Purification of Methane Pyrolysis Gas for Turquoise Hydrogen Production Using Commercial Polymeric Hollow Fiber Membranes

Abstract

1. Introduction

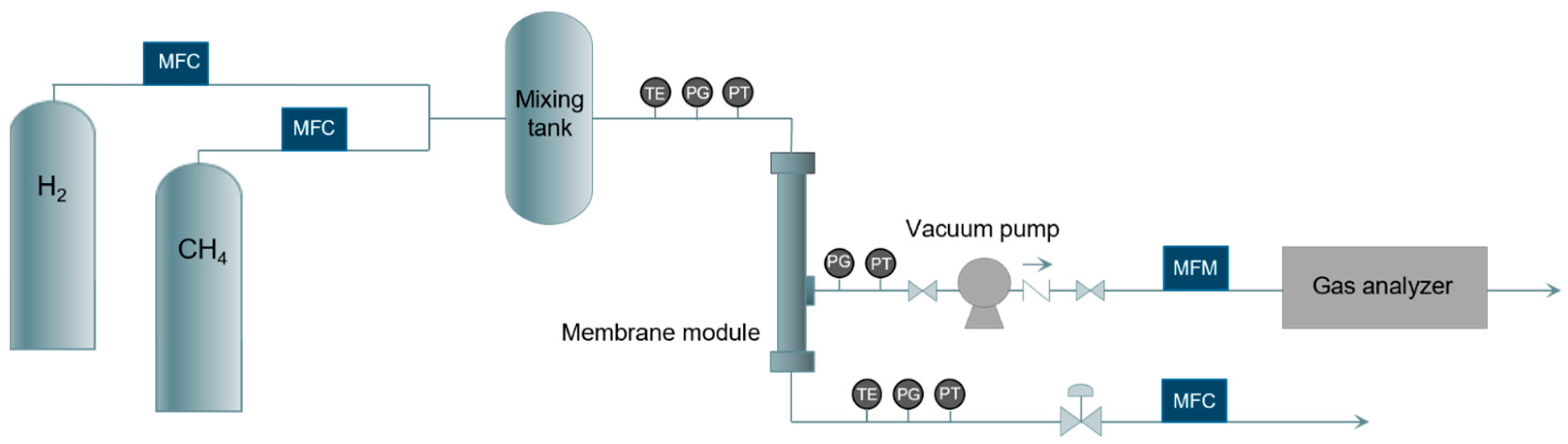

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

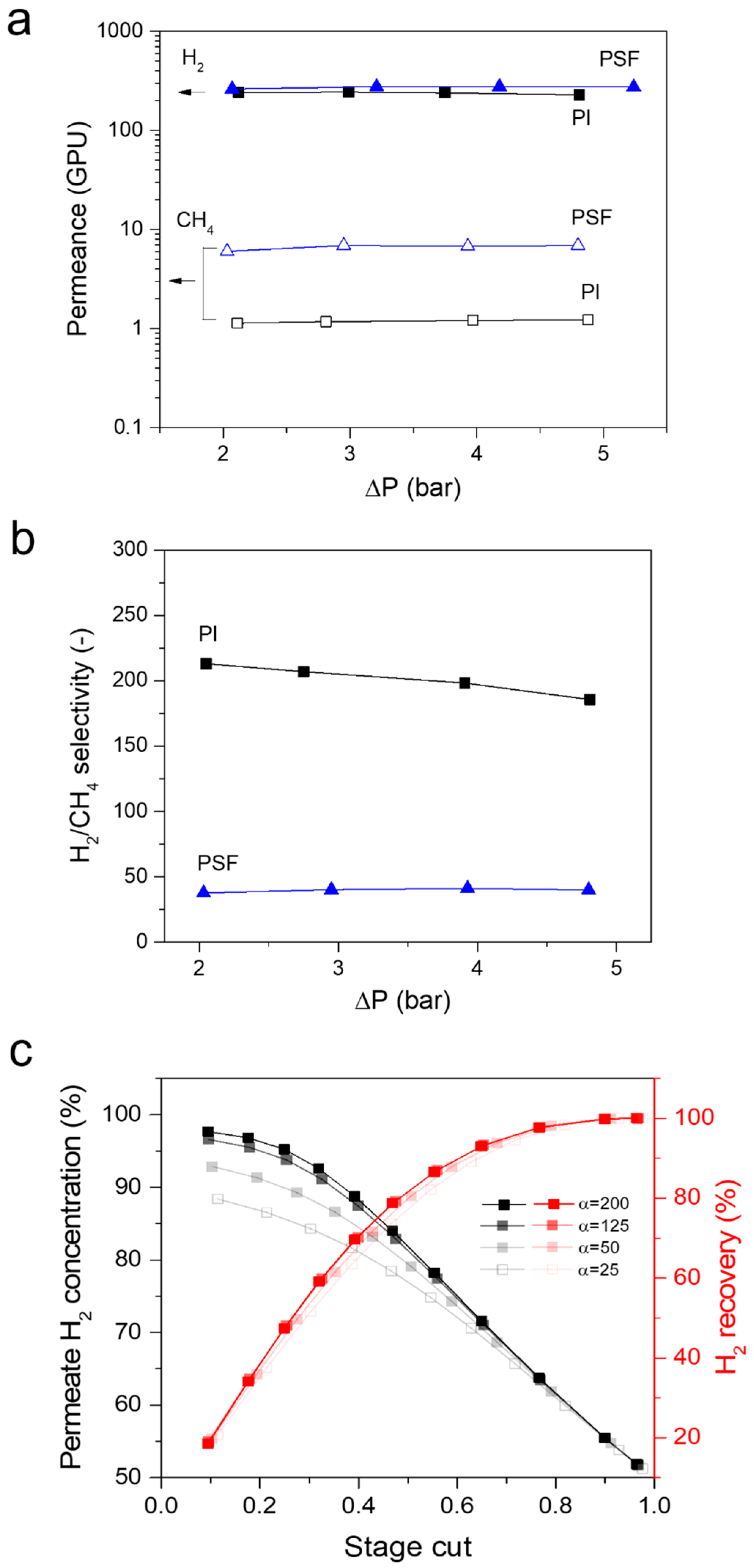

3.1. Single Gas Transport Properties of Membranes

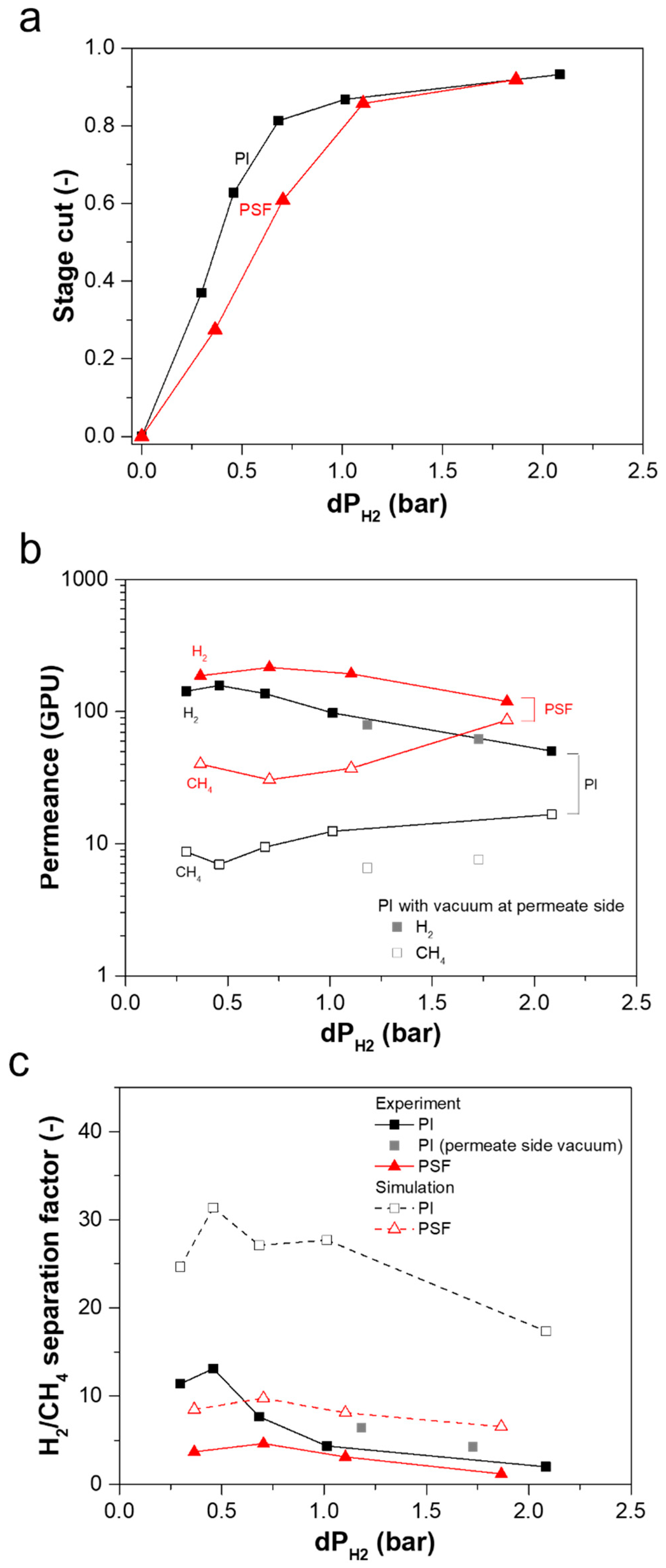

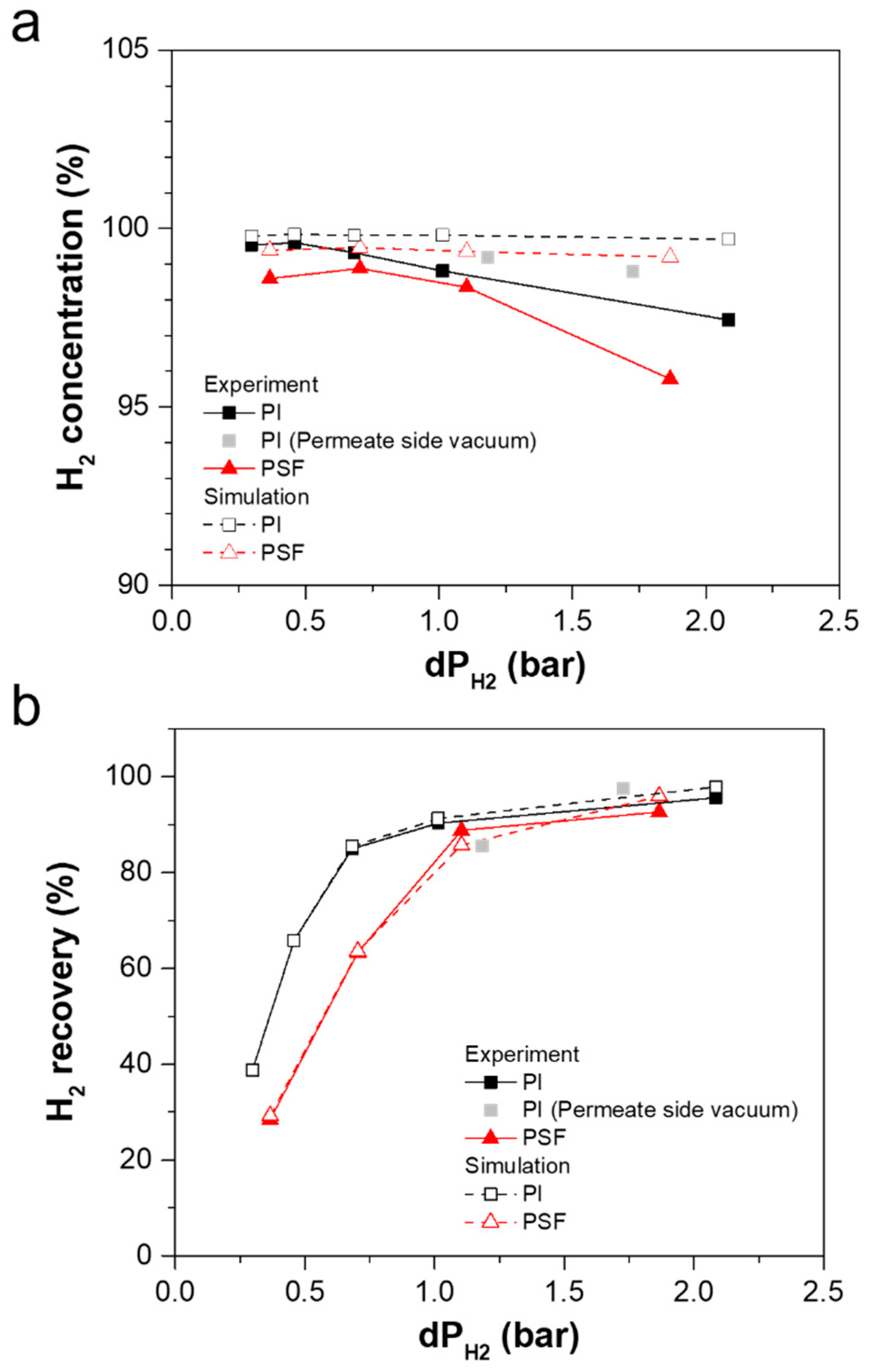

3.2. Effect of Process Parameters on Mixed-Gas H2/CH4 Separation Performance

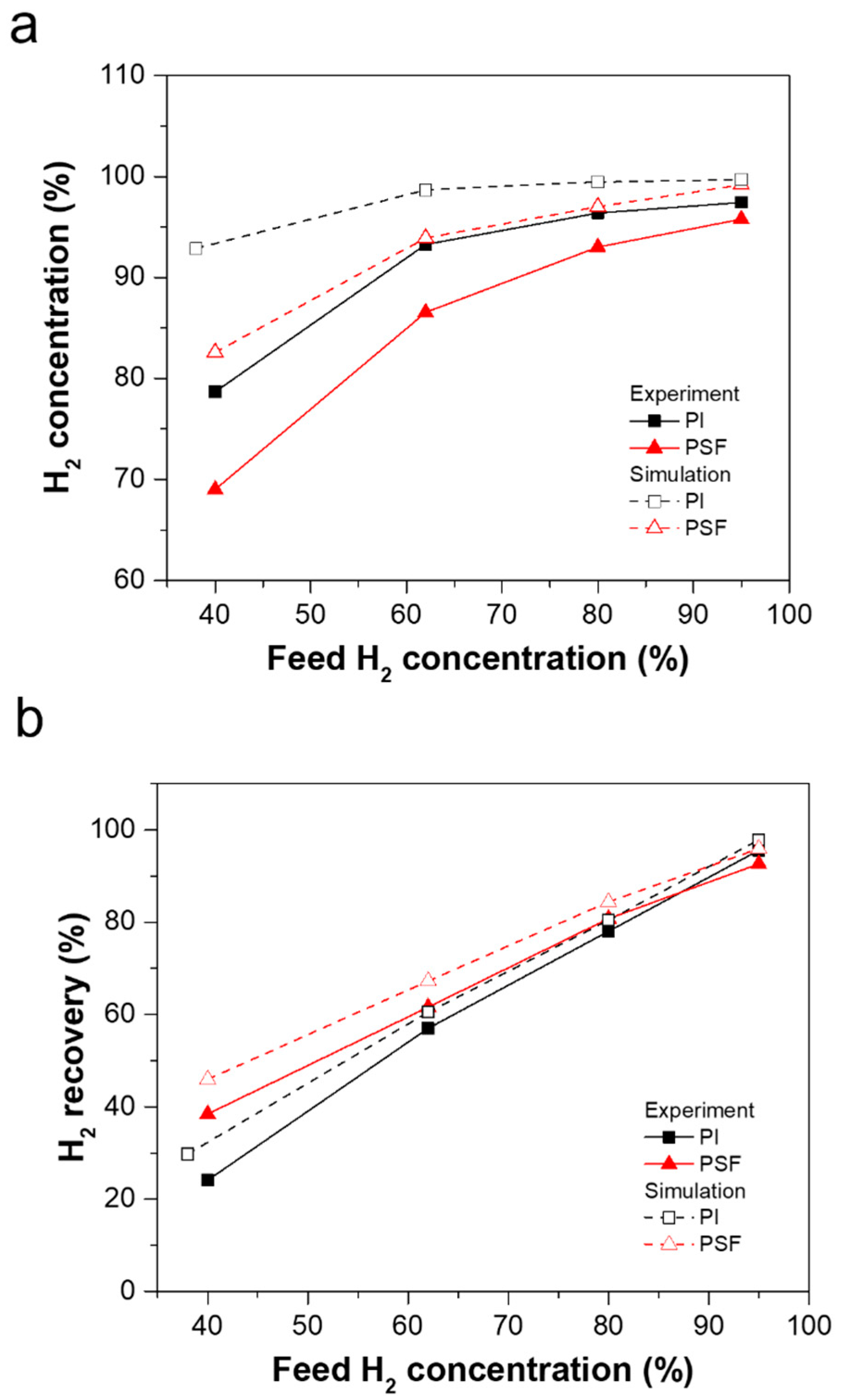

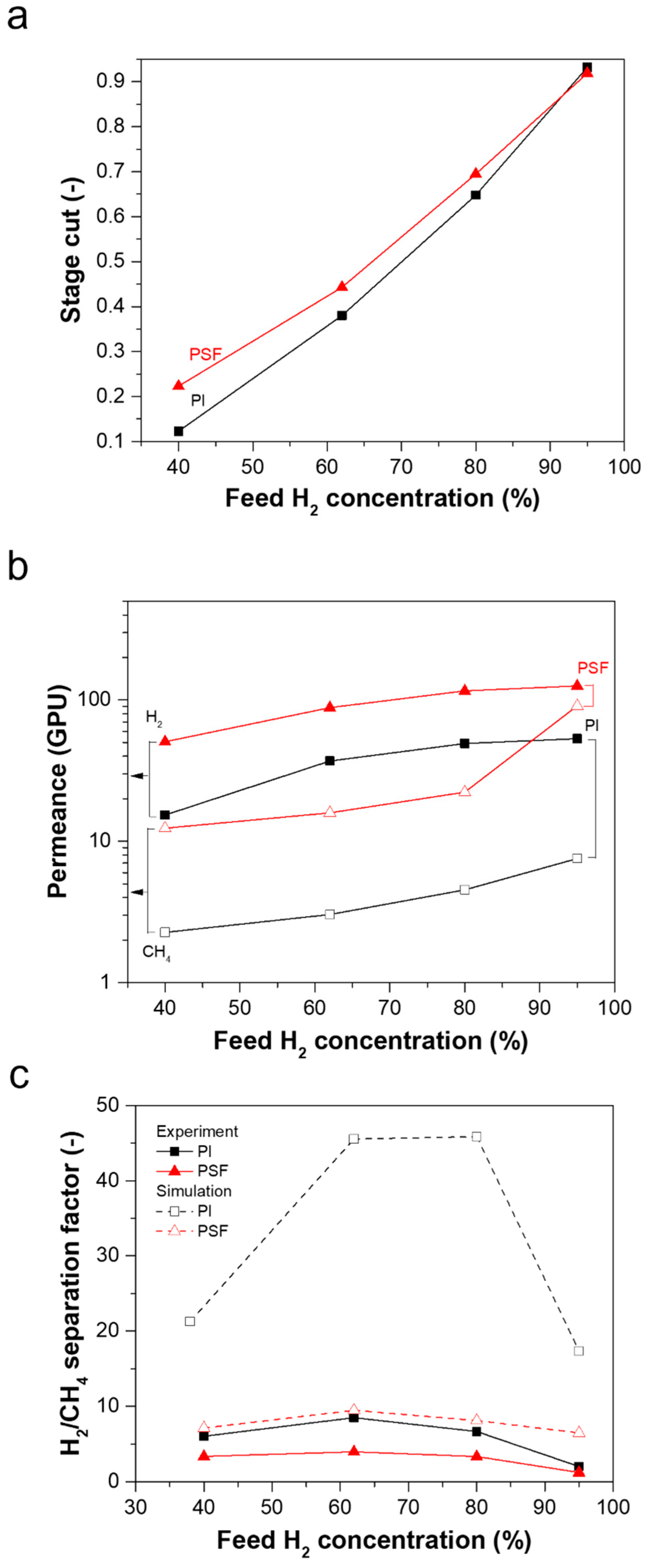

3.2.1. Effect of Feed Composition on Separation Performance

3.2.2. Effect of Feed Pressure on Separation Performance

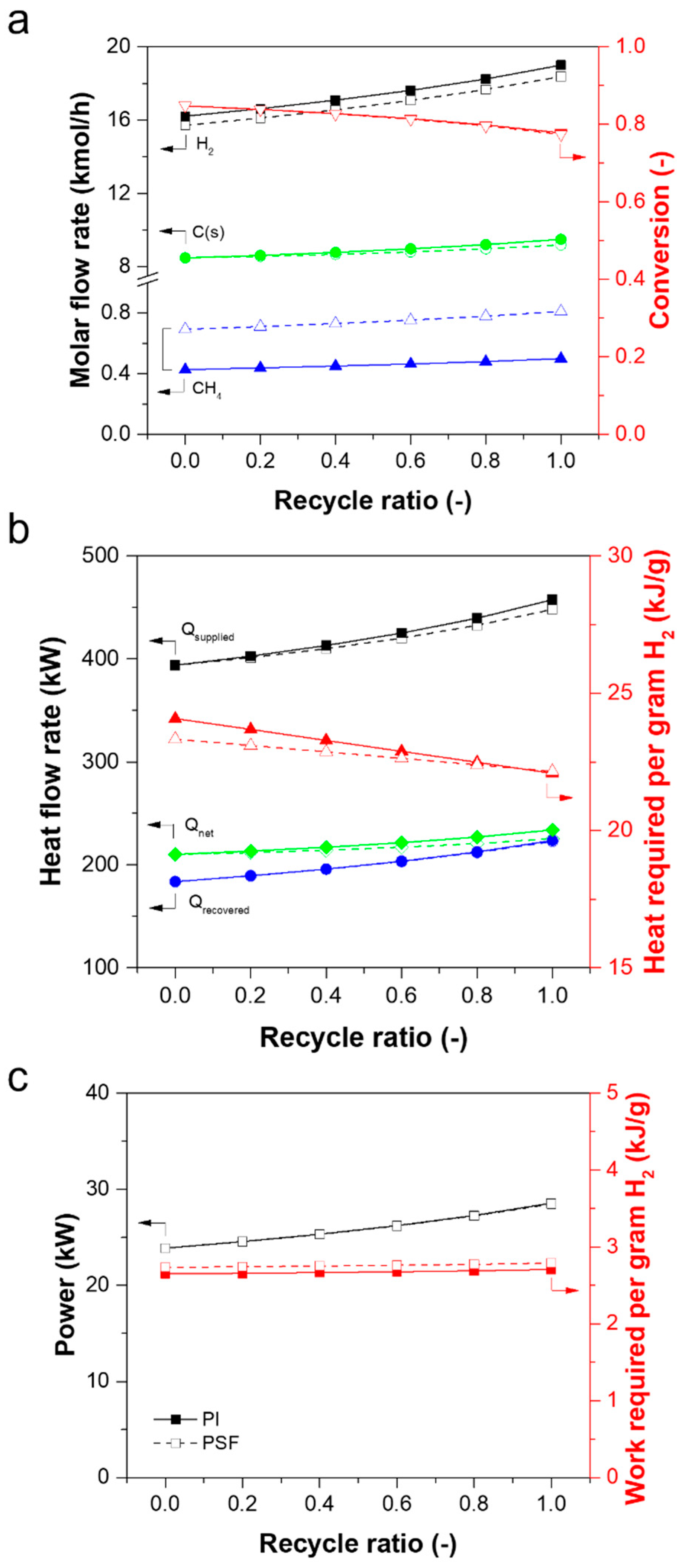

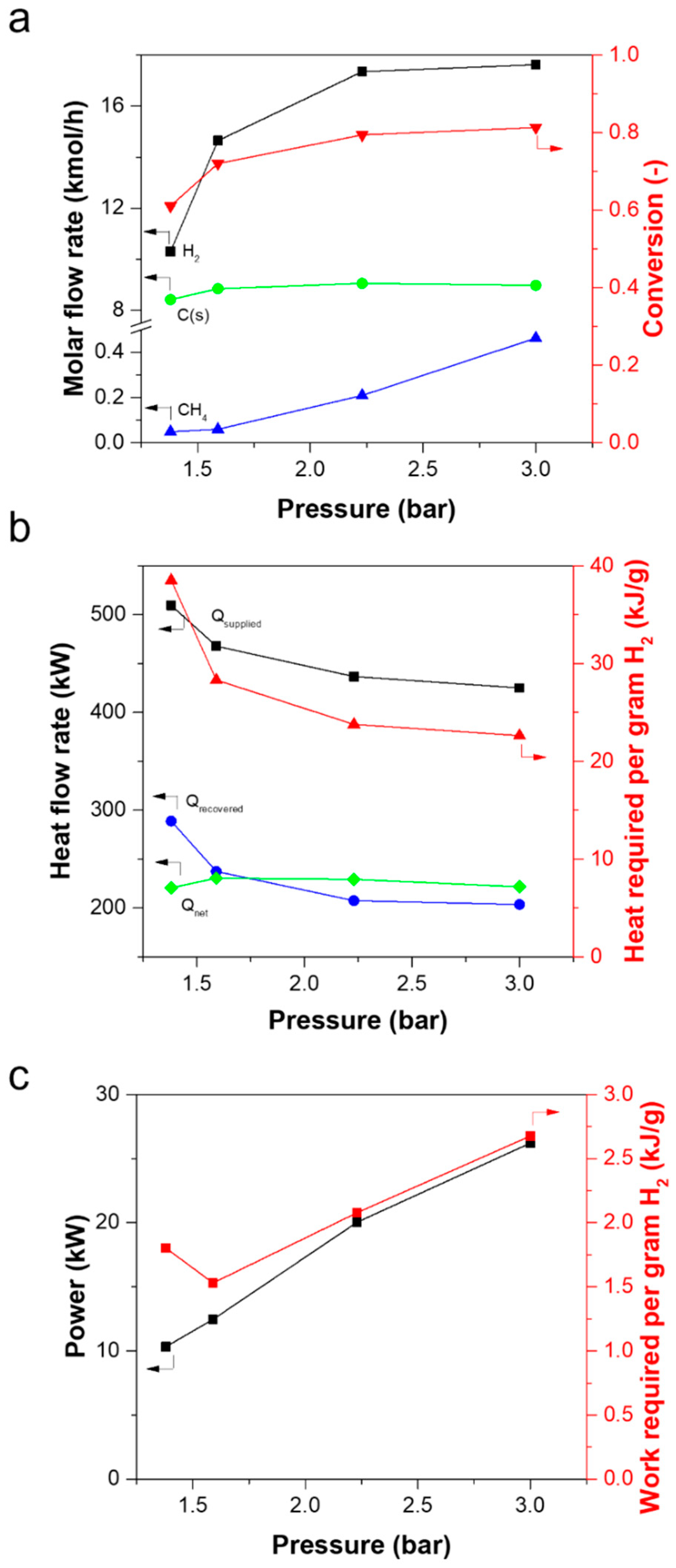

3.3. Simulation of the Performance of a Methane Pyrolysis Reaction Process Equipped with a Membrane

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alhamed, H.; Behar, O.; Saxena, S.; Angikath, F.; Nagaraja, S.; Yousry, A.; Das, R.; Altmann, T.; Dally, B.; Sarathy, S.M. From Methane to Hydrogen: A Comprehensive Review to Assess the Efficiency and Potential of Turquoise Hydrogen Technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 68, 635–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi, M.; Teymouri, N.; Ashrafi, O.; Navarri, P.; Khojasteh-Salkuyeh, Y. Methane Pyrolysis as a Potential Game Changer for Hydrogen Economy: Techno-Economic Assessment and GHG Emissions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 66, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, A.L.; Hejazi, S.; Fattahi, M.; Kibria, M.G.; Thomson, M.J.; AlEisa, R.; Khan, M.A. Methane Pyrolysis for Hydrogen Production: Navigating the Path to a Net Zero Future. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 2747–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/low-emission-fuels/hydrogen (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ullah, I.; Amin, M.; Zhao, P.; Qin, N.; Xu, A.-W. Recent Advances in Inorganic Oxide Semiconductor-Based S-Scheme Heterojunctions for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 1329–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Rana, R.; Zheng, Y.; Kozinski, J.A.; Dalai, A.K. Insights on Pathways for Hydrogen Generation from Ethanol. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2017, 1, 1232–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abánades, A.; Rubbia, C.; Salmieri, D. Technological Challenges for Industrial Development of Hydrogen Production Based on Methane Cracking. Energy 2012, 46, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, J.; Lai, L.; Chivers, B.; Burke, D.; Dinh, A.H.; Ye, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, L.; Chen, Y. Solid Carbon Co-Products from Hydrogen Production by Methane Pyrolysis: Current Understandings and Recent Progress. Carbon 2024, 216, 118507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsvik, O.; Rokstad, O.A.; Holmen, A. Pyrolysis of Methane in the Presence of Hydrogen. Chem. Eng. Technol. 1995, 18, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Bhanja, K.; Mohan, S. Simulation Studies of the Characteristics of a Cryogenic Distillation Column for Hydrogen Isotope Separation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 5003–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liemberger, W.; Groß, M.; Miltner, M.; Harasek, M. Experimental Analysis of Membrane and Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) for the Hydrogen Separation from Natural Gas. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockwig, N.W.; Nenoff, T.M. Membranes for Hydrogen Separation. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4078–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, X.; Caro, J.; Huang, A. Polymer Composite Membrane with Penetrating ZIF-7 Sheets Displays High Hydrogen Permselectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16156–16160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Sanip, S.M.; Ng, B.C.; Aziz, M. Recent Advances of Inorganic Fillers in Mixed Matrix Membrane for Gas Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 81, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.J.; An, H.; Shin, J.H.; Brunetti, A.; Lee, J.S. A New Dip-Coating Approach for Plasticization-Resistant Polyimide Hollow Fiber Membranes: In Situ Thermal Imidization and Cross-Linking of Polyamic Acid. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Brunetti, A.; Drioli, E.; Barbieri, G. H2 Separation from H2/N2 and H2/CO Mixtures with Co-Polyimide Hollow Fiber Module. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2010, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaheem, Y.; Alomair, A.; Vinoba, M.; Pérez, A. Polymeric Gas-Separation Membranes for Petroleum Refining. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 2017, 4250927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qian, X.; Xiao, C.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Han, Z.; Lin, L. Advancements in Purification and Holistic Utilization of Industrial By-Product Hydrogen: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Green Energy Resour. 2024, 2, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mivechian, A.; Pakizeh, M. Hydrogen Recovery from Tehran Refinery Off-Gas Using Pressure Swing Adsorption, Gas Absorption and Membrane Separation Technologies: Simulation and Economic Evaluation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patibandla, A. Process Deisgn & Economic Analysis of Methane Pyrolysis for Production of Hydrogen from Natural Gas. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Keipi, T.; Li, T.; Løvås, T.; Tolvanen, H.; Konttinen, J. Methane Thermal Decomposition in Regenerative Heat Exchanger Reactor: Experimental and Modeling Study. Energy 2017, 135, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, K.; Freeman, B.D. Gas Separation Using Polymer Membranes: An Overview. Polym. Adv. Technol. 1994, 5, 673–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. The Upper Bound Revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakizeh, M.; Moghadam, A.N.; Omidkhah, M.R.; Namvar-Mahboub, M. Preparation and Characterization of Dimethyldichlorosilane Modified SiO2/PSf Nanocomposite Membrane. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Treviño, F.A.; Paul, D.R. Modification of Polysulfone Gas Separation Membranes by Additives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 66, 1925–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, S.; Steiner, W.A. Separation of Gases by Fractional Permeation through Membranes. J. Appl. Phys. 1950, 21, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koros, W.J.; Fleming, G.K. Membrane-Based Gas Separation. J. Membr. Sci. 1993, 83, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juaied, M.; Koros, W.J. Performance of Natural Gas Membranes in the Presence of Heavy Hydrocarbons. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 274, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.Q.; Koros, W.J.; Miller, S.J. Effect of Condensable Impurity in CO2/CH4 Gas Feeds on Performance of Mixed Matrix Membranes Using Carbon Molecular Sieves. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 221, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Koros, W.J. Effects of Hydrocarbon and Water Impurities on CO2/CH4 Separation Performance of Ester-Crosslinked Hollow Fiber Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 451, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourgues, A.; Sanchez, J. Theoretical Analysis of Concentration Polarization in Membrane Modules for Gas Separation with Feed inside the Hollow-Fibers. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 252, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Mi, Y.; Lock Yue, P.; Chen, G. Theoretical Study on Concentration Polarization in Gas Separation Membrane Processes. J. Membr. Sci. 1999, 153, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ivory, J.; Rajan, V.S.V. Air Separation by Integrally Asymmetric Hollow-Fiber Membranes. AIChE J. 1999, 45, 2142–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, S.K.; Kumar, K.; Upadhyay, R.K. Experimental Investigation of Circular Baffles Pitch and Aperture Ratio on the Concentration Polarization of Pd–Ag Membrane Module for Enhanced Hydrogen Separation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 169, 151136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Castro-Dominguez, B.; Dixon, A.G.; Ma, Y.H. Scalability of Multitube Membrane Modules for Hydrogen Separation: Technical Considerations, Issues and Solutions. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 564, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.; Atallah, C.; Siriwardane, R.; Stevens, R. Technoeconomic Analysis for Hydrogen and Carbon Co-Production via Catalytic Pyrolysis of Methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 20338–20358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, H.J.; Park, D.K.; Ryu, J.-H. Purification of Methane Pyrolysis Gas for Turquoise Hydrogen Production Using Commercial Polymeric Hollow Fiber Membranes. Energies 2026, 19, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010179

Yu HJ, Park DK, Ryu J-H. Purification of Methane Pyrolysis Gas for Turquoise Hydrogen Production Using Commercial Polymeric Hollow Fiber Membranes. Energies. 2026; 19(1):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010179

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Hyun Jung, Dong Kyoo Park, and Jae-Hong Ryu. 2026. "Purification of Methane Pyrolysis Gas for Turquoise Hydrogen Production Using Commercial Polymeric Hollow Fiber Membranes" Energies 19, no. 1: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010179

APA StyleYu, H. J., Park, D. K., & Ryu, J.-H. (2026). Purification of Methane Pyrolysis Gas for Turquoise Hydrogen Production Using Commercial Polymeric Hollow Fiber Membranes. Energies, 19(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010179