Displacement Experiment Characterization and Microscale Analysis of Anisotropic Relative Permeability Curves in Sandstone Reservoirs

Abstract

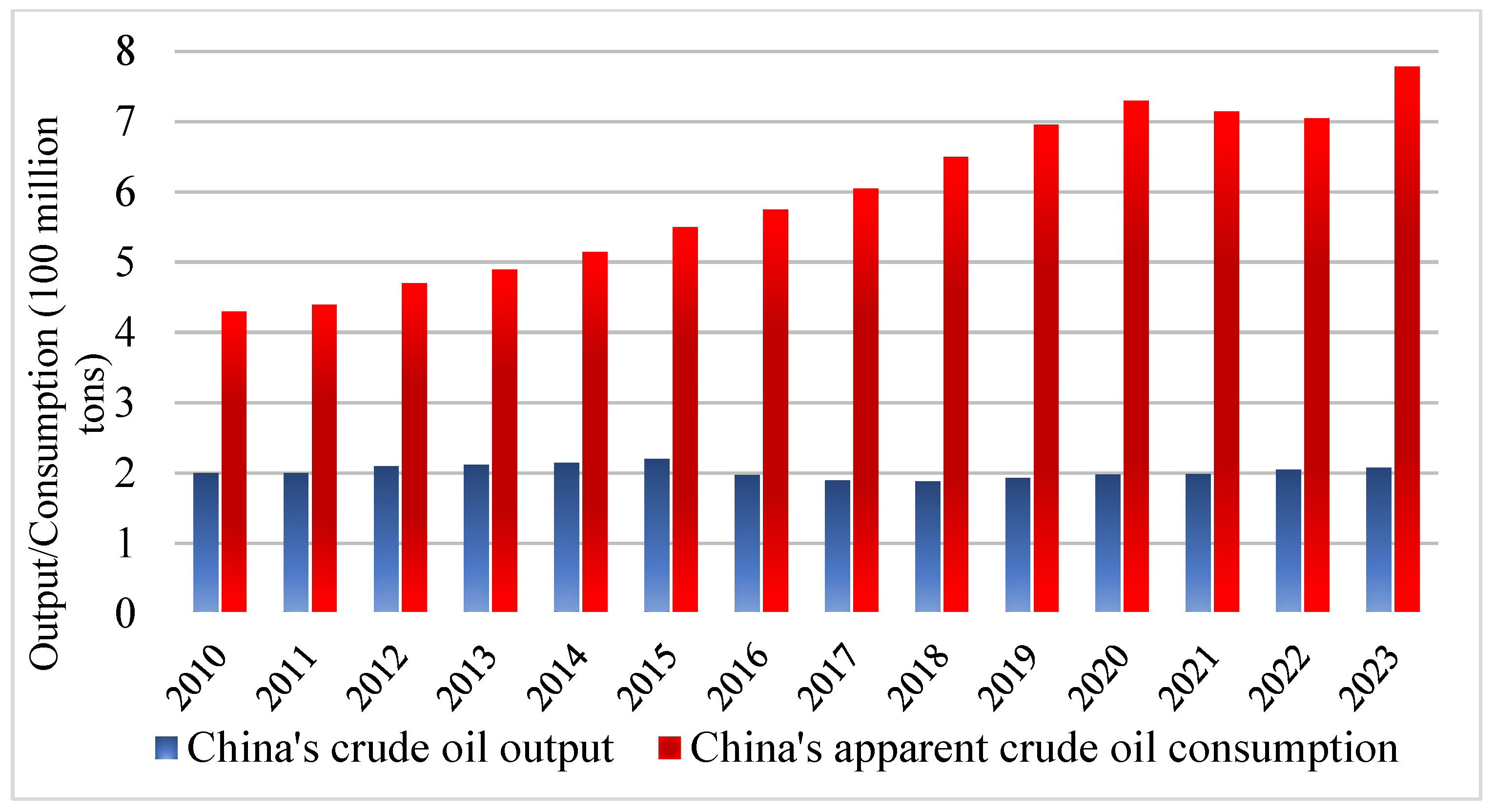

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Investigation of the Mechanisms Underlying Anisotropic Relative Permeability Curves

2.1. Experimental Design

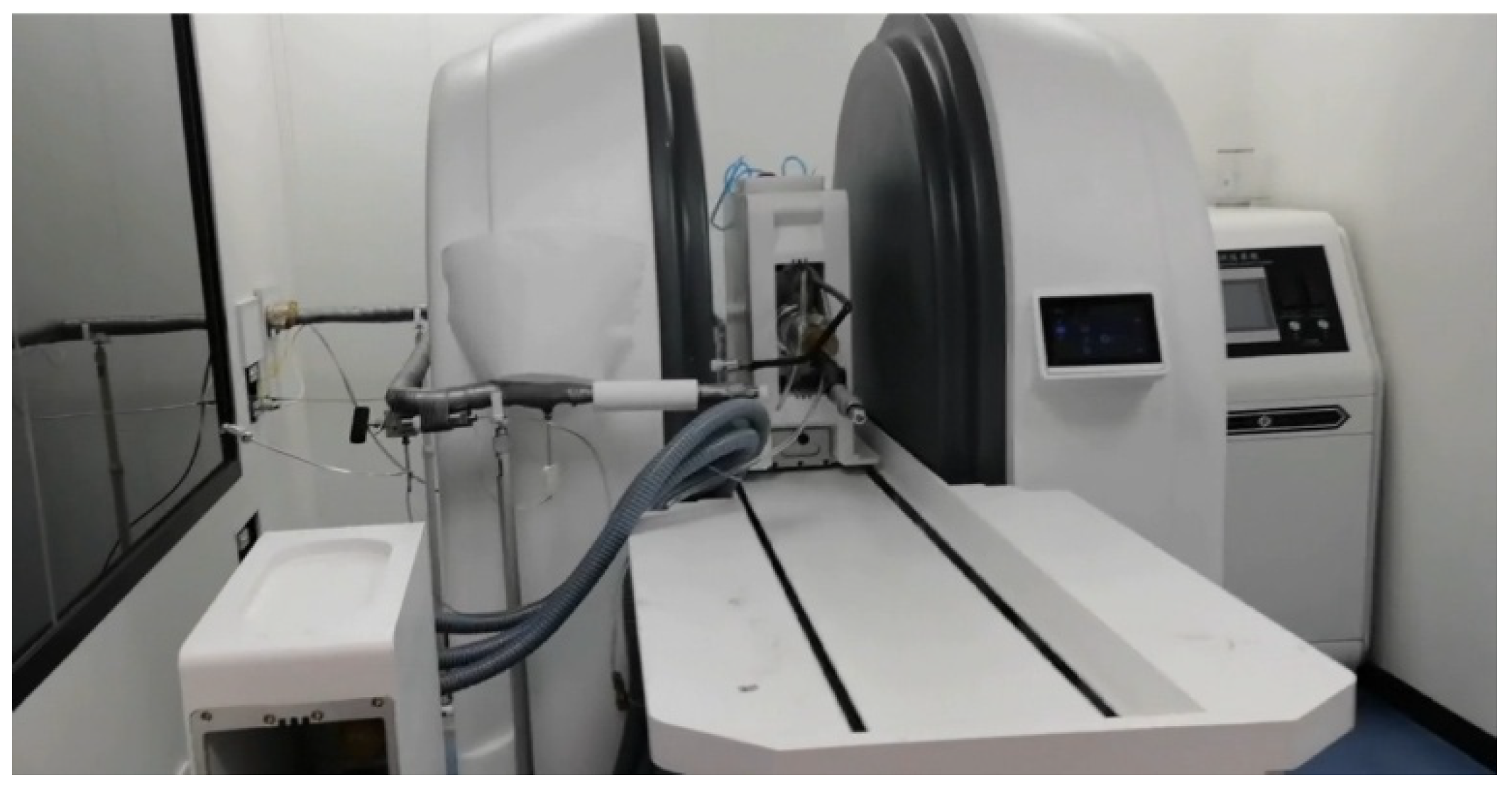

2.1.1. Equipment and Experimental Samples

2.1.2. Experimental Procedures

- (1)

- Core Displacement Experiments:

- (1).

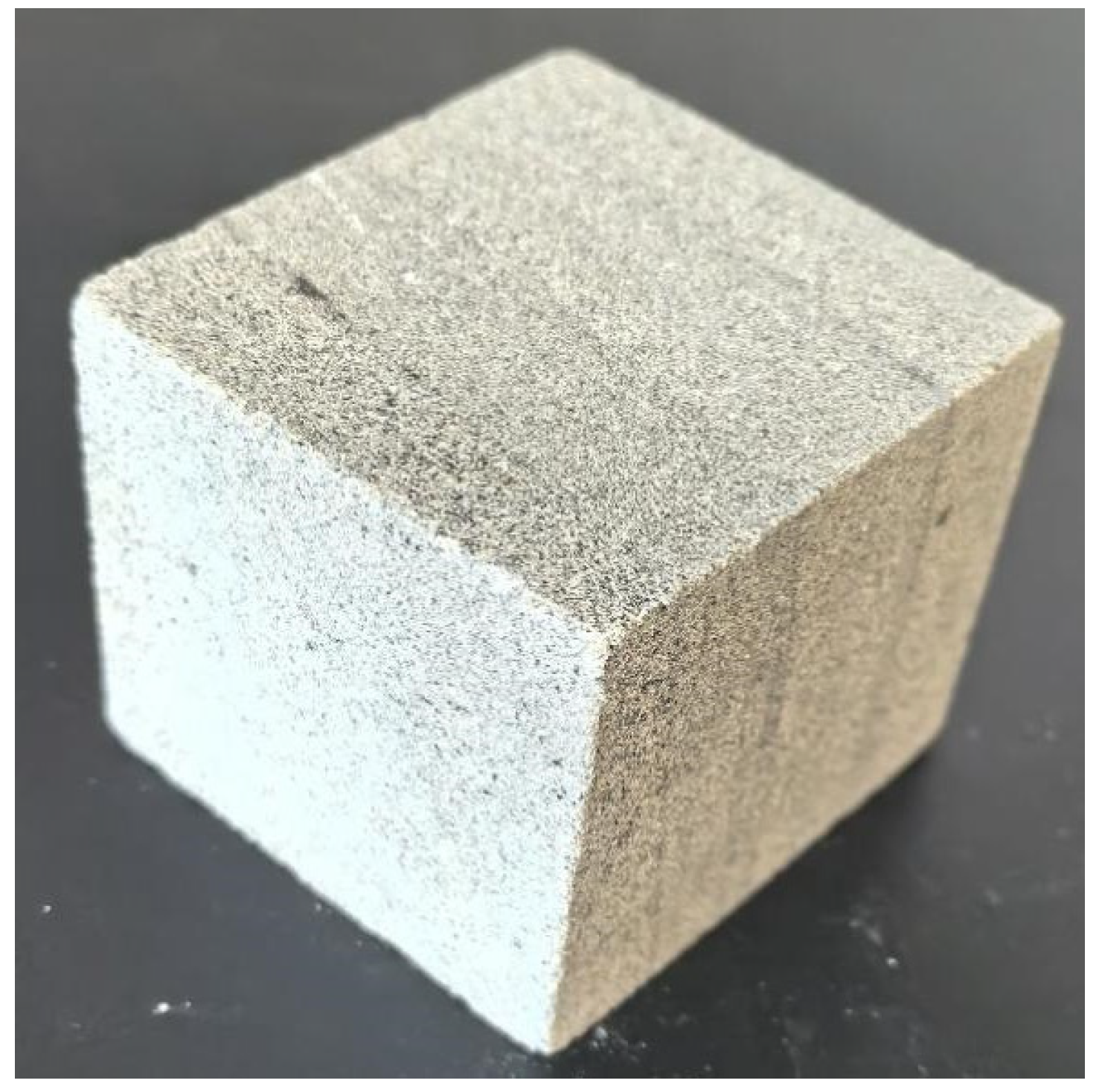

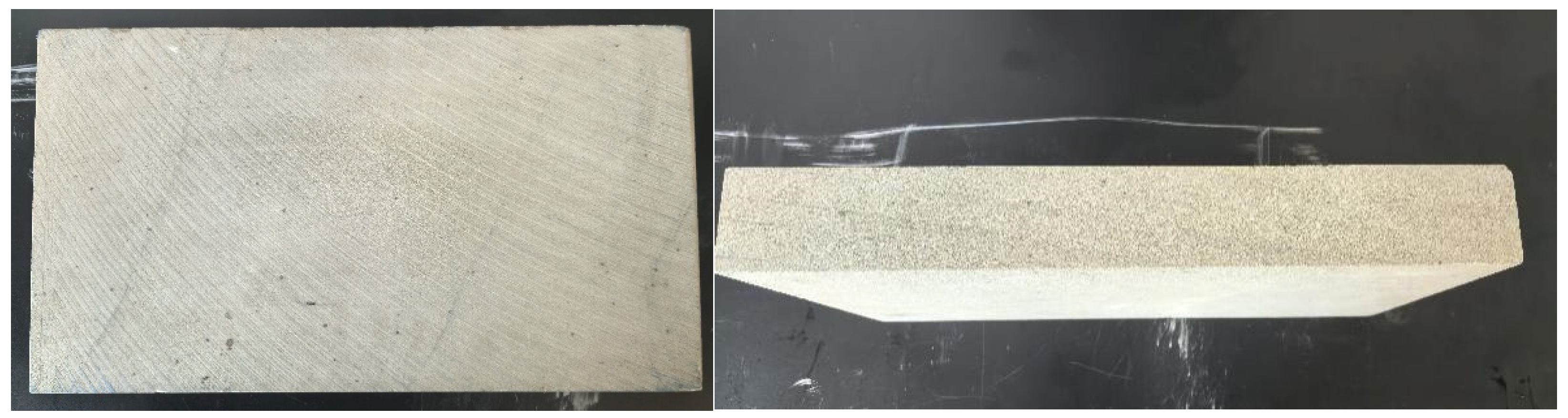

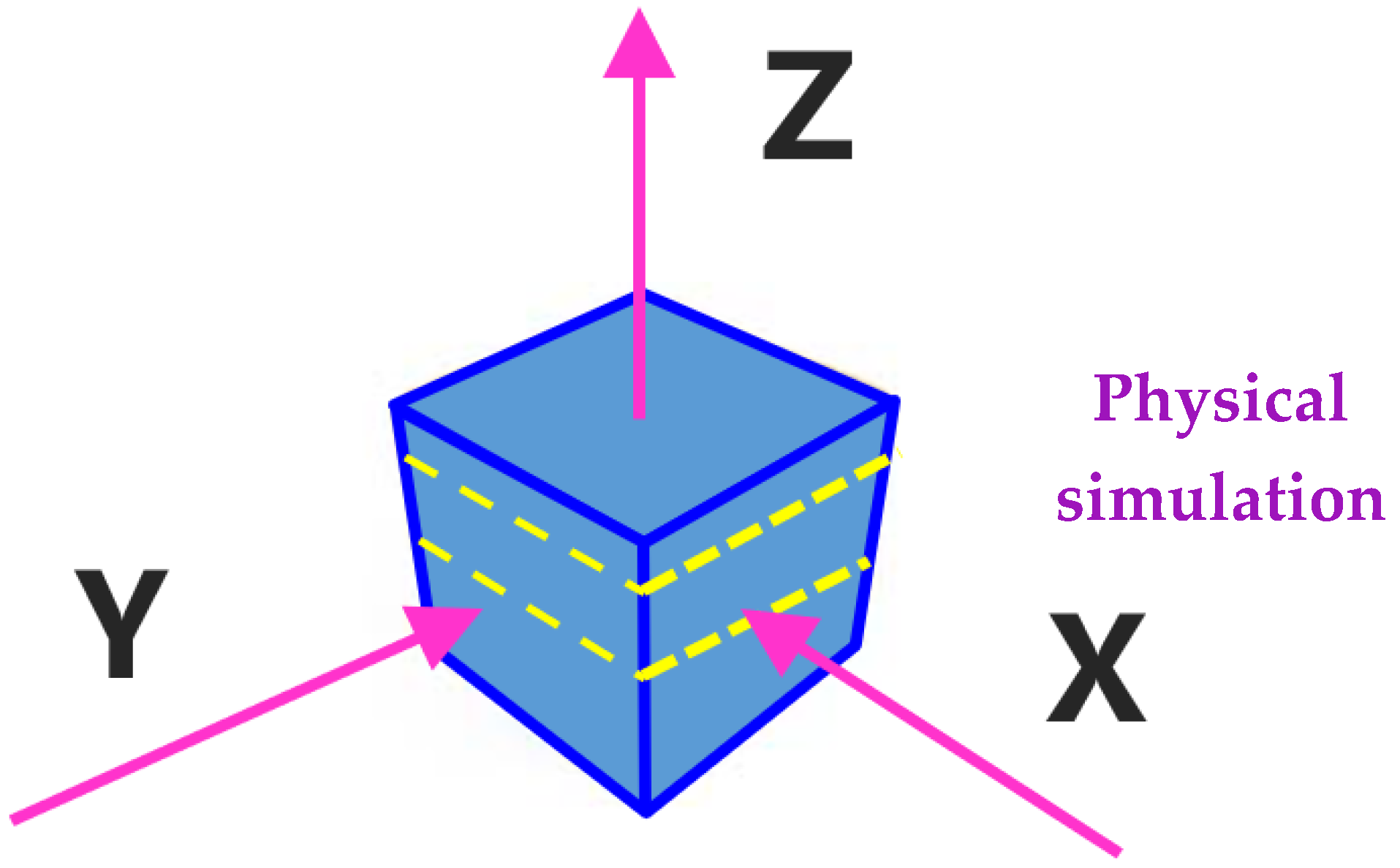

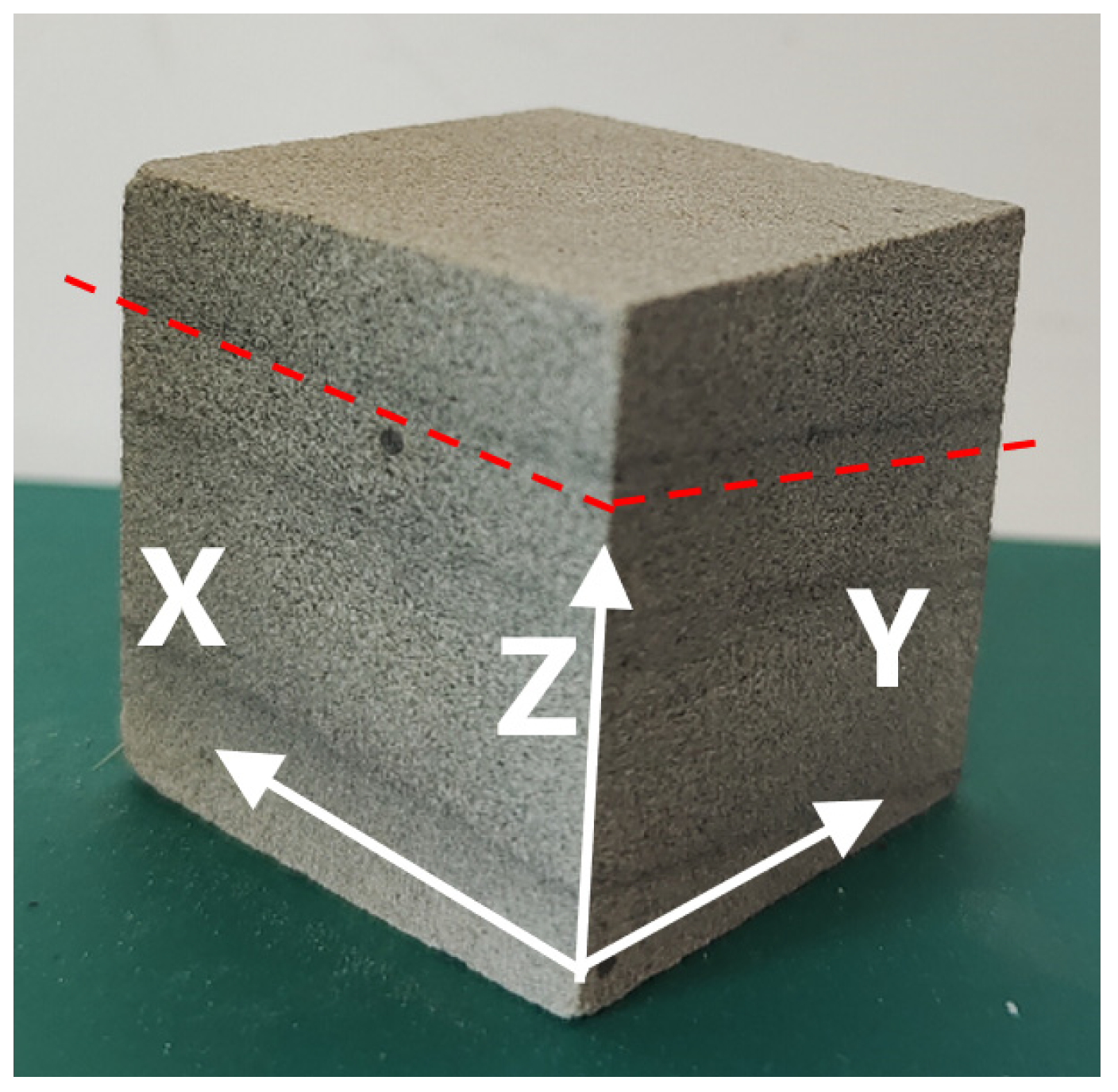

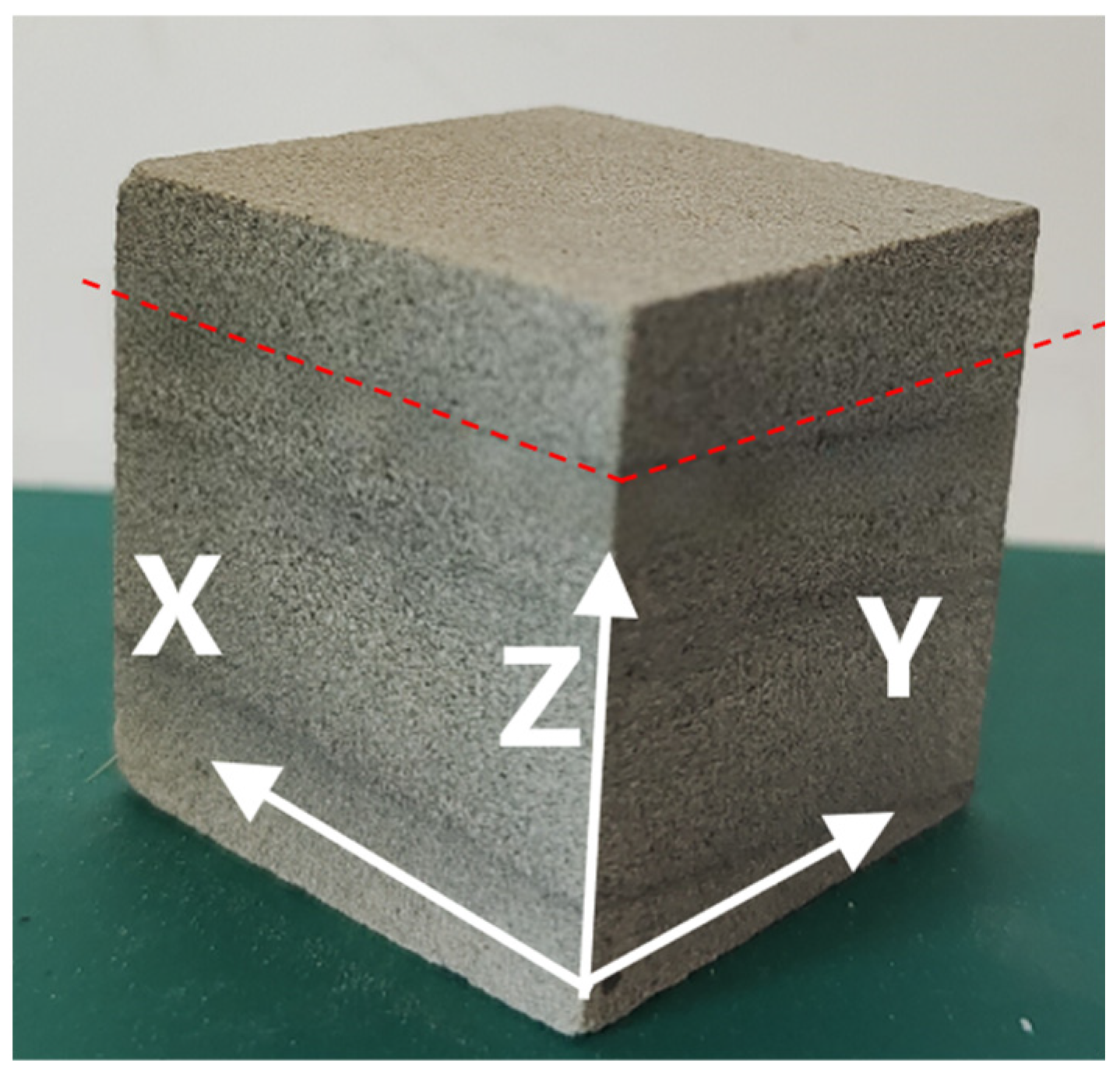

- Core Preparation and Dry-State Characterization: Outcrop rock samples were cut into 5 × 5 × 5 cm cubic cores using wire cutting. The cores were cleaned to remove oil, water, salts, and soil impurities, then oven-dried and weighed. Bulk porosity was measured, and absolute permeability in the x, y, and z directions was determined in the dry state.

- (2).

- Water Saturation and Liquid-Phase Permeability Testing: The cleaned cores were placed in rubber sleeves and fully saturated with formation water. Liquid-phase permeability in the x, y, and z directions was measured, and differences among directions were recorded to preliminarily assess anisotropy.

- (3).

- Oil Displacement to Irreducible Water Saturation: Simulated crude oil was injected into the cores to displace water until irreducible water saturation (Swi) was reached. Outlet flow rates and time were recorded. The termination criterion was an outlet water cut below 0.1% and an injected pore volume (PV) greater than 30 PV. Under Swi conditions, effective oil-phase permeability was measured in x, y, and z directions. NMR and CT scans were performed to analyze pore structure and fluid distribution at Swi.

- (4).

- Directional Waterflooding Experiments: For each direction (x, y, z), water was injected at a constant rate for 30 PV. Outlet flow rates and times were recorded. The experiment was stopped when water cut exceeded 99.9% and injected PV exceeded 30, achieving residual oil saturation (Sor). Effective water-phase permeability was measured in all directions. NMR and CT scans were performed to analyze fluid distribution and pore changes at Sor. By adjusting the inlet and outlet of the core holder, the tests were sequentially completed for all three directions.

- (5).

- Data Analysis and Final Results: The cores were cleaned, oven-dried, and weighed again to verify mass changes. Based on the experimental data (flow rate, time, permeability, etc.), relative permeability curves for x, y, and z directions were calculated, and anisotropic characteristics were analyzed.

- (2)

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Scanning:

- (1).

- Power on the NMR instrument, set the magnet control temperature, activate the condensation system, and preheat the instrument for at least 16 h.

- (2).

- Select pulse sequences to calibrate the scanning space and set scanning parameters.

- (3).

- Place the core in the NMR-specific PIC (Pressure Isolated Core holder) holder and position it at the center of the measurement chamber.

- (4).

- Select the pulse sequence, configure parameters, and start measurements.

- (5).

- Measurement parameters include echo spacing, full relaxation time, NECH (NMR Effective Porosity), NS (Number of Spins), RG (Relaxation Gradient), and others.

- (3)

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scanning:

- (1).

- Place the core sample into the Nano Voxel 5000 micro-CT system and adjust scanning parameters.

- (2).

- Reconstruct the scanned data into a digital 3D model using Phoenix Datosx 2 Acq X (v2.6) software. During reconstruction, geometric calibration values can be adjusted to reduce beam hardening artifacts.

- (3).

- Analyze the reconstructed 3D digital model using VOLUME GRAPHICS STUDIO MAX 2024.2 and AVIZO 9.0. Generate internal 3D visualizations and extract oil distribution within the core pores, with final images provided.

2.2. Relative Permeability Calculation Methods

2.2.1. JBN Calculation Method

- (1).

- Capillary pressure and gravity effects are neglected.

- (2).

- The two immiscible fluids are incompressible.

- (3).

- Oil and water saturations are uniform across any cross-section of the core.

- Relationship among the total two-phase resistance to flow Ω, the ratio of single-phase resistances, the apparent viscosity μapp, and the injection multiple Qi. Based on the above fundamental equations, and according to the equation of motion for two-phase flow:

- 2.

- Relationship among the average water saturation , the outlet water saturation SwL, and the injection multiple Qi.

- Method for calculating oil–water relative permeability.

- q—water injection rate

- μ—fluid viscosity

- ϕ—porosity

- fw—water fractional flow

- fwL—water fractional flow at the outlet end

- foL—oil fractional flow at the outlet end

- Sw—water saturation

- So—oil saturation

- SwL—water saturation at the outlet end

- V—cumulative liquid production

- Vo—cumulative oil production

- Vp—pore volume

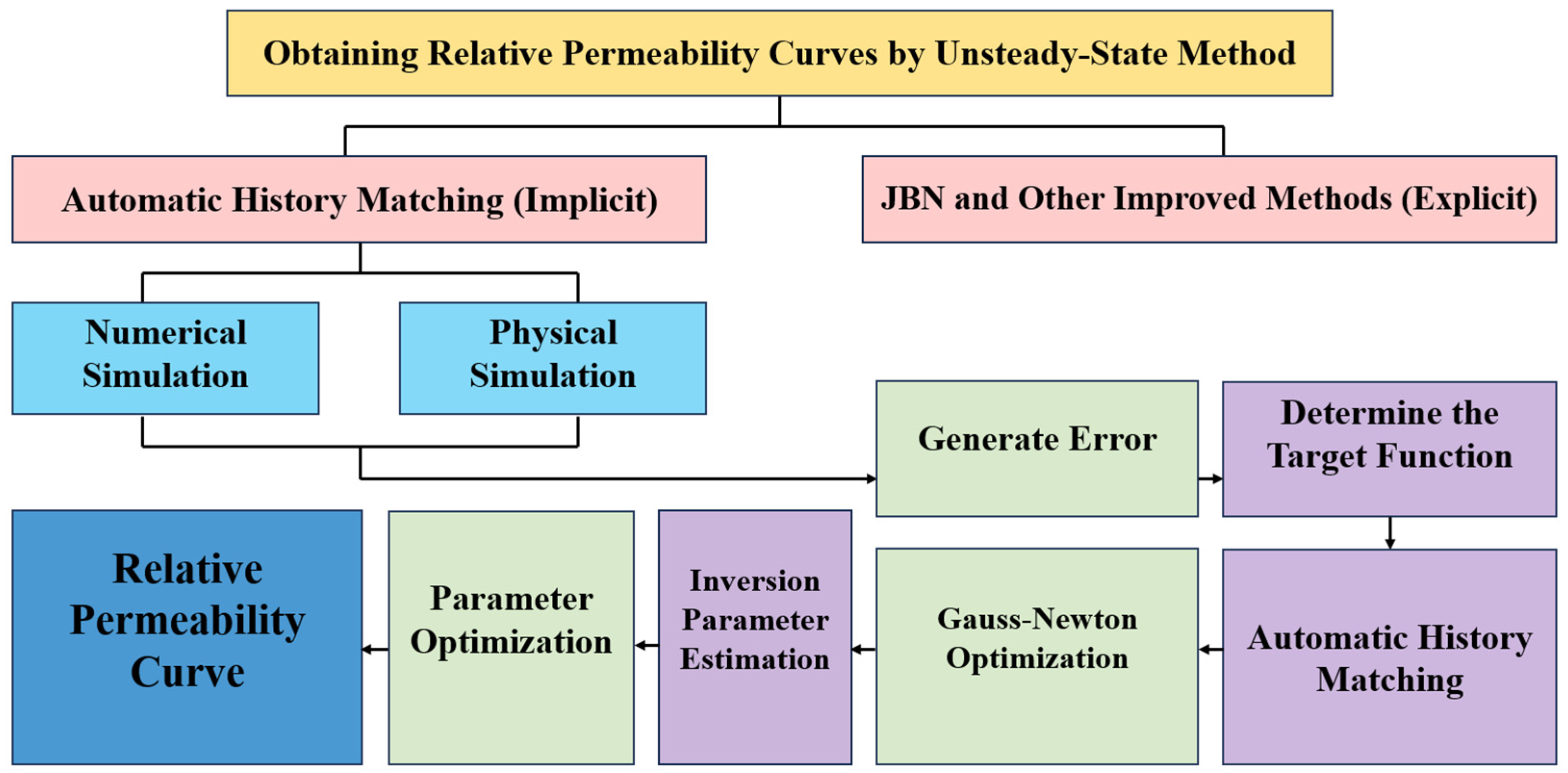

2.2.2. Relative Permeability Calculation Method Based on Automatic History Matching (AHM)

- (1).

- Parameter Initialization: Determine the required physical displacement experimental data.

- (2).

- Model Setup: Build a numerical model based on the physical core experiment.

- (3).

- Objective Function Definition: Compare simulated results with experimental data and calculate errors using appropriate formulas; this serves as the objective function.

- (4).

- Optimization Adjustment: Adjust the relative permeability model parameters according to the objective function using an optimization algorithm.

- (5).

- Iteration: Repeat the process until the error is below the preset threshold or no longer significantly decreases, indicating convergence and yielding a highly accurate fitted relative permeability curve.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Displacement Experiment Analysis

3.1.1. Laminated Cross-Bedded Core

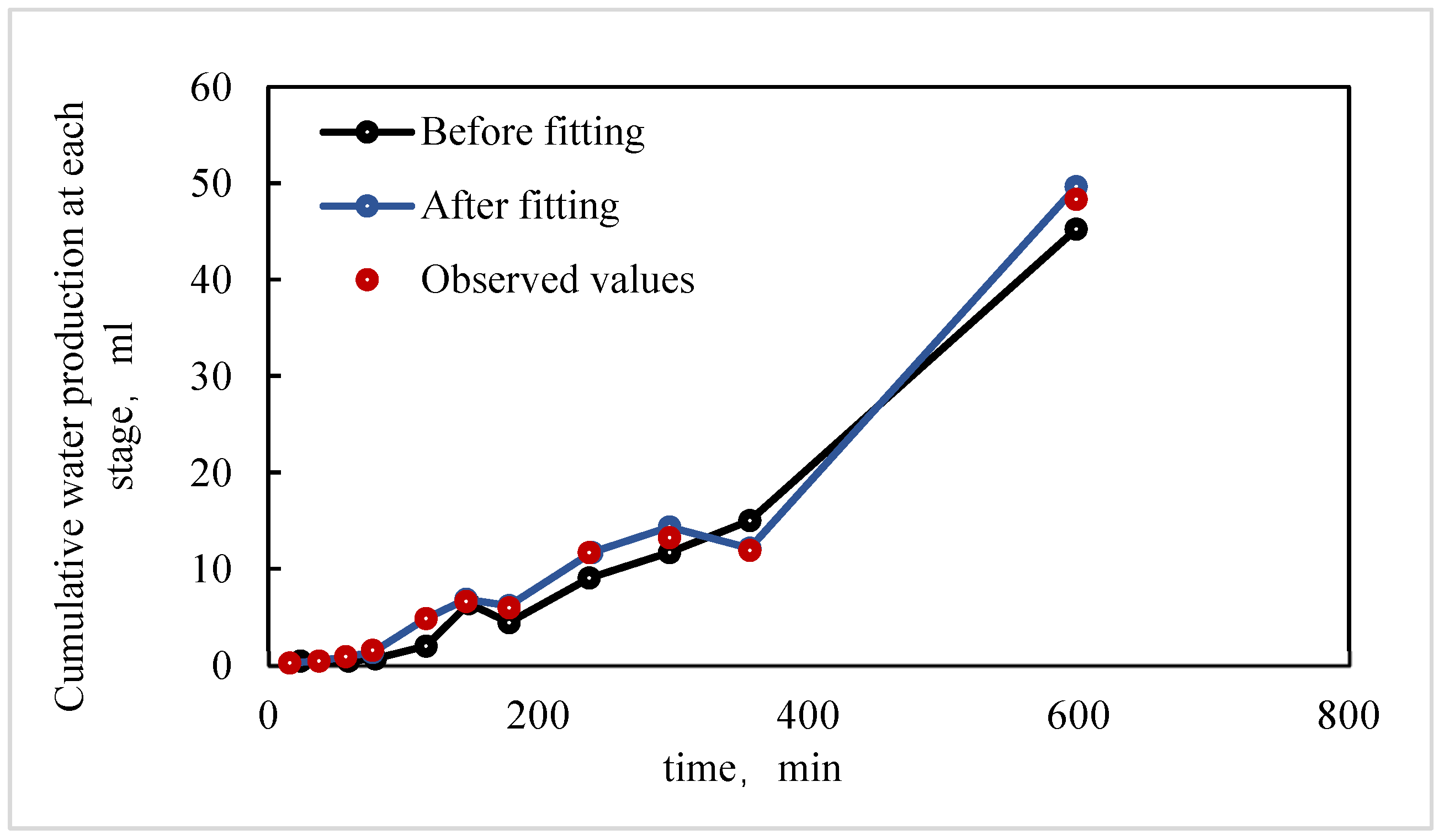

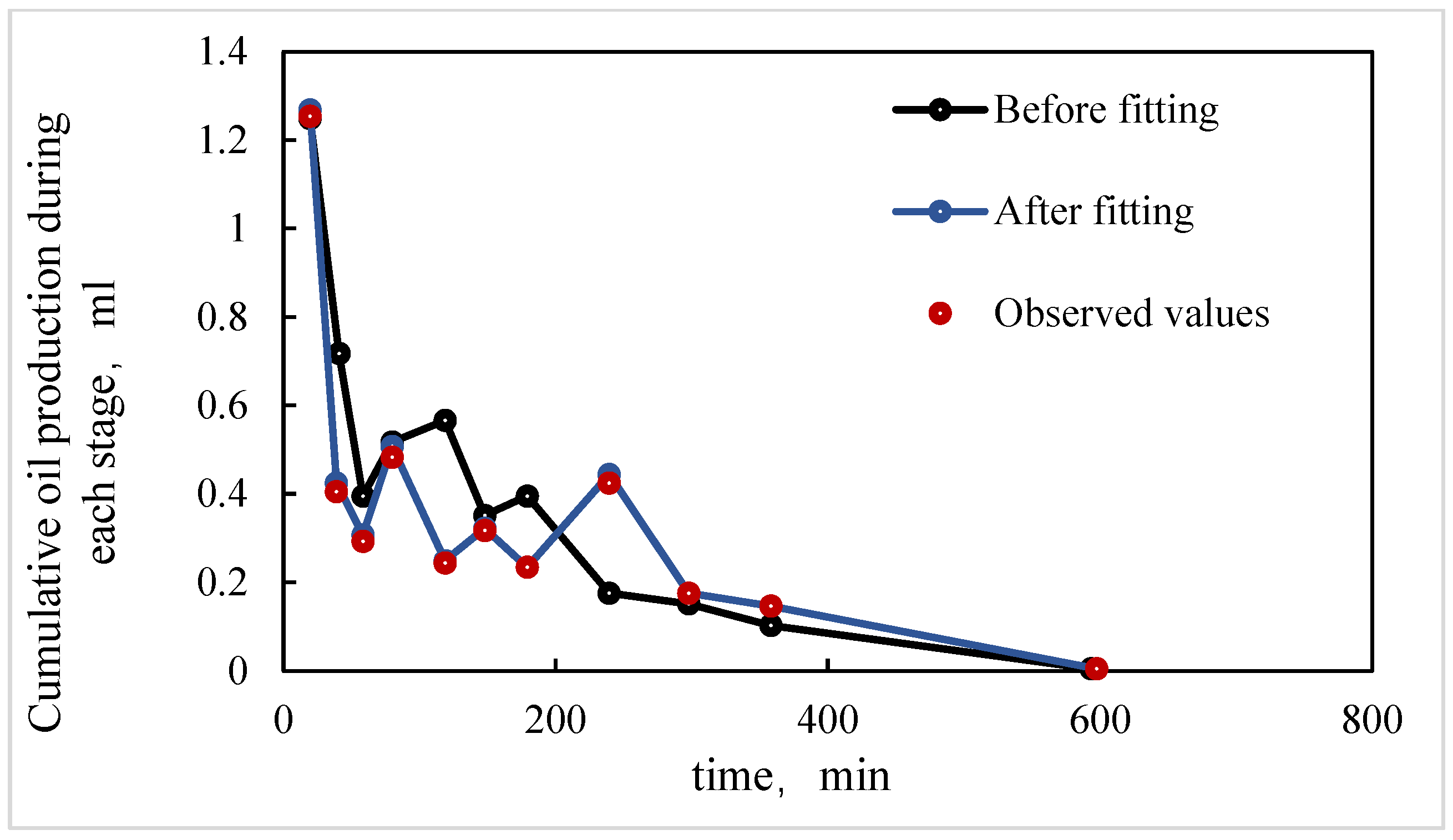

- (1)

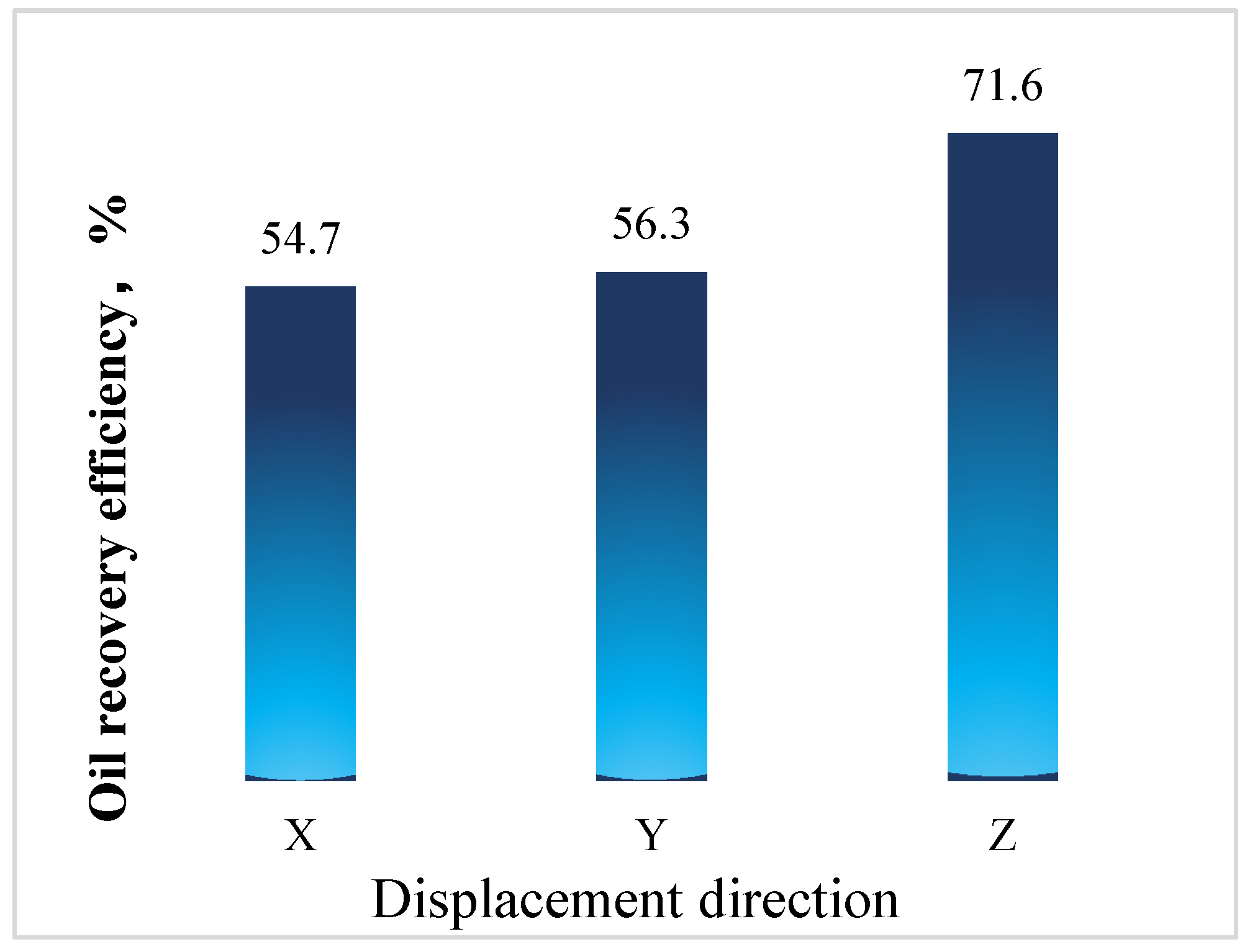

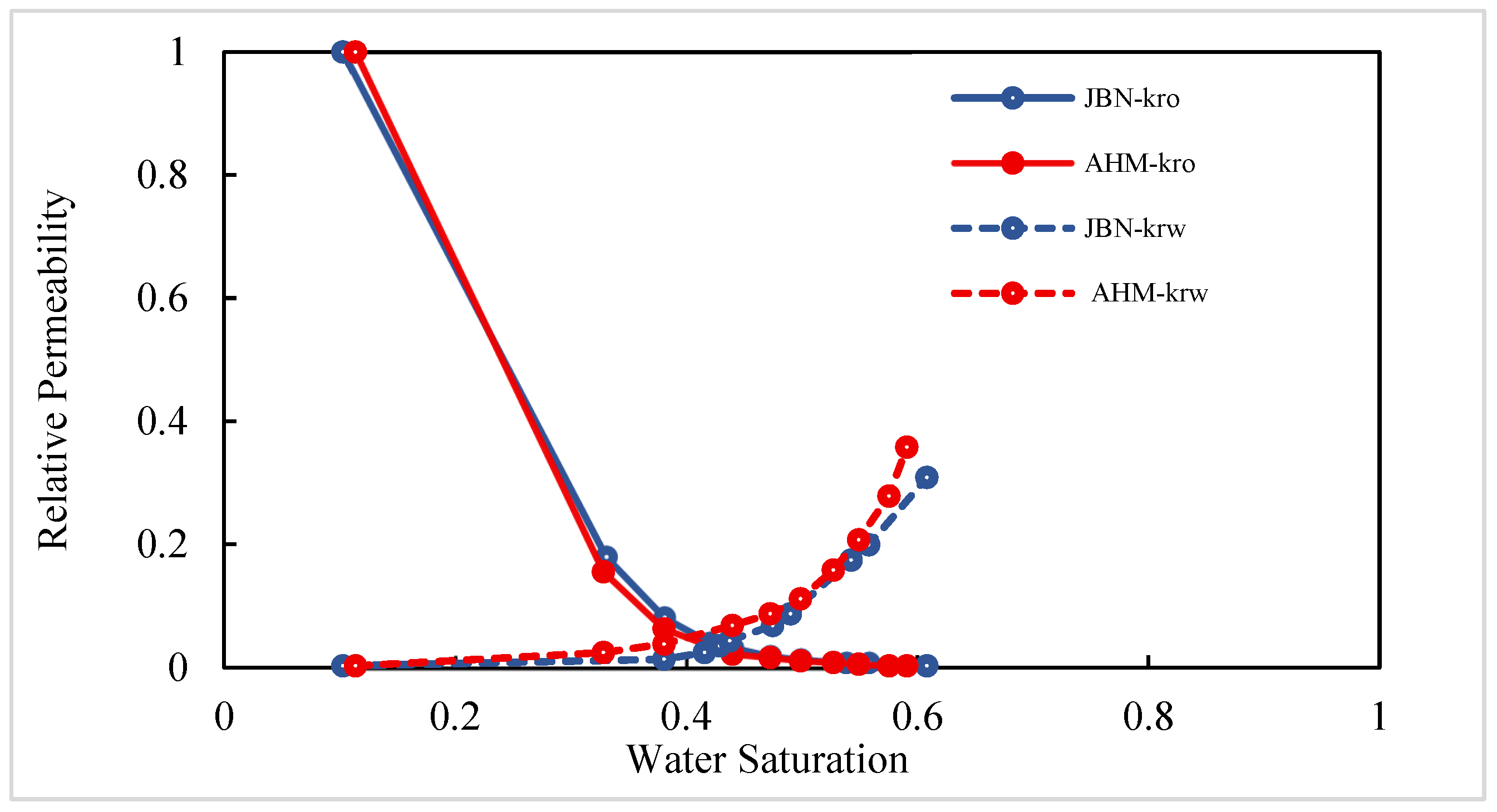

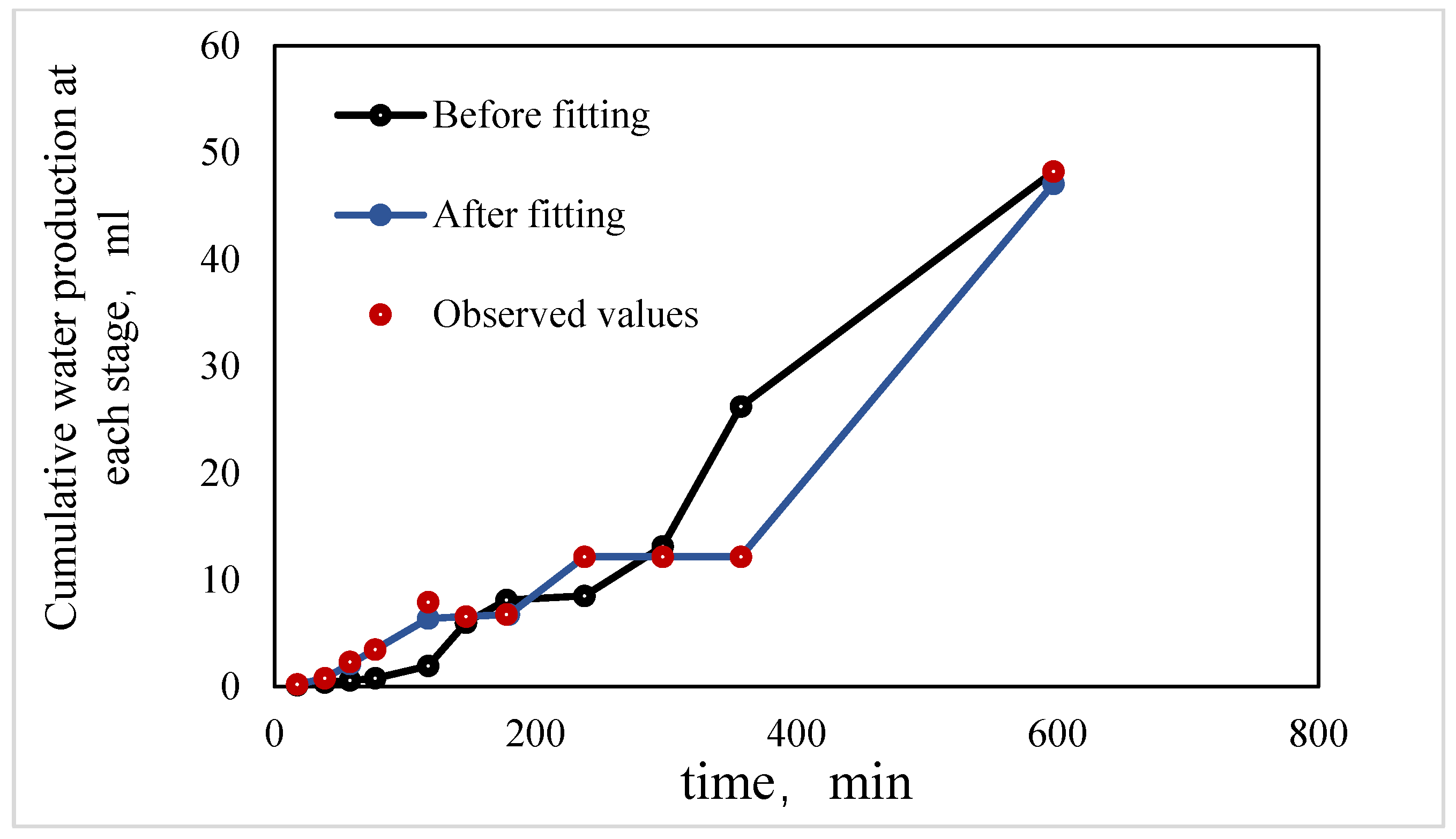

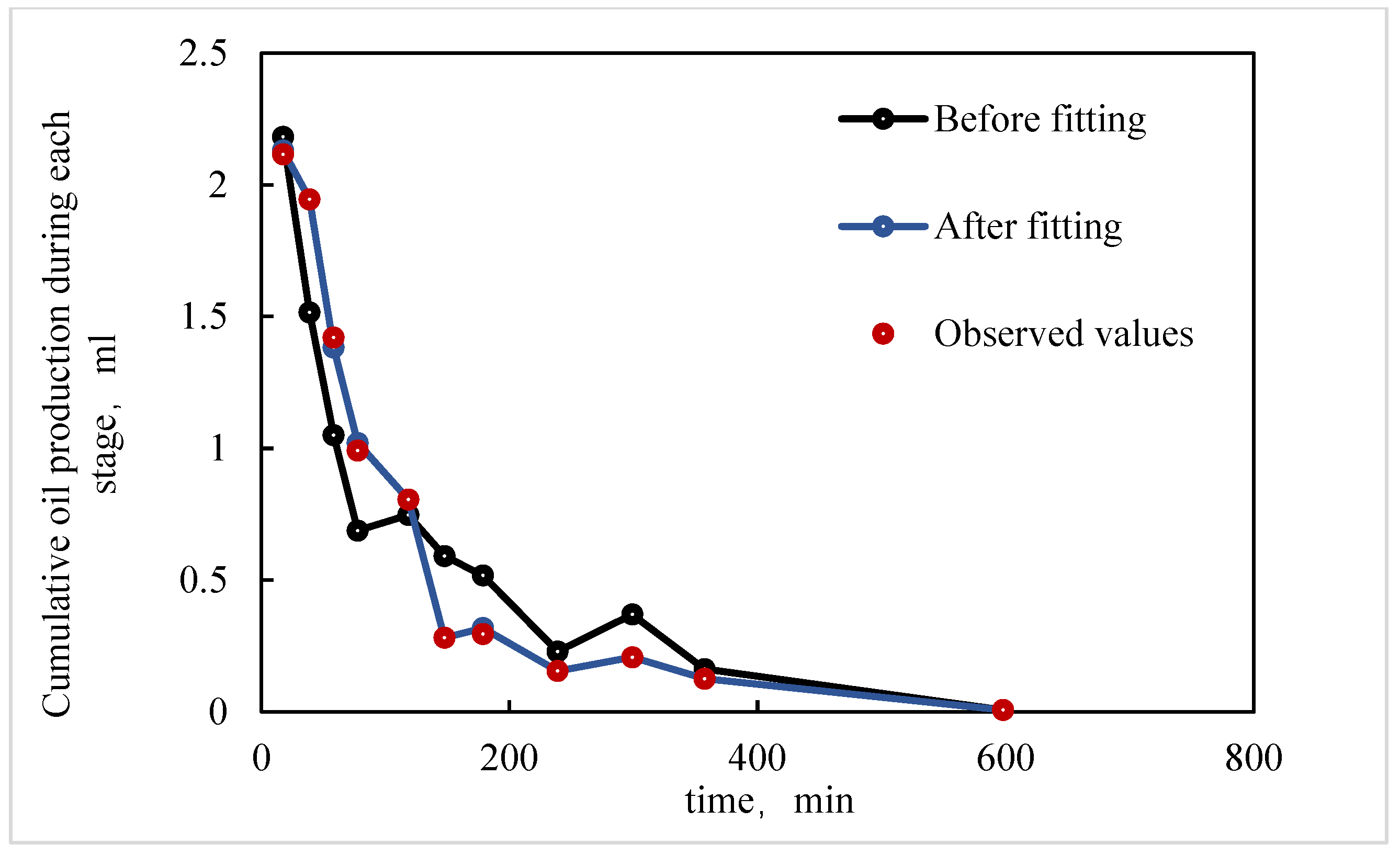

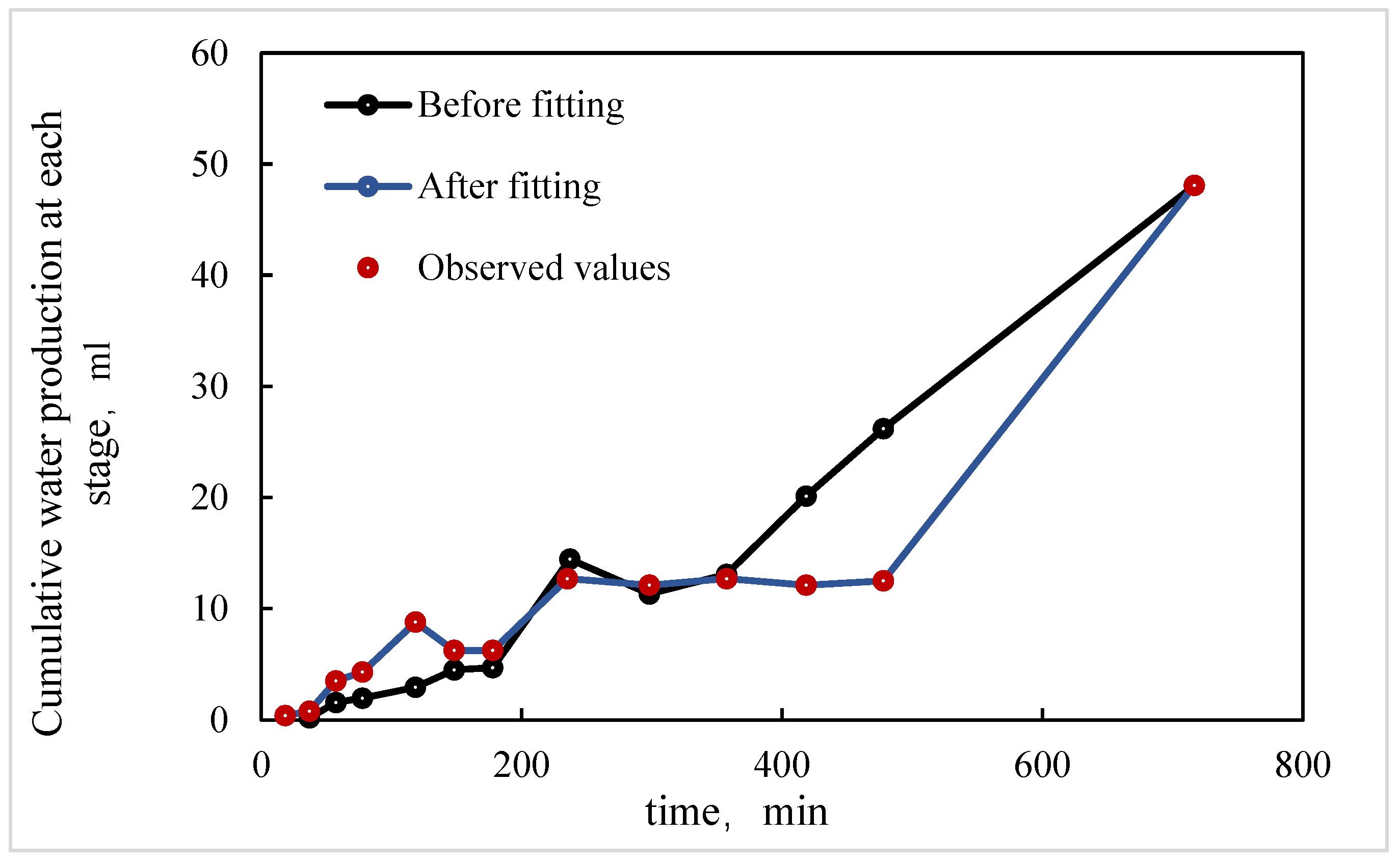

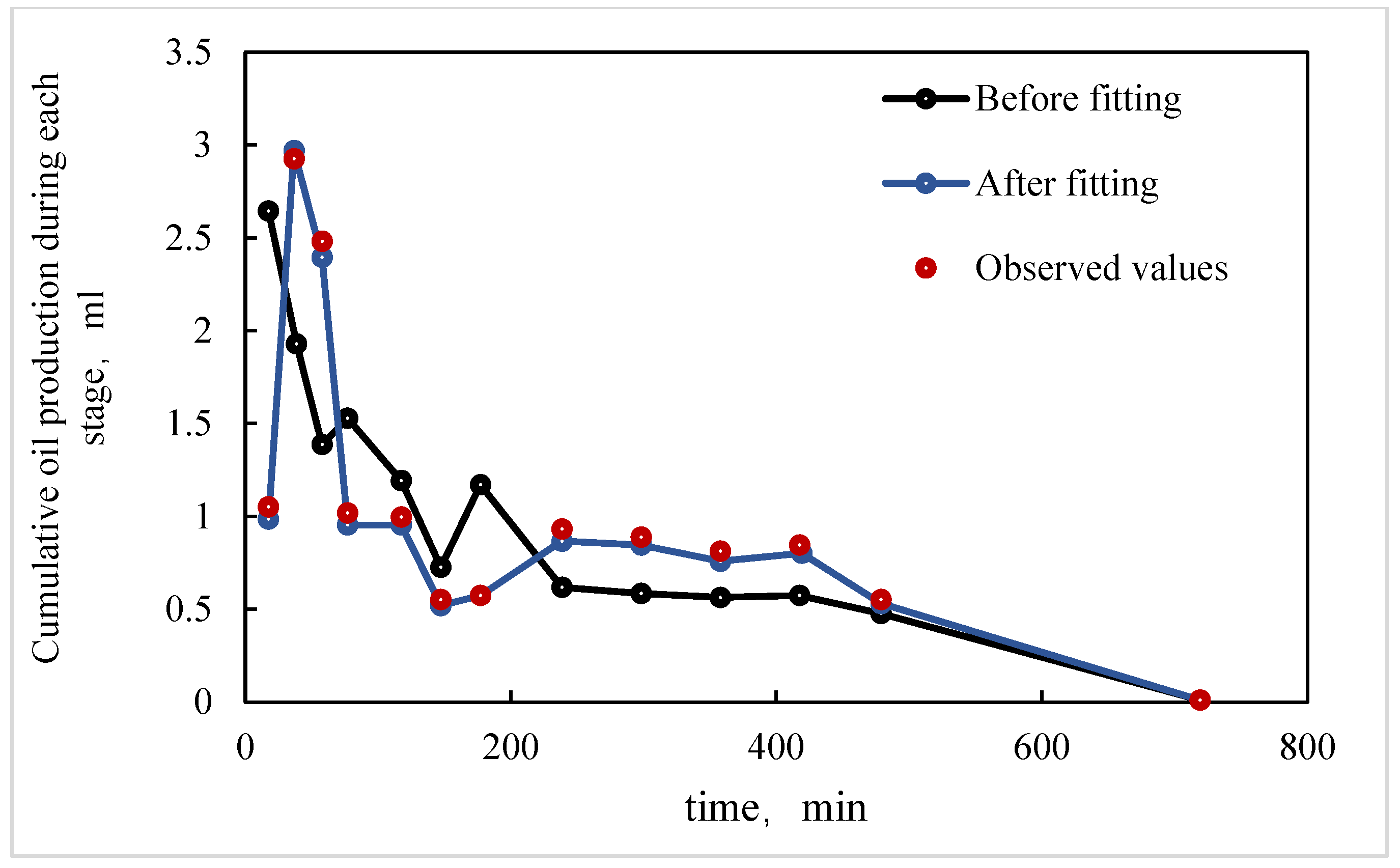

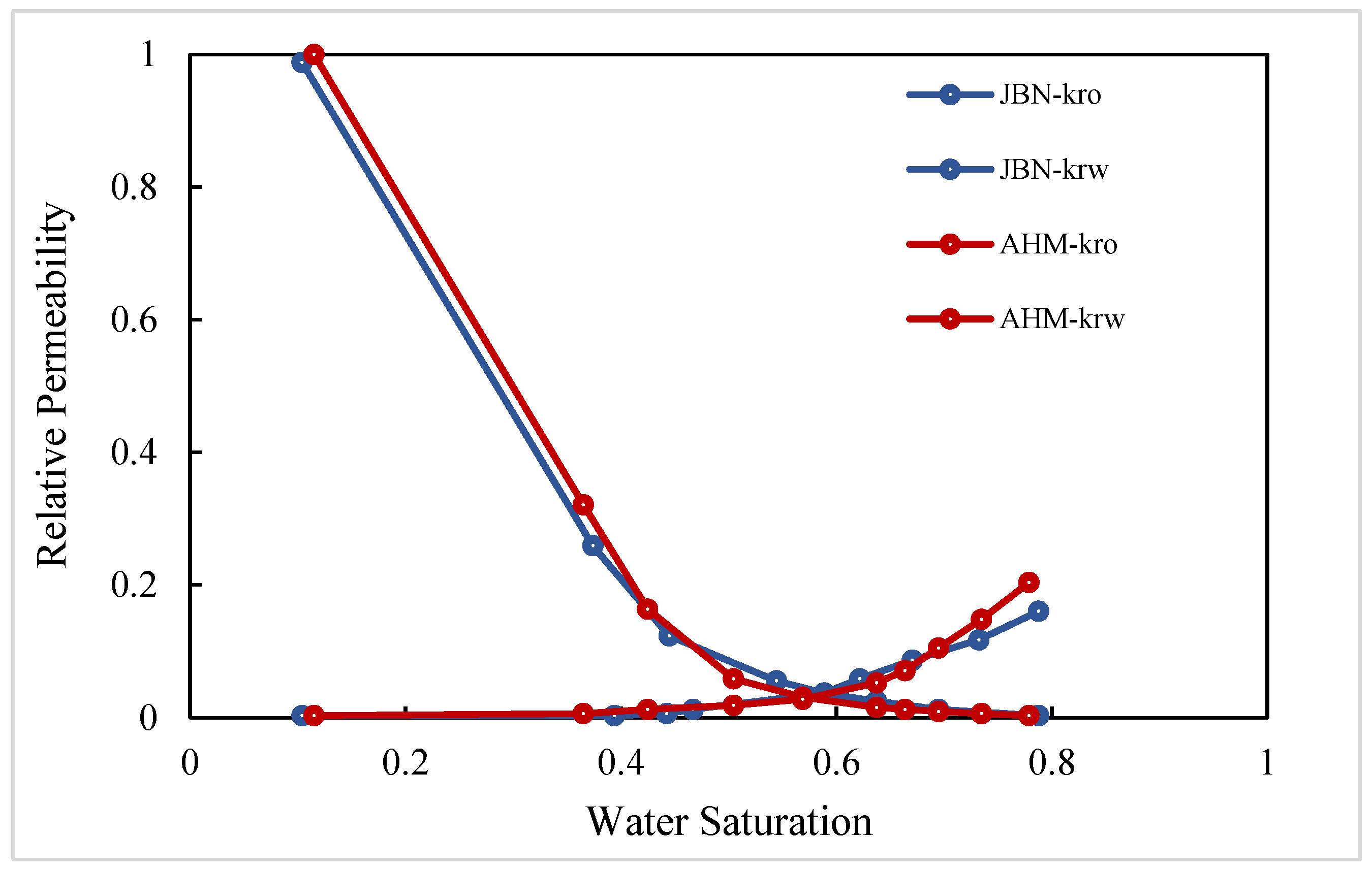

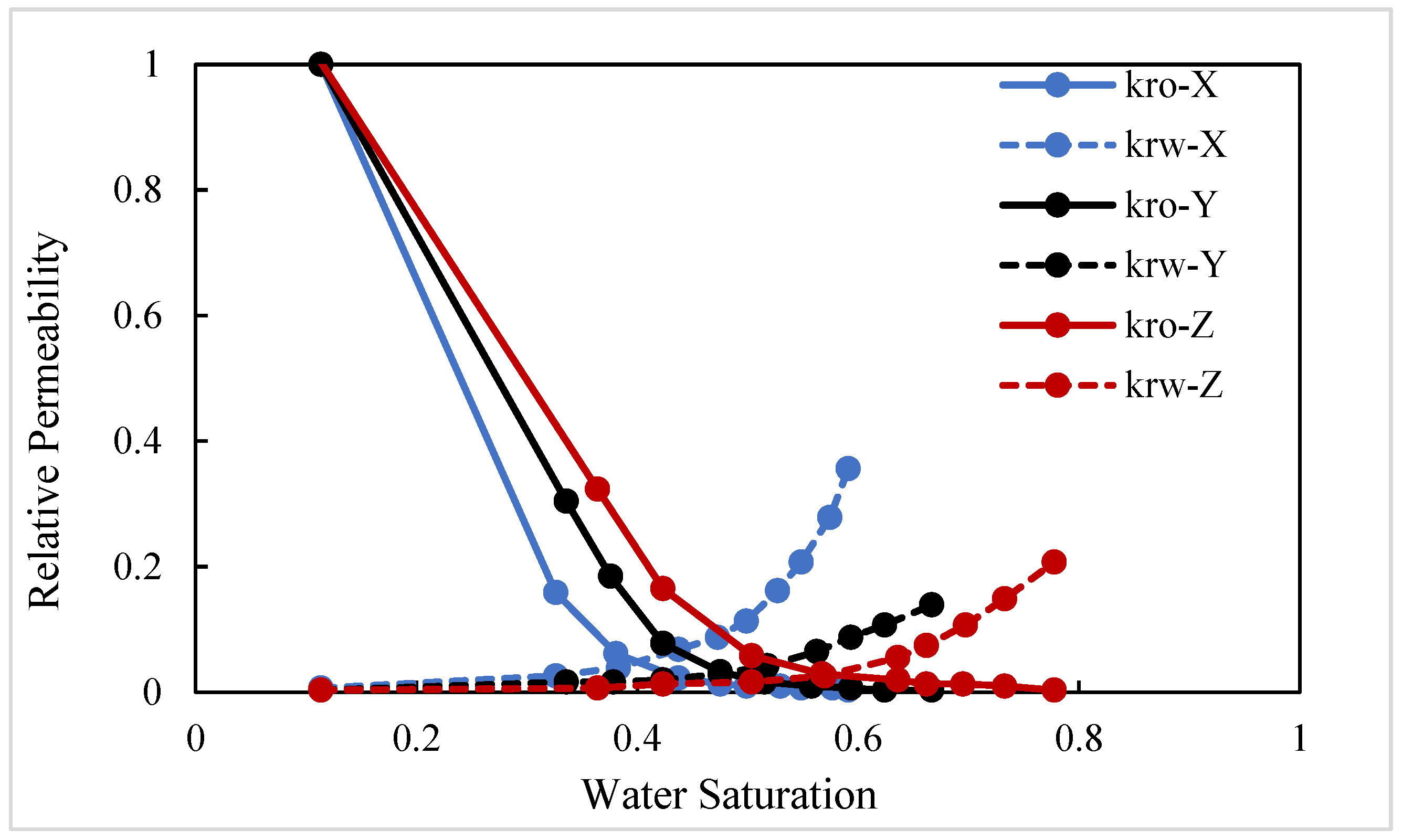

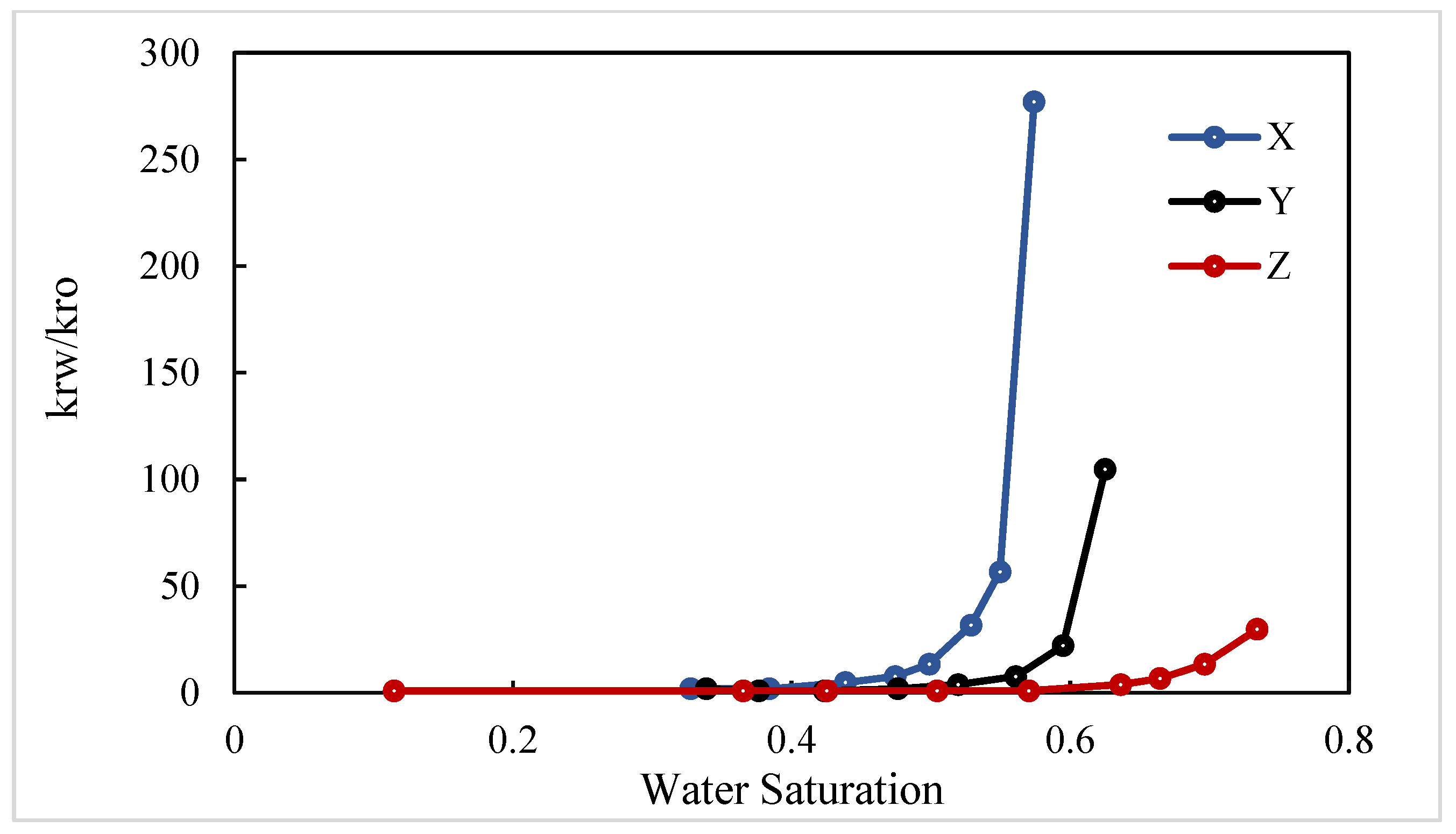

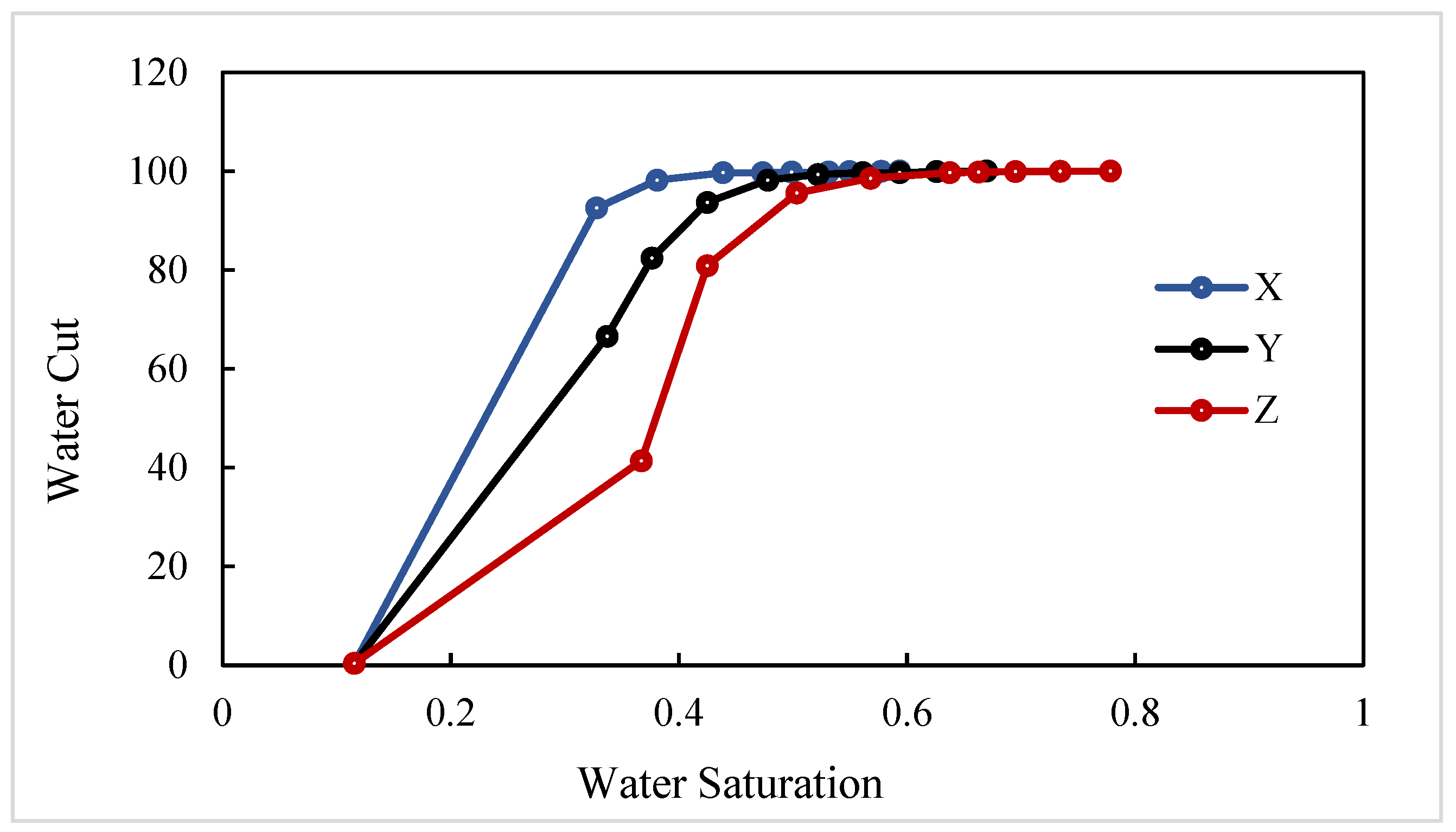

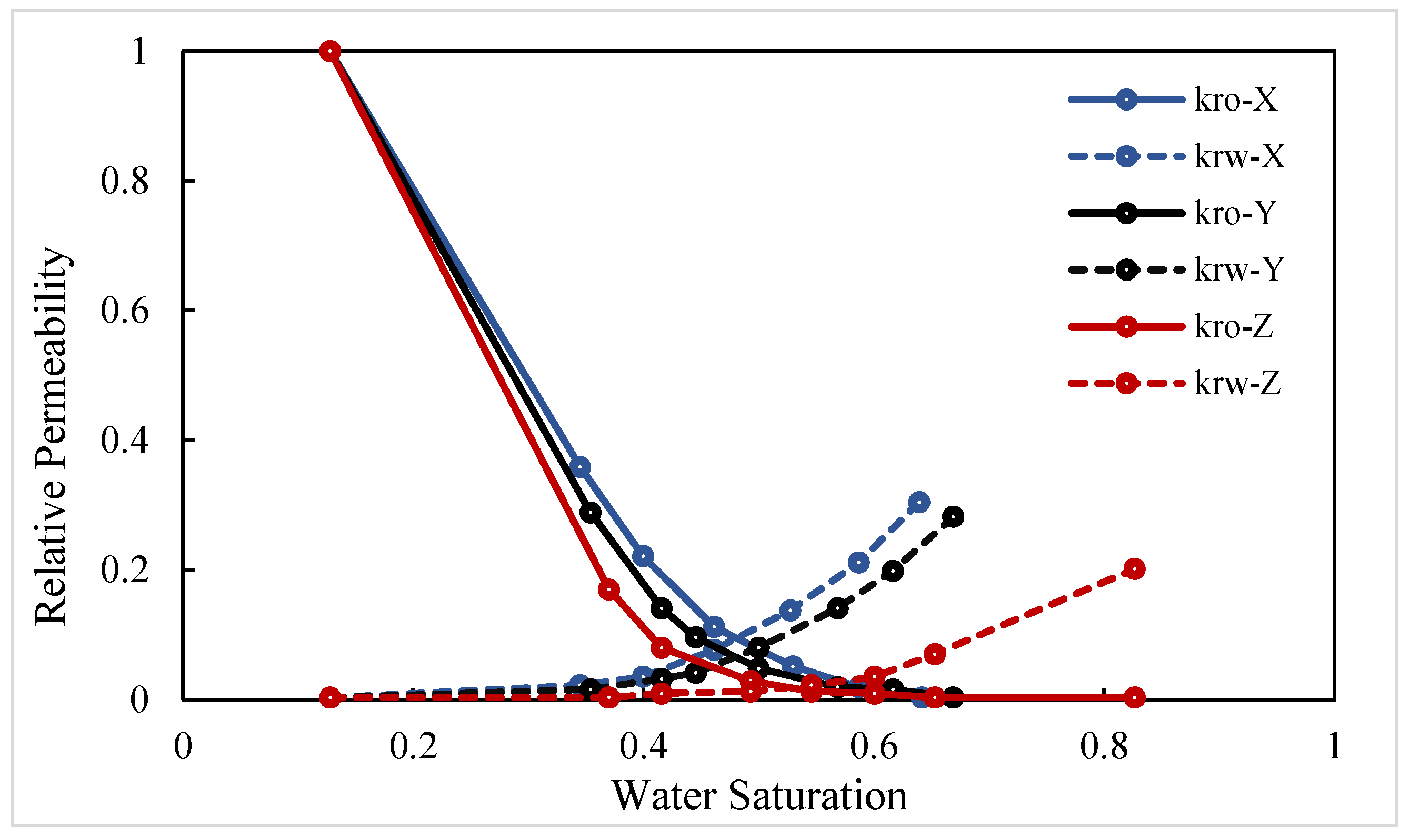

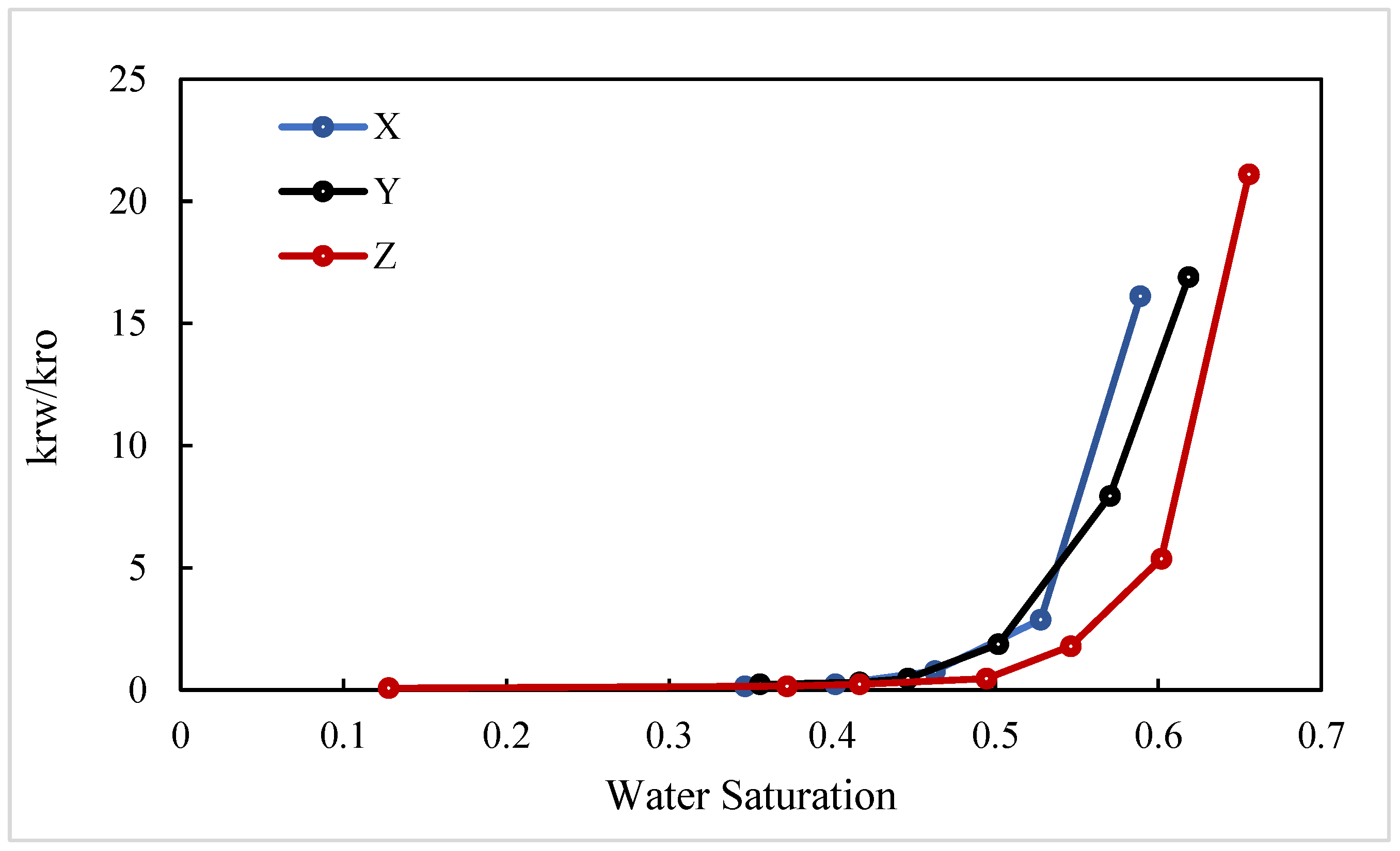

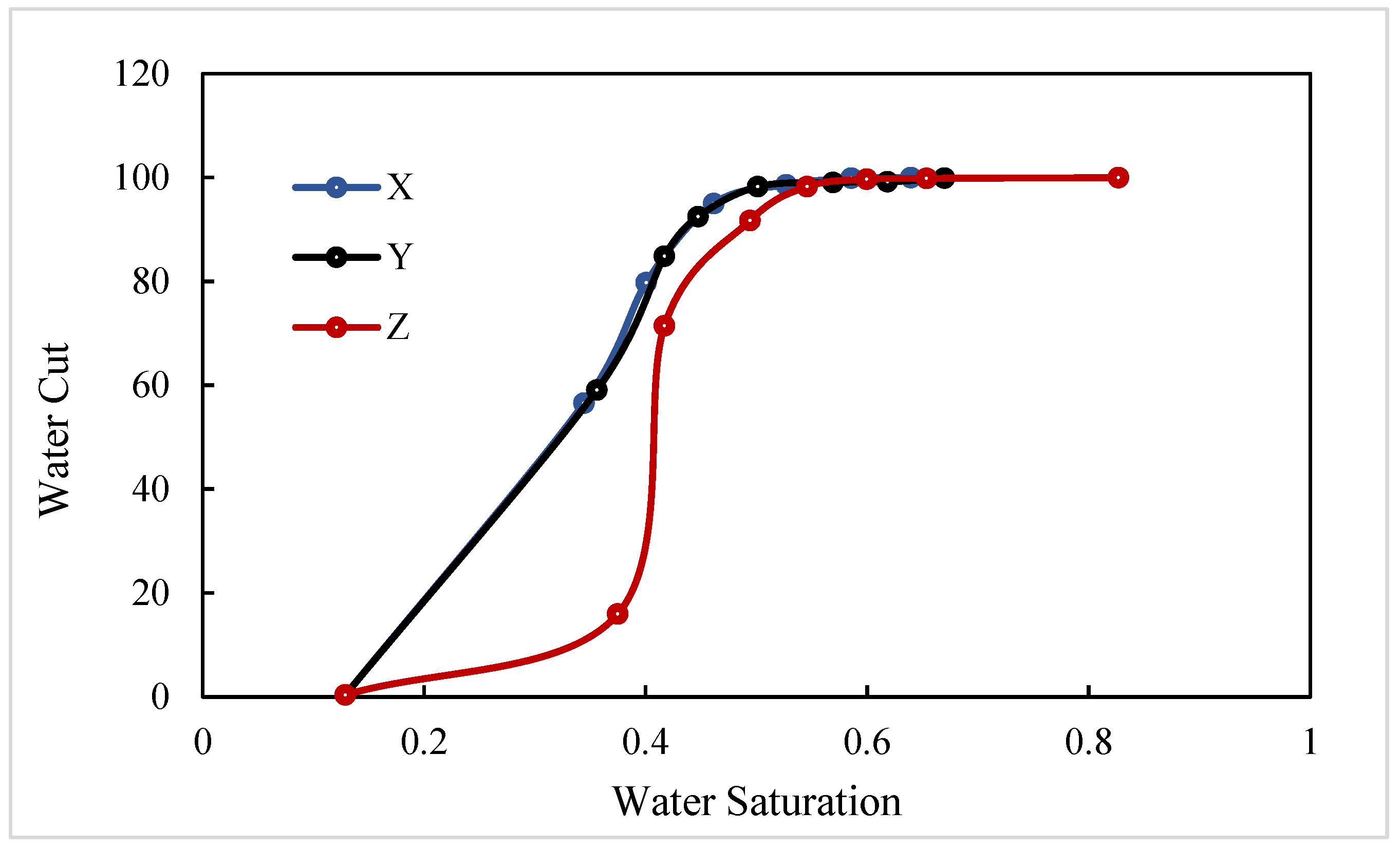

- In the X direction, fluids flow parallel to the bedding planes, following relatively straight flow paths. With crude oil viscosity of 75 mPa·s, the waterflooding experiment shows a low connate water saturation of approximately 10% and a relatively high residual oil saturation of 40.6%. The endpoints of the relative permeability curves obtained using the JBN and AHM methods are consistent, yet notable differences appear in the co-permeability regions, reflecting the distinct capabilities of the two methods in capturing fluid–fluid interactions. Figure 9 and Figure 10 present comparative analyses of the dynamic water and oil production data at each experimental stage, demonstrating that the AHM method aligns more closely with the historically measured water production, particularly during high-water-cut periods, where prediction accuracy is significantly enhanced. The JBN method exhibits some deviations in describing oil-phase flow, whereas AHM, by accounting for reservoir heterogeneity and nonlinear fluid interactions, reproduces historical oil production curves more accurately. This is especially evident in regions with high residual oil saturation, indicating that AHM is more suitable for reservoirs with high-viscosity crude oil.

- (2)

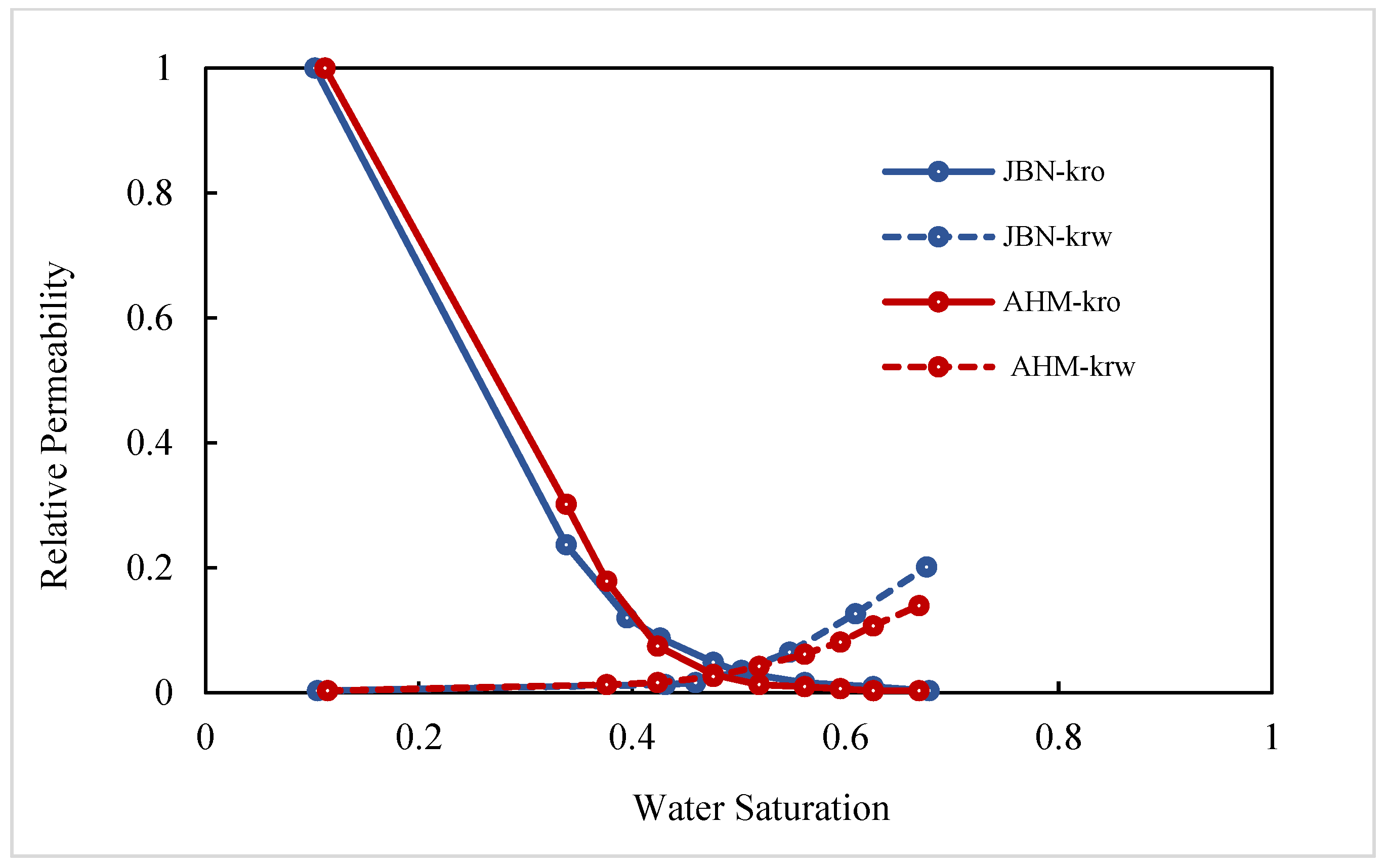

- Core with plate-like cross-bedding in the Y direction (small angle relative to bedding), exhibiting flow across the bedding planes with a relatively complex pathway. The displacement in the Y direction has a slightly larger angle relative to the bedding compared to the X direction, reflecting variations in reservoir anisotropy. Figure 12 and Figure 13 present comparative analyses of stage-wise water and oil production in the Y direction. The data indicate that water production in the Y direction increases gradually over time, and the predictions from the automatic history-matching method align more closely with experimentally measured historical water production, particularly during high-water-cut periods, where prediction errors are significantly reduced. Residual oil saturation decreases from 40.6% in the X direction to 33% in the Y direction, indicating improved oil displacement efficiency.

- (3)

- Core with plate-like cross-bedding in the Z direction (large angle relative to bedding), exhibiting cross-bedding flow with a complex pathway. In the Z-direction waterflooding experiments, the angle relative to the bedding further increases, reflecting a significant change in reservoir anisotropy. Figure 15 and Figure 16 present comparative analyses of stage-wise water and oil production in the Z direction. Water production in the Z direction shows a more pronounced upward trend over time, and predictions from the automatic history-matching method align more closely with experimentally measured historical water production, particularly during high-water-cut periods, where prediction errors are significantly reduced. Residual oil saturation decreases to 22%, and compared with the X direction, oil recovery efficiency in the Z direction improves by 21.14%, indicating that the further increase in bedding angle significantly enhances oil displacement. The JBN method exhibits certain deviations when describing oil-phase flow, whereas the automatic history-matching method, by accounting for reservoir heterogeneity and anisotropy in bedding orientation, better reproduces the historical oil production curve. This provides important support for predicting residual oil distribution and optimizing development strategies.

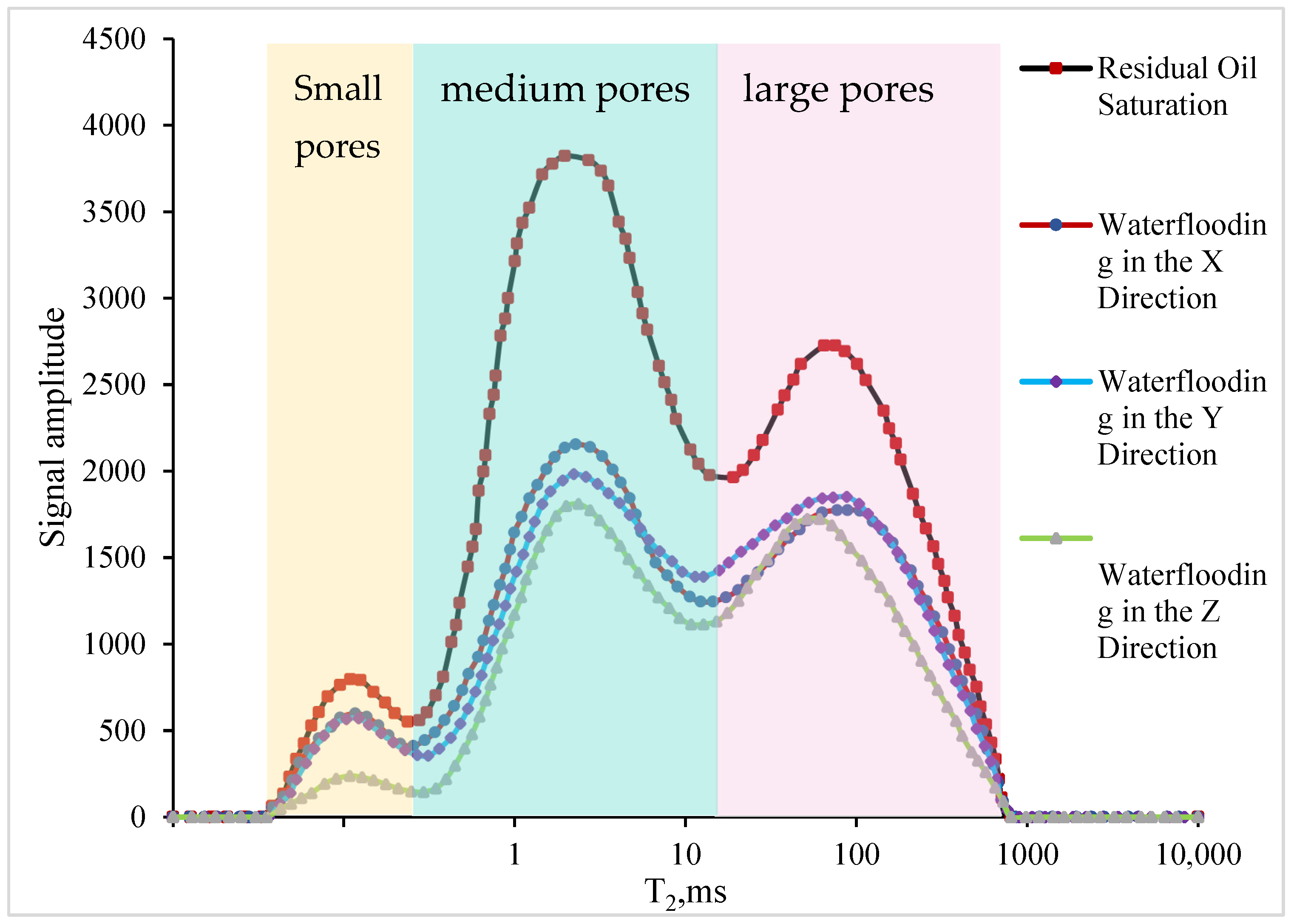

3.1.2. Parallel-Laminated Core

3.2. Microscopic Mechanism Analysis of Anisotropic Relative Permeability Curves

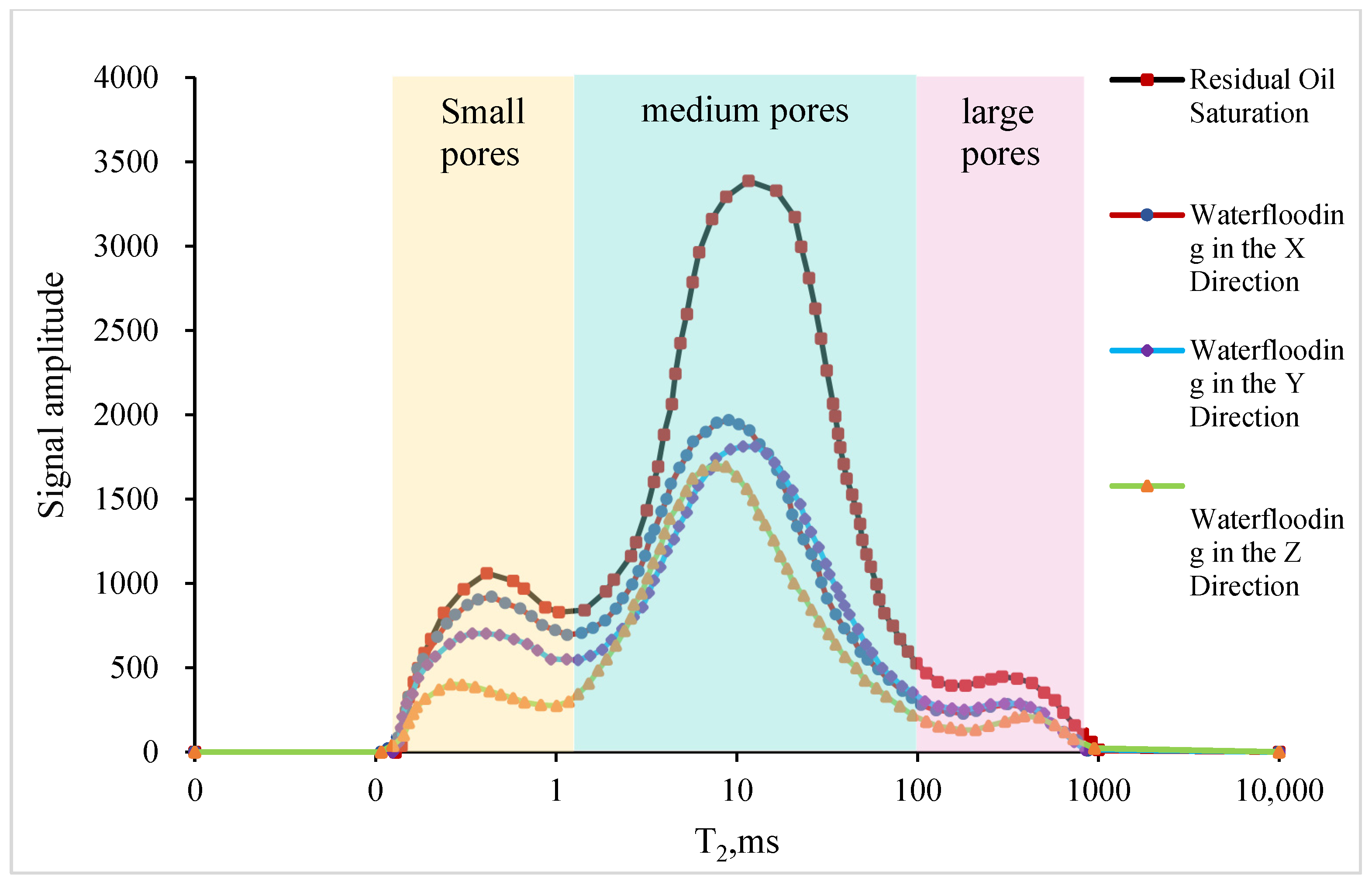

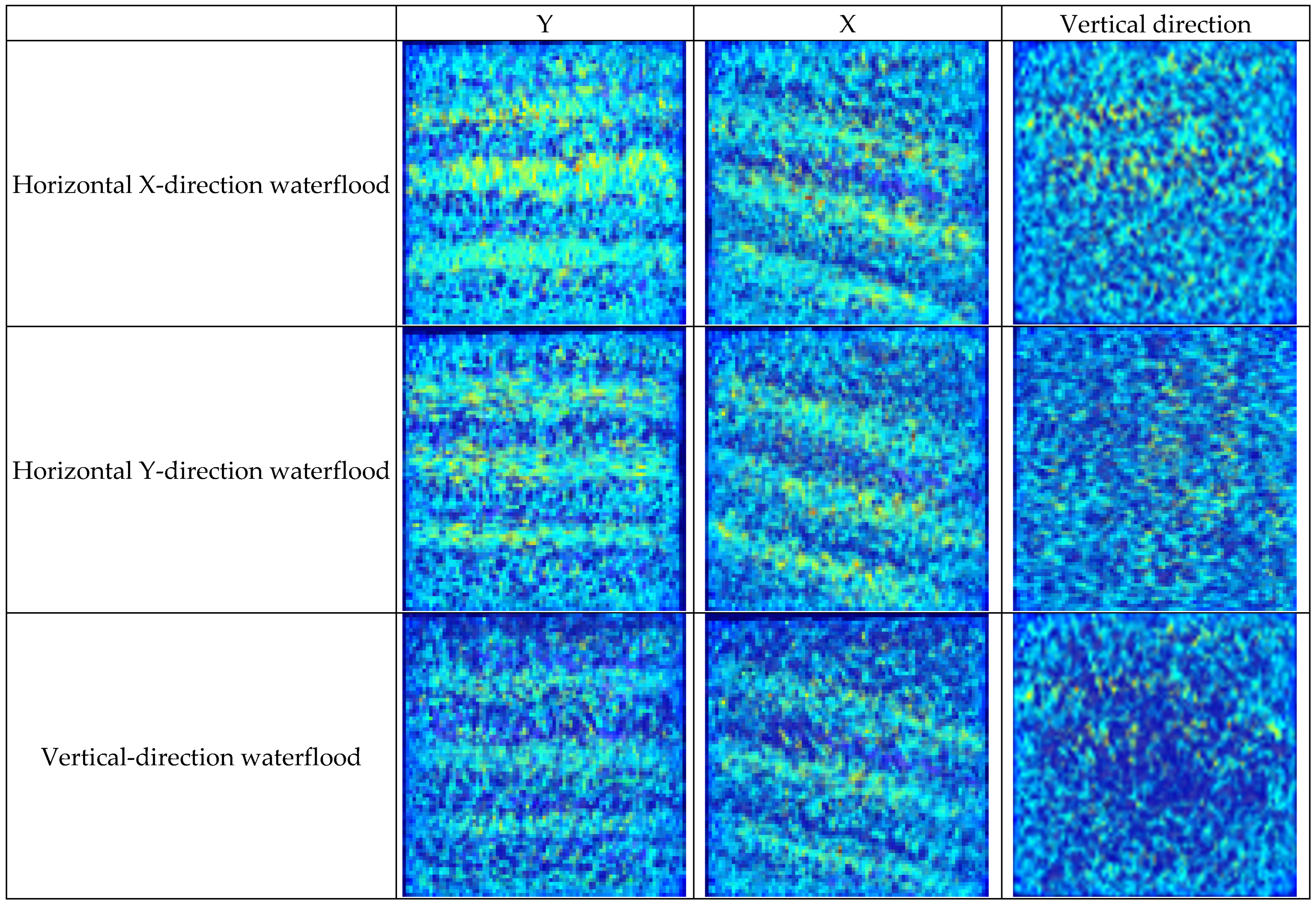

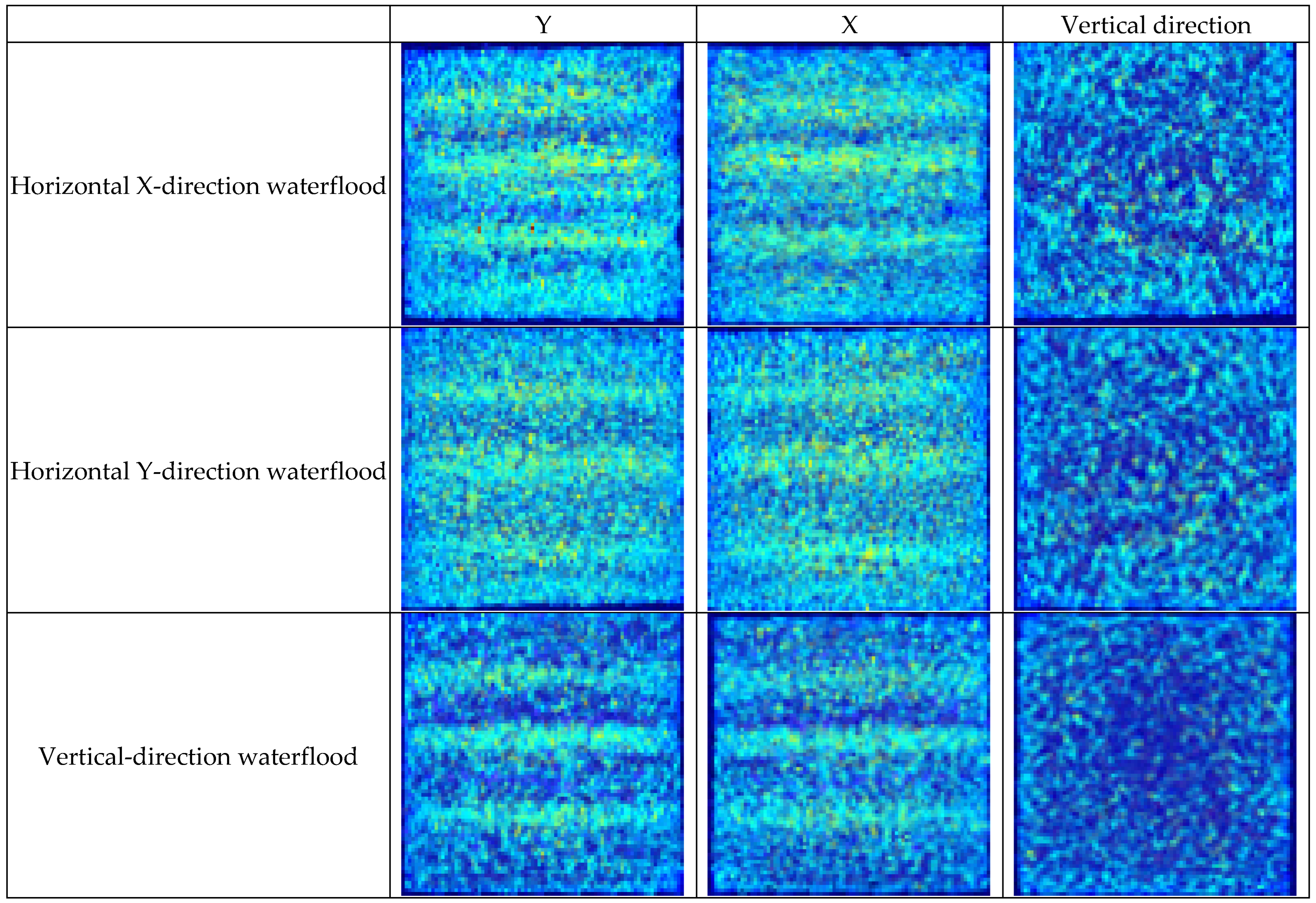

3.2.1. Analysis of NMR Results

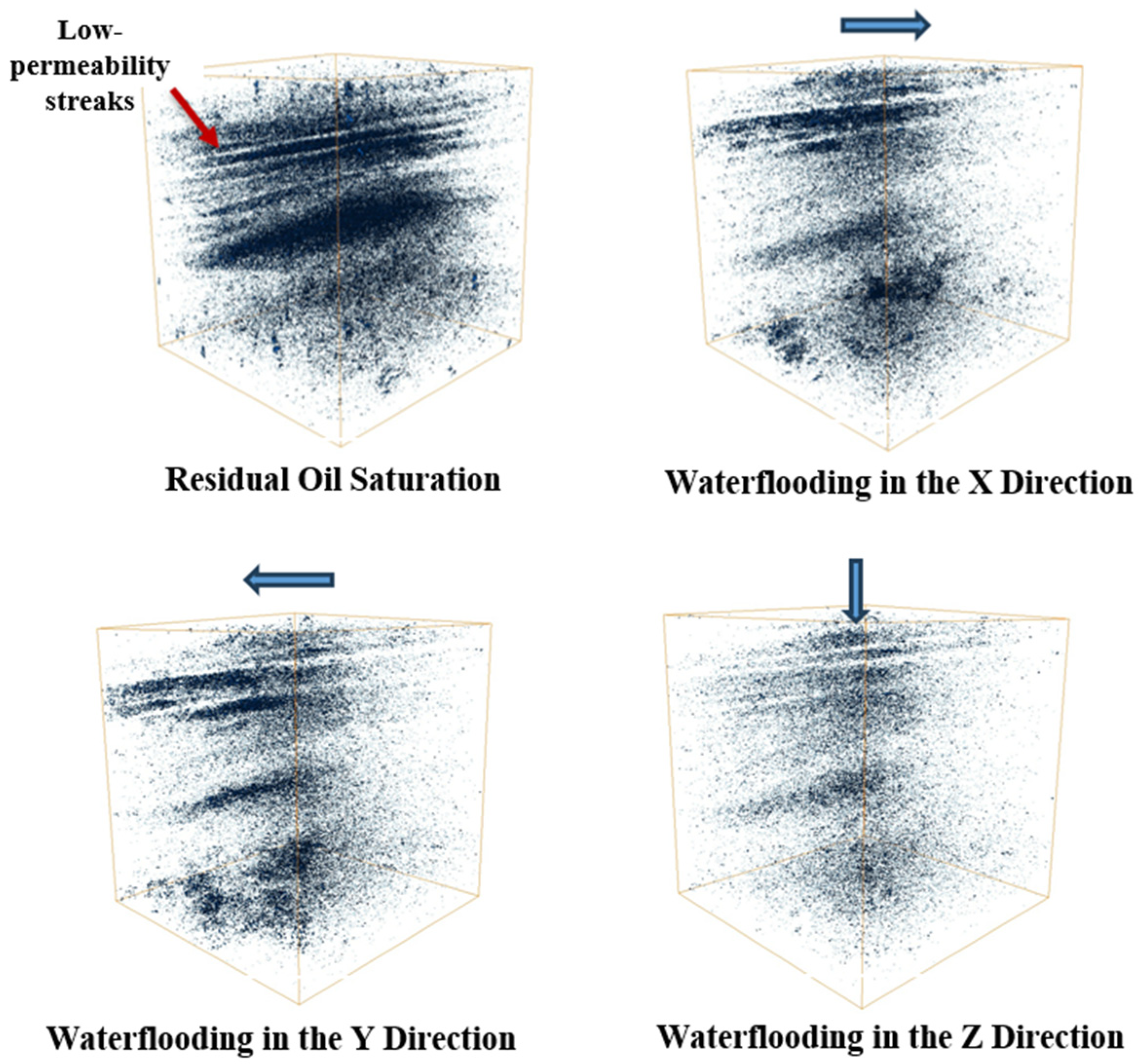

3.2.2. CT Scan Results Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1).

- Significant influence of displacement direction on oil recovery: The experiments demonstrate that increasing the angle between the displacement direction and lamination significantly enhances oil recovery. In interbedded laminated cores, oil recovery in the Z-direction (perpendicular to lamination, 90° angle) reached 75.09%, markedly higher than the X-direction (along lamination, 53.95%). For parallel laminated cores, vertical displacement improved recovery by 18.06% compared to horizontal flow. Vertical displacement promotes fluid penetration across lamination intersections, mobilizes oil in small pores, and reduces residual oil saturation. NMR and CT imaging confirm the uniformity of vertical displacement, providing practical guidance for optimizing water injection directions.

- (2).

- AHM method improves relative permeability accuracy: Compared to the conventional JBN method, the AHM technique, through numerical simulation and optimization algorithms, significantly enhances the precision of anisotropic relative permeability curves. Fitted curves closely match historical production data, particularly in predicting two-phase co-flow regions and endpoint saturations. For interbedded laminated cores, the co-flow region in the Z-direction reached 57.1%, much higher than 39.7% in the X-direction. By accounting for capillary forces and permeability heterogeneity, the AHM method is well-suited for complex reservoirs and provides reliable parameters for reservoir numerical modeling.

- (3).

- Microscale imaging reveals pore-scale flow mechanisms: NMR T2 spectra and CT scans indicate that displacement direction strongly affects pore-scale fluid distribution. Vertical-to-lamination displacement markedly increases oil mobilization in small pores, lowering residual oil saturation to 22% with more uniform distribution. Horizontal displacement favors channeling, leaving residual oil concentrated in low-permeability zones. CT imaging shows that vertical displacement overcomes capillary restrictions and enhances oil–water interfacial shear. These microscale insights provide direct evidence of anisotropic flow mechanisms, supporting optimized reservoir development strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.-B.; Qin, P.; Chen, X. Strategic oil stockpiling for energy security: The case of China and India. Energy Econ. 2017, 61, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China’s Dependence on Strategic Fuel Imports and Opportunities for Global Fuel Exporters. Andaman Partners. 7 October 2025. Available online: https://andamanpartners.com/2025/10/chinas-dependence-on-strategic-fuel-imports-and-opportunities-for-global-fuel-exporters/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Kang, Y.; Lei, Z. The strategic thinking of unconventional petroleum and gas in China. Earth Sci. Front. 2016, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.; Zhu, R.; Liu, K.; Su, L.; Bai, B.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J. Tight gas sandstone reservoirs in China: Characteristics and recognition criteria. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, M.; Dong, J.; Yu, T.; Ding, K.; Liu, Y. Assessment of Refracturing Potential of Low Permeability Reservoirs Based on Different Development Approaches. Energies 2024, 17, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, B. A Review of Measurement and Evaluation Methods for Permeability Anisotropy. Progress. Geophys. 2017, 32, 2552–2559. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Vector Characteristics and Computational Models of Directional Rock Permeability. Rock Soil Mech. 2005, 26, 1294–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yi, Y.; Min, Z.; Feng, H. Experimental Study on Permeability Anisotropy of Deep Reservoir Sandstone under True Triaxial Stress. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2023, 55, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Wang, G.; Ye, R.; Zhou, Z.; Cui, Y. Impact of diagenesis on the reservoir quality of tight oil sandstones: The case of Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation Chang 7 oil layers in Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 145, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, C.; Wei, D. Formation, Distribution and Exploration Countermeasures of Tight Oil in the Sixth Member of Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Southeastern Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2025, 46, 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Du, Q.; Lin, C.; Zhang, T. Distribution characteristics and controlled factors of residual oils in Daqing oilfield. Oil Gas Geol. 2001, 22, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.; Guo, B.; Li, J.; Huang, F. Comparison Study on Accumulation & Distribution of Tight Sandstone Gas Between China and the United States and Its Significance. Chin. J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 14, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shabdirova, A.; Minh, N.H.; Zhao, Y. A sand production prediction model for weak sandstone reservoir in Kazakhstan. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 11, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, S.; Jones, J.; Yang, R.; Wei, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, C.; Liu, W. Overpressure and its positive effect in deep sandstone reservoir quality of Bozhong Depression, offshore Bohai Bay Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 182, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, B.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, H. Technical Strategy Thinking for Developing Continental Tight Oil in China. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2015, 182, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ma, H.; Chang, C.; Xie, W. Study on the development options of tight sandstone oil reservoirs and their influencing factors. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 1007224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Qu, Z.; Wang, M.; Ran, W. The Influence of Micro-Heterogeneity on Water Injection Development in Low-Permeability Sandstone Oil Reservoirs. Minerals 2023, 13, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, P.; Sun, J.; Yan, W.; Luo, X.; Feng, P. Investigating the causes of permeability anisotropy in heterogeneous conglomeratic sandstone using multiscale digital rock. Geophysics 2024, 89, MR197–MR207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China National Offshore Oil Corporation Energy Economics Institute. 2024 Domestic and International Oil and Gas Industry Situation Analysis and Related Suggestions. In China Energy Observation; China National Offshore Oil Corporation Energy Economics Institute: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, N.J.C.; Healy, D.; Taylor, C.W. Anisotropy of permeability in faulted porous sandstones. J. Struct. Geol. 2014, 63, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Feng, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. A new method of calculating relative permeability curve with performance data. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2009, 16, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Wang, H.; Ershadnia, R.; Hosseini, S. Anisotropy of two-phase relative permeability in porous media and its implications for underground hydrogen storage. Adv. Water Resour. 2025, 206, 105127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergament, A.K.; Tomin, P.Y. The Study of Relative Phase-Permeability Functions for Anisotropic Media. Math. Models Comput. Simul. 2012, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavaud, J.B.; Maineult, A.; Zamora, M.; Rasolofosaon, P.; Schlitter, C. Permeability anisotropy and its relations with porous medium structure. J. Geophys. Res. Solid. Earth 2008, 113, B01202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, S.; You, Q.; Yu, C. A New Measurement of Anisotropic Relative Permeability and Its Application in Numerical Simulation. Energies 2021, 14, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, B.; Wang, B. The development well_pattern of low and anisotropic permeablity reservoirs. Acta Pet. Sin. 2002, 23, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, B.; Xu, H. Effects of microscopic pore structure heterogeneity on the distribution and morphology of remaining oil. Pet. Explor. Dev. Online 2018, 45, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, F.; Tu, B.; Cheng, S. Measurement Method of Anisotropic Permeability in Heterogeneous Radial Flow of Whole Rock Core. Acta Pet. Sin. 2005, 6, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.; Chen, Y.; You, L.; Wu, P. A New Method for Measuring Liquid Permeability of Tight Cores—Capillary Flow Viscosity Method. Drill. Fluid Complet. Fluid 2007, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, X.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liang, X.; Mao, Y. Anisotropic characteristics of relative permeability of sedimentary reservoirs and their influence on seepage. Pet. Sci. Bull. 2024, 4, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.F.; Bossler, D.P.; Naumann, V.O. Calculation of Relative Permeability from Displacement Experiment. Pet. Trans. AIME 1959, 216, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.C.; Roszelle, W.Q. Graphical Technical for Determining Relative Permeability from Displacement Experiments. JPT 1978, 30, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Yang, P.; Shen, P. Calculating the Relative Permeability from Displacement Experiments Based on Percolation Theory. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2001, 28, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Xu, S.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Elsworth, D. Interpretation of Gas/Water Relative Permeability of Coal Using the Hybrid Bayesian-Assisted History Matching: New Insights. Energies 2021, 14, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishman, J.R. Core Permeability Anisotropy. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 1970, 9. No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glad Aslaug, C.; Afrough, A.; Amour, F.; Ferreira, C.A.; Price, N.; Clausen, O.R.; Nick, H.M. Anatomy of fractures: Quantifying fracture geometry utilizing X-ray computed tomography in a chalk-marl reservoir; the Lower Cretaceous Valdemar Field (Danish Central Graben). J. Struct. Geol. 2023, 174, 104936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, G.; Shen, P. A Method for Calculating Transient Oil-Water Relative Permeability Curves. Pet. Explor. Dev. 1982, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, A.; Othman, F.; Ge, J.; Le-Hussain, F. Modified Johnson–Bossler–Naumann Method to Incorporate Capillary Pressure Boundary Conditions in Drainage Relative Permeability Estimation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 210, 110064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhan, S.; Li, D.; Sheng, G. Correction for Capillary Pressure Influence on Relative Permeability by Combining Modified Black Oil Model and Genetic Algorithm. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, R.; Simjoo, M.; Chahardowli, M. Low Salinity Water Flooding: Estimating Relative Permeability and Capillary Pressure Using Coupling of Particle Swarm Optimization and Machine Learning Technique. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Duan, T.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J. Research progress in reservoir automatic history matching. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2016, 34, 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sedahmed, M.; Coelho, R.C.V.; Warda, H.A. An Improved Multicomponent Pseudopotential Lattice Boltzmann Method for Immiscible Fluid Displacement in Porous Media. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 023102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.T.; Seinfeld, J.H.; Gavalas, G.R. An Analysis of History Matching in Reservoir Simulation. SPE J. 1980, 20, 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, D.S. Application of Genetic Algorithms to History Matching. SPE Adv. Technol. Ser. 1994, 2, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen, G. Sequential Data Assimilation with a Nonlinear Quasi-geostrophic Model Using Monte Carlo Methods to Forecast Error Statistics. J. Geophys. Res. 1994, 99, 10143–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geir, N.; Mannseth, T.; Vefring, E.H. Near-Well Reservoir Monitoring Through Ensemble Kalman Filter. In Proceedings of the SPE/DOE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 13–17 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M. Application of ensemble Kalman filter in nonlinear reservoir problem. J. China Univ. Pet. 2010, 34, 188–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-D.; Li, M. A Calculation Method for Unstable State Oil-Water Relative Permeability Curve Based on Ensemble Kalman Filter. J. China Univ. Pet. 2012, 36, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Kim, S.; Jung, H.; Choe, J.; Lee, K. Characterization of three-dimensional channel reservoirs using ensemble Kalman filter assisted by principal component analysis. Pet. Sci. 2019, 17, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Zafari, M.; Reynolds, A.C. Quantifying Uncertainty for the Punq-S3 Problem in A Bayesian Setting with Rml and Enkf. Spring Simul. Multiconf. 2005, 11, 506–515. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Reynolds, A.C. An Iterative Ensemble Kalman Filter for Data Assimilation. SPE J. 2007, 14, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.; Song, W.; Chen, H.; Guo, S.; Li, X.; Sun, Z. Automatic History Matching Method and Application of Artificial Intelligence for Fractured-Porous Carbonate Reservoirs. Processes 2024, 12, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Jia, D.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, S. A Multi-Scale Numerical Simulation Method Considering Anisotropic Relative Permeability. Processes 2024, 12, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, S.E.; Leverett, M.C. Mechanism of Fluid Displacement in Sands. Trans. AIME 1942, 146, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welge, H.J. A Simplified Method for Computing Oil Recovery by Gas or Water Drive. J. Pet. Technol. 1952, 4, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Core ID | Brine Salinity (ppm) | Crude Oil Viscosity (mPa·s) | Porosity (%) | Apparent Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-1 | 4400 | 77 | 20.8 | 127.45 |

| A-2 | 4400 | 77 | 20.8 | 129.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, L.; Jiang, L.; Wang, S.; Bai, B.; Kang, Z. Displacement Experiment Characterization and Microscale Analysis of Anisotropic Relative Permeability Curves in Sandstone Reservoirs. Energies 2026, 19, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010163

He Y, Guo Y, Wu L, Jiang L, Wang S, Bai B, Kang Z. Displacement Experiment Characterization and Microscale Analysis of Anisotropic Relative Permeability Curves in Sandstone Reservoirs. Energies. 2026; 19(1):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010163

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yifan, Yishan Guo, Li Wu, Liangliang Jiang, Shuoliang Wang, Bingpeng Bai, and Zhihong Kang. 2026. "Displacement Experiment Characterization and Microscale Analysis of Anisotropic Relative Permeability Curves in Sandstone Reservoirs" Energies 19, no. 1: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010163

APA StyleHe, Y., Guo, Y., Wu, L., Jiang, L., Wang, S., Bai, B., & Kang, Z. (2026). Displacement Experiment Characterization and Microscale Analysis of Anisotropic Relative Permeability Curves in Sandstone Reservoirs. Energies, 19(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010163