Home Biogas Production from Organic Waste: Challenges and Process Optimization of Methane Fermentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Optimal Operating Conditions for a Methanogenic Consortium in Relation to Planned Substrates, Particularly Concerning the pH and Temperature of the Anaerobic Digestion Process

2.1.1. Microorganisms

2.1.2. DNA Extraction, 16S rRNA Gene Illumina MiSeq-Based Sequencing, and Sequence Processing

2.1.3. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) Analysis

2.1.4. Methodology for Determining the Molecular Composition of Biogas

2.2. Evaluation of the Quality of Waste Used as Feedstock for the Digester

2.3. The Methodology for Assessing Biogas Productivity from Green and Mixed Waste at a Technical Scale

2.3.1. Description of the Experiment in Reactor 1

- On the 33rd day of the experiment: 50 L of water was added to the reactor to better mix the waste with wood ash and stabilize the pH.

- On the 124th day of the experiment: 5.8 kg of waste was added.

- On the 184th day of the experiment: 5.0 kg of waste was added.

2.3.2. Description of the Experiment in Reactor 2

3. Results

3.1. The Conditions for the Operation of a Methanogenic Consortium, with Respect to the Planned Substrates, in Terms of pH and Temperature for the Process

3.1.1. Temperature Range of Methanogenic Consortium Activity

3.1.2. Determination of pH Range of Methanogenic Consortium Activity

3.2. Adjusting the Digester for Efficient Operation in the Polish Climate Throughout the Year Using Only Renewable Energy

3.2.1. The PN-EN ISO 23590:2022-05 [32,33] Standard Requirements

- Protected from any damage;

- Able to be installed aboveground or underground depending on local building requirements;

- Designed to ensure condensation is properly drained.

- A biomass inlet;

- A fermenter;

- Biogas storage;

- A biogas outlet;

- A biogas transfer system;

- A post-fermentation outlet;

- A hydrogen sulfide filter: to reduce the hydrogen sulfide content to between 50–100 ppm;

- An excess-biogas relief valve: this valve should automatically open if the pressure exceeds 20% of the system’s normal working pressure;

- A manual shutoff valve: installed parallel to the automatic excess biogas relief valve, to allow manual control over the flow of biogas from the storage unit.

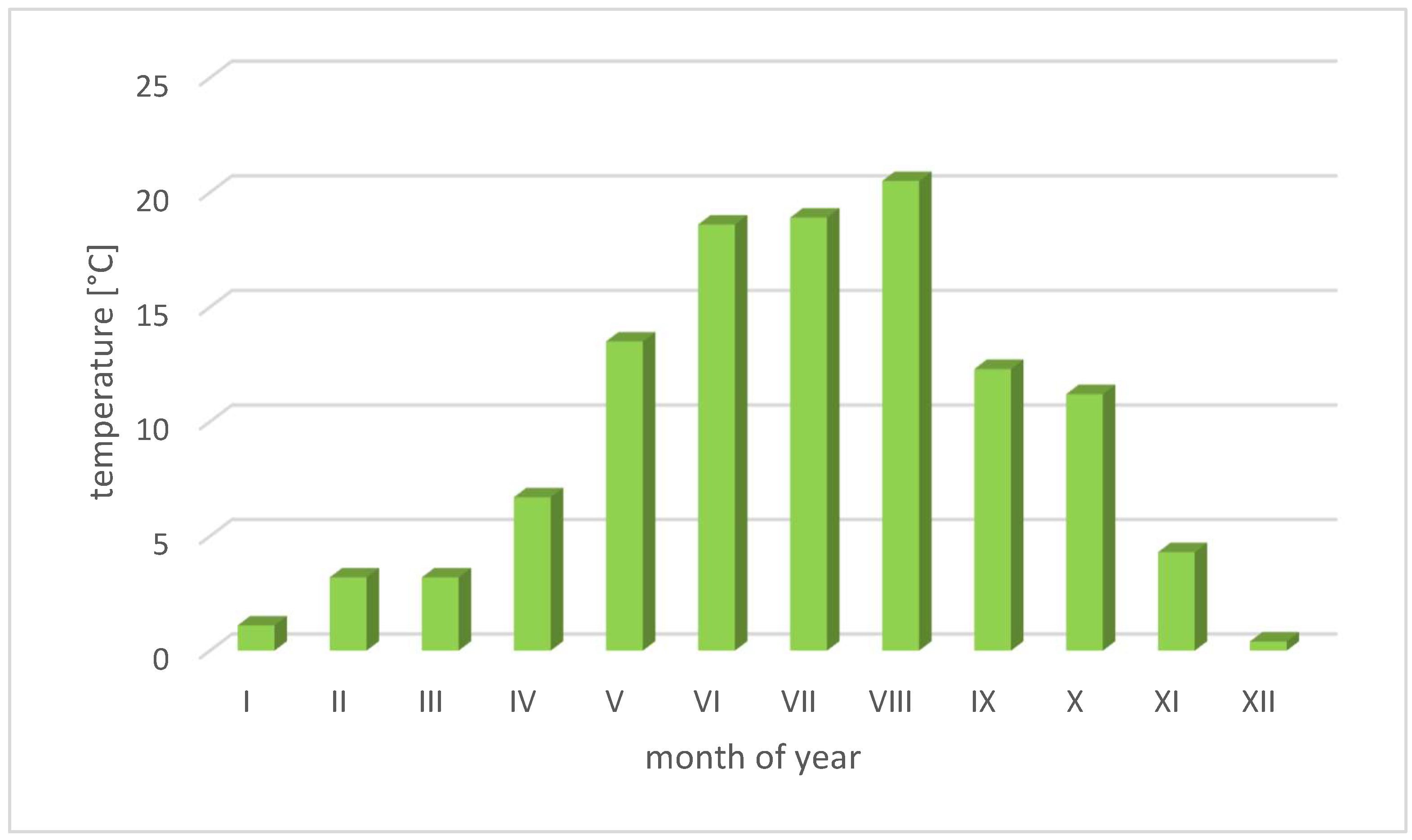

3.2.2. The Variability of Temperature Conditions in Poland

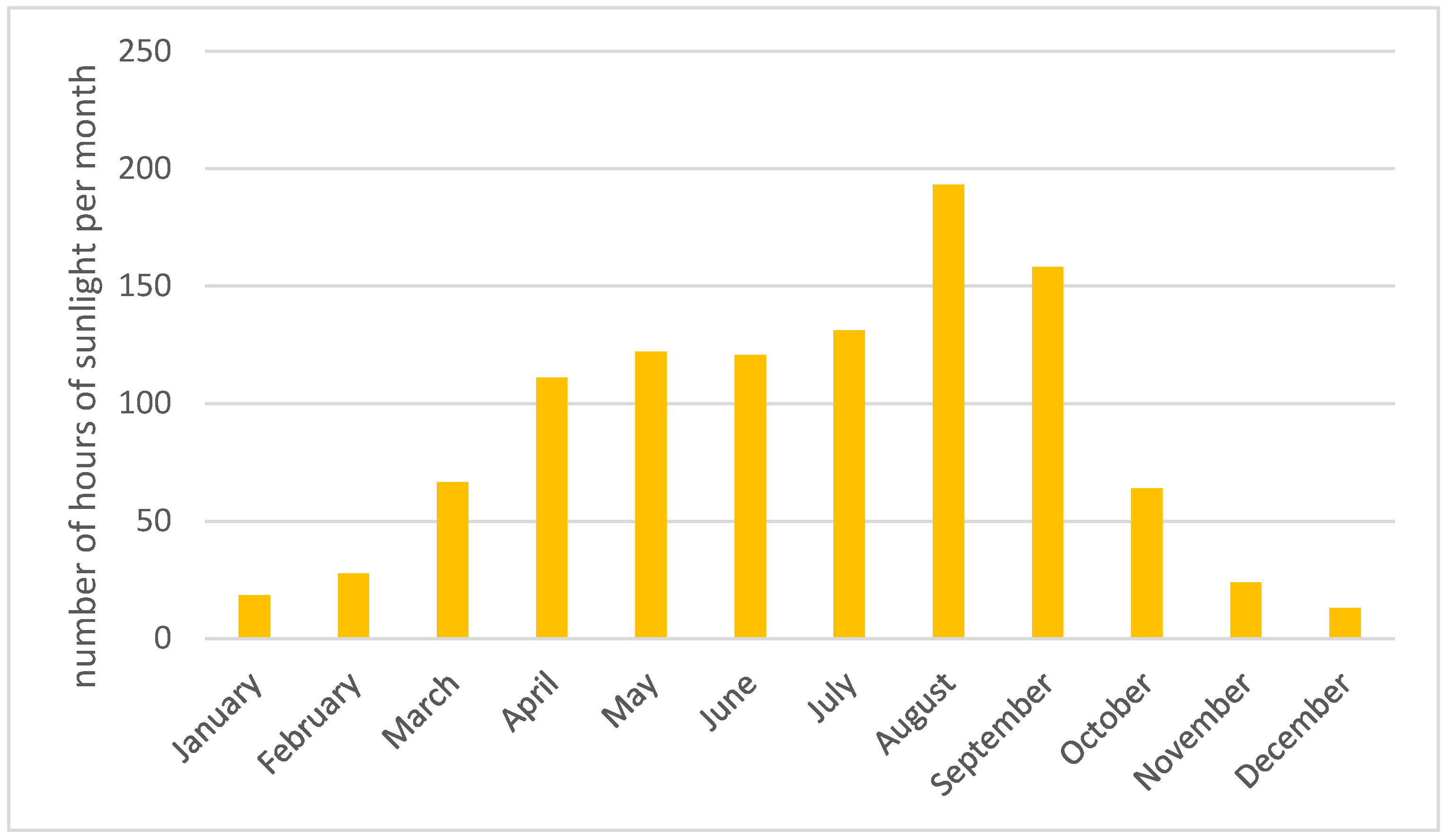

3.2.3. Protecting the Fermenter Against Weather Conditions

- Maximum power output: 360 Wp;

- Module efficiency: 19.2%;

- Power tolerance: 0~+5 W;

- Maximum nominal fuse current: 20 A;

- Number of cells: 120;

- Panel dimensions: 176.5 cm × 104.8 cm × 3.5 cm;

- Weight: 19.5 kg;

- Operating temperature range: −40 °C to +85 °C.

- Increased production costs;

- Increased system weight;

- Higher operational costs;

- Waste generation in the form of used batteries—promoting such a system seems environmentally and economically unjustifiable.

3.3. Assessment of Fermenter Operation, Along with Optimization of Process Conditions

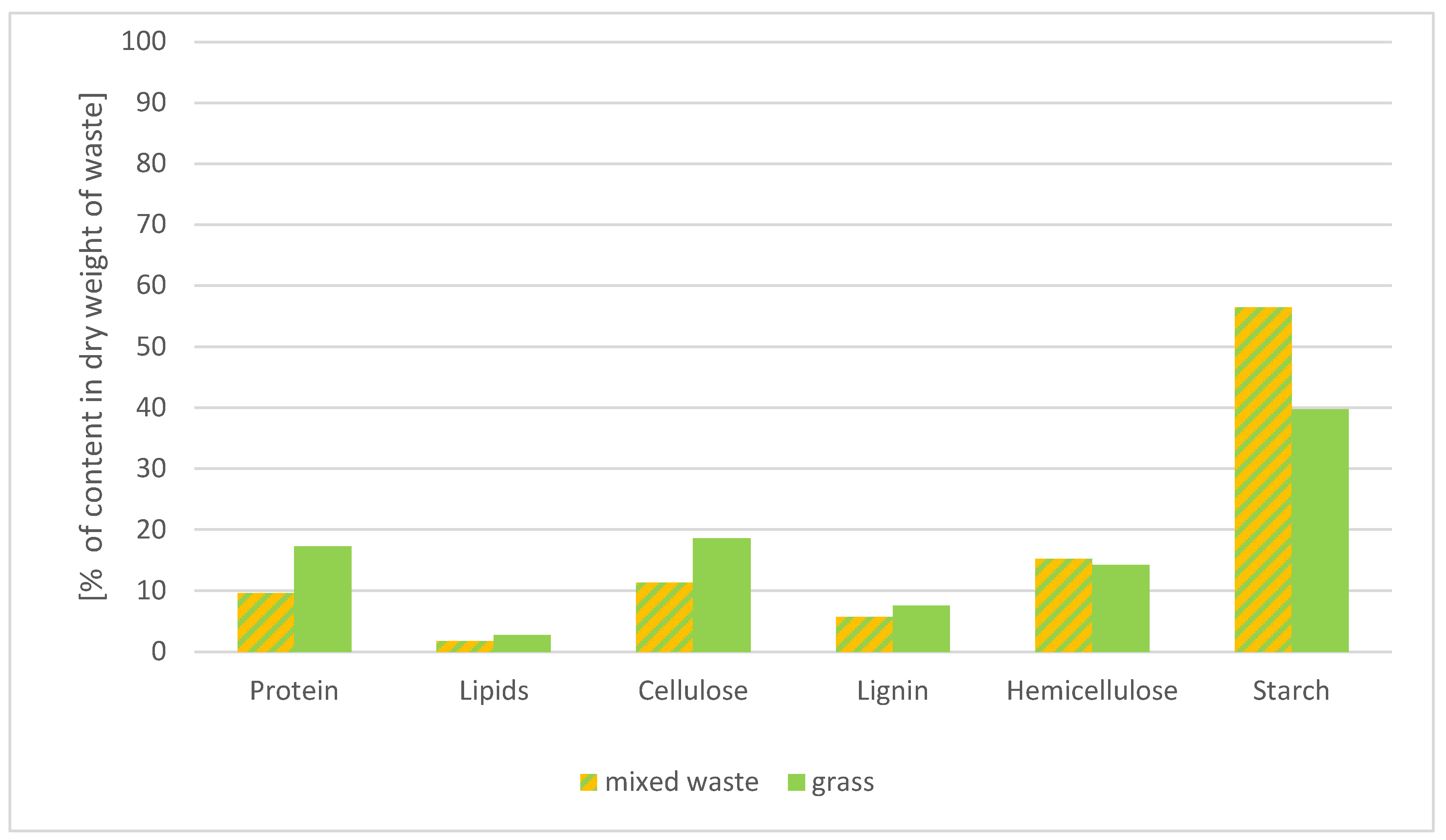

3.3.1. Assessment of the Quality of Waste Used as Input to the Reactor

- Dry weight;

- Ash content;

- Raw protein;

- Raw lipids or fats;

- Raw fiber;

- Neutral detergent fiber;

- Acid detergent fiber;

- Acid detergent lignin.

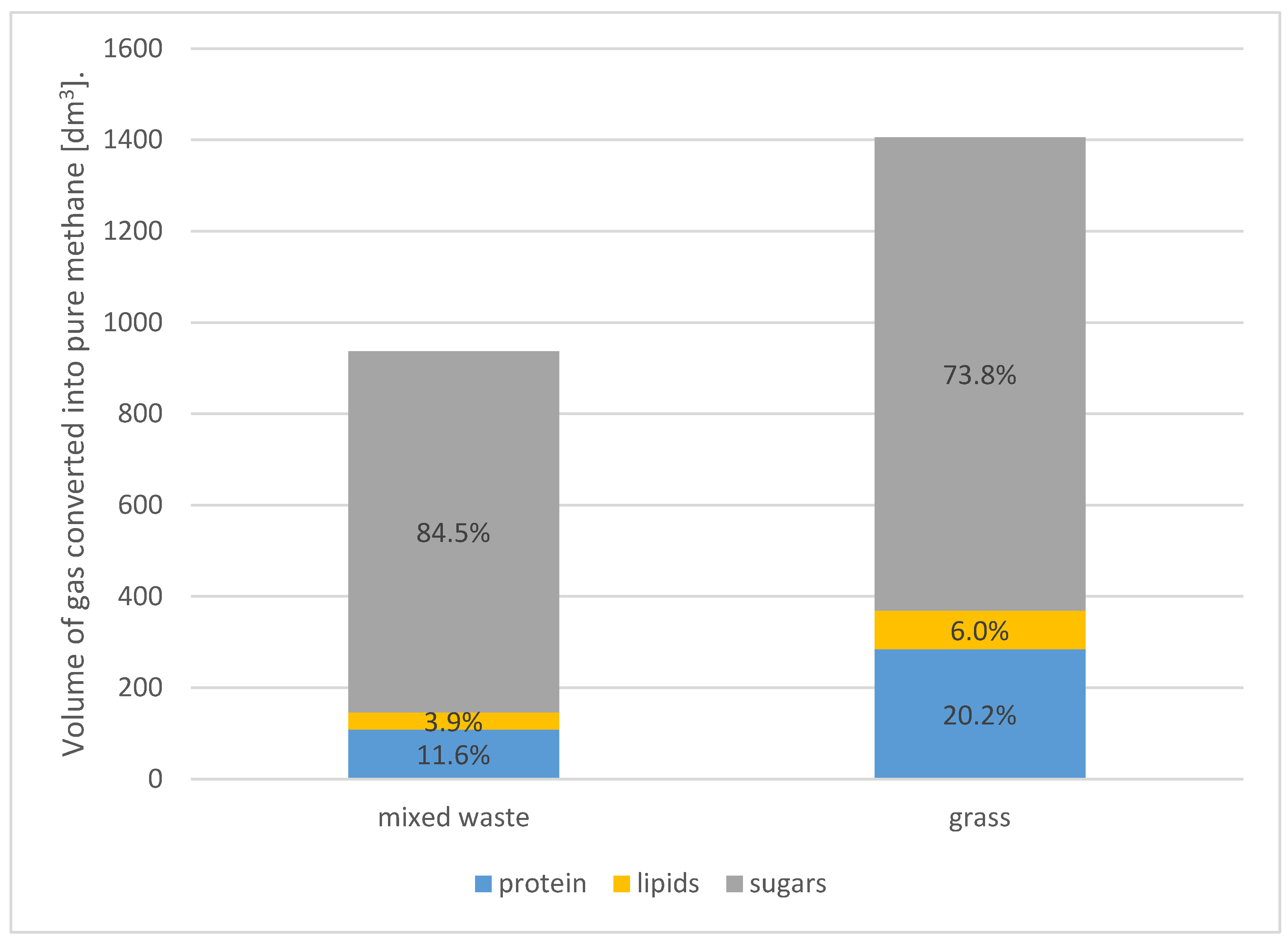

- Mixed waste (Sample 1): with 21.5% dry matter content, 10 kg of mixed waste can produce approximately 937 dm3 of biogas (converted to pure methane).

- Grass (Sample 2): with 31.2% dry matter content, 10 kg of grass can produce approximately 1405 dm3 of biogas (converted to pure methane).

3.3.2. Productivity of Biogas Obtained from Green Wastes in Laboratory Conditions

3.3.3. Results of the Assessment of Biogas Productivity from Green and Mixed Waste on a Technical Scale

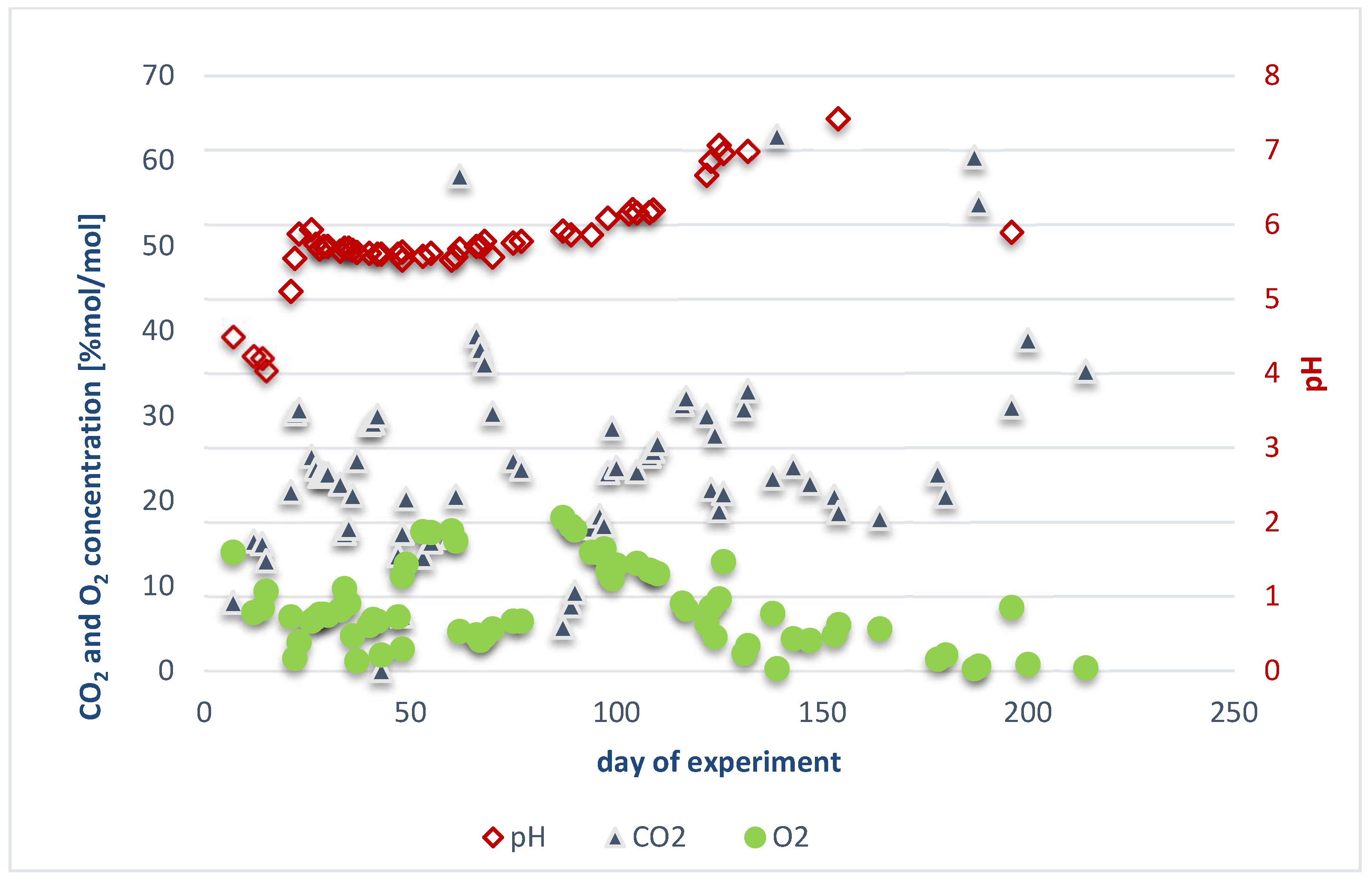

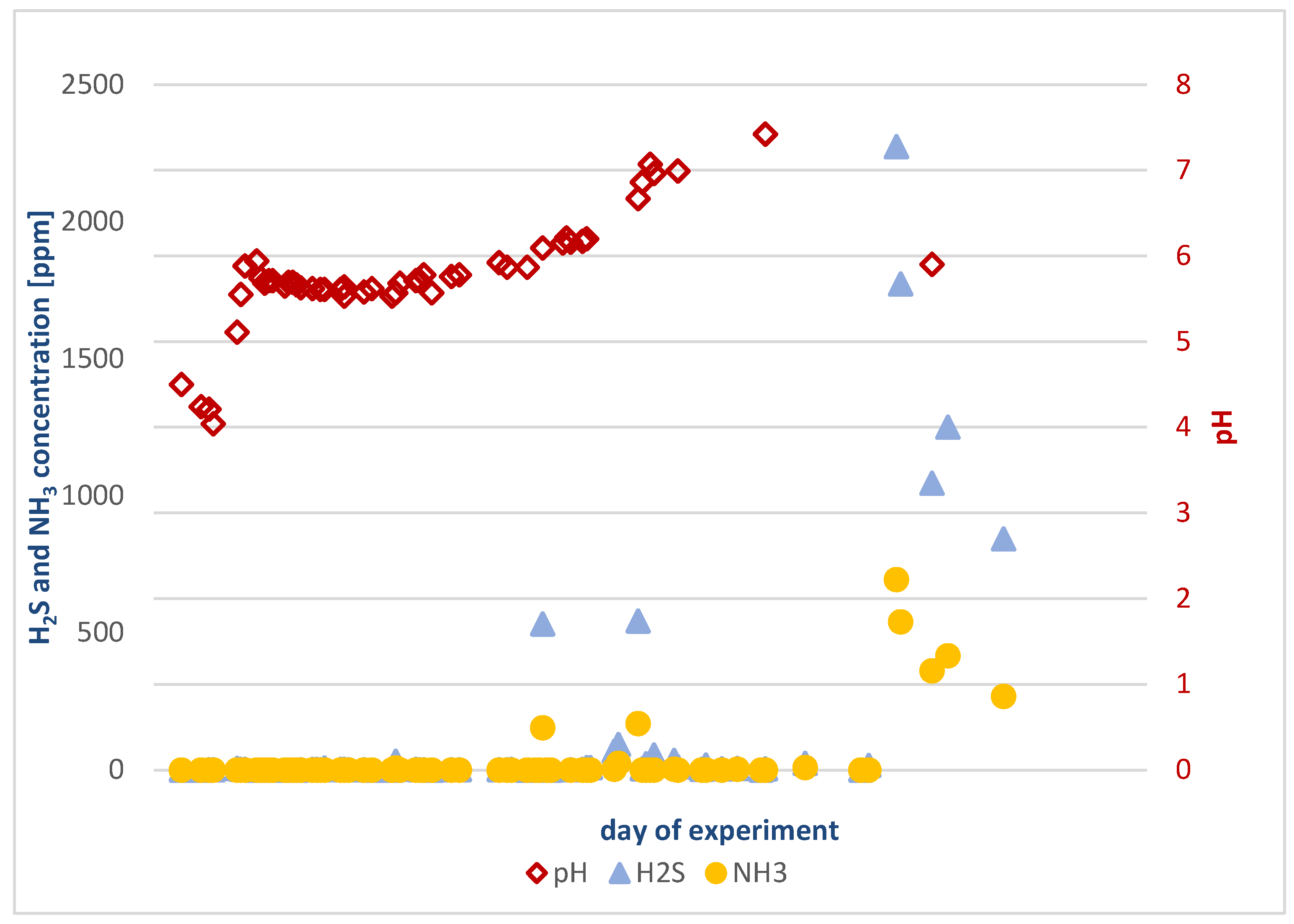

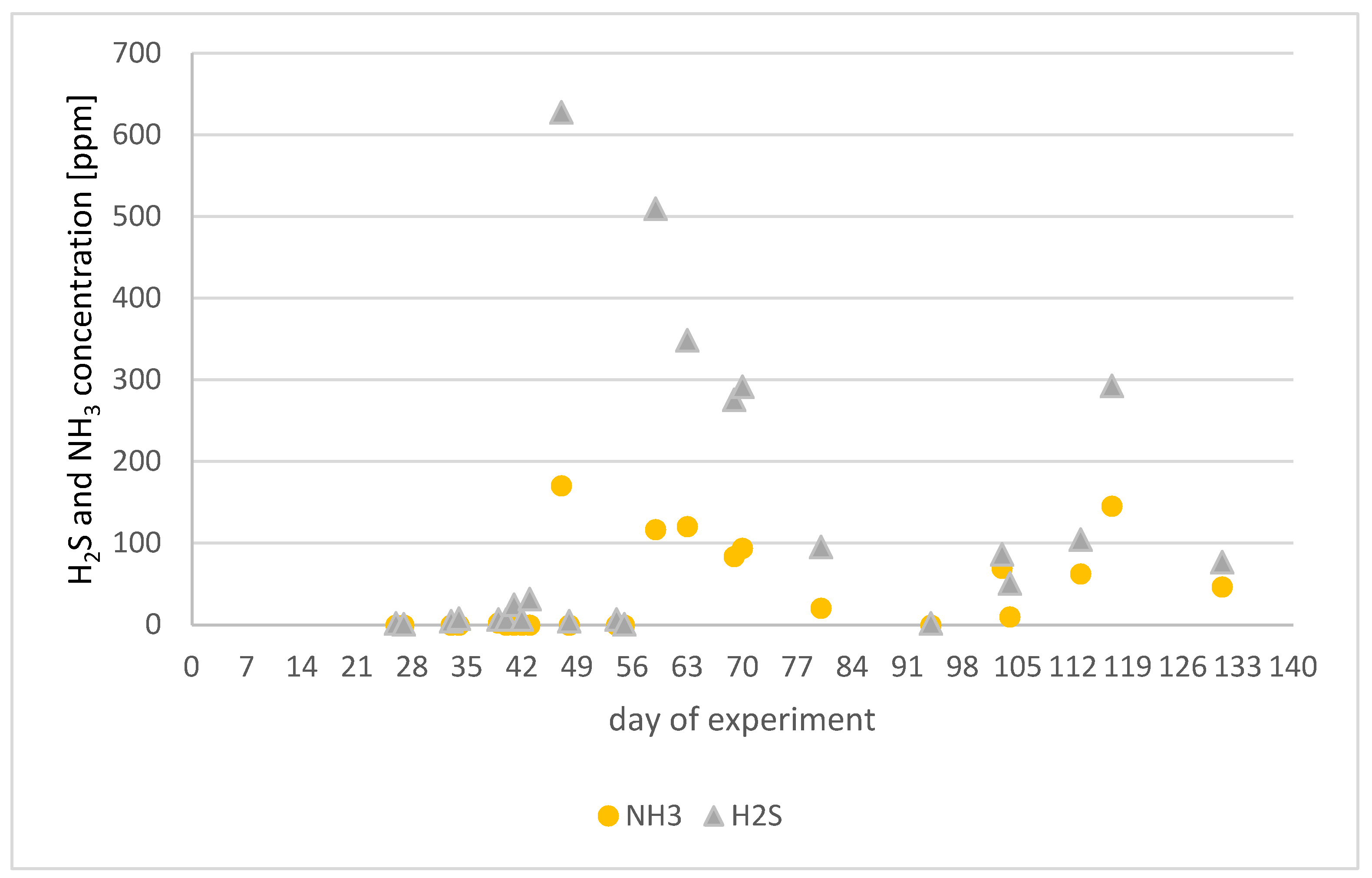

Results Obtained for the Experiment in Reactor 1

- Leachate pH ranged from 4.0 to 7.4;

- Biogas composition varied as follows:

- ▪

- Methane: 0 to 63.6%;

- ▪

- Carbon dioxide: 0.1 to 63.0%;

- ▪

- Oxygen: 0.3 to 18.1%;

- ▪

- Ammonia: 0 to 694 ppm;

- ▪

- Hydrogen sulfide: 0 to 2274 ppm.

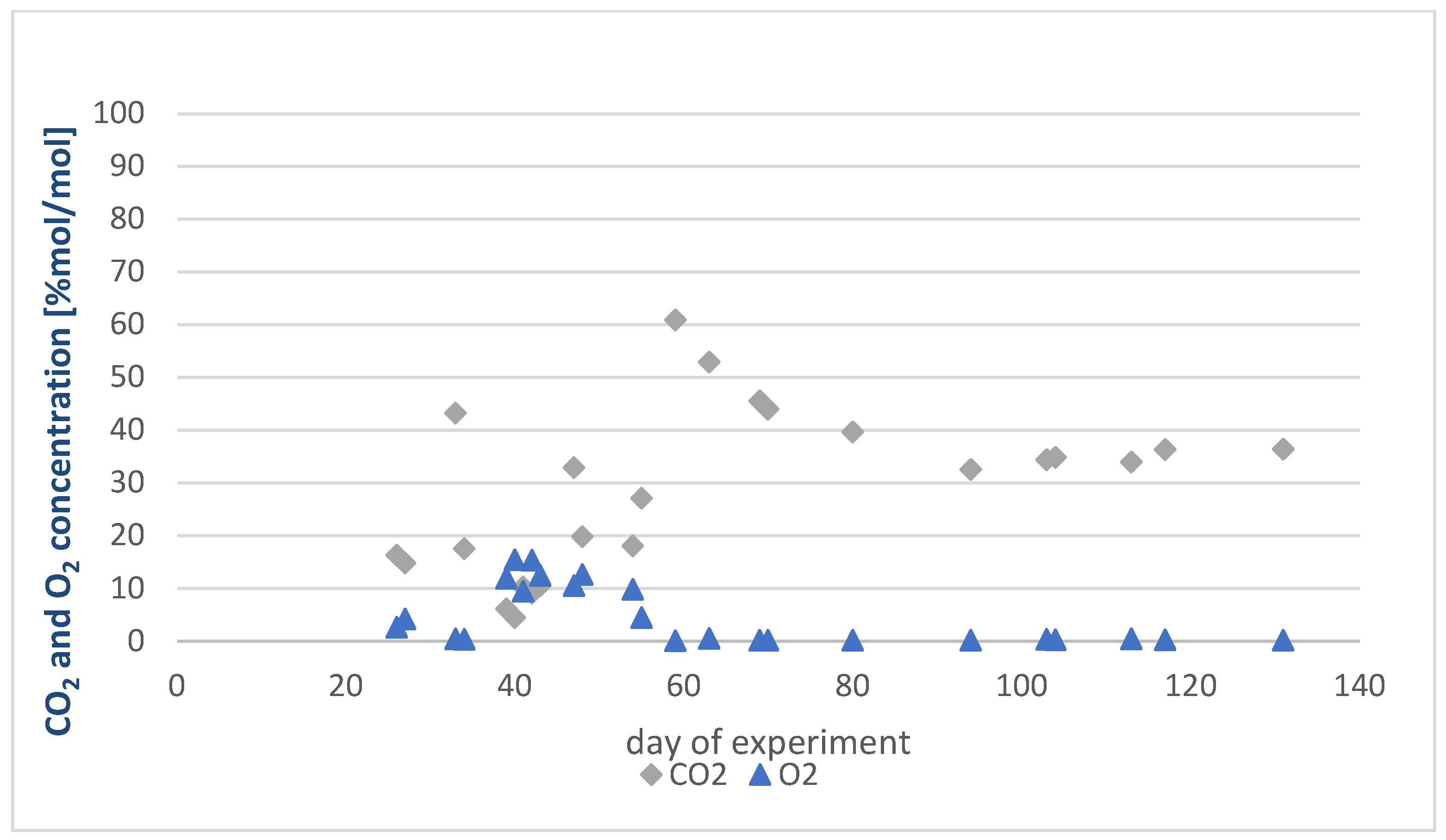

Results Obtained for the Experiment in Reactor 2

3.3.4. Possible Use of Waste from the Biogas Production Process in the Zero-Waste Biogas Plant for Domestic Use

4. Discussion

- The pH for methanogenesis is between 6.0 and 7.5. However, even a temporary decrease in pH to a value of 4.0 only temporarily inhibits the methanogenesis process, and this inhibition is reversible once the pH is raised to a minimum of 5.6.

- The temperature for methanogenesis is between 20 °C and 30 °C. A temperature drop to 4 °C, as well as a rise in temperature to 40 °C, causes inhibition of the methanogenesis process and changes in the composition of the bacterial consortium. However, at both of these temperatures, the methanogenesis process is still maintained, albeit at a reduced efficiency.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paviĉcić, J.; Novak Mavar, K.; Brkić, V.; Simon, K. Biogas and Biomethane Production and Usage: Technology Development, Advantages and Challenges in Europe. Energies 2022, 15, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piersa, P.; Unyay, H.; Szufa, S.; Lewandowska, W.; Modrzewski, R.; Ślężak, R.; Ledakowicz, S. An Extensive Review and Comparison of Modern Biomass Torrefaction Reactors vs. Biomass Pyrolysis—Part 1. Energies 2022, 15, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellacuriaga, M.; Gil, M.V.; Gómez, X. Syngas Fermentation: Cleaning of Syngas as a Critical Stage in Fermentation Performance. Fermentation 2023, 9, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Hussain, A.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.-S. Food waste fermentation in a leach bed reactor: Reactor performance, and microbial ecology and dynamics. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 274, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmohamadsadeghi, S.; Karimi, K.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M. Biogas production from food wastes: A review on recent developments and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, B.K.; Schmidt, T. Integrated Biogas Systems Local Applications of Anaerobic Digestion Towards Integrated Sustainable Solutions; IEA Bioenergy Task 37; IEA: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 978-1-910154-40-3. Available online: https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Integrated-biogas-systems_WEB.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Baker, L. Types of Biogas Fermenters. J. Pet. Environ. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 1000443. Available online: https://www.walshmedicalmedia.com/open-access/types-of-biogas-fermenters-109540.html (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Singh, A.K.; Pal, P.; Rathore, S.S.; Sahoo, U.K.; Sarangi, P.K.; Prus, P.; Dziekański, P. Sustainable Utilization of Biowaste Resources for Biogas Production to Meet Rural Bioenergy Requirements. Energies 2023, 16, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallipoli, A.; Braguglia, C.M.; Gianico, A.; Montecchio, D.; Pagliaccia, P. Kitchen waste valorization through a mild-temperature pretreatment to enhance biogas production and fermentability: Kinetics study in mesophilic and thermophilic regimen. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 89, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Outlook for Biogas and Biomethane: Prospects for Organic Growth; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/03aeb10c-c38c-4d10-bcec-de92e9ab815f/Outlook_for_biogas_and_biomethane.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Benyahya, Y.; Fail, A.; Alali, A.; Sadik, M. Recovery of Household Waste by Generation of Biogas as Energy and Compost as BioFertilizer—A Review. Processes 2022, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brémond, U.; Bertrandias, A.; Steyer, J.-P.; Bernet, N.; Carrere, H. A vision of European biogas sector development towards 2030: Trends and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, K.; Aslanzadeh, S.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Household Biogas Digesters—A Review. Energies 2012, 5, 2911–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, L.; Jha, H.; Sarkar, T.; Sarangi, P.K. Food Waste Utilization for Reducing Carbon Footprints towards Sustainable and Cleaner Environment: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupancic, M.; Možic, V.; Može, M.; Cimerman, F.; Golobič, I. Current Status and Review of Waste-to-Biogas Conversion for Selected European Countries and Worldwide. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. GUS—Bank Danych Lokalnych. 2023. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/temat (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Emmanuel, J.K.; Juma, M.J.; Mlozi, S.H. Biogas generation from food waste through anaerobic digestion technology with emphasis on enhancing circular economy in Sub-Saharan Africa—A review. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 3207–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Ge, X.; Yang, L.; Li, Y. Anaerobic digestion of food waste—Challenges and opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoić, R.; Čuček, L.; Ćosić, B.; Krajnc, D.; Smoljanić, G.; Kravanja, Z.; Ljubas, D.; Pukšec, T.; Duić, N. Green biomass to biogas—A study on anaerobic digestion of residue grass. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, N.R.; Nikhil, G.N. Assessment of microbial consortiums and their metabolic patterns during the bioconversion of food waste. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, S.P.; Lankiewicz, T.S.; Wilken, S.T.; Brown, J.L.; Sexton, J.A.; Henske, J.K.; Theodorou, M.K.; Valentine, D.L.; O’Malley, M.A. Top-down enrichment guides in formation of synthetic microbial consortia for biomass degradation. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 2174–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragsdale, S.W.; Pierce, E. Acetogenesis and the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 fixation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2008, 1784, 1873–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiga, M.; Kapusta, P.; Kania, M.; Szubert, A. Microbiological coal biogasification under laboratory conditions—Biogas quantity and quality. Nafta-Gaz 2018, 74, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubert, A.; Kapusta, P.; Matyasik, I. Parameters and methods for evaluation of lignite processing method into biogas. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2020, 56, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, R.M. Handbook of Microbiological Media, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeszcz, J.; Skalski, T.; Jankowski, L.; Kapusta, P. How do microbial communities deal with chronic hydrocarbon presence in oil seep soils? Data from historical hand-dug oil wells. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, D.A.; Amann, R. Development and application of nucleic acid probes. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 1991; Volume 8, pp. 207–248. [Google Scholar]

- Boetius, A.; Ravenschlag, K.; Schubert, C.; Rickert, D.; Widdel, F.; Gieseke, A.; Amann, R.; Jørgensen, B.; Witte, U.; Pfannkuche, O. A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nature 2000, 407, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Amils, R.; Sanz, J.L. Molecular ecology of anaerobic granular sludge grown at different conditions. Water Sci. Technol. 2003, 48, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzeszcz, J.; Steliga, T.; Kapusta, P.; Turkiewicz, A.; Kaszycki, P. r-strategist versus K-strategist for the application in bioremediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2016, 106, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, M.; Janiga, M. Elements of analytical method validation for determination of hydrocarbon compounds, N2, O2, CO and CO2 in the gas mixture by dual-channel, valve gas chromatograph AGILENT 7890A. Nafta-Gaz 2011, 67, 812–824. Available online: https://www.inig.pl/magazyn/nafta-gaz/NAFTA-GAZ-2011-11-05.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- PN-EN ISO 23590:2022-05; Wymagania dla Domowego Systemu Biogazowego: Projektowanie, Instalowanie, Eksploatacja, Konserwacja i Bezpieczeństwo. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 23590:2020; Household Biogas System Requirements: Design, Installation, Operation, Maintenance and Safety. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- IMGiW. Available online: https://www.imgw.pl/badania-nauka/klimat (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Megastyro. 2020. Available online: https://megastyro.pl/pl/wspolczynnik-przewodzenia-ciepla-czyli-jaki-styropian-kupic/ (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Flexipower Group. 2023. Available online: https://flexipowergroup.pl/sprawnosc-ogniw-fotowoltaicznych-zima-jaka-jest/ (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Weatheronline 2023. Available online: https://www.weatheronline.pl/weather/maps/city?FMM=1&FYY=2020&LMM=12&LYY=2023&WMO=12375&CONT=plpl®ION=0001&LAND=PL&ART=SOS&R=0&NOREGION=0&LEVEL=162&LANG=pl&MOD=tab (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Batstone, D.J.; Keller, J.; Angelidaki, I.; Kalyuzhnyi, S.V.; Pavlostathis, S.G.; Rozzi, A.; Vavilin, V.A. The IWA Anaerobic Digestion Model No 1 (ADM1). Water Sci. Technol. A J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2002, 45, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, S.; Vogt, A.; Kułażyński, M.; Łukaszewicz, M. Monitoring i Sterowanie Procesem Technologicznym Biogazowni; Politechnika Wrocławska: Wrocław, Poland, 2014; ISBN 978-83-63503-29-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sadecka, Z.; Myszograj, S.; Suchowska-Kisielewicz, M.; Sieciechowicz, A. Zeszyty Naukowe; Inżynieria Środowiska/Uniwersytet Zielonogórski: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2013; nr 150 (30) str. 3—33. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, C.; Carneiro, J.P. Use of Digestate as Organic Amendment and Source of Nitrogen to Vegetable Crops. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, A.P.; Dragisa, S.; Dror, I.; Garuti, M.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Repinc, S.K.; Muňoz, J.; Rodriguez-Perez, S.; Stres, B.; Usťak, S.C.; et al. Re-use of digestate and recovery techniques. In Trace Elements in Anaerobic Biotechnologies; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plana, P.V.; Noche, B. A review of the current digestate distribution models: Storage and transport. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 202, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witorożec-Piechnik, A.; Kopiński, J.; Markowska-Strzemska, E.; Woźniak, M. Environmental safety aspects of using the digestate from an agricultural biogas plant. Pol. J. Agron. 2023, 52, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanades, S.; Abbaspour, H.; Ahmadi, A. A critical review of biogas production and usage with legislations framework across the globe. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 3377–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PN-EN 437:2021-09; Test Gases—Test Pressures—Appliance Categories. Comite Europeen de Normalisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

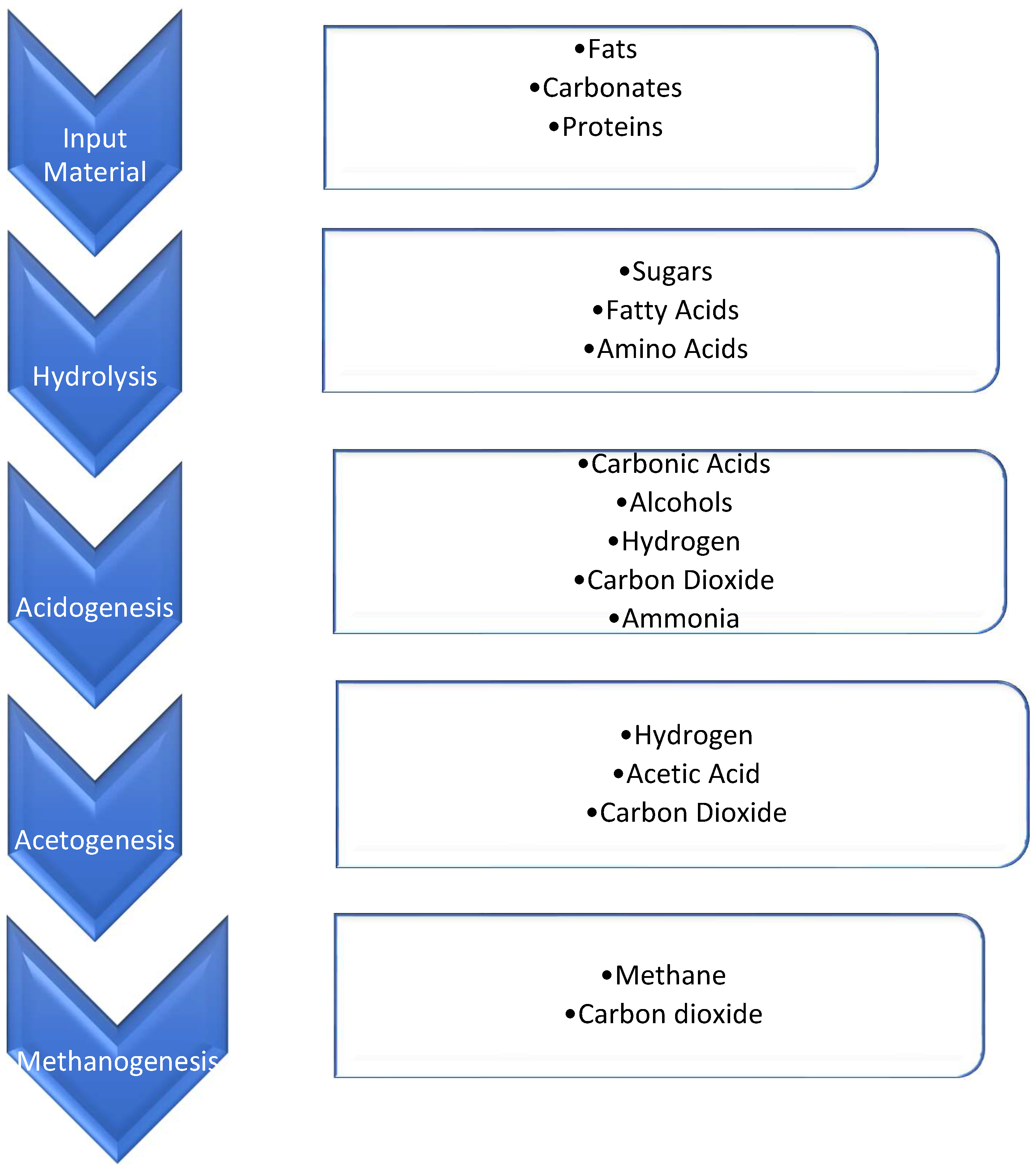

| Process Stage | Chemical Reactions | |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | (C6H10O5)n + nH2O → nC6H12O6 + nH2 | (1) |

| Acidogenesis | C6H12O6 ↔ 2CH3CH2OH + 2CO2 | (2) |

| C6H12O6 + 2H2 → 2CH3CH2COOH + 2H2O | (3) | |

| C6H12O6 → 3CH3COOH | (4) | |

| Acetogenesis | CH3CH2COO− + 3H2O ↔ CH3COO− + H+HCO3− + 3H2 | (5) |

| C6H12O6 + 2H2O → 2CH3COOH + 2CO2 + H2 | (6) | |

| CH3CH2OH + 2H2O → CH3COO− + 3H2 + H+ 2CO2 + 4H2 → CH3COOH + 2H2O | (7) | |

| Methanogenesis | CH3COOH → CH4 + CO2 | (8) |

| CO2 + 4H2 → CH4 + 2H2O | (9) | |

| 2CH3CH2OH + CO2 → CH4 + 2CH3COOH | (10) |

| Studied Parameter | Research Method |

|---|---|

| Crude fiber | PN ISO 5498:1996 AOAC Official method 962.09 |

| Neutral detergent fiber (NDF fraction) | ISO 16472:2006 Application note C.Gerhardt |

| Acid detergent fiber (ADF fraction) | PN ISO 13906:2009 AOAC Official method 973.18, Application note C.Gerhardt |

| Acid detergent lignin (ADL fraction) | PN ISO 13906:2009 AOAC Official method 973.18, Application note C.Gerhardt |

| Fat | PN-EN ISO 11085:2015-10 Commission Regulation (EC) No. 152/2009 of 27 January 2009, Annex III, point H (Official Journal L 54 of 26 February 2009) excluding sampling |

| Saturated fatty acids (SFAs) Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) Trans fatty acids (TFAs) Omega-3 fatty acids Omega-6 fatty acids | Gas chromatography with flame ionization detector (GC/FID), according to PN-EN ISO 12966-1:2015 + AC:2015-06, PN-EN ISO 12966-2:2017-05, point 5.2 PN-EN ISO 12966-4:2015-07 IB-17 Edition 4 of 10.03.2021 IB-05 Edition 6 of 12.05.2021 Sum/contents of individual acids from calculations |

| Nitrogen | Titration according to Kjeldahl, in accordance with Commission Regulation (EC) No. 152/2009 of 27 January 2009, Annex III, point C (Official Journal L 54 of 26 February 2009) excluding sampling Crude protein content from calculations. (conversion factor 6.25) |

| Protein | |

| Water | Commission Regulation (EC) No. 152/2009 of 27 January 2009, Annex III, point A (Official Journal L 54 of 26 February 2009) excluding sampling |

| Dry matter | |

| Total ash | Commission Regulation (EC) No. 152/2009 of 27 January 2009, Annex III, point M (Official Journal L 54 of 26 February 2009) excluding sampling |

| Total carbohydrates | From calculations, based on test results presented in this report, in accordance with IB-08, edition 3 (6 February 2014) |

| Total sugars | Titration according to Luff-Schoorl, in accordance with PN-R-64784:1994 |

| Sodium chloride | Titration method according to Mohra, in accordance with PN-A-82100:1985 |

| Key Parameters | Reactor 1 | Reactor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment duration (days) | 214 | 131 |

| Volume of reactor (dm3) | 200 | 200 |

| Type of substrate | Mixed waste | Grass |

| Amount of substrate (kg) | 20 + 10.8 | 58 |

| (dm3) | 70 + 100 | 95 |

| Consortium volume (dm3) | 2 | Leachate from Reactor 1: 16; fresh consortium: 2 |

| pH of the effluent | Between 4 and 7.4 | Between 5.3 and 7.5 |

| Effluent temperature (°C) | Between 15.8 and 27.4 | Between 19.5 and 27.4 |

| Use of sand during process start | No | Yes, 20 kg |

| Chemical Composition | Grass, 4 °C (150 Days) | Grass, 30 °C (40 Days) | Grass, 40 °C (150 Days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 49.1297 | 52.2752 | 9.15597 |

| C2 | 0.00015 | 0.00037 | 0.00078 |

| CO2 | 4.28880 | 38.7810 | 8.43944 |

| N2 | 39.5889 | 8.71202 | 72.4916 |

| O2 | 6.99217 | 0.23127 | 9.91216 |

| H2 | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| H2S | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Methanethiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Ethanethiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Dimethyl sulfite | <LQ | 0.00001 | 0.00077 |

| Propane-2-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Propane-1-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Butane-2-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Butane-1-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Compound | % Dry Matter |

|---|---|

| Protein | RP/DW·100% |

| Lipids | RL/DW·100% |

| Cellulose | (ADF-ADL)/DW·100% |

| Lignin | ADL/DW·100% |

| Hemicellulose | (NDF-ADF)/DW·100% |

| Starch | (RF + NfE-NDF)/DW·100% |

| DW—dry matter | |

| RP—crude protein | |

| RL—crude lipids | |

| RF—crude fiber | |

| NDF—neutral detergent fiber | |

| ADF—acid detergent fiber | |

| ADL—acid detergent lignin | |

| NfE—nitrogen-free extract (NfE = DW – RL – RP − RF) | |

| Compound | Biogas Yield Per kg of Dry Matter (dm3) | Methane Content in the Biogas (%) | Biogas Yield Converted to 100% Methane (dm3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | 830 | 50 | 415 |

| Proteins | 1018 | 52 | 529 |

| Fats | 1425 | 70 | 998 |

| Chemical Composition | Biogas, Grass, V Analysis, 290 cm3 (47 Days or the 30th Day) | Biogas, Grass, VI Analysis, 430 cm3 60 Days | Biogas, Grass, VII Analysis, 265 cm3 77 Days | Biogas, Grass, VIII Analysis, 330 cm3 90 Days | Biogas, Grass, IX Analysis, 170 cm3 107 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 40.5796 | 56.3358 | 57.3119 | 67.1503 | 68.8743 |

| C2 | 0.00105 | 0.00067 | 0.00047 | 0.00023 | <LQ |

| CO2 | 39.1901 | 37.7757 | 35.9168 | 30.6524 | 29.4282 |

| N2 | 16.5114 | 5.57402 | 6.65372 | 2.03175 | 1.49825 |

| O2 | 3.55756 | 0.16030 | 0.09821 | 0.16241 | 0.19894 |

| H2 | 0.02405 | 0.01973 | 0.00411 | <LQ | <LQ |

| H2S | 0.13525 | 0.13369 | 0.01463 | 0.00284 | 0.00022 |

| Methanethiol | 0.00050 | 0.00002 | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Ethanethiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Dimethyl sulfite | 0.00042 | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Propane-2-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Propane-1-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Butane-2-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

| Butane-1-thiol | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ | <LQ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holewa-Rataj, J.; Rataj, M.; Kapusta, P.; Brzeszcz, J.; Janiga, M.; Król, A. Home Biogas Production from Organic Waste: Challenges and Process Optimization of Methane Fermentation. Energies 2025, 18, 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18071745

Holewa-Rataj J, Rataj M, Kapusta P, Brzeszcz J, Janiga M, Król A. Home Biogas Production from Organic Waste: Challenges and Process Optimization of Methane Fermentation. Energies. 2025; 18(7):1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18071745

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolewa-Rataj, Jadwiga, Mateusz Rataj, Piotr Kapusta, Joanna Brzeszcz, Marek Janiga, and Anna Król. 2025. "Home Biogas Production from Organic Waste: Challenges and Process Optimization of Methane Fermentation" Energies 18, no. 7: 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18071745

APA StyleHolewa-Rataj, J., Rataj, M., Kapusta, P., Brzeszcz, J., Janiga, M., & Król, A. (2025). Home Biogas Production from Organic Waste: Challenges and Process Optimization of Methane Fermentation. Energies, 18(7), 1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18071745