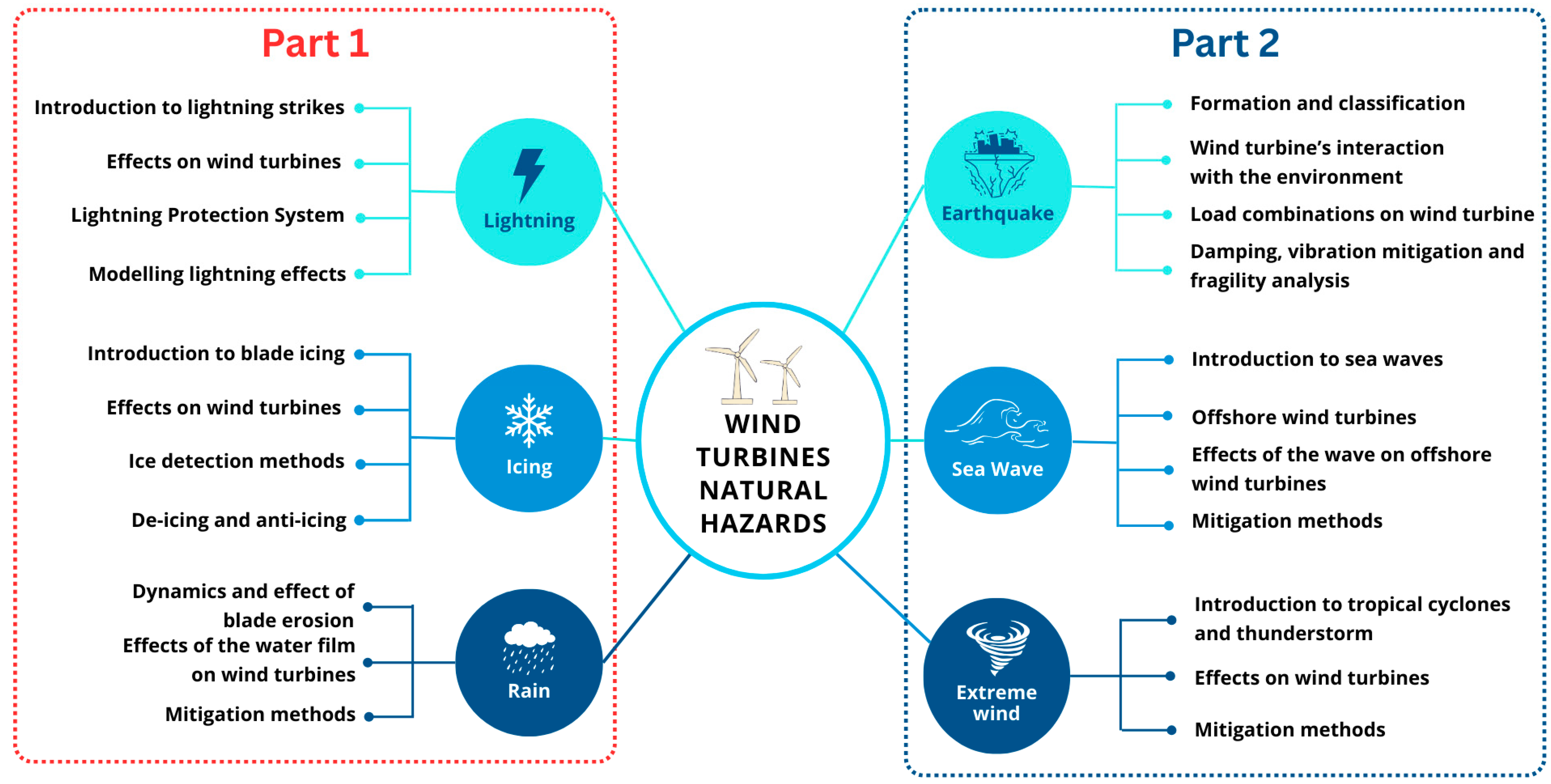

A Review of Meteorological Hazards on Wind Turbines Performance: Part 1 Lightning, Icing, and Rain

Abstract

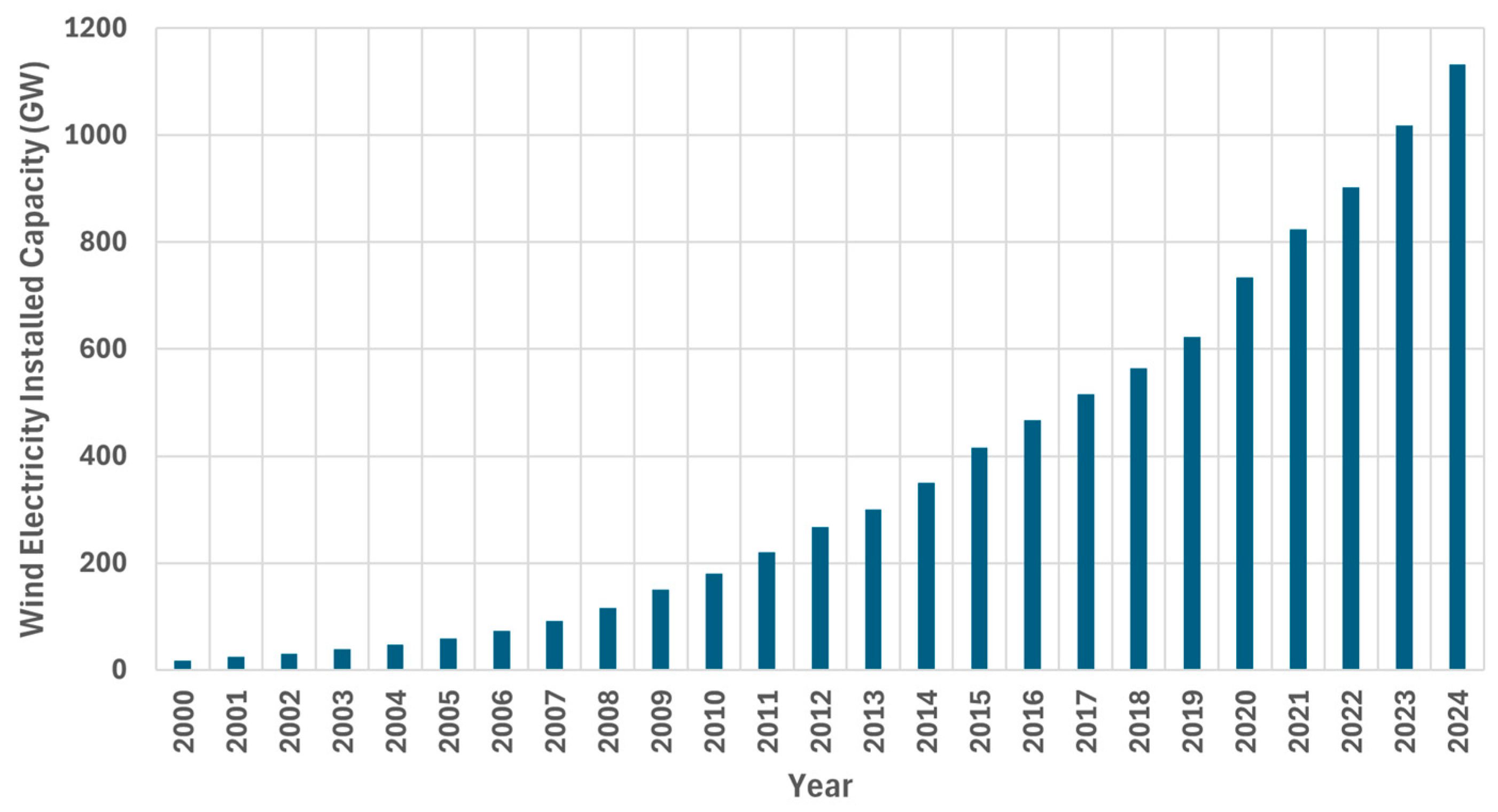

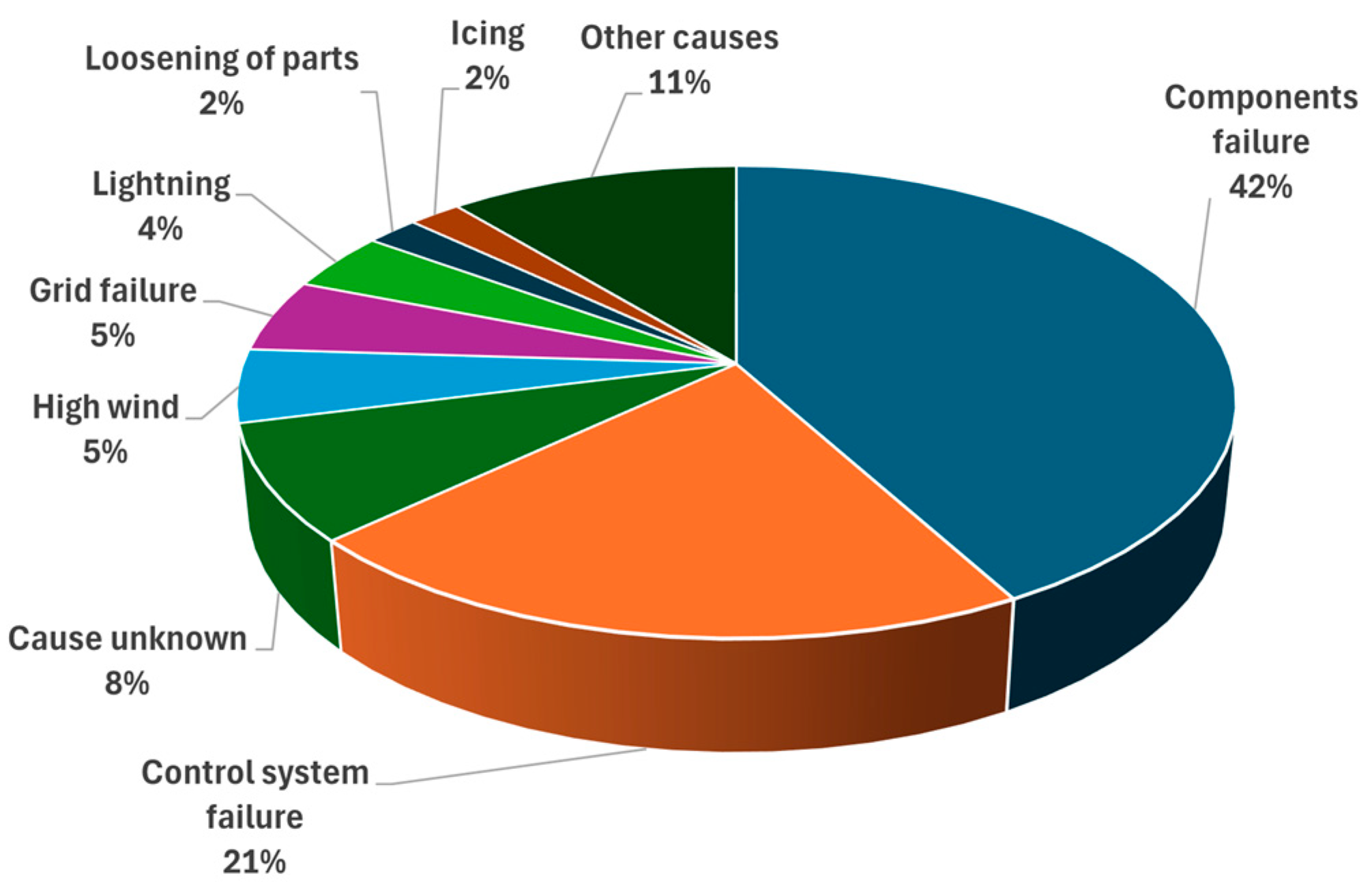

1. Introduction

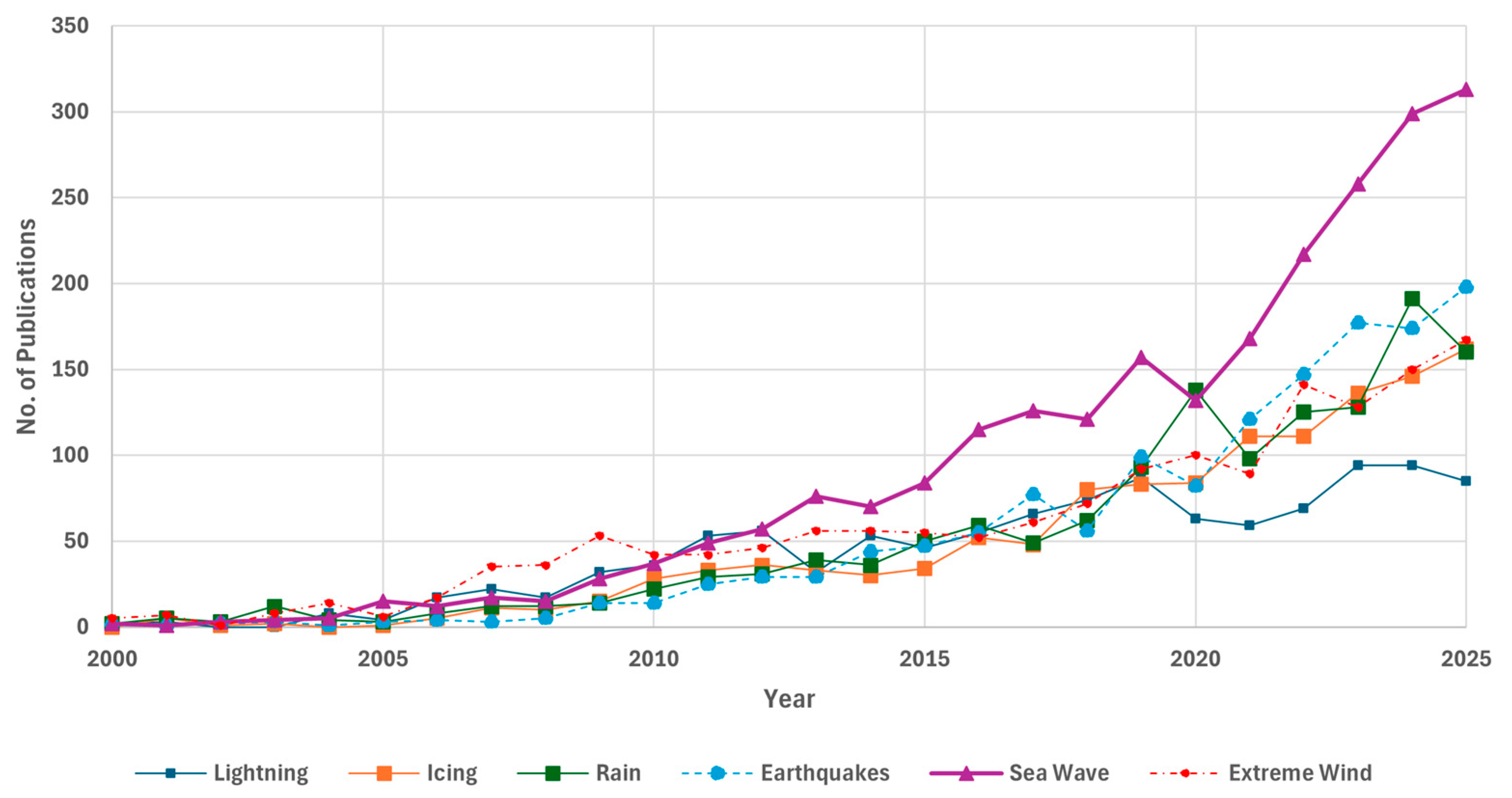

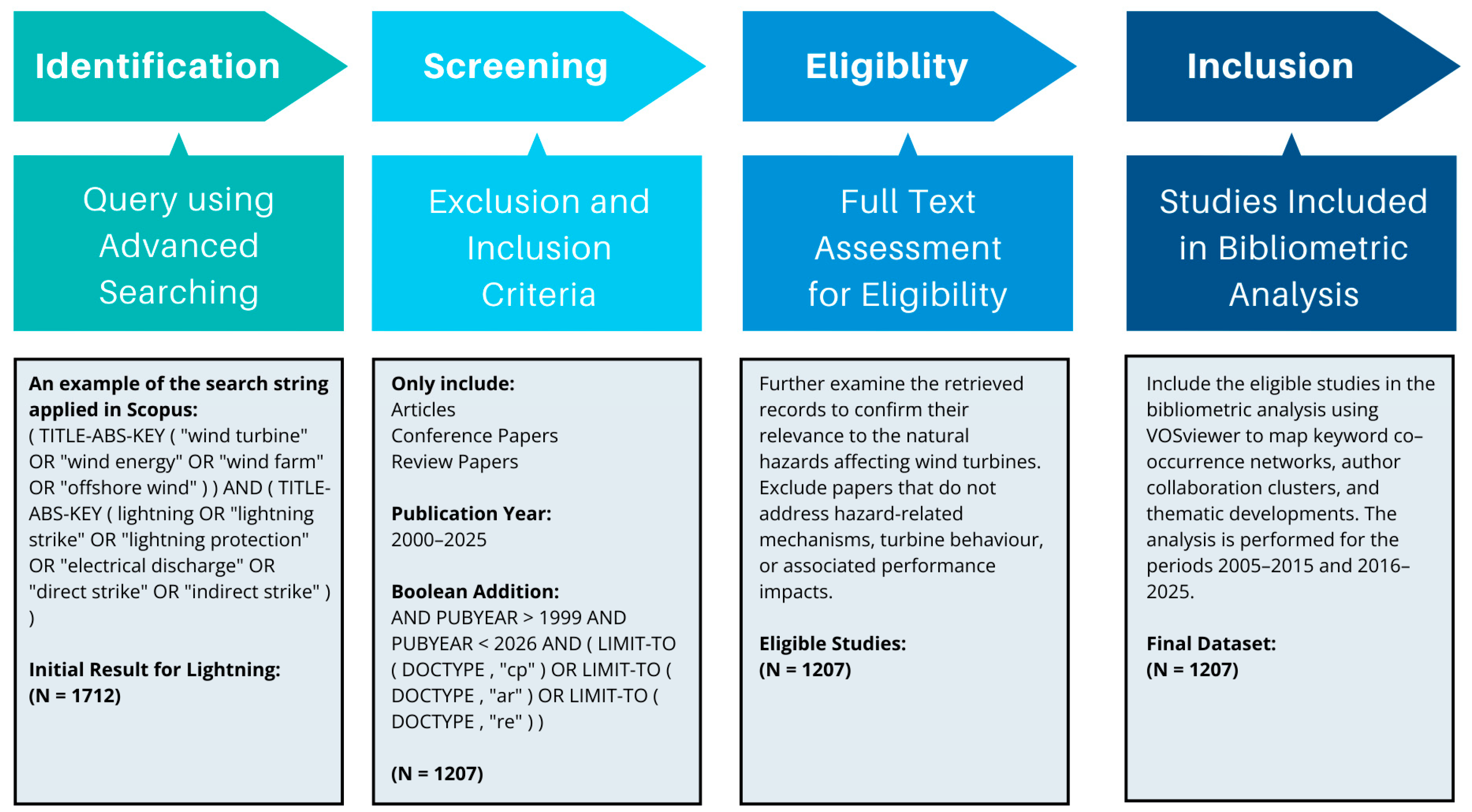

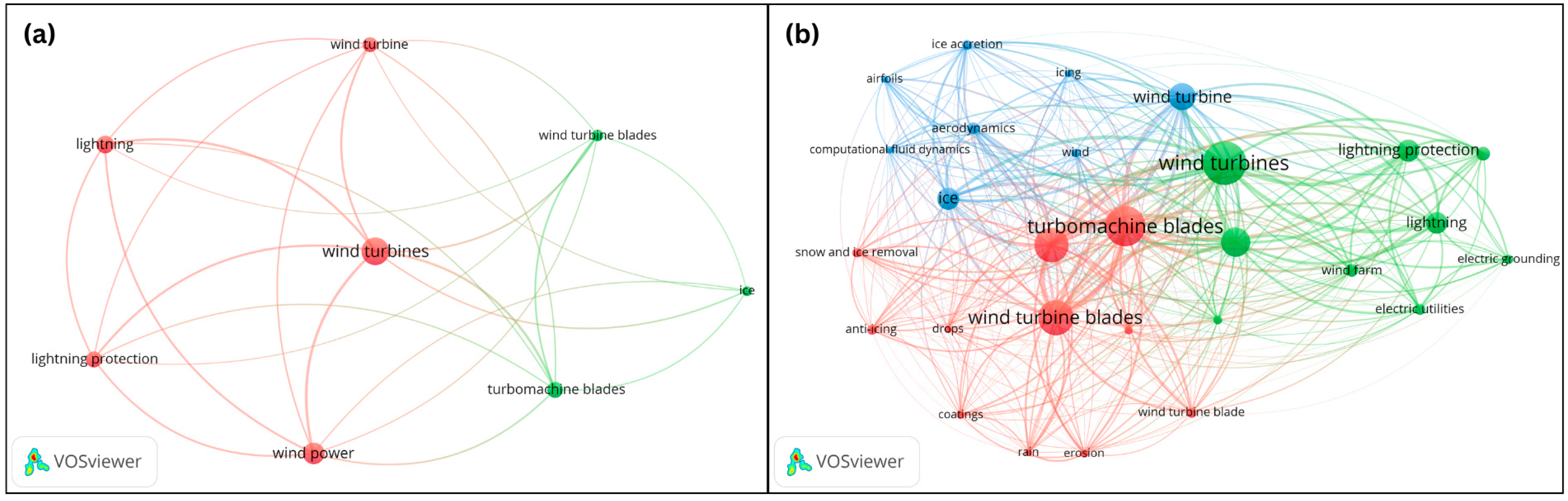

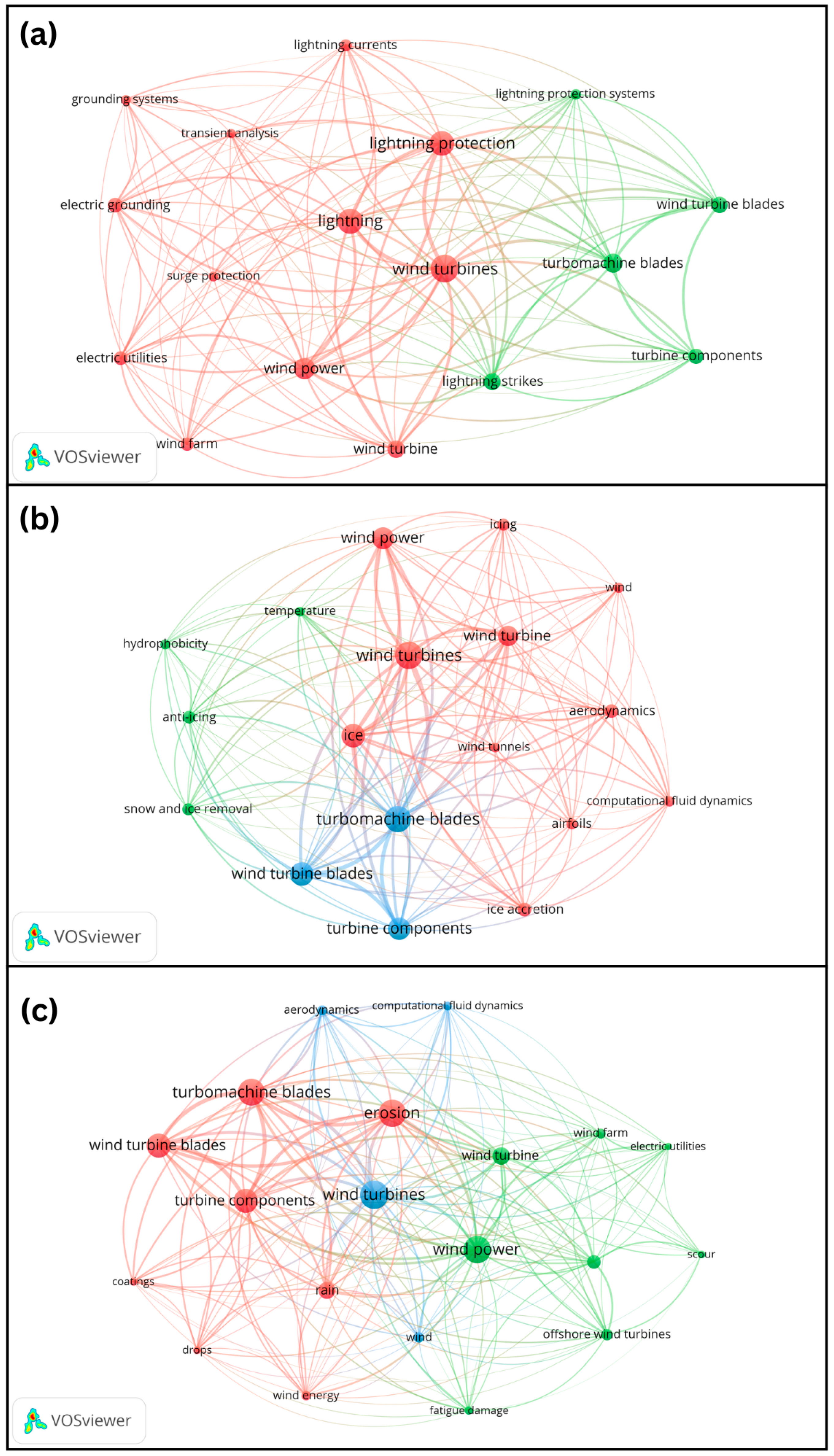

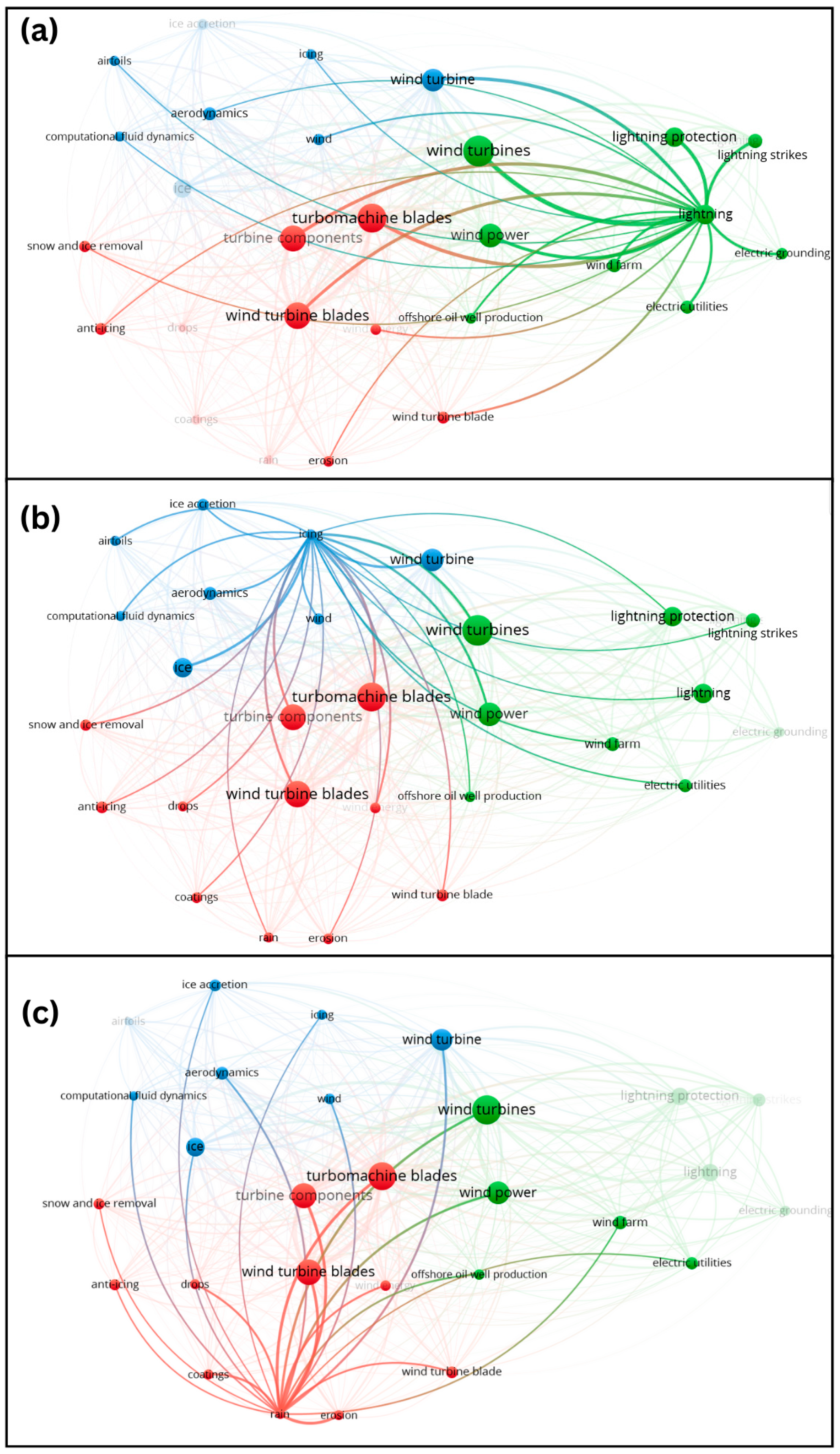

Analysis of Research Trend in Wind Turbine Natural Hazards

2. Lightning and Wind Turbines

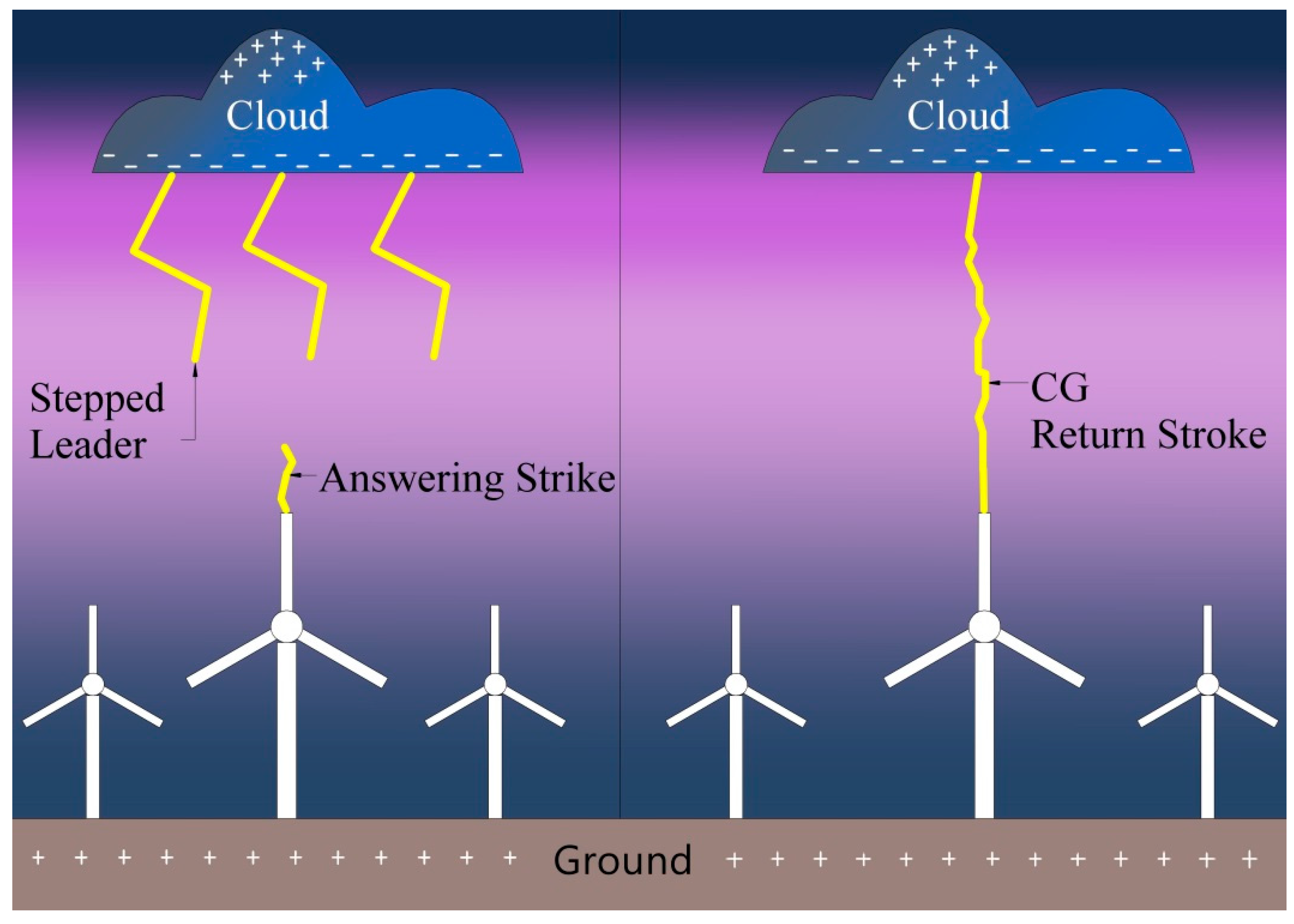

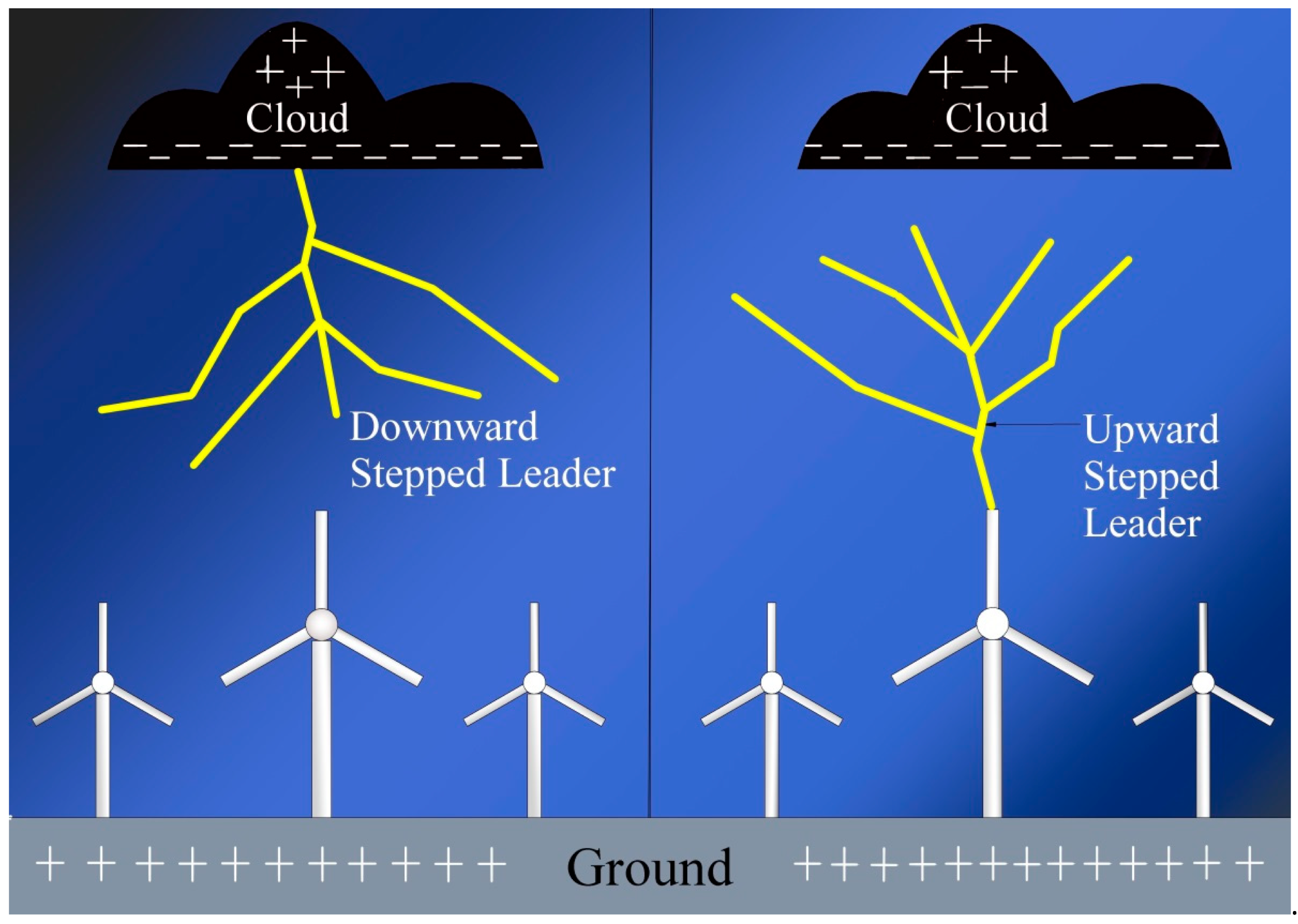

2.1. Introduction to Lightning Strikes

Upward Lightning, Downward Lightning and the Wind Turbines

2.2. Effects of Lightning Strikes on Wind Turbine

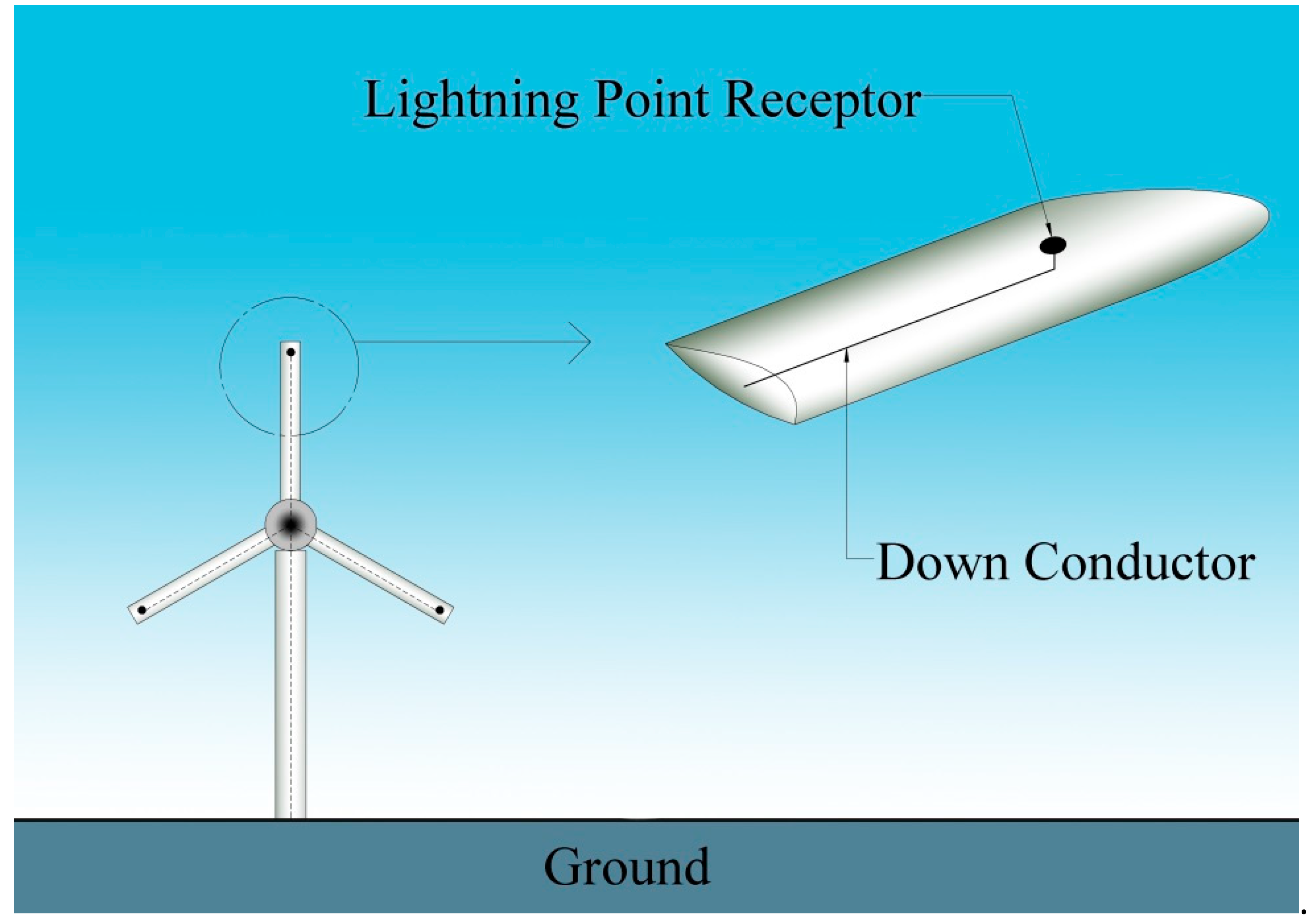

2.3. Lightning Protection and Mitigation System

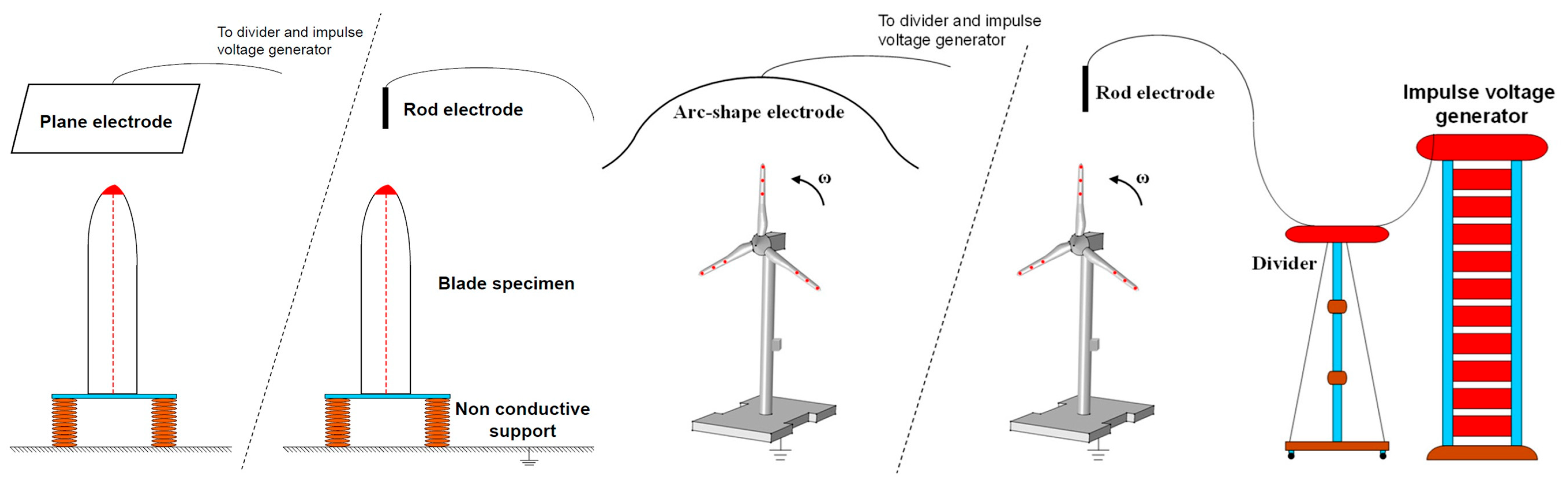

2.4. Modelling Lightning Effect on WTs

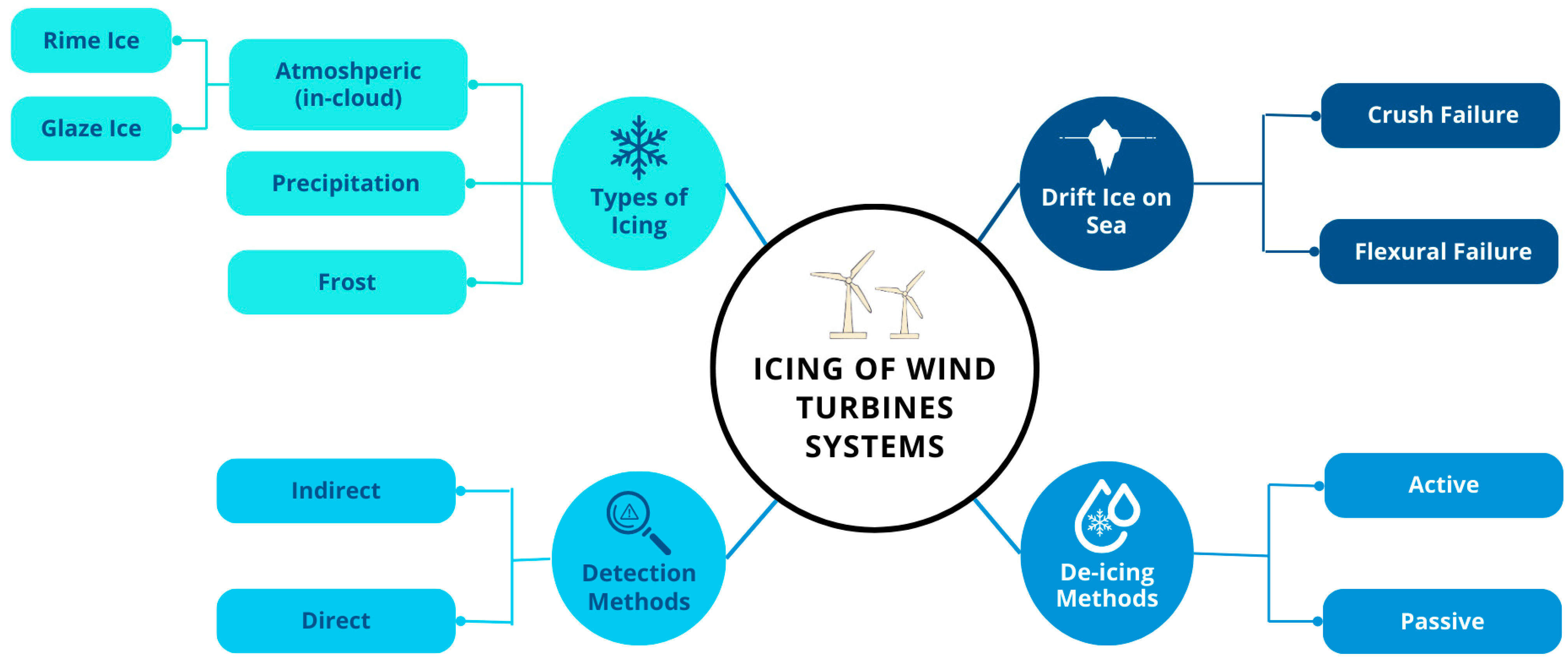

3. Icing and Wind Turbines

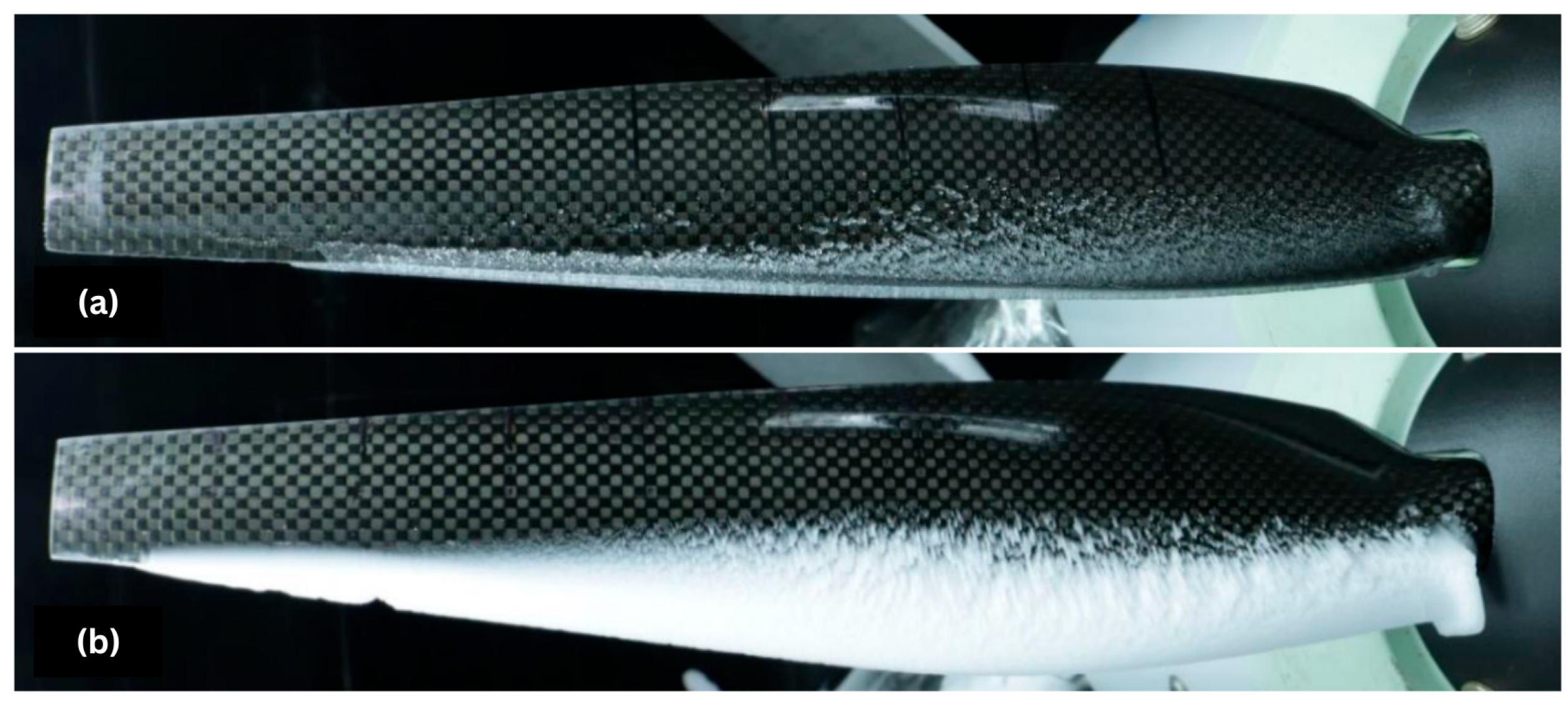

3.1. Blade Icing

3.1.1. Properties of Blade Icing and Factors Affecting Ice Accretion

- Liquid water content (LWC): Ice thickness increases with LWC because a higher water-to-air ratio increases the mass flux of droplets reaching the blade [109]. Recent studies further demonstrate that higher LWC produces thicker and denser accretion layers, accelerating the overall growth rate, particularly along the leading edge where droplet collection is strongest [92,110,111].

- Wind velocity: Higher wind velocity intensifies icing by increasing droplet collision efficiency [112]. The wind velocity can also modify both the shape and spatial extent of ice accretion by altering the local freezing fraction and collection patterns. In particular, the higher convective heat-transfer coefficient associated with increased wind speed promotes wetter, more irregular glaze-ice growth on wind-turbine airfoils [90]. Numerical glaze-icing simulations for wind-turbine blade tip sections further show that increasing airflow velocity enlarges the droplet impact area and icing range and increases the accumulated glaze-ice mass over time [82].

- Temperature: Temperature governs both ice shape and severity. Lower temperatures promote rapid freezing and streamlined rime-ice formation, while warmer sub-zero conditions favour glaze ice due to slower freezing [90]. Temperature has a limited influence on rime-ice geometry, but higher temperatures near the freezing point enable the runback-water behaviour typical of glaze ice [109]. The elevated temperatures also intensify runback water, which travels chordwise under aerodynamic shear and spanwise under centrifugal force, increasing the spread of unfrozen water and promoting broader, wetter glaze-ice accretion [113,114].

- Water droplet size: Water droplet size also influences ice accretion rate. Larger droplets, typically characterised by the median volumetric diameter (MVD), carry greater inertia, making them less responsive to the surrounding airflow and more likely to impinge on the blade surface, thereby increasing local accretion [112,113,115].

- Blade geometry: Both airfoil thickness and shape influence ice loading. Thicker sections provide larger droplet-impingement areas and thus accumulate more ice, with icing-induced thickness increases further promoting flow separation [116]. Symmetry also matters; symmetric profiles, such as NACA 0012, collect droplets almost evenly on both surfaces, while asymmetric sections like NACA 23012 show higher collision efficiency on the upper surface. In contrast, scaling a fixed airfoil shape to a larger chord can reduce overall collision efficiency and lower the ice-growth rate [112].

- Pitch angle: Increasing blade pitch can reduce ice accretion because the resulting decrease in effective angle of attack shifts the stagnation line and lowers droplet impingement efficiency [105]. This effect is particularly pronounced in glaze-ice conditions, where small reductions in impingement efficiency translate to noticeably lower accretion rates [90].

- Rotational speed: The rotational blade speed, often expressed through the tip-speed ratio, also affects icing behaviour. Lei et al. [107] showed that higher rotational velocities increased ice volume on a 1.5 MW turbine, even when the tip-speed ratio was held constant. Abbasi et al. [117] likewise observed that increasing the tip-speed ratio intensified performance losses under icing, indicating that faster rotation can aggravate icing-induced degradation. This occurs because greater rotational speed increases blade surface relative velocity and droplet impact kinetic energy—thereby raising droplet-capture efficiency and enhancing convective heat extraction—which accelerates ice growth [107,118].

- Turbine scale: Larger multi-megawatt turbines experience more severe icing because their long blades operate at higher tip speeds and sweep a much larger area, intercepting more droplets than smaller 1–3 MW machines. Field and simulation studies show that outer-span accretion intensifies sharply as rotor size increases, with large turbines exhibiting substantially thicker ice and greater aerodynamic penalties than smaller units [119,120,121]. In addition, offshore turbines are particularly susceptible due to higher humidity, sea-spray exposure and mixed-phase icing conditions [93], and this vulnerability increases as next-generation offshore machines continue to grow in size [122].

3.1.2. Adverse Effects of Blade Icing

3.1.3. Secondary Effects of Icing

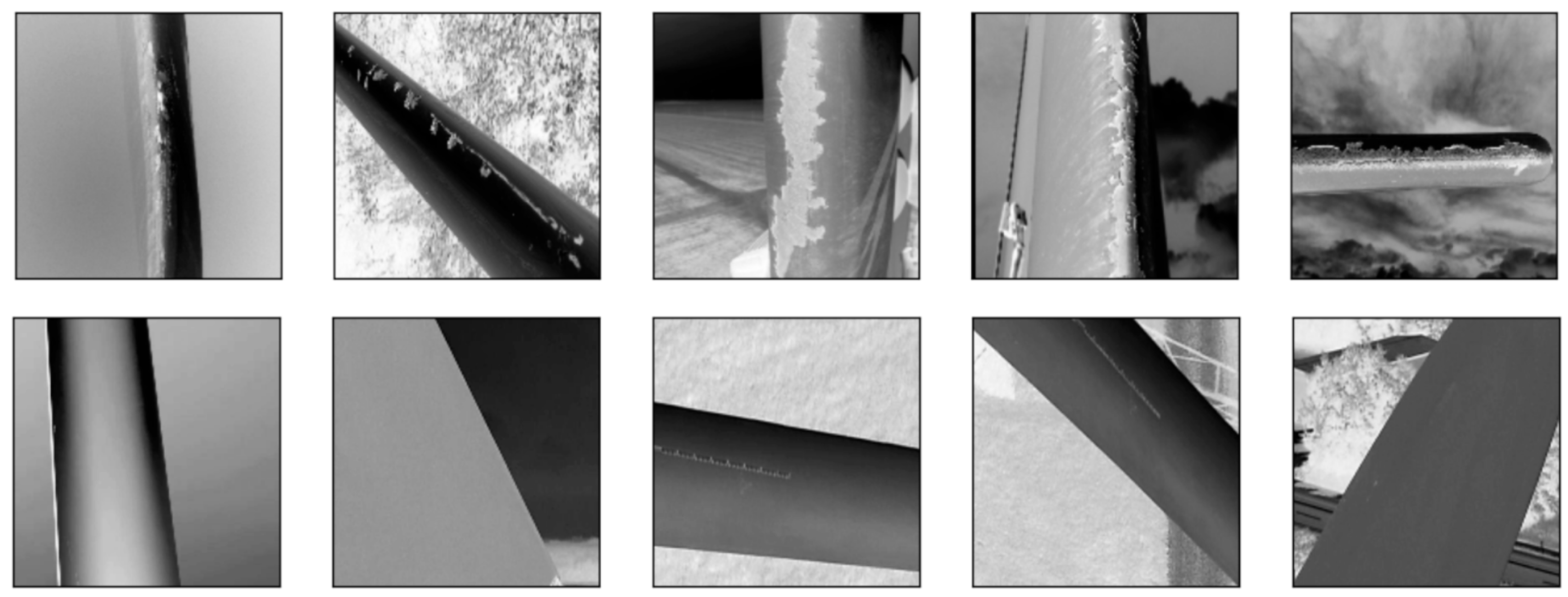

3.1.4. Ice Detection Method

- (i)

- Sensor placement near the blade tip

- The detection system is best placed in the outer-span region, where icing tends to initiate earliest because of the higher local relative velocity and greater droplet collision efficiency [136]. Multiple icing studies show that the blade tip consistently develops more severe accretion and accumulates larger glaze-ice masses than the mid-span or root areas [107,118].

- (ii)

- High sensitivity to early-stage icing

- The detection system must identify icing as soon as it begins, before surface roughening triggers boundary-layer disturbances. Once ice-induced turbulence forms, the resulting rise in convective heat loss makes de-icing significantly more energy-intensive [137]. Recent work on early ice monitoring supports this requirement, since very thin ice layers, with thicknesses of only a few hundred micrometres, have already been shown to be detectable before major aerodynamic degradation occurs [138,139].

- (iii)

- Capability to detect icing over large surface areas

- Ice accretion does not develop uniformly along the blade, since the local flow velocity, droplet trajectories and structural response vary from root to tip. As a result, the icing state at a single location cannot fully represent the condition of the entire rotor, and using only one monitoring point can lead to missed or underestimated accretion. Experiments have shown that leading-edge icing shifts the neutral axis and changes the strain ratios between different blade surfaces, confirming that icing effects vary significantly with measurement location [140].

Indirect Detection Method

Direct Detection Method

3.1.5. Protection and Mitigation: De-Icing and Anti-Icing Method

Passive Mitigation Methods

Active Mitigation Methods

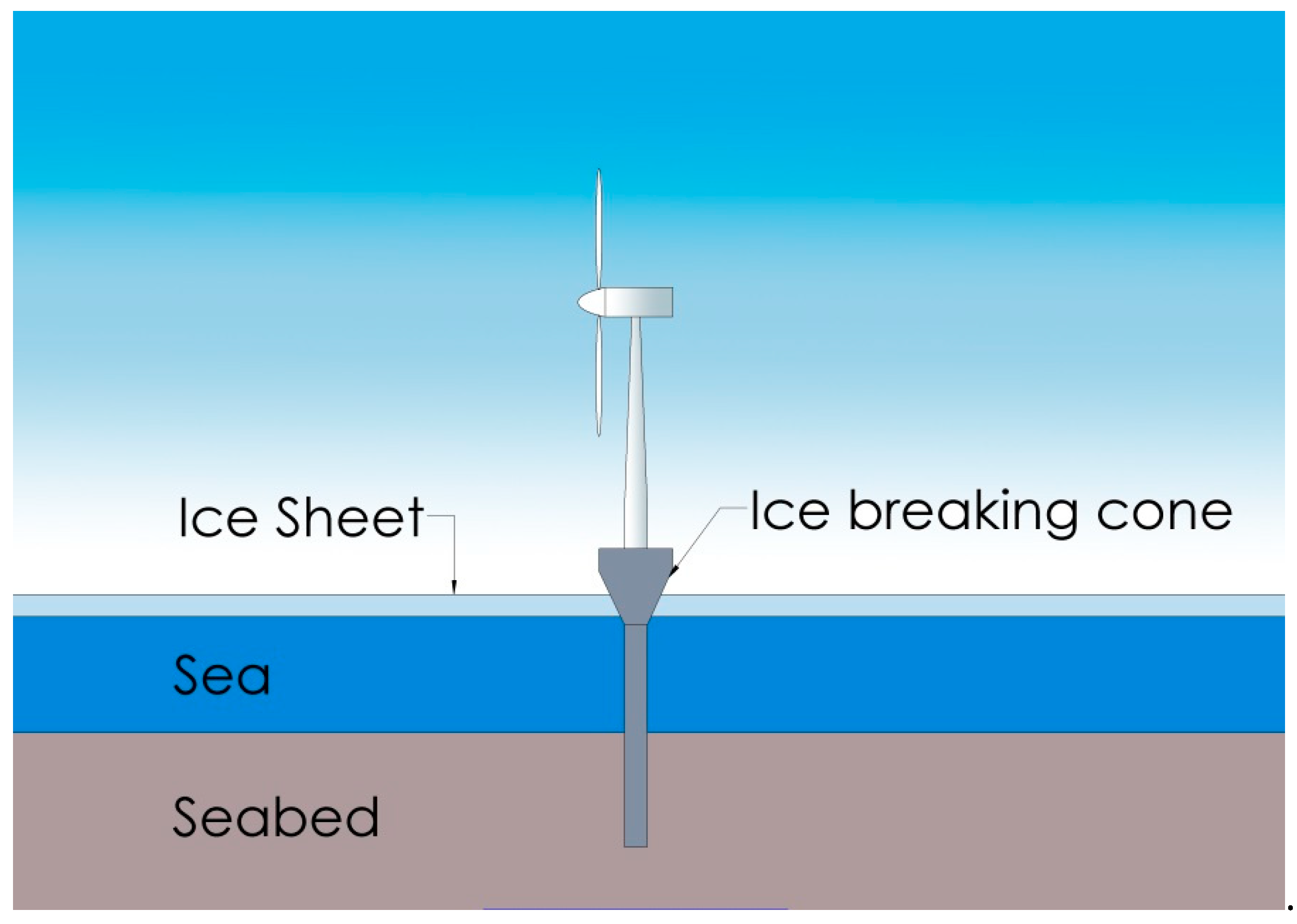

3.2. Interaction Between Drifting-Level Ice and Tower

4. Rain and Wind Turbines

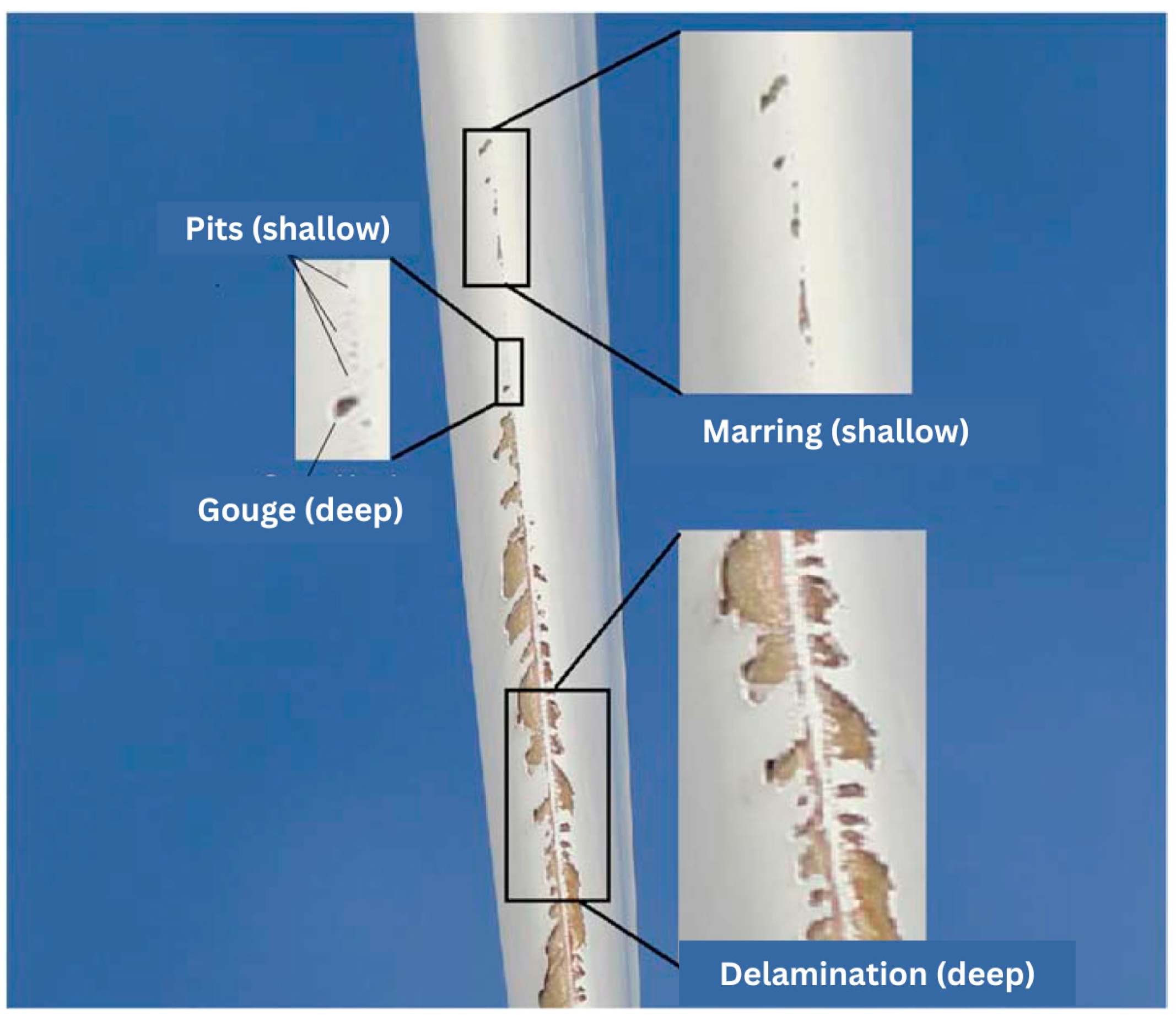

4.1. Blade Erosion

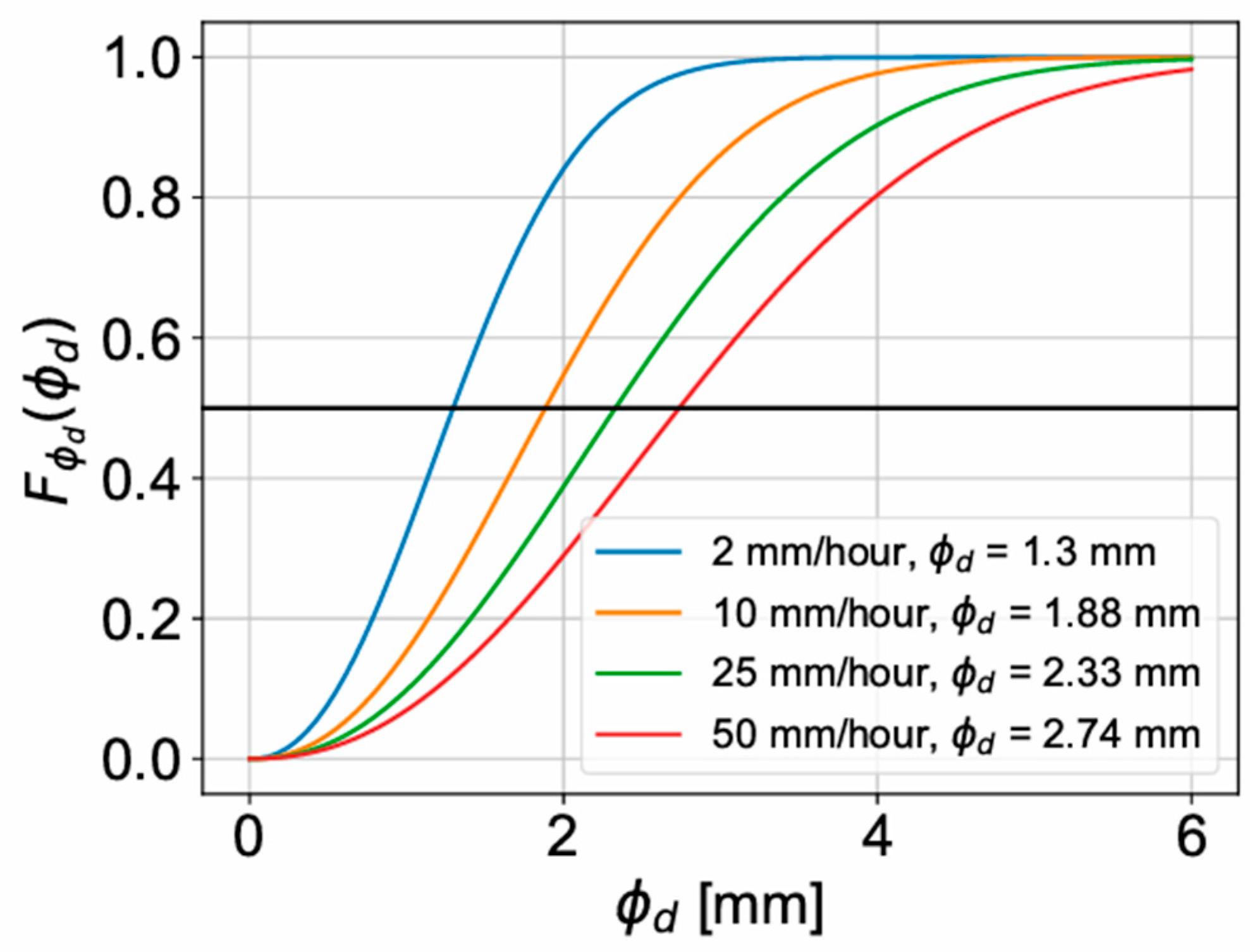

4.1.1. Dynamics of Erosion

4.1.2. Effect of Erosion

4.1.3. Protection and Mitigation Method

4.2. Effect of Water Film on the Blade

5. Meta-Analysis

5.1. Combined Effects and Interactions of Lightning, Icing, and Rain on Wind Turbines

5.2. Cross-Hazard Comparison of Wind Turbine Structural Materials and Performance

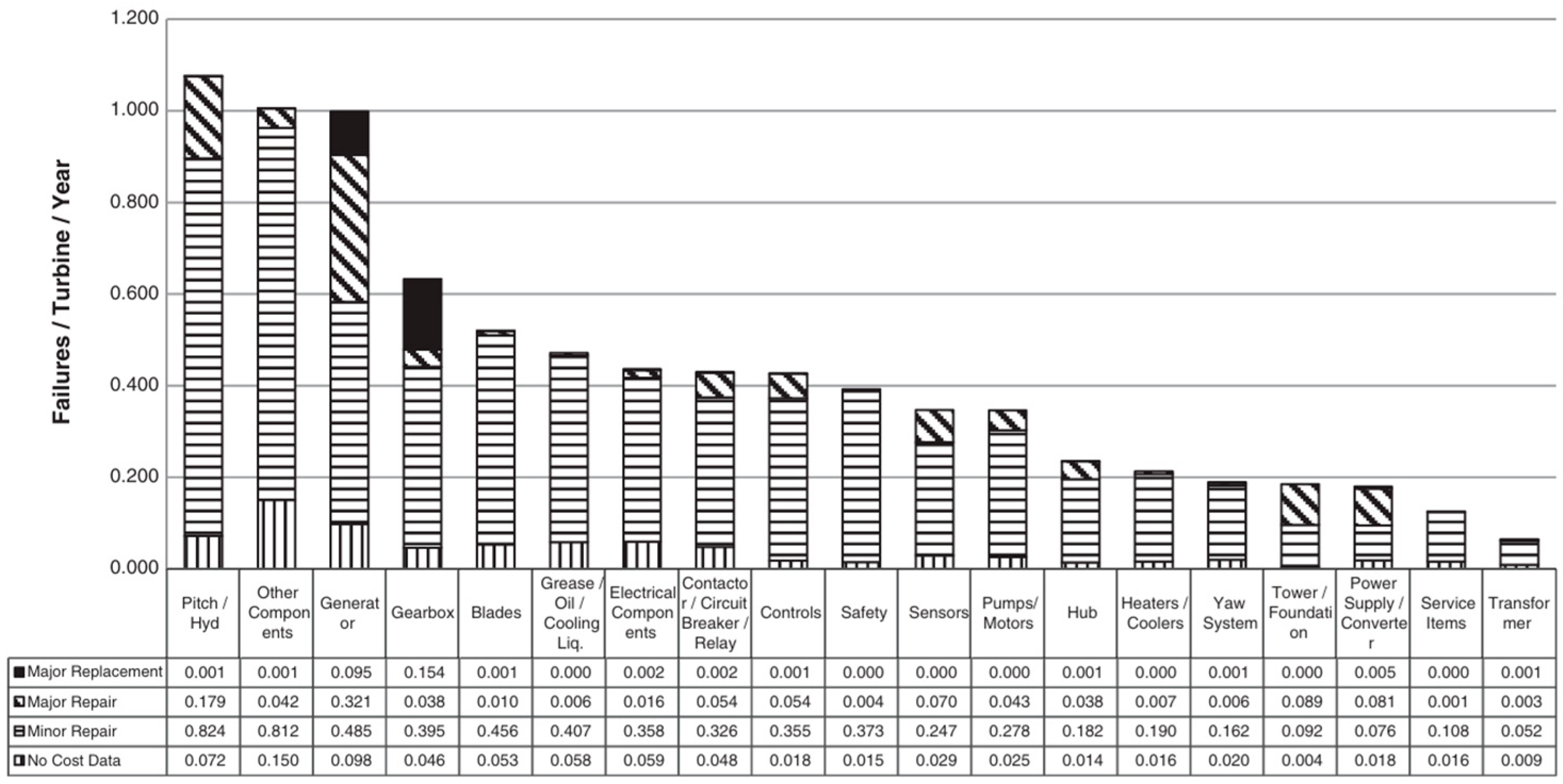

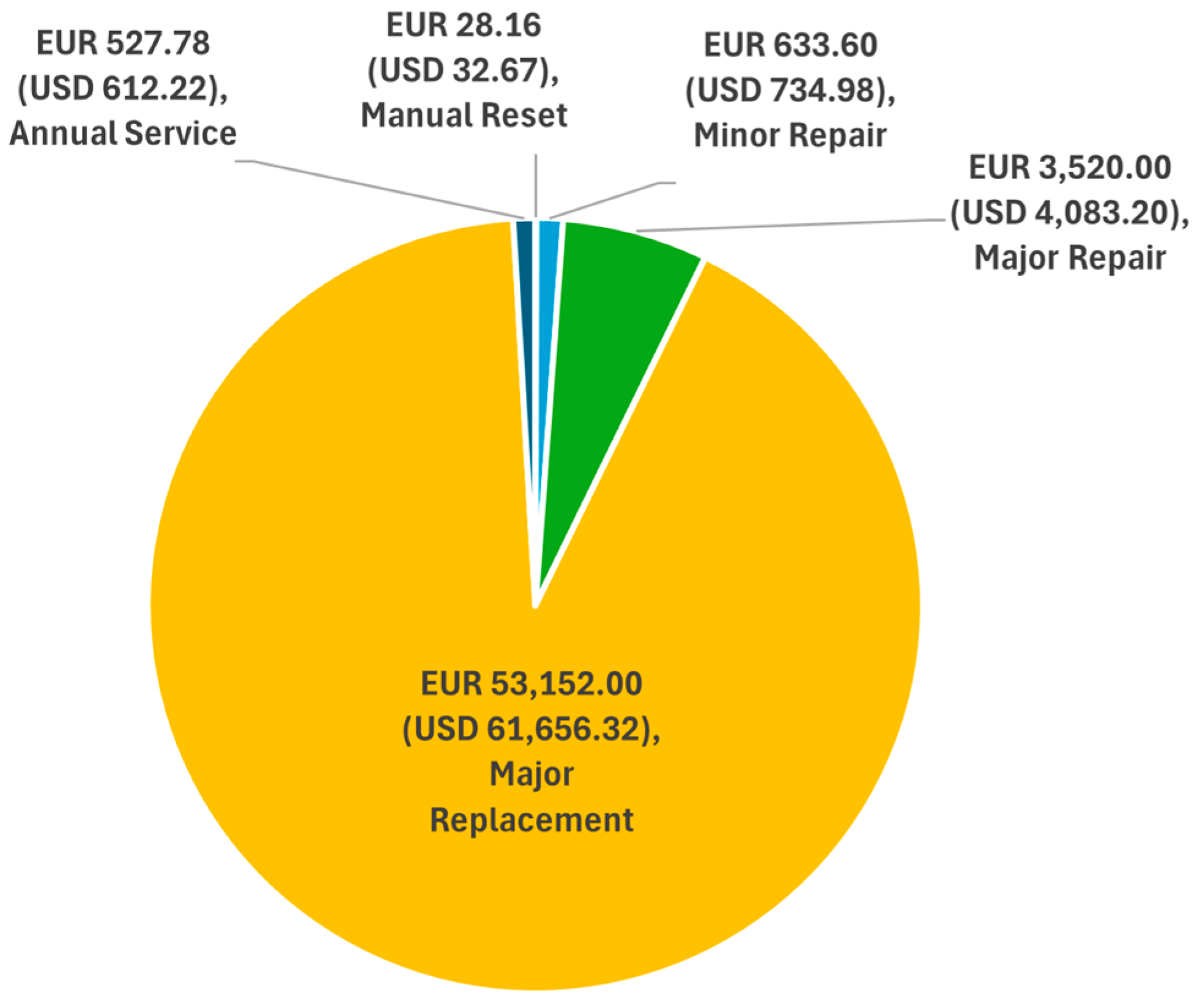

5.3. Economic Impact of Natural Hazards

5.4. Recommendations for Future Research Directions

- (i)

- Multi-hazard interaction modelling: The bibliometric analysis clearly shows that lightning, icing, and rain-related erosion form mostly separate research clusters, with almost no direct linkage between rain and lightning mechanisms. Future studies should prioritise multi-hazard coupling models, examining how sequential or concurrent hazards influence electrical behaviour, erosion vulnerability, icing adhesion, and structural degradation.

- (ii)

- Machine learning and data-driven prediction under 3 real operating conditions: While machine learning is used increasingly for icing detection and power-curve anomaly tracking, much of the existing work remains narrow in scope. Broader integration of machine learning, deep learning, and digital twins is needed to unify detection, prognosis, and optimisation across multiple hazards and turbine sizes, especially using large real-world SCADA datasets.

- (iii)

- Combined-effect experimental and numerical studies: Most current hazard studies isolate individual phenomena. There is a strong need for combined-effect experimental campaigns. For example, the studies on icing followed by lightning impulses, rain erosion under wet/iced conditions, or icing on previously eroded surfaces, will be useful in capturing real atmospheric complexity and supporting better design standards.

- (iv)

- Scaling laws and full-scale validation for large offshore turbines: A large proportion of existing research remains laboratory-scale or uses 1–3 MW aerodynamic models. With industry trends moving toward 10–15 MW turbines and future 20+ MW machines, new work must establish validated scaling laws, blade-size-dependent failure modes, and large-scale offshore test campaigns that reflect mixed-phase icing, marine corrosion, and increased lightning exposure.

- (v)

- Long-term economic modelling incorporating hazard-driven degradation: Current LCOE studies rarely incorporate hazard-induced maintenance trajectories or component deterioration. Future research should develop hazard-aware lifecycle cost models that couple environmental exposure, maintenance strategies, and reliability data, especially for offshore turbines where OPEX is highly sensitive to weather windows, vessel logistics, and scale-dependent repair costs.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Cloud-to-ground |

| EMTP | Electromagnetic transients program |

| GFRP | Glass fibre-reinforced plastics |

| HAWT | Horizontal axis wind turbine |

| IC | Intra-cloud |

| LCOE | Levelised Cost of Energy |

| LWC | Liquid water content |

| MVD | Median volumetric diameter |

| OTD | Optical transient detector |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditure |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PIV | Particle image velocimetry |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| SCADA | Supervisory control and data acquisition |

| WTs | Wind turbines |

References

- IRENA-International Renewable Energy Agency. Electricity Statistics by Region, Technology, Data Type and Year. Available online: https://pxweb.irena.org/pxweb/en/IRENASTAT/IRENASTAT__Power%20Capacity%20and%20Generation/Region_ELECSTAT_2025_H2_PX.px/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Global Wind Energy Council. GWEC Global Wind Report 2025; Global Wind Energy Council: Lisbon, Portugal, 2025; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Andrawus, J.A. Maintenance Optimisation for Wind Turbines. Ph.D. Thesis, The Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland, 2008. Available online: https://rgu-repository.worktribe.com/output/247754 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Martulli, L.M.; Diani, M.; Sabetta, G.; Bontumasi, S.; Colledani, M.; Bernasconi, A. Critical review of current wind turbine blades’ design and materials and their influence on the end-of-life management of wind turbines. Eng. Struct. 2025, 327, 119625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Al-Obaidi, A.S.M.; Hao, L.C. A comprehensive review of innovative wind turbine airfoil and blade designs: Toward enhanced efficiency and sustainability. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y.; Cruden, A.; Ng, J.-H.; Wong, K.-H. Variable designs of vertical axis wind turbines—A review. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1437800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.W.; Megat Iskandar Hashim, A.H.B.; Conrad, F.; Fazlizan, A.; Wong, K.-H. Exploring biomimicry in wind and hydrokinetic turbine design: Bridging nature and engineering. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2025, 20, 051002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.H.; Chong, W.T.; Sukiman, N.L.; Poh, S.C.; Shiah, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-T. Performance enhancements on vertical axis wind turbines using flow augmentation systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 904–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millen, S.L.J.; Murphy, A. Modelling and analysis of simulated lightning strike tests: A review. Compos. Struct. 2021, 274, 114347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Yokozeki, T.; Karch, C.; Hassen, A.A.; Hershey, C.J.; Kim, S.; Lindahl, J.M.; Barnes, A.; Bandari, Y.K.; Kunc, V. Factors affecting direct lightning strike damage to fiber reinforced composites: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 183, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, N.; Aggarwal, R.K. The impact of multiple lightning strokes on the energy absorbed by MOV surge arresters in wind farms during direct lightning strikes. Renew. Energy 2015, 83, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quayson-Sackey, E.; Nyantekyi-Kwakye, B.; Ayetor, G.K. Technological advancements for anti-icing and de-icing offshore wind turbine blades. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 231, 104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Superhydrophobic coating for blade surface ice-phobic properties of wind turbines: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 187, 108145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okulov, V.; Kabardin, I.; Mukhin, D.; Stepanov, K.; Okulova, N. Physical De-Icing Techniques for Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2021, 14, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras Montoya, L.T.; Lain, S.; Ilinca, A. A Review on the Estimation of Power Loss Due to Icing in Wind Turbines. Energies 2022, 15, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X. A Review of Wind Turbine Icing and Anti/De-Icing Technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, N. Review: Fundamentals of liquid droplet impingement and rain erosion of wind turbine blade. Next Energy 2025, 8, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, K.; Nash, J.W.; Reaburn, G.; Stack, M.M. On analytical tools for assessing the raindrop erosion of wind turbine blades. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lei, X.; Lai, Y.; Qin, M.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Dai, K.; Yang, Y.; Bashir, M. Analysis of dynamic response of offshore wind turbines subjected to earthquake loadings and the corresponding mitigation measures: A review. Ocean Eng. 2024, 311, 118892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xue, Y.; He, C.; Zhao, Y. Review of the Typical Damage and Damage-Detection Methods of Large Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2022, 15, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Papadakis, N.; Ntintakis, I. A Comprehensive Analysis of Wind Turbine Blade Damage. Energies 2021, 14, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Hrkać, F.; Stoić, M.; Hradovi, I. Environmental Impact of Wind Farms. Environments 2024, 11, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.-S.; Pien, K.-C.; Liou, W.-J.; Cheng, T.-C. Site Selection for Offshore Wind Power Farms with Natural Disaster Risk Assessment: A Case Study of the Waters off Taiwan’s West Coast. Energies 2024, 17, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.; Pathak, C.; Alduse, B. Review of Natural Hazard Risks for Wind Farms. Energies 2023, 16, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvi, E.; Douvi, D. Aerodynamic Characteristics of Wind Turbines Operating under Hazard Environmental Conditions: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Gutierrez, B.; Sanchez-Cortez, L.; Hinojosa-Manrique, M.; Lozada-Pedraza, A.; Ninaquispe-Soto, M.; Montaño-Pisfil, J.; Gutiérrez-Tirado, R.; Chávez-Sánchez, W.; Romero-Goytendia, L.; Díaz-Aliaga, J.; et al. Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines in Emerging Energy Applications (1979–2025): Global Trends and Technological Gaps Revealed by a Bibliometric Analysis and Review. Energies 2025, 18, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, H.J.; Blakeslee, R.J.; Boccippio, D.J.; Boeck, W.L.; Buechler, D.E.; Driscoll, K.T.; Goodman, S.J.; Hall, J.M.; Koshak, W.J.; Mach, D.M.; et al. Global frequency and distribution of lightning as observed from space by the Optical Transient Detector. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, ACL 4-1–ACL 4-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfur, M.; Price, C.; Silverman, J.; Wishkerman, A. Why is lightning more intense over the oceans? J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2020, 202, 105259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalel, D.; Mourad, M.; Sihem, G. Contribution to the study of the aggression of lightning phenomenon on the wind turbine structures. Wind Eng. 2016, 40, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushakow, B. Effective Lightning Protection for Wind Turbine Generators. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2007, 22, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoh, Y. A new lightning protection system for wind turbines using two ring-shaped electrodes. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2006, 1, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, I.; Jenkins, N.; Pandiaraj, K. Lightning protection for wind turbine blades and bearings. Wind Energy 2001, 4, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.A. CHAPTER 11-The Lightning Discharge. In Atmospheric Electricity; Chalmers, J.A., Ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 235–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhupanska, O.I. Lightning strike thermal damage model for glass fiber reinforced polymer matrix composites and its application to wind turbine blades. Compos. Struct. 2015, 132, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, Q.; Guo, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.D. Puncture position on wind turbine blades and arc path evolution under lightning strikes. Mater. Des. 2017, 122, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Han, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Yu, F.; Li, Q.; Zhu, R.; Zhong, Z. Statistical analysis of the spatio-temporal characteristics of multiple return strokes cloud-to-ground lightning parameters in Guangdong Province, China. Atmos. Res. 2025, 323, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Theethayi, N.; Diendorfer, G.; Thottappillil, R.; Rakov, V.A. On estimation of the effective height of towers on mountaintops in lightning incidence studies. J. Electrost. 2010, 68, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, N.; Montanyà, J.; Salvador, A.; van der Velde, O.A.; López, J.A. Thunderstorm characteristics favouring downward and upward lightning to wind turbines. Atmos. Res. 2018, 214, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, V. Key issues to define a method of lightning risk assessment for wind farms. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2018, 159, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, M.; Long, M.; Schulz, W.; Thottappillil, R. On the estimation of the lightning incidence to offshore wind farms. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2018, 157, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanyà, J.; van der Velde, O.; Williams, E.R. Lightning discharges produced by wind turbines. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2014, 119, 1455–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radičević, B.M.; Savić, M.S.; Madsen, S.F.; Badea, I. Impact of wind turbine blade rotation on the lightning strike incidence–A theoretical and experimental study using a reduced-size model. Energy 2012, 45, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, N.; He, T.; Gu, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, T. Analysis of the cloud-to-ground lightning characteristics before and after installation of the coastal and inland wind farms in China. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 190, 106835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, S. Lightning protection of wind turbine blades. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2013, 94, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Yoshikawa, E.; Adachi, T.; Kusunoki, K.; Hayashi, S.; Inoue, H. Three-dimensional radio images of winter lightning in Japan and characteristics of associated charge structure. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2019, 14, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, M.; Michishita, K.; Yokoyama, S. Influence of the −10 °C isotherm altitudes on winter lightning incidence at wind turbines in coastal areas of the Sea of Japan. Atmos. Res. 2023, 296, 107071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinga, G.A.; Niedzwecki, J.M. Nearshore regional behavior of lightning interaction with wind turbines. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2016, 1, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yamamoto, K.; Noda, T.; Yokoyama, S.; Ametani, A. An experimental study of lightning overvoltages in wind turbine generation systems using a reduced-size model. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2007, 158, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Liu, C.; Bian, X.; Lo, K.L.; Li, D. Numerical analysis of lightning attachment to wind turbine blade. Renew. Energy 2018, 116, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhupanska, O.I. Estimation of the electric fields and dielectric breakdown in non-conductive wind turbine blades subjected to a lightning stepped leader. Wind Energy 2017, 20, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, L.V. Traveling Waves Due to Lightning. Trans. Am. Inst. Electr. Eng. 1929, 48, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-L.; Chang, H.-C.; Kuo, C.-C.; Huang, C.-K. Transient overvoltage phenomena on the control system of wind turbines due to lightning strike. Renew. Energy 2013, 57, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Tao, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, B. Analysis and suppression measures of lightning transient overvoltage in the signal cable of wind turbines. Wind Energy 2018, 21, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatinasab, R.; Kermani, B.; Gholinezhad, J. Transient modeling of the wind farms in order to analysis the lightning related overvoltages. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarajčev, P.; Sarajčev, I.; Goić, R. Transient EMF induced in LV cables due to wind turbine direct lightning strike. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2010, 80, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarajcev, P.; Goic, R. Estimation of lightning current amplitudes incident to wind turbines in exposed locations. Wind Energy 2015, 18, 1515–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yang, Q.; Fang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wen, X.; Lan, L.; Deng, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, S. Scaled experiment and observation of the lightning discharge process of rotating wind turbines under different shapes of high-voltage electrodes in the laboratory. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 231, 110339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, F.; Milardic, V.; Milos, D.; Filipovic-Grcic, B.; Stipetic, N.; Franc, B. Development and laboratory testing of a lightning current measurement system for wind turbines. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 223, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Siew, W.H.; Li, Q.; Shi, W. On the Lightning Attachment Process of Wind Turbine–Observation, Experiments and Modelling. Machines 2025, 13, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L. A comprehensive lightning surge analysis in offshore wind farm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 211, 108259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Y. Experimental Research and Simulation Analysis of Lightning Ablation Damage Characteristics of Megawatt Wind Turbine Blades. Metals 2021, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudani, A.A.M.; Vryonis, O.; Lewin, P.L.; Golosnoy, I.O.; Kremer, J.; Klein, H.; Thomsen, O.T. Numerical simulation of lightning strike damage to wind turbine blades and validation against conducted current test data. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 152, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucsi, V.; Ayub, A.S.; Muhammad-Sukki, F.; Zulkipli, M.; Muhtazaruddin, M.N.; Mohd Saudi, A.S.; Ardila-Rey, J.A. Lightning Protection Methods for Wind Turbine Blades: An Alternative Approach. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.-M.; Kang, S.-M.; Ju, M. Analysis of polarity characteristics of lightning attachment and protection to wind turbine blades. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Shi, X.; Jiang, Z. Investigation of lightning attachment characteristics of wind turbine blades with different receptors. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipio, R.; De Conti, A.; Duarte, N.; Correia de Barros, M.T. Bare versus insulated conductors for improving the lightning response of interconnected wind turbine grounding systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 197, 107320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi-Kazemi, A.A.; Eftekhari, P. Investigation of the impact of the grounding of wind farms on the distribution of transient over-voltages caused by lightning strikes. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 220, 109362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.A.; Mohammadirad, A.; Shayegani Akmal, A.A. Surge analysis on wind farm considering lightning strike to multi-blade. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary, A.; Behdani, B.; Niasar, M.G.; Popov, M. Wind farm transformer protection against lightning transients using air core reactor and resistor. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 249, 112036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worms, K.; Klamouris, C.; Wegh, F.; Meder, L.; Volkmer, D.; Philipps, S.P.; Reichmuth, S.K.; Helmers, H.; Kunadt, A.; Vourvoulakis, J.; et al. Reliable and lightning-safe monitoring of wind turbine rotor blades using optically powered sensors. Wind Energy 2017, 20, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Daud, S.Z.; Mustapha, F.; Adzis, Z. Lightning strike evaluation on composite and biocomposite vertical-axis wind turbine blade using structural health monitoring approach. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2018, 29, 3444–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Bian, X.; Zhong, Y.; Shen, J. Comparative study of lightning damage to various nacelle cover materials of wind turbines. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 241, 111342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-24:2019; Wind Energy Generation Systems-Part 24: Lightning Protection. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Xiaohui, W.; Zhang, X. Calculation of electromagnetic induction inside a wind turbine tower struck by lightning. Wind Energy 2010, 13, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, W.; Wen, Y. Analysis of the lightning-attractive radius for wind turbines considering the developing process of positive attachment leader. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 3481–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarajcev, P.; Vasilj, J.; Jakus, D. Monte–Carlo analysis of wind farm lightning-surge transients aided by LINET lightning-detection network data. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Qi, Q.; Lyu, W. Simulation of Cloud-to-Ground Lightning Strikes to Wind Turbines Considering Polarity Effect Based on an Improved Stochastic Lightning Model. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X. An improved approach for modeling lightning transients of wind turbines. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 101, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulazia, A.; Sáenz, J.; Ibarra-Berastegi, G.; González-Rojí, S.J.; Carreno-Madinabeitia, S. Global estimations of wind energy potential considering seasonal air density changes. Energy 2019, 187, 115938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, O.; Ilinca, A. Anti-icing and de-icing techniques for wind turbines: Critical review. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 65, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleksabet, Z.; Kozinski, J.; Tarokh, A. Impact of ice accretion on the aerodynamic characteristics of Wind turbine airfoil at low Reynolds numbers. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 239, 104618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, W. Numerical Study on Glaze Ice Accretion Characteristics over Time for a NACA 0012 Airfoil. Coatings 2023, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.; Villeneuve, E.; Béland, M.; Lapalme, M. Wind Tunnel Investigation of the Icing of a Drone Rotor in Forward Flight. Drones 2024, 8, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Dong, Q.; Yang, Z. A stereoscopic PIV study of the effect of rime ice on the vortex structures in the wake of a wind turbine. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2014, 134, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, N. Icing on a small horizontal-axis wind turbine—Part 1: Glaze ice profiles. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1992, 45, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Hu, H. An experimental study on the aerodynamic performance degradation of a wind turbine blade model induced by ice accretion process. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraj, A.G.; Bibeau, E.L. Measurement method and results of ice adhesion force on the curved surface of a wind turbine blade. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ru, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z. Study on the Effect of Mixed-Phase Icing on the Aerodynamic Characteristics of Wind Turbine Airfoil. Energies 2025, 18, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Li, H.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Qiu, G.; He, G.; Liu, Y. 3D numerical simulation of aerodynamic performance of iced contaminated wind turbine rotors. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 148, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ru, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z. Numerical Investigation of Wind Turbine Airfoil Icing and Its Influencing Factors under Mixed-Phase Conditions. Energies 2024, 17, 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, F.; Contreras Montoya, L.T.; Ilinca, A. Review of Wind Turbine Icing Modelling Approaches. Energies 2021, 14, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lian, Y.; Feng, F. A parametric study on the effect of liquid water content and droplet median volume diameter on the ice distribution and anti-icing heat estimation of a wind turbine airfoil. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Zhao, P.; Shen, H.; Yang, S.; Chi, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, F. An Experimental Study of Surface Icing Characteristics on Blade Airfoil for Offshore Wind Turbines: Effects of Chord Length and Angle of Attack. Coatings 2024, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shi, W.; Chi, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, W. A Visualization Experiment on Icing Characteristics of a Saline Water Droplet on the Surface of an Aluminum Plate. Coatings 2024, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosencrans, D.; Lundquist, J.K.; Optis, M.; Bodini, N. The effects of wind farm wakes on freezing sea spray in the mid-Atlantic offshore wind energy areas. Wind Energy Sci. 2025, 10, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Bricker, J.D.; Fujisaki-Manome, A.; Garcia, F.E. Characteristics of ice-structure-soil interaction of an offshore wind turbine. Ocean Eng. 2024, 295, 116975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Liang, J.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Ren, X.; Qiu, G. Study on small wind turbine icing and its performance. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 134, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, C. Numerical simulation for in-cloud icing of three-dimensional wind turbine blades. Simulation 2017, 94, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Du, Z. Numerical simulation of rime ice on NREL Phase VI blade. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 178, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, G.M.; Pope, K.; Muzychka, Y.S. Effects of blade design on ice accretion for horizontal axis wind turbines. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 173, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Farzaneh, M. A CFD approach for modeling the rime-ice accretion process on a horizontal-axis wind turbine. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2010, 98, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabardin, I.; Dvoynishnikov, S.; Gordienko, M.; Kakaulin, S.; Ledovsky, V.; Gusev, G.; Zuev, V.; Okulov, V. Optical Methods for Measuring Icing of Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2021, 14, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y. Icing wind tunnel test of ice distribution characteristics on the NACA63–412 blade airfoil of wind turbine. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Qiu, G.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X.; McClure, G.; Liu, Y. Numerical and experimental investigation of threshold de-icing heat flux of wind turbine. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 174, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhu, X.; Hu, C.; Chen, J.; Du, Z. Wind turbines ice distribution and load response under icing conditions. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homola, M.C.; Virk, M.S.; Nicklasson, P.J.; Sundsbø, P.A. Performance losses due to ice accretion for a 5 MW wind turbine. Wind Energy 2012, 15, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Han, Y.; Feng, F. Enhanced Analysis of Ice Accretion on Rotating Blades of Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbines Using Advanced 3D Scanning Technology. Coatings 2024, 14, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Feng, F.; Tagawa, K. Characteristics of ice accretions on blade of the straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbine rotating at low tip speed ratio. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 145, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Palacios, J.; Schmitz, S. Scaled ice accretion experiments on a rotating wind turbine blade. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2012, 109, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, H.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Wang, F. A correction method for wind power forecast considering the dynamic process of wind turbine icing. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 246, 111669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.; Zhang, D.; Liu, C.; Kong, X.; Wen, H.; Yuan, Y.; Ji, Y. Analysis of the Characteristics of Ice Accretion on the Surface of Wind Turbine Blades Under Different Environmental Conditions. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.Y.; Virk, M.S. Study of ice accretion along symmetric and asymmetric airfoils. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 179, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, M.; Virk, M.S. Ice Accretion on Rotary-Wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles—A Review Study. Aerospace 2023, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homola, M.C.; Virk, M.S.; Wallenius, T.; Nicklasson, P.J.; Sundsbø, P.A. Effect of atmospheric temperature and droplet size variation on ice accretion of wind turbine blades. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2010, 98, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, P.; Palacios, J.; Schmitz, S. Effect of icing roughness on wind turbine power production. Wind Energy 2017, 20, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizhuma, Z.; Kim, T.; Son, C. Numerical method to predict ice accretion shapes and performance penalties for rotating vertical axis wind turbines under icing conditions. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 216, 104708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Mahmoodi, A.; Joodaki, A. A Numerical Study on Effects of Ice Formation on Vertical-axis Wind Turbine Performance and Flow Field at Optimal Tip Speed Ratio. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2024, 17, 1896–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, G.M.; Pope, K.; Naterer, G.F. Extended scaling approach for droplet flow and glaze ice accretion on a rotating wind turbine blade. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 233, 105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Lei, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Feng, F. The Icing Characteristics of a 1.5 MW Wind Turbine Blade and Its Influence on the Blade Mechanical Properties. Coatings 2024, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Hu, H. Wind turbine icing characteristics and icing-induced power losses to utility-scale wind turbines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2111461118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Z.; Yi, H.; Chang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Xia, L. Comprehensive Analysis of the Impact of the Icing of Wind Turbine Blades on Power Loss in Cold Regions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, O.; Carroll, J.; Howland, M. Analysing the cost impact of failure rates for the next generation of offshore wind turbines. Wind Energy 2024, 27, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Li, H.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Qiu, G.; McClure, G.; Yang, H. Study of ice accretion feature and power characteristics of wind turbines at natural icing environment. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 147, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, J.; Wen, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D. Impact of Blade Ice Coverage on Wind Turbine Power Generation Efficiency: A Combined CFD and Wind Tunnel Study. Energies 2025, 18, 3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrimpas, G.A.; Kleani, K.; Mijatovic, N.; Sweeney, C.W.; Jensen, B.B.; Holboell, J. Detection of icing on wind turbine blades by means of vibration and power curve analysis. Wind Energy 2016, 19, 1819–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Rotea, M.; Kehtarnavaz, N. An Ensemble Network for High-Accuracy and Long-Term Forecasting of Icing on Wind Turbines. Sensors 2024, 24, 8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C. Ice mitigation in alpine wind farm: A centrifugal force-based icing-throw strategy study at natural icing environment. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 236, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, X. A Strategy of Candle Soot-Based Photothermal Icephobic Superhydrophobic Surface. Coatings 2024, 14, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, T.; Baring-Gould, I.; Durstewitz, M.; Horbaty, R.; Lacroix, A.; Peltola, E.; Ronsten, G.; Tallhaug, L.; Wallenius, T. State-of-The-Art of Wind Energy in Cold Climates; VTT Working Papers 152; VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 2010; Available online: https://publications.vtt.fi/pdf/workingpapers/2010/W152.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Godreau, C.; Paquet, Y.; Froidevaux, P.; Krenn, A.; Wickman, H. Ice Detection Guidelines for Wind Energy Applications; IEA Wind TCP: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Tao, T.; Liu, Y.; Hu, H. A field study of ice accretion and its effects on the power production of utility-scale wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2021, 167, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Taylor, P.; Salmon, J. A model of ice throw trajectories from wind turbines. Wind Energy 2012, 15, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapalik, M.; Zajicek, L.; Purker, S. Ice aggregation and ice throw from small wind turbines. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 192, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjallar, M.R.A. Modelling Ice Throw Tracjectories from Wind Turbines. Master’s Thesis, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Homola, M.C.; Nicklasson, P.J.; Sundsbø, P.A. Ice sensors for wind turbines. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2006, 46, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevrani, H.; Afzal, F.; Virk, M.S. Review of Icing Effects on Wind Turbine in Cold Regions. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Tokyo, Japan, 1–3 June 2018; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Makkonen, L.; Laakso, T.; Marjaniemi, M.; Finstad, K.J. Modelling and prevention of ice accretion on wind turbines. Wind Eng. 2001, 25, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlanduit, S.; De Vooght, A.; De Kerf, T. Surface Ice Detection Using Hyperspectral Imaging and Machine Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekuviene, R.; Samaitis, V.; Jankauskas, A.; Sadaghiani, A.K.; Saeidiharzand, S.; Kosar, A. Early-Stage Ice Detection Utilizing High-Order Ultrasonic Guided Waves. Sensors 2024, 24, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Xu, Y. Icing Monitoring of Wind Turbine Blade Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors and Strain Ratio Index. Energies 2025, 18, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madi, E.; Pope, K.; Huang, W.; Iqbal, T. A review of integrating ice detection and mitigation for wind turbine blades. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaverin, V.; Nurmaganbetova, G.; Em, G.; Issenov, S.; Tatkeyeva, G.; Maussymbayeva, A. Combined Wind Turbine Protection System. Energies 2024, 17, 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, T.; Peltola, E.; Tammelin, B. Wind turbines in icing environment: Improvement of tools for siting, certification and operation: New icetools. In Ilmatieteen Laitos Raportteja; Ilmatieteen Laitos: Helsinki, Finland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rizk, P.; Younes, R.; Ilinca, A.; Khoder, J. Wind turbine ice detection using hyperspectral imaging. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 26, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.N.; Byrkjedal, Ø.; Hahmann, A.N.; Clausen, N.-E.; Žagar, M. Ice detection on wind turbines using the observed power curve. Wind Energy 2016, 19, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Jiang, Y.; Song, W.; Lu, K.-H.; Zhu, T. Short-Term Wind Turbine Blade Icing Wind Power Prediction Based on PCA-fLsm. Energies 2024, 17, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Furusawa, Y.; Nishihara, N.; Indo, K.; Morikawa, H.; Iida, M. SCADA-Data-Based Static Yaw Misalignment Estimation for Wind Turbines. In Proceedings of the 43th Wind Energy Symposium, Online, 18–19 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Astolfi, D.; De Caro, F.; Vaccaro, A. Characterizing the Wake Effects on Wind Power Generator Operation by Data-Driven Techniques. Energies 2023, 16, 5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, M.; Alla, A.A.; Lütjen, M.; Ohlendorf, J.-H.; Freitag, M.; Thoben, K.-D.; Zimnol, F.; Greulich, A. Ice prediction for wind turbine rotor blades with time series data and a deep learning approach. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 206, 103741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Hu, L.; Dong, L.; Du, S.; Xu, D. Experimental Study on Anti-Icing of Robust TiO2/Polyurea Superhydrophobic Coating. Coatings 2023, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Z.; Hong, H.; Zhang, L. Research and Application of Microwave Microstrip Transmission Line-Based Icing Detection Methods for Wind Turbine Blades. Sensors 2025, 25, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, P.; Lemay, J.; Ruel, J.; Bégin-Drolet, A. A new atmospheric icing detector based on thermally heated cylindrical probes for wind turbine applications. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 148, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekou, D.J. 10-Probabilistic design of wind turbine blades. In Advances in Wind Turbine Blade Design and Materials; Brøndsted, P., Nijssen, R.P.L., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridgeshire, UK, 2013; pp. 325–359. [Google Scholar]

- Shajiee, S.; Pao, L.Y.; Wagner, P.N.; Moore, E.D.; McLeod, R.R. Direct ice sensing and localized closed-loop heating for active de-icing of wind turbine blades. In Proceedings of the 2013 American Control Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 17–19 June 2013; pp. 634–639. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Muñoz, C.Q.; García Márquez, F.P.; Sánchez Tomás, J.M. Ice detection using thermal infrared radiometry on wind turbine blades. Measurement 2016, 93, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, S.; Feytout, B.; Lanusse, P.; Sabatier, J. A Solution for Ice Accretion Detection on Wind Turbine Blades. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics, Madrid, Spain, 26–28 July 2017; pp. 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Fakorede, O.; Feger, Z.; Ibrahim, H.; Ilinca, A.; Perron, J.; Masson, C. Ice protection systems for wind turbines in cold climate: Characteristics, comparisons and analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Reich, A.; Anderson, D.; Reich, A. Tests of the performance of coatings for low ice adhesion. In Proceedings of the 35th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 6–9 January 1997; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Fürbacher, R.; Liedl, G.; Grünsteidl, G.; Otto, A. Icing Wind Tunnel and Erosion Field Tests of Superhydrophobic Surfaces Caused by Femtosecond Laser Processing. Wind 2024, 4, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Feng, F. Preparation of n-Tetradecane Phase Change Microencapsulated Polyurethane Coating and Experiment on Anti-Icing Performance for Wind Turbine Blades. Coatings 2024, 14, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Qiu, G.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X.; McClure, G.; Yang, H. Numerical and field experimental investigation of wind turbine dynamic de-icing process. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 175, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, P.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. Numerical and Experimental Study on Deicing of Wind Turbine Blades by Electric Heating Under Complex Flow Field. Machines 2025, 13, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinca, A. Analysis and Mitigation of Icing Effects on Wind Turbines. In Wind Turbines; Al-Bahadly, I., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Xie, P.; Jiang, Z.; Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Ning, K. Numerical and experimental analysis of the lightning transient behavior of electric heating deicing control system of wind turbine blade. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 241, 111385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chi, H.; Guo, W.; Feng, F. An Experimental Study on the Surface De-Icing of FRP Plates via the External Hot-Air Method. Coatings 2025, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Dong, J.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Y. Experimental investigation of deicing characteristics using hot air as heat source. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 107, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalili, N.; Edrisy, A.; Carriveau, R. A review of surface engineering issues critical to wind turbine performance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Feng, F.; Li, Y. Study on the de-icing performance of wind turbine blades based on PCMS-C14 coating combined with electrothermal heating. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2026, 172, 111639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, L. 14-Optimising wind turbine design for operation in cold climates. In Wind Energy Systems; Sørensen, J.D., Sørensen, J.N., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 388–460. [Google Scholar]

- Ryerson, C.C. Ice protection of offshore platforms. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 65, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Yu, Z.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of Deicing Performance for the Pneumatic Impulse Deicing Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lei, Y. An effect assessment and prediction method of ultrasonic de-icing for composite wind turbine blades. Renew. Energy 2018, 118, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Palacios, J.; Rose, J.; Smith, E. De-icing of Multi-Layer Composite Plates Using Ultrasonic Guided Waves. In Proceedings of the 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, 16th AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference, 10th AIAA Non-Deterministic Approaches Conference, 9th AIAA Gossamer Spacecraft Forum, 4th AIAA Multidisciplinary Design Optimization Specialists Conference, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Schaumburg, IL, USA, 7–10 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Su, F.; Wang, Y. A light lithium niobate transducer for the ultrasonic de-icing of wind turbine blades. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H. Numerical simulation and experimental validation of ultrasonic de-icing system for wind turbine blade. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 114, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Song, B. Research on experiment and numerical simulation of ultrasonic de-icing for wind turbine blades. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, H.; Edwards, G.; Sannassy, C.; Kappatos, V.; Lage, Y.; Stein, J.; Selcuk, C.; Gan, T.-H. Modelling and empirical development of an anti/de-icing approach for wind turbine blades through superposition of different types of vibration. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2016, 128, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, H.; Guo, W. Simulation and Experimental Study on the Ultrasonic Micro-Vibration De-Icing Method for Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2021, 14, 8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, H.; Cheng, L.; Zheng, H.; Kappatos, V.; Selcuk, C.; Gan, T.-H. A dual de-icing system for wind turbine blades combining high-power ultrasonic guided waves and low-frequency forced vibrations. Renew. Energy 2015, 83, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Moreira, M.; Páscoa, J. Characterization of Plasma-Induced Flow Thermal Effects for Wind Turbine Icing Mitigation. Energies 2024, 17, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xue, Z.; Jiang, D.; Chen, Z.; Si, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Study on Durability and Dynamic Deicing Performance of Elastomeric Coatings on Wind Turbine Blades. Coatings 2024, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.; Timco, G.; Gravesen, H.; Vølund, P. Ice loading on Danish wind turbines. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2005, 41, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Tan, X.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T. Numerical study of ice-induced loads and responses of a monopile-type offshore wind turbine in parked and operating conditions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2016, 123, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Yang, D. Ice loads and ice-induced vibrations of offshore wind turbine based on coupled DEM-FEM simulations. Ocean Eng. 2022, 243, 110197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 19906:2019; Petroleum and Natural Gas Industries—Arctic Offshore Structures. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Liu, Y.; Shi, W.; Lian, J.; Li, X.; Yao, Y.; Michailides, C.; Zhou, L.; Lu, P. A model test method of monopile-type offshore wind turbines subjected to floating ice. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 211, 113095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravesen, H.; Sørensen, S.L.; Vølund, P.; Barker, A.; Timco, G. Ice loading on Danish wind turbines: Part 2. Analyses of dynamic model test results. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2005, 41, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, L.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Research on the ice-resistance performance of conical wind turbine foundation in brash ice fields. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chuang, Z.; Qu, Y.; Yin, H.; Yang, Z.; Xia, L. Integrated analysis of ice-induced vibration characteristics of monopile offshore wind turbines. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2025, 17, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeishi, A.; Wang, C. Parameterizing Raindrop Formation Using Machine Learning. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2024, 152, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Deshmukh, A.; Waman, D.; Patade, S.; Jadav, A.; Phillips, V.T.J.; Bansemer, A.; Martins, J.A.; Gonçalves, F.L.T. The microphysics of the warm-rain and ice crystal processes of precipitation in simulated continental convective storms. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.; van Lier-Walqui, M.; Fridlind, A.M.; Grabowski, W.W.; Harrington, J.Y.; Hoose, C.; Korolev, A.; Kumjian, M.R.; Milbrandt, J.A.; Pawlowska, H.; et al. Confronting the Challenge of Modeling Cloud and Precipitation Microphysics. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2020, 12, e2019MS001689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khain, A.P.; Beheng, K.D.; Heymsfield, A.; Korolev, A.; Krichak, S.O.; Levin, Z.; Pinsky, M.; Phillips, V.; Prabhakaran, T.; Teller, A.; et al. Representation of microphysical processes in cloud-resolving models: Spectral (bin) microphysics versus bulk parameterization. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 247–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakar, K.K.; Morrison, H.; Grabowski, W.W.; Lawson, R.P. Are turbulence effects on droplet collision-coalescence a key to understanding observed rain formation in clouds? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319664121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.A.W.A.; Algaddaime, T.F.; Stack, M.M. Advancements and Challenges in Coatings for Wind Turbine Blade Raindrop Erosion: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms, Materials and Testing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfknecht, N.; von Terzi, D. Aerodynamic interaction of rain and wind turbine blades: The significance of droplet slowdown and deformation for leading-edge erosion. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 2333–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, N. Liquid droplet impingement erosion on multiple grooves. Wear 2020, 462–463, 203513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoksbergen, T.H.; Akkerman, R.; Baran, I. Rain droplet impact stress analysis for leading edge protection coating systems for wind turbine blades. Renew. Energy 2023, 218, 119328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, D.; Yang, M. Effects of surface curvature on rain erosion of wind turbine blades under high-velocity impact. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, N.; Yamagata, T.; Wada, K. Attenuation of wall-thinning rate in deep erosion by liquid droplet impingement. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2016, 88, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.E.; Dear, J.P.; Ogren, J.E. The effects of target compliance on liquid drop impact. J. Appl. Phys. 1989, 65, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, N.; Yamagata, T.; Saito, K.; Hayashi, K. The effect of liquid film on liquid droplet impingement erosion. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2013, 265, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Sun, H.; Zheng, X. A numerical study on dynamic characteristics of 5 MW floating wind turbine under wind-rain conditions. Ocean Eng. 2022, 262, 112095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Carroll, A.; Hardiman, M.; Tobin, E.F.; Young, T.M. Correlation of the rain erosion performance of polymers to mechanical and surface properties measured using nanoindentation. Wear 2018, 412–413, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, F. Erosion by liquids. Mach. Des. 1970, 10, 118–124. Available online: https://users.encs.concordia.ca/~tmg/images/8/8b/Erosion_by_liquids.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- ASTM G73-10; A. Standard Test Method for Liquid Impingement Erosion Using Rotating Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- Sareen, A.; Sapre, C.A.; Selig, M.S. Effects of leading edge erosion on wind turbine blade performance. Wind Energy 2014, 17, 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Tempelis, A.; Kuthe, N.; Mahajan, P. Recent developments in the protection of wind turbine blades against leading edge erosion: Materials solutions and predictive modelling. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, J.A.; Barthelmie, R.J.; Pryor, S.C. Automated Quantification of Wind Turbine Blade Leading Edge Erosion from Field Images. Energies 2023, 16, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castorrini, A.; Corsini, A.; Rispoli, F.; Venturini, P.; Takizawa, K.; Tezduyar, T.E. Computational analysis of wind-turbine blade rain erosion. Comput. Fluids 2016, 141, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, O.; Khan, A.; Sharma, S.; Collins, K.; Gianni, M. Leading Edge Erosion Classification in Offshore Wind Turbines Using Feature Extraction and Classical Machine Learning. Energies 2024, 17, 5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.S.; Noi, S.D.; Ren, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Teuwen, J.J.E. Minimum Leading Edge Protection Application Length to Combat Rain-Induced Erosion of Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2021, 14, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Hasager, C.B.; Bak, C.; Tilg, A.-M.; Bech, J.I.; Doagou Rad, S.; Fæster, S. Leading edge erosion of wind turbine blades: Understanding, prevention and protection. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.C.; Kolios, A.; Wang, L.; Chiachio, M. A wind turbine blade leading edge rain erosion computational framework. Renew. Energy 2023, 203, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsbergen, D.V.; Verma, A.; Nejad, A.; Helsen, J. Modeling of rain-induced erosion of wind turbine blades within an offshore wind cluster. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2875, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, H.; Hoff, G.; Langbein, G.; Taylor, G.; Jenkins, D.C.; Taunton, M.A.; Fyall, A.A.; Jones, R.F.; Harper, T.W. Rain Erosion Properties of Materials [and Discussion]. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1966, 260, 168–181. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/73548 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Wang, J.; Yin, M.; Yu, C.; Tu, S.; Feng, J. Highly elastic and stable hydrophobic coatings with excellent rain erosion resistance for wind turbine blades. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 200, 109013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadeh, B.; Louhghalam, A.; Raessi, M.; Tootkaboni, M. A computational framework for the analysis of rain-induced erosion in wind turbine blades, part I: Stochastic rain texture model and drop impact simulations. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 163, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, R.; Dyer, K.; Martin, F.; Ward, C. The increasing importance of leading edge erosion and a review of existing protection solutions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 109382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, M.H.; Nash, D.H.; Stack, M.M. On erosion issues associated with the leading edge of wind turbine blades. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 383001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, G.; Singh, G. Comparative erosion wear analysis of polyurethane-coated and uncoated GFRP wind turbine blades under onshore conditions. Part. Sci. Technol. 2025, 43, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoksbergen, T.H.; Akkerman, R.; Baran, I. Liquid droplet impact pressure on (elastic) solids for prediction of rain erosion loads on wind turbine blades. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 233, 105319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arastoopour, H.; Cohan, A. CFD simulation of the effect of rain on the performance of horizontal wind turbines. AIChE J. 2017, 63, 5375–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Nie, S.; Yang, Y. Effects of rain on vertical axis wind turbine performance. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 170, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohan, A.C.; Arastoopour, H. Numerical simulation and analysis of the effect of rain and surface property on wind-turbine airfoil performance. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2016, 81, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhupanska, O.I. Challenges and Future Recommendations for Lightning Strike Damage Assessments of Composites: Laboratory Testing and Predictive Modeling. Materials 2024, 17, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Q.M.; Sánchez, F.; Mishnaevsky, L.; Young, T.M. Evaluation of offshore wind turbine blades coating thickness effect on leading edge protection system subject to rain erosion. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliyan, T.; Al-Gahtani, S.F.; Elbarbary, Z.M.S.; Wadie, F. Characterization of lightning-induced overvoltages in wind farms. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Hu, T.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D.; Song, C.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y. Research on wind turbine icing prediction data processing and accuracy of machine learning algorithm. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Hong, J. Wind turbine performance in natural icing environments: A field characterization. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 181, 103193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.; McDonald, A.; McMillan, D. Failure rate, repair time and unscheduled O&M cost analysis of offshore wind turbines. Wind Energy 2015, 19, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, F.; McAuliffe, F.D.; Sperstad, I.B.; Chester, R.; Flannery, B.; Lynch, K.; Murphy, J. A lifecycle financial analysis model for offshore wind farms. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolinger, M.; Wiser, R.; O’Shaughnessy, E. Levelized cost-based learning analysis of utility-scale wind and solar in the United States. iScience 2022, 25, 104378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldersey-Williams, J.; Rubert, T. Levelised cost of energy–A theoretical justification and critical assessment. Energy Policy 2019, 124, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilajuana Llorente, S.; Rapha, J.I.; Domínguez-García, J.L. Development and Analysis of a Global Floating Wind Levelised Cost of Energy Map. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 1142–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Costoya, X.; deCastro, M.; Iglesias, G.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Levelized cost of energy for various floating offshore wind farm designs in the areas covered by the Spanish maritime spatial planning. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hazard Type | Lightning | Icing | Rain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Terms Across Hazards | wind turbines, wind turbine blades, turbine components, wind power, wind energy, aerodynamics, computational fluid dynamics | ||

| Dominant/Distinct Keywords | lightning protection, grounding systems, surge protection, lightning currents, transient analysis, electrical discharge | ice accretion, anti-icing, de-icing, hydrophobicity, snow and ice removal, temperature, ice detection, glaze ice, rime ice | rain erosion, droplet impact, water film, coatings, erosion mechanisms, leading-edge erosion |

| Category | Author | Method | Research Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

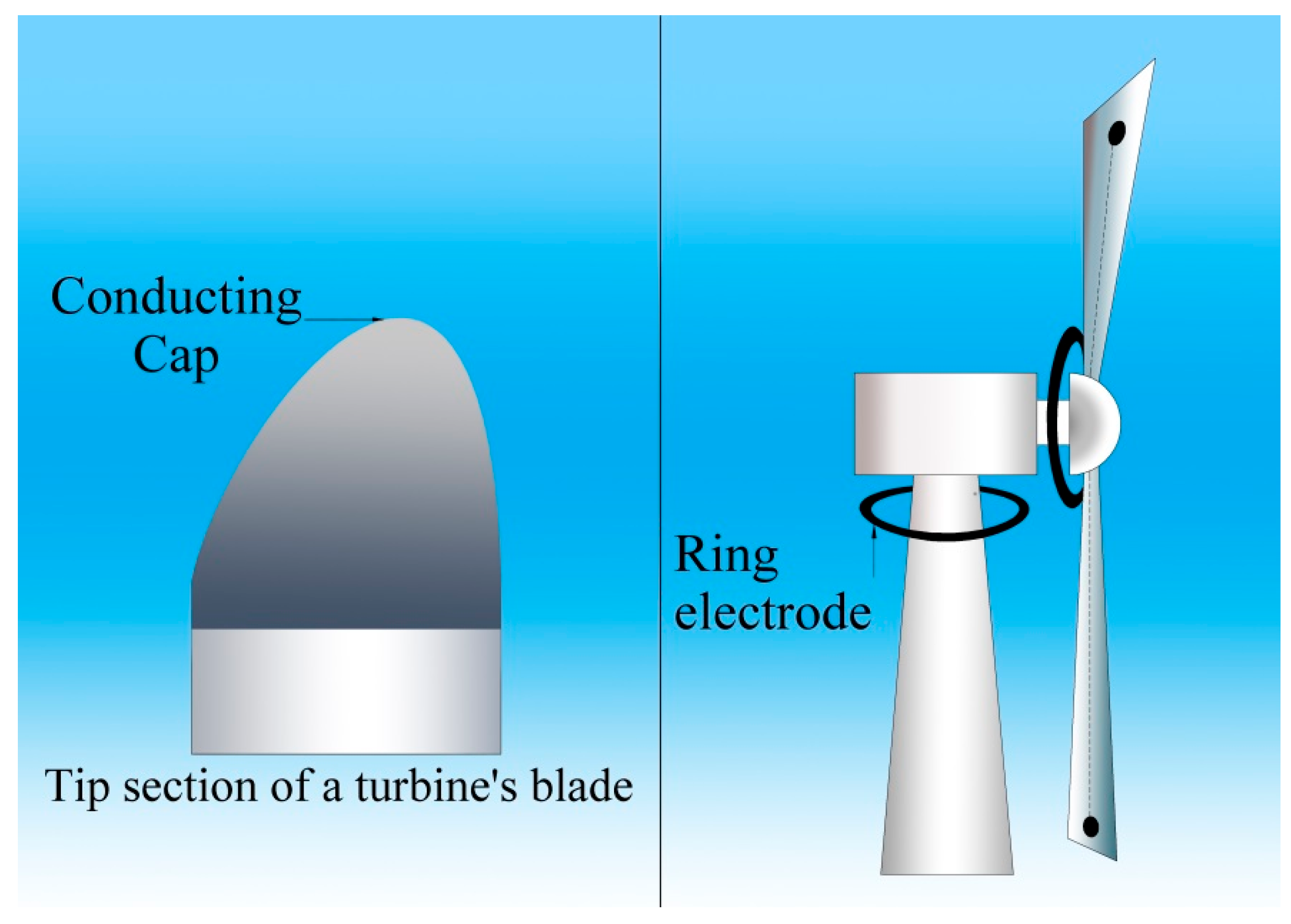

| Blade Interception Systems | IEC 61400-24 [73] | Standard blade receptor + down conductor | Standard guideline | Provides a defined low-impedance path for lightning current | Interception not 100%; only reliable for the blades ≤ 15–20 m [32] |

| Yokoyama [44] | Conducting a cap at the blade tip | Experiment | Higher interception efficiency than a point receptor | Reduced effectiveness under positive lightning | |

| Yoh [31] | Detached perpendicular dual-ring electrode behind the hub | Experiment | Prevents dielectric breakdown of low-voltage control circuits | Installation method & aerodynamic impact still unresolved | |

| Cotton et al. [32] | Tungsten-copper alloy receptor material | Experiment | Resists melting/erosion under high-current impulses | Susceptible to molten material ejection due to rotation | |

| Woo et al. [64] | Additional edge receptors to counter polarity-dependent interception | Experiment | Improves interception for positive impulses | Increased system complexity | |

| Zhou et al. [49] | Optimised receptor cross-section (~50 mm2); effect of multiple receptors | Numerical analysis | Optimal cross-section improves interception; consistency with IEC recommendations | Adding more receptors spreads the electric field and reduces interception efficiency | |

| Xie et al. [65] | Tip, side, and metal-mesh receptor configurations | Experiment | Metal mesh offers the best protection; modifies the electric field and suppresses partial discharges | Mesh adds weight and manufacturing complexity | |

| External Attractions | - | Lightning rod on a wave or platform structure | Conventional | Intercepts some discharges away from turbine | Limited protection radius |

| Yokoyama [44] | Nearby isolated lightning-attraction tower | Conceptual | Can divert lightning away from turbines | Requires constant wind direction; multiple towers may be needed | |

| Grounding and Earthing | Alipio et al. [66] | Bare or insulated interconnecting grounding conductor | Numerical analysis | Bare conductors reduce GPR via interconnection; insulated conductors divert some current to the adjacent tower in high-resistivity soils | Effectiveness depends strongly on soil resistivity |

| Razi-Kazemi et al. [67] | Linear, circular, delta, and four-way grounding for wind farms | Modelling and Simulation | Four-way provides largest overvoltage reduction; delta best cost-performance | Four-way requires higher installation cost | |

| Surge Protection | Malcolm & Aggarwal [11] | Metal oxide varistor (MOV) surge arresters | Modelling and Simulation | Absorb the excessive electrical energy and limit the transient overvoltage across its terminal | None listed |

| Yang et al. [53] | (i) Ground both ends of the signal cable (ii) Use a coaxial cable with double shielding layers | Numerical analysis | (i) Reduce the overvoltage on the cable caused by lightning current (ii) Causes lower overvoltage than a single-layered coaxial cable | Higher cost | |

| Heidary et al. [69] | Air-core reactor + suppressor resistor | Numerical analysis | Mitigates terminal and internal resonance overvoltages | Additional hardware and complexity | |

| Sarajčev et al. [55] | Install surge arresters on LV transformer side | Numerical analysis | Protects transformer windings from induced transients | Requires additional protective devices | |

| EMC Measures | Djalel et al. [29] | Design the nacelle as a closed metal shield | Conceptual | Attenuate the induced electromagnetic field inside the box | No experimental evidence for the effectiveness of this measure |

| Worms et al. [70] | Improved electrical bonding using M4 steel screws | Simulation | Reduces current slew rate to ~70 A/μs | Long-term corrosion/maintenance concerns | |

| Jiang et al. [52] | Optimised spacing between tower shell and cable shielding | Numerical analysis | Reduces internal flashover risk | May require structural redesign | |

| Material-based Protection | Mat Daud et al. [71] | Flax-fibre biocomposite blade | Experiment | Suffer less damage on the blade surface as compared to the glass fibre prototype | Absence of material strength |

| Zhao et al. [72] | Aluminium-plastic composite nacelle cover | Experiment | Better damage resistance than 5052 Al & Q235B steel | Central ablation pit still occurs |

| Category | Passive Methods | Active Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Principle | Modify surface chemistry/microstructure to reduce adhesion, delay ice nucleation [13,157,158] | Apply external energy (thermal, mechanical, however, this pattern may not apply to studies combining electric heating and magnetic) to melt, weaken or shed ice [163,172,173,174,180] |

| Power consumption | Essentially zero as no external energy input [80] | Moderate to high, depending on the method; electric heating highest, and ultrasonic is relatively low [161,162,172] |

| Effectiveness | Effective for light icing only; unreliable under severe glaze conditions [150,158] | Effective for moderate–severe icing; capable of complete removal (heating, mechanical, ultrasonic) [161,174] |

| Durability/lifespan | Often limited by erosion, UV exposure and abrasion, superhydrophobic coatings degrade rapidly under real weathering [159] | Long-term components, but subject to fatigue, erosion, lightning, and wiring degradation |

| Complexity and Maintenance | Low system complexity but requires periodic recoating or surface renewal [181] | Higher complexity; requires integrated control electronics, power supply and more frequent component monitoring [162,179] |

| Cost | Low initial cost but frequent reapplication increases long-term operations and maintenance cost [160] | High initial cost and energy consumption; operating cost depends strongly on icing climate [161,163] |

| Environmental/operational constraints | Performance deteriorates with contamination, ageing, and erosion [159] | Some systems are limited by low ambient temperatures or access difficulties; high-energy penalty [162] |

| Advantages | Cheap, simple, no power draw, can reduce ice adhesion significantly | Reliable removal, controllable, widely field-tested, functional across icing severity [14] |

| Limitations | Cannot remove moderate/severe ice, degrades fast, poor real-world reliability | High energy use, heavy components, design integration required, expensive offshore servicing [12,80] |

| Applications | Used mainly as anti-icing (delay), not full de-icing. Common in onshore turbines with light icing climates. | Standard for modern cold-climate turbines; heating and mechanical systems are widely commercialised [80] |

| Examples | Hydrophobic/superhydrophobic coatings, icephobic polymer layers, textured surfaces | Electric resistance heating, hot-air circulation, hybrid electrothermal + PCMS-C14 phase-change microcapsule coating, microwave heating, ultrasonic vibration, pneumatic boots |

| Criteria/Scope | Lightning | Icing | Rain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary materials mentioned |

| ||

| Functional requirements |

| ||

| Damage mechanisms |

| ||

| Current limitations |

|

| |

| Key performance metrics |

|

| |

| Representative solutions |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.-H.; Khor, C.-S.; Wong, K.-H.; Ng, J.-H.; Mat, S.; Chong, W.-T. A Review of Meteorological Hazards on Wind Turbines Performance: Part 1 Lightning, Icing, and Rain. Energies 2025, 18, 6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246558

Wang X-H, Khor C-S, Wong K-H, Ng J-H, Mat S, Chong W-T. A Review of Meteorological Hazards on Wind Turbines Performance: Part 1 Lightning, Icing, and Rain. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246558

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiao-Hang, Chong-Shen Khor, Kok-Hoe Wong, Jing-Hong Ng, Shabudin Mat, and Wen-Tong Chong. 2025. "A Review of Meteorological Hazards on Wind Turbines Performance: Part 1 Lightning, Icing, and Rain" Energies 18, no. 24: 6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246558

APA StyleWang, X.-H., Khor, C.-S., Wong, K.-H., Ng, J.-H., Mat, S., & Chong, W.-T. (2025). A Review of Meteorological Hazards on Wind Turbines Performance: Part 1 Lightning, Icing, and Rain. Energies, 18(24), 6558. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246558