Biogas Upgrading and Bottling Technologies: A Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Types of Biogas Upgrading Technologies

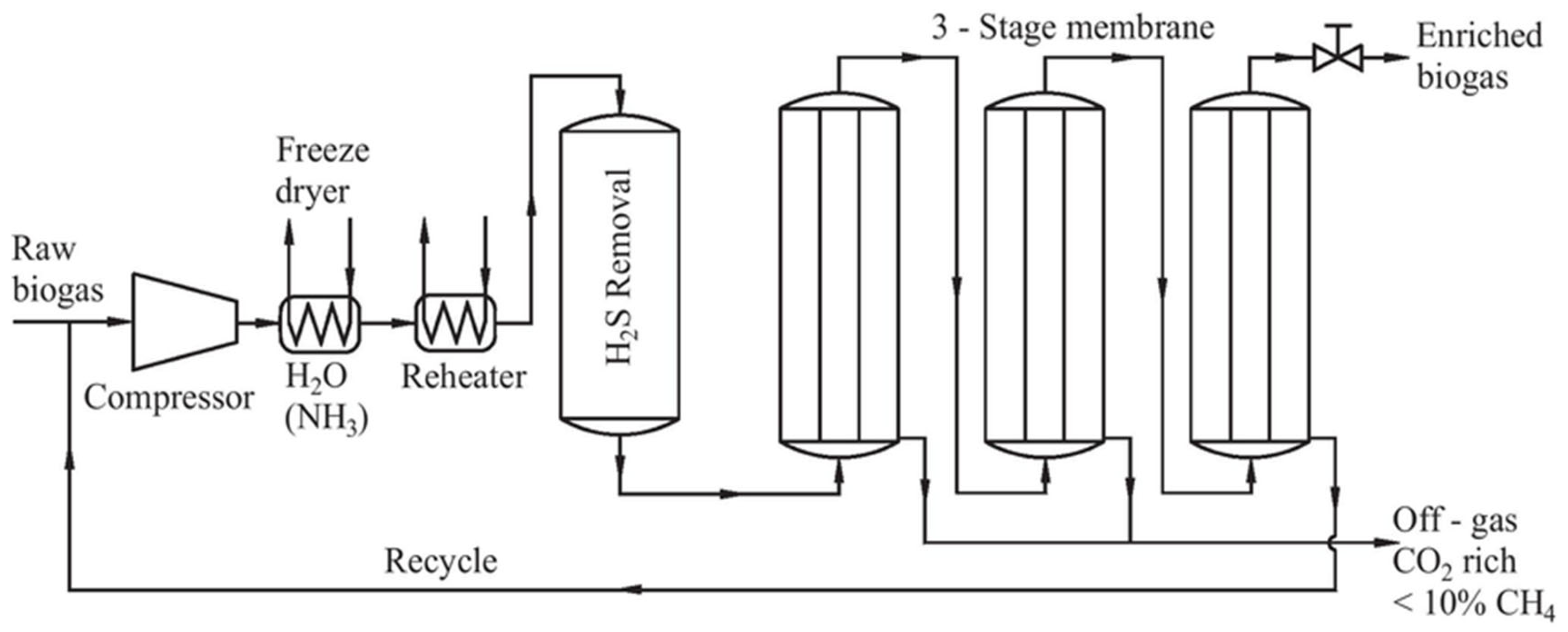

2.1. Membrane Separation

2.2. Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA)

2.3. Solvent-Based Biogas Upgrading

2.3.1. Water Scrubbing

2.3.2. Physical Scrubbing

2.3.3. Chemical Scrubbing

2.4. Hybrid System

2.5. Newer Biogas Upgrading Technologies

2.5.1. Cryogenic Distillation

2.5.2. Supersonic Separation

- Precision Engineering: Designing supersonic nozzles and separators that reliably create, and control shock waves and phase changes require advanced CFD modeling and precision manufacturing [35];

- Control Sensitivity: Small variations in pressure, temperature, or flow rate can significantly impact performance [36];

- Scalability Issues: The maintenance of efficiency and performance consistency when scaling up from lab or pilot plants to industrial systems is nontrivial [30];

- High Initial Investment: While operating costs may be lower than traditional methods, the upfront cost for designing, building, and installing supersonic separators can be high [30];

- Retrofitting Challenges: Integrating SS units into existing facilities often requires significant modifications to pipeline layouts, compressors, and control systems;

- Pressure Requirements: SS units require a high inlet gas pressure (often >70 bar) to generate and sustain supersonic flow, limiting their use to certain segments of the gas processing chain (e.g., upstream or midstream) [37];

- Limited Flexibility: SS is best suited for stable, high-volume flow streams. Variable or off-spec conditions (e.g., fluctuating composition or pressure) can impair separation efficiency [38];

- Conservatism in Industry: Operators often prefer proven technologies (like amine gas treatment or cryogenic distillation) over newer methods;

- Demonstration Gaps: There are few full-scale commercial implementations and limited third-party data on performance under diverse operating conditions [39];

- Competition with Established Technologies: In many cases, especially with falling gas prices or tight margins, conventional technologies remain more cost-effective in the short term;

- Return on Investment Uncertainty: The payback period for SS can be uncertain due to fluctuating energy costs, gas composition, and market conditions [30].

3. The Main Challenges of Optimizing Biogas Upgrade Plant Performance

3.1. Quality Control

3.2. Cost of Operations

3.3. Removal of Impurities

3.4. Complexity of Proceess

4. Comparison of Biogas Technologies

4.1. In-Depth Analysis of Trade-Offs

- Methane Recovery vs. Purity: Membrane systems are flexible but require multi-stage setups for high purity, increasing costs. PSA offers high purity but lower recovery and higher operational expenses. Water and physical scrubbing balance recovery and purity but depend on water/solvent availability and regeneration [55];

- Energy Consumption vs. Environmental Impact: Cryogenic and chemical scrubbing are energy-intensive, impacting operational costs and carbon footprint. Water scrubbing is less energy-intensive but unsustainable in water-scarce regions. Membrane and PSA systems offer moderate energy use but often require pre-treatment for contaminants [56];

- Capital and Operational Expenditure: Hybrid and cryogenic systems require high investment and skilled operation, suitable for large, high-value projects. Membrane and water scrubbing systems have moderate costs, making them ideal for decentralized or medium-scale operations [26];

- Feedstock and Site-Specific Constraints: Chemical and physical scrubbing tolerate variable or contaminated feedstocks, suitable for landfill or mixed-waste biogas. Membrane and PSA require cleaner feedstock to avoid fouling and adsorbent degradation [56].

4.2. Practical Operational Challenges

4.3. Selection of Appropriate Technologies Under Different Conditions

5. Bottling Biogas

- Compression of purified gas (biomethane) using mechanical compressors;

- Storage in high-pressure cylinders or adapted containers for safe and efficient use.

5.1. Material Used for Biogas Bottling

5.2. Materials and Cylinder Types for Biogas Bottling [72]

- Steel (Type I—All-Metal);

- Steel/Aluminum Liner + Composite Hoop Wrap (Type II);

- Metal Liner + Full Composite Wrap (Type III);

- Plastic/Polymer Liner + Full Composite Wrap (Type IV).

5.3. Importance of Biogas Bottling

5.4. Saftey Standards for Biogas Bottling

5.5. Logistical Challenges

5.6. Economic Barriers

5.7. Regulatory Constraints

5.8. Integrated Approach and Policy Recommendations

- Case Study 1:

- Bio-CNG Plant in Pune District, India

- Case Study 2:

- Community-Scale Biogas Bottling in Kisumu, Kenya

5.9. Key Lessons from the Case Studies

- Technology Performance: Both water scrubbing and PSA technologies can produce high purity biomethane (>95% CH4) under field conditions when paired with adequate pre-treatment;

- Operational Challenges: Variability in feedstock, energy supply, and system pressure can cause inconsistencies in methane purity and methane slip, especially in decentralized settings;

- Regulatory Compliance: Success depends heavily on supportive policies, certified equipment, and clearly defined safety and transport regulations;

- Economic Feasibility: While urban and peri-urban projects can achieve commercial viability with scale and subsidies, rural systems require donor involvement, cooperative ownership models, and cost-sharing to remain sustainable.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Black, M.J.; Roy, A.; Twinomunuji, E.; Kemausuor, F.; Oduro, R.; Leach, M.; Sadhukhan, J.; Murphy, R. Bottled biogas—An opportunity for clean cooking in Ghana and Uganda. Energies 2021, 14, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaideen, K.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Wilberforce, T.; Elsaid, K.; Sayed, E.T.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Olabi, A. Biogas role in achievement of the sustainable development goals: Evaluation, Challenges, and Guidelines. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 131, 104207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chynoweth, D.P.; Owens, J.M.; Legrand, R. Legrand, Renewable methane from anaerobic digestion of biomass. Renew. Energy 2001, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkneh, A.A. Biogas impurities: Environmental and health implications, removal technologies and future perspectives. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twinomunuji, E.; Kemausuor, F.; Black, M.; Roy, A.; Leach, M.; Sadhukhan, R.O.J.; Murphy, R. The Potential for Bottled Biogas for Clean Cooking in Africa. Available online: https://www.mecs.org.uk/working-papers/.3 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Abd, A.A.; Othman, M.R.; Helwani, Z.; Kim, J. Waste to wheels: Performance comparison between pressure swing adsorption and amine-absorption technologies for upgrading biogas containing hydrogen sulfide to fuel grade standards. Energy 2023, 272, 127060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritzke, S.; Jain, P. The Sustainability of decentralised renewable energy projects in developing countries: Learning lessons from Zambia. Energies 2021, 14, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilloso, G.; Arpia, K.; Khan, M.; Sapico, Z.A.; Lopez, E.C.R. Recent Advances in Membrane Technologies for Biogas Upgrading. Eng. Proc. 2024, 67, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodero, M.d.R.; Muñoz, R.; González-Sánchez, A.; Ruiz, H.A.; Quijano, G. Membrane materials for biogas purification and upgrading: Fundamentals, recent advances and challenges. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katariya, H.G.; Patolia, H.P. Advances in biogas cleaning, enrichment, and utilization technologies: A way forward. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 9565–9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantz, E.; Lemonnier, M.; Benizri, D.; Dietrich, N.; Hébrard, G. Innovative high-pressure water scrubber for biogas upgrading at farm-scale using vacuum for water regeneration. Appl. Energy 2023, 350, 121781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafi, N.N.; Agarwal, A.K. Biogas for Transport Sector: Current Status, Barriers, and Path Forward for Large-Scale Adaptation. In Alternative Fuels and Their Utilization Strategies in Internal Combustion Engines; Energy, Environment, and Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 229–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugagga, G.R.; Omosa, I.B.; Thoruwa, T. Optimization and Analysis of a Low-Pressure Water Scrubbing Biogas Upgrading System via the Taguchi and Response Surface Methodology Approaches. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2023, 12, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Kumar, J.; Vu, M.T.; Mohammed, J.A.; Pathak, N.; Commault, A.S.; Sutherland, D.; Zdarta, J.; Tyagi, V.K.; Nghiem, L.D. Biomethane production from anaerobic co-digestion at wastewater treatment plants: A critical review on development and innovations in biogas upgrading techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 142753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Abaid, A.; Wanderley, R.R.; Knuutila, H.K.; Jakobsen, J.P. Analysis and selection of optimal solvent-based technologies for biogas upgrading. Fuel 2021, 303, 121327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Subbarao, P.; Vijay, V.K.; Shah, G.; Sahota, S.; Singh, D.; Verma, M. Factors affecting methane loss from a water scrubbing based biogas upgrading system. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Sánchez, J.E.; Aguilar-Aguilar, F.A.; Hernández-Altamirano, R.; Venegas, J.A.V.; Aryal, D.R. Biogas purification processes: Review and prospects. Biofuels 2024, 15, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Biomethane Production and Applications. In Anaerobic Digestion-Biotechnology for Environmental Sustainability; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunlude, P.; Abunumah, O.; Orakwe, I.; Shehu, H.; Muhammad-Sukki, F.; Gobina, E. Comparative evaluation of the effect of pore size and temperature on gas transport in nano-structured ceramic membranes for biogas upgrading. Weentech Proc. Energy 2019, 5, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsair, A.; Cinar, S.O.; Alassali, A.; Abu Qdais, H.; Kuchta, K. Operational Parameters of Biogas Plants: A Review and Evaluation Study. Energies 2020, 13, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandree, P.; Thopil, G.A.; Ramchuran, S. Potential Opportunities to Convert Waste to Bio-Based Chemicals at an Industrial Scale in South Africa. Fermentation 2023, 9, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Usman, M.; Ashraf, M.A.; Dutta, N.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S. A review of recent advancements in pretreatment techniques of lignocellulosic materials for biogas production: Opportunities and Limitations. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2021, 10, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeiji, E.; Noorpoor, A.; Ghnavati, H. Increasing Biomethane Production in MSW Anaerobic Digestion Process by Chemical and Thermal Pretreatment and Process Commercialization Evaluation. Fermentation 2022, 8, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awe, O.W.; Zhao, Y.; Nzihou, A.; Minh, D.P.; Lyczko, N. A Review of Biogas Utilisation, Purification and Upgrading Technologies. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxfam, G.B.; Africa, E. Climate change, development and energy problems in South Africa: Another world is possible. Oxfam Policy Pract. Clim. Change Resil. 2009, 5, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadpour, H.; Cheng, K.Y.; Pivrikas, A.; Ho, G. A review of biogas upgrading technologies: Key emphasis on electrochemical systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2025, 91, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font-Palma, C.; Cann, D.; Udemu, C. Review of Cryogenic Carbon Capture Innovations and Their Potential Applications. C 2021, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Tarannum, K.; Chowdhury, A.T.; Rafa, N.; Nuzhat, S.; Kumar, P.S.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Biogas upgrading, economy and utilization: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4137–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PG&E Gas R&D and Innovation. Cryogenic Separation Technical Analysis; PG&E Gas R&D and Innovation: San Jose, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lakzian, E.; Yazdani, S.; Salmani, F.; Mahian, O.; Kim, H.D.; Ghalambaz, M.; Ding, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Wen, C. Supersonic separation towards sustainable gas removal and carbon capture. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 103, 101158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wen, C. Multi-objective optimization of supersonic separator for gas removal and carbon capture using three-field two-phase flow model and non-dominated sorting Genetic Algorithm-II (NSGA-II). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 358, 130363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, E.E.; Igbinedion, U.; Aimikhe, V.; Sanni, S.E.; Agwu, O.E. Evaluation of influential parameters for supersonic dehydration of natural gas: Machine learning approach. Pet. Res. 2022, 7, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Bian, J. Supersonic separation technology for natural gas processing: A review. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2019, 136, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bârsan, D.; Prodea, L.; Chiș, T. Analysis of supersonic techniques for separating water from extracted natural gas. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 13, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capecelatro, J. Modeling high-speed gas–particle flows relevant to spacecraft landings. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2022, 150, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altam, R.A.; Lemma, T.A.; Jufar, S.R.; Sakidin, H.; Yusof, M.; Sa’Ad, N.; Ching, D.L.C.; Karim, S.A. Trends in Supersonic Separator design development. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 131, 03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwuanyanwu, O.; Gil-Ozoudeh, I.; Okwandu, A.C.; Ike, C.S. Retrofitting existing buildings for sustainability: Challenges and innovations. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 2616–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaid, F.; Kuhn, A.; Vakkilainen, E.; Epple, B. Recent progress in the operational flexibility of 1 MW circulating fluidized bed combustion. Energy 2024, 306, 132287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Hefny, M.; Maksoud, M.I.A.A.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Rooney, D.W. Recent advances in carbon capture storage and utilisation technologies: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 797–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.; Jiang, K.; Feron, P. Techno-Economic Assessment for CO2 Capture from Air Using a Conventional Liquid-Based Absorption Process. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.A.; Villen-Guzman, M.; Rodriguez-Maroto, J.M.; Paz-Garcia, J.M. Technical analysis of CO2 capture pathways and technologies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzi, M.M.M.; Azmi, N.; Lau, K.K. Emerging Solvent Regeneration Technologies for CO2 Capture through Offshore Natural Gas Purification Processes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loachamin, D.; Casierra, J.; Calva, V.; Palma-Cando, A.; Ávila, E.E.; Ricaurte, M. Amine-Based Solvents and Additives to Improve the CO2 Capture Processes: A Review. Chemengineering 2024, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhi, T.P.; Putra, E.P.; Haristyawan, R.B. CO2 Freezing Area Concept for Improved Cryogenic Distillation of Natural Gas. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, P.; Flottes, E.; Favre, A.; Raynal, L.; Pierre, H.; Capela, S.; Peregrina, C. Techno-economic and Life Cycle Assessment of methane production via biogas upgrading and power to gas technology. Appl. Energy 2017, 192, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M. Biodigester and Feedstock Type: Characteristic, Selection, and Global Biogas Production. J. Eng. Res. Sci. 2022, 1, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.L.; Overen, O.K.; Obileke, K.; Botha, J.J.; Anderson, J.J.; Koatla, T.A.; Thubela, T.; Khamkham, T.I.; Ngqeleni, V.D. Financial and economic feasibility of bio-digesters for rural residential demand-side management and sustainable development. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, Y.S.; Singh, G.S.; Tekleyohannes, A.T. Optimizing the Benefits of Invasive Alien Plants Biomass in South Africa. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiniger, B.; Hupfauf, S.; Insam, H.; Schaum, C. Exploring Anaerobic Digestion from Mesophilic to Thermophilic Temperatures—Operational and Microbial Aspects. Fermentation 2023, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Osman, A.I.; Chen, Z.; Abdelhaleem, A.; Ihara, I.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Yap, P.-S.; Rooney, D.W. Social, environmental, and economic consequences of integrating renewable energies in the electricity sector: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1381–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosi, H.A.; Ezeh, E.M. Application of twister supersonic gas-liquid separator for improved natural gas recovery in a process stream. Niger. J. Trop. Eng. 2024, 18, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obileke, K.C. Sustainability evaluation of current biogas upgrading techniques. In Innovations in the Global Biogas Industry: Applications of Green Principles; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 213–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Ren, Z.; Si, W.; Ma, Q.; Huang, W.; Liao, K.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, P. Research progress on CO2 capture and utilization technology. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 66, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Palacio, L.; Muñoz, R.; Prádanos, P.; Hernandez, A. Recent Advances in Membrane-Based Biogas and Biohydrogen Upgrading. Processes 2022, 10, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmakani, A.; Wadi, B.; Manović, V.; Nabavi, S.A. Comparative Evaluation of PSA, PVSA, and Twin PSA Processes for Biogas Upgrading: The Purity, Recovery, and Energy Consumption Dilemma. Energies 2023, 16, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkotsis, P.; Kougias, P.; Mitrakas, M.; Zouboulis, A. Biogas upgrading technologies—Recent advances in membrane-based processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 3965–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Lee, J.T.E.; Bashir, M.A.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Ok, Y.S.; Tong, Y.W.; Shariati, M.A.; Wu, S.; Ahring, B.K. Current status of biogas upgrading for direct biomethane use: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, F.I.; Porter, R.T.J.; Catalanotti, E.; Mahgerefteh, H. Performance and Cost Analysis of Pressure Swing Adsorption for Recovery of H2, CO, and CO2 from Steelworks Off-Gases. Energies 2025, 18, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Kovalev, A.A.; Zhuravleva, E.A.; Kovalev, D.A.; Litti, Y.V.; Masakapalli, S.K.; Pareek, N.; Vivekanand, V. Recent Development in Physical, Chemical, Biological and Hybrid Biogas Upgradation Techniques. Sustainability 2022, 15, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, E.; Wicker, R.J.; Show, P.-L.; Bhatnagar, A. Biologically-mediated carbon capture and utilization by microalgae towards sustainable CO2 biofixation and biomass valorization—A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 130884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, A.M.; El-Maghlany, W.M.; Eldrainy, Y.A.; Attia, A. New approach for biogas purification using cryogenic separation and distillation process for CO2 capture. Energy 2018, 156, 328–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Khalil, A.G.; Sobhy, A.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Olabi, A. Advancements and challenges in hybrid energy storage systems: Components, control strategies, and future directions. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 20, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, M.K.; Mustafa, M.A.; Ahmed, H.S.; Mohammed, A.J.; Ghazy, H.; Shakir, M.N.; Lawas, A.M.; Mohammed, S.K.; Idan, A.H.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; et al. Biogas: Production, properties, applications, economic and challenges: A review. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkotsis, P.; Peleka, E.; Zouboulis, A. Membrane-Based Technologies for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture from Flue Gases: Recent Progress in Commonly Employed Membrane Materials. Membranes 2023, 13, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloni, M.; Di Marcoberardino, G. Biogas Upgrading Technology: Conventional Processes and Emerging Solutions Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Sun, L.; Huang, G. An integrated framework for feasibility analysis and optimal management of a neighborhood-scale energy system with rooftop PV and waste-to-energy technologies. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 70, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallamothu, R.B.; Teferra, A.; Rao, B.A. Biogas purification, compression and bottling. Glob. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2013, 2, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.; Kumar, S.; dev Sharma, K. Bottling of biogas—A renewable approach. Eng. J. Appl. Scopes 2016, 1, 28–32. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322055714 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Obileke, K.; Nwokolo, N.; Makaka, G.; Mukumba, P.; Onyeaka, H. Anaerobic digestion: Technology for biogas production as a source of renewable energy—A review. Energy Environ. 2021, 32, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erick, M.K. Adoption of Biogas Technology and Its Contribution to Livelihoods and Forest Conservation in Abogeta Division, Meru County, Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, A. Compressors and Compressed Air Systems Course No: M06-018 Credit: 6 PDH. Available online: www.cedengineering.com (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Shonhiwa, C.; Mapantsela, Y.; Makaka, G.; Mukumba, P.; Shambira, N. Biogas Valorisation to Biomethane for Commercialisation in South Africa: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndunguru, E.M. Increasing Access to Clean Cooking: The Practicality of Pay-Go in Promoting Adoption of Bottled Gas in Kinondoni, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Int. J. Clean Coal Energy 2021, 10, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutungwazi, A.; Mukumba, P.; Makaka, G. Biogas digester types installed in South Africa: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11119-1; Gas Cylinders—Gas Cylinders of Composite Construction—Specification and Test Methods—Part 1: Hoop-Wrapped Composite Gas Cylinders. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Hatinoglu, M.D.; Sanin, F.D. Fate and effects of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) microplastics during anaerobic digestion of alkaline-thermal pretreated sludge. Waste Manag. 2022, 153, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, H.; Saady, N.M.C.; Zendehboudi, S. Safety in biogas plants: An analysis based on international standards and best practices. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 200, 107390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Decentralized biogas technology of anaerobic digestion and farm ecosystem: Opportunities and challenges. Front. Energy Res. 2014, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadeyan, O.J.; Muthivhi, J.; Linganiso, L.Z.; Deenadayalu, N.; Alabi, O.O. Biogas production and techno-economic feasibility studies of setting up household biogas technology in Africa: A critical review. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 4788–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidigal, L.P.V.; de Souza, T.A.Z.; da Costa, R.B.R.; Roque, L.F.d.A.; Frez, G.V.; Pérez-Rangel, N.V.; Pinto, G.M.; Ferreira, D.J.S.; Cardinali, V.B.A.; de Carvalho, F.S.; et al. Biomethane as a Fuel for Energy Transition in South America: Review, Challenges, Opportunities, and Perspectives. Energies 2025, 18, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, H.H.; Hoex, B.; Hallam, B.J. Strategic investment risks threatening India’s renewable energy ambition. Energy Strat. Rev. 2022, 43, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrän, D.; Adetona, A.; Borchers, M.; Cyffka, K.-F.; Daniel-Gromke, J.; Oehmichen, K. Potential contribution of biogas to net zero energy systems—A comparative study of Canada and Germany. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, H.; Saady, N.M.C.; Khan, F.; Zendehboudi, S.; Albayati, T.M. Biogas plants accidents: Analyzing occurrence, severity, and associations between 1990 and 2023. Saf. Sci. 2024, 177, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Liu, B.; Wu, D. Impacts of urbanization and associated factors on ecosystem services in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, China: Implications for land use policy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, R.; Moncur, Q. Small-Scale Farming: A Review of Challenges and Potential Opportunities Offered by Technological Advancements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virginia, D.D.; Buana, I.G.S.; Kamil, M.; Boyke, C.; Lazuardi, S.D.; Wuryaningrum, P. Biomethane-Compressed Natural Gas (Bio-CNG) Distribution Model in Support of The Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Substitution Program. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Institute of Physics: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianati, K.; Schäfer, L.; Milner, J.; Gómez-Sanabria, A.; Gitau, H.; Hale, J.; Langmaack, H.; Kiesewetter, G.; Muindi, K.; Mberu, B.; et al. A system dynamics-based scenario analysis of residential solid waste management in Kisumu, Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology | CH4 Purity (%) | CO2 Removal Efficiency (%) | Methane Slip (%) | Energy Requirement (kWh/Nm3) | CAPEX | OPEX | Typical Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Separation | 95–98 | 80–98 | 1–4 | 0.2–0.5 | Moderate | Low to Moderate | Small to Medium (50–1000 Nm3/h) |

| Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) | 96–99 | 95–99 | 0.5–2 | 0.25–0.5 | Moderate to High | Moderate | Small to Medium (50–1500 Nm3/h) |

| Water Scrubbing | 90–98 | 80–95 | 2–10 | 0.2–0.4 | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High | Small to Medium (50–2000 Nm3/h) |

| Chemical Scrubbing | 97–99 | >99 | <1 | 0.3–0.6 | High | High | Medium to Large (>500 Nm3/h) |

| Cryogenic Separation | >99 | >99 | <0.1 | 0.5–1.2 | Very High | Moderate to High | Large (>1000 Nm3/h) |

| Supersonic Separation | 98–99 | >99 | <0.5 | 0.6–1.5 | High | Moderate | Large (>1000 Nm3/h) |

| Hybrid Systems | >99 | >99 | <1 | 0.4–0.8 | Very High | Moderate to High | Flexible (all scales) |

| Method | Energy Use | OPEX | Environmental Impact | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Scrubbing | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| PSA | High | Medium-High | Low | High |

| Chemical Absorption | Low | High | Medium-High | High |

| Membrane Separation | High | Medium | Low | Very High |

| Cryogenic | Low | High | Medium | Medium-High |

| Supersonic | High | Low-Med | Very Low | Medium |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mapantsela, Y.; Mukumba, P. Biogas Upgrading and Bottling Technologies: A Critical Review. Energies 2025, 18, 6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246506

Mapantsela Y, Mukumba P. Biogas Upgrading and Bottling Technologies: A Critical Review. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246506

Chicago/Turabian StyleMapantsela, Yolanda, and Patrick Mukumba. 2025. "Biogas Upgrading and Bottling Technologies: A Critical Review" Energies 18, no. 24: 6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246506

APA StyleMapantsela, Y., & Mukumba, P. (2025). Biogas Upgrading and Bottling Technologies: A Critical Review. Energies, 18(24), 6506. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246506