Enhancing Robustness in Photoacoustic Detection of Dissolved Acetylene in Transformer Oil: Temperature Effects on Resonance Frequency and Suppression Using the Perturbation Observation Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

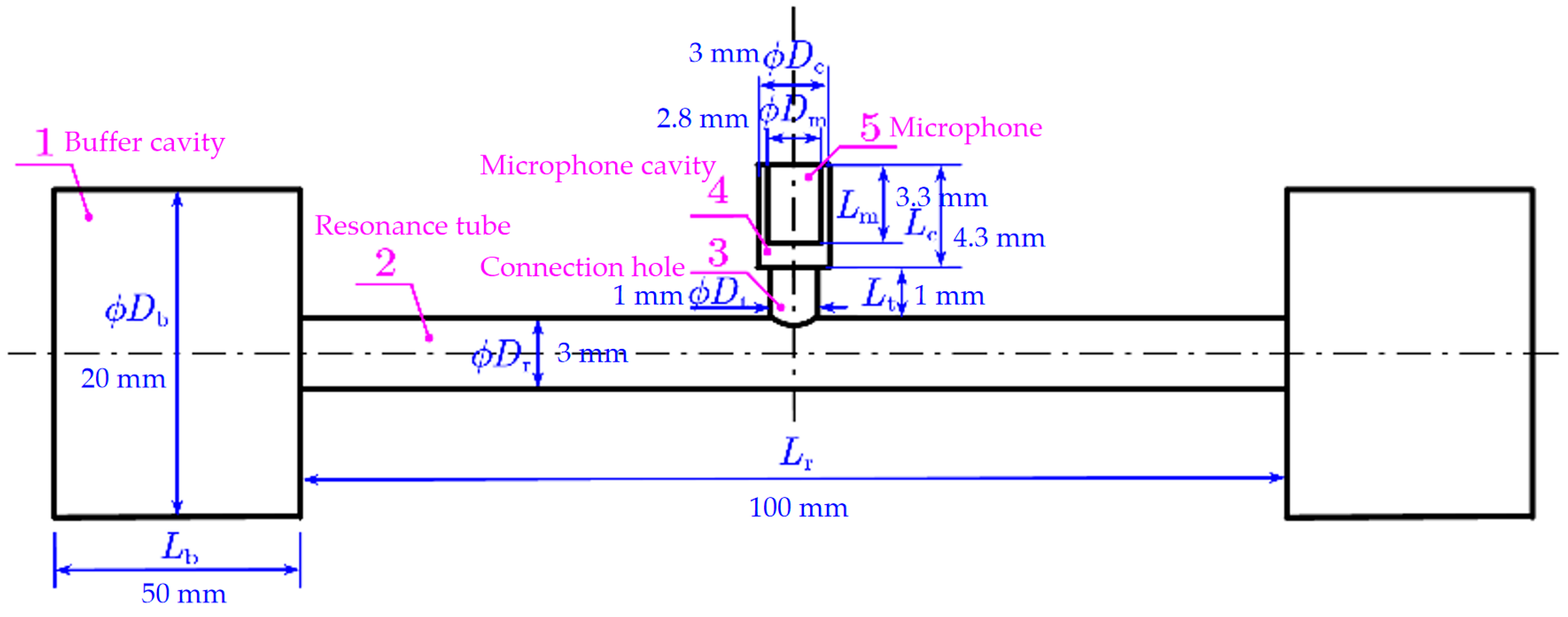

2. Theoretical Analysis and Simulation of Temperature Effects on Resonance Frequency

2.1. Temperature Effects on Resonance Frequency

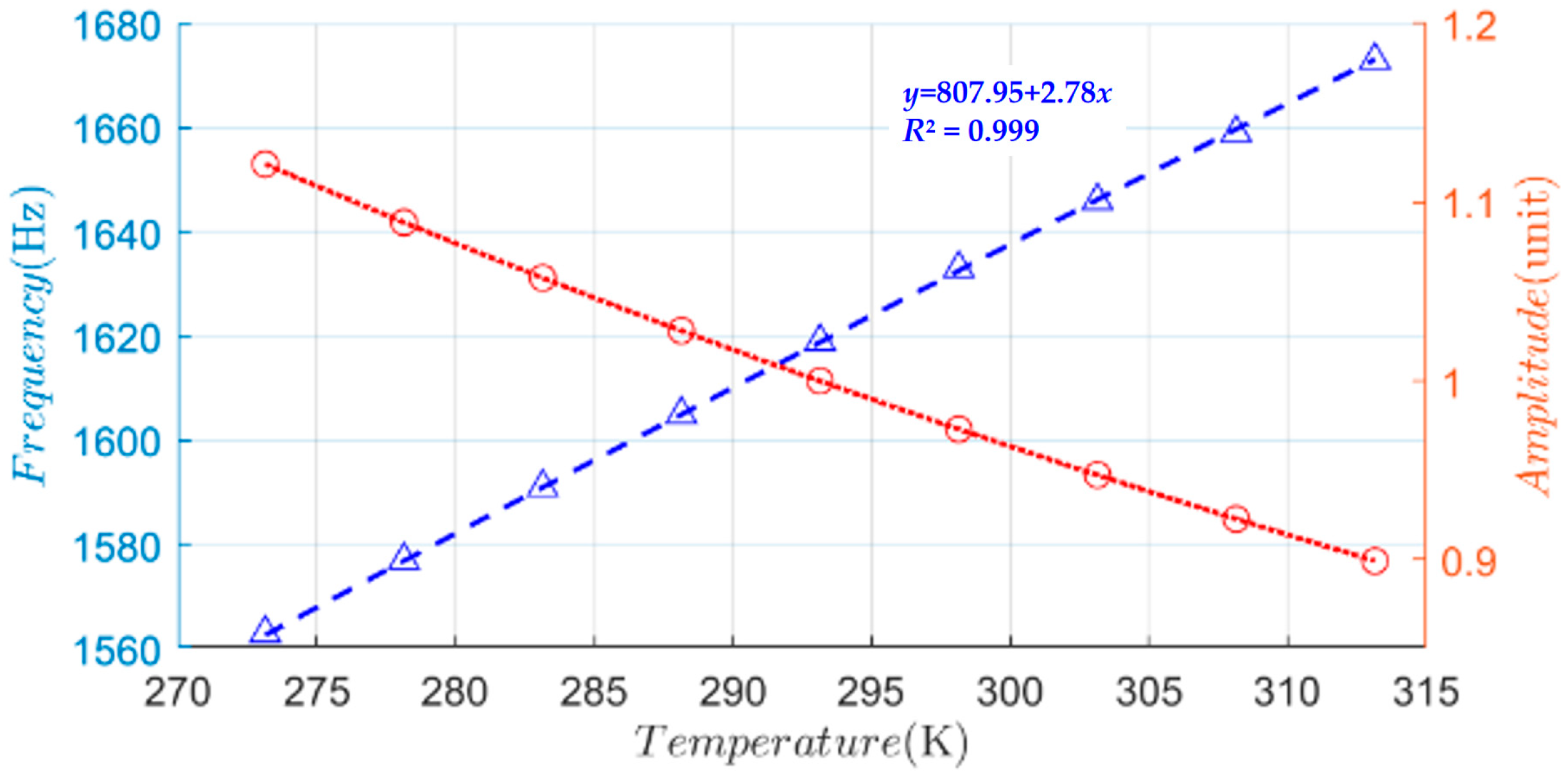

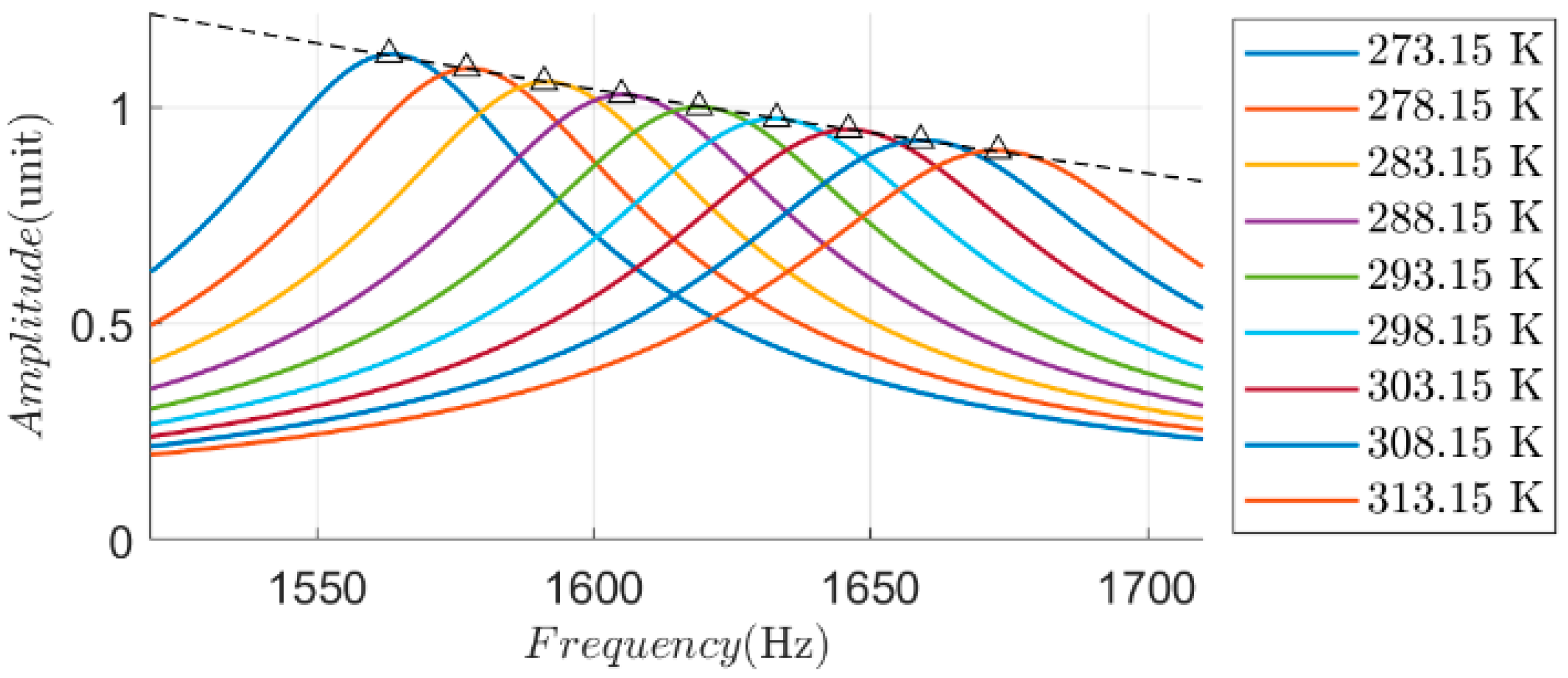

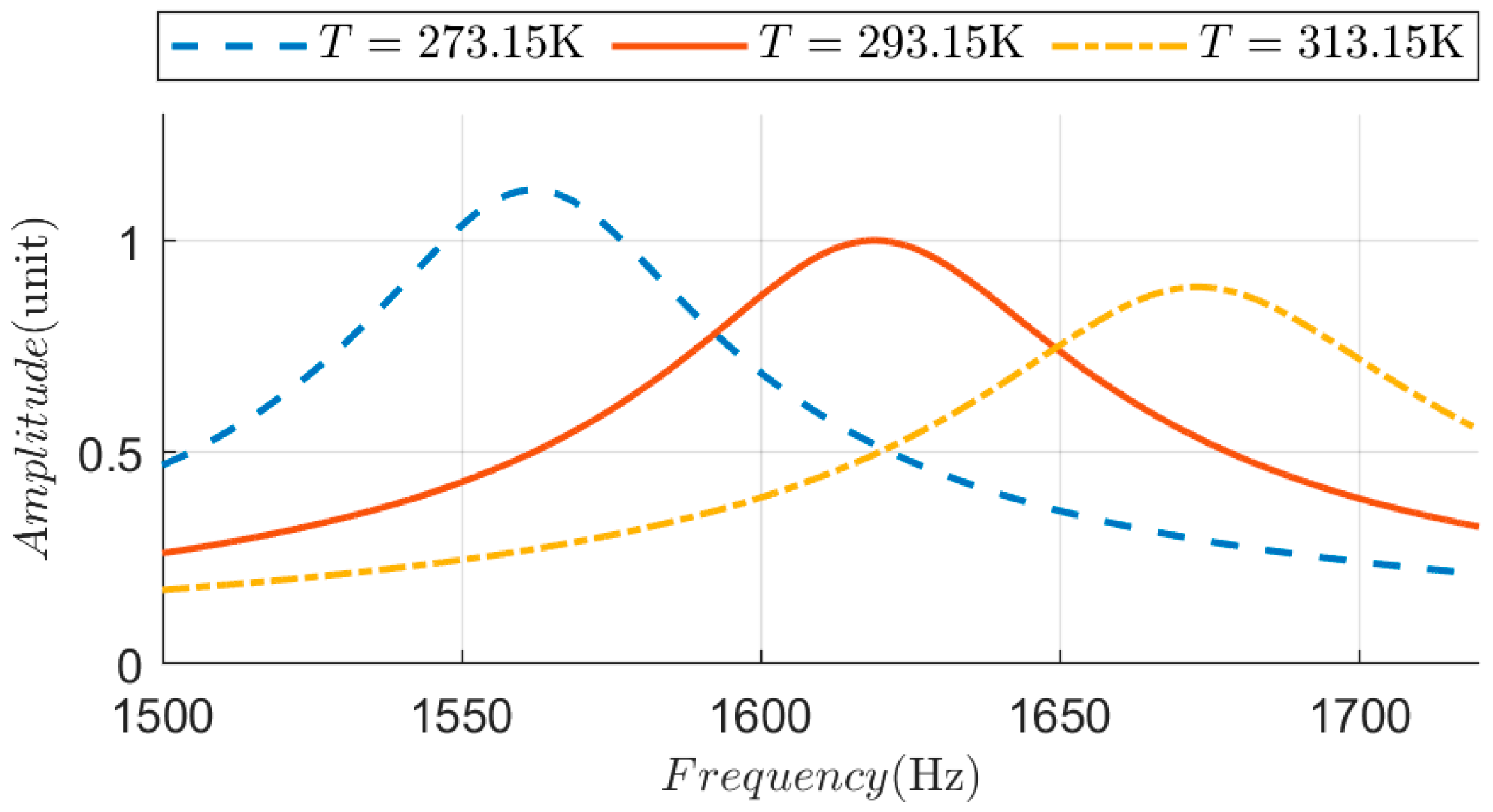

2.2. Simulation of Temperature Effects

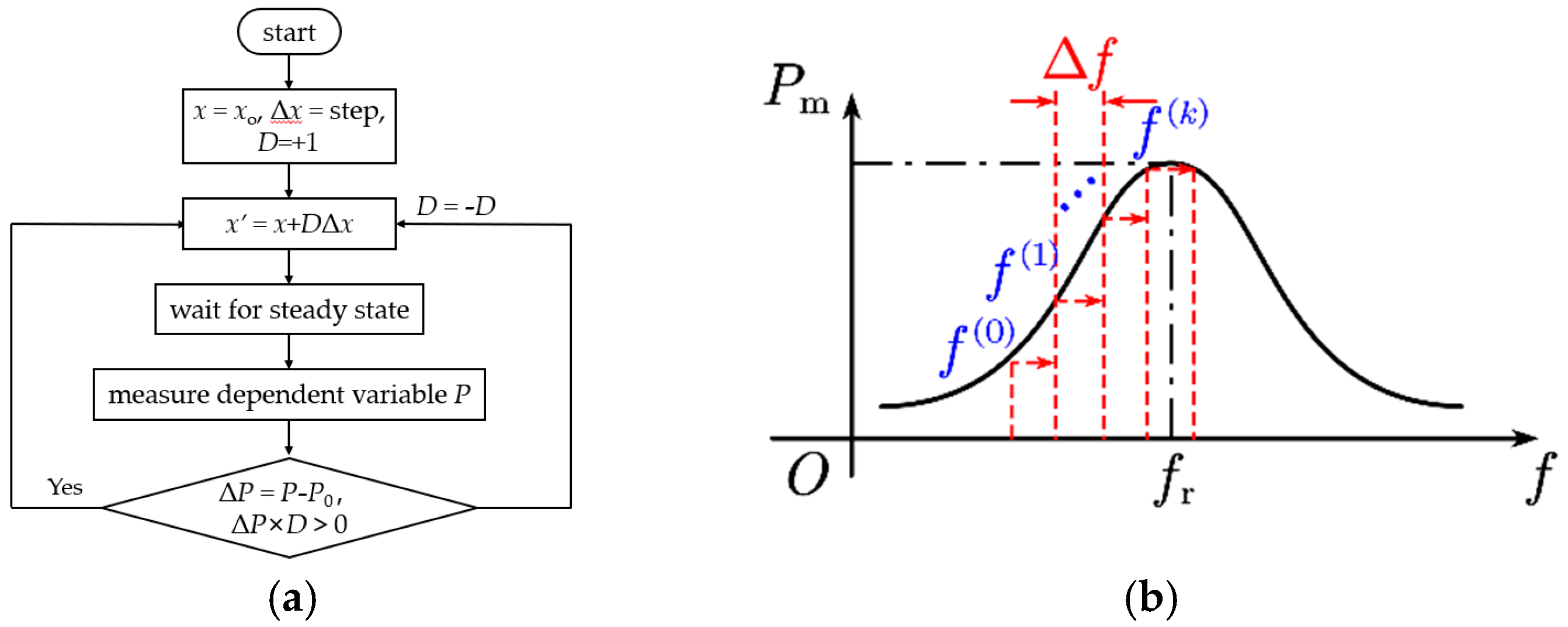

3. Perturbation-Observation Suppression Method

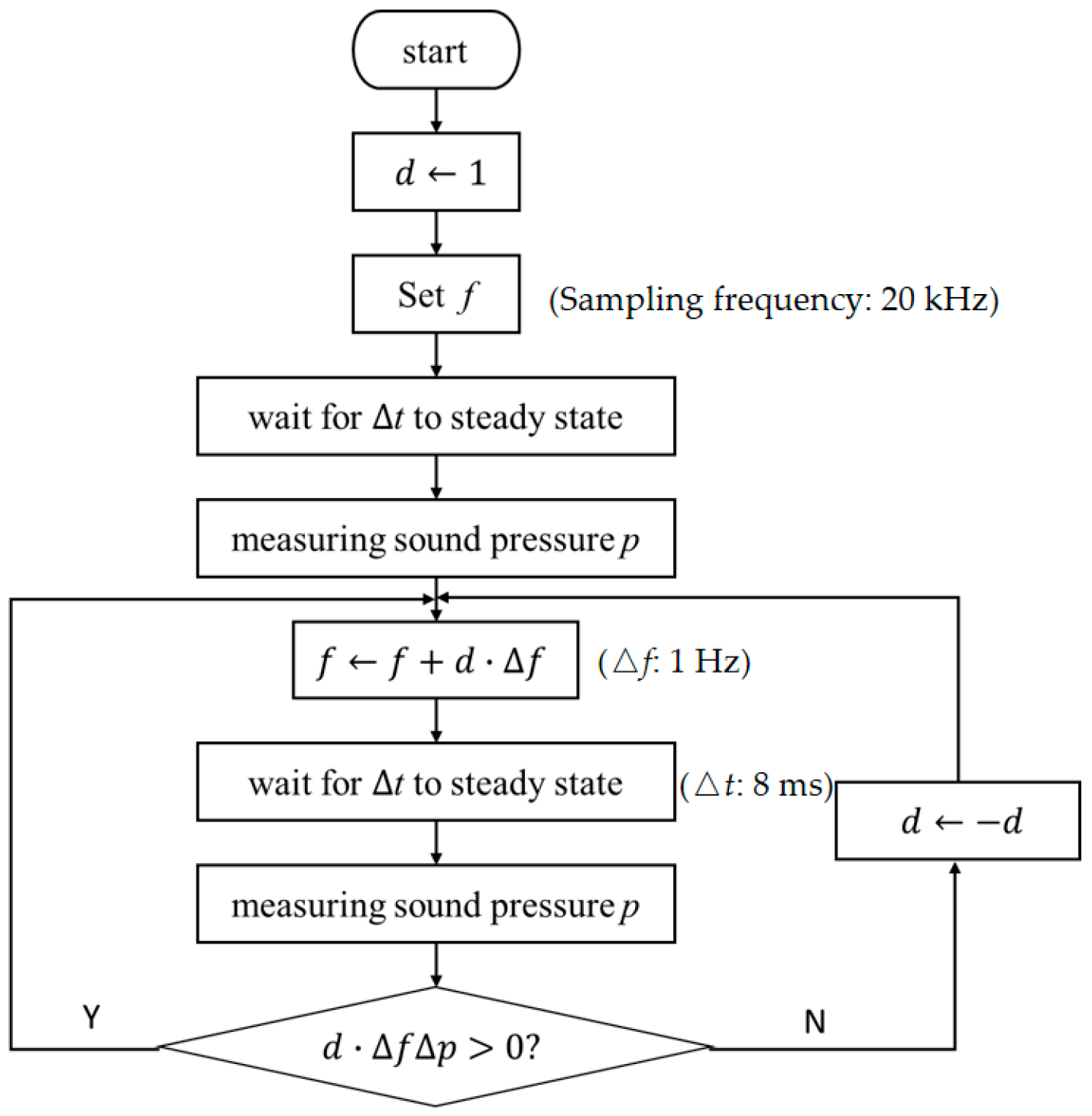

3.1. Principle of the Perturbation Observation Method

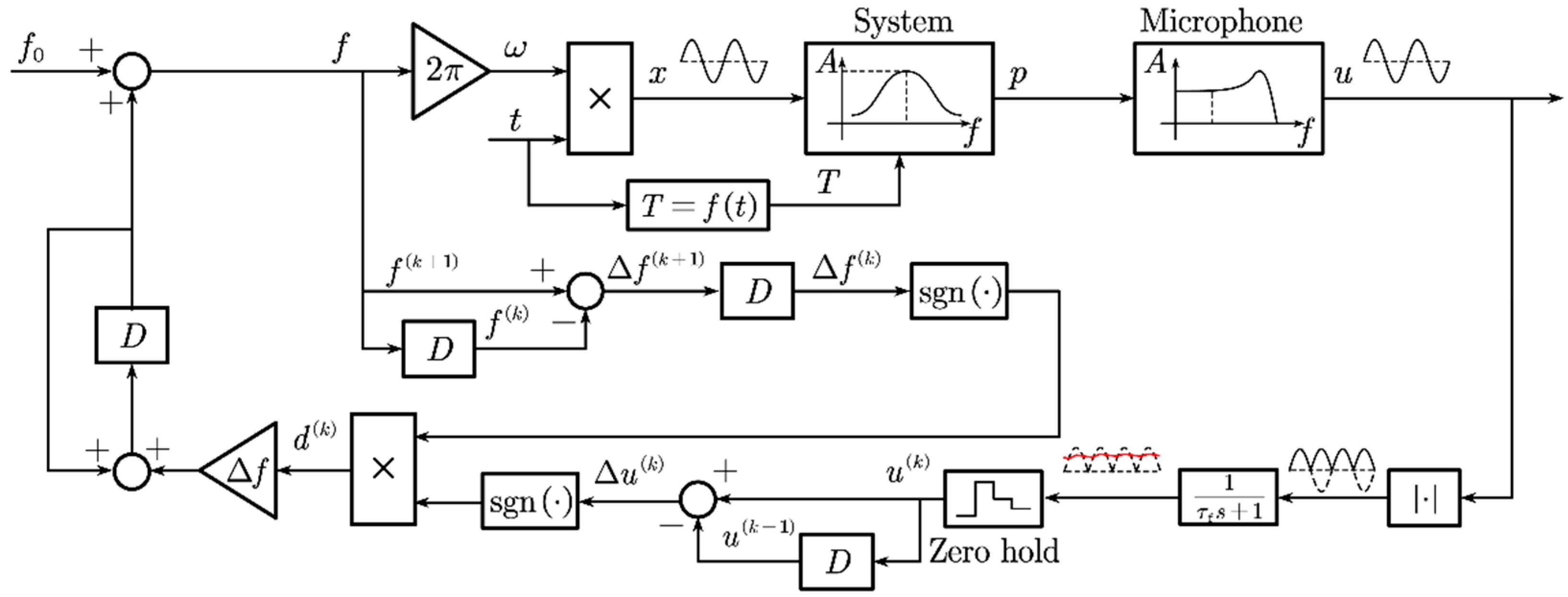

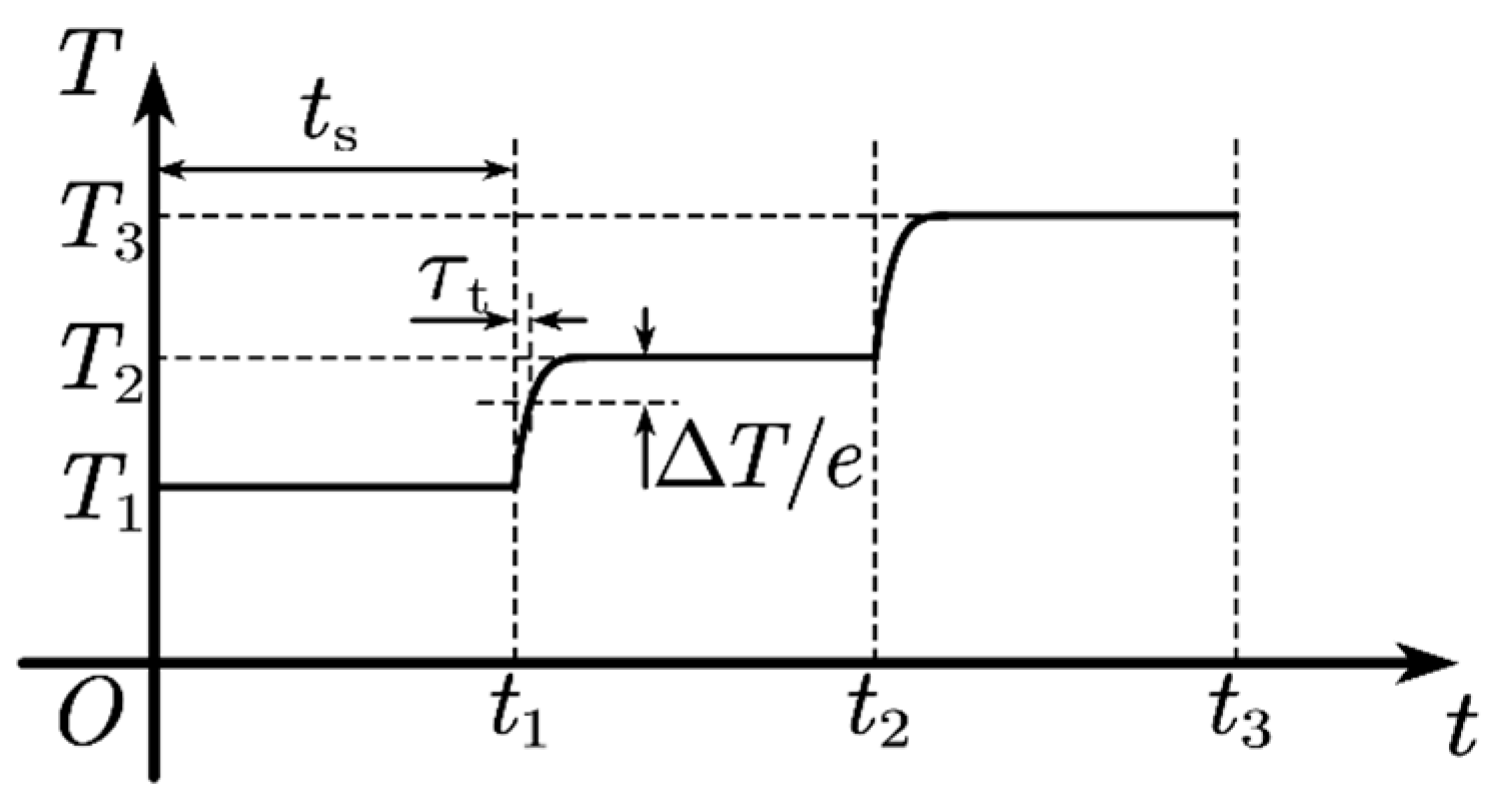

3.2. System Modeling and Equivalent Transfer Function

3.3. Simulation Verification of the Control Method

4. Experimental Results

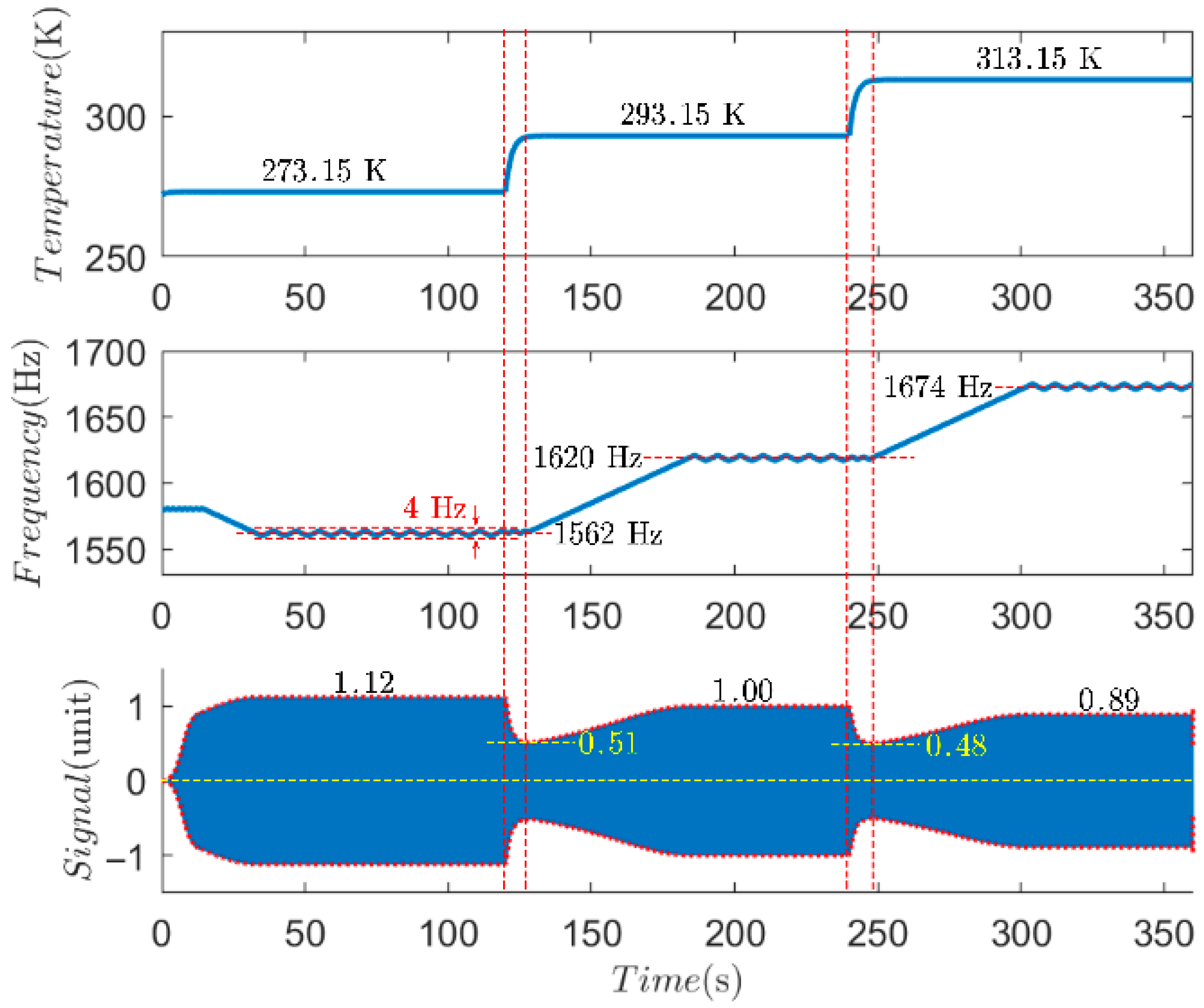

- a.

- The photoacoustic cell starts from the zero-signal point at 0 and transitions to the operating point 1 corresponding to the initial set frequency at 273.15 K;

- b.

- The operating frequency undergoes a negative perturbation, moving the operating point from 1 to the resonance point 2 at 273.15 K, while the operating frequency oscillates around the resonance frequency;

- c.

- The temperature changes to 293.15 K, causing the operating point to drop from 2 to point 3 on the amplitude-frequency curve at 293.15 K;

- d.

- The operating frequency undergoes a positive perturbation, moving the operating point from 3 to the resonance point 4 at this temperature, and oscillating around it;

- e.

- The temperature changes to 313.15 K, causing the operating point to drop from 4 to point 5 on the amplitude-frequency curve at 313.15 K;

- f.

- The operating frequency undergoes a positive perturbation, moving the operating point from 5 to the resonance point 6 at this temperature, and oscillating around it.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The frequency resolution of the signal generator controlling laser wavelength modulation imposes a lower limit on the frequency perturbation step length;

- (2)

- The voltage signal output from the microphone, which measures the acoustic signal, may be overwhelmed by noise, necessitating appropriate filtering of the electrical signal if such interference occurs;

- (3)

- When the initial frequency deviates significantly from the resonance frequency under operating temperature conditions, a larger frequency perturbation step is desirable to expedite the convergence of the working frequency toward the resonance frequency; conversely, once the working frequency approaches the resonance frequency, a smaller step is preferable to minimize signal fluctuations. Resolving this inherent trade-off requires optimization of the step values based on specific operational scenarios;

- (4)

- The implementation of perturbation-observation control encompasses multiple physical relaxation processes and transitional phases within the measurement system’s circuitry, demanding meticulous tuning of the controller’s timing sequence.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, X.; Jiang, T.; Bao, L. Dissolved gases generated of partial discharges and electrical breakdown in oil-paper insulation under AC-DC combined voltages. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Application, Shanghai, China, 17–20 September 2012; pp. 314–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Wang, J.; Dai, D.; Lei, J.; Li, L.; Wang, T. Partial discharge simulation of air gap defects in oil-paper insulation paperboard of converter transformer under different ratios of AC–DC combined voltage. Energies 2021, 14, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ma, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wan, L.; Li, K.; Zhang, G. Portable ppb-level acetylene photoacoustic sensor for transformer on-field measurement. Optik 2021, 243, 167440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.A. Evaluating transformer condition using DGA oil analysis. In Proceedings of the 2003 Annual Report Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 19–22 October 2003; pp. 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, N.A.; Abu-Siada, A. A new method to detect dissolved gases in transformer oil using NIR-IR spectroscopy. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosencwaig, A. Photoacoustics and Photoacoustic Spectroscopy; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilt, S.; Thévenaz, L. Wavelength modulation photoacoustic spectroscopy: Theoretical description and experimental results. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2006, 48, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Wen, J. Detection of dissolved gas in oil–insulated electrical apparatus by photoacoustic spectroscopy. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2015, 31, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Ju, T.; Lin, C.; Zhang, C.; Fan, M.; Zhou, Q. Detection of SF6 decomposition components under partial discharge by photoacoustic spectrometry and its temperature characteristic. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2016, 65, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 7252-2001; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. Guidelines for Analysis and Judgment of Gases Dissolved in Transformer Oil. Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Wei, Q.; Chen, W.; Xiong, Y. The research on simultaneous detection of dissolved gases in transformer oil using Raman spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference (EIC), Seattle, WA, USA, 7–10 June 2015; pp. 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.; Moulin, B.; Buixaderas, E.; Raimboux, N.; Herault, E.; Chazallon, B.; Cattey, H.; Magneron, N.; Oswalt, J.; Hocrelle, D. High temperatures and Raman scattering through pulsed spectroscopy and CCD detection. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2003, 34, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, V.P.; Salomasov, V.A. Mössbauer spectroscopy in determining the gas molecular state. Hyperfine Interact 2016, 237, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, V.; Fonsen, J.; Kauppinen, J.; Kauppinen, I. Extremely sensitive trace gas analysis with modern photoacoustic spectroscopy. Vib. Spectrosc. 2006, 42, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, H.; Sha, H.; Zhang, D.; Ning, H. A survey on gas sensing technology. Sensors 2012, 12, 9635–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kästle, R.; Sigrist, M.W. Temperature-dependent photoacoustic spectroscopy with a Helmholtz resonator. Appl. Phys. B 1996, 63, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borozdin, P.; Erushin, E.; Kozmin, A.; Bednyakova, A.; Miroshnichenko, I.; Kostyukova, N.; Boyko, A.; Redyuk, A. Temperature-Based Long-Term Stabilization of Photoacoustic Gas Sensors Using Machine Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 7518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, M.; Liu, Q.; Liu, K.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, X. Temperature-dependent photoacoustic spectroscopy with a T shaped photoacoustic cell at low temperature. Opt. Commun. 2013, 287, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, G.Z.; Bozóki, Z.; Miklós, A.; Lörincz, A.; Thöny, A.; Sigrist, M.W. Design and characterization of a windowless resonant photoacoustic chamber equipped with resonance locking circuitry. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1991, 62, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. On-line Analysis Technology of Dissolved Gases in Insulating Oil Based on Membrane Separation and Photoacoustic Spectroscopy. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, W. LII. The viscosity of gases and molecular force. Philos. Mag. 1893, 36, 507–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Li, H.; Nguyen, H.; Lien, C.; Yu, C.; Hsu, C.; Hsu, H.; Vaidyanathan, S. Analytical and numerical study of inlet velocity in radiation–convection duct systems. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 115122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Geometric Parameter | Value | Geometric Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Db | 20 mm | Lb | 50 mm |

| Dr | 3 mm | Lr | 100 mm |

| Dt | 1 mm | Lt | 1 mm |

| Dc | 3 mm | Lc | 4.3 mm |

| Dm | 2.8 mm | Lm | 3.3 mm |

| Temperature/°C | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation value/Hz | 1562.4 | 1576.5 | 1590.6 | 1604.9 | 1619.1 | 1632.7 | 1646.1 | 1659.0 | 1673.2 |

| Formula value/Hz | 1563.9 | 1577.7 | 1591.5 | 1605.3 | 1619.1 | 1632.9 | 1646.7 | 1660.5 | 1674.3 |

| Error value/Hz | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.4 | — | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| 2.78 | 2.76 | ||||||||

| Temperature/°C | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation value/unit | 1.1213 | 1.0887 | 1.0577 | 1.0281 | 1.0000 | 0.9729 | 0.9473 | 0.9227 | 0.8991 |

| Formula value/unit | 1.1229 | 1.0900 | 1.0587 | 1.0291 | 1.0001 | 0.9739 | 0.9483 | 0.9239 | 0.9005 |

| Error value/unit | 0.0016 | 0.0013 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0001 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0012 | 0.0014 |

| T(K) | 273.15 | 293.15 | 313.15 |

| f0(Hz) | 1562 | 1619 | 1673 |

| A(1) | 1.12 | 1.00 | 0.89 |

| Q(1) | 26.74 | 24.12 | 22.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ni, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Song, J.; Wu, Z.; He, L.; Zhang, Q. Enhancing Robustness in Photoacoustic Detection of Dissolved Acetylene in Transformer Oil: Temperature Effects on Resonance Frequency and Suppression Using the Perturbation Observation Method. Energies 2025, 18, 6512. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246512

Ni H, Wang J, Wu X, Song J, Wu Z, He L, Zhang Q. Enhancing Robustness in Photoacoustic Detection of Dissolved Acetylene in Transformer Oil: Temperature Effects on Resonance Frequency and Suppression Using the Perturbation Observation Method. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6512. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246512

Chicago/Turabian StyleNi, Heli, Jiajia Wang, Xinye Wu, Jinxuan Song, Zhicheng Wu, Lin He, and Qiaogen Zhang. 2025. "Enhancing Robustness in Photoacoustic Detection of Dissolved Acetylene in Transformer Oil: Temperature Effects on Resonance Frequency and Suppression Using the Perturbation Observation Method" Energies 18, no. 24: 6512. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246512

APA StyleNi, H., Wang, J., Wu, X., Song, J., Wu, Z., He, L., & Zhang, Q. (2025). Enhancing Robustness in Photoacoustic Detection of Dissolved Acetylene in Transformer Oil: Temperature Effects on Resonance Frequency and Suppression Using the Perturbation Observation Method. Energies, 18(24), 6512. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246512