1. Introduction

With the proposal of “dual carbon” goals, the proportion of distributed energy resources (DERs) connected to the power grid continues to increase. Their inherent randomness and output fluctuations pose significant challenges to the security and stability of the power system. In this context, VPP technology addresses this problem by integrating these decentralized and independently operated DERs into an aggregated entity [

1,

2], enabling coordinated control over power generation, storage, and consumption [

3], thereby mitigating the impact of DERs’ uncertainties on the grid. Consequently, the optimal dispatch of VPPs has become a key focus of current research [

4,

5].

VPPs can be categorized into external-dispatch VPPs and internal-dispatch VPPs. External dispatch refers to the participation of the VPP in the centralized dispatch of the power grid as a single entity [

6,

7,

8]. Internal optimal dispatch involves the VPP coordinating and controlling its internal DERs according to schedules issued by the dispatch organization. Research on scheduling strategies for maximizing VPP revenue focuses primarily on internal optimal dispatch. Reference [

9] used a fully distributed dispatch method to achieve maximum economic benefit. Reference [

10] introduced a decentralized economic dispatch method and architecture for VPPs that are applicable to massive DERs. However, the computational load and model complexity of the distributed algorithms in these two references are high; when the types and quantity of resources aggregated by the VPP are excessive, the difficulty of solving the optimization model increases significantly. Reference [

11] established a two-stage optimal scheduling framework. This model leverages the inherent complementary characteristics of the wind and photovoltaic power outputs to effectively increase the operational revenue of the VPP. Nonetheless, the aforementioned studies consider only traditional single-energy (electrical) VPPs and lack the integration of cooling and heating complementarity, which, to some extent, limits the potential revenue of the VPP.

Multienergy virtual power plants (MEVPs) can aggregate additional forms of energy, such as electrical and thermal energy, enabling the complementary use of multiple types of energy resources and thereby achieving the efficient management and utilization of multiple energy sources. Reference [

12] established a VPP comprising wind turbines and combined heat and power (CHP) units and verified the effectiveness of the thermoelectric coupling mode in reducing system operational costs. Furthermore, for systems with a high penetration of renewable energy, studies have shown that configuring electric boilers [

13], thermal storage devices [

14], or a combination of both [

15] can increase system flexibility and reduce costs. The aforementioned studies demonstrate that extending VPPs to MEVPPs can improve the system’s economic efficiency; however, the dispatch mechanisms of MEVPPs need further investigation. In this regard, reference [

16] explored an electricity–gas coupled VPP and established a dual-objective optimization model that simultaneously pursues maximum operational profit and minimum risk. However, the primary focus of this study was recycling within the electricity–gas conversion process, leaving the electricity–thermal coupling aspect for further exploration. Reference [

17] employed scenario generation and reduction techniques to address the uncertainties of wind and photovoltaic power outputs and established a two-stage collaborative optimization model for a combined cooling, heating, and power (CCHP) VPP under multiple scenarios. However, this model did not fully account for the uncertainties in wind and PV power outputs when addressing the economic dispatch of the MEVPP, nor did it consider the role of demand-side resources. Reference [

18] considered multiple uncertainties on both the supply and demand sides and adopted a two-stage robust stochastic optimization method for dispatch decisions. Reference [

19] proposed a scenario optimization method that enables the MEVPP to perform coordinated dispatch in terms of both active and reactive power.

The studies mentioned above focused primarily on the economic aspect of MEVPP operation and overlooked the impact of carbon emissions on MEVPP operational strategies. To address this gap, reference [

20] established an optimal dispatch model for a CCHP VPP that considers carbon trading costs. However, this study simplified the resources aggregated by the MEVPP and failed to consider the impact of key DERs, such as energy storage and demand response, on the optimization results. References [

21,

22] introduced a carbon trading mechanism into the MEVPP and employed a robust optimization method to address multiple uncertainties. However, this method, which makes decisions on the basis of the worst-case scenario, may lead to overly conservative dispatch schemes. Reference [

23] designed an MEVPP architecture that incorporates thermal power units and a carbon capture system. This model performed well in synergistically reducing operational costs and carbon emissions, but its demand response model was oversimplified.

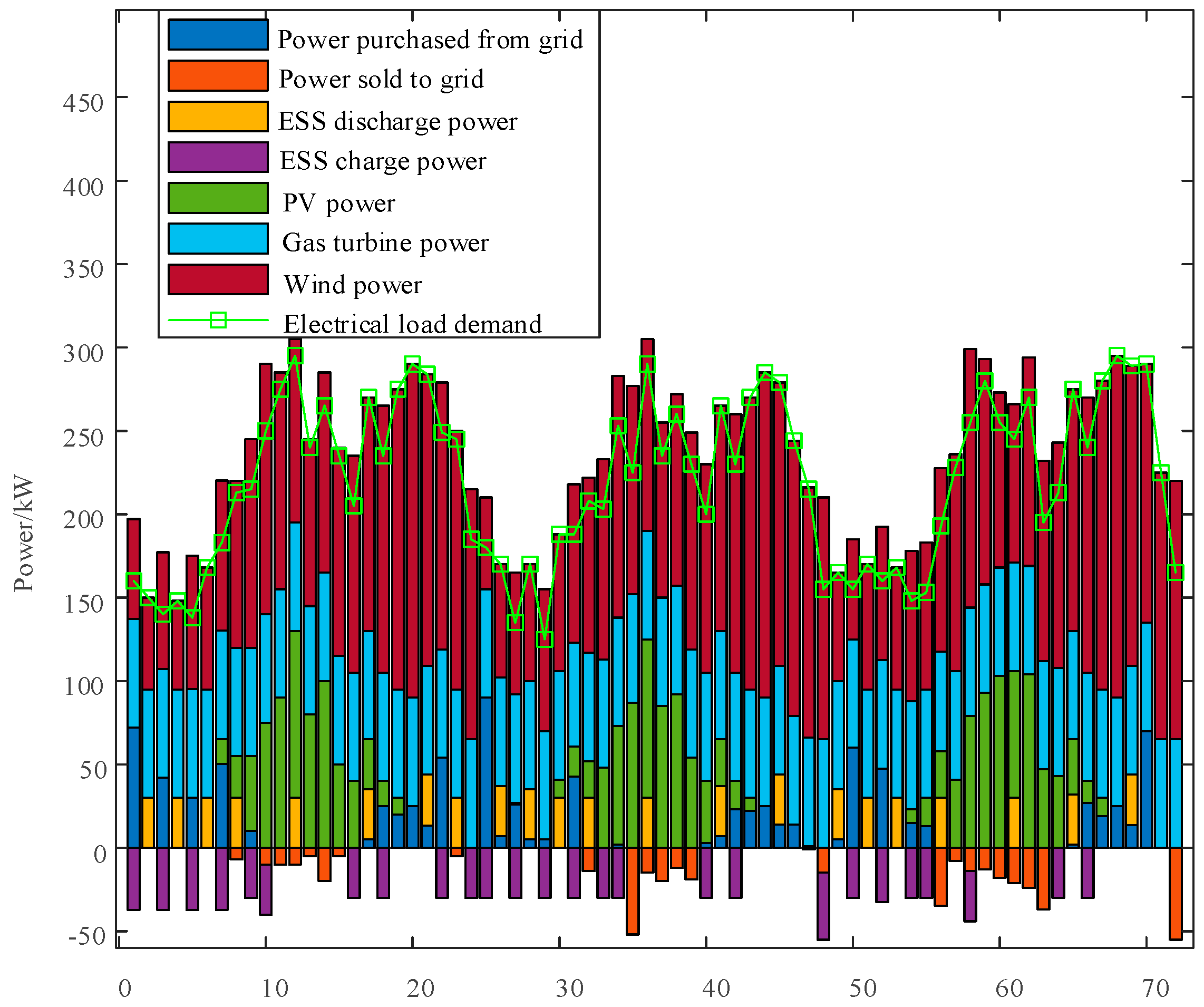

In summary, current academic research on MEVPPs predominantly focuses on the supply side, while the integration of demand-side flexibility resources into its low-carbon economic dispatch remains underexplored. To bridge this research gap, in this paper, a low-carbon economic dispatch model for MEVPPs that is compatible with multiple energy types and demand-side responses is proposed. This model uses shared electrical energy storage and shared thermal storage equipment to manage the charging and discharging operations of electrical and thermal energy. The effectiveness of the proposed model is validated using an IEEE 33-bus power system and a 20-node Belgian gas network.

Compared with existing studies, the novelty of this paper lies in three aspects: First, a MEVPP system model is constructed, which includes shared energy storage system, shared thermal storage system, wind power, photovoltaics, gas turbines, and gas boilers. Second, a multi-type demand response model incorporating shiftable, transferable, and reducible loads is considered, with detailed modeling for each type of demand response. Finally, a low-carbon economic dispatch model for the MEVPP is established, and a two-stage approach is adopted to account for the carbon emission costs of the MEVPP.

2. Multienergy Virtual Power Plant and Load Model

2.1. MEVPP Aggregation Mechanism and Model

The abbreviations of the key nouns in this paper are shown in

Table 1:

The main symbols and variable declarations in the formula are shown in

Table 2:

In the context of massive and highly heterogeneous distributed energy resources (DERs), feature identification and classification form the foundation of MEVPP aggregation. On the basis of the core parameters describing DER characteristics, in this paper, a DER parameter dataset is constructed, and feature extraction and classification of DERs are performed according to the external characteristic requirements of the MEVPP.

The screening criteria for electricity and heat users include the following: rated power, load characteristic curve, shiftable load, transferable load, curtailable load, response time, response duration, responsive capacity, and response time period.

For distributed photovoltaic and distributed wind power, the screening criteria include the rated power, output characteristic curve, reserve capacity, and ramping rate.

For gas turbines and gas boilers, the screening criteria include the following: rated power, upper and lower output limits, output ramp rate limits, and minimum uptime/downtime.

After feature extraction, the MEVPP employs a combined subjective–objective weighting method to determine the weight of each indicator, thereby screening high-quality DERs for aggregation. Taking electricity and heat users as an example, the procedure is as follows:

The subjective weighting method is employed to determine the subjective weight vector of the various criteria: Subjective weight coefficients are assigned on the basis of the importance the MEVPP places on each indicator when users participate in demand response.

The objective weighting method is employed to determine the objective weight vector of the various criteria: The weight is adjusted by fully considering the differences among various types of user responses, thereby reducing the weight of evaluation indicators with low variability and making the evaluation model more targeted.

Determine the weight coefficient vector

for scoring demand response users by integrating the subjective indicator weight vector

and the objective indicator weight vector

using the linear weighting method:

where

represents the linear weighting coefficient.it is selected by comprehensively considering economic benefits, electrical distance, and the influence of both electrical distance and carbon balance potential on aggregation; its value is typically taken as 0.5 [

24].

Calculate the DER evaluation score on the basis of the performance evaluation indicator weight vector

and the normalized scores of each performance indicator for the users:

where

and

denote the final evaluation score of user

i and the initial score matrix of their respective indicators, respectively.

is defined as the transpose of the weight vector coefficient

.

The MEVPP selects high-quality DERs for aggregation on the basis of their comprehensive performance evaluation scores.

The same procedure is subsequently applied to evaluate and select wind power units, photovoltaic units, gas turbines, and gas boilers. The final aggregated DERs form the MEVPP, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Analysis of User-Side Load Characteristics

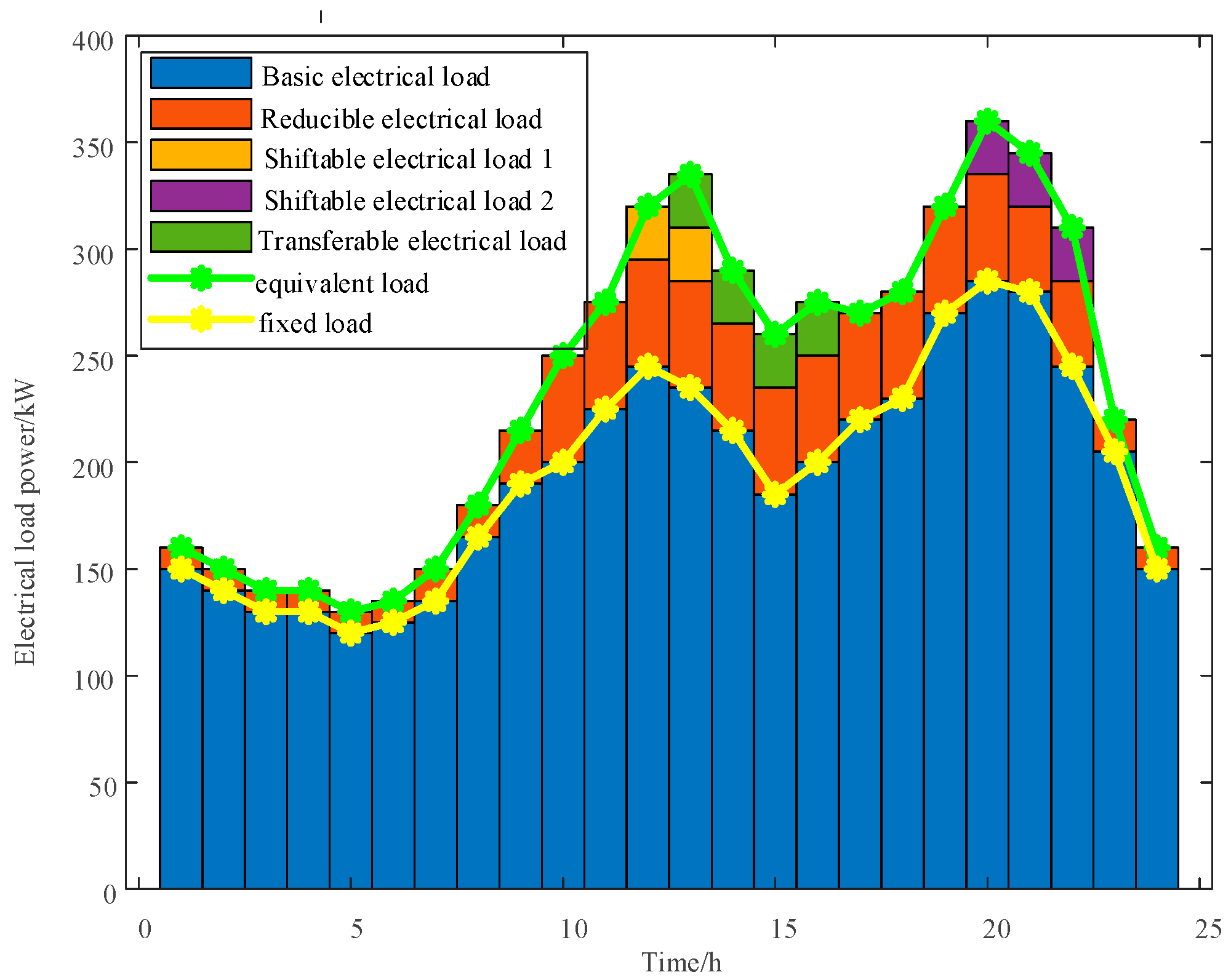

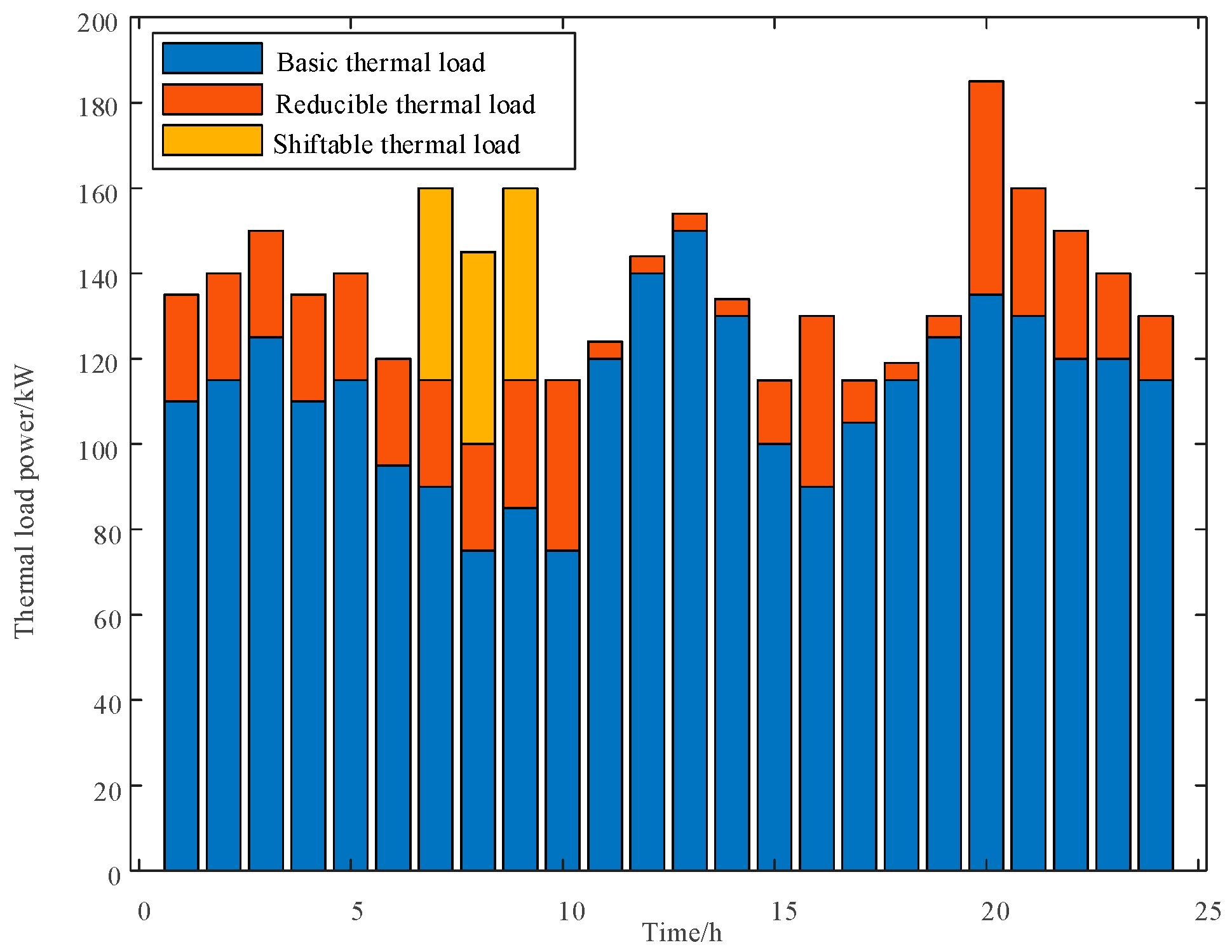

In the MEVPP constructed in this paper, the user-side loads include electrical loads and thermal loads. On the basis of their response characteristics, the user-side loads are recategorized as follows: rigid loads (must be satisfied and do not participate in dispatch), time-shiftable loads (whose operating time can be shifted but with a fixed power curve shape), power-adjustable loads (whose power can be adjusted within a certain range while maintaining constant total energy consumption), and interruptible loads (which can be partially curtailed during specific periods). Because thermal loads are generally more sensitive than electrical loads, curtailable electrical loads, curtailable thermal loads, shiftable electrical loads, shiftable thermal loads, and transferable electrical loads were comprehensively considered in this study. For example, the mathematical modeling of electrical loads is described below:

2.2.1. Shiftable Loads

In the model of this analysis, the dispatch duration for all types of demand-side response resources is 1 h. The loads vector

of shiftable loads vector

before scheduling is denoted as follows:

where

represents the start time interval and

represents the response duration,

represents the power shifted at time

.

Let

be the shift interval. Considering both the start time and duration of

, a binary variable

is introduced to indicate the state of

. The values of 0 and 1 for

represent the nonshifted and shifted states, respectively. Let

denote the set of start times for the shift:

If

, the load remains unchanged during that period. If

and

, then the power distribution vector

shifted from the start time interval

to the start time interval

of

is as follows:

The compensation cost

to be paid to the user after the shift can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the unit price for the demand response and

represents the total amount of load participating in the demand response.

2.2.2. Transferable Loads

Let

be the transfer interval, and introduce a binary variable

to represent the state of the transferable Loads vector

. For transferable loads, the maximum and minimum power constraints must be satisfied:

where

and

represent the minimum and maximum transferable power, respectively.

In this study, a constraint on the duration of the transferable load is introduced to prevent the load from being transferred across multiple time intervals, thereby reducing equipment wear, as shown in the following formula:

where

represents the minimum continuous operation time.

After the user performs the transferable load response, the MEVPP should pay the transfer compensation cost

:

where

represents the compensation price per unit power load transfer that the MEVPP needs to pay,

represents the transferable power at time

t.

2.2.3. Reducible Loads

Reducible loads represent the amount of load reduction by the user during a certain period. A binary variable is introduced to represent the state of the reducible load vector .

The load after participation in the demand response can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the load reduction coefficient in period

,

,

represents the power of

in period

before scheduling,

represents the power of

in period

after scheduling.

In the model developed in this paper, constraints on the consecutive reduce duration and the number of reduce events are added to increase users’ comfort. This part of the model can be expressed as follows:

Lower limit constraint on consecutive reduction periods

Upper limit constraint on consecutive reduction periods

Constraint on the number of reduction events

where

and

represent the minimum and maximum consecutive reduce periods, respectively;

is the upper limit for the number of reduce events;

represents the price per unit power load transfer that the MEVPP needs to pay;

represents the total cost of reducible loads.

2.3. Shared Energy Storage Model

When the MEVPP is connected to a shared energy storage station for low-carbon dispatch, the service fee paid to the shared energy storage station must be considered.

where

represents the shared energy storage cost paid by MEVPP,

represents the service fee paid by the MEVPP to the energy storage station,

represents the discharge power utilized by the MEVPP from the shared energy storage,

represents the charge power utilized by the MEVPP from the shared energy storage station, and

indicates the duration of a single dispatch period—in this paper, this parameter is assigned a value of 1 h.

The constraints include those for the charging and discharging of the shared energy storage, the state of charge (SOC) constraint, and the upper and lower power limits, which can be specifically expressed as follows:

The model for the shared thermal storage device is identical to that of the shared electrical energy storage device. Owing to space limitations, this parameter will not be elaborated upon further here.

3. Scenario Generation Based on the ARMA Method and Scenario Reduction

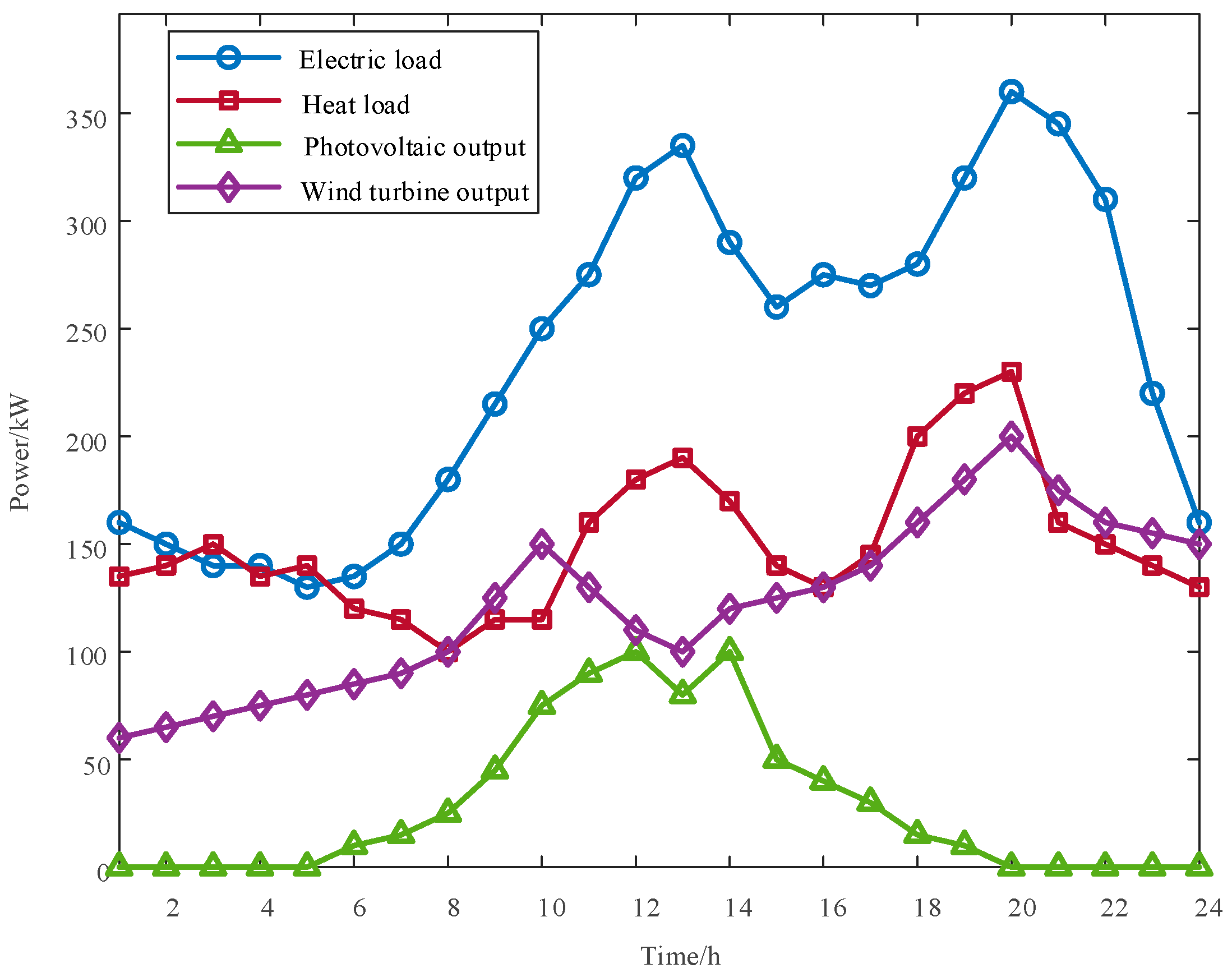

In this paper, the MEVPP aggregator encompasses entities with uncertain outputs, such as wind power, photovoltaic generation, and electric heating loads. Furthermore, uncertainties exist in the spot market electricity price and carbon trading price. Consequently, when formulating a dispatch plan, the MEVPP must first address these uncertainties. This paper employs scenario generation and reduction techniques to handle these uncertainties, describing them with a classical scenario set containing probabilistic information. Taking photovoltaic as an example, the remaining uncertainty processing methods are the same as this.

First, an Auto-Regressive Moving Average (ARMA) model is adopted to generate sampled scenarios for wind and photovoltaic power output:

where

represents the time series value at time

t,

is the autoregressive parameter,

is the moving average parameter, and

is gaussian white noise.

After generating the initial scenario set, this paper utilizes the fast forward selection technique based on probability distance for scenario reduction. The steps are as follows:

Step 1: Calculate the minimum geometric distance between each pair of scenarios s and s’ in set S.

Step 2: Identify the scenario d that has the smallest sum of probability distances to the remaining scenarios.

Step 3: Replace scenario d in S with scenario r, which is the geometrically closest scenario to d in S. Then, add the probability of d to that of r, forming a new scenario set S’.

Step 4: Determine whether the number of remaining scenarios meets the requirement. If not, repeat the above steps; if so, conclude the scenario reduction process.