This section presents the modeling and simulation methodology used to analyze the integration of renewable energy systems into cheese production. The approach focuses on the most energy-intensive stages, pasteurization, coagulation, and ripening and on their associated electrical and thermal demands. The proposed methodology combines process modeling, energy flow management, and cost and emissions assessment to evaluate the feasibility of a renewable-based, self-sufficient energy solution for cheese production, particularly in rural and decentralized contexts.

2.2. Portuguese Case Study

This study focuses on the main stages of cheese production associated with the highest energy demand, both electrical and thermal, namely pasteurization, coagulation, and ripening. Other production steps were assumed to be performed manually, and were therefore considered negligible in terms of energy consumption.

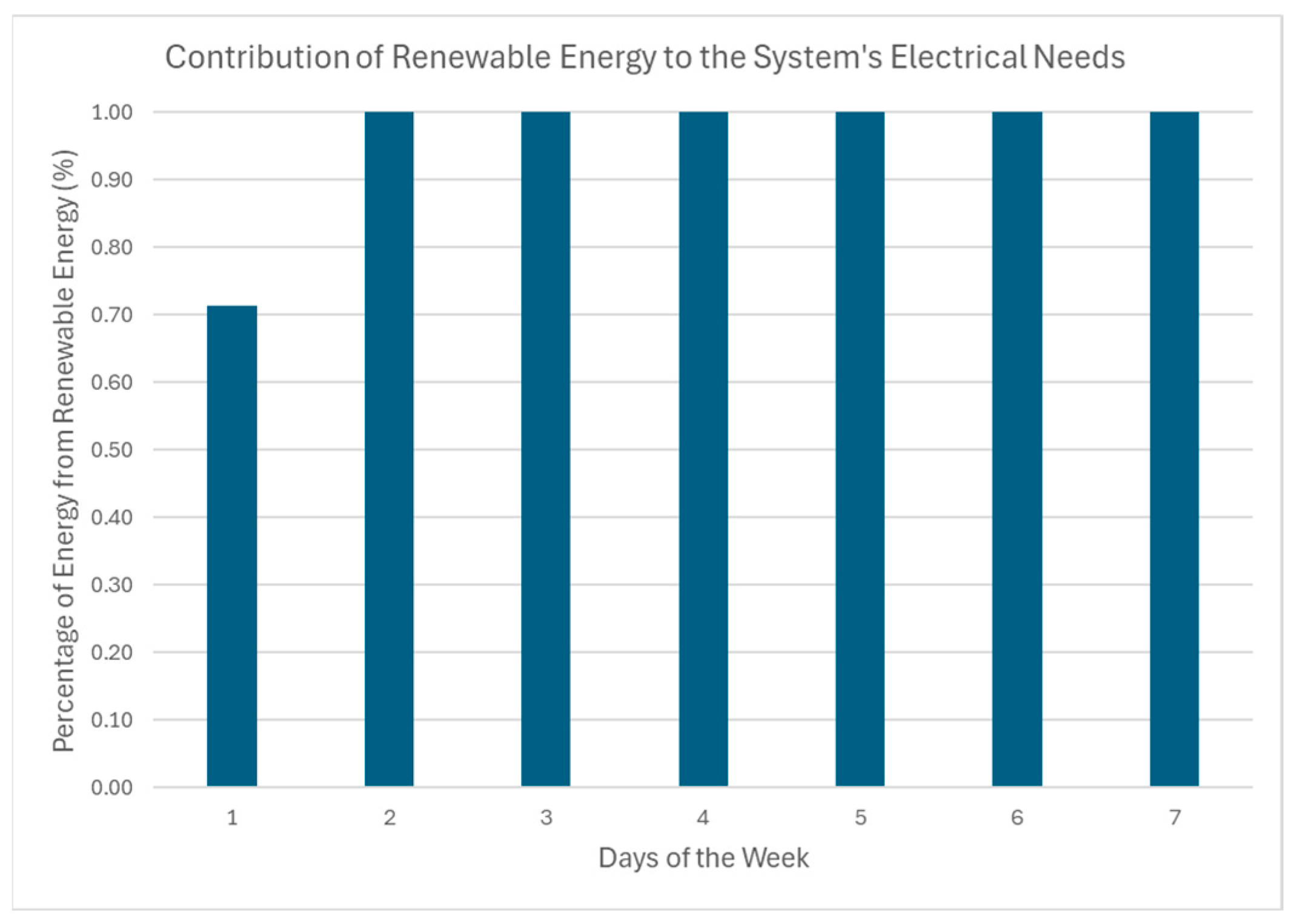

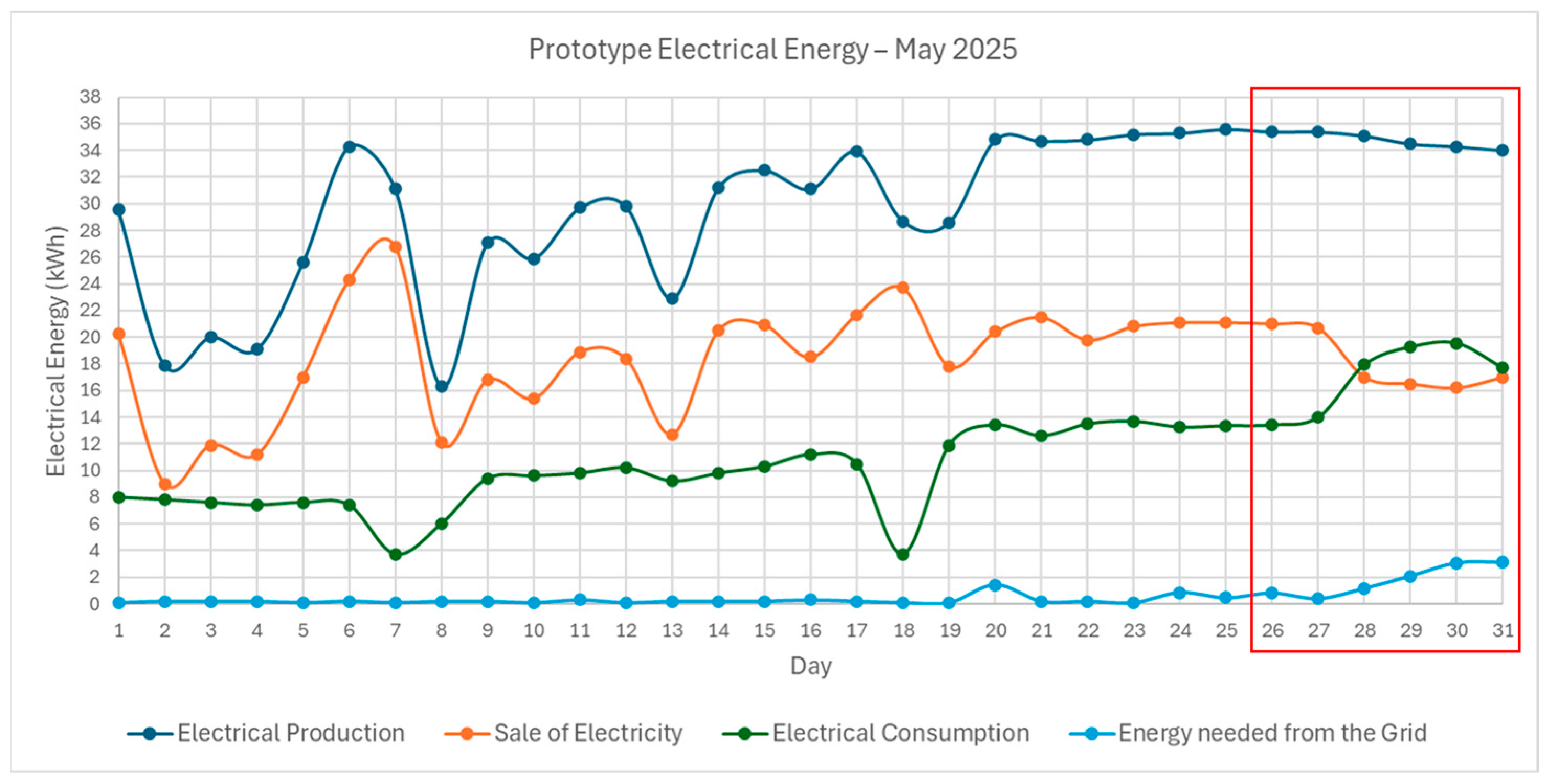

A case analysis was conducted based on a renewable energy prototype installed at the Polytechnic Institute of Beja. In this experimental setup, solar energy was selected as the primary renewable source to meet both electrical and thermal needs, given its strong feasibility for integration into cheesemaking facilities. Wind energy was also included due to its high potential in coastal regions [

38]. Additionally, biomass derived from olive pits and pellets produced from agricultural and industrial residues was considered, taking advantage of the proximity of many cheese factories to agro-industries suppliers of reusable biomass.

The renewable energy sources were allocated to specific cheese production processes. During pasteurization, thermal energy is primarily provided by a heat exchanger in the system’s condensing unit, which recovers waste heat from the refrigeration cycle and transfers it to water that subsequently heats the milk. To reach the required 63 °C, for the low-temperature, long-time (LTLT) pasteurization method, adopted in this study a pellet fueled boiler supplements the total energy demand.

During coagulation, thermal energy from two solar collectors installed on the roof of the facility is used to reach and maintain the milk at 32 °C. Given the lower energy demand compared with pasteurization, and the proven efficiency of solar thermal systems, solar thermal energy alone was deemed sufficient for this stage without backup support.

For ripening, electricity is required to control both temperature and humidity inside the ripening chamber. This demand is met through ten photovoltaic panels and a wind turbine, with surplus energy stored in a battery system for later use. The electrical grid serves as a backup source when renewable generation is insufficient.

To further improve efficiency, phase change materials (PCMs) were integrated inside the ripening chamber. Due to their high latent heat storage capacity, PCMs absorb and release thermal energy during phase transitions, acting as passive thermal stabilizers [

39]. Their inclusion helps maintain the chamber’s temperatures stable, reduce the compressor workload, and lower the overall systems energy demand.

A prototype of the renewable energy system for cheese production was implemented at the Polytechnic Institute of Beja, as shown in

Figure 1. The main equipment and specifications are summarized in

Table 3.

2.3. Simulation Tool’s Algorithm

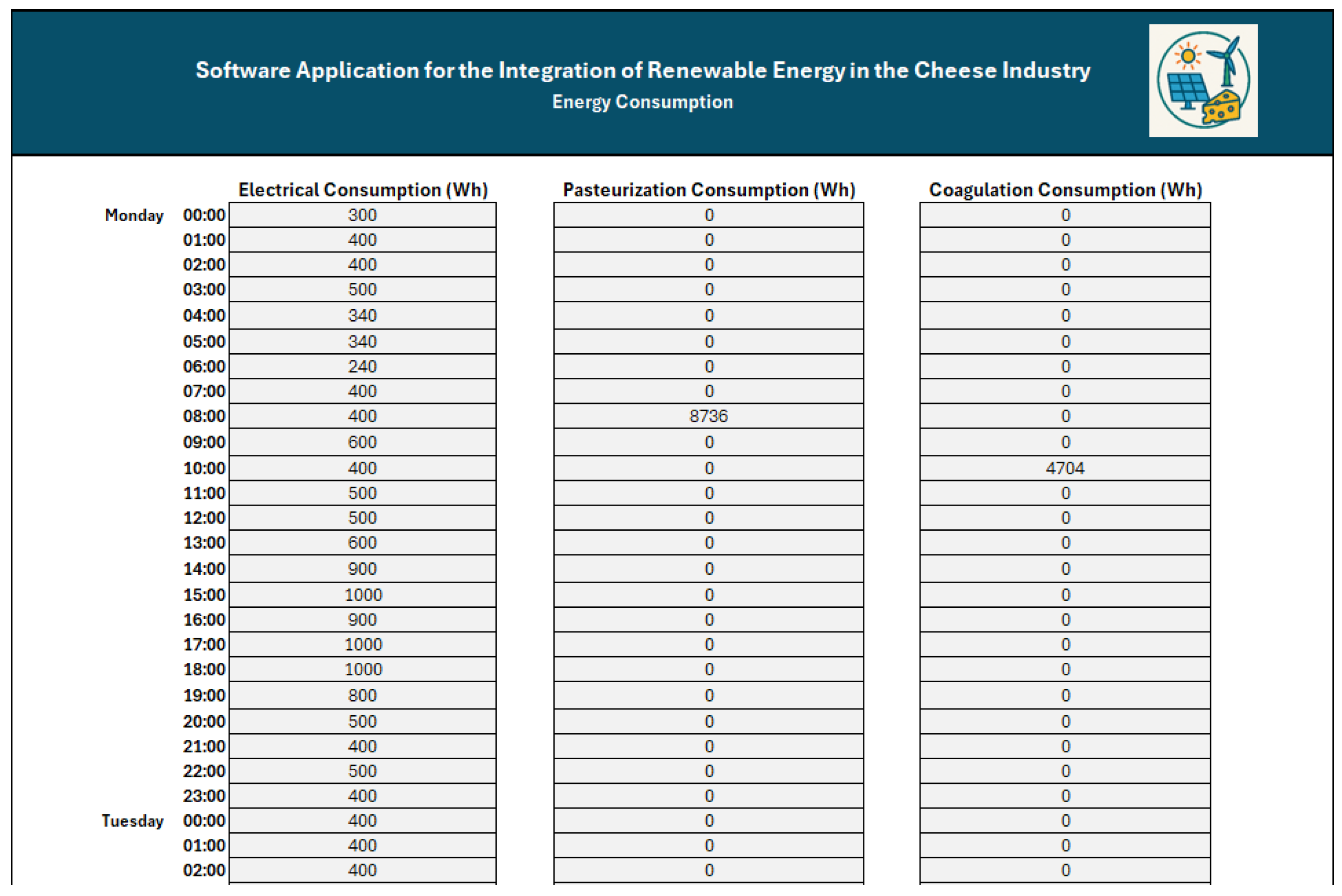

The simulation program was developed with an hourly time-step, corresponding to the smallest interval for which both energy production and consumption data were available. It was designed to evaluate weekly operation scenarios, by assessing the feasibility of the proposed prototype as a self-sufficient energy solution for cheesemaking units located in remote areas.

The development of the simulation program was based on three equally important components: the electrical system, the pasteurization process, and the coagulation process. Each component modeled to simulate energy management required to meet the respective cheese production demands, using locally generated renewable energy, stored energy, or, depending on the energy type, grid electricity or thermal energy from biomass.

The algorithm of the simulation, outlined in the flowchart of

Figure 2, starts with the input of key operational parameters, including electricity cost (defined by contracted power and tariff scheme), feed-in-tariff for surplus electricity, and biomass pellets cost for thermal energy supply.

To determine electricity cost, the applicable tariff structure for the cheesemaking unit was first established through an initial characterization of its consumption profile. This characterization allowed for the correct section of the contracted and the appropriate tariff structures available from electricity providers.

The apparent power was calculated according to the following formulation:

where S represents the apparent power (kVA), P the active power (kW), and cos φ the power factor.

To determine the apparent power, the hourly electricity consumption profile was analyzed, identifying a maximum hourly demand of 1.8 kWh, corresponding to an active power of 1.8 kW. Since no specific information on the power factor was available for the prototype, a typical industrial value of 0.8 was assumed [

40]. Based on these parameters, the apparent power was calculated using Equation (1), resulting in 2.25 kVA.

A 20% safety margin was applied to account for potential consumption fluctuations, resulting in an adjusted apparent power of 2.7 kVA. Comparing this value with the power categories offered by Portugal electricity providers, the closest contracted value was 3.45 kVA, which was therefore adopted for the system under study.

To determine the applicable electricity tariff, the corresponding voltage level had to be identified, as tariffs are structured based on this classification [

41]. According to national regulation, distribution levels are categorized as Low Voltage (≤1 kV), Medium Voltage (1–45 kV), High Voltage (45–110 kV), and Very High Voltage (>110 kW). For Low Voltage consumers, an additional distinction is made between Normal Low Voltage (BTN, ≤41.4 kVA) and Special Low Voltage (BTE, >41.4 kVA).

Since the contracted power of the prototype its below 41.4 kVA and all equipment operates at voltages under 1 kV, the case study falls under the BTN category. Within this segment, tariffs are further differentiated by the number of hourly periods defined [

41]: single-rate tariff, with a uniform price across all hours; bi-hourly tariff, distinguishing between off-peak and peak hours; and tri-hourly tariff, with peak, shoulder, and off-peak periods. In addition, seasonal adjustments are applied quarterly to reflect variations in national electricity demand and distribution grid stress.

Based on these conditions, the electricity pricing schemes defined by the Portuguese Energy Services Regulatory Authority (ERSE) [

42] were applied to the case study. For the analyzed cheesemaking unit, the cost of active energy (EUR/kWh) was calculated according to the applicable tariff structure presented in

Table 4.

In addition to estimating the cost of electricity purchased from the national grid, it is also necessary to account for the cost of pellets, required as an auxiliary thermal energy source for pasteurization, when the heat recovered by the desuperheater is insufficient. According to Nunes et al. [

43], pellet prices are highly variable, depending on the supplier and subject to seasonal and annual fluctuations. For the simulation program, a reference cost of EUR 366 per ton (0.366 EUR/kg) was adopted based on retail market data reported by Jesus [

44].

Renewable self-consumption systems naturally generate surplus electricity, as production may exceed demand during certain hours while the battery remain fully charged. To prevent energy losses, the excess electricity can be exported to the grid. In Portugal, the remuneration depends on the market prices defined by the Iberian Electricity Market Operator (OMIE) and is given by Equation (2).

where R

UPAC is the revenue from electricity sold (EUR), E

supplied is the energy supplied (kWh), OMIE is the arithmetic mean of daily closing prices in Portugal (EUR/kWh), and the 0.9 factor accounts for a 10% market access deduction.

For this study, OMIE prices were averaged for the weeks of 3 to 9 February 2025 and of 26 May to 1 June 2025, which correspond to the scheduled experimental tests. The applicable prices are presented in

Table 5.

After the input of the defined parameter, and as illustrated in

Figure 2, the simulation tool manages the energy flows across the cheese production processes (1.1—curing/electrical subsystem, 2.1—pasteurization, 3.1—coagulation). This management determines the electricity purchased from the grid and the surplus sold to it (1.2), as well as the biomass pellet consumption (2.2). The specific algorithms for each process component are described in the following sections.

Based on the input parameters and simulation results, Equation (3) is then applied to calculate the net energy cost, enabling the assessment of the associated costs or profits for the cheese production unit under study.

where E

Grid is the electricity required from the grid (kWh), Cost

Electricity the grid electricity price (EUR/kWh), E

Sold the energy exported to the grid (kWh), Sale

Electricity the electricity selling price (EUR/kWh), Q

Pellets the pellet mass required for pasteurization (kg), and Cost

Pellets the pellets price (EUR/kg).

In addition, the simulation estimates the environmental impact of the system by calculating the equivalent CO

2 emissions, considering both electricity drawn from the grid and energy provided by the pellet boiler. According to the Portuguese Environment Agency [

46], the most recent emission factors are 0.107 kgCO

2e/kWh for electricity and 0.032 kgCO

2e/kWh for biomass.

where EF

Electricity and EF

Biomass are the emission factors (kgCO

2e/kWh) for electricity and biomass, respectively, and E

Pellets is the energy provided from the pellets boiler (kWh).

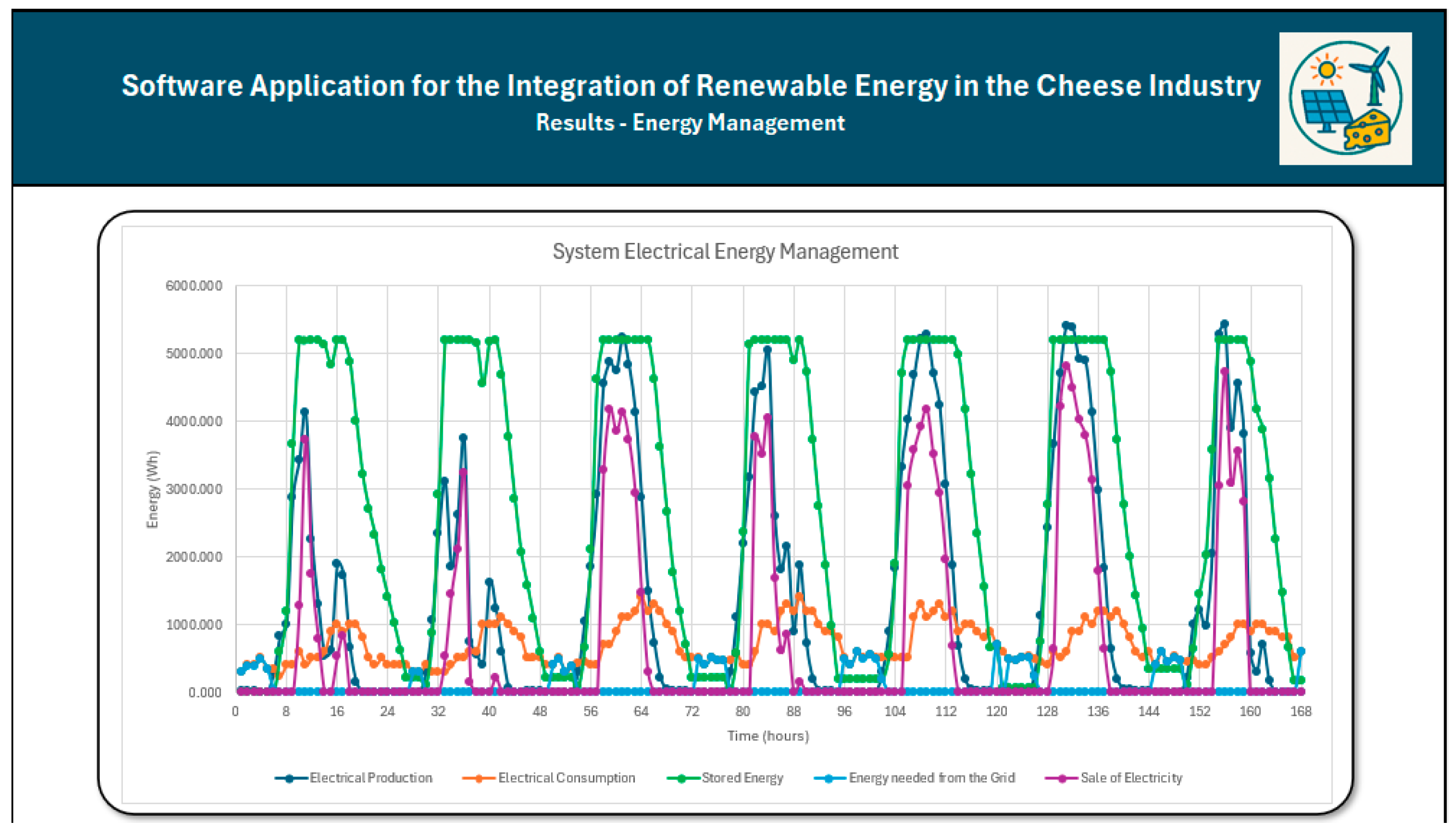

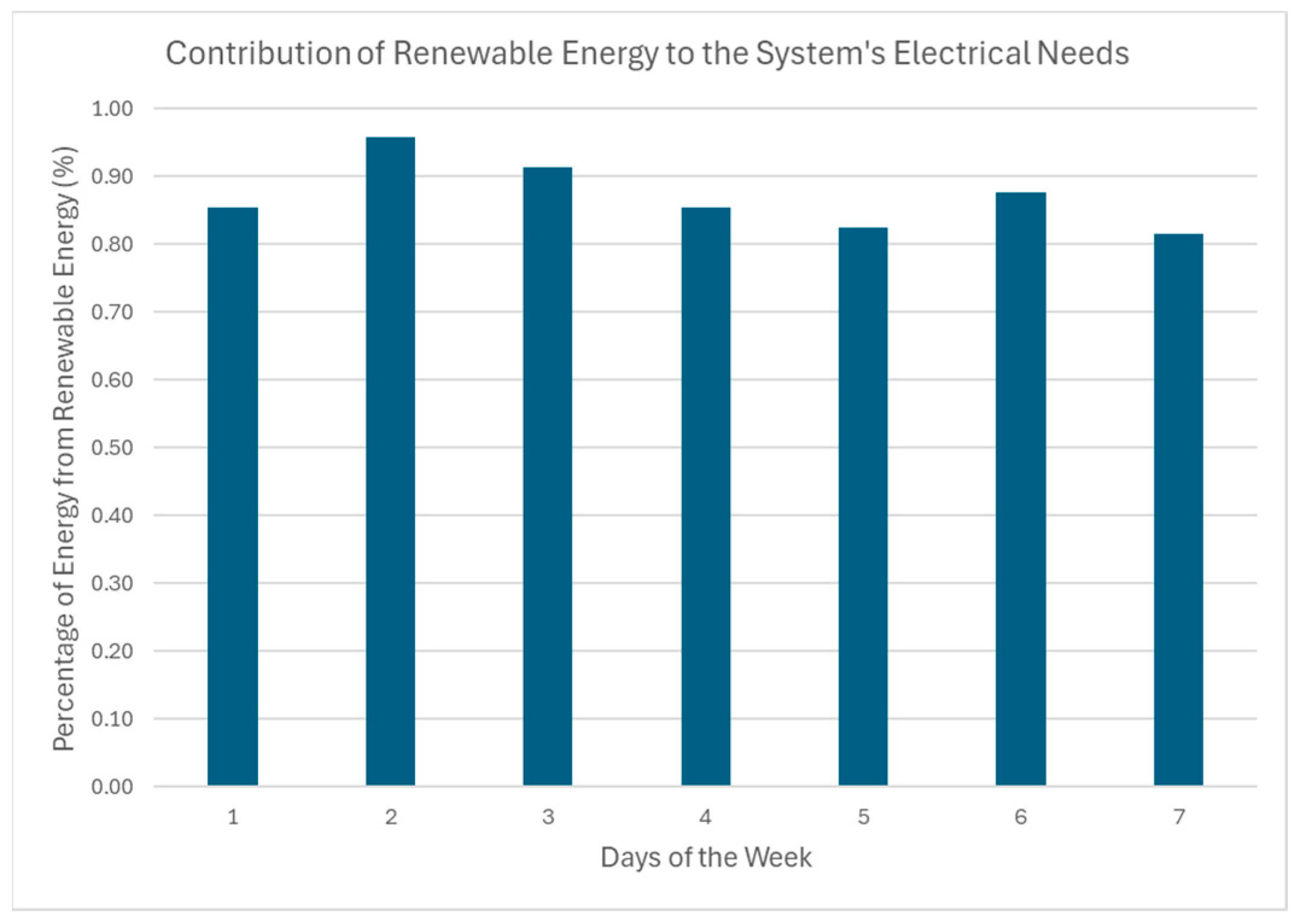

2.3.1. Electrical System

Within the program, the component related to the curing process and overall electrical consumption was designed to maximize the use of photovoltaic and wind generation to cover most of the facility’s demand, with priority given to critical loads such as the condensing unit and evaporator. The management strategy also considers the electrical needs of auxiliary equipment and the storage of surplus energy in the battery to guarantee supply during periods of low renewable generation. As illustrated in

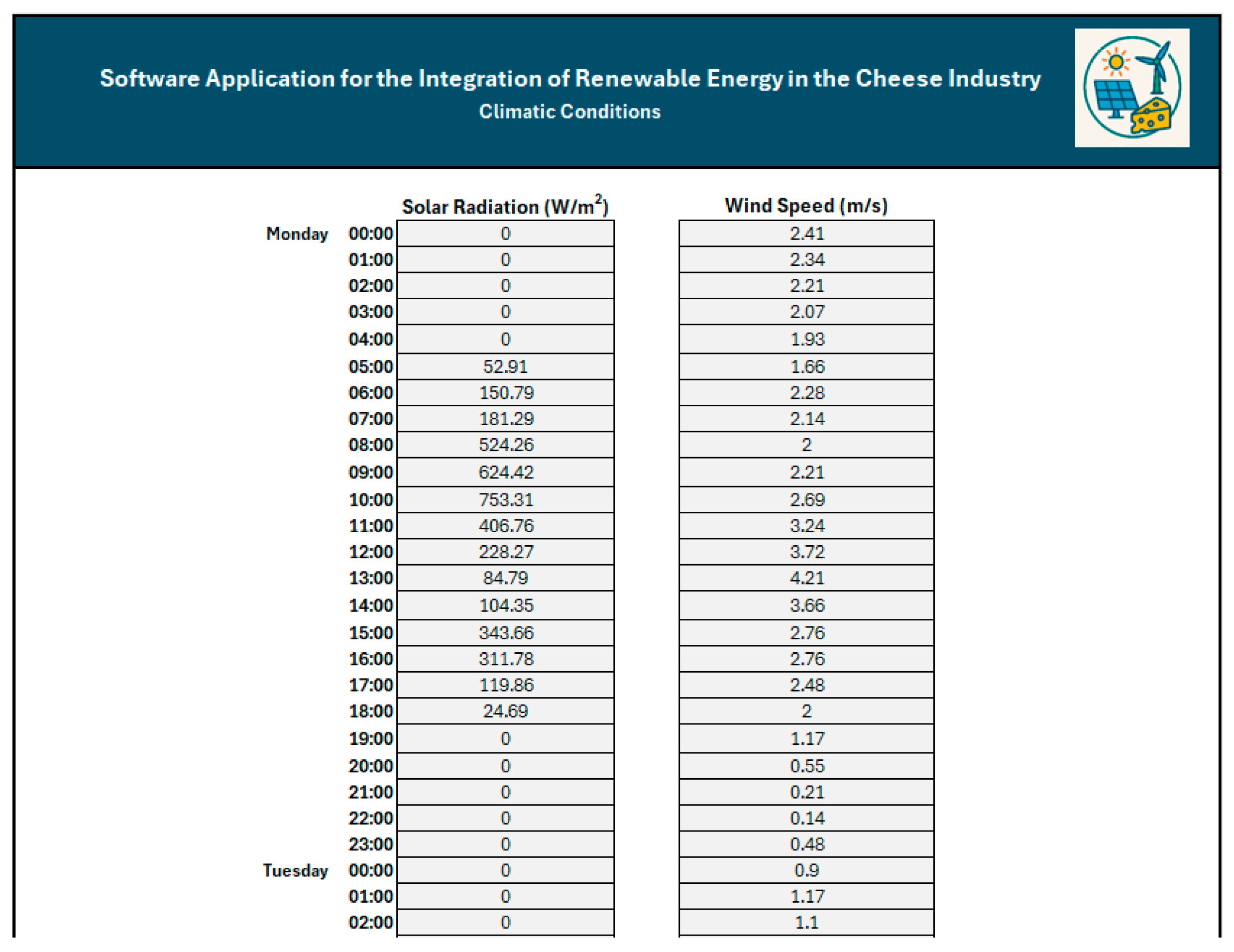

Figure 3, this component requires input variables such as solar radiation, wind speed, electrical demand, and battery capacity. For simulation purposes, the battery was assumed to be fully discharged at the initial time step.

Incident radiation data were obtained from the European Commission’s Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS) [

47]. The SARAH3 database was selected, as recommended for Portugal, and the most recent dataset available (2023) was used. Simulations assumed fixed PV panels, with tilt and azimuth angles optimized through the PVGIS tool. Wind speed data were also retrieved from the PVGIS tool, which provides wind data at 10 m above sea level.

Electricity demand data for the prototype, including the ripening process, were collected from two production weeks (from 3 February to 9 February 2025 and from 26 May to 1 June 2025), using the monitoring system installed on the prototype [

48]. The battery has a maximum usable storage capacity of 5.2 kWh.

Once the input parameters were defined, the electricity generated for self-consumption by the photovoltaic system was first estimated using Equation (5).

where E

solar is the solar energy production [Wh], I

R the incident solar radiation [Wh/m

2], N

P the number of modules, A

P the module surface area [m

2], and η

P the module efficiency.

The maximum number of PV modules is constrained by the available roof area of the cheesemaking facility; therefore, Esolar is limited by the maximum installable PV area, assuming fixed module orientation and neglecting shading effects and electrical losses. Consequently, Equation (5) provides an upper-bound estimate of photovoltaic energy production under ideal operating conditions.

The wind power generated by the turbine corresponds to the kinetic energy of the airflow crossing the rotor blades, which depends on wind speed, air density (1.225 kg/m

3 at sea level), and rotor swept area [

49].

where E

W is the wind energy production [Wh], ρ

ar is air density [kg/m

3], D

rotor the rotor diameter [m], and V

wind wind speed [m/s].

Wind energy production is constrained by the turbine’s start-up and cut-out wind speeds. In the case study, the selected wind turbine operates with a start-up wind speed of 3 m/s and a cut-out wind speed of 45 m/s. Moreover, the achievable wind energy output is further limited by the turbine dimensions compatible with the available installation space at the cheesemaking facility.

Based on the calculated photovoltaic and wind energy, the total electrical energy production was determined using Equation (7).

where E

electrical is the total electrical energy production [Wh], E

solar is the solar energy production [Wh], and E

W is the wind energy production [Wh].

For the curing process and overall electrical consumption, the simulation program first allocates the electricity produced to meet the instantaneous demand. The subsequent energy balance is then determined, calculating either the surplus (when generation exceeds demand) or the deficit (when generation is insufficient). This step assesses energy availability at each time interval and determines the battery storage or grid supply requirements.

where E

after renewables is the energy balance after the use of energy produced by the photovoltaic panels and wind turbine [Wh], E

electrical is the total electrical energy production [Wh], and Cons

electrical is the electrical energy consumption of the system [Wh].

After calculating the energy balance (Equation (8)), a zero result indicates that generation meets demand, with no surplus or deficit, and no further calculation is performed for that time step. A positive balance means that excess electricity from photovoltaic and wind generation is directed to the battery storage for later use. The effective storage capacity is then determined based on the available surplus and the battery’s existing state of charge, as expressed in Equation (9).

where E

storage is the energy available for storage in the battery [Wh], E

after renewables is the energy balance after the use of energy produced by the photovoltaic panels and wind turbine [Wh], and E

Battery (i−1) is the energy stored in the battery in the previous iteration [Wh].

It should be noted that the battery has a maximum usable capacity of 5.2 kWh. If the energy calculated from Equation (9) exceeds this limit, the stored energy is capped at 5.2 kWh, and any surplus is directed to the grid, as described in Equation (10).

where E

sold is the energy exported to the national grid [Wh], E

storage is the energy available for storage in the battery [Wh], and C

Battery is the battery’s maximum usable capacity [Wh].

If the storable energy is lower than the battery’s maximum capacity, the energy effectively stored during that iteration equals the calculated energy (Estorage), thus concluding the step.

Conversely, if the result of Equation (8) is negative, this indicates that renewable sources is insufficient to meet the system’s electrical demand, requiring the use of battery storage. In this case, the program checks whether the available energy in the battery exceeds the absolute value of the energy deficit (E

after renewables), to prevent full discharge. If the available energy in storage is sufficient, the deficit is supplied by the battery, and the remaining energy stored for the next iteration is computed using Equation (11), completing the time step.

where E

Battery is the stored energy available after the use of the battery [Wh], E

Battery (i−1) is the energy stored in the battery in the previous iteration [Wh], and E

after renewables is the energy balance after the use of energy produced by the photovoltaic panels and wind turbine [Wh].

However, if the available battery energy is lower than the energy deficit after renewable energy generation, the remaining system demand is supplied by the national grid.

where E

Grid is the required electrical energy from the national grid to meet the remaining system demand [Wh], and E

after renewables is the energy balance after the use of energy produced by the photovoltaic panels and wind turbine [Wh].

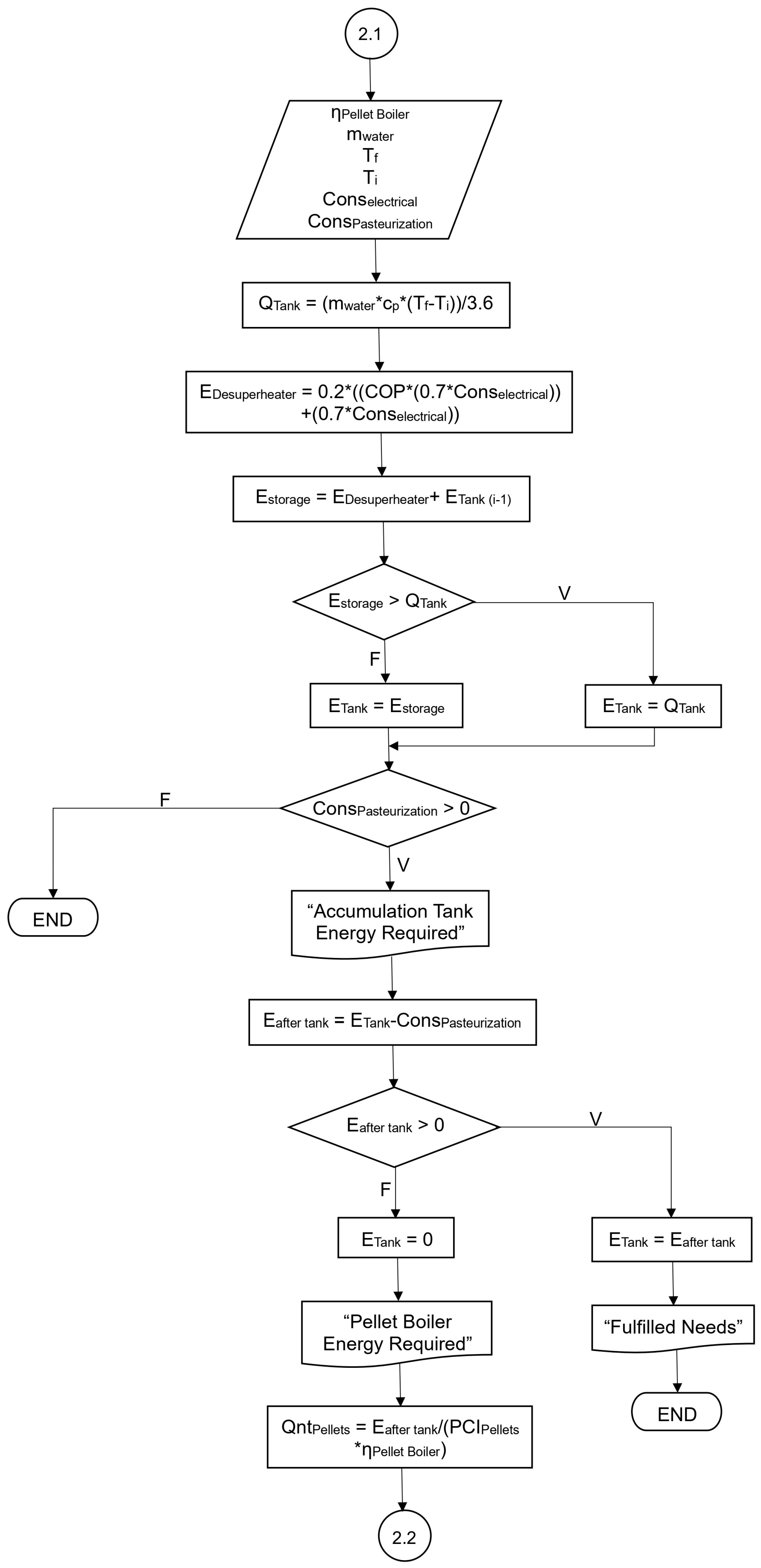

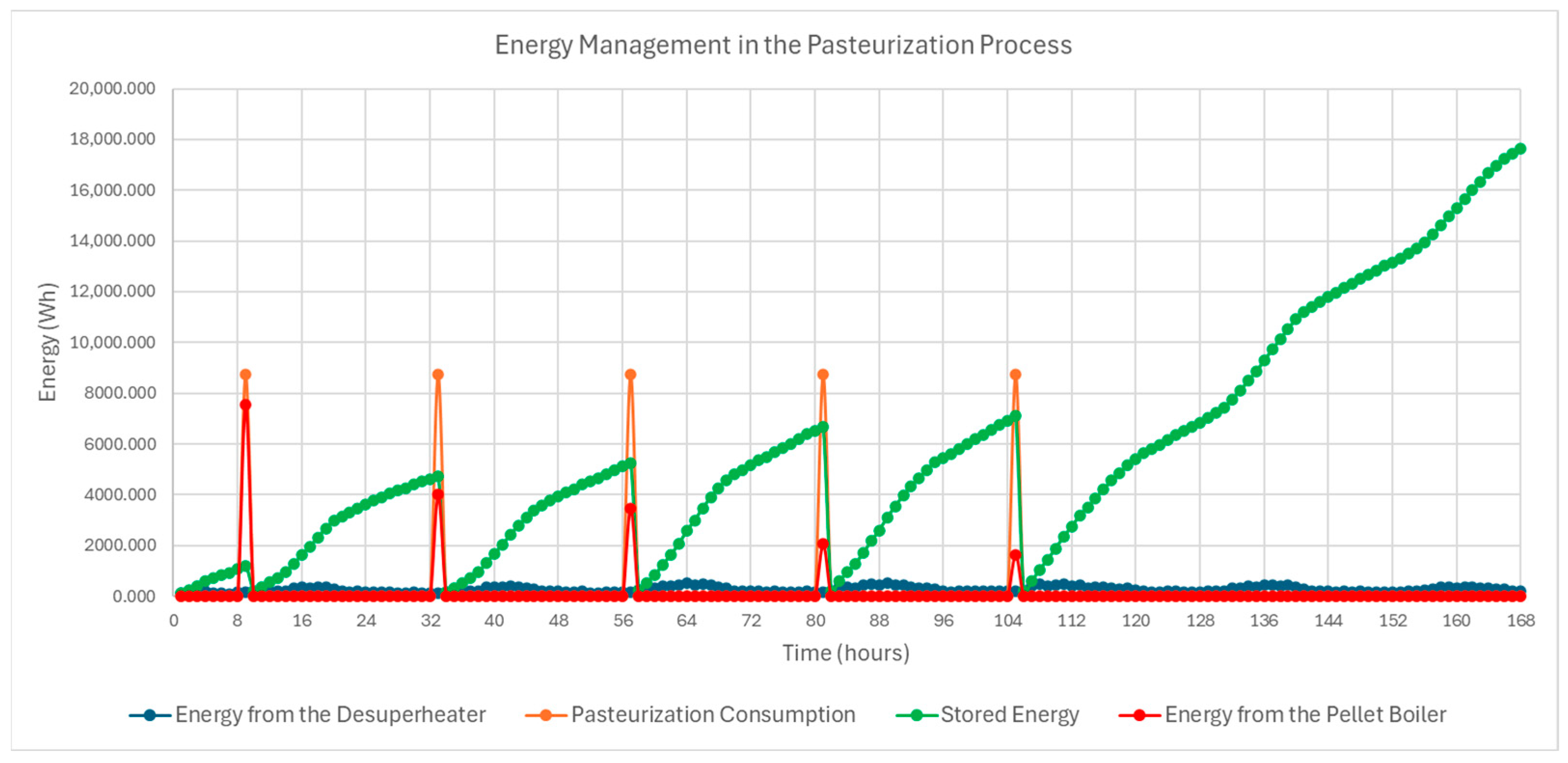

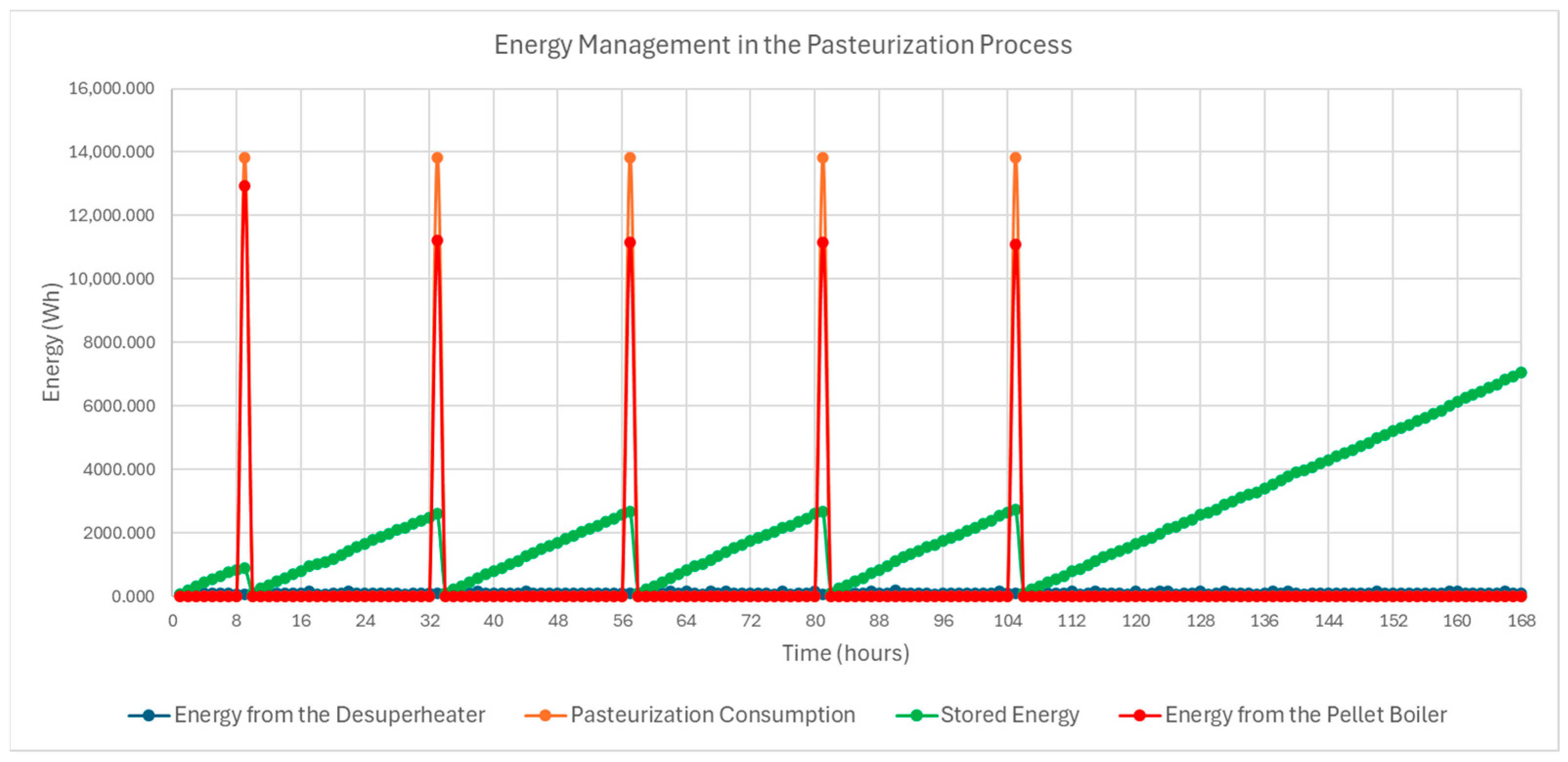

2.3.2. Pasteurization Process

In the simulation of the pasteurization process, the goal is to model its operation using a desuperheater integrated into the refrigeration system of the ripening chamber. The desuperheater heats water stored in an accumulation tank, which is then used to raise and maintain milk temperature. A pellet boiler serves as a backup when the recovered thermal energy is insufficient.

The flowchart in

Figure 4 presents the simulation algorithm developed for the pasteurization process. Similar to the electrical subsystem, the modeling starts with the definition of input variables: electrical demand, pasteurization demand, condensing unit COP, tank thermal capacity, pellet lower heating value, and boiler efficiency. In the first iteration, the thermal energy stored in the tank is set to zero.

Before modelling this component, the tank’s thermal capacity was estimated using Equation (13), based on the initial and final water temperatures and the specific heat of the fluid (4.186 kJ/kgK for water). For the pasteurization process, targeting a milk temperature of 63 °C (LTLT pasteurization process), the water in the accumulation tank was assumed to reach 70 °C. A water density of 1 kg/L was considered, corresponding to a flow rate equal to the tank capacity (500 L), with an initial water temperature of 15 °C.

where Q

Tank is the maximum thermal energy stored in the accumulation tank [Wh], m

water is the water flow rate [kg/s], c

p the specific heat capacity of water [kJ/kgK], T

f the final water temperature in the tank [°C], and T

i the initial water temperature in the tank [°C].

The calculated thermal capacity of the accumulation tank was 31,976.4 Wh, based on the defined temperature range and fluid properties.

Before developing the program component, it was necessary to define the energy consumption of the pasteurization process. As no experimental data were available from the prototype, reference values from the literature were used to ensure reliable simulation inputs.

Average values reported by Ladha-Sabur et al. [

2], based on multiple studies and dairy units, were adopted. The total energy demand for cheesemaking was considered to be 5.04 MJ/kg of cheese (≈1.4 kWh/kg). According to Xu et al. [

31] and Ladha-Sabur et al. [

2] pasteurization accounts for 17–26% of total energy used in a cheesemaking unit. A conservative estimate of 26% was applied in this study, corresponding to 0.364 kWh/kg of cheese.

For the weekly simulation scenario, the operational profile assumes that pasteurization occurs once per day on weekdays at 9 a.m., with no operation during weekends.

After defining these input parameters, the algorithm’s first step, shown in

Figure 4, is to determine the thermal energy recovered by the desuperheater. It is assumed that 70% of the system’s total electricity consumption is attributable to the compressor, based on the fact that, compressors account for represent approximately 53% of total electricity use in traditional Portuguese cheese industries [

6]. Compressors are therefore identified as the most energy-intensive equipment in cheese production.

The system evaluated in this research differs from conventional multi-stage industrial cheese plants, which include pasteurization, coagulation, and various auxiliary services (e.g., HVAC, lighting) by focusing primarily on the ripening chamber and its essential auxiliary equipment, which results in the compressor representing a proportionally larger share of the total electrical demand, thereby justifying the conservative assumption of a 70% share to accurately reflect the system’s overall energy balance, thus avoiding any underestimation of the compressor’s contribution to the overall energy flow and validating the specialized focus of this study.

It is important to note the key differences between the proposed system and conventional cheese industries. In traditional facilities, total electricity consumption includes auxiliary services such as HVAC, lighting, and external equipment, in addition to multiple production stages of cheese (e.g., pasteurization and coagulation). In contrast, the system analyzed in this study considers only the ripening process and auxiliary devices such as pumps, circulators, sensors, and internal lighting of the ripening chamber. Consequently, the compressor represents a larger share of the total electrical consumption.

Finally, the energy recovered by the desuperheater is assumed to correspond to 20% of the heat released during refrigerant condensation, in line with technical recommendations [

50].

where E

Desuperheater is the energy recovered by the desuperheater [Wh], COP is the coefficient of performance of the condensing unit water flow rate, and Cons

electrical is the electrical energy consumption of the system [Wh].

With the thermal energy recovered by the desuperheater calculated, the total storable energy in the accumulation tank can be determined, considering both the energy supplied by the desuperheater and the energy previously stored in the tank from prior iterations.

where E

storage is the energy available for storage in the accumulation tank [Wh], E

Desuperheater is the energy recovered by the desuperheater [Wh], and E

Tank (i−1) is the energy stored in the accumulation tank in the previous iteration [Wh].

Similar to the electrical subsystem with the battery, the pasteurization subsystem must also account for the maximum energy storage capacity of the accumulation tank. Based on the tank’s capacity, if the value calculated from Equation (15) exceeds 31,976.4 Wh, the energy effectively stored is limited to this maximum value, and any excess is considered wasted. Conversely, if the calculated energy is below 31,976.4 Wh, the stored energy equals the calculated energy.

Subsequently, the analysis of the pasteurization process profile shows that during periods of zero thermal demand, the system only stores energy in the accumulation tank, thus concluding this step. When thermal energy is required for pasteurization, the system prioritizes using the previously stored energy.

During pasteurization (i.e., when thermal consumption is greater than zero), it is necessary to verify whether the available energy in the accumulation tank is sufficient to meet the process requirements.

where E

after tank is the energy balance after the use of thermal energy stored in the accumulation tank [Wh], E

Tank is the energy stored in the tank [Wh], and Cons

Pasteurization is the energy required for the pasteurization process [Wh].

After obtaining the result of Equation (16), two scenarios are considered. If the value is positive, the stored energy is sufficient to meet the thermal demand of the pasteurization process, and the remaining energy becomes the initial condition for the next iteration. Conversely, a negative result indicates depletion of the thermal storage, requiring the pellet boiler to provide the additional energy needed. To determine the minimum pellet consumption, it is necessary to identify the lower heating value of the pellets (16 MJ/kg) and the boiler efficiency (93.1%), as expressed in Equation (17).

where Qnt

Pellets is the minimum quantity of pellets required to supply the remaining thermal energy for the pasteurization process [kg], E

after tank is the energy balance after the use of thermal energy stored in the accumulation tank [Wh], PCI

Pellets is the lower heating value of the pellets [MJ/kg], and η

Pellet Boiler is the pellet boiler efficiency [%].

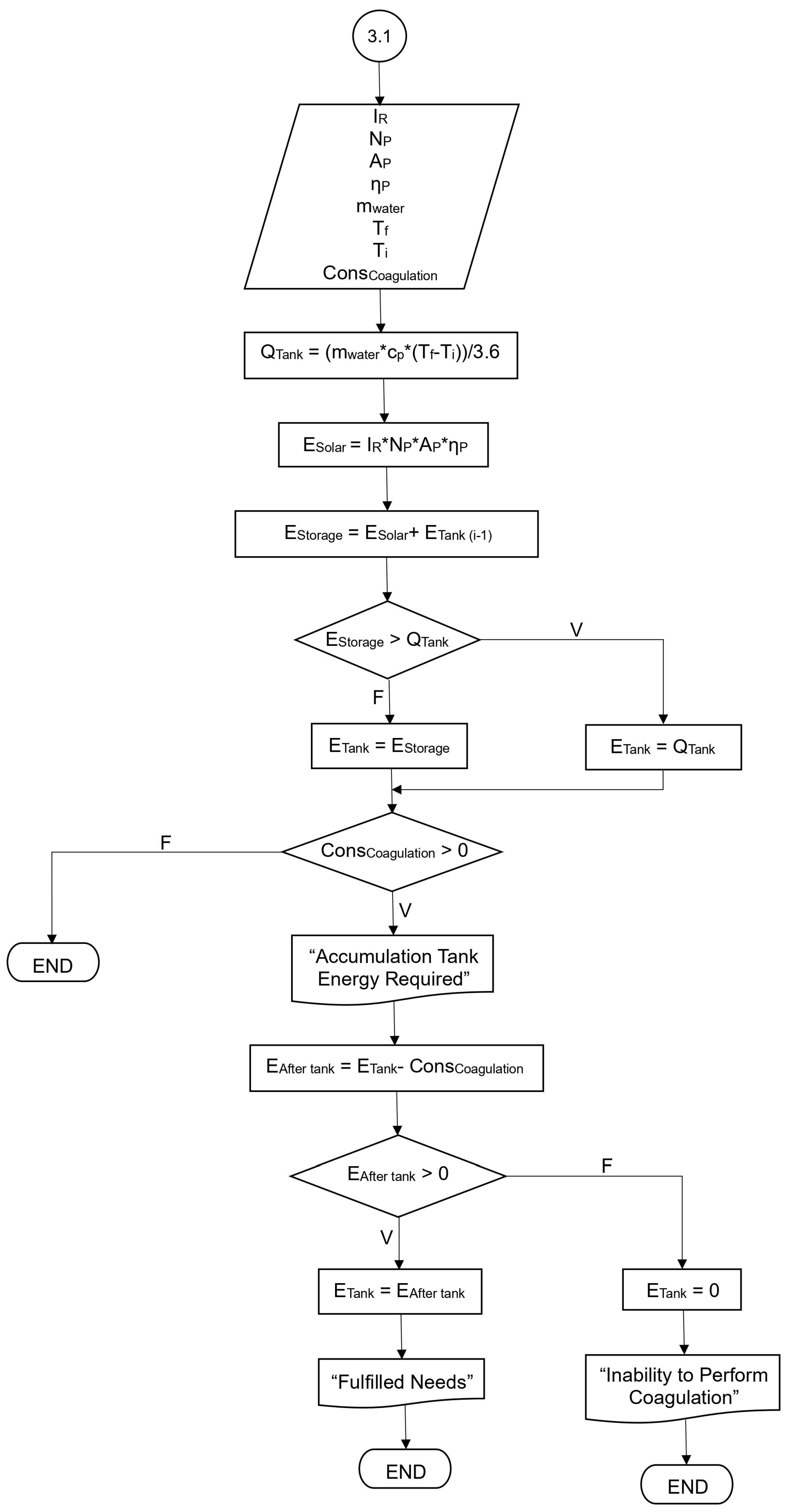

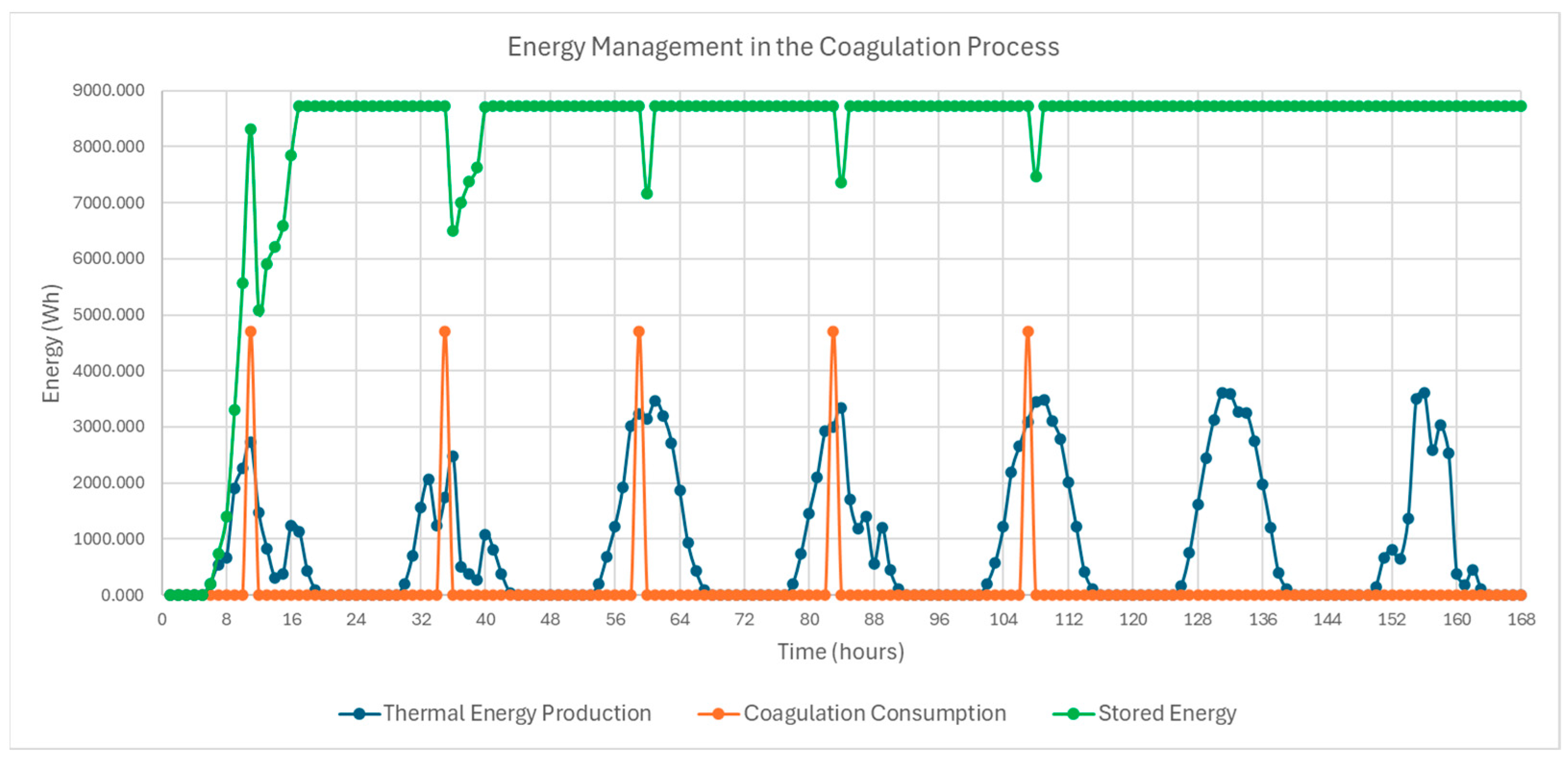

2.3.3. Coagulation Process

Finally, in the software module related to milk coagulation, the program simulates the process for the case under study. At this stage, water in the accumulation tank is heated by two solar collectors providing the thermal energy required to maintain a constant milk temperature during coagulation.

Figure 5 shows the algorithm developed to represent this process. As in previous program stages, the first step is to define input variables, including solar radiation, the technical parameters of the solar collectors, the energy demand of coagulation, and the maximum thermal storage capacity of the accumulation tank. Similar to the pasteurization module, the first iteration assumes zero thermal energy stored in the accumulation tank.

Solar radiation data were obtained from the European Commission’s Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS) [

47]. Based on these inputs parameters, the thermal energy generated for self-consumption by the solar collectors was determined using Equation (5).

The maximum thermal storage capacity of the accumulation tank was estimated using Equation (13), as in the pasteurization module. Since the coagulation temperature is set at 32 °C and maintained for one hour, the water temperature was assumed to reach 40 °C. An initial water temperature of 15 °C and a flow rate equal to the tank’s capacity of 300 L were also considered. The calculated thermal capacity of the tank was 8720.8 Wh, based on the defined temperature range and fluid properties.

The energy demand of the coagulation process was estimated using the same approach applied to pasteurization. Considering a total energy consumption of 5.04 MJ/kg of cheese (≈1.4 kWh/kg) reported by Ladha-Sabur [

2], and assuming a conservative scenario in which coagulation accounts for 14% of total energy use [

31], the corresponding consumption was set at 0.196 kWh/kg of cheese. For the weekly operation of the system, coagulation was scheduled once per day on weekdays at 11 a.m., with no activity during weekends.

After defining the input parameters, the first step of the algorithm related to the coagulation process (

Figure 5) involved calculating the total energy storable in the accumulation tank based on the hourly solar thermal production.

where E

storage is the energy available for storage in the accumulation tank [Wh], E

solar is the thermal solar energy production [Wh], and E

Tank (i−1) is the energy stored in the accumulation tank in the previous iteration [Wh].

Subsequently, as in the pasteurization module, the coagulation subsystem must also account for the maximum energy storage capacity of the accumulation tank. Based on the tank’s thermal capacity and the energy calculated from Equation (18), two scenarios are distinguished: (i) if the calculated energy exceeds 8720.8 Wh, the stored energy is limited to the tank’s maximum capacity; (ii) if the calculated energy is lower than 8720.8 Wh, the stored energy equals the total energy obtained from the calculation.

During periods without coagulation, the system accumulates thermal energy in the tank, and the iteration ends. When coagulation occurs and thermal energy is required, the system draws from previously stored energy. To verify that the available stored energy is sufficient to meet the coagulation process demand, the energy balance after the use of the energy stored in the tank is verified using Equation (19).

where E

after tank is the energy balance after the use of thermal energy stored in the accumulation tank [Wh], E

Tank is the energy stored in the tank [Wh], and Cons

Coagulation is the energy required for the coagulation process [Wh].

The cheese production system analyzed in this study was designed assuming that the two solar collectors can fully meet the thermal energy demand of the coagulation process without a backup system. Therefore, the results of Equation (19) are expected to be positive. In this case, the stored energy for the next iteration equals the calculated value, and the simulation concludes. Conversely, in the unlikely event that the result of Equation (19) is negative, the stored energy is set to zero, and the simulation ends without performing the coagulation process.