Renewable Energy Integration in Sustainable Transport: A Review of Emerging Propulsion Technologies and Energy Transition Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Electric and Hybrid Vehicles—Reducing Fossil Fuel Consumption

3.1. The Development of the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Market

3.2. Comparison of Energy Consumption Between Electric Vehicles and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles

3.3. Environmental and Energy Benefits

3.4. Technological and Infrastructure Challenges

3.5. The Role of Maritime Transport

4. Hydrogen and Biofuels as Alternative Energy Carriers: Potential and Implementation Barriers

4.1. The Potential of Hydrogen as the Fuel of the Future

4.1.1. How FCEV Technology Works and Its Advantages

4.1.2. Technological, Economic, and Infrastructure Barriers

4.1.3. Hydrogen Infrastructure and Safety of Use

4.2. Biofuels in the Energy Transition Transport

4.2.1. Classification of Biofuels (I–IV Generation)

4.2.2. Emission Reduction Potential and Use in Existing Infrastructure

4.2.3. Technological, Environmental, and Social Constraints

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen and Biofuels—Selected Case Studies

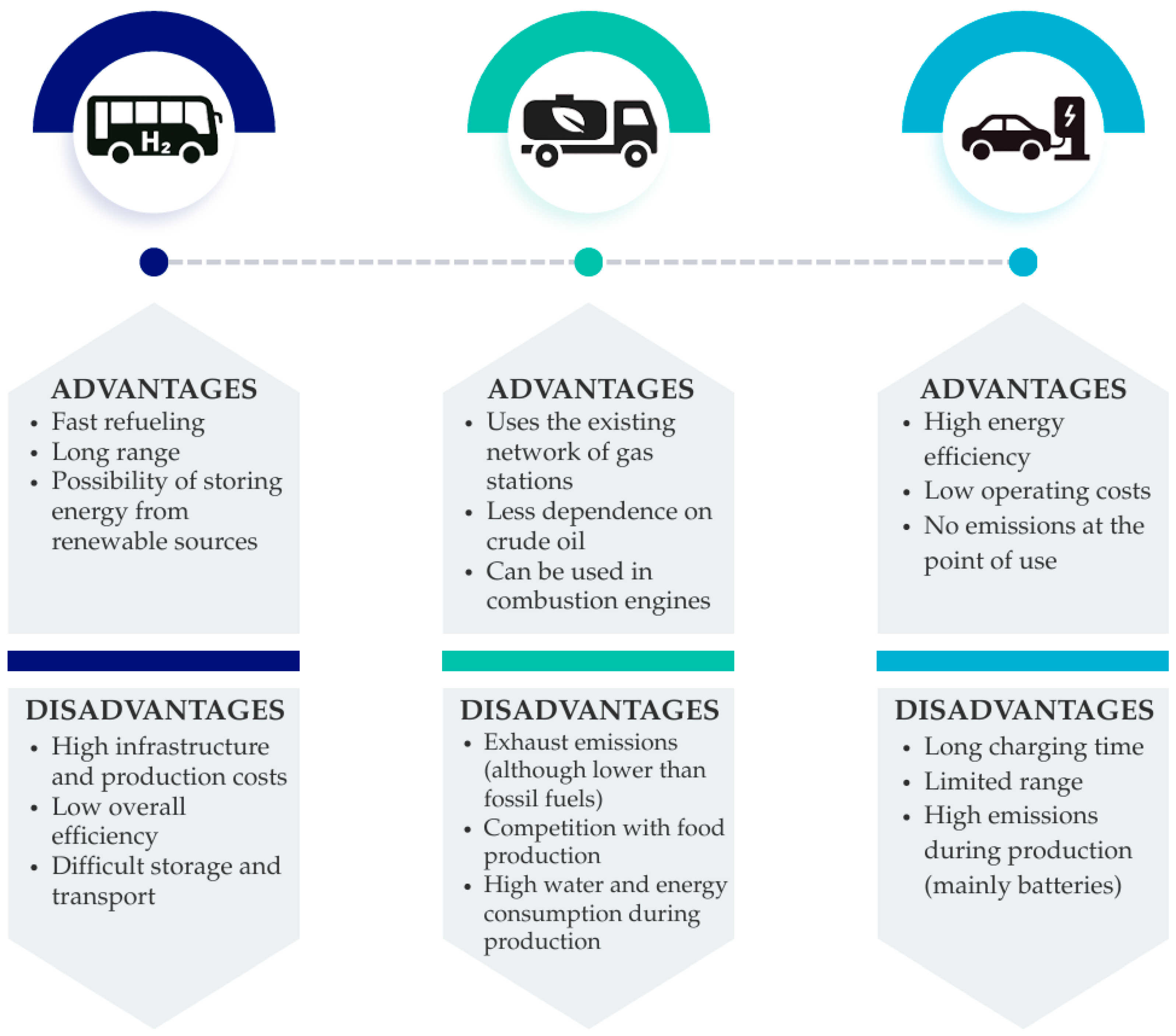

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Propulsion Technologies—Managerial Perspective

5. The Impact of Renewable Energy Sources in the Energy Mix on the Real Environmental Performance of Vehicles

6. Climate Regulations in the Transport Sector and Legal Framework for Propulsion Technologies

6.1. Global Regulations (UN and International Agreements)

6.2. European Union Law

6.3. Polish Law

6.4. Summary of the Role of Law

6.5. Specific Legal Regulations on Propulsion Types

7. Analysis and Discussion of Contemporary Trends in Propulsion Technology Development

7.1. Characteristics and Energy Efficiency of Propulsion Technologies

7.2. Emissions and the Impact of the Energy Mix on the Carbon Balance

7.3. Perspectives on the Development of Propulsion Technologies

7.4. Biofuels as a Transitional Solution in the Decarbonization Process

8. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFIR | Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation |

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| CCS | Combined Charging System |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CNG | Compressed Natural Gas |

| COP | Conference of the Parties (UNFCCC) |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| E-Fuels | Synthetic Electrofuels |

| EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| ETS | Emissions Trading System |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FAME | Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (Biodiesel) |

| FCEV | Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| HRS | Hydrogen Refueling Station |

| HVO | Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IPCEI | Important Project of Common European Interest |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LNG | Liquefied Natural Gas |

| NCW | National Indicative Target System (Poland) |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contributions |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| PEMFC | Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell |

| PEP2040 | Polish Energy Policy 2040 |

| PHEV | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| RED II/III | Renewable Energy Directive II/III |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| SAF | Sustainable Aviation Fuel |

| SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| SUV | Sport Utility Vehicle |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

References

- Kumbaroğlu, G.; Canaz, C.; Deason, J.; Shittu, E. Profitable Decarbonization through E-Mobility. Energies 2020, 13, 4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Transport in Europe. 2025. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-transport (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Tan, C.H.; Ong, M.Y.; Nomanbhay, S.M.; Shamsuddin, A.H.; Show, P.L. The Influence of COVID-19 on Global CO2 Emissions and Climate Change: A Perspective from Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, D.; Rau, H.; Härtling, J.W. Case Study: Assessing The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Potential for a More Climate-Friendly Work-Related Mobility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.M.; Forster, H.I.; Evans, M.J.; Gidden, M.J.; Jones, C.D.; Keller, C.A.; Lamboll, R.D.; Le Quéré, C.; Rogelj, J.; Rosen, D.; et al. Current and Future Global Climate Impacts Resulting from COVID-19. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Fischedick, M.; Shan, Y.; Hubacek, K. Implications of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Surface Passenger Mobility and Related CO2 Emission Changes in Europe. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieszek, M.; Mateichyk, V.; Dobrzanska, M.; Dobrzanski, P.; Weigang, G. The Impact of the Pandemic on Vehicle Traffic and Roadside Environmental Pollution: Rzeszow City as a Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Huang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wu, M.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Lombardi, G.V. A Study on Near Real-Time Carbon Emission of Roads in Urban Agglomeration of China to Improve Sustainable Development under the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Park, S.; Jang, K. Rebound Effect or Induced Demand? Analyzing the Compound Dual Effects on VMT in the U.S. Sustainability 2017, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzollahi, M.; Pineau, P.-O.; Rafizadeh, N. Drivers of Driving: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.J.; Hariram, N.P.; Maity, R.; Ghazali, M.F.; Kumarasamy, S. Sustainable Vehicles for Decarbonizing the Transport Sector: A Comparison of Biofuel, Electric, Fuel Cell and Solar-Powered Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, A.; Janczura, J.; Jurkowski, S.; Zacłona, T.; Gronba-Chyła, A.; Kwaśnicki, P. The Analysis of Exhaust Composition Serves as the Foundation of Sustainable Road Transport Development in the Context of Meeting Emission Standards. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, A.; Plata, K. The Efficiency of Vehicle Fleet Management Using the Example of a Company Transporting a T60 Medium. J. Eng. Energy Inform. 2024, 1, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Roumeliotis, I.; Zolotas, A. Sustainable Aviation Electrification: A Comprehensive Review of Electric Propulsion System Architectures, Energy Management, and Control. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejski, M.; Michalska-Pozoga, I. Battery Energy Storage Systems in Ships’ Hybrid/Electric Propulsion Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunanan, C.; Tran, M.-K.; Lee, Y.; Kwok, S.; Leung, V.; Fowler, M. A Review of Heavy-Duty Vehicle Powertrain Technologies: Diesel Engine Vehicles, Battery Electric Vehicles, and Hydrogen Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles. Clean Technol. 2021, 3, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquim, R.F.; Mady, C.E.K. Performance and Efficiency Trade-Offs in Brazilian Passenger Vehicle Fleet. Energies 2022, 15, 5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, P.; Dargay, J.; Hanly, M. Elasticities of Road Traffic and Fuel Consumption with Respect to Price and Income: A Review. Transp. Rev. 2004, 24, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.; Sousa, N.; Coutinho-Rodrigues, J.; Natividade-Jesus, E. Challenges Ahead for Sustainable Cities: An Urban Form and Transport System Review. Energies 2024, 17, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Laying the Foundations for Greener Transport: TERM 2011—Transport Indicators Tracking Progress towards Environmental Targets in Europe; EEA Report 7/2011; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Trends and Projections in Europe 2024; EEA Report 11/2024; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Rail and Waterborne—Best for Low-Carbon Motorised Transport; Briefing No. 01/2021; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Sustainability of Europe’s Mobility Systems; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/sustainability-of-europes-mobility-systems (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Vinci, G.; Savastano, M.; Amici, A.; Ruggeri, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production from Different Biomasses. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wright, L.A. A Comparative Review of Alternative Fuels for the Maritime Sector: Economic, Technology, and Policy Challenges for Clean Energy Implementation. World 2021, 2, 456–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Freight Transport Activity; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/sustainability-of-europes-mobility-systems/freight-transport-activity (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Smit, R.; Ayala, A.; Kadijk, G.; Buekenhoudt, P. Excess Pollution from Vehicles—A Review and Outlook on Emission Controls, Testing, Malfunctions, Tampering, and Cheating. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walnum, H.J.; Aall, C.; Løkke, S. Can Rebound Effects Explain Why Sustainable Mobility Has Not Been Achieved? Sustainability 2014, 6, 9510–9537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, T.; Sander, H. Decarbonizing Transport in the European Union: Emission Performance Standards and the Perspectives for a European Green Deal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, A.; Zacłona, T.; Cembruch-Nowakowski, M.; Janczura, J.; Pietrucha, I.; Herbut, P.; Kotowski, T.; Oleksy-Gębczyk, A.; Guzdek, S.; Majkrzak, A. Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors Toward Energy Saving and Transportation. Energies 2025, 18, 6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronka, A.; Raźniewska, M.; Rudnicka, A.; Kędzia, G. Institutional Stimulants for Low-Carbon Transport: The Case of the Fleet Electrification in the Polish Logistics Industry. Energies 2025, 18, 6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, G.; Pode, G.; Diouf, B.; Pode, R. Sustainable Decarbonization of Road Transport: Policies, Current Status, and Challenges of Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koengkan, M.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Teixeira, M.; Kazemzadeh, E.; Auza, A.; Dehdar, F.; Osmani, F. The Capacity of Battery-Electric and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles to Mitigate CO2 Emissions: Macroeconomic Evidence from European Union Countries. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajper, S.Z.; Albrecht, J. Prospects of Electric Vehicles in the Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yengil Bülbül, B.; Baydar, M.B. Decarbonizing Transportation: Cross-Country Evidence on Electric Vehicle Sales and Carbon Dioxide Emissions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Finance Platform. Finance and Transport: Financing Climate Action for Transportation. Green Finance Platform. 2020. Available online: https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/Finance%20and%20Transport.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Basmantra, I.N.; Santiarsa, N.K.S.; Widodo, R.D.; Mimaki, C.A. How the Adoption of EVs in Developing Countries Can Be Effective: Indonesia’s Case. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, E.S.; Amegah, A.K.; Mwebaze, E.; Ssematimba, J.; Bainomugisha, E. A Land Use Regression Model Using Machine Learning and Locally Developed Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors in Uganda. Environ. Res. 2021, 199, 111352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofoezie, E.I.; Eludoyin, A.O.; Udeh, E.B.; Onanuga, M.Y.; Salami, O.O.; Adebayo, A.A. Climate, Urbanization and Environmental Pollution in West Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). New UN Report Details Environmental Impacts of Export of Used Vehicles to Developing World; Press Release. 26 October 2020. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/new-un-report-details-environmental-impacts-export-used-vehicles (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Abera, A.; Mattisson, K.; Eriksson, A.; Ahlberg, E.; Sahilu, G.; Mengistie, B.; Bayih, A.G.; Aseffaa, A.; Malmqvist, E.; Isaxon, C. Air Pollution Measurements and Land-Use Regression in Urban Sub-Saharan Africa Using Low-Cost Sensors—Possibilities and Pitfalls. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, G.; Lutzemberger, G.; Ferrari, L. Renewable Electricity for Decarbonisation of Road Transport: Batteries or E-Fuels? Batteries 2023, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Reinoso, E.V.; Anacleto-Fernández, M.; Utreras-Alomoto, J.; Carranco-Quiñonez, C.; Mata, C. Comparative Study of Fuel and Greenhouse Gas Consumption of a Hybrid Vehicle Compared to Spark Ignition Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małek, A. Low-Emission Hydrogen for Transport—A Technology Overview from Hydrogen Production to Its Use to Power Vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohannadi, A.A.; Ertogral, K.; Erkoc, M. Alternative Fuels in Sustainable Logistics—Applications, Challenges, and Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Khalid, M.; Ullah, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Aljaidi, M.; Malik, F.A.; Manzoor, U. Electric Vehicle Charging Modes, Technologies and Applications of Smart Charging. Energies 2022, 15, 9471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.K.; Zhang, J.; Balasubramanian, R. Recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries for a sustainable future: Recent advancements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 5552–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Luo, S.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L. Fundamentals of the recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 11967–12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.N.; Abdul-Kader, W. Repurposing Second-Life EV Batteries to Advance Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Review. Batteries 2024, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoade, I.A.; Longe, O.M. A Comprehensive Review on Smart Electromobility Charging Infrastructure. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, E.E. Primary Energy Use and Environmental Effects of Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Le, P.A. A review of construction and sustainable recycling strategies of lithium-ion batteries across electric vehicle platforms. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 35687–35725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phogat, P.; Dey, S. Powering the sustainable future: A review of emerging battery technologies and their environmental impact. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 3266–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, P.M.; Dyer, C.; Subramanian, V. Lithium-ion battery recycling—A review of the material supply and policy infrastructure. NPG Asia Mater. 2024, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, A.D.; Grammatikos, S.A.; Ursan, G.A.; Aradoaei, S.; Summerscales, J.; Ciobanu, R.C.; Schreiner, C.M. Recovery of electronic wastes as fillers for electromagnetic shielding in building components: An LCA study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iclodean, C.; Varga, B.; Burnete, N.; Cimerdean, D.; Jurchiș, B. Comparison of different battery types for electric vehicles. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 252, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny (PIE). Jak Wspierać Elektromobilność? Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; Available online: https://pie.net.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/PIE-Raport_Elektromobilnosc.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Nealer, R.; Reichmuth, D.; Anair, D. Cleaner Cars from Cradle to Grave: How Electric Cars Beat Gasoline Cars on Lifetime Global Warming Emissions; Union of Concerned Scientists: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.R.; Singh, B.; Majeau-Bettez, G.; Strømman, A.H. Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Electric Vehicles. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). ICCT E-Mobility Transition Ranking Shows Tesla and BYD in Lead; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.electrive.com/2023/05/31/icct-e-mobility-transition-ranking-shows-tesla-and-byd-in-lead (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny (PIE). Najpopularniejszy Sposób Liczenia Kosztów Wytwarzania Energii Nie Uwzględnia Systemowych Wyzwań Rozwoju OZE; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; Available online: https://pie.net.pl/najpopularniejszy-sposob-liczenia-kosztow-wytwarzania-energii-nie-uwzglednia-systemowych-wyzwan-rozwoju-oze/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Bieker, G. A Global Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Combustion Engine and Electric Passenger Cars; International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT): Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Global-LCA-passenger-cars-jul2021_0.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Puma-Benavides, D.S.; Cevallos-Carvajal, A.S.; Masaquiza-Yanzapanta, A.G.; Quinga-Morales, M.I.; Moreno-Pallares, R.R.; Usca-Gomez, H.G.; Murillo, F.A. Comparative Analysis of Energy Consumption between Electric Vehicles and Combustion Engine Vehicles in High-Altitude Urban Traffic. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poupinha, C.; Dornoff, J. The Bigger the Better? How Battery Size Affects Real-World Energy Consumption, Cost of Ownership, and Life-Cycle Emissions of Electric Vehicles; International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT): Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ID-80-%E2%80%93-BEVs-size-Report-A4-70138-v8.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Fuel Economy in Major Car Markets: Technology and Policy Drivers 2005–2017; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/66965fb0-87c9-4bc7-990d-a509a1646956/Fuel_Economy_in_Major_Car_Markets.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Electricity 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/7c671ef6-2947-4e87-beea-af0e1288e1d7/Electricity2025.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Auto$mart. Learn the Facts: Fuel Consumption and CO2; Natural Resources Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/oee/pdf/transportation/fuel-efficient-technologies/autosmart_factsheet_6_e.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Global Petrol Prices. Electricity Prices. 2025. Available online: https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/electricity_prices/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). End-Use Prices Data Explorer. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/end-use-prices-data-explorer (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Wiatros-Motyka, M.; Fulghum, N.; Jones, D. World Passes 30% Renewable Electricity Milestone: Global Electricity Review 2024; Ember: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/05/Report-Global-Electricity-Review-2024.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Edwards, R.; Larivé, J.-F.; Béziat, J.-C. Well-to-Wheels Analysis of Future Automotive Fuels and Powertrains in the European Context. European Commission Joint Research Centre, Institute for Energy; CONCAWE. Renault/EUCAR. 2011. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC65998/eur%2024952%20en%20c.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Air Quality Guidelines: Global Update 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Electric Vehicle Myths; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/electric-vehicle-myths (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Keck School of Medicine of USC. Study Links Adoption of Electric Vehicles with Less Air Pollution and Improved Health; Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://keck.usc.edu/news/study-links-adoption-of-electric-vehicles-with-less-air-pollution-and-improved-health/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Transport & Environment (T & E). The State of European Transport 2024; Transport & Environment: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://www.transportenvironment.org/uploads/files/TE_SoT_2024_report_2024-04-29-155117_davx.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Rimpas, D.; Barkas, D.E.; Orfanos, V.A.; Christakis, I. Decarbonizing the Transportation Sector: A Review on the Role of Electric Vehicles Towards the European Green Deal for the New Emission Standards. Air 2025, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, D. Critical Elements of Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G); National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2017. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy17osti/69017.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Mirletz, B.; Vimmerstedt, L.; Akar, S.; Avery, G.; Stright, D.; Akindipe, D.; Augustine, C.; Beiter, P.; Cohen, S.; Cole, W.; et al. Annual Technology Baseline: The 2023 Electricity Update; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2023. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy23osti/86419.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Radović, U. Wpływ samochodów elektrycznych na polski system elektroenergetyczny, emisję CO2 oraz inne zanieczyszczenia powietrza. Zesz. Nauk. Inst. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. I Energią Pol. Akad. Nauk. 2018, 104, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodacki, D.; Polaszczyk, J. Emisyjność dwutlenku węgla przez samochody elektryczne w kontekście strategicznych celów rozwoju elektromobilności w Polsce i Holandii. Polityka Energetyczna—Energy Policy J. 2018, 21, 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Seweryn, E. Efektywność Energetyczna Przez Rozwój Elektromobilności w Polsce. Portal Komunalny—Dodatek Specjalny Biuletyn EkoEdukacja 2017. Available online: https://portalkomunalny.pl/plus/artykul/efektywnosc-energetyczna-przez-rozwoj-elektromobilnosci-w-polsce/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Electric Vehicle Charging. In Global EV Outlook 2025; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025/electric-vehicle-charging (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- GridX. Europe’s EV Sales Faltered, but Infrastructure Soars. In European EV Charging Report 2025; GridX: Berlin, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.gridx.ai/resources/european-ev-charging-report-2025 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Bird & Bird. The Impact of EV Charging Infrastructure on the Global Energy Grid; Bird & Bird: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.twobirds.com/en/insights/2025/the-impact-of-ev-charging-infrastructure-on-the-global-energy-grid (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- BloombergNEF. Lithium-Ion Battery Pack Prices See Largest Drop Since 2017, Falling to $115 per Kilowatt-Hour; BloombergNEF: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://about.bnef.com/insights/commodities/lithium-ion-battery-pack-prices-see-largest-drop-since-2017-falling-to-115-per-kilowatt-hour-bloombergnef/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Harper, G.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E.; Driscoll, L.; Salter, P.; Stolkin, R.; Walton, A.; Christensen, P.; Heidrich, O.; Lambert, S.; et al. Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Nature 2019, 575, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroma, M.S.; Costa, D.; Philippot, M.; Cardellini, G.; Hosen, M.S.; Coosemans, T.; Messagie, M. Life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles: Implications of future electricity mix and different battery end-of-life management. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Mobility House. Implementing V2G; Knowledge Center, The Mobility House: Munich, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://mobilityhouse-energy.com/int_en/knowledge-center/article/implementing-v2g (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Air Pollution from Global Shipping, 2016–2023; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ID-332-%E2%80%93-Global-shipping_report_final.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Berre, L.L.; Temime-Roussel, B.; Lanzafame, G.M.; D’Anna, B.; Marchand, N.; Sauvage, S.; Dufresne, M.; Tinel, L.; Leonardis, T.; Ferreira de Brito, J.; et al. Measurement Report: In-Depth Characterization of Ship Emissions during Operations in the Mediterranean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 6575–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. PEM Fuel Cell Electrocatalysts and Catalyst Layers: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Dong, W.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, H.; He, G. Development of fuelling protocols for gaseous hydrogen vehicles: A key component for efficient and safe hydrogen mobility infrastructures. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenstadt, A.; Lutsey, N. Developing Hydrogen Fueling Infrastructure for Fuel Cell Vehicles: A Status Update; The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT): Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://theicct.org/publication/developing-hydrogen-fueling-infrastructure-for-fuel-cell-vehicles-a-status-update/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Hassan, Q.; Azzawi, I.D.J.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles: Opportunities and Challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üçok, M.D. Prospects for Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles to Decarbonize Road Transport. Discov. Sustain. 2023, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.M.H.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Production, Storage, and Transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Vairin, C.; von Jouanne, A.; Agamloh, E.; Yokochi, A. Review of Fuel-Cell Electric Vehicles. Energies 2024, 17, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, A.; Hosseini Dolatabadi, S.; Heidari, M.; Pinnarelli, A.; Mehdizadeh Khorrami, B.; Luo, Y.; Vizza, P.; Brusco, G. Progress in Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles and Up-and-Coming Technologies for Eco-Friendly Transportation: An International Assessment. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 3153–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, S. Perspectives on CO2-Free Hydrogen Production: Insights and Strategic Approaches. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 20033–20056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeq, A.M. Advances and Challenges in Hydrogen Energy: A Review. Chem. Eng. Process Tech. 2024, 9, 1087. Available online: https://www.jscimedcentral.com/public/assets/articles/chemicalengineering-9-1087.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Guerrero-Rodríguez, N.F.; De La Rosa-Leonardo, D.A.; Tapia-Marte, R.; Ramírez-Rivera, F.A.; Faxas-Guzmán, J.; Rey-Boué, A.B.; Reyes-Archundia, E. An Overview of the Efficiency and Long-Term Viability of Powered Hydrogen Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta-Déu, C. New Protocol for Hydrogen Refueling Station Operation. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pang, Y.; Xu, H.; Martínez, A.; Chen, K.S. PEM Fuel Cell and Electrolysis Cell Technologies and Hydrogen Infrastructure Development—A Review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 2288–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T. Green Energy Fuelling Stations in Road Transport: Poland in the European and Global Context. Energies 2025, 18, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Hydrogen Review 2023; IEA: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2023 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Hydrogen Europe. Clean Hydrogen Monitor 2022; Hydrogen Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://hydrogeneurope.eu/clean-hydrogen-monitor2022/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Kochanek, A.; Zacłona, T.; Szucki, M.; Bulanda, N. Agent Systems and GIS Integration in Requirements Analysis and Selection of Optimal Locations for Energy Infrastructure Facilities. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, A.; Generowicz, A.; Zacłona, T. The Role of Geographic Information Systems in Environmental Management and the Development of Renewable Energy Sources—A Review Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, A. The Usefulness of Public Geoportal Functions in Planning and Preliminary Environmental Assessment of Rural Areas. J. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 26, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, A.; Ciuła, J.; Generowicz, A.; Mitryasova, O.; Jasińska, A.; Jurkowski, S.; Kwaśnicki, P. The Analysis of Geospatial Factors Necessary for the Planning, Design, and Construction of Agricultural Biogas Plants in the Context of Sustainable Development. Energies 2024, 17, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, H.; Zhou, Y.; Rodríguez, F. Fuel-Cell Hydrogen Long-Haul Trucks in Europe: A Total Cost of Ownership Analysis; International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT): Berlin, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/eu-hvs-fuels-evs-fuel-cell-hdvs-europe-sep22.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Eurostat. Annual Full-Time Adjusted Salary in EU Grew in 2023; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20241107-1 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Pereira, R.; Monteiro, V.; Afonso, J.L.; Teixeira, J. Hydrogen Refueling Stations: A Review of the Technology Involved from Key Energy Consumption Processes to Related Energy Management Strategies. Energies 2024, 17, 4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.; Gilpin, G. Biofuels and Sustainable Transport: A Conceptual Discussion. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3129–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A.G. Developments and Issues in Renewable Ecofuels and Feedstocks. Energies 2024, 17, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Al Makishah, N.H.; Wen, Z.; Gupta, G.; Pandit, S.; Prasad, R. Recent Developments in Lignocellulosic Biofuels, a Renewable Source of Bioenergy. Fermentation 2022, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.K.; Sharma, A.; Soni, R. Microbial Enzyme Systems in the Production of Second Generation Bioethanol. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orliński, P.; Sikora, M.; Bednarski, M.; Gis, M. The Influence of Powering a Compression Ignition Engine with HVO Fuel on the Specific Emissions of Selected Toxic Exhaust Components. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tong, R.; Zhai, Q.; Lyu, G.; Li, Y. A Critical Review of Life Cycle Assessments on Bioenergy Technologies: Methodological Choices, Limitations, and Suggestions for Future Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Aron, N.S.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Show, P.L.; Chen, W.-H.; Nguyen, T.H.P. Sustainability of the Four Generations of Biofuels—A Review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 9266–9282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, J.; Mueller, M.; Pander, J.; Geist, J. Ecological Assessment of the World’s First Shaft Hydropower Plant. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, T.; Rajaeifar, M.A.; Kenny, A.; Hainsworth, C.; del Pino, V.; del Valle Inclán, Y.; Povoa, I.; Mendonça, P.; Brown, L.; Smallbon, A.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment of Microalgae-Derived Biodiesel. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Araby, R. Biofuel Production: Exploring Renewable Energy Solutions for a Greener Future. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2024, 17, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavelius, P.; Engelhart-Straub, S.; Mehlmer, N.; Lercher, J.; Awad, D.; Brück, T. The Potential of Biofuels from First to Fourth Generation. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Li, X.; Xu, T.; Dong, J.; Geng, Z.; Liu, J.; Ding, C.; Hu, J.; El ALAOUI, A.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Zero-Carbon and Carbon-Neutral Fuels: A Review of Combustion Products and Cytotoxicity. Energies 2023, 16, 6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, J.; Krzaczek, P.; Szyszlak-Bargłowicz, J.; Zając, G.; Koniuszy, A.; Hawrot-Paw, M.; Marcinkowska, W. Evaluation of Nitrogen Oxide (NO) and Particulate Matter (PM) Emissions from Waste Biodiesel Combustion. Energies 2024, 17, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell, E.; Salberg, H.; Salo, K. Measurements of Emissions to Air from a Marine Engine Fueled by Methanol. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2021, 20, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruczyński, S.; Ślęzak, M.; Gis, W.; Żółtowski, A.; Gis, M. Comparative Studies of Exhaust Emission from a Diesel Engine Fueled with Diesel Fuel and B100 Fuel. Combust. Engines 2017, 170, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Song, E.; Xu, C.; Ni, Z.; Yang, X.; Dong, Q. Analysis of Performance of Passive Pre-Chamber on a Lean-Burn Natural Gas Engine under Low Load. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtoranta, K.; Vesala, H.; Flygare, N.; Kuittinen, N.; Apilainen, A.-R. Measuring Methane Slip from LNG Engines with Different Devices. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuła, J.; Gaska, K.; Siedlarz, D.; Koval, V. Management of Sewage Sludge Energy Use with the Application of Bi-Functional Bioreactor as an Element of Pure Production in Industry. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 123, 01016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaska, K.; Generowicz, A.; Lobur, M.; Jaworski, N.; Ciuła, J.; Vovk, M. Advanced Algorithmic Model for Poly-Optimization of Biomass Fuel Production from Separate Combustible Fractions of Municipal Wastes as a Progress in Improving Energy Efficiency of Waste Utilization. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 122, 01004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuła, J.; Sobiecka, E.; Zacłona, T.; Rydwańska, P.; Oleksy-Gębczyk, A.; Olejnik, T.P.; Jurkowski, S. Management of the Municipal Waste Stream: Waste into Energy in the Context of a Circular Economy—Economic and Technological Aspects for a Selected Region in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masum, F.H.; Zaimes, G.G.; Tan, E.C.D.; Li, S.; Dutta, A.; Ramasamy, K.K.; Hawkins, T.R. Comparing Life-Cycle Emissions of Biofuels for Marine Applications: Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Wet Wastes, Pyrolysis of Wood, Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis of Landfill Gas, and Solvolysis of Wood. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 12655–12667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Chilvers, A.; Azapagic, A. Environmental Sustainability of Biofuels: A Review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20200351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathmann, R.; Szklo, A.; Schaeffer, R. Land Use Competition for Production of Food and Liquid Biofuels: An Analysis of the Arguments in the Current Debate. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoneveld, G.C. Potential Land Use Competition from First-Generation Biofuel Expansion in Developing Countries; Occasional Paper 58; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2010; ISBN 978-602-8693-31-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Simsek, H.; Kheiralipour, K. Advanced Biofuel Production: A Comprehensive Techno-Economic Review of Pathways and Costs. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 25, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriquiry, M.A.; Du, X.; Timilsina, G.R. Second Generation Biofuels: Economics and Policies. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 4222–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R.; Taylor, M.; Saddler, J.; Mabee, W. From 1st- to 2nd-Generation Biofuel Technologies: An Overview of Current Industry and RD&D Activities; International Energy Agency (IEA) Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2008; Available online: https://task39.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/37/2013/05/From-1st-to-2nd-generation-biofuel-technologies.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Lamers, P.; Hamelinck, C.; Junginger, M.; Faaij, A. International Bioenergy Trade—A Review of Past Developments in the Liquid Biofuel Market. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2655–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, P.S.; Singh, A. Production of Liquid Biofuels from Renewable Resources. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 37, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Progress and Recent Trends in Biofuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2007, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Ridjan Skov, I.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Sorknæs, P.; Korberg, A.D.; Chang, M.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Kany, M.S. The Role of Sustainable Bioenergy in a Fully Decarbonised Society. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.; Wietschel, M. The Future of Hydrogen—Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, F.; Leker, J. Future Costs of Hydrogen: A Quantitative Review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 2345–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Hydrogen Review 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2024 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Bioenergy & Biofuels; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024; Available online: https://www.irena.org/Energy-Transition/Technology/Bioenergy-and-biofuels (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Abdelsalam, R.A.; Mohamed, M.; Farag, H.E.Z.; El-Saadany, E.F. Green Hydrogen Production Plants: A Techno-Economic Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 319, 118907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Engineering. The Hydrogen Economy: Opportunities, Costs, Barriers, and R&D Needs; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2023/2413 (RED III) Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001 on the Promotion of Renewable Energy. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L 2413. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/2413/oj (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- The Royal Society. Sustainable Biofuels: Prospects and Challenges; The Royal Society: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-85403-662-2. Available online: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2008/sustainable-biofuels/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Marmiroli, B.; Messagie, M.; Dotelli, G.; Van Mierlo, J. Electricity Generation in LCA of Electric Vehicles: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.; Bodziacki, S.; Famielec, S.; Huptyś, D.; Kurpaska, S.; Latała, H.; Basak, Z. Environmental Impact Assessment of Heat Storage System in Rock-Bed Accumulator. Energies 2025, 18, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Battery Electric and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles Considering the Impact of Electricity Generation Mix: A Case Study in China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczek, A.; Woźniak, A.; Żegleń, P. National Diversity in European Energy Policy: Analyzing Dependencies of Changes in Energy Prices, Climate Regulations, and Technological Innovations on Economic Implications. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 62, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, A.; Kluczek, A.; Nycz, P.D. Approach for Identifying the Impact of Local Wind and Spatial Conditions on Wind Turbine Blade Geometry. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 7310206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, K.J.; Árnadóttir, Á.; Heinonen, J.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Davíðsdóttir, B. Review and Meta-Analysis of EVs: Embodied Emissions and Environmental Breakeven. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordelöf, A.; Messagie, M.; Tillman, A.; Söderman, M.L.; Van Mierlo, J. Environmental Impacts of Hybrid, Plug-In Hybrid, and Battery Electric Vehicles—What Can We Learn from Life Cycle Assessment? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 1866–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, R.; Kennedy, D.W. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Performance of Electric and Fossil-Fueled Passenger Vehicles with Uncertainty Estimates Using a Probabilistic Life-Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.H.; Ayadi, W.; Hussain, G.A.; Haider, Z.M.; Alkhatib, F.; Lehtonen, M. Evaluating Carbon Emissions: A Lifecycle Comparison Between Electric and Conventional Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Salzinger, M.; Remppis, S.; Schober, B.; Held, M.; Graf, R. Reducing the Environmental Impacts of Electric Vehicles and Electricity Supply: How Hourly Defined Life Cycle Assessment and Smart Charging Can Contribute. World Electr. Veh. J. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Freire, F. Marginal Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Electricity Generation in Portugal and Implications for Electric Vehicles. Resources 2016, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, C.; Meisterling, K. Life Cycle Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Plug-in Hybrid Vehicles: Implications for Policy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3170–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussan, M.; Neirotti, F. Cross-Country Comparison of Hourly Electricity Mixes for EV Charging Profiles. Energies 2020, 13, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshadravan, A.; Cheah, L.; Roth, R.; Freire, F.; Dias, L.; Gregory, J. Stochastic Comparative Assessment of Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Conventional and Electric Vehicles; Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/103107 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Obrador Rey, S.; Canals Casals, L.; Gevorkov, L.; Cremades Oliver, L.; Trilla, L. Critical Review on the Sustainability of Electric Vehicles: Addressing Challenges without Interfering in Market Trends. Electronics 2024, 13, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroma, M.S.; Brown, N.; Cardellini, G.; Messagie, M. Prospective Environmental Impacts of Passenger Cars under Different Energy and Steel Production Scenarios. Energies 2020, 13, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, J.H.T.; Tran, C.; Ton-That, D. A Paradox over Electric Vehicles, Mining of Lithium for Car Batteries. Energies 2022, 15, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, L.M.; D’Urso, D.; Trapani, N.; Chiacchio, F. Electrifying Green Logistics: A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Electric and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiberg, S.; Emond, E.; Allen, C.; Raya, D.; Gadhamshetty, V.; Dhiman, S.S.; Ravilla, A.; Celik, I. Environmental Impact Assessment of Autonomous Transportation Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolganova, I.; Rödl, A.; Bach, V.; Kaltschmitt, M.; Finkbeiner, M. A Review of Life Cycle Assessment Studies of Electric Vehicles with a Focus on Resource Use. Resources 2020, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, F. Critical Minerals for Zero-Emission Transportation. Materials 2022, 15, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondorf, L.; Köhler, L.; Grein, T.; Epple, F.; Philipps, F.; Aigner, M.; Schripp, T. Airborne Brake Wear Emissions from a Battery Electric Vehicle. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardo, A.; Dotelli, G.; Miretti, F.; Spessa, E. End-of-Life Impact on the Cradle-to-Grave LCA of Light-Duty Commercial Vehicles in Europe. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovinaru, F.I.; Rovinaru, M.D.; Rus, A.V. The Economic and Ecological Impacts of Dismantling End-of-Life Vehicles in Romania. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegoda, J.; Charbel, G.; Watts, D. Second Life of Used Lithium-Ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles in the USA. Environments 2024, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotak, Y.; Marchante Fernández, C.; Canals Casals, L.; Kotak, B.S.; Koch, D.; Geisbauer, C.; Trilla, L.; Gómez-Núñez, A.; Schweiger, H.-G. End of Electric Vehicle Batteries: Reuse vs. Recycle. Energies 2021, 14, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.; Salmon, J. EV Adoption Influence on Air Quality and Associated Infrastructure Costs. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costagliola, M.A.; Marchitto, L.; Giuzio, R.; Casadei, S.; Rossi, T.; Lixi, S.; Faedo, D. Non-Exhaust Particulate Emissions from Road Transport Vehicles. Energies 2024, 17, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Kumar, P. Beyond the Tailpipe: Review of Non-Exhaust Airborne Nanoparticles from Road Vehicles. Eco-Environ. Health 2024, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, F. Electric Vehicles: Benefits, Challenges, and Potential Solutions for Widespread Adaptation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, F.; Guo, C. Carbon Reduction Potential of Private Electric Vehicles: Synergistic Effects of Grid Carbon Intensity, Driving Intensity, and Vehicle Efficiency. Processes 2025, 13, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ha, N.; Li, T. Research on Carbon Emissions of Electric Vehicles throughout the Life Cycle Assessment Taking into Vehicle Weight and Grid Mix Composition. Energies 2019, 12, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchart, D.; Przytuła, I. Carbon Footprint of Electric Vehicles—Review of Methodologies and Determinants. Energies 2024, 17, 5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raugei, M.; Peluso, A.; Leccisi, E.; Fthenakis, V. Life-Cycle Carbon Emissions and Energy Implications of High Penetration of Photovoltaics and Electric Vehicles in California. Energies 2021, 14, 5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G.; Quaranta, S.; Inguanta, R.; Certa, A.; Venticinque, M. A Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Framework for Zero Emission Vehicle Fleet Renewal Considering Lifecycle and Scenario Uncertainty. Energies 2024, 17, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, A.; Ciuła, J.; Cembruch-Nowakowski, M.; Zacłona, T. Polish Farmers’ Perceptions of the Benefits and Risks of Investing in Biogas Plants and the Role of GISs in Site Selection. Energies 2025, 18, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement; UNFCCC: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- UNFCCC. Conference of the Parties (COP) Reports; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM(2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- European Commission. ‘Fit for 55’: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality; Communication COM(2021) 550 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0550 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2023/1804 on the Deployment of Alternative Fuels Infrastructure (AFIR); Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1804/oj/eng (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Republic of Poland. Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels; Dz.U. 2024, pos. 1853. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20240001853 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management (NFOŚiGW). Priority Program “My Electric”; NFOŚiGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/moj-elektryk (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management (NFOŚiGW). “NaszEauto” Program—2025 Recruitment Rules; NFOŚiGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Ministry of Climate and Environment. Polish Energy Policy Until 2040 (PEP2040); Ministry of Climate and Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polityka-energetyczna-polski-do-2040-r (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2023/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 April 2023 Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/631 as Regards Strengthening the CO2 Emission Performance Standards for New Passenger Cars and New Light Commercial Vehicles in Line with the Union’s Increased Climate Ambition. Off. J. Eur. Union 2025, L 110, 5–20. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/851/oj (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Albatayneh, A.; Assi, A.; Alterman, D.; Jaradat, M. Comparison of the Overall Energy Efficiency for Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles and Electric Vehicles. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2020, 24, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2020: Entering the Decade of Electric Drive? OECD/IEA Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/global-ev-outlook-2020_d394399e-en.html (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Efficiency 2021—Executive Summary; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2021 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Mats, A.; Mitryasova, O.; Salamon, I.; Kochanek, A. Atmospheric air temperature as an integrated indicator of climate change. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2025, 26, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchart, D.; Przytuła, I. Review of Environmental Life Cycle Assessment for Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles in Road Transport. Energies 2025, 18, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederzoli, D.W.; Carnevali, C.; Genova, R.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Del Borghi, A.; Gallo, M.; Moreschi, L. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen-powered city buses in the High V.LO-City project: Integrating vehicle operation and refuelling infrastructure. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Dong, Z. Fuel Selections for Electrified Vehicles: A Well-to-Wheel Analysis. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Stimming, U. Well to Wheel Analysis of Low Carbon Alternatives for Road Traffic. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3313–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, F.; Bibas, R.; Mima, S.; Muratori, M.; Sakamoto, S.; Sano, F.; Bauer, N.; Daioglou, V.; Fujimori, S.; Gidden, M.J.; et al. The Contribution of Bioenergy to the Decarbonization of Transport: A Multi-Model Assessment. Clim. Change 2022, 170, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Transport—Renewables 2018: Analysis; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2018 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- European Commission. ReFuelEU Aviation and FuelEU Maritime: Sustainable Alternative Fuels in Transport; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Passenger Cars in the European Union: A 2025 Update and Key Factors to Consider; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://theicct.org/publication/electric-cars-life-cycle-analysis-emissions-europe-jul25 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Malinowski, M.; Basak, Z.; Famielec, S.; Bieszczad, A.; Angrecka, S.; Bodziacki, S. Life Cycle Assessment of the Construction and Demolition Waste Recovery Process. Materials 2025, 18, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | EV | ICE | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drive system efficiency [%] | 15–25 | 18–28 | [63,64] |

| Energy consumption [kWh/100 km] | 16–21 | 60–82 | [65,66] |

| CO2 emissions [g/km, WtW] | 80–95 | 160–200 | [67,68] |

| Operating costs [€/100 km] | 2.6–3.0 | 7.5–9.0 | [69,70] |

| Share of renewable energy sources in power supply [%] | 30 | 0 | [71,72] |

| Feature-Fuel | Bioethanol | Biodiesel (FAME) | Biomethane (Bio-CNG and Bio-LNG) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw material source | Corn, sugar cane, wheat | Vegetable oils, waste fats | Organic waste, manure, sewage | [118] |

| Production method | Alcoholic fermentation | Transesterification | Anaerobic fermentation + purification | [126,127] |

| Application | Gasoline engines (E5–E85) | Diesel engines (B7–B100) | Gas engines (CNG, LNG) | [119,126] |

| CO2 emissions (lifecycle) | Reduction to ~60–70% compared to gasoline | Reduction to ~80% vs. diesel | Even negative emissions (when from waste) | [126] |

| NOx and particulate emissions | 1–2 g/kWh | ~7.5–9 g/kWh | ≈1–2 g/kWh | [128,129,130] |

| Vehicle compatibility | E10 without modification; E85—FlexFuel | B7—no modification required; B100—modification required | Requires a dedicated CNG/LNG engine | [119] |

| Calorific value (MJ/kg) | 27 | 37–40 | 50 (for CH4) | [126] |

| Disadvantages | Hygroscopic, less caloric | Poor cold resistance | High infrastructure costs | [131] |

| Threat to food | High | High or medium (depending on the raw material) | Low (mainly waste) | [132,133,134] |

| Criterion | Fuel Type | Applications (Global Projects) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GHG emission reduction | Green hydrogen (H2 from RES) | HYBRIT—Sweden: CO2-free steel (SSAB, LKAB, Vattenfall). Reduction > 90%. | [147,148] |

| Advanced biofuels (SAF, HVO) | Neste MY SAF—Finland: up to 80% reduction in aviation emissions (Air France, KLM). | [136,149] | |

| Technological maturity | Green hydrogen | NEOM Project—Saudi Arabia: 4 GW RES → 650 t H2/day (Air Products, ACWA Power). | [150] |

| 2G biofuels (lignocellulosic) | UPM Biofuels—Lappeenranta (Finland): HVO biofuel from wood waste; industrial scale. | [139] | |

| Infrastructure and logistics | Green hydrogen | Hydrogen Mobility Germany (H2Mobility DE): >100 H2 stations, integration with truck fleets. | [149,151] |

| Biofuels (HEFA/SAF) | Rotterdam BioPort—Netherlands: biofuel logistics hub (Neste, Shell, bp). | [149,152] | |

| CAPEX/OPEX costs | Green hydrogen | Gigafactory H2 Lingen—Germany: 200 MW electrolyzer (bp + Ørsted); reduction of production costs to €3/kg by 2030. | [147,150] |

| Biofuels | World Energy SAF—USA (Los Angeles): first commercial aviation biofuel refinery. | [136,139] | |

| Sectoral applications | Green hydrogen | Coradia iLint—Germany: Alstom train powered by H2. Toyota Mirai Fleet—Japan: hydrogen vehicles (taxis, city fleets). | [148,153] |

| Biofuels (SAF, HVO) | KLM + Neste SAF—Amsterdam: transatlantic flights using 50% biofuel. GoodFuels—Netherlands: fuel from waste for Maersk shipping. | [126,150] | |

| Raw material availability | Green hydrogen | Requires large amounts of renewable energy and water; best locations: Australia, MENA, Scandinavia. | [147,148] |

| Biofuels | Waste biomass (plant residues, used oils, lignin)—limited global supply. | [136,139] | |

| Regulations and sustainability | Green hydrogen | RFNBO (EU) certification requirement, guarantees of energy origin. | [148,152] |

| Biofuels | RED III: ILUC reduction, traceability, double counting of waste. | [151,152] | |

| Scaling perspective (2030–2040) | Green hydrogen | Large projects >1 GW (NEOM, HyDeal, Iberdrola); 10–20× increase in global production by 2035. | [148,149] |

| Biofuels | Scaling in aviation and shipping—raw material constraints; leaders: Finland, Netherlands, USA. | [136,149] |

| Document/Initiative | Scope and Legal Basis | Main Objectives | Impact on Transport Sector |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paris Agreement (2015) | Global treaty under UNFCCC | Limit global warming to 1.5–2 °C; Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) | Accelerated shift to zero-emission transport systems [190] |

| UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Strategic framework (17 SDGs) | Goal 13: Climate Action; integrate sustainability in mobility | Promotion of sustainable public transport [191] |

| COP Conferences | Annual UNFCCC meetings | Negotiate and implement Paris Agreement outcomes | Develop global norms and financing mechanisms [192] |

| Legislative Instrument | Objective | Key Measures | Relevance to Transport |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Green Deal (2019) | Achieve EU climate neutrality by 2050 | Comprehensive policy framework; European Climate Law | Supports low-emission transport innovation [193] |

| Fit for 55 Package (2021) | Reduce GHG emissions by 55% by 2030 | Revision of ETS, ESR, LULUCF, and new CO2 norms | Stimulates deployment of zero-emission vehicles [194] |

| Regulations EURO 6/7, AFIR (2023) | Set emission limits and infrastructure obligations | Ban sale of ICE vehicles after 2035; expand EV/hydrogen networks | Mandates zero-emission transport transition [195] |

| RED II and RED III Directives | Increase share of renewables to 14.5% in transport | Certification and sustainability criteria | Encourage use of biofuels and synthetic fuels [152] |

| Area | Legal and Political Instrument | Key Provisions | Effect on Transport Sector | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Framework | Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels (2018) | Defines EV charging, carsharing, zero-emission zones | Facilitates EV infrastructure growth | [196] |

| Support Programs | ‘My Electric’, ‘NaszEauto’ | Subsidies for EVs and charging infrastructure | Stimulates market adoption | [197,198] |

| Energy Policy | Polish Energy Policy 2040 (PEP2040) | Sets long-term targets for RES and transport decarbonization | Strategic planning framework | [199] |

| Implementation Challenges | AFIR and hydrogen law gaps | Insufficient charging network coverage | Delays in infrastructure deployment | [195,196] |

| Propulsion Type | Legal Basis | Regulatory Scope | Support Instruments | Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electric (BEV) | AFIR; RED III; Electromobility Act; ‘My Electric’, ‘NaszEauto’ | Charging infrastructure and zero-emission zones | Subsidies, fee exemptions | Uneven network coverage [152,195,197,198] |

| Hybrid (PHEV/HEV) | Regulation (EU) 2019/631; Fit for 55 | CO2 and NOx reduction; phase-out post-2035 | Fleet transition allowances | Limited lifespan of support [194] |

| Hydrogen (FCEV) | RED III; AFIR; Hydrogen Strategy; draft Hydrogen Law | H2 infrastructure, certification | IPCEI Hydrogen, NFOŚiGW | High costs, incomplete law [184,195,199] |

| Biofuels | RED II; RED III; Act on Biocomponents; PEP2040 | Sustainability criteria and blending targets | NCW system, excise reliefs | Limited 2G biofuels [183,199] |

| Gas (CNG/LNG) | AFIR; Energy Law; Electromobility Act | Alternative fuel infrastructure and safety | Excise exemptions | Dependence on fossil methane [195] |

| Synthetic Fuels (e-fuels) | Regulation (EU) 2023/851; CEN/CENELEC | Certification of synthetic fuels | Innovation Fund, IPCEI | Lack of standardization [200] |

| Powertrain Type | Energy Efficiency (Well-to-Wheel) | CO2 Emissions (Life Cycle) | Technology Advantages | Limitations-Challenges | Development Outlook | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electric (BEV) | 70–90% | Depends on energy mix | High efficiency, zero local emissions | Battery cost, range, charging infrastructure | Rapid growth, renewable energy integration | [201,203] |

| Hydrogen (FCEV) | 30–40% | Low with “green” hydrogen | Short refueling time, long range | High costs, lack of infrastructure | Potential in heavy transport | [205,206] |

| Hybrid (HEV/PHEV) | 30–45% | Lower than ICE | Flexibility, reduced emissions | Dependence on fossil fuels | Transitional technology | [203,204] |

| Biofuel (ICE-Biofuel) | 25–40% | Lower net CO2 emissions | Uses existing infrastructure | Limited biomass resources | Short-term solution | [207,211] |

| Synthetic fuels (e-fuels) | 30–50% | Low (if produced with renewables) | Compatible with combustion engines | High production costs | Potential for aviation and shipping | [205,206] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kochanek, A.; Zacłona, T.; Pietrucha, I.; Petryk, A.; Ziemiańczyk, U.; Basak, Z.; Guzdek, P.; Akbulut, L.; Atılgan, A.; Woźniak, A.D. Renewable Energy Integration in Sustainable Transport: A Review of Emerging Propulsion Technologies and Energy Transition Mechanisms. Energies 2025, 18, 6610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246610

Kochanek A, Zacłona T, Pietrucha I, Petryk A, Ziemiańczyk U, Basak Z, Guzdek P, Akbulut L, Atılgan A, Woźniak AD. Renewable Energy Integration in Sustainable Transport: A Review of Emerging Propulsion Technologies and Energy Transition Mechanisms. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246610

Chicago/Turabian StyleKochanek, Anna, Tomasz Zacłona, Iga Pietrucha, Agnieszka Petryk, Urszula Ziemiańczyk, Zuzanna Basak, Paweł Guzdek, Leyla Akbulut, Atılgan Atılgan, and Agnieszka Dorota Woźniak. 2025. "Renewable Energy Integration in Sustainable Transport: A Review of Emerging Propulsion Technologies and Energy Transition Mechanisms" Energies 18, no. 24: 6610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246610

APA StyleKochanek, A., Zacłona, T., Pietrucha, I., Petryk, A., Ziemiańczyk, U., Basak, Z., Guzdek, P., Akbulut, L., Atılgan, A., & Woźniak, A. D. (2025). Renewable Energy Integration in Sustainable Transport: A Review of Emerging Propulsion Technologies and Energy Transition Mechanisms. Energies, 18(24), 6610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246610