Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of SOFC-GT Hybrid System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

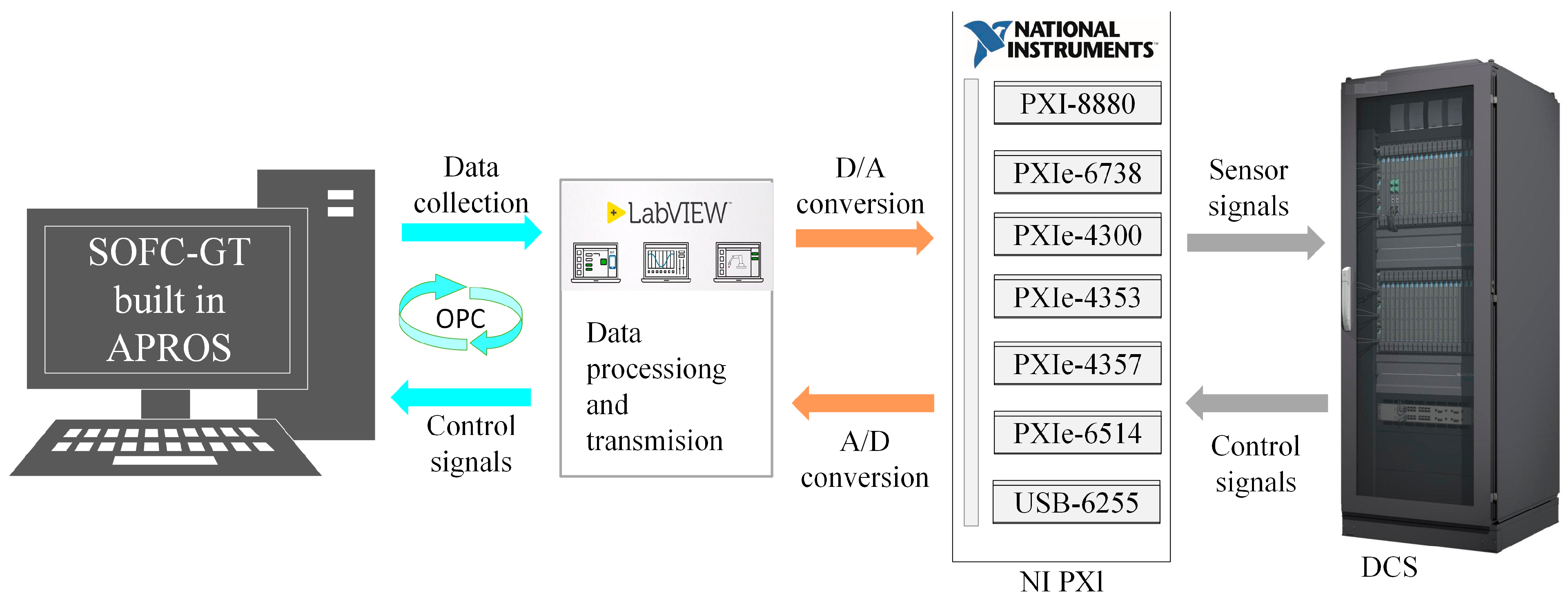

- This study presents a rapidly deployable C-HILS platform. By integrating four core components, namely APROS V6.07 software, NI PXI hardware, LabVIEW 2020 software, and a DCS, this platform not only retains the flexibility and safety inherent to digital simulation but also replicates the real dynamic behaviors of physical control hardware (e.g., sensor delays and actuator nonlinearities).

- (2)

- A dynamic model of the SOFC-GT bottoming cycle hybrid system was established based on APROS, encompassing core components such as the solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC), gas turbine (GT), compressor, and heat exchanger. This model exhibits a steady-state relative error of less than 4%. Three transient experiments were conducted to compare the control performance of C-HILS and full-digital simulation.

- (3)

- A standardized program for converting between digital parameters and voltage signals is developed based on the NI PXI system. This program not only effectively addresses compatibility issues in cross-device data interaction but also boasts high transferability: it is not dependent on the specific SOFC-GT system, can be directly migrated to other energy systems, and thus provides a universal technical solution for the digital testing of various energy systems.

2. C-HILS Platform Description

2.1. Description of the SOFC-GT Hybrid System

2.2. C-HILS Platform Design and Construction

2.2.1. C-HILS Platform Frame Design

2.2.2. Physical Equipment Composition

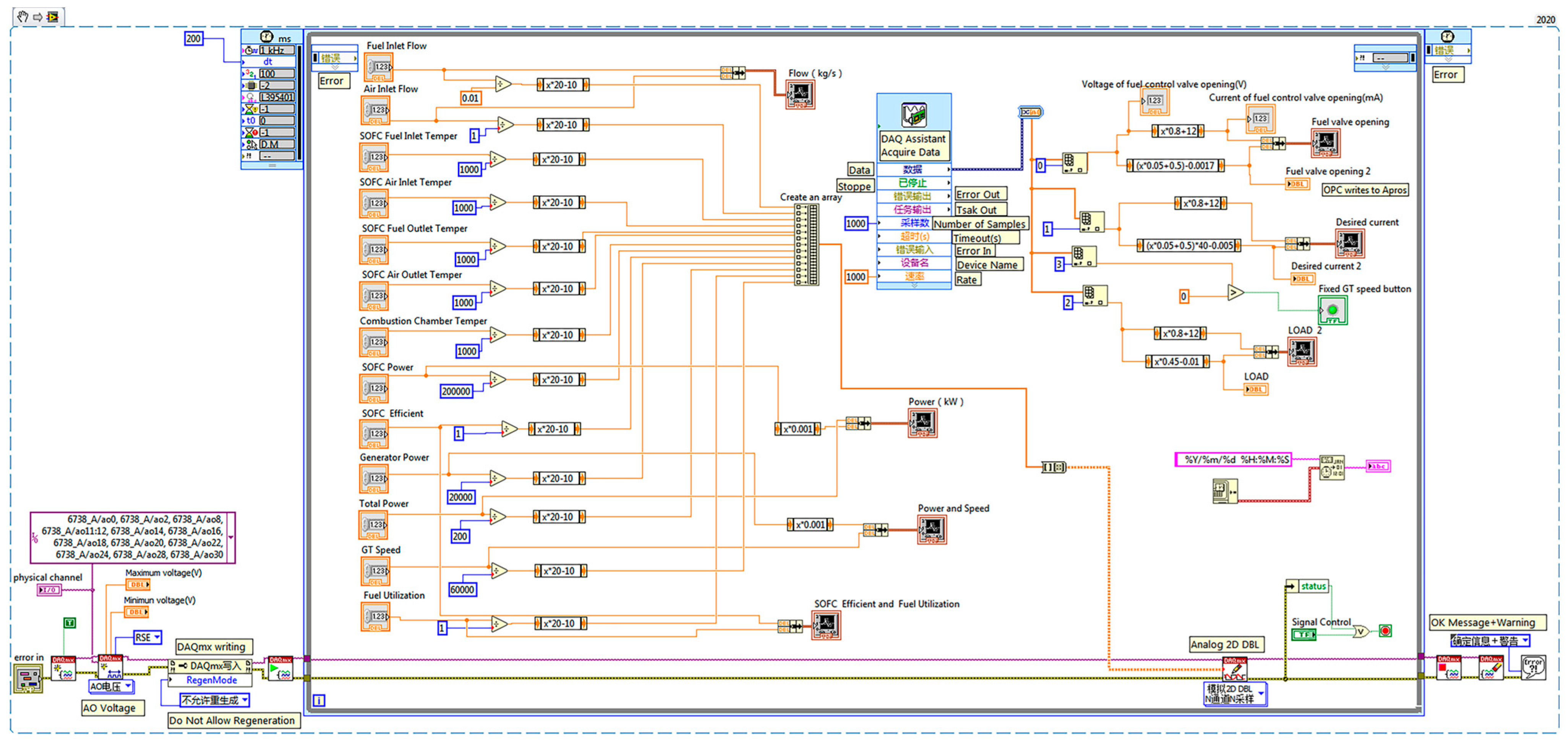

2.3. LabVIEW Configuration

3. SOFC-GT Hybrid System Dynamical Model Based on APROS

3.1. SOFC Model

3.1.1. Mathematical Model

- (1)

- The air entering the cell cathode is composed of 79% nitrogen and 21% oxygen;

- (2)

- All gases are ideal gases;

- (3)

- The pressures in the anode and cathode inside the fuel cell are assumed to be constant and balanced;

- (4)

- The effects of kinetic energy and potential energy are neglected.

3.1.2. Parameter Settings

3.2. Turbine Model

3.3. Compressor Model

3.4. Shaft Model

3.5. Heat Exchanger Model

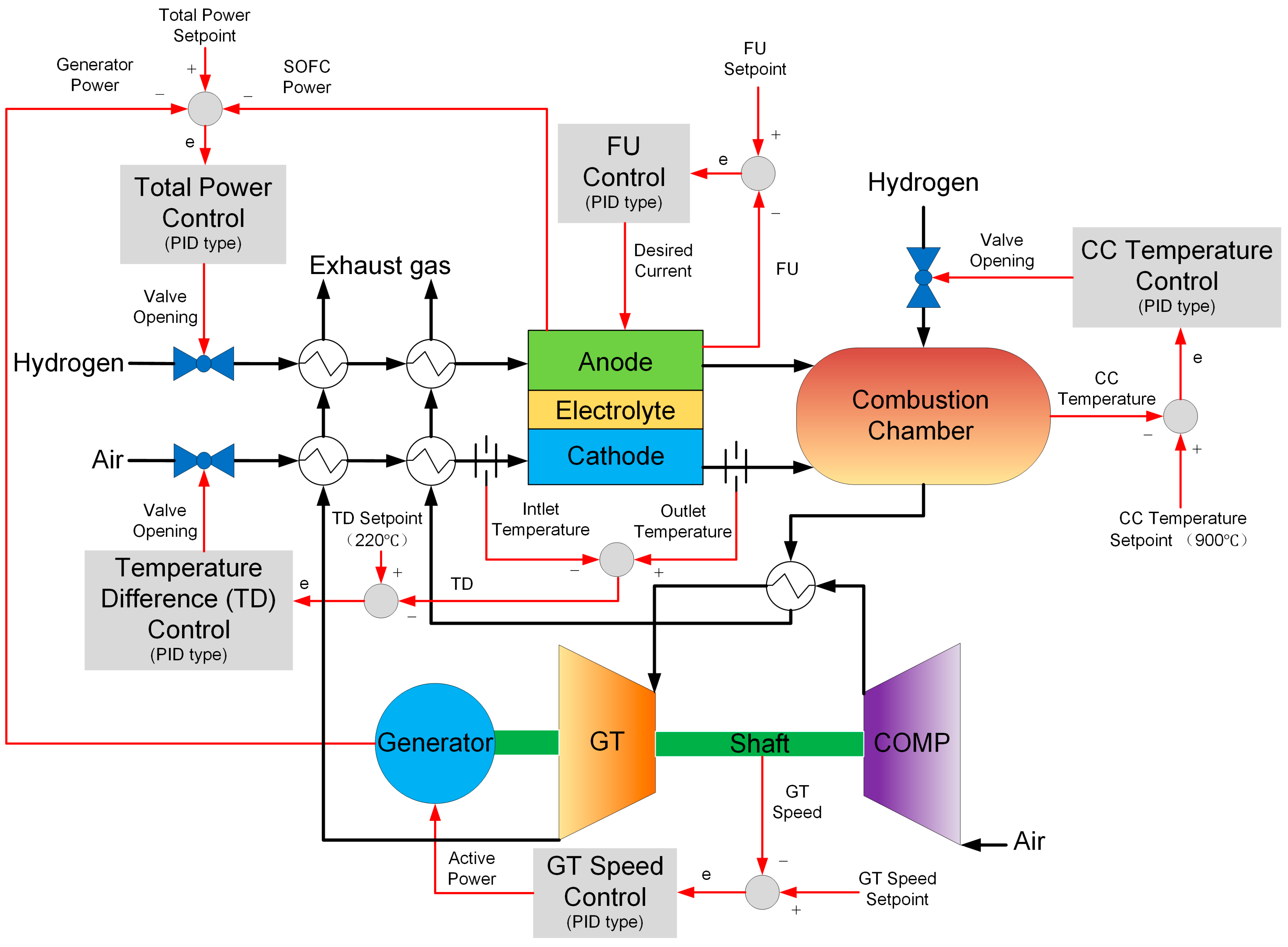

3.6. Control System Design

3.6.1. Total Power Control

- (1)

- Maintain a constant SOFC fuel utilization by controlling the SOFC desired current, and adjust the total output power of the hybrid system by regulating the SOFC fuel inlet valve.

- (2)

- Keep the SOFC fuel utilization constant by adjusting the SOFC fuel inlet valve, and modulate the total output power by controlling the SOFC desired current.

3.6.2. Fuel Utilization (FU) Control

3.6.3. GT Speed Control

4. DCS Configuration

4.1. Points Configuration

4.2. Control Configuration

4.3. HMI Configuration

5. Results and Discussion

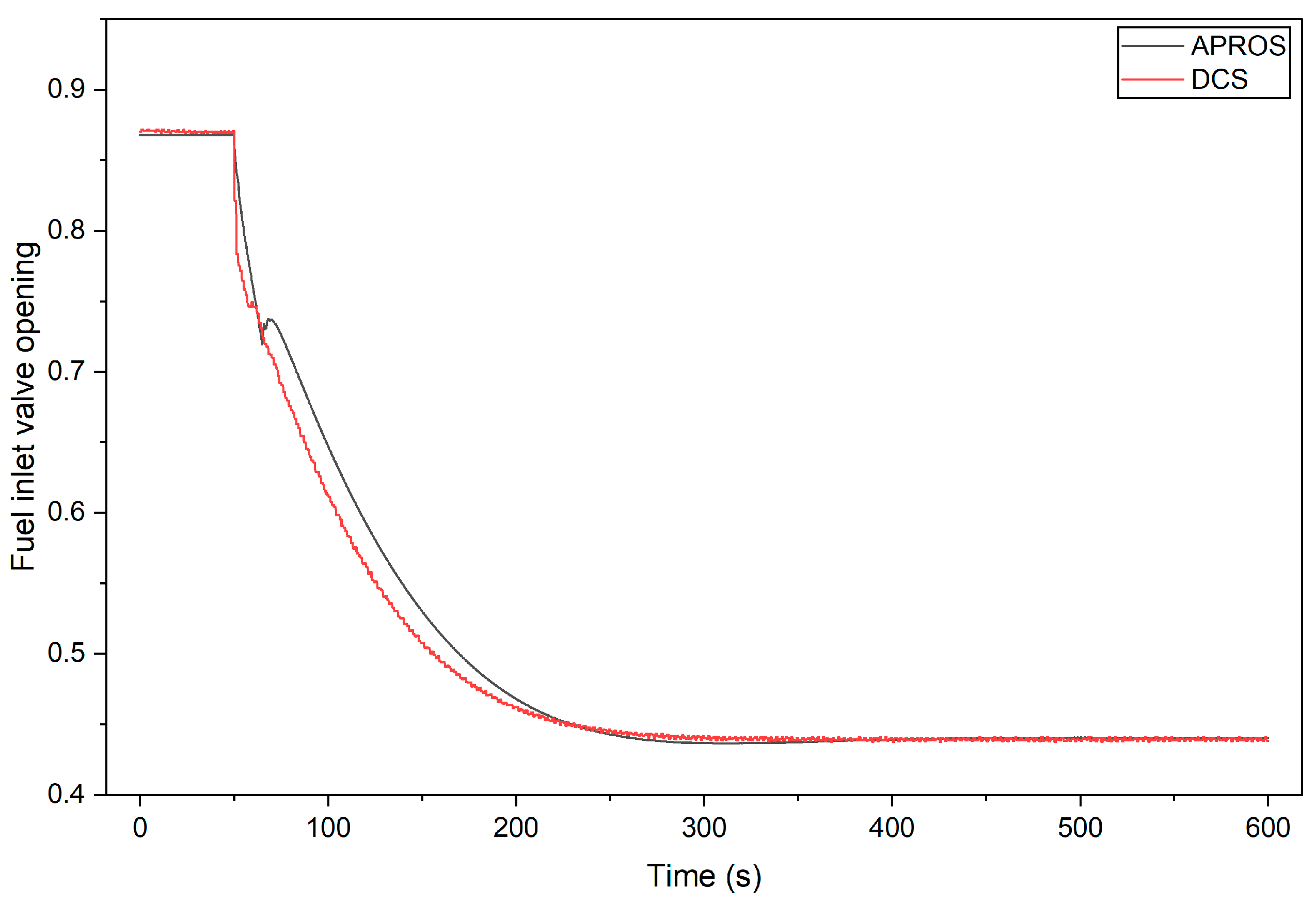

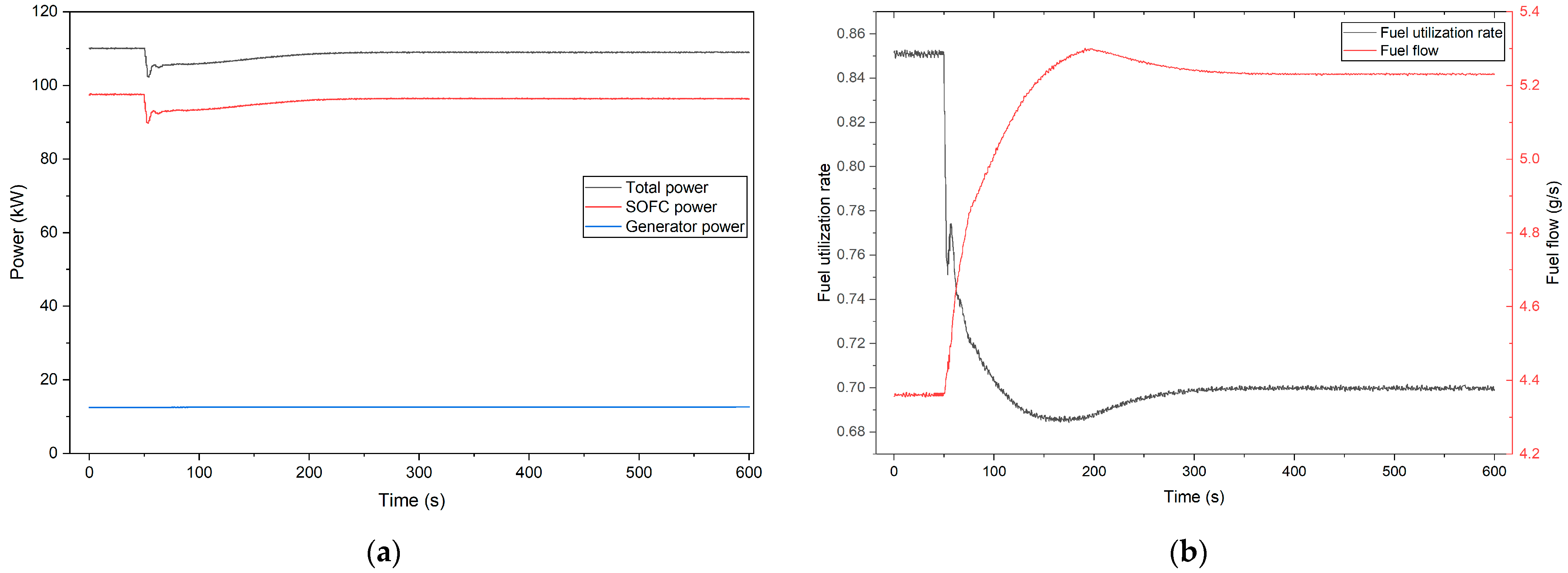

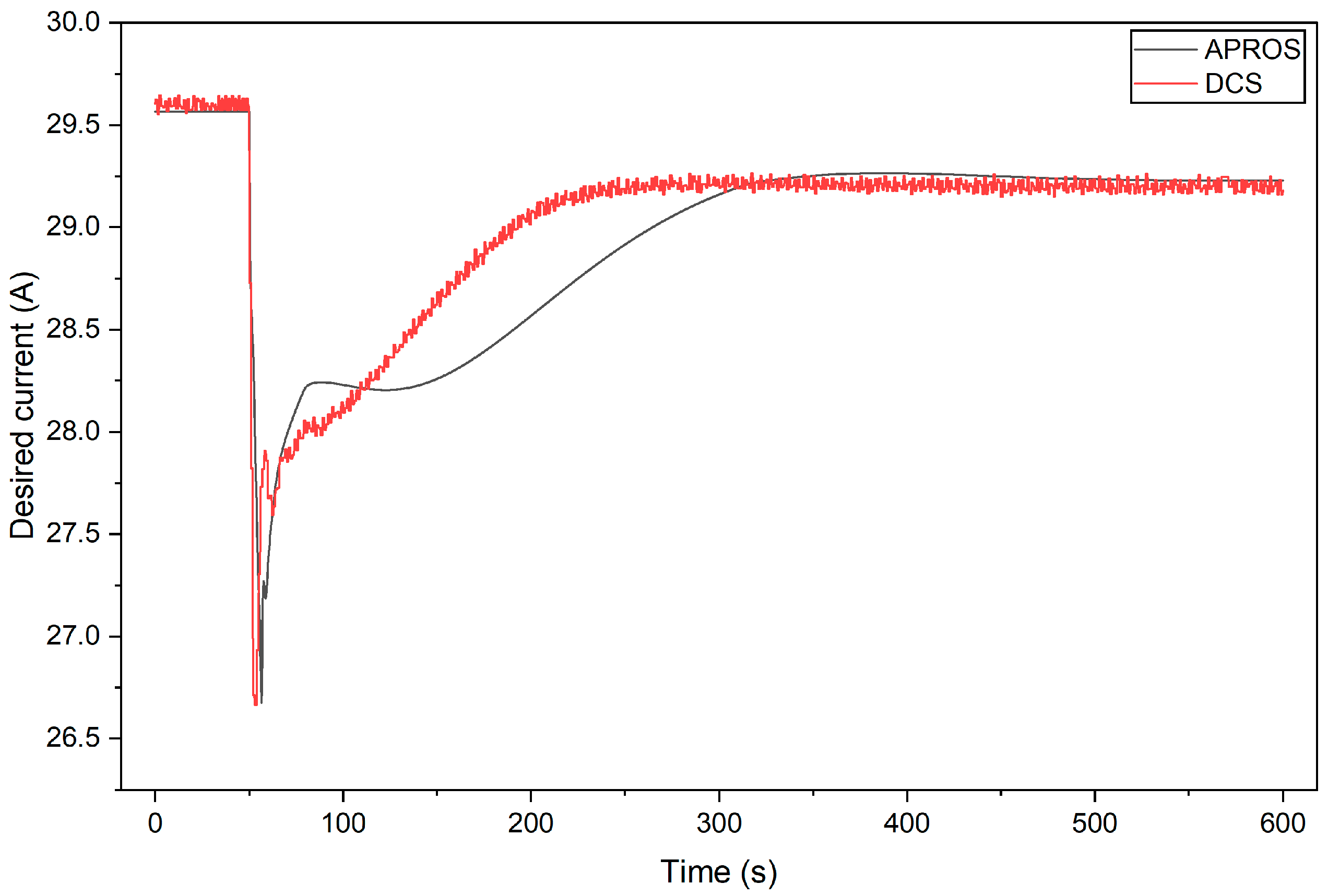

5.1. Total Power Turndown

5.2. Fuel Utilization Turndown

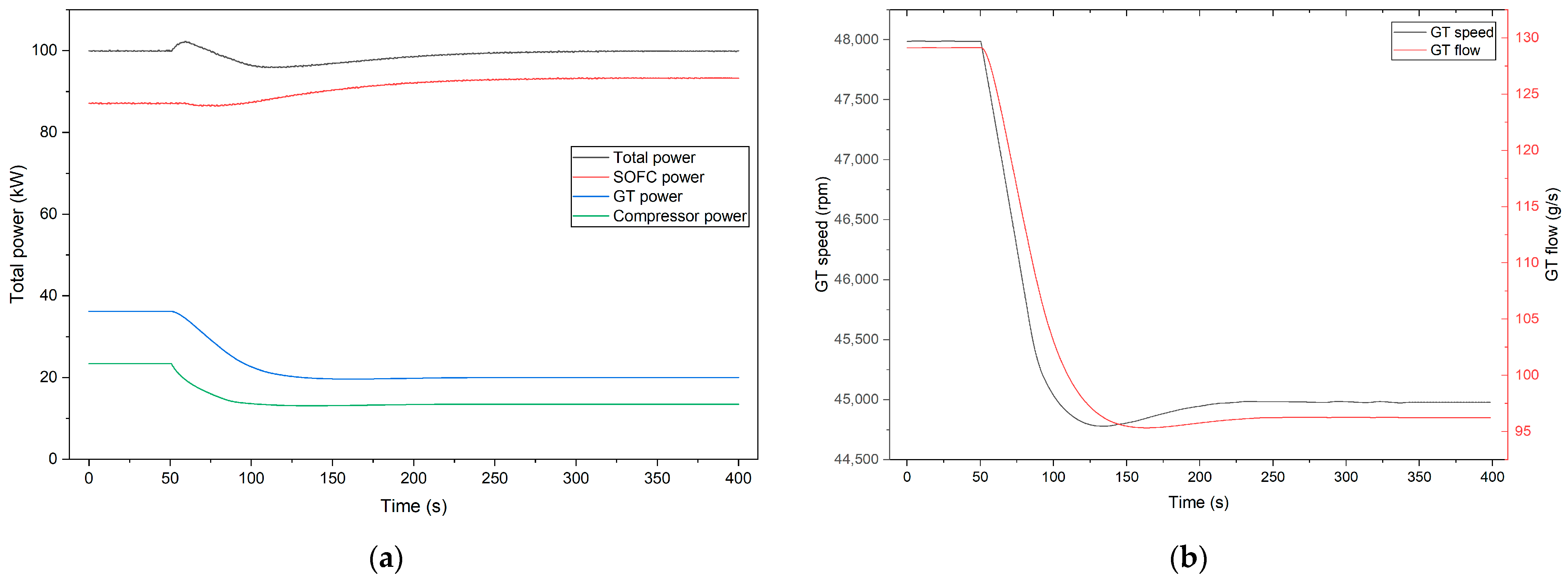

5.3. GT Speed Ramp-Down

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The C-HILS method proposed in this paper enables the coordinated operation of virtual generator sets and physical distributed control systems (DCS), accomplishing the dual objectives of control system verification and unit online virtual simulation. This method not only facilitates the rapid development of control logic within the DCS but also allows for real-time online simulation by replacing the corresponding equipment in the C-HILS platform with the DCS of an actual power plant, thereby transmitting on-site DCS control signals to the simulation model.

- (2)

- The proposed data signal acquisition and conversion platform can simulate real measurement and control signals. For research on the C-HILS, the signal conversion center built using NI virtual instrument equipment in this study serves as a valuable reference for rapidly constructing experimental platforms.

- (3)

- As a reliable verification and development platform for the digitization of energy and power systems, the proposed C-HILS scheme not only provides a high-fidelity testing environment for the control strategy optimization of SOFC-GT hybrid systems but also exhibits strong scalability and adaptability. It can be flexibly migrated to other energy systems (e.g., wind-solar hybrid power plants, hydrogen energy storage systems) by adjusting model parameters and signal conversion protocols, supporting the validation of digital solutions and advanced control algorithms for diverse energy scenarios.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |

| APROS | Advanced Process Simulation Software |

| ASR | Area-specific resistance |

| A/D | Analog-to-Digital |

| CFC | Continuous function chart |

| C-HILS | Controller hardware-in-the-loop simulation |

| DCOM | Distributed component object model |

| DCS | Distributed control system |

| D/A | Digital-to-Analog |

| FM | Function module |

| FU | Fuel utilization |

| GT | Gas turbine |

| HILS | Hardware-in-the-loop simulation |

| HMI | Human–machine interface |

| HOLLiAS | Hangzhou Hollysys Automation Co., Ltd. |

| I/O | Input and Output |

| LabVIEW | Laboratory Virtual Instrument Engineering Workbench |

| MACS | Management and Control System |

| NI | National Instruments |

| OPC | OLE for Process Control |

| OPC DA | OPC data access |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| POU | Program organization unit |

| PXI | PCI eXtensions for Instrumentation |

| SOFC | Solid oxide fuel cell |

| TD | Temperature difference |

| Parameters | |

| ) | |

| The first coefficient of the function defining ASR | |

| The second coefficient of the function defining ASR | |

| Empirical constant related to cathode, anode, and electrolyte resistivity | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| Empirical constant related to cathode, anode, and electrolyte resistivity | |

| ) | |

| Standard electromotive force (V) | |

| Nernst electromotive force (V) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| The Stodola coefficient | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| Electron transfer coefficient | |

| Rotational speed (rpm) | |

| Efficiency | |

| Pressure (Pa) | |

| Power (kW) | |

| Ratio of compressor outlet pressure to inlet pressure | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| The interconnector resistance of the fuel cell | |

| Temperature (K) | |

| ) | |

| Voltage (V) | |

| Subscripts | |

| Activation | |

| Additive | |

| Air | |

| Average | |

| Bulk | |

| Calculation | |

| Compressor | |

| A single SOFC | |

| Concentration | |

| Dynamic | |

| Fuel | |

| Generation | |

| Generator | |

| Gas turbine | |

| Heat Transfer | |

| Components (e.g., hydrogen, oxygen) | |

| Inlet | |

| Interconnector | |

| Limiting | |

| Nernst potential | |

| Ohmic | |

| Outlet | |

| Reaction site | |

| Steady-state | |

| Nominal/Optimal point/Stagnation | |

References

- Bao, C.; Wang, Y.; Feng, D.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X. Macroscopic modeling of solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) and model-based control of SOFC and gas turbine hybrid system. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 66, 83–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkandi, J.; Penhani, H.; Maroufi, A. Thermodynamic analysis of the performance of a hybrid system consisting of steam turbine, gas turbine and solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC-GT-ST). Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 213, 112816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Yao, E.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zou, H.; Xi, G. Thermo-economic analysis of a novel system integrating compressed air and thermochemical energy storage with solid oxide fuel cell-gas turbine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 252, 115114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Hsu, F.-T.; Chang, W.-C.; Hwang, J.-J.; Li, Z. Economic dispatch optimization of SOFC/GT-based cogeneration systems using flexible fuel purchasing strategy. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 130, 103832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, H.; Du, H.; Wang, H. Thermodynamic performance study of a novel cogeneration system combining solid oxide fuel cell, gas turbine, organic Rankine cycle with compressed air energy storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 249, 114837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.; Xu, S.; Zhu, H.; Wang, B.; Lei, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, X. Collaborative control for power and temperature tracking of the solid oxide fuel cell under maximum system efficiency. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liang, M.; Zhang, H.; Weng, S. Study on control strategy for a SOFC-GT hybrid system with anode and cathode recirculation loops. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 29422–29432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforakis, I.; Mamalis, S.; Assanis, D. Understanding Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Hybridization: A Critical Review. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, I.; Traverso, A.; Tucker, D. SOFC/Gas Turbine Hybrid System: A simplified framework for dynamic simulation. Appl. Energy 2019, 238, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H. Study on an adaptive multi-model predictive controller for the thermal management of a SOFC-GT hybrid system. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 414, 02013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lv, X.; Mi, X.; Spataru, C.; Weng, Y. Coordinated control approach for load following operation of SOFC-GT hybrid system. Energy 2022, 248, 123548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Maloney, D.; Farida Harun, N.; Zhou, N.; Pezzini, P.; Medam, A.; Hovsapian, R.; Bayham, S.; Tucker, D. Rapid load transition for integrated solid oxide fuel cell—Gas turbine (SOFC-GT) energy systems: A demonstration of the potential for grid response. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 258, 115544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mi, X.; Lv, X.; Weng, Y. Fast and stable operation approach of ship solid oxide fuel cell-gas turbine hybrid system under uncertain factors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 21472–21491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Semi-physical simulation and coordinated control of SOFC-PV/T-HP system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 240, 122251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, D.; Ma, L.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, N.; Hao, X. Research on Semi-physical Simulation of Direct Drive Fan Based on ADPSS. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2310, 012078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsugi, Y.; Hashiguchi, H.; Shigemasa, T.; Ota, Y.; Terazono, T.; Nakajima, T. Control Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation on Fast Frequency Response of Battery Energy Storage System Equipped with Advanced Frequency Detection Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 5541–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, B.; Wang, H. Hardware-in-the-loop real-time validation of fuel cell electric vehicle power system based on multi-stack fuel cell construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchur, I.; Shchur, V.; Bilyakovskyy, I.; Khai, M. Hardware in the loop simulative setup for testing the combined heat power generating wind turbine. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. (IJPEDS) 2021, 12, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himani, H.; Sharma, N. Hardware-in-the-loop simulator of wind turbine emulator using labview. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. (IJPEDS) 2019, 10, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rached, B.; Elharoussi, M.; Abdelmounim, E.; Bensaid, M. Design and DSP implementation in HIL of nonlinear observers for a doubly fed induction aero-generator. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2023, 12, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Mao, J.F.; Zhang, X. An ADRC-Based Hardware-in-the-Loop System for Maximum Power Point Tracking of a Wind Power Generation System. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 226119–226130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xue, Z. The Hardware in Loop Simulation System Design Based on PLC for the Process Control. In Chinese Intelligent Systems Conference; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Jin, C.; Wang, P. A Uniform Control Strategy for the Interlinking Converter in Hierarchical Controlled Hybrid AC/DC Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 65, 6188–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Huang, K.; Li, Y.; Yang, C. Digital twin for zinc roaster furnace based on knowledge-guided variable-mass thermodynamics: Modeling and application. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 173, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X. Construction of digital twin ecosystem for coal-fired generating units. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1748, 052037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, J.; Ramachandran, R.; Veerasamy, V.; Irudayaraj, A.X.R. Distributed leader-follower based adaptive consensus control for networked microgrids. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Sepulveda, M.A.; Harun, N.F.; Hackett, G.; Hagen, A.; Tucker, D. Accelerated Degradation for Hardware in the Loop Simulation of Fuel Cell-Gas Turbine Hybrid System. J. Fuel Cell Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, H.; Hernàndez-Torres, D.; Retière, C.; Garnier, L.; Poirot-Crouvezier, J.-P. X-in-the-Loop Methodology for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Systems Design: Review of Advances and Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachajdak, A.; Lappalainen, J.; Mikkonen, H. Dynamic simulation in development of contemporary energy systems—Oxy combustion case study. Energy 2019, 181, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkloff, R.; Alobaid, F.; Karner, K.; Epple, B.; Schmitz, M.; Boehm, F. Development and validation of a dynamic simulation model for a large coal-fired power plant. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 91, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications, V.; Puska, E.K.; Energy, V. Nuclear Reactor Core Modelling in Multifunctional Simulators; VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meriläinen, A.; Viljakainen, O.; Honkoila, K.; Lahtela, A. Apros-Based Loviisa NPP Full Scope Training Simulator and Engineering Model. In Proceedings of the 2021 28th International Conference on Nuclear Engineering, Anaheim, CA, USA, 4–6 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peltoniemi, J.; Karhela, T.A.; Paljakka, M. Performance Evaluation of OPC-Based I/O of a Dynamic Process Simulator; Society for Modeling and Simulation International: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T. Hardware Simulation of Fuel Cell/Gas Turbine Hybrids. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ollikainen, T.; Saarinen, J.; Halinen, M.; Hottinen, T.; Noponen, M.; Fontell, E.; Kiviaho, J. Dynamic Simulation Tool APROS in SOFC Power Plant Modeling at Wärtsilä and VTT. ECS Trans. 2007, 7, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaid, F.; Wieck, J.; Epple, B. Dynamic process simulation of a 780 MW combined cycle power plant during shutdown procedure. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC61131-3; Programmable Controllers—Part 3: Programming Languages. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

| Parameters | Unit | Design Value | Simulation Value | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOFC electrical power | kW | 98.00 | 97.53 | 0.48 |

| SOFC fuel utilization | % | 85.00 | 85.01 | 0.01 |

| SOFC electrical efficiency | % | 62.00 | 62.11 | 0.18 |

| GT mechanical power | kW | 36.00 | 36.06 | 0.17 |

| GT efficiency | % | 85.00 | 85.07 | 0.08 |

| GT rotational speed | rpm | 48,000.00 | 48,000.01 | 0.00 |

| Compressor power consumption | kW | 24.00 | 23.58 | 1.75 |

| Generator output power | kW | 12.00 | 12.47 | 3.92 |

| Combustion chamber temperature | °C | 900.00 | 900.01 | 0.00 |

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Description of Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Width of a fuel channel | 2 | mm | The width of a fuel channel perpendicular to the fuel flow direction. |

| Height of a fuel channel | 2 | mm | The height of a fuel channel. |

| Width of an air channel | 2 | mm | The width of an air channel perpendicular to the fuel flow direction. |

| Height of an air channel | 2 | mm | The height of an air channel. |

| Number of fuel cells in one stack | 3600 | / | The number of fuel cells in one stack. |

| Number of parallel stacks | 1 | / | The number of parallel stacks. |

| Thickness of electrolyte | 2 × 10−4 | m | The thickness of the electrolyte. |

| Active surface area of one cell | 0.01 | m2 | The active surface area of one fuel cell. |

| Calculation mode of ASR | 1 | / | The calculation mode of the area-specific resistance. The calculation mode 1 is the theoretical electromotive force. |

| Function used to calculate ASR | 4 | / | The function defines the calculation of the area-specific resistance. |

| Coefficient ALFA | 0.61 | / | The first coefficient of the function defining ASR. |

| Coefficient BETA | 0.79 | / | The second coefficient of the function defining ASR. |

| PID Controller Name | Controller Gain | Integration Time (s) | Derivation Time (s) | Derivation Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total power control | 0.003 | 18 | 10 | 0.5 |

| Fuel utilization control | 15 | 20 | 40 | 0.3 |

| GT Speed control | −0.005 | 35 | 8 | 0.5 |

| Point Name | Point Description | Upper Limit | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| FUEL_FLOW_INLET | Fuel inlet flow rate of SOFC | 0.01 | kg/s |

| AIR_FLOW_INLET | Air inlet flow rate of SOFC | 1.00 | kg/s |

| FUEL_TEMPER_INLET | Fuel inlet temperature of SOFC | 1000.00 | °C |

| AIR_TEMPER_INLET | Air inlet temperature of SOFC | 1000.00 | °C |

| FUEL_TEMPER_OUTLET | Fuel outlet temperature of SOFC | 1000.00 | °C |

| AIR_TEMPER_OUTLET | Air outlet temperature of SOFC | 1000.00 | °C |

| MIX_TEMPERTURE | Temperature of the afterburner in SOFC | 1000.00 | °C |

| POWER_SOFC | Electric power of SOFC | 200.00 | kW |

| EFFICIENCY_SOFC | Electrical efficiency of SOFC | 1.00 | \ |

| FUEL_UTILIZATION | Fuel utilization of SOFC | 1.00 | \ |

| G_POWER | Mechanical power of the generator | 20.00 | kW |

| FULLPOWER | Total power of the hybrid system | 200.00 | kW |

| TURBINE_SPEED | Rotational speed of the gas turbine | 60,000.00 | rpm |

| Point Name | Point Description | Upper Limit | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel_Valve | Opening degree of the SOFC fuel inlet valve | 1.00 | \ |

| Desired_Current | Desired current of SOFC | 40 | A |

| Load | Active power of the LOAD module | 450 | kW |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H. Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of SOFC-GT Hybrid System. Energies 2025, 18, 6500. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246500

Liu Y, Yang C, Jiang H, Wang H. Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of SOFC-GT Hybrid System. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6500. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246500

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yuandong, Chen Yang, Hailin Jiang, and Huai Wang. 2025. "Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of SOFC-GT Hybrid System" Energies 18, no. 24: 6500. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246500

APA StyleLiu, Y., Yang, C., Jiang, H., & Wang, H. (2025). Controller Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of SOFC-GT Hybrid System. Energies, 18(24), 6500. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246500