1. Introduction

In a broader context, construction materials contribute to environmental impacts and climate change through embodied carbon emissions. For decades, the emphasis was mainly on reducing the operational energy use and related emissions, whether in renovated or newly constructed buildings. Measures aimed at increasing energy efficiency have led to a decline in the share of operational energy and emissions in buildings’ overall environmental impact [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The measures considered included thermal modernisation in buildings, improvements to heating systems, the utilisation of alternative energy and heat sources, and the adoption of renewable energy sources [

6,

7,

8].

While the trend toward reducing operational impacts is positive, it should not come at the expense of increased embodied emissions [

9]. The European Union aims to achieve carbon-neutral buildings by 2050 [

10]. One study [

11] provides a brief overview of the development of energy-efficient and sustainable construction in Central Europe, presents an analytical review, and outlines prospects. The decarbonisation of the building sector requires addressing not only operational energy use but also embodied energy and the resulting greenhouse gas emissions. While operational performance has been the focus of regulation for decades, embodied impacts remain comparatively underexplored in both research and practice. Another paper [

12] presents a literature review of strategies for reducing embodied carbon in buildings, as well as methods for assessing it. The study also highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each method. Some studies assess environmental indicators (embodied energy and embodied carbon) for individual building materials [

13,

14,

15], and others evaluate technical solutions for entire buildings to analyse ways to reduce embodied or operational energy and carbon [

16]. Gervasio and Dimova [

17] proposed the creation of environmental benchmarks for buildings at the European level, underlying the importance of harmonised approaches. The benchmarks should be determined from an inventory of existing building stock, a relatively laborious process. Harmonised national methodologies based on databases of real projects are described for the Czech Republic by Železná et al. [

18] and for Denmark by Ole and Grau et al. [

19]. This trend is also reflected in recent studies, such as Szalay’s [

20], which highlight methodological challenges and the urgent need for robust frameworks to quantify embodied energy. Simultaneously, the study presents a methodology for developing embodied environmental benchmark values for buildings using a parametric model to generate hypothetical buildings. A pilot case study assessing the carbon footprint of office buildings in Poland was conducted by Rucińska et al. [

21]. The results of these studies [

18,

19,

20,

21] show that the reliability of the carbon footprint benchmark value is primarily influenced by the quality and representativeness of the input data, rather than by the building typology or the software used. The parametric approach (Szalay [

20]) is suitable for countries and environments with limited real data, while a harmonised national methodology appears to offer greater accuracy and usability for legislative processes. Despite these contributions, the literature remains relatively scarce, and systematic methods for integrating embodied impacts into early design decisions are still limited.

Simultaneously, regulatory frameworks are evolving rapidly. EPBD IV [

10] introduces mandatory GWP calculations for new buildings above 1000 m

2 from 2028 and for all new buildings from 2030. Given this time constraint, Rabenseifer et al. [

22] propose obtaining data on embodied energy and related greenhouse gas emissions as part of the energy certification of buildings during building approval. After a transition period, which a parametric methodology could support, it would be possible to set benchmark values for environmental indicators related to embodied energy using large amounts of real data. The present study also considers this assumption. Some Member States have already moved ahead: France, through its RE2020 regulation [

23], requires dynamic LCA and progressively stricter carbon thresholds, while Denmark has introduced mandatory embodied carbon limits for new buildings since 2023 [

24], with further reductions scheduled for 2025, 2027, and 2029 [

25].

Since the 1980s, the shape factor, expressed as the ratio of a building’s envelope area to its heated volume, has been a critical determinant of operational energy demand, serving as the basis for many national energy certification schemes. Our earlier work [

22] extended this concept to embodied impacts, demonstrating that the shape factor also governs the efficiency with which materials are used relative to the usable floor area. Absolute values of embodied energy or GWP are inherently biased toward larger buildings, while per-square-meter indicators still fail to capture geometric efficiency. Only by normalising impacts through the shape factor can buildings be compared fairly regarding both embodied and operational energy. The present manuscript builds on this insight, testing whether geometry-based assessment of embodied impacts (A1–A3) can confirm the relevance of the shape factor and proposing its consideration in the context of EPBD IV implementation.

The issue of the impact of buildings on the environment, and thus, also on climate change, is closely tied to the so-called life cycle of a building, which encompasses all stages of its existence. Within this life cycle, we distinguish between two types of energy—operational and embodied energy—along with their associated emissions. We also differentiate system boundaries, defining individual processes and stages. These boundaries must be clearly established when using the life cycle assessment (LCA) method [

26].

Currently, tools based on the LCA method are widely used for systematic, holistic assessment of a building’s life cycle [

27,

28]. However, obtaining accurate data for evaluation using this method is complex, as values often differ across the many sources [

29]. The complexity of the calculation and the inaccuracies in the results are considered significant obstacles to evaluating using LCA. Nevertheless, even imperfect estimates of environmental indicator values are better than completely ignoring these impacts [

30]. This study addresses this gap by using a simplified method tailored to conceptual design stages, differing from prior work by focusing on geometric parameters. Recommendations in several publications call for simplifying the calculation method [

30,

31], aligning with our approach, and for developing standardised measurement frameworks [

29]. Of course, every evaluation system also requires appropriately set benchmarks. Their establishment is already becoming the subject of expert discussion [

32].

This study seeks to address several questions. How do fundamental geometric parameters (building size, number of storeys, roof geometry, and plan proportions) affect embodied environmental impacts when normalised per unit of usable floor area and interpreted through the building’s surface-to-volume relationship? Can the shape factor, defined as the ratio of the building’s envelope area to its heated volume (A/V ratio), provide a fair and consistent geometric denominator for comparing embodied environmental performance across building typologies, and what implications does this have for future benchmark development in regulatory frameworks such as EPBD IV? Against this background, the present study develops and tests a geometry-based methodology for estimating embodied energy and CO2 emissions, aiming to bridge the gap between academic research, design practice, and emerging regulatory requirements.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aimed to verify the influence of the volume and spatial composition of selected family house samples on the values of environmental indicators at the product stage of the building’s life cycle. The samples were created in simplified form, at the level of an architectural study, which typically defines the building’s volume and basic material composition.

2.1. Defining, Simplifying, and Modelling Samples

Family houses were selected as the research subject due to the current relevance of affordable housing scarcity and their relatively simple geometry. The dimensions, proportions, and shape of a family house are often integral to its conceptual design, and environmental criteria must be incorporated into the decision-making process. In practice, architects work with simplified volumes during the conceptual phase, where the range of possibilities is virtually endless. Therefore, it was necessary to limit the number of samples used in the study.

Based on an analysis of several publications [

33,

34,

35], threshold values for the built-up area (A

BU) of family houses were identified. Considering current trends in the architecture of family houses, we selected built-up areas of 60, 120, and 180 m

2. These represent 2× and 3× scalings of the smallest value, allowing us to observe changes in environmental indicator (EI) values due to proportional size differences.

The sample of a family house with A

BU = 60 m

2 represents a more contemporary, minimalist approach to housing and considers the economic aspect. The reference area of 120 m

2 was selected because it closely corresponds to the average built-up area of single-family houses reported in the previously mentioned housing studies [

33,

34,

35]. The maximum built-up area of the samples was set at 180 m

2, while higher A

BU values were observed, especially in bungalow-type or multi-generational houses. Using multiples of the area, we were able to subtract from the results the effects of a proportional change in size, different A

BU, and different dimensions, while keeping the same floor plan proportions. Simultaneously, we also examined the influence of the object’s proportions—the same A

BU, with different dimensions.

The width WS and length LS of the samples were based on the defined built-up areas and the shape variation in the floor plan proportions. Square and rectangular floor plans were chosen, using an analogy in which the width of related samples remained constant while the length varied. With this method, we were able to observe the effect of a disproportionate change in size—different ABU, with one side of the sample with a double dimension.

The study included both single-storey and two-storey houses, which are the most common types. While it did not include a formal sensitivity analysis, the use of scaled ABU values and varied roof types provided insight into geometric influence. Future work may incorporate parametric sensitivity testing.

For roof types, we varied the pitch of gable roofs (30° and 45°), used a uniform 30° slope for hip roofs, and neglected slope for flat roofs, as it does not significantly affect the results.

We set the average share of the linear length of load-bearing walls from the floor area to 15% and for partition walls to 20%. The resulting area of internal structures is then obtained by multiplying their linear lengths by the ceiling height of the room.

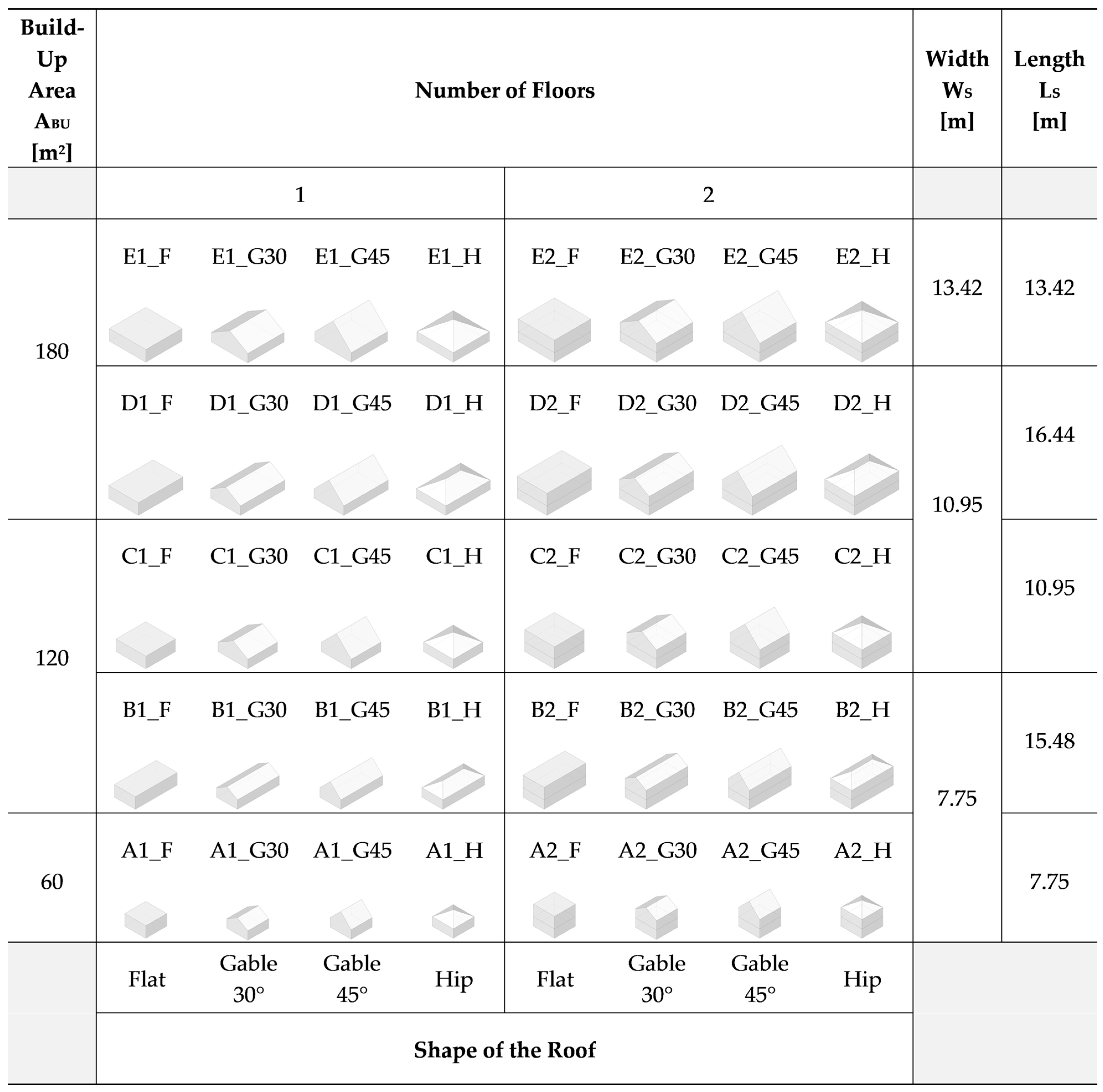

Using a combination of individual parameters, 40 samples were generated (

Figure 1). The investigated samples were processed in a 3D modelling program using simplified volumes typical of early architectural design stages.

2.2. Environmental Indicators

To monitor the impact of the samples on the environment, the environmental indicators listed below were used because they are in accordance with the standard STN EN 15804+A2 (2020) [

36] and, simultaneously, are among the three most commonly used in building life cycle assessment [

31]:

PENRTi—the primary energy total from non-renewable sources used in the sample construction per 1 m2, expressed in kWh/m2. Since the values in the database are stated in MJ/reference unit, it was necessary to convert them, with 1 kWh = 3.6 MJ. The quantity expresses the content of produced primary energy, which is obtained from non-renewable energy sources.

GWPi—the global warming potential total of the sample construction per 1 m2, expressed in kg CO2 eq./m2. It expresses the amount of emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming, and their amount is expressed in equivalent amounts of CO2. In this article, this is referred to as “embodied emissions.”

APi—the acidification potential of the sample construction per 1 m2, expressed in kg SO2 eq./m2. Since the values in the database are expressed in mol H+ eq./reference unit, it was necessary to convert the values, whereby 1 kg SO2 eq. = 31.3 mol H+ eq. This quantity represents the potential for acidification of water, soil, vegetation, and buildings.

2.3. Scope and System Boundaries

The resulting values were calculated only for the product stage of the life cycle of buildings, also referred to as the “cradle to gate”. The product stage includes standardised module designations A1–A3 in accordance with the standard STN EN 15804+A2 (2020) [

36], i.e., processes related to raw material extraction and supply, transport to the manufacturing site, and the manufacturing of building materials. These emissions are produced before the building is operated and are also referred to as “upfront carbon”. They are the least demanding regarding availability and data acquisition, yet among the most frequently used in the construction sector. Research [

30] shows that it is the only stage at which it was possible to obtain available and relatively accurate data. In the other stages, it is mostly focused on values based on estimates. The product stage is also responsible for the largest share of embodied emissions in a building’s life cycle [

4,

32,

37]. Although this approach limits scalability, it allows for reliable assessment in the early stages.

2.4. Building Materials

Within all samples, the same construction components made of conventional materials were used. The selected components reflect typical construction practices in Central Europe and meet minimal national thermal and technical requirements for external building components, in accordance with STN 73 0540-2+Z1+Z2 (2019) [

38]. Since the study focuses solely on the product stage, emissions from other life cycle stages were not included, and the material lifespan was therefore not considered.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 show the main characteristics of the examined components in the form of their fragments: the load-bearing wall, flat roof, pitched roof, floor on the ground, internal load-bearing wall, internal partition, ceiling, and window.

2.5. Computations

Although full LCA validation is beyond the scope of this study, the use of standardised databases and conventional materials ensures methodological consistency. The values of environmental indicators per 1 m

2 of each construction were calculated, i.e.,

PENRTi,

GWPi, and

APi. The values for environmental indicators of building materials were obtained from the freely available database “oekobaudat.de” [

39].

The values in the database comply with the standard STN EN 15804+A2 (2020) [

36] and were derived from GaBi data [

40]. To obtain the values of the environmental indicators of the constructions of the sample, the total areas of the constructions (

Pi) were multiplied by the corresponding value of the EI per 1 m

2 of the construction. Despite the availability of various specialised LCA software, MS Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used for the calculations.

PENRTX—the primary energy total from non-renewable sources of the whole sample construction [GJ] was obtained as

GWPX—the global warming potential total of the whole sample construction [t CO

2 eq.] as

APX—the acidification potential of the whole sample construction [kg SO

2 eq.] as

Subsequently, the EI values for all constructions in the sample were summed to yield the final EI for the whole sample.

PENRT—the primary energy total from non-renewable sample sources [GJ] was calculated as

GWP—the global warming potential total of the sample [t CO

2 eq.] as

AP—the acidification potential of the sample [kg SO

2 eq.] as

To assess effectiveness and objectively compare samples, the EI values were divided by the usable area (AUF) of each sample. We repeated the same process for all samples.

PENRTUF—the primary energy total from non-renewable sources per 1 m

2 usable floor of the sample [GJ] was equal to

GWPUF—the global warming potential per 1 m

2 of usable floor of the sample [t CO

2 eq.]:

APUF—the acidification potential per 1 m

2 of usable floor of the sample [kg SO

2 eq.]:

In addition to calculating embodied energy and GWP in absolute terms and per square meter of usable floor area, we also evaluated results in relation to the shape factor, defined as the ratio of the building’s envelope area to its heated volume (A/V ratio). This indicator is widely used in energy performance certification to assess operational energy demand, and its extension to embodied impacts has been proposed in previous research [

22]. By incorporating the shape factor, the aim was to test whether geometric efficiency can serve as a unifying metric for both operational and embodied performance. While no regulatory thresholds currently exist for embodied impacts relative to the shape factor, the methodology anticipates the possibility of establishing such benchmarks once sufficient empirical data are collected from design practice and certification processes.

3. Results

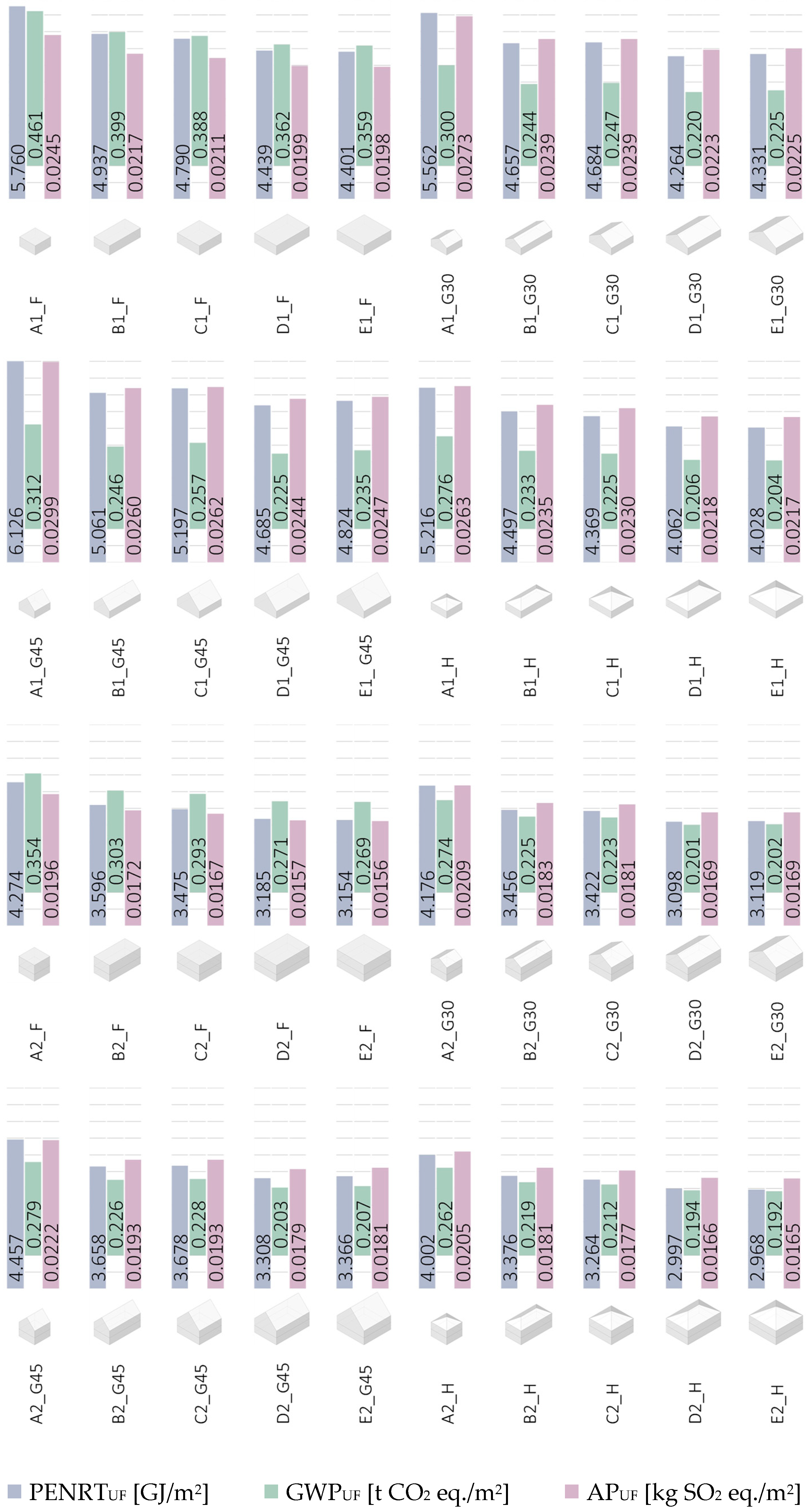

The results were evaluated by relating the useful floor area (

AUF) to the environmental indicators (EI): primary energy from non-renewable sources (PENRT), global warming potential (GWP), and acidification potential (AP). The analysis shows how variations in geometry—floor area, proportions, number of storeys, and roof shape—affect embodied impacts. Importantly, changes in volume do not correspond proportionally to EI values (see

Figure 2), since the contribution of individual construction components varies with geometry.

To clarify how specific design parameters affect embodied performance, the results are presented in four groups, each highlighting a distinct geometric factor:

For samples with varying built-up and usable floor areas but identical floor plan ratios, the greatest improvement in EIUF values is observed in the largest sample, which has three times the ABU value. Houses with larger built-up areas are therefore more efficient regarding EI values. It should be mentioned that the compared houses differ significantly in both built-up and usable floor areas.

The improvement in values when altering the floor plan proportions of samples with the same ABU is relatively minor. More compact (square-like) plans yield slightly better results than elongated rectangular ones, with the effect most visible in smaller houses.

Two-storey variants consistently outperform single-storey ones with similar usable areas due to reduced envelope-to-volume ratios.

The roof geometry significantly influences results. Hip roofs achieve the lowest PENRT and GWP per square meter, while flat roofs perform best for AP but nearly double embodied emissions compared to other types.

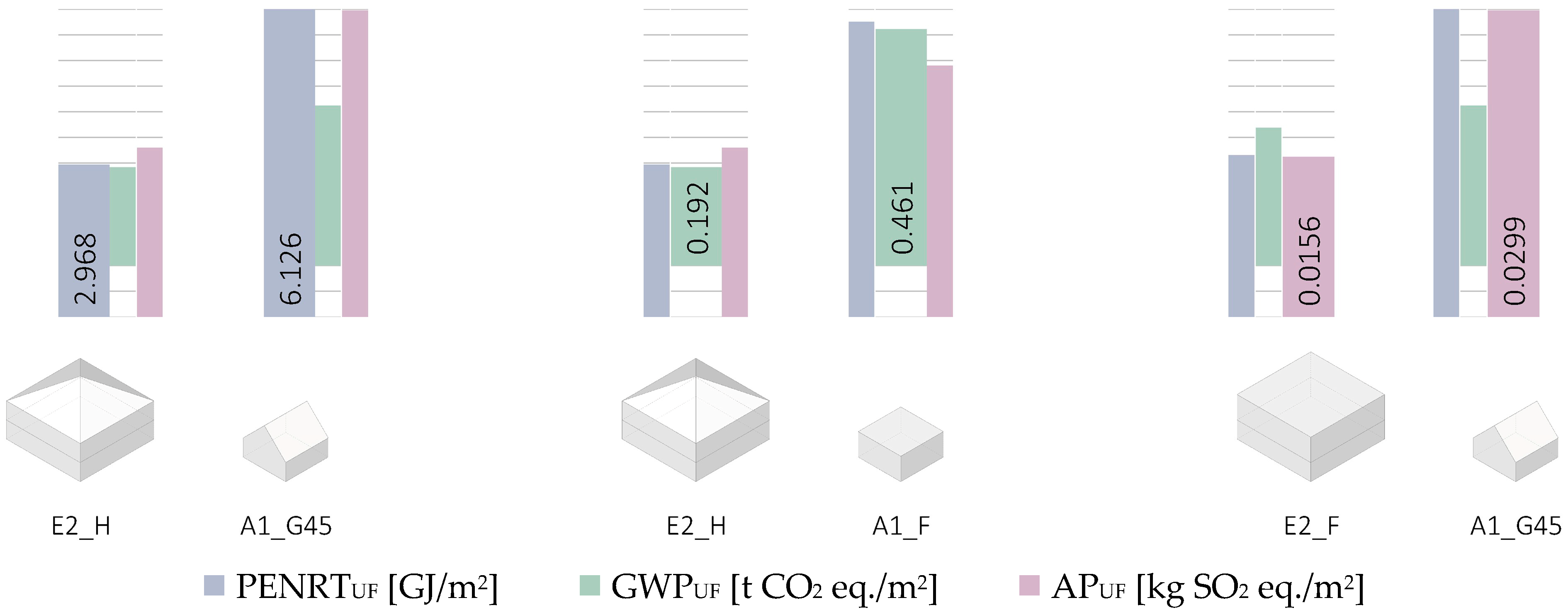

Overall, the most favourable configuration combines a larger built-up area, two storeys, and a hip roof (sample E2_H). Simultaneously, the least efficient is the smallest, single-storey house with a gable or flat roof (A1_G45). These findings confirm that geometric efficiency, as measured using the shape factor (envelope area to heated volume), is decisive for embodied performance, a conclusion further underlined by

Figure 3, which shows significant values of environmental indicators (EIs) per 1 m

2 of usable floor area (

AUF) for selected samples.

Although the smallest houses have the lowest absolute impacts, larger two-storey houses are more efficient per unit of usable floor area. This does not imply that the house size should be artificially increased, but rather that limit values for environmental indicators should account for geometry.

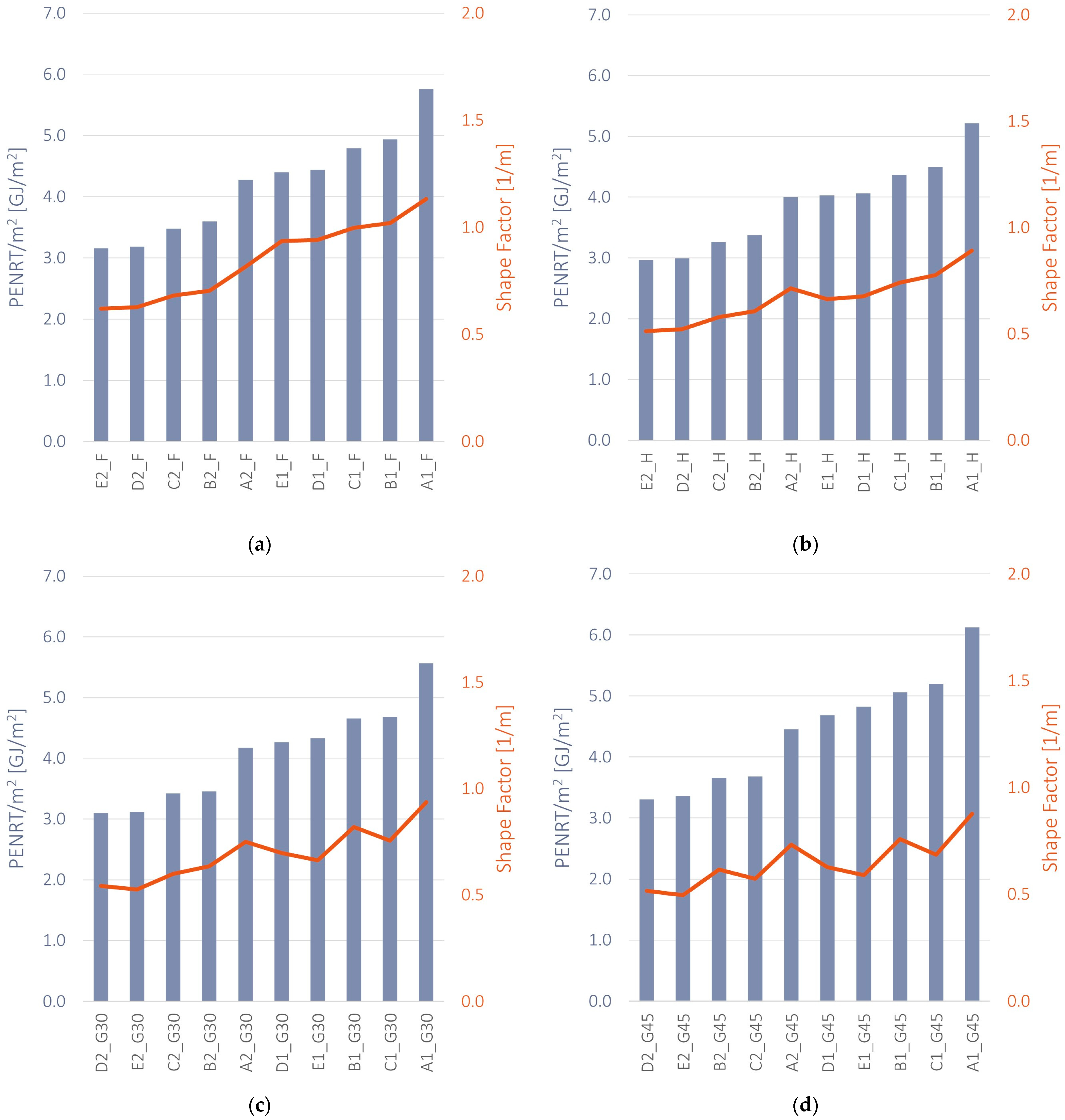

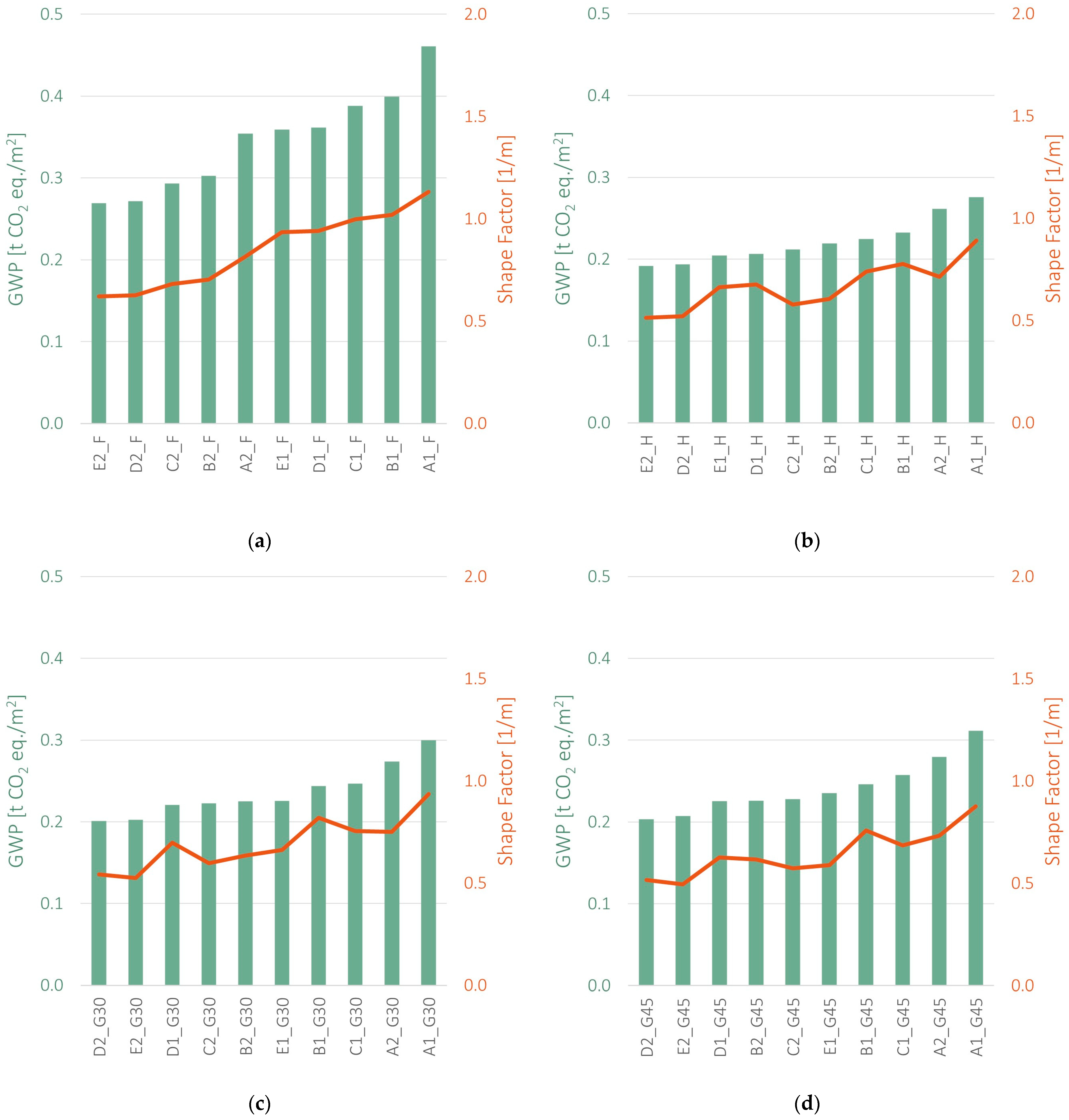

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate the correlation between environmental indicators (PENRT/m

2 and GWP/m

2, primary y-axis) and the shape factor (envelope area to heated volume, secondary y-axis) for all building variants of a given roof type. The graphs clearly show that as building size increases, the shape factor decreases, and the relative environmental burden per square meter decreases as well. This confirms that geometric efficiency, as measured by the shape factor, is a decisive parameter for embodied performance.

Together, these results support the integration of simplified environmental indicator calculations into early design phases. They provide a foundation for establishing benchmarks that reflect both embodied impacts and geometric fairness and for their eventual incorporation into national standards and the implementation of EPBD IV. In this context, the shape factor emerges as a practical and transparent criterion for ensuring fair comparison across buildings of different sizes and geometries.

4. Discussion

The results of this study underscore the importance of considering geometric parameters in the early design stages of residential buildings. While smaller houses naturally exhibit lower total environmental impacts, the analysis reveals that larger, two-storey houses are more efficient when environmental indicators are normalised per square meter of usable floor area (AUF).

This finding challenges the common assumption that minimising building size always leads to better environmental outcomes. Instead, this study shows that design efficiency—achieving more usable space with less material—plays a critical role in reducing embodied emissions and energy use. Two-storey configurations, for example, require less external envelope per unit of floor area, resulting in lower PENRTUF, GWPUF, and APUF values.

The influence of roof shape is also significant. Hip roofs consistently outperform other roof types in terms of embodied energy and emissions, likely due to their compact form and efficient material distribution. Flat roofs, while favourable regarding acidification potential (APUF), tend to have higher overall embodied emissions, suggesting trade-offs that must be considered in design decisions.

This study also highlights that floor plan proportions have a relatively minor impact on environmental performance, especially in larger houses. However, more compact shapes (closer to square) offer slight advantages in smaller buildings, where surface-to-volume ratios are more critical.

Finally, the findings support the development of standardised limit values for environmental indicators that account for both small and large houses. While smaller homes have lower absolute impacts, larger homes may be more efficient per unit area. When normalised by the shape factor (building’s envelope area to its heated volume), however, the comparison becomes more equitable, revealing which designs use material resources more efficiently relative to their geometry. This finding echoes the established use of the shape factor in operational energy assessment and suggests that embodied and operational impacts can be evaluated on a common geometric basis. Looking ahead, integrating the shape factor into embodied impact assessment could support the development of fairer benchmarks under EPBD IV. Although criteria cannot yet be set due to limited data, systematic collection of embodied energy calculations during building permitting or energy certification could provide the necessary dataset. Once a critical mass of cases is available, thresholds could be defined based on the material character of the envelope and structural systems in relation to the building’s geometry.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a simplified method for evaluating the environmental efficiency of family houses during the early design phase, focusing on geometric parameters and their impact on key environmental indicators—primary energy intensity (PENRT), global warming potential (GWP), and acidification potential (AP). The analysis relied on modelled data due to the conceptual nature of the design phase and was also limited to the product stage (A1–A3) of the life cycle, using standardised data and conventional building materials.

Key findings include the following:

Smaller houses exhibit lower absolute environmental impacts, but larger, two-storey houses demonstrate greater efficiency when normalised per square meter of usable floor area (AUF).

Roof shape significantly influences environmental performance, with hip roofs yielding the most favourable results and flat roofs the least.

Floor plan proportions have a minor impact, especially in smaller houses, while the number of floors and built-up area play a more substantial role in determining efficiency.

The relationship between house geometry and environmental indicators is not strictly proportional, emphasising the need for careful design decisions early in the planning process.

These results suggest that environmental efficiency, as measured by “embodied” environmental indicators, should be considered alongside spatial and cultural factors in residential design. While minimising building size is often recommended to reduce emissions, this study highlights that efficiency per unit area may favour larger, well-optimised designs.

The approach presented is based on modelling and covers only stages A1–A3, excluding transportation, installation, replacement, and the end of the life cycle (B–C/D). PENRT/GWP values are sensitive to the choice of database and assumptions about the building system. Future work includes extending the scope to B–C/D and conducting sensitivity and parametric analyses, including the impact of different material combinations.

Finally, this study demonstrates that geometric parameters, and particularly the shape factor, are critical for understanding embodied environmental efficiency in family houses. By extending a concept long used in operational energy certification to embodied impacts assessment, this research highlights a pathway toward fairer comparisons of buildings with different geometries. While regulatory criteria cannot yet be established due to insufficient data, the systematic collection of embodied energy and GWP values, perhaps initially focused on the building envelope, and expressed in relation to the shape factor, could enable the definition of benchmarks in the future. Such an approach would strengthen the implementation of EPBD IV, ensuring that both operational and embodied performance are assessed on a consistent and equitable geometric basis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.P. and R.R.; methodology, R.P., V.S. and R.R.; software, R.P.; validation, R.P., N.M. and M.Ž.; formal analysis, M.Ž. and K.M.; investigation, K.M., I.K., N.M., M.J. and R.P.; resources, R.P., I.K. and R.R.; data curation, R.P., N.M. and M.Ž.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.; writing—review and editing, R.P., R.R. and V.S.; visualisation, R.P. and M.J.; supervision, R.R.; project administration, R.R. and N.M.; funding acquisition, N.M., R.R. and V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the research grant VEGA No. 1/0322/23 of the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Youth and the Slovak Academy of Sciences (Vedecká Grantová Agentúra MŠVVaM SR a SAV).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This article was made possible thanks to VEGA research grant No. 1/0322/23 of the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Youth and the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Volodymyr Semko’s contribution to this work was supported by Poznan University of Technology, grant number 0412/SBAD/0090. The contribution of Katarína Minarovičová and Martin Jamnický was supported by the Cultural and Educational Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Youth of the Slovak Republic (grant KEGA 046STU-4/2025 and KEGA 036STU-4/2025, respectively). Nataliia Mahas was funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under project No. 09I03-03-V01-00036. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to COST Action CA21103—Implementation of the Circular Economy in the Built Environment (CircularB)—for providing invaluable support, facilitating productive discussions and the exchange of information and knowledge, thus enabling the elaboration of this study. COST Action is an initiative of the European Union.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The European Commission’s support for the production of this article does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| PENRT | Primary energy non-renewable total |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| AP | Acidification potential |

| EI | Environmental indicator |

| ABU | Built-up area |

| AUF | Usable floor area |

References

- González, M.J.; García Navarro, J. Assessment of the Decrease of CO2 Emissions in the Construction Field through the Selection of Materials: Practical Case Study of Three Houses of Low Environmental Impact. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, I.; Hestnes, A.G. Energy Use in the Life Cycle of Conventional and Low-Energy Buildings: A Review Article. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour, M.; Belusko, M.; Xing, K.; Bruno, F. Minimising the Life Cycle Energy of Buildings: Review and Analysis. Build. Environ. 2014, 73, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röck, M.; Saade, M.R.M.; Balouktsi, M.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Birgisdottir, H.; Frischknecht, R.; Habert, G.; Lützkendorf, T.; Passer, A. Embodied GHG Emissions of Buildings—The Hidden Challenge for Effective Climate Change Mitigation. Appl. Energy 2020, 258, 114107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lützkendorf, T.; Balouktsi, M. Embodied Carbon Emissions in Buildings: Explanations, Interpretations, Recommendations. Build. Cities 2022, 3, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noro, M.; Busato, F. Energy Saving, Energy Efficiency or Renewable Energy: Which Is Better for the Decarbonization of the Residential Sector in Italy? Energies 2023, 16, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movlyanov, A.; Selçuklu, S.B. Energy Efficiency Optimization Model for Sustainable Campus Buildings and Transportation. Buildings 2025, 15, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwińska-Małajowicz, A.; Pyrek, R.; Szczotka, K.; Szymiczek, J.; Piecuch, T. Improving the Energy Efficiency of Public Utility Buildings in Poland through Thermomodernization and Renewable Energy Sources—A Case Study. Energies 2023, 16, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarovičová, K.; Rabenseifer, R. Environmental Analysis and a Suggestion for Assessment of Detached Houses. Int. Rev. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2013, 4, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2024/1275 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, L 2024/1275. 8 May 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Rabenseifer, R.; Hraška, J.; Borovská, E.; Babenko, M.; Hanuliak, P.; Vacek, Š. Sustainable Building Policies in Central Europe: Insights and Future Perspectives. Energies 2022, 15, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarnezhad, A.; Xiao, J. Estimation and Minimization of Embodied Carbon of Buildings: A Review. Buildings 2017, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazieschi, G.; Asdrubali, F.; Thomas, G. Embodied Energy and Carbon of Building Insulating Materials: A Critical Review. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Miralles, J.A.; Hermoso-Orzáez, M.J.; Martínez-García, C.; Rojas-Sola, J.I. Comparative Study on the Environmental Impact of Traditional Clay Bricks Mixed with Organic Waste Using Life Cycle Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Moncaster, A. Embodied Carbon, Embodied Energy and Renewable Energy: A Review of Environmental Product Declarations. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Struct. Build. 2023, 176, 986–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Pinheiro, M.D.; De Brito, J.; Mateus, R. Embodied vs. Operational Energy and Carbon in Retail Building Shells: A Case Study in Portugal. Energies 2022, 16, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Joint Research Centre; Gervasio, H.; Dimova, S. Environmental Benchmarks for Buildings: EFIResources: Resource Efficient Construction towards Sustainable Design; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Železná, J.; Felicioni, L.; Trubina, N.; Vlasatá, B.; Růžička, J.; Veselka, J. Whole Life Carbon Assessment of Buildings: The Process to Define Czech National Benchmarks. Buildings 2024, 14, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozan, B.; Olsen, C.O.; Sørensen, C.G.; Kragh, J.; Rose, J.; Aggerholm, S.; Birgisdottir, H. Klimapåvirkning fra Nybyggeri: Analytisk Grundlag til Fastlæggelse af ny LCA Baseret Grænseværdi for Bygningers Klimapåvirkning fra 2025 (Climate Impact of New Buildings: Analytical Basis for Determining New LCA-Based Limit Values for the Climate Impact of Buildings from 2025). (1 udg.) Institut for Byggeri, By og Miljø (BUILD), Aalborg Universitet. BUILD Rapport Bind 2023 Nr. 21. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/da/publications/klimap%C3%A5virkning-fra-nybyggeri-analytisk-grundlag-til-fastl%C3%A6ggelse/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Szalay, Z. A Parametric Approach for Developing Embodied Environmental Benchmark Values for Buildings. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 1563–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucińska, J.; Komerska, A.; Kwiatkowski, J. Preliminary Study on the GWP Benchmark of Office Buildings in Poland Using the LCA Approach. Energies 2020, 13, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabenseifer, R.; Kalivodová, M.; Kononets, Y.; Mahas, N.; Minarovičová, K.; Provazník, R.; Bordun, M.; Shekhorkina, S.; Savytskyi, M.; Savytskyi, O.; et al. How Much Is Needed? Discussion on Benchmarks for Primary Energy Input and Global Warming Potential Caused by Building Construction. Energies 2025, 18, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de la Transition Écologique (MTE/CEREMA). Guide RE2020—Réglementation Environnementale des Bâtiments neufs (Environmental Regulations for New Buildings). Available online: https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/documents/guide_re2020.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Danish Ministry of the Interior and Housing. National Strategy for Sustainable Construction: Introduction of Life Cycle Assessment and Carbon Limit Values. Available online: https://bygningsreglementet.dk (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Nordic Sustainable Construction. Danish Political Agreement Tightens the Limit Values for New Buildings and Extends the Impact. Available online: https://www.nordicsustainableconstruction.com/news/2024/june/tillaegsaftale-paa-engelsk (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Nwodo, M.N.; Anumba, C.J. A Review of Life Cycle Assessment of Buildings Using a Systematic Approach. Build. Environ. 2019, 162, 106290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathna, D.; Bunster, V.; Graham, P. A Review of Building Life Cycle Assessment Software Tools: Challenges and Future Directions. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1363, 012063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fnais, A.; Rezgui, Y.; Petri, I.; Beach, T.; Yeung, J.; Ghoroghi, A.; Kubicki, S. The Application of Life Cycle Assessment in Buildings: Challenges, and Directions for Future Research. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 627–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, R.; Abbasabadi, N. Embodied Energy of Buildings: A Review of Data, Methods, Challenges, and Research Trends. Energy Build. 2018, 168, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmqvist, T.; Glaumann, M.; Scarpellini, S.; Zabalza, I.; Aranda, A.; Llera, E.; Díaz, S. Life Cycle Assessment in Buildings: The ENSLIC Simplified Method and Guidelines. Energy 2011, 36, 1900–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soust-Verdaguer, B.; Llatas, C.; García-Martínez, A. Simplification in Life Cycle Assessment of Single-Family Houses: A Review of Recent Developments. Build. Environ. 2016, 103, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozan, B.; Nielsen, L.H.; Hoxha, E.; Birgisdóttir, H. Mitigating Carbon Emissions of Single-Family Houses: Assessing the Need for a Limit Value. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2600, 152019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Příleský, M. Zásady a Pravidla Územního Plánování—Koncepce Funkčních Složek, Část 3.4. Bydlení. 1. (Principles and Rules of Spatial Planning—Concept of Functional Components, Section 3.4. Housing. 1.); VÚVA, URBION: Brno, Czech Republic, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Neufert, E.; Neufert, P.; Neufert, E. Navrhování Staveb: Základy, Normy, Předpisy o Zakládání, Stavbĕ, o Nárocích na Prostor, Návrhy na Prostorové Vztahy, na Rozmĕry Budov, Místnosti, Zarĭzení, na Přístroj°u z Hlediska Človĕka Jako Mĕřítka a Cíle; Příručka pro Stavebního Odborníka, Stavebníka, Vyucŭjícího a Studenta (Building Design: Fundamentals, Standards, Regulations on Foundations, Construction, Space Requirements, Proposals for Spatial Relationships, Building Dimensions, Rooms, Equipment, and Appliances from a Human Perspective as a Benchmark and Goal; a Handbook for Construction Professionals, Builders, Teachers, and Students); na Přístroje; 33. completely revised ed.; Nakladatelství Consultinvest: Praha, Czech Republic, 1995; ISBN 978-80-901486-4-2. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolitan Institute of Bratislava. Územný Plán Hlavného Mesta SR Bratislavy v Znení Schválených Zmien a Doplnkov 01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 06 a 07. Zmeny a Doplnky 08. (The Zoning Plan of the Capital City of the Slovak Republic, Bratislava, as Amended by Approved Amendments and Supplements 01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 06, and 07. Amendments and Supplements 08.); Metropolitan Institute of Bratislava: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- STN EN 15804+A2+AC; Trvalá Udržateľnosť Výstavby. Environmentálne Vyhlásenia o Produktoch. Základné Pravidlá Skupiny Stavebných Produktov. (Sustainability of Construction Works. Environmental Product Declarations. Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products). Úrad Pre Normalizáciu, Metrológiu a Skúšobníctvo Slovenskej Republiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023.

- Röck, M.; Balouktsi, M.; Ruschi Mendes Saade, M. Embodied Carbon Emissions of Buildings and How to Tame Them. One Earth 2023, 6, 1458–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STN 73 0540-2+Z1+Z2; Tepelná Ochrana Budov. Tepelnotechnické Vlastnosti Stavebných Konštrukcií a Budov. Časť 2 Funkčné Požiadavky. Konsolidované Znenie. (Thermal Protection of Buildings. Thermal Performance of Buildings and Components. Part 2: Functional Requirements). Úrad Pre Normalizáciu, Metrológiu a Skúšobníctvo Slovenskej Republiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019.

- ÖKOBAUDAT. Standardized Database for Ecological Evaluations of Buildings. 2023. Available online: https://www.oekobaudat.de (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Sphera Solutions GmbH. GaBi Life Cycle Assessment Databases (Managed LCA Content); Sphera Solutions GmbH: Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://lcadatabase.sphera.com/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

Figure 1.

A list of the investigated samples, with schemes, basic parameters, and labelling.

Figure 1.

A list of the investigated samples, with schemes, basic parameters, and labelling.

Figure 2.

A comparison of environmental indicators (PENRT, GWP, AP) for all samples, normalised by the usable floor area (AUF). The results illustrate the influence of geometry (floor area, proportions, number of storeys, and roof type) on embodied impacts.

Figure 2.

A comparison of environmental indicators (PENRT, GWP, AP) for all samples, normalised by the usable floor area (AUF). The results illustrate the influence of geometry (floor area, proportions, number of storeys, and roof type) on embodied impacts.

Figure 3.

Significant values of environmental indicators (EI) per 1m2 of usable floor area AUF for selected samples.

Figure 3.

Significant values of environmental indicators (EI) per 1m2 of usable floor area AUF for selected samples.

Figure 4.

The correlation between primary energy from non-renewable sources (PENRT/m2, primary y-axis) and the shape factor (envelope area to heated volume, secondary y-axis) for all building variants with different roof types: (a) flat roof, (b) hip roof, (c) gable roof with 30° inclination, and (d) gable roof with 45° inclination. The results show that as building size increases, the shape factor decreases, and the relative environmental burden per square meter decreases, confirming the efficiency advantage of more compact, multi-storey designs.

Figure 4.

The correlation between primary energy from non-renewable sources (PENRT/m2, primary y-axis) and the shape factor (envelope area to heated volume, secondary y-axis) for all building variants with different roof types: (a) flat roof, (b) hip roof, (c) gable roof with 30° inclination, and (d) gable roof with 45° inclination. The results show that as building size increases, the shape factor decreases, and the relative environmental burden per square meter decreases, confirming the efficiency advantage of more compact, multi-storey designs.

Figure 5.

The correlation between the global warming potential (GWP/m2, primary y-axis) and shape factor (envelope area to heated volume, secondary y-axis) for all building variants with different roof types: (a) flat roof, (b) hip roof, (c) gable roof with 30° inclination, and (d) gable roof with 45° inclination. The graphs underline that larger, more compact geometries achieve lower relative impacts, while roof form further modulates performance, with hip roofs generally yielding the most favourable results.

Figure 5.

The correlation between the global warming potential (GWP/m2, primary y-axis) and shape factor (envelope area to heated volume, secondary y-axis) for all building variants with different roof types: (a) flat roof, (b) hip roof, (c) gable roof with 30° inclination, and (d) gable roof with 45° inclination. The graphs underline that larger, more compact geometries achieve lower relative impacts, while roof form further modulates performance, with hip roofs generally yielding the most favourable results.

Table 1.

The composition of the external load-bearing wall and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 1.

The composition of the external load-bearing wall and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i001 Energies 19 00161 i001]() | Lime–cement plaster: 20 mm

Hollow clay bricks: 250 mm

Mineral glue: 5 mm

EPS insulation: 220 mm

Reinforced base layer: 3 mm

Silicate plaster: 2 mm | 0.505 | 0.15 | 228.55 | 57.17 | 0.0023 |

Table 2.

The composition of the flat roof and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 2.

The composition of the flat roof and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i002 Energies 19 00161 i002]() | Lime–cement plaster: 20 mm

Reinf. concrete slab: 250 mm

PE foil

EPS insulation: 240 mm

PP geotextile

PVC-P membrane

Gravel: 50 mm | 0.565 | 0.15 | 311.09 | 94.08 | 0.0040 |

Table 3.

The composition of pitched and hip roofs and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 3.

The composition of pitched and hip roofs and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i003 Energies 19 00161 i003]() | Plasterboard + lime–cement plaster: 45 mm

Lath + glass wool

insulation: 40 mm

Vapour barrier foil

OSB3 chipboard: 15 mm

Rafters + glass wool

insulation: 160 mm

Lath + glass wool

insulation: 40 mm

Spruce boards: 20 mm

Open diffusion roofing sheet

lath, cross lathing: 40 mm

Clay tiles: 50 mm | 0.450 | 0.15 | 227.51 | −16.35 | 0.0050 |

Table 4.

The composition of the ground floor and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 4.

The composition of the ground floor and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i004 Energies 19 00161 i004]() | Wooden parquet + glue: 20 mm

Cement screed: 50 mm

PE foil

Stone wool acoustic ins.: 20 mm

EPS insulation: 70 mm

PE foil

Polymer–bitumen waterproof

Reinforced concrete

slab: 300 mm

PE foil

Gravel + geotextile: 15 mm | 0.480 | 2.68 | 364.42 | 103.28 | 0.0078 |

Table 5.

The composition of the internal load-bearing wall and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 5.

The composition of the internal load-bearing wall and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i005 Energies 19 00161 i005]() | Lime–cement plaster: 25 mm

Hollow clay bricks: 250 mm

Lime–cement plaster: 25 mm | 0.3 | - | 112.93 | 45.67 | 0.0015 |

Table 6.

The composition of the internal partition wall and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 6.

The composition of the internal partition wall and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i006 Energies 19 00161 i006]() | Lime–cement plaster: 25 mm

Hollow clay bricks: 80 mm

Lime-cement plaster: 25 mm | 0.13 | - | 57.21 | 26.46 | 0.001 |

Table 7.

The composition of the ceiling and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 7.

The composition of the ceiling and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i007 Energies 19 00161 i007]() | Wooden parquets + glue:

20 mm

Cement screed: 50 mm

PE foil

Stone wool acoustic ins.: 20 mm

Reinforced conc. slab: 200 mm

Lime–cement plaster: 20 mm | 0.31 | - | 165.04 | 64.7 | 0.0055 |

Table 8.

The composition of the window and the values of selected environmental indicators.

Table 8.

The composition of the window and the values of selected environmental indicators.

| Display | Component Composition from Interior to Exterior | Thickness

[m] | U-Value

[W/(m2K)] | PENRTi | GWPi | APi |

|---|

![Energies 19 00161 i008 Energies 19 00161 i008]() | Plastic window frame

Triple insulating glass + argon filling | - | 1.00 | 306.09 | 78.24 | 0.0102 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |