Prediction of DC Breakdown Strength for Polymer Nanocomposite Based on Energy Depth of Trap

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Prediction Model

2.1. Intrinsic DC Breakdown Strength

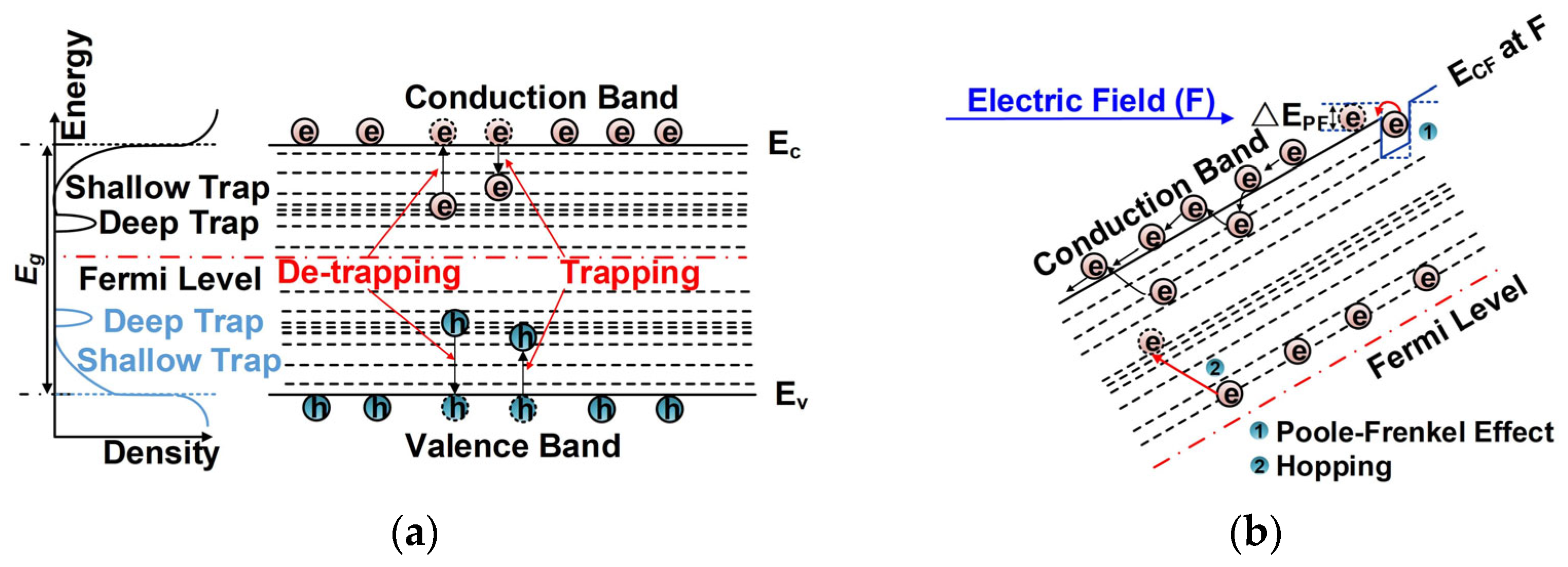

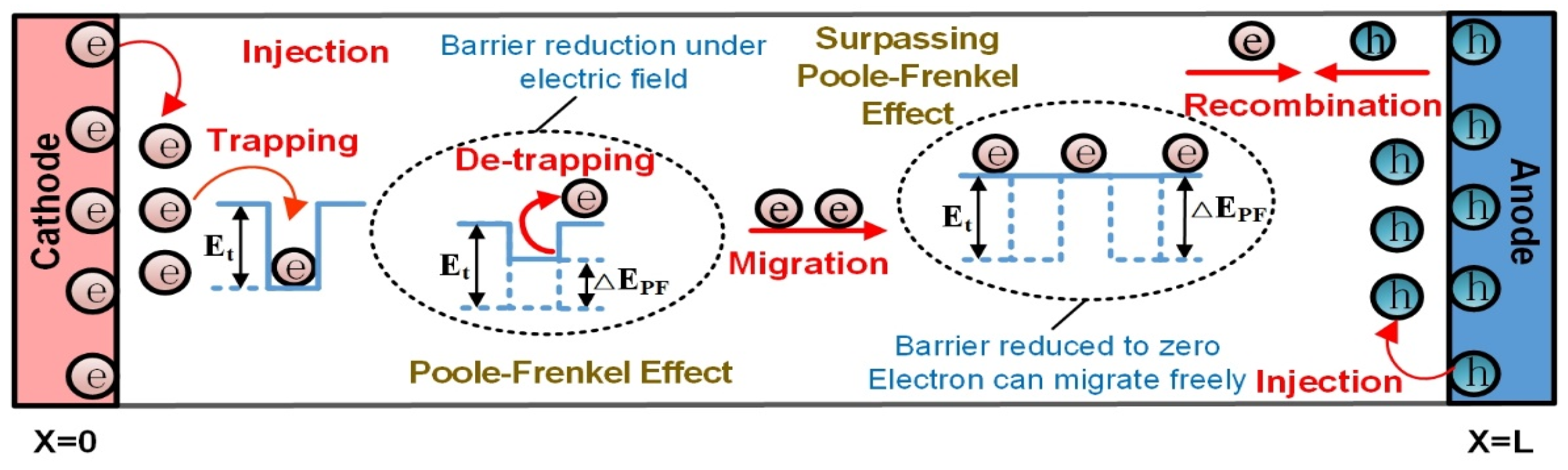

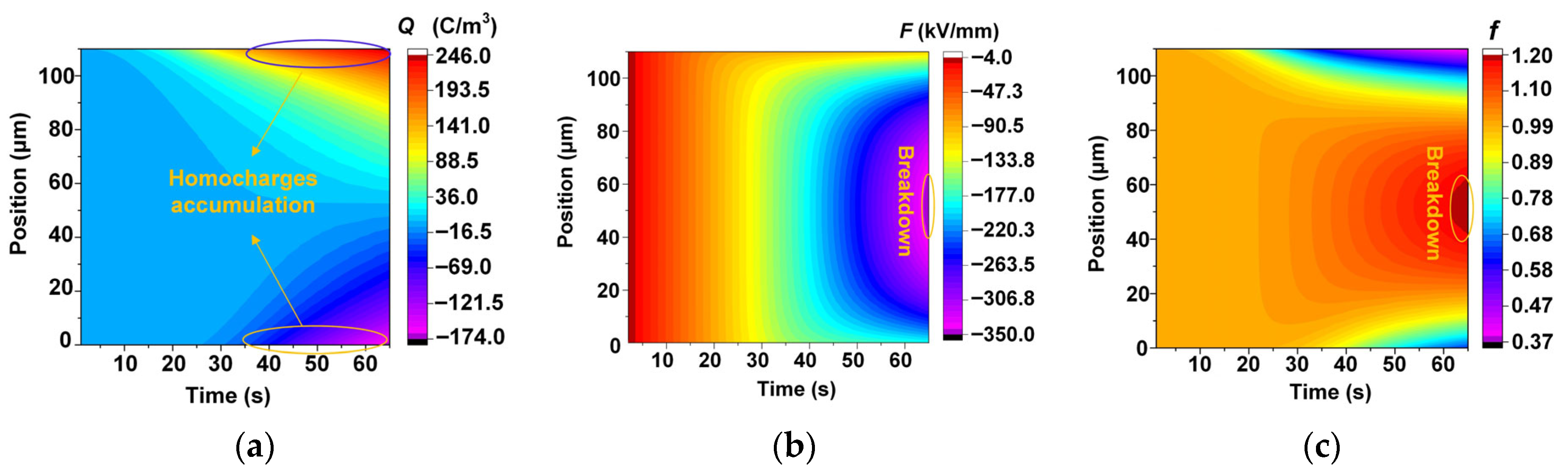

2.2. Prediction Method Through Bipolar Charge Transport (BCT) Model

2.2.1. Charge Injection Mechanism

2.2.2. Self-Consistent Equation System for Charge Transport

- (1)

- Charge continuity equation:

- (2)

- Charge transport equation:

- (3)

- Poisson’s equation:

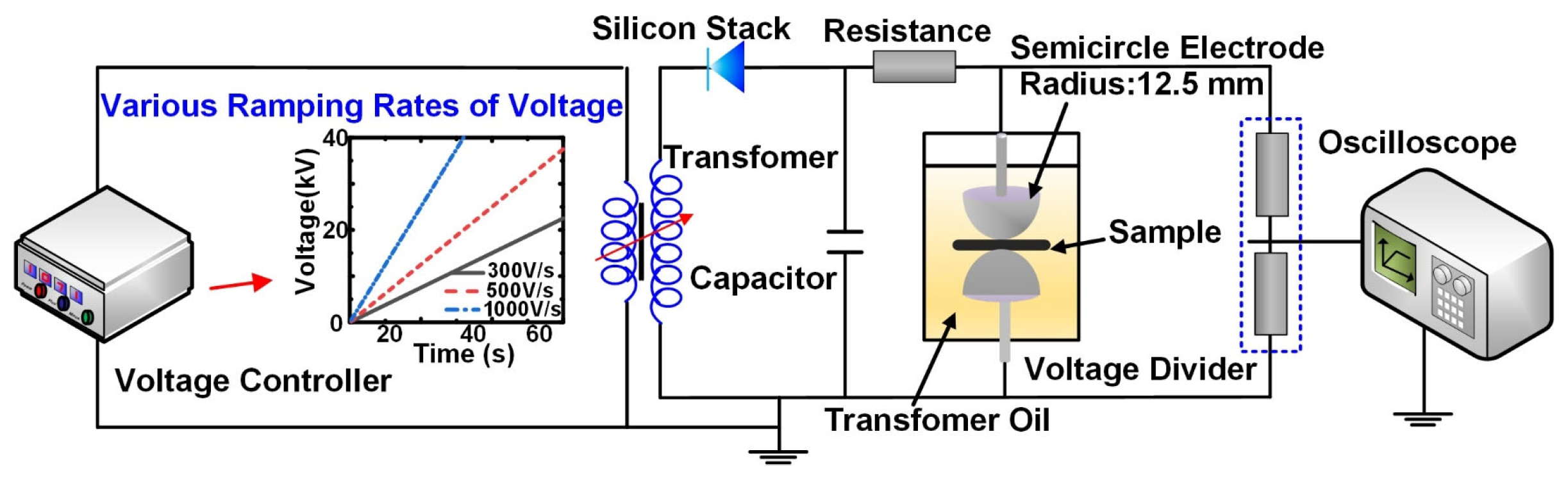

3. Experimental Setup

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Relative Permittivity

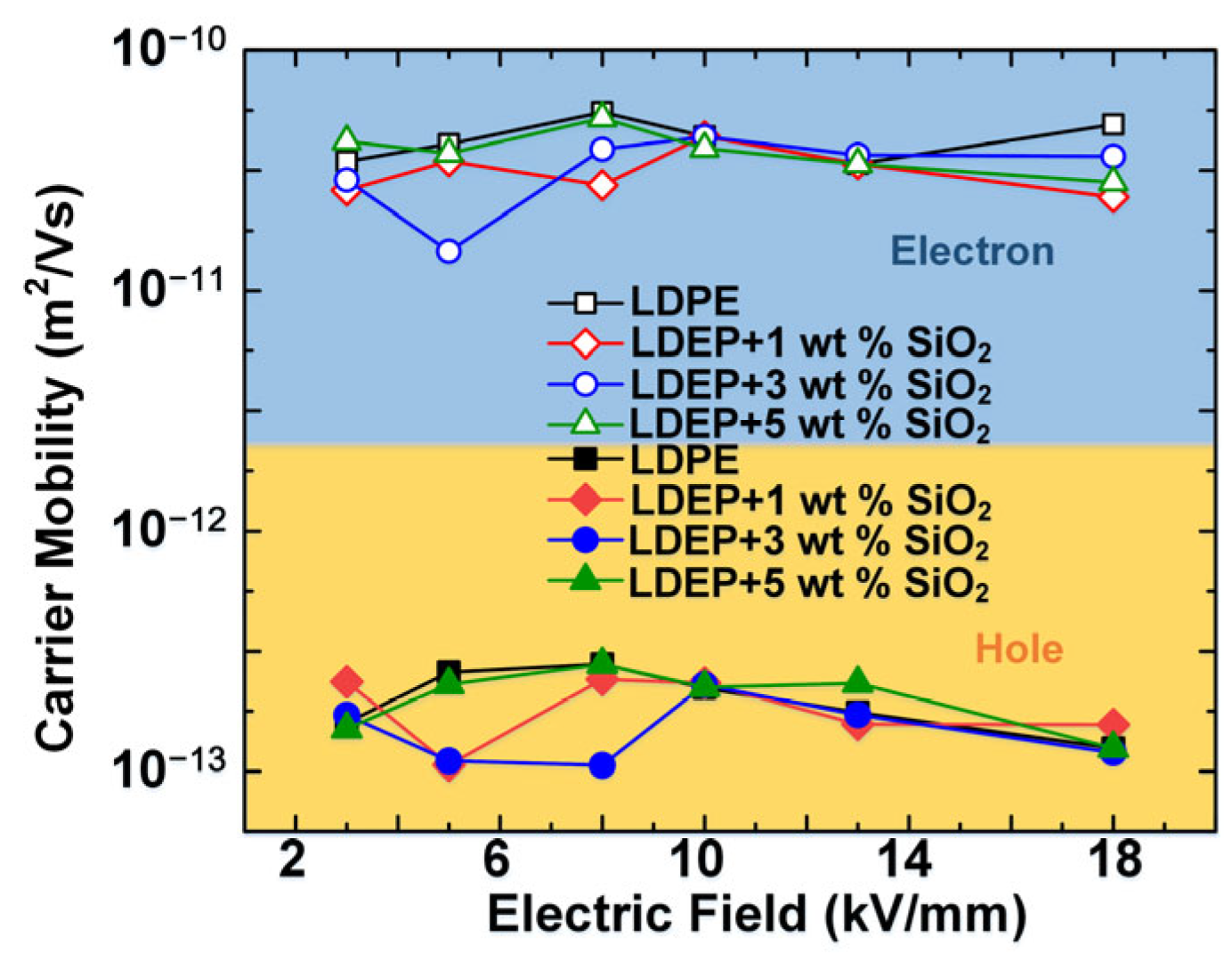

4.2. Carrier Mobility

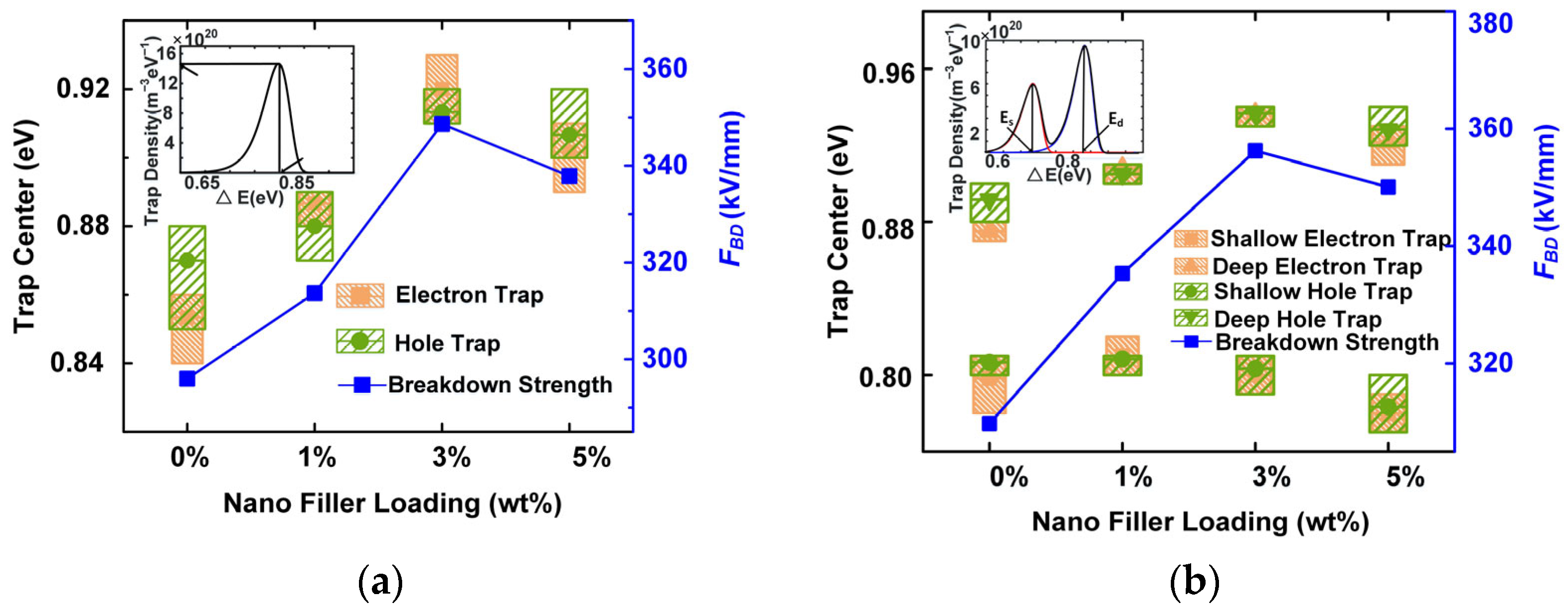

4.3. Trap Distribution

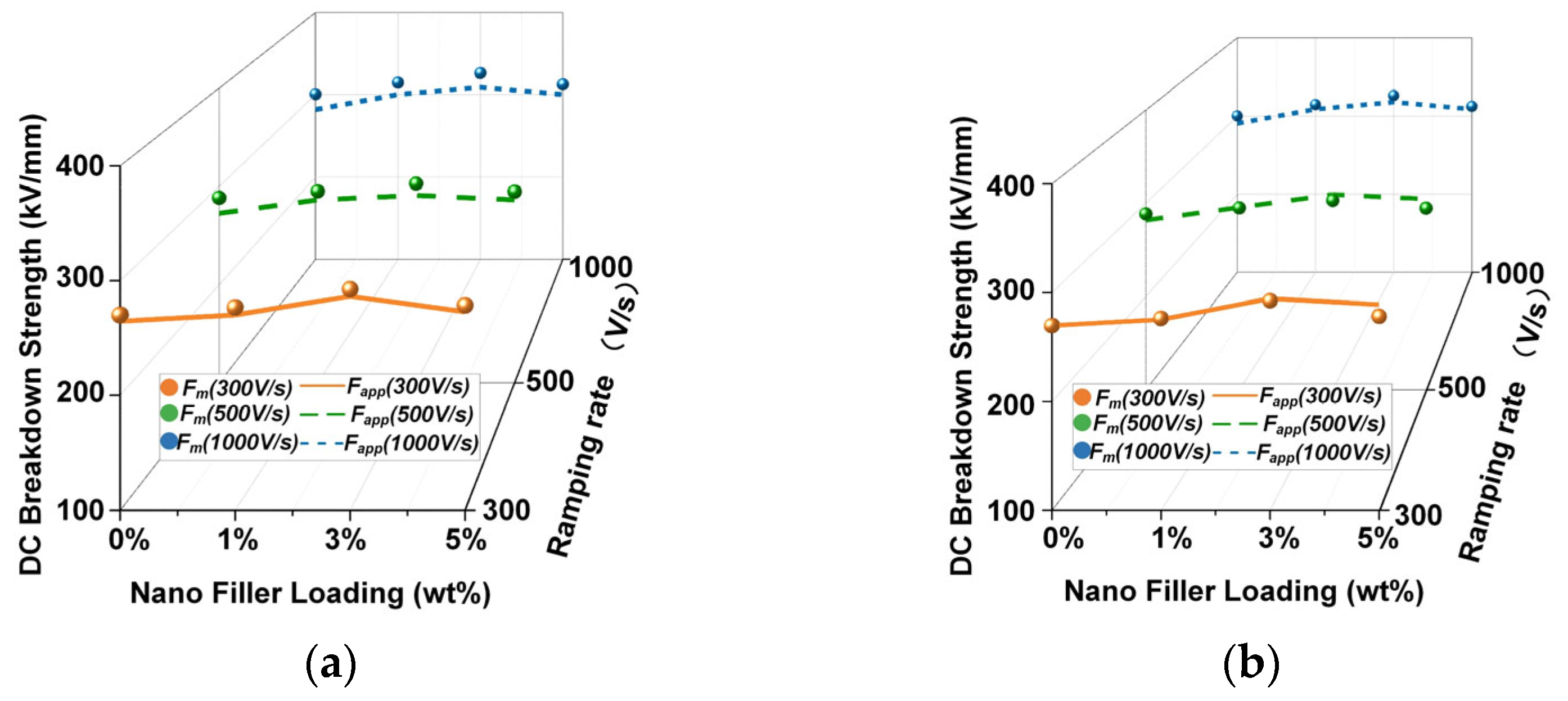

4.4. DC Breakdown Strength

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciuprina, F.; Plesa, I. DC and AC conductivity of LDPE nanocomposites. In Proceedings of the 2011 7TH International Symposium on Advanced Topics in Electrical Engineering (ATEE), Bucharest, Romania, 12–14 May 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, G. The electrical degradation threshold of polyethylene investigated by space charge and conduction current measurements. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2002, 7, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Miao, L.; Zhou, G.; Che, L.; Yin, Y. Space charge observation under periodic stress—Part 2: Signal improvement and corresponding procedure. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2020, 27, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Min, D.; Chen, G. Space charge modulated electrical breakdown. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, K.C. Dielectric Phenomena in Solids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Xu, Z. Charge trapping and detrapping in polymeric materials. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 123707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Min, D.; Wang, W.; Chen, G. Linking traps to dielectric breakdown through charge dynamics for polymer nanocomposites. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2016, 23, 2777–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, G.; Laurent, C.; Teyssedre, G.; Campus, A.; Nilsson, U. From LDPE to XLPE: Investigating the change of electrical properties. Part I. space charge, conduction and lifetime. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2005, 12, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J. On pre-breakdown phenomena in insulators and electronic semi-conductors. Phys. Rev. 1938, 54, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Dissado, L.A.; Okamoto, T. Percolation model for electrical breakdown in insulating polymers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 4454–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Dissado, L.A. Percolation model for electrical breakdown in insulating polymers. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Meeting of the IEEE Lasers and Electro-Optics Society, 2004. LEOS 2004, Rio Grande, PR, USA, 11 November 2004; pp. 514–518. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, C.; Teyssedre, G.; Le Roy, S.; Baudoin, F. Charge dynamics and its energetic features in polymeric materials. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2013, 20, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Min, D.; Wang, W.; Chen, G. Modelling of dielectric breakdown through charge dynamics for polymer nanocomposites. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 23, 3476–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Zhang, C.; Cui, H.; Hai, Y.; Wu, Q.; Min, D. Space charge accumulation and decay in dielectric materials with dual discrete traps. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, S.; Du, B. Trap distribution and dielectric breakdown of isotactic polypropylene/propylene based elastomer with improved flexibility for DC cable insulation. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 58645–58661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Jia, T. Charge transport in low density polyethylene based micro/nano-composite with improved thermal conductivity. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2019, 52, 285302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Du, B. Improvement on partial discharge resistance of epoxy/Al2O3 nanocomposites by irradiation with 7.5 MeV electron beam. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 25121–25129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, F.; Min, D.; Li, S.; Xia, R. The energy distribution of trapped charges in polymers based on isothermal surface potential decay model. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2015, 22, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.-C.; Chen, G.; Liao, R.-J.; Xu, Z. Charge trapping and detrapping in polymeric materials: Trapping parameters. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 043724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Numerical analysis of space charge accumulation and conduction properties in LDPE nanodielectrics. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2015, 22, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Min, D.; Li, S. Understanding the conduction and breakdown properties of polyethylene nanodielectrics: Effect of deep traps. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2016, 23, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D.; Li, S. Simulation on the influence of bipolar charge injection and trapping on surface potential decay of polyethylene. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2014, 21, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D.; Cui, H.; Wang, W.; Wu, Q.; Xing, Z.; Li, S. The coupling effect of interfacial traps and molecular motion on the electrical breakdown in polyethylene nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 184, 107873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nano Loading (wt%) | Value |

|---|---|

| 0% | 2.27 |

| 1% | 2.33 |

| 3% | 2.37 |

| 5% | 2.40 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Effective injection barrier Ein (eV) | |

| Ein(e) (for electrons) | 1–1.5 |

| Ein(h) (for holes) | 1–1.5 |

| Carrier mobility μ0 × 10−13 (m2V−1s−1) | |

| μ0(e) (of electrons) | 0.01–0.02 |

| μ0(h) (of holes) | 1–2 |

| Density of traps NT × 1021 (m−3) | |

| NT(e) (for electrons) | 0.5–2 |

| NT(h) (for holes) | 0.5–2 |

| Energy of traps ET (eV) | |

| ET(e) (for electrons) | 0.8–1.0 |

| ET(h) (for holes) | 0.8–1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qi, X.; Guan, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Guo, C.; Shang, Q.; Gao, Y. Prediction of DC Breakdown Strength for Polymer Nanocomposite Based on Energy Depth of Trap. Energies 2026, 19, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010044

Qi X, Guan J, Xu X, Zhang Z, Zhu C, Guo C, Shang Q, Gao Y. Prediction of DC Breakdown Strength for Polymer Nanocomposite Based on Energy Depth of Trap. Energies. 2026; 19(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Xiaohu, Jian Guan, Xuri Xu, Zhen Zhang, Chuanyun Zhu, Chenyi Guo, Qifeng Shang, and Yu Gao. 2026. "Prediction of DC Breakdown Strength for Polymer Nanocomposite Based on Energy Depth of Trap" Energies 19, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010044

APA StyleQi, X., Guan, J., Xu, X., Zhang, Z., Zhu, C., Guo, C., Shang, Q., & Gao, Y. (2026). Prediction of DC Breakdown Strength for Polymer Nanocomposite Based on Energy Depth of Trap. Energies, 19(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010044