1. Introduction

High penetration of inverter-based renewable energy sources (RESs), such as solar photovoltaic-based generation, is reshaping both transmission and distribution networks. The stochastic nature of RES output introduces bidirectional power flows, tighter reactive power margins, and increased operational uncertainty, all of which amplify the risk of voltage instability and potential voltage collapse. Voltage collapse remains one of the most severe dynamic phenomena in power systems because it can trigger cascading outages and large-scale blackouts if not detected in time [

1,

2]. Consequently, the development of accurate and computationally efficient tools for online voltage stability assessment is critical for secure and economical system operation.

A variety of voltage stability indices (VSIs) have been proposed to provide rapid indicators of proximity to collapse. Early work focused on global system indices derived from power-flow Jacobian properties, such as the

L-index [

3] and related sensitivity measures [

4]. These formulations are theoretically rigorous because they connect collapse to singularity conditions of the network equations and can, in principle, characterize a system-wide margin. In practice, however, these formulations require complete models, repeated solutions of nonlinear power-flow equations, and careful numerical conditioning, which increases latency and complicates deployment in large systems subject to frequent set-point changes. To achieve faster screening, researchers have developed line-based voltage stability indices that evaluate individual branches using local measurements. Classic examples include the Fast Voltage Stability Index (

FVSI) [

5], Line Stability Index (

LSI) [

6], and Line Voltage Stability Index (

LVSI) [

7]. Their algebraic simplicity, reliance on readily available quantities, and straightforward interpretability make them attractive for contingency ranking, weak-bus identification, and online monitoring across both transmission and distribution networks.

Recent surveys have summarized the landscape of VSIs across line, bus, and system levels, highlighting trade-offs between computational efficiency and sensitivity in RES-rich operating conditions [

1,

8,

9]. More recent contributions have further refined line-based voltage stability indices by improving monotonicity near collapse boundaries and robustness under renewable-integrated operating scenarios [

10,

11]. Building on these appraisals, newer contributions have addressed specific limitations of classical line-based voltage stability indices. Topology- and angle-aware formulations preserve active–reactive coupling and explicitly include the voltage-angle difference between the sending and receiving ends, which improves responsiveness when flows reverse or when long electrical distances amplify angle effects [

12]. In parallel, probabilistic static assessment methods represent the correlation between RES output and load, translating deterministic margins into risk-aware indicators that better reflect feeder-level variability and uncertainty [

13,

14]. Measurement-based approaches using phasor measurement units (PMUs) have also been explored to increase temporal resolution and reduce reliance on iterative solvers. Comparative analyses indicate that synchronized phasor-driven indices can sharpen detection while still depending on accurate modeling of angles and line impedance for robustness [

15]. Beyond index development, recent studies have emphasized that enhanced voltage stability awareness is instrumental in achieving smooth and uninterrupted operation under high penetration of renewable energy sources, particularly in inverter-dominated and microgrid environments [

16].

Meanwhile, research on improving VSI is also underway. For instance, modern line-based formulations partially retain line resistance and couple active–reactive power effects to enhance collapse proximity tracking, as demonstrated by the Modern Voltage Stability Index (

MVSI) [

8]. In parallel, PMU-based voltage stability indices have been developed to improve temporal resolution for online monitoring [

17], while probabilistic assessment frameworks have been introduced to account for correlations among stochastic variables in renewable-rich networks [

18].

Despite these advances, such enhanced approaches often require higher computational effort, more detailed system parameters, or high-accuracy synchronized measurements, and many either neglect voltage-angle effects or incorporate them only implicitly. Moreover, most of these studies are validated primarily at the transmission level, leaving their applicability in tightly coupled transmission–distribution systems insufficiently explored.

At the transmission level, new analytical indices have been formulated to relax the restrictive two-bus assumptions while retaining closed-form expressions, which improve monotonicity near the collapse boundary and stabilize weak-bus or weak-corridor rankings under stressed conditions [

19]. Complementing this, integrated transmission–distribution (T–D) analyses show that coupling effects and three-phase asymmetry can reshape load margins and alter the consistency of local indicators, especially when RESs drive bidirectional power transfers and device setpoints vary over short time scales [

20,

21]. These advances call for indices that capture key couplings, remain relevant in real time, and remain valid under diverse conditions.

These developments highlight the need for a line-based index that preserves essential physical couplings while remaining simple enough for real-time implementation. Building on a two-port π line model, the proposed research study derives an enhanced voltage stability index (VSI) that explicitly retains line impedance, active and reactive power components, and the sending–receiving voltage-angle difference. The EVSI is evaluated on a coupled IEEE 30-bus transmission system and an IEEE 33-bus distribution system with the integration of solar photovoltaic systems, and its performance is benchmarked against classical indices such as FVSI, LSI, and LVSI. Simulation results demonstrate that the EVSI accurately approaches unity at the PV-curve nose point, provides consistent weak-bus identification under varying loadings and renewable penetrations, and maintains reliable proximity signals even when power-flow direction is reversed.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews conventional line-based VSIs and presents a detailed derivation of the proposed

EVSI.

Section 3 describes the coupled IEEE 30-bus and IEEE 33-bus test systems, photovoltaic penetration scenarios, and simulation procedures, and reports numerical results including PV-curve validation and benchmarking of

EVSI against classical indices under varying loads and generations.

Section 4 presents the conclusions and outlines directions for future work.

2. Methodology

2.1. Conventional Voltage Stability Indices

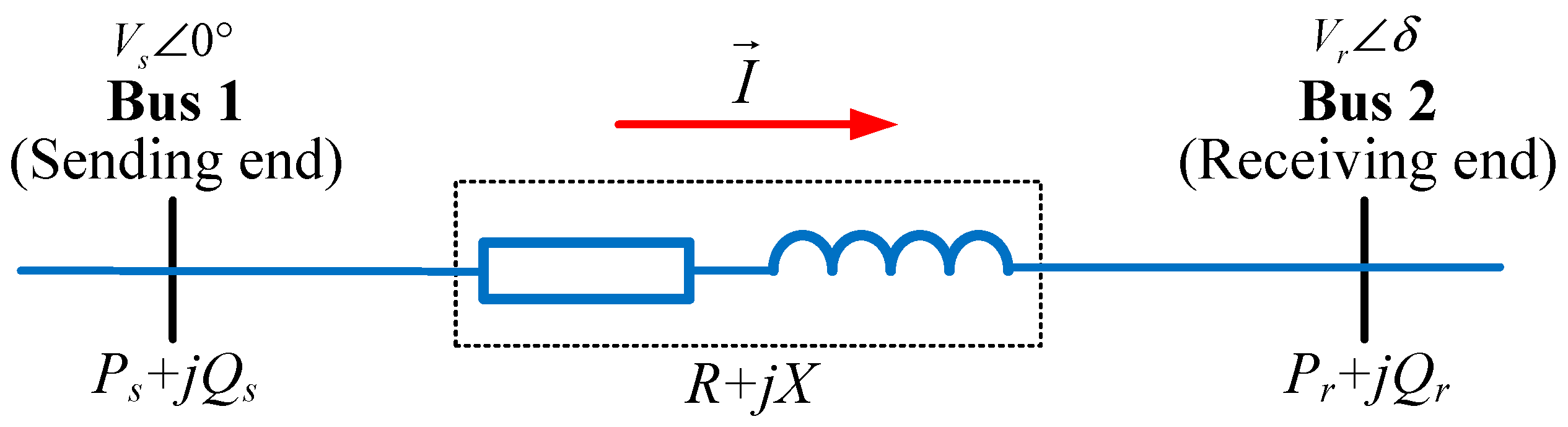

Upon completion of the load flow calculation, it is necessary to assess bus voltage stability, which requires a quantitative analytical index. A schematic diagram of a simplified line model is illustrated in

Figure 1, where

Vs∠0° and

Vr∠0° represent the voltage magnitudes and angles of the sending and receiving-end busbars, respectively;

Pr +

jQr and

Ps +

jQs represent the power of the sending and receiving-end busbars, respectively; and

R +

jX represents the impedance of the line.

Fast Voltage Stability Index (

FVSI):

FVSI is derived from a single transmission line connecting two buses, specifically focusing on the real roots of the receiving-end voltage [

5]. The formula is derived from the two-bus quadratic voltage equation under the small voltage-angle assumption and is defined in (1):

In (3), Vr is the voltage at the receiving end, Z is the line impedance, and δ is the voltage-angle difference between the receiving and sending ends.

- 2.

Line Stability Index

(LSI):

LSI serves as an indicator for assessing the stability of line voltage. When ignoring the voltage phase angle difference,

LSI and

FVSI have the same expression form [

6]:

In (4), θ represents the impedance angle of the line.

The LSI is commonly expressed in terms of the receiving-end reactive power to characterize voltage stability sensitivity dominated by reactive power variations.

Line Voltage Stability Index (

LVSI):

LVSI is derived from the relationship between the reactive power of the receiving end and the voltage of the sending end [

7]. The formula for

LVSI is expressed as follows:

In contrast, LVSI is formulated as a function of the receiving-end active power, reflecting an instability mechanism associated with real power loading.

Given the wide variety of available VSIs, this study focuses on commonly adopted and classical indicators. The aforementioned line-based VSIs represent a subset of the numerous other relevant indices in the literature. In addition, to provide a comprehensive yet concise reference, both bus-based and system-wide VSIs have been systematically selected and compiled in

Table 1, featuring the most established and frequently utilized indices in contemporary research and engineering practice.

In

Table 1,

A,

B,

C and

D are calculated by the

π model of a transmission line as a part of the two-bus system,

α and

β are phase angles of parameters

A and

B respectively;

αL is the set of load buses,

αG is the set of generator buses,

Uk and

Uj are the voltage phasors at buses

j and

i, and is the element in

j-th row and

i-th column of matrix

Fjk whose elements are generated from the admittance matrix as

F = −

YLL−1YLG; the dynamic equivalent impedance of the system is

ZiDYN; the static equivalent impedance of the load is

ZLD; Δ

Vr and Δ

Ir are the voltage and current differences between two consecutive measurement samples from a PMU at the receiving bus;

β1 = 1 − [max(|

Vm| − |

Vl|)

2];

Pgt,

Pdt and

Qdt are total active power generation, total active power demand and total reactive power demand, respectively.

Table 1 synthesizes the representative voltage stability indicators across the line, bus, and system levels. In essence, bus- and system-level indices leverage global network information and can provide rigorous margins; however, they typically rely on complete models, repeated power-flow solutions, or carefully conditioned Jacobian/sensitivity calculations, which complicate deployment for large networks experiencing frequent operating-point changes. In contrast, line-based VSIs operate with local phasors and branch parameters, scale naturally to large systems, and map directly to actionable assets (lines/corridors), making them well-suited for real-time screening and weak-bus/weak-corridor identification in RES-rich coupled transmission–distribution settings. Although such indices do not represent overall system stability, they offer a practical means of tracking the proximity to stressed operating conditions at the component level. Many classical formulations are derived from two-bus solvability conditions and may therefore provide optimistic proximity estimates relative to full-system collapse points. In this study, the proposed

EVSI is used in this established sense, and its behavior is examined as the system approaches voltage collapse, identified by PV-curve nose points and Newton–Raphson non-convergence. However, many classical line indices were derived under restrictive assumptions, for example, neglecting the voltage-angle difference (

δ ≈ 0), ignoring either active or reactive power, or adopting R ≈ 0/Y ≈ 0 approximations, which can yield conservative or misleading proximity signals under bidirectional transfers, large electrical distances, or rapidly varying setpoints driven by inverter-based generation.

As introduced above, several enhanced line-based voltage stability indices have been proposed in the recent literature, aiming to improve collapse prediction accuracy by relaxing one or more simplifying assumptions of classical formulations. Compared with these indices, the proposed EVSI differs in three key ways. First, EVSI explicitly retains the voltage-angle difference as a primary variable, rather than assuming small-angle conditions or implicitly embedding angle effects. Second, EVSI preserves the coupled contributions of active and reactive power flows within a unified discriminant-based formulation, avoiding dominance by a single power component. Third, EVSI is explicitly evaluated in a coupled transmission–distribution environment, where renewable-driven bidirectional flows and electrical-distance effects are most pronounced. These distinctions are critical for maintaining the monotonicity and interpretability of the index near the voltage collapse boundary under renewable-rich operating conditions.

Against this backdrop, we focus on line-based monitoring and adopt three widely used baselines—FVSI, LSI, and LVSI—because they epitomize the canonical modeling choices seen in practice (δ-neglect, P-dominant, or Q-dominant simplifications) and remain the most commonly implemented tools for contingency ranking and online monitoring. Benchmarking the proposed index against these classical yet influential baselines provides a transparent and fair yardstick to demonstrate the benefits of our method, especially its ability to retain angle dependence and coupled P–Q effects while maintaining algebraic simplicity for online use.

2.2. Enhanced Voltage Stability Index

Motivated by the above gaps, we next derive an enhanced line-based index that preserves essential physical couplings without sacrificing closed-form tractability.

As shown in

Figure 1, the transmission line current can be expressed as

Meanwhile, the complex power at the receiving end can be expressed as

By combining (6) and (7), the current can be expressed as

Substituting (6) into (8), we obtain

Expanding (9) and segregating the real and imaginary portions yields

Solve the system in (10) to obtain the expressions for

Pr and

Qr:

In (11), the terms [(

Vscos

δ-

Vr)·

R/Z

2] and (

Vssin

δR/Z

2) originate from the linear contribution of line resistance. To simplify the analytical formulation, these resistance-weighted linear terms are neglected, while the resistance effect is retained in the impedance magnitude

. This treatment avoids adopting a fully lossless assumption (

) and preserves the dominant impedance influence on voltage stability. Similar partial resistance approximations have been employed in recent line-based voltage stability indices to balance the modeling accuracy and computational simplicity, particularly under practical operating conditions [

8]. Under these circumstances, rearranging (11), the active and reactive powers at the receiving end of the line can be written as

To derive a unified quadratic voltage expression, a composite power term is introduced by linearly combining the active and reactive power components in (12), as follows: Specifically, the two expressions are summed to obtain (13).

Equation (13) is a quadratic expression with respect to the receiving-end voltage. For a physically meaningful operating point to exist, this quadratic equation must admit a real solution, which requires its discriminant to be non-negative, as expressed in (14):

By rearranging the discriminant condition and grouping the associated parameters, the resulting inequality can be expressed in a compact normalized form, leading to the index representation in (15):

From (15),

EVSI can be expressed as

For a system to maintain stability, the value of

EVSI must remain below one; otherwise, the onset of collapse becomes imminent. The proposed

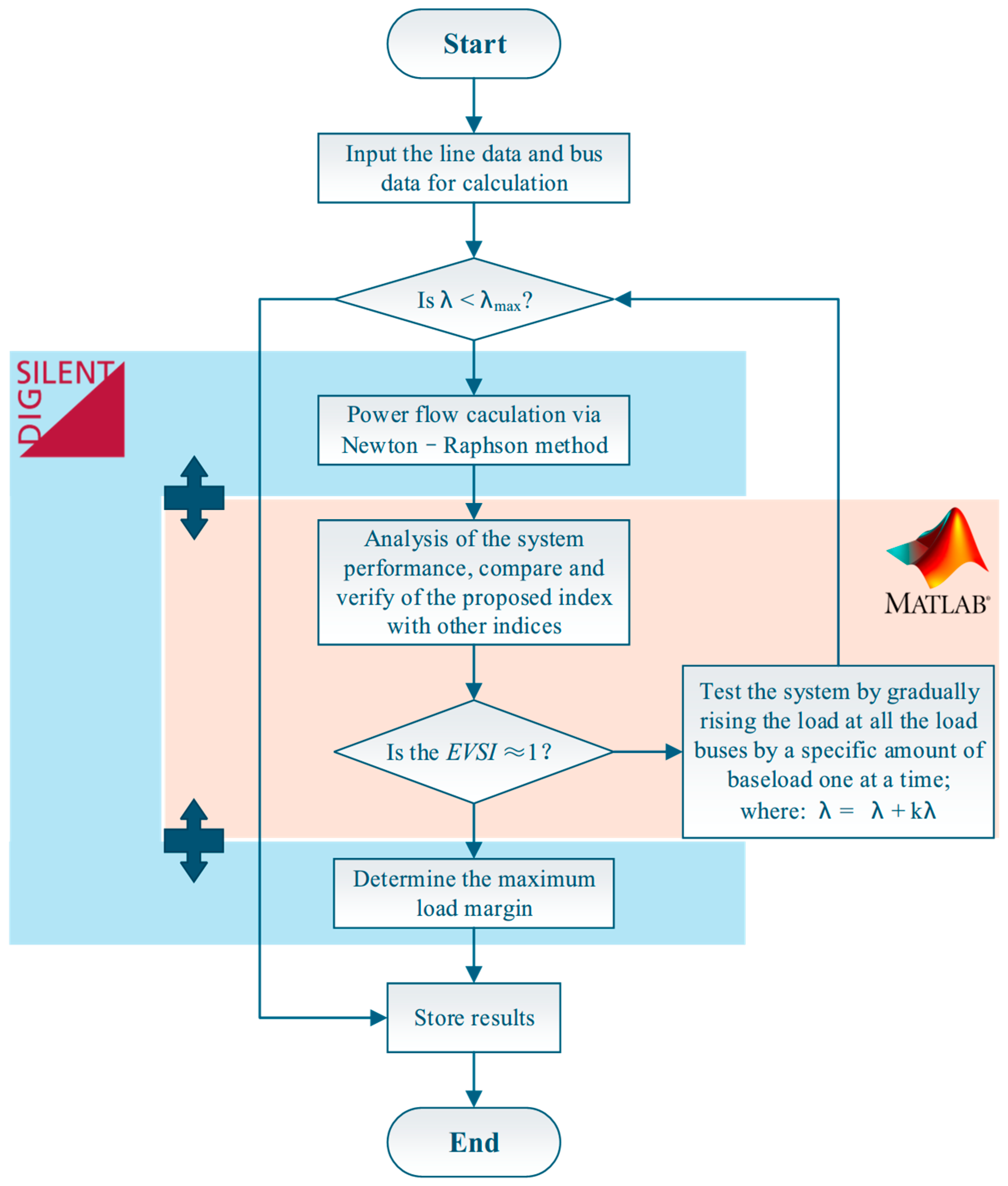

EVSI is meticulously designed to comprehensively encompass all pertinent parameters and variables pertinent to transmission lines that are associated with voltage collapse, thereby ensuring the precision, efficacy, and swiftness of collapse prediction and applicability to RES grid integration scenarios. The evaluation process of the proposed method is illustrated in

Figure 2.

As illustrated in

Figure 2,

λ represents the base operating load, and k denotes the scaling factor used to progressively increase the system demand. The incremental variation of k enables the assessment of maximum loading capability, weak areas, and voltage stability margin. The loading process continues until the stability limit is encountered, at which point the maximum permissible load and associated loading margin are obtained.

Since

EVSI is formulated directly from steady-state voltage phasors, power injections, and line parameters, its numerical value varies smoothly with respect to small perturbations in voltage magnitude and angle measurements. In practice, these quantities can be obtained from synchronized phasor measurements or state estimation outputs, the typical accuracy levels of which are sufficient for static monitoring purposes. As

EVSI does not rely on iterative solvers or numerical differentiation, moderate measurement noise primarily introduces proportional variations rather than structural distortion of the index [

38]. A comprehensive sensitivity analysis considering explicit measurement noise models and communication delays would provide further insight into field deployment; therefore, it is identified as a direction for future work.

The effectiveness of the proposed

EVSI is demonstrated in

Section 3.

3. Simulation Results

This case study examines the effect of coupled transmission and distribution (T&D) systems on busbar voltage stability under different penetrations of grid-integrated RES. The transmission network adopts the IEEE-30-bus system, and the distribution network adopts the IEEE-33-bus system, with solar photovoltaic generation as the selected RES. In addition, we verified the accuracy of the proposed EVSI by computing PV curves and checking whether EVSI equals 1 at the PV-curve nose (voltage collapse) point for the relevant buses and penetration levels; any deviation from 1 is reported as the accuracy measure.

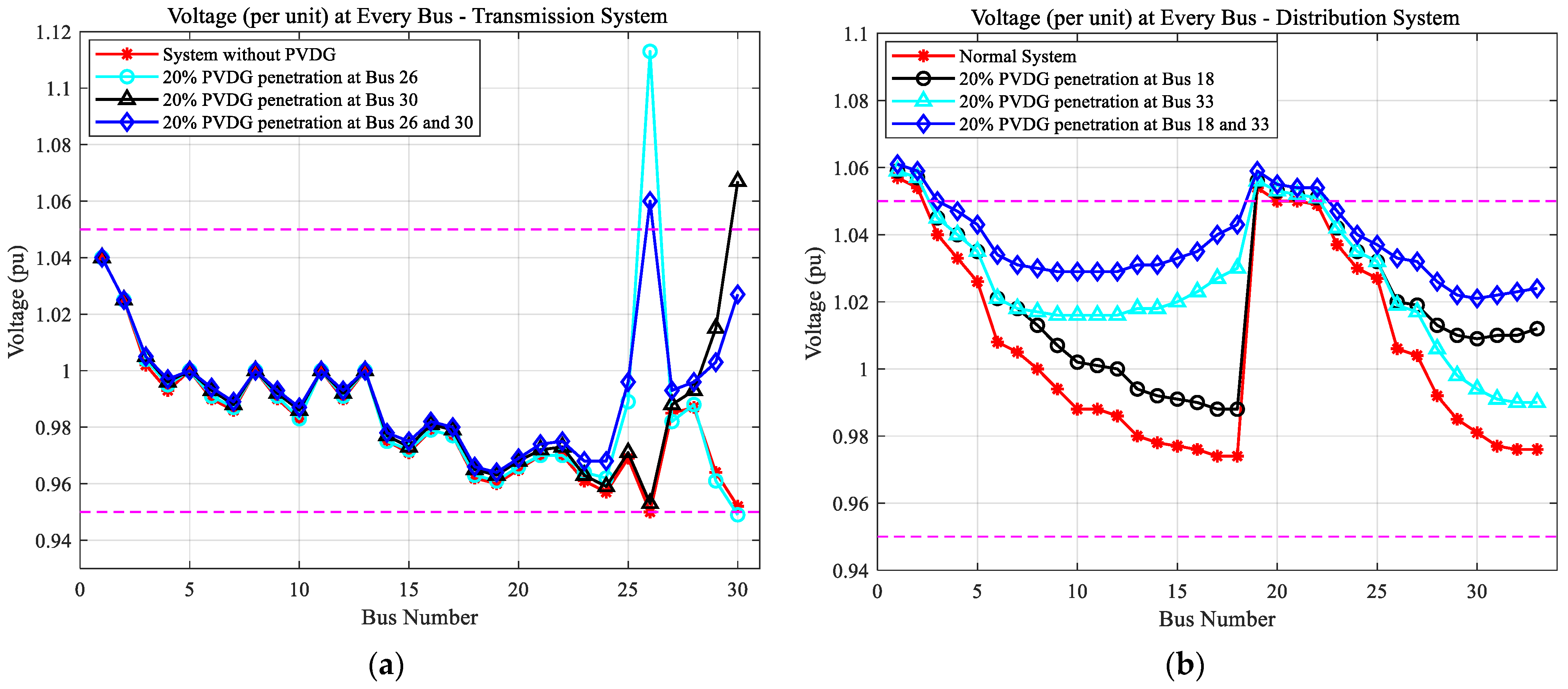

The power system model is constructed using DIgSILENT PowerFactory 2024 SP4 (x64) and MATLAB R2023b, as shown in

Figure 3. Buses 26 and 30 in the transmission network and Buses 18 and 33 in the distribution network are chosen as RES grid connection points due to their low voltage amplitudes [

39]. DIgSILENT PowerFactory is employed to obtain steady-state power-flow solutions for the studied operating scenarios, on which the proposed

EVSI and the benchmark indices are evaluated in a coupled transmission–distribution framework. The voltage level of the transmission system operates at 132 kV/33 kV, while the distribution system is a 33-node radial system with a rated voltage of 12.66 kV and power of 100 MVA.

First, the Newton−Raphson algorithm is used to determine busbar voltage levels. The PV curves of synchronously growing loads are then simulated to calculate the load margin and voltage stability. In this work, PV curves obtained under synchronous load increase are used as a system-level reference for voltage collapse assessment. While different load-increase directions may result in different PV characteristics, the adopted loading pattern provides a consistent and widely used benchmark for comparative evaluation of voltage stability indices. The PV-curve nose point, identified by load-flow non-convergence, is employed solely to examine whether an index approaches unity near collapse, rather than to represent all possible instability scenarios. Other forms of static voltage stability analysis, such as QV curves, are also commonly used and provide complementary perspectives, particularly under reactive power-dominated operating conditions.

This section examines busbar voltage levels and PV-curve changes at critical buses, evaluates photovoltaic distributed generation (PVDG) performance under different penetration rates, and observes bus voltage deviations from the rated value (±5%).

The mathematical expression for the PVDG penetration level is given in (17):

3.1. Voltage Magnitude and Load Margin

According to the simulation results in [

39], it can be concluded that simultaneous power injection at buses 18 and 33 has the best improvement in voltage distribution across the power grid, enabling voltage fluctuations within the allowable range (±5%). However, [

39] assumes a constant external grid voltage and fixed PVDG injection power, which is impractical. Therefore, in this section, the external power grid is replaced with an IEEE 30-bus transmission system, and the simulation time is set to 1 pm when the PVDG output power reaches its peak.

The voltage profiles for different scenarios are shown in

Figure 4. In

Figure 4a, the integration of PVDG into the IEEE 30-bus transmission system increases the voltage magnitude at several buses; however, the additional power injection also introduces sharper variations, leading to voltage values that exceed the acceptable ±5% range at certain buses. This indicates that although the PVDG supports the overall voltage level, its impact is highly location dependent and can create localized overvoltage conditions. Similarly,

Figure 4b illustrates the voltage characteristics of the IEEE 33-bus distribution network. Even with compensation from buses 18 and 33, the per-unit voltage cannot be maintained below the upper limit of 1.05 p.u. for all buses. Simultaneous injections at these two buses reduce voltage drops in some areas but also increase the likelihood of surpassing the permissible voltage limit elsewhere. These results demonstrate that while PVDG improves voltage magnitude on average, the resulting spatial variability must be properly managed to avoid new voltage violations.

As in the above analysis, although PVDG can increase system voltage levels by injecting additional power into the grid, this case study did not take into account the variability of PVDG power output caused by changes in weather conditions, which can result in instantaneous voltage fluctuations exceeding or falling below the allowable range.

Noting the weakest load capacity at buses 26 and 30 in the IEEE 30-bus transmission system, buses 26 and 30 are designated as RES connection points [

40]. Accordingly, the PV curves at buses 26 and 30 are plotted in

Figure 5 for the following scenarios: (1) original system without PVDG; (2) 20% PVDG grid integration at Bus 26; (3) 20% PVDG grid integration at Bus 30; and (4) 20% PVDG grid integration at buses 26 and 30 (10% each). It can be seen that connecting two PVDGs with a penetration rate of 20% at buses 26 and 30 increases the load margin by 22.326% and 22.317%, respectively.

For line-based VSIs, if their values surpass 1, it signifies that the line is nearing instability, potentially leading to a voltage collapse in the entire system. Based on the analysis of VSIs mentioned above, the simulated data acquired from DIgSILENT PowerFactory is used in conjunction with MATLAB to calculate the values of the selected VSIs for the same four scenarios as mentioned above. The following critical lines are selected for the analysis, and their basic data are shown in

Table 2.

Based on the above conditions, the output results of each VSI are shown in

Table 3.

For each scenario,

FVSI,

LSI, and

LVSI are first evaluated on all selected critical lines listed in

Table 2 using their standard formulations, together with the corresponding power flow results obtained from DIgSILENT PowerFactory. Since each line exhibits different sensitivities to changes in active and reactive power under RES integration, the individual index values vary across the network. To provide a concise scenario-level summary, the values obtained for the selected lines are aggregated using simple summation. The resulting totals offer a compact indication of the overall behavior of each index across operating scenarios and allow its trends to be compared in a straightforward manner.

When considering RES grid integration and the proportion of grid integration is increasing, the values of VSIs have risen to varying degrees at most buses, as shown in

Table 3.

For each operating scenario,

FVSI,

LSI, and

LVSI are evaluated on the selected critical lines listed in

Table 2 using the corresponding power flow results. Since voltage stability stress is distributed across multiple lines rather than concentrated on a single element,

Table 3 summarizes the cumulative index values obtained by summing the results over the selected lines. This representation provides an overall indication of how each index responds to increasing loading and RES penetration at the scenario level, enabling a direct comparison of their relative sensitivity and trend consistency.

Based on the analysis of the above data, it can be concluded that with the grid integration of RES, the corresponding bus sees an additional active power, which changes the power flow and increases the uncertainty and burden of grid operation. According to the data in

Table 3, there are significant differences between these three indices in the RES grid integration scenario, indicating that some of the VSIs are no longer reliable.

A comparison of these VSIs, which depend on the line parameters and active/reactive power variables at buses, shows that the threshold values are influenced by the associated variables and assumptions. An additional load at this point can lead to voltage collapse and line interruption, potentially causing cascading outages and grid blackouts, especially if it impacts other lines. Equation (4) indicates

LSI is directly proportional to the reactive power, showing low sensitivity to the real power changes. However, under a RES-rich grid integration scenario,

LSI responds significantly due to its indirect dependence on active power through voltage-angle differences. According to the Equation (5), there is a direct relationship between the voltage angle difference and the active power [

41]. As shown in

Table 3, the

LSI/

LVSI values for Scenarios 3 and 4 are significantly higher than those for Scenario 1.

The FVSI, a simplified

LSI/

LVSI index assuming zero voltage-angle difference, provides quick but inaccurate results for large angle differences [

8]. As shown in

Table 3, the

FVSI values are significantly more conservative than the other two VSIs.

In summary, the increasing proportion of RES in a grid introduces uncertainties and unique physical characteristics that diminish VSI accuracy. Therefore, this paper proposes EVSI as a new index to fill this gap.

3.2. Performance of the Newly Proposed Enhanced Voltage Stability Index

Building on the testbed and scenarios in this section, the IEEE 30-bus transmission network is used to benchmark

EVSI against conventional indices such as

FVSI,

LSI, and

LVSI. Significant active and reactive power loadings were progressively applied to buses 26, 29, and 30, as summarized in

Table 4. Starting from the base case, which is solved using the Newton–Raphson (NR) power flow, P or Q at a target bus is increased while holding the remaining power injections fixed. After each increment, the power flow is resolved, and all indices are evaluated. The process continues until the NR solver no longer converges, which indicates that the operating point has reached the PV curve’s nose and the system is operating on the stability boundary. At this boundary, a properly normalized VSI approaches unity. This setup provides a like-for-like basis for comparing the tracking behavior, weak-location ranking, and sensitivity to P-Q coupling under RES-driven grid scenarios.

In

Table 4, dark blue indicates that the value is closest to 1, while light blue, green, and orange sequentially represent values that deviate increasingly from 1 compared to other data within the same group. Moreover, the yellow squares represent the critical line at a particular bus and indicate that the simulated outcomes of VSIs should be 1.

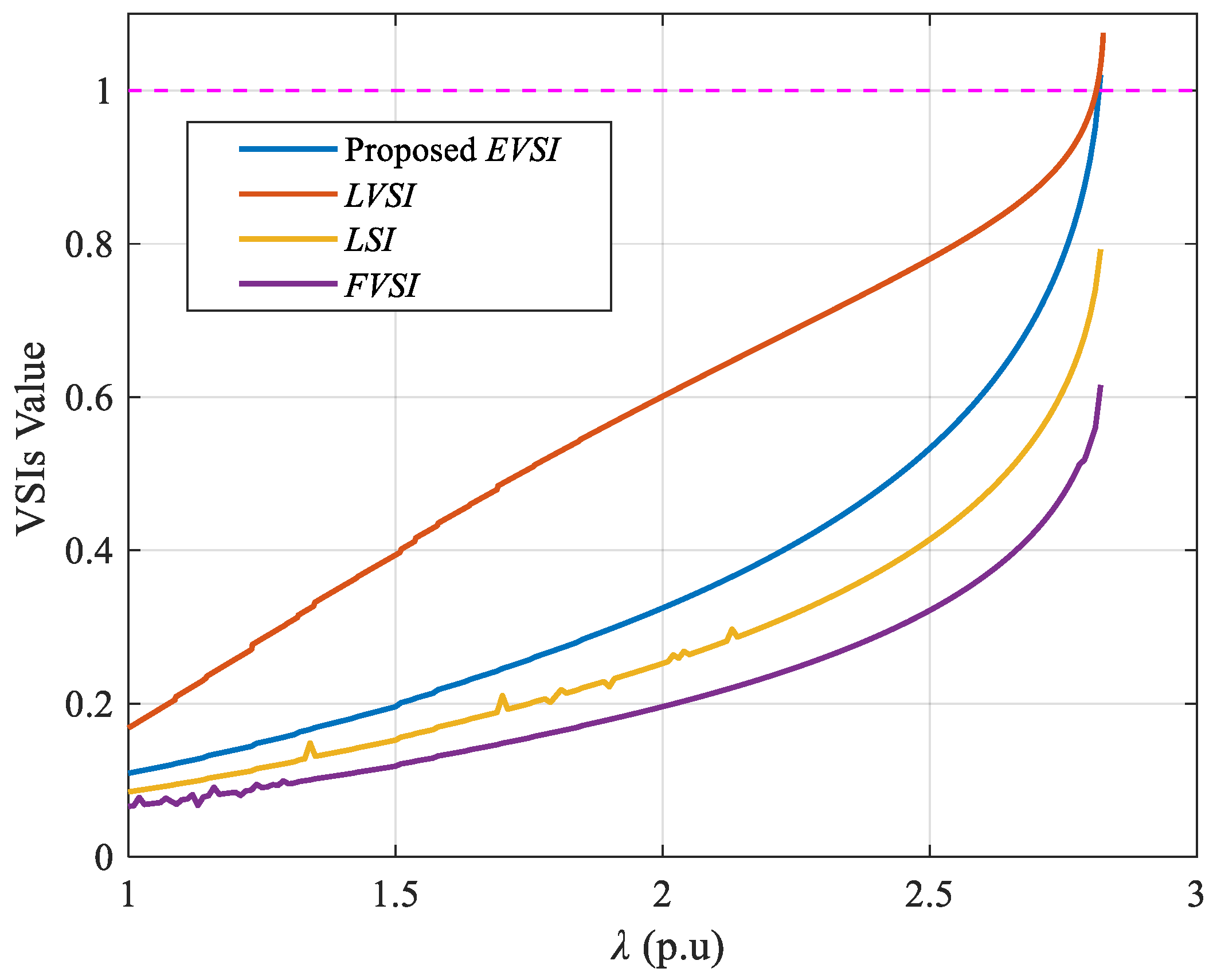

To address the continuous behavior of

EVSI along the PV loading path,

Figure 6 shows the index trajectory for a representative case (active power increase at Bus 26). In this case,

EVSI increases smoothly and monotonically with loading and approaches unity as the operating point reaches the PV-curve nose (NR non-convergence), which is consistent with the normalization requirement discussed above. Similar monotonic trends were observed for the other loading cases reported in

Table 4; therefore, only this representative trajectory is shown to avoid redundancy.

Meanwhile, as shown in

Table 4, the proposed

EVSI exhibits excellent response levels for both high-active and reactive power scenarios. The values are closest to 1 at the selected buses, attesting to the accuracy and reliability of

EVSI. In contrast, the response effectiveness of

FVSI is generally poor, demonstrating better performance for reactive power scenarios than for active power scenarios. However, it should be noted that

FVSI is less accurate than the other indices in most cases, even for reactive power scenarios. Conversely,

LSI, which takes into account voltage-angle differences and active power but overlooks branch impedances, disregards voltage drops caused by line impedances, thereby impacting its accuracy to some extent. Similarly,

LVSI faces issues similar to

LSI, neglecting the influence of reactive power and line impedances. Consequently,

FVSI,

LSI, and

LVSI must be interpreted differently for power fluctuations within the system, such as by means of RESs.

In summary, through derivation, the proposed EVSI retains parameters such as node active power, reactive power, voltage-angle differences, and line impedances, comprehensively considering the influence of various system parameters on voltage stability to a greater extent. Simulation results demonstrate the potential of EVSI for effective implementation in RES-rich scenarios.

4. Conclusions

An enhanced line-oriented voltage stability index, EVSI, has been formulated using a two-port π representation that retains the coupling among active and reactive powers, line impedance, and voltage-angle difference between the sending and receiving ends. In coupled transmission and distribution settings with PVDG, the index provided a coherent and physically interpretable proximity measure to voltage collapse, yielded consistent rankings of weak buses and corridors, and showed less dispersion than classical VSIs across changes in loadings and renewable penetration. The EVSI expression is compact and relies on easily accessible measurements and parameters, which support its integration into energy management system workflows for rapid screening, margin tracking, and alarm threshold setting. It also complements PV-curve-based planning by supplying local, real-time signals without iterative continuation.

Future research could broaden the framework to a wider range of operating conditions and network configurations, incorporate peculiar device behaviors and uncertainty representations, and explore pathways to deployment that include online visualization, operator decision support, and experimental or field-level demonstrations.