To elucidate the mechanisms by which construction effects influence the bearing performance of deep-water pile-anchor foundations, this study investigates three principal aspects—foundation out-of-level, directional angle, and scour. Deviations in foundation levelness may induce non-uniform stress states within the pile anchor, thereby affecting overall bearing performance and displacement response. Directional-angle deviation directly determines the force-coupling relationship between the pile anchor and the mooring line, which in turn affects overall bearing performance and displacement response; directional-angle deviation also directly determines the force-coupling between the pile anchor and the mooring line and thus influences structural stability under combined wind-wave-current actions. The scour effect weakens the effective confinement of the soil surrounding the pile, reducing lateral resistance and uplift capacity.

It should be noted that the present analysis is conducted for the specific geotechnical and metocean conditions of the Wanning site, and the quantitative results should therefore be interpreted as a site-specific case study rather than universally applicable values for all seabed types. Nonetheless, the modelling framework and identified mechanisms are generic and can be readily extended to other soil profiles and foundation layouts. Future work will apply the same approach to a wider range of seabed conditions to assess how different soil types and stratigraphies influence the degree of capacity degradation induced by construction effects.

3.1. Foundation Out-of-Level

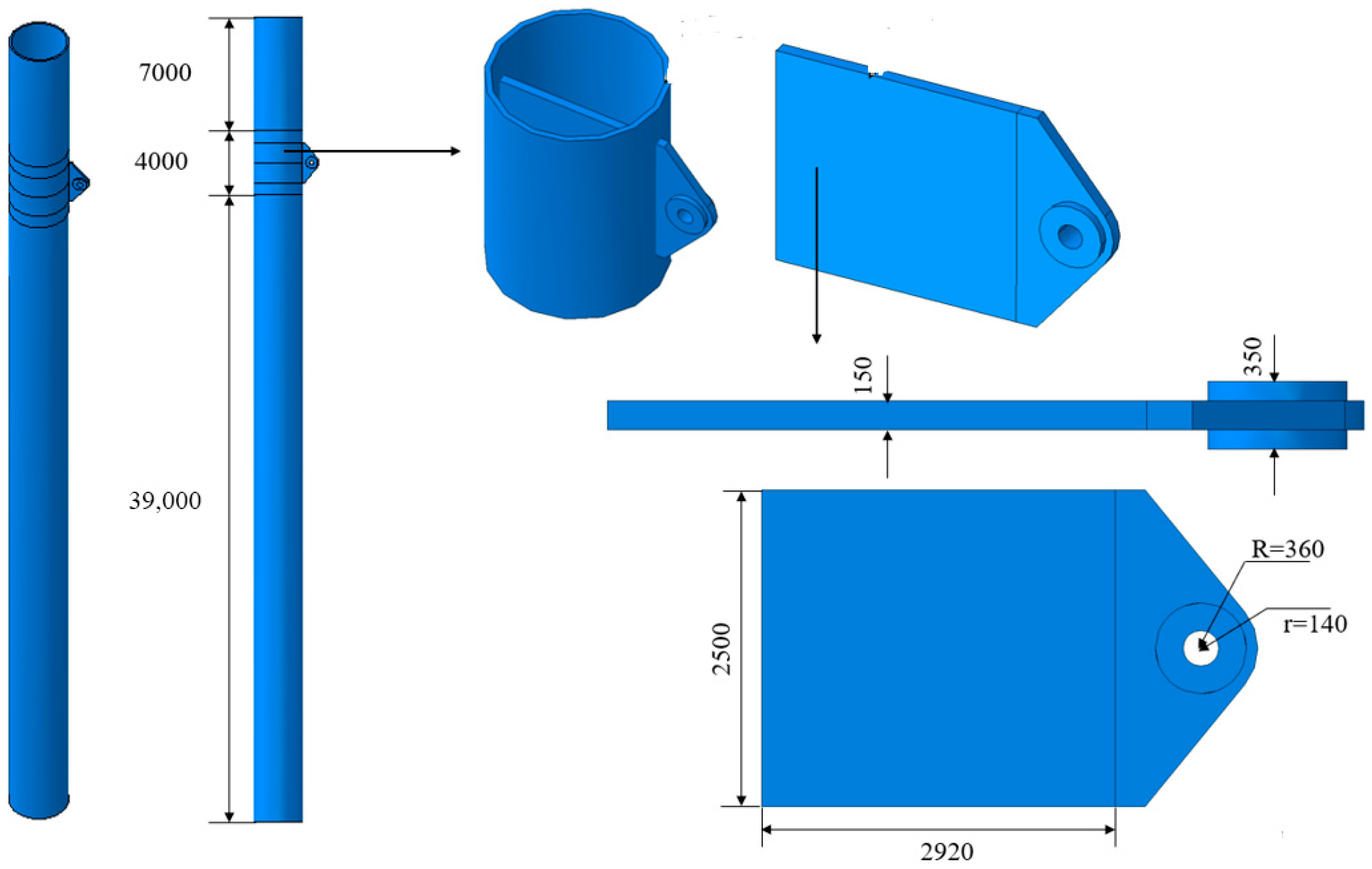

Foundation out-of-level refers to the levelness state of the anchoring foundation after construction, i.e., the degree of deviation between the foundation top surface or critical installation plane and the horizontal plane. It is one of the key indicators for assessing construction quality and directly affects the stress state and long-term service performance of the anchoring foundation. In deep-water environments, the construction of pile-anchor foundations mainly relies on vibratory driving, impact driving, or bored piling with post-grouting. During construction, due to vessel motion, ocean currents, and limitations in installation-equipment precision, the top-surface levelness of the pile often fails to meet design requirements. Out-of-level typically manifests as an angular deviation between the pile-top surface and the horizontal reference plane; it can usually be controlled within 0.5–2° but may reach 3–5° under complex sea states. In this study, an installation error of 5° is considered. The ABAQUS computational model is shown in

Figure 4, and the design cases are listed in

Table 3.

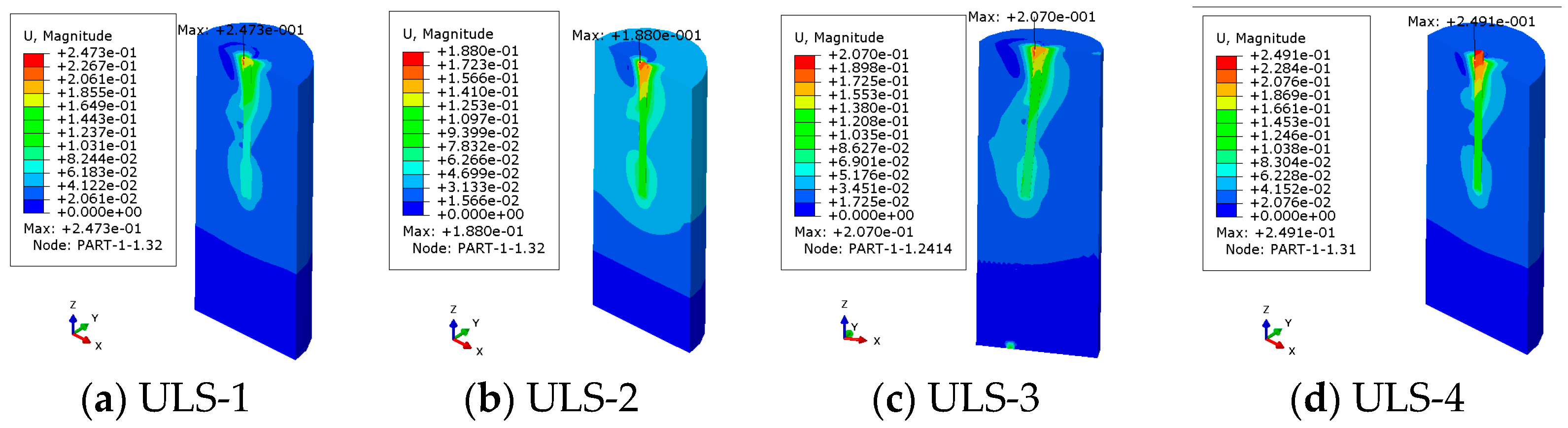

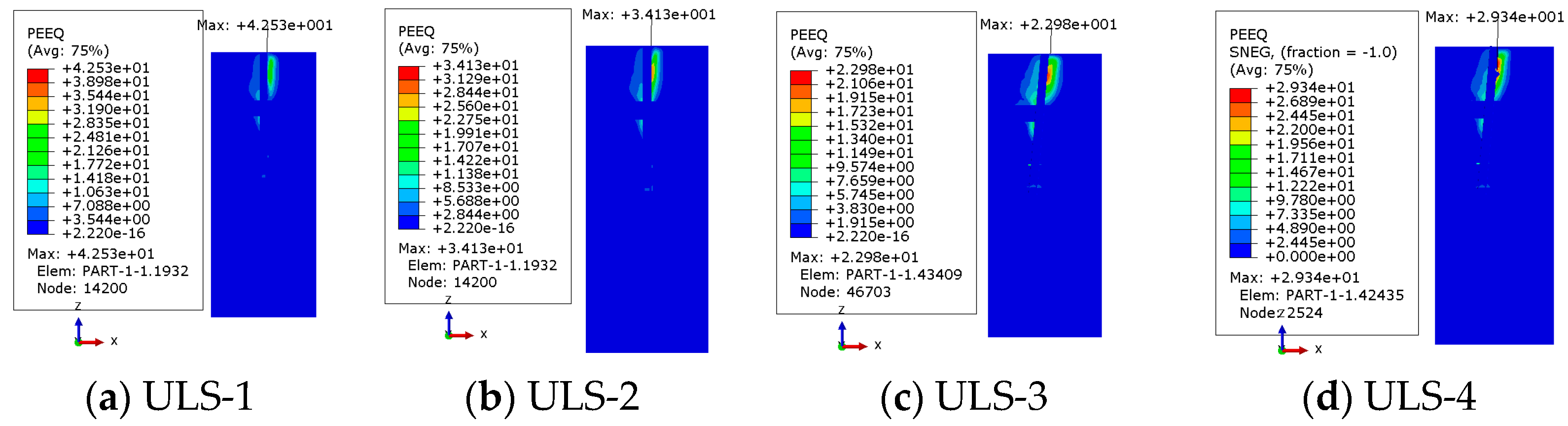

Figure 5 presents displacement contour plots of the soil surrounding the foundation under the four cases. It can be observed that the bearing behaviour of the pile anchor exhibits a typical pile–soil interaction pattern. Under loading, the soil on the windward (loaded) side of the upper pile experiences significant compression, forming a passive-resistance wedge; this region shows the largest displacements, which then attenuate rapidly outward and with depth. The distributions of the soil displacement fields are essentially consistent across all four cases, indicating that the installation error and load deflection angle considered in this study do not alter the primary load-transfer path or the soil failure mode. The pile undergoes an approximately rigid-body rotation about a point near its lower section, with the maximum displacement occurring at the pile head. Under ultimate conditions, the maximum pile-head displacement is within 0.20 m.

It is also noted that the largest pile-head displacement occurs for the 30° loading direction, whereas the displacement becomes slightly smaller when the loading direction is changed to 45° or when a 5° out-of-level installation is introduced. This apparently non-monotonic trend can be explained by the combined effects of load decomposition and the adopted ultimate-state criterion. For a given resultant mooring load, a 30° loading direction produces a larger horizontal component but a smaller vertical component than a 45° direction. Consequently, the 30° case is dominated by lateral loading and bending, which leads to greater pile-head rotation and lateral displacement. In contrast, the 45° case mobilises a larger share of axial compression, increasing confinement around the pile and enhancing the lateral stiffness, so that the maximum displacement at ultimate load is reduced. When a 5° out-of-level installation is considered, the characteristic resistance decreases. As a result, the ultimate state is reached at a lower load level than in the perfectly level cases. Under the present definition of ultimate capacity, this reduction in means that the pile anchor is not pushed to as large an absolute displacement as in the level reference configuration, even though its stiffness and resistance are degraded. Physically, out-of-level installation and load misalignment induce an eccentric load path and a non-uniform redistribution of soil reactions, with increased contact stresses and passive wedges on the downslope side and partial unloading on the upslope side. This evolution of normal and shear stresses along the pile–soil interface, as captured by the contact model, explains why the system exhibits lower capacity but does not necessarily develop a larger maximum displacement at its respective ultimate state.

Figure 6 shows the equivalent plastic-strain contours. On the windward side of the pile anchor, the soil exhibits upward-and-outward extrusion and flow, forming a typical passive failure wedge; macroscopically, this appears as heave in front of the pile, while downward movement occurs to some extent behind and beneath the pile, consistent with the rotational deformation mode of the pile under load. Plastic strain is not uniformly distributed; rather, it is highly concentrated in the passive zone on the windward side of the upper pile and in the vicinity of the pile–soil interface, fully corresponding to the pile-anchor loading mechanism.

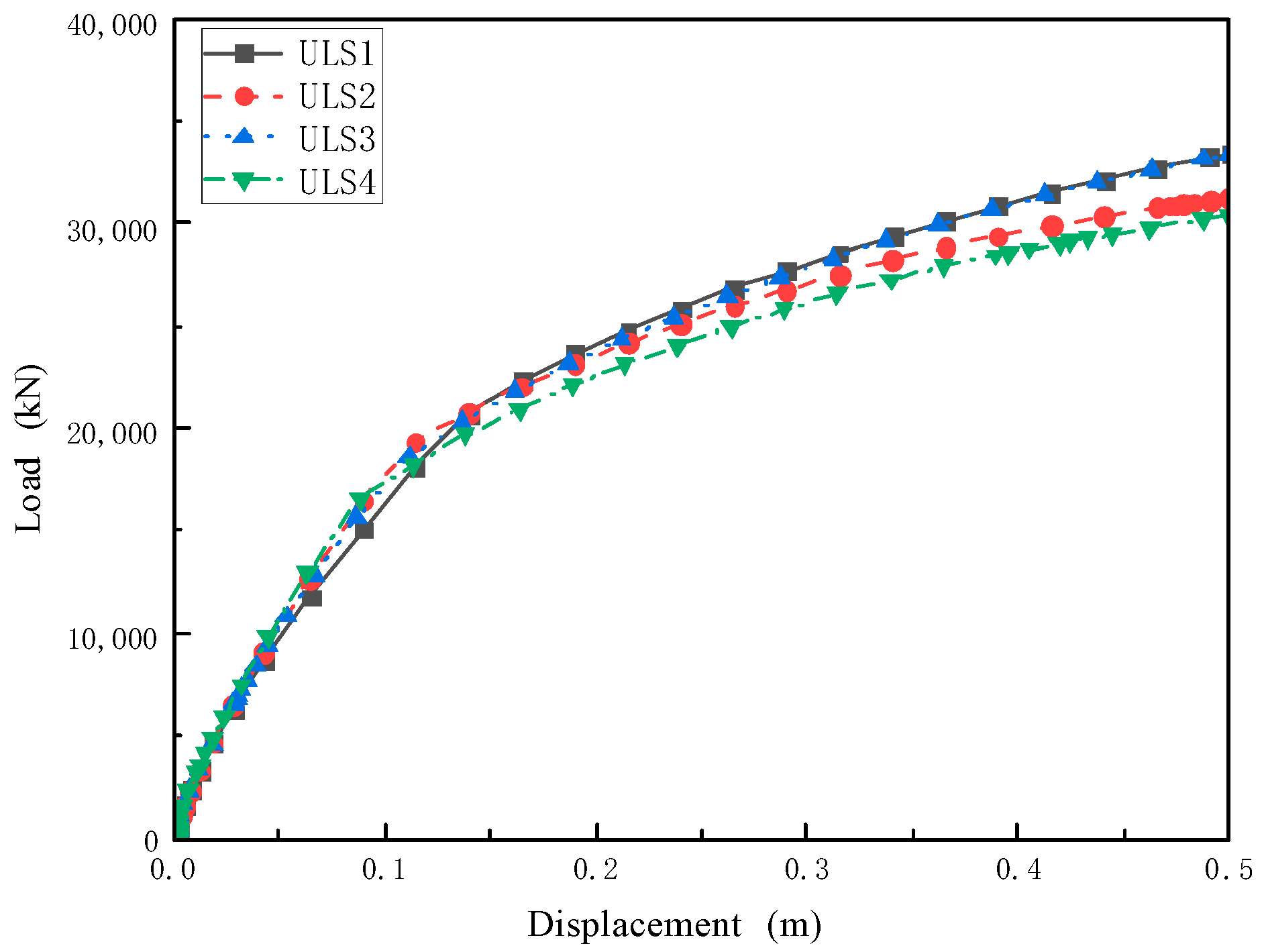

Figure 7 shows the load–displacement curves for the four cases. All four curves indicate that the bearing resistance of the pile anchor increases with displacement and tends to grow linearly after 0.2 m, implying a distinct initial stage of nonlinear consolidation and mobilization of frictional resistance, followed by a more stable bearing stage. When out-of-level is taken into account, the bearing capacity of the pile anchor decreases, and performance degradation is more pronounced under oblique loading (i.e., 45°). According to the load–displacement curves, when the loading direction changes from 30° to 45°, the characteristic resistance Rc decreases from 16,168.22 kN to 14,949.28 kN, corresponding to a reduction of about 7.5%. When a 5° foundation out-of-level is introduced, the degradation becomes more significant: for a loading direction of 30°, Rc decreases from 16,168.22 kN to 14,339.82 kN, and for 45° it decreases from 14,949.28 kN to 12,850.77 kN. The combined effect of out-of-level and directional-angle deviation therefore leads to a reduction in Rc from 14,339.82 kN to 12,850.77 kN, about 10.38%.

These trends highlight that deviation in the loading direction has a more significant influence on bearing capacity than out-of-level alone, particularly under deep-water conditions where variations in load direction are superimposed on levelness errors. Physically, foundation out-of-level and load misalignment induce an eccentric load path and a non-uniform redistribution of soil reactions around the pile: the downslope side experiences increased compression and concentrated contact stresses, while the upslope side partially unloads and may locally lose contact. Within the adopted contact model, this leads to partial softening of the pile–soil interface thereby reducing the global stiffness and ultimate resistance of the pile anchor. These findings indicate that installation accuracy—both in terms of foundation levelness and alignment with the mooring load direction—should be prioritized in design and construction to mitigate adverse effects arising from cumulative deviations.

3.2. Directional Angle

During the construction of deep-water pile-anchor foundations, control of the directional angle is a critical factor affecting pile performance and structural stability. The directional angle generally refers to the in-plane angular deviation between the pile anchor and the design axis or the principal action direction of the mooring line. Ideally, the pile anchor should be strictly aligned with the design direction to ensure a rational force path and smooth load transfer. In practice, however, due to vessel-positioning errors, insufficient precision of installation equipment, and disturbances from currents and waves, a certain directional-angle deviation often arises. Such deviation alters the distribution of soil reactions around the pile, introducing asymmetry into the pile–soil interaction that would otherwise be more uniform. Especially in clay or sand, increasing the directional angle is often accompanied by a reduction in effective lateral soil resistance, resulting in diminished lateral bearing capacity of the pile. Recent experimental and numerical studies on pile anchors for floating offshore wind turbines under inclined or multidirectional loading have also highlighted the sensitivity of pile response to load inclination and direction, but generally without explicitly considering construction-induced misalignment [

21,

22].

To reflect a more unfavourable environmental action, larger external loads are applied to simulate the structural response under extreme conditions. Accordingly, two Accidental Limit State (ALS) cases are defined with a load magnitude of 14,813 kN, while the loading inclinations remain 30° and 45°, respectively, to examine the safety margin and ultimate capacity of the pile-anchor foundation. The specific computational cases are summarised in

Table 4.

Figure 8 displays displacement contour plots of the soil surrounding the foundation under the four cases. As above, the pile anchor exhibits a typical pile–soil interaction pattern. Under loading, the soil on the windward side of the upper pile is significantly compressed, forming a passive-resistance wedge with the largest displacement, which rapidly attenuates outward and with depth. Under ALS conditions, the deformation zone around the pile deepens, indicating more non-uniform and concentrated loading on the pile, and a larger local soil-displacement state. The pile undergoes an approximately rigid-body rotation about a point near its lower section, with the maximum displacement occurring at the pile head. The maximum pile-head displacement under ultimate conditions is 0.247 m. When a 5° directional-angle deviation is introduced, the soil deformation becomes more pronounced. For the ALS-1 load, the maximum soil displacement reaches about 0.396 m for a 30° loading direction, whereas it is approximately 0.350 m for 45°. This indicates that the 30° case, with a larger horizontal load component, is more strongly governed by lateral loading and bending, leading to a more pronounced passive wedge and greater soil and pile-head displacements. In contrast, the 45° case mobilises a larger vertical component, enhancing axial compression and confinement of the surrounding soil, which slightly increases the lateral stiffness and reduces the maximum displacement despite the overall degradation in capacity. Physically, the combination of installation deviation and oblique loading induces an eccentric load path and a non-uniform redistribution of soil reactions around the pile: contact stresses and passive resistance are concentrated on the windward side, while the leeward side partially unloads. The resulting evolution of normal pressure and mobilised shear along the pile–soil interface, as captured by the contact model, provides the physical basis for the quantitative differences in displacement observed between the different loading directions.

Figure 9 provides the displacement-vector plots and equivalent plastic-strain contours. Comparison of the equivalent plastic-strain distributions under ULS and ALS indicates consistency in the overall failure pattern: a passive failure wedge forms in the windward soil in front of the pile, with plastic-strain concentration near the pile–soil interface. However, pronounced differences arise in the range and intensity of strain concentration across cases. In ULS-1 and ULS-2, the plastic-strain zone is primarily confined to the windward side of the upper pile; strains behind and beneath the pile are comparatively weaker, indicating a limited failure extent and overall stable bearing performance of the pile foundation. In ALS-1 and ALS-2, due to the increased applied load and the offset effect associated with the angle to the XZ plane, the plastic-strain band expands markedly—not only enlarging in front of the pile on the windward side but also showing stronger strain accumulation locally behind the pile—indicating a more complex and asymmetric failure tendency. In addition, under ALS the concentration of strain at the pile–soil interface intensifies significantly, suggesting that the pile foundation is more prone to local yielding and even instability under extreme loading.

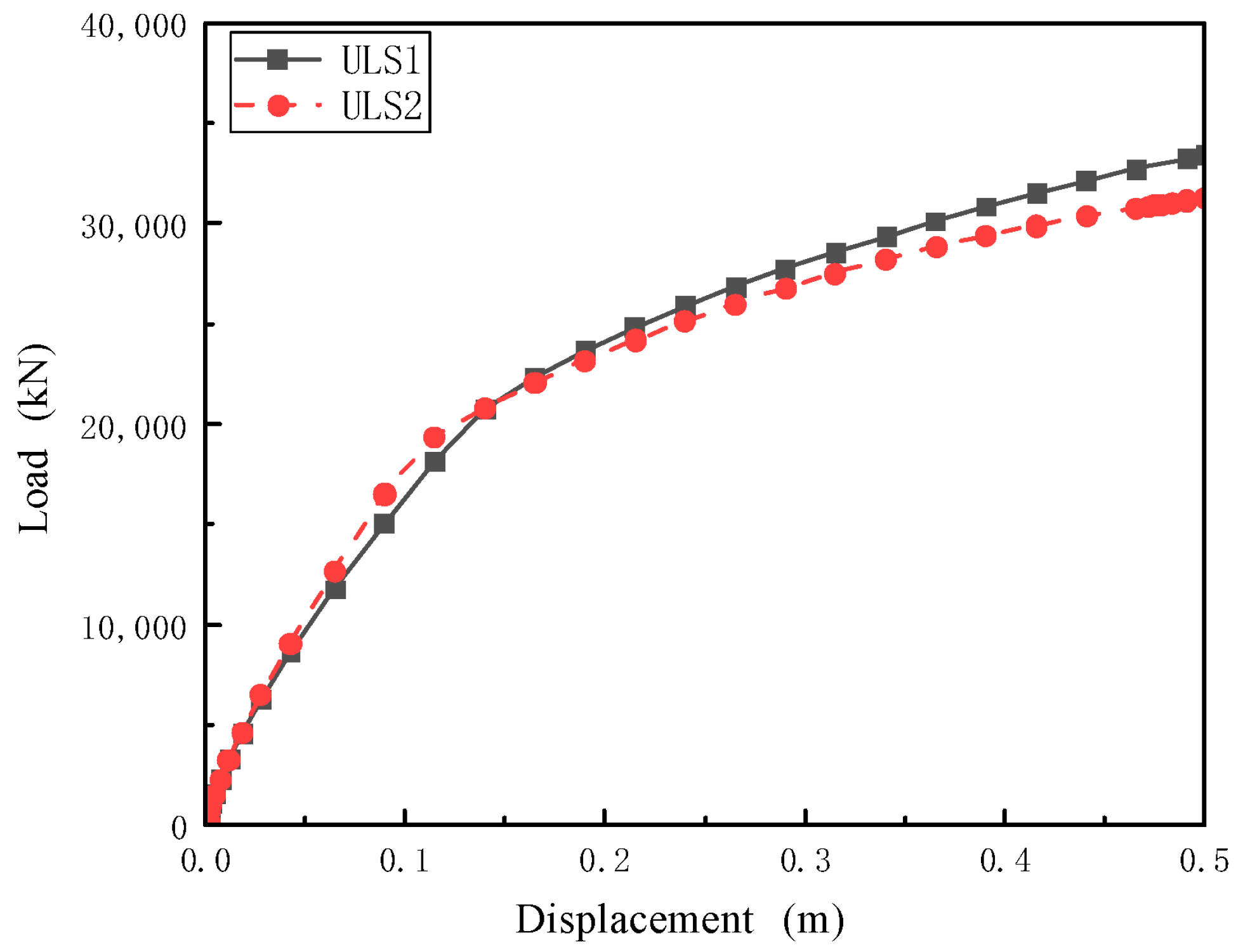

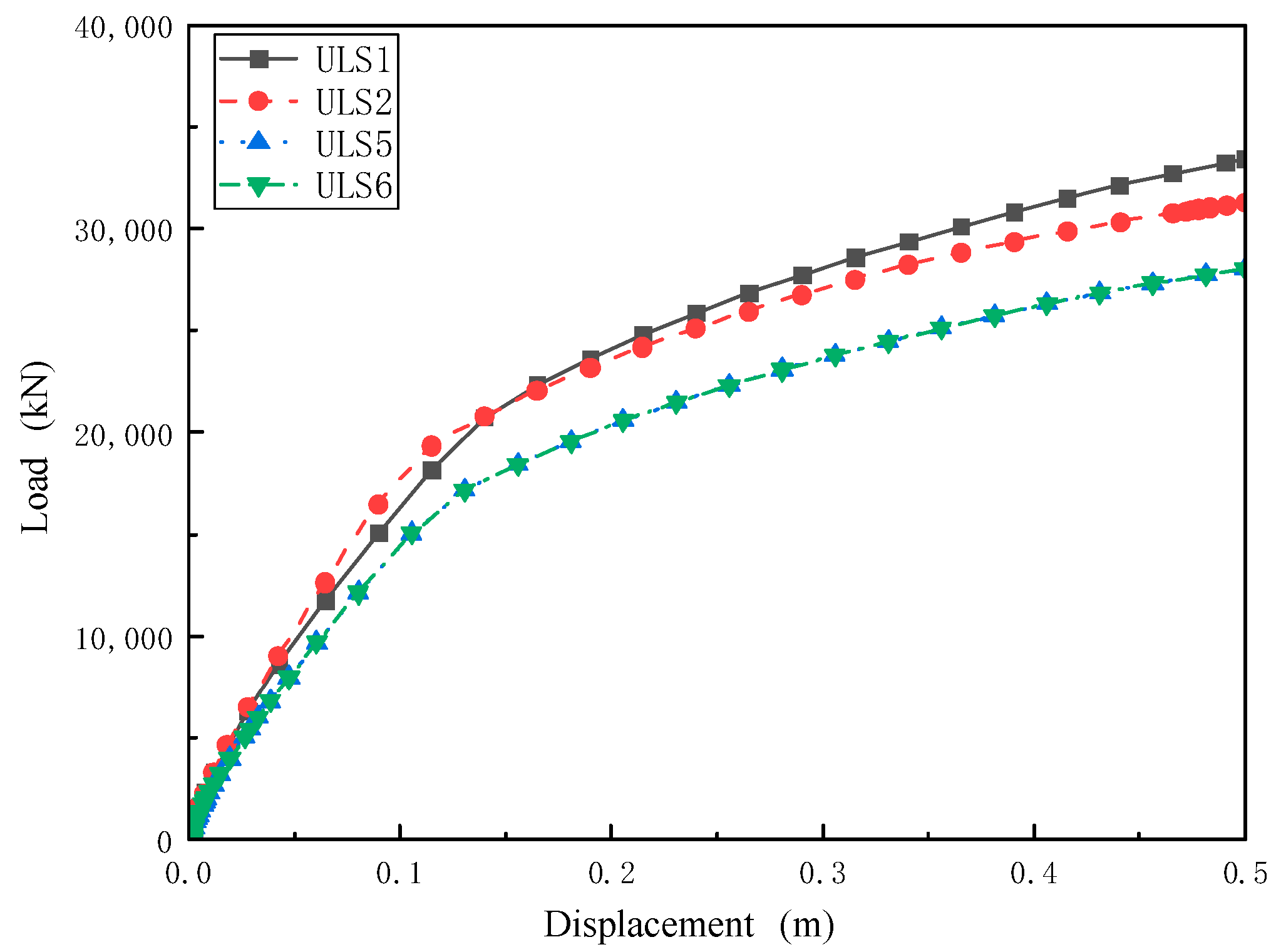

Figure 10 shows the load–displacement curves for the four cases. All four curves indicate that the pile-anchor bearing resistance increases with displacement and tends to grow linearly after 0.2 m; the ultimate resistance in all cases does not exceed 35,000 kN. This behaviour suggests a distinct initial stage of nonlinear consolidation and frictional-resistance mobilization, followed by a more stable bearing stage.

For the reference configuration, the characteristic resistance is 21,018.69 kN for a 30° loading direction and 19,434.06 kN for 45°, so rotating the load vector from 30° to 45° leads to a reduction in of about 7.5%. When an additional 5° directional-angle deviation is introduced, decreases to 20,701.75 kN for the 30° case and to 19,275.61 kN for the 45° case, corresponding to further reductions of approximately 1.5% and 0.8% relative to their aligned counterparts. These quantitative comparisons confirm that the pile-anchor bearing capacity is more sensitive to changes in the inclination of the load with respect to the horizontal plane than to a small directional-angle deviation alone, while the combination of both effects leads to a cumulative degradation of capacity.

From a physical perspective, changing the loading direction modifies the coupling between the vertical, horizontal and moment components of the mooring load transmitted to the pile anchor. In the present configuration, the 45° loading direction induces a more unfavourable combination of lateral load and overturning moment, together with a more eccentric load path relative to the pile axis, which results in a non-uniform redistribution of soil reactions and limits the extent to which axial and lateral resistances can be fully mobilised in the direction of loading. The additional 5° directional-angle deviation further increases this eccentricity, leading to local concentration of contact stresses and earlier mobilisation of the pile–soil interface, and thus to the observed reductions in . Especially under deep-water conditions, where environmental loads vary in direction and may superimpose with installation deviations, these mechanisms can significantly degrade pile-anchor performance. Therefore, installation accuracy—both in terms of directional alignment and control of load inclination—should be prioritised in design and construction to reduce adverse effects arising from the accumulation of deviations.

3.3. Scour Effect

The scour effect refers to the process by which the soil surrounding a pile-anchor foundation is repeatedly transported, scoured, and eroded under marine hydrodynamic actions such as waves, tides, and swell. For offshore wind foundations, scour has been extensively recognised as a long-term serviceability and safety issue, and numerous experimental and numerical studies have quantified its impact on the deformation response, stiffness and bearing capacity of monopiles and other fixed-bottom foundations, as well as the role of various scour-protection measures [

23,

24,

25].

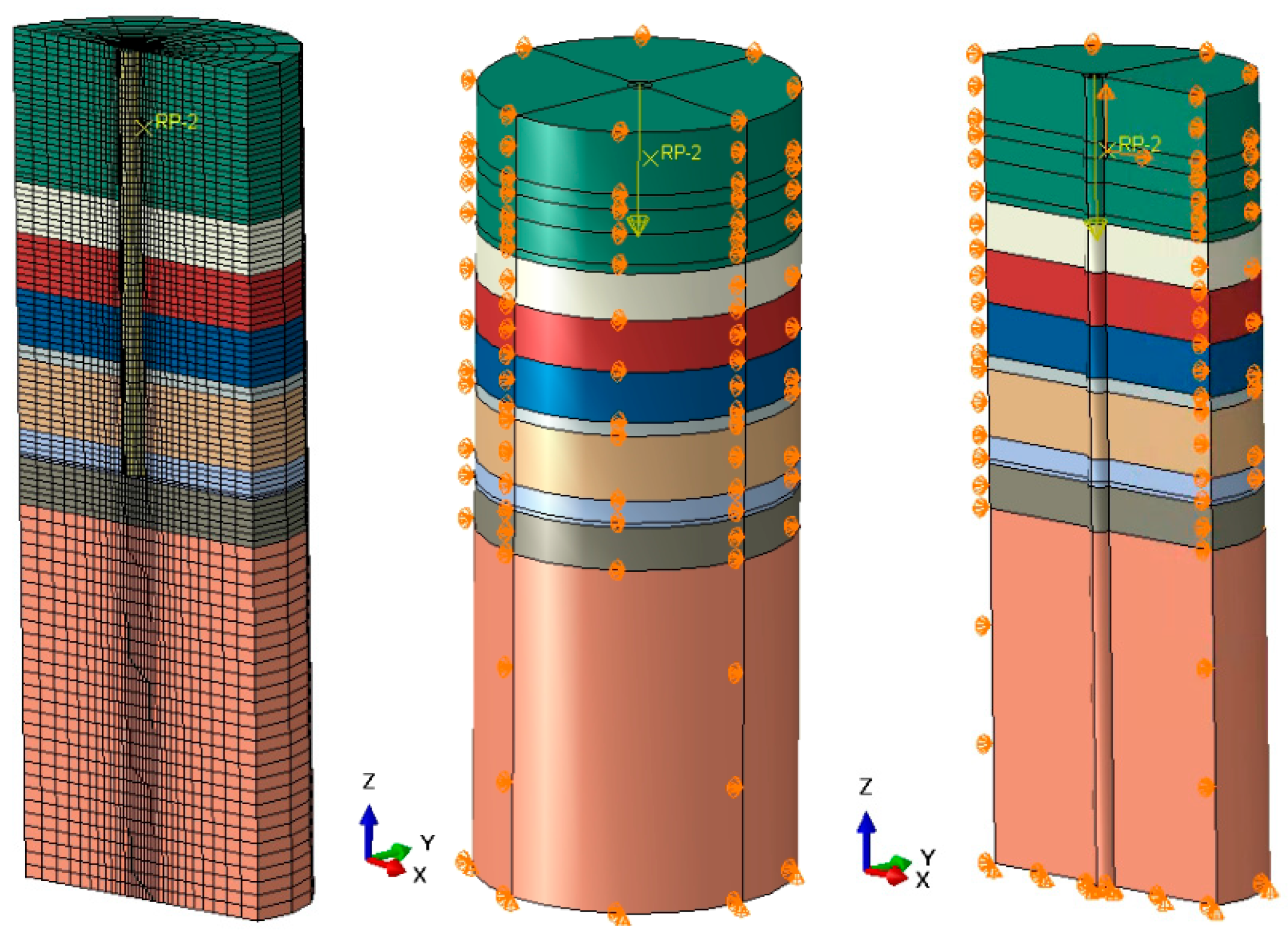

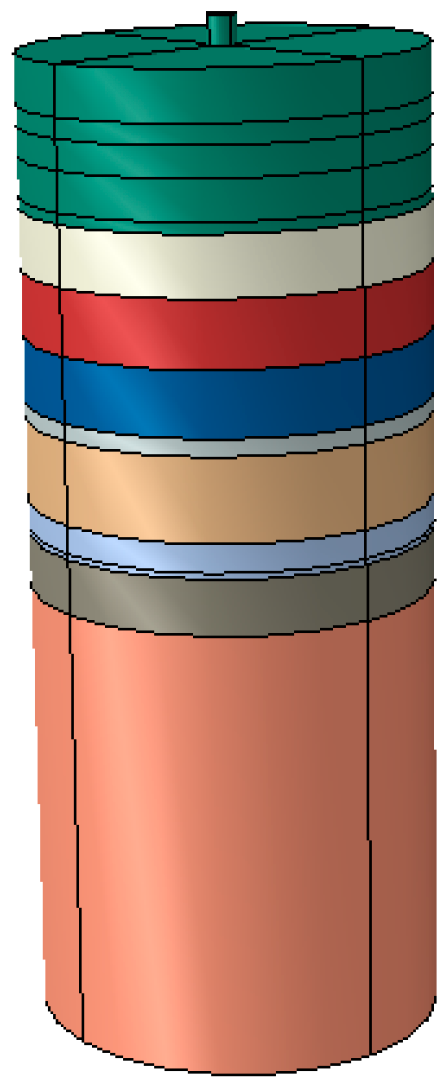

However, for deep-water pile-anchor foundations supporting floating offshore wind turbines, scour is not only a long-term service risk but also an important effect that must be considered during construction, when local flow-field variations and installation disturbances can trigger the formation of an initial scour pit shortly after installation. To investigate the influence of scour on the bearing performance of deep-water pile-anchor foundations for floating offshore wind, this study assumes an equivalent scour depth of 3 m around the pile—superimposed on the original design cases—and incorporates this effect into the numerical model for simulation and analysis. The scour model is shown in

Figure 11, and the specific computational cases are listed in

Table 5. By comparing bearing capacity, displacement response, and platform coupled-dynamic characteristics with and without scour, the degradation mechanisms induced by scour can be revealed, thereby informing the design and optimisation of subsequent scour-protection measures. In

Figure 11, different colours are used to distinguish soil layers with different geotechnical properties.

Figure 12 shows the displacement contour plots of the soil surrounding the foundation under the four cases. Under the 3 m scour condition, overall soil displacements increase, albeit modestly. The displacement contours indicate that, for ULS-5 and ULS-6 with the 3 m scour, the pattern of displacement change exhibits a trend similar to that in the baseline cases; notably, the magnitude and areal extent of displacement in the top region further increase with the severity of the case. Compared with normal conditions, scour reduces embedment depth and weakens the constraint at the structural base, ultimately decreasing the overall stiffness of the pile-anchor system. Consequently, larger horizontal displacements and lateral deformations occur, with a broader region of concentration.

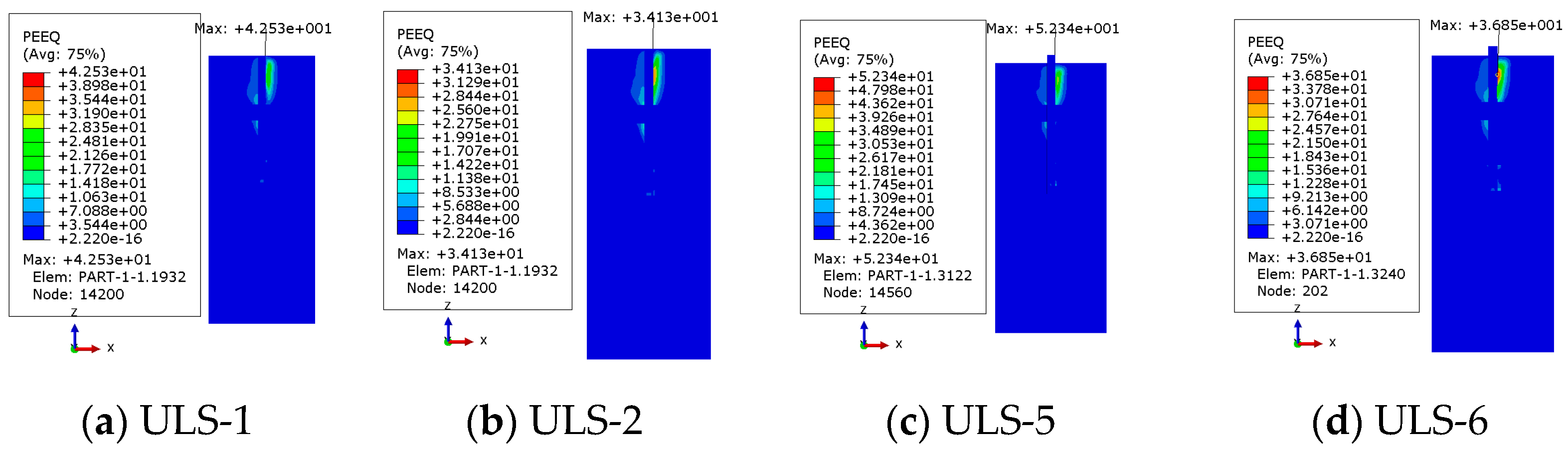

Figure 13 presents the equivalent plastic-strain contours. For ULS-5 and ULS-6 with 3 m scour, the plastic-strain distribution follows a trend similar to the baseline cases, but with a clearly increased failure intensity and reduced resistance of the soil surrounding the pile. Scour weakens the effective embedment depth of the pile, diminishing the soil’s contribution to bearing capacity. The plastic-strain band expands both in front of and behind the pile, with more pronounced heave in the region ahead of the pile. This indicates that, while scour does not directly alter the loading mode, it reduces the soil confinement; as a result, the safety reserve of the pile foundation under the same load level is lowered.

Figure 14 shows the load–displacement curves for the four cases. All four curves demonstrate that the bearing resistance of the pile anchor increases with displacement and tends toward linear growth after 0.2 m, indicating a distinct initial stage of nonlinear consolidation and frictional-resistance mobilization, followed by a more stable bearing stage. For the intact seabed, the characteristic resistance Rc is 21,018.686 kN for a 30° loading direction and 19,434.064 kN for 45°, the 45° case exhibits a reduction in Rc of about 7.5% relative to 30°. When a 3 m scour is introduced, Rc decreases to 17,317.495 kN for 30° and to 13,933.218 kN for 45°, corresponding to capacity losses of approximately 17.6% and 28.3% compared with their respective non-scour counterparts. Within the scoured cases, the 45° loading direction yields an Rc that is about 19.5% lower than that for 30°, indicating that scour not only reduces the overall capacity but also amplifies the directional sensitivity of the pile-anchor response.

These quantitative results highlight that, although the loading angle still affects the bearing performance, the pile-anchor capacity is much more sensitive to the presence of scour. Physically, scour removes the upper soil layer, weakens the confining action around the pile and reduces the effective fixity (embedment) depth. As a result, the stress bulb becomes shallower, the passive-resistance wedge on the loaded side is truncated, and the lateral and uplift resistances are less fully mobilised. Under oblique loading, the reduced overburden and shortened embedment depth lead to a more eccentric load path and a non-uniform redistribution of soil reactions, with higher bending moments and larger rotations concentrated near the scour depth. These mechanisms jointly explain the pronounced reduction in Rc under scour and the relatively smaller role of loading angle when compared with the dominant effect of scour-induced degradation of the pile–soil system.