Design and Analysis of Combining Oil-Cooling Scheme of S-Shaped and End-Spraying Passages for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design and Parameter Optimization of S-Shaped Axial Returning Passage

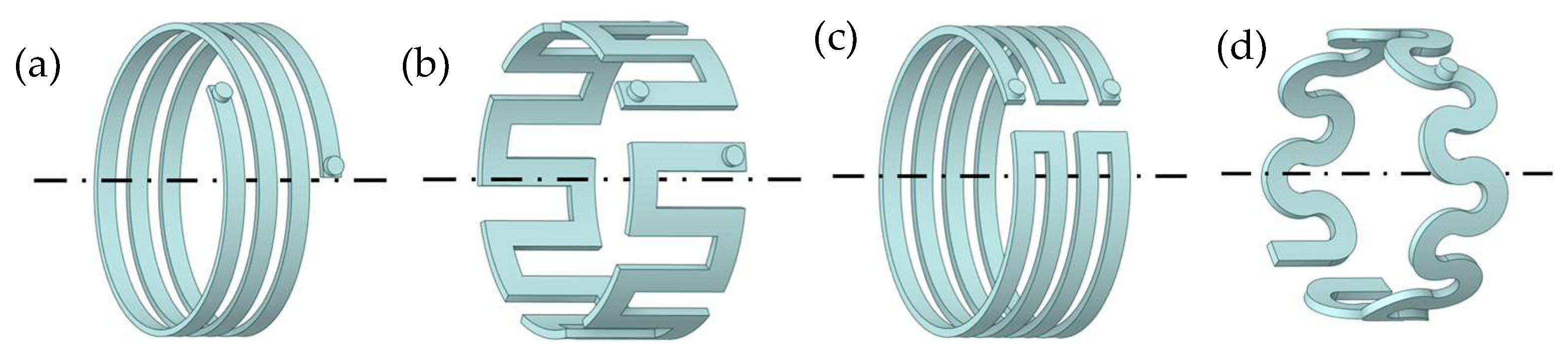

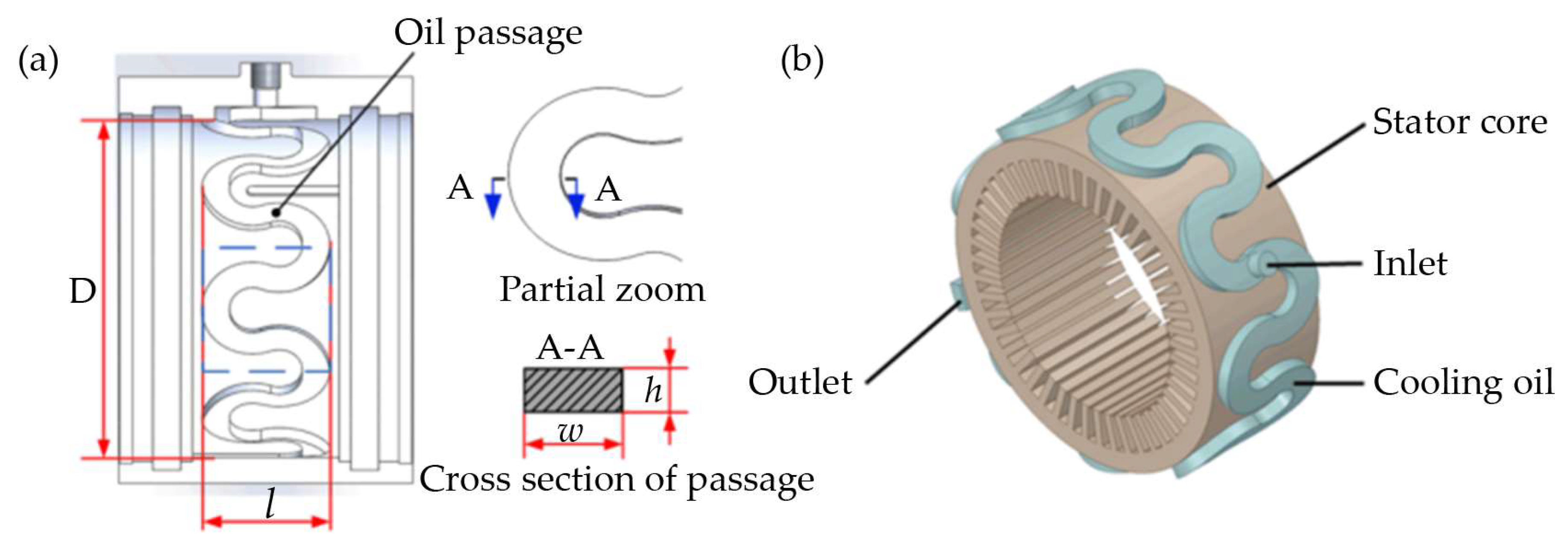

2.1. Design of the S-Shaped Axial Returning Passage

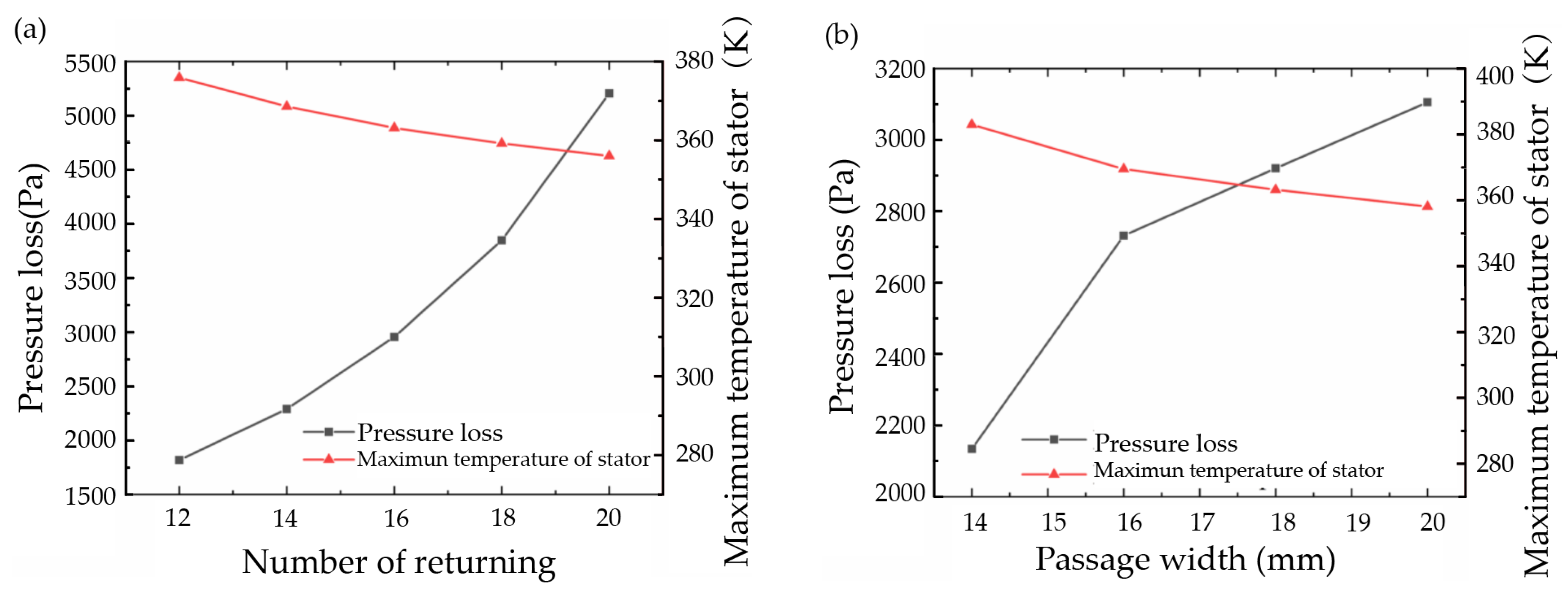

2.2. Geometric Parameter Optimization of the S-Shaped Passage

2.3. Comparison Analysis of Pressure Loss and Heat Transfer Coefficient

3. Combining Oil-Cooling Scheme of S-Shaped and End-Spraying Passages

3.1. Introduction of Combining Oil-Cooling Scheme

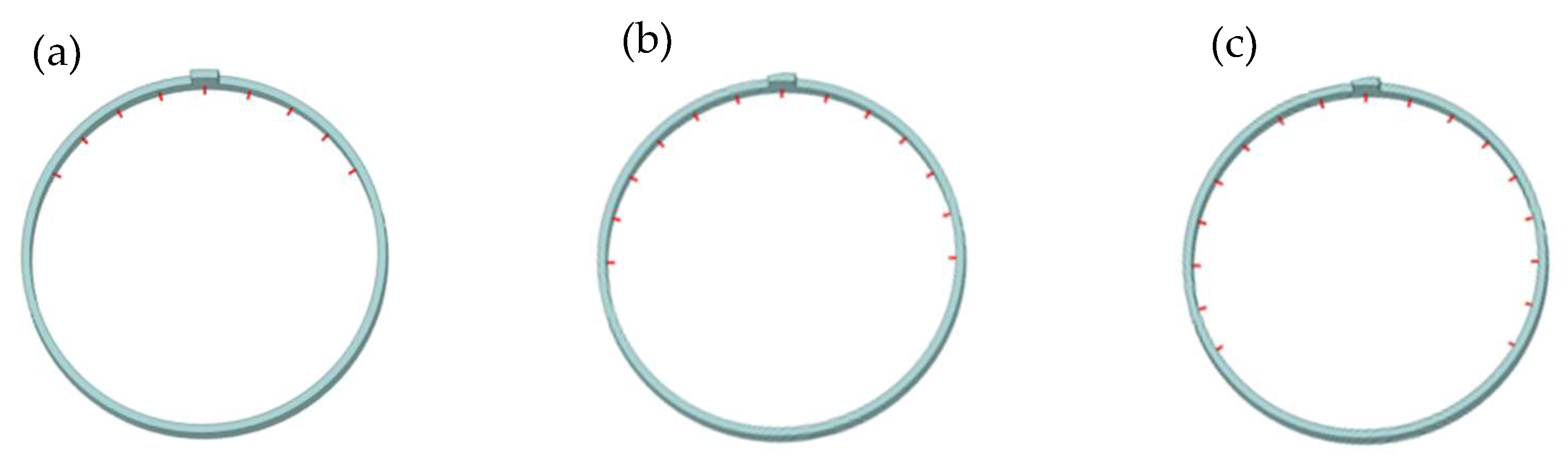

3.2. Nozzle Arrangements on the Oil-Spraying Ring

4. Structural Design and Temperature Distribution

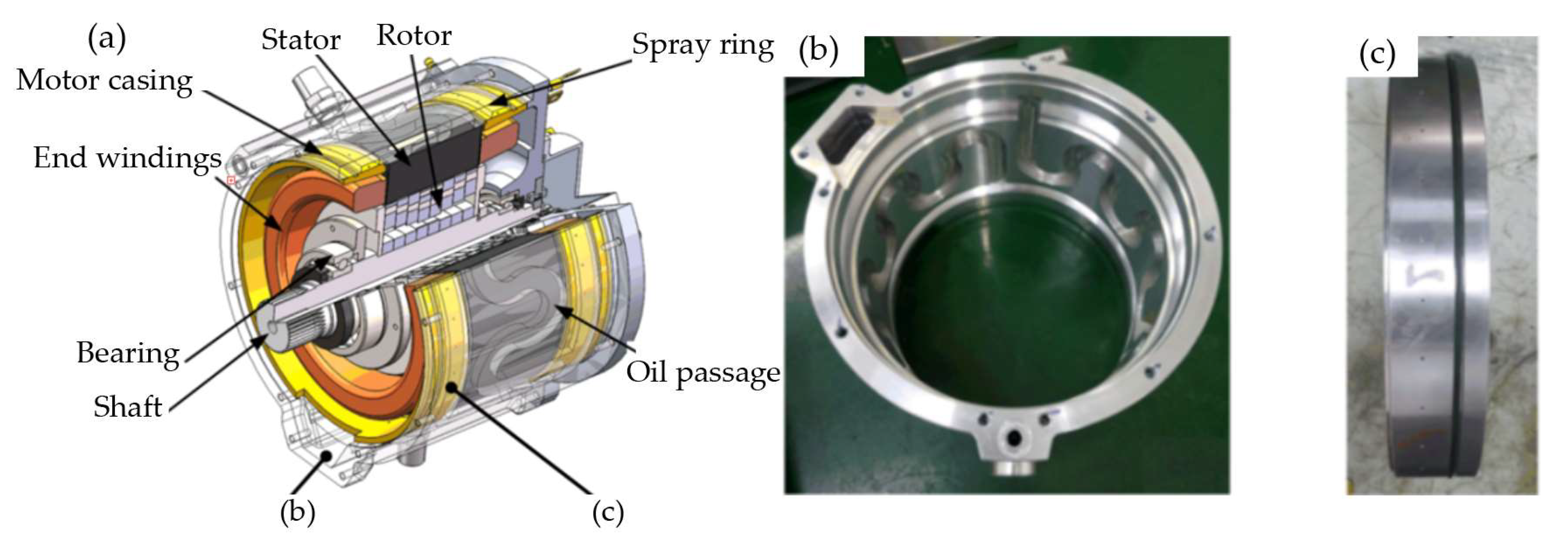

4.1. Structure Design of PMSM with Combining Cooling System

4.2. Finite-Element Modeling and Simulation Setup

- (1).

- Heat transfer function

- (2).

- Fluid control equation

- (3).

- Establishment of simulation model

- (a).

- The winding and iron core were treated as a single equivalent body with uniform heat generation and anisotropic thermal conductivity.

- (b).

- The cooling oil was supplied to the motor uniformly at a constant temperature and velocity.

- (c).

- Thermal radiation was neglected during the temperature-rise simulation.

- (d).

- Structural features such as ribs, filets, and grooves that have negligible influence on motor temperature rise were removed.

- (e).

- The heat transfer coefficient and thermal conductivity of all components were assumed to be constant.

- (4).

- Simulation Parameter Setting

- (a)

- In the CFD model, the cooling oil was used as the working fluid, and a velocity inlet was specified according to the prescribed flow rates of 8 L/min, 12 L/min, and 16 L/min, with the inlet temperature maintained at 65 °C. The outlet was defined as a pressure boundary at standard atmospheric pressure. All fluid–solid interfaces, including the housing–oil and stator–oil contact surfaces, were modeled as conjugate heat transfer interfaces to allow heat exchange across domains, while the remaining walls were treated as adiabatic. A 0.3 mm insulation layer was assigned to the winding–stator interface to account for the thermal resistance of the actual structure.

- (b)

- Although the flow path includes S-shaped bends and narrow passages, the Reynolds number calculated based on the oil properties and hydraulic diameter indicates laminar flow; therefore, a laminar flow model was employed. The machined channel surfaces were assumed to be hydraulically smooth, consistent with conventional industrial practice.

- (c)

- A high-quality unstructured mesh was generated for the oil domain, and geometric features with negligible thermal influence were removed to improve mesh quality. Node sharing was enforced across all fluid–solid interfaces to ensure accurate heat transfer. The final mesh contained approximately 3.09 million nodes and 12.02 million elements, with an average skewness of 0.218. Mesh sensitivity was examined by progressively refining the mesh, and the results were considered mesh-independent when the variations in pressure drop and winding temperature were below 2%.

4.3. Temperature Distribution

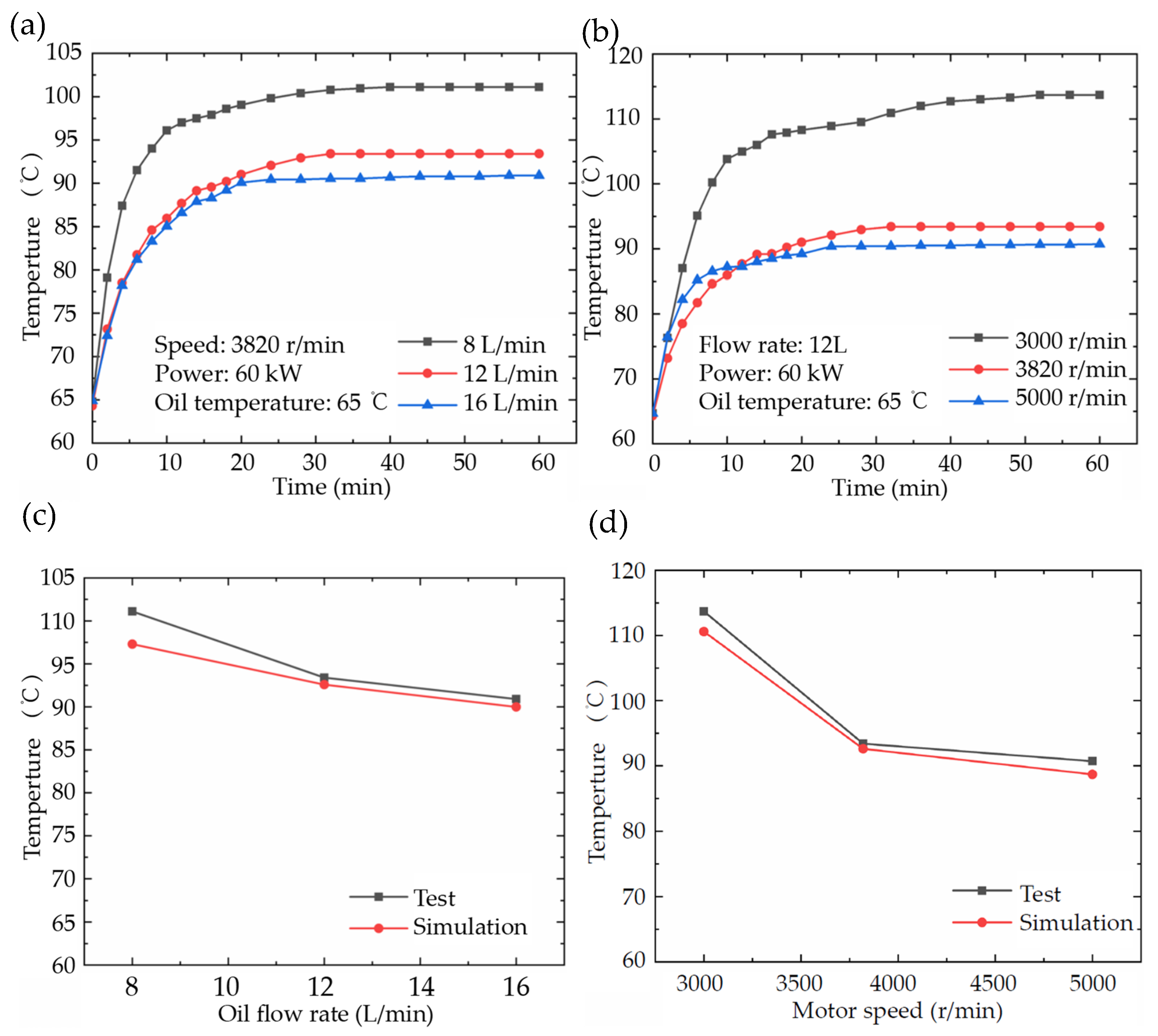

4.3.1. Effect of Flow Rate of Cooling Oil

4.3.2. Effect of Motor Rotational Speed

5. Experimental Analysis

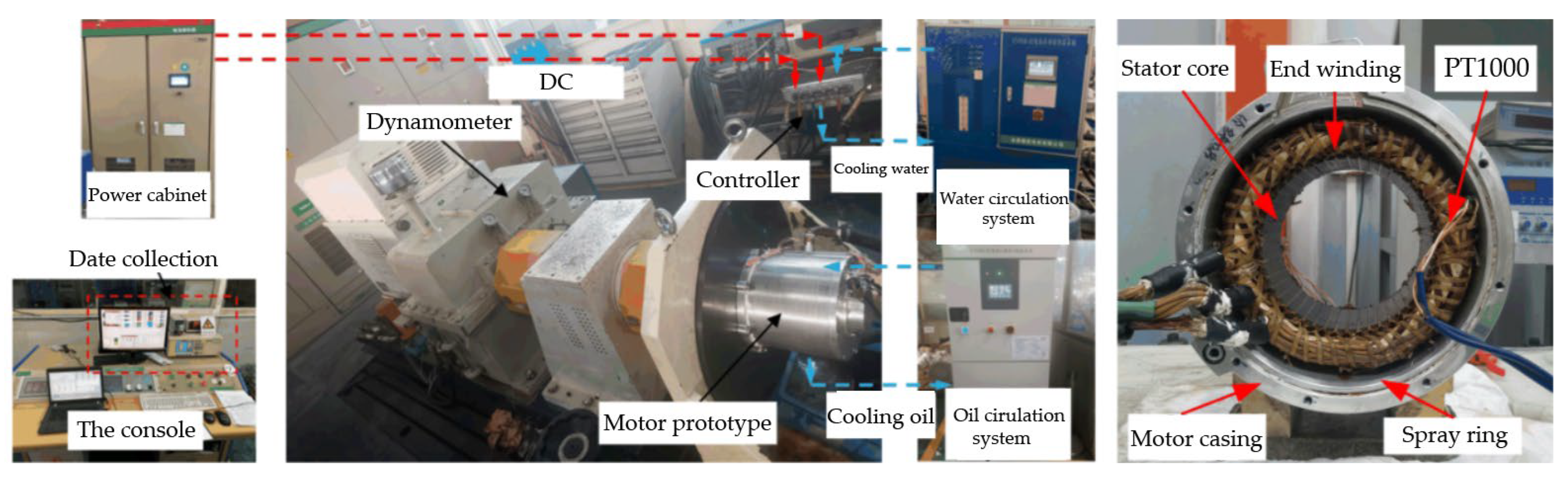

5.1. Experimental Design

5.2. Experimental Results

6. Conclusions

- a.

- The pressure loss of the S-shaped axial returning passage is only half of that of the right-angle axial returning passage and 33% lower than that of the round-corner axial returning passage, while the wall heat-transfer coefficients of all the three passage types are comparable.

- b.

- The optimal configuration of the S-shaped passage includes 16 returns with a width of 18 mm. For the end-spraying passage, a 240° nozzle arrangement is preferred due to its minimal pressure loss.

- c.

- The proposed combined oil-cooling scheme efficiently cools both the stator core and end winding and significantly improves the uniformity of motor temperature. At a cooling oil flow rate of 12 L/min, the maximum temperature of the end winding is 92.6 °C, only 1.5 °C higher than the maximum temperature of the stator core under rated operating conditions. The simulated end-winding temperature shows close agreement with the experimental measurements, with a maximum deviation of only 3.8 °C.

- d.

- Although experimentally validated on a 60 kW prototype, the findings possess wider applicability. The underlying mechanism of the S-shaped passage is rooted in fundamental fluid dynamics, rendering it effective for various casing-cooled motors irrespective of their specific dimensions. Additionally, the hybrid cooling strategy tackles the universal thermal bottleneck of end windings of end windings in high-power-density motors. Therefore, the proposed cooling structure and optimization methodology provide a scalable reference for thermal management of other PMSMs under diverse operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shewalkar, A.G.; Dhoble, A.S.; Thawkar, V.P. Review on cooling techniques and analysis methods of an electric vehicle motor. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 5919–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Le, W.; Lin, K.; Jia, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, A.; Tu, Y. Overview on research and development of thermal design methods of axial flux permanent magnet machines. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 1914–1929. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumislawska, M.; Gyftakis, K.N.; Kavanagh, D.F.; McCulloch, M.D.; Burnham, K.J.; Howey, D.A. The impact of thermal degradation on properties of electrical machine winding insulation material. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 2951–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.L.; Zhang, C.N. Oil-cooling method of the permanent magnet synchronous motor for electric vehicle. Energies 2019, 12, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhu, L.P.; Wang, S.F. Experimental investigation on rotational oscillating heat pipe for in-wheel motor cooling of urban electric vehicle. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 151, 107209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Liu, W.Z.; Stichel, S.; Yang, J.Y. Influence of thermal expansion and wear on the temperatures and stresses in railway disc brakes. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 158, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davin, T.; Pelle, J.; Harmand, S.; Yu, R. Experimental study of oil cooling systems for electric motors. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 75, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, C. Oil cooling method for internal heat sources in the outer rotor hub motor of electric vehicle and thermal characteristics research. Energies 2024, 17, 6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, R.; Künzler, M.; Moullion, M.; Gauterin, F. Comparison of commonly used cooling concepts for electrical machines in automotive applications. Machines 2022, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Nategh, S.; Lassila, V.; Alakula, M. Direct oil cooling of traction motors in hybrid drives. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference, Greenville, SC, USA, 4–8 March 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolini, F.; De Donato, G.; Capponi, F.G.; Caricchi, F. Direct Oil Cooling of End-Windings in Torus-Type Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 2378–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, F.; Fu, J.; Zeng, J.; Fu, X.; Zhai, G.; Zhang, F. Study of the Thermal Performance of Oil-Cooled Electric Motor with Different Oil-Jet Ring Configurations. Energies 2025, 18, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Fan, Y.J.; Cai, W.; Wei, X. Oil circuit structure optimization design and temperature field calculation of oil cooled motor with hairpin winding. Electr. Mach. Control 2023, 27, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, H.Z.; Niu, X.Z.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.G. Design and analysis of cycling oil cooling in driving motors for electric vehicle application. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference, Hangzhou, China, 17–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Cai, W.; Xie, Y.; Shao, B.C. Experiment and simulation study on the cooling performance of oil-cooling PMSM with Hairpin Winding. Machines 2024, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Kim, S.C. Thermal characteristics and effects of oil spray cooling on in-wheel motors in electric vehicles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 152, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Liu, X.C.; Kang, M.; Guo, L.Y.; Li, X.M. Oil Injection Cooling Design for the IPMSM Applied in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 3427–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahfarokhi, P.S.; Kallaste, A.; Podgornovs, A.; Cardoso, A.J.M.; Vaimann, T.; Sarap, M.; Rjabtšikov, V. Experimental investigation of high viscosity on oil spray cooling system with hairpin winding. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 14th International Symposium on Diagnostics for Electrical Machines, Power Electronics and Drives, Berlin, Germany, 18–20 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrústegui, M.; Martinez-Iturralde, M.; Ramos, J.C.; Gonzalez, P.; Astarbe, G.; Elosegui, I. Design criteria for water cooled systems of induction machines. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 114, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Flow field and temperature field of water-cooling-type magnetic coupling. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 32, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzarelli, M.; Nasuti, F.; Onofri, M. Analysis of curved-cooling-channel flow and heat transfer in rocket engines. J. Propuls. Power 2011, 27, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-S.; Chang, S.; Chen, C.-S.; Weng, C.-C.; Jiang, Y.-R.; Shih, S.-H. Numerical flow and experimental heat transfer of S-shaped two-pass square channel with cooling applications to gas turbine blade. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 108, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.; Park, M.; Park, J.; Choi, H.; Lee, K.-D.; Lee, J.-J.; Kim, C.-W. Analysis of cooling characteristics of permanent magnet synchronous motor with different water jacket design using electromagnetic–thermal fluid coupled analysis and design of experiment. Machines 2023, 11, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Mai, C. Study on the effect of spoiler columns on the heat dissipation performance of S-type runner water-cooling plates. Energies 2022, 15, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsoulis, E.; Malamataris, N.A. The free (open) boundary condition with integral constitutive equations. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2012, 117, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| rated DC voltage (V) | 380 | number of stator slots | 48 |

| rated power (kW) | 60 | number of pole pairs | 6 |

| peak power(kW) | 120 | external diameter of stator (mm) | 220 |

| rated rotational speed (r/min) | 3820 | rotor geometry (mm) | 143.2×78 |

| peak rotational speed (r/min) | 12,000 | air-gap length (mm) | 0.8 |

| insulation class | H | rotor core material | Silicon steel |

| returning number of passages | 16 | magnet material (k) | NdFeB (k = 9 W/m·K) |

| nozzle arrangement (°) | 240 | passage shape | S-shape |

| length of stator (mm) | 90 | cross-sectional width of passage (mm) | 18 |

| Rotational Speed | 3000 r/min | 3820 r/min | 5000 r/min | 3000 r/min | 3820 r/min | 5000 r/min | |

| Heat Loss Rate | Loss (W) | Heat Volume Power (W/m3) | |||||

| Name of part | end winds | 3836.2 | 2157.8 | 1498.5 | 2,757,116 | 1,550,832 | 1,070,159 |

| stator | 413.2 | 449 | 582.7 | 252,594 | 274,479 | 356,212 | |

| rotor | 50.8 | 46.2 | 56.7 | 4755 | 4324 | 5307 | |

| Material | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | Density (kg/m3) | Specific Heat Capacity (J/(kg·K)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| aluminum | 151 | 2700 | 963 |

| silicon steel | axial: 4.43 | 7650 | 460 |

| radial: 39 | |||

| copper | axial: 387 | 8520 | 385 |

| radial: 39 | |||

| insulating paper | 0.18 | - | - |

| oil | 0.22 | 870 | 1985 |

| permanent magnet | 9 | 7800 | 420 |

| Rotational Speed (r/min) | Power/kW | Oil Temperature/°C | Oil Flow Rate/L/min | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3820 | 60 | 65 | 8 | Comparison of oil flow |

| 3820 | 60 | 65 | 12 | |

| 3820 | 60 | 65 | 16 | |

| 3000 | 60 | 65 | 12 | Comparison of Rotational speed |

| 3820 | 60 | 65 | 12 | |

| 5000 | 60 | 65 | 12 |

| Cooling Oil Flow (L/min) | Sim Temp (°C) | Exp Temp (°C) | Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 97.3 | 101.1 | 3.76 |

| 12 | 92.6 | 93.4 | 0.86 |

| 16 | 90.8 | 90.9 | 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, X.; Wan, Z.; Duan, J.; Wang, X.; Xie, P.; Xi, R. Design and Analysis of Combining Oil-Cooling Scheme of S-Shaped and End-Spraying Passages for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Energies 2026, 19, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010072

Feng X, Wan Z, Duan J, Wang X, Xie P, Xi R. Design and Analysis of Combining Oil-Cooling Scheme of S-Shaped and End-Spraying Passages for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Energies. 2026; 19(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Xiaoming, Zhenping Wan, Jiachao Duan, Xiaowu Wang, Peili Xie, and Rongsheng Xi. 2026. "Design and Analysis of Combining Oil-Cooling Scheme of S-Shaped and End-Spraying Passages for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor" Energies 19, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010072

APA StyleFeng, X., Wan, Z., Duan, J., Wang, X., Xie, P., & Xi, R. (2026). Design and Analysis of Combining Oil-Cooling Scheme of S-Shaped and End-Spraying Passages for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Energies, 19(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010072