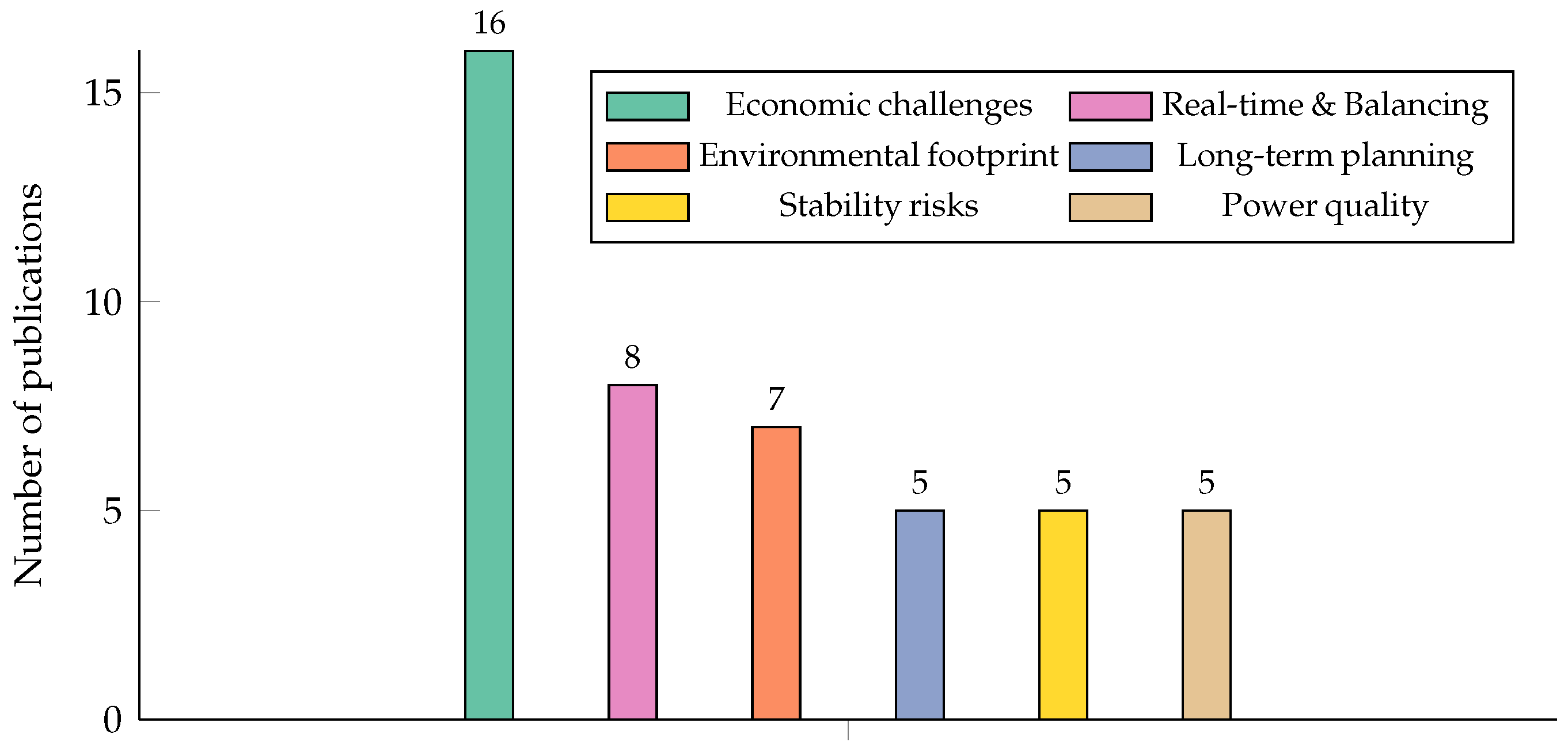

3.2. Real-Time Operations and Balancing Challenges

The volatile and massive power consumption profile presented by AI data centers introduces distinct challenges for the real-time management of the power grid. The highly variable and rapid changes in their power demand complicate short-term forecasting, and place significant strain on the system’s ability to balance the generation and load.

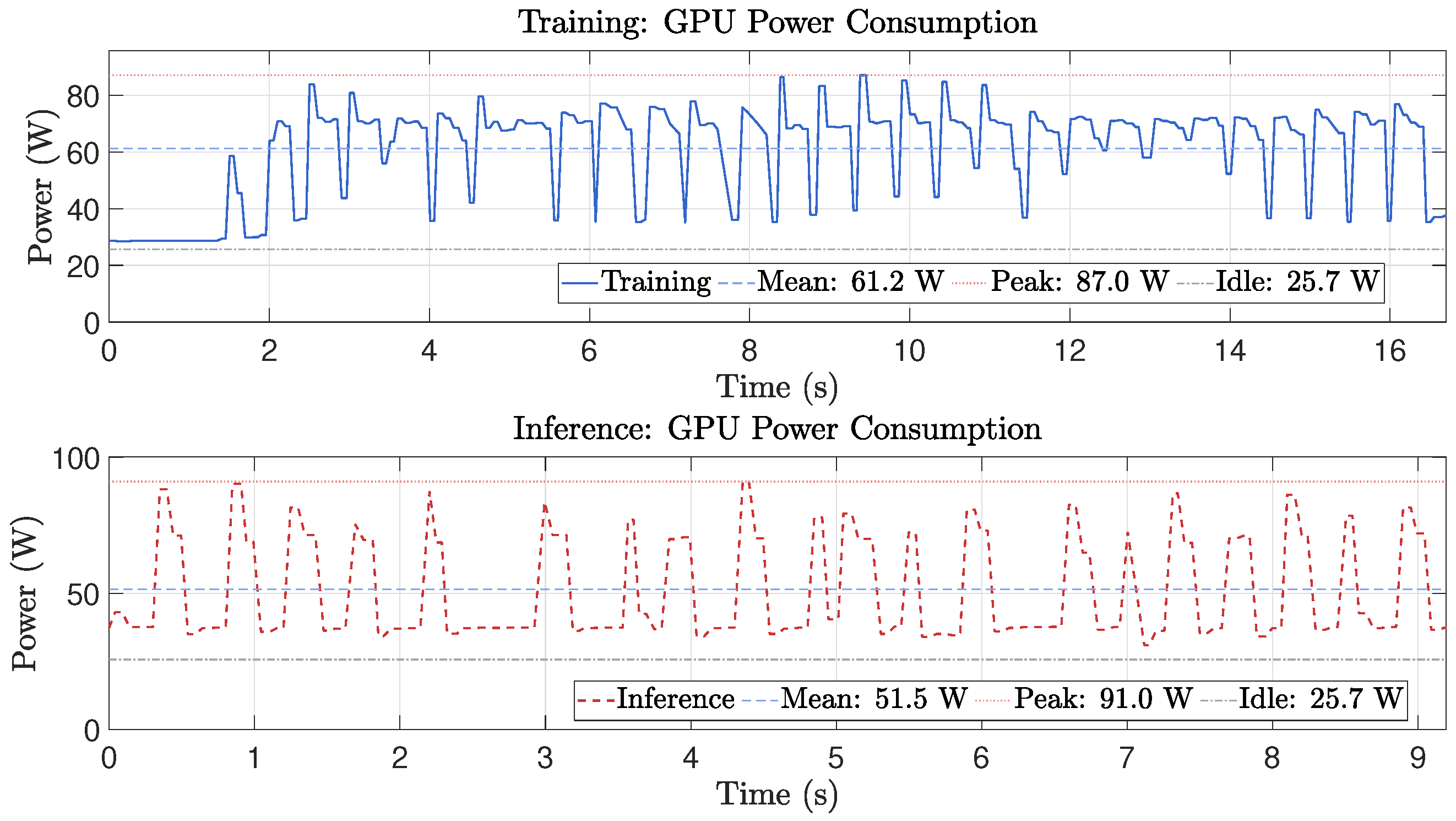

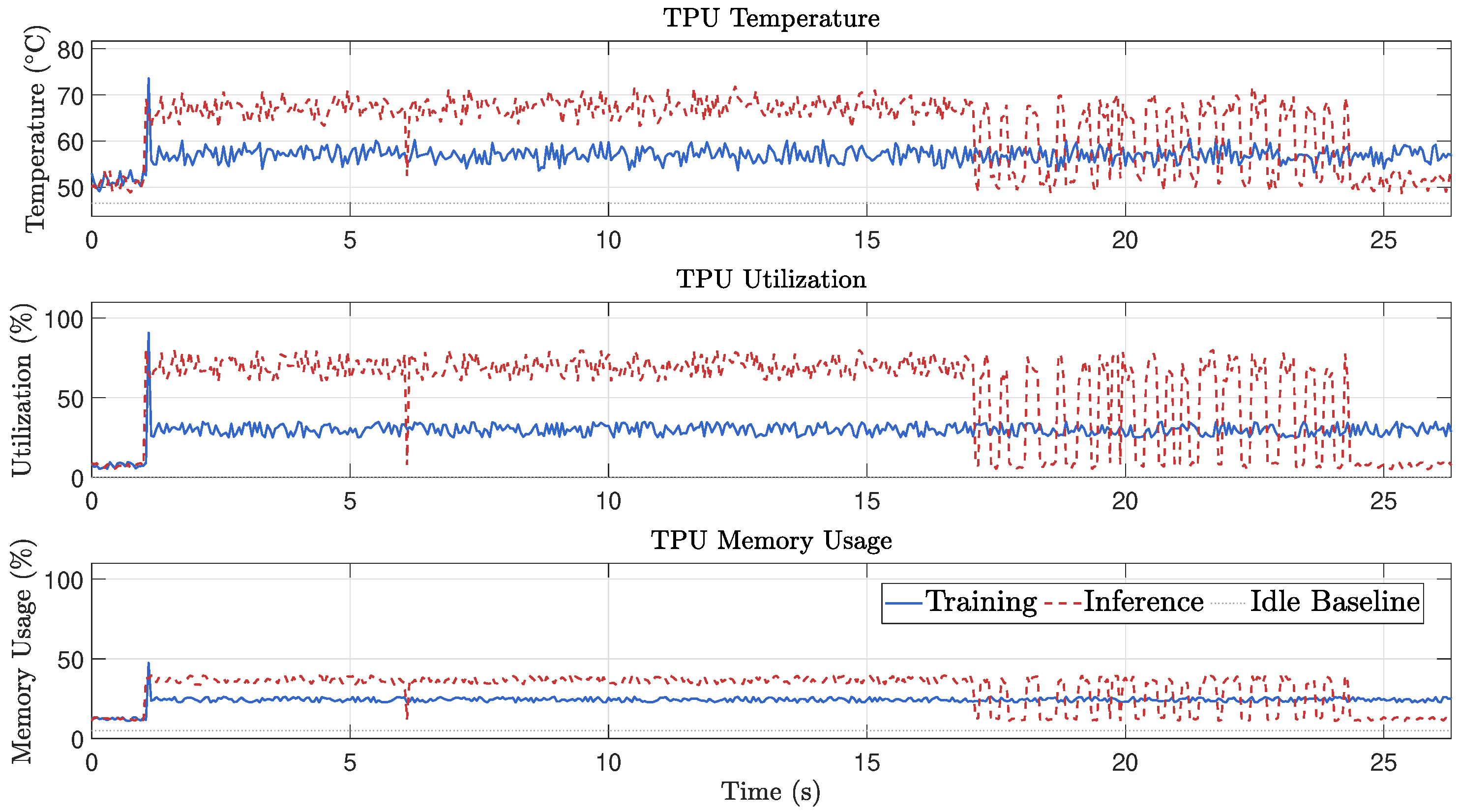

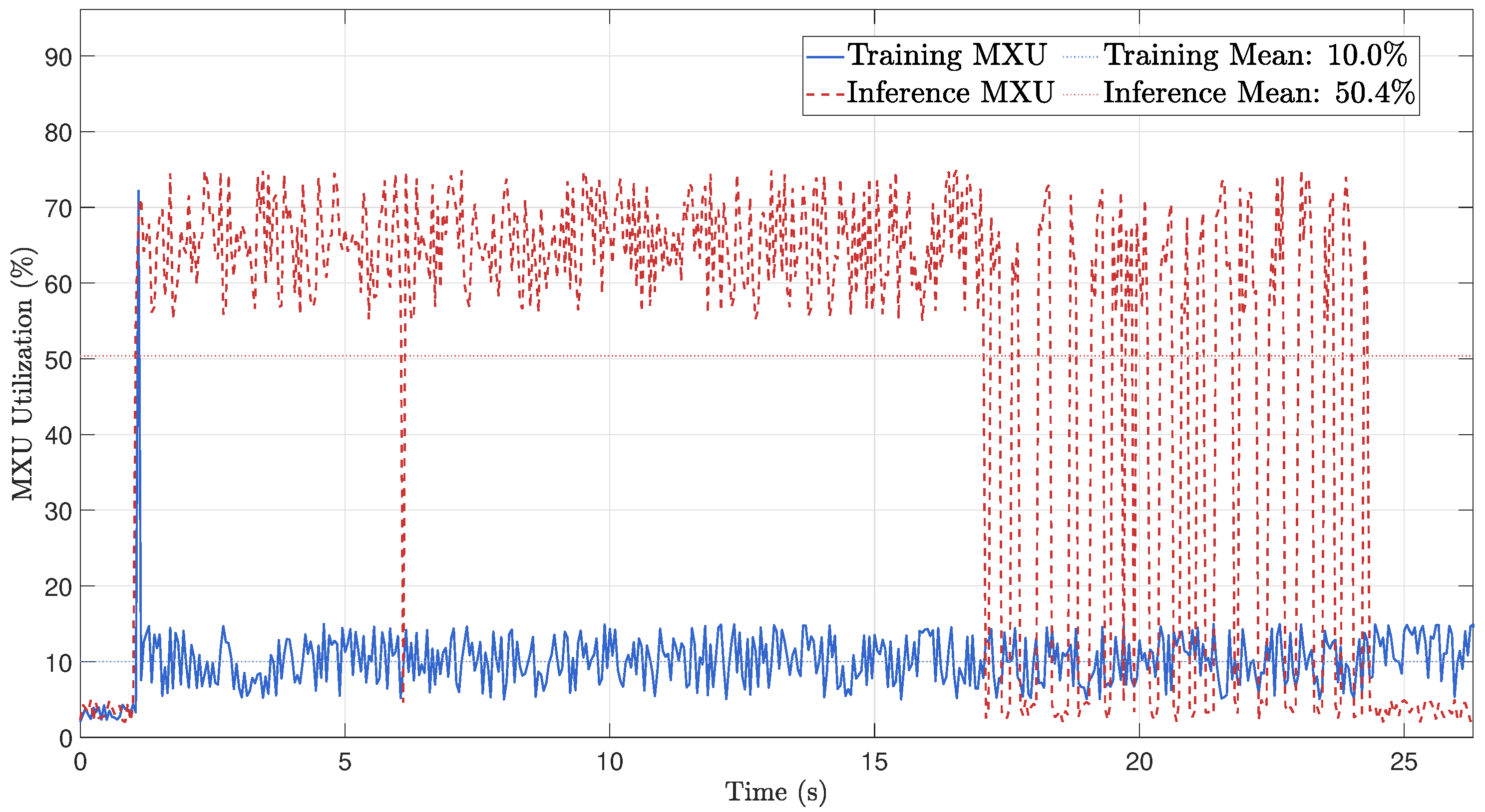

Short-term demand forecasting is made more difficult by the stochastic nature of AI training workloads. Unlike traditional loads, the power consumption of a large-scale training cluster does not follow predictable daily or weekly patterns. Instead, it is dictated by the initiation, execution, and completion of training jobs, which can cause large, abrupt changes in power demand [

5]. The power profile within a single training iteration consists of compute-heavy phases, where power draw is near maximum, and communication-heavy phases, where power consumption drops significantly [

4]. These rapid fluctuations, which can occur on a sub-second timescale, are challenging for grid operators to predict accurately using conventional forecasting models that rely on historical trends and slower-moving variables.

This volatility directly impacts the grid’s balancing and reserve management. A core principle of reliable grid operation is maintaining a continuous balance between electricity generation and demand, since imbalance in active or reactive power significantly impacts the voltage magnitude at a bus. This relationship can be expressed using Voltage Sensitivity Factors (VSF) [

38]:

, where

is the change in voltage magnitude at bus

i, and

,

are column vectors representing the changes in active and reactive power at the arbitrary buses where these changes occur. The matrices

and

are the voltage sensitivity factors, specifically denoting the voltage sensitivity to active power and reactive power respectively. Data centers, with their rapid active power ramps, and dynamic reactive power demands, cause high

and

values. These rapid changes can lead to significant voltage deviations that conventional grid devices are too slow to compensate [

39,

40].

The consumed power of the data center directly affects the voltage at the connection point (PCC). For a simplified radial connection from a source, such as an infinite bus, through a line impedance

to the data center load, the approximate voltage drop,

, across the line is given by

, where

and

are the active and reactive power consumed by the data center, and

is the voltage magnitude at the PCC. The voltage at the PCC can then be approximated,

, where

is the voltage magnitude of the source. This analysis, although relying on approximated quasi-static models, explains how changes in the active and reactive power consumed by the data center inversely influence the voltage magnitude at the PCC. This is a fundamental challenge, as hyperscale data centers demand exceptionally high active power, leading to significant voltage drops, especially in weak grids or at the end of long distribution lines [

41].

To manage such unexpected deviations, system operators maintain various types of operating reserves. However, the ramp rates of AI data centers, which can change by hundreds of megawatts in seconds, are often much faster than the response capabilities of conventional generators, which are typically measured in megawatts per minute [

25,

42]. As shown in the NERC report, a data center’s load can ramp down by over 400 MW in just 36 s [

25]. Such rapid load changes can quickly exhaust the grid’s primary frequency control and balancing reserves. To manage these fast ramps, system operators may need to procure larger amounts of more expensive and faster-acting ancillary services, such as Fast-Frequency Response, which increases operational costs [

25]. Without sufficient fast-acting reserves, these sudden load changes can lead to significant frequency deviations, posing a risk to grid stability.

3.3. Power System Stability Risks

The dynamic and unpredictable behavior of AI data center loads poses direct risks to power system stability. The most significant of these risks stems from the protective mechanisms within data centers themselves, which can trigger cascading events across the wider grid.

A primary stability concern is the voltage and frequency ride-through behavior of data centers. To protect sensitive IT equipment and ensure service uptime, data centers are designed with internal protection systems that disconnect them from the grid during voltage or frequency disturbances [

25]. While this action preserves the individual facility, the simultaneous disconnection of multiple large data centers can create a severe system-wide disturbance. This phenomenon, where individual reliability measures create a collective vulnerability, can be described as a self-preservation paradox. A notable example of this occurred in July 2024, when a transmission line fault in the Eastern Interconnection caused a voltage disturbance that triggered the simultaneous loss of approximately 1500 MW of load, primarily from data centers transferring to backup power systems [

25,

43].

Such large-scale, near-instantaneous load shedding events have direct consequences for frequency stability. When a large amount of load is suddenly removed from the system, the generation immediately exceeds the remaining demand. This power surplus causes the rotational speed of synchronous generators across the interconnection to increase, leading to a system-wide over-frequency event [

25]. In the July 2024 incident, the loss of 1500 MW of load caused the grid frequency to rise to 60.053 Hz before control actions could restore the balance [

25]. Conversely, the sudden start of a large AI training job can create an under-frequency event if the additional load is not anticipated and matched by an equivalent increase in generation.

To demonstrate this concept, we perform a simulation to investigate the system’s dynamic response to a realistic AI workload. The system model formulation includes a power architecture that includes the data center load, a dedicated local power source, and a connection to the external utility grid. The data center’s total power consumption is denoted by

. It is met by the sum of power from its local synchronous generator,

, and power drawn from the grid,

. The utility grid is treated as an infinite bus. The behavior of the synchronous generator is governed by the swing equation, which incorporates a standard droop control mechanism to manage the generator’s frequency deviation

and rotor angle

. By applying the principle of power conservation at the point of common coupling, the generator’s swing equation is combined with the AC power flow equation describing the grid connection. This process yields a coupled set of first-order differential equations that define the system’s dynamics in terms of the state variables

and

as follows

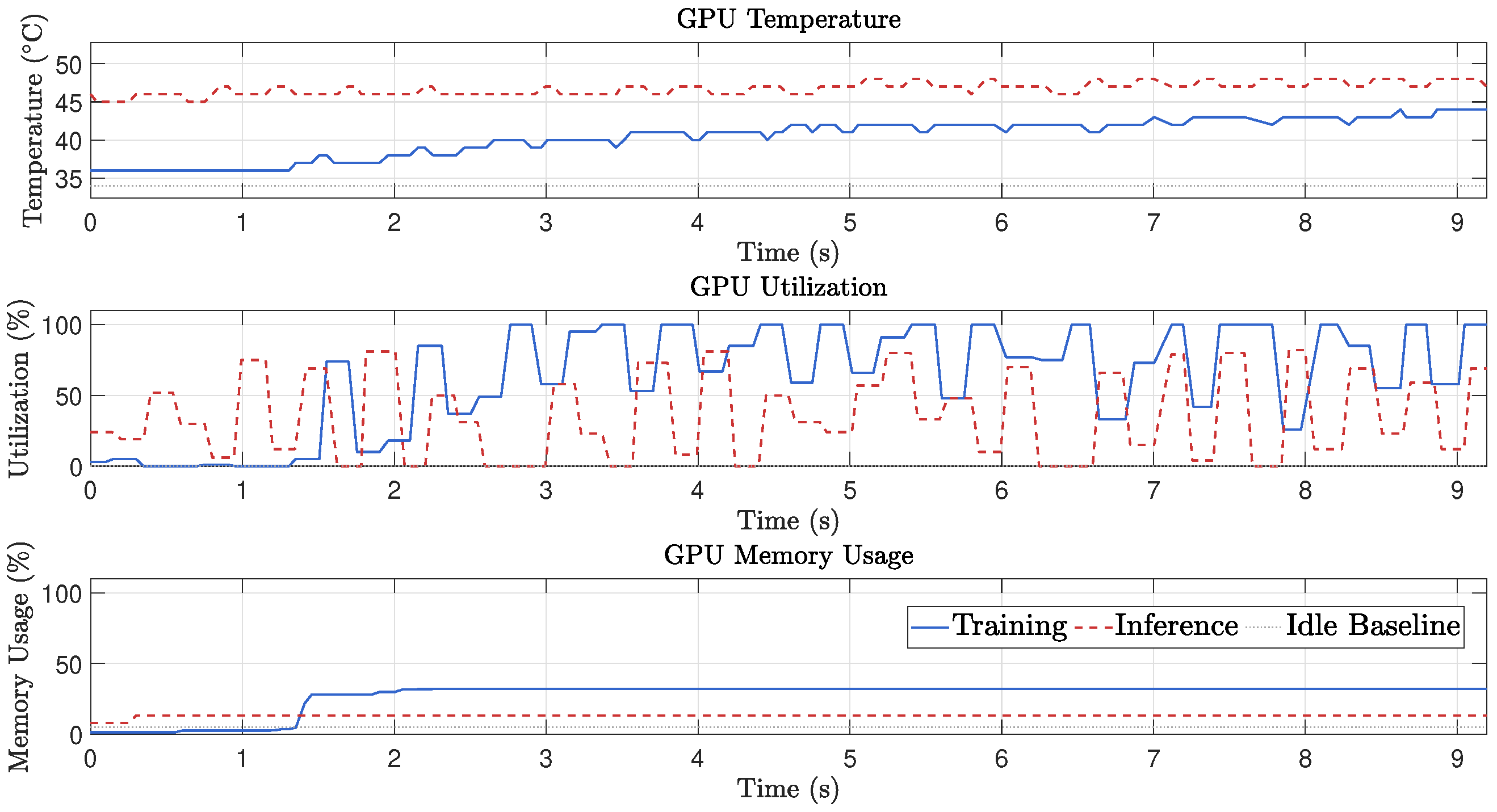

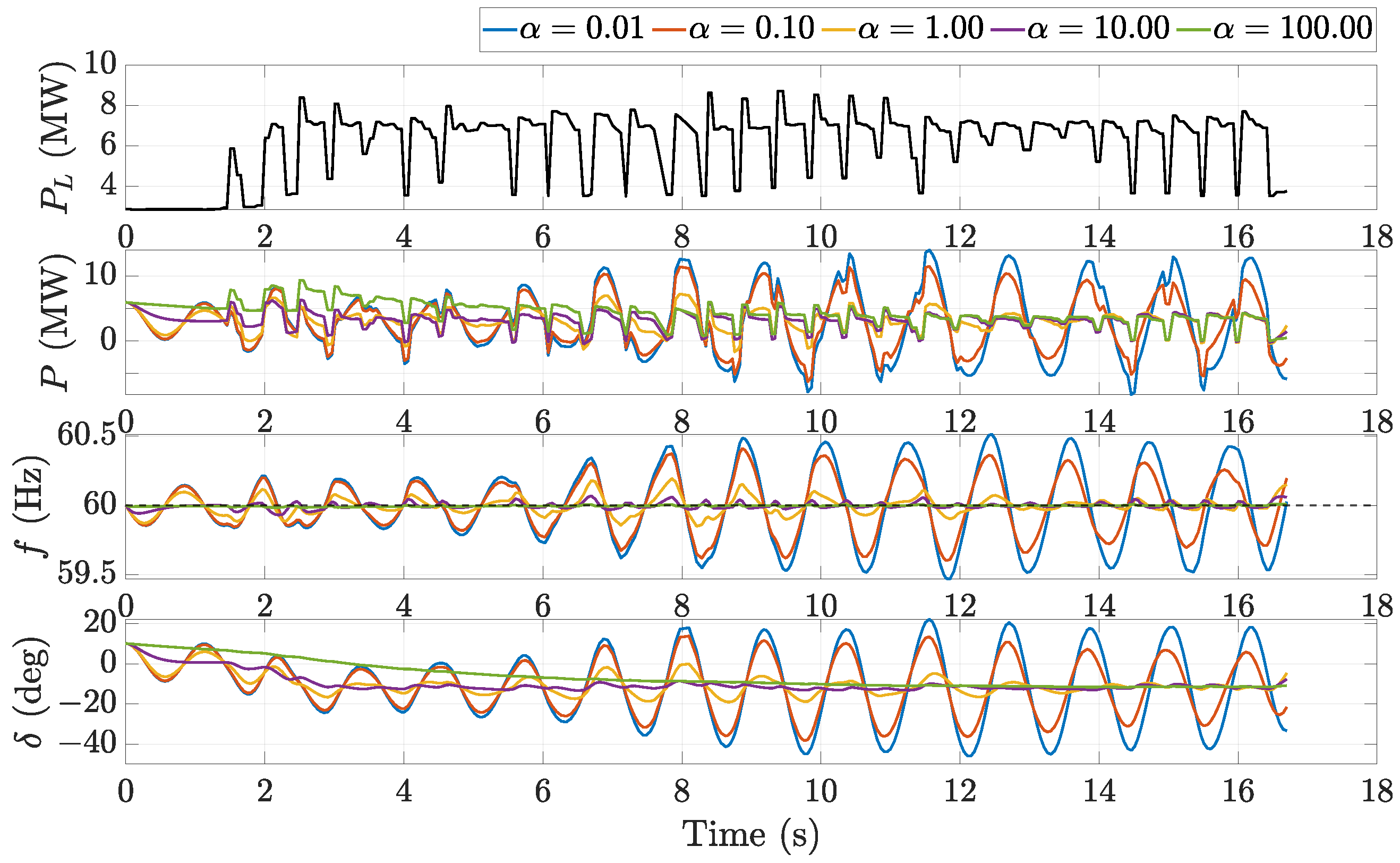

To demonstrate the system’s dynamic behavior under rapid load changes, simulations are performed using MATLAB R2024b and Simulink. The analysis models the characteristic AI load based on data collected during a ResNet50 training process on a Tesla T4 GPU, which is then scaled to represent a GPU cluster, simulating a large-scale data center operation. This load is managed by a system with baseline parameters representing a plausible data center scenario, including a 17.41 MW rated generator and a 17.41 MW grid connection. This configuration provides a power transfer capability twice that of the load step. The nominal system frequency is 60 Hz, and the generator’s reference power is initially set to 3.058 MW, which is half of the applied load increase.

A comprehensive parametric study is then conducted to investigate the system’s sensitivity to key design choices. The damping characteristic

is varied across five values from 0.01 to 100 s

−1. The simulations are run for 17.7 s, employing numerical tolerance and step size settings designed to ensure accuracy. The parameters are summarized in

Table 3.

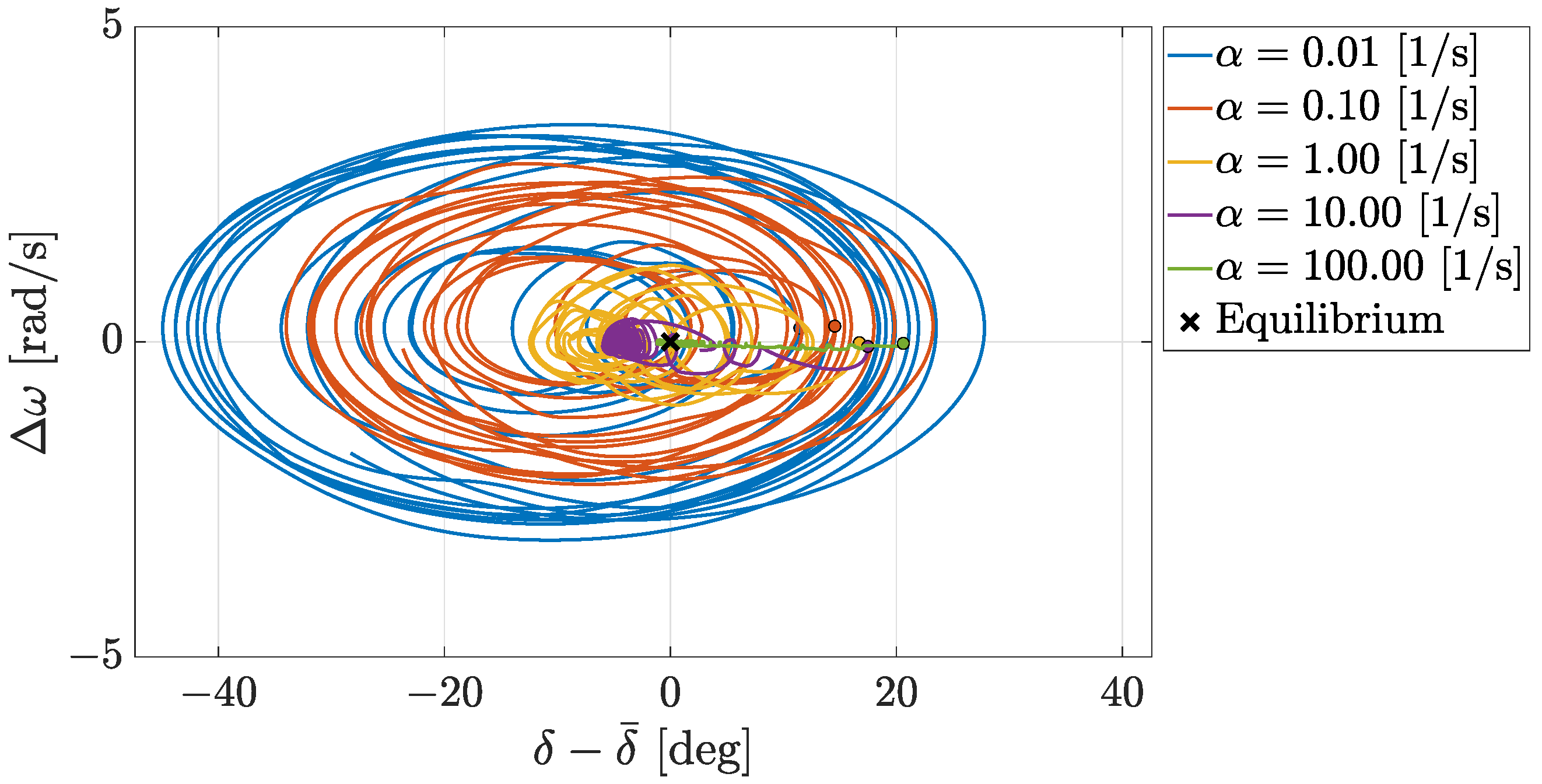

The simulation results, presented in

Figure 11, demonstrate a fundamental trade-off between system stability and component stress when a generator responds to a sudden load increase. A high damping factor (

) effectively suppresses frequency and angle oscillations, allowing the system to stabilize quickly. However, this rapid stabilization demands larger power peaks from the generator, placing significant transient stress on its hardware. Conversely, a lower damping factor reduces these power overshoots and component stress but allows the system to oscillate for a longer, potentially destabilizing, period.

This balance is critical for AI data centers, which produce continuous, high-frequency load fluctuations. In this environment, a high damping setting that seems beneficial for a single event could be detrimental. It might cause the generator to constantly react to the volatile load, leading to excessive mechanical wear and a reduced operational lifespan. Therefore, the damping characteristic must be selected with care to balance the need for a fast transient response with the long-term reliability required to handle the unique, persistently fluctuating load profile of AI training.

To quantify the system performance under these varying damping conditions,

Table 4 presents the Root Mean Square Error and Mean Absolute Error for both frequency and rotor angle deviations. A clear inverse relationship exists between the damping coefficient

and the frequency error metrics. Specifically, as

increases from 0.01 to 100.00, the Frequency RMSE decreases from 0.2090 Hz to 0.0073 Hz. Similarly, the Mean Absolute Error for frequency drops from 0.1727 Hz at the lowest damping setting to 0.0064 Hz at the highest setting. These values indicate that higher damping coefficients effectively constrain frequency excursions to a narrow band around the nominal 60 Hz value.

The rotor angle stability exhibits a corresponding trend where increased damping significantly reduces angular deviations from the equilibrium point. The RMSE for the relative angle diminishes from 17.9674 degrees at equals 0.01 to 6.9838 degrees at equals 100.00. We observe a similar reduction in the MAE metric, which falls from 14.1121 degrees to 6.3865 degrees across the same range. The intermediate damping value of equals 1.00 yields an angle RMSE of 11.3524 degrees and represents a transitional state where the system maintains stability without imposing the extreme rigidity associated with the highest damping values. This quantitative reduction in error metrics at higher damping levels confirms that the system creates a stiffer response to the load fluctuations.

To further visualize these stability margins, we analyze the phase plane portraits shown in

Figure 12. This plot illustrates the trajectory of the system state, defined by the frequency deviation

and the relative rotor angle

, as it converges toward the equilibrium point. The trajectories for low damping values, specifically

and

, exhibit wide, spiraling orbits that span a large area of the state space. These extensive excursions indicate a highly oscillatory response where the generator rotor undergoes significant angular swings and frequency deviations before settling. Such behavior suggests a system with low stability margins, where a subsequent load spike from an AI training batch could easily push the rotor angle beyond its critical limit, resulting in a loss of synchronism.

In contrast, the trajectories for higher damping values, such as and , demonstrate a tightly constrained response where the system state moves rapidly and directly toward the equilibrium. While this confinement effectively minimizes the risk of angular instability, it physically represents a scenario where the generator governor aggressively counteracts every deviation. In the context of AI workloads, which are characterized by stochastic and rapid power pulses, this aggressive control logic forces the mechanical components to endure high-frequency stress cycles. Consequently, the phase plane analysis reinforces the conclusion that optimal parameter selection lies in the intermediate range, such as , which creates a balance by restricting hazardous angular excursions without imposing the excessive rigidity that accelerates equipment degradation.

Voltage stability is also compromised by mass load-tripping events. The sudden disconnection of large loads, which consume both active and reactive power, can lead to a surplus of reactive power on the local transmission system. This excess reactive power can cause a rapid and significant voltage rise, or overvoltage, that can damage other connected equipment and potentially initiate further protective tripping, increasing the risk of cascading outages [

25].

Furthermore, the high concentration of power electronic converters within AI data centers introduces risks of converter-driven instability and resonance. These electronic devices lack the physical inertia of traditional electromechanical equipment and are governed by fast-acting control systems. These controls can interact negatively with the electrical characteristics of the grid, potentially reducing the damping of natural system oscillations or creating new, unstable oscillations [

25]. For example, an event in 2023 demonstrated that power electronics at a large data center inadvertently perturbed the local system at a 1 Hz frequency. This action repeatedly excited a natural 11 Hz resonant frequency in the grid, producing a persistent forced oscillation that posed a risk to system reliability [

25].

To better understand the source of this behavior, we can examine the system in the phasor domain. Naturally, data centers, as non-linear loads, are significant sources of harmonic distortion. The non-sinusoidal current drawn by the data center contains harmonic components. These harmonics are generated by the switching actions of power electronic converters within UPS systems, IT power supplies, and variable frequency drives for cooling. The level of current distortion is quantified by the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) of the current, with high indicating significant current distortion. When these harmonic currents flow through the impedance of the grid, , they generate harmonic voltages, , across the system. For a specific harmonic frequency , the harmonic voltage is , where is the grid’s impedance at the n-th harmonic frequency, meaning that even if the source voltage is perfectly sinusoidal, the voltage at the point of common coupling with the data center will become distorted due to the harmonic currents.

A critical issue arises when loads with capacitive profile,

, are connected to one of the buses. Indeed, modern data center IT loads, governed by power electronics, typically present a capacitive load profile. This stems from the fact that the IT equipment itself, namely, the servers, storage, and networking devices, uses switch-mode power supplies that are required to have Power Factor Correction (PFC) circuits. These PFC circuits almost universally use filter capacitors at their input stage, resulting in the capacitive nature of the data center. While the overall data center’s power factor is a complex mix of these capacitive IT loads and the inductive cooling loads [

44], the power electronics at the server level are the primary source of the capacitive nature, not an inductive one. This leading power factor from IT loads is a known challenge, as it can interact poorly with the inductive components of the grid and the data center’s own backup UPS systems [

45,

46].

In this scenario, these capacitors may create a parallel resonance with the grid’s inductive components, , at a harmonic frequency . The impedance of such a parallel combination is given by . If , the impedance approaches infinity, leading to an amplification of harmonic voltages, meaning , even for small harmonic currents. Although these oscillations may remain within safety margins, they can cause overheating and equipment damage.

3.4. Power Quality

Power quality is a measure of the degree to which voltage and current waveforms comply with established specifications [

47]. Recent research works, including [

25,

48], highlight that large data centers, often reaching hundreds of megawatts and relying on power electronics equipment, introduce new power quality concerns. A key challenge is the rapid fluctuation in power demand, which can produce sudden load ramps within milliseconds and make it difficult to maintain power quality within specified limits. Furthermore, in regions where several centers operate from the same grid node, simultaneous fluctuations can create substantial power quality disturbances.

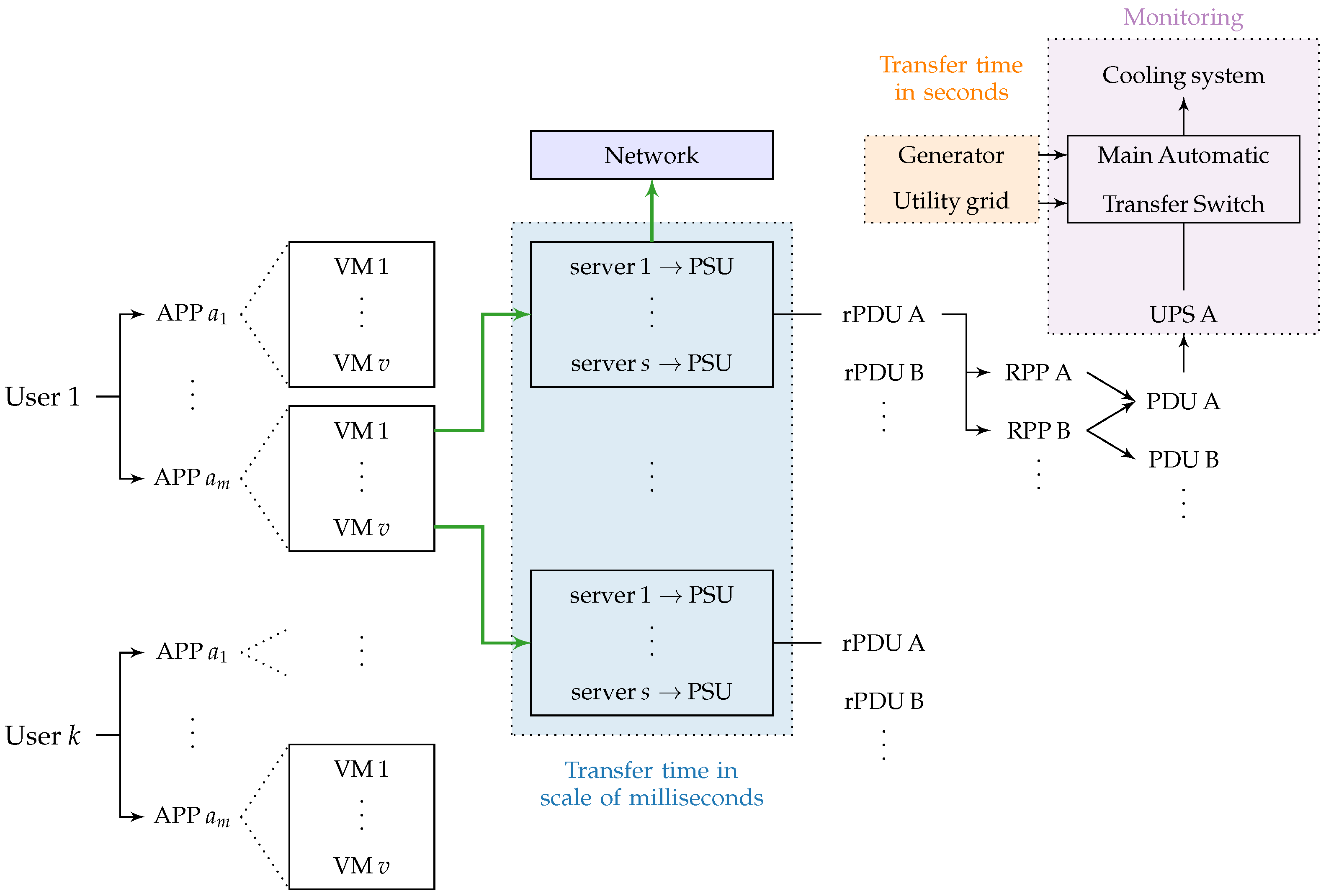

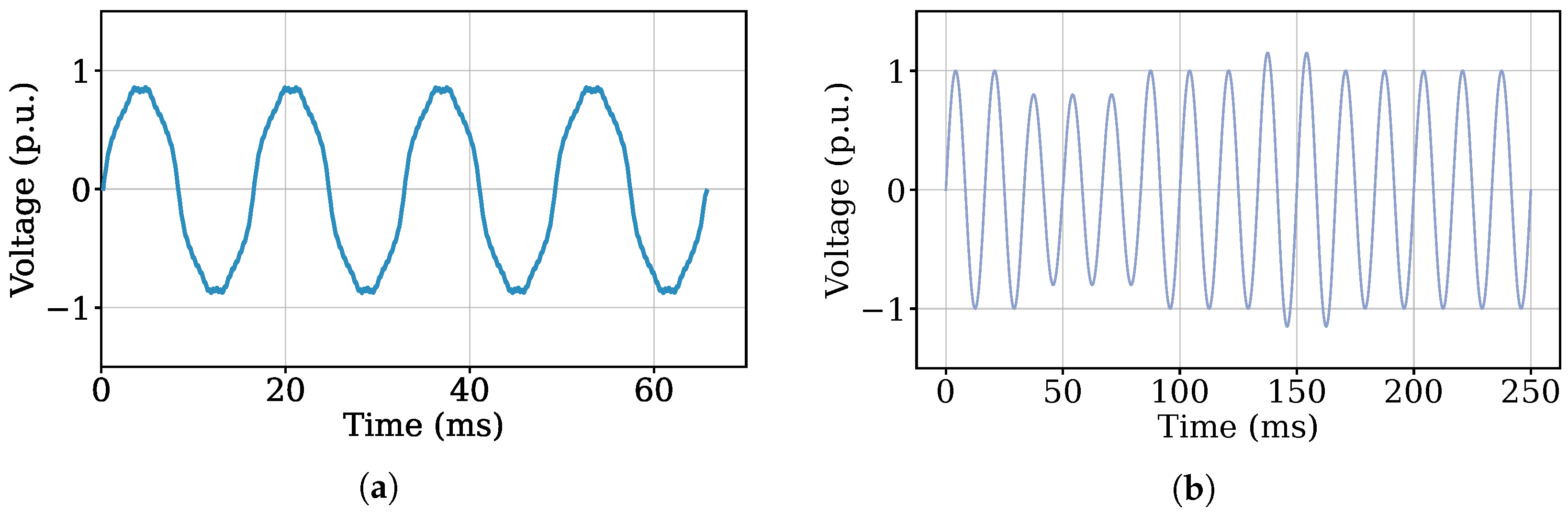

More specifically, the power electronics systems common in data centers, such as UPS units (Illustrated in

Figure 2), and variable-speed drives for cooling, operate with high-frequency switching. This process generates non-linear currents that distort the grid’s voltage waveform. These harmonic distortions, illustrated in

Figure 13a, are a primary disturbance. For instance, a recent report [

25] documents a data center facility that produced excessive voltage harmonic distortion, which was significant enough to require the installation of a dedicated harmonic mitigation solution. Without such filtering, these non-linear currents can interact with grid components. This interaction poses a risk of parallel resonance, which can amplify harmonic voltages and lead to problems such as transformer overheating, increased equipment losses, and general component stress.

Voltage sags, swells, and short interruptions also pose significant risks (

Figure 13b). Data centers are highly sensitive to brief voltage dips that can interrupt servers or cooling systems. When facilities transfer to backup generators, the sudden disconnection of large loads can produce sharp changes in voltage and frequency, similar in impact to a major generation trip.

These power quality issues are further compounded by the limited visibility that grid operators have into data center loads. This lack of data hinders the ability of system operators to accurately forecast load behavior under both normal and disturbance conditions. Many data center operators manage their on-site systems privately, meaning their internal switching protocols and load ramping actions are not fully transparent to utilities.

To conclude, power quality problems in data centers arise from rapid load variations, non-linear current profiles, voltage sensitivity, and unstable reactive power behavior, all of which may degrade overall power quality. Addressing these issues requires coordinated planning between utilities and operators, improved harmonic filtering, and clear interconnection standards.

3.5. Economic Challenges

The costs of training frontier AI models have grown dramatically in recent years, reaching billions of dollars [

3]. This section analyzes the financial dimensions of the rapid increase in energy demand driven by AI, including the costs of necessary grid modernization, the contentious debate over who bears these costs, the disruption of wholesale electricity markets, and the complex, often contradictory, socio-economic impacts on local communities.

The scale of investment required to build the physical infrastructure for the AI revolution is immense. A recent analysis [

49] projects a global need for

$6.7 trillion in data center capital expenditures by 2030, with

$5.2 trillion of that dedicated specifically to AI-ready facilities. This figure encompasses land acquisition, construction, and the procurement of servers and networking hardware [

26]. The upfront capital required to equip a single frontier training cluster is a significant barrier to entry; the hardware acquisition cost for the system used to train GPT-4, for instance, is estimated at

$800 million [

49].

This data center buildout necessitates a parallel and equally massive investment in the power grid. The projected load growth far exceeds the capacity of existing infrastructure in many regions. The research presented in [

50] estimates that approximately

$720 billion in U.S. grid spending will be required through 2030 to support this new demand, covering new power plants, high-voltage transmission lines, and local substation upgrades.

A central economic and political conflict has emerged over a simple question: who pays for these grid upgrades? Historically, the costs of new transmission infrastructure were socialized, or spread across all customers within a utility’s service area. However, this model is being challenged by the unique nature of data center load, where a single customer can necessitate billions of dollars in dedicated upgrades.

A recent report [

51] has identified a structural issue within the existing regulatory framework of the PJM Interconnection, the largest grid operator in the U.S. Their analysis found that in 2024 alone, an estimated

$4.4 billion in transmission upgrade costs, directly attributable to new data center connections, were passed on to all residential and commercial customers in seven states. In another research analysis, forecasts of a national average increase of 8% by 2030 were presented, due to increasing data center power demand [

52].

This situation has triggered a real-time regulatory scramble across the nation, as states independently attempt to reform the application of cost causation principles within century-old utility frameworks. For instance, in Ohio, the Public Utilities Commission (PUCO) ordered AEP Ohio to create a distinct tariff classification for data centers. This move, supported by the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel, is designed to ensure data centers bear the full cost of service and to protect other customers from the risks of stranded assets, which are underused investments made specifically for the data center industry [

53]. In Oregon, the legislature passed HB 3546, which mandates that data centers enter into long-term contracts (10 years or more) and that the full cost to serve their load is allocated directly to them, explicitly preventing the socialization of these costs [

54]. While in Michigan, a tariff case involving Consumers Energy is exploring similar protective measures, including 15-year minimum contracts and exit fees, to mitigate the financial risk to the public if a data center project is canceled or decommissioned prematurely [

55,

56]. These state-level actions represent a fundamental re-evaluation of utility ratemaking principles, setting critical precedents for how the substantial cost of the AI energy transition will be distributed between corporations and the public.

3.6. The Environmental Footprint: A Life-Cycle Perspective on AI’s Resource Intensity

A comprehensive evaluation of the environmental impact of AI data centers requires a perspective that extends beyond operational electricity use to include the embodied carbon of hardware and the consumption of water for cooling [

7,

57]. While efficiency gains are being made, the sheer scale of the industry’s growth, with global data center power demand forecast to more than double by 2030, presents a formidable environmental challenge [

2].

To accurately assess energy use, a “full-stack” measurement approach is essential. This methodology accounts for not only the energy consumed by active AI accelerators but also the power drawn by host systems (CPUs, DRAM), the energy used by idle machines provisioned for reliability, and the overhead of the data center’s power and cooling infrastructure, captured by the Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) metric. As demonstrated in a detailed analysis by Google, narrower approaches that focus solely on the accelerator chip can significantly underestimate the true energy footprint, with their comprehensive measurement being 2.4 times greater than a narrower, existing approach [

7].

Applying this comprehensive method, a study by Google found that a median text prompt for its Gemini model consumes 0.24 Wh [

7]. This figure is notably lower than many public estimates, which have ranged from 0.3 Wh for a ChatGPT-4o query to as high as 3.0 Wh for older models, demonstrating the significant impact of hardware-software co-design and continuous optimization [

7]. The energy consumed during model training is orders of magnitude greater due to the immense computational requirements of training jobs that can span tens of thousands of GPUs [

3,

57]. For instance, the amortized hardware and energy cost for training a frontier model like GPT-4 is estimated at

$40 million. While energy represents a relatively small fraction of this total training cost (2–6%), the absolute expenditure for a single frontier model still amounts to millions of dollars [

3].

The carbon footprint of an AI data center is composed of two primary components: operational emissions from electricity consumption and embodied emissions from the manufacturing and deployment of its physical infrastructure.

Operational emissions are the greenhouse gases released from the power plants that generate the electricity consumed by the data center. This footprint is highly dependent on the carbon intensity of the local grid. Major technology companies are among the largest corporate purchasers of renewable energy, often using Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and market-based accounting mechanisms to reduce their reported carbon footprint [

58]. However, the 24/7 operational requirement of data centers means that they inevitably draw power from fossil fuel-based generation when renewable sources like wind and solar are not available [

59].

Embodied emissions represent the carbon associated with the entire supply chain of a data center’s physical assets, including emissions from raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and end-of-life disposal of hardware [

57]. This category is distinct from operational carbon, which arises from energy consumption during use. For AI inference systems, while GPUs are the primary source of operational carbon, the host systems—including CPUs, memory, and storage—dominate the embodied carbon, accounting for around 75% of the total [

57]. The quantification of these emissions relies on methodologies such as Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) and data from product environmental reports [

57,

60]. Recognizing the importance of this impact, leading research now incorporates embodied emissions into a holistic carbon footprint metric, accounting for both the operational and embodied impacts per user prompt [

7].

AI data centers consume water primarily for cooling the high-density server racks and associated infrastructure required to manage the heat generated by IT equipment [

7]. The efficiency of this water use is benchmarked using the Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE) metric, which measures the liters of water consumed per kilowatt-hour of IT energy. While efficiency varies, Google reports a fleetwide average WUE of 1.15 L/kWh. Based on direct instrumentation of its production environment, a median Gemini Apps text prompt was found to consume 0.26 mL of water [

7]. To mitigate the impact on local water supplies, particularly in high-stress locations, strategies include deploying air-cooled technology during normal operations [

7].

To conclude, this part of the survey systematically details the technical, operational, and financial challenges of AI data center grid integration. We analyze the full spectrum of issues, from long-term planning mismatches and real-time balancing strains to sub-second stability risks and power quality degradation. The analysis also extends to the significant economic and life-cycle environmental impacts. A high-level overview of these critical challenges and their key findings is presented in

Table 5.