Renewable Hydrogen from Biohybrid Systems: A Bibliometric Review of Technological Trends and Applications in the Energy Transition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Bibliometric Analysis

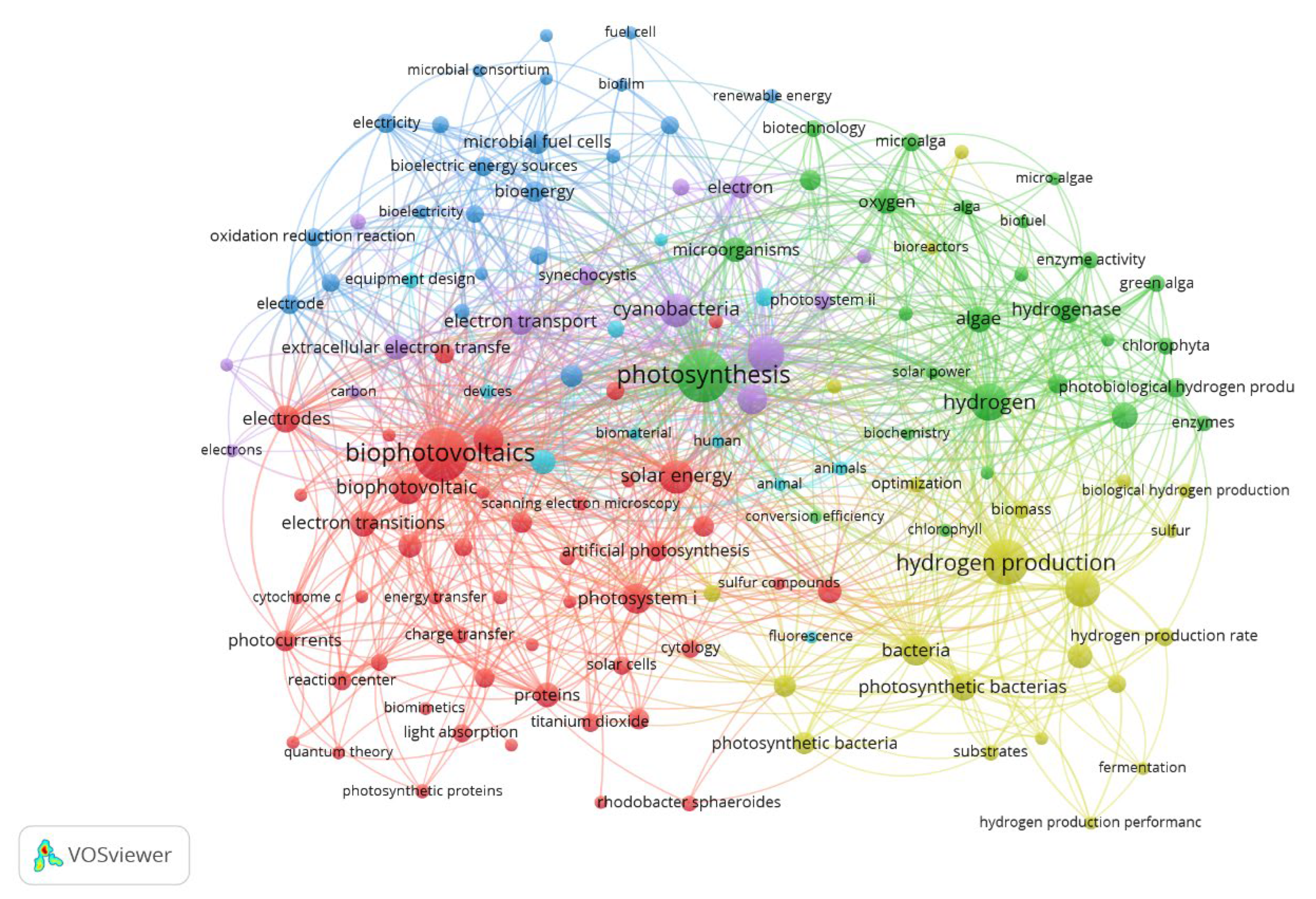

- Construction of the Keyword Co-occurrence Network: A co-occurrence network was designed to identify the most frequent terms and their interrelationships within the study field. Key nodes such as “hydrogen production,” “biohybrid system,” and “nanomaterials” were highlighted, reflecting their significance in the research. VOSviewer was used to visualize these connections and to measure the centrality and frequency of terms based on established bibliometric approaches.

- Geographical Distribution Analysis of Research: The territorial distribution of scientific output was examined by identifying the countries and institutions with the most publications. These contributions were graphically represented, and the factors influencing each region’s research capacity were analyzed using comparable bibliometric methodologies.

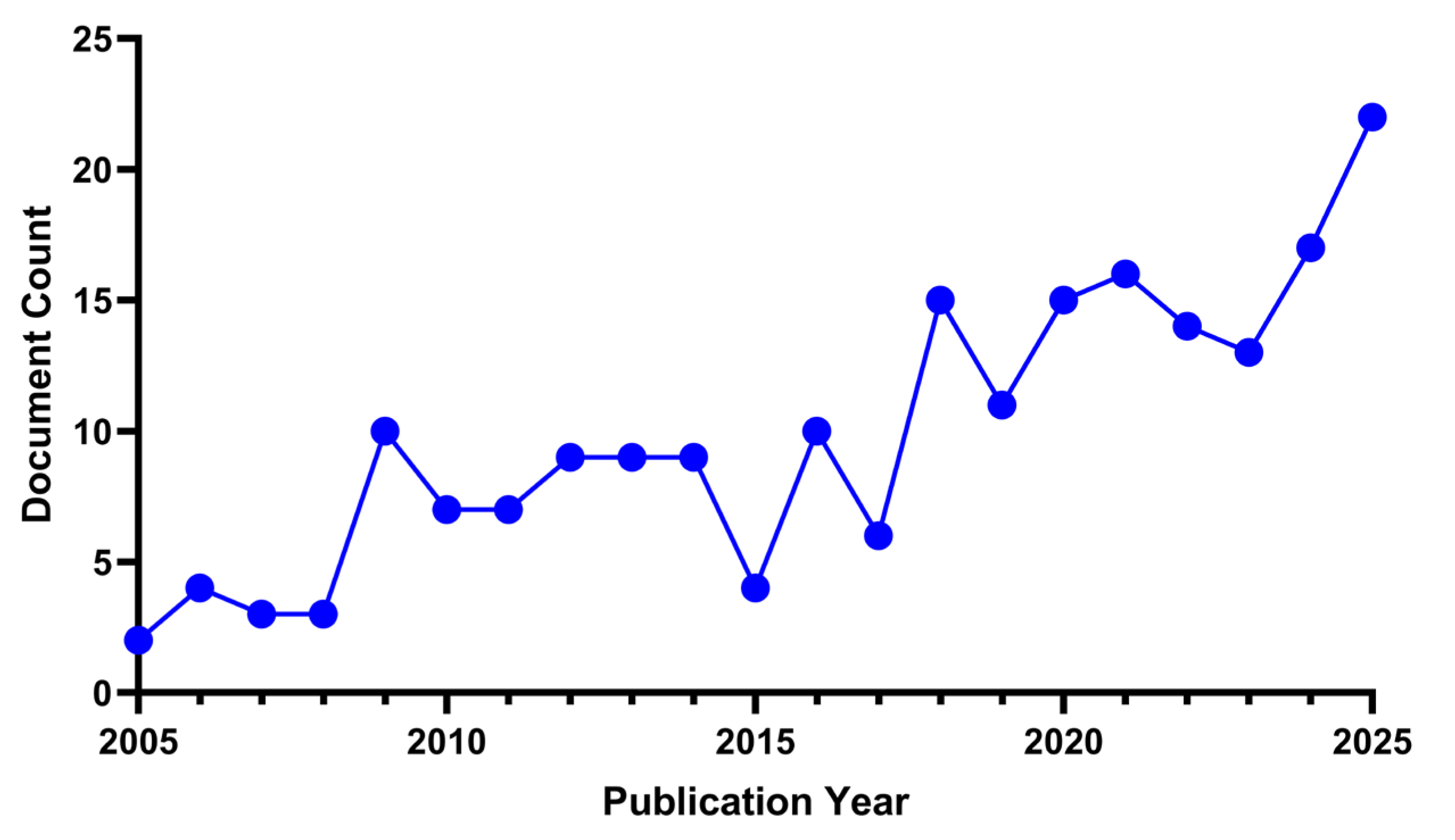

- Temporal Evolution of Publications: The publication trajectory was examined to detect changes in scientific activity. Time-series analyses were employed to assess the number of publications per year and identify factors driving increases or decreases in academic output.

3. Evolution and Trends in Hydrogen Production Using Bio-Hybrids

3.1. Growth in Scientific Production

3.2. Geographic Distribution and International Collaborations

3.3. Co-Occurrence Analysis and Thematic Clustering in Biohybrid Hydrogen Production Systems

3.4. Evolution of Knowledge in Biohybrid Systems for Solar Fuels and Hydrogen: Temporal Dynamics and External Influences

3.5. Co-Citation Network Analysis in Biohybrid Systems for Hydrogen Production: Structural Patterns and Knowledge Evolution

3.6. Overview of the Most Influential Literature on Biohybrid Systems for Renewable Hydrogen

3.7. Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gani, A. Fossil Fuel Energy and Environmental Performance in an Extended STIRPAT Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Klingmüller, K.; Pozzer, A.; Burnett, R.T.; Haines, A.; Ramanathan, V. Effects of Fossil Fuel and Total Anthropogenic Emission Removal on Public Health and Climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7192–7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, C.; Singh, A.; Singh, P.; Singh, A. Anaerobic Digestion of Agri-Food Wastes for Generating Biofuels. Indian J. Microbiol. 2021, 61, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain Bhuiyan, M.M.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Production, Storage, and Transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Hernández, T.J.; Obando-Ulloa, J.M.; Álvarez de Eulate, X.; Ilundain-López, R.; Juan-Pérez, P.; Castro-Badilla, G. Evaluación de Sistemas Térmicos y Fotovoltaicos Solares en Tres Plantas Procesadoras de Leche de la Región Huetar Norte, Costa Rica. Rev. Tecnol. Marcha 2020, 33, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, K.K.; Gopan, G.; Pattanayak, S. Overview of Hydrogen Production Processes: Health and Environmental Impact. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2025, e70229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łosiewicz, B. Technology for Green Hydrogen Production: Desk Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermesmann, M.; Müller, T.E. Green, Turquoise, Blue, or Grey? Environmentally Friendly Hydrogen Production in Transforming Energy Systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 90, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolo, I.; Costa, V.A.F.; Brito, F.P. Hydrogen-Based Energy Systems: Current Technology Development Status, Opportunities and Challenges. Energies 2023, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, H.; Dincer, I.; Crawford, C. A Review on Hydrogen Production and Utilization: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 26238–26264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay-Roger, R.; Bach, W.; Bobadilla, L.F.; Reina, T.R.; Odriozola, J.A.; Amils, R.; Blay, V. Natural Hydrogen in the Energy Transition: Fundamentals, Promise, and Enigmas. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green-Hydrogen-Market-Size-Share-Trends-Analysis. Available online: https://www.gii.tw/report/grvi1588623-green-hydrogen-market-size-share-trends-analysis.html (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Abbasian Hamedani, E.; Alenabi, S.A.; Talebi, S. Hydrogen as an Energy Source: A Review of Production Technologies and Challenges of Fuel Cell Vehicles. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 3778–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, F.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; Chang, J.-S.; Ho, S.-H. Biohydrogen Production from Microalgae for Environmental Sustainability. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehariya, S.; Fratini, F.; Lavecchia, R.; Zuorro, A. Green Extraction of Value-Added Compounds Form Microalgae: A Short Review on Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) and Related Pre-Treatments. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuorro, A.; Miglietta, S.; Familiari, G.; Lavecchia, R. Enhanced Lipid Recovery from Nannochloropsis Microalgae by Treatment with Optimized Cell Wall Degrading Enzyme Mixtures. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 212, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergel-Suarez, A.H.; García-Martínez, J.B.; López-Barrera, G.L.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Zuorro, A. Impact of Biomass Drying Process on the Extraction Efficiency of C-Phycoerythrin. BioTech 2023, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergel-Suarez, A.H.; García-Martínez, J.B.; López-Barrera, G.L.; Urbina-Suarez, N.A.; Barajas-Solano, A.F. Influence of Critical Parameters on the Extraction of Concentrated C-PE from Thermotolerant Cyanobacteria. BioTech 2024, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Gonzalez-Delgado, A.D.; Kafarov, V. Effect of Thermal Pre-Treatment on Fermentable Sugar Production of Chlorella Vulgaris. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2014, 37, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, J.B.; Sanchez-Tobos, L.P.; Carvajal-Albarracín, N.A.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Barajas-Ferreira, C.; Kafarov, V.; Zuorro, A. The Circular Economy Approach to Improving CNP Ratio in Inland Fishery Wastewater for Increasing Algal Biomass Production. Water 2022, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloupakis, E.; Faraloni, C.; Silva Benavides, A.M.; Torzillo, G. Recent Achievements in Microalgal Photobiological Hydrogen Production. Energies 2021, 14, 7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, R.K.; Subramanian, D.; Pandian, S.; Krishna, S. A Review of Different Technologies to Produce Fuel from Microalgal Feedstock. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xue, D.; Wang, C.; Fang, D.; Cao, L.; Gong, C. Genetic Engineering for Biohydrogen Production from Microalgae. iScience 2023, 26, 107255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Tsigkou, K.; Elsamahy, T.; Pispas, K.; Sun, J.; Manthos, G.; Schagerl, M.; Sventzouri, E.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Kornaros, M.; et al. Recent Advances in Sustainable Hydrogen Production from Microalgae: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 270, 115908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, Z.; Malekshahi, P.; Morowvat, M.H.; Trzcinski, A.P. A Review of Bioreactor Configurations for Hydrogen Production by Cyanobacteria and Microalgae. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 472–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.d.O.; Camargo-Santos, D.; Zorzal-Almeida, S. Microalgas e Cianobactérias Continentais no Estado do Espírito Santo: Passado, Presente e Futuro. Oecologia Aust. 2022, 26, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bai, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, N.; Cui, D.; Zhao, M. Low-Toxicity Self-Photosensitized Biohybrid Systems for Enhanced Light-Driven H2 Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Peng, Y.; Ma, W.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; Tang, R. Microalgae–Material Hybrid for Enhanced Photosynthetic Energy Conversion: A Promising Path towards Carbon Neutrality. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, A. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Content Analysis: Guidelines and Contributions of Content Co-occurrence or Co-word Literature Reviews. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O.; Kocaman, R.; Kanbach, D.K. How to Design Bibliometric Research: An Overview and a Framework Proposal. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. How to Combine and Clean Bibliometric Data and Use Bibliometric Tools Synergistically: Guidelines Using Metaverse Research. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G.; Balzano, M.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M.M. Guidelines for Bibliometric-Systematic Literature Reviews: 10 Steps to Combine Analysis, Synthesis and Theory Development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2025, 27, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, M. A Comprehensive Approach to Preprocessing Data for Bibliometric Analysis. Scientometrics 2025, 130, 5191–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narcis, R.; Viorel, C.; Andrei Constantin, T. Bibliometric Analysis with Vosviewer: Research Trends in Sport Management Within European Football. Discobolul—Phys. Educ. Sport Kinetother. J. 2024, 63, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turatto, F.; Mazzalai, E.; Pagano, F.; Migliara, G.; Villari, P.; De Vito, C. A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of the Scientific Literature on the Early Phase of COVID-19 in Italy. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 666669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narong, D.K.; Hallinger, P. A Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis of Research on Service Learning: Conceptual Foci and Emerging Research Trends. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cader, J.; Koneczna, R.; Olczak, P. The Impact of Economic, Energy, and Environmental Factors on the Development of the Hydrogen Economy. Energies 2021, 14, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snousy, M.G.; Abouelmagd, A.R.; Alexakis, D.E.; Helmy, H.M.; Moustafa, Y.M.; Negm, A.; Weiss, E.; Weiss, R.; Ismail, E.; Sakr, S.M.; et al. Dark Fermentative Biohydrogen Production: Bibliometric Trends, Techno-Economic Insights, Emerging Challenges, and Sustainable Pathways. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 186, 152042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, S.H.; Mat Yatim, N.S.; Jehan Elham, O.S.; Shaari, N.; Zakaria, Z. Three Decades of Hydrogen Energy Research: A Bibliometric Analysis on the Evolution of Green Hydrogen Technologies. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 3182–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Haunschild, R.; Mutz, R. Growth Rates of Modern Science: A Latent Piecewise Growth Curve Approach to Model Publication Numbers from Established and New Literature Databases. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Mutz, R. Growth Rates of Modern Science: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on the Number of Publications and Cited References. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, L.; Comas, D.; Escorcia, Y.C.; Alviz-Meza, A.; Carrillo Caballero, G.; Portnoy, I. Bibliometric Analysis of Global Trends around Hydrogen Production Based on the Scopus Database in the Period 2011–2021. Energies 2022, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpo-Gebera, O.; Limaymanta, C.H.; Sanz-Casado, E. Producción Científica y Tecnológica de Perú en el Contexto Sudamericano: Un Análisis Cienciométrico. Prof. Inf. 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arias, P.; Antón-Sancho, Á.; Lampropoulos, G.; Vergara, D. On Green Hydrogen Generation Technologies: A Bibliometric Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; You, L.; Deng, P.; Jiang, X.; Hsu, H.-H. Self-Assembled Biohybrid: A Living Material To Bridge the Functions between Electronics and Multilevel Biological Modules/Systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 32289–32298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Li, J. Bioenergy Research under Climate Change: A Bibliometric Analysis from a Country Perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 26427–26440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoi-Yorke, F.; Agyekum, E.B.; Tahir, M.; Abbey, A.A.; Jangir, P.; Rashid, F.L.; Togun, H.; Mbasso, W.F. Review of the Trends, Evolution, and Future Research Directions of Green Hydrogen Production from Wastewaters—Systematic and Bibliometric Approach. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 25, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaiza, M.Y.D.; Al-Yazeedi, A.-A.; Al Wahaibi, T.; Mjalli, F.; Abubakar, A.; El Hameed, M.A.; Siddique, M.J. Global Research Trends in Catalysis for Green Hydrogen Production from Wastewater: A Bibliometric Study (2010–2024). Catalysts 2025, 15, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Lai, K.; Bao, J.; Xie, K.; Yu, Y. Hydrogen Regulates Mitochondrial Quality to Protect Glial Cells and Alleviates Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy by Nrf2/YY1 Complex Promoting HO-1 Expression. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 118, 110009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roucham, B.; Zaghdoud, O. Mapping Green Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Research in Extended BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and Others): A Bibliometric Approach with a Future Agenda. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, E.; Vlasov, M.; Strielkowski, W.; Faminskaya, M.; Kharchenko, K. Digitalization of the Energy Sector in Its Transition towards Renewable Energy: A Role of ICT and Human Capital. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, B.; Jalilnejad, E.; Ghasemzadeh, K.; Iulianelli, A. Recent Progresses in Application of Membrane Bioreactors in Production of Biohydrogen. Membranes 2019, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Aburto, C.; Poma-García, J.; Montaño-Pisfil, J.; Morcillo-Valdivia, P.; Oyanguren-Ramirez, F.; Santos-Mejia, C.; Rodriguez-Flores, R.; Virú-Vasquez, P.; Pilco-Nuñez, A. Bibliometric Analysis of Global Publications on Management, Trends, Energy, and the Innovation Impact of Green Hydrogen Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umunnawuike, C.; Mahat, S.Q.A.; Ridzuan, N.; Gbonhinbor, J.; Agi, A. Biohydrogen Production: A Review of Current Trends and Future Prospects. In Proceedings of the SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition, Lagos, Nigeria, 5 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- GOV UK. UK Hydrogen Strategy; Dandy Booksellers Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781528626705. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. The Netherlands 2020—Energy Policy Review. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/93f03b36-64a9-4366-9d5f-0261d73d68b3/The_Netherlands_2020_Energy_Policy_Review.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Guo, H.; Teng, Z.; Han, H.; Li, T. Biohydrogen Production from Saline Wastewater: An Overview. Clean. Energy Sci. Technol. 2024, 2, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wu, P. Hydrogen Policy Evolution in China and Globally: A Spatial and Thematic Comparison. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; He, L.; Wen, W.; Feng, Y. Hydrogenase and Nitrogenase: Key Catalysts in Biohydrogen Production. Molecules 2023, 28, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMWK. Import Strategy for Hydrogen and Hydrogen Derivatives. Available online: https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Energie/importstrategy-hydrogen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=7 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Ahmad, W.; Samara, F. Biohydrogen Production from Waste Materials: Mini-Review. Trends Ecol. Indoor Environ. Eng. 2023, 1, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, E.B.; Odoi-Yorke, F. Review of over Two Decades of Research on Dark and Photo Fermentation for Biohydrogen Production—A Combination of Traditional, Systematic, and Bibliometric Approaches. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 91, 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiyasa, M.; Mardiyana, D.; Islami, L.A. Bibliometric Green and Hidrogen. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 148, 02032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Kavitha, S.; Kannah, Y.; Yogalakshmi, K.N.; Sivashanmugam, P.; Bhatnagar, A.; Kumar, G. A Critical Review on Limitations and Enhancement Strategies Associated with Biohydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 16565–16590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.S.-L.; Fan, H.; Enshaei, H.; Zhang, W.; Shi, W.; Abdussamie, N.; Miwa, T.; Qu, Z.; Yang, Z. A Review on Ports’ Readiness to Facilitate International Hydrogen Trade. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 17351–17369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-E. Hydrogen Technology Development and Policy Status by Value Chain in South Korea. Energies 2022, 15, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawalo, M.; Pikoń, K.; Landrat, M.; Ścierski, W. Hydrogen Production from Biowaste: A Systematic Review of Conversion Technologies, Environmental Impacts, and Future Perspectives. Energies 2025, 18, 4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.K.M.K.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; Hewitt, N.J.; Lenihan, R.; Brandoni, C. Bio-Hydrogen Production from Wastewater: A Comparative Study of Low Energy Intensive Production Processes. Clean Technol. 2021, 3, 156–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Torriero, A.A.J. Biohydrogen—A Green Fuel for Sustainable Energy Solutions. Energies 2022, 15, 7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Shi, L.; Ding, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y. Study on China’s Renewable Energy Policy Reform and Improved Design of Renewable Portfolio Standard. Energies 2019, 12, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordensvard, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X. Innovation Core, Innovation Semi-Periphery and Technology Transfer: The Case of Wind Energy Patents. Energy Policy 2018, 120, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umunnawuike, C.; Mahat, S.Q.A.; Nwaichi, P.I.; Money, B.; Agi, A. Biohydrogen Production for Sustainable Energy Transition: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review of the Reaction Mechanisms, Challenges, Knowledge Gaps and Emerging Trends. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 188, 107345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimbrathodi, S.P.; Javed, M.A.; Hamouda, M.A.; Aly Hassan, A.; Ahmed, M.E. BioH2 Production Using Microalgae: Highlights on Recent Advancements from a Bibliometric Analysis. Water 2023, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraloni, C.; Torzillo, G.; Balestra, F.; Moia, I.C.; Zampieri, R.M.; Jiménez-Conejo, N.; Touloupakis, E. Advances and Challenges in Biohydrogen Production by Photosynthetic Microorganisms. Energies 2025, 18, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefalew, T.; Tilinti, B.; Betemariyam, M. The Potential of Biogas Technology in Fuelwood Saving and Carbon Emission Reduction in Central Rift Valley, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, M.; Yirga, F.; Alemu, G.; Azadi, H. Status of Energy Utilization and Factors Affecting Rural Households’ Adoption of Biogas Technology in North-Western Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, C.; Kropp, A.; Vincent, K.; Grinter, R. Developing High-Affinity, Oxygen-Insensitive [NiFe]-Hydrogenases as Biocatalysts for Energy Conversion. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2023, 51, 1921–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shao, Z.; Zou, Q.; Pan, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, R.; Ge, T. An Atmospheric Water Harvesting System Based on the “Optimal Harvesting Window” Design for Worldwide Water Production. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, B.; Kumagai, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Sugiyama, M. Techno-Economic Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production in Australia Using Off-Grid Hybrid Resources of Solar and Wind. Energies 2025, 18, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Khan, A.A.; Ali, M.A.S.; Yu, J. An Evaluation of Influencing Factors and Public Attitudes for the Adoption of Biogas System in Rural Communities to Overcome Energy Crisis: A Case Study of Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, L.-N.; Tian, H.; Cooper, A.I.; Sprick, R.S. Making the Connections: Physical and Electric Interactions in Biohybrid Photosynthetic Systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4305–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, D.; Bhattacharya, R.; Mukherjee, A. Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends in Microbial Fuel Cells for Wastewater Treatment. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 202, 109155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathan, A.S. Microbial Fuel Cells: A Comprehensive Review for Beginners. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonoff, R.E.; Ochoa, G.V.; Cardenas-Escorcia, Y.; Silva-Ortega, J.I.; Meriño-Stand, L. Research Trends in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells during 2008–2018: A Bibliometric Analysis. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabgan, W.; Nabgan, B.; Jalil, A.A.; Ikram, M.; Hussain, I.; Bahari, M.B.; Tran, T.V.; Alhassan, M.; Owgi, A.H.K.; Parashuram, L.; et al. A Bibliometric Examination and State-of-the-Art Overview of Hydrogen Generation from Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva Canu, I.; Plys, E.; Velarde Crézé, C.; Fito, C.; Hopf, N.B.; Progiou, A.; Riganti, C.; Sauvain, J.-J.; Squillacioti, G.; Suarez, G.; et al. A Harmonized Protocol for an International Multicenter Prospective Study of Nanotechnology Workers: The NanoExplore Cohort. Nanotoxicology 2023, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Gu, W.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, C.; Gao, J.; Zhou, S. Toward Next-Generation Semiartificial Photosynthesis: Multidisciplinary Engineering of Biohybrid Systems. Chem. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisriel, C.J.; Malavath, T.; Qiu, T.; Menzel, J.P.; Batista, V.S.; Brudvig, G.W.; Utschig, L.M. Structure of a Biohybrid Photosystem I-Platinum Nanoparticle Solar Fuel Catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltman, L.; Van Eck, N.J.; Noyons, E.C. A Unified Approach to Mapping and Clustering of Bibliometric Networks. J. Informetr. 2010, 4, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Flores, S.; Ramirez-Asis, E.; Delgado-Caramutti, J.; Nazario-Naveda, R.; Gallozzo-Cardenas, M.; Diaz, F.; Delfin-Narcizo, D. An Analysis of Global Trends from 1990 to 2022 of Microbial Fuel Cells: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-T.; Li, L.-A.; Tsou, T.-C.; Wang, S.-L.; Lee, H.-L.; Shih, T.-S.; Liou, S.-H. Longitudinal Follow-up of Health Effects among Workers Handling Engineered Nanomaterials: A Panel Study. Environ. Health 2019, 18, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, C.; Fernández Méndez, J.; Berggren, G.; Lindblad, P. Novel Concepts and Engineering Strategies for Heterologous Expression of Efficient Hydrogenases in Photosynthetic Microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1179607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate-Neutral Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/attachment/865942/EU_Hydrogen_Strategy.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Shan, B.; Broza, Y.Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gui, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Multiplexed Nanomaterial-Based Sensor Array for Detection of COVID-19 in Exhaled Breath. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12125–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulay, E.D.; Ozgur Colpan, C.; Ezan, M.A. Techno-Economic Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production in Izmir: Evaluating Electrolyzer Technologies, Modularization Strategies, and Renewable Energy Integration. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 333, 119797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Chen, Q.; Li, W.; Yu, X.; Zhong, Q. Decorating Cu2O with Ni-Doped Metal Organic Frameworks as Efficient Photocathodes for Solar Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 17065–17073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, A. Green Algae as Fuel Factores. Green. Chem. 2000, 2, G35–G41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosourov, S.; Tsygankov, A.; Seibert, M.; Ghirardi, M.L. Sustained Hydrogen Photoproduction by Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Effects of Culture Parameters. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2002, 78, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, O.; Rupprecht, J.; Mussgnug, J.H.; Dismukes, G.C.; Hankamer, B. Photosynthesis: A Blueprint for Solar Energy Capture and Biohydrogen Production Technologies. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2005, 4, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srirangan, K.; Pyne, M.E.; Perry Chou, C. Biochemical and Genetic Engineering Strategies to Enhance Hydrogen Production in Photosynthetic Algae and Cyanobacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 8589–8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, D.; Lee, D.-J.; Kondo, A.; Chang, J.-S. Recent Insights into Biohydrogen Production by Microalgae—From Biophotolysis to Dark Fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 227, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krassen, H.; Schwarze, A.; Friedrich, B.; Ataka, K.; Lenz, O.; Heberle, J. Photosynthetic Hydrogen Production by a Hybrid Complex of Photosystem I and [NiFe]-Hydrogenase. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 4055–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stripp, S.T.; Goldet, G.; Brandmayr, C.; Sanganas, O.; Vincent, K.A.; Haumann, M.; Armstrong, F.A.; Happe, T.; Buchanan, B.B. How Oxygen Attacks [FeFe] Hydrogenases from Photosynthetic Organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17331–17336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipps, G.; Happe, T.; Hemschemeier, A. Nitrogen Deprivation Results in Photosynthetic Hydrogen Production in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Planta 2012, 235, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, A.J.; Bombelli, P.; Bradley, R.W.; Thorne, R.; Wenzel, T.; Howe, C.J. Biophotovoltaics: Oxygenic Photosynthetic Organisms in the World of Bioelectrochemical Systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1092–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mershin, A.; Matsumoto, K.; Kaiser, L.; Yu, D.; Vaughn, M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Bruce, B.D.; Graetzel, M.; Zhang, S. Self-Assembled Photosystem-I Biophotovoltaics on Nanostructured TiO2 and ZnO. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschörtner, J.; Lai, B.; Krömer, J.O. Biophotovoltaics: Green Power Generation from Sunlight and Water. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetkorn, W.; Rastogi, R.P.; Incharoensakdi, A.; Lindblad, P.; Madamwar, D.; Pandey, A.; Larroche, C. Microalgal Hydrogen Production—A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 1194–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Lv, Y.; Liu, Y. A New Hydrogen-Producing Strain and Its Characterization of Hydrogen Production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 177, 1676–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oey, M.; Sawyer, A.L.; Ross, I.L.; Hankamer, B. Challenges and Opportunities for Hydrogen Production from Microalgae. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, B.J. An Overview of Hydrogen in the Subsurface. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 8, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posewitz, M.C.; Smolinski, S.L.; Kanakagiri, S.; Melis, A.; Seibert, M.; Ghirardi, M.L. Hydrogen Photoproduction Is Attenuated by Disruption of an Isoamylase Gene in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2151–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Cestellos-Blanco, S.; Kim, J.M.; Shen, Y.X.; Kong, Q.; Lu, D.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Yang, P. Close-Packed Nanowire-Bacteria Hybrids for Efficient Solar-Driven CO2 Fixation. Joule 2020, 4, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabiev, I.; Rakovich, A.; Sukhanova, A.; Lukashev, E.; Zagidullin, V.; Pachenko, V.; Rakovich, Y.P.; Donegan, J.F.; Rubin, A.B.; Govorov, A.O. Fluorescent Quantum Dots as Artificial Antennas for Enhanced Light Harvesting and Energy Transfer to Photosynthetic Reaction Centers. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7217–7221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalena, F.; Senatore, A.; Tursi, A.; Basile, A. Bioenergy Production from Second- and Third-Generation Feedstocks. In Bioenergy Systems for the Future; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 559–599. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, M.; Lou, S.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Hu, Z. Recent Advancement and Strategy on Bio-Hydrogen Production from Photosynthetic Microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 121972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Li, A.; Han, J.; Wang, X. Biohybrid Molecule-Based Photocatalysts for Water Splitting Hydrogen Evolution. Chempluschem 2023, 88, e202200424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoveská, L.; Nielsen, S.L.; Eroldoğan, O.T.; Haznedaroglu, B.Z.; Rinkevich, B.; Fazi, S.; Robbens, J.; Vasquez, M.; Einarsson, H. Overview and Challenges of Large-Scale Cultivation of Photosynthetic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Mabe, T.; Zhang, W.; Bagra, B.; Ji, Z.; Yin, Z.; Allado, K.; Wei, J. Plasmon–Exciton Coupling in Photosystem I Based Biohybrid Photoelectrochemical Cells. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.W. Designing Interfaces of Hydrogenase–Nanomaterial Hybrids for Efficient Solar Conversion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Bioenerg. 2013, 1827, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Haas, R.; Boydas, E.B.; Roemelt, M.; Happe, T.; Apfel, U.-P.; Stripp, S.T. Oxygen Sensitivity of [FeFe]-Hydrogenase: A Comparative Study of Active Site Mimics inside vs. Outside the Enzyme. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 19105–19116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Sun, P.; Li, Z.; Song, K.; Su, W.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J. A Surface-Display Biohybrid Approach to Light-Driven Hydrogen Production in Air. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaap9253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; He, Z. Light-Driven Carbon Dioxide Reduction to Methane by Methanosarcina Barkeri-CdS Biohybrid. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 257, 117916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stripp, S.T.; Happe, T. How Algae Produce Hydrogen—News from the Photosynthetic Hydrogenase. Dalton Trans. 2009, 45, 9960–9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Huang, H.; Kahnt, J.; Mueller, A.P.; Köpke, M.; Thauer, R.K. NADP-Specific Electron-Bifurcating [FeFe]-Hydrogenase in a Functional Complex with Formate Dehydrogenase in Clostridium Autoethanogenum Grown on CO. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 4373–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloshin, R.A.; Kreslavski, V.D.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Bedbenov, V.S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Photoelectrochemical Cells Based on Photosynthetic Systems: A Review. Biofuel Res. J. 2015, 2, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Shuai, D.; Shen, Y.; Xiong, W.; Wang, L. Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4)-Based Photocatalysts for Water Disinfection and Microbial Control: A Review. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Reisner, E. Advancing Photosystem II Photoelectrochemistry for Semi-Artificial Photosynthesis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampelli, C.; Giusi, D.; Miceli, M.; Merdzhanova, T.; Smirnov, V.; Chime, U.; Astakhov, O.; Martín, A.J.; Veenstra, F.L.P.; Pineda, F.A.G.; et al. An Artificial Leaf Device Built with Earth-Abundant Materials for Combined H2 Production and Storage as Formate with Efficiency > 10%. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 1644–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapdan, I.K.; Kargi, F. Bio-Hydrogen Production from Waste Materials. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2006, 38, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, M.; Gamache, M.T.; Redman, H.J.; Land, H.; Senger, M.; Berggren, G. Light-Driven [FeFe] Hydrogenase Based H2 Production in E. Coli: A Model Reaction for Exploring E. coli Based Semiartificial Photosynthetic Systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 10760–10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forastier, M.E.; Zalocar, Y.; Andrinolo, D.; Domitrovic, H.A. Presencia y Toxicidad de Microcystis aeruginosa (Cianobacteria) en el Río Paraná, Aguas Abajo de la Represa Yacyretá (Argentina). Rev. Biol. Trop. 2016, 64, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, D.; Partridge, C.G.; Hassett, M.C.; Sienkiewicz, N.; Tyrrell, K.; Henderson, A.; Tardani, R.; Lu, J.; Steinman, A.D.; Vesper, S. Changes in Cyanobacterial Phytoplankton Communities in Lake-Water Mesocosms Treated with Either Glucose or Hydrogen Peroxide. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Xie, T.Y.; Janssen, P.H.; Sun, X.Z.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Tan, Z.L.; Gao, M. Shifts in Rumen Fermentation and Microbiota Are Associated with Dissolved Ruminal Hydrogen Concentrations in Lactating Dairy Cows Fed Different Types of Carbohydrates. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Process | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioassisted Photocatalysis | Microalgae or enzymes coupled with a photocatalytic semiconductor under illumination. photoexcited electrons reduce H+ to H2 with biological assistance. | Enhanced solar energy utilization thanks to the catalyst. | Requires a locally anaerobic environment due to the oxygen sensitivity of hydrogenases. | [134] |

| Selectivity and potential self-repair provided by biological components. | Complex bio-inorganic integration, risk of toxicity (e.g., CdS). | |||

| Experimental-phase technology with uncertain long-term stability. | ||||

| Bioelectrochemistry | Microbial electrochemical cells in which microalgae or bacteria generate an electrical current (via photoanode or fermentation) that, at a separate cathode, produces H2 with a small external voltage. | Physical separation of H2 and O2, reducing explosive risks. | Requires an external power supply that is lower than conventional electrolysis. | [135] |

| It can utilize organic waste and renewable electricity. | Low current densities limit production rates. | |||

| Produces high-purity hydrogen (>90%). | High material costs and challenges in industrial scaling. | |||

| Dark Fermentation | Anaerobic bacteria decompose biomass (e.g., microalgal sugars) to generate H2, CO2, and acids in the absence of light. | Continuous operation (24/7) without dependence on light. | Limited yield: only a fraction of the energy is retained in the products. | [133] |

| Technologically viable and easily scalable. | Requires biomass pretreatment to improve digestibility. | |||

| Enables the valorization of organic waste. | Biogas H2 is mixed with CO2 (40–60%), increasing separation costs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuorro, A.; Lavecchia, R.; Contreras-Ropero, J.E.; García-Martínez, J.B.; Barajas-Solano, A.F. Renewable Hydrogen from Biohybrid Systems: A Bibliometric Review of Technological Trends and Applications in the Energy Transition. Energies 2025, 18, 6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246563

Zuorro A, Lavecchia R, Contreras-Ropero JE, García-Martínez JB, Barajas-Solano AF. Renewable Hydrogen from Biohybrid Systems: A Bibliometric Review of Technological Trends and Applications in the Energy Transition. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246563

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuorro, Antonio, Roberto Lavecchia, Jefferson E. Contreras-Ropero, Janet B. García-Martínez, and Andrés F. Barajas-Solano. 2025. "Renewable Hydrogen from Biohybrid Systems: A Bibliometric Review of Technological Trends and Applications in the Energy Transition" Energies 18, no. 24: 6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246563

APA StyleZuorro, A., Lavecchia, R., Contreras-Ropero, J. E., García-Martínez, J. B., & Barajas-Solano, A. F. (2025). Renewable Hydrogen from Biohybrid Systems: A Bibliometric Review of Technological Trends and Applications in the Energy Transition. Energies, 18(24), 6563. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246563