Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of CO2 Migration and Pressure Propagation Considering Molecular Diffusion and Geochemical Reactions in Shale Oil Reservoirs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Simulation

2.1. Flow Governing Equation

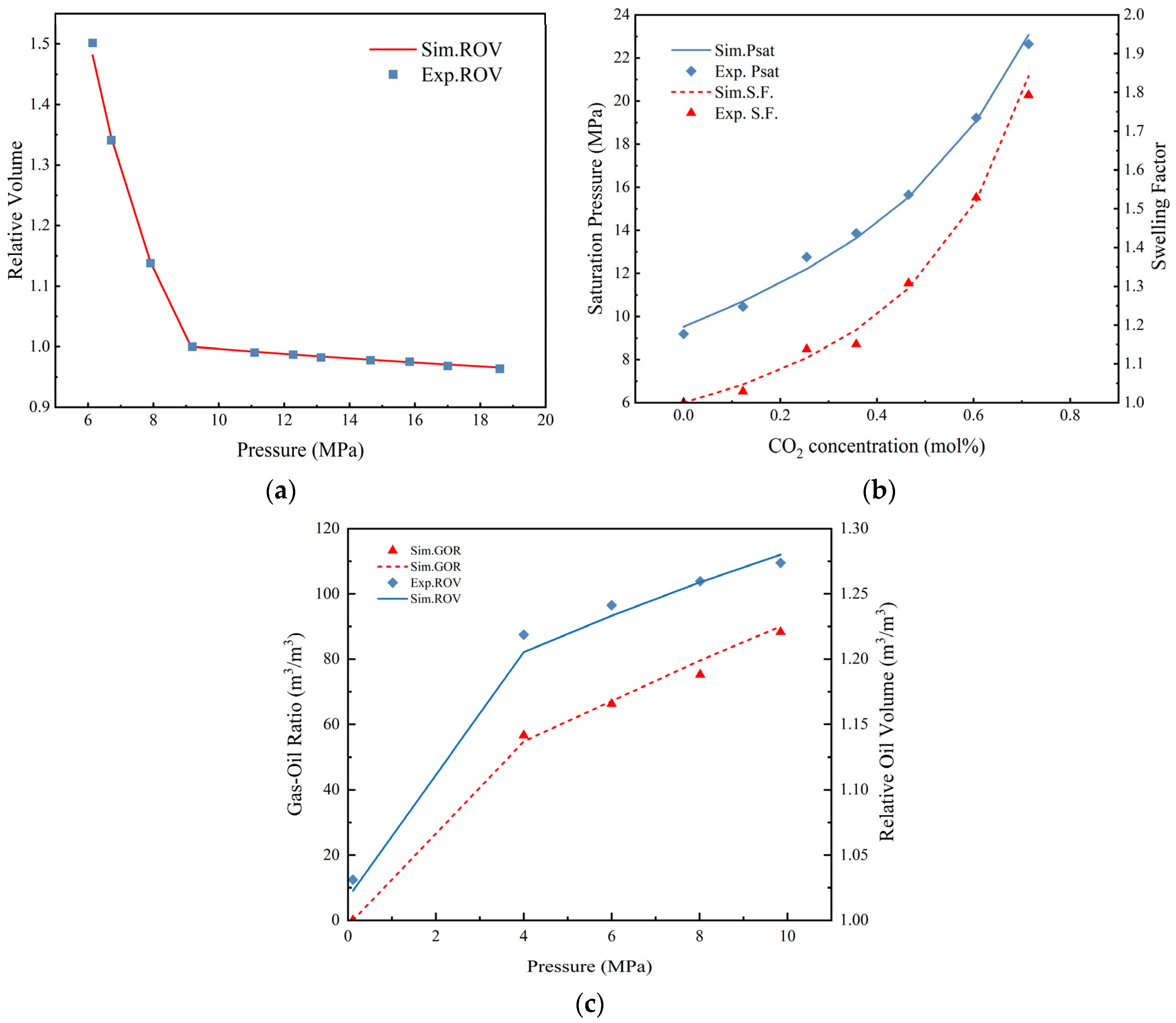

2.2. Reservoir and Fluid Characterization

2.3. Simulation Schedule

3. Results

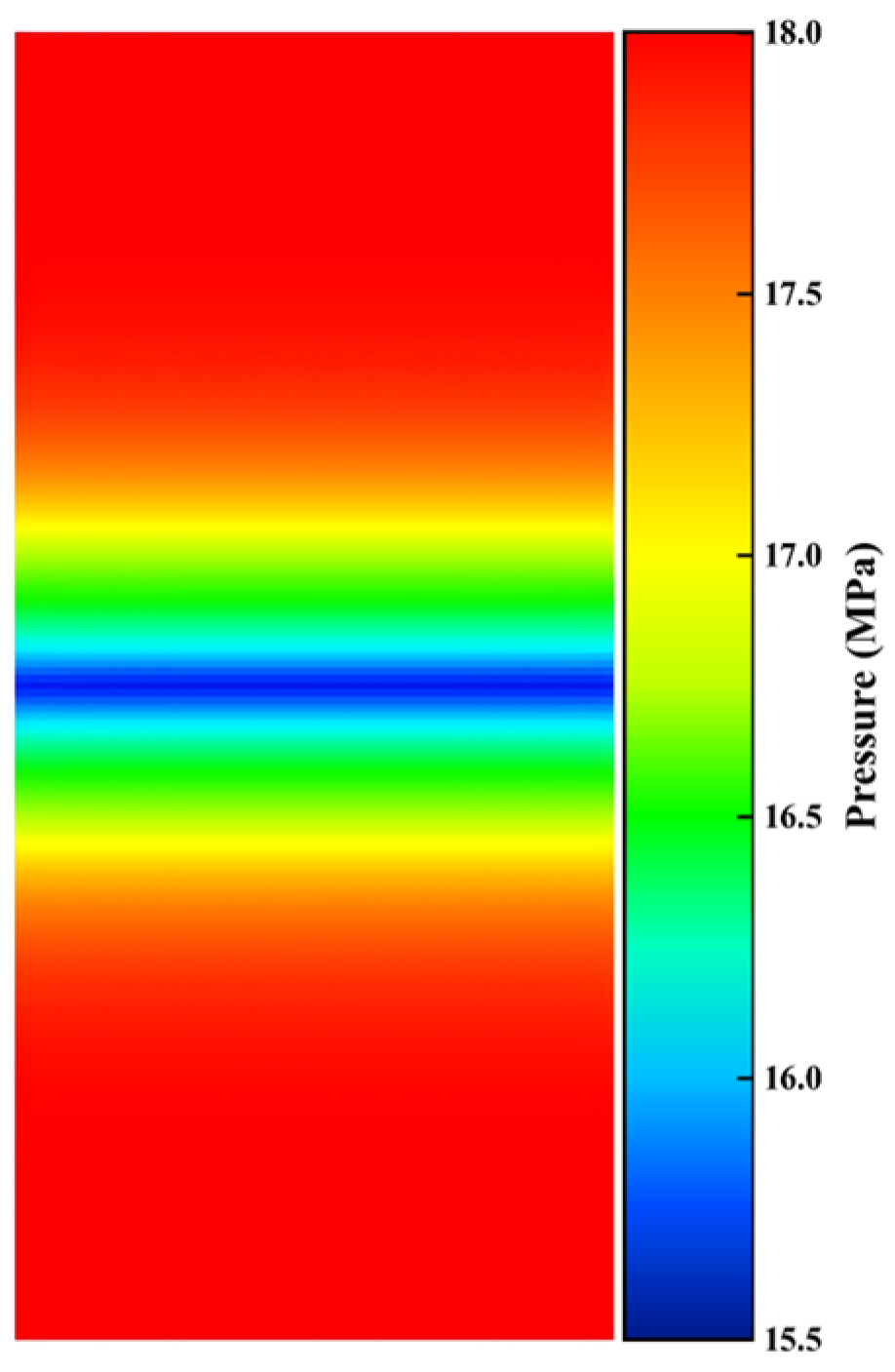

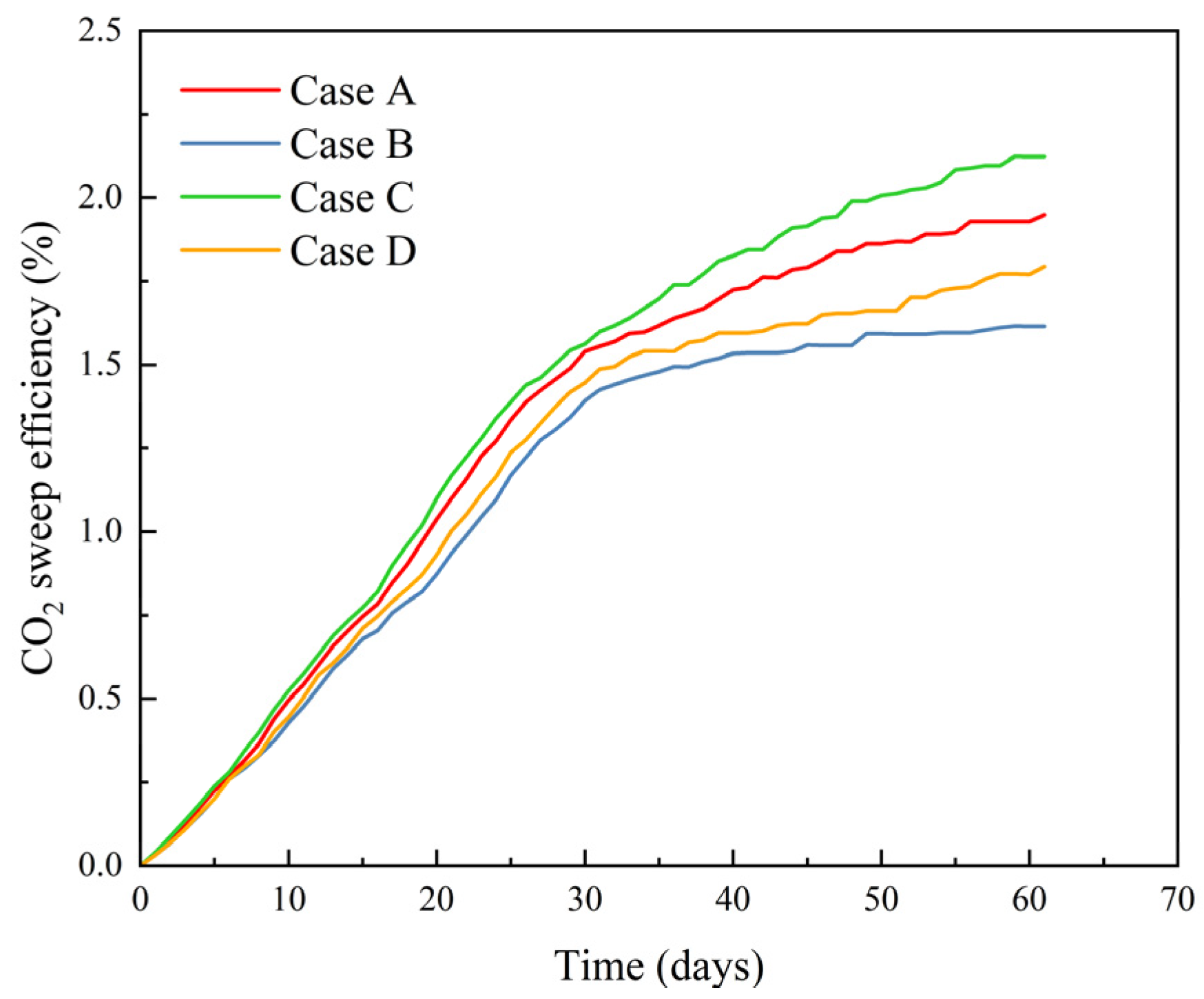

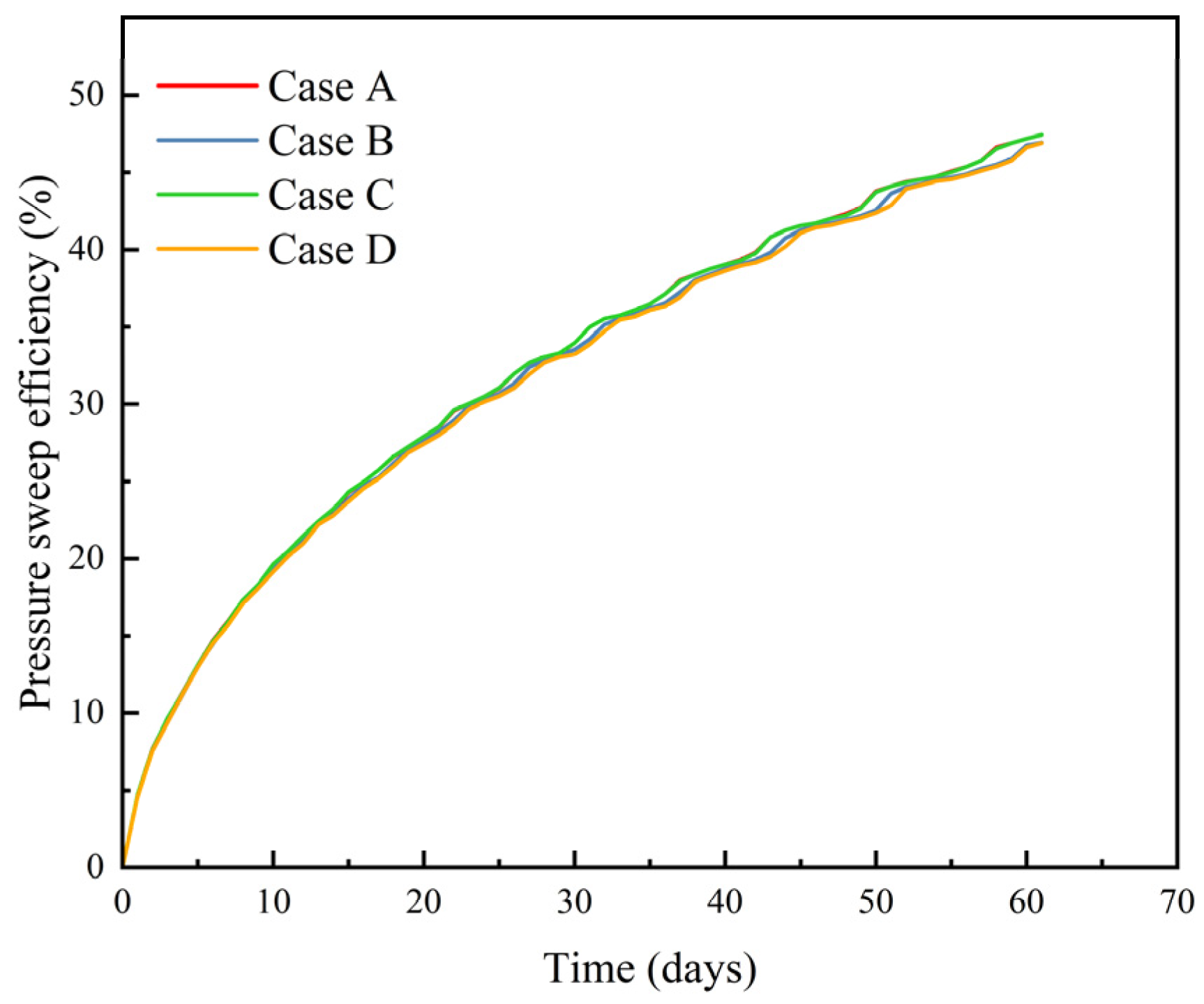

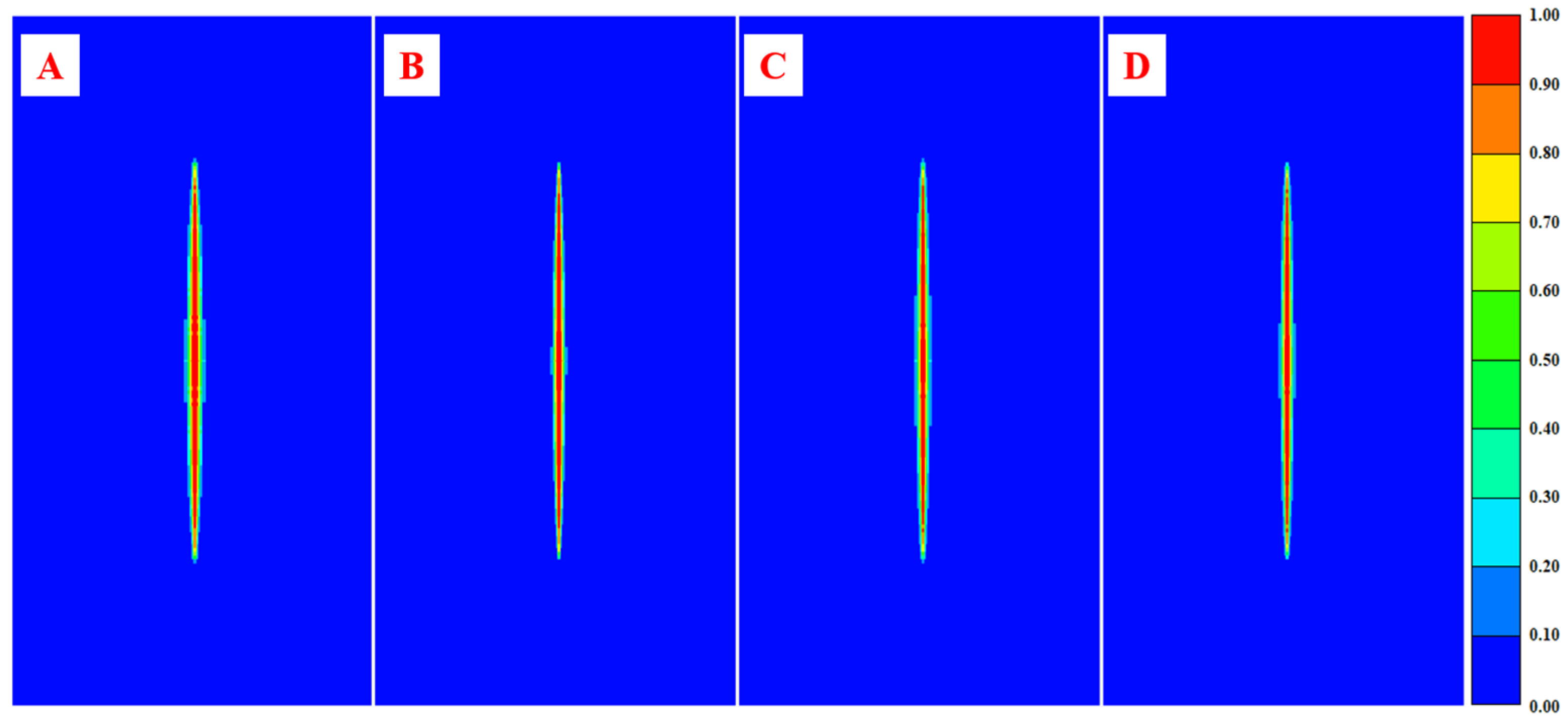

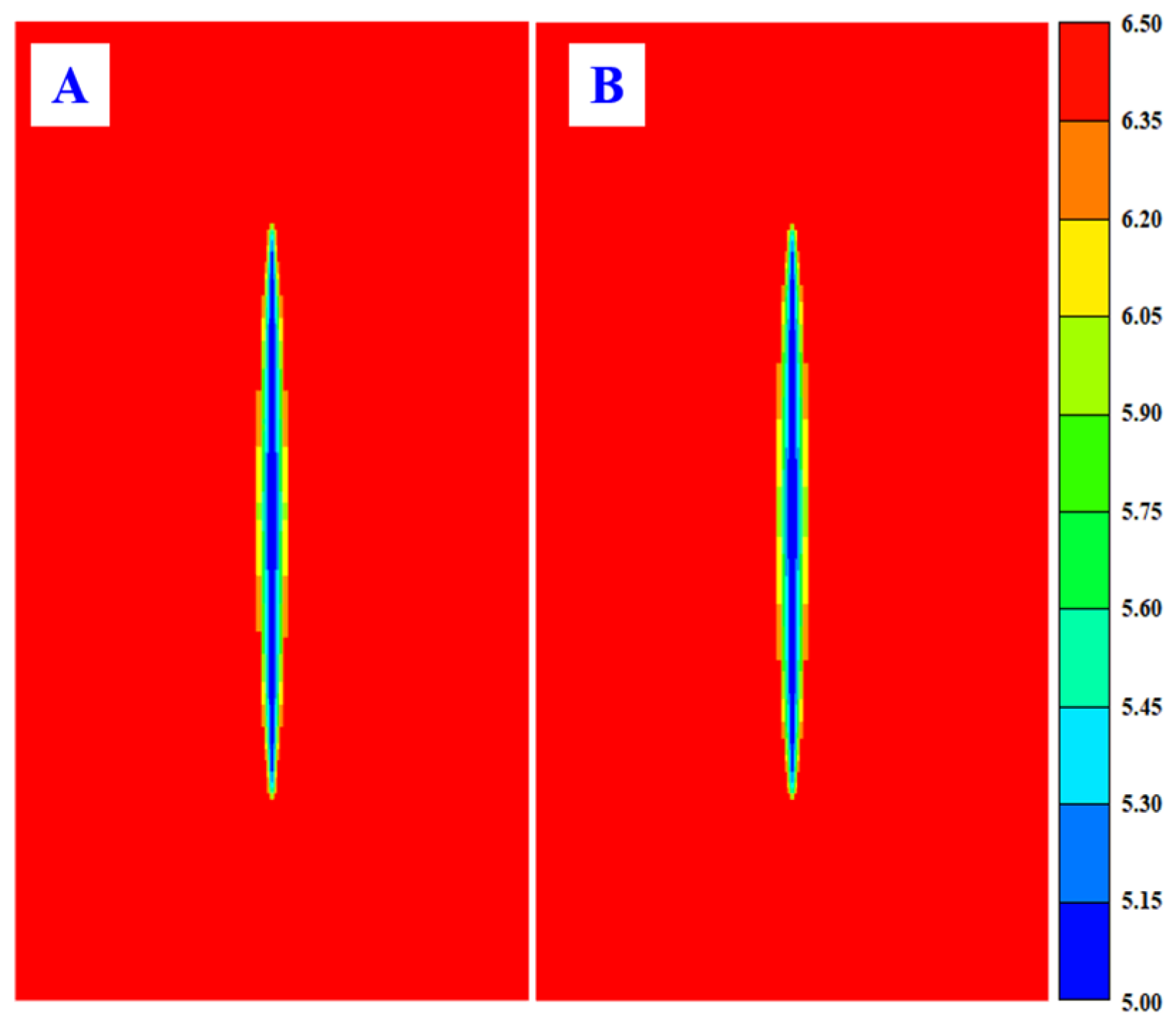

3.1. Effect of Molecular Diffusion and Geochemical Reactions

3.2. Effect of Reservoir and Operational Parameters

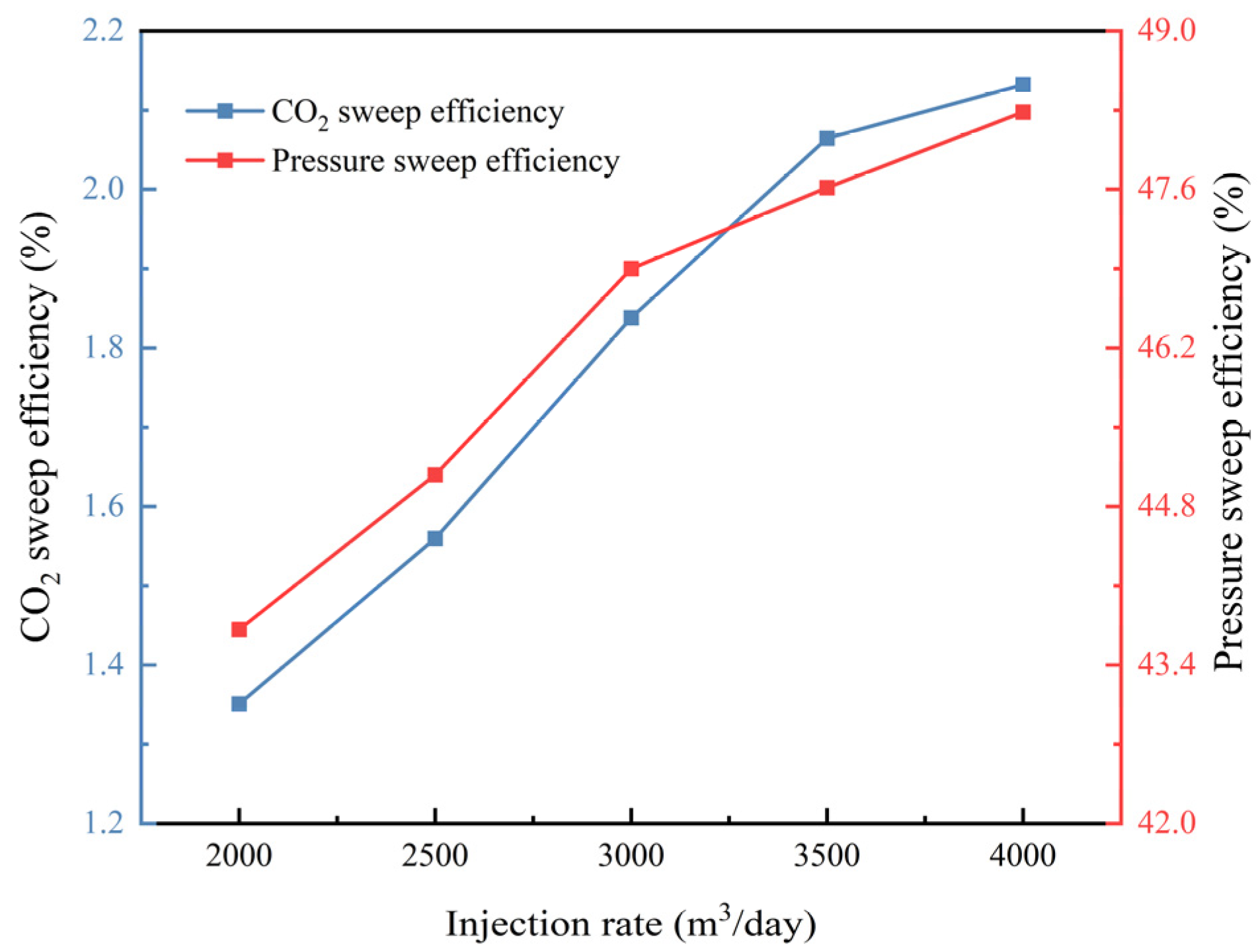

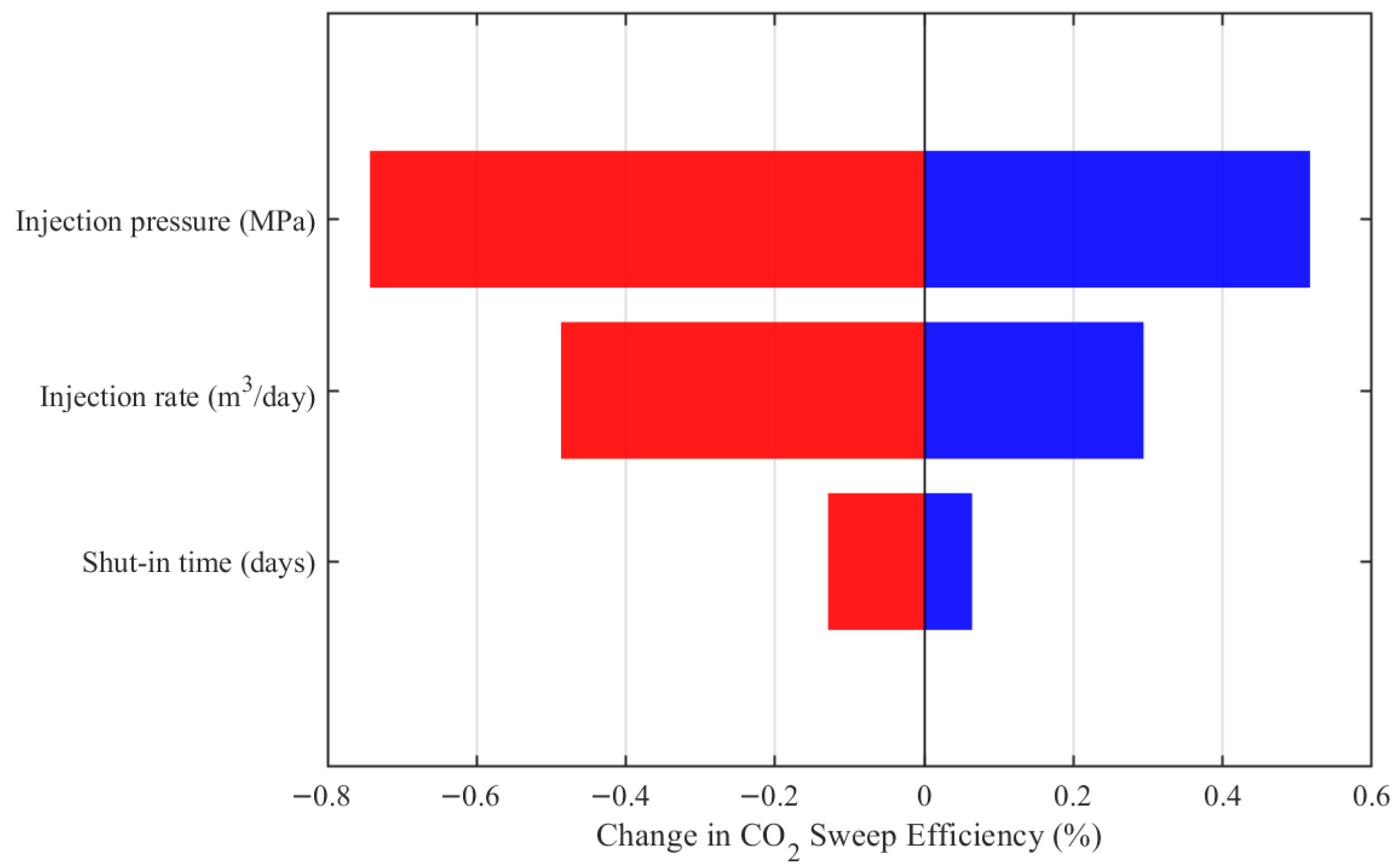

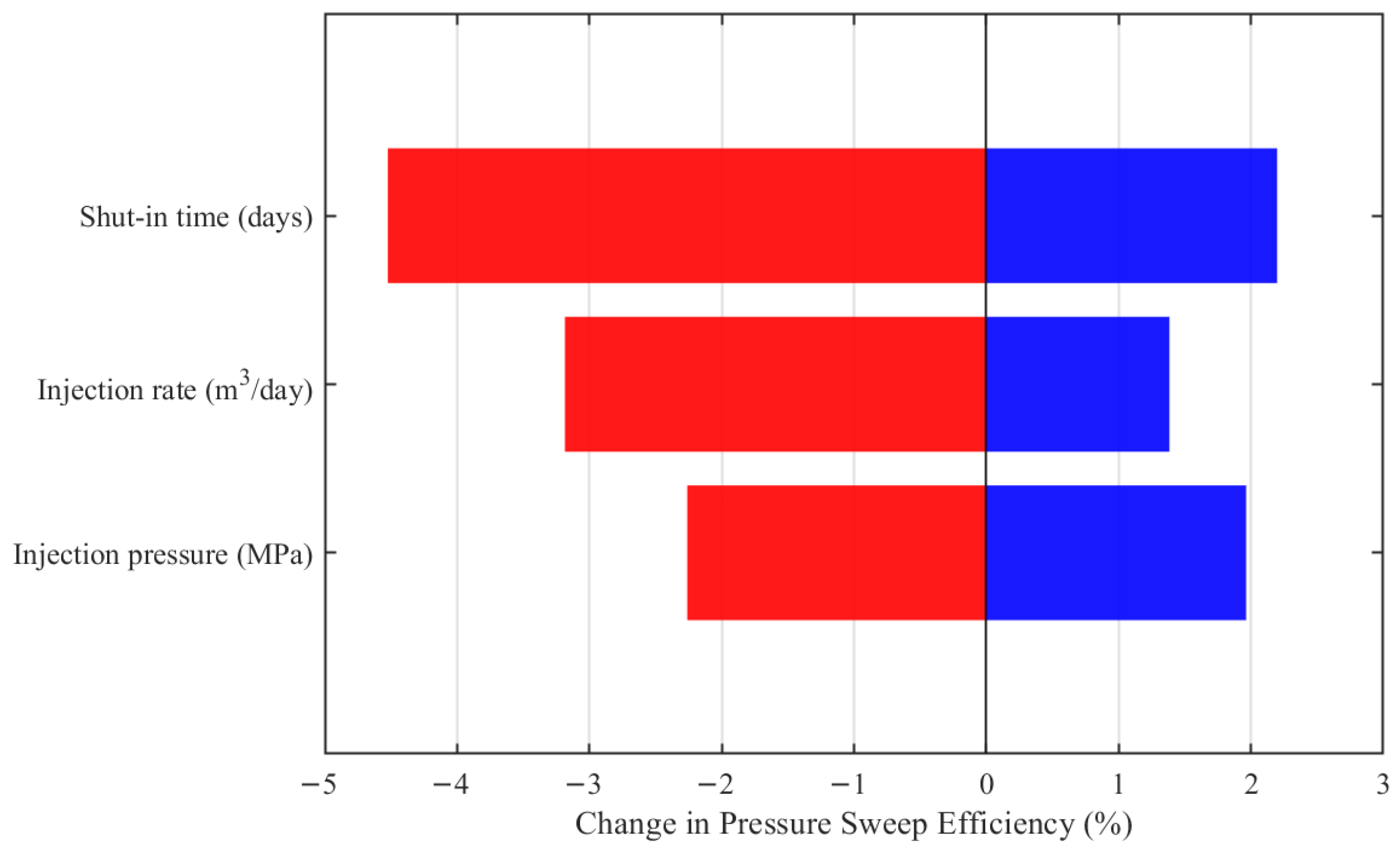

3.2.1. Injection Rate

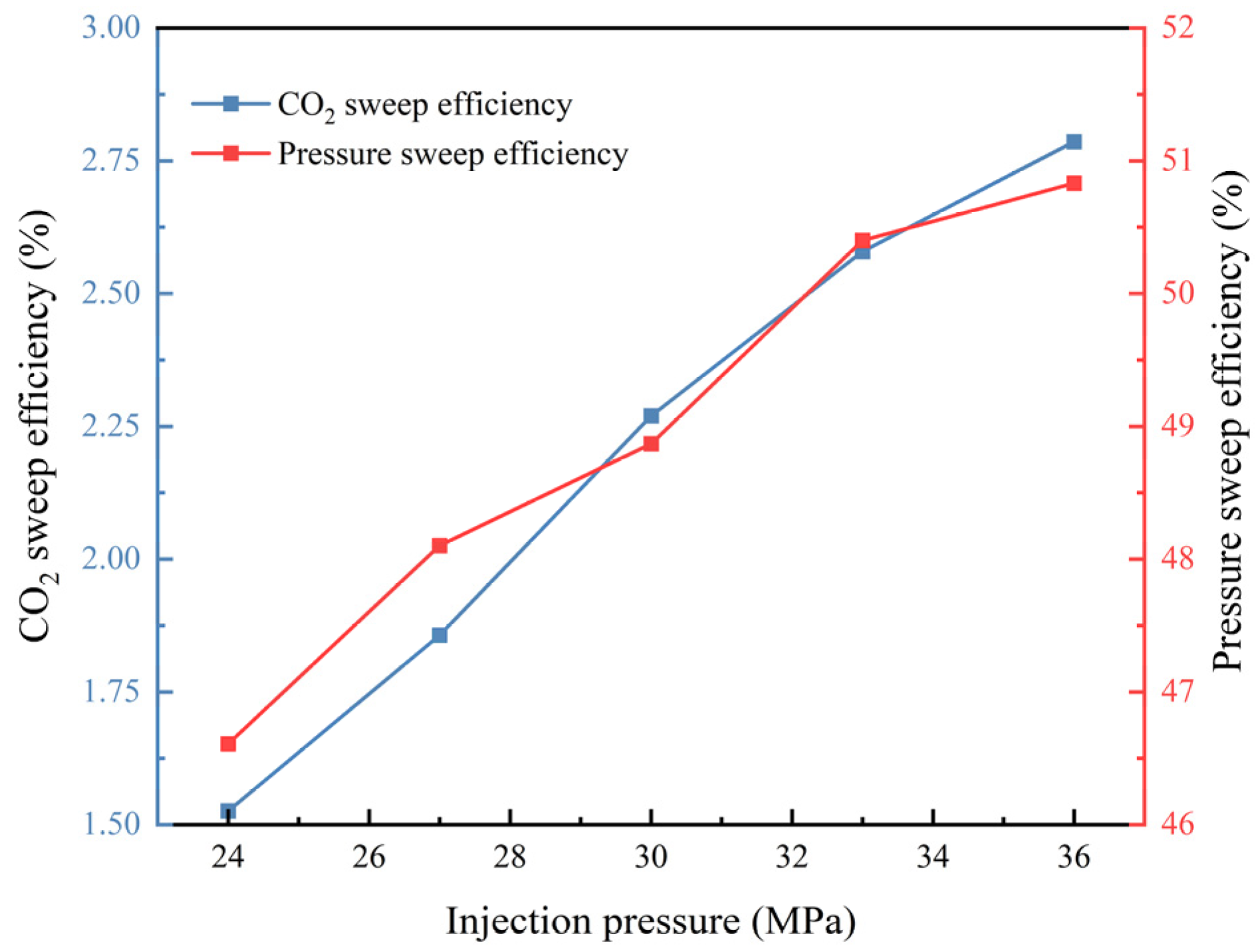

3.2.2. Injection Pressure

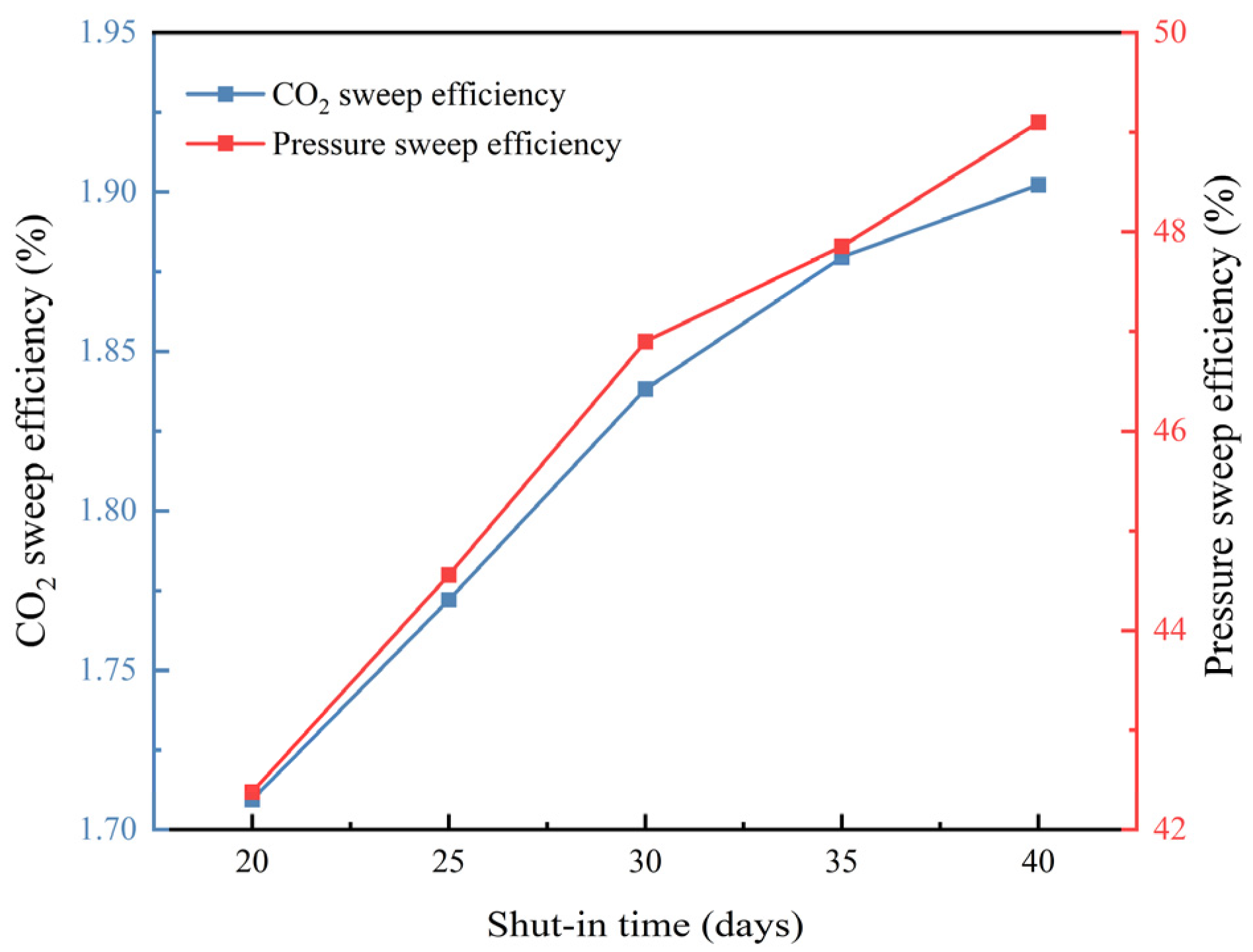

3.2.3. Shut-In Time

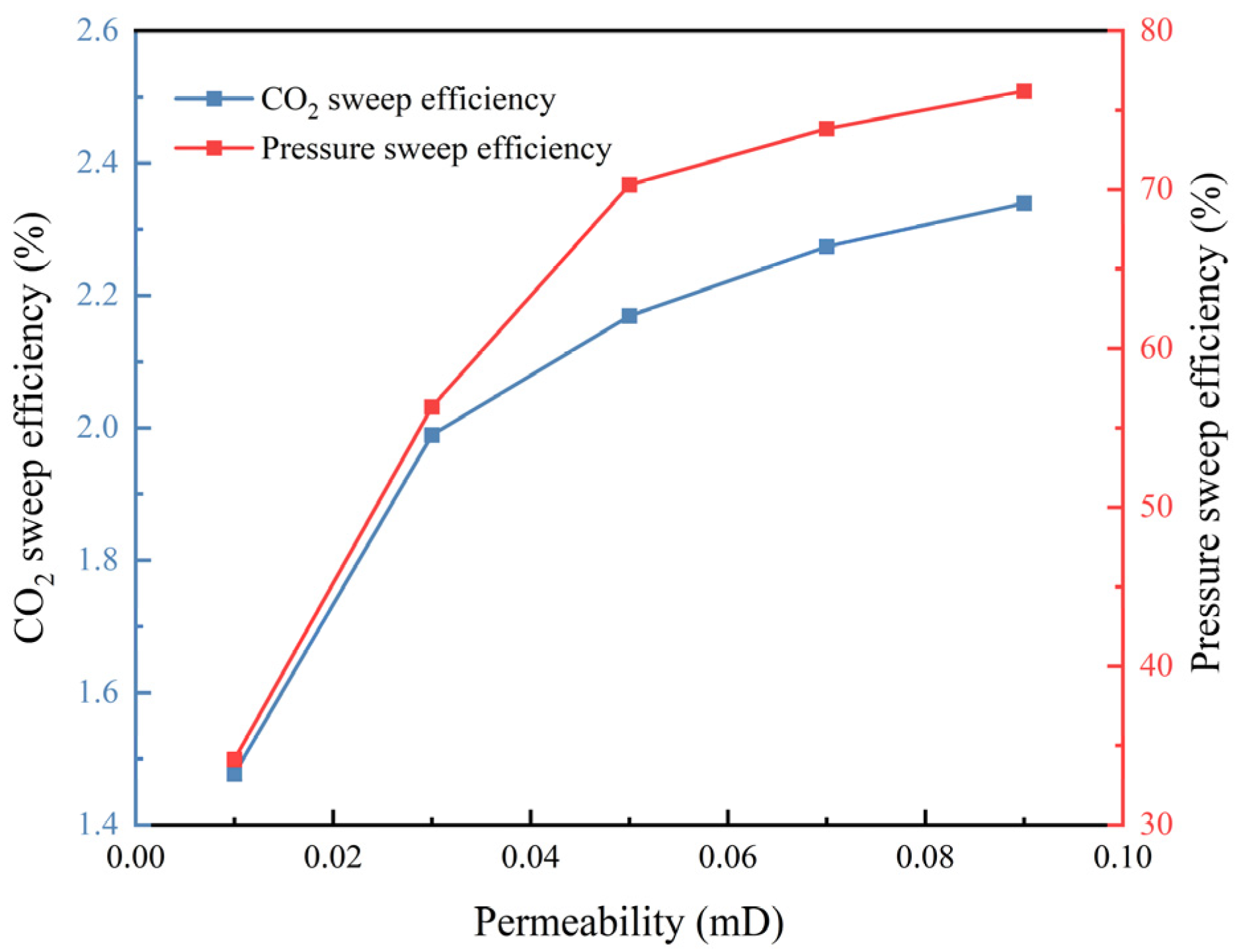

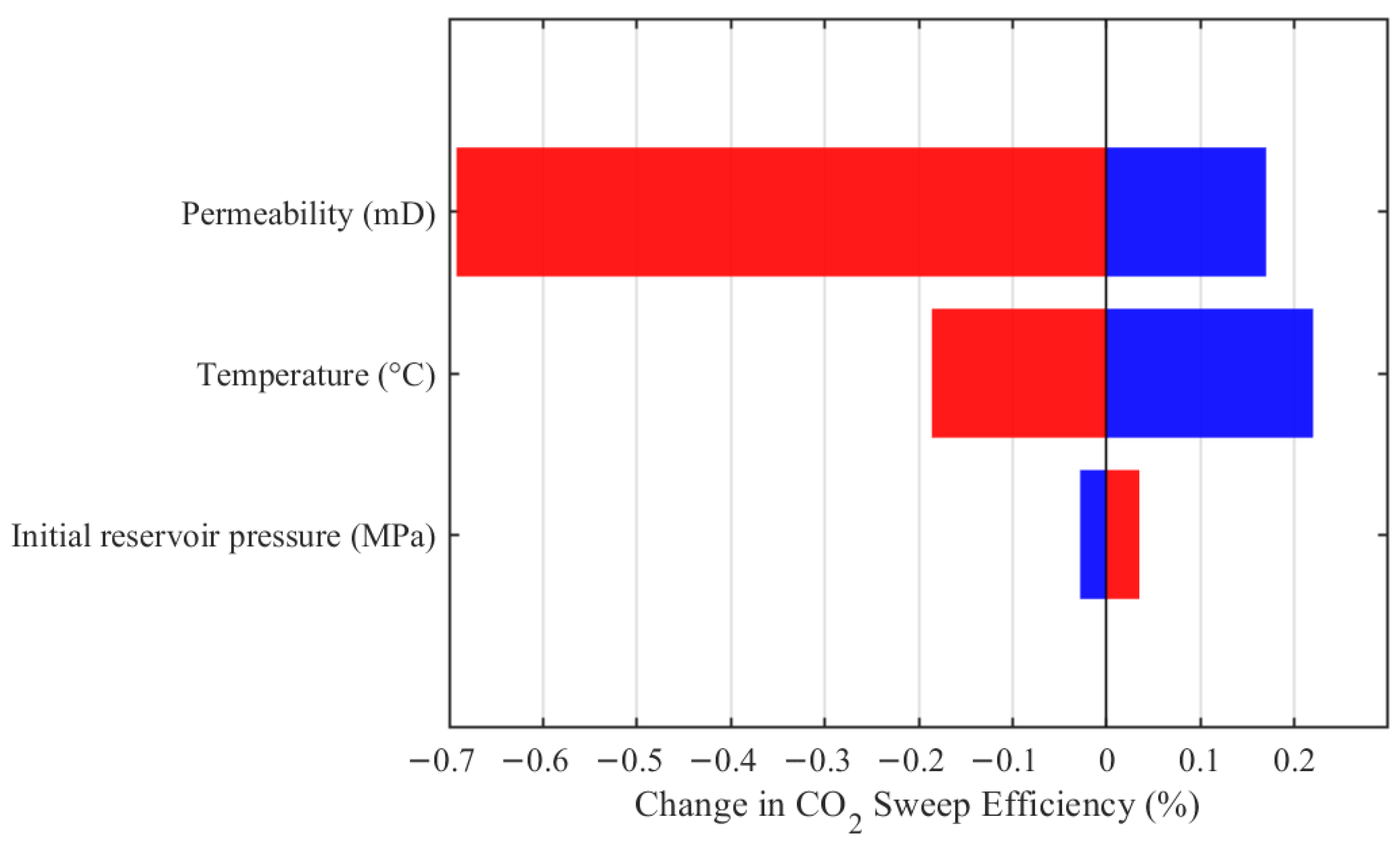

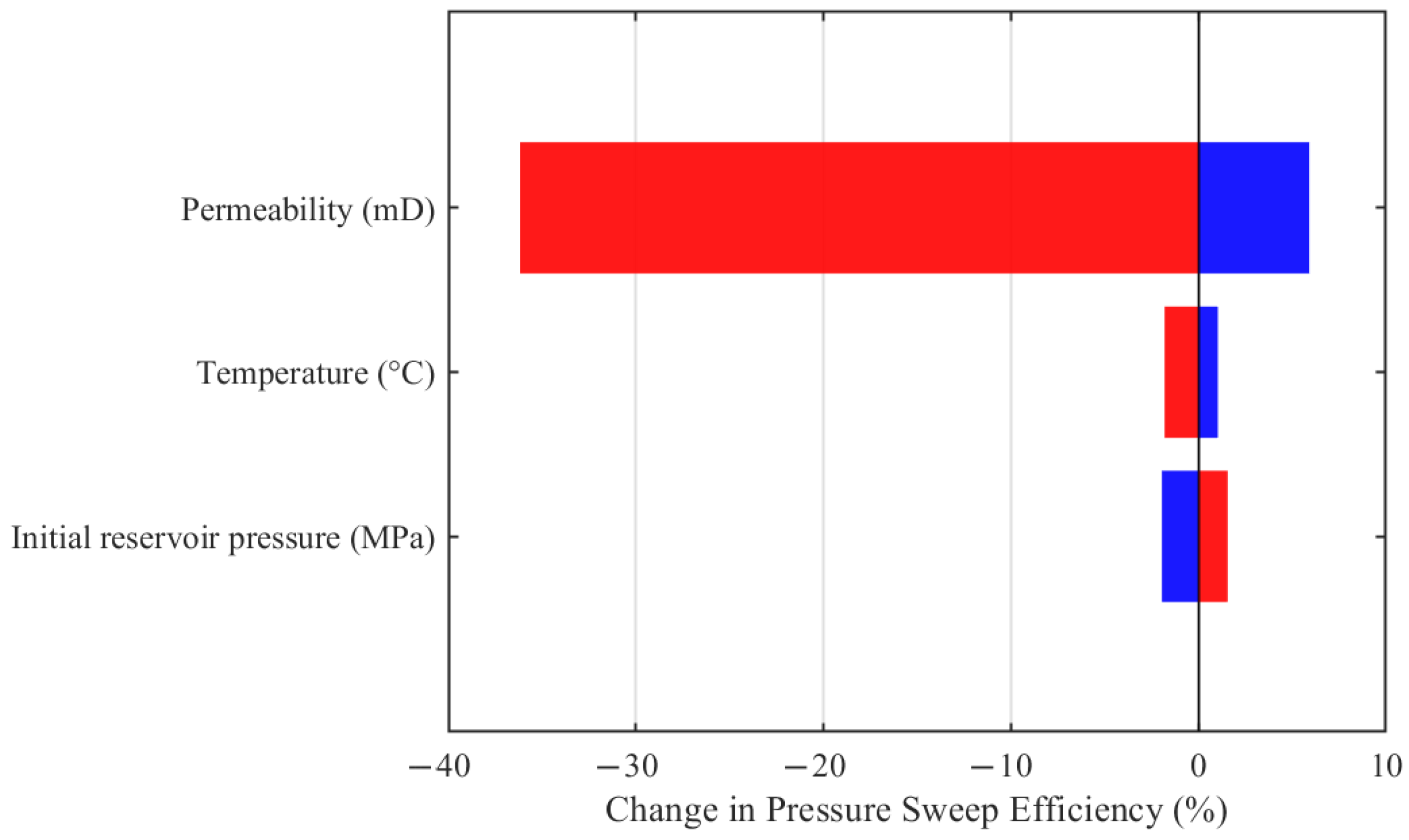

3.2.4. Permeability

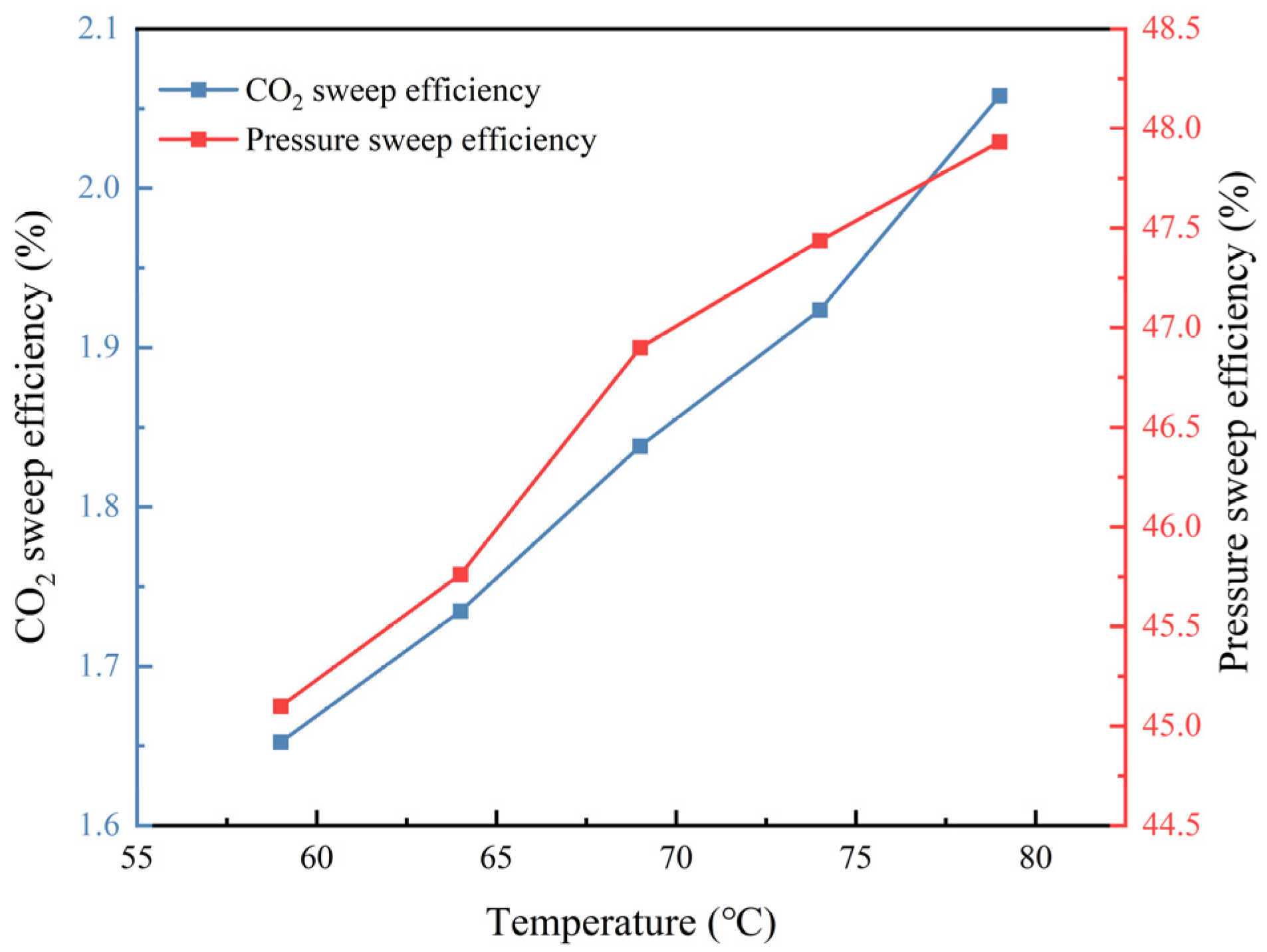

3.2.5. Temperature

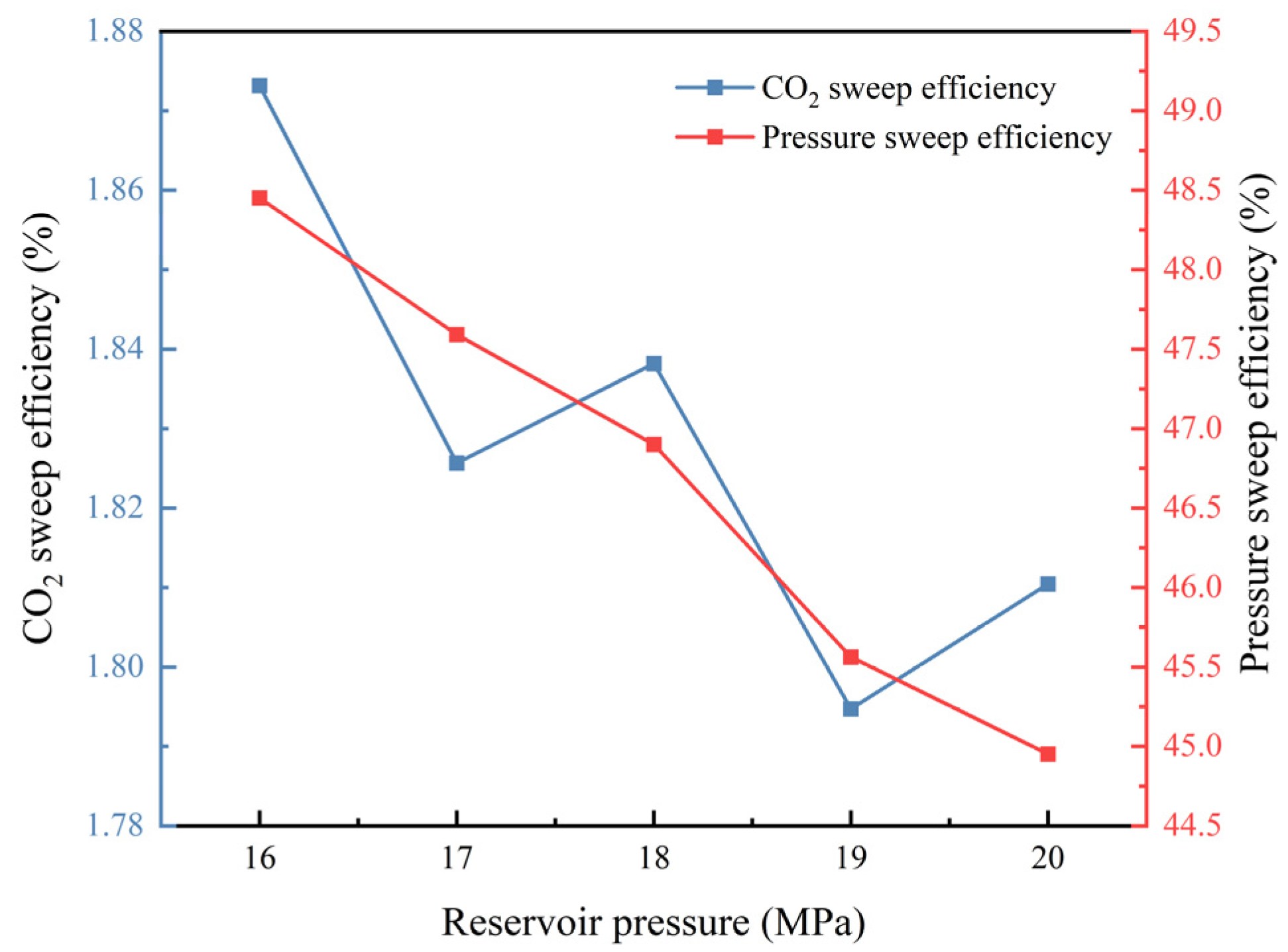

3.2.6. Initial Reservoir Pressure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Compared with convection alone, molecular diffusion increases the final CO2 sweep efficiency by approximately 1.7%, whereas geochemical reactions consistently suppress the CO2 sweep efficiency, reducing it by about 0.3% and further widening the gap during the soaking stage. When diffusion and reactions coexist, the positive effect of molecular diffusion is partially offset, resulting in a reduction of approximately 0.2% in the final CO2 sweep efficiency compared with the diffusion-only case.

- At the scale of this study, the simulation results show that after 60 days of CO2 injection and soaking following hydraulic fracturing, the maximum difference among the four mechanisms is only 0.5%. This indicates that the effects of molecular diffusion and geochemical reactions on pressure propagation are negligible.

- The results indicate that, for CO2-EOR following hydraulic fracturing, injection pressure and reservoir permeability constitute the primary controlling factors governing CO2 sweep efficiency and energy utilization, whereas shut-in duration and reservoir temperature play secondary roles and should be considered as auxiliary parameters in adaptive design. The specific optimal values of these parameters are reservoir-dependent and require site-specific calibration.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bui, M.; Adjiman, C.S.; Bardow, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Boston, A.; Brown, S.; Fennell, P.S.; Fuss, S.; Galindo, A.; Hackett, L.A.; et al. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS): The Way Forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Yao, Z. A State-of-the-Art Review of CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery as a Promising Technology to Achieve Carbon Neutrality in China. Environ. Res. 2022, 210, 112986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, E.; He, W. The Development and Utilization of Shale Oil and Gas Resources in China and Economic Analysis of Energy Security Under the Background of Global Energy Crisis. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 2315–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.G.; Reed, R.M.; Ruppel, S.C.; Jarvie, D.M. Morphology, Genesis, and Distribution of Nanometer-Scale Pores in Siliceous Mudstones of the Mississippian Barnett Shale. J. Sediment. Res. 2009, 79, 848–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M.E.; Sondergeld, C.H.; Ambrose, R.J.; Rai, C.S. Microstructural Investigation of Gas Shales in Two and Three Dimensions Using Nanometer-Scale Resolution Imaging. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, A.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, J. LA-ICP-MS U-Pb Dating and Geochemical Characterization of Oil Inclusion-Bearing Calcite Cements: Constraints on Primary Oil Migration in Lacustrine Mudstone Source Rocks. Bulletin 2022, 134, 2022–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, A.; Bons, P.D.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Song, J. Age, Material Source, and Formation Mechanism of Bedding-Parallel Calcite Beef Veins: Case from the Mature Eocene Lacustrine Shales in the Biyang Sag, Nanxiang Basin, China. Bulletin 2022, 134, 1811–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, C.; Liu, N.; Shaibu, R.; Ahmed, A.A.; Hashish, R.G. A Technical Review of CO2 for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Unconventional Oil Reservoirs. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 221, 111185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachu, S. CO2 Storage in Geological Media: Role, Means, Status and Barriers to Deployment. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Mehrad, M.; Rukavishnikov, V.S. Carbon Dioxide Sequestration through Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Review of Storage Mechanisms and Technological Applications. Fuel 2024, 366, 131313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanov, V.L. The Need for the Green Economy Factors in Assessing the Development and Growth of Russian Raw Materials Companies. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2024, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Yang, D. Semi-Analytical Modeling of Transient Pressure Behaviour for Fractured Horizontal Wells in a Tight Formation with Fractal-like Discrete Fracture Network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 197, 107937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ma, X.; Pan, D. Effects of a Multistage Fractured Horizontal Well on Stimulation Characteristics of a Clayey Silt Hydrate Reservoir. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 35705–35719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Su, H. Study on the Production Decline Characteristics of Shale Oil: Case Study of Jimusar Field. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 845651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, B.X.; Kohli, A.; Kovscek, A.R.; Alvarado, V. Effects of Supercritical CO2 Injection on the Shale Pore Structures and Mass Transport Rates. Energy Fuels 2022, 37, 1151–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Q. Simulation Study of CO2 Huff-n-Puff in Tight Oil Reservoirs Considering Molecular Diffusion and Adsorption. Energies 2019, 12, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Tsau, J.-S.; Barati, R. Role of Molecular Diffusion in Heterogeneous Shale Reservoirs During CO2 Huff-n-Puff. In Proceedings of the 79th EAGE Conference and Exhibition 2017—SPE EUROPEC, Paris, France, 12–15 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, R.; Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhou, T. CO2 Mass Transfer and Oil Replacement Capacity in Fractured Shale Oil Reservoirs: From Laboratory to Field. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 9, 794534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, D.; Yu, L.; Tian, Y. Exploring Pore-Scale Production Characteristics of Oil Shale after CO2 Huff ‘n’ Puff in Fractured Shale with Varied Permeability. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Yu, H.; Xie, F.; Hu, M.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y. Experimental Investigation on the CO2 Effective Distance and CO2-EOR Storage for Tight Oil Reservoir. Energy Fuels 2022, 37, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, Q.; Guo, J.; Zhou, L. Study on Imbibition during the CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery in Fractured Tight Sandstone Reservoirs. Capillarity 2023, 7, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, G.; Tang, M.; Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhu, M.; Xie, Z. Experimental Study on CO2 Flooding Characteristics in Low-Permeability Fractured Reservoirs. Energy Sources Part A 2023, 45, 11637–11649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, K.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Shi, H.; Wang, H. Numerical Model of CO2 Fracturing in Naturally Fractured Reservoirs. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 244, 107548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Li, Z.; Wei, M.; Lai, F.; Bai, B. Sensitivity Analysis of Water-Alternating-CO2 Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery in High Water Cut Oil Reservoirs. Comput. Fluids 2014, 99, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Yang, Z.; Yu, H.; Du, M.; Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; et al. Chemical-Assisted CO2 Water-Alternating-Gas Injection for Enhanced Sweep Efficiency in CO2-EOR. Molecules 2024, 29, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, L.; Song, Y.; Husein, M.M. Characteristics of CO2 Foam Plugging and Migration: Implications for Geological Carbon Storage and Utilization in Fractured Reservoirs. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 294, 121190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Nagel, T.; Chen, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhuang, D. Influence of Heterogeneity on Dissolved CO2 Migration in a Fractured Reservoir. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.-H.; Deng, H.-Y.; Hu, T.; Sheng, G.-L.; Wilson, M.; Dindoruk, B.; Patil, S. Coupling Mechanism Analysis of CO2 Non-Darcy Flow in Multi-Scale Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Life-Cycle Process of Fracturing-Development in Shale Oil Reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 1171–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Xin, Y.; He, L.; Jiao, Z.; Zou, J. Experimental and Modeling Assessment of CO2 EOR and Storage Performances in Tight Oil Reservoir, Yanchang Oilfield, China. J. CO2 Util. 2025, 97, 103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentaw, J.W.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A.; Fernandez, D.M.; Thiyagarajan, S.R. Geochemistry in Geological CO2 Sequestration: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2024, 17, 5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satea, A.; Tian, Y.; Kou, Z.; Kang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L. A Technical Review of Chemical Reactions During CCUS-EOR in Different Reservoirs. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2025, 12, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatah, A.; Mahmud, H.B.; Bennour, Z.; Gholami, R.; Hossain, M. Geochemical Modelling of CO2 Interactions with Shale: Kinetics of Mineral Dissolution and Precipitation on Geological Time Scales. Chem. Geol. 2022, 592, 120742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Tang, J.; Liu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Y. Pore Alteration of Yanchang Shale after CO2-Brine-Rock Interaction: Influence on the Integrity of Caprock in CO2 Geological Sequestration. Fuel 2024, 363, 130952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEM. GEM-GEM User’s Guide; Computer Modeling Group Ltd.: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmund, P.M. Prediction of Molecular Diffusion at Reservoir Conditions. Part II-Estimating the Effects of Molecular Diffusion and Convective Mixing in Multicomponent Systems. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 1976, 15, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C.R.; Chang, P. Correlation of Diffusion Coefficients in Dilute Solutions. AIChE J. 1955, 1, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolery, T.J.; Daveler, S.A. EQ6, a Computer Program for Reaction Path Modeling of Aqueous Geochemical Systems: Theoretical Manual, Users Guide, and Related Documentation (Version 7.0); Part 4; Lawrence Livermore National Lab. (LLNL): Livermore, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H. Impact of Four Different CO2 Injection Schemes on Extent of Reservoir Pressure and Saturation. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2018, 2, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiabadi, S.H.; Bedrikovetsky, P.; Borazjani, S.; Mahani, H. Well Injectivity During CO2 Geosequestration: A Review of Hydro-Physical, Chemical, and Geomechanical Effects. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 9240–9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Zhou, T.; Lyu, W.; He, D.; Sun, Y.; Du, M.; Wang, M.; Li, Z. Front Movement and Sweeping Rules of CO2 Flooding under Different Oil Displacement Patterns. Energies 2024, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, M.G.; Foroozesh, J. Phase Behavior and Fluid Interactions of a CO2-Light Oil System at High Pressures and Temperatures. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironova, D.Y.; Pashkova, E.A.; Budrin, A.G.; Baranov, I.V.; Varadarajan, V.; Afrifa, S. Enhancing University Innovation through Industrial Symbiosis. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Model dimensions | 110 × 350 × 20 | m |

| Initial reservoir pressure | 18 | MPa |

| Reservoir temperature | 69 | °C |

| Initial water saturation | 45.90 | % |

| Matrix porosity | 8 | % |

| Matrix permeability | 0.02 | mD |

| Total compressibility | 6.3 × 10−4 | 1/MPa |

| Fracture height | 20 | m |

| Fracture width | 0.003 | m |

| Fracture half-length | 100 | m |

| Fracture conductivity | 60 | mD·m |

| Model dimensions | 110 × 350 × 20 | m |

| Initial reservoir pressure | 18 | MPa |

| Component | mol. (%) | Pc (atm) | Tc (K) | Acentric Factor | Mw (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 0.09 | 72.80 | 304.20 | 0.2250 | 44.010 |

| C1 | 25.72 | 45.40 | 190.60 | 0.0080 | 16.043 |

| N2-C2 | 10.54 | 47.36 | 264.76 | 0.0905 | 29.803 |

| C3 | 12.14 | 41.90 | 369.80 | 0.1520 | 44.097 |

| C4-C6 | 12.08 | 40.00 | 447.97 | 0.2164 | 67.278 |

| C7-C10 | 7.24 | 24.38 | 630.61 | 0.3812 | 116.961 |

| C11-C14 | 8.96 | 18.86 | 634.90 | 0.5464 | 169.979 |

| C15-C19 | 7.23 | 12.00 | 700.00 | 0.6358 | 233.372 |

| C20+ | 16.00 | 14.99 | 737.31 | 0.7680 | 378.757 |

| Component | CO2 | C1 | N2-C2 | C3 | C4-C6 | C7-C10 | C11-C14 | C15-C19 | C20+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 0 | ||||||||

| C1 | 1.13 × 10−1 | 0 | |||||||

| N2-C2 | 1.05 × 10−1 | 1.06 × 10−3 | 0 | ||||||

| C3 | 1.25 × 10−1 | 1.24 × 10−3 | 4.58 × 10−3 | 0 | |||||

| C4-C6 | 1.16 × 10−1 | 4.64 × 10−3 | 1.01 × 10−2 | 1.09 × 10−3 | 0 | ||||

| C7-C10 | 2.00 × 10−1 | 1.23 × 10−2 | 2.04 × 10−2 | 5.83 × 10−3 | 1.89 × 10−3 | 0 | |||

| C11-C14 | 1.95 × 10−1 | 2.08 × 10−2 | 3.09 × 10−2 | 1.21 × 10−2 | 5.98 × 10−3 | 1.15 × 10−3 | 0 | ||

| C15-C19 | 1.40 × 10−1 | 2.90 × 10−2 | 4.05 × 10−2 | 1.86 × 10−2 | 1.08 × 10−2 | 3.71 × 10−3 | 7.29 × 10−4 | 0 | |

| C20+ | 9.86 × 10−2 | 4.39 × 10−2 | 5.75 × 10−2 | 3.11 × 10−2 | 2.09 × 10−2 | 1.04 × 10−2 | 4.69 × 10−3 | 1.73 × 10−3 | 0 |

| Reactions | |

|---|---|

| Intra-aqueous reactions | |

| Mineral reactions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qiao, R.; Yang, B.; Huang, H.; Ren, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Feng, H. Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of CO2 Migration and Pressure Propagation Considering Molecular Diffusion and Geochemical Reactions in Shale Oil Reservoirs. Energies 2026, 19, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010164

Qiao R, Yang B, Huang H, Ren Q, Cheng Z, Feng H. Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of CO2 Migration and Pressure Propagation Considering Molecular Diffusion and Geochemical Reactions in Shale Oil Reservoirs. Energies. 2026; 19(1):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010164

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiao, Ruihong, Bing Yang, Hai Huang, Qianqian Ren, Zijie Cheng, and Huanyu Feng. 2026. "Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of CO2 Migration and Pressure Propagation Considering Molecular Diffusion and Geochemical Reactions in Shale Oil Reservoirs" Energies 19, no. 1: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010164

APA StyleQiao, R., Yang, B., Huang, H., Ren, Q., Cheng, Z., & Feng, H. (2026). Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of CO2 Migration and Pressure Propagation Considering Molecular Diffusion and Geochemical Reactions in Shale Oil Reservoirs. Energies, 19(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010164