Synthesis, Optical, Electrical, and Thermoelectric Characterization of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

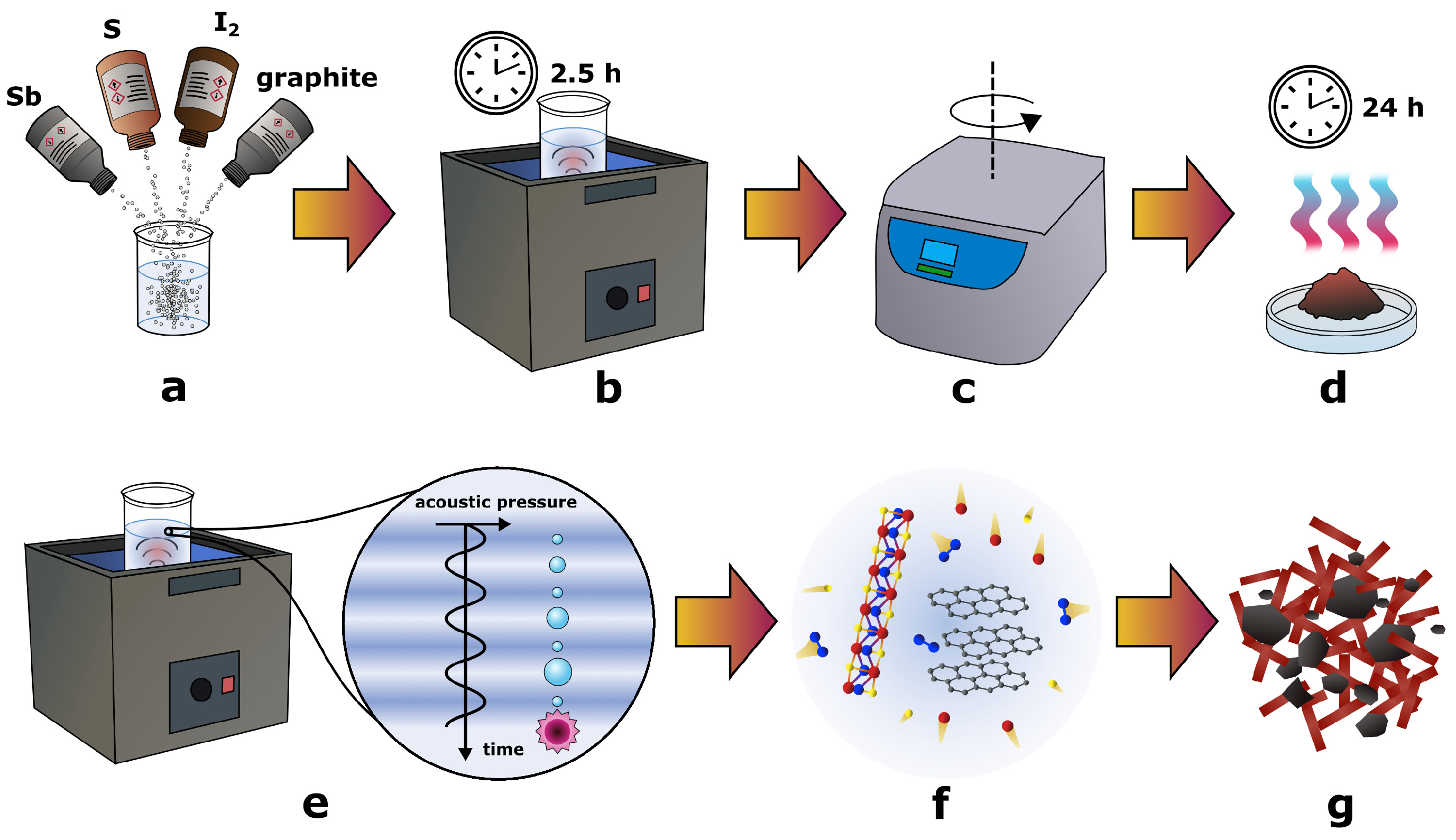

2.1. Sonochemical Synthesis of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite

2.2. Characterization of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite Morphology, Chemical Composition, and Optical Properties

2.3. Examination of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite Electrical and Thermoelectric Properties

3. Results and Discussion

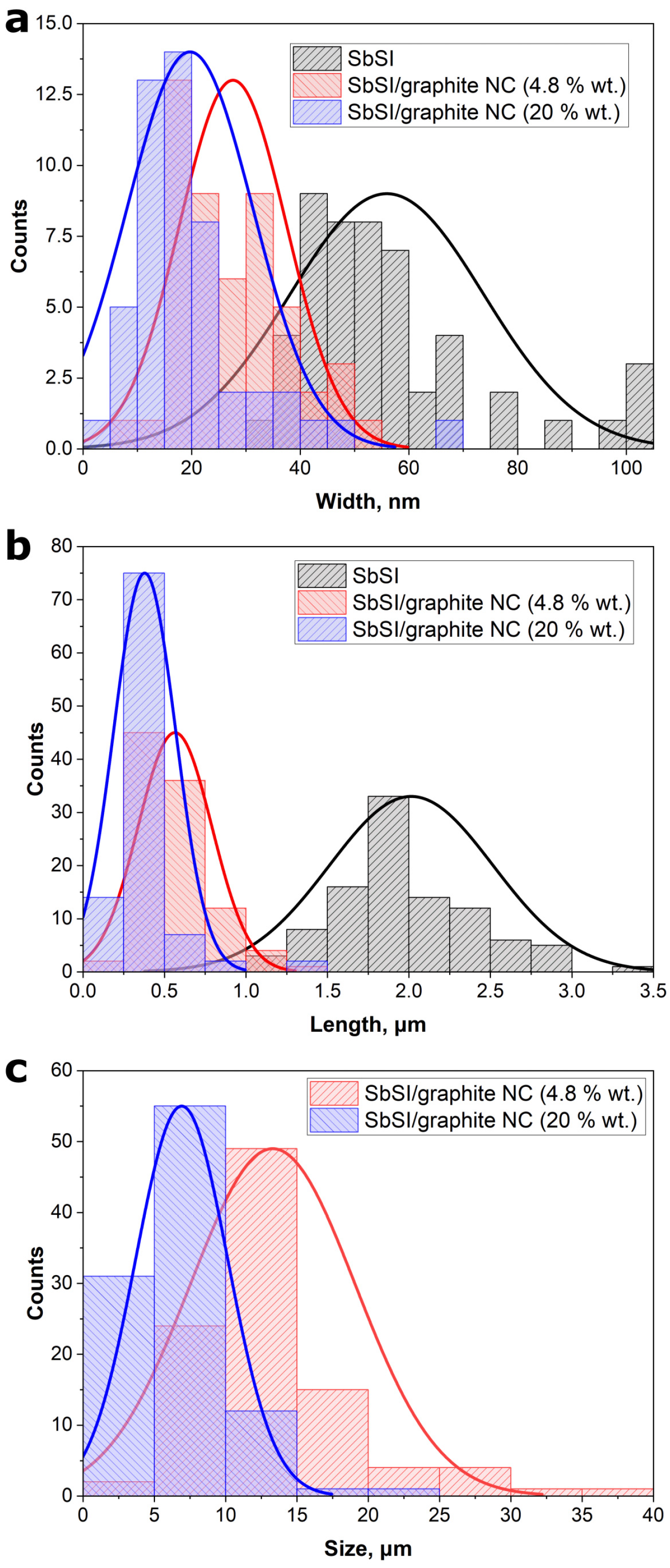

3.1. SEM, EDS, and DRS Investigations

3.2. Electrical and Thermoelectric Examination

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNTs | carbon nanotubes |

| DRS | diffuse reflectance spectroscopy |

| EDS | energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| NC | nanocomposite |

| NRs | nanorods |

| NWs | nanowires |

| PAN | polyacrylonitrile |

| PEDOT | poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) |

| PSS | poly(styrenesulfonate) |

| RH | relative humidity |

| SbSI | antimony sulfoiodide |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| UPS | ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy |

References

- Wlaźlak, E.; Blachecki, A.; Bisztyga-Szklarz, M.; Klejna, S.; Mazur, T.; Mech, K.; Pilarczyk, K.; Przyczyna, D.; Suchecki, M.; Zawal, P.; et al. Heavy pnictogen chalcohalides: The synthesis, structure and properties of these rediscovered semiconductors. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistewicz, K. Introduction, in Low-Dimensional Chalcohalide Nanomaterials; Mistewicz, K., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, H.; Palaz, S.; Mamedov, A.M.; Ozbay, E. Optical, electronic, and elastic properties of some A5B6C7 ferroelectrics (A = Sb, Bi; B = S, Se; C = I, Br, Cl): First principle calculation. Ferroelectrics 2017, 511, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, R.; Xiao, B.; Li, F.; Liu, X.; Xi, S.; Zhu, M.; Jie, W.; Zhang, B.B.; Xu, Y. Growth of bismuth- and antimony-based chalcohalide single crystals by the physical vapor transport method. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 1094. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Yi, G.C. Sbsi microrod based flexible photodetectors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 345106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Feeney, T.; Mendes, J.O.; Krishnamurthi, V.; Walia, S.; Della Gaspera, E.; van Embden, J. High Gain Solution-Processed Carbon-Free BiSI Chalcohalide Thin Film Photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazon, F. Metal Chalcohalides: Next Generation Photovoltaic Materials? Sol. RRL 2022, 6, 2100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistewicz, K.; Matysiak, W.; Jesionek, M.; Jarka, P.; Kępińska, M.; Nowak, M.; Tański, T.; Stróż, D.; Szade, J.; Balin, K.; et al. A simple route for manufacture of photovoltaic devices based on chalcohalide nanowires. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 517, 146138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembo, R.O.; Ratshiedana, R.; Madikizela, L.M.; Kamika, I.; King’ondu, C.K.; Kuvarega, A.T.; Msagati, T.A.M. Enhancing light-driven photocatalytic reactions through solid solutions of bismuth oxyhalide/bismuth rich photocatalysts: A systematic review. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.-Q. Bismuth oxyhalide photocatalysts for water purification: Progress and challenges. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 493, 215339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorpade, U.V.; Suryawanshi, M.P.; Green, M.A.; Wu, T.; Hao, X.; Ryan, K.M. Emerging Chalcohalide Materials for Energy Applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Feng, N.B.; Huang, X.H.; Yao, Y.; Jin, Y.R.; Pan, W.; Liu, D. Humidity-Sensing Properties of a BiOCl-Coated Quartz Crystal Microbalance. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 18818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatuzzo, E.; Harbeke, G.; Merz, W.J.; Nitsche, R.; Roetschi, H.; Ruppel, W. Ferroelectricity in SbSI. Phys. Rev. 1962, 127, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, A.S.; Newnham, R.E.; Cross, L.E.; Dougherty, J.P.; Smith, W.A. Pyroelectricity in SbSI. Ferroelectrics 1981, 33, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamano, K.; Shinmi, T. Electrostriction, Piezoelectricity and Elasticity in Ferroelectric SbSI. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1972, 33, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purusothaman, Y.; Alluri, N.R.; Chandrasekhar, A.; Kim, S.J. Photoactive piezoelectric energy harvester driven by antimony sulfoiodide (SbSI): A AVBVICVII class ferroelectric-semiconductor compound. Nano Energy 2018, 50, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, H.; Zheng, Y. Two-dimensional Janus SbTeBr/SbSI heterostructures as multifunctional optoelectronic systems with efficient carrier separation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Nishikubo, R.; Chen, Y.; Marumoto, K.; Saeki, A. Wavelength-Recognizable SbSI:Sb2S3 Photovoltaic Devices: Elucidation of the Mechanism and Modulation of their Characteristics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2311794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lin, S.; He, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hu, K.; Sun, H.; Liu, X. Synergetic piezo-photocatalytic effect in SbSI for highly efficient degradation of methyl orange. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 31818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Hajra, S.; Panda, S.; Hwang, S.; Kim, N.; Jo, J.; Vittayakorn, N.; Mistewicz, K.; Joon Kim, H. Antimony Sulfoiodide-Based Energy Harvesting and Self-Powered Temperature Detection. Energy Technol. 2024, 12, 2301125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.S.; Mansingh, A. Electrical and Optical Properties of SbSI Films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 24, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.S.; Mansingh, A. Electrical properties of antimony sulphoiodide (SbSI) thin films. Ferroelectrics 1989, 93, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Hussain, S.; Minar, J.; Azam, S. Electronic and Thermoelectric Properties of Ternary Chalcohalide Semiconductors: First Principles Study. J. Electron. Mater. 2018, 47, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Xu, K.; Zhang, H.; Ning, Z.; Shao, H.; Ni, G.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Soukoulis, C.M. 1D SbSeI, SbSI, and SbSBr With High Stability and Novel Properties for Microelectronic, Optoelectronic, and Thermoelectric Applications. Adv. Theory Simul. 2018, 1, 1700005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.B.; Lau, K.; Hui, D.; Bhattacharyya, D. Graphene-based materials and their composites: A review on production, applications and product limitations. Compos. B Eng. 2018, 142, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; Tehrani-Bagha, A.R. Advances in Preparation Methods and Conductivity Properties of Graphene-based Polymer Composites. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2023, 30, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Sun, M.; Han, P. A review of the preparation and applications of graphene/semiconductor composites. Carbon 2014, 70, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.; Sharma, A.; Raj, S.A.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Hui, D.; Shah, A.U.M. Contemporary review on carbon nanotube (CNT) composites and their impact on multifarious applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 2632–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, E.W.; Mebratie, B.A. Advancements in carbon nanotube-polymer composites: Enhancing properties and applications through advanced manufacturing techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yang, H.; Cheng, J.; Hu, C.; Wu, Z.; Feng, Y. Review in preparation and application of nickel-coated graphite composite powder. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 862, 158014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xing, H.; Fan, Y.; Wei, Y.; Shang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J. SiOx-based graphite composite anode and efficient binders: Practical applications in lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellett, C.; Ghosh, K.; Browne, M.P.; Urbanová, V.; Pumera, M. Flexible Graphite–Poly(Lactic Acid) Composite Films as Large-Area Conductive Electrodes for Energy Applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, F. Three-phase composite conductive concrete for pavement deicing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jała, J.; Nowacki, B.; Mistewicz, K.; Gradoń, P. Graphite-epoxy composite systems for Joule heating based de-icing. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 216, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, L.; Kötzsch, T.; Noack, T.J.; Oeckler, O. Decomposition behavior and thermoelectric properties of copper selenide—Graphite composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 122, 083901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Li, J.; Pan, C.; Wang, L.; Bai, X. Preparation and Characterization of Bi2Te3/Graphite/Polythiophene Thermoelectric Composites. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, M.; Kim, G.; Kennedy, G.P.; Roth, S.; Dettlaff-Weglikowska, U. Preparation and characterization of expanded graphite polymer composite films for thermoelectric applications. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 2013, 250, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, F.; Dixit, P.; Maiti, T. Enhanced thermoelectric performance with improved mechanical strength in Bi2S3/graphite composites. Carbon 2024, 218, 118692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhou, H.; Mu, X.; He, D.; Ji, P.; Hou, W.; Wei, P.; Zhu, W.; Nie, X.; Zhao, W. Preparation and Thermoelectric Properties of Graphite/Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3 Composites. J. Electron. Mater. 2018, 47, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitha, P.A.; Shankar, M.R.; Prabhu, A.N.; Nayak, R.; Rao, A.; Poojitha, G. Fabrication and characterisation of a flexible thermoelectric generator using PANI/graphite/bismuth telluride composites. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 40117. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Singha, P.; Deb, A.K.; Das, S.C.; Chatterjee, S.; Kulbachinskii, V.A.; Kytin, V.G.; Zinoviev, D.A.; Maslov, N.V.; Dhara, S.; et al. Role of graphite on the thermoelectric performance of Sb2Te3/graphite nanocomposite. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 125, 195105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, M.; Kim, H.Y.; Ding, B.; Park, S.J. A facile ultrasonic-assisted fabrication of nitrogen-doped carbon dots/BiOBr up-conversion nanocomposites for visible light photocatalytic enhancements. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Jiang, G.; Chen, H.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Chen, W. Hierarchical nanostructures of BiOBr/AgBr on electrospun carbon nanofibers with enhanced photocatalytic activity. MRS Commun. 2016, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Qi, Y.; Qi, X.; Ren, J.; Yuan, B.; Ni, B.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, J.; et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of carbon spheres—BiOI/BiOIO3 heterojunctions for photocatalytic removal of gaseous Hg0 under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 304, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Jiang, K.; Shen, M.; Wei, R.; Wu, X.; Idrees, F.; Cao, C. Micro and nano hierachical structures of BiOI/activated carbon for efficient visible-light-photocatalytic reactions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frutos, M.M.; Barthaburu, M.E.P.; Fornaro, L.; Aguiar, I. Bismuth chalcohalide-based nanocomposite for application in ionising radiation detectors. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 225710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Szperlich, P.; Bober; Szala, J.; Moskal, G.; Stróz, D. Sonochemical preparation of SbSI gel. Ultrason. Sonochem 2008, 15, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasui, K. Fundamentals of acoustic cavitation and sonochemistry. In Theoretical and Experimental Sonochemistry Involving Inorganic Systems; Ashokkumar, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Tao, R.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y. Sonochemistry: Materials science and engineering applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 526, 216373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Alehossein, H. Heat transfer during cavitation bubble collapse. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 105, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-T.; Sagar, H.J.; el Moctar, O.; Park, W.-G. Understanding cavitation bubble collapse and rebound near a solid wall. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 278, 109473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankaj. Aqueous inorganic sonochemistry. In Theoretical and Experimental Sonochemistry Involving Inorganic Systems; Ashokkumar, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 213–271. [Google Scholar]

- Okitsu, K.; Cavalieri, F. Synthesis of metal nanomaterials with chemical and physical effects of ultrasound and acoustic cavitation. In Sonochemical Production of Nanomaterials; Okitsu, K., Cavalieri, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, I.; Min, B.K.; Joo, S.W.; Sohn, Y. One-dimensional single crystalline antimony sulfur iodide, SbSI. Mater. Lett. 2012, 86, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, W.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Q. Fast and low-temperature synthesis of one-dimensional (1D) single-crystalline SbSI microrod for high performance photodetector. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 21859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.K.; Prasad, M.D.; Batabyal, S.K. One-dimensional SbSI crystals from Sb, S, and I mixtures in ethylene glycol for solar energy harvesting. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process 2019, 125, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, J.A.; Kaur, A.; Khavari, M.; Tyurnina, A.V.; Priyadarshi, A.; Eskin, D.G.; Mi, J.; Porfyrakis, K.; Prentice, P.; Tzanakis, I. An eco-friendly solution for liquid phase exfoliation of graphite under optimised ultrasonication conditions. Carbon 2023, 204, 434. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, S.; Pandey, R.K. Physical Vapor Deposition of Antimony Sulpho-Iodide (SbSI) Thin Films and Their Properties. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Applications of Ferroelectrics, University Park, PA, USA, 7–10 August 1994; pp. 309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Fang, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, Q.; Sheng, X.; Xu, X.; Hui, J.; Lan, Y.; Fang, M.; et al. SbSI Nanocrystals: An Excellent Visible Light Photocatalyst with Efficient Generation of Singlet Oxygen. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 12166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.-M.; Jiang, L.-T.; Liu, B.-W.; Guo, G.-C. A new salt-inclusion chalcogenide exhibiting distinctive [Cd11In9S26]3− host framework and decent nonlinear optical performances. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 902, 163656. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Xu, L.; Kong, X.; Kusunose, T.; Tsurumachi, N.; Feng, Q. Bismuth chalcogenide iodides Bi13S18I2 and BiSI: Solvothermal synthesis, photoelectric behavior, and photovoltaic performance. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2020, 8, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.K.; Mohan, A.C.; Batabyal, S.K. Bismuth sulfoiodide (BiSI) for photo-chargeable charge storage device. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process 2022, 128, 298. [Google Scholar]

- Mistewicz, K.; Nowak, M.; Stróż, D. A Ferroelectric-Photovoltaic Effect in SbSI Nanowires. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwolek, P.; Pilarczyk, K.; Tokarski, T.; Mech, J.; Irzmański, J.; Szaciłowski, K. Photoelectrochemistry of n-type antimony sulfoiodide nanowires. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makuła, P.; Pacia, M.; Macyk, W. How to Correctly Determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV–Vis Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justinabraham, R.; Sowmya, S.; Durairaj, A.; Sakthivel, T.; Wesley, R.J.; Vijaikanth, V.; Vasanthkumar, S. Synthesis and characterization of SbSI modified g-C3N4 composite for photocatalytic and energy storage applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 935, 168115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inico, E.; Saetta, C.; Di Liberto, G. Impact of quantum size effects to the band gap of catalytic materials: A computational perspective*. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2024, 36, 361501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasviri, M.; Sajadi-Hezave, Z. SbSI nanowires and CNTs encapsulated with SbSI as photocatalysts with high visible-light driven photoactivity. Mol. Catal. 2017, 436, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, D.; Dong, W.; Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Kong, D.; Jia, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Chemical vapor deposition synthesis of intrinsic van der Waals ferroelectric SbSI nanowires. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 9756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Yamanaka, K.; Hamakawa, Y. Semiconducting and dielectric properties of c-axis oriented sbsi thin film. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1973, 12, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prunet, G.; Pawula, F.; Fleury, G.; Cloutet, E.; Robinson, A.J.; Hadziioannou, G.; Pakdel, A. A review on conductive polymers and their hybrids for flexible and wearable thermoelectric applications. Mater. Today Phys. 2021, 18, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajima, T.; Ogawa, K.; Nagano, H.; Yamazaki, T.; Tsuruta, A.; Shin, W. Verification of high throughput simultaneous measurement for Seebeck coefficient, resistivity, and thermal diffusivity of thermoelectric materials. Measurement 2023, 223, 113746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, P.A.; Maragoni, L.; Paipetis, A.S.; Quaresimin, M.; Tzounis, L.; Zappalorto, M. Prediction of the Seebeck coefficient of thermoelectric unidirectional fibre-reinforced composites. Compos. B Eng. 2021, 223, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naim, A.F.; El-Shamy, A.G. Review on recent development on thermoelectric functions of PEDOT:PSS based systems. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process 2022, 152, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousar, H.S.; Srivastava, D.; Karttunen, A.J.; Karppinen, M.; Tewari, G.C. p-type to n-type conductivity transition in thermoelectric CoSbS. APL Mater. 2022, 10, 091104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Jia, X.; Xiang, X.; Ho, C.-L.; Wong, W.-Y.; Li, H. Preparation and thermoelectric properties of diphenylaminobenzylidene-substituted poly(3-methylthiophene methine)/graphite composite. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 62096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Tai, G.; Guo, W. Enhanced gas-flow-induced voltage in graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 073103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yin, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Q.; Guo, W. Exceptional high Seebeck coefficient and gas-flow-induced voltage in multilayer graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 183108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoi, Y.M.; Chung, D.D.L. Flexible graphite as a compliant thermoelectric material. Carbon 2002, 40, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culebras, M.; Gómez, C.M.; Cantarero, A. Thermoelectric measurements of PEDOT:PSS/expanded graphite composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, G.-S.; Yu, Z.-Z.; Qi, J.-S. The effect of graphite oxide on the thermoelectric properties of polyaniline. Carbon 2012, 50, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Zhu, G.; Li, J.; Pan, F. Thermoelectric properties of conducting polyaniline/graphite composites. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, P.; Das, S.; Kulbachinskii, V.A.; Kytin, V.G.; Apreleva, A.S.; Voneshen, D.J.; Guidi, T.; Powell, A.V.; Chatterjee, S.; Deb, A.K.; et al. Evidence of improvement in thermoelectric parameters of n-type Bi2Te3/graphite nanocomposite. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 055108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starczewska, A.; Mistewicz, K.; Kozioł, M.; Zubko, M.; Stróż, D.; Dec, J. Interfacial Polarization Phenomena in Compressed Nanowires of SbSI. Materials 2022, 15, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistewicz, K.; Nowak, M.; Starczewska, A.; Jesionek, M.; Rzychoń, T.; Wrzalik, R.; Guiseppi-Elie, A. Determination of electrical conductivity type of SbSI nanowires. Mater. Lett. 2016, 182, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Talik, E.; Szperlich, P.; Stróz, D. XPS analysis of sonochemically prepared SbSI ethanogel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; Yun, H.S.; Paik, M.J.; Mehta, A.; Park, B.W.; Choi, Y.C.; Seok, S.I. Efficient Solar Cells Based on Light-Harvesting Antimony Sulfoiodide. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1701901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Average Size of Particles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SbSI Nanowires | Graphite Flakes | ||

| Width, nm | Length, µm | Size, µm | |

| SbSI NWs | 56(18) | 2.01(50) | – |

| SbSI/graphite NC (4.8 wt.% graphite) | 28(10) | 0.56(23) | 13.3(58) |

| SbSI/graphite NC (20 wt.% graphite) | 20(12) | 0.38(19) | 6.9(32) |

| Element | Concentration of Elements | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Detected Elements | Components Without Si | |||

| at., % | wt., % | at., % | wt., % | |

| silicon | 63.6 | 44.4 | – | – |

| carbon | 15.8 | 4.7 | 43.5 | 8.5 |

| antimony | 8.0 | 24.1 | 22.0 | 43.4 |

| sulfur | 5.5 | 4.4 | 15.0 | 7.8 |

| iodine | 7.1 | 22.4 | 19.5 | 40.3 |

| Material | Synthesis Method | Eg, eV | Energy Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SbSI/PAN NC | sonochemical | 1.81 | indirect | [8] |

| SbSI NRs | hydrothermal | 1.877 | direct | [66] |

| SbSI/g-C3N4 NC (5 wt.% SbSI) | hydrothermal | 2.755 | direct | [66] |

| SbSI/g-C3N4 NC (15 wt.% SbSI) | hydrothermal | 2.718 | direct | [66] |

| SbSI/g-C3N4 NC (25 wt.% SbSI) | hydrothermal | 2.652 | direct | [66] |

| SbSI encapsulated in CNTs | sonochemical | 1.86 | indirect | [68] |

| SbSI NWs | sonochemical | 1.862 | indirect | [63] |

| SbSI NWs | sonochemical | 1.91 | indirect | [64] |

| SbSI NWs | sonochemical | 1.94(2) | indirect | this work |

| SbSI/graphite NC (4.8 wt.% graphite) | sonochemical | 2.00(2) | indirect | |

| SbSI/graphite NC (20 wt.% graphite) | sonochemical | 2.03(3) | indirect |

| Graphite Concentration, wt.% | S, µV/K | σ, mS/m | PF, pW/(K2∙m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 106.2(8) | 5.9(3)∙10−4 | 0.0067(1) |

| 4.8 | 1.84(1) | 3.2(2) | 0.0108(1) |

| 11.1 | 2.48(9) | 25.8(7) | 0.16(1) |

| 20.0 | 2.41(2) | 7.4(2) | 0.0428(7) |

| 33.3 | 0.70(1) | 49.9(4) | 0.0242(6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nowacki, B.; Mistewicz, K.; Jała, J.; Kozioł, M.; Smalcerz, A. Synthesis, Optical, Electrical, and Thermoelectric Characterization of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite. Energies 2026, 19, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010009

Nowacki B, Mistewicz K, Jała J, Kozioł M, Smalcerz A. Synthesis, Optical, Electrical, and Thermoelectric Characterization of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite. Energies. 2026; 19(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowacki, Bartłomiej, Krystian Mistewicz, Jakub Jała, Mateusz Kozioł, and Albert Smalcerz. 2026. "Synthesis, Optical, Electrical, and Thermoelectric Characterization of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite" Energies 19, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010009

APA StyleNowacki, B., Mistewicz, K., Jała, J., Kozioł, M., & Smalcerz, A. (2026). Synthesis, Optical, Electrical, and Thermoelectric Characterization of SbSI/Graphite Nanocomposite. Energies, 19(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010009