brittle minerals (quartz, carbonates, etc.) are more abundant in the lower part, giving Long11-1–11-3 brittleness indices generally >50%, whereas Long11-4 is below 40%. Therefore, the WF top and the lower-middle Long 11 sub-member shales constitute the best reservoir “sweet spots” in this area, characterized by high TOC, high porosity, high gas content, and high brittleness.

- Large inter-layer differences in microscopic pore structure, which control free gas occurrence and flow capacity. SEM and pore size analyses reveal that the Long11-1 and Long11-3 sublayers develop abundant, well-connected organic-matter pores; inorganic pores are mainly intraparticle dissolution pores with a certain proportion >100 nm, and these larger pores provide the main space for free gas. In contrast, the Long11-2 and Long11-4 sublayers have sparse organic pores, mostly <50 nm; inorganic pores are a mix of inter- and intraparticle, but generally small; microfractures are relatively more common. Compared to shallow shale, deep shale has a lower proportion of large organic pores and interparticle pores, resulting in poorer pore connectivity and more gas in the adsorbed state; however, slightly more microfractures in deep shale help with some degree of connectivity. Intervals with well-developed medium-to-large pores have high efficiency of adsorbed-/free-gas conversion, and can sustain gas supply during production, manifesting as stable high output, whereas intervals dominated by tiny pores have little free gas and limited desorption, leading to weak gas production.

- Deep shale reservoirs have more complex pore structures than shallow ones: a shift toward smaller pores but with microfractures partially compensating for permeability. Compared to shallow shale, the deep shale in this area shows a slight decrease in organic pore fraction, pore sizes mostly under 100 nm, inorganic pore dominance shifting from interparticle to intraparticle, and microfracture fraction increasing from <6% to 10%. Deep high-pressure conditions have preserved some organic pores, to an extent, but overall compaction led the pore system to evolve towards smaller scales. The presence of microfractures improves fluid flow pathways and facilitates gas migration, although too many fractures could jeopardize gas retention.

- High shale-gas-well productivity is determined by a synergy of multiple factors: a deep-water anoxic depositional environment, high pressure and high gas content, and sufficient effective reservoir stimulation are all indispensable. A deep, anoxic shelf depositional setting resulted in organic-rich, silica-rich shales (high free-gas potential + high brittleness), providing the geological premise for high productivity. Abnormally high formation pressure effectively preserves organic pores and supports high gas content; together, high gas in place and high pressure directly supply the material and energy conditions for high output. Finally, only through effective volumetric fracturing that fully stimulates the high-quality reservoir and connects a large volume of pores and free gas can those favorable geological conditions be translated into actual high gas flow. Future research will focus on developing quantitative models integrated with long-term monitoring to simulate the temporal evolution of reservoir pore structure and production performance under hydraulic-fracturing development conditions, thereby guiding more effective exploitation of deep shale gas resources.

- The understanding of pore structure and its impact on seepage obtained in this study is primarily based on statistical analysis of two-dimensional cross-sections. Future work will integrate advanced three-dimensional characterization techniques, such as high-pressure high-temperature in situ micro-CT experiments, to more realistically reveal the dynamic microstructure of reservoirs under deep conditions, thereby validating, supplementing, and deepening the conclusions of this research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wen, L.; Dang, L.; Xie, J.; Zhang, B.; Lu, J.; Sun, H.; Ming, Y.; Ma, H.; Chen, X.; Xu, C.; et al. Enrichment and Exploration Potential of Shale Gas in the Permian Wujiaping Formation, Northeastern Sichuan Basin. Energies 2025, 18, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.N.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, G.S.; Zhu, R.K.; Tao, S.Z.; Yuan, X.J.; Hou, L.H.; Dong, D.Z.; Guo, Q.L.; Song, Y.; et al. Theory, Technology and Practice of Unconventional Petroleum Geology. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 34, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Guo, W.; Yuan, L. Quantitative Assessment of Shale Gas Preservation in the Longmaxi Formation: Insights from Shale Fluid Properties. J. Geo-Energy Environ. 2025, 1, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chang, C.; Cheng, Q.; Xie, W.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Z. Experimental Study on Two-Phase Gas–Water Flow in Self-Supported Fractures of Shale Gas Reservoir. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 2025, 7, 136–152. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; He, S.; Radwand, A.E.; Xie, J.; Qin, Q. Quantitative Analysis of Pore Complexity in Lacustrine organic-Rich Shale and Comparison to Marine Shale: Insights from Experimental Tests and Fractal Theory. Energy Fuel. 2024, 38, 16171–16188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, S.; Qi, L.; Liang, P. Types and Characteristics of Sweet Spots of Marine Black Shale and Significance for Shale Gas Exploration: A Case Study of Wufeng–Longmaxi in Southern Sichuan Basin. Energy Geosci. 2023, 3, 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kolawole, O.; Oppong, F. Assessment of Inherent Heterogeneity Effect on Continuous Mechanical Properties of Shale via Uniaxial Compression and Scratch Test Methods. Rock Mech. Bull. 2023, 2, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzingila, R.M.; Kong, L.; Kasongo, R.K. A Review on Experimental Techniques and Their Applications in the Effects of Mineral Content on Geomechanical Properties of Reservoir Shale Rock. Rock Mech. Bull. 2024, 3, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Gao, S.; Chen, Z. A Semianalytical Model of Fractured Horizontal Well with Hydraulic Fracture Network in Shale Gas Reservoir for Pressure Transient Analysis. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 8, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Wang, J.; Yuan, B.; Shen, Y. Review on Gas Flow and Recovery in Unconventional Porous Rocks. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2017, 1, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wei, J.; Dai, J.; Xue, F.; Wang, L.; Tang, Y.; Yang, J. Fluid-Driven Effects and Seismic Characteristics in Southern Sichuan Shale Gas Development Area: Insights from the Changning and Weiyuan Fields. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 2025, 7, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Sima, L.; Wang, L.; Tang, S.; Li, J.; Jin, W.; Liu, B.; Li, B. Quantitative Assessment of Free and Adsorbed Shale Oil in Kerogen Pores Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Experiment Characterization. Energies 2025, 18, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwumelu, C.; Kolawole, O.; Nordeng, S.; Olorode, O. Analyzing Thermal Maturity Effect on Shale Organic Matter via PeakForce Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping. Rock Mech. Bull. 2024, 3, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhu, R.K.; Cui, J.W.; Lu, Y.Z.; Li, Y. Constraints of Sedimentary Environment on Organic Matter Accumulation in Shale: A Case Study in Southern Sichuan Basin. Energy Geosci. 2021, 2, 631–644. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, D.J.K.; Bustin, R.M. The Importance of Shale Composition and Pore Structure upon Gas Storage Potential of Shale Gas Reservoirs. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2008, 25, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Hu, D.; Wen, Z.; Liu, R. Main Controlling Factors for Marine Shale Gas Enrichment and High Productivity in the Lower Paleozoic of the Sichuan Basin. Geol. China 2014, 41, 893–901. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Du, W.; Bai, Z.; Wang, R.; Sun, C.; Feng, D. Key Geological Factors Governing Sweet Spots in the Wufeng–Longmaxi Shales of the Sichuan Basin. Energy Geosci. 2024, 5, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, Z.; Feng, X. Hydrocarbon Accumulation Conditions and Exploration Targets of the Sinian Dengying Formation in Southeastern Sichuan Basin. Energy Geosci. 2023, 4, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, X.; Xue, F.; Dai, J.J.; Yang, J.X.; Huang, H.Y.; Hou, Z.M. Influence of Natural Fractures of Multi-Feature Combination on Seepage Behavior in Shale Reservoirs. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 2024, 6, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gui, H.; Su, S.; Zhou, Q. Sedimentary Environment and Paleoclimate Geochemical Characteristics of Shale in the Wufeng and Longmaxi Formations, Northern Yunnan–Guizhou Area. Energy Geosci. 2022, 2, 653–666. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L.; Zheng, A.; Yan, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Yi, Y. Enhanced Understanding of Carbonate-Rich Shale Heterogeneity through Multifractal Characterization Based on N2 Adsorption Data: A Case Study of the Permian Wujiaping Formation in the Sichuan Basin. Energy Geosci. 2025, 6, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, J.; Yan, B.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, N.; Liang, P.; Guo, W. Deep-Water Traction Current Sedimentation in the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation Siliceous Shales, Weiyuan Area, Sichuan Basin, China. Minerals 2025, 15, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; He, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Cao, Q.; Yang, K.; Zhang, B. Mechanisms of Reservoir Space Preservation in Ultra-Deep Shales: Insights from the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formation, Eastern Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2024, 14, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L.; Wu, P.; Wang, Z. Research and Application of Geomechanics Using 3D Model of Deep Shale Gas in Luzhou Block, Sichuan Basin, Southwest China. Geosciences 2025, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Mao, W.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, S. Research on the Differential Tectonic–Thermal Evolution of Longmaxi Shale in the Southern Sichuan Basin. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 7, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Guo, C.; Ma, C.; Gong, X.; Zhao, H. Current Status and Development Prospects of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) in China: Technical, Policy, and Market Perspectives. J. Geo-Energy Environ. 2025, 1, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglauer, S.; Lebedev, M. High pressure-elevated temperature x-ray micro-computed tomography for subsurface applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 256, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Pei, Y.; Wang, C.; Dong, H. Pore-scale investigation of microscopic remaining oil variation characteristics in water-wet sandstone using CT scanning. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 48, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; He, W.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, S.; Wang, H.; Xia, Y. Characterization of Water Micro-Distribution Behavior in Shale Nanopores: A Comparison between Experiment and Theoretical Model. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2025, 15, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Chen, Y.; Tang, T.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Peng, S.; Zhang, J. Multiscale Characterization of Pore Structure and Heterogeneity in Deep Marine Qiongzhusi Shales from Southern Basin, China. Minerals 2025, 15, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Guo, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, R.; Chen, X.; Fan, W.; Deng, Z. Pore Structure and Heterogeneity Characteristics of Deep Coal Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Daning–Jixian Block on the Southeastern Margin of the Ordos Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tian, F.; Deng, Z.; Hu, H. The Characteristic Development of Micropores in Deep Coal and Its Relationship with Adsorption Capacity on the Eastern Margin of the Ordos Basin, China. Minerals 2023, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Kishor, K.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Mustapha, K.A.; Saxena, A. Multi-Analytical Assessment of Shale Gas Potential in the West Bokaro Basin, India: A Clean Energy Prospect. Energy Geosci. 2025, 6, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Guo, Y.; Qin, J.; Ba, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, L.; Li, H. Fluid Identification and Tight Oil Layer Classification for the Southwestern Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin Using NMR Logging-Based Spectrum Decomposition. Energy Geosci. 2024, 5, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, G.; Meng, X.; Gu, Q.; Qin, Z. Study on Aging Characteristics of Creep Strain Energy Density Evolution and Damage Constitutive Model of Rock. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 2025, 7, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Chen, F.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, N. Mining Pressure Weakening Mechanism by Ground Fracturing and Fracturing Evaluation of Hard Rock Strata. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 2022, 4, 023027. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Feng, Y.; Tan, Z.; Yang, T.; Yan, S.; Li, X.; Deng, J. Simultaneously Improving ROP and Maintaining Wellbore Stability in Shale Gas Well: A Case Study of Luzhou Shale Gas Reservoirs. Rock Mech. Bull. 2024, 3, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, X.D.; Radwan, A.E.; Wang, H.J.; Yin, S. Geomechanics and Engineering Evaluation of Fractured Oil and Gas Reservoirs: Progress and Perspectives. Energies 2025, 18, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, H.; Qin, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhong, C. Effectiveness Evaluation of Natural Fractures in Xujiahe Formation of Yuanba Area, Sichuan Basin, China. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, D.; Zhu, J.; Cai, J. Integrated Rock Physics Characterization of Unconventional Shale Reservoir: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2024, 14, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Gong, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shao, X. Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Multi-Scale Pore Structure Heterogeneity of Lacustrine Shale in the Gaoyou Sag, Eastern China. Minerals 2023, 13, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Z.Q.; Gao, X.D.; Xie, J.T.; Qin, Q.R.; Wang, H.J.; He, S. Pore Structure Evolution and Geological Controls in Lacustrine Shale Systems with Implications for Marine Shale Reservoir Characterization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Ge, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, T. Karst Topography Paces the Deposition of Lower Permian, Organic-Rich, Marine–Continental Transitional Shales in the Ordos Basin, Northwestern China. AAPG Bull. 2024, 108, 849–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Lu, S.; Xiao, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Organic Pore Heterogeneity and Its Impact on Absorption Capacity in Shale Reservoirs in the Wufeng and Longmaxi Formations, South China. Energy Geosci. 2025, 6, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Wu, C.; Tuo, J. Relationships between Organic Structure Carbonization and Organic Pore Destruction at the Overmatured Stage: Implications for the Fate of Organic Pores in Marine Shales. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 6906–6921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wei, J.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Lin, J.; Li, J. Experimental Study on the Influence of External Fluids on the Pore Structure of Carbonaceous Shale. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Guo, Y. Study on the Pore Evolution of Xinjiang Oil Shale under Pyrolysis Based on Joint Characterization of LNTA and MIP. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2023, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Qi, Z.; Yan, W.; Huang, X.; Li, J. Influence of Water on Gas Transport in Shale Nanopores: Pore-Scale Simulation Study. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhang, K.; Nie, H.; Guo, S.; Li, P.; Sun, C. High-Quality Reservoir Space Types and Controlling Factors of Deep Shale Gas Reservoirs in the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formation, Sichuan Basin. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, P.; Gao, Q.; Bao, T. Time-dependent damage characteristics of shale induced by fluid–shale interaction: A lab-scale investigation. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Radwan, A.E.; Xiao, F.; Xie, G.; Lai, P. Developmental Characteristics of Vertical Natural Fracture in Low-Permeability Oil Sandstones and Its Influence on Hydraulic Fracture Propagation. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Pan, J.; Xi, X.; Wang, P.; Cai, M. A Negative Value of the Non-Darcy Flow Coefficient in Pore–Fracture Media under Hydro-Mechanical Coupling. Minerals 2023, 13, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Tan, W.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Niu, P.; Qin, Q. Mineralogical and lithofacies controls on gas storage mechanisms in organic-rich marine shales. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 3846–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Jin, Z.; Ma, X.; Liu, Y. Numerical Simulation of the Effect of Shale Lamination Structure on Hydraulic Fracture Propagation Behavior. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2025, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, S.; Tang, H.; Xi, Z.; Zhao, N.; Sun, S.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, S. Pore Structure Heterogeneity of Deep Marine Shale in Complex Tectonic Zones and Its Implications for Shale Gas Exploration. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 1891–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Kang, Y.; Chen, M.; You, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, W.; Feng, S.; Xin, X.; Li, P. Adsorbed and Free Methane Production Behaviors of Deep Shale Reservoirs in Aqueous-Saturated Conditions. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 22191–22204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, X.; Dong, B. A Review of the Recent Advances in CH4 Recovery from CH4 Hydrate in Porous Media by CO2 Replacement. Energies 2025, 18, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, W.; Pan, C. Unloading Damage Mechanism and Pore Structure Evolution Characteristics of Different Coal and Rocks. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2025, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Duan, H.T.; Qin, Q.R.; Zhao, T.; Fan, C.; Luo, J. Characteristics and distribution of tectonic fracture networks in low permeability conglomerate reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Ma, X.; Hua, S.; Ma, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, B.; Tian, W.; Jiang, S.; Hu, R. Influence of Sedimentary Environments on Organic-Matter Enrichment in Marine–Continental Transitional Shale: A Case Study of the Upper Permian Longtan Formation in the Central Hunan Depression, China. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 14262–14277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, W.; Mou, C.; Chen, L. Geochemistry of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Black Shales in the NW Middle Yangtze Basin: Implications for Provenance, Paleoenvironment, and Heterogeneity of Organic Matter. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2025, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chang, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, C.; Suo, Y. Advances, challenges, and opportunities for hydraulic fracturing of deep shale gas reservoirs. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2025, 15, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wei, S.; Jin, Y.; Xia, Y. Study on the long-term influence of proppant optimization on the production of deep shale gas fractured horizontal well. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, Z.; Tang, T.; Yang, C.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ruan, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, K. Reservoir Characteristics and Productivity Controlling Factors of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations in the Lu203–Yang101 Well Block, Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Energies 2026, 19, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020444

Gao Z, Tang T, Yang C, Li J, Wu Y, Wang Y, Ruan J, Xiao Y, Li H, Zhang K. Reservoir Characteristics and Productivity Controlling Factors of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations in the Lu203–Yang101 Well Block, Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Energies. 2026; 19(2):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020444

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Zhi, Tian Tang, Cheng Yang, Jing Li, Yijia Wu, Ying Wang, Jingru Ruan, Yi Xiao, Hu Li, and Kun Zhang. 2026. "Reservoir Characteristics and Productivity Controlling Factors of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations in the Lu203–Yang101 Well Block, Southern Sichuan Basin, China" Energies 19, no. 2: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020444

APA StyleGao, Z., Tang, T., Yang, C., Li, J., Wu, Y., Wang, Y., Ruan, J., Xiao, Y., Li, H., & Zhang, K. (2026). Reservoir Characteristics and Productivity Controlling Factors of the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations in the Lu203–Yang101 Well Block, Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Energies, 19(2), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020444