Partitioned Configuration of Energy Storage Systems in Energy-Autonomous Distribution Networks Based on Autonomous Unit Division

Abstract

1. Introduction

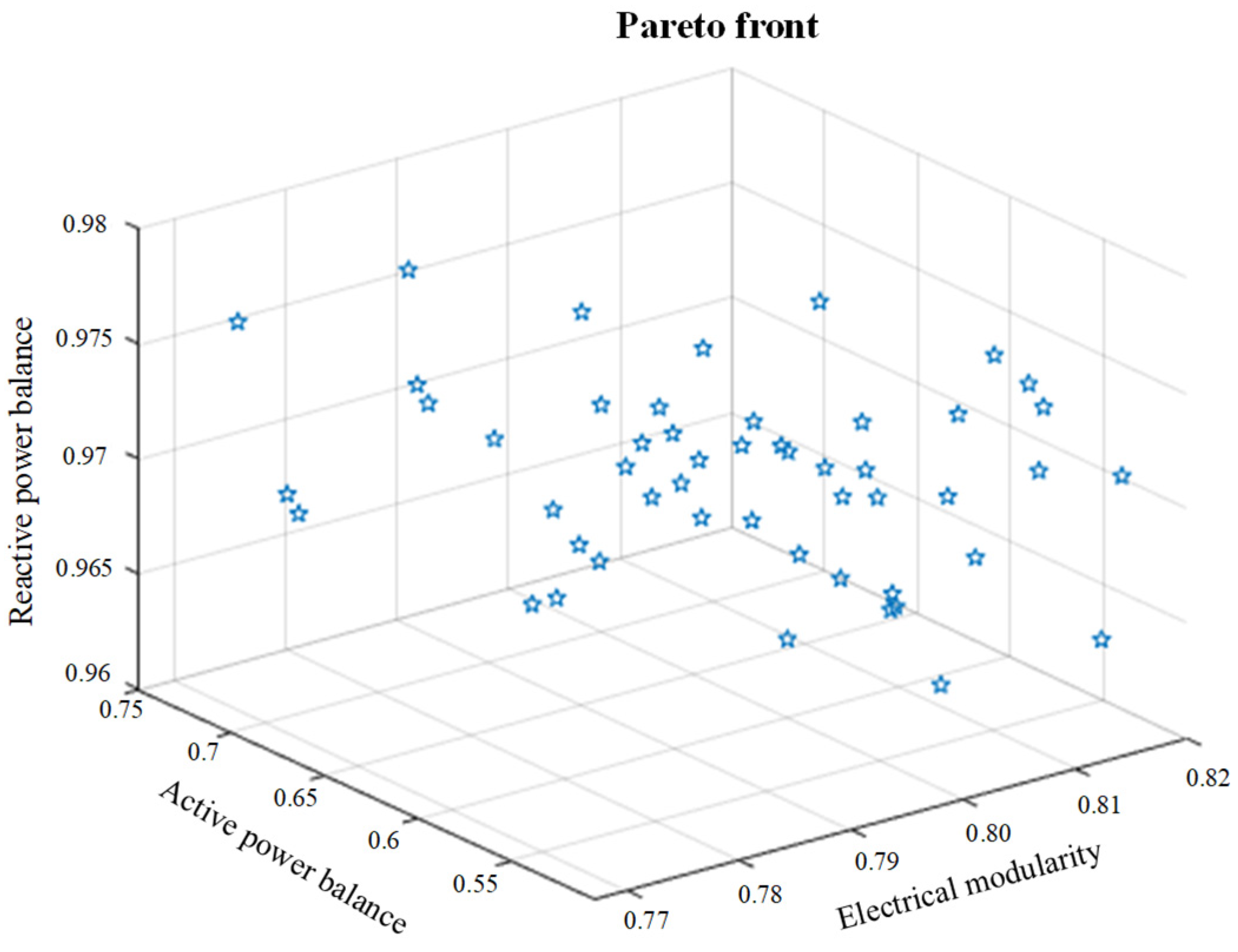

- An indicator-driven autonomous unit partitioning method is developed for energy-autonomous distribution networks. By jointly considering electrical modularity, active power balance, and reactive power balance, the proposed method identifies autonomous units from both topological compactness and energy self-balancing perspectives.

- Based on the obtained autonomous unit structure, a partitioned energy storage system configuration model is formulated. The model explicitly links the autonomous unit partitioning results with ESS siting and sizing decisions, enabling energy storage planning to be coordinated with the internal energy balance characteristics of each unit rather than relying solely on centralized optimization.

- The effectiveness of the proposed coordinated partitioning and ESS configuration method is validated through a case study on a typical multi-substation, multi-feeder distribution network. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed approach can effectively reduce network losses, improve voltage profiles, and enhance local energy autonomy while achieving improved economic performance.

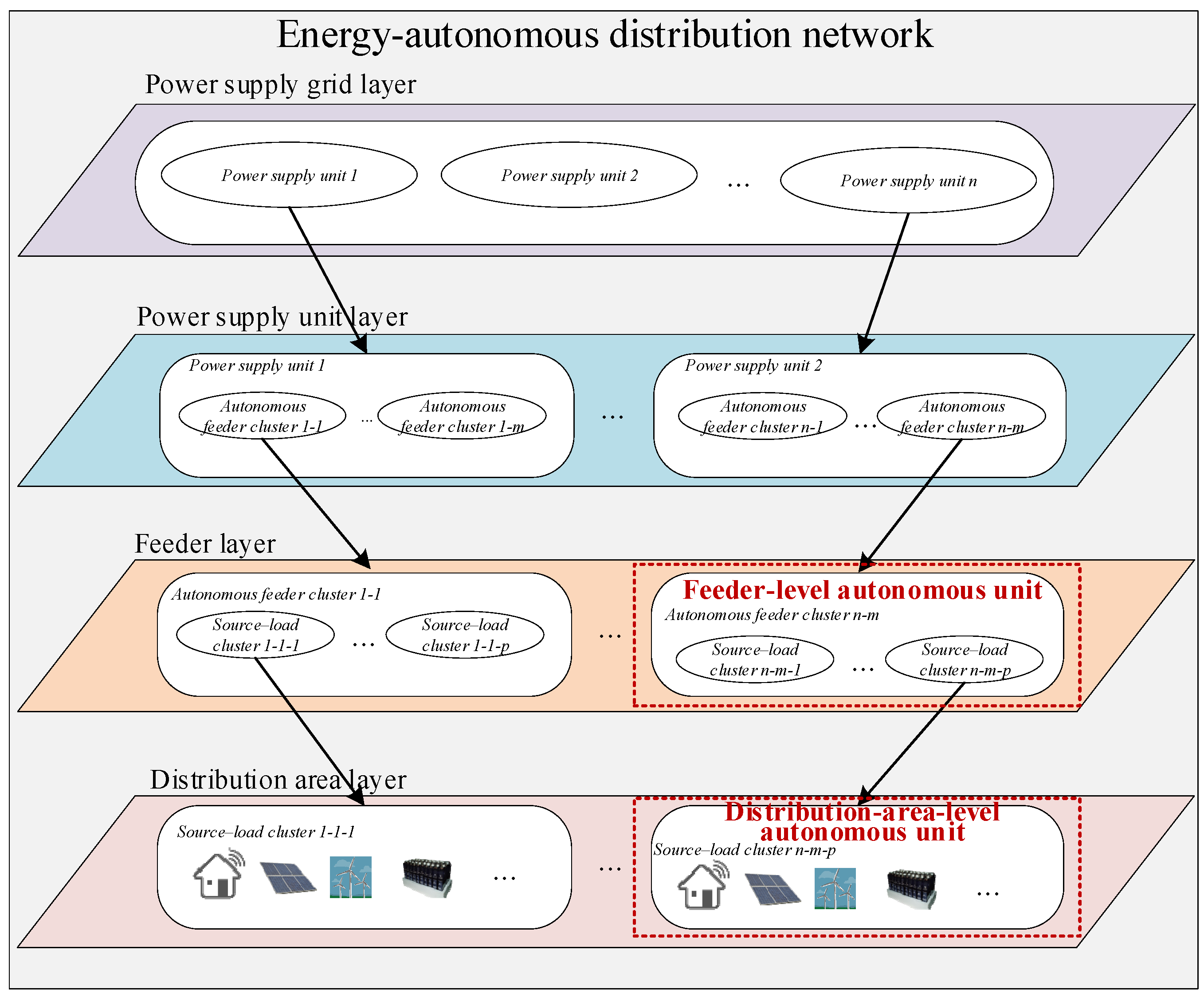

2. Energy-Autonomous Distribution Network

3. Method for Autonomous Unit Division in Energy-Autonomous Distribution Networks

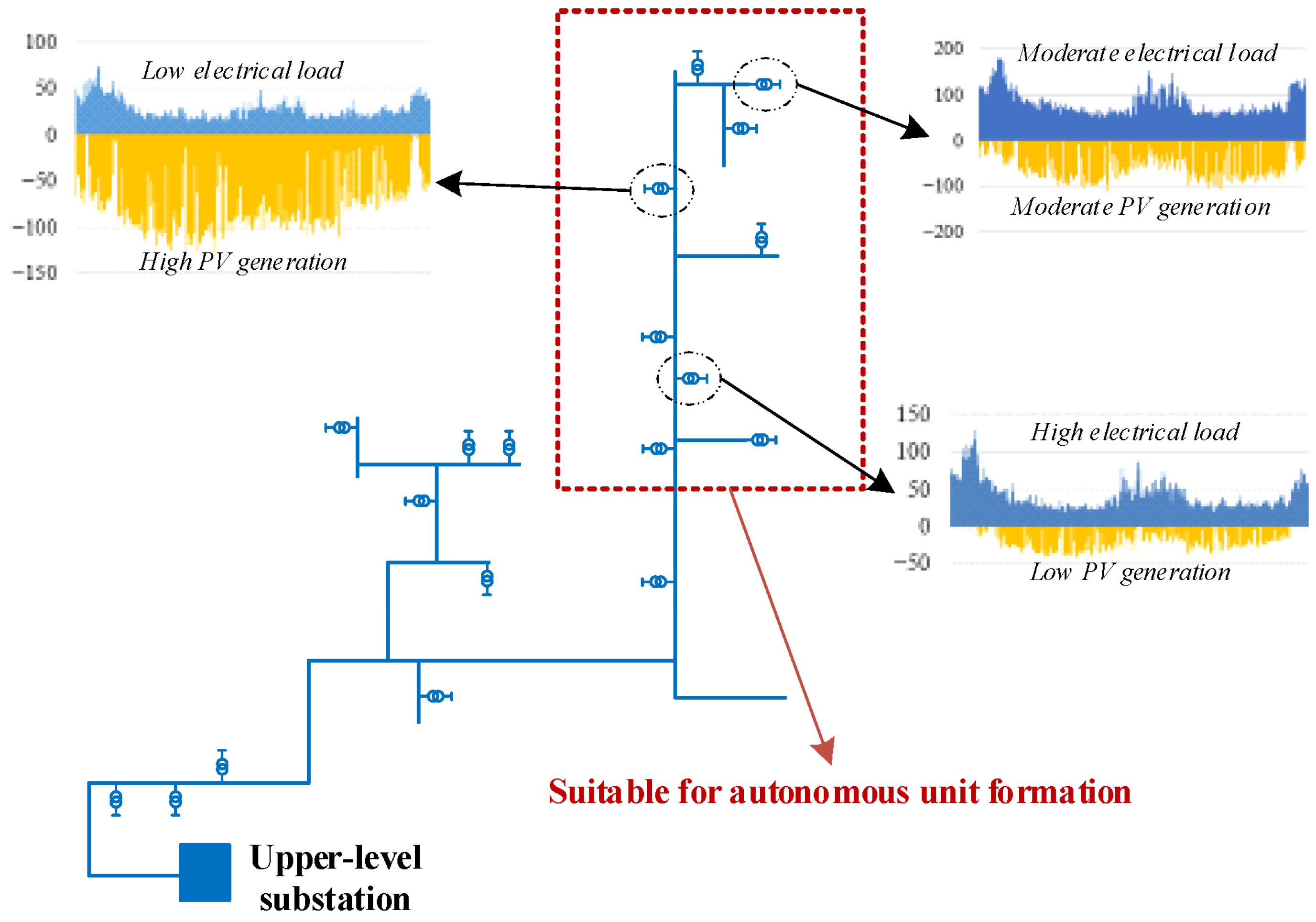

3.1. Division Principle

- Electrical level: The tightness between nodes is evaluated by the electrical coupling strength (ECS), and the compactness within each autonomous unit is assessed using electrical modularity.

- Geographical level: The spatial distance between source–load nodes should not exceed the permissible supply distance, ensuring that geographically adjacent nodes are grouped together.

- Operational level: The division is evaluated using active and reactive power balance indicators. A higher balance degree indicates stronger self-balancing capability and a more reasonable partition of autonomous units.

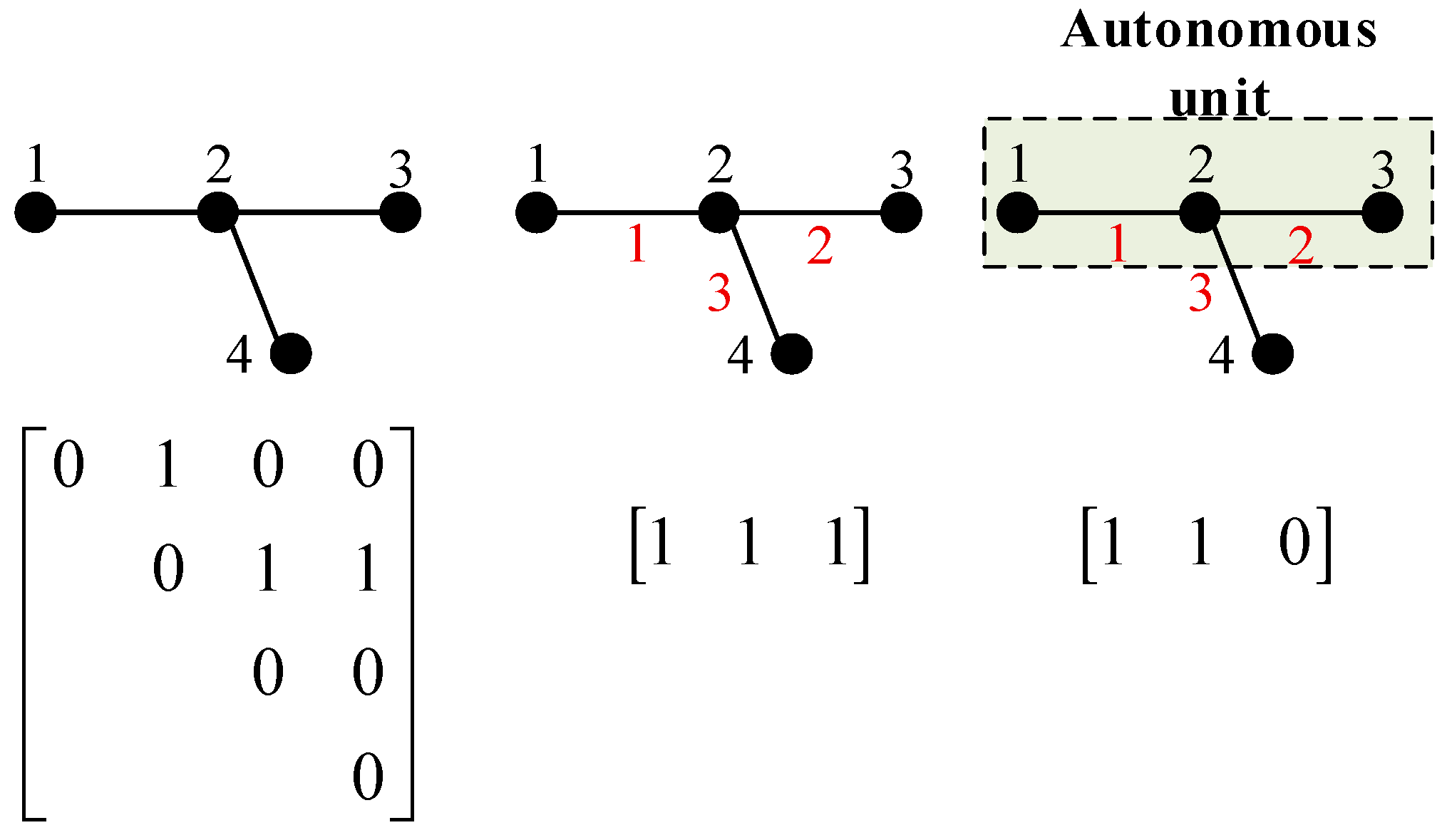

3.2. Division Indicator System

- (1)

- Electrical Modularity Indicator

- (2)

- Reactive power balance indicator

- (3)

- Active power balance indicator

3.3. Division Method

4. Day-Ahead Optimal Scheduling Model

4.1. Objective Function

4.2. Constraints

- (1)

- Energy storage constraints

- (2)

- Power balance constraints

- (3)

- Inter-unit interaction power constraint

- (4)

- Main grid tie-line power constraint

- (5)

- Voltage deviation constraint

- (6)

- Thermal stability constraint

- (7)

- Power flow constraints

4.3. Solution Method

5. Case Study

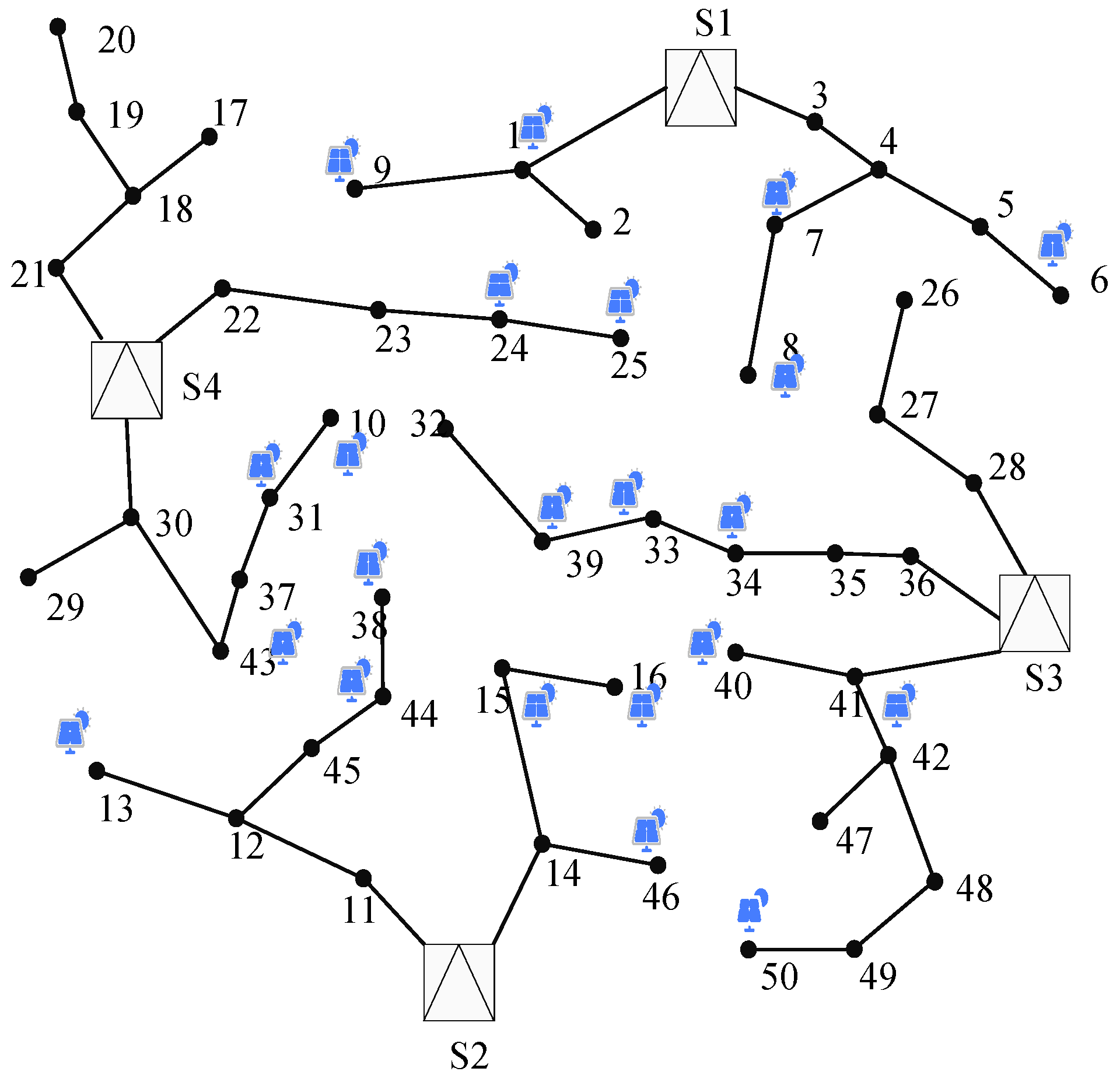

5.1. Case Introduction

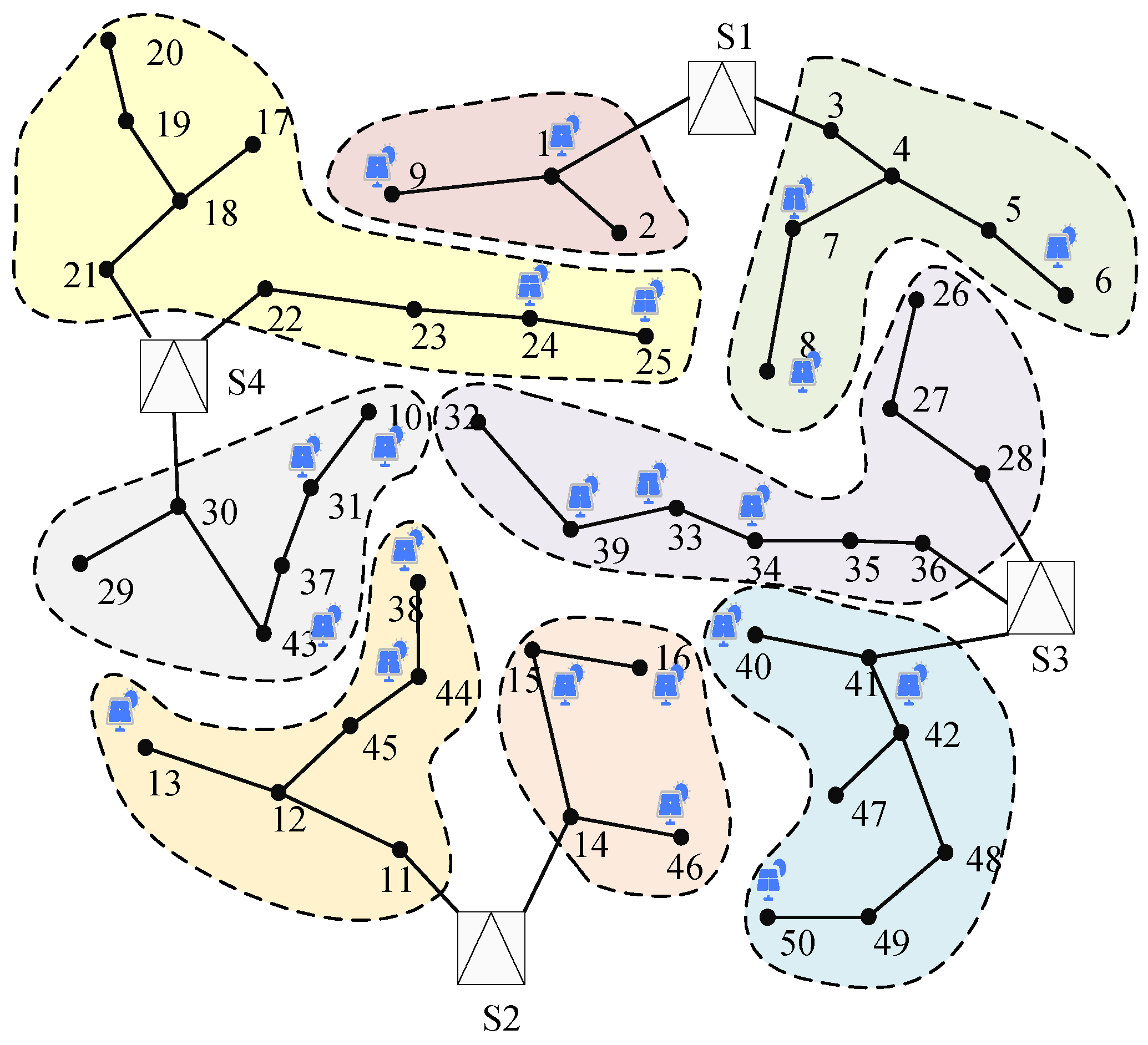

5.2. Analysis of Autonomous Unit Division Results

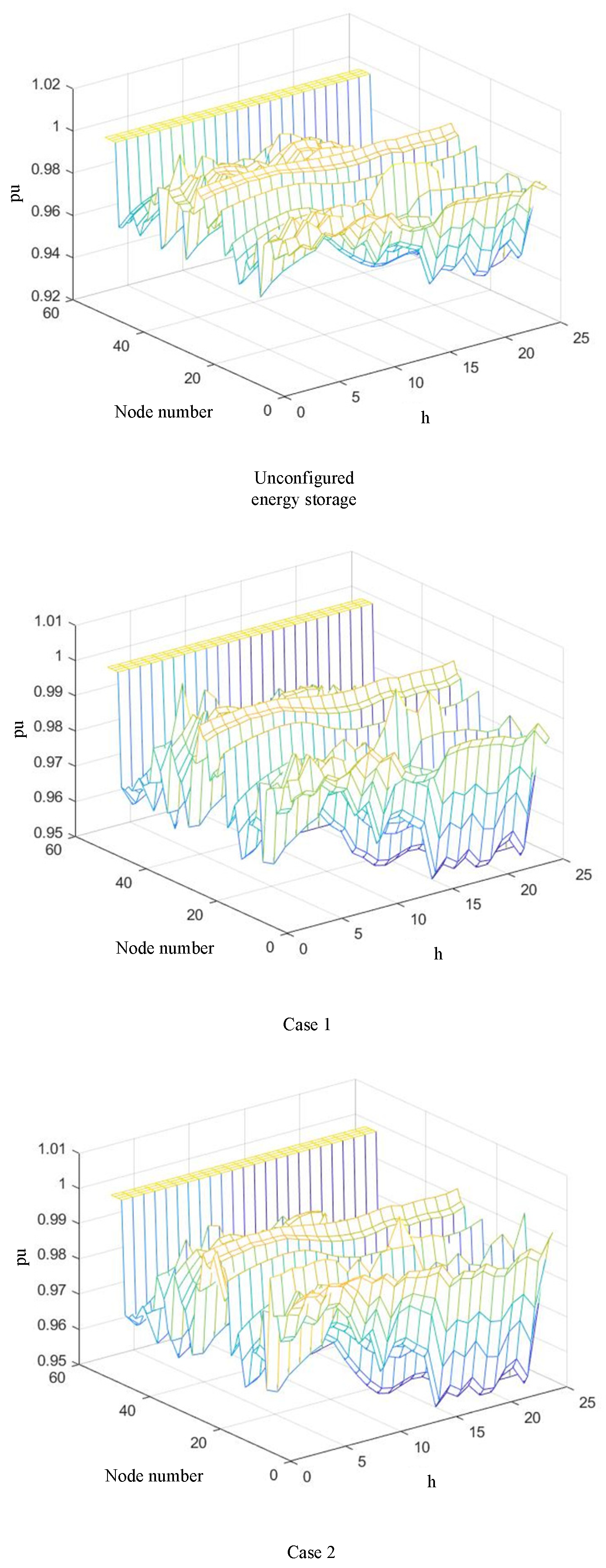

5.3. Analysis of Partitioned Energy Storage Configuration

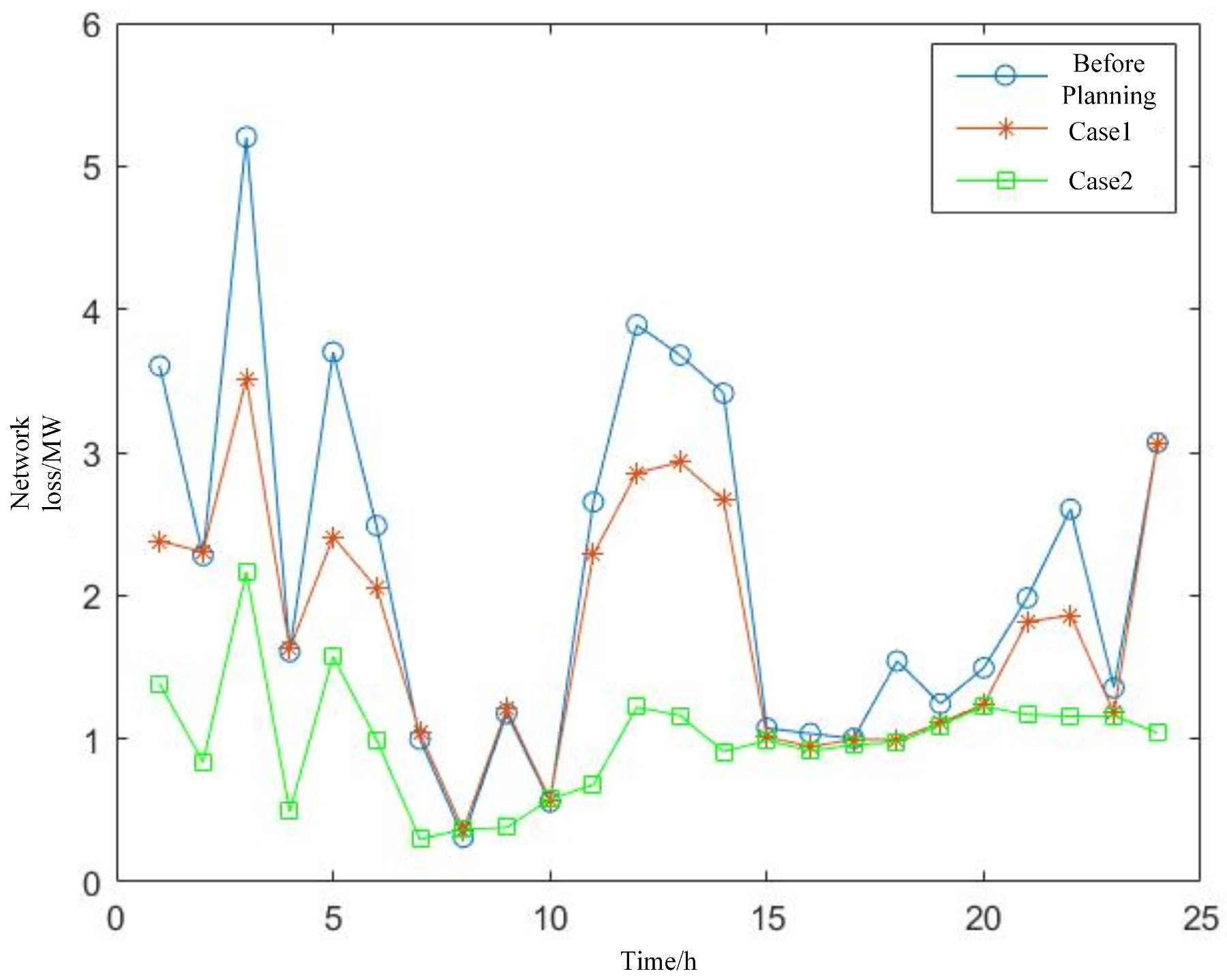

- Case 1: ESSs are configured without considering the division of autonomous units. The candidate installation nodes and the number of accessible ESS units are determined directly.

- Case 2: The proposed method in this paper, in which ESSs are configured within each autonomous unit based on the results of autonomous unit division.

6. Conclusions

- The system architecture and the concept of autonomous units in EADNs are proposed. The hierarchical characteristics and operational mechanisms of EADNs are clarified, and the composition and physical boundaries of autonomous units are defined.

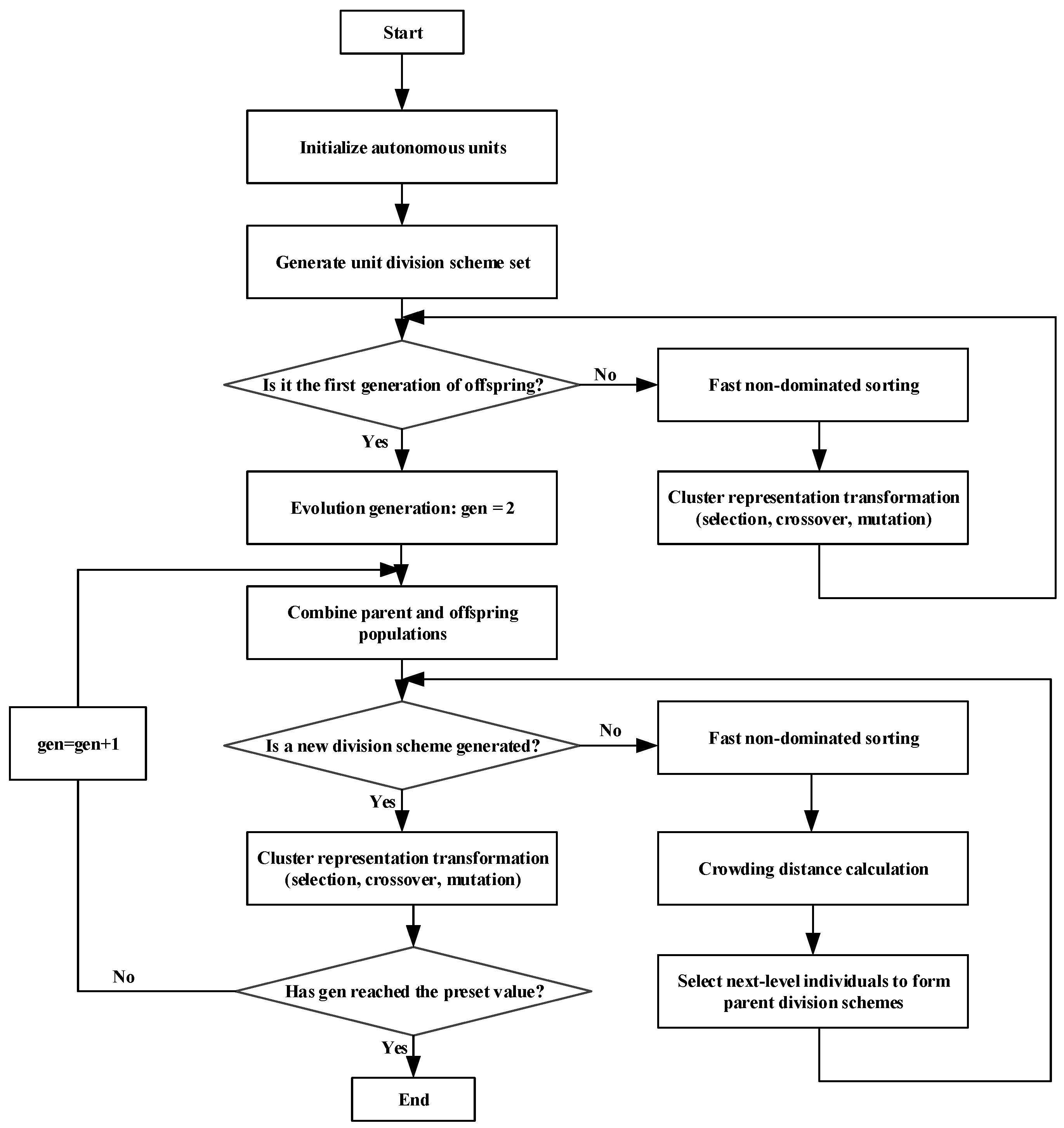

- A framework and division method for autonomous units in EADNs are developed. Following the principle of “tight coupling within units and loose coupling between units,” a comprehensive indicator system for autonomous unit division is established considering electrical modularity, active power balance, and reactive power balance. An improved genetic algorithm is employed for multi-objective optimization to ensure the electrical rationality and autonomy of the partitioning results.

- A partitioned configuration model for energy storage systems considering the autonomous unit structure is proposed. The model aims to minimize the total cost by comprehensively accounting for storage investment and operation costs, main grid power purchase costs, network losses, and PV curtailment losses. Case studies demonstrate that the proposed model effectively improves voltage quality while reducing network losses by 53.82% and 43.99% compared with the pre-storage and traditional centralized storage configurations, respectively. Meanwhile, the total cost is reduced by 20.89% and 14.31%, ensuring optimal economic performance of storage configuration and enhancing the autonomy of EADNs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |||

| EADN | Energy-autonomous distribution network | DERs | Distributed energy resources |

| DG | Distributed generation | ESSs | Energy storage systems |

| ECS | Electrical coupling strength | PV | Photovoltaic |

| GA | Genetic algorithm | SBX | Simulated binary crossover |

| Parameters | |||

| The electrical modularity | The network loss cost | ||

| The adjacency matrix | The unit cost of network loss | ||

| m | The total weight of all edges in the network | The total number of branches | |

| The electrical coupling strength of node i | The current magnitude on branch i at time t | ||

| The electrical coupling strength between nodes i and j | The resistance of branch i | ||

| The per-unit values of the equivalent admittance of line ij | The PV curtailment cost | ||

| The per-unit values of transfer capacity of line ij | The unit cost of curtailed PV energy | ||

| The average values of equivalent admittance | The set of distributed PV units | ||

| The average values of transfer capacity | The curtailed PV power of unit i at time t | ||

| The equivalent impedance of line ij | The total stored energy of the i-th ESS at time t | ||

| The element in the i-th row and j-th column of the impedance matrix | The charge efficiencies | ||

| The power transfer capacity between nodes i and j | The discharge efficiencies | ||

| The maximum transfer capacity of line ij | The charge powers of the i-th ESS at time t | ||

| The power transfer distribution factor of line ij | The discharge powers of the i-th ESS at time t | ||

| The reactive balance of unit i | The rated capacity of the i-th ESS | ||

| The reactive power balance index | The rated charge/discharge power | ||

| c | The number of autonomous meshes | The lower limits of the state of charge | |

| The maximum reactive power supply within the unit | The upper limits of the state of charge | ||

| The total reactive demand within the unit | The power on the tie line between the EADN and the main grid at time t | ||

| The active power balance degree of unit i | The total PV generation of autonomous unit i at time t | ||

| The net power characteristics of unit i under typical time-varying scenarios | The total load | ||

| T | The time horizon of the scenario | The network loss of unit i at time t | |

| The active power balance index | The interaction power between autonomous unit i and its neighboring units | ||

| The comprehensive indicator of autonomous unit division | The upper limits of allowable power transfer on tie line l between autonomous units | ||

| The weighting coefficient of electrical modularity indicator | The lower limits of allowable power transfer on tie line l between autonomous units | ||

| The weighting coefficient of reactive power balance index | The power flow on the tie line between the main grid and the distribution network at time t | ||

| The weighting coefficient of active power balance index | The operating voltage of node i at time t | ||

| The investment cost of ESSs | The rated voltage | ||

| The discount rate. | The allowable voltage deviation range | ||

| The unit investment cost per capacity of ESS | The current of line ij at time t | ||

| The rated capacity of the i-th ESS | The maximum allowable current capacity of line ij | ||

| The unit investment cost per power rating | The set of sending-end nodes for branches terminating at node j | ||

| The rated power of the i-th ESS | The set of receiving-end nodes for branches originating from node j | ||

| The O&M cost of ESSs | The active power flows from node i to node j at time t | ||

| The unit O&M cost per charge/discharge energy | The reactive power flows from node i to node j at time t | ||

| The charge/discharge power of ESS at time t | The net injected active powers at node j at time t | ||

| The power purchase cost from the main grid | The net injected reactive powers at node j at time t | ||

| The number of tie lines connected to the main grid | The voltage magnitude at node j at time t | ||

| The real-time electricity price at time t | The resistance of branch ij | ||

| The power flow on the tie line at time t | The reactance of branch ij | ||

References

- Wang, S.; Luo, F.; Fo, J.; Lv, Y.; Wang, C. Two-Stage Spatiotemporal Decoupling Configuration of SOP and Multi-Level Electric-Hydrogen Hybrid Energy Storage Based on Feature Extraction for Distribution Networks with Ultra-High DG Penetration. Appl. Energy 2025, 398, 126438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Wang, S.; Lv, Y.; Mu, R.; Fo, J.; Zhang, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, C. Domain Knowledge-Enhanced Graph Reinforcement Learning Method for Volt/Var Control in Distribution Networks. Appl. Energy 2025, 398, 126409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, Q.; Tan, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shao, X.; Zou, Y. A Comprehensive Review of Energy Internet: Basic Concept, Operation and Planning Methods, and Research Prospects. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2018, 6, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, H.; Hemmati, R. Maximizing DISCO Profit in Active Distribution Networks by Optimal Planning of Energy Storage Systems and Distributed Generators. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Gao, N.; Wu, F. A Grid as Smart as the Internet. Engineering 2020, 6, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmaee Moghaddam, M.H.; Leon-Garcia, A. A Fog-Based Internet of Energy Architecture for Transactive Energy Management Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ji, H.; Li, P.; Yu, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Bai, L.; Yan, J.; et al. Multi-Resource Dynamic Coordinated Planning of Flexible Distribution Network. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, Q.; Wang, J. Profit-Oriented BESS Siting and Sizing in Deregulated Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Fu, L.; Liao, M.; Xu, X. A Data-Driven Chance-Constrained BESS Planning in Distribution Networks by a Decoupling Solution Method. J. Energy Storage 2024, 80, 11015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Chen, J.; Qu, Y. Optimal Allocation Strategy of SOP in Flexible Interconnected Distribution Network Oriented High Proportion Renewable Energy Distribution Generation. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 6048–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Xue, F.; Lu, S. Power Grid Partitioning Based on Functional Community Structure. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 152624–152634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskouei, M.Z.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Erdinc, O.; Erdinc, F.G. Optimal Allocation of Renewable Sources and Energy Storage Systems in Partitioned Power Networks to Create Supply-Sufficient Areas. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Du, X.; Pan, J. Network Partition and Voltage Coordination Control for Distribution Networks with High Penetration of Distributed PV Units. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 3396–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, C.L.T.; Martins, V.F. Multistage Expansion Planning for Active Distribution Networks under Demand and Distributed Generation Uncertainties. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2012, 36, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Yan, H.; Zou, H.; Luo, B. Integrated Planning of Distribution Systems with Distributed Generation and Demand Side Response. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osama, R.A.; Zobaa, A.F.; Abdelaziz, A.Y. A Planning Framework for Optimal Partitioning of Distribution Networks into Microgrids. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmitwally, A.; Elsaid, M.; Elgamal, M.; Chen, Z. A Fuzzy-Multiagent Self-Healing Scheme for a Distribution System with Distributed Generations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2015, 30, 2612–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhang, H.; Ji, K.; Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Tao, B.; Li, Z.; Mi, Y. Two-Stage Robust Planning Method for Distribution Network Energy Storage Based on Load Forecasting. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1327857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Geng, X.; Bie, Z.; Xie, L. Two-Stage Robust Energy Storage Planning with Probabilistic Guarantees: A Data-Driven Approach. Appl. Energy 2022, 313, 118623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N. Nodal Frequency-Constrained Energy Storage Planning via Hybrid Data-Model Driven Methods. iEnergy 2025, 4, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Su, H.; Tian, J.; Hu, X.; Shen, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, F.; Ma, Y. Independent Energy Storage Planning Model Considering Comprehensive Benefits Enhancement. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 015210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, K.; Maloney, P.R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Holzer, J.T.; Anderson, O.; Ke, X.; Westman, J.; Burleyson, C.D.; Datta, S.; Twitchell, J.B.; et al. Energy Storage Planning for Enhanced Resilience of Power Systems against Wildfires and Heatwaves. J. Energy Storage 2025, 119, 116074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Jiang, T.; Li, F.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Distributed Energy Storage Planning in Soft Open Point Based Active Distribution Networks Incorporating Network Reconfiguration and DG Reactive Power Capability. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 1082–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhou, S. A Method of Energy Storage Capacity Planning to Achieve the Target Consumption of Renewable Energy. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yao, J. Multi-Objective Optimization of Integrated Process Planning and Scheduling Considering Energy Savings. Energies 2020, 13, 6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Gao, C.; Xu, Z.; Ren, S.; Wu, D. Multi-Objective Optimization for the Low-Carbon Operation of Integrated Energy Systems Based on an Improved Genetic Algorithm. Energies 2025, 18, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukis, N.; Georgilakis, P. A Chance-Constrained Multistage Planning Method for Active Distribution Networks. Energies 2019, 12, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, V.; Ranito, J.V.; Proenca, L.M. Genetic Algorithms in Optimal Multistage Distribution Network Planning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1994, 9, 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ji, J.; Chen, S.; Ji, H.; Xu, J.; Song, G.; Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, C. Multi-Stage Expansion Planning of Energy Storage Integrated Soft Open Points Considering Tie-Line Reconstruction. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2022, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, F.; Wang, C.; Lyu, Y.; Mu, R.; Fo, J.; Ge, L. Collaborative Configuration Optimization of Soft Open Points and Hydrogen-Based Distributed Multi-Energy Stations Considering Spatiotemporal Coordination and Complementarity. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 2086–2097. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Comprehensive Operating Index |

|---|---|

| Investment cost per unit capacity (CNY/kWh) | 1270 |

| Investment cost per unit power (CNY/kW) | 2000 |

| O&M cost per unit energy (CNY/kWh) | 0.08 |

| Service life (years) | 20 |

| Charge/discharge efficiency | 90% |

| Autonomous Unit | Node Numbers | Electrical Modularity | Active Power Balance | Reactive Power Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–2, 9 | 0.8156 | 0.5825 | 0.9681 |

| 2 | 3–8 | 0.6114 | 0.9696 | |

| 3 | 14–16, 46 | 0.5530 | 0.9632 | |

| 4 | 17–25 | 0.7456 | 0.9786 | |

| 5 | 10, 29–31, 37, 43 | 0.6879 | 0.9713 | |

| 6 | 26–28, 32–36, 39 | 0.7062 | 0.9767 | |

| 7 | 11–13, 38, 44–45 | 0.6348 | 0.9751 | |

| 8 | 40–42, 47–50 | 0.6957 | 0.9755 |

| Node | Rated Capacity (MWh) |

|---|---|

| 6 | 1.82 |

| 9 | 3.45 |

| 10 | 3.98 |

| 16 | 2.11 |

| 25 | 3.18 |

| 38 | 5.67 |

| 39 | 7.57 |

| 50 | 4.39 |

| Total capacity | 32.17 |

| Autonomous Unit | Node | Rated Capacity (MWh) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0.28 |

| 2 | 6 | 1.94 |

| 3 | 16 | 2.03 |

| 4 | 24 | 7.58 |

| 5 | 10 | 3.98 |

| 6 | 39 | 7.37 |

| 7 | 44 | 10.79 |

| 8 | 50 | 4.33 |

| Total capacity | \ | 38.3 |

| Cost Item | Before Configuring ESS | Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESS investment cost (104 CNY) | \ | 554.18 | 634.36 |

| O&M cost (104 CNY) | \ | 149.21 | 136.84 |

| Network loss cost (104 CNY) | 190.64 | 155.74 | 84.58 |

| Power purchase cost (104 CNY) | 7058.54 | 6862.46 | 5988.71 |

| PV curtailment cost (104 CNY) | 2068.13 | 879.85 | 526.15 |

| Total cost (104 CNY) | 9317.31 | 8601.44 | 7370.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Duan, M.; Wang, D.; Qi, S.; Wang, H.; Li, R.; Pu, Q.; Wang, X.; Lyu, G.; Luo, F.; Mu, R. Partitioned Configuration of Energy Storage Systems in Energy-Autonomous Distribution Networks Based on Autonomous Unit Division. Energies 2026, 19, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010203

Duan M, Wang D, Qi S, Wang H, Li R, Pu Q, Wang X, Lyu G, Luo F, Mu R. Partitioned Configuration of Energy Storage Systems in Energy-Autonomous Distribution Networks Based on Autonomous Unit Division. Energies. 2026; 19(1):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010203

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Minghui, Dacheng Wang, Shengjing Qi, Haichao Wang, Ruohan Li, Qu Pu, Xiaohan Wang, Gaozhong Lyu, Fengzhang Luo, and Ranfeng Mu. 2026. "Partitioned Configuration of Energy Storage Systems in Energy-Autonomous Distribution Networks Based on Autonomous Unit Division" Energies 19, no. 1: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010203

APA StyleDuan, M., Wang, D., Qi, S., Wang, H., Li, R., Pu, Q., Wang, X., Lyu, G., Luo, F., & Mu, R. (2026). Partitioned Configuration of Energy Storage Systems in Energy-Autonomous Distribution Networks Based on Autonomous Unit Division. Energies, 19(1), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010203