1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement of China’s “Dual Carbon” goals and the ongoing construction of a new-type power system, new energy sources like wind and solar power are developing rapidly [

1]. By the end of 2024, China’s installed capacity of new energy power generation reached 1.45 billion kilowatts, surpassing that of thermal power for the first time [

2]. The concentrated integration of numerous new energy stations into the power grid presents significant challenges for grid dispatch and operation. Among these, the contradiction between new energy installation and integration is becoming increasingly prominent, primarily manifested as insufficient system peak-shaving capacity [

3,

4] and inadequate inter-regional power transmission capacity [

5,

6]. Against the backdrop of this conflict between large-scale new energy grid integration and the difficulties in its absorption, accurately assessing a reasonable new energy hosting capacity can reduce wind and solar curtailment and improve the integration level of new energy within the power system. Therefore, there is an urgent need for research on new energy integration assessment to guide the planning of new energy development and the optimization of dispatch operations [

7], thereby fully ensuring the maximized utilization of resources and the secure, stable operation of the power grid.

Early research in hosting capacity often employed deterministic methods, such as worst-case scenario analysis (e.g., maximum generation and minimum load), to establish firm network limits. While computationally simple, these methods are often overly conservative, failing to capture the temporal variability of variable renewable energy (VRE) and load, thus underestimating the true potential of the system. To address this limitation, probabilistic and time-series simulation methods have become the standard. These approaches use long-term chronological data to model the dynamic balance between supply and demand, providing a more realistic estimate of energy integration over time. As He et al. (2022) highlight, production cost modeling and optimal power flow simulations are now widely used to quantify integration challenges, such as curtailment and the need for flexible resources [

8]. These models can incorporate the operational constraints of conventional generators, which are a primary cause of “peak shaving” curtailment.

Currently, the assessment framework has evolved to explicitly model system flexibility as the key enabler for higher VRE penetration. Luo et al. (2023) demonstrate that a system’s ability to manage VRE variability and uncertainty is a stronger constraint than steady-state power flow in many cases [

9]. This has shifted the focus from static “firm capacity” to dynamic “utilization hours” and the adequacy of flexibility resources, such as flexible generation and energy storage. In this way, research methodologies for assessing new energy integration capacity are mainly divided into the typical day method [

10,

11,

12] and the stochastic production simulation method [

13,

14,

15]. The typical day method usually selects typical load days for each season or month to analyze the overall power and energy balance of the grid and determine its new energy integration capacity. However, this method cannot account for the stochasticity and volatility of new energy output and load, and its results cannot reflect the annual integration situation. The stochastic production simulation method uses discrete random variables following certain distributions to describe the probabilistic characteristics of load, wind, and solar power output. It calculates the discrete probability distribution of actual and curtailed new energy power through operations on these probability distributions, possessing a strong mathematical statistics foundation. Nevertheless, its modeling process is relatively complex, and it fails to consider practical issues such as unit ramping and start-ups, making it difficult to apply in engineering practice.

The time-series power balance simulation method typically uses a year as the calculation cycle and 15 min or hourly time steps. Under a given set of boundary conditions, it simulates the actual grid’s power balance and new energy integration situation through chronological simulation. This method requires numerous input boundary conditions and involves high computational complexity [

16,

17], but it can simulate grid operation conditions relatively accurately. Most current research on new energy integration capacity focuses on single provincial power grids [

18,

19,

20,

21], neglecting the mutual support capabilities within regional grids and the coordination potential between different regional grids [

22,

23]. Furthermore, practical engineering modeling and application analysis that simultaneously consider wind power, solar power, conventional hydropower, pumped storage, thermal power, and nuclear power are rarely seen. The assessment challenges of renewable energy hosting capacity remain, especially in real-world applications.

To address this, this paper took the practical context of the Northeast China Power Grid as background. A long-term chronological power balance simulation approach was developed, integrating the dynamic balance among multiple types of power sources, loads, and outbound transmission. Dispatch schemes suitable for different types of power sources, including hydropower, thermal power, wind power, solar power, and nuclear power, were designed based on their operational characteristics. Key operational constraints, such as output limits, staged water levels, pumping/generation modes of pumped storage, and nuclear power regulation duration, were considered [

24,

25,

26,

27]. A refined analysis model for renewable energy accommodation in regional power grids was constructed, aiming to maximize the total accommodated renewable energy electricity.

Using 2024 historical grid operation data as model input, it accurately simulates the refined dispatch and operation modes of the regional power grid throughout the year. Furthermore, it conducts analyses on the level of new energy integration and its sensitivity in the next year. We found that the utilization rate of new energy might decrease to nearly 90%, and this curtailment due to insufficient peaking capacity is expected to constitute approximately 80% of the total renewable energy curtailment. Based on the results of our sensitivity analysis, it is recommended to moderately control the pace of renewable energy capacity expansion and accelerate the construction of flexible regulating power sources, such as energy storage, to ensure maximum renewable energy integration.

This paper presents a calculation model for new energy generation utilization based on long-term power balance simulation. By performing sensitivity analyses across various combinations of new energy installed capacity and new-type energy storage capacity, the model enables the simulation and evaluation of new energy utilization rates. The findings offer valuable decision support for future planning of new energy and energy storage installations in the Northeast Power Grid.

2. Overview of the Study Area

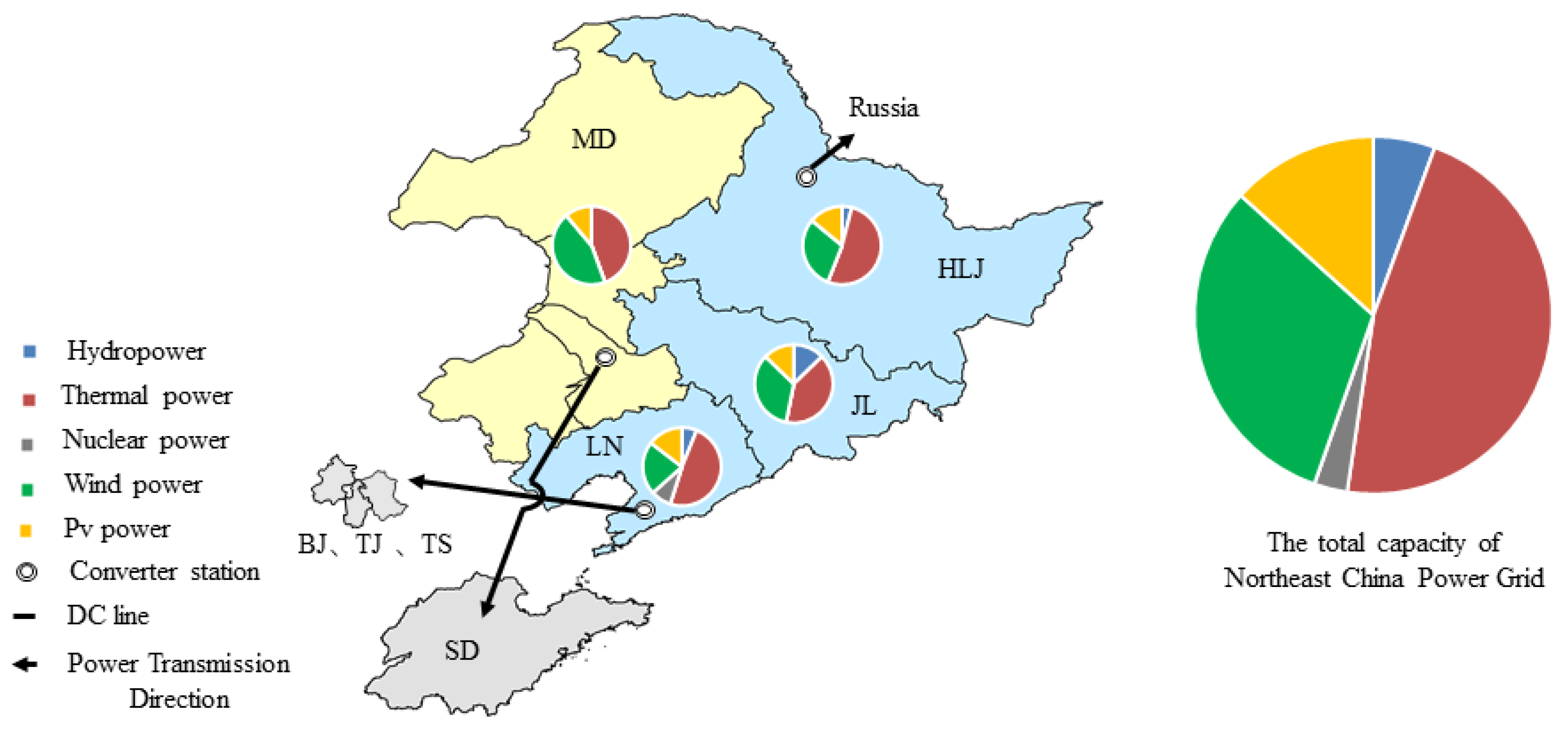

As of December 2024, the Northeast China Power Grid had a total installed capacity of 232 GW. Within this, the installed capacity of new energy reached 103 GW, accounting for 44.3% of the total.

Figure 1 shows the power source structure of the power grid. The maximum new energy generation output recorded was 44.61 GW, representing 60% of the grid’s total electricity demand (74.35 GW). The annual electricity generation from new energy sources amounted to 188.6 TWh, constituting 29.4% of the total electricity generation.

The grid is interconnected with the Russian Far East grid via the Heihe back-to-back HVDC (High-Voltage Direct Current) link, which has a transmission capacity of 750 MW. It is also connected to the Beijing-Tianjin-Tangshan grid via the Gaoling back-to-back HVDC link, with a transmission capacity of 3000 MW. Furthermore, the ±800 kV Zhalute-Qingzhou HVDC line links the grid with the Shandong power grid, boasting a designed capacity of 10,000 MW, though its current operational transmission capability stands at 7500 MW. The jurisdictional area of the power grid and its inter-regional transmission lines are illustrated in

Figure 1.

In 2024, the new energy utilization rate within this grid was 95.03%. Characterized by a high penetration of new energy, a relatively limited system scale, and constrained external transmission channels, the grid faces a severe challenge in integrating renewable energy. Therefore, this study utilizes this grid as a case study. By establishing the necessary boundary conditions for the assessment model, it projects the new energy integration scenario for the next year and conducts sensitivity analyses. Based on the simulation results, practical recommendations for grid planning and operation are proposed.

3. Long-Term Time-Series Power Balance Simulation-Based Model for New Energy Integration

3.1. Long-Term Time-Series Power Balance Simulation Method

The long-term time-series power balance simulation method typically treats system load and new energy generation output as time-varying sequences. It operates on a monthly or annual calculation timeframe with minute- or hour-level time steps. Based on scenarios of wind power, solar output, load, and cross-regional power delivery, and while considering generation constraints and operational conditions, it sequentially optimizes the output of each generation unit. This method simulates the actual grid’s power balance and new energy integration through time-series analysis. It should be noted that this framework is implemented as a chronological production-simulation model with stepwise dispatch optimization, rather than as a single centralized LP/MILP optimization program.

Therefore, this paper employs the long-term time-series power balance simulation method. With the objective of maximizing integrated new energy production, and accounting for the time-varying characteristics of grid operation modes, the model establishes specific boundary conditions for power system operation. Using a 15 min calculation step, it sequentially simulates the operation status of various power sources, generation-load balance, and new energy integration throughout a full year. Ultimately, the model determines the acceptable new energy power and energy capacity of the regional grid for the target year.

3.2. Objective Function

To investigate the renewable energy integration capacity of the regional power grid, an objective function of the model is developed to maximize the total integrated renewable energy generation over the entire year. The purpose of this objective is to maximize the accommodated renewable energy under existing system operating constraints, as detailed below:

where

Fobj is the objective function for the integration assessment, representing the total renewable energy generation;

Pw,t is the actual wind power output of the entire grid at time interval

t;

Ppv,t is the actual solar power output of the entire grid at time interval

t;

is the duration of each time step;

t is the time index; and

T is the total number of time intervals in the simulation.

3.3. Operational Modes and Constraints of Various Power Sources

Considering the conditions of grid production operation and the limitations imposed by the operational characteristics of hydro, thermal, wind, solar, and nuclear power sources, suitable operational modes must be designed within the model for the distinct operating features of each generation type. Additionally, some main dispatch constraints must be taken into account.

3.3.1. Power Balance Constraint

During power system operation, generation and load must remain balanced at all times. The real-time power balance constraint is given by

where

Pt,t is thermal power output of the power grid at time interval

t;

Ph,t is conventional hydropower output of the power grid at time interval

t;

Pn,t is nuclear power output of the power grid at time interval

t;

Pps,t is pumped storage output of the power grid at time interval

t (negative during pumping, positive during generation);

Pload,t is load demand of the power grid at time interval

t;

Plink,t is power flow on inter-regional tie-lines at time interval

t (positive for export, negative for import);

Phs,t is power consumption of electric heating systems in the power grid during the heating period at time interval

t.Considering regional load characteristics and to fully accommodate renewable energy, the regional grid performs day-ahead peak load balance calculations each day to determine the unit commitment of thermal power plants for the following day. This process establishes the required online thermal capacity.

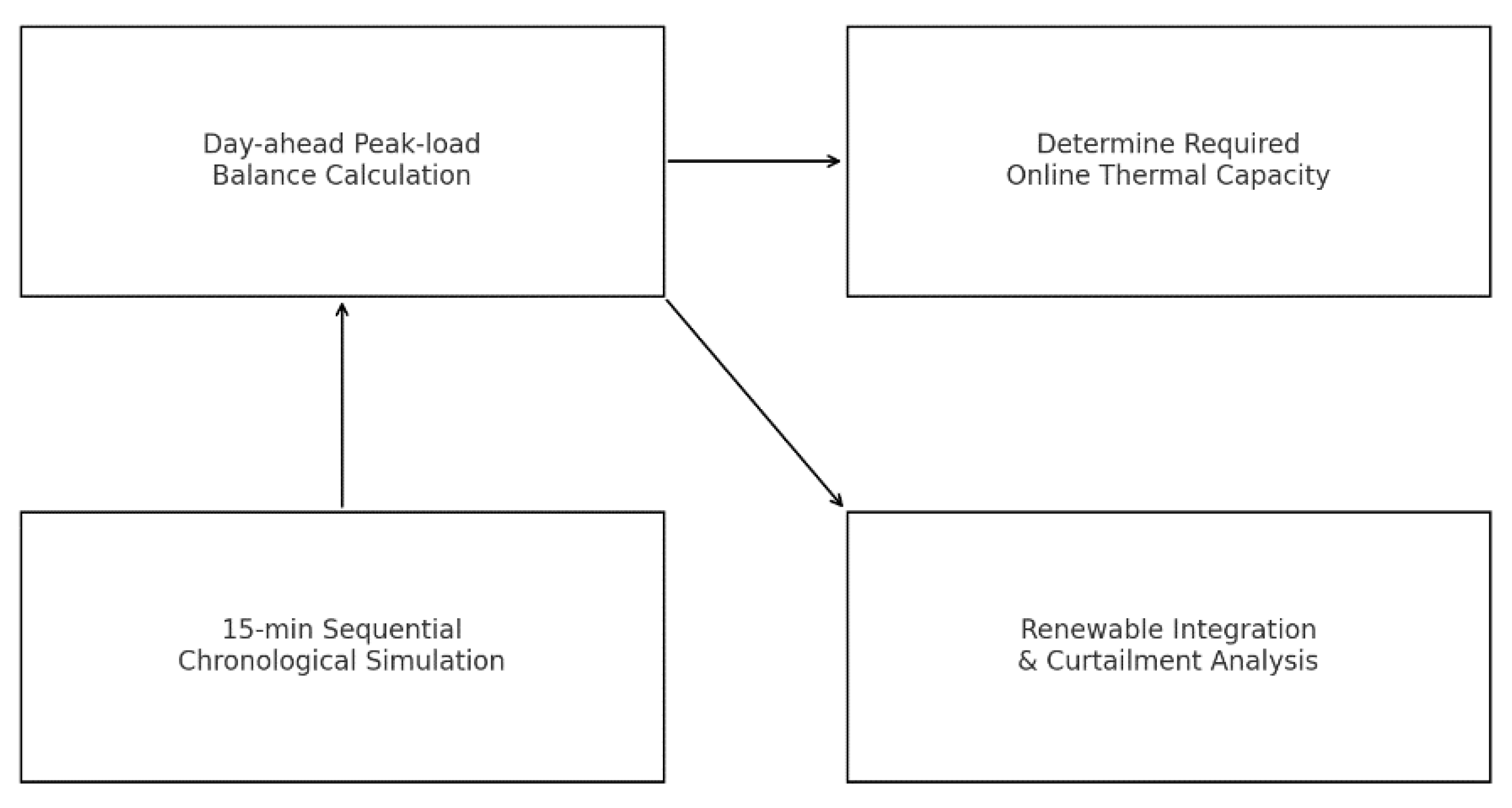

As shown in

Figure 2, the model operates in two nested time scales:

For each day, we first perform a peak-load balance calculation using forecasted wind/solar output, hydropower peak-shaving capability, nuclear availability, pumped-storage capability, and inter-regional tie-line schedules. This step determines the required online capacity of thermal units (≥100 MW), which is treated as a fixed boundary condition for the next day.

- 2.

Intra-day chronological simulation (15 min time step):

Using the day-ahead online thermal capacity and all operational constraints, the model sequentially simulates the output of all generation types, the generation–load balance, and renewable energy accommodation for each 15 min interval. Curtailment is determined endogenously based on real-time balance, ramping limits, and network transmission limits.

Beyond the basic generation-load balance, the day-ahead power balance also incorporates provisions for positive spinning reserve capacity and includes a certain percentage of forecasted renewable energy output. The day-ahead power balance constraint is as follows:

where

Ptl,cap,d is online capacity of large thermal units (≥100 MW) in the power grid on day

d;

βi is maximum load rate for thermal power in the power grid during month

i;

Pts,d is output of small thermal units (<100 MW) in the power grid at the peak load moment on day

d (usually based on the value from the same period in the previous year);

Ph,d is peak shaving capability of conventional hydropower in the power grid on day

d;

Pw,p,d is forecasted wind power output of the power grid on day

d;

Ppv,p,d is forecasted solar power output of the power grid on day

d;

γ is integration coefficient for forecasted renewable energy output in the balance calculation;

Pn,d is online capacity of nuclear power in the power grid on day

d;

Pps,d is pumped storage output included in the balance calculation at the peak load moment on day

d;

Pload,d is peak load demand of the power grid on day

d;

Plink,d is power flow on inter-regional tie-lines at the peak load moment on day

d (positive for export, negative for import);

λi is reserve rate for the entire grid in month

i, used to calculate the positive spinning reserve capacity.

3.3.2. Thermal Power Operation Mode and Its Constraints

The total thermal power output of the power grid is bounded by specific limits. The upper limit is defined as the sum of the online capacity of large thermal power units (≥100 MW) multiplied by their maximum load rate, plus the output of small thermal power units (<100 MW). The lower limit is the sum of the minimum deep regulation output of all large thermal units and the output of all small thermal power units.

Furthermore, due to the limited ramping capability of conventional thermal power, ramping constraints are also implemented. The thermal power output constraints are formulated as follows:

where

Ptl,min,t is minimum deep regulation output of large thermal units (≥100 MW) in the power grid at time interval

t;

Pts,t is output of small thermal power units (<100 MW) in the power grid at time interval

t (based on the value from the same period in the previous year);

Ptl,t is output of large thermal power units (≥100 MW) in the power grid at time interval

t;

Ptl,max,t is maximum output limit of large thermal power units (≥100 MW) in the power grid at time interval

t;

Ptl,cap,d is online capacity of large thermal power units (≥100 MW) in the power grid on day

d;

αi is maximum deep regulation rate for thermal power in month

I;

ηtl is ramping rate of thermal power units;

ηtl,up is for upward ramp rate and

ηtl,down is for downward ramp rate.

3.3.3. Conventional Hydropower Operation Constraints and Reservoir Regulation Strategies

The Northeast China Power Grid primarily features multi-year regulation reservoirs under its direct dispatch. However, hydropower constitutes a relatively small portion of the total installed capacity, at only 3.8%. Given the significant regulation range of these reservoirs and the minor share of hydropower output, the model sets the upper output limit for conventional hydropower based on its peak shaving capability, which depends on the month, reservoir storage status, and unit maintenance. The lower power output limit is set using the historical minimum output from the corresponding month of the previous year. The hydropower output constraint is formulated as follows:

where

Ph,min,d is the minimum output of conventional hydropower for the power grid on day

d.

Furthermore, to maximize the support capability of large regulating reservoirs for both the power capacity and energy generation of wind and solar power, the following annual phased water level control strategy is adopted for hydropower stations.

- (1)

Shift from “gilling reservoirs to full capacity” to “moderate storage” at the end of the flood season

As mentioned above, the main reservoirs directly dispatched by the power grid are all incomplete multi-year regulation reservoirs. Even if not filled to capacity by the end of the flood season, they are sufficient to provide peak shaving support during periods of tight winter power supply. Moreover, with the rapid growth of new energy, the dispatchable space for hydropower is gradually shrinking. Filling reservoirs completely at the end of the flood season could make it difficult to lower water levels later. Therefore, the traditional principle of “retaining the final flood flows and striving to fill reservoirs by the end of September” is adjusted. Fully considering future grid peak shaving, frequency regulation, and watershed water supply needs, the end-of-flood-season storage principle is optimized. During the low-wind periods of August and September, hydropower generation is prioritized to harness its energy earlier. At the end of the flood season, flood tails are retained moderately, ensuring reservoirs operate at high water levels without being completely filled, thereby reducing the pressure to draw down levels during high-wind periods. This strategy introduces the following water level control constraint at the end of the flood season:

where

is the reservoir water level of hydropower station

m at the end of the flood season;

is the upper limit for the water level of hydropower station

m at the end of the flood season;

is the lower limit for the water level of hydropower station

m at the end of the flood season;

m is the index identifying the hydropower station.

- (2)

Shift from “slow drawdown” to “advanced drawdown” during the dry season

Maintaining high reservoir water levels from October to March (the dry season) necessitates intensive, high-output power generation during the subsequent water supply period to achieve the required drawdown. This period often coincides with high output from new energy sources, leading to integration challenges. Consequently, the traditional dry-season operational principle of “controlling a slow reservoir drawdown, maintaining overall high water levels” is adjusted [

28,

29]. During the dry season, reservoir power generation is increased earlier, and water levels are drawn down uniformly in advance across the months. Taking 2025 as an example, by the end of March, the water levels for Baishan, Fengman, Nierji, and Yunfeng should be drawn down in advance to approximately 402 m, 256 m, 212 m, and 295 m, respectively. The corresponding water level control constraint for these stations at the end of the dry season can be uniformly expressed as

where

is the reservoir water level of hydropower station

m at the end of the dry season;

is the target water level for hydropower station

m at the end of the dry season.

- (3)

Shift from “rapid drawdown” to “maintaining water level” during the water supply season

The water supply season (April–May) overlaps with the high-wind period, making significant reservoir drawdown difficult. Therefore, the traditional principle of “increasing generation at the start of the water supply season to control rapid reservoir drawdown” is adjusted. Following the advanced drawdown in the dry season, hydropower generation is minimized during the water supply season, maintaining stable reservoir water levels wherever possible, under the basic premise of ensuring downstream water supply and grid peak shaving/frequency regulation needs. This strategy creates more space for new energy generation during its high-output period. If exceptionally low inflow during the water supply season causes a rapid drop in reservoir levels, generation will be controlled based on minimum discharge flow requirements, and reservoirs will focus on storing water to raise levels during the subsequent flood season, ensuring future watershed water supply needs [

30,

31]. Accordingly, the operational dispatch must consider maintaining water levels within a reasonable range during this season:

where

is the reservoir water level of hydropower station

m at time interval

t;

are upper and lower limits for the water level of hydropower station

m at time interval

t;

A is the set of time intervals encompassing the water supply season (April to May).

Given that hydropower contributes only a small share in the region and mainly operates under multi-year reservoir rules, the seasonal water-level limits implicitly account for the hydrologic continuity relationship.

3.3.4. Operational Modes and Constraints of Pumped Storage Power Stations

The operating modes of pumped storage units are characterized by distinct power levels in each mode. The pumping load is typically constant at the unit’s rated capacity, while the generation output can be varied between the minimum technical output and the rated capacity. Furthermore, operational constraints are established by considering the upper reservoir’s regulation storage capacity, the rated pumping/generation flow rates, and the total installed capacity of the units. These factors determine the maximum durations for continuous pumping and generation under different operational scenarios, leading to the following constraints:

where

Pps,r is the total rated capacity of all pumped storage units in the power grid;

Pps,min is the minimum technical output of a pumped storage unit in generation mode.

It should be noted that the installed capacity of energy storage (e.g., batteries) in the Northeast China Power Grid is currently limited. Therefore, in this model, such storage is equivalently represented based on its rated power and energy capacity and incorporated into the pumped storage considerations described above [

32]. This approach will not be elaborated upon further. For pumped storage, the practical operating boundaries already embed the energy-balance requirements, so an explicit continuity equation is not modeled separately.

3.3.5. Operational Modes and Constraints of Nuclear Power Plants

Considering unit maintenance schedules and the two-level deep peak regulation capability, the operational constraints for nuclear power are defined as follows. The upper output limit is the total online nuclear capacity, while the lower limit is its second-level deep regulation output. However, due to fuel constraints, the duration of second-level deep regulation operation must not exceed 6 h continuously. First-level deep regulation can be sustained indefinitely, but a minimum interval of 24 h is required between the start times of successive power reductions from full output for deep regulation.

The nuclear power output constraints are formulated as follows:

where

Pn,min,t is the total second-level deep peak regulation output of all nuclear units in the power grid at time interval

t;

is the continuous duration of second-level peak regulation operation for nuclear units (hours);

is the time interval between the start times of two successive power reductions for deep regulation of nuclear units (hours).

3.3.6. Line Operation Constraints

External connections (Gaoling back-to-back, Heihe HVDC, Zhalute–Qingzhou HVDC) are modeled using aggregate transmission limits (MW) and scheduled import/export curves. Power flow on each corridor is constrained as

4. Case Studies

4.1. Case 1 Validation of New Energy Integration Accuracy Using 2024 Operational Data

The integration assessment model was validated using actual 2024 grid data. The inputs included the real load profile, inter-regional power delivery schedules, the available new energy output sequences (after accounting for curtailment), maintenance schedules for various power sources, and newly installed capacity. The model calculated the annual new energy generation and curtailed energy.

The results show close alignment between simulated and actual values:

The simulation results for wind power showed a generation of 149.32 TWh with 9.19 TWh of curtailment, yielding a utilization rate of 94.2%, while the actual recorded values were 149.77 TWh of generation, 8.74 TWh of curtailment, and a 94.5% utilization rate.

For solar power, the model simulated a generation of 39.01 TWh against 0.96 TWh of curtailment, resulting in a 97.6% utilization rate, compared to the actual performance of 38.84 TWh generation, 1.13 TWh curtailment, and a 97.2% utilization rate.

Regarding total new energy, the simulation produced 188.33 TWh of generation with 10.15 TWh curtailed, achieving a 94.9% utilization rate, whereas the actual grid operation delivered 188.61 TWh of generation, 9.87 TWh of curtailment, and a 95.0% utilization rate.

These validation results, summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, demonstrate that the model’s calculations are consistent with the actual integration data, thereby verifying the accuracy of the integration assessment model. A quantitative indicator was also added, and the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of the annual new energy results was 4.89%, further illustrating the model’s overall computational accuracy.

As shown in

Figure 3, it can be seen from the annual time series diagram that the two still have a high degree of similarity. From the perspective of seasonal characteristics, the overall output of new energy in spring is relatively high, while the load is relatively mild. Summer peak load is more prominent in the power system. The output of thermal power and hydropower increases to meet the electricity demand. The new energy fluctuates more due to rainfall and wind conditions, but it can still be well absorbed overall. In autumn, the fluctuations in wind and solar resources are significant, and the load slightly declines. The frequency of pumped storage’s participation in regulation increases, demonstrating the system’s balancing capacity. Winter load rises again. Thermal power and nuclear power maintain stable output. New energy slightly declines due to the influence of low-wind days and short days, but the supply and demand balance is maintained through energy storage and hydropower regulation.

Overall, the power system achieved stable operation under the high penetration of new energy in 2024. The seasonal characteristics are obvious. The contribution peak of new energy power generation is in spring and autumn. Reservoir power generation is mainly concentrated in the flood season, and it undertakes the task of stable power output in other periods. Thermal power, nuclear power and pumped storage form a stable pressure support. The system has a relatively strong emphasis on energy conservation and flexibility.

In addition, a month-by-month comparison of the simulated and actual 2024 generation results is included (

Table 3 and

Table 4). These monthly values supplement the annual indicators and provide a clearer view of the model’s ability to reflect basic seasonal operational characteristics. The overall consistency between the simulated and recorded monthly outputs further supports that the sequential model reasonably represents the system’s operational constraints.

4.2. Case 2 Long-Term Time-Series Power Balance Calculation Using Forecasted Data for the Next Year

The grid’s load demand for the next year was projected by uniformly scaling the actual 2024 load data based on a 3% growth rate. The inter-regional power delivery schedule utilized the actual 2024 power export time series. Wind and solar resource data were based on the average resource levels from the past three years. The wind and PV power output time series for the next year were generated by combining the 2024 available output profiles, the aforementioned average resource levels, and the projected newly installed wind and PV capacity for the regional grid in the next year. Maintenance schedules for all generation types were incorporated according to the next year’s maintenance plan. New installations for thermal power, hydropower, and pumped storage, as well as flexibility retrofit capacities for thermal power, were considered based on the next-year new equipment commissioning plan. These boundary conditions were input into the new energy integration analysis model to calculate the annual new energy generation and curtailed energy for the next year. The calculation results are presented in

Table 5.

Regarding the new energy utilization rate, with the rapid growth of installed new energy capacity outpacing the increases in both load demand and system flexibility, the utilization rate in the Northeast China Power Grid is projected to decline further in the next year, dropping from 95% in 2024 to 90.6%. This historical trend is illustrated in

Figure 4. Consequently, the curtailed energy from wind and PV is also expected to rise significantly, increasing from 9.7 billion kWh to 23.4 billion kWh. In addition,

Figure 5 also shows that a certain amount of new energy power will be abandoned in spring, summer and autumn.

In terms of curtailment causes, the grid is forecasted to experience 18.6 billion kWh of curtailment due to insufficient peak-shaving capacity and 4.8 billion kWh caused by grid congestion in the next year, representing year-on-year increases of 11.5 billion kWh and 2.0 billion kWh, respectively. As shown in

Figure 6, following its emergence as the primary constraint in 2024, curtailment due to peak-shaving limitations is expected to intensify further in the next year. The ratio of curtailment attributable to peak-shaving constraints versus grid congestion is projected to widen from 7:3 to 8:2.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis of New Energy Integration Results

To rationally plan the scale, timing, and layout of new energy deployment and accelerate the construction of system flexibility resources, this study calculated the changes in the next year′s new energy integration under different scenarios of installed new energy capacity and energy storage capacity. This quantifies the impact of both new energy installation scale and system flexibility on integration outcomes. Specifically, the new energy installed capacity was varied by −10% and +10% from the base case. The energy storage capacity was configured at levels equivalent to 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25% of the newly added new energy capacity. The results are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

As can be seen from

Table 6, a significant negative correlation exists between the new energy utilization rate and the scale of newly installed capacity. As installed new energy capacity increases, the utilization rate declines rapidly. Compared to the base case, when newly installed capacity is reduced by 10%, the utilization rate increases by 1.2 percentage points; when newly installed capacity is increased by 10%, the utilization rate decreases by 1.6 percentage points.

As shown in

Table 7, a distinct positive correlation exists between the new energy utilization rate and the installed energy storage capacity, with the utilization rate rising progressively as storage deployment increases. In the base case, where energy storage capacity represents 6% of the total installed new energy capacity, the utilization rate serves as the benchmark. When the storage allocation is reduced to 5% of the new energy capacity, the utilization rate drops by 0.3 percentage points. Conversely, increasing the storage allocation to 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25% of the new energy capacity raises the utilization rate by 0.8, 1.3, 1.7, and 2.0 percentage points, respectively.

These results provide a scientific basis for planning departments, supporting the rational planning of new energy deployment scale and the expansion of energy storage infrastructure to effectively promote the efficient utilization of new energy.