Water Shutoff with Polymer Gels in a High-Temperature Gas Reservoir in China: A Success Story

Abstract

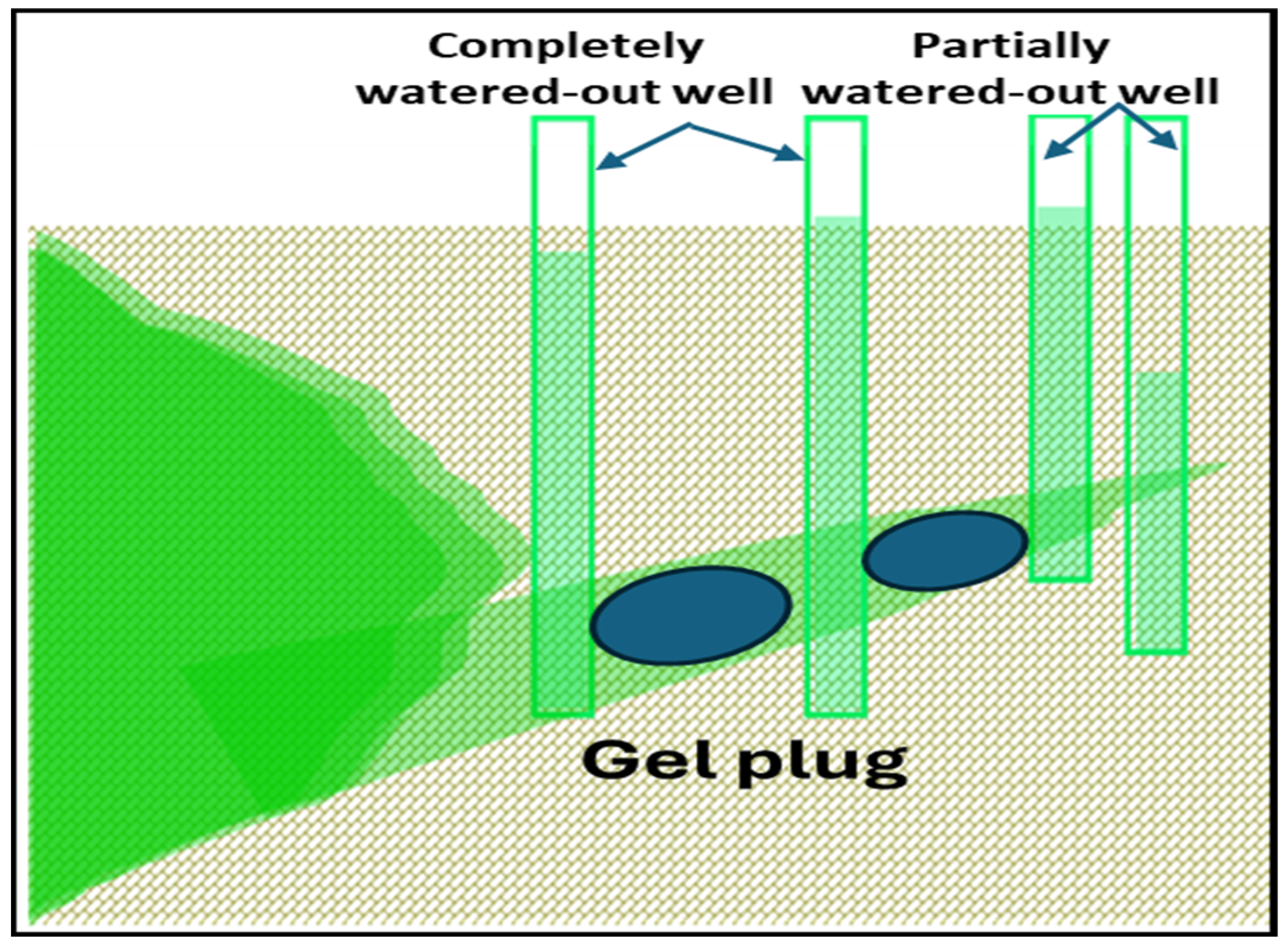

1. Introduction

1.1. Objective

1.2. Geological Setting

2. Wellbore Description

3. Lab Evaluation of the Polymer Gel System

3.1. Gel System Selection

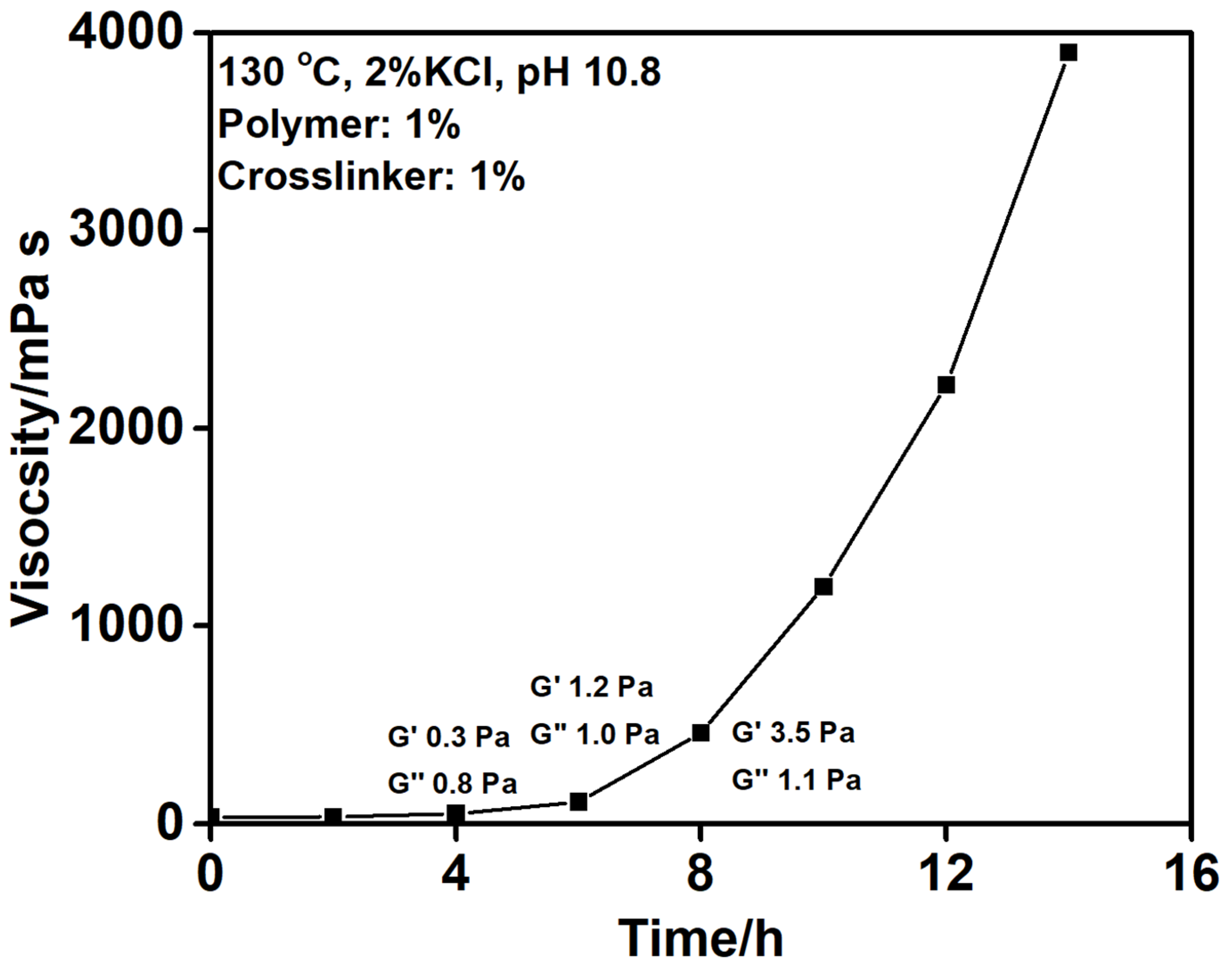

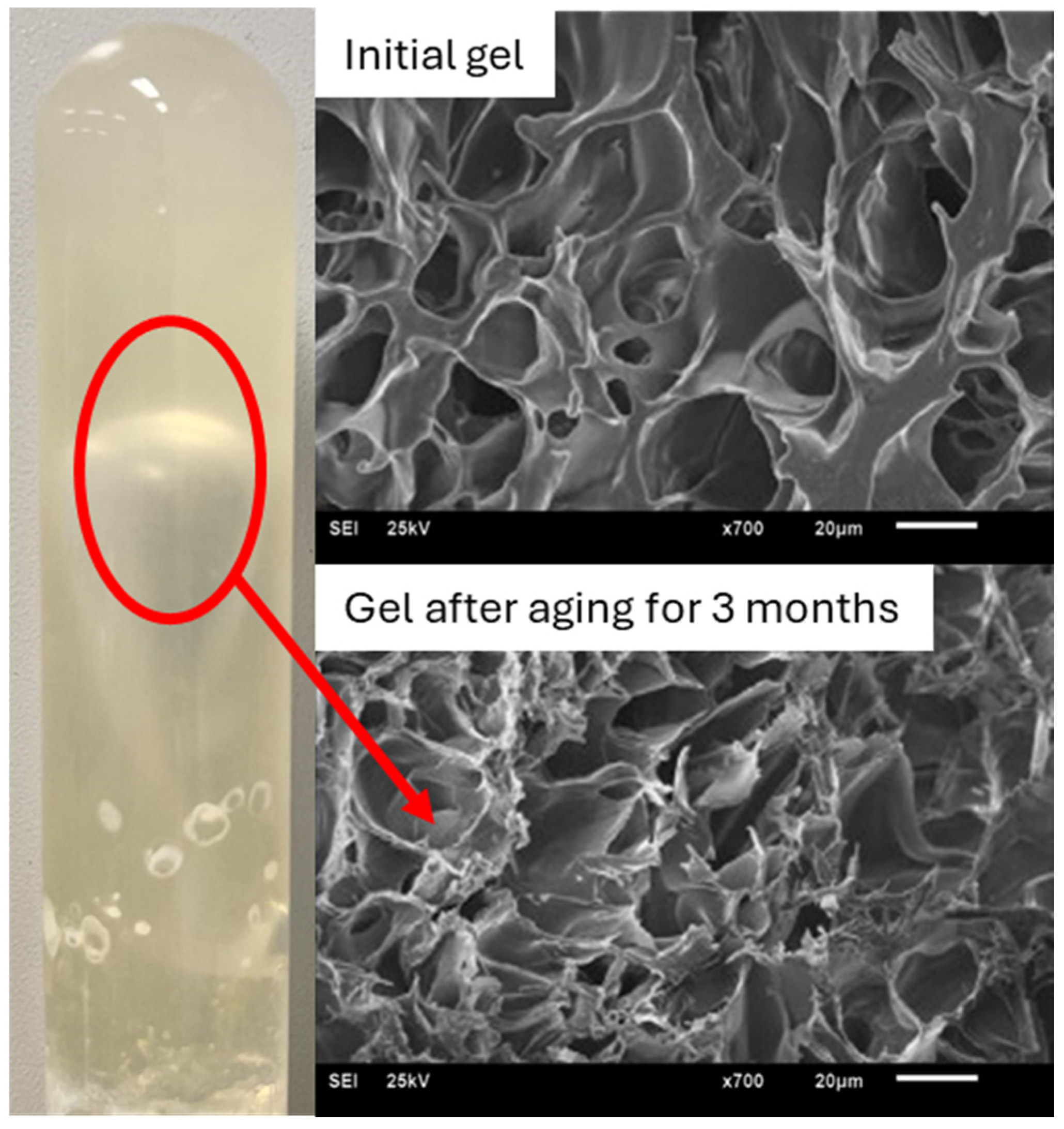

3.2. Gel System Evaluation

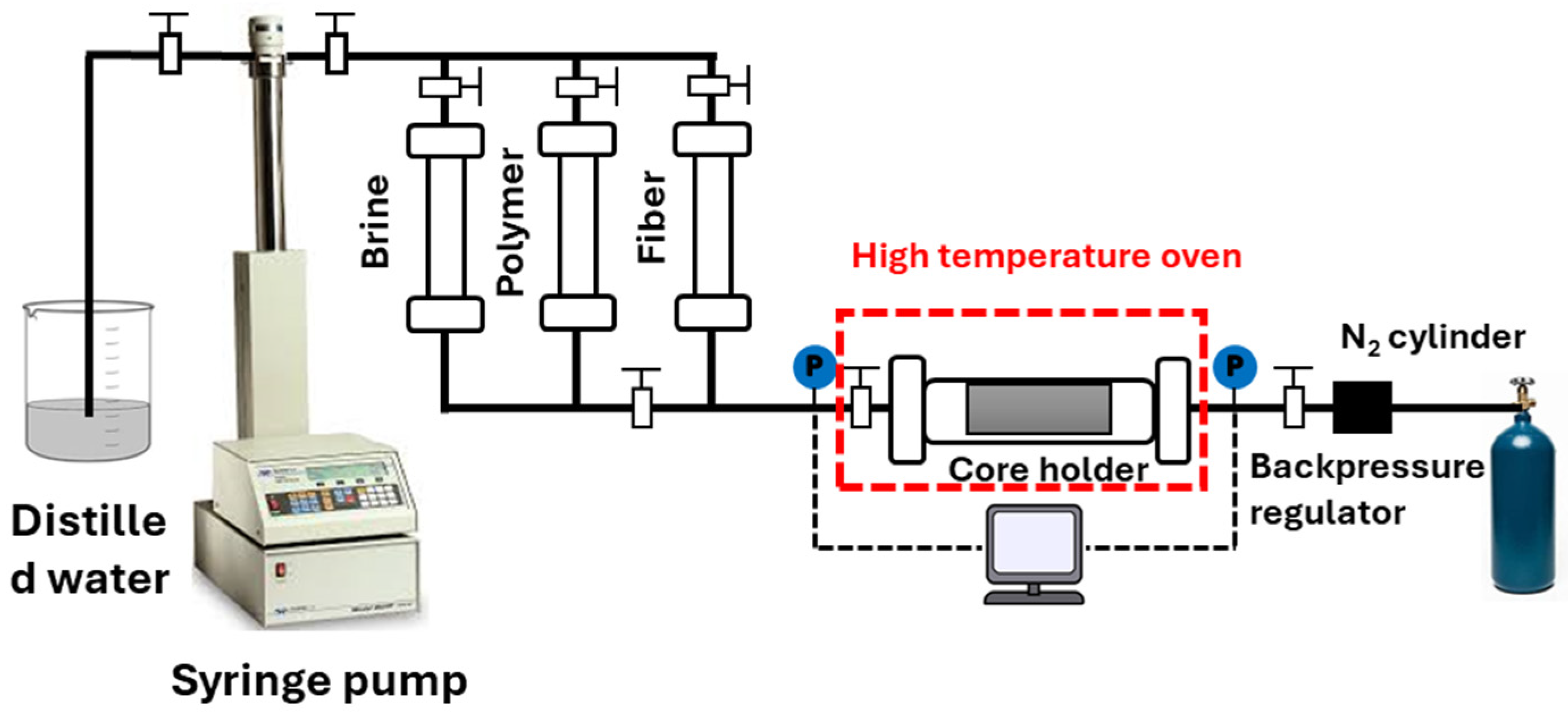

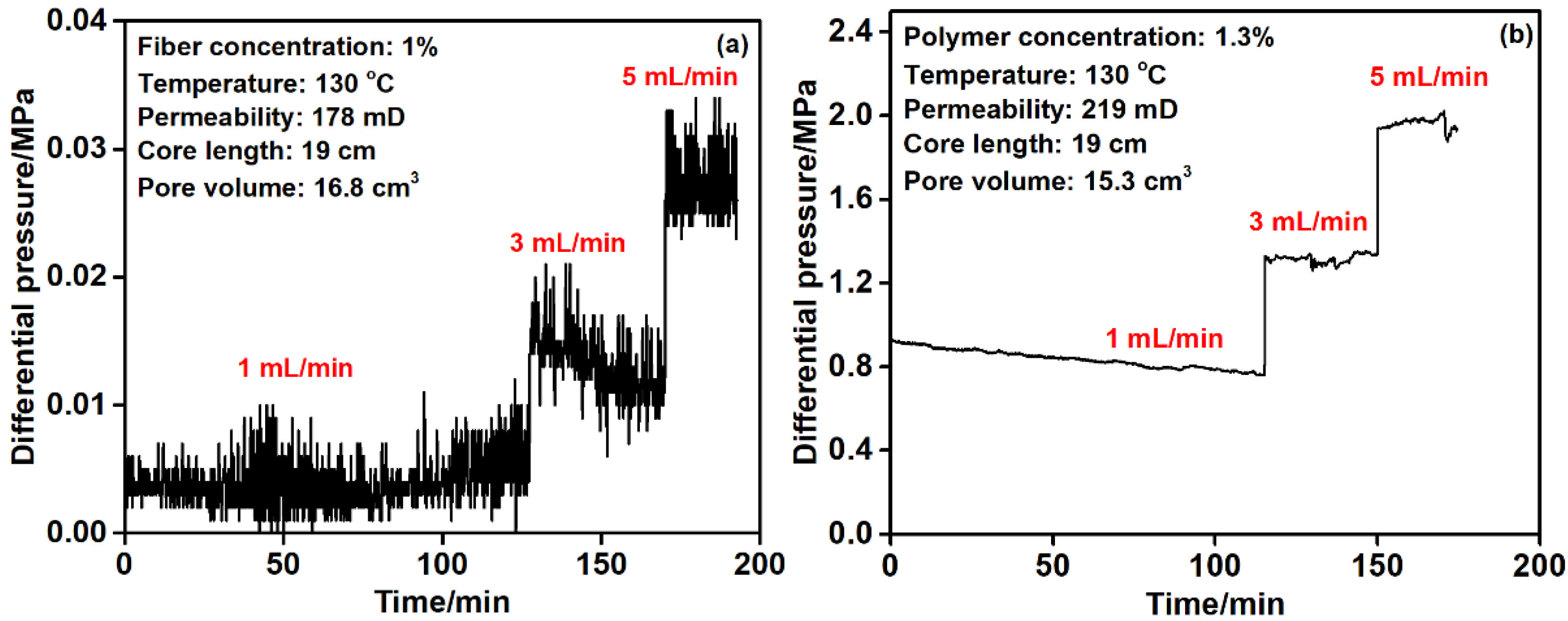

3.3. Core Flooding Test

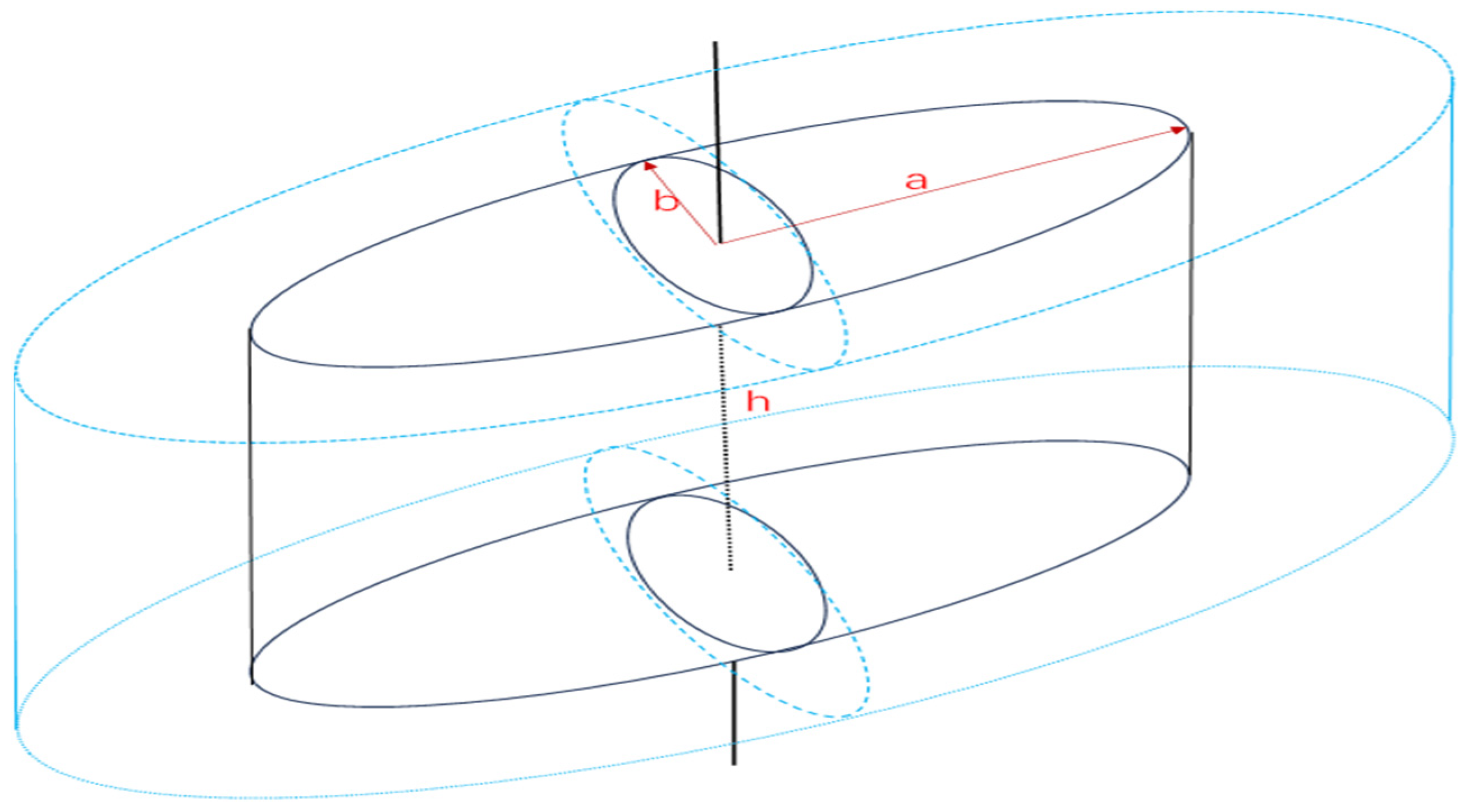

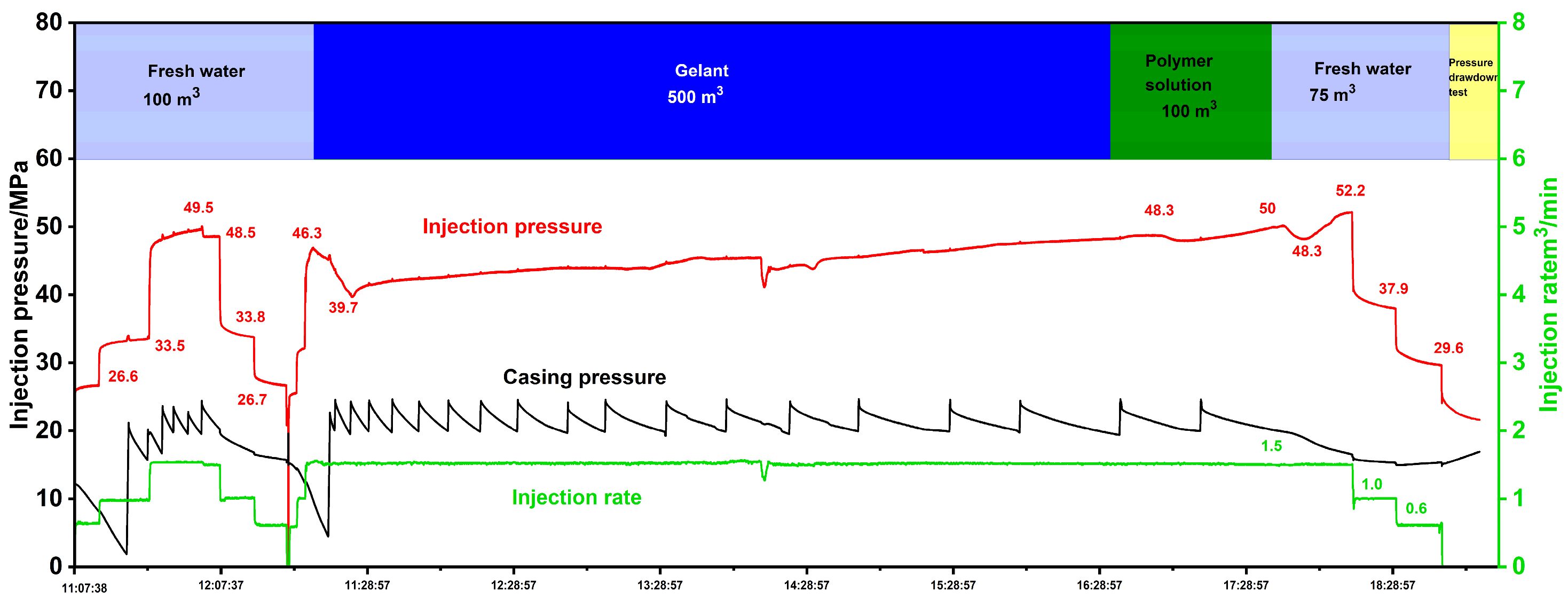

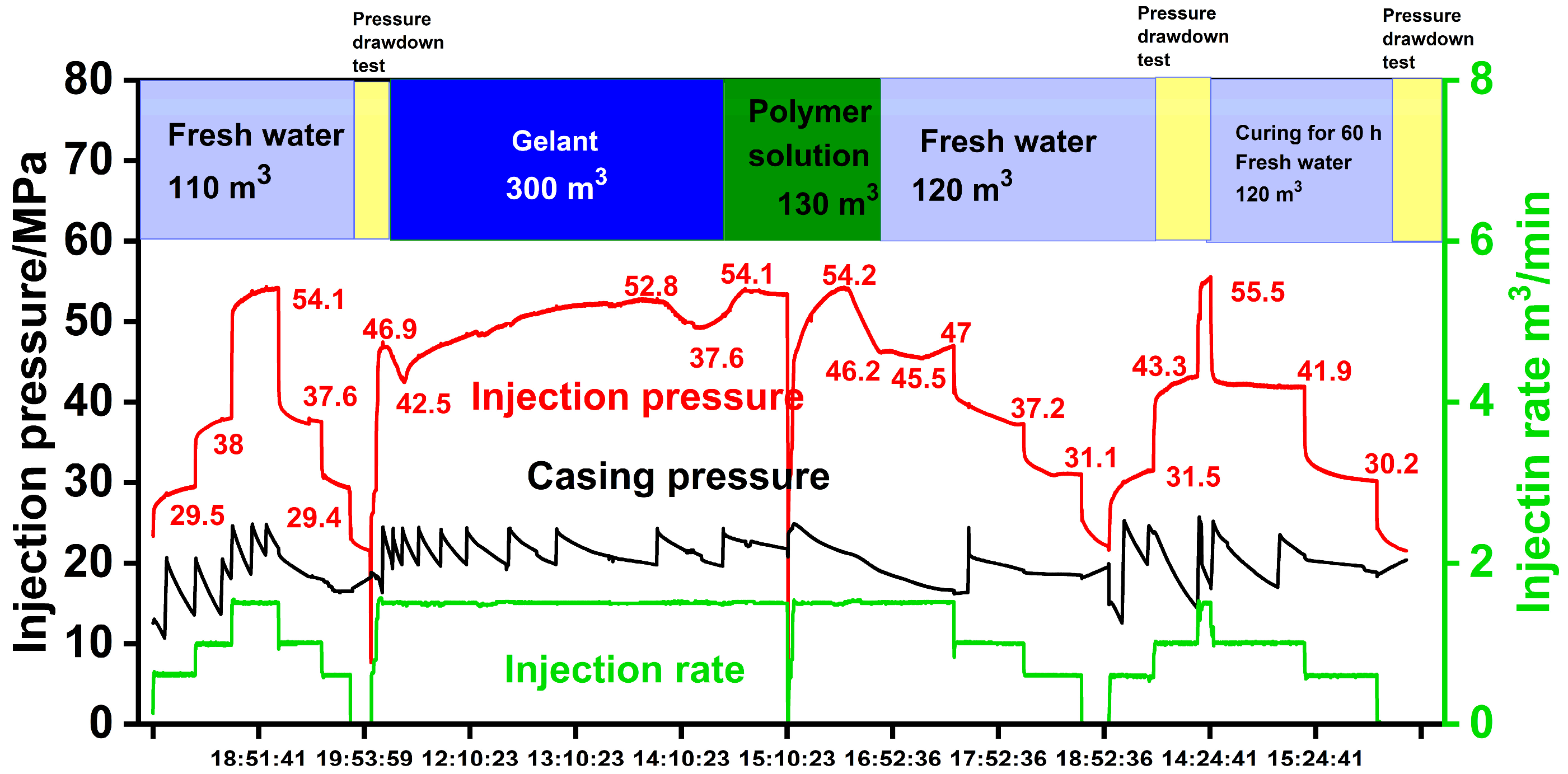

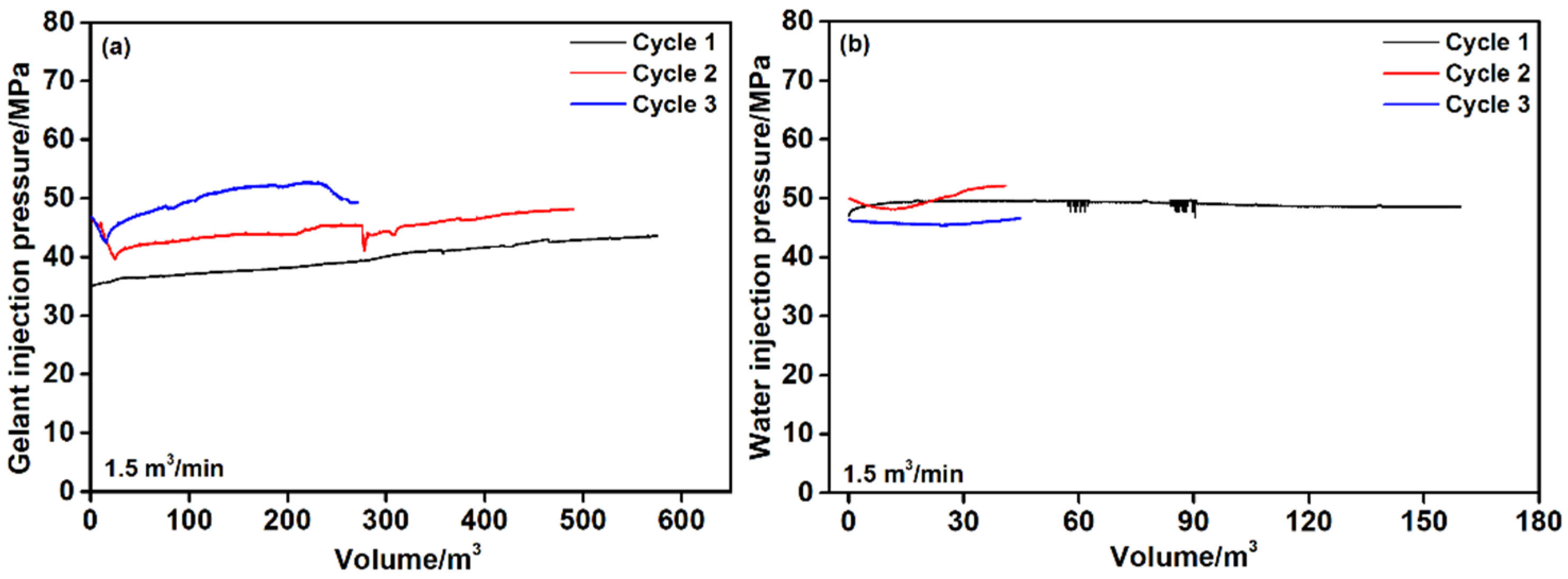

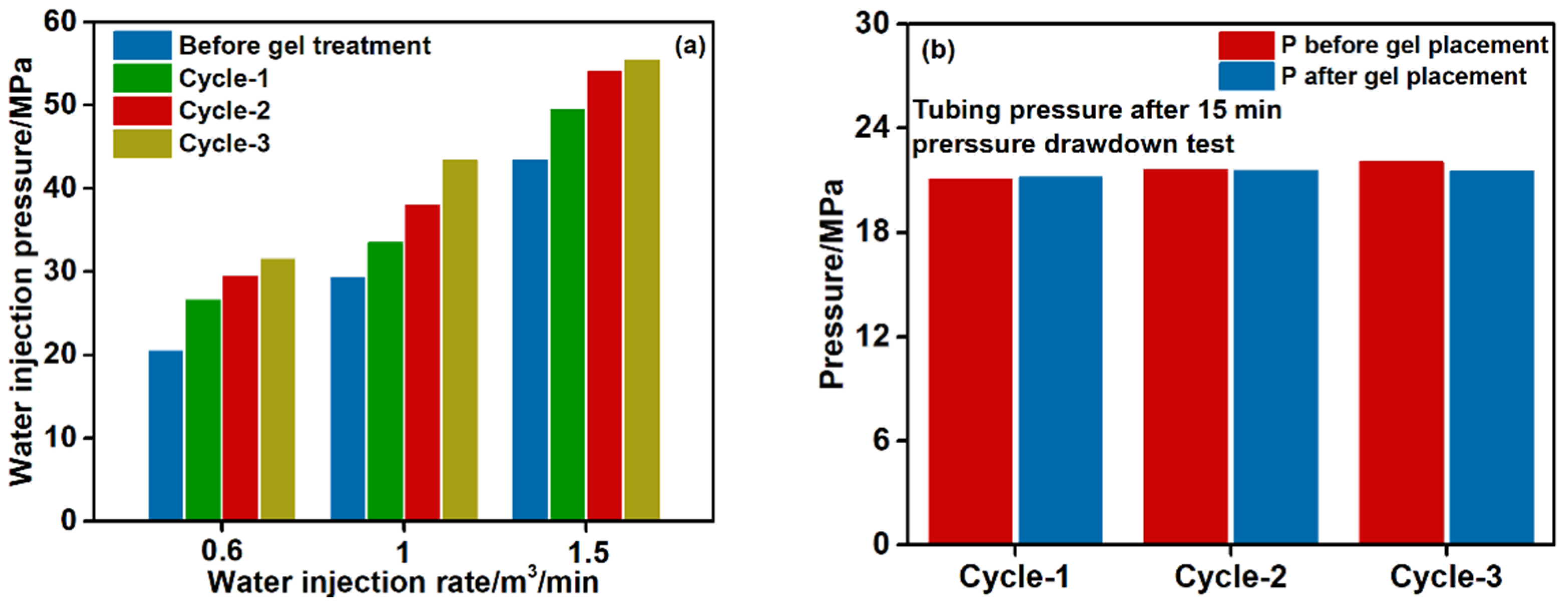

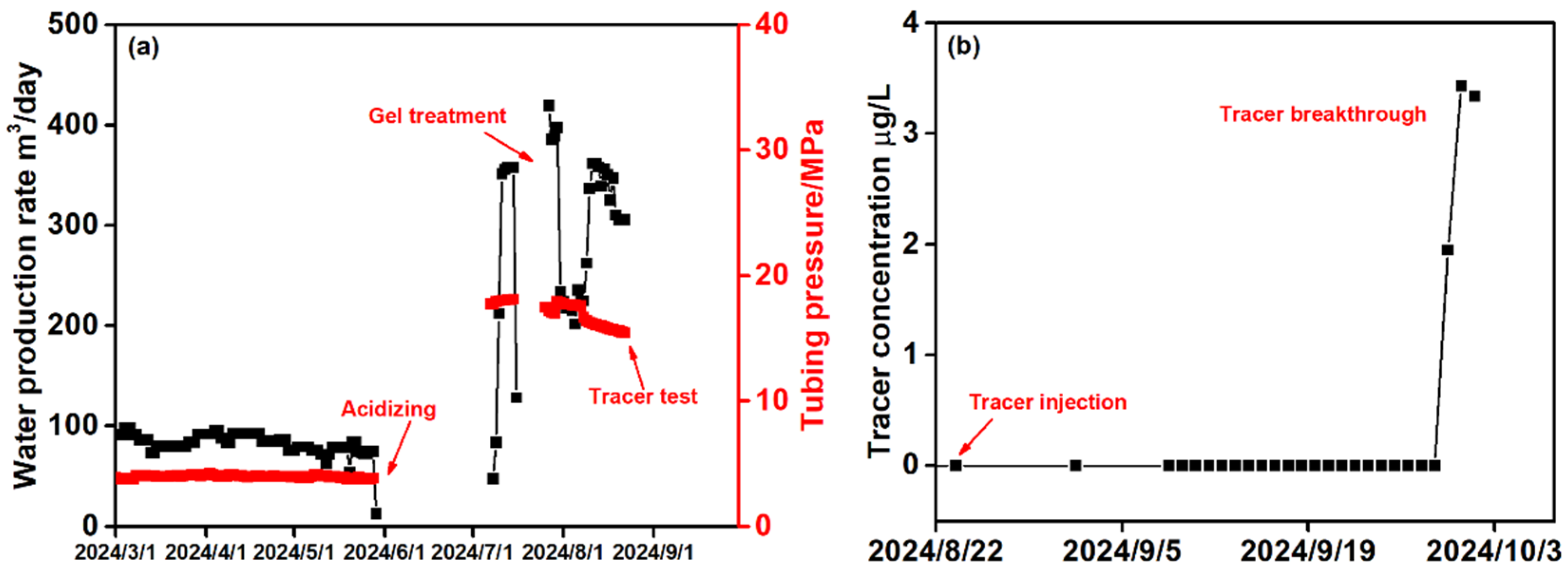

4. Treatment Design and Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roozshenas, A.A.; Hematpur, H.; Abdollahi, R.; Esfandyari, H. Water production problem in gas reservoirs: Concepts, challenges, and practical solutions. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9075560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugan, M.F. Deliquification techniques for conventional and unconventional gas wells: Review, field cases and lessons learned for mitigation of liquid loading. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 83, 103568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A. Chemical water & gas shutoff technology-an overview. In Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–9 October 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf, N.; Olayiwola, O.; Guo, B.; Liu, N. A comprehensive review on the loss of wellbore integrity due to cement failure and available remedial methods. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 109123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizak, K.F.; Zeltmann, T.A.; Crook, R.J. Permian basin operators seal casing leaks with small-particle cement. In Proceedings of the Permian Basin Oil and Gas Recovery Conference, Midland, TX, USA, 18–20 March 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dovan, H.; Hutchins, R.; Sandiford, B. Delaying gelation of aqueous polymers at elevated temperatures using novel organic crosslinkers. In Proceedings of the SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry, Midland, TX, USA, 18–21 February 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dovan, H.T.; Hutchins, R.D. Development of a new aluminum/polymer gel system for permeability adjustment. SPE Reserv. Eng. 1987, 2, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Araghi, A.; Beardmore, D.; Stahl, G. The application of gels in enhanced oil recovery: Theory, polymers and crosslinker systems. In Water-Soluble Polymers for Petroleum Recovery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Huang, F.; Lu, X.; Sheng, W. Preparation and performance of high-temperature-resistant, degradable inorganic gel for steam applications. SPE J. 2024, 29, 4266–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Bai, B.; Hou, J. Polymer gel systems for water management in high-temperature petroleum reservoirs: A chemical review. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 13063–13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Schuman, T.; Smith, D.; Song, T. In Lessons Learned from Laboratory Study and Field Application of Re-Crosslinkable Preformed Particle Gels RPPG for Conformance Control in Mature Oilfields with Conduits/Fractures/Fracture-Like Channels. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 22–25 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. Molecules as models for bonding in silicates. Am. Mineral. 1982, 67, 421–450. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Li, B.; Li, Q.; Tian, J. Effect of polyaluminum chloride on the properties and hydration of slag-cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinfar, M.; Nychka, J.A. A review of sodium silicate solutions: Structure, gelation, and syneresis. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 322, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Skrettingland, K.; Stavland, A.; Altunina, L.; Reimann, S.; Dillen, M.; Robøle, B. Validation and benchmarking of an inorganic aluminium-carbamide gel system for in-depth and near wellbore conformance control. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 31 August–4 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fragachán, F.E.; Cázares-Robles, F.; Gutiérrez, J.J.; Herrera, G. Controlling Water Production in Naturally Fractured Reservoirs with Inorganic Gel. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Conference and Exhibition of Mexico, Villahermosa, Mexico, 5–7 March 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cheneviere, P.; Falxa, P.; Alfenore, J.; Poirault, D.; Enkababian, P.; Chan, K.S. Chemical Water Shutoff Interventions in the Tunu Gas Field: Optimisation of the Treatment Fluids, Well Interventions, and Operational Challenges. In Proceedings of the SPE European Formation Damage Conference and Exhibition, Sheveningen, The Netherlands, 25–27 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chaabouni, H.; Enkababian, P.; Chan, K.S.; Cheneviere, P.; Falxa, P.; Urbanczyk, C.; Odeh, N. Successful innovative water-shutoff operations in low-permeability gas wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and Conference, Cairo, Egypt, 22–24 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, B.; Zhou, J.; Yin, M. A comprehensive review of polyacrylamide polymer gels for conformance control. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligthelm, D.J. Water shutoff in gas wells: Is there scope for a chemical treatment? In Proceedings of the SPE European Formation Damage Conference, The Hague, Netherlands, 21–22 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dovan, H.T.; Hutchins, R.D. New polymer technology for water control in gas wells. SPE Prod. Facil. 1994, 9, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, R.; Dovan, H.; Sandiford, B. Field applications of high temperature organic gels for water control. In Proceedings of the SPE/DOE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, OK, USA, 21–24 April 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Junesompitsiri, C.; Berel, A.; Curtice, R.; Riyanto, L.; Thouvenin, E.; Cheneviere, P. Selective water shutoff in gas well turns a liability into an asset: A successful case history from east kalimantan, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference & Exhibition, Jakarta, Indonesia, 4–6 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muntasheri, G.A.; Sierra, L.; Garzon, F.; Lynn, J.D.; Izquierdo, G. Water shut-off with polymer gels in a high temperature horizontal gas well: A success story. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, OK, USA, 24–28 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mattey, P.; Varshney, M.; Daksh, P.V.; Kumar, A. A successful water shut off treatment in gas well of bassein field by polymeric gel system. In Proceedings of the SPE Oil and Gas India Conference and Exhibition, Mumbai, India, 4–6 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Xie, H.; Cai, Z. Geological characteristics of Dina-2 gas field in Kuqa depression. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2003, 14, 371–374. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, H.; Song, Y.; Liu, W.; Wei, C. Origin of abnormal high pressure and its relationship with hydrocarbon accumulation in the Dina 2 gas field, Kuqa depression. Pet. Res. 2016, 1, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Tian, X.; Bai, B.; Eriyagama, Y.; Ahdaya, M.; Alotibi, A.; Schuman, T. Laboratory evaluation of high-temperature resistant lysine-based polymer gel systems for leakage control. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 234, 212685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Zhai, Z.; Liu, J.; Eriyagama, Y.; Ahdaya, M.; Alotibi, A.; Wang, Z.; Schuman, T.; Bai, B. Laboratory evaluation of a novel Self-healable polymer gel for CO2 leakage remediation during CO2 storage and CO2 flooding. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 444, 136635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ge, J.; Zhao, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Tao, Z. Performance evaluation of high-strength polyethyleneimine gels and syneresis mechanism under high-temperature and high-salinity conditions. SPE J. 2022, 27, 3630–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Bai, B.; Eriyagama, Y.; Schuman, T. Lysine crosslinked polyacrylamide—A novel green polymer gel for preferential flow control. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 4419–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillet, A.M.; Wyatt, N.B.; Gloe, L.M. Polymer gel rheology and adhesion. Rheology 2012, 3, 59–80. [Google Scholar]

| # | Reservoir T/°C | Gel Type | Gelation Time/h | Gelant Volume | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 126–137 | Aluminum gel | <6 | 139 bbl | [17] |

| 2 | 58.8 | PAM/Cr (VI) | <8 | 634 bbl | [21] |

| 3 | 121 | PAM/hydroquinone + hexame-thylenetretramine | <6 | 620 bbl | [6] |

| 4 | 112 | PAM/PEI | - | 80 | [23] |

| 5 | 149 | PAM/PEI | 1.5 | 150 | [24] |

| 6 | 105 | PAM/hydroquinone + hexame-thylenetretramine | - | 160 | [25] |

| pH | Static Gelation Time/h (130 °C) | Gel Code After Fully Gelation |

|---|---|---|

| 8.1 | 2 | I |

| 9.5 | 4 | I |

| 10.3 | 5 | H |

| 10.8 | 6 | G |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, T.; Wu, H.; Liu, P.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Ding, B.; et al. Water Shutoff with Polymer Gels in a High-Temperature Gas Reservoir in China: A Success Story. Energies 2025, 18, 6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246554

Song T, Wu H, Liu P, Wu J, Wang C, Zhang H, Zhang S, Li M, Wang J, Ding B, et al. Water Shutoff with Polymer Gels in a High-Temperature Gas Reservoir in China: A Success Story. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246554

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Tao, Hongjun Wu, Pingde Liu, Junyi Wu, Chunlei Wang, Hualing Zhang, Song Zhang, Mantian Li, Junlei Wang, Bin Ding, and et al. 2025. "Water Shutoff with Polymer Gels in a High-Temperature Gas Reservoir in China: A Success Story" Energies 18, no. 24: 6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246554

APA StyleSong, T., Wu, H., Liu, P., Wu, J., Wang, C., Zhang, H., Zhang, S., Li, M., Wang, J., Ding, B., Liu, W., Peng, J., Zhu, Y., & Wei, F. (2025). Water Shutoff with Polymer Gels in a High-Temperature Gas Reservoir in China: A Success Story. Energies, 18(24), 6554. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246554