1. Introduction

Wind power, as a cornerstone of the global energy transition, poses significant challenges to grid stability due to its inherent intermittency and volatility. High-accuracy wind power forecasting has become a critical enabler for ensuring grid security and cost-effective dispatch, playing an indispensable role in reducing spinning reserve requirements and enhancing the operational efficiency of wind farms [

1]. Over the past five years, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence has driven a paradigm shift in wind power prediction—from traditional physical and statistical models toward machine learning and deep learning approaches [

2]. According to the 2023 annual report from the International Energy Agency (IEA), global installed wind capacity is projected to reach 1200 GW by 2025; however, this green energy prospect faces serious grid integration challenges unless forecasting accuracy bottlenecks are effectively addressed [

3].

Early-stage research primarily relies on numerical weather prediction (NWP) systems and physical modeling approaches, which require substantial support from supercomputing resources due to their foundation in atmospheric physical equations [

4]. While physical methods effectively capture large-scale meteorological patterns, their accuracy in predicting microclimates at the wind turbine hub height remains limited, particularly under complex terrain conditions.

With the emergence of machine learning techniques, support vector machines (SVMs) [

5] and random forests (RFs) achieve superior prediction accuracy compared to traditional statistical methods by employing feature engineering to extract key influencing factors of wind resources. The multi-output support vector machine (MSVM) prediction framework proposed by Lu et al. [

6] corporates Pearson’s correlation coefficients and partial autocorrelation functions during the data analysis phase to examine the spatiotemporal correlations of wind power. Experimental results across 15 wind farm datasets demonstrate that the MSVM framework outperforms other benchmark models in forecasting performance. Zhang et al. [

7] propose a semi-supervised learning approach utilizing least squares support vector machines for wind power data, showing certain effectiveness when applied to spatially dynamic wind power datasets. Research by Chaudhary et al. [

8] indicates that random forest models incorporating feature importance analysis provide satisfactory forecasting precision for wind speed prediction. However, these methods generally require sophisticated feature engineering and exhibit high dependency on data quality, where outliers and missing values can significantly compromise model performance.

The advent of deep learning methods has brought transformative breakthroughs to wind power forecasting. Long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [

9] and gated recurrent units (GRUs) [

10] demonstrate exceptional capability in learning temporal dependencies, establishing themselves as powerful tools for time series prediction. Wang et al. [

11] developed a novel genetic long short-term memory (GLSTM) framework that improves forecasting accuracy by 6% to 30% through integrated analysis of multiple meteorological factors including wind speed, wind direction, and temperature. Liu et al. [

12] proposed an innovative prediction model that captures evolving multi-scale variable relationships and temporal dependencies. Their approaches employ multi-scale temporal graph neural networks with adaptive graph learning modules to extract features from high-frequency information, while utilizing enhanced bidirectional temporal networks for low-frequency data characterization. This architecture achieves a 48.9% reduction in mean square error compared to standalone LSTM models. Hybrid architectures combining convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with LSTM further enhance spatiotemporal feature extraction capabilities. Wu et al. [

13] introduce a spatiotemporal correlation model (STCM) based on CNN-LSTM for ultra-short-term forecasting. In this framework, CNN extracts spatial correlation features from meteorological factors across different sites and temporal correlation vectors from short-term meteorological characteristics, while LSTM captures complex temporal dependencies. Evaluations across multiple wind farm datasets demonstrate that the CNN-LSTM-based STCM exhibits superior spatiotemporal feature extraction capacity and generates more accurate wind power predictions compared to conventional architectures. Adam Kisvari et al. [

14] pioneered the comprehensive integration of gated recurrent deep learning models with data preprocessing techniques, including resampling, anomaly detection and processing, feature engineering, and hyperparameter optimization. Their experimental results consistently show that GRU outperforms LSTM in prediction accuracy across all evaluation scenarios. Chen et al. [

15] developed an ultra-short-term forecasting methodology utilizing multi-layer bidirectional GRU (Bi-GRU) and fully connected (FC) layers, where Bi-GRU extracts temporal features from wind power and meteorological data, and FC layers perform dimension transformation to align with output vectors. Experimental validation confirms the superior predictive performance of this approach. Xu et al. [

16] enhance feature capture capability by integrating GRU with a feature attention mechanism (FAM) to extract relevant patterns from historical wind power data and meteorological information, further advancing the state of feature representation in wind power forecasting.

Hybrid deep learning architectures represent the current technological frontier in wind power forecasting, particularly through methodologies that employ signal decomposition techniques—such as variational mode decomposition (VMD) and empirical mode decomposition (EMD)—to mitigate the non-stationarity of raw wind speed sequences, followed by deep learning models for prediction. Yu et al. [

17] proposed an RF-VMD-BiGRU learning framework, which first employs random forest (RF) to screen feature factors in wind power data, thereby reducing low-correlation features. Subsequently, VMD adaptively decomposes the original wind power sequence to diminish data noise. Finally, a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) is applied for prediction, demonstrating significant effectiveness. Following this, Cui et al. [

18] and Zhang et al. [

19] introduce an attention mechanism (AM) into the BiGRU architecture to assign adaptive weights, enabling dynamic capture of wind power sequence characteristics and achieving improved short-term forecasting performance. Duan et al. [

20] developed a hybrid forecasting model incorporating a decomposition strategy, nonlinear weighted combination, and two deep learning models. In this approach, sequences decomposed by VMD are fed into sub-models constructed using long short-term memory (LSTM) and particle swarm optimization-optimized deep belief network (PSO-DBN). This design overcomes the limitations of linear combination methods and further enhances the accuracy and stability of wind power forecasting.

In recent years, the random vector functional link (RVFL) network has been introduced into the wind power forecasting field due to its unique mechanism of “random weight fixation and analytical solution.” Its primary advantages include extremely fast training speed, an ability to efficiently capture nonlinear relationships between wind speed and power output, and reduced susceptibility to overfitting. This model effectively balances prediction accuracy with computational efficiency, providing reliable support for efficient short-term power forecasting and dispatch management in wind farms. Mohammed et al. [

21] proposed using RVFL for predicting wind turbine generation data and employed a capuchin search algorithm to optimize the configuration of traditional RVFL, thereby enhancing its predictive capability. Song et al. [

22] developed a method that dynamically generates hidden nodes in the RVFL to adapt to new training samples and determines the optimal number of synthetic samples based on validation performance. Their approach also connects historical and newly added nodes to mitigate the forgetting of historical information. By fully capturing the characteristics of wind power data, this method effectively resolves the uncertainty associated with synthetic sample quantity under few-shot learning conditions.

In addition to decomposition–learning hybrids, neuro-fuzzy estimation schemes have also been explored for wind-turbine diagnosis and monitoring. For instance, neuro-fuzzy qLPV zonotopic observers have been employed to estimate turbine states under model uncertainty [

23], while ANFIS-based Takagi–Sugeno interval observers have been used for fault diagnosis and robust condition monitoring of wind turbines [

24]. These approaches combine fuzzy inference with neural network approximators to handle nonlinearities and bounded disturbances. However, they primarily focus on fault detection and health assessment, rather than short-term forecasting of non-stationary wind power signals. The proposed VMD-IPCA-IHSO-FSRVFL framework is complementary to these neuro-fuzzy strategies by targeting high-accuracy wind power prediction under strongly time-varying operating conditions.

Table 1 lists the main abbreviations used in this study.

Based on the comprehensive research content presented in the second document, the principal contributions and innovations of this study in the field of wind power forecasting are summarized as follows:

- (1)

A hybrid forecasting framework integrating variational mode decomposition (VMD), incremental principal component analysis (IPCA), an improved holistic swarm optimization (IHSO) algorithm, and feature space-regularized random vector functional link (FSRVFL) networks is proposed. This ensemble model effectively captures both temporal dependencies and complex nonlinear relationships within wind power data, significantly enhancing prediction accuracy under varying seasonal conditions.

- (2)

The variational mode decomposition (VMD) technique is employed to adaptively decompose non-stationary environmental sequences—such as wind speed, temperature, and irradiation—into a set of more stable and regular intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). This process effectively extracts multi-scale temporal features from the original data, thereby improving the model’s ability to characterize complex wind power patterns.

- (3)

Incremental principal component analysis (IPCA) is utilized for feature selection to eliminate noise and reduce redundancy among the high-dimensional features generated by decomposition. By identifying and retaining the most relevant features, this study streamlines the model input, decreases computational complexity, and enhances the robustness of the forecasting system.

- (4)

An improved holistic swarm optimization (IHSO) algorithm is introduced to optimize the hyperparameters of the FSRVFL model. Enhancements including logistic chaotic mapping, Lévy flight strategies, and simulated annealing mechanisms are incorporated to accelerate convergence speed, strengthen global search capability, and prevent premature convergence to local optima.

- (5)

A semi-supervised learning architecture, the feature space-regularized random vector functional link (FSRVFL) network, is developed. By integrating manifold regularization from multiple feature spaces, the model effectively leverages information from both labeled and unlabeled data, substantially improving generalization performance and prediction stability for wind power generation.

At the end of this section, the overall organization of the paper is outlined.

Section 2 introduces the methodological background, including variational mode decomposition (VMD), incremental principal component analysis (IPCA), the improved holistic swarm optimization (IHSO) algorithm, and the feature space-regularized random vector functional link (FSRVFL) network.

Section 3 presents the flowchart of the proposed VMD-IPCA-IHSO-FSRVFL framework and summarizes the main steps of the workflow.

Section 4 describes the case study setup, including the offshore wind farm datasets and data preprocessing procedures.

Section 5 reports the comparative forecasting results, ablation analysis, and computational complexity of different models. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

3. Flowchart of VMD–IPCA–IHSO–FSRVFL Model

In this study, we propose a novel hybrid forecasting framework for wind power prediction, which integrates variational mode decomposition (VMD), incremental principal component analysis (IPCA)-based feature selection, an improved holistic swarm optimization (IHSO) algorithm, and a feature space-regularized random vector functional link (FSRVFL) network. This integrated model, termed VMD-IPCA-IHSO-FSRVFL, is designed to enhance prediction accuracy and robustness by systematically addressing the non-stationarity and complexity inherent in wind power data. The comprehensive architecture of the proposed model is illustrated in

Figure 1 and the procedural workflow is detailed as follows:

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing. Acquire historical wind power generation data and corresponding meteorological variables. The raw data undergoes preprocessing, which includes Z-score standardization to eliminate dimensional discrepancies and an outlier handling procedure to mitigate the impact of anomalous readings, thereby accelerating subsequent model convergence.

Step 2: Signal Decomposition via VMD. Apply VMD to the preprocessed wind power sequence to adaptively decompose it into a set of finite-bandwidth intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). This step effectively disentangles the original non-stationary signal into several relatively stable and regular sub-sequences, capturing multi-scale temporal characteristics and reducing modeling complexity.

Step 3: Feature Selection using IPCA. Compute the mutual information between all potential features (including the original meteorological variables and the derived IMF components from VMD) and the target wind power output. Select the feature subset with the highest mutual information scores. This process reduces data redundancy and noise, retaining the most informative inputs for the prediction model and decreasing computational dimensionality.

Step 4: Hyperparameter Optimization with IHSO. Utilize the IHSO algorithm to optimize the key hyperparameters of the FSRVFL network. The improvements in HSO, which include a dynamic weighting factor, Lévy flight strategy, simulated annealing, and adaptive mutation enhance global search capability and convergence speed, ensuring the FSRVFL model is configured for optimal performance.

Step 5: Prediction with FSRVFL. Construct the FSRVFL predictor using the optimized hyperparameters from Step 4. The selected features from Step 3 are fed into this semi-supervised learning model. The FSRVFL leverages manifold regularization from multiple feature spaces to enhance generalization, producing the final wind power forecasts.

Step 6: Model Validation and Performance Evaluation. Evaluate the forecasting performance of the proposed VMD-IPCA-IHSO-FSRVFL model on the testing dataset using established metrics, including mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination (R2). Compare its results against those of various benchmark models to demonstrate its superiority.

This structured workflow ensures a coherent integration of signal processing, feature engineering, intelligent optimization, and advanced machine learning, providing a robust and effective solution for wind power forecasting.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a hybrid ensemble learning framework named VMD–IPCA–IHSO–FSRVFL is proposed for wind power forecasting. The model integrates variational mode decomposition (VMD), incremental principal component analysis (IPCA)-based feature selection, an improved holistic swarm optimization (IHSO) algorithm, and a feature space-regularized random vector functional link (FSRVFL) network. By applying VMD to decompose the original non-stationary wind power sequences, applying MI to reduce feature dimensionality and remove redundancy, applying IHSO to optimize the hyperparameters of FSRVFL, and finally employing the FSRVFL network for prediction, the proposed model effectively improves forecasting accuracy and stability.

The main contributions and findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

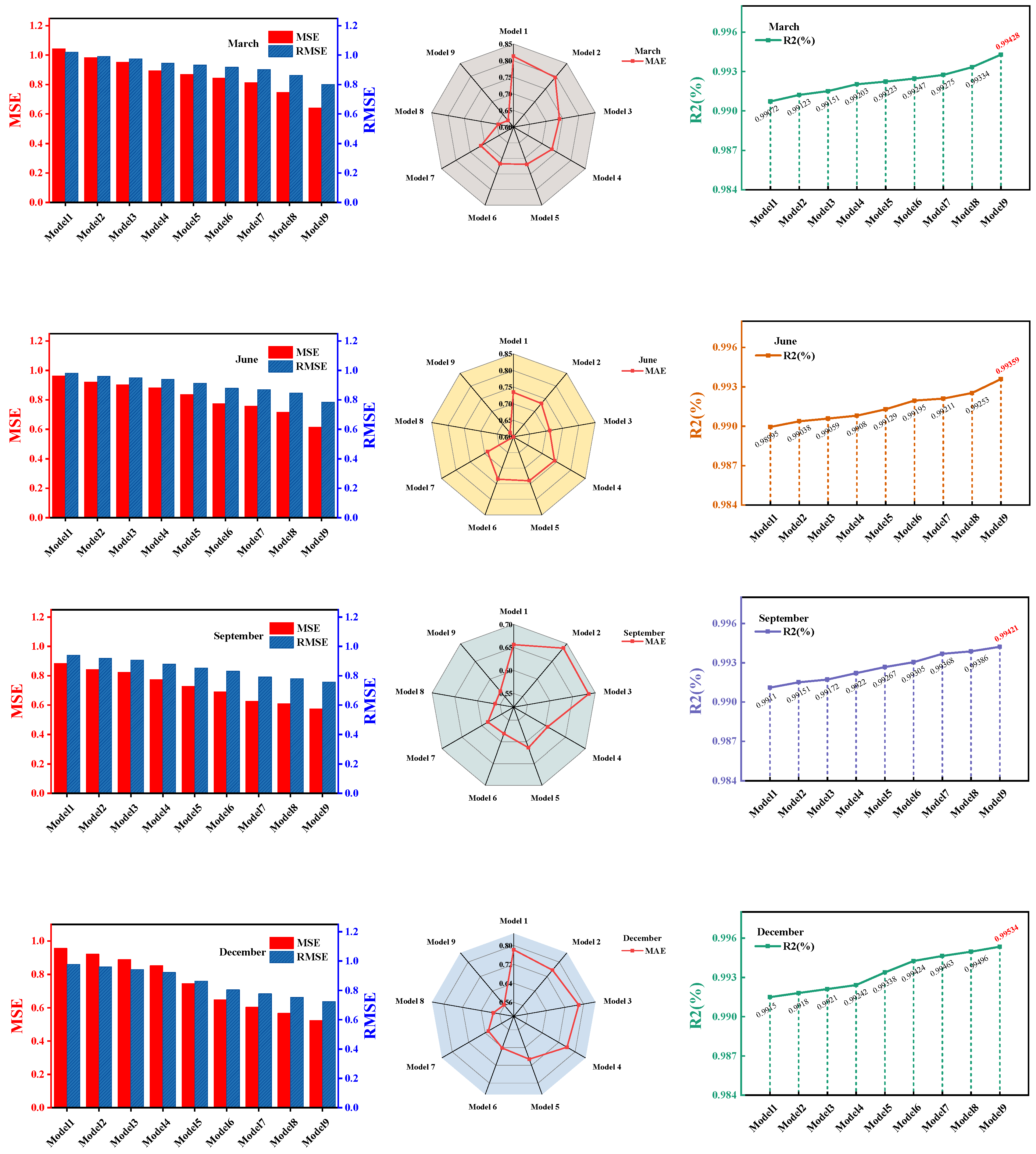

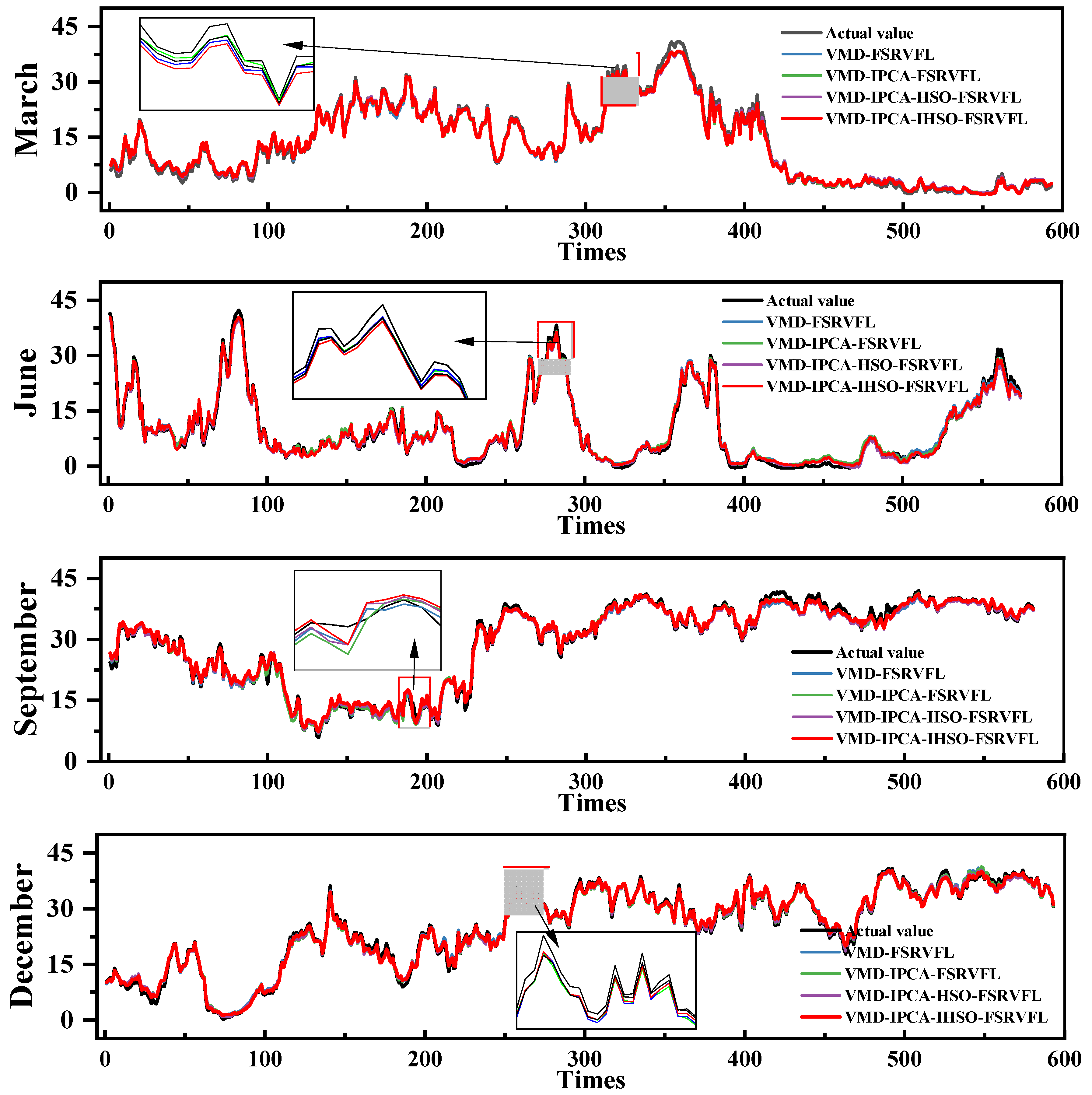

The proposed VMD-IPCA-IHSO-FSRVFL model achieves the smallest MSE, RMSE, and MAE, along with the highest R

2 values, across four seasonal wind power datasets from an offshore wind farm. According to

Table 5, compared with classical neural-network and ensemble baselines such as BP, ELM, and RVFL, the proposed framework reduces MSE by approximately 30–45% and MAE by 15–25% on average over the four months, while consistently increasing R

2 above 99.3%. These quantitative results demonstrate that the hybrid model offers clearly superior estimation capability and stronger generalization performance than both individual benchmark models and intermediate hybrid variants.

- (2)

The integration of VMD and IPCA proves to be an effective strategy for processing non-stationary wind power data. VMD successfully extracts meaningful intrinsic mode components from complex environmental sequences, while IPCA-based dimensionality reduction (guided by mutual-information analysis) efficiently selects the most relevant features, reduces noise, and decreases computational complexity, thereby enhancing the model’s learning efficiency and prediction accuracy.

- (3)

The introduction of the improved holistic swarm optimization (IHSO) algorithm significantly enhances the hyperparameter optimization process for FSRVFL. By incorporating logistic chaotic mapping, adaptive mutation, and a simulated annealing mechanism, IHSO accelerates convergence, avoids local optima, and improves the stability and reliability of the forecasting model.

- (4)

The FSRVFL network serves as a high-performance regression core, combining the efficiency of random vector functional links with dual feature-space manifold regularization. This semi-supervised structure effectively utilizes both labeled and unlabeled data, improving generalization under variable wind conditions.

Despite the promising results, several aspects merit further investigation in future work:

- (1)

The current study focuses on single-step-ahead forecasting. Extending the model to multi-step wind power prediction would be valuable for supporting more advanced grid scheduling and energy management systems.

- (2)

Future research could explore the integration of numerical weather prediction (NWP) data or other atmospheric variables to further enhance the model’s input feature set and its physical interpretability.

- (3)

While the model performs well on data from one wind farm, its generalizability across different geographic and climatic regions should be validated with more diverse datasets.

- (4)

Future work may also consider deploying the model in real-time forecasting systems, possibly incorporating online learning strategies to continuously adapt to changing environmental patterns.

In summary, the VMD–IPCA–IHSO–FSRVFL framework provides an accurate, stable, and efficient solution for wind power forecasting, with robust performance across different seasons and operating conditions. It offers a valuable reference for wind farm operators and power system planners in achieving higher renewable energy integration.