Optimization Study on the Pyrolysis Process of Moso Bamboo Wastes in a Fluidized Bed Pyrolyzer Based on Response Surface Methodology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

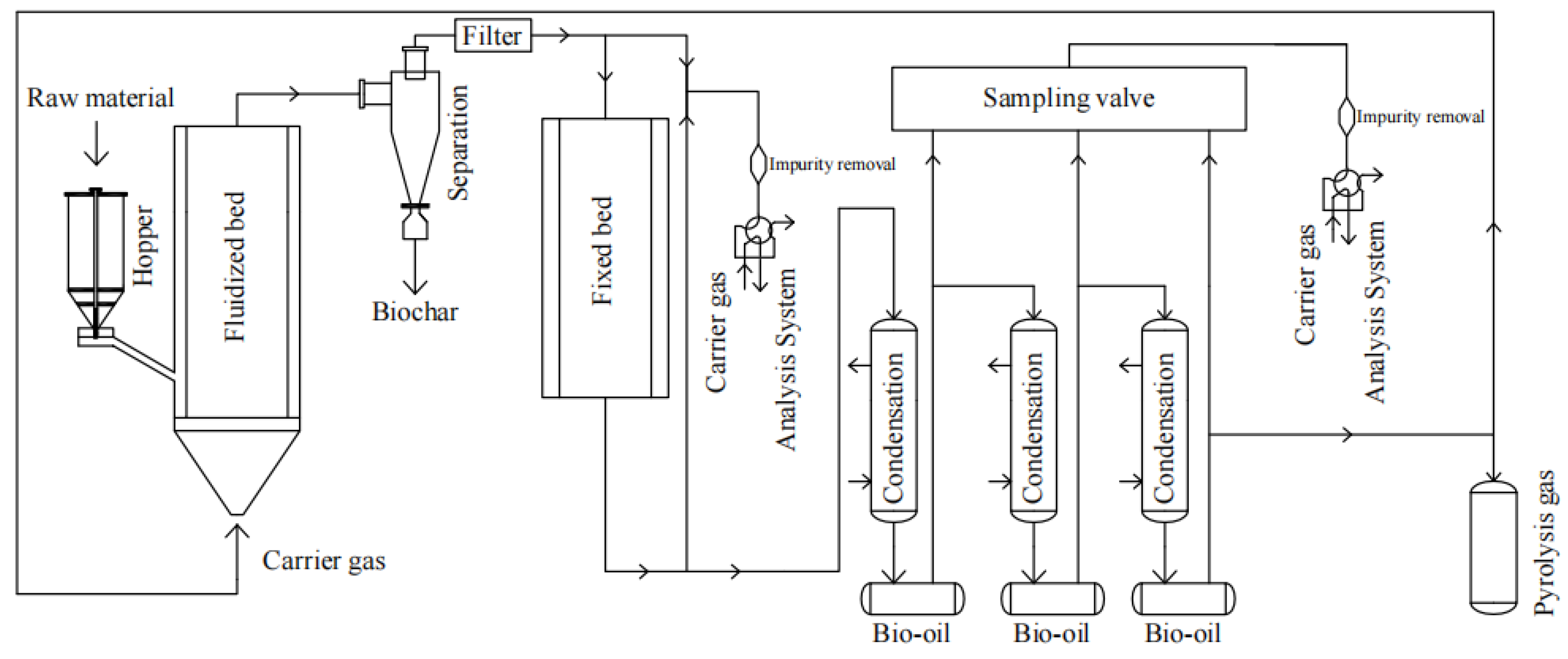

2.2. Experimental Apparatus

2.3. Experimental Design by RSM

2.4. Calculation of Product Yields

2.5. Validation Experiment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results

3.2. Effects of Various Process Parameters on Pyrolytic Product Yields

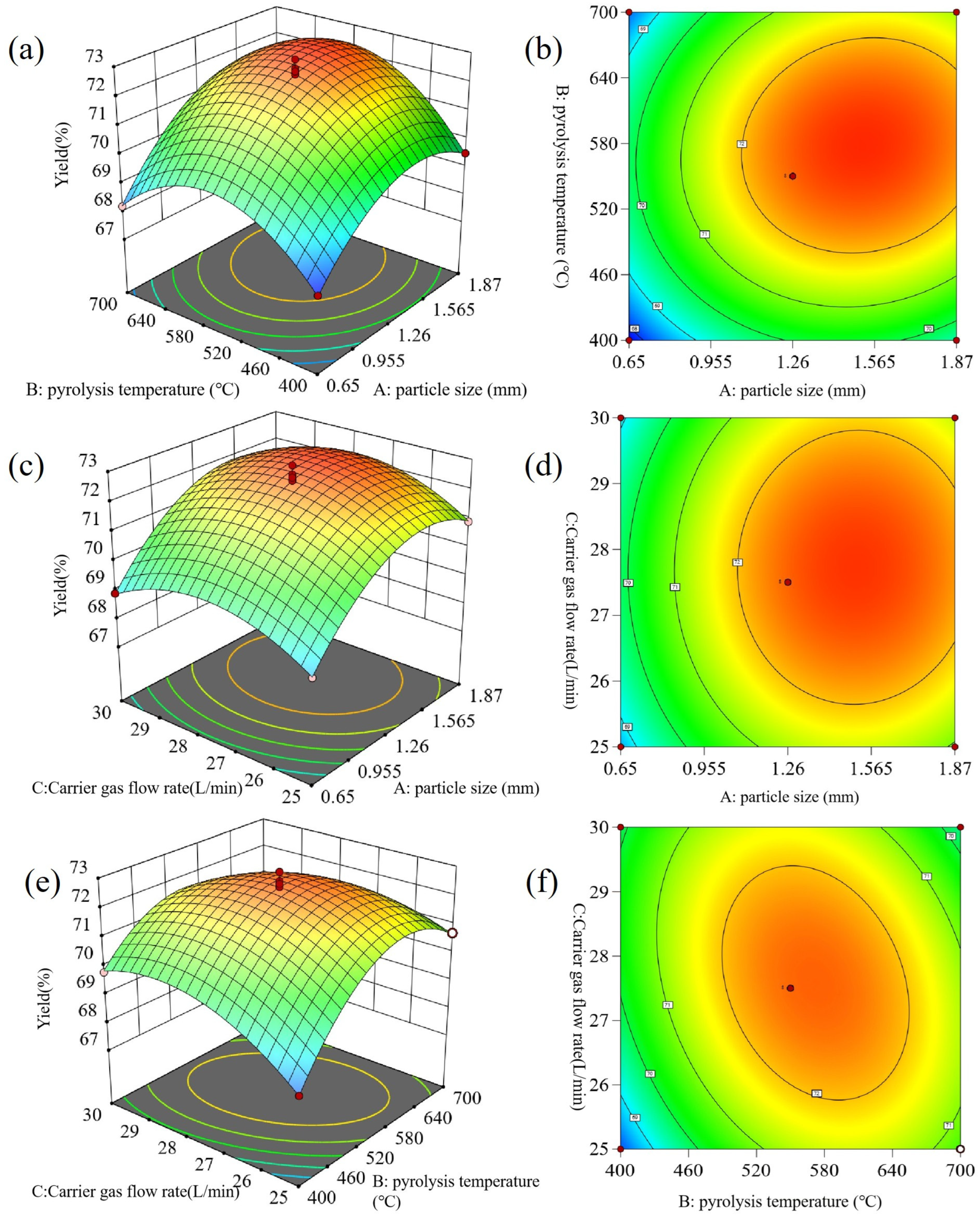

3.2.1. Yield of Both Pyrolysis Char and Oil

3.2.2. Yield of Pyrolytic Char

3.2.3. Yield of Pyrolytic Oil

3.2.4. Verify Experimental Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| TG-FTIR | Thermogravimetry–Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| Py-GCMS | Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry |

| FBR | fluidized bed reactor |

| BBD | Box–Behnken Design |

References

- Yang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Bartocci, P.; Fantozzi, F.; Mašek, O.; Agblevor, F.A.; Wei, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Lu, X.; et al. Prospective contributions of biomass pyrolysis to China’s 2050 carbon reduction and renewable energy goals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, C. Slow Pyrolysis of De-Oiled Rapeseed Cake: Influence of Pyrolysis Parameters on the Yield and Characteristics of the Liquid Obtained. Energies 2024, 17, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajdak, M.; Muzyka, R.; Gałko, G. Recent Progress in Biomass Pyrolysis and High Value Utilisation of Pyrolytic Carbon. Energies 2025, 18, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhou, T.; Li, C.; Song, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H. Development Status and Prospects of Biomass Energy in China. Energies 2024, 17, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, D.; Szabó, M.; Ceci, P.; Avino, P. Biomass Energy and Biofuels: Perspective, Potentials, and Challenges in the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luan, Y.; Hu, J.; Fang, C.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fei, B. Bamboo heat treatments and their effects on bamboo properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 331, 127320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; He, S.; Leng, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z. Replacing Plastic with Bamboo: A Review of the Properties and Green Applications of Bamboo-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, T.; Blasi, E.; Chiriacò, M.V. Carbon sequestration in a bamboo plantation: A case study in a Mediterranean area. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Yang, K.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Meng, S.; Wu, R. Effect of physical treatment methods on the properties of natural bamboo materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 394, 132170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wu, Y.; Zuo, Y. Research Status and Prospects of Resource Utilization of Bamboo Residues. World For. Res. 2021, 34, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Guo, F.; Zhu, J.; Cao, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y. A comparative study on the crystalline structure of cellulose isolated from bamboo fibers and parenchyma cells. Cellulose 2021, 28, 5993–6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, H.; Yang, J.; Yu, Z.; Xing, X.; Ma, P. Isoconversional kinetics of pyrolysis of vaporthermally carbonized bamboo. Renew. Energ. 2020, 149, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.S.; Nayak, S.; Lalnunmawii, E.; Devi, M.B.; Shagolsem, B.S.; Gouda, S. Pyrolytic oil from Muli bamboo (Melocanna baccifera, Roxb.): Biological potential and possible functional attributes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 180, 106528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, M.M.; Guimarães, T.; França, K.D.; Silva, L.S.; de Almeida, R.F.; Henrique, T.C.; Fernandes, S.A.; Tuler, G.V.; Bittencourt, R.C.; de Paula Barbosa, V.O.; et al. 2,3-Dihydrobenzofuran production eco-friendly by fast pyrolysis from Dendrocalamus asper biomass. Biomass Convers. Bior. 2025, 15, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Cheng, S. Catalytic pyrolysis of crofton weed: Comparison of their pyrolysis product and preliminary economic analysis. Environ. Prog. Sustain. 2022, 41, e13742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, D.; Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Hu, X.; Zhang, S. Fundamental Advances in Biomass Autothermal/Oxidative Pyrolysis: A Review. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11888–11905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, I.; Preciado-Hernandez, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. Utilisation of spent tyre pyrolysis char as activated carbon feedstock: The role, transformation and fate of Zn. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilber, I.; Mayer, P.; Gouliarmou, V.; Hale, S.E.; Cornelissen, G.; Schmidt, H.; Bucheli, T.D. Bioavailability and bioaccessibility of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from (post-pyrolytically treated) biochars. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, T.; Lafdani, E.K.; Laurén, A.; Pumpanen, J.; Palviainen, M. Biochar as adsorbent in purification of clear-cut forest runoff water: Adsorption rate and adsorption capacity. Biochar 2020, 2, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routray, K.; Barnett, K.J.; Huber, G.W. Hydrodeoxygenation of Pyrolysis Oils. Energy Technol.-Ger. 2017, 5, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Bai, S.; Ye, Y. High-value-added reutilization of resin pyrolytic oil: Pyrolysis process, oil detailed composition, and properties of pyrolytic oil-based composites. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 166, 110969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, C.; Veloso, M.C.C.; Romeiro, G.A.; Folly, E. Biocidal applications trends of bio-oils from pyrolysis: Characterization of several conditions and biomass, a review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 139, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Yang, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, F.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, W.; Chen, N. Clean production of laminated bamboo timber and efficient utilization of bamboo. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 20, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Neményi, A.; Kovács, G.P.; Gyuricza, C. Potential use of bamboo resources in energy value-added conversion technology and energy systems. GCB Bioenergy 2023, 15, 936–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapater, D.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Wery, F.; Cui, M.; Herguido, J.; Menendez, M.; Heynderickx, G.J.; Van Geem, K.M.; Gascon, J.; Castaño, P. Multifunctional fluidized bed reactors for process intensification. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 105, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.E.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J. Evolution and correlation of the physiochemical properties of bamboo char under successive pyrolysis process. Biochar 2024, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Wang, R.; Hongzhong, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Hu, W.; Mi, B.; Liu, Z. Investigating pyrolysis characteristics of moso bamboo through TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 256, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-T.; Wang, W.-L.; Si, H.; Wang, X.; Chang, J.-M. Transformation and products distribution of moso bamboo and derived components during pyrolysis. BioRes 2013, 8, 3685–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüdisüli, M.; Schildhauer, T.J.; Biollaz, S.M.A.; van Ommen, J.R. Scale-up of bubbling fluidized bed reactors—A review. Powder Technol. 2012, 217, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, J.; Hartge, E.; Heinrich, S. Fluidized-Bed Reactors – Status and Some Development Perspectives. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2014, 86, 2022–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, M.; Ianzito, V.; Solimene, R.; Ganda, E.T.; Salatino, P. Fluidized Bed Pyrolysis of Biomass: A Model-Based Assessment of the Relevance of Heterogeneous Secondary Reactions and Char Loading. Energ. Fuel 2022, 36, 9660–9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Qu, J.; Dai, J.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, Y.; Jin, Y.; et al. Pyrolysis of vegetable oil soapstock in fluidized bed: Characteristics of thermal decomposition and analysis of pyrolysis products. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chakraborty, J.P.; Mondal, M.K. Pyrolysis of torrefied biomass: Optimization of process parameters using response surface methodology, characterization, and comparison of properties of pyrolysis oil from raw biomass. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, E.R.; Brinkman, C.K.; Peters, C.; MacInnis, C.; Boyd, B. Phosphorus removal from fermented dairy manure concurrent with polyhydroxybutyrate-co-valerate synthesis under aerobic conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 402, 130789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, A.; Kazemi, S.; Hamidani, G.; Zarghami, R.; Mostoufi, N. CFD-DEM modeling of biomass pyrolysis in a DBD plasma fluidized bed. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 196, 152553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Research on Key Technologies for Rapid Pyrolysis of Wood in a Novel Jet Circulating Fluidized Bed. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Research on Key Technologies of Rapid Pyrolysis in Spouted Fluidized Bed and Application of Products. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rony, Z.I.; Rasul, M.G.; Jahirul, M.I.; Hasan, M.M. Optimizing Seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum) Thermal Pyrolysis for Environmental Sustainability: A Response Surface Methodology Approach and Analysis of Bio-Oil Properties. Energies 2024, 17, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papuga, S.; Savković, J.; Djurdjevic, M.; Ciprioti, S.V. Effect of Feed Mass, Reactor Temperature, and Time on the Yield of Waste Polypropylene Pyrolysis Oil Produced via a Fixed-Bed Reactor. Polymers 2024, 16, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, B.; Ramesh, D.; Sriramajayam, S.; Uma, D. Optimization of Pyrolysis Process Parameters for Fuel Oil Production from the Thermal Recycling of Waste Polypropylene Grocery Bags Using the Box–Behnken Design. Recycling 2024, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, F.; Rasul, M.G.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Jahirul, M.I. Optimisation of Process Parameters to Maximise the Oil Yield from Pyrolysis of Mixed Waste Plastics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqsha, A.; Tijani, M.M.; Moghtaderi, B.; Mahinpey, N. Catalytic pyrolysis of straw biomasses (wheat, flax, oat and barley) and the comparison of their product yields. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 125, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L. Co-pyrolysis of corn stalk and coal fly ash: A case study on catalytic pyrolysis behavior, bio-oil yield and its characteristics. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 38, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; He, L.; Zhu, F.; Wang, J.; Xu, R.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Y. Experimental study on flow regimes in debris bed formation behavior with mixed-size particles. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 133, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Meng, W.; Cheng, S.; Xing, B.; Yi, G.; Zhang, C. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on pyrolysis of Camellia oleifera shell. Biomass Convers. Bior. 2024, 14, 26753–26763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Kong, S. High-Resolution Particle-Scale Simulation of Biomass Pyrolysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 5456–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Rong, J.; Zhang, K.; Fan, X. Impact of solid and gas flow patterns on solid mixing in bubbling fluidized beds. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 132, 1037–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Aramideh, S.; Kong, S. Modeling Effects of Operating Conditions on Biomass Fast Pyrolysis in Bubbling Fluidized Bed Reactors. Energ. Fuel 2013, 27, 5948–5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Ashraf, M.; Shahzad, K.; Saleem, M.; Chughtai, A. Fluidized bed fast pyrolysis of corn stover: Effects of fluidizing gas flow rate and composition. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 4244–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkawi, Y.; Yu, X.; Ocone, R. Parametric analysis of biomass fast pyrolysis in a downer fluidized bed reactor. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Range | Particle Size A (mm/mesh) | Pyrolysis Temperature B (°C) | Carrier Gas Flow Rate C (L/min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limit | 1.87 (8–10) | 700 | 30 |

| Median | 1.26 (12–14) | 450 | 27.5 |

| Lower limit | 0.65 (24–28) | 400 | 25 |

| Sequence Number | Variables (Research Factors) | Response (Yield) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size (mm/mesh Size) | Pyrolysis Temperature (°C) | Carrier Gas Flow Rate (L/min) | Yield of Pyrolytic Char (%) | Yield of Pyrolytic Oil (%) | Yield (%) | |

| 1 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 27.8 | 44.8 | 72.6 |

| 2 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 27.6 | 44.9 | 72.5 |

| 3 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 27.9 | 44.8 | 72.7 |

| 4 | 0.65 (24–28) | 550 | 30 | 26.3 | 42.6 | 68.9 |

| 5 | 1.87 (8–10) | 700 | 27.5 | 27.6 | 43.6 | 71.2 |

| 6 | 1.26 (12–14) | 400 | 30 | 25.6 | 44.2 | 69.8 |

| 7 | 0.65 (24–28) | 400 | 27.5 | 24.2 | 43.5 | 67.7 |

| 8 | 1.26 (12–14) | 400 | 25 | 26.2 | 41.9 | 68.1 |

| 9 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 27.4 | 44.8 | 72.2 |

| 10 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 28.1 | 44.9 | 73 |

| 11 | 1.26 (12–14) | 700 | 25 | 27.2 | 43.5 | 70.7 |

| 12 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 27.4 | 45.1 | 72.5 |

| 13 | 1.87 (8–10) | 400 | 27.5 | 26.6 | 42.9 | 69.5 |

| 14 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 27.4 | 44.9 | 72.3 |

| 15 | 0.65 (24–28) | 550 | 25 | 26.2 | 42.4 | 68.6 |

| 16 | 1.26 (12–14) | 700 | 30 | 26.8 | 42.8 | 69.6 |

| 17 | 0.65 (24–28) | 700 | 27.5 | 26.2 | 42 | 68.2 |

| 18 | 1.87 (8–10) | 550 | 25 | 28.4 | 42.5 | 70.9 |

| 19 | 1.26 (12–14) | 550 | 27.5 | 27.5 | 44.6 | 72.1 |

| 20 | 1.87 (8–10) | 550 | 30 | 28.1 | 43.3 | 71.4 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 19.05 | 9 | 2.12 | 31.9 | <0.0001 | significant |

| A | 7.61 | 1 | 7.61 | 114.58 | <0.0001 | |

| B | 3.38 | 1 | 3.38 | 50.92 | <0.0001 | |

| C | 0.18 | 1 | 0.18 | 2.71 | 0.1306 | |

| AB | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 3.77 | 0.081 | |

| AC | 0.04 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.6026 | 0.4555 | |

| BC | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1507 | 0.706 | |

| A2 | 0.5402 | 1 | 0.5402 | 8.14 | 0.0172 | |

| B2 | 5.98 | 1 | 5.98 | 90.1 | <0.0001 | |

| C2 | 0.0087 | 1 | 0.0087 | 0.1318 | 0.7241 | |

| Residual | 0.6638 | 10 | 0.0664 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.165 | 3 | 0.055 | 0.7719 | 0.5454 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 0.4988 | 7 | 0.0713 | |||

| Cor Total | 19.72 | 19 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 22.82 | 9 | 2.54 | 80.51 | <0.0001 | significant |

| A | 0.4050 | 1 | 0.4050 | 12.83 | 0.0050 | |

| B | 0.0450 | 1 | 0.0450 | 1.43 | 0.2596 | |

| C | 0.8450 | 1 | 0.8450 | 26.83 | 0.0004 | |

| AB | 1.21 | 1 | 1.21 | 38.41 | 0.0001 | |

| AC | 0.0900 | 1 | 0.0900 | 2.86 | 0.1218 | |

| BC | 2.25 | 1 | 2.25 | 71.43 | <0.0001 | |

| A2 | 5.79 | 1 | 5.79 | 183.67 | <0.0001 | |

| B2 | 2.40 | 1 | 2.40 | 76.28 | <0.0001 | |

| C2 | 4.80 | 1 | 4.80 | 152.47 | <0.0001 | |

| Residual | 0.3150 | 10 | 0.0315 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.1750 | 3 | 0.0583 | 2.92 | 0.1100 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 0.1400 | 7 | 0.0200 | |||

| Cor Total | 23.14 | 19 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 59.44 | 9 | 6.6 | 110.3 | <0.0001 | significant |

| A | 11.52 | 1 | 11.52 | 192.4 | <0.0001 | |

| B | 2.65 | 1 | 2.65 | 44.18 | <0.0001 | |

| C | 0.245 | 1 | 0.245 | 4.09 | 0.0706 | |

| AB | 0.36 | 1 | 0.36 | 6.01 | 0.0341 | |

| AC | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.167 | 0.6914 | |

| BC | 1.96 | 1 | 1.96 | 32.73 | 0.0002 | |

| A2 | 9.86 | 1 | 9.86 | 164.7 | <0.0001 | |

| B2 | 15.96 | 1 | 15.96 | 266.63 | <0.0001 | |

| C2 | 5.22 | 1 | 5.22 | 87.21 | <0.0001 | |

| Residual | 0.5988 | 10 | 0.0599 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.01 | 3 | 0.0033 | 0.0396 | 0.9886 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 0.5888 | 7 | 0.0841 | |||

| Cor Total | 60.04 | 19 | ||||

| Model | 59.44 | 9 | 6.6 | 110.3 | <0.0001 | significant |

| Sequence Number | Variables (Research Factors) | Response (Yield) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size (mesh Size) | Pyrolysis Temperature (°C) | Carrier Gas Flow Rate (L/min) | Yield of Pyrolytic Char (%) | Yield of Pyrolytic Oil (%) | Yield (%) | |

| 1 | 10–12 | 577 | 27.5 | 29.43 | 42.13 | 71.56 |

| 2 | 10–12 | 577 | 27.5 | 29.26 | 43.62 | 72.88 |

| 3 | 10–12 | 577 | 27.5 | 27.27 | 44.74 | 72.01 |

| Average | - | - | - | 28.65 | 43.50 | 72.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Ren, X. Optimization Study on the Pyrolysis Process of Moso Bamboo Wastes in a Fluidized Bed Pyrolyzer Based on Response Surface Methodology. Energies 2025, 18, 6600. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246600

Yan Z, Li Y, Guo Z, Ren X. Optimization Study on the Pyrolysis Process of Moso Bamboo Wastes in a Fluidized Bed Pyrolyzer Based on Response Surface Methodology. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6600. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246600

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Zongchen, Ying Li, Zhijia Guo, and Xueyong Ren. 2025. "Optimization Study on the Pyrolysis Process of Moso Bamboo Wastes in a Fluidized Bed Pyrolyzer Based on Response Surface Methodology" Energies 18, no. 24: 6600. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246600

APA StyleYan, Z., Li, Y., Guo, Z., & Ren, X. (2025). Optimization Study on the Pyrolysis Process of Moso Bamboo Wastes in a Fluidized Bed Pyrolyzer Based on Response Surface Methodology. Energies, 18(24), 6600. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246600