Application of Agrivoltaic Technology for the Synergistic Integration of Agricultural Production and Electricity Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Reducing irrigation requirements by up to 20%;

- Collecting rainwater for irrigation systems;

- Reducing wind erosion;

- Using the photovoltaic system substructure to attach nets or protective sheets to crops;

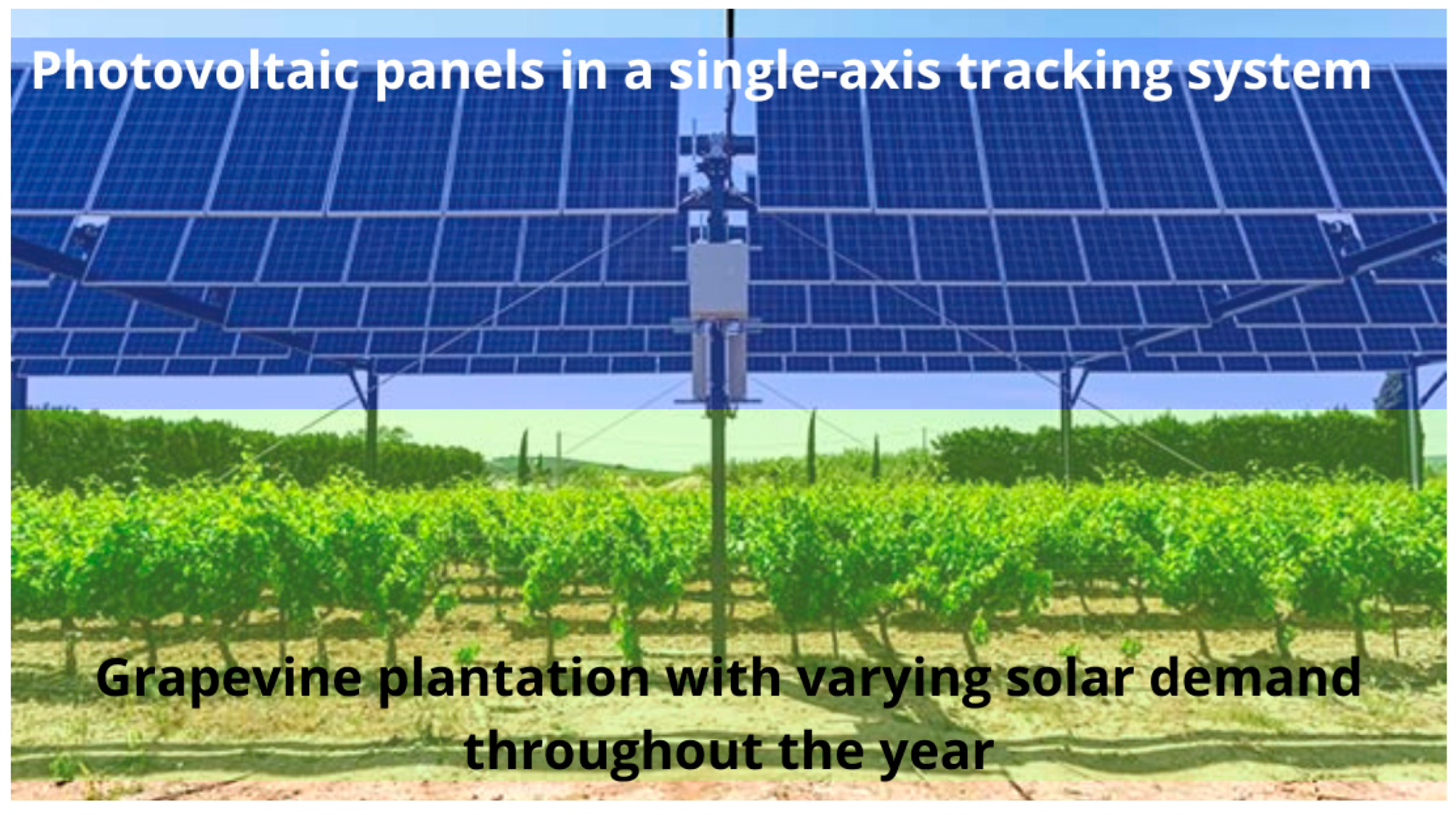

- Optimising the available light for crops, for example by using photovoltaic systems that track radiation;

- Increasing the efficiency of photovoltaic modules through improved convective cooling;

- Increasing the efficiency of double-sided PV modules, which utilise light from both sides, thanks to greater distances between PV modules and between PV modules and the ground and adjacent rows;

- Creating new fields of electrification and automation in agriculture;

- Balancing the electricity generation profile in the power grid.

- Additional benefits for agriculture, including protection against hail, frost and drought damage;

- Local electricity generation in poorly electrified areas;

- Lower average cost of electricity (LCOE) compared to small rooftop photovoltaic systems;

- Diversification of farmers’ income (important, for example, in times of high fertiliser prices due to rising energy and gas prices, which poses a threat to the continuity of agricultural production).

2. Topologies of Agrophotovoltaic Systems

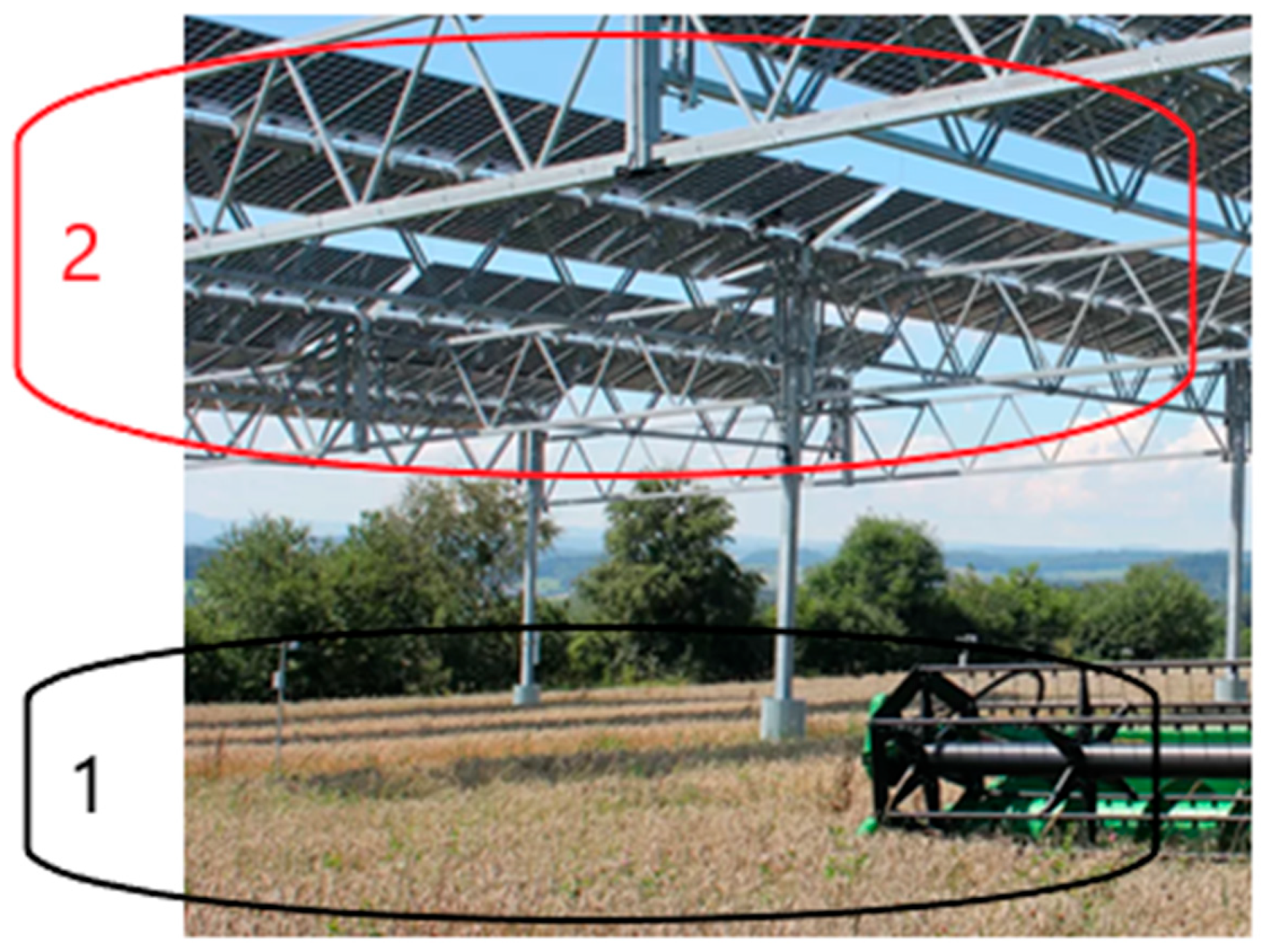

- Photovoltaic modules installed on the ground, either stationary or using sun-tracking systems, with spacing between the structures and existing crops;

- Photovoltaic modules installed above crops, either stationary or using sun-tracking systems;

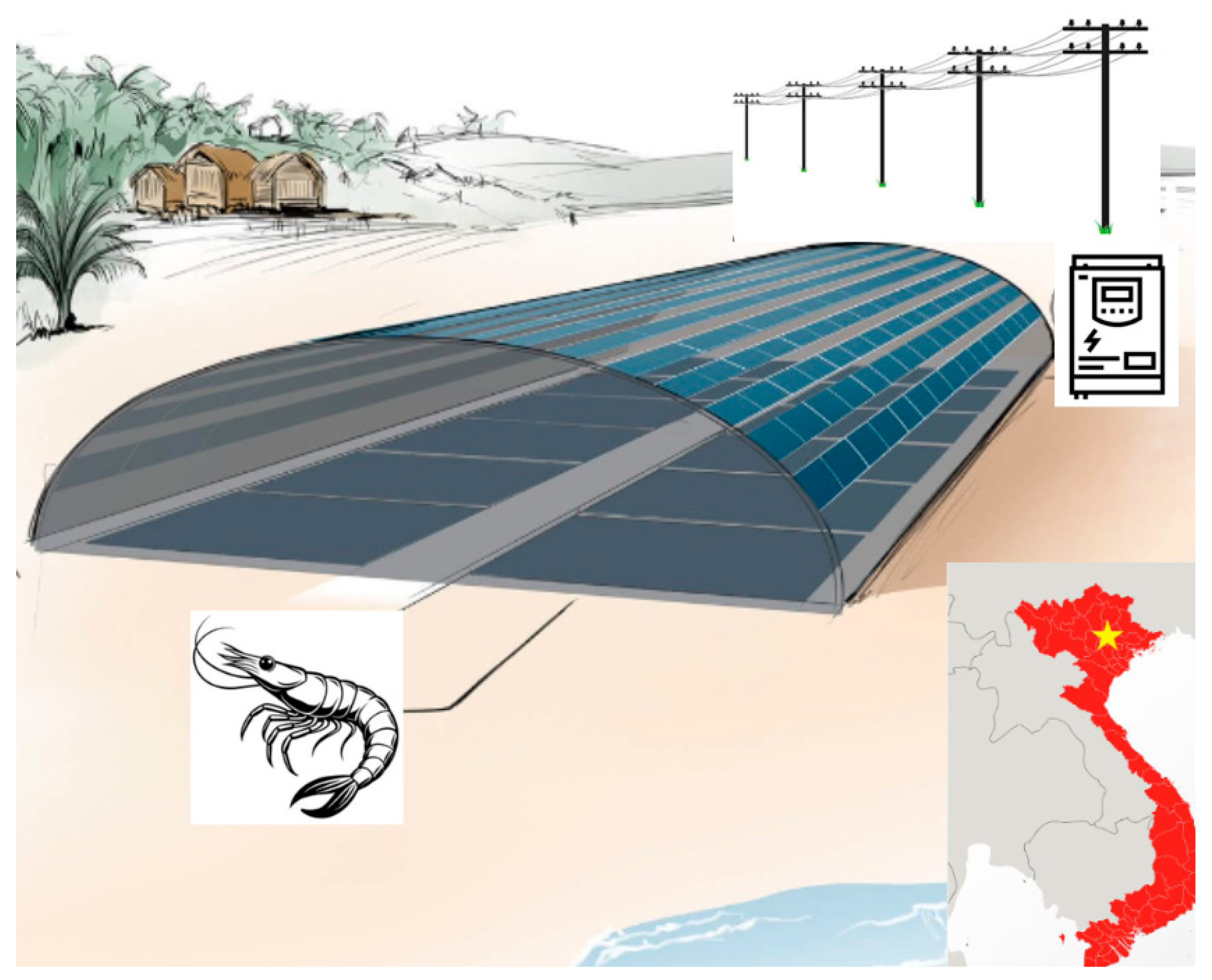

- The use of photovoltaic greenhouses that integrate classic solutions used in horticulture and agriculture with photovoltaic cells arranged to maintain partial transparency, or double-sided cells with a specific degree of transparency that utilise reflected radiation.

3. Factors Optimising the Performance of APV Systems

3.1. Method of Installing Photovoltaic Modules

3.2. Height of Photovoltaic Module Installation

3.3. Distances Between Modules and Rows of Photovoltaic Modules

3.4. Degree of Ground Shading and Microclimate Change in APV Systems

3.5. Rainwater Management

3.6. Photovoltaic Module Technology for APV Systems

- -

- Type of crop (deciduous, berries, vegetables, root crops, fruit trees, herbs, cereals, pasture, etc.);

- -

- Required transparency (20–40% for deciduous plants, 15–35% for berries);

- -

- Installation priority (maximization of energy yield, radiation transparency, or crop yield for a given type of crop);

- -

- Planned crop mechanization (row spacing, pole height, etc.);

- -

- Local climate.

- -

- Semi-transparent PV modules: increased spacing between PV cells ensures an optimal amount of sunlight reaching the plants, reducing heat stress and ensuring even distribution of shade;

- -

- Bifacial PV modules: the ability to utilize radiation reflected from the ground/plants and additional electricity generation;

- -

- Glass-glass modules: high resistance to moisture (compared to modules with a back film, which has lower resistance to moisture, ammonia, and agricultural chemicals), temperature stability, usability;

- -

- Modules with increased PV cell spacing (spaced-cell): possibility of adjusting transparency to a specific type of crop in order to ensure precise shading.

3.7. Type of Crops Grown

3.8. Sun-Tracking Systems

4. Legal Aspects of PV Installations in Agriculture

5. Mathematical Modelling in Agrivoltaics

5.1. Solar Radiation Distribution Model

- Rshade—shading coefficient introduced by the APV system,

- I(1 − Rshade)—amount of solar radiation reaching crop type k; λ—effect of solar radiation on the yield of crop type k.

5.2. Microclimate and Crop Growth Model

5.2.1. Exponential-Linear Model

5.2.2. Logistic Growth Curve

5.2.3. Gompertz Model

5.2.4. GENECROP Growth Model

5.3. Modelling Economic Aspects

- Good connection to the grid in terms of proximity and connection capacity;

- Cultivation of permanent and protection-requiring row crops;

- Low level of machinery use;

- Possibility of low foundation of support structures for PV modules above crops that accept limited height;

- Cultivation area of more than 1 ha;

- High and flexible level of energy consumption in the facility (cooling, drying, processing);

- The investor’s readiness to carry out the investment.

- Simple, limiting the time horizon of the calculation to one year;

- Advanced (discounted), covering the entire construction period and the assumed operating period of a given investment project.

6. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

- -

- Dual use of land (for agricultural and energy purposes);

- -

- Protection of plants against excessive sunlight, intense UV radiation, burns, hail, heavy rain;

- -

- Protection of plants and fruits against diseases (e.g., mold);

- -

- Better water management (slower evaporation, lower water consumption for irrigation);

- -

- More stable crop yields (especially during droughts and high temperatures), and some crops (such as raspberries, blueberries, grapes, lettuce, herbs) can even produce higher yields;

- -

- Additional income for the investor/farm (additional electricity for own use or resale) and the possibility of obtaining additional forms of support (subsidies, tax relief);

- -

- Reduction of farm losses (e.g., by avoiding crop damage from frost, hail, rain), lower agricultural crop insurance rates;

- -

- Reduction of the temperature of PV cells placed above plants, which cool them by evaporating, thus increasing energy yield;

- -

- Increasing the farm’s resilience to climate change (APV is treated as a tool for adaptation to climate change).

- -

- Higher investment costs compared to traditional PV systems (higher and more mechanically resistant structures, more difficult and time-consuming installation, lower installed power per unit area due to increased spacing between PV cells and the need to ensure sufficient light reaching the plants);

- -

- Complex legal procedures (in many countries, there are no regulations for APV systems, the need to pay two taxes: agricultural and business, the need to obtain environmental decisions as for PV farms);

- -

- Difficult mechanization of crops (restrictions on the height/type of agricultural machinery, changes in irrigation and spraying methods, reconfiguration of crop settings);

- -

- Inability to use APV systems for all types of crops (reduced yields of light-loving plants such as corn or wheat);

- -

- More difficult APV system design, focused on a specific type of crop and inability to change the type of crop over the years (specific plant species require a specific amount of sunlight, shade, angle of inclination, etc.);

- -

- Difficult access and servicing of APV installations (due to ongoing crop cultivation).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skawińska, E.; Zalewski, R.I. New Foods as a Factor in Enhancing Energy Security. Energies 2024, 17, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svazas, M.; Navickas, V. The Synergy Potential of Energy and Agriculture—The Main Directions of Development. Energies 2025, 18, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M.; Kang, J.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S.; Bopp, G.; Ehmann, A.; Weselek, A.; Högy, P.; Obergfell, T. Combining food and energy production: Design of an agrivoltaic system applied in arable and vegetable farming in Germany. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhijazi, A.A.K.; Almasri, R.A.; Alloush, A.F. A Hybrid Renewable Energy (Solar/Wind/Biomass) and Multi-Use System Principles, Types, and Applications: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolson, N.; Prieto, P.; Patzek, T. Capacity factors for electrical power generation from renewable and nonrenewable sources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2205429119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asa’a, S.; Reher, T.; Rongé, J.; Diels, J.; Poortmans, J.; Radhakrishnan, H.S.; van der Heide, A.; Van de Poel, B.; Daenen, M. A multidisciplinary view on agrivoltaics: Future of energy and agriculture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 200, 114515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipanagi, A.; Taylor, N.; Jaeger-Waldau, A. Overview of the Potential and Challenges for Agri-Photovoltaics in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Sollazzo, L.; Mangherini, G.; Diolaiti, V.; Vincenzi, D. A Comprehensive Review of Agrivoltaics: Multifaceted Developments and the Potential of Luminescent Solar Concentrators and Semi-Transparent Photovoltaics. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelea, S.; Trommsdorff, M.; Schlaaka, A.; Obergfell, T.; Bopp, G.; Reise, C.; Braun, C.; Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Högy, P.; et al. Implementation of agrophotovoltaics: Techno-economic analysis of the price-performance ratio and its policy implications. Appl. Energy 2020, 265, 114737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurasz, J.; Canales, F.A.; Kies, A.; Guezgouz, M.; Beluco, A. A review on the complementarity of renewable energy sources: Concept, metrics, application and future research directions. Sol. Energy 2020, 195, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña-González, R.C.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, O.; Canul-Reyes, D.A. Analysis of seasonal variability and complementarity of wind and solar resources in Mexico. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report IRENA 2024/2025 Renewable Energy Statistics 2023; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2025/Mar/IRENA_DAT_RE_Capacity_Highlights_2025.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Trommsdorff, M.; Gruber, S.; Keinath, T.; Hopf, M.; Hermann, C.; Schönberger, F.; Zikeli, S.; Ehmann, A.; Weselek, A.; Bodmer, U.; et al. Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition, 2nd ed.; Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE: Freiburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven, D.J.; Capellan-Peréz, I.; Arto, I.; Cazcarro, I.; De Castro, C.; Patel, P.; Gonzalez-Eguino, M. The potential land requirements and related land use change emissions of solar energy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Z.A. Solar energy development on farmland: Three prevalent perspectives of conflict, synergy and compromise in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 101, 103145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusuya, K.; Vijayakumar, K. A comparative study of floating and ground-mounted photovoltaic power generation in Indian contexts. Clean. Energy Syst. 2024, 9, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, M.Á.; Fialho, L.; Moreda, G.P.; Baptista, F. Assessment of the impact of utility-scale photovoltaics on the surrounding environment in the Iberian Peninsula. Alternatives for the coexistence with agriculture. Sol. Energy 2024, 271, 112446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorati, C.; Hormigos, F.C.; Perpiña, C.C.; Quaranta, E.; Taylor, N.; Kakoulaki, G.; Uihlein, A.; Auteri, D.; Dijkstra, L. Renewable Energy in EU Rural Areas: Production, Potential and Community Engagement; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vela, A. Ample Land for Sustainable Renewables Expansion in Europe, New Study Reveals. 24 July 2024. Available online: https://eeb.org/ample-land-for-sustainable-renewables-expansion-in-europe-new-study-reveals/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Sarr, A.; Soro, Y.M.; Tossa, A.K.; Diop, L. Agrivoltaic, a Synergistic Co-Location of Agricultural and Energy Production in Perpetual Mutation: A Comprehensive Review. Processes 2023, 11, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, M.D.; Vallin, H.E.; Roberts, B.P. Animal board invited review: Grassland-based livestock farming and biodiversity. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 16, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perna, A.; Grubbs, E.K.; Agrawal, R.; Bermel, P. Design Considerations for Agrophotovoltaic Systems: Maintaining PV Area with Increased Crop Yield. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 46th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), Chicago, IL, USA, 16–21 June 2019; pp. 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M.; Gruber, S.; Keinath, T.; Hopf, M.; Hermann, C.; Schönberger, F.; Högy, P.; Zikeli, S.; Ehmann, A.; Weselek, A.; et al. Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and Energy Transition: A Guideline for Germany, Germany, 2020. Available online: https://share.google/j9rHIirLVHk85vCQC (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Willockx, B.; Lavaert, C.; Cappelle, J. Performance evaluation of vertical bifacial and single-axis tracked agrivoltaic systems on arable land. Renew. Energy 2023, 217, 119181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzberger, A.; Zastrow, A. On the Coexistence of solar-energy Conversion and Plant Cultivation. Int. J. Sol. Energy 1982, 1, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P.; et al. Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Ehmann, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Schindele, S.; Högy, P. Agrophotovoltaic systems: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahrawi, A.A.; Aly, A.M. A Review of Agrivoltaic Systems: Addressing Challenges and Enhancing Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, H.H.; Kim, Y.O.; Kuk, Y.I. Crop Cultivation Underneath Agro-Photovoltaic Systems and Its Effects on Crop Growth, Yield, and Photosynthetic Efficiency. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; On, Y.; So, J.; Yoon, C.-Y.; Kim, S. Hybrid Performance Modeling of an Agrophotovoltaic System in South Korea. Energies 2022, 15, 6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France Enters the “2.0 Era of Agrivoltaics” and Aims to Install up to 2 GW per Year by 2026. Available online: https://strategicenergy.eu/france-agrivoltaic/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Movellan, J. Japan Next-Generation Farmers Cultivate Crops and Solar Energy. Available online: https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/solar/japan-next-generation-farmerscultivate-agriculture-and-solar-energy/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target Program. Effective Date: 26 April 2018. Available online: https://www.mass.gov/doc/agricultural-solar-tariff-generation-unit-guideline-clean/download (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Thaler, S.; Berger, K.; Eitzinger, J.; Mahnaz, A.; Shala-Mayrhofer, V.; Zamini, S.; Weihs, P. Radiation Limits the Yield Potential of Main Crops Under Selected Agrivoltaic Designs—A Case Study of a New Shading Simulation Method. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqua-PV: “SHRIMPS” Project Combines Aquaculture and Photovoltaics. 2019. Available online: https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/press-media/news/2019/aqua-pv-project-shrimps-combines-aquaculture-and-photovoltaics.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Hrabanski, M.; Verdeil, S.; Ducastel, A. Agrivoltaics in France: The multi-level and uncertain regulation of an energy decarbonisation policy. Rev. Agric. Food. Environ. Stud. 2024, 105, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, C.-Y. An Efficient Structure of an Agrophotovoltaic System in a Temperate Climate Region. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artru, S.; Garré, S.; Dupraz, C.; Hiel, M.-P.; Blitz-Frayret, C.; Lassois, L. Impact of spatio-temporal shade dynamics on wheat growth and yield, perspectives for temperate agroforestry. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 82, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrivoltaics. Available online: https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/key-topics/integrated-photovoltaics/agrivoltaics.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Sekiyama, T.; Nagashima, A. Solar Sharing for Both Food and Clean Energy Production: Performance of Agrivoltaic Systems for Corn, A Typical Shade-Intolerant Crop. Environments 2019, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macknick, J.; Hartmann, H.; Barron-Gafford, G.; Beatty, B.; Burton, R.; Choi, C.S.; Matthew, D.; Davis, R.; Figueroa, J.; Garrett, A.; et al. The 5 Cs of Agrivoltaic Success Factors in the United States: Lessons from the InSPIRE Research Study; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, M.; Doi, T.; Yoshida, Y. A field experiment and the simulation on agrivoltaic-systems regarding to rice in a paddy field. J. Jpn. Soc. Energy Resour. 2016, 37, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, K.T.; Heins, B.J.; Buchanan, E.S.; Reese, M.H. Evaluation of solar photovoltaic systems to shade cows in a pasture-based dairy herd. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 2794–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombi, A. Sustainable Agrivoltaics: Synergies Between Solar Energy and Agriculture. Univergy Solar. 2025. Available online: https://univergysolar.com/en/sustainable-agrivoltaics-synergies-between-solar-energy-and-agriculture/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Golaś, P.; Litwiniuk, P. Ekonomiczne, Prawne i Społeczne Uwarunkowania Produkcji i Korzystania z Odnawialnych Źródeł Energii [Legal and Social Conditions of Production and Use of Renewable Energy Sources]; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371540899_Ekonomiczne_prawne_i_spoleczne_uwarunkowania_produkcji_i_korzystania_z_odnawialnych_zrodel_energii_red_P_Golasa_P_Litwiniuk (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Panchenko, V.A.; Kovalev, A.A.; Chakraborty, S. Agrivoltaics and green hydrogen–Symbiosis of solar energy technologies for sustainable development of humanity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 153, 150205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harres, K. Agri-Photovoltaics—Harvesting Energy and Crops; Fraunhofer ISE: Freiburg, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://biooekonomie.de/en/topics/in-depth-reports/agri-photovoltaics-harvesting-energy-and-crops/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Weselek, A. The Impact of Agrivoltaics on Crop Production; Universität Hohenheim: Stuttgart, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://opus.uni-hohenheim.de/volltexte/2022/2078/pdf/Dissertation_Axel_Weselek.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Deutsches Institut für Normung e.v. Agri-Photovoltaik-Anlagen—Anforderungen an Die landwirtschaftliche Hauptnutzung: Agri-Photovoltaic Systems—Requirements for Primary Agricultural Use; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2021; DIN SPEC 91434:2021-05; Available online: https://www.beuth.de/de/technische-regel/din-spec-91434/337886742 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Ketzer, D.; Schlyter, P.; Weinberger, N.; Rosch, C. Driving and restraining forces for the implementation of the Agrophotovoltaics system technology—A system dynamics analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loik, M.E.; Carter, S.A.; Alers, G.; Wade, C.E.; Shugar, D.; Corrado, C.; Jokerst, D.; Kitayama, C. Wavelength-selective solar photovoltaic systems: Powering greenhouses for plant growth at the food-energy-water nexus. Earth Future 2017, 5, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, R.; Aneli, S.; Gagliano, A.; Tina, G.M. Optimal Photovoltaic Array Layout of Agrivoltaic Systems Based on Vertical Bifacial Photovoltaic Modules. Sol. RRL 2024, 8, 2300505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corab, S.A. i Kelfield Rozwiną Projekty Agrowoltaiczne o Mocy Ponad 1 GW. Available online: https://pap-mediaroom.pl/biznes-i-finanse/corab-sa-i-kelfield-rozwina-projekty-agrowoltaiczne-o-mocy-ponad-1-gw (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Choi, C.S.; Macknick, J.; Li, Y.; Bloom, D.; McCall, J.; Ravi, S. Environmental co-benefits of maintaining native vegetation with solar photovoltaic infrastructure. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2023EF003542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, P.; Pande, P.C.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, D.; Singh, R.K. Agri-voltaics or solar farming: The concept of integrating solar PV based electricity generation and crop production in a single land use system. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2017, 7, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, C.; Marrou, H.; Talbot, G.; Dufour, L.; Nogier, A.; Ferard, Y. Combining solar photovoltaic panels and food crops for optimising land use: Towards new agrivoltaic schemes. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Hartung, J.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Högy, P. Agrivoltaic system impacts on microclimate and yield of different crops within an organic crop rotation in a temperate climate. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraunhofer ISE. Agrophotovoltaics: High Harvesting Yield in Hot Summer of 2018. Available online: https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/press-media/press-releases/2019/agrophotovoltaics-hight-harvesting-yield-in-hot-summer-of-2018.html (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Performance Estimation Modeling via Machine Learning of an Agrophotovoltaic System in South Korea. Energies 2021, 14, 6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, H.; Pearce, J.M. The potential of agrivoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cai, J.; Li, H.; Bo, Y.; Liu, F.; Jiang, D.; Dai, T.; Cao, W. Effect of shading from jointing to maturity on high molecular weight glutenin subunit accumulation and glutenin macropolymer concentration in grain of winter wheat. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2012, 198, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.-f.; Li, C.-f.; Dong, S.-t.; Zhang, J.-w. Effects of shading at different stages after anthesis on maize grain weight and quality at cytology level. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M.; Pellet, D.; Monney, C.; Herrera, J.M.; Rougier, M.; Baux, A. Fatty acids composition of oilseed rape genotypes as affected by solar radiation and temperature. Field Crop Res. 2017, 212, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Högy, P. Effects on Crop Development, Yields and Chemical Composition of Celeriac (Apium graveolens L. var. rapaceum) Cultivated Underneath an Agrivoltaic System. Agronomy 2021, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrychowicz-Jastrzębska, G.; Bugała, A. Energetyczna efektywność modułów fotowoltaicznych pracujących w systemach nadążnych. [Energetic effectiveness of photovoltaic modules operating with the follow-up systems]. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2013, 6, 253. Available online: https://archiwum.pe.org.pl/archive.php?lang=0 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Beck, M.; Bopp, G.; Goetzberger, A.; Obergfell, T.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S. Combining PV and food crops to Agrophotovoltaic—Optimization of orientation and harvest. In Proceedings of the 27th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition, Frankfurt, Germany, 24–28 September 2012; Volume 5, pp. 4096–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrou, H.; Wery, J.; Dufour, L.; Dupraz, C. Productivity and radiation use efficiency of lettuces grown in the partial shade of photovoltaic panels. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 44, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praderio, S.; Perego, A. Photovoltaics and the Agricultural Landscape: The Agrovoltaico Concept; REM Tec: Asola, Italy, 2017; Available online: http://www.remtec.energy/en/2017/08/28/photovoltaics-form-landscapes/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Elamri, Y.; Cheviron, B.; Lopez, J.-M.; Dejean, C.; Belaud, G. Water budget and crop modelling for agrivoltaic systems: Application to irrigated lettuces. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 208, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, G.A.; Retamales, J.B.; Hancock, J.F.; Flore, J.A.; Romero-Bravo, S.; del Pozo, A. Productivity and fruit quality of Vaccinium corymbosum cv. Elliott under photo-selective shading nets. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 153, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M.; Gruber, S.; Keinath, T.; Hopf, M. Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition. A Guideline for Germany, 3rd ed.; Fraunhofer ISE: Freiburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanpour Adeh, E.; Selker, J.S.; Higgins, C.W. Remarkable agrivoltaic influence on soil moisture, micrometeorology and water-use efficiency. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrou, H.; Guilioni, L.; Dufour, L.; Dupraz, C.; Wery, J. Microclimate under agrivoltaic systems: Is crop growth rate affected in the partial shade of solar panels? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 177, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, M.; Graß, R.; Wachendorf, M. The effect of shade and shade material on white clover/perennial ryegrass mixtures for temperate agroforestry systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2015, 89, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Murphy, P.; Salazar, A.; Lepley, K.; Rouini, N.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Macknick, J.E. Agrivoltaics as a climate-smart and resilient solution for midday depression in photosynthesis in dryland regions. npj Sustain. Agric. 2025, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutamanee, K.; Onnom, S.; Yingjajaval, S.; Sangchote, S. Leaf photosynthesis and fruit quality of mango growing under field or plastic roof condition. Acta Hortic. 2013, 975, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Deng, W.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Mao, R.; Shao, J.; Fan, J.; Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Protecting grapevines from rainfall in rainy conditions reduces disease severity and enhances profitability. Crop Prot. 2015, 67, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamri, Y.; Cheviron, B.; Mange, A.; Dejean, C.; Liron, F.; Belaud, G. Rain concentration and sheltering effect of solar panels on cultivated plots. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.; Macknick, J.; Lobell, D.; Field, C.; Ganesan, K.; Jain, R.; Elchinger, M.; Stoltenberg, B. Colocation opportunities for large solar infrastructures and agriculture in drylands. Appl. Energy 2016, 165, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panele Fotowoltaiczne SW Premium BIFACIAL (HJT) 300 W, 6 mm. Datas, Catalog Note. Available online: http://sklep.hanplast.energy/panele-fotowoltaiczne/5-sw-premium-bifacial-hjt-300w (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Fraunhofer Chile Research. Agro PV: Concepto de Doble Uso de Suelo con Experiencias Prácticas en Chile; Energy Partnership Chile-Alemania: Santiago, Chile, 2023; Available online: https://energypartnership.cl/fileadmin/chile/highlights/Agro_y_Floating_PV_Oportunidad_para_la_agricultura_y_la_transición/Evento_para_MEN/20230420_Fraunhofer_Chile_Agro_PV_comprimido.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Pandey, G.; Lyden, S.; Franklin, E.; Millar, B.; Harrison, M.T. A systematic review of agrivoltaics: Productivity, profitability, and environmental co-benefits. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 56, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, A.; Li, Z. Application of a Dynamic Semitransparent Agrivoltaic Panel for Controlling Sunlight Allocation to Solar Cells and Crops. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, e00603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X. Agrivoltaics with semitransparent panels can maintain yield and quality in soybean production. Sol. Energy 2024, 282, 112978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Study: Agrivoltaics; Department of Energy: New York, NY, USA, 2022. Available online: https://science.osti.gov/-/media/sbir/pdf/Market-Research/SETO---Agrivoltaics-August-2022-Public.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A. Modified grape composition under climate change conditions requires adaptations in the vineyard. OENO One 2017, 51, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladon, T.; Chandel, J.S.; Sharma, N.C.; Verma, P. Optimizing tree density, canopy training and fertigation for improved productivity and light utilization in apple orchards. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.H.; Imran, H.; Alam, H.; Alam, M.A.; Butt, N.Z. Crop-specific Optimization of Bifacial PV Arrays for Agrivoltaic Food-Energy Production: The Light-Productivity-Factor Approach. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2021, 12, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Gfüllner, L.; Berwind, M. Enhancing agrivoltaic synergies through optimized tracking strategies. J. Photonics Energy 2025, 15, 032703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, E.K.; Gruss, S.M.; Schull, V.Z.; Gosney, M.J.; Mickelbart, M.V.; Brouder, S.; Gitau, M.W.; Bermel, P.; Tuinstra, M.R.; Agrawal, R. Optimized agrivoltaic tracking for nearly-full commodity crop and energy production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Gómez, D. Integration of Crops, Livestock, and Solar Panels: A Review of Agrivoltaic Systems. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynamic Agrivoltaics: Designed for Your Crops, Proven in the Field. Available online: https://sunagri.fr/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Agrivoltaics Can Increase Grape Yield by up to 60%. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2024/11/29/agrivoltaics-can-increase-grape-yield-by-up-to-60/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Okada, Y.; Kotagiri, A.; Sakamoto, T.; Itoh, M.; Misawa, M. Case study of rice farming in Japan under agriphotovoltaic system. J. Photon. Energy 2025, 15, 032704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iowa State University; Alliant Energy. Customer-Hosted Renewables: Alliant Energy Solar Farm at ISU; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://agrivoltaics.research.iastate.edu/files/inline-files/ISU%20Solar%20Fact%20Sheet_1_1.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Iowa State University; Alliant Energy. A Public-Private Partnership to Develop Agrivoltaics in the US Midwest; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://agrivoltaics.research.iastate.edu/files/inline-files/Alliant%20energy%20ISU%20Agrivoltaics%20abstract%20(2024)_1.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Willockx, B.; KU Leuven Research Team. Agrivoltaic Facilities with Single-Axis Trackers Have Lower LCOE than Those with Fixed Structures; PV Magazine International: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2023/09/12/agrivoltaic-facilities-with-single-axis-trackers-have-lower-lcoe-than-those-with-fixed-structures/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kahana, L. Israeli Startup Launches Agrivoltaic Pilot in Desert with Double-Axis Sun Tracking; PV Magazine International: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2024/06/28/israeli-startup-launches-agrivoltaic-pilot-in-desert-with-double-axis-sun-tracking (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Using Agrivoltaics on 1% of EU Farmland Could Lead to 944 GW Installed Capacity, JRC Says. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2023/10/13/using-agrivoltaics-on-1-of-eu-farmland-could-lead-to-944-gw-installed-capacity-jrc-says (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- EU Farming Strategy Recognises the Role of Solar for the First Time. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/press-releases/eu-farming-strategy-recognises-the-role-of-solar-for-the-first-time (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- SPE Urges Brussels to Accelerate Agri-PV Rollout. Available online: https://www.pveurope.eu/agriculture/spe-urges-brussels-accelerate-agri-pv-rollout (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- German Act—Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz vom 21. Juli 2014 (BGBl. I S. 1066), das Zuletzt Durch Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 21. Februar 2025 (BGBl. I Nr. 52) Geändert Worden Ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/eeg_2014/BJNR106610014.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Dual Land Use for Agriculture and Solar Power Production: Overview and Performance of Agrivoltaic Systems 2025. Report IEA-PVPS T13-29:2025. 2025. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IEA-PVPS-T13-29-2025-REPORT-Dual-Land-Use.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- The Regulatory Framework for Agrivoltaics to Preserve French Agriculture. Available online: https://www.tse.energy/en/articles/le-cadre-reglementaire-de-lagrivoltaisme-pour-preserver-lagriculture-francaise (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Italian Council of State Clarifies Rules for Agrivoltaics. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2023/09/05/italian-council-of-state-clarifies-rules-for-agrivoltaics (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Czechia Approves New Laws for Agrivoltaics. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/01/10/czechia-approves-new-laws-for-agrivoltaics (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Czechia Introduces First Rules for Agrivoltaics. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2024/05/10/czechia-introduces-first-rules-for-agrivoltaics (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Croatia Adopts Legal Framework for Agrivoltaics. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2023/07/28/croatia-adopts-legal-framework-for-agrivoltaics (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Regional Study—Podkarpackie/Poland. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/sites/default/files/2025-02/EAGER_Joint%20Study_Annex%206_PL.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- CMS Expert Guide to Agrivoltaics and Floating Photovoltaics in Poland. Available online: https://cms.law/en/int/expert-guides/cms-expert-guide-to-agrivoltaics-and-floating-photovoltaics/poland (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Kruś, M.; Tychmanowicz, K. Agrofotowoltaika jako narzędzie ochrony gruntów rolnych. [Agrophotovoltaics as a Tool for Protecting Agricultural Land]. Samorz. Teryt. 2022, 7-8, 122–130. Available online: http://bazekon.icm.edu.pl/bazekon/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000171651296 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- AgriPV in Poland. Modern Solar-Powered Agriculture. Available online: https://www.cliffordchance.com/content/dam/cliffordchance/briefings/2023/11/agripv-in-poland-9-modern-solar-powered-agriculture.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Agrofotowoltaika Wyklucza Dopłaty do Hektara? MRiRW Wyjaśnia. Available online: https://www.agropolska.pl/zielona-energia/energia-sloneczna/agrofotowoltaika-wyklucza-doplaty-do-hektara-mrirw-wyjasnia%2C174.html (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Report launch: Implementation of Agrivoltaic Projects in Poland. Available online: https://bbs-legal.pl/en/blog/report-launch-implementation-of-agrivoltaic-projects-in-poland,Kancelaria Brysiewicz Bokina i Wspólnicy (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Agrivoltaics: Solar and Agriculture Co-Location. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/solar/agrivoltaics-solar-and-agriculture-co-location (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Owusu-Obeng, P.Y.; Mills, S.B.; Craig, M.T. Implications of Zoning Ordinances for Rural Utility-Scale Solar Deployment and Power System Decarbonization in the Great Lakes Region. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.16626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Releases New Guidelines for Agrivoltaics as Installations Hit 200 MW. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2021/12/13/japan-releases-new-guidelines-for-agrivoltaics-as-installations-hit-200-mw (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Japan Suspends Incentives for 342 Agrivoltaic Facilities. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2024/08/27/japan-suspends-incentives-for-342-agrivoltaic-facilities (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Agrivoltaics Handbook. Available online: https://www.energyco.nsw.gov.au/agrivoltaics-handbook (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Proctor, K.W.; Murthy, G.S.; Higgins, C.W. Agrivoltaics align with green new deal goals while supporting investment in the US’rural economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundational Agrivoltaic Research for Megawatt Scale (FARMS) Funding Program. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/solar/foundational-agrivoltaic-research-megawatt-scale-farms-funding-program (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- S.1778—Agrivoltaics Research and Demonstration Act of 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1778/text (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Fall 2024: Farming the Land, Farming the Sea. Available online: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/environment_energy_resources/resources/natural-resources-environment/2024-fall/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- The Socio-Technical Dynamics of Agrivoltaics in Japan. Volume 2. 2023. Available online: https://www.tib-op.org/ojs/index.php/agripv/article/view/990 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Agrivoltaics in India. Available online: https://beta.cstep.in/staaidev/assets/manual/APV.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Taylor, M.; McDonnell, N.; Davies, P.; Trück, S. Scaling agrivoltaics: Planning, legal, and market pathways to readiness. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 1499–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, D.; Jäger, M.; Strebel, S.; Rohrer, J. Potenzialabschätzungen für Agri-PV in der Schweizer Landwirtschaft; ZHAW Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften, IUNR Institut für Umwelt und Natürliche Ressourcen: Wädenswil, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Agrivoltaics for Arboriculture. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/09/25/agrivoltaics-for-arboriculture/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Clean Energy Canada. 2024 Annual Report. Available online: https://cleanenergycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/CEC-AnnualReport-2024-V4.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- CMS Expert Guide to Agrivoltaics and Floating Photovoltaics in The United Kingdom. Available online: https://cms.law/en/int/expert-guides/cms-expert-guide-to-agrivoltaics-and-floating-photovoltaics/united-kingdom (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- PV Agrivoltaics Could Revitalize Brazilian Crops. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2024/08/24/pv-agrivoltaics-could-revitalize-brazilian-crops/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Solar Panels Plus Farming? Agrivoltaics Explained. Available online: https://undecidedmf.com/solar-panels-plus-farming-agrivoltaics-explained/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Gachoki, P.; Muraya, M.; Njoroge, G. Modelling plant growth based on Gompertz, logistic curve, extreme gradient boosting and light gradient boosting models using high-dimensional image-derived maize (Zea mays L.) phenomic data. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2022, 10, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.T.; Chang, S.J. Exploration of a light shelf system for multi-layered vegetable cultivation. KIEAE J. 2013, 13, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Ji, Y.; Wang, X.; Niu, M.; Long, S.; Xie, J.; Sun, Y. Simplified Method for Predicting Hourly Global Solar Radiation Using Extraterrestrial Radiation and Limited Weather Forecast Parameters. Energies 2023, 16, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mghouchi, Y.; El Bouardi, A.; Choulli, Z.; Ajzoul, T. Models for obtaining the daily direct, diffuse and global solar radiations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crop Modeling Definition, Use Cases and Advantages. Available online: https://www.agmatix.com/blog/the-benefits-of-crop-modeling/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Zhang, N.; Zhou, X.; Kang, M.; Hu, B.-G.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Machine learning versus crop growth models: An ally, not a rival. AoB Plants 2023, 15, plac061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, B.W.; Beyeler, M. Data-driven models in human neuroscience and neuroimaging. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 58, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, K.; Dutta, S.; Das, S.; Sadhukhan, R. Crop simulation models as decision tools to enhance agricultural system productivity and sustainability—A critical review. Technol. Agron. 2025, 5, e002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, P.T.; Satyareddi, S.A.; Manjunath, S.B. Crop Growth Modeling: A Review. Res. Rev. J. Agric. Allied Sci. 2013, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperska-Wołowicz, W.; Łabędzki, L. Porównanie ewapotranspiracji wskaźnikowej według Penmana i Penmana-Monteitha w różnych regionach Polski. Woda-Sr.-Obsz. Wiej. 2004, 4, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiat, I.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ansari, T. A review of evapotranspiration measurement models, techniques and methods for open and closed agricultural field applications. Water 2021, 13, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, A.; Ibrahim, H.; Mahmood, A.; Javaid, M.M.; Wasaya, A.; Nadeem, M.A.; Ismael, M.; Awais, M.; Khan, S.R. Modern agronomic measurement for climate-resilient agriculture. In Climate-Resilient Agriculture; Javaid, M.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonckheere, I.; Fleck, S.; Nackaerts, K.; Muys, B.; Coppin, P.; Weiss, M.; Baret, F. Review of methods for in situ leaf area index determination: Part I. Theories, sensors and hemispherical photography. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 121, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubushar, M.; El-Hendawy, S.; Dewir, Y.H.; Al-Suhaibani, N. Ability of different growth indicators to detect salt tolerance of advanced spring wheat lines grown in real field conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, B.B.; Williams, M.R.; He, T. Relative growth rate (RGR) and other confounded variables: Mathematical problems and biological solutions. Ann Bot. 2023, 131, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudriaan, J.; Monteith, J.L. A Mathematical Function for Crop Growth Based on Light Interception and Leaf Area Expansion. Ann. Bot. 1990, 66, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacasa, J.; Hefley, T.J.; Otegui, M.E.; Ciampitti, I.A. A practical guide to estimating the light extinction coefficient with nonlinear models—A case study on maize. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.L.; Scott, R.K. Crop growth and soil water management. In Advances in Irrigation; Hillel, D., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; Volume 1, pp. 33–85. ISBN 0-12-0243301-6. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Struik, P.C. Crop systems biology: Narrowing the gaps between crop modelling and genetics. Front Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ma, Y.T.; Dingkuhn, M.; Luquet, D.; Song, X.; Yin, X. GreenLab model for simulating rice growth: An evaluation using experimental data. Field Crops Res. 2016, 99, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Guo, Y.; Struik, P.C. Modelling the crop: From system dynamics to functional–structural plant models. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Goudriaan, J.; Challa, H. Using the expolinear growth equation for modelling crop growth in year-round cut chrysanthemum. Ann. Bot. 2023, 92, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tei, F.; Scaife, A.; Aikman, D.P. Growth of lettuce, onion, and red beet. 1. Growth analysis, light interception, and radiation use efficiency. Ann. Bot. 1996, 78, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Hu, W.; Li, Y. Growth and Leaf Development of Pak-Choi (Brassica rapa var. chinensis) under Semi-Closed Greenhouse Conditions. Horticulturae 2020, 8, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, J.R. On Exponential growth and mathematical purity: A reply to bartlett. Popul. Environ. 2003, 25, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimpf, D.J.; Flint, S.D.; Palmblad, I.G. Representation of Germination Curves with the Logistic Function. Ann. Bot. 1977, 41, 1357–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.H.; Nelson, C.J.; Chow, W.S. A Mathematical Model to Utilize the Logistic Function in Germination and Seedling Growth. J. Exp. Bot. 1984, 35, 1629–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Frutos, G. Logistic Function Analysis of Germination Behaviour of Aged Seeds. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1990, 30, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompertz, B. On the Nature of the Function Expressive of the Law of Human Mortality, and on a New Mode of Determining the Value of Life Contingencies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1825, 115, 513–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwietering, M.H.; Jongenburger, I.; Rombouts, F.M.; van ‘t Riet, K. Modeling of the Bacterial Growth Curve. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjørve, K.M.C.; Tjørve, E. The Use of Gompertz Models in Growth Analyses, and New Insights from Recent Re-Parameterisations. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APS. The American Phytopathological Society. Available online: https://www.apsnet.org (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Passão, C.; Almeida-Aguiar, C.; Cunha, A. Modelling the In Vitro Growth of Phytopathogenic Filamentous Fungi and Oomycetes: The Gompertz Parameters as Robust Indicators of Propolis Antifungal Action. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahakosee, S.; Jogloy, S.; Vorasoot, N.; Theerakulpisut, P.; Toomsan, B.; Holbrook, C.C.; Kvien, C.K.; Banterng, P. Light Interception and Radiation Use Efficiency of Three Cassava Genotypes with Different Plant Types and Seasonal Variations. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, F.W.T.P.; Jansen, D.M.; Berge, H.F.M.T.; Bakema, A. Simulation of Ecophysiological Processes of Growth in Several Annual Crops; International Rice Research Institute: Los Baños, Philippines, 1989; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Li, D.Q.; Cao, Z.J.; Gong, W.; Juang, C.H. Reliability-based robust geotechnical design using Monte Carlo simulation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2017, 76, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.L. Climate and the efficiency of crop production in Britain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1977, 281, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwamba, S.; Kaluba, P.; Moualeu-Ngangue, D.; Winter, E.; Chiona, M.; Chishala, B.H.; Munyinda, K.; Stützel, H. Physiological and Morphological Responses of Cassava Genotypes to Fertilization Regimes in Chromi-Haplic Acrisols Soils. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, J.C.; Ganjegunte, G.K.; Jeong, J.; Rajan, N.; Zapata, S.D.; Ruiz-Alvarez, O.; Enciso, J. Radiation use efficiency and agronomic performance of biomass sorghum under different sowing dates. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L. Simulation Modeling in Botanical Epidemiology and Crop Loss Analysis. Plant Health Instr. 2014, 173. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Simulation+modeling+in+botanical+epidemiology+and+crop+loss+analysis&author=Savary,+S.&author=Willocquet,+L.&publication_year=2014&journal=Plant+Health+Instr.&pages=147 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- De Wit, A.; Boogaard, H.; Fumagalli, D.; Janssen, S.; Knapen, R.; van Kraalingen, D.; Supit, I.; van der Wijngaart, R.; van Diepen, K. 25 years of the WOFOST cropping systems model. Agric. Syst. 2019, 168, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willocquet, L.; Bregaglio, S.; Ferrise, R.; Kim, K.H.; Savary, S. DYNAMO-A: A generic simulation model coupling crop growth and disease epidemic. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrou, H.; Dufour, L.; Wery, J. How does a shelter of solar panels influence water flows in a soil–crop system? Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 50, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruppuarachchi, D.S.P. Intercropped potato (Solanum spp.): Effect of shade on growth and tuber yield in the northwestern regosol belt of Sri Lanka. Field Crop Res. 1990, 25, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midmore, D.J.; Berrios, D.; Roca, J. Potato, (Solanum spp.) in the hot tropics V. intercropping with maize and the influence of shade on tuber yields. Field Crop Res. 1988, 18, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.J.; Singletary, G.; Schussler, J.; Williamson, D.R.; Christy, A.L. Shading effects on dry matter and nitrogen partitioning, kernel number, and yield of maize. Crop Sci. 1988, 28, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Simonneau, T.; Sourd, F.; Pechier, P.; Hamard, P.; Frisson, T.; Ryckewaert, M.; Christophe, A. Increasing the total productivity of a land by combining mobile photovoltaic panels and food crops. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Muchow, R.C. Radiation-use efficiency. Adv. Agron. 1999, 65, 215–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, B.; Kim, H.S.; Jeon, J.; Yi, M.J. Effects of Temporal and Interspecific Variation of Specific Leaf Area on Leaf Area Index Estimation of Temperate Broadleaved Forests in Korea. Forests 2016, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Fan, W.; Wu, J.; Zheng, M.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Chigaba, S. Feasibility in Estimating the Dry Leaf Mass and Specific Leaf Area of 50 Bamboo Species Based on Nondestructive Measurements. Forests 2016, 12, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, A.C.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Carbon storage in plants: A buffer for temporal light and temperature fluctuations. Silico Plants 2023, 5, diac020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.J.; Fereres, E. A dynamic model of crop growth and partitioning of biomass. Field Crops Res. 1999, 63, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleemola, J.; Teittinen, M.; Karvonen, T. Modelling crop growth and biomass partitioning to shoots and roots in relation to nitrogen and water availability, using a maximization principle: I. Model description and validation. Plant Soil 1996, 185, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, S.; Maupas, F.; Cournède, P.H.; De Reffye, P. A morphogenetic crop model for sugar-beet (Beta vulgaris L.). In Crop Modeling and Decision Support; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Nandeshwar, S.B. Genetically modified crops. In Plant Biology and Biotechnology: Volume II: Plant Genomics and Biotechnology; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 527–550. [Google Scholar]

- Willocquet, L.; Aubertot, J.N.; Lebard, S.; Robert, C.; Lannou, C.; Savary, S. Simulating multiple pest damage in varying winter wheat production situations. Field Crops Res. 2008, 107, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duinkerken, G.; Blok, M.C.; Bannink, A.; Cone, J.W.; Dijkstra, J.; Van Vuuren, A.M.; Tamminga, S. Update of the Dutch protein evaluation system for ruminants: The DVE/OEB2010 system. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Y.; Ikeuchi, M.; Jiao, Y.; Prasad, K.; Su, Y.H.; Xiao, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Plant regeneration in the new era: From molecular mechanisms to biotechnology applications. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 1338–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalgynbayeva, A.; Mizik, T.; Bai, A. Cost–Benefit Analysis of Kaposvár Solar Photovoltaic Park Considering Agrivoltaic Systems. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Santos, L.; Garcia, G.P.; Estanqueiro, A.; Justino, P.A. The Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) of wave energy using GIS based analysis: The case study of Portugal. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2015, 65, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M. An Economic Analysis of Agrophotovoltaics: Opportunities, Risks and Strategies Towards a More Efficient Land Use; No. 03-2016; The Constitutional Economics Network Working Papers; University of Freiburg, Institute for Economic Research, Department of Economic Policy and Constitutional Economic Theory: Freiburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, J. Wybrane Ekonomiczne i Prawne Aspekty Wytwarzania Energii z Instalacji Fotowoltaicznych [Selected Economic and Legal Aspects of Energy Generation from Photovoltaic Installations], Instytut Ekonomii i Finansów SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. Available online: https://www.ieif.sggw.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Wybrane-ekonomiczne-i-prawne-aspekty_fotowoltaiczne_MajewskiJ-wersja-el-1.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Møller, I.M.; Murphy, A. Plant Physiology and Development, 6th ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, UK, 2015; pp. 687–710. [Google Scholar]

- Agrivoltaics Market Size & Share Analysis—Growth Trends and Forecast (2025–2030); Mordor Intelligence: Telangana, India, 2024. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/agrivoltaics-market?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Pekk, L.; Varbanov, P.S.; Pan, T.; Weltsch, Z.; Radli-Burjan, B.; Hary, A.; Wang, X.C. Future of Agrivoltaic projects: A review from the technological forecasting perspective. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 28, 101057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Qi, Y.; Fu, W.; Kumar Soothar, M. Current Status and Future Trends in China’s Photovoltaic Agriculture Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivation/Application | Best Module Type | Transparency/Feature | Structure Height (min) | Spacing/Comments | Expected Impact on Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lettuce, arugula, spinach, leafy vegetables | Spaced-cell or semi-transparent, glass-glass | 20–40% light transmittance | 2.0–2.5 m (possibly lower) | Rows every 3–6 m, even light distribution | No decline, often improvement in quality |

| Berries (strawberries, blueberries, raspberries) | Semi-transparent (spaced-cell), glass-glass, bifacial | 15–35%, moisture resistant | 2.5–4.0 m (machines can be used) | Rows with passageway, protective cover systems | Yield stabilization, quality improvement in drought conditions |

| Grapevine | Glass-glass, bifacial | Acceptable low transparency, possibility of using full modules between rows of plants | 3.5–5.0 m | Row planting, orientation consistent with the vineyard | Usually no decline, better drought resistance |

| Herbs | Semi-transparent (spaced-cell), thin-film | 20–40% | 2.0–3.0 m | Denser planting under panels, light control | No decrease |

| Potatoes and root vegetables | Semi-transparent (spaced-cell), bifaccial above rows | 15–30% | 2.5–3.5 m | Larger gaps between panels to avoid restricting photosynthesis | Typically, no significant losses, improved water efficiency |

| Fruit trees, orchards | On tall racks, bifaccial, semi-transparent | 10–30% permeability | 4.0–5.5 m (depending on tree species) | Long journeys, individual projects | Potential benefits in hot climates, risks in cooler climates |

| Pastures | Bifacial, glass-glass | Lack of required transparency, additional benefit from reflection | 3.0–4.5 m | Large crossings, durable structures | No decrease |

| Light-loving crops (corn, sunflower) | Arrangement of panels between rows (classic modules with large gaps between rows) | Lack of required transparency, use only between rows of crops | 3.0–5.0 (depending on the system) | Large spacing to minimize plant shading | Risk of reduced yield if the panels are located above the plants and shade them |

| Indicator/Technical Parameter | Impact on Energy | Impact on Crops | Key Trade-Off/ Quantitative Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of crop shading | Loss of energy gained (dependent on Rshade). | Crop losses tolerated up to 25%. | A maximum reduction in available radiation of approx. 30% (in Central Europe) may be justified if crop losses are acceptable. |

| Tracking systems | Increase in energy production by 25–30% compared to fixed systems. | Enables dynamic shade control (e.g., CT-AT) to protect crops during critical growth periods. | Higher investment and maintenance (O&M) costs compared to fixed structures. |

| Height of the PV installation | Increase in investment and maintenance (O&M) costs. | Minimum 2.1 m required for safe machine operation. For grapevines: 2–3 m. For trees: 4.0–5.5 m. | Balancing construction costs with the possibility of using large agricultural machinery. |

| Bifacial PV modules | Additional energy generation of up to 25% from reflected radiation. | Better use of reflected/diffused light, especially with larger row spacing. | Higher costs of modules compared to standard ones. |

| Water conservation | No direct impact on PV production. | Reduction of water evaporation from soil by 14–29% (in dry conditions, e.g., California). | An agronomic benefit that minimizes drought risk and stabilizes crops. |

| Land Equivalence Ratio (LER) | LER for energy (Yeildy(dual)/Yeildy(mono)). | LER for crops (Yieldy(dual)/Yieldy(mono)). | APV is more effective than monoculture/mono-PV when LER > 1. |

| Minimum required crop | Indirect impact (affects agricultural profitability). | It must achieve at least two-thirds (66%) of the reference yield (DIN SPEC 91434, Germany) or 80% (Japan). | Legal/certification requirement for maintaining the agricultural function of land. |

| LCOE (APV vs. ground-mounted PV) | Profitability indicator: APV is more profitable than small rooftop systems. | The profit from organic farming can make the system profitable despite lower crops. | Depends on scale, location and subsidies. |

| Country | Legal Status (2025) | Key Regulations/Guidelines | Public Support System | Key Barriers/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | No uniform federal law; state regulations | • Agrivoltaics Research & Demonstration Act (2023)—research and pilot projects • DOE guidelines (FARMS Programme) | • DOE research grants • Locally—tax breaks, state grants (e.g., Massachusetts SMART Programme) | • Inconsistent state and local regulations • Complex zoning procedures • Lack of dual-use land classification |

| Japan | Regulated and actively developed | • MAFF (Ministry of Agriculture) guidelines from 2021 • Requirement to maintain agricultural function and production | • FIT tariffs for PV (subject to compliance with agriculture) • Local programmes for rural areas | • Strict conditions regarding land use • Penalties for violations—loss of FIT support • Difficulties in monitoring crops under panels |

| China | Formal recognition of agrivoltaics as a form of renewable energy | • Renewable Energy Act (amendments 2020–2023) • “PV + Agriculture” guidelines as part of the five-year programme | • State subsidies for PV on agricultural land • Preferential loans | • Uneven level of local implementation • Concerns about project greenwashing • Need for control of compliance with agricultural use |

| India | Partially regulated at state level | • PM-KUSUM programme (2019–)—promotes PV in agriculture, including agrivoltaics • Local state regulations (e.g., Gujarat, Rajasthan) | • Subsidies of up to 60% of investment costs • Guaranteed energy off-take | • No uniform national law • Problems with grid connections • Financial difficulties of small farmers |

| Australia | In the development phase; no specific regulations | • Agrivoltaics Handbook [119] • General planning law | • Regional programmes (e.g., Clean Energy Finance Corporation) • Research grants | • No legal definition of agrivoltaics • Land use conflicts • State-dependent planning procedures |

| Switzerland | Framework being developed; pilot and test projects | • SFOE and FOAG (Federal Offices) guidelines—2024 • Cantonal regulations on land protection | • Investment support from federal programmes • Research grants | • Complex land regulations • Lack of systemic recognition of agrivoltaics in agricultural subsidies |

| Canada | In the pilot phase, no national regulations | • Recommendations from Natural Resources Canada [129] • Provincial programmes: Alberta, Ontario | • Grants and tax credits under the Clean Energy Investment Tax Credit | • Provincial regulations are inconsistent • No formal definition of agrivoltaics |

| UK | Implementation underway; in consultation phase | • DEFRA & BEIS—2024 consultations: Solar & Farming Integration Policy | • Support for PV under Contracts for Difference (CfD) • R&D grants | • No agrivoltaics status in spatial planning • Uncertainty in access to agricultural subsidies |

| Brazil | Dynamic development, legislation in preparation | • Draft law on agrivoltaics (2024) • ANEEL and EMBRAPA guidelines | • Loans and grants for farmers from Banco do Brasil • Energia Renovável no Campo programme | • Lack of uniform land classification rules • Grid and financial barriers |

| Republic of Korea | Strong government support, operational framework | • MAFRA and KEA (Korea Energy Agency) guidelines • Panel area limits (≤30% ground coverage) | • Subsidies, FIT, and low-interest loans | • High certification costs • Need for periodic yield verification |

| Quantitative/Regulatory Indicator | Critical Value/Limit | Context (Standard/Country) | Significance for the APV Project |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum required crop | ≥66% of the reference crop | Germany (DIN SPEC 91434:2021-05) | Certification requirement: Essential for maintaining the original agricultural function; below this value, the system may not be classified as APV. |

| ≥80% of the reference crop | Japan | Condition for maintaining support: Failure to meet this condition (annual reporting requirement) entails a high investment risk (necessity to remove the installation) or loss of FIT subsidies. | |

| Maximum panel coverage area | ≤10% (category 1—on poles) | Germany (DIN SPEC 91434:2021-05) | It limits the loss of agricultural land designated for support structures, which is crucial for maintaining the status of agricultural land. |

| ≤15% (category 2—terrestrial) | Germany (DIN SPEC 91434:2021-05) | Alternative coverage limit for another type of installation. | |

| 40% of the land area | France | It sets strict building limits in order to protect agronomic potential. | |

| Minimum distance between rows | ≥6 m (for vertical systems) | Czech Republic | Required to maintain agricultural land status, ensuring the possibility of cultivation and passage of machinery (in vertical systems). |

| Minimum installation height | ≥2.1 m (for horizontal systems) | Czech Republic | Required to maintain agricultural land status and ensure access for agricultural machinery. |

| ≤9 m | Japan | Construction restrictions for APV installations (excluding tracking systems and greenhouses). | |

| Required LER index | LER > 1 | General economic criterion | Total land use efficiency assessment indicator; APV profitability condition. |

| Increase in the economic value of the farm | Up to 30% | Economic research (USA) | Potential income increase as a result of diversification (energy + crops). |

| Model | Measured Quantitative Parameter | Function in APV Optimization | Key Required Inputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation Distribution Model | Shading coefficient (Rshade), Incident radiation (I(1 − Rshade)), Light intensity (PAR). | It enables quantitative assessment of the impact of APV geometry (height, spacing) on the light balance of plants. It serves as a basis for LUE calculations and yield forecasting. | Distribution of solar radiation (I0), Atmospheric transparency (KT), Geometric parameters of PV installations. |

| Biomass Growth Models (Exp-Linear, Logistic, Gompertz) | Relative Growth Rate (RGR), Crop Growth Rate (CGR), Leaf Area Index (LAI), Maximum Biomass (Cm, a1). | Forecasting final yield and biomass depending on available PAR. Helps determine maximum planting density and minimum panel height. | LAI, LUE (light use efficiency), Cumulative PAR, Time (t) or time lost (tb). |

| GENECROP model | Radiation Use Efficiency (RUE), Degree of Vegetative Development (DVS), Assimilation Allocation (PARTL, PARTSO). | It enables simulation in terms of time, at which stage of development (DVS) shading has the greatest negative impact on the final yield. It combines climatic parameters (temperature) with plant physiology. | Temperature, extinction coefficient (k), RUE, daily solar radiation (RAD). |

| LCOE (Levelised Cost of Electricity) | Standardized energy cost. | Quantifies the profitability of APV. Allows comparison of APV with conventional ground-mounted and rooftop PV systems. | Investment costs (It), Operating costs (Kt), Annual energy production (St). |

| LER (Land Equivalence Ratio) | Land use efficiency. | Land efficiency ratio. Values of LER > 1 indicate that dual use is more efficient than the sum of production on separate plots. | Agricultural yield in APV vs. monoculture, Energy yield in APV vs. mono-PV. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bugała, D.; Bugała, A.; Trzmiel, G.; Tomczewski, A.; Kasprzyk, L.; Jajczyk, J.; Kurz, D.; Głuchy, D.; Chamier-Gliszczynski, N.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A.; et al. Application of Agrivoltaic Technology for the Synergistic Integration of Agricultural Production and Electricity Generation. Energies 2026, 19, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010102

Bugała D, Bugała A, Trzmiel G, Tomczewski A, Kasprzyk L, Jajczyk J, Kurz D, Głuchy D, Chamier-Gliszczynski N, Kurdyś-Kujawska A, et al. Application of Agrivoltaic Technology for the Synergistic Integration of Agricultural Production and Electricity Generation. Energies. 2026; 19(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleBugała, Dorota, Artur Bugała, Grzegorz Trzmiel, Andrzej Tomczewski, Leszek Kasprzyk, Jarosław Jajczyk, Dariusz Kurz, Damian Głuchy, Norbert Chamier-Gliszczynski, Agnieszka Kurdyś-Kujawska, and et al. 2026. "Application of Agrivoltaic Technology for the Synergistic Integration of Agricultural Production and Electricity Generation" Energies 19, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010102

APA StyleBugała, D., Bugała, A., Trzmiel, G., Tomczewski, A., Kasprzyk, L., Jajczyk, J., Kurz, D., Głuchy, D., Chamier-Gliszczynski, N., Kurdyś-Kujawska, A., & Woźniak, W. (2026). Application of Agrivoltaic Technology for the Synergistic Integration of Agricultural Production and Electricity Generation. Energies, 19(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010102