From Energy-Intensive to Net-Zero Ready: A Campus Sustainability Transition at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Presents a structured conceptual pathway for shifting a large public Saudi university from energy-intensive operations to net-zero ready status, acknowledging the strategic role of solar energy.

- Proposes a mathematical optimization model to determine the optimal sizing of photovoltaic (PV) and battery energy storage systems (BESS) to achieve energy self-sufficiency and minimize grid reliance.

- Demonstrates the practical application and benefits of the proposed model through a detailed case study of IMSIU based on real campus load and PV generation data.

2. Proposed Mathematical Optimization Model

3. Input Data and Results

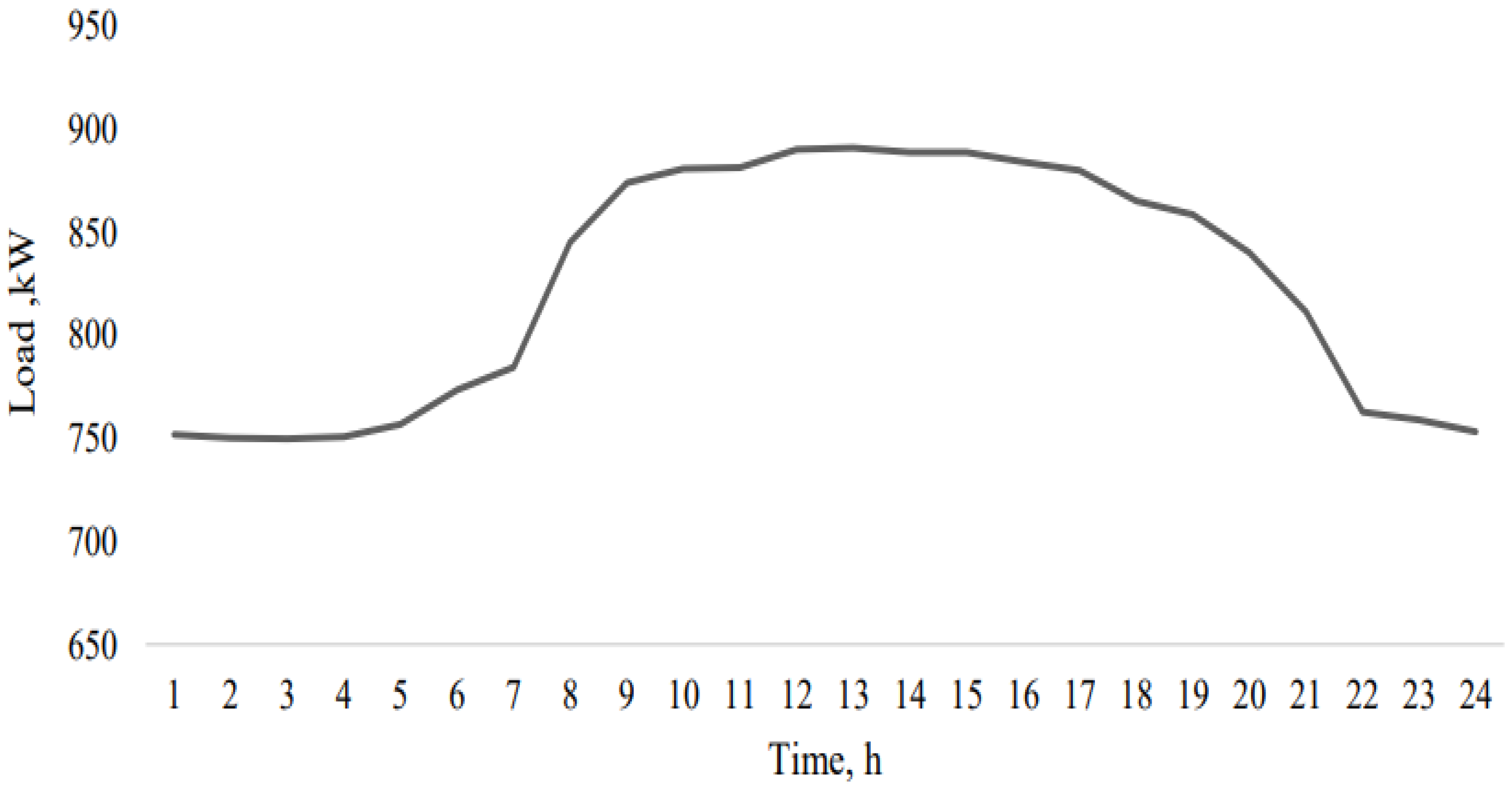

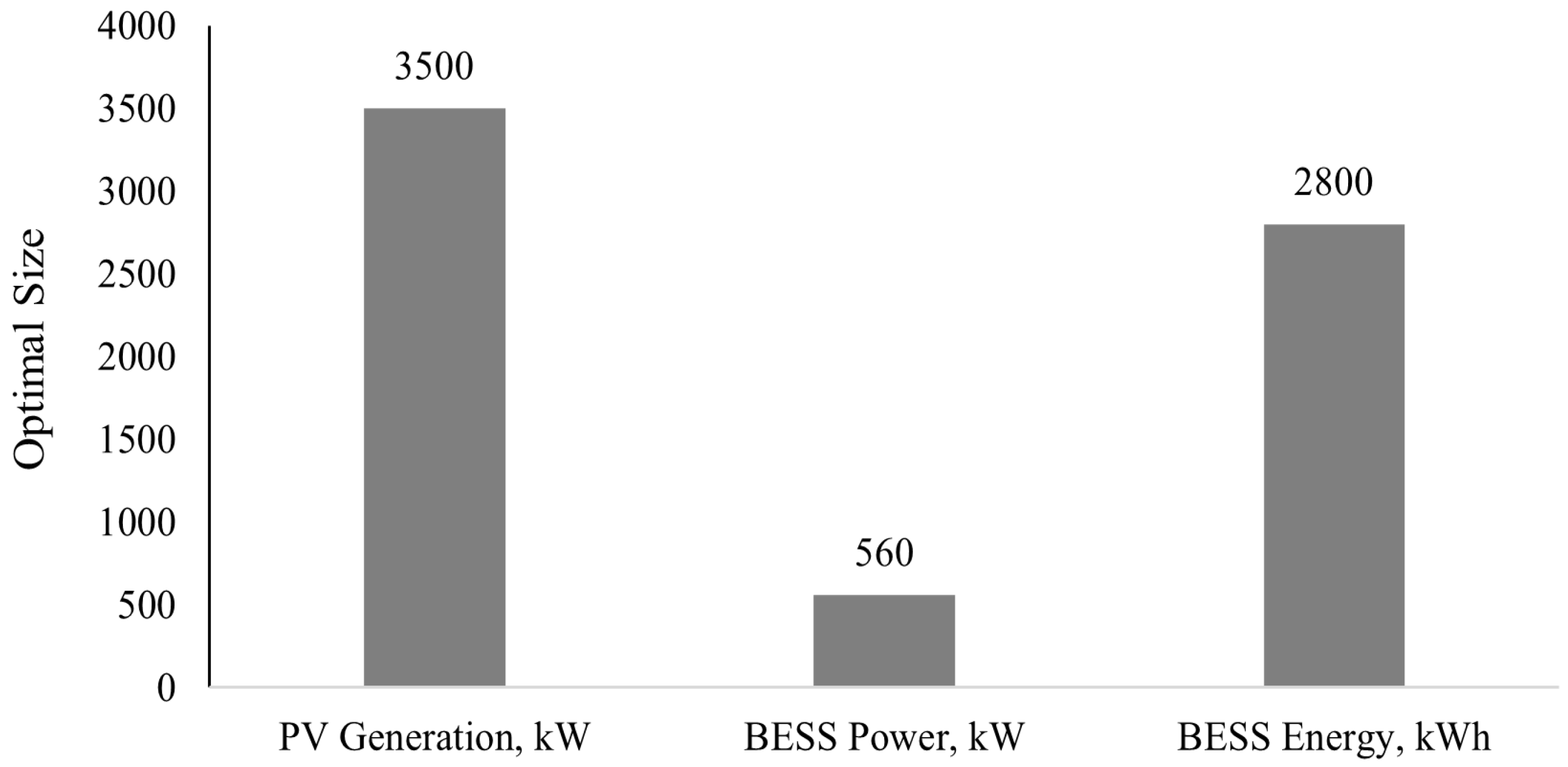

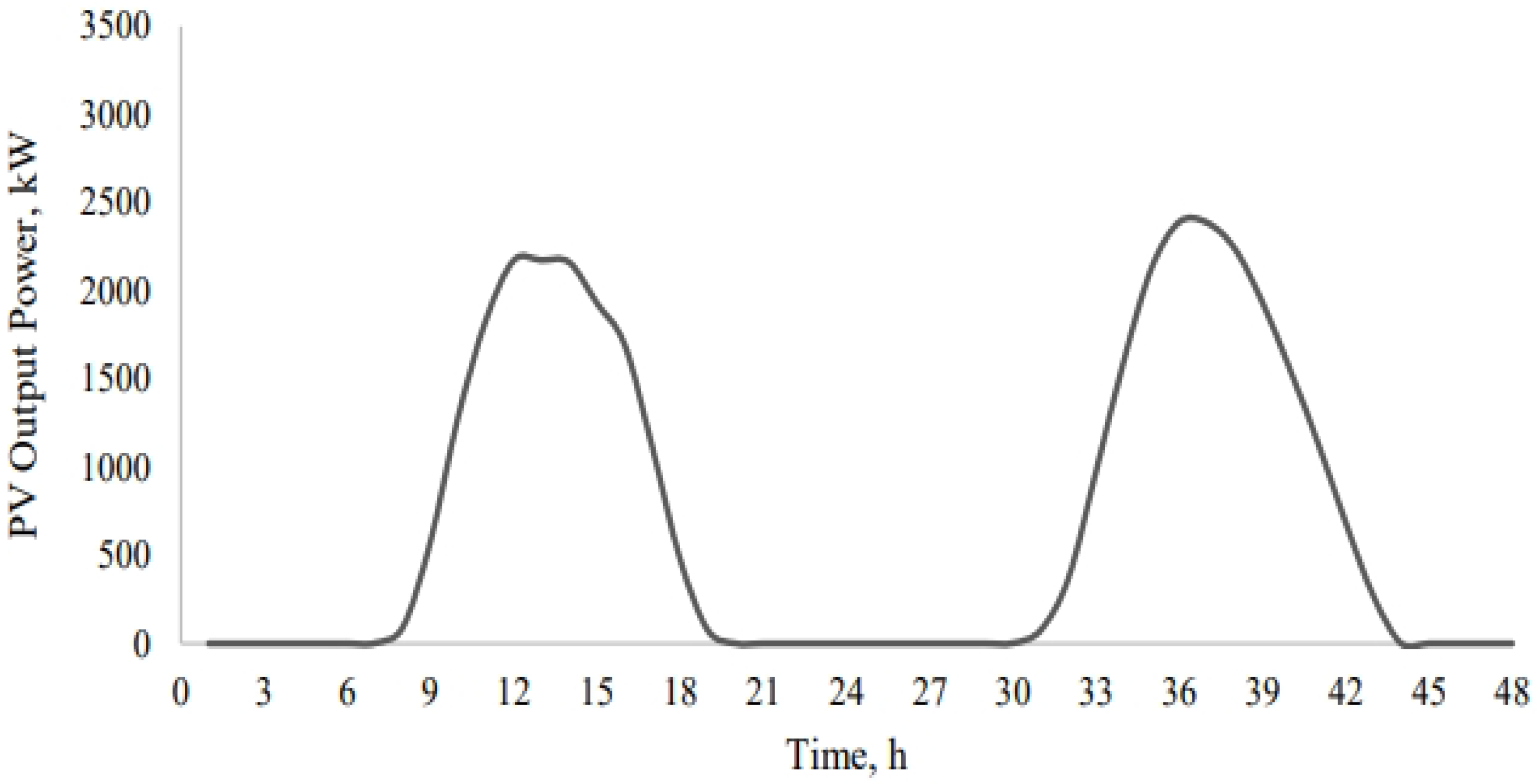

3.1. Input Data

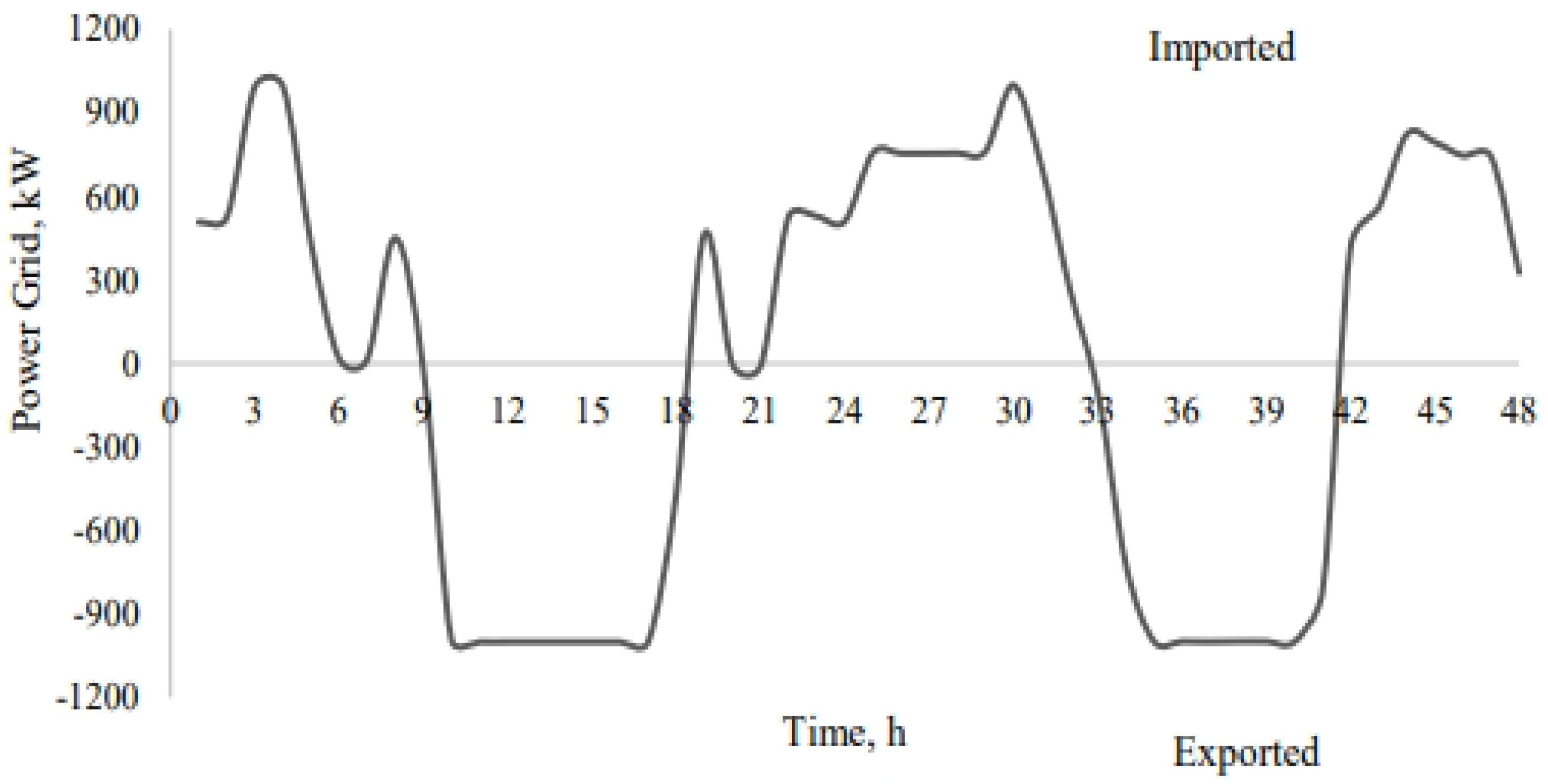

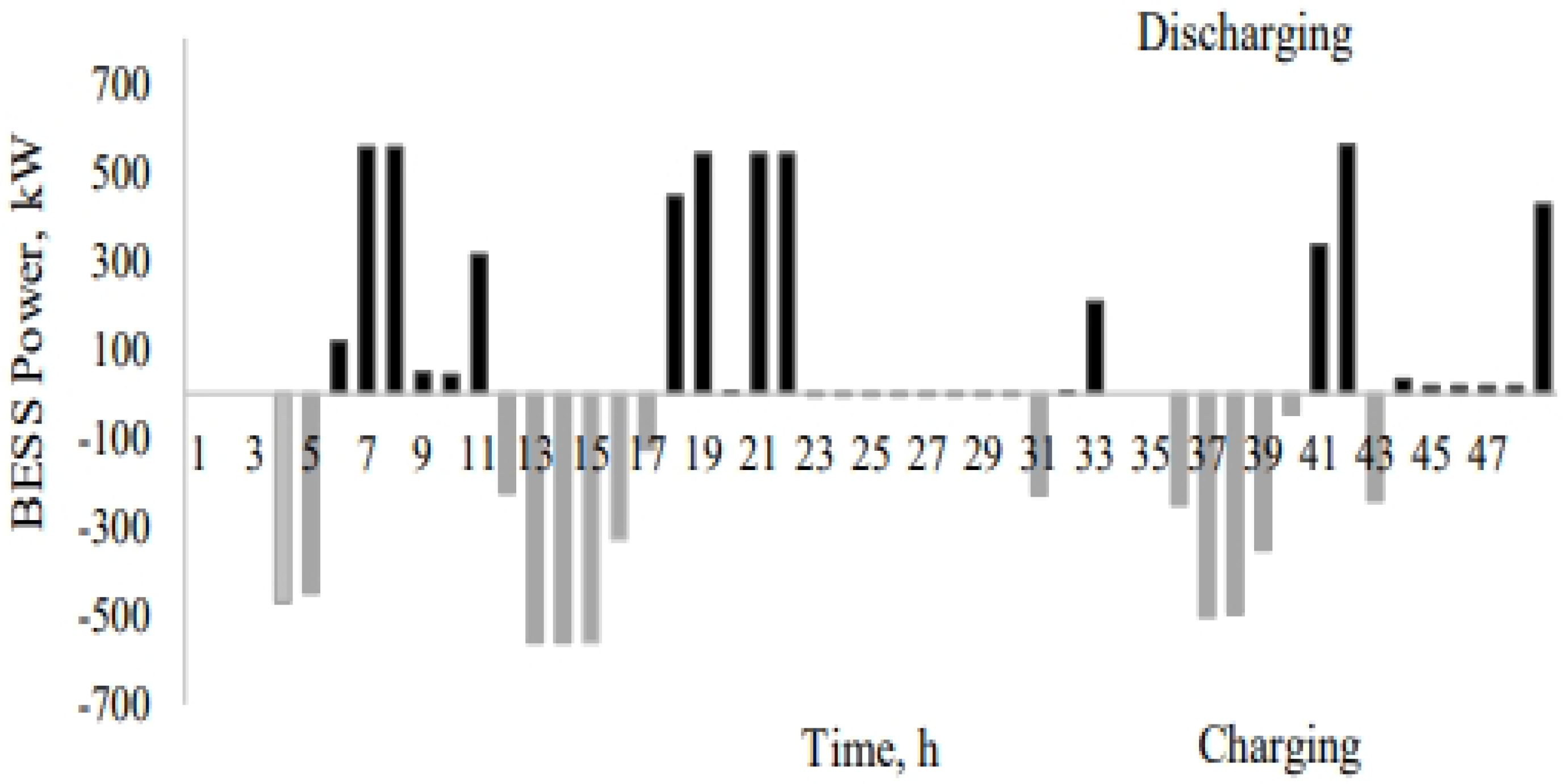

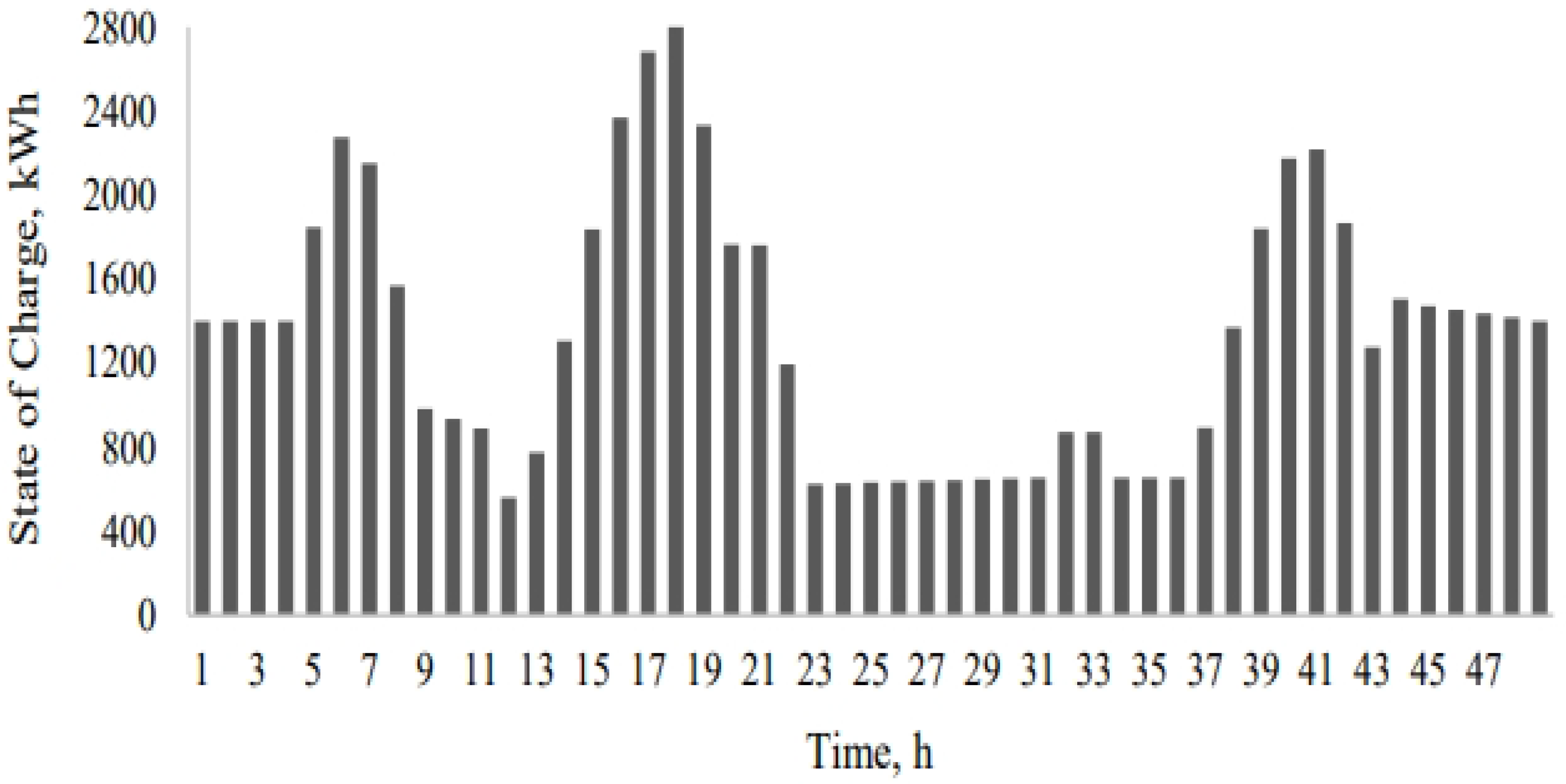

3.2. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| h | Time, h H |

| Time duration, h | |

| load of campus buildings, | |

| Capacity of photovoltaic generation, | |

| Capacity of BESS power, | |

| Capacity of BESS energy, | |

| Output power of PV Generation, | |

| Power charging of the BESS, | |

| Power discharging of the BESS, | |

| Exporting power to the main grid, | |

| Importing power from the main grid, | |

| BESS state of charge, |

References

- Soummane, S.; Ghersi, F. Projecting Saudi sectoral electricity demand in 2030 using a computable general equilibrium model. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 39, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Energy Services Company (Tarshid). Available online: https://www.tarshid.com.sa/en (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Abacıoğlu, S.; Ayan, B.; Pamucar, D. The Race to Sustainability: Decoding Green University Rankings Through a Comparative Analysis (2018–2022). Innov. High. Educ. 2025, 50, 241–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panait, M.; Ionescu, R.; Hysa, E.; Blessinger, P. Powering the Future: Green Energy and Sustainable Development in Universities. In Management in Higher Education for Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett-Itzhaki, Z.; Tifferet, S.; Berkowic, D.; Arviv, T.; Daya, A.; Carasso Romano, G.H.; Levi, A. Strategies and challenges for green campuses. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1469274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa’adi, N.; Abd Gapor, S.; Tamrulan, F.; Bohari, A.A.M. Towards a Sustainable Campus: A Review of Plans, Policies, and Guidelines on Sustainability in Malaysian Public Higher Education Institutions. J. Des. Built Environ. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, P.; Correia, A.; Delgado, J.; Fonseca, P.; de Almeida, A. University campus microgrid for supporting sustainable energy systems operation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/IAS 56th Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Technical Conference (I&CPS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 June–28 July 2020; IEEE: New York, NZ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjidemetriou, L.; Zacharia, L.; Kyriakides, E.; Azzopardi, B.; Azzopardi, S.; Mikalauskiene, R.; Al-Agtash, S.; Al-Hashem, M.; Tsolakis, A.; Ioannidis, D.; et al. Design factors for developing a university campus microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Energy Conference (ENERGYCON), Limassol, Cyprus, 3–7 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NZ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghussain, L.; Ahmad, A.D.; Abubaker, A.M.; Mohamed, M.A. An integrated photovoltaic/wind/biomass and hybrid energy storage systems towards 100% renewable energy microgrids in university campuses. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 46, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, C.A.; Popescu, C.L.; Popescu, M.O.; Roscia, M.; Seritan, G.; Panait, C. Techno-economic assessment of university energy communities with on/off microgrid. Renew. Energy 2022, 193, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdougui, H.; Dessaint, L.; Gagnon, G.; Al-Haddad, K. Modeling and optimal operation of a university campus microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Boston, MA, USA, 17–21 July 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jasim, N.I.; Gunasekaran, S.S.; AlDahoul, N.; Ahmed, A.N.; El-Shafie, A.; Sherif, M.; Mahmoud, M.A. Toward Sustainable Campus Energy Management: A Comprehensive Review of Energy Management, Predictive Algorithms, and Recommendations. Energy Nexus 2025, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, P.; Farbes, J.; Cutter, E.; Woo, C.K.; Wang, J. Microgrid and renewable generation integration: University of California, San Diego. Appl. Energy 2016, 169, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracco, S.; Brignone, M.; Delfino, F.; Procopio, R. An energy management system for the savona campus smart polygeneration microgrid. IEEE Syst. J. 2015, 11, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.M.; Koley, S.; Winter, A.; Enslin, J.H. A Technical and Economic Feasibility Study of Campus Microgrid Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 13th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Kiel, Germany, 26–29 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Es-sakali, N.; Pfafferott, J.; Mghazli, M.O.; Cherkaoui, M. Towards climate-responsive net zero energy rural schools: A multi-objective passive design optimization with bio-based insulations, shading, and roof vegetation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, B.R.; Ku, T.T.; Ke, Y.L.; Chuang, C.Y.; Chen, H.Z. Sizing the battery energy storage system on a university campus with prediction of load and photovoltaic generation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 52, 1136–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashed, S. Key performance indicators for Smart Campus and Microgrid. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chedid, R.; Sawwas, A.; Fares, D. Optimal design of a university campus micro-grid operating under unreliable grid considering PV and battery storage. Energy 2020, 200, 117510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, T.; Fioriti, D.; Poli, D.; Barberis, S.; Roncallo, F.; Gambino, V. Battery energy storage systems for ancillary services in renewable energy communities. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 260, 124988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husein, M.; Chung, I.Y. Optimal design and financial feasibility of a university campus microgrid considering renewable energy incentives. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, L.; Caamaño-Martín, E.; Sassenou, L.N.; Olivieri, F. Contribution of photovoltaic distributed generation to the transition towards an emission-free supply to university campus: Technical, economic feasibility and carbon emission reduction at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Renew. Energy 2020, 162, 1703–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, Y.; Ouammi, A.; Zejli, D. Model predictive control based demand response scheme for peak demand reduction in a Smart Campus Integrated Microgrid. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 162765–162778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgiozou, V.; Commin, A.; Dowson, M.; Rovas, D.; Mumovic, D. Scalable pathways to net zero carbon in the UK higher education sector: A systematic review of smart energy systems in university campuses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, E.D.; Betancur, D.; Isaac, I.A. Optimal power and battery storage dispatch architecture for microgrids: Implementation in a campus microgrid. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, T.; Raza, S.; Abrar, M.; Muqeet, H.A.; Jamil, H.; Qayyum, F.; Cheikhrouhou, O.; Alassery, F.; Hamam, H. Optimal Scheduling of Campus Microgrid Considering the Electric Vehicle Integration in Smart Grid. Sensors 2021, 21, 7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, B.; Meng, X.; Xiao, R. A Comprehensive Review on Technologies for Achieving Zero-Energy Buildings. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, O.; Rinchi, B.; Alnaser, S.; Haj-Ahmed, M. Transition towards a sustainable campus: Design, implementation, and performance of a 16 MWp solar photovoltaic system. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 68, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Crisostomi, E.; Leccese, F.; Mugnani, A.; Suin, S. Energy Savings in University Buildings: The Potential Role of Smart Monitoring and IoT Technologies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Liu, G.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, C. University-Campus-Based Zero-Carbon Action Plans for Accelerating the Zero-Carbon City Transition. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; De Masi, R.F.; Mauro, G.M.; Vanoli, G.P. Energy retrofit of educational buildings: Transient energy simulations, model calibration and multi-objective optimization towards nearly zero-energy performance. Energy Build. 2017, 144, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisio, A.; Rikos, E.; Glielmo, L. A model predictive control approach to microgrid operation optimization. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2014, 22, 1813–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifor, C.V.; Olteanu, A.; Zerbes, M. Key Performance Indicators for Smart Energy Systems in Sustainable Universities. Energies 2023, 16, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, A.C.; Panait, C.; Serițan, G.; Popescu, C.L.; Roscia, M. Maximizing renewable energy and storage integration in university campuses. Renew. Energy 2024, 230, 120871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawsawi, E.Y.; Salhein, K.; Zohdy, M.A. A Comprehensive Review of Existing and Pending University Campus Microgrids. Energies 2024, 17, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serat, Z.; Danishmal, M.; Mohammad Mohammadi, F. Optimizing hybrid PV/Wind and grid systems for sustainable energy solutions at the university campus: Economic, environmental, and sensitivity analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Wei, Q.; Xu, C.; Xiang, X.; Yu, H. Distributed Low-Carbon Energy Management of Urban Campus for Renewable Energy Consumption. Energies 2024, 17, 6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assareh, E.; Izadyar, N.; Jamei, E.; amin Monzavian, M.; Agarwal, S.; Pak, W. Optimization of solar farm design for energy efficiency in university campuses using machine learning: A case study. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 153, 110847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporation, G.D. General algebraic modeling system (GAMS), Software. Available online: https://www.gams.com (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Elshurafa, A.; Alsubaie, A.; Alabduljabbar, A.; Al-Hsaien, S. Solar PV on mosque rooftops: Results from a pilot study in Saudi Arabia. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfraidi, W. From Energy-Intensive to Net-Zero Ready: A Campus Sustainability Transition at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Saudi Arabia. Energies 2025, 18, 6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246509

Alfraidi W. From Energy-Intensive to Net-Zero Ready: A Campus Sustainability Transition at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Saudi Arabia. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246509

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfraidi, Walied. 2025. "From Energy-Intensive to Net-Zero Ready: A Campus Sustainability Transition at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Saudi Arabia" Energies 18, no. 24: 6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246509

APA StyleAlfraidi, W. (2025). From Energy-Intensive to Net-Zero Ready: A Campus Sustainability Transition at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Saudi Arabia. Energies, 18(24), 6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246509