1. Introduction

The Polish economy has been developing in a market fashion since 1989. Since then, the industry of companies involved in the generation, storage, distribution, transmission and trading of electricity has undergone a huge transformation from a monopolistic system to a free market system [

1,

2]. It should be noted, however, that in accordance with the provisions of the current regulations, this activity is regulated and carried out under the strict control and supervision of state authorities, including the Energy Regulatory Office. In 1997, the Energy Law Act was passed, which regulated, inter alia, the rules for conducting business activity in this area and introduced many obligations and tasks for energy companies. These tasks and obligations are aimed at ensuring energy security, economical and rational use of fuels and energy, development of competition, counteracting the negative effects of natural monopolies, taking into account environmental protection requirements, obligations under international agreements, and balancing the interests of energy companies and consumers of fuels and energy (Article 1 of the Energy Law).

However, it should be remembered that companies from the energy sector, apart from clear differences in the rules for taking up and conducting business activity, have their own goals and operate on the market, which means that they are subject to the same rules as other entrepreneurs in terms of making transactions and settling them, with some additional and specific solutions present for this industry [

3,

4,

5,

6].

As indicated, problems with delayed or missing payments affect every entrepreneur. However, due to the special status of energy companies and their role in ensuring the stability of energy supplies for production, services or consumers, it seems necessary to develop methods and learn about the instruments that will provide energy companies with security in terms of settling their receivables.

In the literature under study, there are few publications strictly related to problems with transaction risk in companies selling energy. The subject of transaction risk is mainly taken up in the legal and financial literature, but this applies to entrepreneurs in general, without taking into account the specific role and legal situation of energy companies. Work on the risk of delayed payments also concerns mainly small and medium-sized enterprises and the impact of delays on their financial situation [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. There are relatively few works in the literature referring to large enterprises producing electricity.

The article presents the legal basis for the functioning of enterprises—electricity producers in Poland–in order to demonstrate their special legal status and role in ensuring energy supply. It was indicated how many such enterprises in Poland actually operate, which illustrates the scale of possible effects on the economy in the event of their financial problems. The impact of delayed payments on the profitability of enterprises is described. Instruments minimizing delays in payments and protecting against non-payment have been identified and described.

The article deals with an important topic regarding the delay or non-payment of energy companies for the energy or services provided. The problem is significant, because any delay or non-payment reduces the profitability of such entrepreneurs. An analysis of the literature has shown that there are few works focusing on this problem, which has both economic and legal foundations. It is necessary to present the instruments that are available to companies in the energy industry to minimize this risk.

2. Legal Status and Goals of Energy Companies

In Poland, energy companies operate on the basis of the provisions of the Energy Law and other acts that apply to all entrepreneurs. The basis for undertaking activities in the field of generation, transmission, trading, and distribution of energy is the possession of a concession by a given entity, i.e., a special administrative decision on the basis of which the company that obtained it may conduct the activity covered by the concession [

12,

13,

14]. This means that the state regulates access to this activity and it can only be undertaken by companies that meet the requirements set out in the Energy Law [

12,

13,

14].

A licence can only be obtained by an entrepreneur who has its registered office or place of residence in the territory of a Member State of the European Union, the Swiss Confederation, or an EFTA Member State and has financial resources in an amount that guarantees the proper performance of the activity or is able to document the possibility of obtaining them; has the technical capabilities to guarantee the proper performance of the activity; will ensure the employment of people with appropriate professional qualifications; and is not in arrears with the payment of taxes [Article 33 of the Energy Law]. The concession is granted by the Energy Regulatory Office for a period of 10–50 years.

Currently, 1864 entities in Poland have a license for activities related to the energy market.

Table 1 presents licensed entities and defines the scope of this activity.

The list presented in

Table 1 shows that the largest number of concessions were granted in the field of electricity generation, and the least in the field of its transmission. This is due to the fact that in Poland, the only entity authorized to dispose of the networks is Polskie Sieci Elektroenergetyczne S.A. [

12,

13,

14].

Energy companies are required to maintain the ability of equipment, installations, and networks to provide energy supply continuously and reliably, while maintaining the applicable quality requirements. On the other hand, companies involved in the transmission or distribution of energy are obliged to provide all customers and companies involved in the sale of energy, on the basis of equal treatment, with the provision of energy transmission or distribution services, on the terms and to the extent specified in the Act, and the provision of transmission or distribution services of these fuels or energy takes place on the basis of a contract for the provision of these services. Such regulations restrict the freedom of economic activity, but their purpose is to make full use of the network’s capacity and guarantee the stability of energy supply.

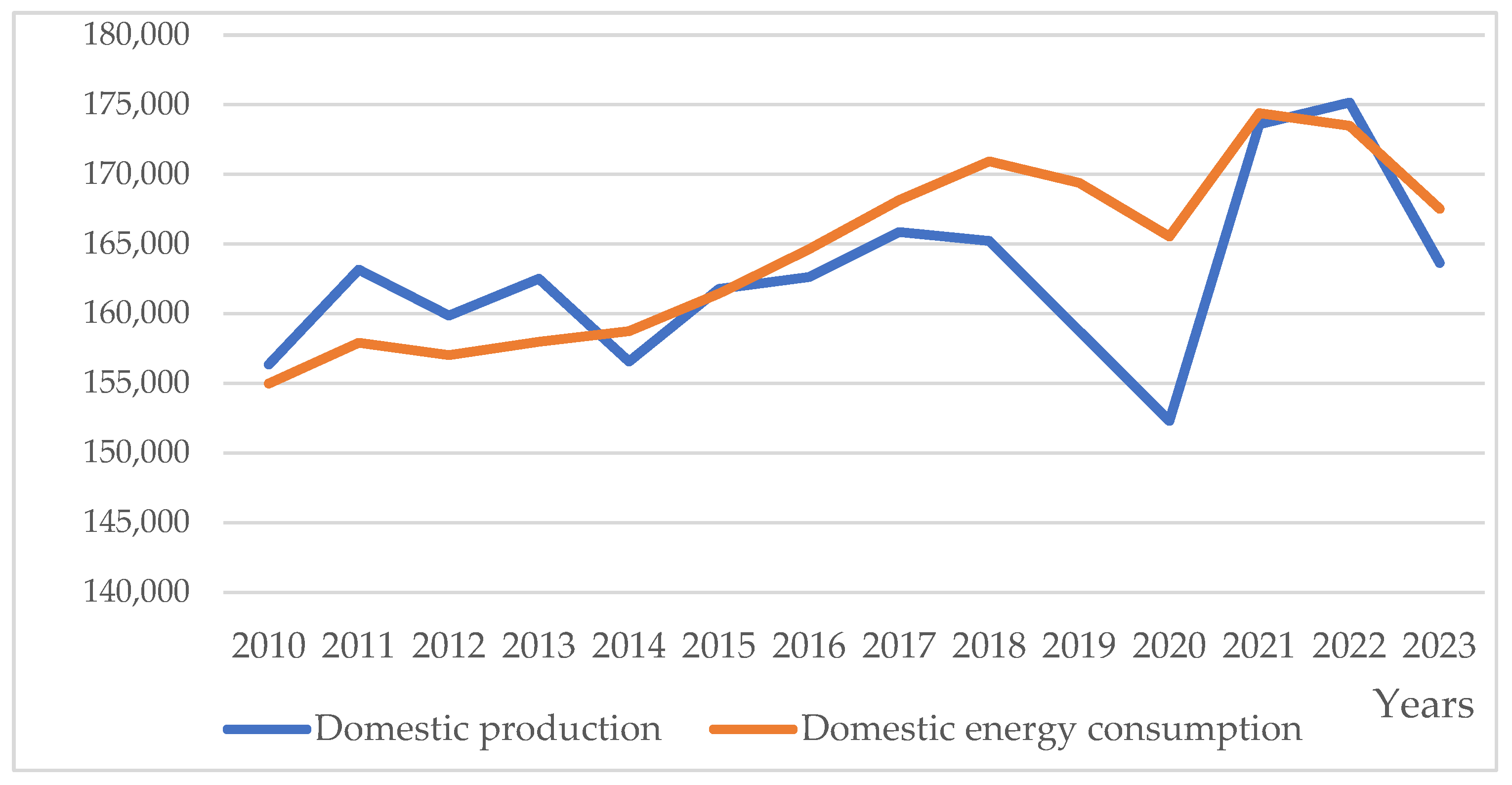

The energy business is constantly evolving. In principle, there is a constant increase in energy generation and consumption.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 present data on energy generation and consumption in Poland in the years 2010–2023.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show that both production and energy consumption in Poland are constantly increasing. However, there are changes in the use of energy sources. A steady increase in energy from wind farms and other renewable sources is noted. This is related to the postulates of decarbonization of energy sources and emerging instruments for financing investments in renewable energy sources. It should be noted that the increase in energy production is associated with an increase in its sales and a possible risk of delay or non-payment.

As previously indicated, the legal regulations concerning energy companies in Poland focus on the obligations and rights of these entities in the mainly administrative and legal scope (the need to have a license, the obligation to set tariffs, the consent of the Energy Regulatory Office and others). However, it should not be forgotten that these companies conduct business activity and operate on the market on the same terms as other entrepreneurs. This means that in order to sell energy, they conclude contracts, set payment deadlines, are themselves debtors for their own liabilities, wait for payment, or pursue their claims before the courts. Therefore, it can be considered that they pursue their goals based on the general principles of economic thought, i.e., [

4,

5,

6,

8,

15,

16]:

- -

profit maximization,

- -

maximizing market share (this goal is closely correlated with profit maximization and is therefore sometimes used alternatively),

- -

survival,

- -

safety,

- -

achieving “satisfactory profit”—the shortcomings and limitations of the decision-making process imply the choice of variants that give “satisfactory profit”,

- -

maximizing accumulation on sales,

- -

maximizing the profit/risk ratio,

- -

increase in value.

The two most important goals of commercially operating companies are profitability (i.e., maximizing profit or market share) and risk (i.e., “safety” or “survival”). It follows that the most difficult decisions in a company are related to the choice between the expected profit and risk [

10,

16,

17]. The task of decision-makers about the future in the company will be to choose an option that minimizes risk with given profits or maximizes profits with a given risk. In both cases, the goal is the same: to maximize the value of the company. The achievement of these goals is possible only if the counterparty pays its obligations [

11,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

The value of an enterprise depends on the value of real cash flows related to its activities [

4]. The condition for achieving an increase in the value of the enterprise is an increase in its financial flows or a decrease in the discount rate. These two factors are generally exposed to volatility resulting from economic uncertainty and, consequently, risk. The likelihood of a company being exposed to financial distress and the resulting costs can be reduced through risk management.

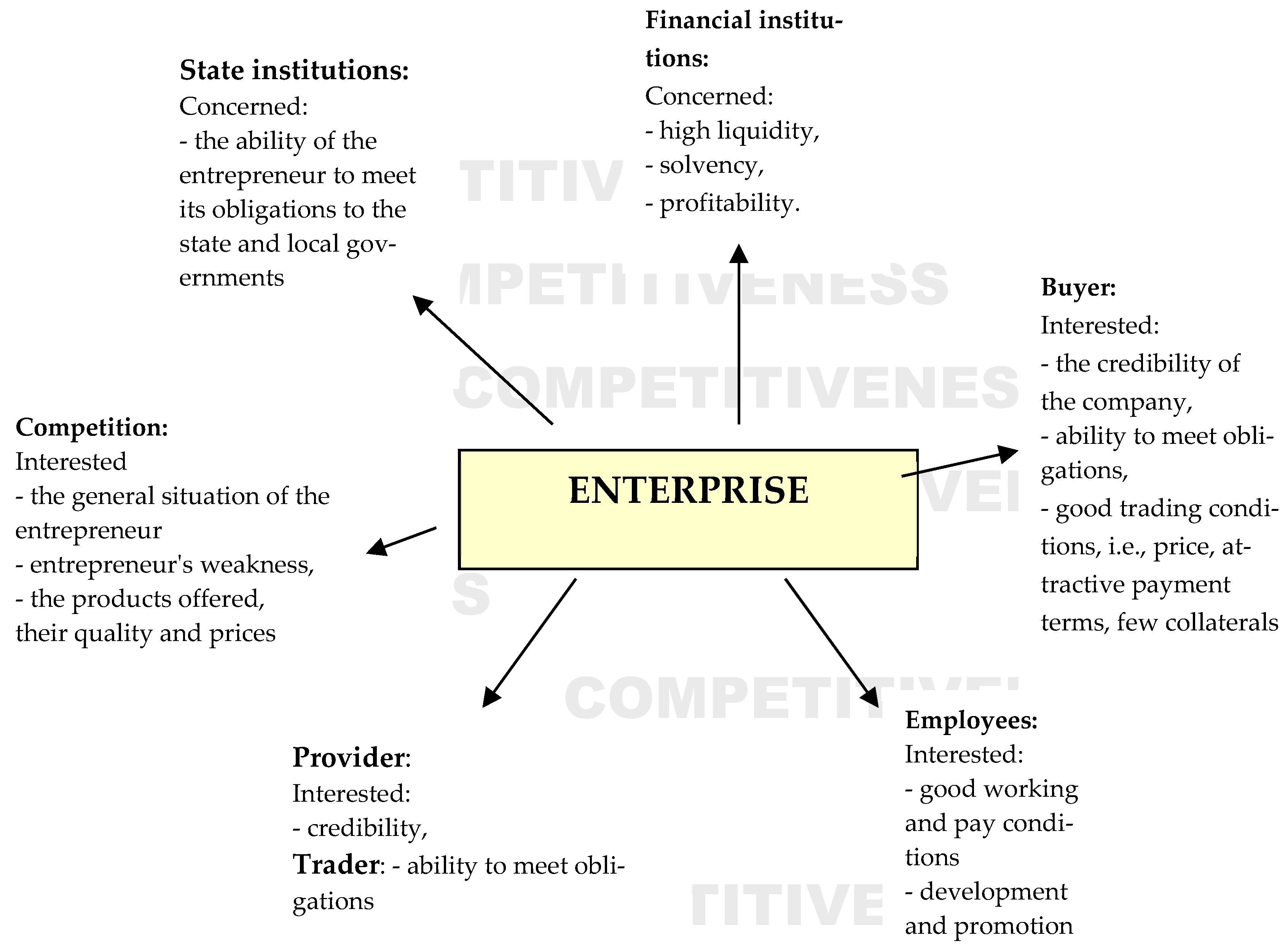

The second important factor determining the value of an entity is its competitiveness, understood as a process by which an entrepreneur, striving to pursue its interests, tries to present offers that are more advantageous than others in terms of price, terms, and conditions of payment, quality, or other features influencing the decision to conclude a transaction [

23,

24,

25]. The concept of competitiveness can be understood differently by individual entities cooperating with a given entrepreneur.

Figure 3 presents the perception of the competitiveness of the company by entities establishing business contacts with it.

An entrepreneur from the energy industry cooperates in his environment with many groups of entities (buyers, suppliers, financial institutions, state institutions, competitors, employees), which assess his competitiveness in various ways [

14,

26,

27]. Each of these entities perceives its economic interest in cooperation with the company. Therefore, everyone will also have different requirements in terms of competitiveness. For example, buyers will be interested in the best possible sales conditions. Assuming the same quality of products [

25], they will choose the offer of the company that offers the most favourable terms of the transaction, e.g., the longest possible payment term and the cheapest and least formalized security. On the other hand, the supplier will perceive the company as competitive if it ensures the security of cooperation, i.e., guarantees payment and secures it. The guarantee of proper performance of the contract will be provided by the company that best secures its contracts. It should be noted that in the energy industry, companies in Poland always have to consider whether the customer is a consumer or whether the contractor purchases energy as part of their business activity [

28].

In the above context, the risk mitigation methods requested by the energy seller may provide an incentive to purchase the service or, on the contrary, discourage the customer with the procedure for establishing collateral or economic requirements. Undoubtedly, however, every entrepreneur offering his products or services should carefully select contractors to whom he offers any trade credit [

29,

30]. An extended payment term requires the seller/service provider to finance such a loan and involves the risk of non-payment [

31,

32,

33,

34].

3. The Methodology

The aim of the article is to examine whether there are problems with receivables in companies selling electricity in Poland and to identify and evaluate instruments for mitigating the risk of late payments in the activities of energy companies.

In order to achieve the indicated goal, the following hypotheses were formulated:

- (1)

The problem of abandoned payments or lack of them occurs in energy companies in Poland.

- (2)

Energy companies have average longer payment terms than the average ascending terms in the economy.

- (3)

Late payments have a significant impact on the profitability of companies.

- (4)

Due to the fact that receivables are overdue and the receivables from counterparties are high in total assets, it is necessary to use tools to hedge the risk of non-payment.

The subject of the research are companies producing electricity in Poland. Due to the limitations in obtaining data on the management of receivables of energy companies, the research was limited to the five largest companies selling energy in Poland, i.e., Energa Obrót S.A., PGE Obrót S.A., Enea S.A., TAURON S.A., E.ON Polska S.A. The availability of data allowed us to focus more on Energa S.A.

The subject of research is the problem of late payment or non-payment for services or energy provided.

In this article, as part of the research methodology, a process consisting of a critical analysis of Polish and international literature in the field of finance, management, risk mitigation, and law was carried out. Statistical data on the activity of energy companies, energy production, payment deadlines, and delays in payment were used. A phenomenological analysis of the available data and instruments for reducing the risk of payments in the literature and business practice was also conducted.

In addition, comparative analysis was used and the basics of statistical and financial analysis were used. The research focused on the data of the Central Statistical Office of Poland as well as financial statements and reports on the activities of the surveyed entities.

4. Transactional Risk in Operations in Polish Companies

Transactional risk means that the counterparty may default on the contract for various reasons [

8,

22,

34,

35,

36]. Therefore, the contractor may commit in particular: delay in payment, fail to pay for the goods at all, or fail to undertake the transaction. Each of these actions or omissions has negative consequences for the seller/service provider. The subject of interest of this article is the risk related to delays in payments and the risk of non-payment for the energy supplied.

4.1. Deadlines for Settling Liabilities in Poland and Europe

Every entrepreneur operating in the energy industry should remember that there is no standard customer. The financial strength of each contractor is as unique as fingerprints. The seller’s portfolio of contractors consists of large, medium, and small entities, with liabilities ranging from small to huge sums. Some of the companies are developing, and others are going downhill. An individual approach to each contractor is necessary. Competitiveness requires flexibility and attractive sales conditions from companies selling their services. Therefore, trade credit is commonly granted. Unfortunately, statistical data show that payment terms are extended, and contractors delay payment [

37,

38,

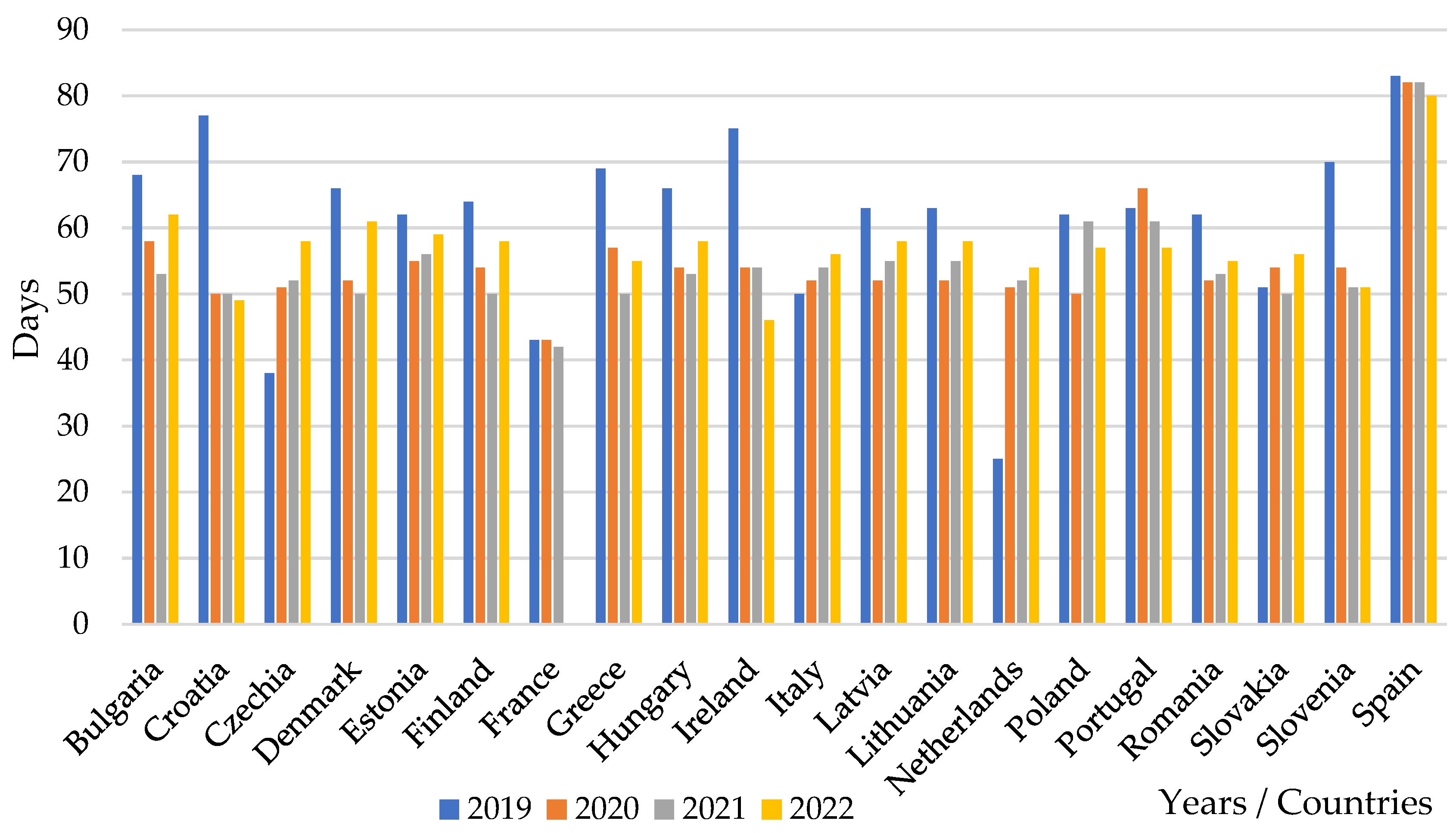

39]. Average payment terms in selected countries are shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows that average payment terms in selected European countries change over time. Changes in the following years are clearly visible. Of the countries studied, the shortest terms are used in France, the longest in Spain. Payment terms in commercial transactions in Poland do not differ from the European average, but still, if we assume that these deadlines exceed 50 days, it means that sellers/service providers credit their contractors during this time, and this affects the financial liquidity of most companies in Poland.

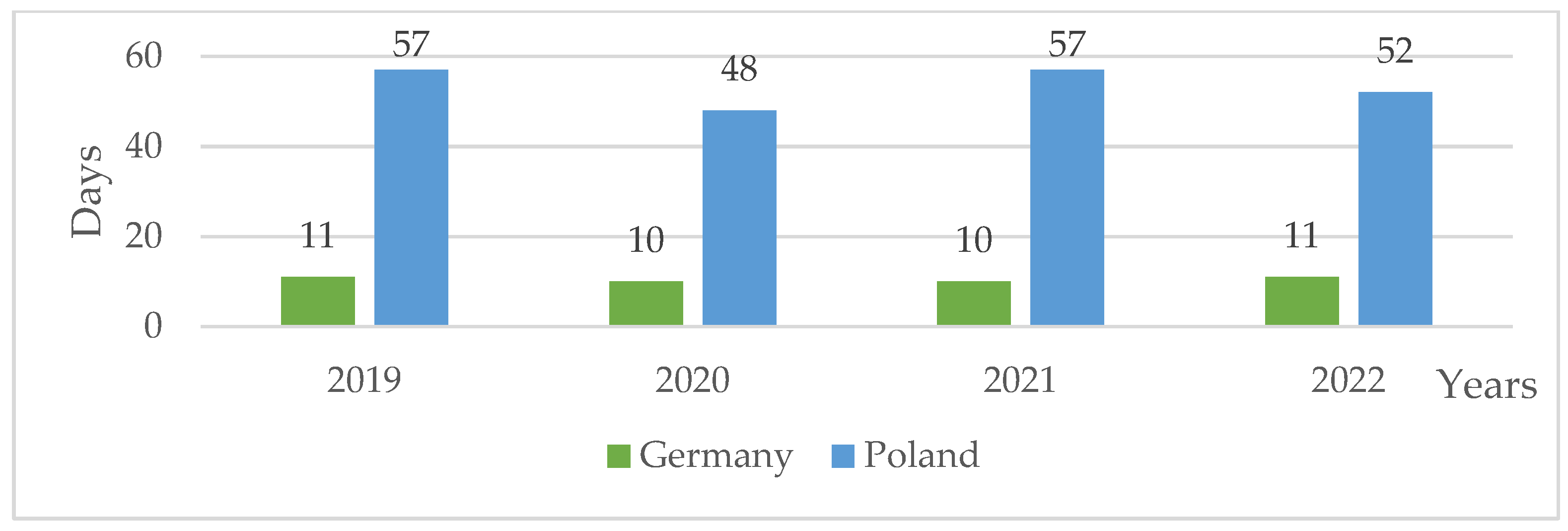

The data on the average delay in payment of an invoice in commercial transactions also seem to be worrying. In Poland, the average delay period in 2019–2022 is 53.5 days, while in Germany this deadline is 10.5 days.

Figure 5 shows the average delay period in B2B transactions in Poland and Germany [

8,

39]. These data indicate a high risk of delays in payment for goods/services in Poland and should encourage Polish companies to use instruments to prevent such actions. The data also include information on payment deadlines in the energy industry.

In addition, statistical data show that the risk of late payments or payments also results from the size of the company (the contractor).

Figure 6 shows the dependence of payments on time on the size of the company we are cooperating with.

It turns out that the greatest risk of late payments in Poland is linked with cooperation with large entrepreneurs, and the lowest with small and medium-sized enterprises. The presented chart clearly shows that, for example, in 2022, only 46% of large companies paid their liabilities resulting from commercial transactions on time, while at the same time, 86% of micro-entrepreneurs paid their liabilities in accordance with the contract. This creates a greater risk, because usually transactions made by large entrepreneurs are of higher values than those made with micro or small companies.

In addition, it is worth noting that the value of liabilities of Polish companies is constantly increasing, including those resulting from supplies and services.

Table 2 shows that the value of liabilities of Polish companies is constantly growing. This applies mainly to short-term liabilities. The highest growth rate is recorded in trade payables, i.e., in those to contractors. This means that Polish entrepreneurs constantly use loans from their business partners. This, in turn, raises risks related to the counterparty’s situation. Particularly large increases in this area were observed in 2020–2021, which was undoubtedly influenced by the situation caused by the COVID-19 epidemic. The increase in liabilities was also not helped by the decision of the Polish government to increase the interest charged on liabilities of enterprises in commercial transactions.

Statistical data show that Polish companies operating on the energy market (generation, trading) sell most of their energy to trading companies and on regulated markets [

37].

The list presented in

Table 3 shows that a significant part of energy sales is made to trading companies and end users (in the case of trading companies). This means that companies in the energy industry are also at risk of late payments or non-payment. This shows that instruments to reduce such risk will be used in this industry.

4.2. Risk of Late Payments in Companies Selling Energy in Poland

The data presented in the article indicate that Polish and European companies are struggling with extended payment terms. The data also show that the value of liabilities is constantly increasing. One of the aims of the article is to investigate the problem of late payments in energy companies. For this purpose, the financial statements of the largest electricity suppliers in Poland were analyzed, i.e., Energa Obrót S.A., PGE Obrót S.A., Enea S.A., TAURON S.A., E.ON Polska S.A.

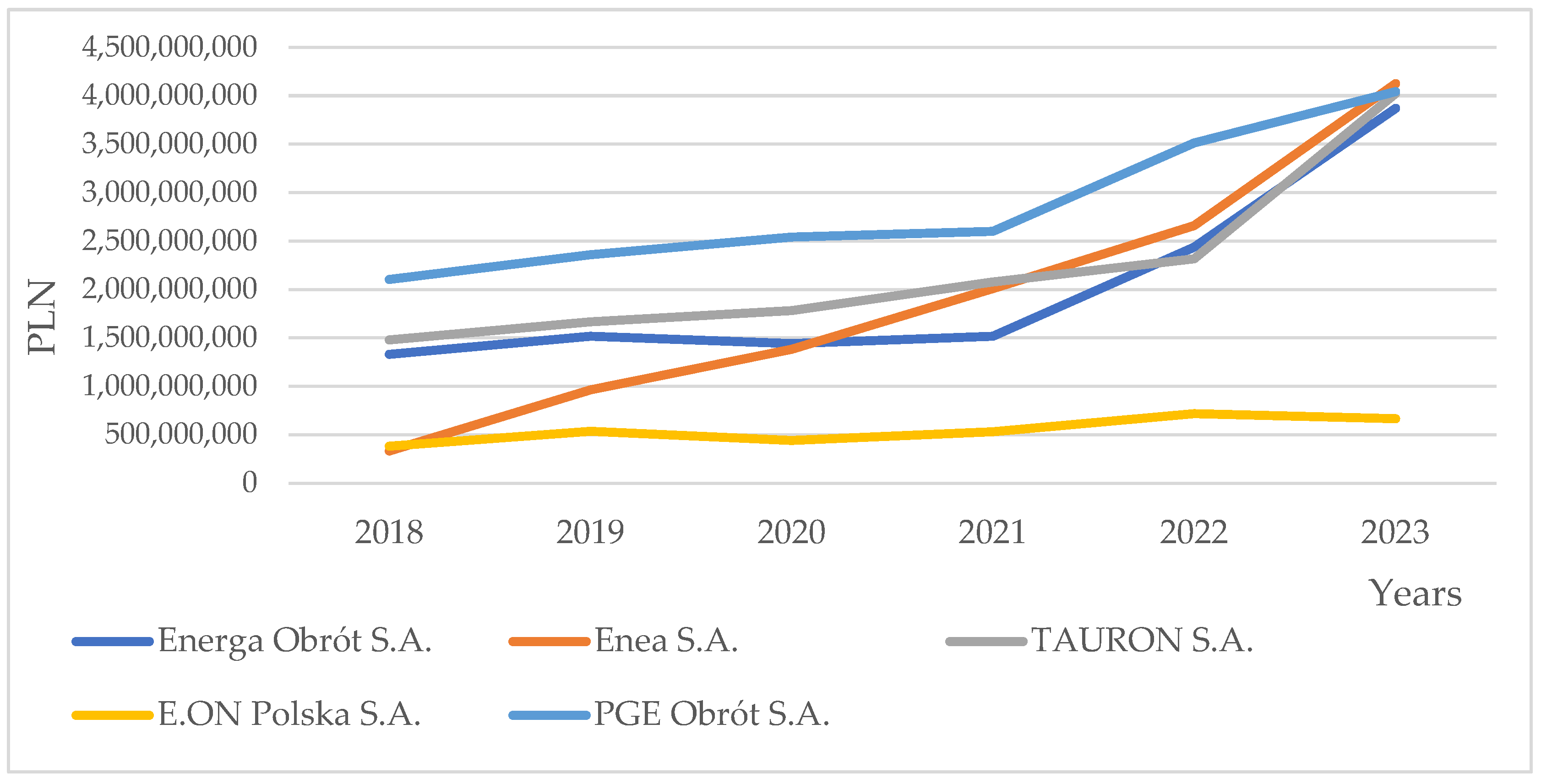

An analysis of the financial statements of the indicated companies shows that the balance of their trade receivables in 2018–2023 is gradually increasing (

Figure 7). The increase in receivables is influenced by many factors. It may be caused by an increase in the sales of energy (this fact was shown in the earlier part of the article), an increase in electricity prices in Poland, as well as market conditions or expectations of contractors. Relative stability in this respect, in the analyzed period, is demonstrated only by E.ON. Polska S.A.

Figure 7 shows a steady increase in receivables in the five largest companies selling electricity. It should be noted that in Poland there has been a steady increase in total receivables of enterprises in the analyzed period (on average 25% year-on-year in the analysed period) [

37], but the energy sector is characterized by higher increases, which is clearly shown by the conducted research.

The relation between the value of short-term trade receivables and total assets should also be noted (

Figure 8). It should be noted that the value of this indicator remains constantly at the highest level in PGE S.A. and Energa S.A. (on average about 63% in 2018–2023), and the lowest in ENEA S.A. This means that the largest Polish electricity distribution companies have more than half of their total assets in receivables. This means that these companies lend to their customers to a large extent, and it is necessary to examine the turnover ratio of receivables and their cycle to determine whether this cycle deviates from the average payment terms described in the earlier part of the article.

In order to calculate the receivables turnover cycle in five electricity distribution companies in Poland, formulas for receivables turnover and receivables turnover cycle commonly used in the literature on economic analysis of enterprises were used, i.e.,:

- 1.

, which allows you to indicate how often receivables are repaid on average in the audited company;

- 2.

, which makes it possible to calculate how long an enterprise waits on average for the repayment of its trade receivables.

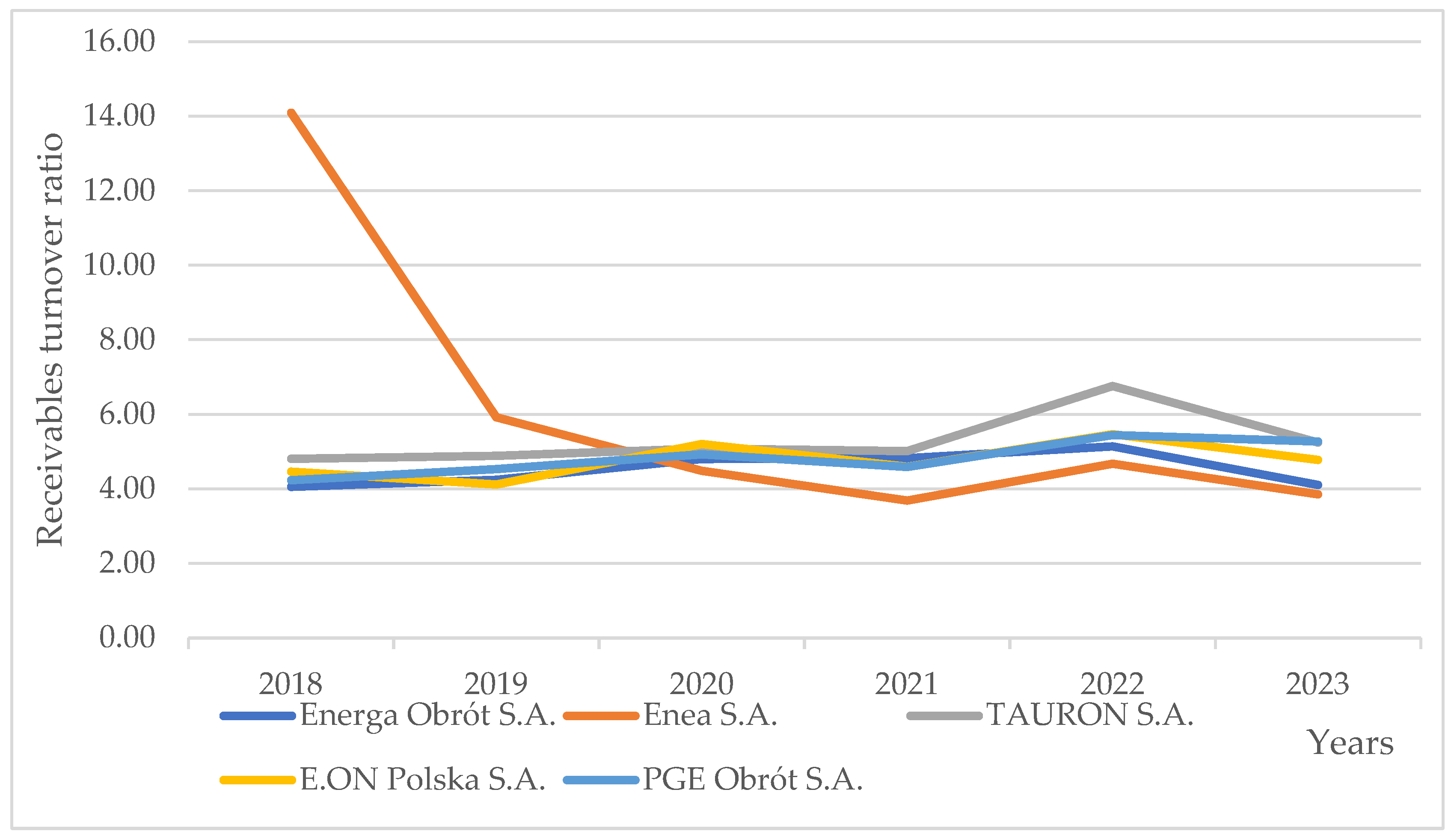

The results obtained and shown in

Figure 9 and

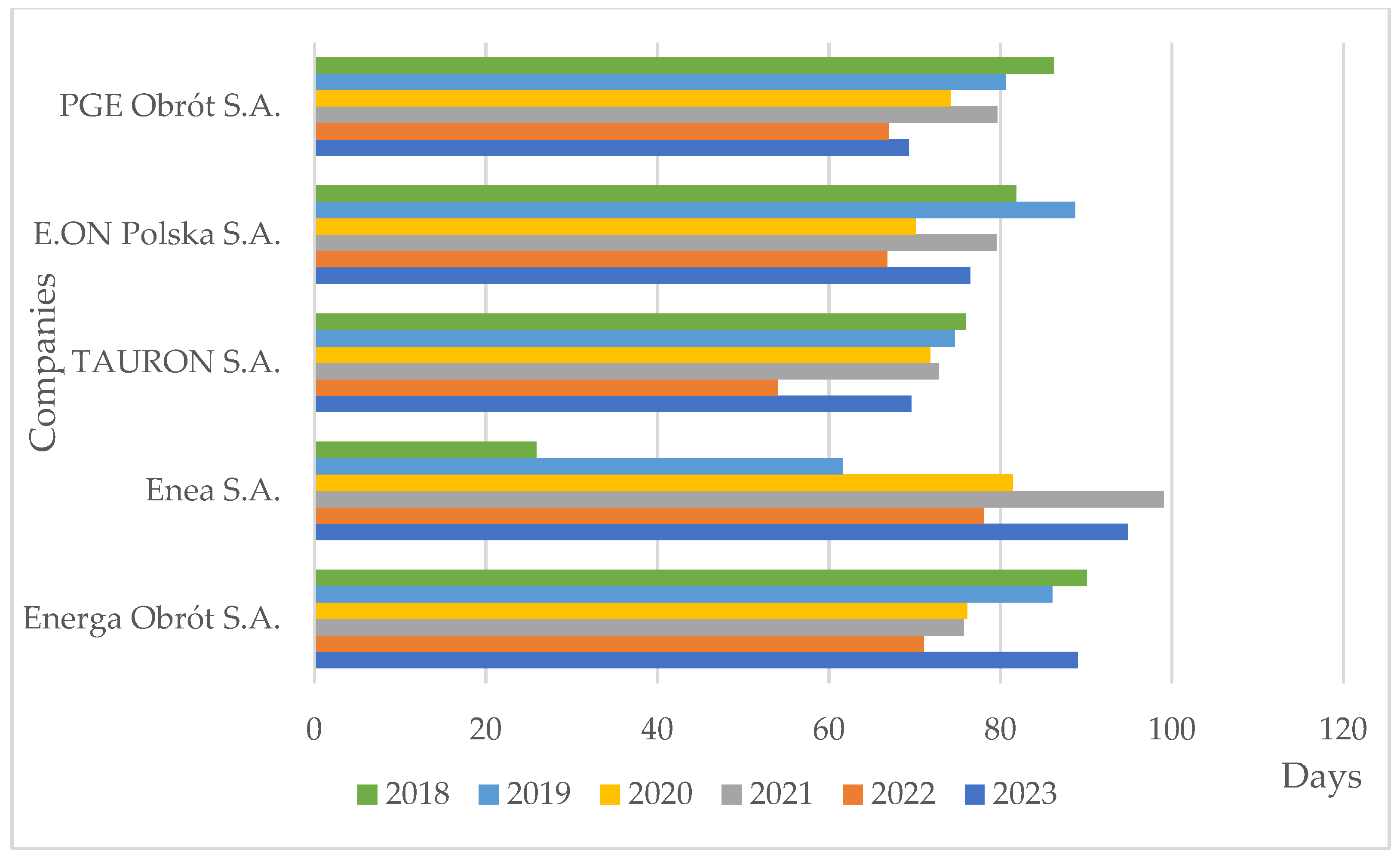

Figure 10 allow us to draw the conclusion that in terms of the receivables turnover ratio, the largest companies distributing electricity achieve similar results. This means a long cycle of debt recovery and longer waiting for payment by the contractor. This, in turn, forces energy companies to finance their contractors. The turnover of receivables takes place in the range of 4 to 6 times per year on average. Further results, in turn, show how long the receivables turnover cycle lasts on average per year.

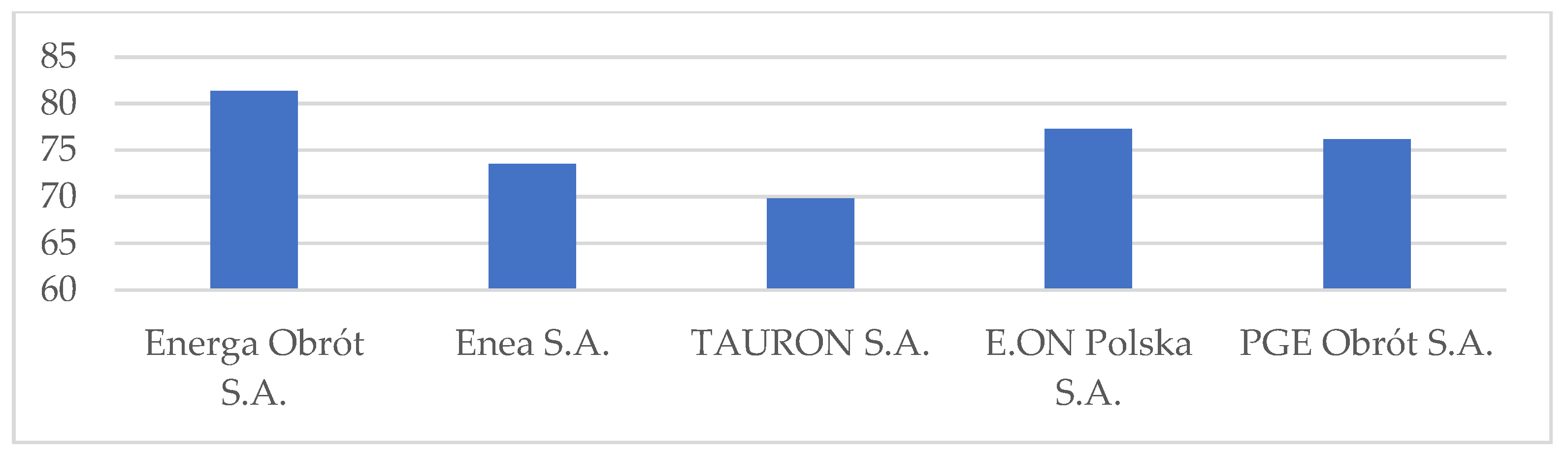

Figure 10 shows that the longest cycle of receivables in 2023 occurred in Enea S.A. and Energa S.A. The cycles of receivables turnover in the surveyed companies change in subsequent years. It should be noted that for all companies, the cycle was shortened in 2022, only to be extended again in 2023. The list of cycles in individual companies shows that the longest average cycles are in ENEa S.A. and Energa Obrót S.A. This is confirmed by the statement of the average receivables cycle over a period of 5 years (2018–2023). The average receivables cycle is in Energa S.A. and exceeds 80 days, and the shortest in Tauron S.A. (70 days) (

Figure 11).

The data presented in the figures indicate that the average receivables cycles in the surveyed enterprises are longer than the average payment terms in commercial transactions presented in

Figure 4.

Figure 12 presents comparisons of receivables cycles in in the surveyed energy companies to the average payment terms in commercial transactions in Poland.

Figure 12 shows that the average receivables cycle for the five energy forms examined is much higher than the average payment terms in commercial transactions in Poland. This means that these companies wait longer for payment from their contractors. This also proves the thesis that it is necessary for this group of entrepreneurs to use instruments that hedge their transaction risk.

The research showed that the longest average receivables cycle in 2018–2023 occurred in Energa S.A. Therefore, research on the management of receivables and liabilities in this company was deepened. The liability turnover cycle was calculated and data on overdue receivables were obtained.

The results of the research indicate that in Energa S.A., the cycle of receivables turnover in each of the analyzed years is longer than the cycle of liabilities turnover (

Figure 13).

These data are confirmed by analyses carried out on the basis of the annual reports of the audited company. They show that the company is struggling with prepayment receivables and a high balance of current receivables. Overdue receivables account for more than 20% of trade payables in some years. The

Figure 14 presents covered receivables in subsequent years in Energa S.A. The figure confirms that the value of liabilities of this company is constantly increasing. Overdue liabilities have a high value.

The data presented in this part of the article were aimed at checking whether there is a problem with transaction risk in companies selling electricity. The presented data showed that such a problem exists. It has been shown that the average cycles of receivables in energy companies exceed the average payment terms in commercial transactions in Poland in the analyzed period. In addition to the problem of extended payment terms for their deliveries and services, companies face the problem of delayed payments. This undoubtedly requires the use of tools in these companies to reduce and secure the risk of non-payment/delay of payment.

4.3. The Impact of Late Payments on the Entrepreneur’s Situation

Any delay in the payment of the entrepreneur’s invoice results in the need to finance this gap, and additionally, due to rising inflation, the costs of obtaining a loan from companies, and other risk factors, it causes actual losses in business activity [

5,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the impact of overdue payments on the company’s profit and the value of sales revenues that must be realized to cover the losses associated with it.

Trade credit is a “valuable gift” for the customer, who also uses the services sold to him, but on the other hand, it is a risk for the seller, whose profits fluctuate depending on the payment date. The impact of late payments on the seller’s performance can be easily measured. For example, if a company achieves a gross margin on sales of 4% (measured by the ratio of gross profit to sales revenue), this profit will be lost after four months of delay if the company’s cost of capital is 1% per month.

Table 4 shows after what time of payment delay the profitability of sales is zero, with further delays causing losses.

Table 5 shows that a loss of PLN 500 as a result of non-payment of receivables by the contractor, assuming that the company does not want to reduce the gross margin on sales (10%), results in the need to obtain additional sales revenues in the amount of PLN 5000.

In addition, if the payment transaction is not properly secured, it may turn out that the entrepreneur will be exposed to difficulties related to the recovery of receivables from the contractor. It should be noted that in the Polish legal system there are quite restrictive rules regarding the enforcement of amounts awarded from the debtor. In this case, Polish law provides that when arrears are enforced by a bailiff, the funds obtained are first used to repay the costs of proceedings, maintenance dues, employees, secured in kind, and tax receivables (Code of Civil Procedure, Art. 1025). This means that a creditor who bears the costs of court/enforcement proceedings may not recover his receivables.

Bearing in mind the above considerations, it should be concluded that it is necessary for entrepreneurs using extended payment terms in transactions to use legal instruments that reduce the risk of delay or non-payment of the invoice.

5. Selected Legal Instruments to Mitigate the Risk of Late Payments in the Operations of Energy Companies

Law and practice have developed many forms of securing monetary receivables in business transactions [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. The Energy Law Act also introduces special solutions in the energy industry. The choice of a specific security depends on many factors that are taken into account by the parties to the agreement. These include, among others, the cost of security, its effectiveness in the event of bankruptcy and the debtor’s arrangement, and convenience of application.

5.1. Types of Security

Polish law provides for personal and material methods of securing receivables, and the risk of non-payment can also be reduced by using bank payment instruments [

44,

48,

49].

Table 6 presents the types of collateral available in trade in Poland. It should be emphasized that each debtor is responsible for the debt with all his or her assets. In practice, however, it turns out that such responsibility sometimes turns out to be insufficient. Therefore, it is recommended to use additional instruments to secure payment transactions.

The list presented in

Table 6 shows that the choice of risk mitigation methods is rich. It is the parties to the transaction who decide which method will be the most advantageous for them in terms of the value of the transaction, formalities, costs, or the scope of risk hedging.

5.2. Payment Methods as a Means of Securing Receivables

First of all, it should be stated that one of the best ways to secure a receivable is to agree with the contractor on a method of payment that will protect the party to the contract. It is obvious that the best solution for the seller will be to pay in advance. The buyer will certainly negotiate the payment in arrears, usually with a deferred payment date. Therefore, determining the terms of payment requires the goodwill of both parties and negotiating terms that should satisfy the contractors.

Table 7 presents the payment methods available to entrepreneurs. Undoubtedly, for energy companies from the above-mentioned examples, the best is payment in advance, documentary letter of credit, documentary collection, or direct debit. Unfortunately, in practice, as shown by the data on average payment terms in Poland and individual European Union countries, contractors are most often interested in payment in arrears with a deferred payment date. Therefore, it is necessary to use other instruments to protect the security of payment, i.e., personal or material security.

5.3. Personal or Material Security

Among the most commonly used personal collateral in practice, we can distinguish a promissory note, a civil surety, and a promissory note surety. The use of a promissory note is regulated in most of the laws of countries of the world on the same principles, as it is based on the three Geneva Conventions of 1930, which contain uniform provisions on bills of exchange and promissory notes.

A promissory note is considered to be one of the simplest security features. It requires the issuer/debtor to submit a written statement including the issuer’s unconditional commitment to pay for the promissory note. Therefore, to issue a promissory note, it is enough to have a statement of the large holder written on a piece of paper. Such a promissory note is referred to as “blank” because it does not yet contain all the elements required by bill of exchange law. Issuing such a promissory note and handing it over to the creditor gives him the right to fill in the promissory note according to his own will. Often, in order to limit these possibilities of the creditor, a bill of exchange agreement (bill of exchange declaration) is drawn up for an incomplete bill of exchange, which specifies the conditions and manner of filling the bill of exchange. An undeniable advantage of having a correctly completed promissory note is the possibility of obtaining quick security on the debtor’s property/exhibition. On the basis of a promissory note, the court issues an order for payment in order for payment to proceed, which constitutes a security title without granting it an enforcement clause. This means that a creditor who has obtained such an order may order a bailiff to secure the receivables on the debtor’s property (seize the bank account, receivables, establish a mortgage, pledge, etc.). This security gives the creditor a guarantee that if the court dispute is successful, the creditor will recover the secured amounts from the debtor [

36,

50,

51]. A promissory note, due to the limited formalities related to its issuance and the adoption of the same rules regarding the understanding of a promissory note in most countries in the world, is one of the most common forms of security for commercial transactions.

A surety, on the other hand, is an agreement in which the creditor undertakes to perform the obligation towards the creditor in the event that the debtor fails to perform the obligation (Art. 876 §1 of the Civil Code). In practice, pactum in favorem tertii, i.e., an agreement between the debtor and the guarantor for the benefit of the creditor, is also used. For procedural reasons, it is important to maintain the written form of the guarantor’s statement, which is provided for under pain of nullity. The guarantor’s primary obligation is to perform the obligation if the relevant debtor fails to do so.

Bill of exchange sureties (Aval) provide additional security for every legal holder of a bill of exchange [

51,

52]. The guarantor of a bill of exchange is liable in the same way as the one for whom he has vouched. An important difference between a civil surety and a promissory note surety is that the guarantor’s obligation is valid, even if the obligation for which he guarantees is invalid for any reason except for a formal defect. Unlike the civil law, the bill of exchange law does not provide for the possibility of revoking a bill of exchange surety.

Among security measures, bank and insurance guarantees are listed as one of the best [

20,

35,

46,

48,

49]. A bank guarantee is a unilateral obligation of the bank-guarantor that after the entitled entity (the beneficiary of the guarantee) meets certain conditions of payment, which may be confirmed by the documents specified in the assurance and which the beneficiary will attach to the payment request made in the indicated form. The bank will perform a monetary performance for the benefit of the beneficiary of the guarantee—directly or through another bank (Banking Law, Art. 81) [

48,

49]). In the case of an insurance guarantee, there is no legal definition of this instrument. A guarantee is a type of contractual obligation incurred by a person who acts as a guarantor towards the beneficiary of this agreement to behave in a specific way in the event that the event expected by the beneficiary does not occur. However, the lack of a statutory definition is mitigated by the generally applicable principle of freedom of contract, on the basis of which it is possible to conclude such agreements by entities other than banks. These instruments are considered to be one of the best transaction securities, but due to the fact that they are payable, they are used for transactions involving large amounts. They are less common in the current turnover of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises.

5.4. Material Security

Unfortunately, in practice, it often turns out that personal security is not enough or the debtor cannot afford to obtain a bank or insurance guarantee [

35,

53,

54]. Then it is necessary to consider tangible collateral, the essence of which is that the creditor under the agreement obtains a specific right to the thing that will constitute the basis for the security if the debtor does not meet the monetary obligation on time.

Table 8 presents the types of collateral available to entrepreneurs in Poland.

Each of the collaterals presented in

Table 8 can be used in business practice, but only if the debtor has assets that can be the basis for security. From the point of view of the creditor’s interests, collateral in the form of a mortgage seems to be the best. This right encumbers the real estate, regardless of whose property it has become and with priority over the debtor’s personal creditors. Importantly, the establishment of a mortgage gives priority in the enforcement of claims, and claims secured by a mortgage are also protected in the event of restructuring or bankruptcy of the contractor [

19,

35,

50,

53,

55]. This is one of the best protections available to creditors. However, it requires the debtor to indicate the real estate or other right that could become the subject of the mortgage.

5.5. Other Tools to Strengthen the Position of the Creditor

It should be noted that in addition to institutions characteristic of civil law, but dependent on the will of the parties, Polish law introduces regulations that are also intended to prevent the extension of payments and reduce the risk of non-payment.

The first of such institutions is the provisions of the Act on Counteracting Excessive Delays in Commercial Transactions. This act introduces maximum payment terms in B2B transactions, stating that they cannot exceed 60 days. An exception to this rule is a situation in which the parties to the agreement have expressly agreed on a different deadline, and the creditor is not a micro-, small-, or medium-sized entrepreneur and setting a longer term is not grossly unfair to the creditor. The payment deadline in transactions in which the debtor is a public entity may not exceed 30 days. In addition, the Act introduces the principle that in each case of delay in payment of an invoice, the creditor who has fulfilled his obligation is entitled to statutory interest for delay in commercial transactions and, without a separate request, compensation for the recovery of receivables, which amounts to EUR 40 (transaction up to PLN 5000), EUR 70 (transaction from PLN 5000 to PLN 50,000), and EUR 100 (transaction over PLN 50,000). Unreliable debtors are therefore aware of the additional costs associated with failure to pay their liabilities on time. These costs will often exceed the value of a possible bank loan. The value of interest for delay in commercial transactions and compensation is therefore intended to encourage contractors to pay their liabilities on time.

Table 9 shows that the value of interest on liabilities in commercial transactions was constant in the years 2016–2017. This is similar in the case of statutory interest for late payment, which can be applied to any delay in payment. In Poland, there are no other legal regulations regarding interest on late payments to energy companies. However, they may introduce contractual interest in contracts, different from those provided for by the legislator. However, the condition for their introduction is the consent of the contractor. The list clearly shows that the amount of interest in commercial transactions is much higher than the statutory interest for delay. This is a nod from the legislator to entrepreneurs who can apply this interest in settlements with unreliable debtors, but they do not have to. On the other hand, a significant increase in interest is noticeable in 2022–2023, when in Poland, according to the Central Statistical Office of Polish, the year-on-year price increase was greater than 18%.

The second instrument introduced in Polish legislation aimed at encouraging debtors to pay their liabilities on time are the provisions of the procedure before courts in civil cases. According to the wording of the Polish Code of Civil Procedure, the court will issue an order for payment in order for payment to proceed if the facts justifying the pursued claim are proven by a bill attached to the statement of claim accepted by the debtor, a request for payment by the debtor and a written statement of the debtor on the recognition of the debt, and on the basis of an agreement attached to the statement of claim, proof of mutual non-monetary performance, proof of delivery of an invoice or bill to the debtor, and if the plaintiff seeks payment of a monetary benefit under the Act on Counteracting Excessive Delays in Commercial Transactions [

50,

51]. Such a prohibition on payment is a security and the creditor may seize a bank account, a claim, or establish a mortgage on its basis even before the final conclusion of the court dispute [

50,

52,

56]. This, in turn, will allow enforcement of the debt when the case is over.

Another solution for companies in the energy industry are special solutions dedicated to these entities. They allow energy companies conducting business activity in the field of energy transmission or distribution to suspend the supply of energy if the customer delays payment for the services provided for at least 30 days after the expiry of the payment deadline (Article 6b of the Energy Law). This instrument is quite effective because it usually makes it very difficult for the consumer to function without energy, both when the consumer is a natural person or an entrepreneur. In order to take advantage of the possibility of disconnecting energy, the energy company is obliged to call on the customer to pay within 14 days from the date of delivery of the request, which clearly states that it can be disconnected if payment is not made. In addition, the restoration of energy supply is associated with additional fees specified in the energy supplier’s tariff, which increases the burden on an unreliable debtor.

Another tool that can motivate energy consumers to pay their liabilities on time are solutions related to the functioning of Economic Information Bureaus in Poland. These entities have the right to collect data on natural persons, including consumers and other entities that do not pay their due liabilities. The offices operate on the basis of the Act on the provision of economic information and exchange of economic data. Thanks to the provisions of this act, energy companies can enter their customers on the debtors’ lists in these offices when the receivables are due, at least 30 days have passed from the date of sending the request to the debtor, and the debtor has not paid the debt within the deadline specified in the summons. In the case of consumers, an arrears of PLN 200 (approx. EUR 46) is sufficient, while in the case of entrepreneurs and other entities it is PLN 500 (approx. EUR 116). Placing the debtor on such a list usually makes it difficult to obtain sources of financing (loans, credits, leasing, etc.). This is a significant impediment for the person/entity that finds itself there.

6. Conclusions

The methods used in the article allow us to conclude that there is a problem of delayed or non-payment among Polish electricity suppliers. The largest Polish energy companies use longer terms for recovering receivables than the average payment terms applicable on the BtB market. The difference is on average more than 20 days compared to the average payment terms in 2019–2023, to the detriment of energy companies. In addition, the analysis of the relationship between the receivables cycle and the liabilities cycle showed that in terms of the internal policy of managing receivables and current liabilities, these companies also face the problem that they wait longer to repay receivables than to pay their own liabilities (the difference between the receivables and liabilities cycle is on average 36 days in the period 2018–2023). This means that companies selling electricity take longer to finance their contractors than they use the trade credit themselves. Such behavior of contractors affects the financial situation of energy companies by the need to credit their contractors, which may lead to a decrease in their profitability. Literature on finance indicates that one of the most important goals of entrepreneurs, including those operating in the energy industry, is primarily to increase their value. The process of assessing the impact of late or non-payment carried out in the article showed that each delay in payment by the contractor causes a decrease in the profitability of business activity. Phenomenological analysis, in turn, identified, described, and evaluated the available instruments to mitigate the risk of emptied payments and the risk of non-payment.

Thanks to the research, instruments that can be used by entrepreneurs from the energy industry have been indicated.

Unfortunately, it turns out that the best instruments are not willingly used by energy companies due to their costs or the formalities related to their use. The cost of the guarantee is usually set by banks as a percentage of the guaranteed sum (1–1.5% p.a., in addition, banks charge a commission for processing the application—approx. EUR 250) (Tables of fees and commissions PKO BP S.A., PKO S.A., Alior Bank S.A.). On the other hand, tangible collateral usually involves the need to go through a court procedure (the entry of a mortgage or pledge can take more than one month). This discourages companies from using this type of instrument for small- or medium-value transactions. The use of instruments tailored to the needs of the counterparty organizes the relations between the parties. They are aware of the consequences of failure to perform the contract on time, the costs associated with it, and, when using the indicated methods, usually try to prevent arrears.

7. Constraints in Data Availability or Methodology and Opportunities for Future Research

It should be noted that during the course of the research, difficulties were encountered in obtaining data related to the actual use of the proposed risk mitigation methods. The surveyed companies treat information about the risk mitigation methods used as part of a trade secret and a source of advantage over competitors. Such a policy seems understandable, because the security for the performance of contracts is part of their provisions and companies do not have the will to make this information available to the public.

In addition, due to the reluctance of energy enterprises to provide information on actual problems related to hedging transaction risk, it seems necessary to conduct further research in this area. Further scientific work may contribute to highlighting the problems with recovering receivables and presenting possible solutions to problems in the operations of energy companies, which should lead to increased financial security of their operations and proper performance of their functions.