Strategies for Solar Energy Utilization in Businesses: A Business Model Canvas Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Development of PV Technologies and Market Trends

2.2. Existing Photovoltaic Business Models in the Literature

- The ownership model, based on the direct purchase and installation of a photovoltaic (PV) system, represents an approach that provides the investor with full control over energy production and utilization. Although the investor bears the entire installation cost, in the long term this model offers significant savings on energy bills as well as environmental benefits. The integration of PV systems with modern energy storage technologies enables more efficient management of the energy generated. Owing to advancements in storage technologies, it is possible to accumulate energy and use it at optimal times, thereby maximizing the benefits of solar panels. As a result, system owners not only reduce their energy costs but also gain greater independence from the power grid. Owning a PV installation thus constitutes both an investment in environmental sustainability and a source of long-term financial benefits, providing complete control over one’s own energy source. This model is particularly advantageous for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) investing in PV systems to optimize energy costs, as well as for owners of single- and multi-family residential buildings. Overall, the ownership model is best suited for users who prioritize long-term returns and full autonomy over their energy system. Its capital-intensive nature, however, distinguishes it clearly from alternative models designed to reduce upfront investment barriers [20,21].

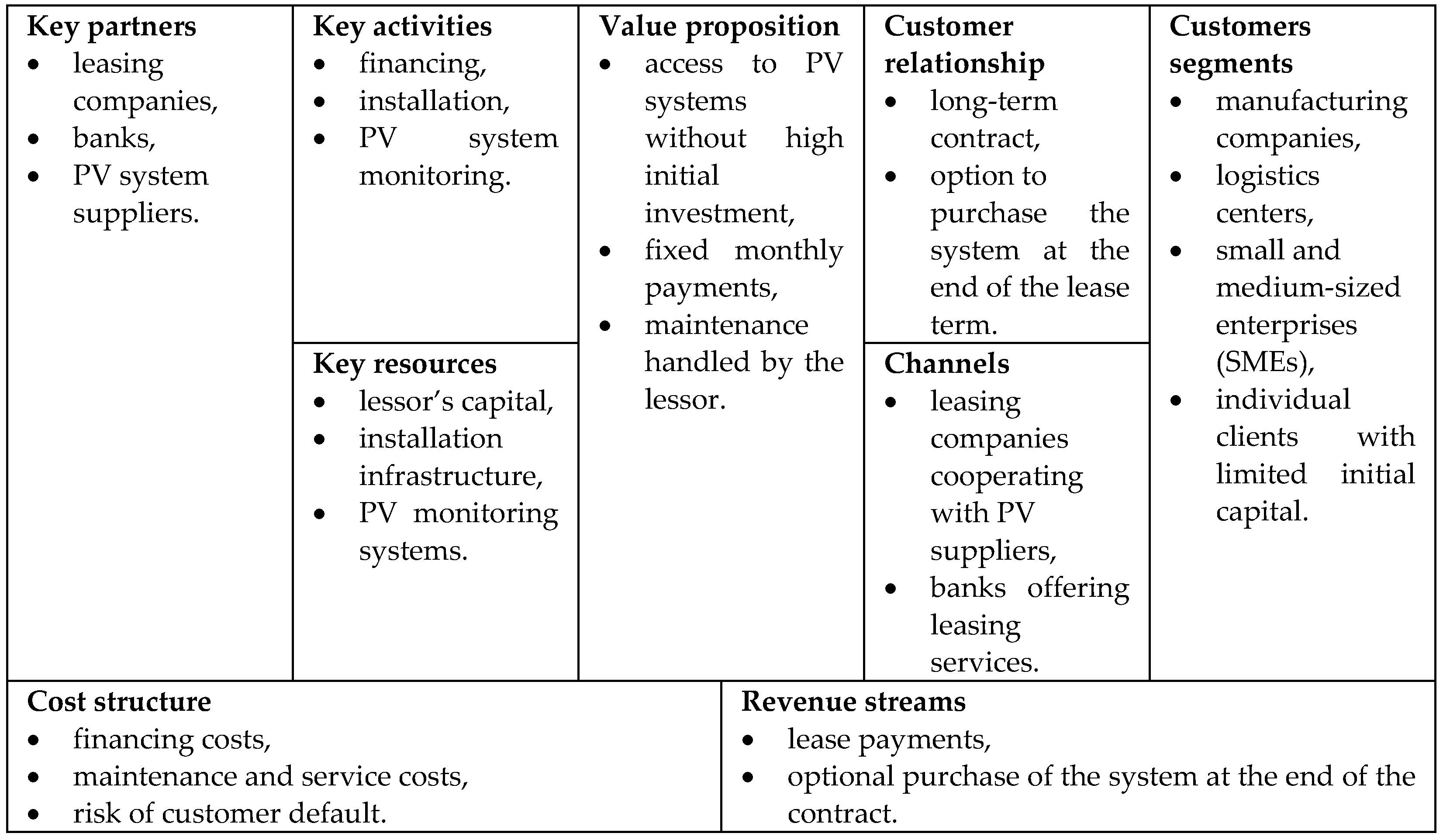

- The leasing model offers an attractive solution for individuals and enterprises seeking to benefit from solar energy without incurring substantial upfront investment costs. In this model, the user does not purchase the PV system outright but leases it from an energy provider for a specified period, typically under a leasing agreement. This arrangement allows users to take advantage of modern photovoltaic technologies and reduce electricity expenses while paying only monthly leasing installments. As a hybrid financing approach, leasing positions itself between full ownership and service-based models, providing users with both technological access and financial flexibility. Throughout the leasing term, the leasing provider often ensures system maintenance and servicing, thereby minimizing operational risks and additional costs. Leasing also provides an effective opportunity to evaluate the practical and economic viability of PV investments before making a full purchase decision. At the end of the leasing period, the user may choose to buy out the system, extend the contract, or invest in a proprietary installation, basing the decision on real operational experience. Thanks to flexible financing conditions, PV leasing becomes accessible to a broader range of users and businesses, enabling the adoption of clean and renewable energy without significant capital expenditure. This model is particularly advantageous for manufacturing companies and logistics centers aiming to avoid large-scale investment costs while still benefiting from renewable energy integration. Overall, the leasing model bridges the gap between full ownership and complete outsourcing, offering a flexible pathway to PV adoption. Its versatility makes it a popular intermediate solution for users who seek financial predictability while gradually transitioning toward long-term energy investments [22,23].

- The Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) model enables the use of solar energy without requiring the user to bear capital investment costs. In this approach, an external investor or PV system provider installs and manages the PV system on the client’s rooftop or premises and subsequently sells the generated electricity to the client at a pre-agreed rate. Through a PPA, building owners can access lower-cost electricity without purchasing or maintaining the PV panels themselves. The agreement specifies both the energy price and the contract duration, allowing for stable and predictable energy costs over the long term. This model is particularly attractive for companies and institutions seeking to mitigate financial risk and avoid upfront expenditure. The external investor assumes all installation, operation, and maintenance costs, while the client pays only for the electricity consumed, often at a rate lower than standard utility tariffs. By adopting the PPA model, users can benefit from renewable energy, minimize investment risk, and simultaneously reduce operational costs and the carbon footprint of their operations. This model is especially valuable for large industrial facilities and public institutions aiming to stabilize long-term energy expenses while maintaining full operational continuity. Additionally, a PPA enables organizations to accelerate their transition toward sustainable energy practices without the need for capital-intensive investments [23,24].

- Energy communities are initiatives in which groups of prosumers, individuals who both produce and consume energy, collaborate to optimize the utilization of renewable energy sources. In this model, energy surpluses can be shared among community members or sold directly to other users through a peer-to-peer (P2P) system. This approach enables the decentralization of the energy market and increases the independence of participants from traditional electricity suppliers. Community members can access cheaper and more sustainable energy, while simultaneously maximizing the benefits of their own PV installations. Typical applications of this model include residential neighborhoods where residents collectively manage energy production, companies and enterprises establishing local energy-sharing networks, and rural and urban communities investing in local PV installations to reduce their carbon footprint. Such energy-sharing frameworks also strengthen local resilience by distributing energy production across multiple sources, which reduces vulnerability to grid instabilities. Moreover, they foster greater social engagement around sustainability, encouraging communities to co-create long-term strategies for efficient and responsible energy management [3,25].

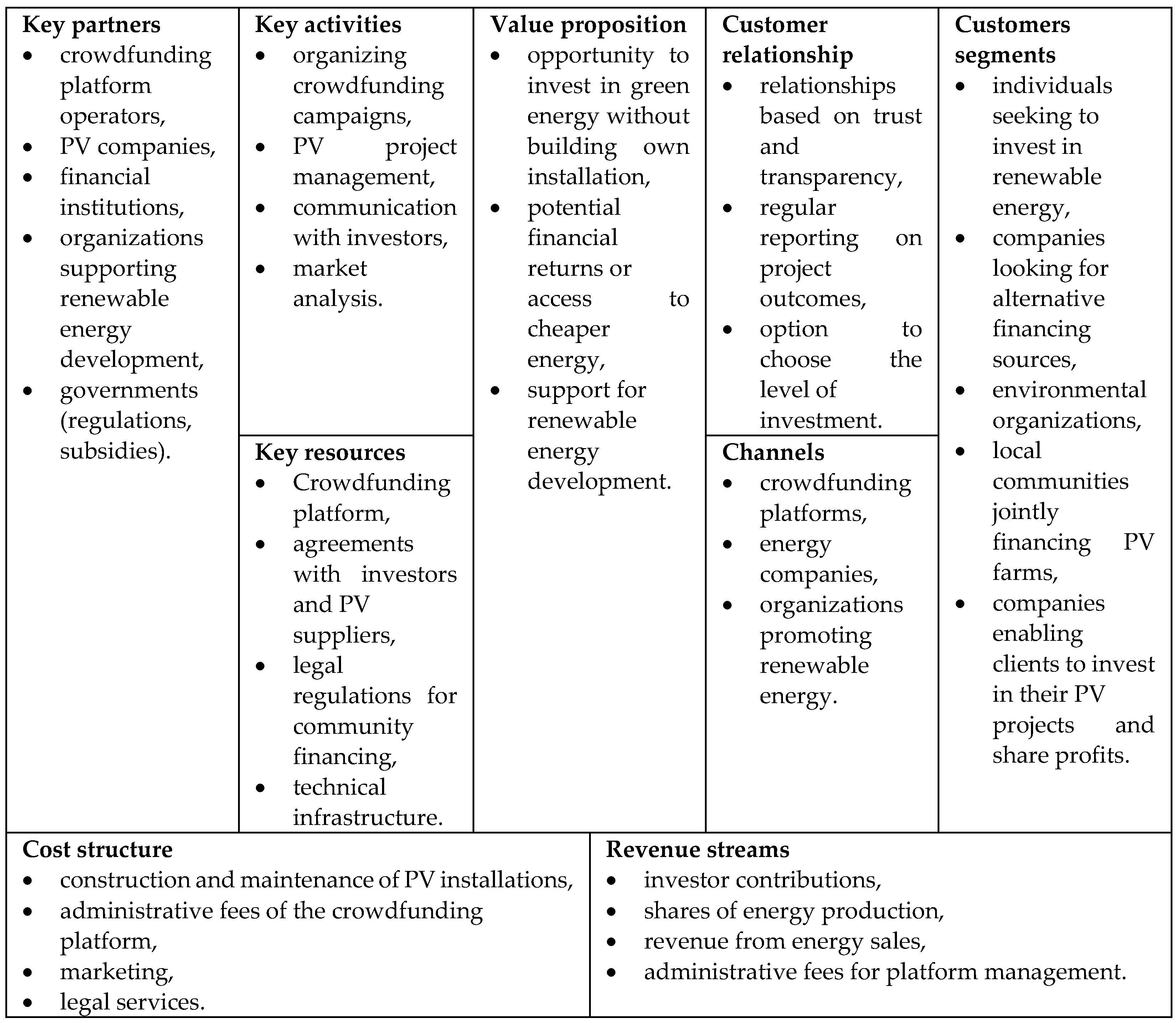

- Crowdfunding is an innovative financing model that enables the implementation of photovoltaic (PV) projects without the involvement of large investors. Funding for PV installations is collected from numerous smaller investors, including both individuals and companies, who wish to support the development of green energy and benefit from their participation. In return for their investment, participants may receive shares in the project, regular returns from the energy produced, or access to lower-cost electricity. Crowdfunding enhances the accessibility of renewable energy projects and allows even large-scale initiatives to be realized without requiring substantial capital contributions from a single investor. This model accelerates the energy transition and provides a mechanism for broad participation in building a sustainable energy future. It is particularly popular among local communities jointly financing PV farms and among companies offering clients the opportunity to invest in their PV projects and share in the profits. Crowdfunding funds dedicated to green energy aggregate capital for innovative renewable energy projects, facilitating wider adoption of sustainable technologies. As a result, crowdfunding not only democratizes access to renewable energy investments but also stimulates innovation by directing capital toward emerging technologies and unconventional business concepts. This model further strengthens public engagement in the energy transition, fostering a sense of ownership and shared responsibility for sustainable development [14,26].

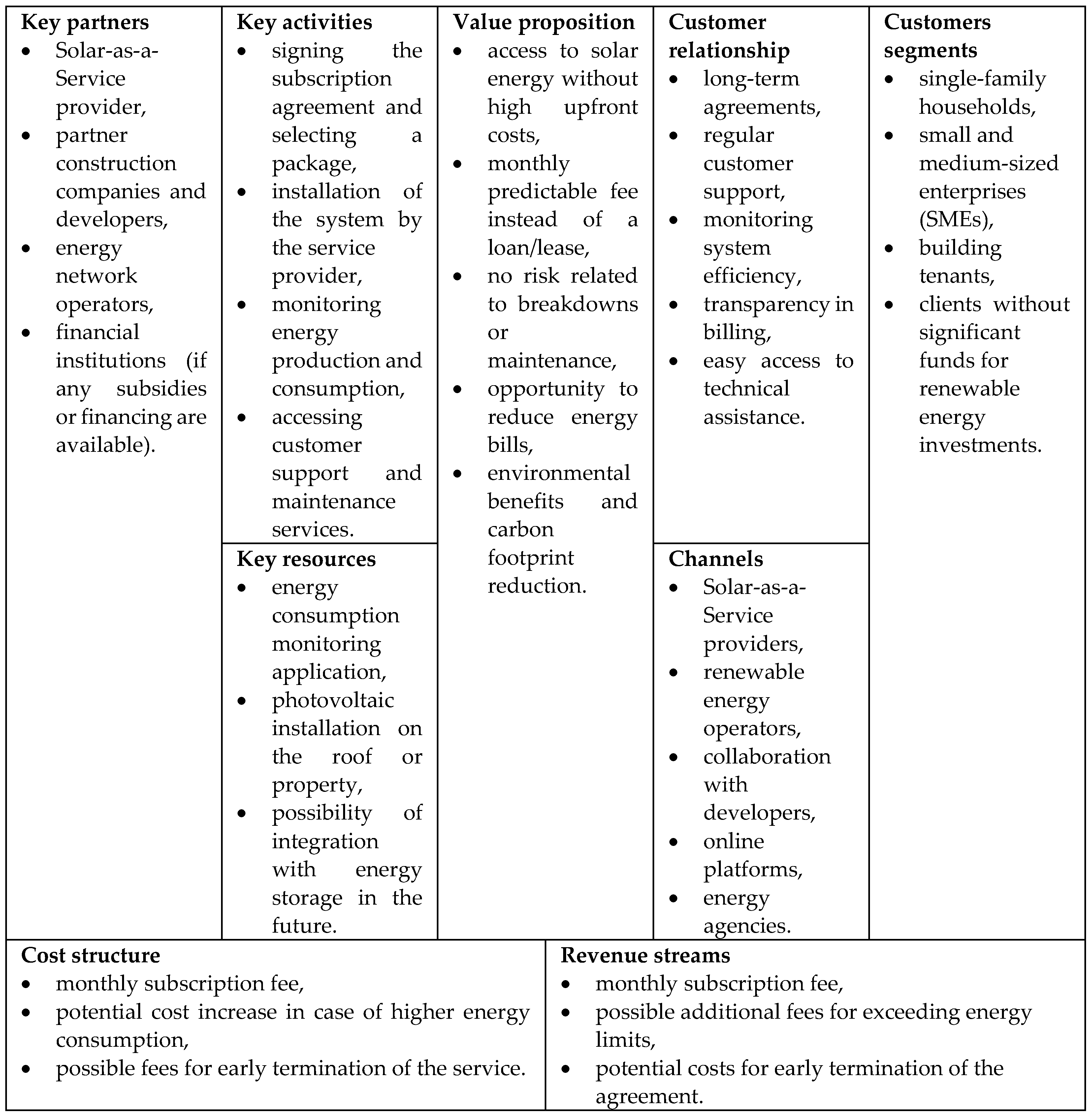

- The subscription model, also referred to as Solar-as-a-Service, is a modern solution that allows users to access solar energy without incurring significant capital investment costs. In this model, the client does not purchase a PV system but pays a monthly subscription for access to the energy generated by panels installed and maintained by the service provider. This arrangement enables users to benefit from renewable energy without concerns related to purchase, installation, or maintenance of the PV system, the service provider assumes full responsibility for system operation. It is an ideal solution for those who wish to utilize renewable energy but are not ready for large investments or long-term financial commitments. The Solar-as-a-Service model provides a convenient and flexible option for accessing green energy without financial risk or the obligations associated with owning a PV installation. It is frequently chosen by single-family households, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and tenants of commercial or residential buildings. In this way, the subscription model significantly lowers the entry barrier to renewable energy adoption, offering a predictable and user-friendly alternative to traditional investment-based approaches. Its flexibility and minimal risk contribute to the broader diffusion of PV technologies, particularly among users seeking simplicity, stability, and immediate access to sustainable energy [2,27].

2.3. Gaps in Current Research

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

- no long-term obligations,

- full control over the installation,

- no subscription fees,

- return on investment after several years,

- highest profitability in the long term,

- direct ability to optimize and upgrade the system according to technological advances,

- full independence from third-party providers, allowing for flexible energy strategies.

- high initial cost,

- requirement for self-maintenance,

- exposure to technical risks, such as panel degradation or unforeseen repair costs,

- investment attractiveness may depend on regulatory incentives or subsidies,

- potential challenges in scaling for larger operations or multi-site enterprises.

- no need for a large initial investment,

- maintenance is the responsibility of the lessor,

- the system can either become the property of the lessee or return to the leasing company at the end of the contract,

- predictable monthly costs, which simplify budgeting for companies and households,

- lower risk exposure to technical failures or unexpected repair costs,

- flexibility to upgrade the PV system with new technology during or at the end of the lease term.

- the total cost of the system is higher than in the ownership model,

- lower profitability compared to the ownership model,

- long-term obligations,

- lower cost-effectiveness in the long term,

- limited control over system customization or operational decisions,

- dependency on the lessor for maintenance quality and response times.

- stable energy price,

- no need to invest in own infrastructure,

- no initial costs,

- predictable energy expenses,

- flexibility,

- access to large-scale PV installations that may be otherwise unaffordable,

- reduced operational and maintenance responsibility, as these are handled by the provider,

- potential for sustainability certification or reporting benefits for the client.

- long-term commitments (e.g., 15–25 years),

- no ownership of the PV system,

- dependence on the energy provider,

- limited control over system upgrades or technology choices,

- potential exposure to provider financial instability or contract renegotiation risks.

- reduction in energy costs,

- independence from large energy corporations,

- democratization of the energy market,

- promotion of sustainable development,

- stronger community engagement and social cohesion,

- opportunity to optimize energy locally and reduce grid losses,

- flexibility in scaling and integrating new participants.

- legal and technical challenges,

- lack of uniform regulations across countries,

- requirement for extensive digital infrastructure,

- reliance on active participation and trust among community members,

- potential complexity in accounting and billing energy exchanges,

- vulnerability to regulatory changes or local policy restrictions.

- accessibility for a wide range of investors,

- support for renewable energy development without large capital expenditures,

- democratization of access to renewable energy investments,

- no need to commit substantial own funds,

- long-term financial benefits,

- promotion of sustainable development,

- encourages community participation and awareness of renewable energy,

- enables financing of larger projects that individual investors could not support alone,

- flexibility in choosing investment level.

- investment risk,

- dependence on the number of investors,

- dependence on participant numbers and energy production outcomes,

- risk of return on investment,

- dependence on legal regulations,

- requires strong project management and communication with investors,

- potential delays or underperformance due to technical or operational challenges,

- limited control for individual investors over project decisions.

- No need for significant upfront investment;

- Minimal risk;

- Low entry threshold;

- Flexibility;

- No financial risk associated with system ownership;

- Predictable costs;

- Full technical service provided by the supplier;

- Easy access to renewable energy;

- Quick deployment without installation concerns for the client;

- Suitable for tenants or clients unable to modify property;

- Allows integration with future storage or energy management solutions.

- Long-term financial commitments in the form of monthly payments.

- No ownership of the PV system.

- Total energy cost may be higher over the long term.

- Dependence on provider reliability and service quality.

- Limited control over energy production or system upgrades.

- Potential constraints in contract terms or package options.

- Households tend to prefer the ownership or subscription model if they lack the capital for a full investment.

- Companies often opt for leasing or PPA models to avoid high upfront costs.

- Industry and large enterprises utilize PPAs to secure stable energy costs.

- Energy communities choose P2P and cooperative models, as well as crowdfunding, to increase independence from large energy providers.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of All Models

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions of Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, G.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y. Research on Decision-Making for a Photovoltaic Power Generation Business Model under Integrated Energy Services. Energies 2022, 15, 5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffenegger, R.; Boukhatmi, Ä.; Bocken, N.; Grösser, S. Product-service-system business models in the photovoltaic industry—A comprehensive analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 505, 145428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankel, A.; Mignon, I. Solar business models from a firm perspective—An empirical study of the Swedish market. Energy Policy 2022, 166, 113013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejun, M. Zarządzanie innowacjami ekologicznymi we współczesnym przedsiębiorstwie [Managing ecological innovations in a modern enterprise]. In Rozwój Zrównoważony—Zarządzanie Innowacjami Ekologicznymi [Sustainable Development—Managing Ecological Innovations]; Matejun, M., Grądzki, R., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Media Press: Warszawa, Poland, 2009; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Robakiewicz, M. Audyty Efektywności Energetycznej i Audyty Energetyczne Przedsiębiorstw [Energy Efficiency Audits and Corporate Energy Audits], 2nd ed.; Fundacji Poszanowania Energii: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; pp. 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 50001:2018/Amd 1:2024; Energy Management Systems — Requirements with Guidance for Use — Amendment 1: Climate Action Changes. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Singh, R.K.; Kumar Mangla, S.; Bhatia, M.S.; Luthra, S. Integration of green and lean practices for sustainable business management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Mohanta, A. Energy Management Systems in the Context of Sustainable Business Practices. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2025, 5, e06600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britel, Z.; Cherkaoui, A. Development of a readiness for change maturity model: An energy management system implementation case study. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2022, 28, 93–109. Available online: https://reference-global.com/article/10.30657/pea.2022.28.11?tab=preview (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gabrielyan, B.; Markosyan, A.; Almastyan, N.; Madoyan, D. Energy efficiency in household sector. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2024, 30, 136–144. Available online: https://reference-global.com/article/10.30657/pea.2024.30.13 (accessed on 20 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mazur, M.; Fedorchuk, S.; Kulapin, O.; Ivakhnov, A.; Danylchenko, D.; Miroshnyk, O.; Shchur, T.; Halko, S.; Idzikowski, A. Analysis of the required energy storage capacity for balancing the load schedule and managing the electric energy demand of an apartment building. Syst. Saf. Hum. Tech. Facil. Environ. 2023, 5, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orłowska, J.; Suchacka, M.; Trembaczowski, Ł.; Ulewicz, R. Social Aspects of Establishing Energy Cooperatives. Energies 2024, 17, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.; da Silva, H.B.; Thakur, J.; Uturbey, W.; Thakur, P. Categorizing shared photovoltaic business models in renewable markets: An approach based on CANVAS and transaction costs. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 1602–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chang, R.; Lim, S. Crowdfunding for solar photovoltaics development: A review and forecast. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, P.; Čvirik, M.; Maciejewski, G.; Žambochová, M.; Kitová Mazalánová, V. Activities of retail units as an element of business model creation. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 27, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijben, J.C.C.M. Mainstreaming Solar: PV Business Model Design Under Shifting Regulatory Regimes. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2015. Available online: https://pure.tue.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/87285414/20171201_Huijben.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Zhang, S. Innovative business models and financing mechanisms for distributed solar PV (DSPV) deployment in China. Energy Policy 2016, 95, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwińska, K.; Pacana, A. Analysis of Energy Security Based on Level of Alignment with the Goals of Agenda 2030. Energies 2024, 17, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyanti, R.; Włodarczyk, A. Environmental strategies of energy companies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 28, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipiak, M.; Nawrowski, R.; Kurz, D.; Pierzchała, R. Analiza opłacalności stosowania instalacji fotowoltaicznej we współpracy z magazynem energii dla domu jednorodzinnego. [Analysis of the profitability of using a photovoltaic installation in cooperation with an energy storage for a single-family home]. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2022, 98, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Znajdek, K.; Sibiński, M. Postępy w Fotowoltaice. Struktura i Wytwarzanie Ogniw PV. Projektowanie i Zastosowania Systemów Fotowoltaicznych. Klasyczne i Nowatorskie Ogniwa w Praktyce; Polskie Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, C.; Bucksteeg, M.; Staudt, P. Review and morphological analysis of renewable power purchasing agreement types. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 211, 115293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.; Carriveau, R.; Harper, S.; Singh, S. Evaluating the link between LCOE and PPA elements and structure for wind energy. Energy Strategy Rev. 2017, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Exploring structures of power purchase agreements towards supplying 24x7 variable renewable electricity. Energy 2022, 244, 122609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourcet, C.; Bovari, E. Exploring citizens’ decision to crowdfund renewable energy projects: Quantitative evidence from France. Energy Econ. 2020, 88, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menyeh, B.O.; Acheampong, T. Crowdfunding renewable energy investments: Investor perceptions and decision-making factors in an emerging market. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 114, 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rojo, C.; Gallego-Nicholls, J.F.; Rey-Martí, A. Understanding investor behavior in crowdfunding for sustainability: An FsQCA study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.A.; Groesser, S.N. A Systematic Literature Review of the Solar Photovoltaic Value Chain for a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strupeit, L.; Bocken, N.; Van Opstal, W. Towards a Circular Solar Power Sector: Experience with a Support Framework for Business Model Innovation. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 2093–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, S.R.; Juntunen, J.K.; Rajala, A. Business models for enhanced solar photovoltaic (PV) adoption: Transforming customer interaction and engagement practices. Sol. Energy 2024, 268, 112324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radl, J.; Fleischhacker, A.; Revheim, F.H.; Lettner, G.; Auer, H. Comparison of Profitability of PV Electricity Sharing in Renewable Energy Communities in Selected European Countries. Energies 2020, 13, 5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trimi, S.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J. Business model innovation in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 8, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEAN Foundry; Maurya, A. Why Lean Canvas vs Business Model Canvas? Practice Trumps Theory. Available online: https://www.atlassian.com/work-management/project-management/business-model-canvas (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Avdiji, H.; Elikan, D.; Missonier, S.; Pigneur, Y. Designing tools for collectively solving III-structured problems. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Generaci’ on de Modelos de Negocios; DEUSTO: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ingaldi, M.; Ulewicz, R. The Business Model of a Circular Economy in the Innovation and Improvement of Metal Processing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Leasing | PPA | P2P | Crowdfunding | Subscription | |

| Initial investment | Very high | Low | None | Medium (shared) | None/small | None |

| Long-term costs | Lowest | Medium | Medium | Low–medium | Depends on project | Higher (subscription) |

| Financial risk | High (investment, maintenance) | Low–medium | Low | Medium (market/regulatory, platform) | High (investment risk, production uncertainty) | Very low |

| Ownership of installation | Yes | No (possible buyout) | No | Collective/shared | No | No |

| Energy price stability | Medium (market tariffs) | Medium | High (fixed PPA tariff) | Medium | Depends on project | Medium |

| Independence from grid | Medium–high | Medium | Low–medium | High | Low | Low |

| Customer profile | Households, SMEs | SMEs, logistics, households with limited capital | Large companies, industry | Local communities, cooperatives, neighborhoods | Investors, communities | Households, SMEs, tenants |

| Scalability | Limited | Good | Very high | Medium | High (many small investors) | High |

| Advantages | Full control, long-term savings | No upfront cost, service included | Predictable costs, no investment | Energy sharing, prosumer empowerment, decentralization | Democratization of financing, low entry threshold, long-term financial benefits | Flexibility, zero investment, low risk, minimal operational involvement, technical service included, easy integration with energy storage |

| Limitations | High initial costs | Higher total cost | Long-term contracts | Regulatory/technical barriers, digital infrastructure required | Investment risk, dependent on number of participants and production outcomes, legal/regulatory uncertainty | No ownership, long-term payment obligation, dependent on service provider quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazur, M.; Ingaldi, M. Strategies for Solar Energy Utilization in Businesses: A Business Model Canvas Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 6533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246533

Mazur M, Ingaldi M. Strategies for Solar Energy Utilization in Businesses: A Business Model Canvas Approach. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246533

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazur, Magdalena, and Manuela Ingaldi. 2025. "Strategies for Solar Energy Utilization in Businesses: A Business Model Canvas Approach" Energies 18, no. 24: 6533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246533

APA StyleMazur, M., & Ingaldi, M. (2025). Strategies for Solar Energy Utilization in Businesses: A Business Model Canvas Approach. Energies, 18(24), 6533. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246533