Comprehensive Benefit Evaluation of Residential Solar and Battery Systems in Japan Considering Outage Mitigation and Battery Degradation

Abstract

1. Introduction

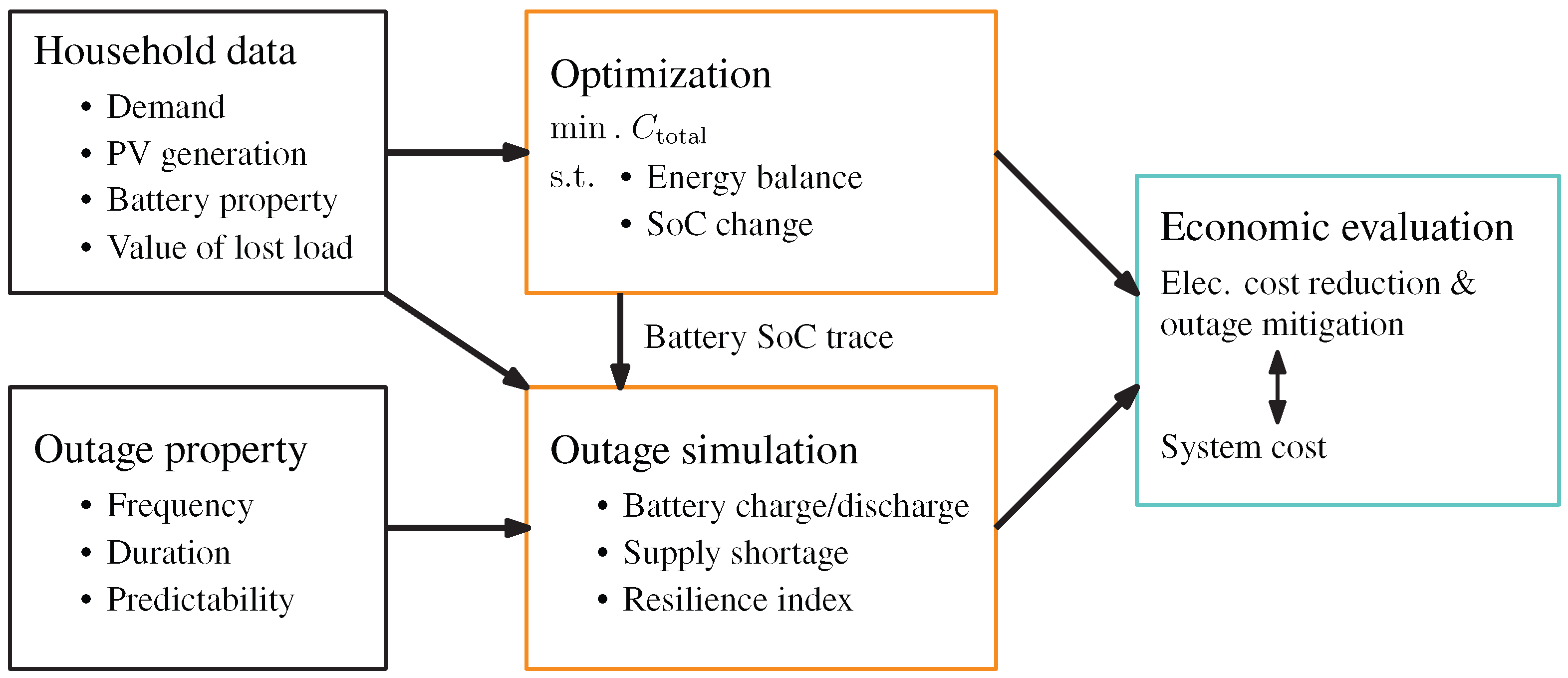

- It evaluates electricity cost reductions and PV/BESS equipment costs through optimization explicitly considering battery degradation.

- It simulates operations during outages and evaluates supply continuity for critical loads.

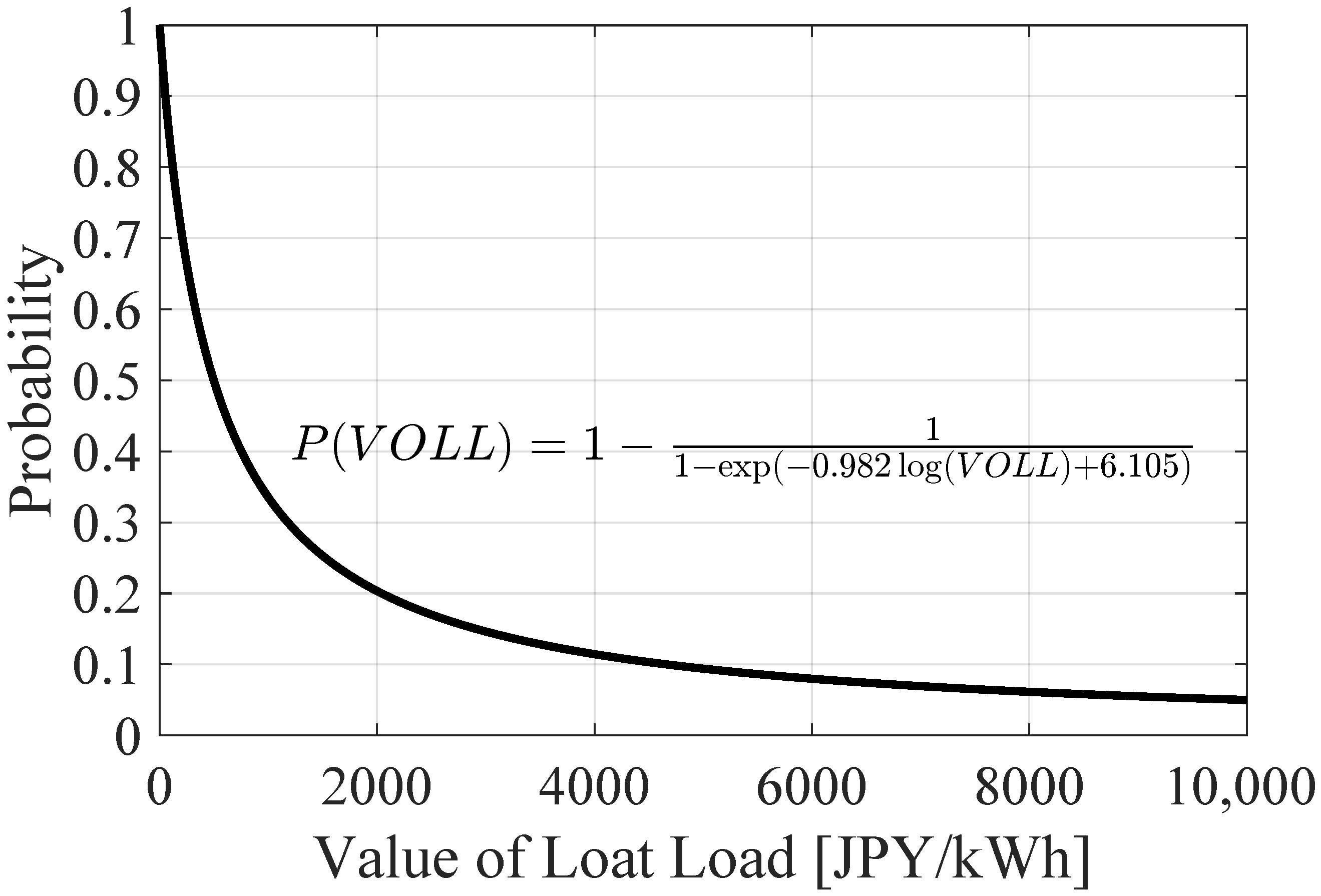

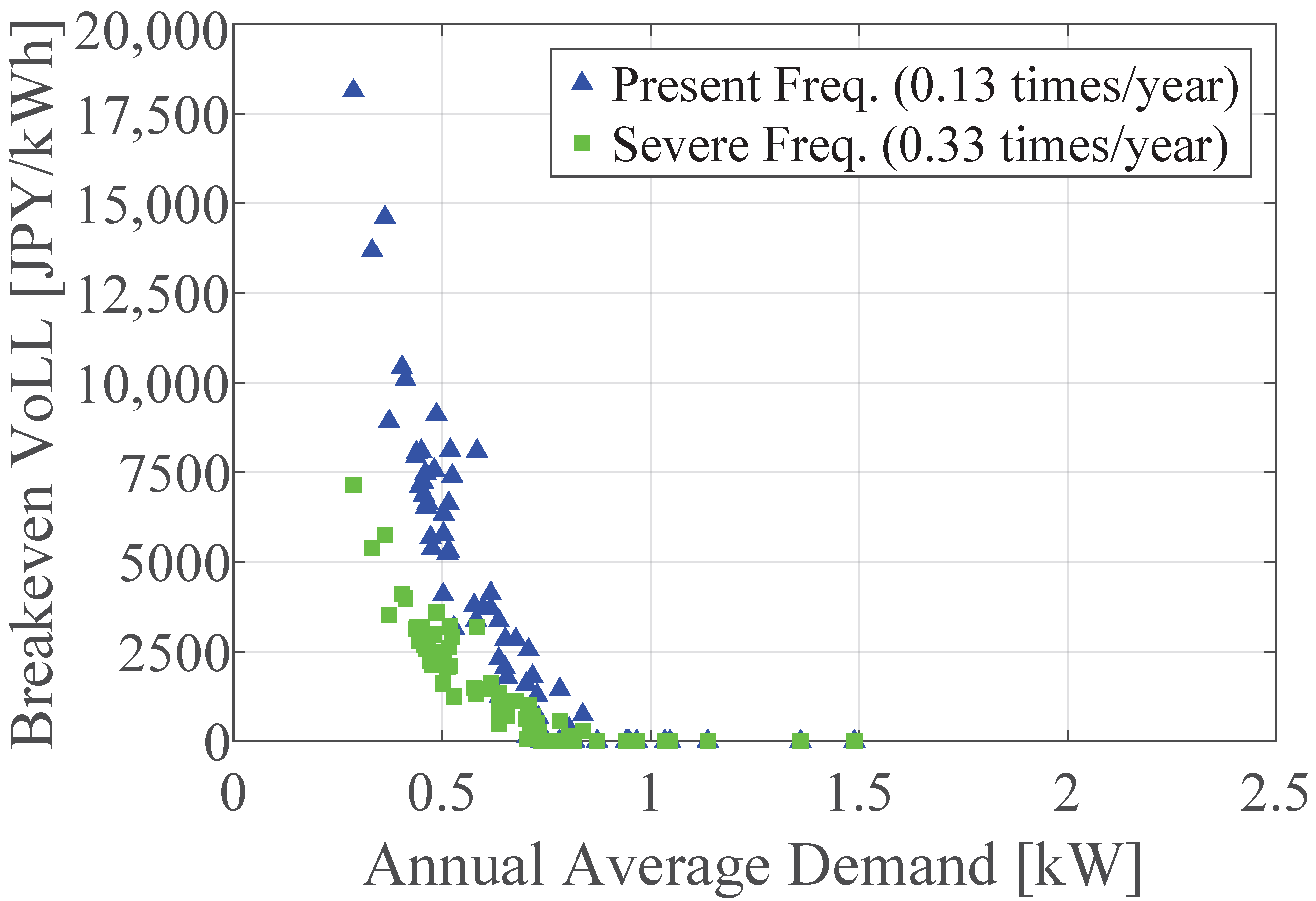

- It combines outage mitigation benefits with economic efficiency, considering the distribution of residential VoLLs.

2. Method

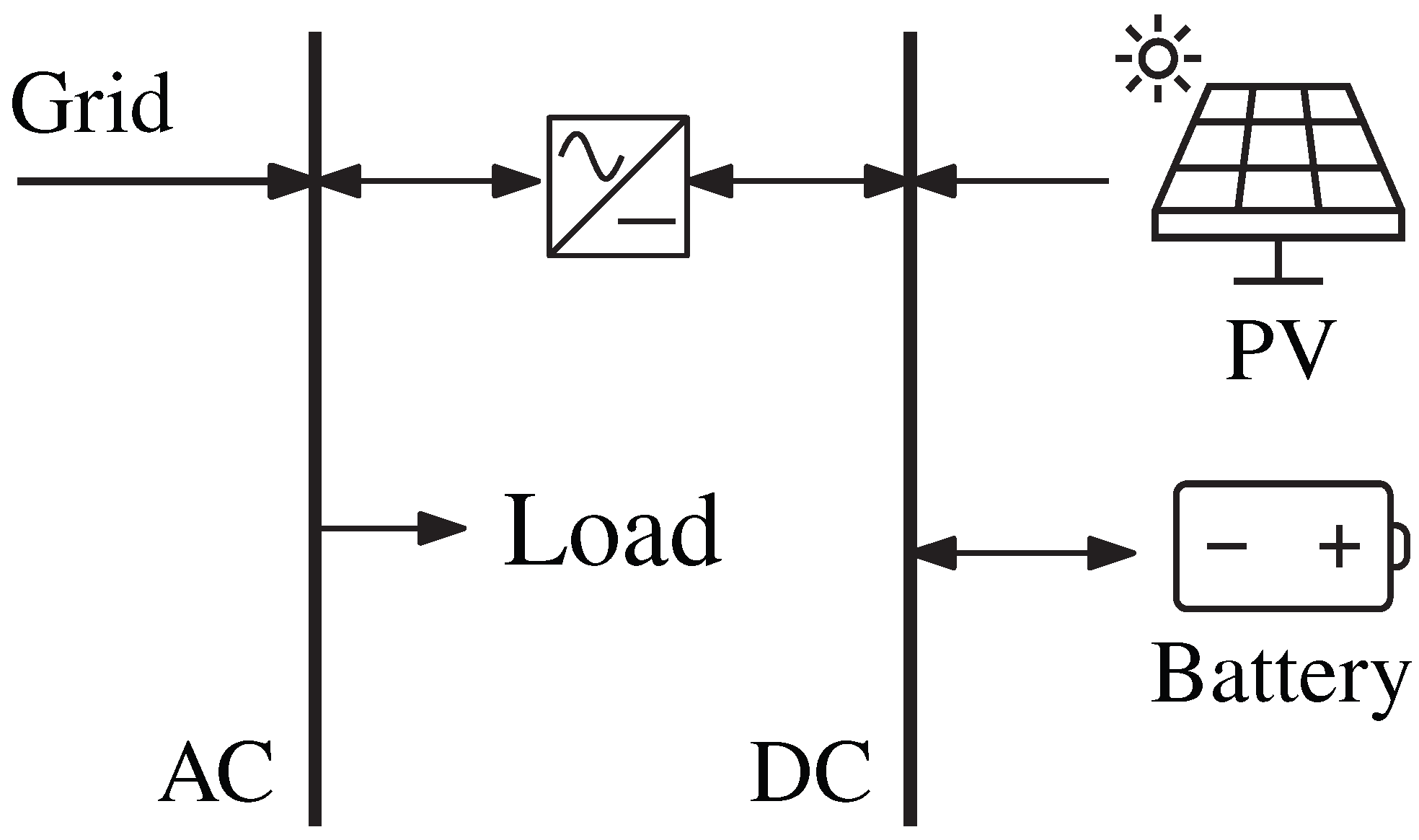

2.1. Household Model

2.2. Battery Degradation Model

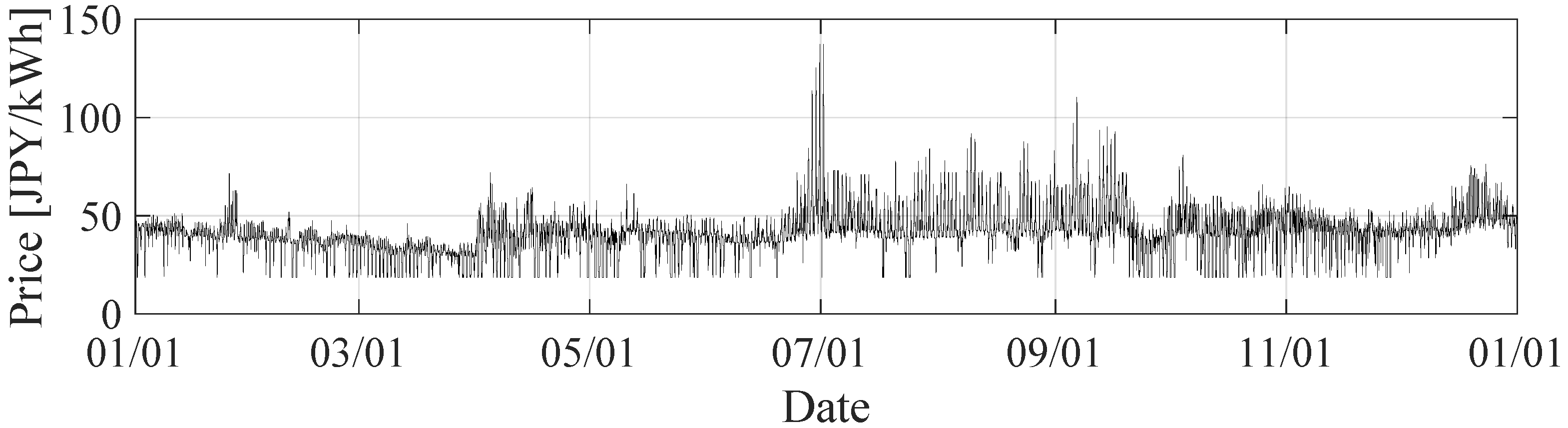

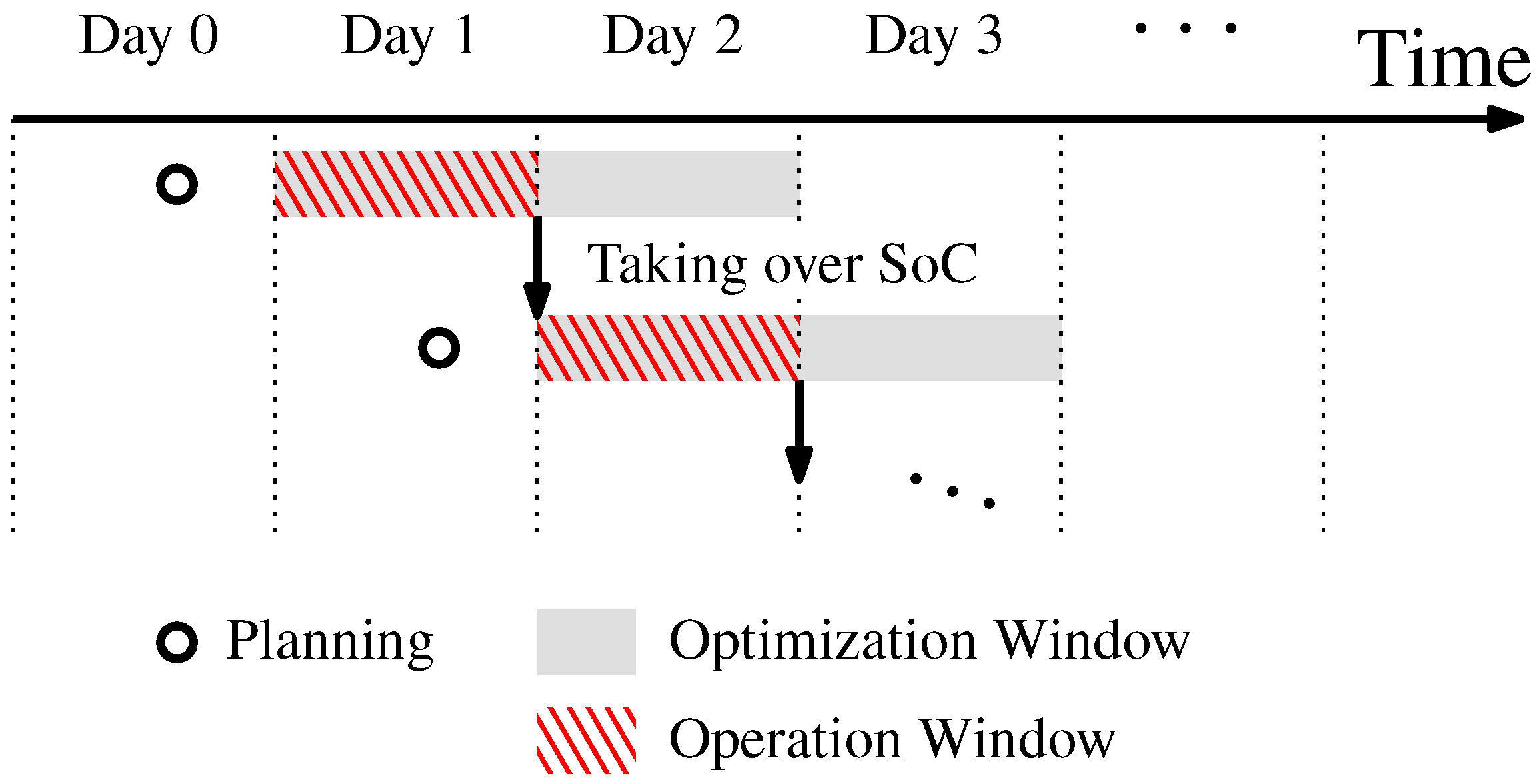

2.3. Optimization for Normal Operation

2.4. Outage Mitigation

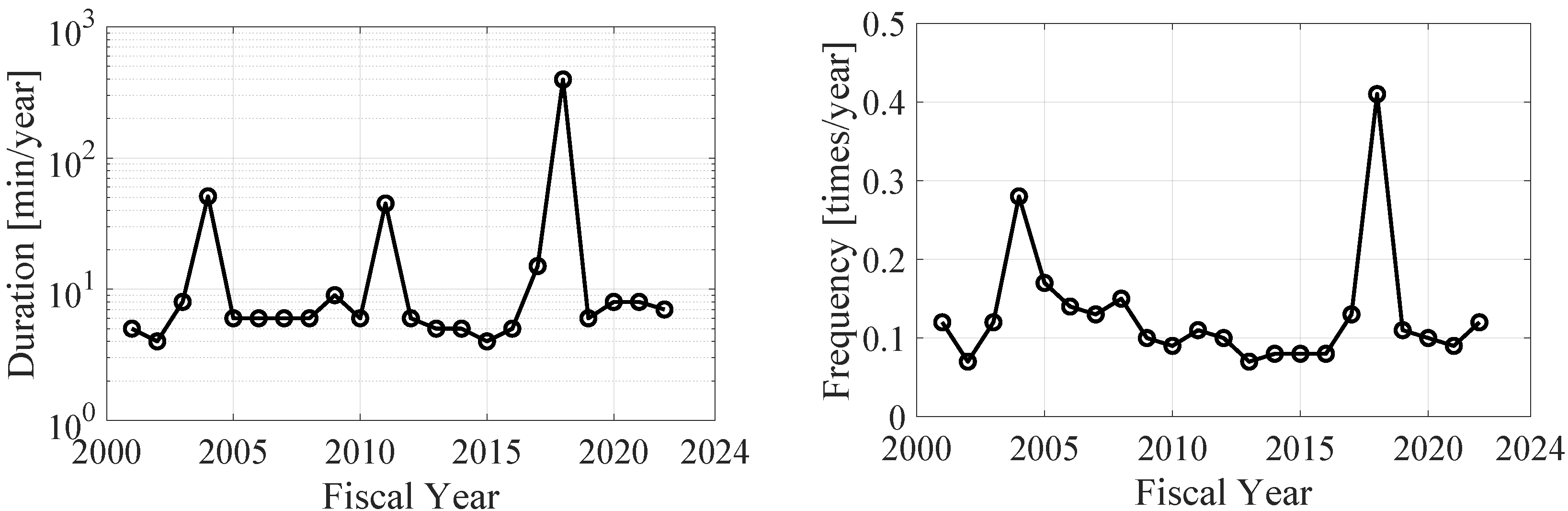

2.4.1. Supply Interruptions in Japan

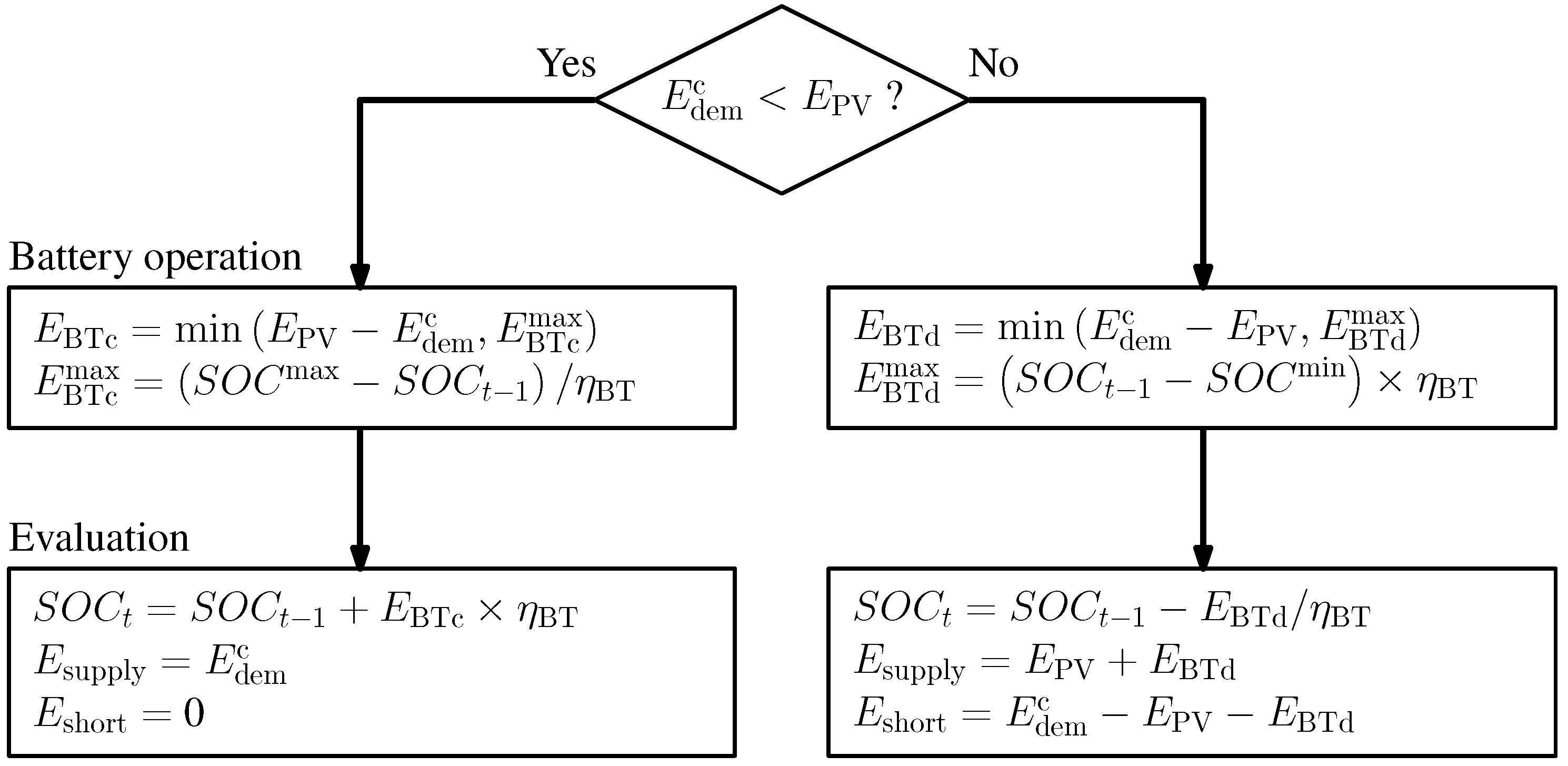

2.4.2. Supply Simulation During Outages

2.5. Evaluation of Simulations

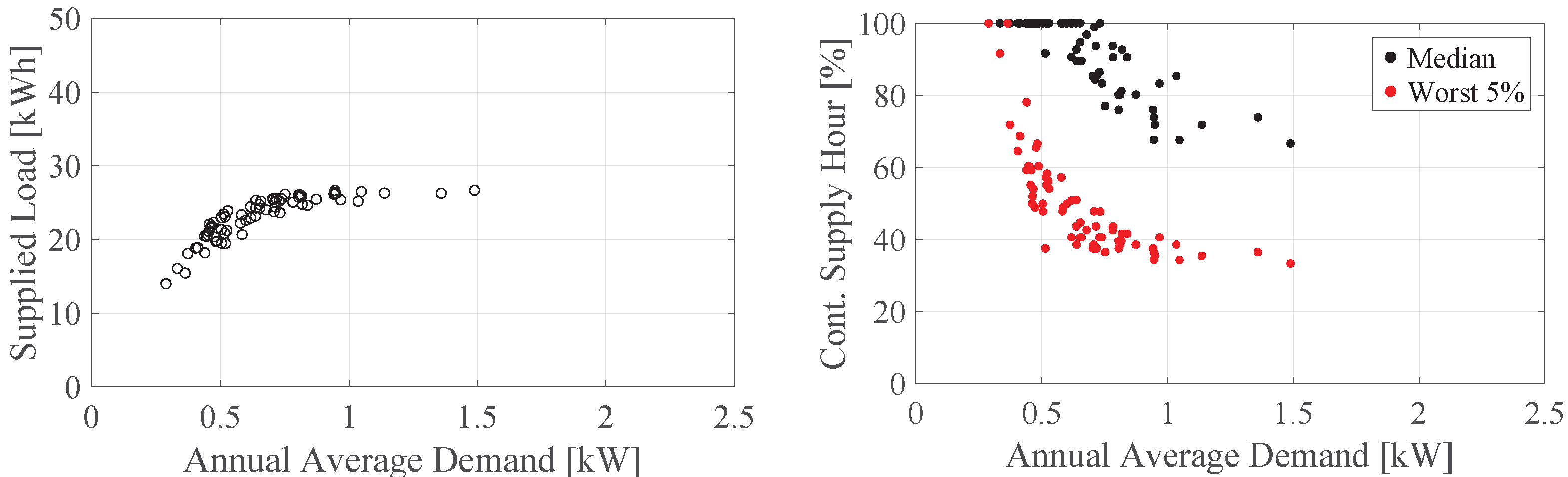

2.5.1. Outage Mitigation Effects

2.5.2. Economic Efficiency

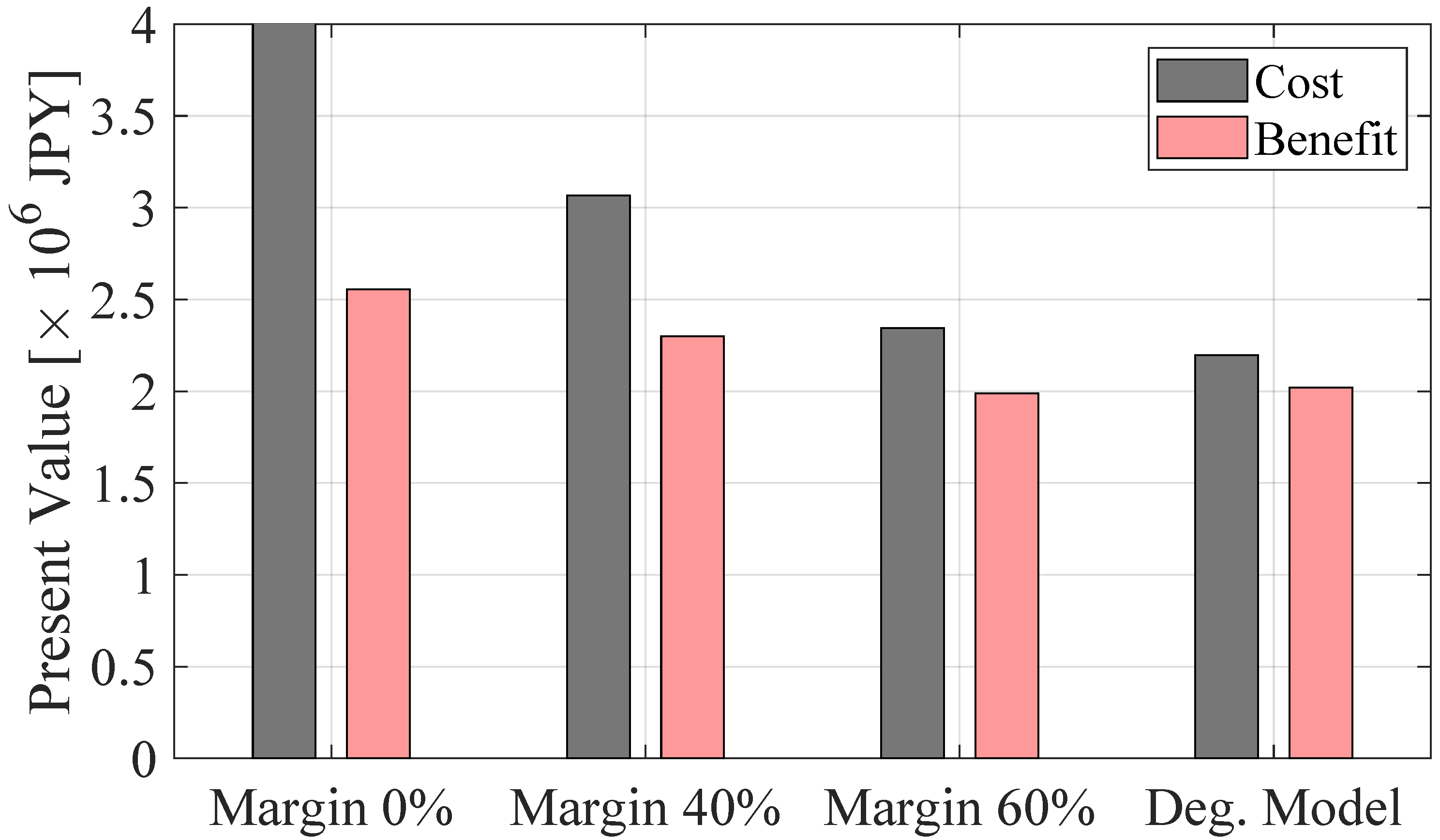

3. Result and Discussion

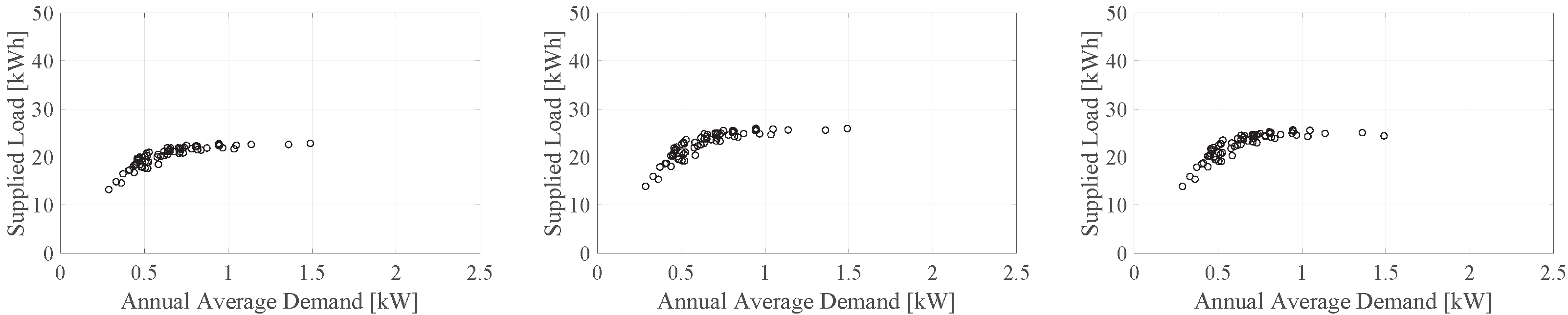

3.1. Operation in Normal States

3.2. Outage Simulation

3.3. Benefits with Outage Mitigation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Special Feature: Catastrophic and Frequent Torrential Rain. In White Paper on Disaster Management 2020; Cabinet Office in Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; pp. 6–10. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/en/documentation/white_paper/pdf/2020/SF1-1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Busby, J.W.; Baker, K.; Bazilian, M.D.; Gilbert, A.Q.; Grubert, E.; Rai, V.; Rhodes, J.D.; Shidore, S.; Smith, C.A.; Webber, M.E. Cascading risks: Understanding the 2021 winter blackout in Texas. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 77, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aki, H. Demand-Side Resiliency and Electricity Continuity: Experiences and Lessons Learned in Japan. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Special Feature: Consecutive Disasters--Toward the Establishment of a Disaster Conscious Society--. In White Paper on Disaster Management 2019; Cabinet Office in Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 22–33. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/en/documentation/white_paper/pdf/SF1-1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Japan. Energy White Paper 2024 (Summary) (FY2023 Annual Report on Energy). Available online: https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/whitepaper/pdf/2024_outline.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Khezri, R.; Mahmoudi, A.; Aki, H. Optimal planning of solar photovoltaic and battery storage systems for grid-connected residential sector: Review, challenges and new perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khafaf, N.; Rezaei, A.A.; Moradi Amani, A.; Jalili, M.; McGrath, B.; Meegahapola, L.; Vahidnia, A. Impact of battery storage on residential energy consumption: An Australian case study based on smart meter data. Renew. Energy 2022, 182, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, T.; Ozawa, A.; Wakamatsu, H. Profitability assessment of residential photovoltaic battery systems in japan using electric power big data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, F.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q. Optimization model for home energy management system of rural dwellings. Energy 2023, 283, 129039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T.; Ocampo, E.M.; Beza, T.M.; Kuo, C.C. Techno-Economic and Sizing Analysis of Battery Energy Storage System for Behind-the-Meter Application. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 203734–203746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, L.; Berardi, U. Hybrid solar energy systems with hydrogen and electrical energy storage for a single house and a midrise apartment in North America. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Xing, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, W. A home energy management system incorporating data-driven uncertainty-aware user preference. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 119911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Gough, R.; Radcliffe, J.; Marco, J.; Jennings, P. Techno-economic analysis of the viability of residential photovoltaic systems using lithium-ion batteries for energy storage in the United Kingdom. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alramlawi, M.; Gabash, A.; Mohagheghi, E.; Li, P. Optimal operation of hybrid PV-battery system considering grid scheduled blackouts and battery lifetime. Sol. Energy 2018, 161, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Nazari, M.H.; Hosseinian, S.H. Optimal Scheduling and Cost-Benefit Analysis of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Battery State of Health. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Baldick, R. Research on Resilience of Power Systems Under Natural Disasters—A Review. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 1604–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, A.; Abdollahi, A.; Rashidinejad, M. Multi-stage and resilience-based distribution network expansion planning against hurricanes based on vulnerability and resiliency metrics. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 136, 107640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglen, R.L.; Barth, J.; Gupta, S.; Kawai, E.; Klise, K.; Leibowicz, B.D. A nexus approach to infrastructure resilience planning under uncertainty. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 230, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cialdea, S.; Orr, J.A.; Emanuel, A.E. Outage avoidance and amelioration using battery energy storage systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, S.; Ding, T.; Lin, Y.; Shahidehpour, M. Multi-Stage Multi-Zone Defender-Attacker-Defender Model for Optimal Resilience Strategy with Distribution Line Hardening and Energy Storage System Deployment. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tang, W.; Ma, Z.; Huang, J. Equilibrium configuration strategy of vehicle-to-grid-based electric vehicle charging stations in low-carbon resilient distribution networks. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guikema, S.D.; Davidson, R.A.; Liu, H. Statistical models of the effects of tree trimming on power system outages. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2006, 21, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Trakas, D.N.; Mancarella, P.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Boosting the Power Grid Resilience to Extreme Weather Events Using Defensive Islanding. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 7, 2913–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P.; Trakas, D.N.; Kyriakides, E.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Metrics and Quantification of Operational and Infrastructure Resilience in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 4732–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shahidehpour, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Bie, Z. Microgrids for Enhancing the Power Grid Resilience in Extreme Conditions. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, E.; Mandal, P.; Sang, Y. Networked microgrids with roof-top solar PV and battery energy storage to improve distribution grids resilience to natural disasters. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 123, 106239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudbari, A.; Nateghi, A.; Yousefi-khanghah, B.; Asgharpour-Alamdari, H.; Zare, H. Resilience-oriented operation of smart grids by rescheduling of energy resources and electric vehicles management during extreme weather condition. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2021, 28, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Qiu, J.; Lin, J.; Yao, Z.; Liang, Q.; Lu, X. Planning of a multi-agent mobile robot-based adaptive charging network for enhancing power system resilience under extreme conditions. Appl. Energy 2025, 395, 126252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Hou, Y. Resilient Disaster Recovery Logistics of Distribution Systems: Co-Optimize Service Restoration with Repair Crew and Mobile Power Source Dispatch. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 6187–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkins, T.; Anderson, K.; Cutler, D.; Olis, D. Optimal Sizing of a Solar-Plus-Storage System For Utility Bill Savings and Resiliency Benefits. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 6–9 September 2016; Volume 9, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, W.; Barbose, G.; Miller, C.; White, P.; Carvallo, J.P.; Baik, S. Evaluating the potential for solar-plus-storage backup power in the United States as homes integrate efficient, flexible, and electrified energy technologies. Energy 2024, 304, 132180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, W.; Greer, D.; Lamb, K. The potential for using local PV to meet critical loads during hurricanes. Sol. Energy 2020, 205, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.M.; Ghosh, A.; Chopra, S.S. Power resilience enhancement of a residential electricity user using photovoltaics and a battery energy storage system under uncertainty conditions. Energies 2020, 13, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, J.; Zhong, H.; Rajagopal, R.; Xia, Q.; Kang, C. Reliability Value of Distributed Solar+Storage Systems Amidst Rare Weather Events. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 4476–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, M.; Mae, M.; Matsuhashi, R. Pilot Study on Residential Measures Against Unpredictable Outages with Batteries and Photovoltaics Considering Necessary Loads. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Istanbul, Turkiye, 10–12 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S. Resilient residential energy management with vehicle-to-home and photovoltaic uncertainty. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 132, 107206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Vlachokostas, A.; Kontou, E. Leveraging electric vehicles as a resiliency solution for residential backup power during outages. Energy 2025, 318, 134613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iino, Y.; Hayashi, Y. Distributed coordinated energy management system for DERs to realize cooperative resilience against blackout of power grid. In Proceedings of the 2022 61st Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers of Japan, SICE 2022, Kumamoto, Japan, 6–9 September 2022; pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Luo, F.; Dong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ranzi, G. Hierarchical energy management scheme for residential communities under grid outage event. IET Smart Grid 2020, 3, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Mu, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, S.; He, K.; Jia, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, J. Two-stage residential community energy management utilizing EVs and household load flexibility under grid outage event. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, W.; Barbose, G.; Carvallo, J.P.; Baik, S.; Miller, C.; White, P.; Praprost, M. County-level assessment of behind-the-meter solar and storage to mitigate long duration power interruptions for residential customers. Appl. Energy 2023, 342, 121166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Luo, F.; Mu, Y. Multi-stage energy management framework for residential communities using aggregated flexible energy resources in planned power outages. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 166, 110584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amada, K.; Kim, J.; Inaba, M.; Akimoto, M.; Kashihara, S.; Tanabe, S.-i. Feasibility of staying at home in a net-zero energy house during summer power outages. Energy Build. 2022, 273, 112352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, F.; Fujimoto, Y.; Hayashi, Y. Residential Battery Storage System Sizing for the Medically Vulnerable from the Life Continuity Planning Perspective: Toward Economic Operation Using Uncertain Photovoltaic Output. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 17, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.; Sanstad, A.H.; Hanus, N.; Eto, J.H.; Larsen, P.H. A hybrid approach to estimating the economic value of power system resilience. Electr. J. 2021, 34, 107013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, W. The quest to quantify the value of lost load: A critical review of the economics of power outages. Electr. J. 2022, 35, 107187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.; Davis, A.L.; Park, J.W.; Sirinterlikci, S.; Morgan, M.G. Estimating what US residential customers are willing to pay for resilience to large electricity outages of long duration. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, W.; Callaway, D. Do notifications affect households’ willingness to pay to avoid power outages? Evidence from an experimental stated-preference survey in California. Electr. J. 2024, 37, 107385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennemo, H.; Rosnes, O.; Skulstad, A. The cost to households of a large electricity outage. Energy Econ. 2022, 116, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Nam, H.; Cho, Y. Estimation of the inconvenience cost of a rolling blackout in the residential sector: The case of South Korea. Energy Policy 2015, 76, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, M.; Mae, M.; Matsuhashi, R. Investigation of Residential Value of Lost Load and the Importance of Electric Loads During Outages in Japan. Energies 2025, 18, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Laws, N.D.; Marr, S.; Lisell, L.; Jimenez, T.; Case, T.; Li, X.; Lohmann, D.; Cutler, D. Quantifying and Monetizing Renewable Energy Resiliency. Sustain. 2018, 10, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Meteorological Agency. Historical Weather Data and Download. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/risk/obsdl/index.php (accessed on 20 November 2025). (In Japanese)

- Japan Electric Power Exchange. Market Data. Available online: https://www.jepx.jp/en/electricpower/market-data/spot/ (accessed on 20 November 2025). (In Japanese).

- Lam, L.; Bauer, P. Practical Capacity Fading Model for Li-Ion Battery Cells in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 5910–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thingvad, A.; Marinelli, M. Influence of V2G Frequency Services and Driving on Electric Vehicles Battery Degradation in the Nordic Countries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of EVS 31 & EVTeC 2018, Kobe, Japan, 1–3 October 2018; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.O.; Kim, Y.S. Novel battery degradation cost formulation for optimal scheduling of battery energy storage systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 137, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Disaster Information. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/updates/index.html (accessed on 20 November 2025). (In Japanese)

- Organization for Cross-Regional Coordination of Transmission Operators, Japan. Outlook for Electricity Supply and Demand-Actual Data for FY 2022-I. Actual Electric Supply and Demand. Available online: https://www.occto.or.jp/en/information_disclosure/annual_report/files/2023_annualreport_240131.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan. Number of Customers for Lighting and Power demands. Available online: https://pdb.fepc.or.jp/pdb/%E4%B8%80%E8%88%AC_%E6%A4%9C%E7%B4%A2_%E9%9B%BB%E7%81%AF%E9%9B%BB%E5%8A%9B%E5%A5%91%E7%B4%84%E5%8F%A3%E6%95%B0_%E8%8B%B1%E8%AA%9E (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- The Headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion. Earthquake Occurring in the Nankai Trough. Available online: https://www.jishin.go.jp/regional_seismicity/rs_kaiko/k_nankai/ (accessed on 20 November 2025). (In Japanese).

- Hao, K.; Ialnazov, D.; Yamashiki, Y. GIS Analysis of Solar PV Locations and Disaster Risk Areas in Japan. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 815986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wu, J. Quantitative assessment method of typhoon-induced photovoltaic damage and energy production losses: A case study of the 2024 Typhoon Yagi. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2025, 16, 2569795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P. The grid: Stronger, bigger, smarter?: Presenting a conceptual framework of power system resilience. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2015, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; von Winterfeldt, D. A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiūnas, J.; Lund, P.D.; Mikkola, J. Energy system resilience – A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, E.; Anderson, K.; Bazilian, M.D. Planning for a resilient home electricity supply system. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 133774–133785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda Power Equipment. Honda Generators: EU2200i Model. 2025. Available online: https://powerequipment.honda.com/generators/models/eu2200i (accessed on 4 December 2025).

| −4.092 × 10−4 | −2.167 | 1.408 × 10−5 | 6.130 |

| Symbol | Definition | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| t | Time Slot | [-] |

| Variables | ||

| Total cost | [] | |

| Supply from grid | [] | |

| Sold excess electricity to grid | [] | |

| Consumption at battery charge | [] | |

| Supply from battery discharge | [] | |

| Battery charging state | 0 or 1 | |

| Battery state of charge (SoC) | [-] | |

| Battery degradation amount | [-] | |

| Constants | ||

| Electricity variable price | [] | |

| Excess electricity price | [] | |

| Demand | [] | |

| PV generation | [] | |

| Maximum supply from grid | [] | |

| Maximum output at battery | [] | |

| Minimum SoC | [-] | |

| Maximum SoC | [-] | |

| SoC margin | [-] | |

| Battery capacity | [] | |

| Battery charge/discharge efficiency | [-] | |

| Battery equipment cost | [] | |

| Battery capacity rate at the end of lifespan | [-] | |

| Linearized degradation curve | [-] |

| Name (Year) | Outage Households | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Typhoon No. 16 (2004) | 559,000 (total) | 1 day |

| Typhoon No. 18 (2004) | 340,300 (total) | 2 days |

| Typhoon No. 23 (2004) | 369,000 (total) | 5 days |

| Heavy snowfall (2006) | 697,200 (total) | 4.5 h |

| Typhoon No. 18 (2009) | 153,000 (total) | 36 h |

| Typhoon No. 12 (2011) | 194,000 (total) | 9 days |

| Typhoon No. 11 & 12 (2014) | 105,280 (total) | <1 day |

| Typhoon No. 21 (2017) | 108,320 (maximum) | 3 days |

| Earthquake in North Osaka (2018) | 170,300 (maximum) | 50 min |

| Typhoon No. 20 (2018) | 149,000 (maximum) | 14.5 h |

| Typhoon No. 21 (2018) | 1,700,000 (maximum) | 5 days |

| Cause | Duration | Season | Initial SoC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typhoons | 48 h | Summer | (90%) |

| Earthquakes | 48 h | Summer | in normal operations |

| Snowfalls | 48 h | Winter | (90%) |

| Case | Elec. Cost (Diff.) [JPY] | Degradation [%/Year] |

|---|---|---|

| No PV/BESS | 225,500 (–) | – |

| Margin 0% | 69,890 (−155,610) | 9.55 |

| Margin 40% | 87,250 (−138,250) | 2.88 |

| Margin 60% | 108,780 (−116,720) | 1.93 |

| Deg. Model | 106,540 (−118,960) | 1.67 |

| Outage Frequency | Total Proportion [%] |

|---|---|

| 0 | 25.7 |

| 0.13 times/year | 37.9 |

| 0.33 times/year | 47.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matsubara, M.; Mae, M.; Matsuhashi, R. Comprehensive Benefit Evaluation of Residential Solar and Battery Systems in Japan Considering Outage Mitigation and Battery Degradation. Energies 2025, 18, 6579. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246579

Matsubara M, Mae M, Matsuhashi R. Comprehensive Benefit Evaluation of Residential Solar and Battery Systems in Japan Considering Outage Mitigation and Battery Degradation. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6579. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246579

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatsubara, Masashi, Masahiro Mae, and Ryuji Matsuhashi. 2025. "Comprehensive Benefit Evaluation of Residential Solar and Battery Systems in Japan Considering Outage Mitigation and Battery Degradation" Energies 18, no. 24: 6579. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246579

APA StyleMatsubara, M., Mae, M., & Matsuhashi, R. (2025). Comprehensive Benefit Evaluation of Residential Solar and Battery Systems in Japan Considering Outage Mitigation and Battery Degradation. Energies, 18(24), 6579. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246579