Thermal Analysis of High-Power Water-Cooled Permanent Magnet Coupling Based on Rotational Centrifugal Fluid–Structure Coupling Field Inversion

Abstract

1. Introduction

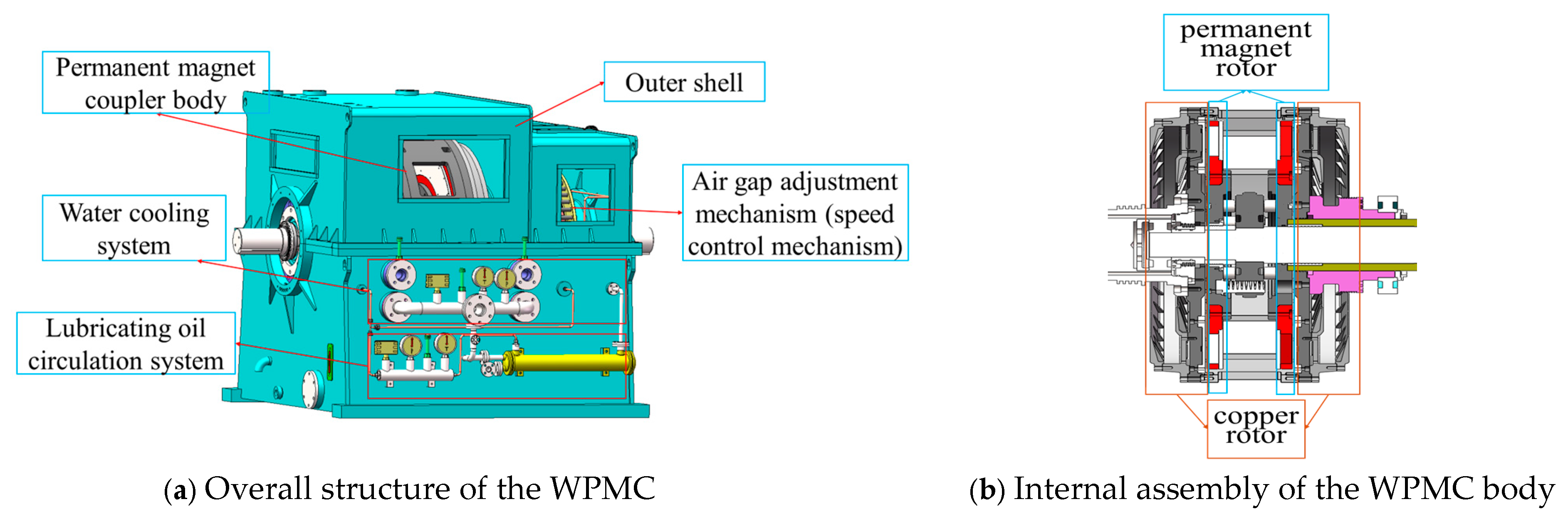

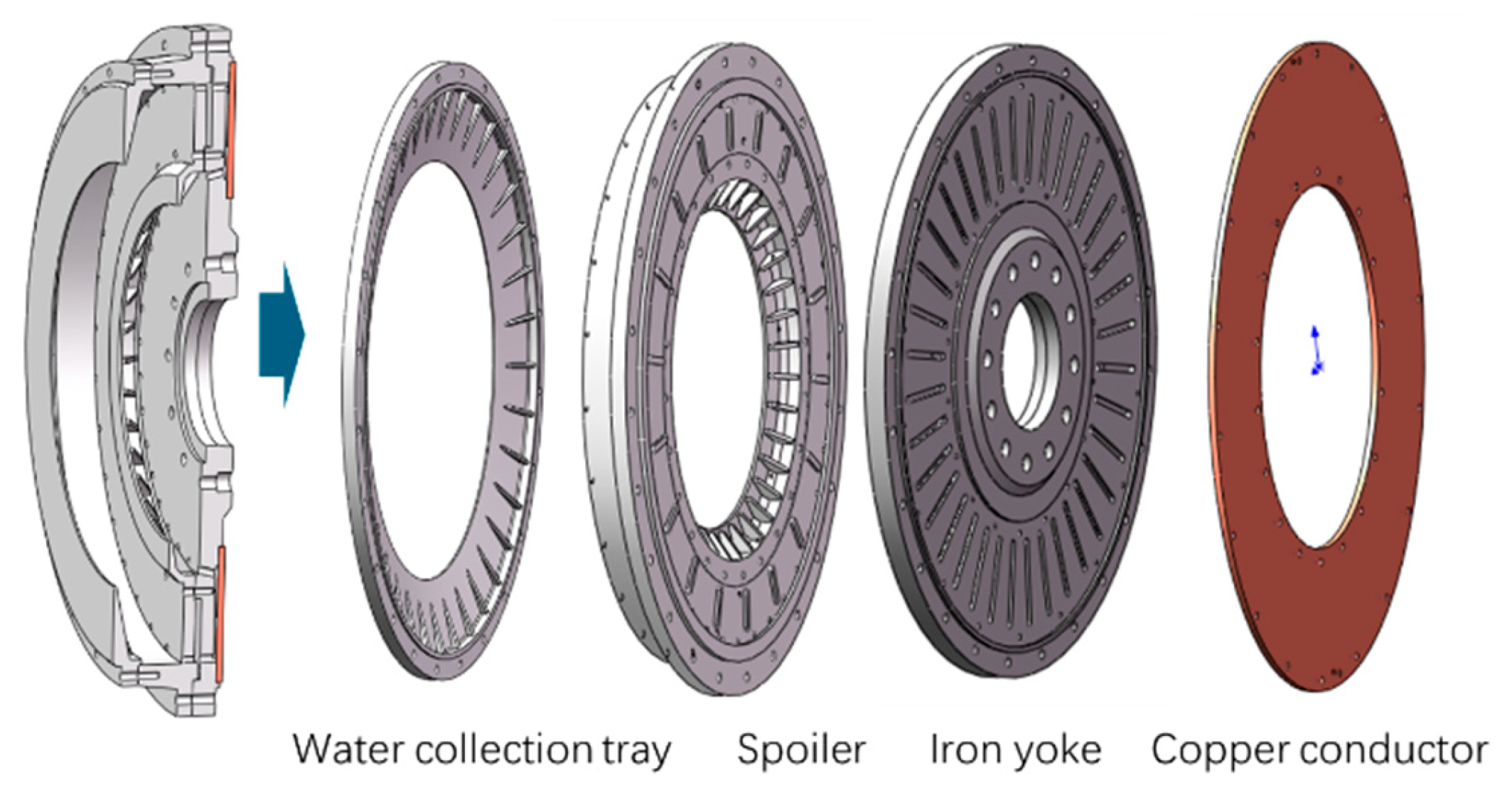

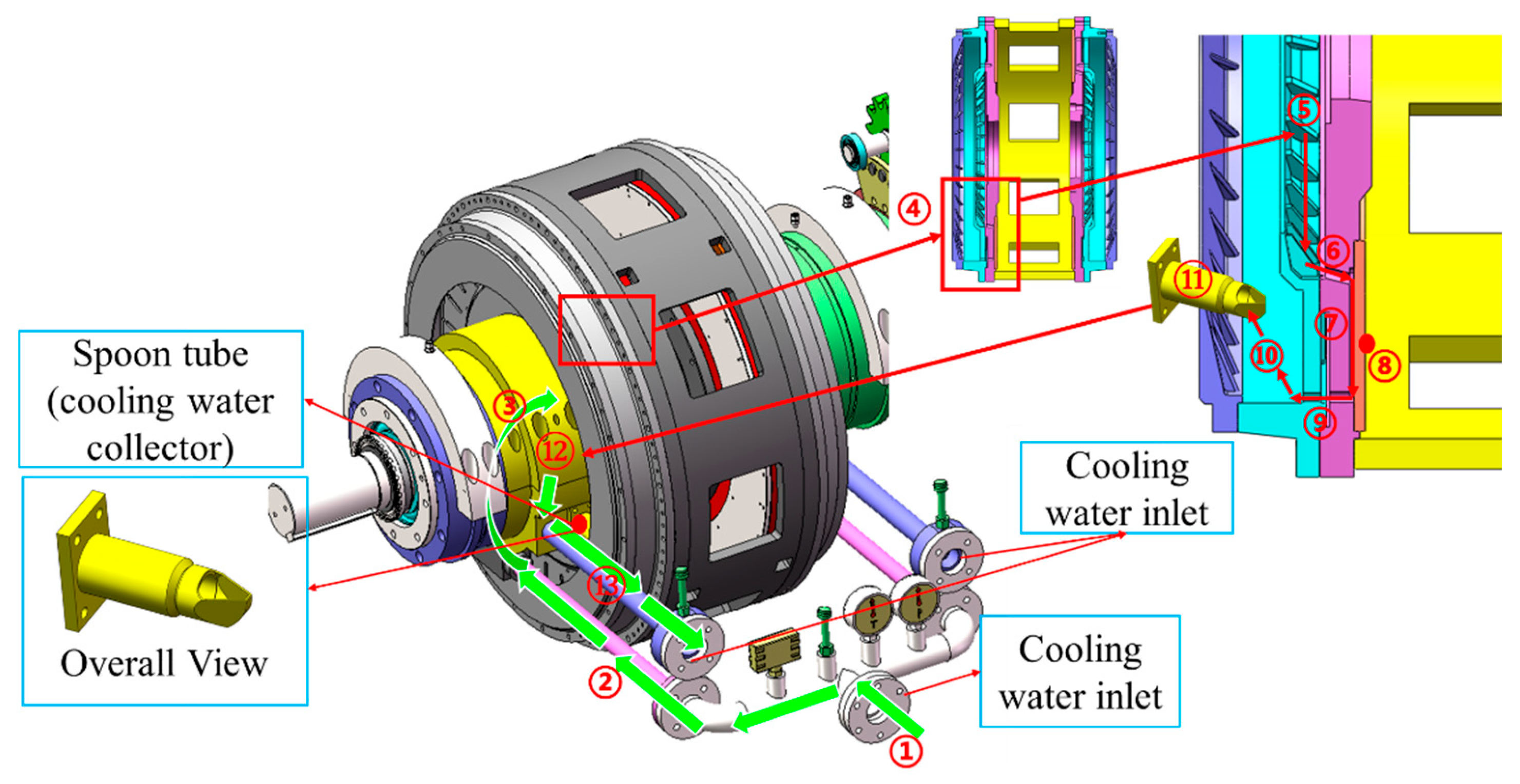

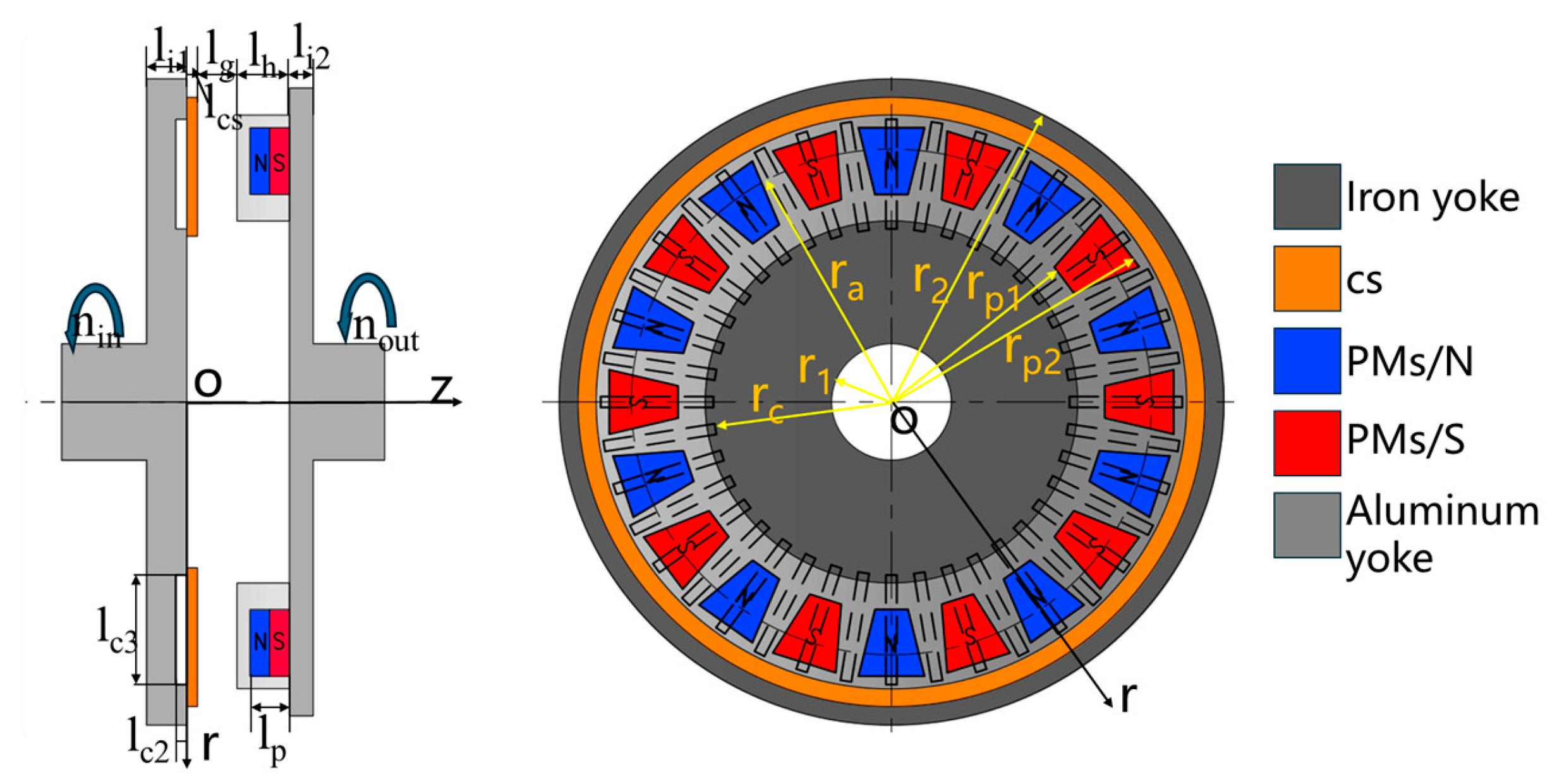

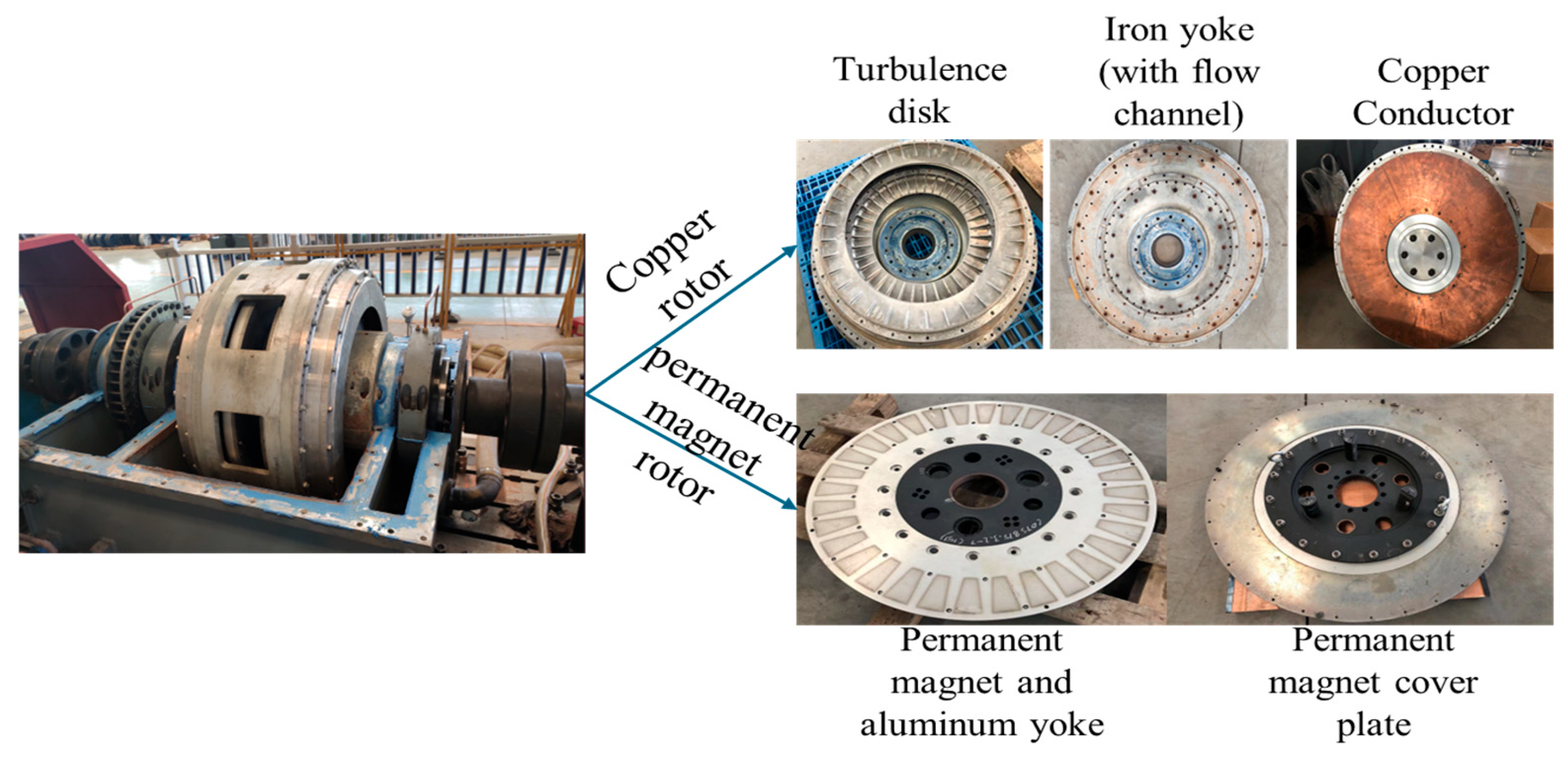

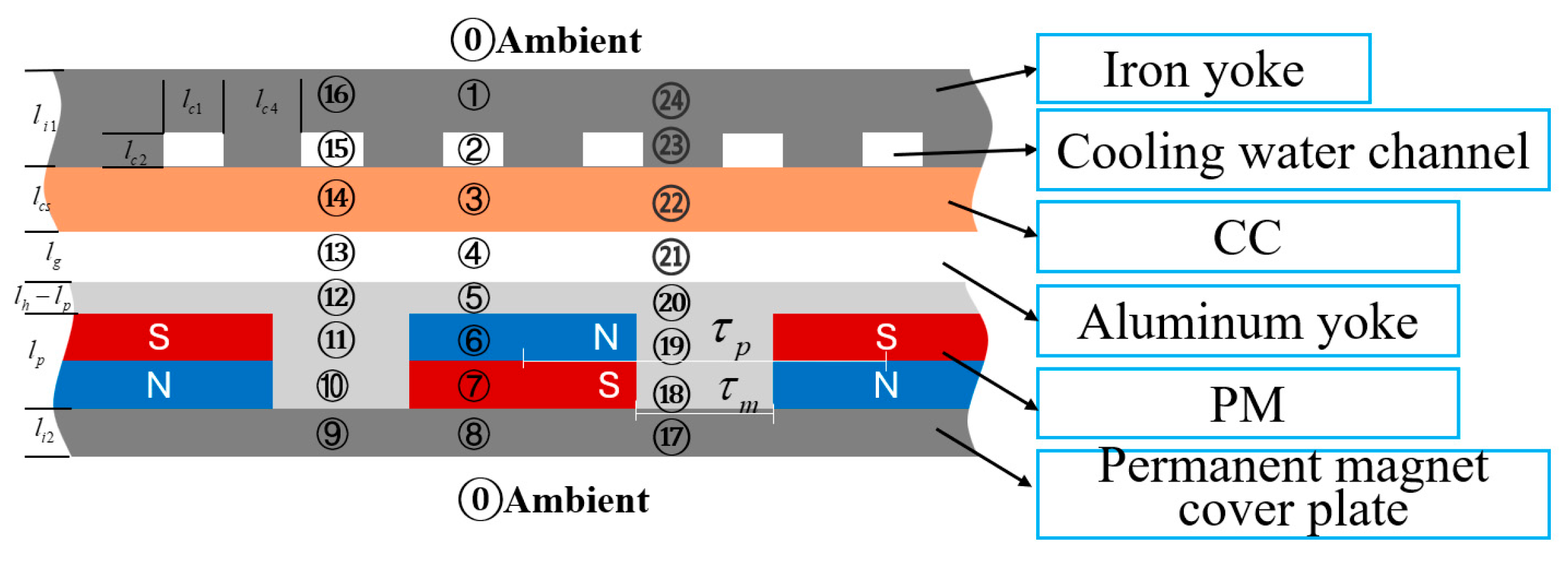

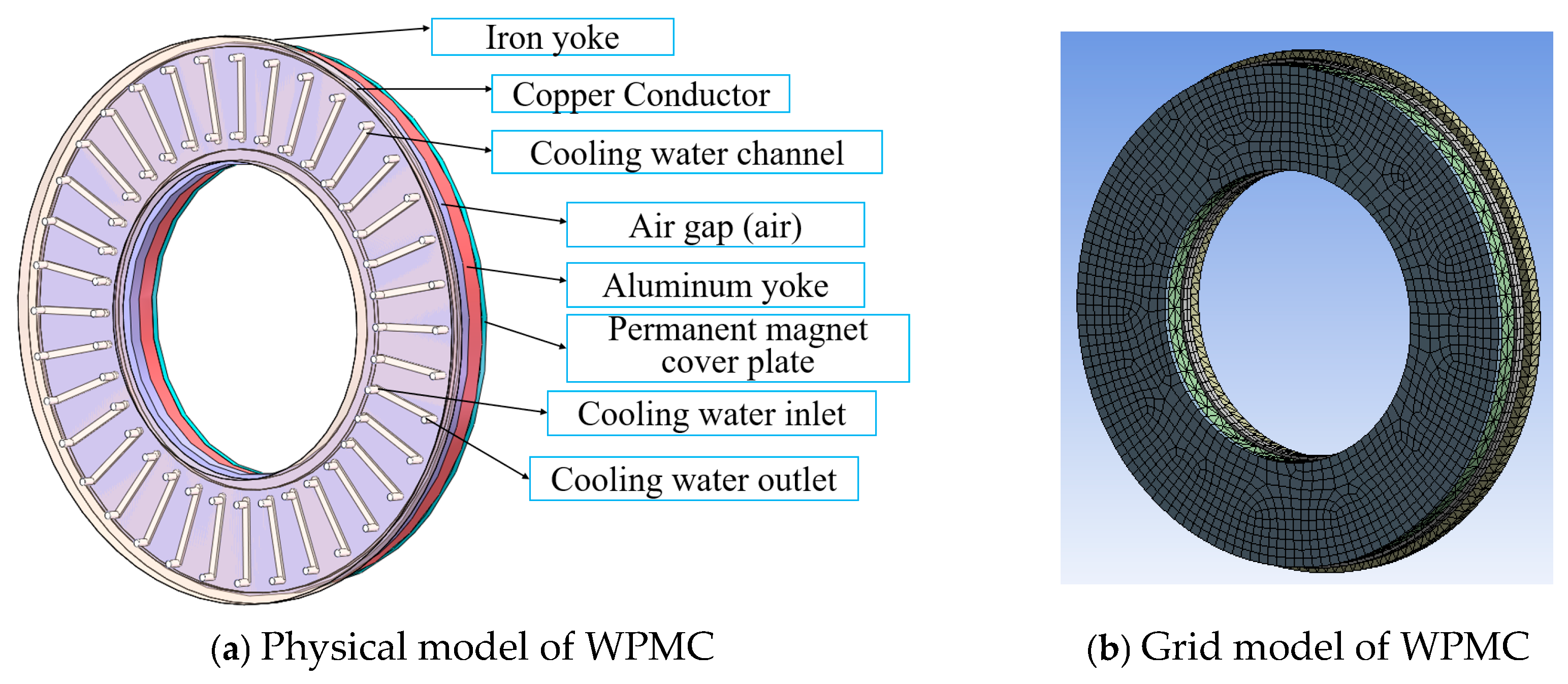

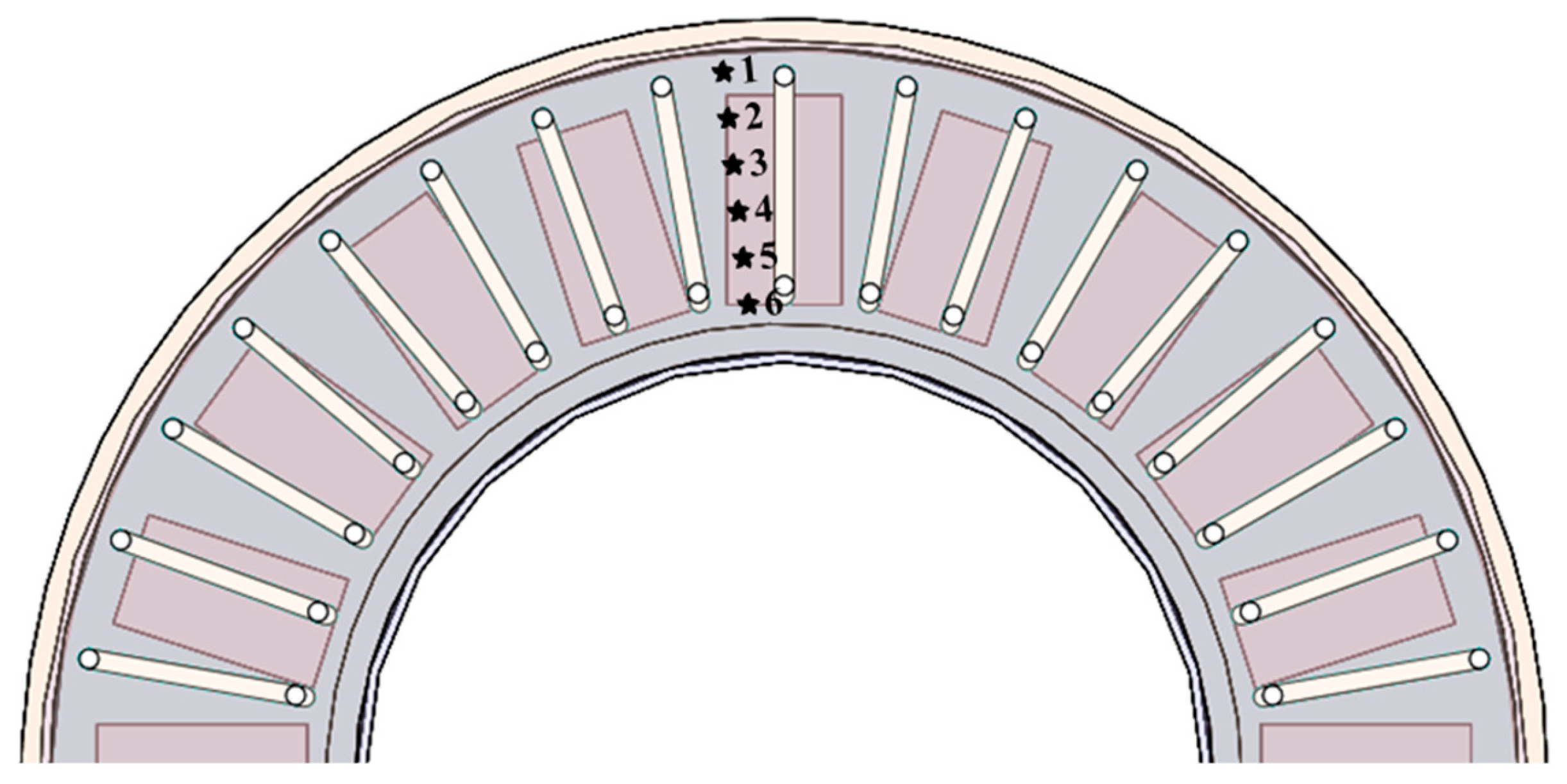

2. Geometric Model of WPMC

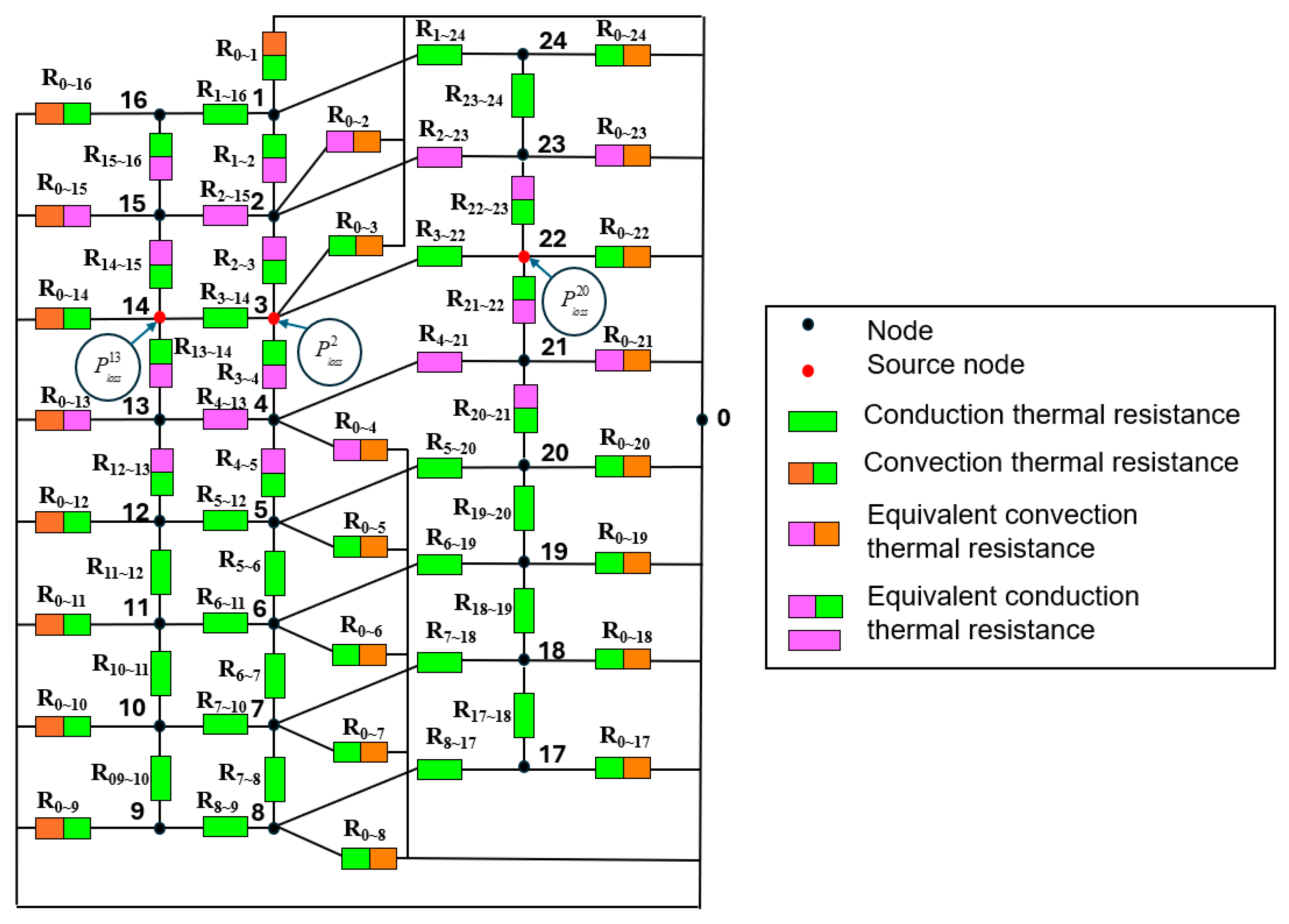

3. ETNM

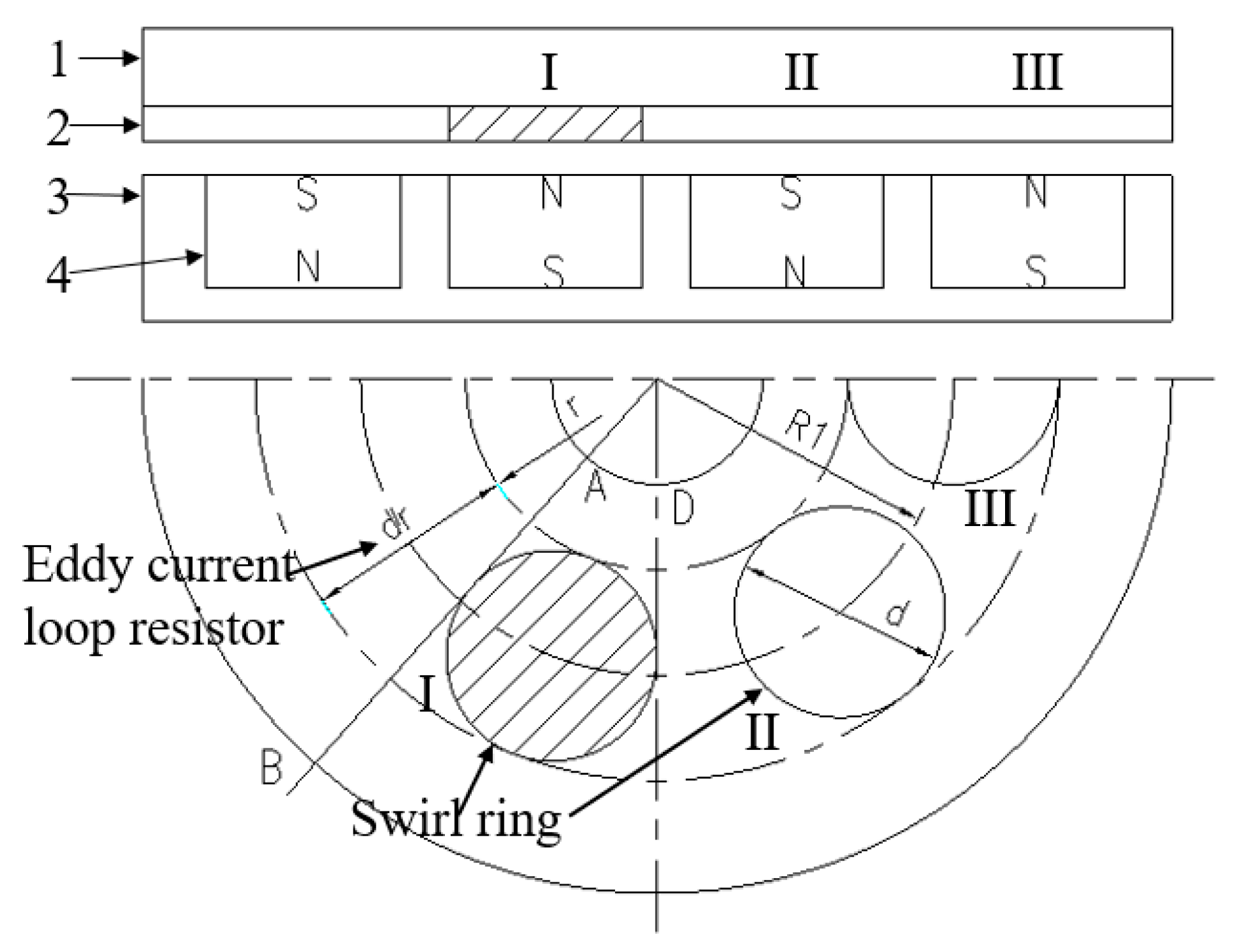

3.1. Power Loss Calculation

Sensitivity Analysis and Model Validation

3.2. Thermal Resistance Calculation

3.3. Discussion on Model Assumptions

4. Calculation of Cooling Water Flow Rate and Temperature Rise

4.1. Calculation of Cooling Water Flow Rate

4.2. Temperature Rise Calculation

5. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Verification

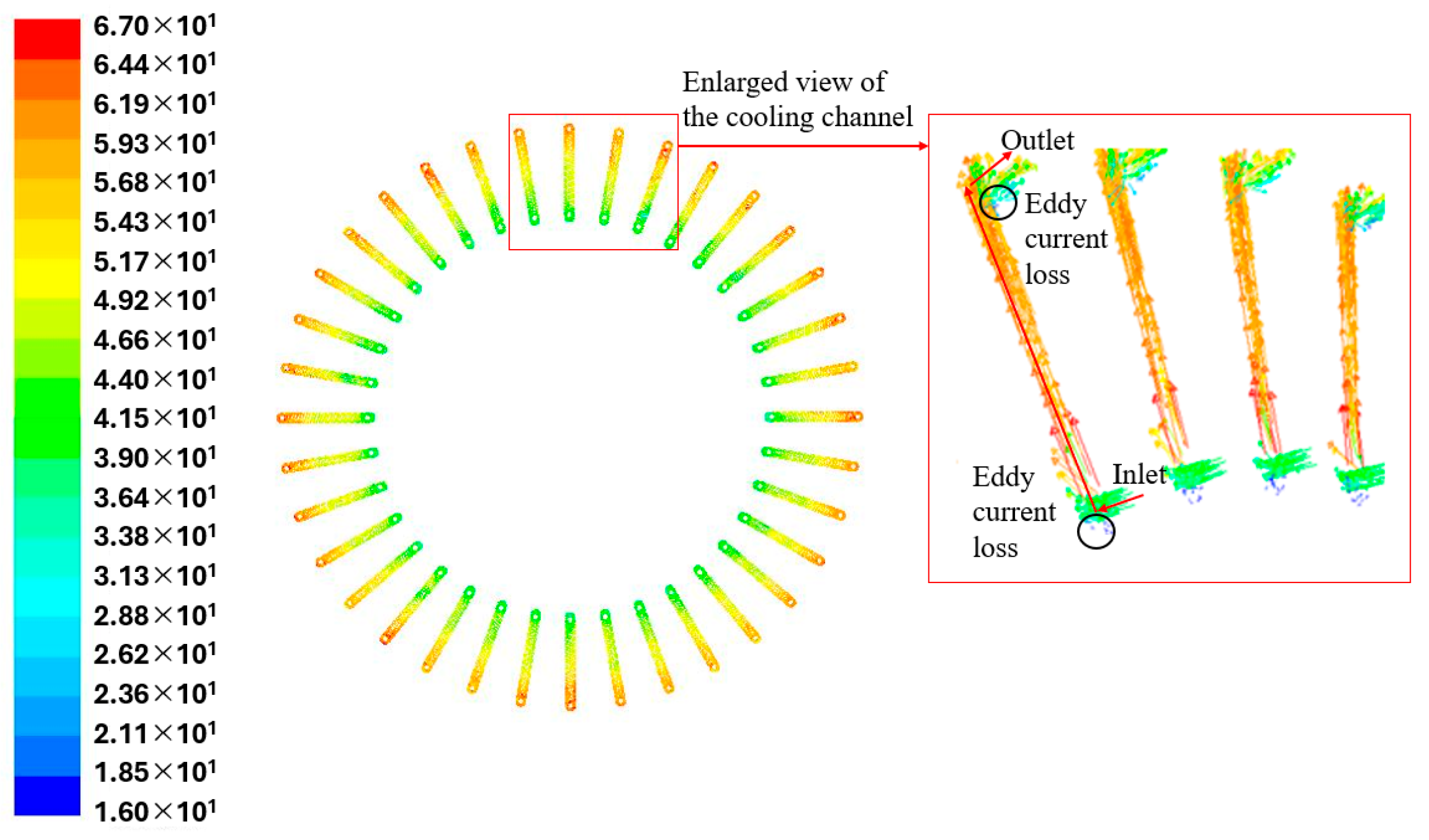

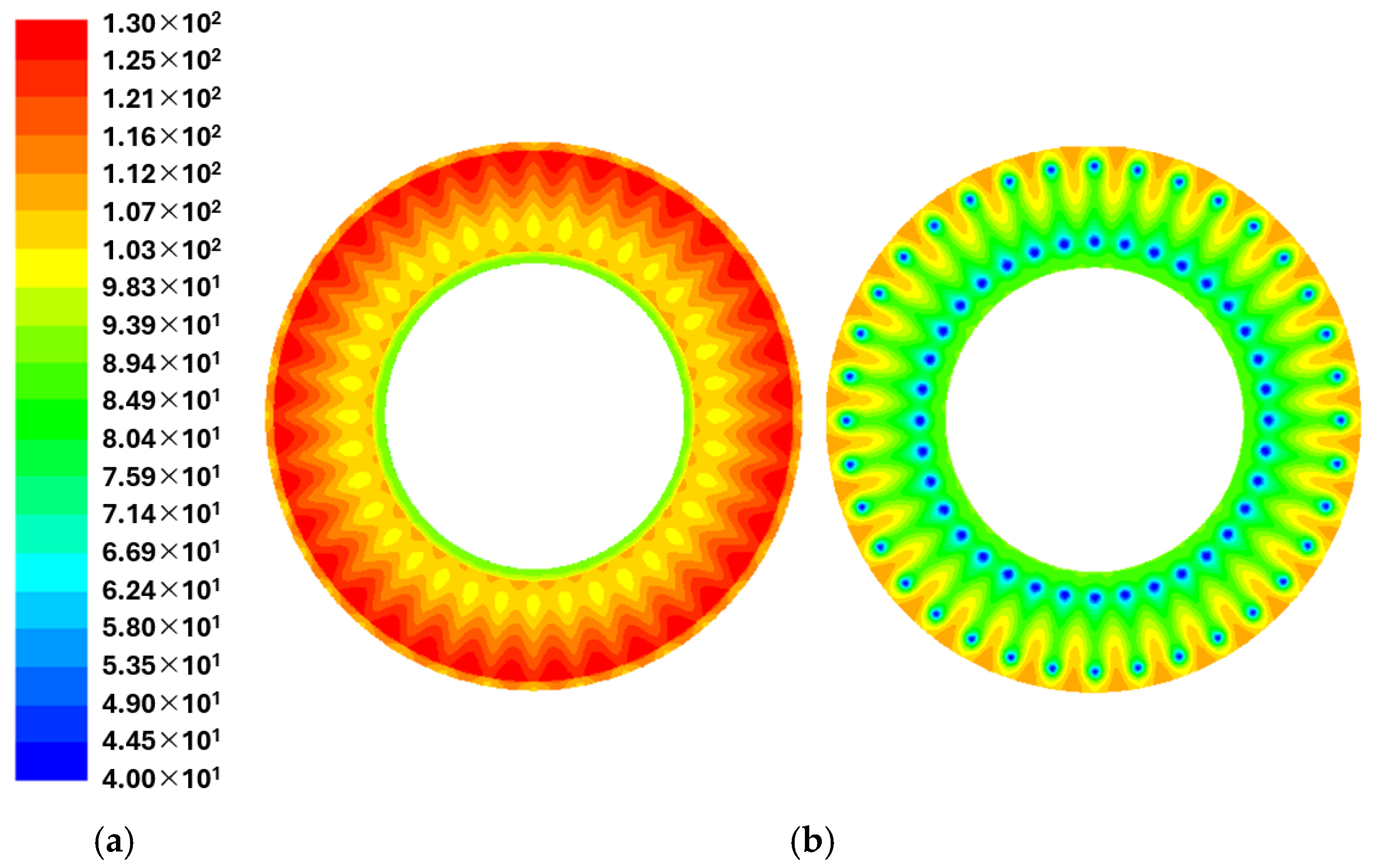

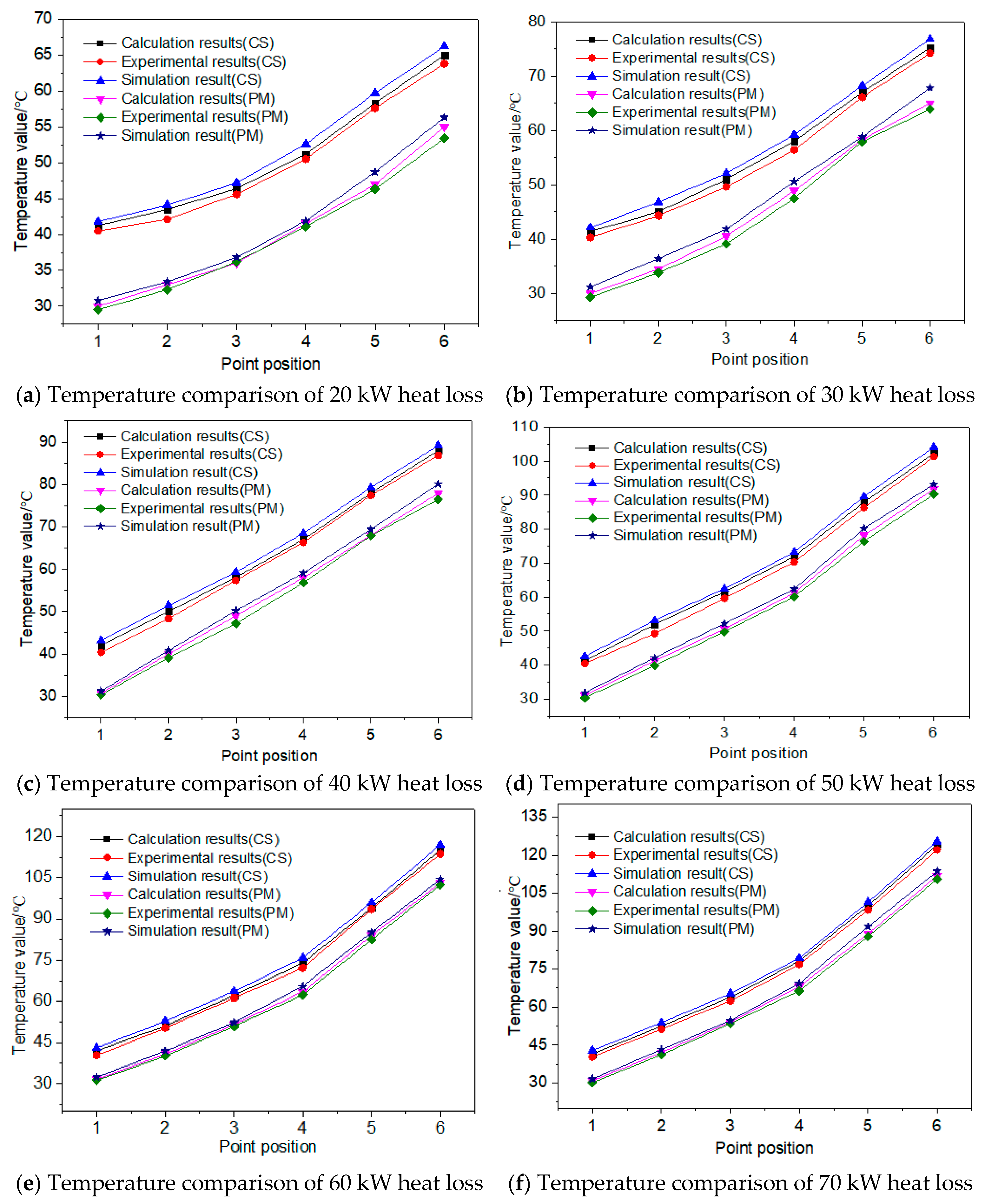

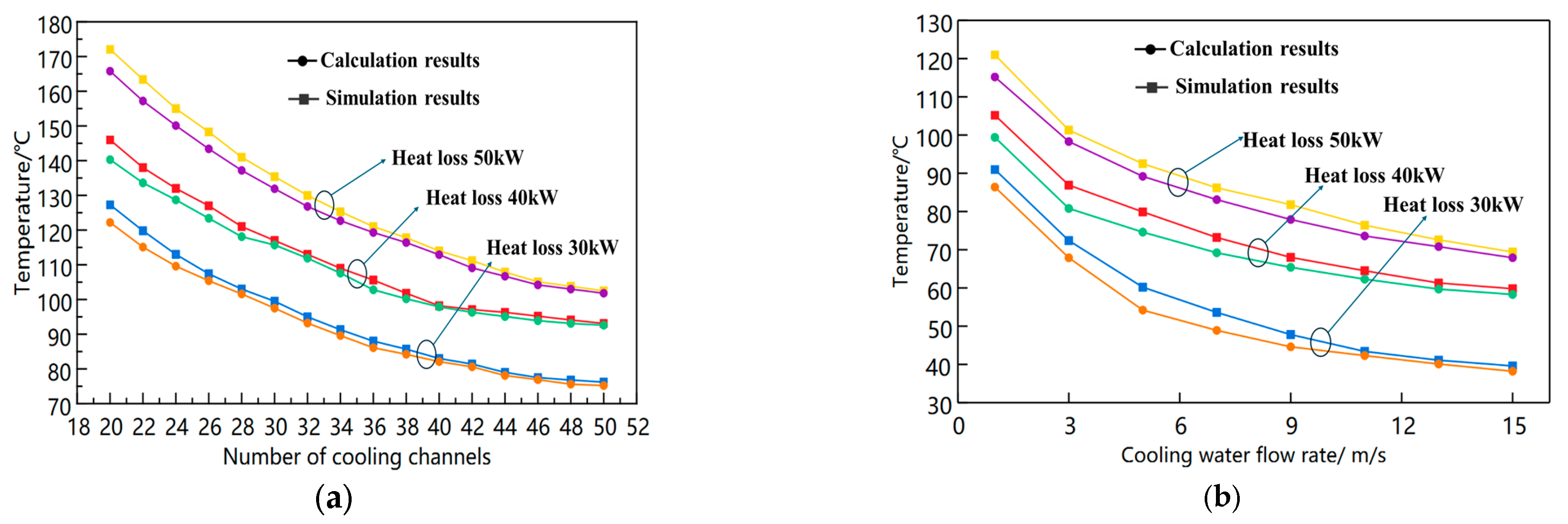

5.1. Numerical Simulation Verification

5.2. Experimental Verification

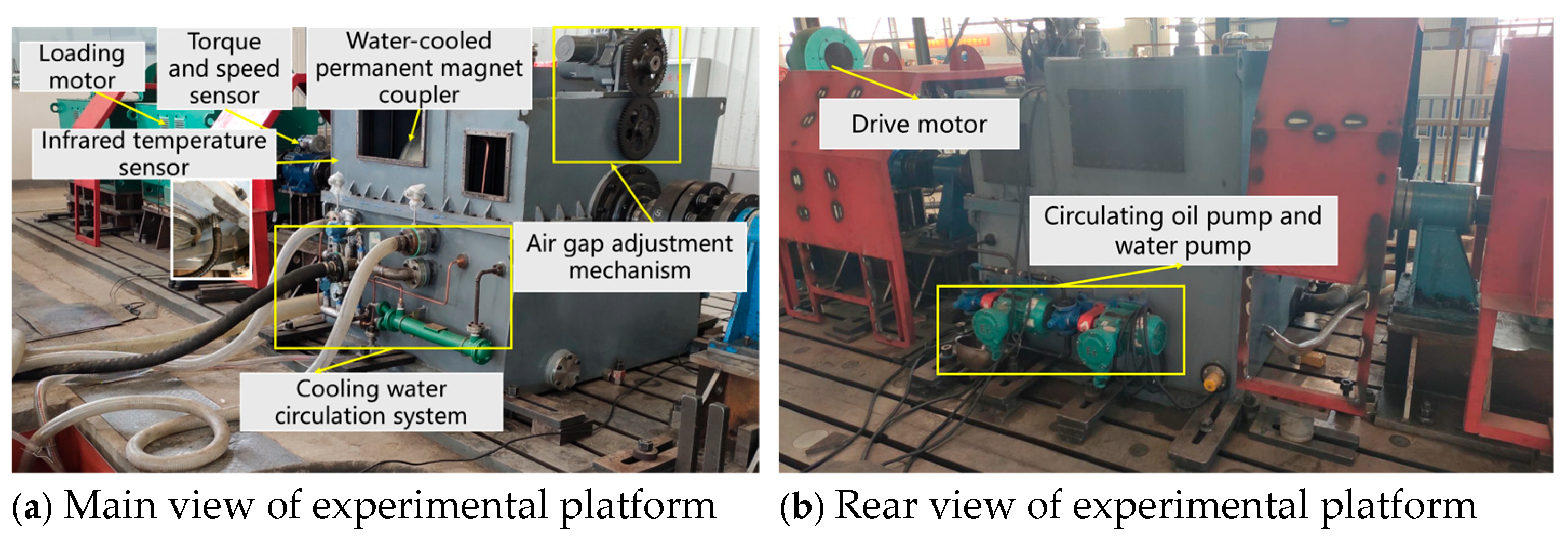

5.2.1. Construction and Application of Experimental Platform

5.2.2. Experimental Process

5.3. Verification of Result Analysis

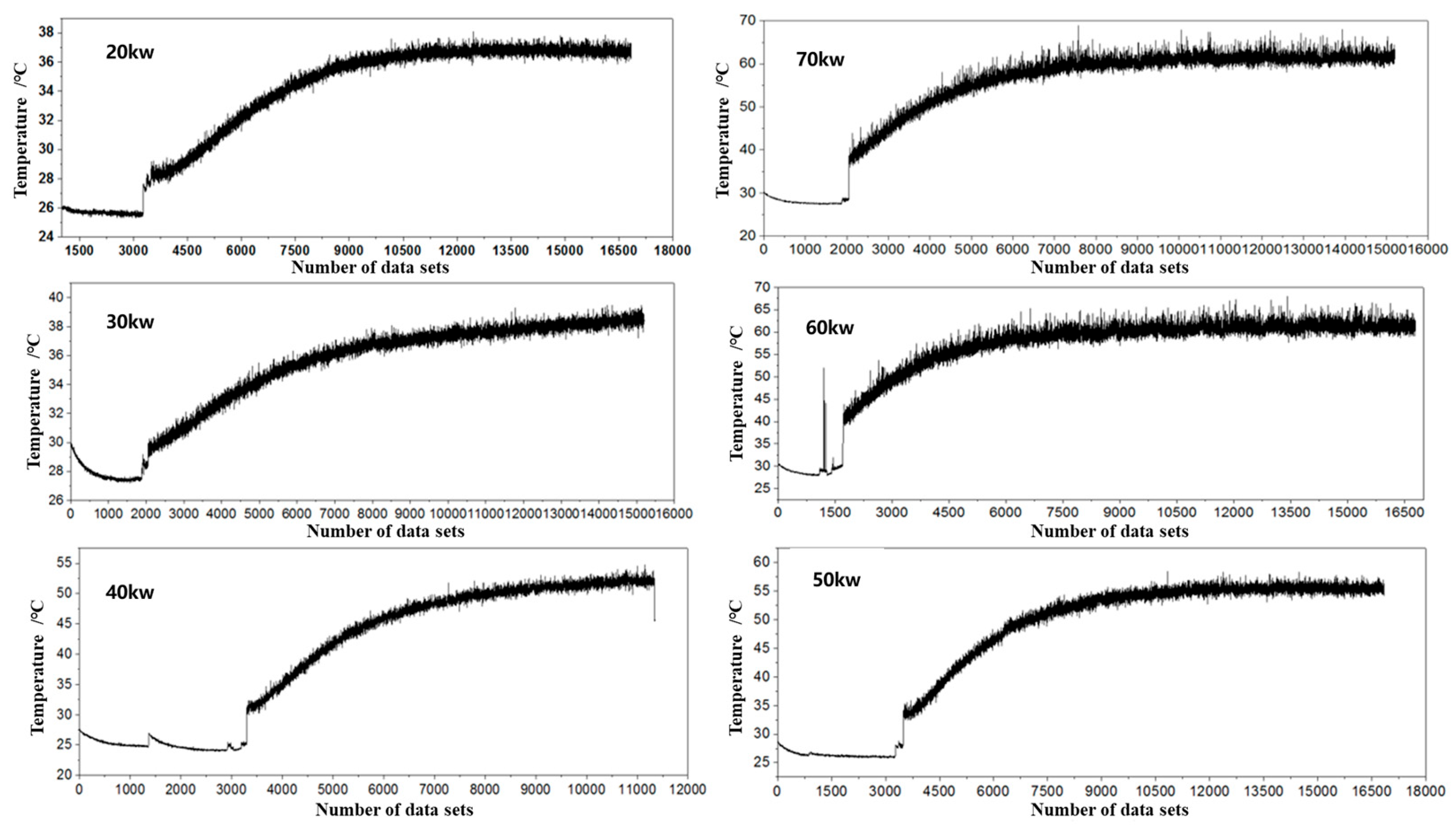

6. On-Site Experimental Verification

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Li, Y. Technical Renovation Practice of Permanent Magnet Coupling in Mining Crusher System. China Equip. Eng. 2024, 19, 140–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Qi, F. Application of Permanent Magnet Coupling in Belt Conveyor. Ship Electr. Technol. 2024, 44, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Lu, S. Optimization of Tesla Valve Cooling Channels for High-Efficiency Automotive PMSM. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhu, X. Torque Ripple Suppression of a PM Vernier Machine from Perspective of Time and Space Harmonic Magnetic Field. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 10150–10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, S. Temperature field analysis of external-cage rotor magnetic coupling. Electr. Mach. Control. Appl. 2023, 50, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, H. Analytical Calculation of Magnetic Field and Temperature Field of Surface Mounted Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2024, 20, 2249–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Liu, J.; Shui, Q.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.; Ji, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, S. High Thermal Conductivity Network Based Heat Dissipation for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 58, 103202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Quan, L.; Fan, D.; Liu, Q. Research on Characteristic Airgap Harmonics of a Double-Rotor Flux-Modulated PM Motor Based on Harmonic Dimensionality Reduction. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 5750–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Ni, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qi, Y.; Kong, D.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, S. Analysis of Heat Dissipation Structure of Permanent Magnet Eddy Current Coupler Based on Magnetothermal Multi-physics Coupling. In Proceedings of the 2024 36th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Xi’an, China, 25–27 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wang, D.; Gao, Q.; Kong, D.; Wang, S. Modeling and Performance Analysis of an Axial-Radial Combined Permanent Magnet Eddy Current Coupler. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 78367–78377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Yin, W.; Tang, X.; Ju, J.; Wu, L.; Cui, Y.; Chen, R.; Yan, A. High-temperature magnetic performance and corrosion resistance of hot-deformed and sintered Nd-Fe-B magnets with similar room-temperature magnetic properties. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 587, 171321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Ma, W. Research on Multi-physics bidirectional coupling for small-diameter high-speed submersible permanent magnet synchronous motor. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Gao, H.; Hu, G.; Cui, H. Experimental and theoretical analysis of magnetic-thermal-mechanical coupling of permanent magnet coupling. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 095323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Qi, Y.; Le, B.; Feng, Z. Design and Experimental Study of Water Cooling System for External Rotor Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 88034–88047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Cao, J.; Li, D.; An, G. Water Cooling Structure Design and Temperature Field Analysis of Low Floor Direct Drive Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Wuhan, China, 28–30 May 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. Optimized Design of Cooling System for External Rotor Permanent Magnet Motor. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Dali, China, 9–11 May 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Lu, H.; Liu, M. Experiment for flow field and convective heat transfer between rotor and stator with finite length at high rotational speed. J. Aerosp. Power 2024, 39, 20230001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, G.J.; Ren, B.; Chong, Y.C.; Michon, M. Investigation of Ferrofluid Cooling for High-power Density Permanent Magnet Machines. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2023, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jacques, B.B.; Shi, R.; Pillay, P. An Enhanced PMSM Cooling Design for Traction of an Electric Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 3845–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Yao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Peng, F.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Cavagnino, A. Application and Verification of Spiral Water Cooling for Rotor in High-Power Density Motors. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.H.; Zhang, T.; Lu, Q. Thermal Analysis of a Flux-Switching Permanent-Magnet Double-Rotor Machine with a 3-D Thermal Network Model. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2019, 29, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hane, Y.; Nakamura, K. Dynamic Hysteresis Modeling Taking Skin Effect into Account for Magnetic Circuit Analysis and Validation for Various Core Materials. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-M.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, S.-G.; Park, M.-R.; Lee, G.-H.; Lim, M.-S. Estimation Method for Rotor Eddy Current Loss in Ultrahigh-Speed Surface-Mounted Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, W. Research on Magnetic-Fluid-Thermal-Stress Multi-Field Bidirectional Coupling of High-Speed Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. Energies 2024, 54, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, C.; El Hannaoui, A.; Boutarfa, R.; Harmand, S. Flow and Convective Exchanges Study in Rotor-Stator System with Eccentric Impinging Jet. ASME J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 145, 042301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zhu, L.; Meng, N.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J.; Li, Q. Thermal Analysis and Cooling Enhancement of a Slot less High-Speed Permanent Magnet Motor Based on CFD. In Proceedings of the 2022 25th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 29 November–2 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Li, Z.; Tong, W. Research on Thermal Calculation and End Winding Heat Conduction Optimization of Low Speed High Torque Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2023, 7, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Ramasami, S.; Chokkalingam, L.N. Review on Thermal Behavior and Cooling Aspects of Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Motors–A Mechanical Approach. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6822–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Cooling Type | Flow Treatment | Thermal Nodes | Accuracy | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional CFD | Water/Air | Static Flow Assumption | / | Boundary-Sensitive | Static/Low-Speed Devices |

| Traditional ETNM | Air Cooling | Empirical Formulas | <15 nodes | Error > 8% | Low-Power PMCs |

| Our Method | Rotational Water Cooling | MRF-Based Centrifugal Flow Inversion | 22 Nodes | Error ≤ 5.6% | High-Power WPMCs |

| Method | Cooling Type | Flow Treatment | Thermal Nodes | Accuracy | Application |

| Name | Meaning | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Thickness of the iron yoke (CC side) | 22 mm | |

| Thickness of the iron yoke (PM side) | 10 mm | |

| Thickness of the CC | 8 mm | |

| Thickness of the air gap | 3–34 mm can be changed | |

| Thickness of the PM holder | 34 mm | |

| Thickness of the PM | 33 mm | |

| Inside radius of the CC | 220 mm | |

| Outside radius of the CC | 400 mm | |

| Inside radius of the PM | 250 mm | |

| Outside radius of the PM | 360 mm | |

| Average radius of the PM | 355 mm | |

| Inner diameter of the cooling channel | 232 mm | |

| Cooling channel width | 150 mm | |

| Cooling channel depth | 4 mm | |

| Cooling channel length | 10 mm | |

| Cooling channel spacing | 22 mm | |

| Coercive force of the PM | −900 KA/m | |

| Conductivity of the CC | 5.8 × 107 S/m(20 °C) |

| Parameter | Variation Range | Impact on Eddy Current Loss | Key Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| CC Conductivity | 20 °C to 130 °C | +12% | Resistivity increases with temperature. |

| PM Coercivity | 20 °C to 110 °C | −<3% | Slight decrease in air gap flux density. |

| Air gap Length | 3 mm to 34 mm | −>80% | Significant decrease in air gap flux density. |

| Material | Symbol | Value (W/(m·°C)) |

|---|---|---|

| Steel | 36 | |

| Copper | 390 | |

| Aluminum | 237 | |

| Nd-Fe-B | 9 | |

| Air | 0.026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Yang, C. Thermal Analysis of High-Power Water-Cooled Permanent Magnet Coupling Based on Rotational Centrifugal Fluid–Structure Coupling Field Inversion. Energies 2025, 18, 6556. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246556

Zhu Y, Liu W, Liu H, Yang C. Thermal Analysis of High-Power Water-Cooled Permanent Magnet Coupling Based on Rotational Centrifugal Fluid–Structure Coupling Field Inversion. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6556. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246556

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yuqin, Wei Liu, Hao Liu, and Chuang Yang. 2025. "Thermal Analysis of High-Power Water-Cooled Permanent Magnet Coupling Based on Rotational Centrifugal Fluid–Structure Coupling Field Inversion" Energies 18, no. 24: 6556. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246556

APA StyleZhu, Y., Liu, W., Liu, H., & Yang, C. (2025). Thermal Analysis of High-Power Water-Cooled Permanent Magnet Coupling Based on Rotational Centrifugal Fluid–Structure Coupling Field Inversion. Energies, 18(24), 6556. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246556