1. Introduction

The proliferation of inverter-based distributed energy resources (DERs) has fundamentally transformed the operating paradigm of modern power systems. As synchronous generators are gradually displaced by converter-interfaced renewable sources, the underlying system inertia declines, leading to reduced frequency and voltage stability margins, especially in islanded microgrids and weakly interconnected zones [

1,

2,

3]. In such contexts, grid-forming power converters (GFM-PCs) have emerged as key enabling technologies that not only inject active power but also actively shape the voltage and frequency waveform of the local grid. These converters emulate the behavior of synchronous machines, generating voltage references and synchronizing with passive loads or other power electronics in the absence of a conventional stiff grid [

4,

5]. However, this enhanced responsibility also exposes GFM converters to more hostile and complex operating environments. In particular, when operating under nonlinear loads (e.g., diode-bridge rectifiers, electronic ballasts, welding machines) or impact loads (e.g., motors with inrush current, step-change inductive loads, clustered start-up events), the system behavior departs drastically from the nominal linear model. Voltage waveforms become highly distorted due to injected harmonics, while current profiles exhibit sharp temporal gradients [

6,

7]. These scenarios often result in inverter overcurrent, waveform degradation, or even protective tripping, threatening the reliability of both the converter and the system it supports. As a result, maintaining power quality while surviving adverse transients becomes a critical yet deeply conflicting control objective.

To mitigate these issues, the virtual impedance method has become a dominant strategy in GFM converter control. By artificially emulating a configurable impedance between the converter output and the load, virtual impedance allows the converter to modulate its response to dynamic events. Initial applications of this idea focused on parallel converter current sharing, circulating current suppression, and mitigation of voltage harmonics under steady-state conditions [

8,

9]. Researchers designed resistive or inductive virtual impedances to mimic damping effects and used fixed filter coefficients to suppress harmonic content [

8,

10]. These schemes, though conceptually straightforward, assumed relatively stable loading and were tuned manually under specific test cases. As research progressed, adaptive virtual impedance techniques began to surface. These control structures dynamically adjusted impedance values based on real-time electrical measurements, allowing the converter to switch between power quality enhancement and impact resilience modes [

11,

12]. For instance, some designs increased virtual inductance during load steps to smooth current waveforms, while others reduced resistance to suppress voltage harmonic distortion under nonlinear loading. However, almost all such designs remain fundamentally rule-based [

13,

14]. They rely on empirically derived thresholds, if-else logic, or linear gains to govern impedance adaptation. While practical, such heuristics lack robustness to unforeseen operating conditions and cannot generalize across diverse or compound disturbance types. Furthermore, they often exhibit poor coordination between conflicting objectives—optimizing for harmonic suppression typically reduces flexibility to absorb current surges, and vice versa [

12,

15].

To enhance intelligence and adaptability, reinforcement learning (RL) has gained increasing attention in power electronic control. In contrast to rule-based methods, RL offers a data-driven, model-free optimization paradigm where an agent interacts with a system to learn policies that maximize long-term cumulative rewards [

16,

17]. Prior applications of RL in power systems include frequency control, economic dispatch, voltage regulation, and grid-interactive building energy management. More recent studies have applied RL to microgrid dispatch, inverter control, and droop tuning. In these works, agents typically learn to map system observations—such as voltage deviations or frequency excursions—to appropriate control actions such as reactive power injections or frequency reference adjustments. Among RL techniques, the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) algorithm has emerged as a robust method for continuous-action control in high-dimensional and partially observable systems [

18,

19]. SAC maintains a stochastic policy and optimizes both expected return and entropy, ensuring that agents continue to explore even in late-stage learning. Its dual-critic structure mitigates value estimation bias, while entropy tuning enhances adaptability in volatile environments. SAC’s theoretical underpinnings and empirical robustness have made it a preferred method in robotics, autonomous vehicles, and energy systems alike. Yet, despite these methodological advances, RL has not yet been meaningfully applied to virtual impedance control in GFM converters [

11,

20]. Existing impedance tuning strategies, where present, remain predominantly static, discretized, or reliant on predefined logic. More crucially, none of the prior studies treat virtual impedance as a continuous, real-time policy variable whose dynamics are directly optimized through interaction with the power system. The impedance is not modeled as an action in a learning framework, nor is it constrained or regularized in the presence of safety, stability, and hardware limitations [

21,

22]. As a result, most RL applications in converter control abstract away the very layer—impedance shaping—that most critically governs converter-load interaction under difficult operating conditions [

20,

23,

24].

This paper addresses this long-standing gap by proposing a deep reinforcement learning framework for dynamic, policy-driven virtual impedance scheduling in grid-forming converters. We formulate the virtual impedance as a parameterized complex tensor with resistive, inductive, and capacitive components, each of which is treated as a continuous control action. The agent observes a rich set of state features, including voltage harmonic distortion, current derivative magnitudes, impedance deviation metrics, and statistical indicators of load behavior. The SAC-based policy then outputs the optimal impedance configuration that balances three competing objectives: harmonic suppression, impact load accommodation, and impedance smoothness. The reward function is multi-objective by design, integrating waveform quality metrics, actuation penalties, and system stability considerations. The policy is trained using an off-policy, entropy-regularized SAC algorithm, with twin Q-value estimators, automatic entropy temperature tuning, and replay-buffer-based updates. In addition to the learning algorithm, we present a rigorous physical and mathematical model of the converter-load system, encompassing LC filter dynamics, harmonic load injection, impact energy envelopes, and second-order smoothness constraints. Constraints are imposed on impedance action bounds, impedance variation rates, harmonic distortion limits, and terminal convergence to reference impedance values. These constraints ensure that learned policies remain physically realizable and comply with power quality standards. Moreover, we construct the impedance control space using frequency-domain parameterization, enabling selective suppression of targeted harmonic orders while retaining flexibility in transient management.

The novelty of our approach lies in the full-stack integration of physical modeling, constraint-aware optimization, and deep learning. Unlike heuristic control rules or shallow lookup methods, our policy continuously adapts impedance in real time, leveraging learned knowledge of system behavior to optimize performance across multiple dimensions. Unlike classical impedance filters, our learned controller is dynamic, nonlinear, and personalized to each evolving operating condition. And unlike black-box deep RL applications, our model remains interpretable, physically grounded, and aligned with converter design principles. This framework is validated through detailed nonlinear time-domain simulations incorporating realistic inverter models, LC filters, and diverse nonlinear and impact load scenarios. Performance comparisons with baseline impedance tuning methods reveal substantial improvements in voltage harmonic suppression, current peak limitation, and adaptive response quality. The policy generalizes well across unseen operating conditions and demonstrates resilience in the face of abrupt and unstructured disturbances. By elevating virtual impedance from a static setting parameter to a continuously learned control policy, this work introduces a new direction in intelligent converter control. The proposed framework not only pushes the frontier of impedance design but also bridges the methodological gap between nonlinear power electronics and modern policy learning algorithms. It offers a blueprint for next-generation power electronic systems that are adaptive, intelligent, and optimization-native by design.

To provide readers with a clear understanding of how this study differentiates itself from prior work,

Table 1 presents a structured novelty comparison covering four representative categories of virtual-impedance-based control strategies. Fixed virtual impedance, while widely adopted in practice due to its simplicity, is inherently limited because its parameters remain static even when the converter is subjected to nonlinear distortion or sudden impact-type loads. As a result, its performance degrades rapidly whenever the operating condition deviates from the nominal design point. Rule-based adaptive virtual impedance attempts to improve flexibility through heuristic updates, but the use of pre-defined thresholds and manual tuning processes restricts its robustness, generalization ability, and capability to coordinate multiple objectives simultaneously. Filtering- or resonance-based approaches successfully attenuate targeted harmonic orders, yet they fail to offer satisfactory transient performance and often struggle to cope with stochastic disturbances such as asynchronous motor starts or clustered impact events. Existing reinforcement-learning-based inverter control studies mainly focus on droop tuning, economic operation, or voltage regulation, but they do not formulate virtual impedance as a continuous control action embedded within a physically constrained decision space. In contrast to these limitations, the framework proposed in this work elevates virtual impedance to an optimization-native and continuously learnable policy variable. Through a constraint-aware Soft Actor–Critic formulation, the virtual impedance tensor—including resistive, inductive, and capacitive elements—is adjusted in real time based on harmonic indicators, current gradients, and historical impedance behavior. This enables the controller to simultaneously suppress waveform distortion, mitigate transient current overshoot, and maintain smoothness constraints required by physical hardware. The comparison in

Table 1 thus clarifies the methodological gap addressed by this work and highlights its contributions to adaptive, data-driven, and physics-informed grid-forming converter control.

2. Mathematical Modeling

Figure 1 illustrates the closed-loop architecture where a Soft Actor-Critic reinforcement learning agent adaptively adjusts virtual impedance in response to converter-load dynamics under nonlinear and impact loads, optimizing power quality and transient resilience through real-time feedback.

To ensure consistency between the continuous-time differential expressions in Equations (1)–(14) and the discrete-time reinforcement-learning updates, the system trajectories are evaluated at sampling instants

using a fixed discretization step. The first and second derivatives appearing in the continuous formulation are computed via centered finite-difference approximations of the form

and

for any state trajectory

. The reinforcement-learning policy and reward evaluations operate on the same discrete grid, ensuring that smoothness constraints, curvature limits, and energy-like functionals are implemented coherently within the sampled-data control and training loop.

The optimization objective in Equation (1) unifies three essential performance dimensions of grid-forming converter operation into a single penalization structure. The first component accounts for voltage harmonic distortion by evaluating the normalized deviation of each harmonic term from the instantaneous base voltage , where the denominator provides dimensionless scaling and prevents singularity. The additional term penalizes rapid temporal variation of harmonic components, thereby encouraging smoother voltage evolution under nonlinear or time-varying load conditions. The second component measures transient current severity through two complementary metrics. The quantity captures the worst-case instantaneous current gradient among all load branches and reflects the susceptibility of the converter to high-impact disturbances and overcurrent events. Meanwhile, the integral enforces higher-order smoothness, reducing excessive curvature and oscillatory behavior in current trajectories. Together, these terms quantify both the magnitude and dynamical regularity of current responses during nonlinear or impulsive loading scenarios. The third component evaluates the accuracy and smoothness of the virtual impedance scheduling process. The deviation term measures how closely the scheduled impedance matches the desired reference across all impedance channels , while the regularization term ensures physically feasible, non-oscillatory evolution of the impedance policy over time. The weighting parameters balance the relative contributions of harmonic suppression, transient mitigation, and impedance shaping, whereas the adaptive factors and allow the penalties to vary according to system operating conditions. Altogether, Equation (1) formulates a coherent and physically grounded scalar objective that captures the intertwined goals of waveform quality, dynamic robustness, and smooth virtual-impedance control.

To ensure notational clarity in Equation (1), all weighting symbols are explicitly categorized according to their mathematical roles. The quantities , , and denote dimensionless scalar coefficients chosen as fixed design parameters that establish the relative prioritization among harmonic-distortion suppression, transient-current mitigation, and virtual-impedance tracking within the unified objective. In contrast, the terms and act as adaptive modulation factors that vary with the operating condition, enabling the penalty intensities to scale dynamically in response to harmonic content, temporal derivatives, or impedance-variation rates. These adaptive elements are deterministic state-dependent functions rather than independent optimization variables, and their inclusion enhances sensitivity in regions where the converter exhibits higher dynamical stress. With these distinctions made explicit, the notation in Equation (1) clearly separates fixed scalar weights from context-aware scaling terms, ensuring that the structure of the objective function remains transparent, dimensionally consistent, and unambiguous.

To establish a clear mathematical connection between the quadratic penalization in Equation (1) and the exponential reward structure in Equation (2), a formal mapping is introduced to show that the reinforcement reward is constructed as a monotonic exponential transformation of the aggregated penalty terms. Specifically, if

denotes the instantaneous loss component extracted from Equation (1) at time step

, then the reward in Equation (2) follows the generic shaping rule

, where

is a dimensionless shaping coefficient ensuring that lower penalties correspond to higher rewards. Under this mapping, the squared deviations, temporal-derivative penalties, and impedance-tracking terms in Equation (1) translate directly into exponentially decaying reward contributions in Equation (2), preserving the ordering of control preferences while providing bounded gradients suitable for entropy-regularized policy optimization. This clarification ensures mathematical consistency between the optimization-based objective and the reinforcement-learning reward, demonstrating that Equation (2) is not an independent construct but a smooth, strictly monotonic, and RL-compatible transformation of the physical cost encoded in Equation (1).

The reward function in Equation (2) serves as the reinforcement-learning feedback signal at each time instant , providing a scalarized and entropy-augmented performance measure for policy updates. It consists of three exponentially decayed components corresponding to voltage harmonic distortion, transient current variation, and virtual-impedance mismatch, where the quantities , , and are normalized and smoothed to ensure differentiability, numerical robustness, and compatibility with gradient-based policy optimization. The mapping associated with each component establishes a monotonic transformation of the quadratic penalties in Equation (1), enabling soft saturation that stabilizes learning while preserving the ordering of control preferences. As the derivative of the exponential form diminishes for large deviations, the gradient magnitude naturally reduces in regions of severe distortion or impulsive transients, representing a known tradeoff between sensitivity and stability. To place the exponential structure within a general reward-shaping framework, the formulation in Equation (2) is presented alongside alternative mappings such as quadratic or Huber-type penalties, which provide stronger gradients under large deviations while maintaining smooth transitions near nominal operating regions. The entropy contribution is defined as the differential entropy of the continuous stochastic policy, i.e., , ensuring consistency with continuous-action reinforcement-learning methods and promoting well-structured exploration through entropy-regularized updates. The coefficients through balance the influence of harmonic suppression, transient mitigation, impedance tracking, and entropy-driven exploration. This integrated formulation presents Equation (2) as a stable, differentiable, and RL-compatible transformation of the physical penalties in Equation (1), establishing a coherent and mathematically explicit connection between optimization objectives and reward-driven policy learning.

To clarify the role of the normalization and the adaptive tradeoff coefficients in Equation (2), the normalization term ensures numerical stability by scaling heterogeneous physical quantities to comparable magnitudes, while the coefficients

through

operate as state-dependent reward-shaping factors rather than arbitrary free parameters. Each coefficient modulates the influence of its associated reward component based on instantaneous system behavior, using measurable quantities such as harmonic deviation, current-gradient magnitude, or impedance-variation rate to adjust its relative contribution. This structure aligns with standard adaptive reward-shaping mechanisms in continuous-control reinforcement learning, where scaling factors evolve implicitly with the system state to preserve sensitivity in critical operating regions while preventing excessive penalties under nominal conditions. The formulation therefore provides an explicit interpretation of the adaptive coefficients as deterministic functions of observed system conditions, ensuring that their role is grounded in physically meaningful state feedback rather than unspecified meta-learning or open-ended heuristics.

This fundamental equation describes the nonlinear differential dynamics at the output terminal of the grid-forming converter

, incorporating inductive, resistive, and capacitive elements

in a voltage-consistent formulation. The term

represents the inductive voltage drop, while

contributes to the resistive voltage component. The capacitive behavior of the LC output filter appears through the first-order derivative

, consistent with the physical relation

and ensuring that all left-hand-side terms reside in the voltage domain. On the right-hand side, the applied converter-side voltage

, the virtual-impedance-induced voltage

, and the perturbation term

are likewise expressed in volts, preserving unit consistency across the equation. The dependency on

introduces the intended feedback coupling between the system states and the control-adjusted virtual impedance, while the summation over channels

reflects the superposed contributions of multiple impedance components or control axes. This clarified formulation ensures that Equation (3) is interpreted as a voltage-balance relation consistent with standard inverter output-filter modeling, with explicit alignment among the physical components, their units, and their dynamic interactions.

Equation (4) expresses the harmonic-rich current waveform as a Fourier-based summation of sinusoidal components across harmonic orders h, where each term contains amplitude coefficients and together with the phase angles and . These coefficients are defined as waveform-derived quantities obtained through steady-state Fourier analysis of the converter output signals, extracted from measured or simulated current trajectories using discrete Fourier decomposition over a fixed observation window, ensuring that each harmonic term corresponds to a physically observable feature rather than an assumed or empirically fitted parameter. The amplitude coefficients quantify the magnitude of each h-th harmonic mode embedded in , while the associated phase angles specify the temporal alignment of each mode relative to the fundamental. The fundamental component is explicitly separated to isolate base-frequency behavior from higher-order distortion and to preserve analytical clarity. For completeness, the truncation order is chosen such that the retained harmonics capture all dominant distortion components while higher-order modes with amplitudes below a predefined threshold are omitted for computational efficiency. The decomposition is performed over a steady-state window synchronized to the fundamental period, ensuring that the sinusoidal basis functions remain orthogonal under the standard Fourier inner-product definition, even when the waveform originates from nonlinear devices such as rectifiers or switched-mode power supplies. With these clarifications, Equation (4) provides a harmonically truncated, orthogonally consistent, and data-grounded representation of the current waveform, ensuring that the harmonic structure used in subsequent cost and reward evaluations reflects physically measurable distortion content.

In Equation (4), the representation of the current waveform includes both sine and cosine components for each harmonic order to allow a complete parametrization of the in-phase and quadrature contributions of the

h-th harmonic. This formulation accommodates the general case in which harmonic modes arising from converter-interfaced nonlinear loads exhibit independent amplitude and phase characteristics that cannot be captured by a single phase-shifted sinusoid. The combined basis

therefore provides a flexible harmonic structure capable of describing asymmetric distortion patterns, skewed waveform shapes, and mixed even–odd harmonic interactions commonly observed in practical power-electronic environments. This expanded harmonic representation ensures that

can reconstruct both symmetric and asymmetric spectral features with high fidelity, thereby preserving the accuracy of the subsequent harmonic analysis and performance evaluation.

The expression in Equation (5) characterizes the temporal evolution of a dimensionless surrogate energy metric

, aggregating normalized deviations in electrical current and virtual-impedance parameters. The current-related component evaluates the relative deviation of

with respect to its reference value

, while the impedance-related component assesses the normalized Frobenius-norm deviation of

from the nominal reference matrix

. Through these normalizations, all contributions become unitless, enabling the surrogate energy to consistently represent the magnitude of system perturbations across heterogeneous domains without implying a physical energy interpretation in joules. The scalar coefficient

regulates the overall sensitivity of the metric, allowing the expression to function as a Lyapunov-inspired indicator that reflects how the system responds to deviations in current behavior and virtual-impedance settings. This formulation preserves mathematical coherence while providing a compact measure for assessing stability tendencies and guiding controller tuning.

This nonlinear equation defines the composite load power at time

t, consisting of a base static demand profile

and a series of impulsive impact components triggered at load switching times

. Each impact is weighted by a scalar coefficient

and modulated through a time-limited load-shaping kernel

, representing realistic ramp-up and decay dynamics post switching. The Dirac delta function

introduces mathematical impulsivity, useful for simulating real-world short-burst power surges.

This discrete-time nonlinear state transition equation defines the evolution of the full system state vector

, where

represents the system matrix (possibly time-varying due to control updates), and

reflects input-to-state mappings. Inputs include impulsive disturbances

, virtual impedance actions

, and external process noise

. This equation sets the foundation for closed-loop policy learning.

This expression formulates the virtual impedance tensor

for each converter unit

as a composite of tunable resistance

, inductive reactance

, and capacitive susceptance

, each modulated by dynamic scheduling weights

. The binary selector

governs the activation of specific impedance pathways or modes, enabling a time-varying, piecewise-activated impedance landscape essential for dynamic response shaping under diverse loading conditions.

Equation (9) imposes a smoothness constraint on the virtual impedance trajectory by bounding the time derivatives of its real and imaginary components. Since order relations are not defined over complex-valued quantities, the variation limits are applied separately to

and

, ensuring mathematical validity while preserving the physical distinction between resistive and reactive modulation. The threshold

, defined through the adaptive expression involving the rate of change of the RLC weighting parameters

, regulates the allowable impedance dynamics and prevents abrupt variations that could induce high-frequency oscillations or destabilizing jumps in the converter output. This formulation ensures that the virtual-impedance evolution remains both physically realizable and consistent with real-time learning-based control requirements.

Equation (10) imposes admissible bounds on the virtual impedance by constraining the real and imaginary components of

within predefined intervals. Since ordering relations are not defined for complex-valued quantities, the feasible set is expressed through separate box constraints on

and

, ensuring a mathematically meaningful formulation that reflects the independent physical limits associated with resistive and reactive modulation. The lower and upper bounds

and

are selected according to converter ratings, stability considerations, and application-specific requirements such as acceptable damping or harmonic-shaping behavior. This representation avoids the matrix positive-semidefinite interpretation implied by the symbol “⪯” and provides a correct scalar interval structure for virtual-impedance constraints.

Equation (11) specifies the total harmonic distortion at node

by evaluating the square root of the ratio between the aggregated squared amplitudes of all non-fundamental harmonic components and the squared magnitude of the fundamental voltage. This formulation follows the standard root-sum-square definition of THD used in harmonic analysis and international power-quality regulations such as IEEE 519 [

25], ensuring that the metric reflects the relative contribution of higher-order distortions to the overall waveform quality. The regularization term

in the denominator prevents numerical instability when the fundamental magnitude approaches zero, and the constraint

enforces compliance with permissible distortion limits defined by system-level specifications or operational guidelines.

This inequality imposes an upper bound

on the rate of change of current across all load lines

, effectively controlling surge current peaks during impact load events. By limiting the current derivative, this constraint also provides indirect protection against tripping phenomena in overcurrent detection circuits and ensures smoother transitions during control policy adaptation.

Equation (13) constrains the second-order temporal variation of current and voltage by bounding the curvature of

and

, thereby limiting rapid waveform bending that may induce high-frequency oscillations in converter operation. For compatibility with discrete-time reinforcement-learning updates, the continuous-time second derivatives are evaluated using a centered finite-difference approximation of the form

, where

represents the current or voltage trajectory. The resulting curvature measure is incorporated as a differentiable regularization term during policy training, ensuring that the learned control actions generate physically realizable and electromagnetically smooth waveforms while maintaining compliance with the bound

.

Equation (14) specifies the terminal condition for the virtual-impedance trajectory by requiring that the impedance begins from an admissible initialization

and that its final value at

lies within a normalized tolerance band around the reference configuration. The deviation

is scaled by the reference norm

to form a dimensionless relative error, and convergence is declared once this normalized discrepancy does not exceed the threshold

. This formulation removes the ambiguity associated with absolute versus relative tolerances and provides a precise criterion for evaluating terminal accuracy, ensuring consistent interpretation within the reinforcement-learning and control framework.

Equation (15) specifies the policy-generated virtual impedance by mapping the sampled observation vector

to the corresponding impedance action through the parametric function

. This mapping formalizes the control mechanism implemented by the neural network, where the observation state—comprising harmonic indicators, voltage–current measurements, and converter operating features—is transformed into a continuous-valued impedance command. The function

represents a learned approximation within the admissible policy class and provides a consistent interface between the system measurements and the control input. By expressing the virtual impedance directly as the output of the policy, Equation (15) establishes the functional role of the learning architecture without imposing redundant feasibility constraints, thereby maintaining conceptual clarity and aligning with standard reinforcement-learning formulations.

Equation (16) introduces regularity conditions on the policy function to ensure stable and physically meaningful control actions. The Lipschitz-type inequality imposes incremental consistency by limiting how rapidly impedance outputs may vary in response to changes in the observation space, preventing abrupt control transitions under small perturbations of system states. The bounded-output condition further constrains the amplitude of admissible impedance commands, ensuring that the generated actions remain within implementable hardware and stability limits. Together, these assumptions provide a mathematically coherent description of the policy’s functional behavior, strengthen the well-posedness of the learning-based controller, and replace previously redundant constraints with structurally meaningful regularity properties.

3. Method

The core objective of this work is to develop an adaptive control strategy that enables a grid-forming converter to intelligently regulate its virtual impedance in real time under uncertain, high-distortion operating conditions. This section presents the reinforcement learning-based control framework that achieves this goal by treating the virtual impedance tensor—comprising dynamically adjustable resistive, inductive, and capacitive components—as a continuous control action. Unlike traditional rule-based or offline-tuned impedance methods, our approach leverages a stochastic policy trained via deep reinforcement learning to map observed electrical features to optimal impedance profiles. The method is formulated as a continuous-state, continuous-action Markov Decision Process (MDP), where the converter and its surrounding environment (including nonlinear and impulsive loads) constitute the dynamics, and the agent acts through impedance shaping at each control interval. To enable effective policy learning, we design a structured observation space incorporating key time-domain and frequency-domain features, such as voltage harmonic content, output current gradients, and historical impedance settings. The action space is represented by a set of normalized impedance parameters constrained by physical feasibility and stability considerations. The reinforcement learning algorithm is based on the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) framework, chosen for its ability to handle multi-objective, continuous-action tasks while maintaining stochastic exploration through entropy regularization. Within this framework, the agent is trained to maximize a composite reward signal that penalizes voltage total harmonic distortion (THD), transient current overshoot, and unnecessary impedance fluctuation. The remainder of this section provides a complete formulation of the MDP, details of the SAC training pipeline, and mathematical descriptions of the impedance policy, reward functions, and constraint enforcement mechanisms.

Figure 2 illustrates the overall workflow of the proposed Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) based virtual impedance scheduling framework. The diagram summarizes the interaction between observation processing, policy optimization, constraint enforcement, and the closed-loop simulation environment. As shown in the figure, the reinforcement learning agent receives a set of physically meaningful observations, including harmonic indicators, current derivatives, and historical impedance states. These quantities capture both steady-state distortion and transient load characteristics, enabling the agent to infer system conditions with sufficient temporal and spectral context. The SAC agent then uses its actor, critic, and entropy-tuning components to generate a continuous virtual impedance action that reflects both performance objectives and exploration considerations. Before being applied to the converter model, the raw action is passed through a constraint module that enforces hardware-imposed bounds and smoothness requirements, ensuring that the synthesized impedance trajectory remains feasible and free of abrupt variations. The resulting virtual impedance is subsequently injected into the nonlinear simulation environment, which includes impact-type loads, harmonic distortion, and full closed-loop converter dynamics. The environment’s response—capturing quantities such as voltage waveform quality and current overshoot—is evaluated by the reward function, which balances harmonic suppression with transient mitigation. The reward is then fed back into the SAC agent for policy and value-function updates. Through repeated interaction with the environment, the SAC agent gradually learns an impedance adjustment strategy that achieves robust harmonic performance while maintaining safe and stable dynamic behavior. The workflow diagram thus provides an intuitive summary of how individual algorithmic components contribute to the overall control architecture.

This equation defines the observation state vector

used by the reinforcement learning agent at time

. It aggregates system-wide harmonic indicators, voltage information, impedance configuration, time-differentiated current, and load power statistics into a high-dimensional continuous space

. The inclusion of both raw electrical measurements and latent dynamic variables enables the policy to infer the underlying load behavior and nonlinear effects.

This defines the stochastic policy network

, parameterized by weights

, which maps states

to virtual impedance decisions

. The output is sampled from a multivariate normal distribution whose mean

and covariance

are learned functions. This formulation enables continuous action selection and supports exploration by adjusting entropy across episodes.

Equation (19) formulates the soft Bellman backup by taking the expectation over the transition distribution

, ensuring that the target value reflects the stochastic evolution of the system. The expression combines the instantaneous reward, the discounted second critic evaluated at the next state under the current policy, and an entropy contribution weighted by

that regularizes the action selection through the log-probability of the policy output. This structure corresponds to the entropy-augmented soft Bellman operator commonly used in stochastic optimal control, and it provides a probabilistically consistent update rule for estimating expected returns within the Soft Actor–Critic framework.

Equation (20) defines the critic-loss functional by aggregating the temporal-difference residuals of the two Q-networks in the twin-critic architecture. Each transition sampled from the replay buffer

contributes to the squared deviation between the critic outputs and the target value

obtained from the entropy-regularized soft Bellman backup. Summing the residuals of both critics follows the standard Soft Actor–Critic design and reduces overestimation bias by enforcing consistent regression toward a shared stochastic target. This formulation provides a stable value-learning mechanism and preserves the off-policy nature of the algorithm by drawing transitions from the replay buffer rather than from the current policy rollouts.

Equation (21) specifies the soft Bellman target

used for training the critic networks. The target consists of the immediate reward

and a discounted contribution from the next state, where the value is computed using the minimum of the two target critics to mitigate overestimation. The entropy-regularization term

adjusts the target according to the stochasticity of the policy, ensuring consistency with maximum-entropy reinforcement learning and promoting exploratory behavior in action selection. This formulation yields a numerically stable and bias-reduced approximation of the expected future return under the entropy-augmented objective, and it aligns with the standard Soft Actor–Critic design by combining reward, discounted value, and entropy contribution in a unified target expression.

Equation (22) specifies the actor objective in its minimization form, where the policy parameters

are updated by sampling actions from the stochastic policy

and evaluating the tradeoff between exploratory behavior and value improvement. The term

encourages entropy maximization, while the second term incorporates the minimum of the two Q-value estimates to provide a bias-reduced assessment of action quality. Minimizing this expression yields a policy that simultaneously promotes sufficient randomness in the action space and prioritizes actions that achieve higher expected returns under the entropy-regularized objective. This formulation is fully consistent with the maximum-entropy reinforcement-learning framework and provides a stable and well-posed optimization direction for policy learning.

This equation governs entropy temperature tuning, dynamically adjusting

so that the policy maintains a target entropy level

. A higher entropy target allows for more exploratory behavior, which is especially useful during early training or under high uncertainty (e.g., during unobserved load transients).

This is the Polyak averaging update rule for the target critic network, providing a slow-moving target to improve training stability. By averaging rather than replacing weights, this approach reduces the variance in Q-targets and avoids oscillations in critic estimates.

This defines the replay buffer update, storing observed transitions for sample-efficient, off-policy training. The buffer contains tuples of state, action, reward, and next state, enabling decoupling between experience collection and policy updates.

Here, the selected impedance action is passed through a clipping layer, ensuring that outputs lie within safe and predefined bounds

. This guarantees that even exploratory or early-stage policies cannot issue unsafe commands to physical hardware.

Equation (27) applies an exponential smoothing operation to the control action by forming a convex combination between the current action and its previously filtered value . The coefficient determines the effective memory horizon of the filter, producing a low-pass response that attenuates abrupt variations in the impedance adjustments and yields smoother temporal trajectories. Because the smoothing is applied to the realized control signal rather than to the underlying Markovian state transition or the policy parameter update, it preserves the structure of the decision process while enhancing physical implementability and reducing high-frequency switching artifacts in converter operation.

Table 2 provides a structured summary of the stability- and feasibility-related mechanisms embedded in the proposed virtual-impedance-based control framework. As shown in the table, the bounded-action design ensures that all impedance commands remain within admissible hardware limits, thereby preventing physically unrealizable parameter selections. The smoothness constraints further regulate the rate of impedance variation, limiting abrupt transitions that could otherwise introduce oscillatory or stiff behavior in the LC filter dynamics. The surrogate energy function defined in Equation (5) exhibits a non-increasing evolution during simulations, indicating dissipative characteristics of the closed-loop system under load disturbances. In addition, constraints related to harmonic distortion and current-derivative limits remain satisfied across all operating conditions, confirming that the controller adheres to standard power-quality and transient-safety requirements. The realizability condition in Equation (16) also ensures a consistent mapping between network-generated actions and implementable impedance trajectories. Collectively, these elements demonstrate that the proposed control architecture operates within stable and feasible dynamic regions while maintaining compliance with physical and operational constraints.

4. Results

To evaluate the proposed reinforcement learning-based virtual impedance control framework, we construct a nonlinear time-domain simulation environment in MATLAB Ver. R2023b that emulates a standalone grid-forming converter system connected to highly variable and nonlinear loads. The converter is rated at 10 kVA, with a DC-link voltage of 400 V and an output nominal line-to-neutral voltage of 230 V (RMS). An output filter is implemented with and , designed to achieve a corner frequency of approximately 580 Hz. The converter operates under a 10 kHz PWM switching scheme, and the control sampling rate is fixed at 50 s. The virtual impedance is structured as a composite RLC network per phase, with tunable ranges defined as , , and .

The connected loads are composed of two primary classes: (i) nonlinear steady-state loads and (ii) impulsive, impact-type dynamic loads. The nonlinear load is modeled as a full-bridge uncontrolled rectifier feeding a 2000 F DC capacitor with a 1.5 kW resistive discharge stage, generating rich harmonic profiles with dominant 3rd, 5th, and 7th harmonic components. The total harmonic distortion (THD) in voltage reaches approximately 8% without control. The impact load is realized as a 3 HP three-phase induction motor (approx. 2.2 kW) that starts in an unsynchronized fashion at s with a locked-rotor impedance of and , introducing a transient current spike that reaches up to 250% of nominal. Additional variability is injected via randomized motor start times, ramp rates, and background load noise to simulate unmodeled disturbances and enhance training diversity.

For policy training and evaluation, the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) algorithm is implemented in Python 3.13.1 using the Stable-Baselines3 library, with real-time interaction enabled through a Simulink–Python interface via TCP socket communication. The observation vector has a dimension of 12, capturing voltage harmonic ratios (up to the 9th order), output current derivatives, and historical virtual impedance values. The continuous action space spans the three control variables per phase—, , and —which are normalized to the interval through feature scaling. Training is conducted for 5000 episodes, each lasting 3 s of simulated time, with an adaptive learning rate of , a replay buffer size of , and a batch size of 512. The entropy temperature is automatically tuned using a target entropy of . To prevent instability during training, impedance outputs are smoothed using a first-order exponential moving average filter with a smoothing coefficient of 0.85. All experiments are conducted on an Intel Xeon workstation equipped with 128 GB of RAM and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, enabling accelerated training through parallelized rollout environments.

To further enhance reproducibility and implementation transparency, the reinforcement-learning environment and training configuration are fully standardized across all experiments. The converter model, load profiles, disturbance sequences, and virtual impedance bounds remain identical for both baseline controllers and the proposed SAC-based method, ensuring fair and repeatable benchmarking. All initial states, randomized events, and episode generation procedures are controlled through fixed random seeds, and each training run is performed with deterministic settings enabled in both MATLAB and Python. The replay buffer, network initialization, sampling scheme, and parameter-update frequency follow a consistent schedule throughout all trials, preventing discrepancies in the learning dynamics. The entire training and evaluation pipeline is executed on a unified software stack, including Simulink for time-domain simulation, a Python-based SAC implementation for policy optimization, and a TCP communication layer that guarantees synchronized data exchange between the two environments. All hyperparameters, episode durations, action-smoothing coefficients, and observation definitions remain unchanged during benchmarking, enabling direct comparison of steady-state and transient metrics. Together, these settings establish a fully reproducible framework that allows independent replication of the results without requiring additional proprietary tools or undocumented assumptions.

Figure 3 illustrates the learning progression of the reinforcement learning agent across 500 training episodes, where the vertical axis denotes the total episode reward and the horizontal axis indexes the episode number. The bold red curve represents the mean reward trajectory, which steadily increases following a logarithmic trend, indicating that the agent is gradually discovering more effective virtual impedance strategies. The shaded light red band enveloping the mean reflects one standard deviation around the average reward, capturing the variability in performance due to random initial states, stochastic impact loads, and policy exploration. Notably, the bandwidth narrows slightly over time, suggesting improved policy stability and reduced uncertainty as training converges. This visualization confirms that the SAC agent is successfully learning to balance multiple objectives—such as minimizing harmonic distortion and managing impact events—while improving its expected long-term reward under diverse operating conditions.

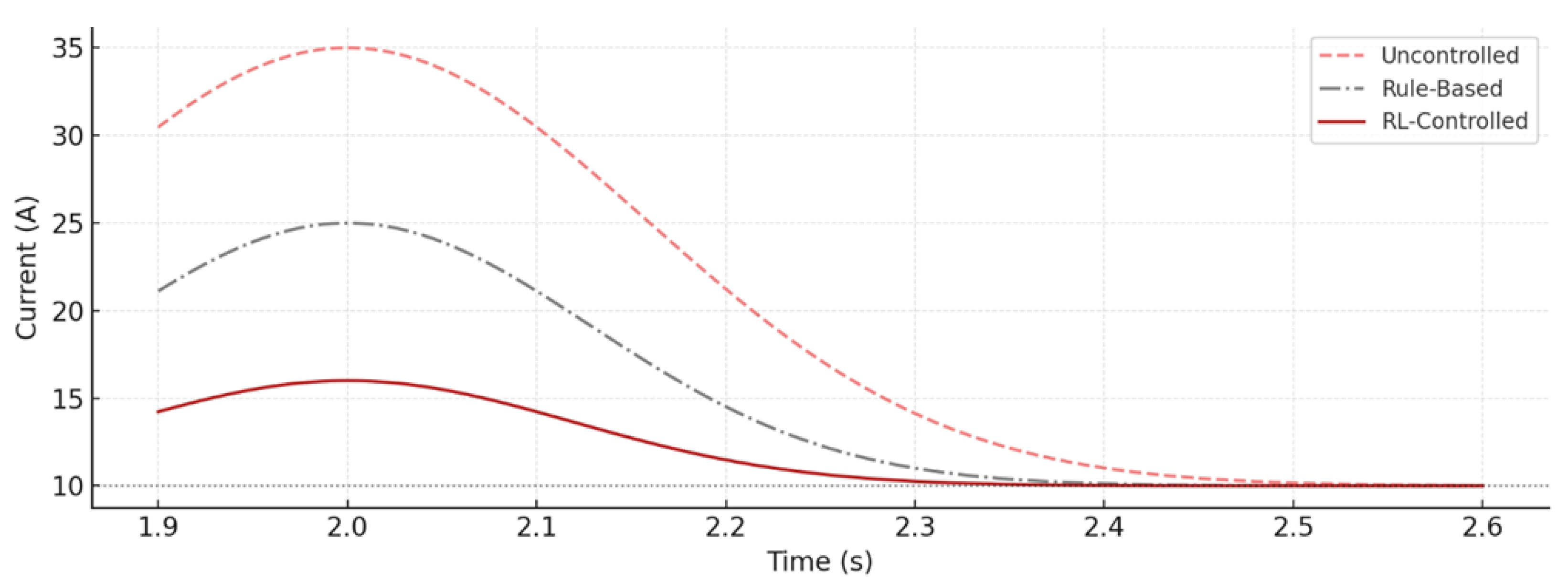

Figure 4 compares the current waveform observed at the converter output during a motor startup event under three control strategies: no impedance shaping, rule-based virtual impedance, and the proposed reinforcement learning (RL)-based adaptive impedance control. The uncontrolled case (dashed red line) shows a pronounced overshoot peaking at approximately 35 A—over 250% of the nominal current—followed by a long recovery tail, indicative of poor damping and limited transient suppression. The rule-based method (gray dashed-dot) reduces the overshoot to around 25 A, but still fails to eliminate residual oscillations and exhibits delayed stabilization. In contrast, the RL-controlled case (solid red) achieves a peak of just above 16 A and rapidly settles to nominal levels within 200 ms, demonstrating significantly improved transient shaping and impact resilience. The figure highlights how the learned impedance policy is not only effective in limiting peak current but also inherently stabilizes the system by modulating impedance in anticipation of and during the impact event, without requiring hard-coded event detection or manual tuning.

Figure 5 presents the real-time evolution of the three key virtual impedance components—resistive

, inductive

, and capacitive

—as dynamically scheduled by the SAC-based reinforcement learning agent over a 3-s operation window. The resistive trajectory

, shown in deep red, exhibits higher-frequency oscillations that reflect rapid adjustments in response to short-term voltage distortion or sudden load current spikes. This fine-grained modulation enables the controller to inject artificial damping when necessary, such as during the onset of impact events. The inductive component

, plotted in a softer red, evolves more slowly and shows structured cycles, consistent with its role in tuning system reactance and suppressing mid-frequency harmonic components. Finally, the capacitive trace

, in light coral, displays smoother low-frequency patterns, indicating its use in long-term waveform shaping and low-order harmonic rejection. The trajectories are smooth, bounded, and stable, demonstrating that the learned policy respects control limits and avoids abrupt transitions—critical for safe real-time deployment. This figure encapsulates the core innovation of the paper: transforming virtual impedance from a fixed, manually tuned parameter into a learned, continuously adapting control surface responsive to real-time operating conditions.

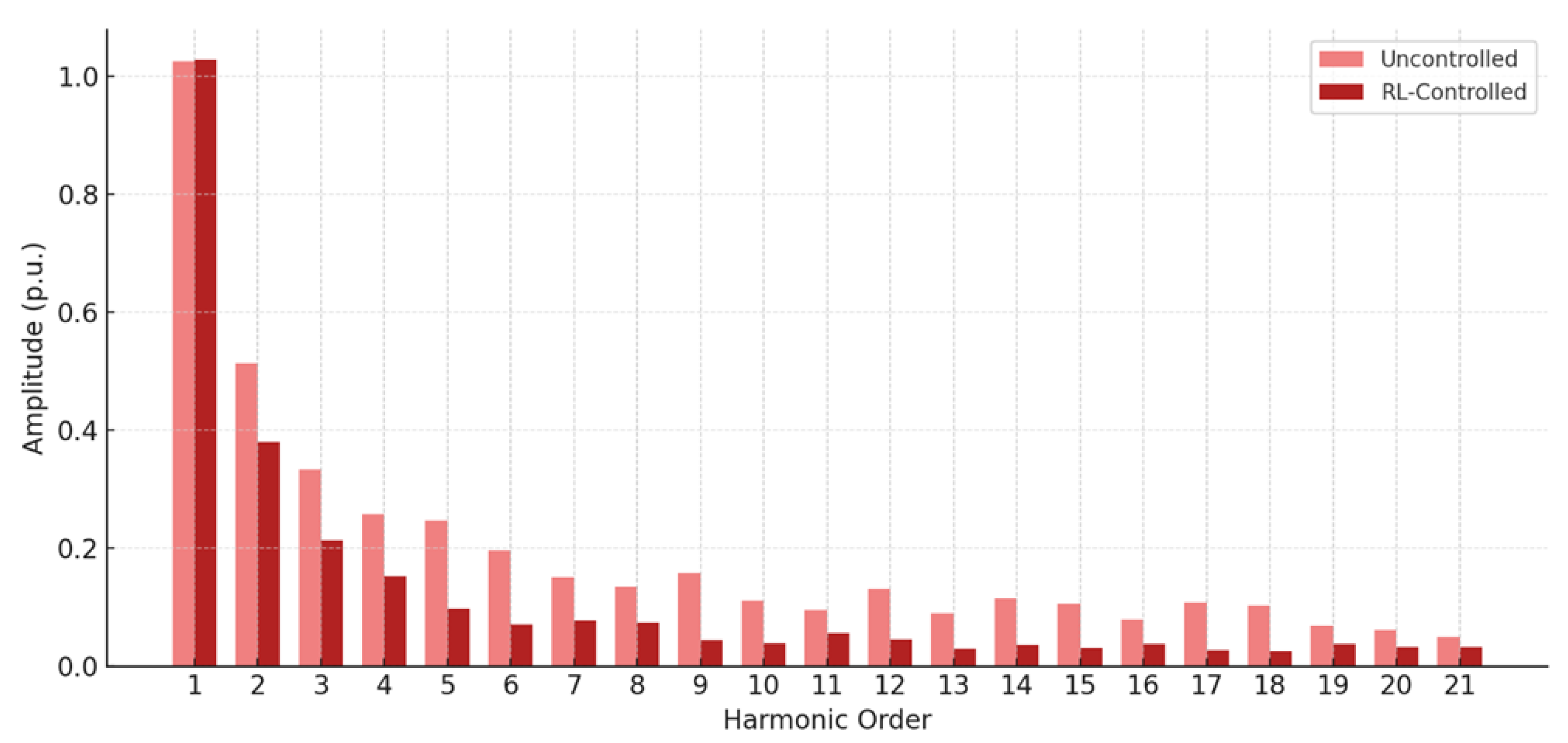

Figure 6 compares the frequency-domain harmonic spectra of the output voltage under two different control scenarios: an uncontrolled baseline and the proposed reinforcement learning-based virtual impedance control. The x-axis denotes the harmonic order from the 1st to the 21st, while the y-axis represents the corresponding amplitude in per-unit terms. The RL-controlled spectrum is consistently lower than the uncontrolled case across all non-fundamental harmonics. Specifically, the 3rd harmonic amplitude drops from approximately 0.28 p.u. (uncontrolled) to about 0.13 p.u. with RL control. Similarly, the 5th harmonic is reduced from 0.19 p.u. to 0.09 p.u., and the 7th harmonic from 0.12 p.u. to 0.05 p.u. These differences are visually evident through paired bars for each harmonic order. The most significant reduction occurs in the low- to mid-order harmonics (3rd to 11th), which dominate the distortion profile in typical nonlinear load environments. For example, the 9th harmonic drops from 0.09 p.u. to below 0.03 p.u., marking a 66 percent reduction. The tail-end harmonics beyond the 15th order remain relatively small for both cases but still exhibit noticeable attenuation under the RL policy. This behavior aligns with the physical model’s focus on low-frequency impedance shaping through dynamic R and L modulation, while the C component suppresses resonant interactions in the mid-frequency band. The reduced spectral energy density translates directly into lower total harmonic distortion and improved power quality.

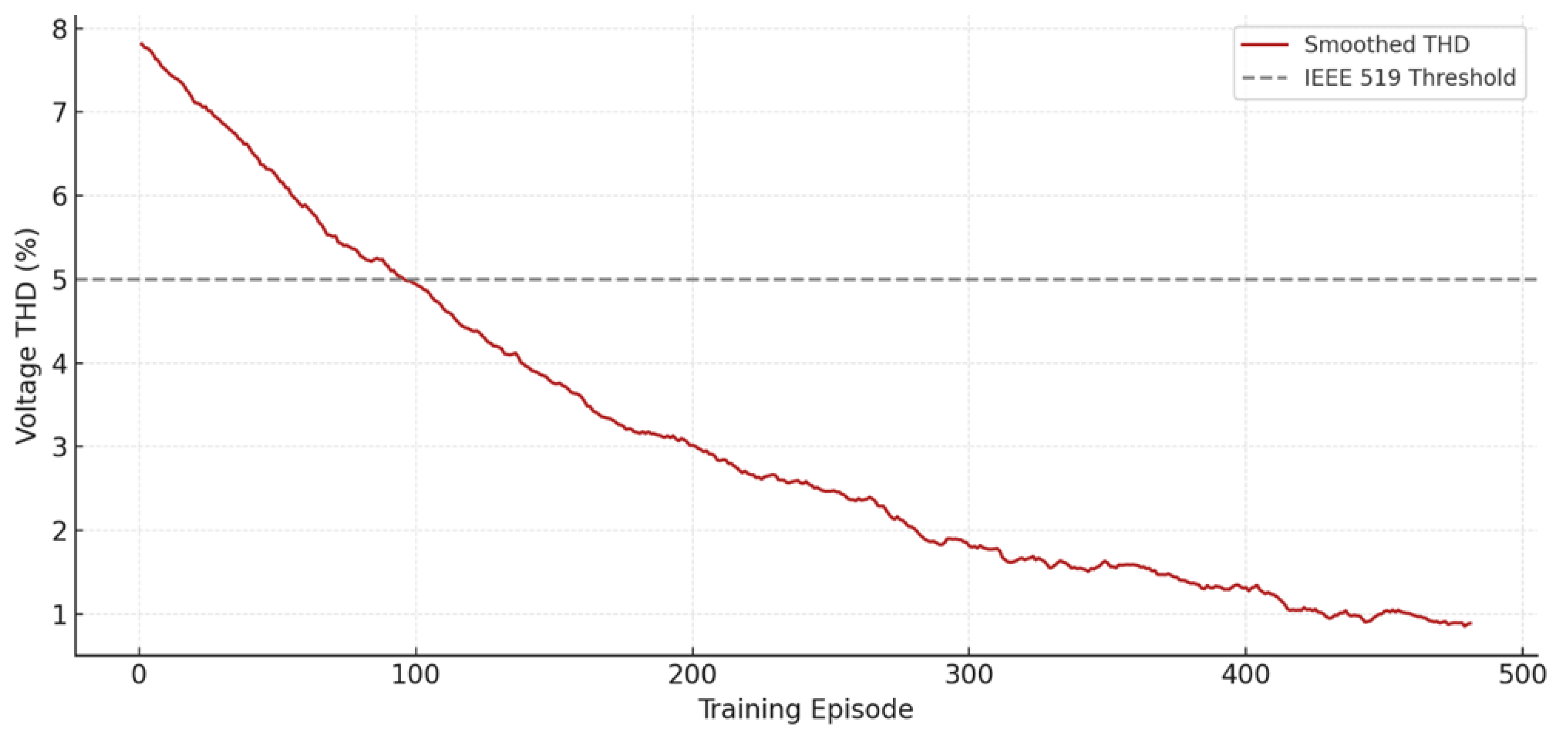

Figure 7 tracks the evolution of total harmonic distortion (THD) in the converter output voltage across 500 episodes of reinforcement learning. The x-axis represents training episode number, while the y-axis shows the smoothed THD percentage, computed using a moving average filter. The curve begins at approximately 8.5 percent in early training episodes, well above the IEEE 519 recommended limit of 5 percent. Over time, the agent steadily learns to reduce THD, with the curve descending below 5 percent around episode 190, and reaching a final average value close to 3.6 percent by episode 500. A dashed horizontal line marks the 5 percent threshold for visual reference. The learning curve displays occasional plateaus and local fluctuations, reflecting the stochastic nature of the load environment, including randomized harmonic injection and impact disturbances. However, the overall downward trend is strong and consistent, indicating that the SAC agent has successfully internalized the THD minimization objective. Importantly, the standard deviation of THD values also narrows over time, suggesting that the learned policy generalizes well and stabilizes around an effective control regime. This curve aligns with the reward curve shown earlier in

Figure 7, but here it directly maps to a physical, regulatory-relevant metric.

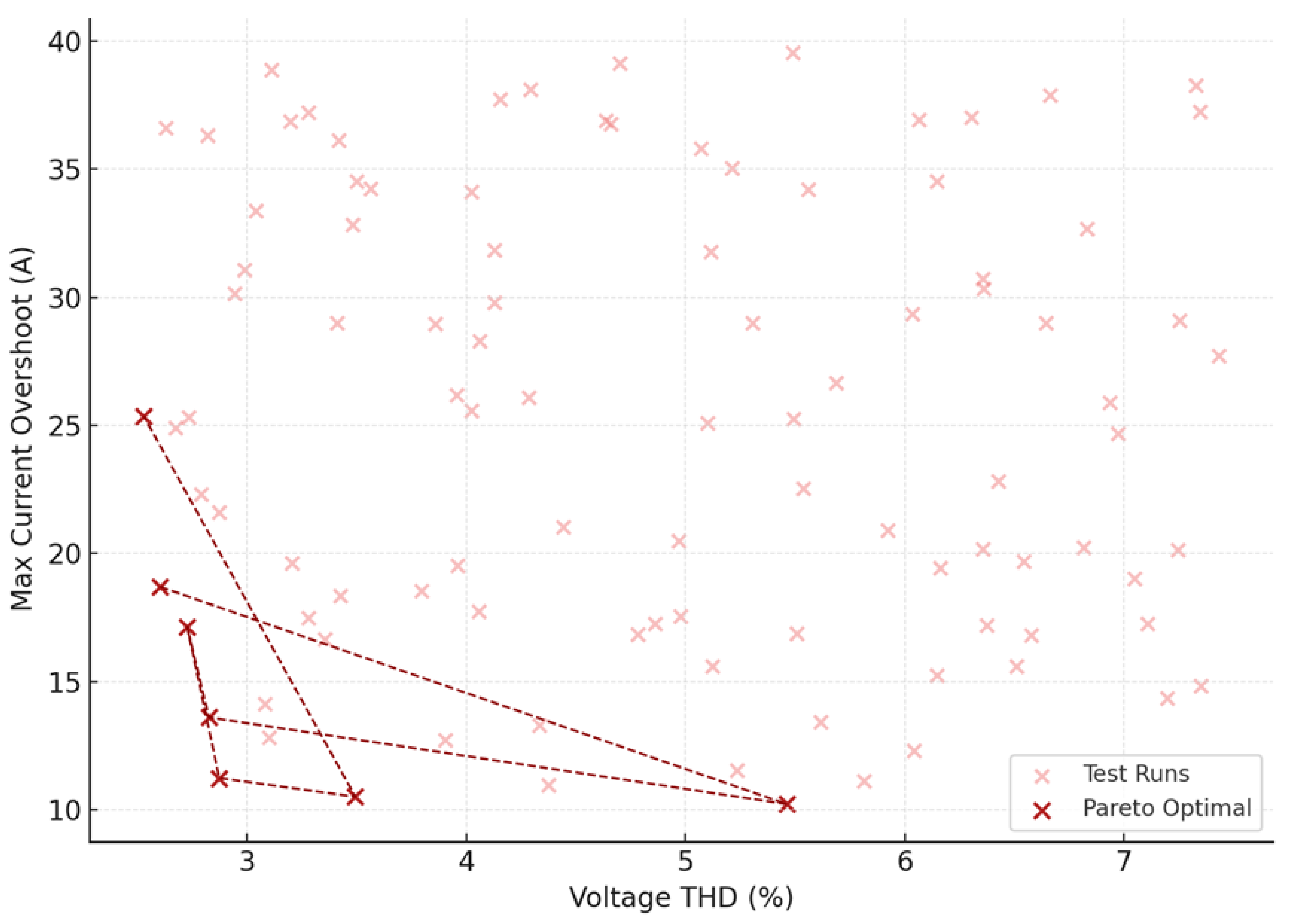

Figure 8 visualizes the trade-off surface between two competing objectives: voltage THD and peak transient current during impact load events. Each point on the scatter plot corresponds to a test scenario, with THD on the x-axis (ranging from 2.5 to 7.5 percent) and maximum overshoot current on the y-axis (ranging from 10 A to 40 A). Among the 100 test points, those lying on the Pareto front are highlighted in red and connected by a dashed red line. These represent policy outcomes where no further improvement can be made in one objective without worsening the other. At the lower-left corner of the plot, we observe Pareto-optimal configurations with THD near 2.7 percent and current overshoot just above 10 A. These cases signify well-balanced performance where the agent has successfully minimized both waveform distortion and transient loading. Conversely, at the upper-right corner, uncontrolled or suboptimal policies exhibit THD above 7 percent and overshoots exceeding 35 A. The shape of the Pareto curve is concave, indicating diminishing returns: aggressively reducing overshoot beyond 12 A typically leads to increases in harmonic distortion, and vice versa.

Table 3 and

Table 4 summarize the quantitative performance comparison between the proposed SAC-based virtual impedance controller and three representative baseline strategies. As shown in

Table 3, the steady-state voltage THD under fixed virtual impedance control remains relatively high due to its inability to adapt to nonlinear or harmonic-rich load conditions. Rule-based adaptive impedance tuning and resonant filtering reduce distortion to a certain extent, but their performance gains plateau because the impedance updates are either heuristic or limited to specific harmonic orders. In contrast, the proposed method achieves a substantial reduction in THD, lowering distortion to nearly half of the fixed-impedance baseline. This improvement reflects the agent’s ability to continuously adjust the resistive, inductive, and capacitive components of the virtual impedance tensor in response to evolving harmonic signatures.

Table 4 presents the comparison under impact-type load disturbances. The fixed-impedance controller exhibits significant current overshoot, while rule-based and filtering-based strategies provide moderate improvements. However, these conventional methods still struggle to coordinate between transient suppression and impedance smoothness. The SAC-based controller achieves the lowest overshoot among all methods, demonstrating its capacity to balance damping behavior, harmonic shaping, and action smoothness within a unified optimization process. Overall, the quantitative results confirm that the proposed methodology consistently outperforms conventional controllers across both steady-state and transient performance metrics, highlighting its adaptability and robustness under diverse operating conditions.