Enhancing Vienna Rectifier Performance with a Simplified abc Frame Multi-Loop Control Scheme

Abstract

1. Introduction

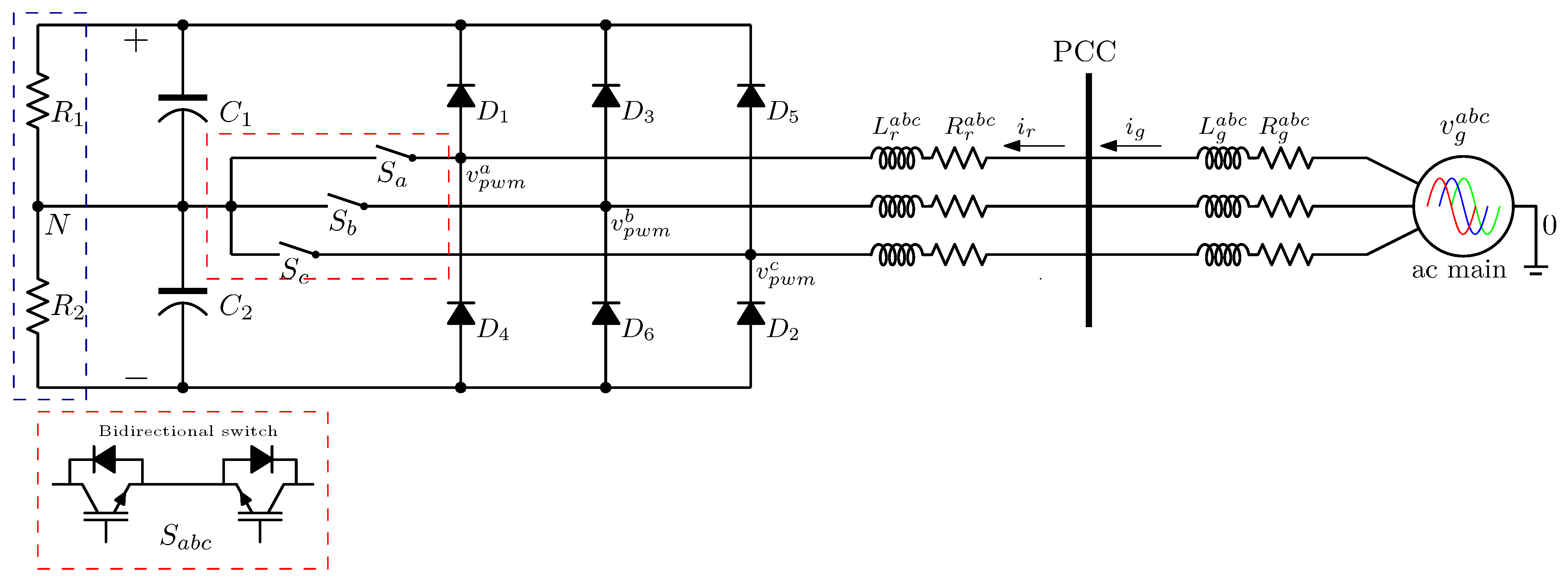

2. Vienna Rectifier Model

- All ac-main voltages are magnitude and phase balanced, such that ;

- All grid currents are magnitude and phase balanced, such that ;

- Semiconductor devices are idealized switches .

3. Control Law Synthesis

3.1. Current Tracking Error Dynamics

3.2. Linearizing Control Signals

3.3. Reference Current Generation

3.4. Stability Analysis

3.5. Design Rationale and Trade-Offs

3.5.1. Systematic Parameter Selection

- High-Frequency Gain (): The value of the high-frequency gain was determined based on the separation of time scales principle. The condition ensures that the internal current control loop operates significantly faster than the system’s natural resonant frequency, thereby providing effective decoupling of the dynamics and simplifying the outer voltage loop design.

- PI Controller Gains (, ): The proportional and integral gains for the outer voltage loop were tuned using the root locus technique. The design specifications targeted a damping ratio of (for minimal overshoot) and a settling time of less than 150 ms, resulting in a critically damped transient response suitable for power quality applications.

- Sampling Frequency: A sampling frequency of 10 kHz was selected. This frequency, which is over 100 times the fundamental line frequency, provides an optimal trade-off. It is sufficiently high to minimize aliasing effects and ensure accurate discrete-time control, while remaining within the practical computational limits of modern digital signal processors (DSPs).

3.5.2. Architectural Trade-Off: abc-Frame vs. -Frame

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Load Transient Response

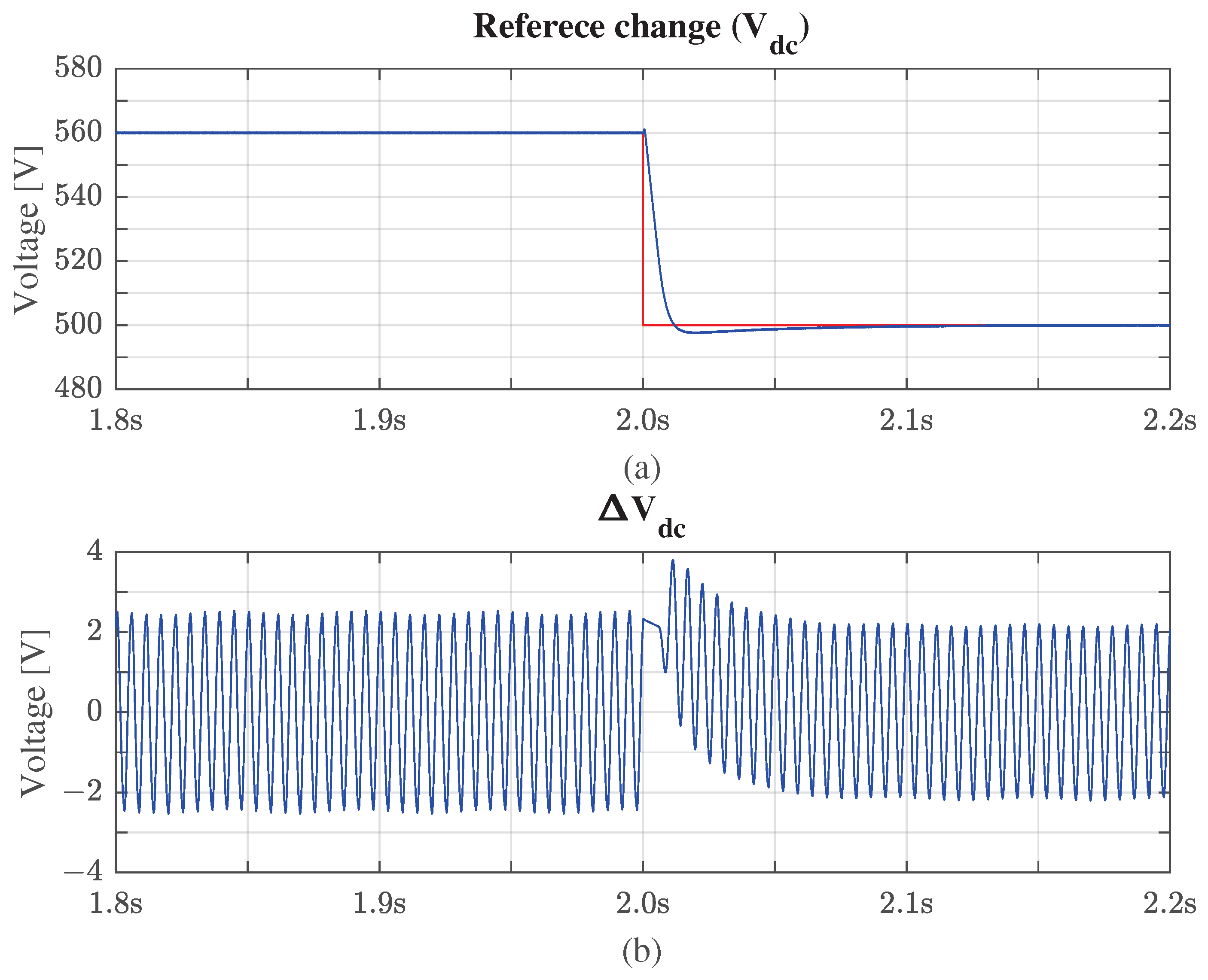

4.2. Reference Voltage Tracking

4.3. Voltage Sag: Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Cases

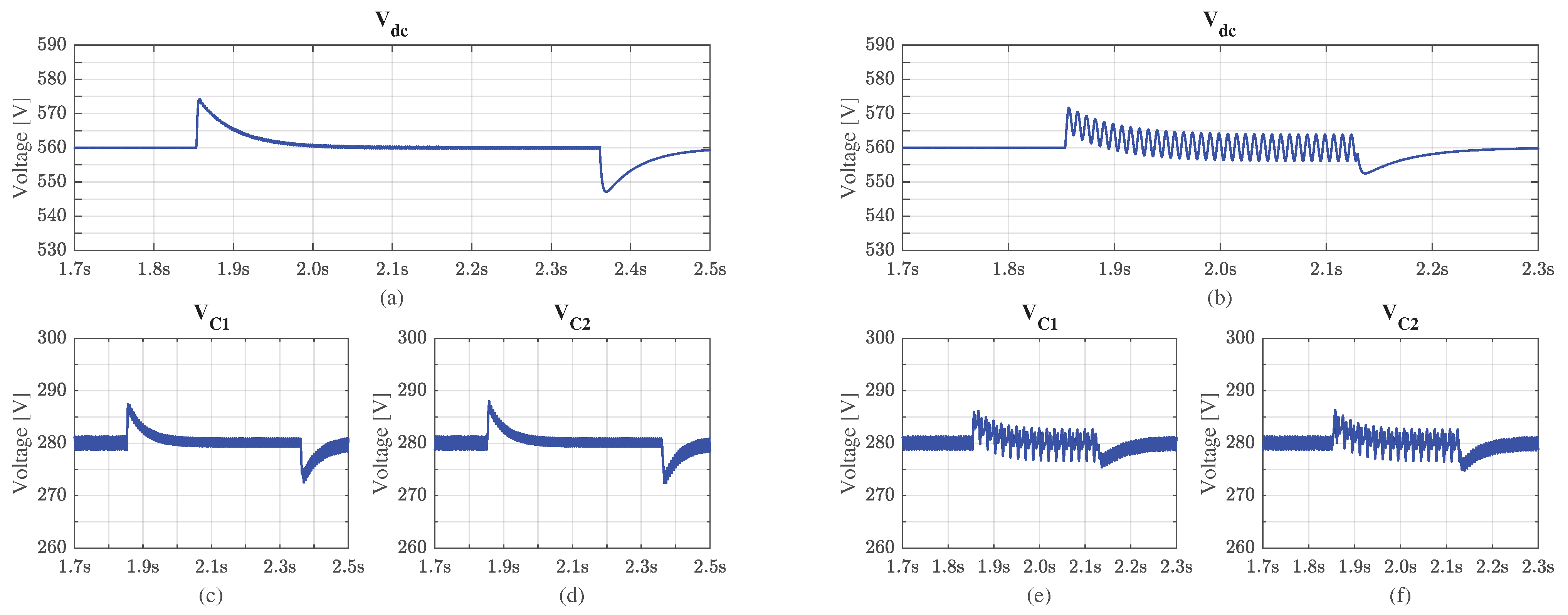

4.4. Voltage Swell Performance: Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Cases

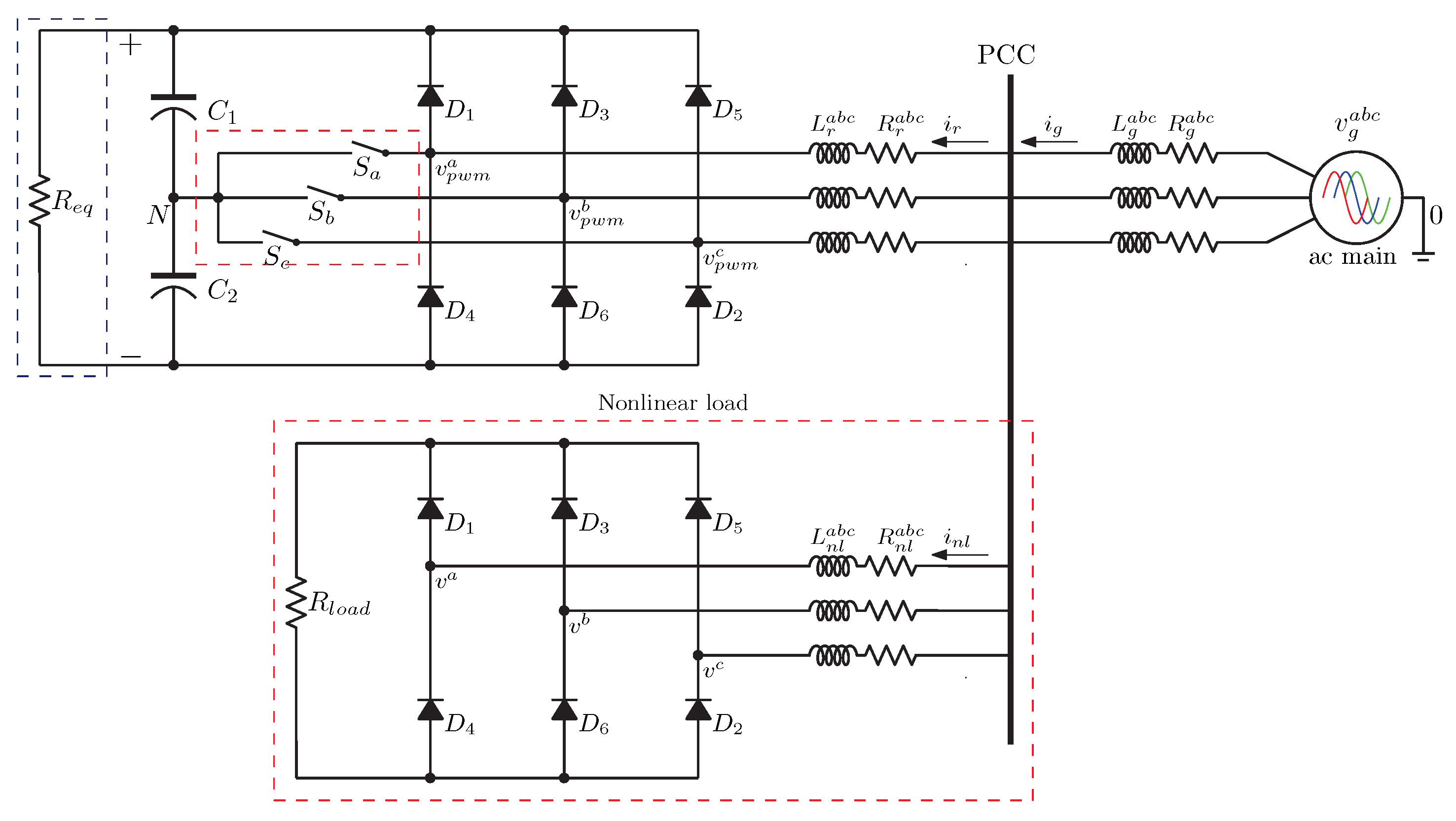

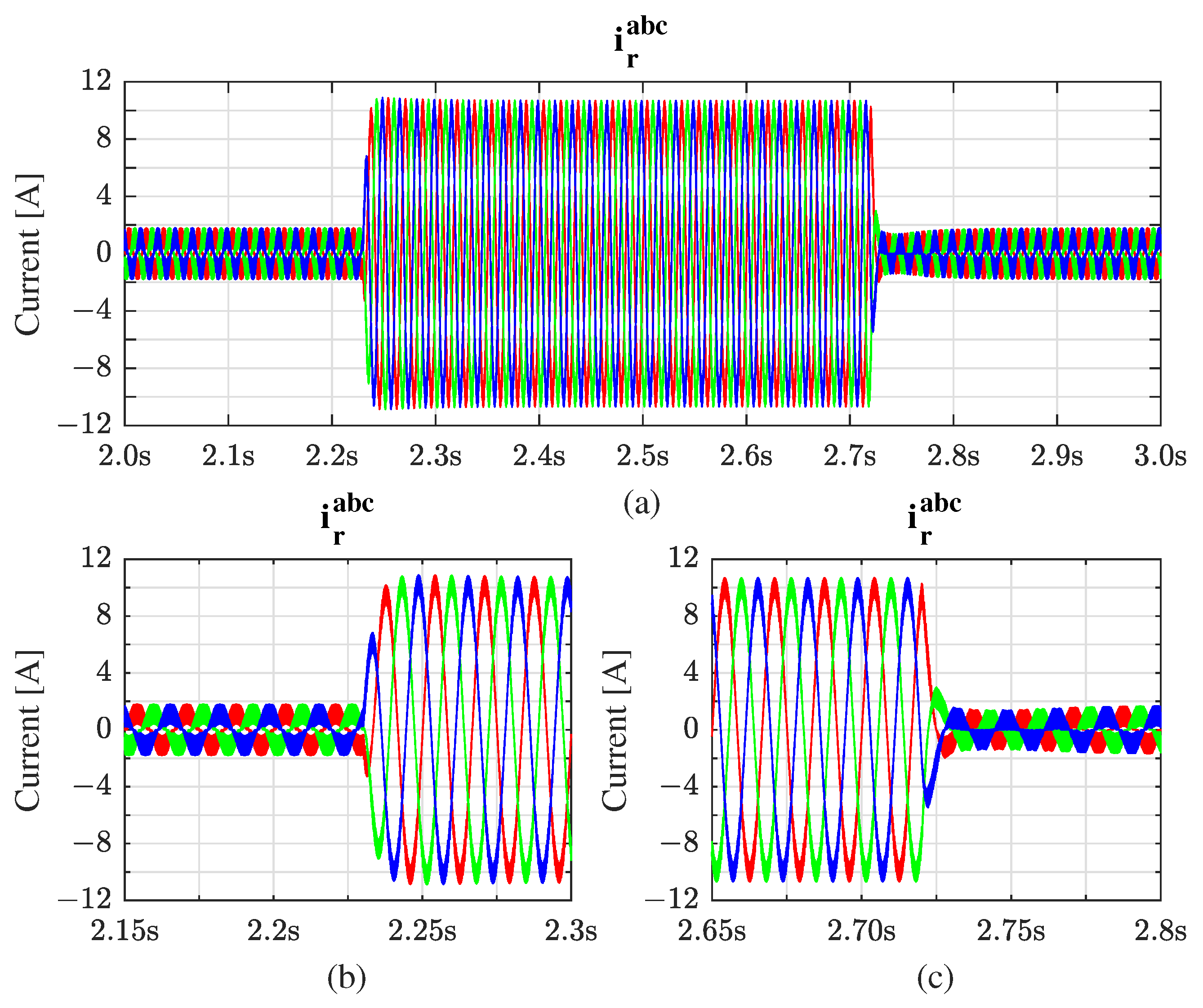

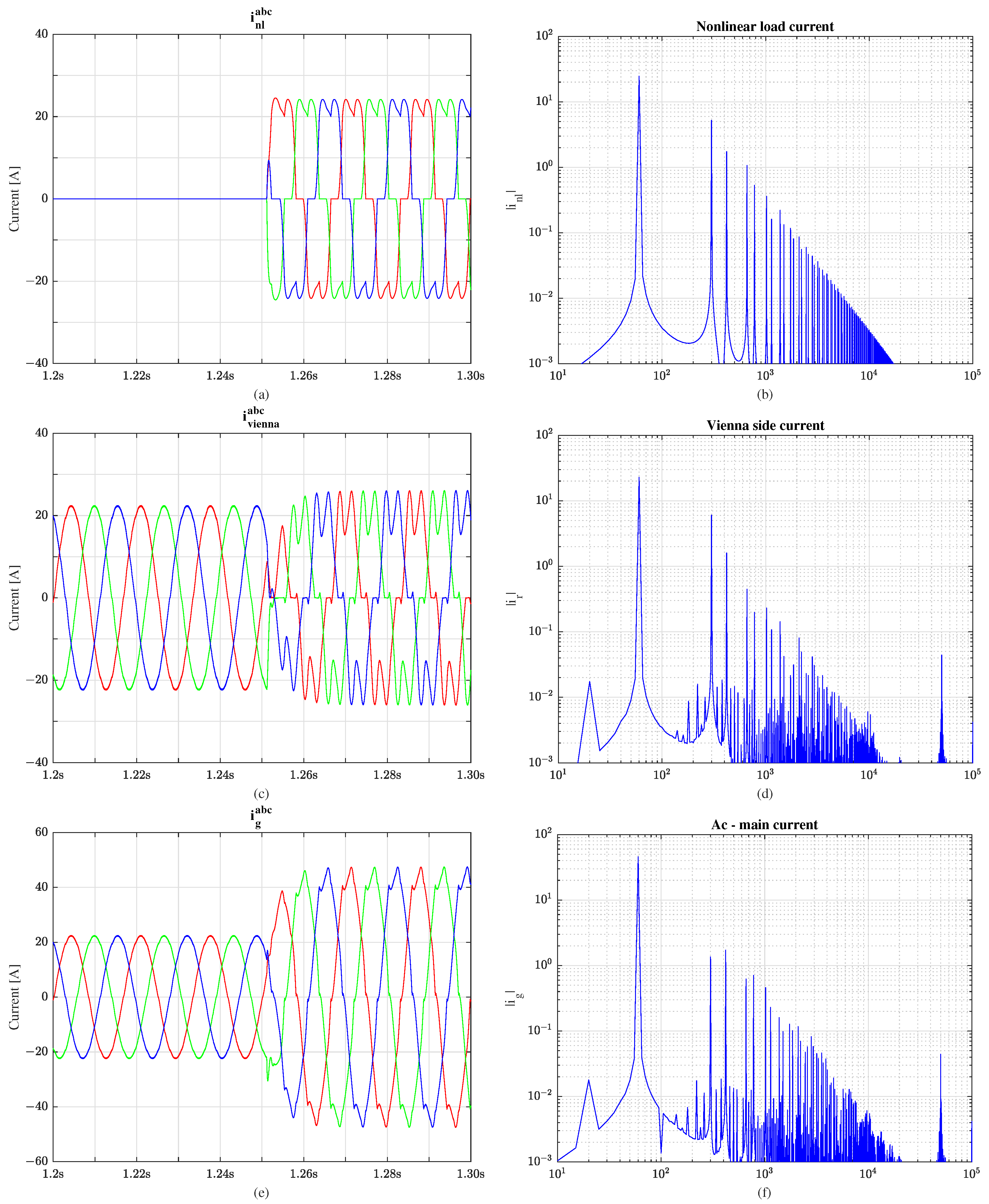

4.5. Nonlinear Load: Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Cases

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Review of Existing Control Strategies

5.2. Advantages of the Proposed Control Strategy

- Intuitive Physical Interpretation: Control actions correspond directly to phase variables, providing engineers with an intuitive understanding of the controller’s behavior, which simplifies tuning and debugging processes.

- PLL-Free Operation: By eliminating the need for a Phase-Locked Loop (PLL) for synchronization, the system achieves a faster dynamic response. This also removes a potential point of failure and instability, particularly under severely distorted or unbalanced grid conditions.

- Inherent Decoupling: During unbalanced grid faults (e.g., voltage sags), the controller naturally handles each phase independently. This inherent decoupling ensures stable operation without the need for additional sequence decomposition or decoupling networks, which are typically required in -frame controllers.

- Reduced Computational Burden: A comparative analysis of the control algorithms reveals an estimated 35% reduction in floating-point operations (FLOPS) compared to the standard -frame method. This reduction lowers the required processing power, allowing for the use of more cost-effective digital signal processors (DSPs) or enabling a higher control loop sampling rate.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

5.4. Industrial Applicability

- UPS Systems for Data Centers;

- EV Charging Stations requiring compliance with IEEE 519;

- Renewable Energy Interfaces connected to weak or fluctuating grids.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEEE Std 519-2022; IEEE Standard for Harmonic Control in Electric Power Systems. IEEE Standards Association: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Bath, S.K. Harmonic Distortion in Power Systems due to Electronic Control and Renewable Energy Integration: A Comprehensive Review. Discov. Electron. 2025, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalec, L.; Jasiński, M.; Sikorski, T.; Leonowicz, Z.; Jasiński, L.; Suresh, V. Impact of Harmonic Currents of Nonlinear Loads on Power Quality of a Low Voltage Network Review and Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, R.K.; Khanal, B.; Khatiwada, S.; Bhandari, N.; Rijal, B.; Karmacharya, R.; Thapa, A. Compensation for Reactive Power and Harmonic Current Drawn by a Non-Linear Load in a PV-Micro Hydro Grid. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.05342. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Mayoral, E.; Jiménez-Román, C.R.; Enriquez-Santiago, J.A.; López-López, A.; González-Domínguez, R.A.; Ramírez-Torres, J.A.; Rodríguez-Romero, J.D.; Jaramillo, O.A. Power Quality Analysis of a Microgrid-Based on Renewable Energy Sources: A Simulation-Based Approach. Computation 2024, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S. Optimization model for harmonic mitigation based on PV-ESS collaboration in small distribution systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 356, 122410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, M.H.J. Understanding Power Quality Problems: Voltage Sags and Interruptions; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y.; Guan, B.; Du, X. Vienna Rectifier Modeling and Harmonic Coupling Analysis Based on Harmonic State-Space. Electronics 2024, 13, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Fang, J.; Cheng, H.; Dong, L. A Novel Suppression Method for Input Current Zero-Crossing Distortion of the Vienna Rectifier Based on Negative-Sequence Current Regulation Under the Unbalanced Grid. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 3699–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.S. An Improved Zero-Current Distortion Compensation Method for the Soft-Start of the Vienna Rectifier. Electronics 2024, 13, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, D.; Tong, X.; Xin, W.P.Y. Model predictive control for Vienna rectifier with constant frequency based on inductance parameters online identification. J. Frankl. Inst. 2024, 361, 106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Jin, W.; Wu, F.; Liao, Y.; Le, S.; Wu, Y. Numerical Computation of Multi-Parameter Stability Boundaries for Vienna Rectifiers. Electronics 2024, 13, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Kumar, A.; Mohamed, H.G.; Sadhu, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Rangarajan, S.S.S.; Collins, E.R.; Senjyu, T. An Experimental Investigation and Feasibility Analysis of a Novel Modified Vienna Rectifier for Harmonic Mitigation in an Induction Heating System. Machines 2023, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharaneedharan, B.; Suresh, P.; Elumalai, P.V.; Mohammad, A. Energy-efficient Vienna rectifier for electric vehicle battery charging stations. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Li, Y. Sliding Mode Control of Vienna Rectifier Under Unbalanced Weak Power Grid. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 39095–39109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.H.; Xie, B.R.; Liu, J.S. A Novel Voltage Judgment Component Injection Scheme for Balanced and Unbalanced DC-Link Voltages in Three-Phase Vienna Rectifiers. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 13567–13577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yang, Y.; Du, M.; Wheeler, P. Study of Constant DC-voltage Control for Vienna Rectifier under No-load Condition. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 4730–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koodalsamy, B.; Narayanaswamy, V.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Ananthan, B. Implementation of Vienna Rectifier With Sliding Mode Control for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2024, 69, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Huang, L.; Liu, S. Space vector modulation strategy for VIENNA rectifier and load unbalanced ability. IET Power Electron. 2013, 6, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chen, L.; Miao, Y. Predictive Power Control Strategy Without Grid Voltage Sensors of the Three-Phase Vienna Rectifier. IET Power Electron. 2024, 17, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürçam, K.; Nuri Almalı, M. Single-Stage Modified Vienna Rectifier SEPIC AC–DC LED Driver. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, S.; Gupta, S.; Mazumder, S.K. A Modulation Scheme for Differential-Mode ZVS Resonant-Switched-Capacitor Rectifier for High-efficiency PFC. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 1467–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Albalawi, H.; Wadood, A.; Khan, S.; Alatwi, A.M. Harmonic Mitigation in Multi-Pulse Rectification: A Comparative Study of 12-, 18-, and 24-Pulse Systems. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, A.; Miftaks, T.I.; Nafisah, N.; Panjaitan, B. Design and Simulation of Vienna Rectifier for Harmonic Reduction in Electric Vehicle Charging Systems. J. Electr. Electron. Commun. Control. Inform. Syst. 2025, 19, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Sun, Y.; Cui, X.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y. A compound control strategy of three-phase Vienna rectifier under unbalanced grid voltage. IET Power Electron. 2021, 14, 2574–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, B.; Panchanathan, S. Hysteresis Current Control of Vienna Rectifier for Electric Vehicle Charging Systems. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2024, 17, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, J.W.; Zach, F.C. A novel three-phase utility interface minimizing line current harmonics of high-power telecommunications rectifier modules. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1997, 44, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Round, S.D.; Ertl, H.; Kolar, J.W. Digital Current Controller for a 1 MHz, 10 kW Three-Phase VIENNA Rectifier. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 2496–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Xie, X.; Zhao, C.; Liu, S. A Novel Control Strategy Based on Natural Frame for Vienna-Type Rectifier Under Light Unbalanced-Grid Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphan, M.C.; Soykan, G. Hybrid Control Strategy for VIENNA Rectifiers in More Electric Aircraft Electrical Systems. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 86686–86704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Liu, K.; Ran, X. Computationally Efficient Optimal Switching Sequence Model Predictive Control for Three-Phase Vienna Rectifier Under Balanced and Unbalanced DC Links. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 12268–12280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Su, M.; Huang, S. A Hybrid Control Scheme for Three-Phase Vienna Rectifiers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.H.; Hsu, W.H.; Xie, B.R. A Linearized Time-Invariant Voltage-Sensorless Direct Power Control for Three-Phase Vienna Rectifiers. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 59033–59048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Feng, X.; Dai, Z.; Ma, W. A Novel Optimal Voltage Vector Selection Control Strategy for Vienna Rectifier. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 49422–49430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, S.; Kurokawa, F. Analog Controlled Critical Conduction Mode Three-Phase Vienna Rectifier. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 6012–6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, S. An Improved Sliding Mode Direct Power Control Strategy Based on Reactive Power Compensation for Vienna Rectifier. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 15469–15477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Line voltage | 127 | ||

| Line frequency | 60 | ||

| Inductance | 4.7 | ||

| Resistance | 0.5 | ||

| Capacitance | 2400 | ||

| DC voltage | 560 | ||

| Output power | 3000 | ||

| DC resistance | 104.5 | ||

| Switching frequency | 10 | ||

| Proportional gain | 1.1 | ||

| Integral gain | 100 | ||

| Controller gain | 100 |

| Harmonic | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24.69233 | 45.83914 | 22.87478 |

| 5 | 5.23665 | 1.35395 | 6.06074 |

| 7 | 1.73234 | 1.71521 | 1.59762 |

| 11 | 1.07000 | 0.62599 | 0.44417 |

| 13 | 0.53083 | 0.71014 | 0.19934 |

| 17 | 0.36103 | 0.46210 | 0.23088 |

| 19 | 0.16150 | 0.22872 | 0.10582 |

| 23 | 0.22069 | 0.16012 | 0.14161 |

| 25 | 0.13310 | 0.09894 | 0.04030 |

| 29 | 0.11745 | 0.12776 | 0.02083 |

| 31 | 0.08107 | 0.10130 | 0.03130 |

| 35 | 0.08683 | 0.11625 | 0.08032 |

| 37 | 0.05585 | 0.06882 | 0.04777 |

| 41 | 0.06010 | 0.04710 | 0.02383 |

| 43 | 0.04693 | 0.05847 | 0.02207 |

| 47 | 0.04429 | 0.08184 | 0.04102 |

| 49 | 0.03198 | 0.05783 | 0.03060 |

| 53 | 0.03648 | 0.04600 | 0.02070 |

| THD (%) | THD (%) | THD (%) | |

| 22.95197 | 5.36301 | 27.51841 |

| Ref. | Control Scheme | Characteristics | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | Digital control P + Lag | THD , low time delay (300 ns) | High-complexity implementation; LVDS and RTL in FPGA; high latency. |

| [29] | ABC control, PR tracking + DDSM synchronization | High 2nd-order harmonic ripple reduction; THD not reported | Low unbalance support; unstable for unbalance over 50%. |

| [30] | Hysteresis current control; SOCI-PLL + PI-Resonant | THD , PF , DC ripple V | High numerical complexity; hybrid control with multiple controllers. |

| [31] | OSS-MPC with redundant vector | THD , DC deviation 50 V, runtime 4.7 μs | Uses lookup tables; search-time delay; no unbalance analysis. |

| [32] | PI + FS-MPC with observer | THD , PF | Variable switching frequency; limited stability region; short horizon. |

| [33] | Linearized time-invariant DPC with estimators | THD | Complex implementation; unbalance limited by defined k-factor. |

| [34] | FCS-MPDPC, SVPWM-Hysteresis | THD | Does not meet IEEE Std. 519 power-quality requirements. |

| [35] | Analog controller under critical conduction | THD , PF | Requires 4-wire system; efficiency depends strongly on load. |

| [36] | Sliding-mode DPC and ANN-RFB | THD | High computational burden due to ANN; good disturbance rejection. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miranda-Vidales, H.; Flota-Bañuelos, M.; Cruz, B.; Chan-Puc, F.I.; Espinosa-Trujillo, M. Enhancing Vienna Rectifier Performance with a Simplified abc Frame Multi-Loop Control Scheme. Energies 2025, 18, 6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246549

Miranda-Vidales H, Flota-Bañuelos M, Cruz B, Chan-Puc FI, Espinosa-Trujillo M. Enhancing Vienna Rectifier Performance with a Simplified abc Frame Multi-Loop Control Scheme. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246549

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiranda-Vidales, Homero, Manuel Flota-Bañuelos, Braulio Cruz, Freddy I. Chan-Puc, and María Espinosa-Trujillo. 2025. "Enhancing Vienna Rectifier Performance with a Simplified abc Frame Multi-Loop Control Scheme" Energies 18, no. 24: 6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246549

APA StyleMiranda-Vidales, H., Flota-Bañuelos, M., Cruz, B., Chan-Puc, F. I., & Espinosa-Trujillo, M. (2025). Enhancing Vienna Rectifier Performance with a Simplified abc Frame Multi-Loop Control Scheme. Energies, 18(24), 6549. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246549