Characterizing the Spatial Variability of Thermodynamic Properties for Heterogeneous Soft Rock Using Random Field Theory and Copula Statistical Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

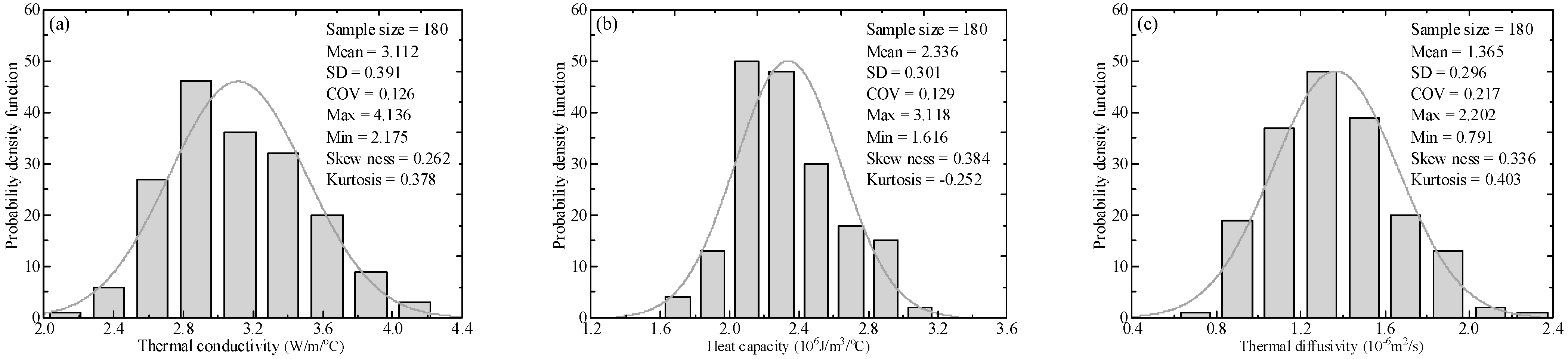

2.1. Thermodynamic Properties of Heterogeneous Soft Rock

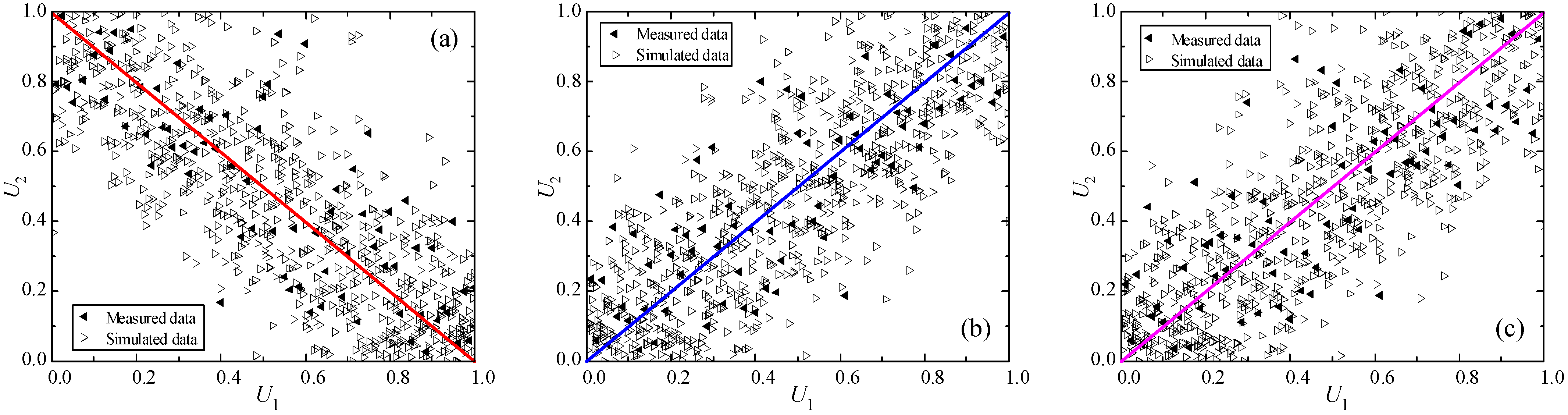

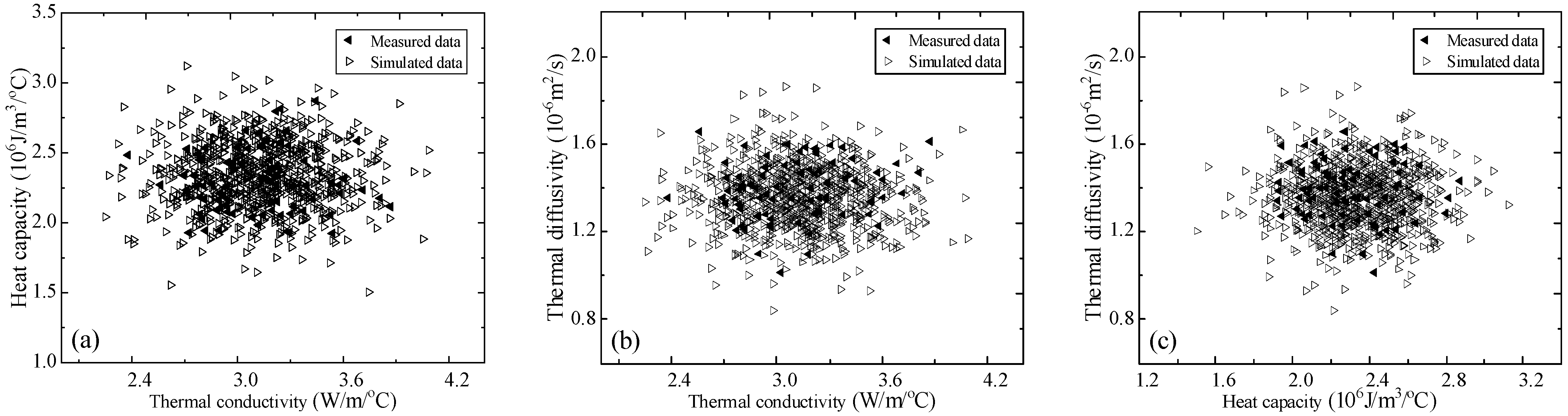

2.2. Copula Statistical Method for Thermodynamic Parameter Sample

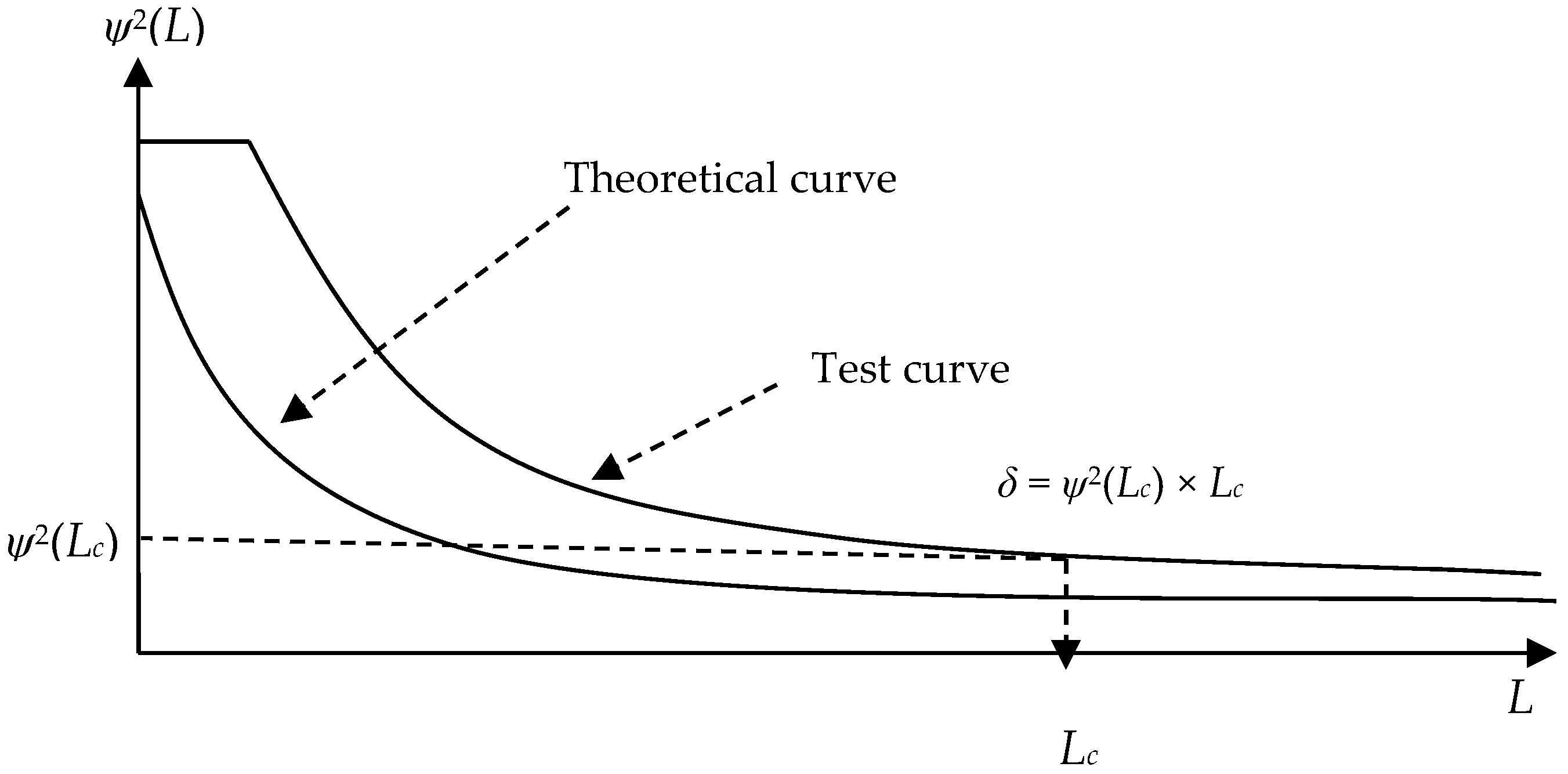

2.3. Random Field Characterization for Variable Thermodynamic Properties

3. Analysis Framework of Thermodynamic Variability Characteristic

3.1. Stability Point Analysis Process

3.2. Linear Regression Analysis Process

4. Results and Analyses

4.1. Verification of Characterization Method

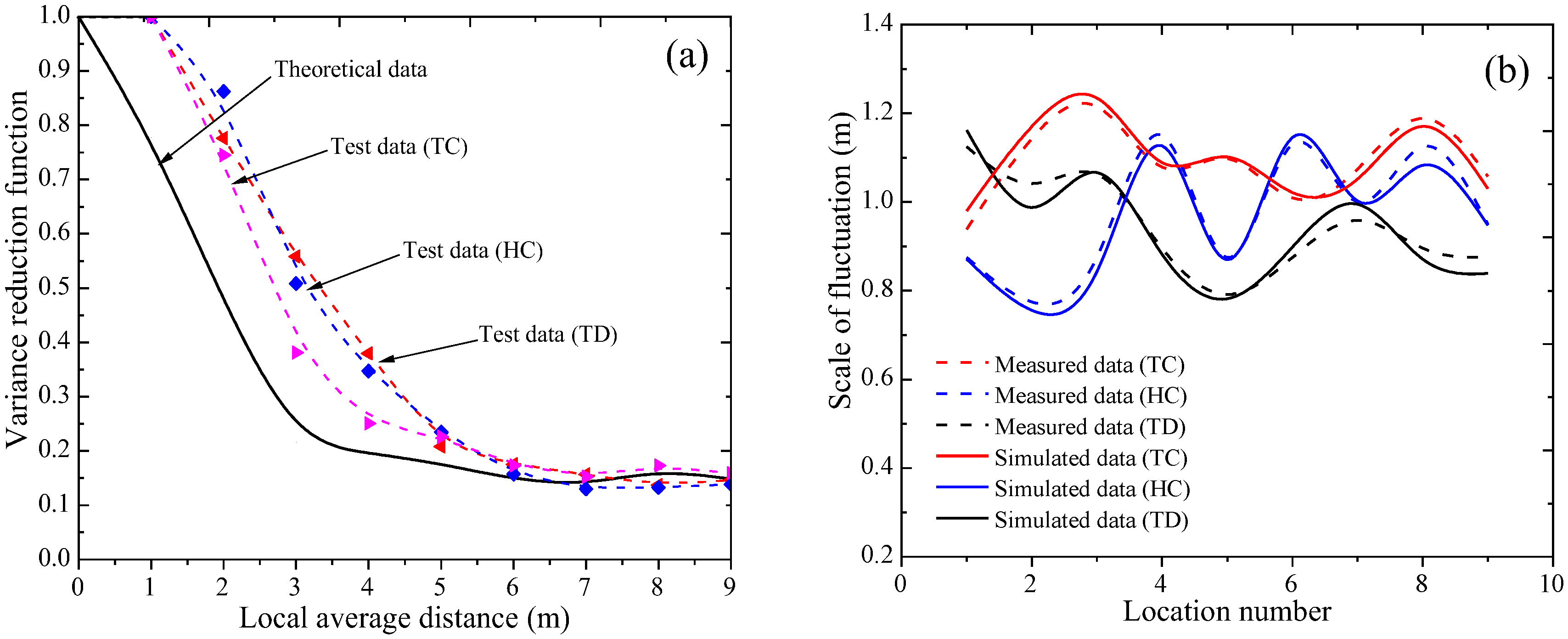

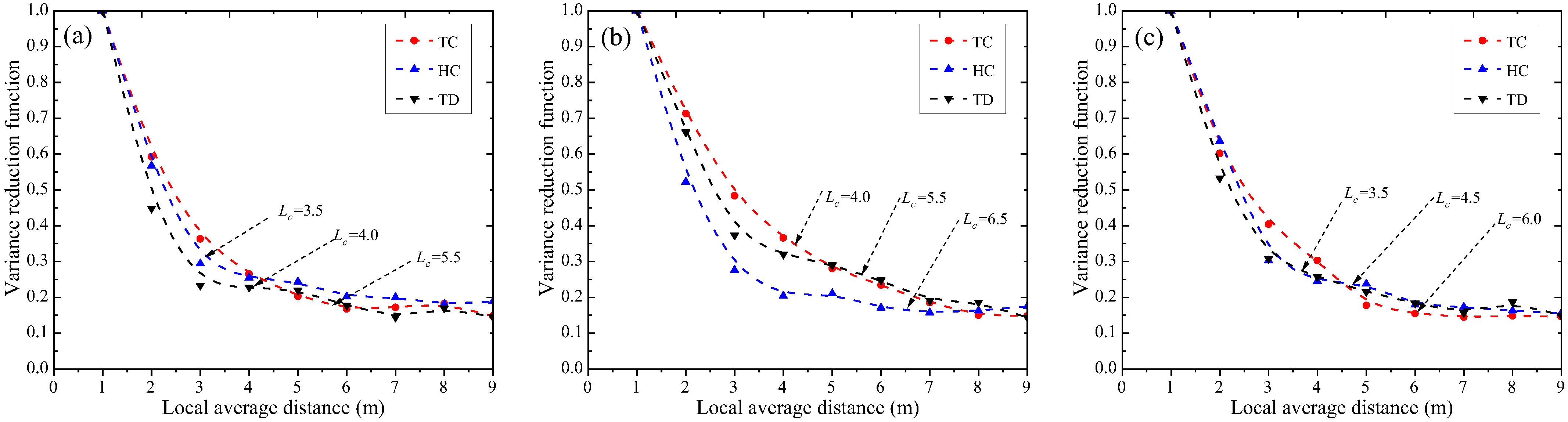

4.2. Variance Reduction Function

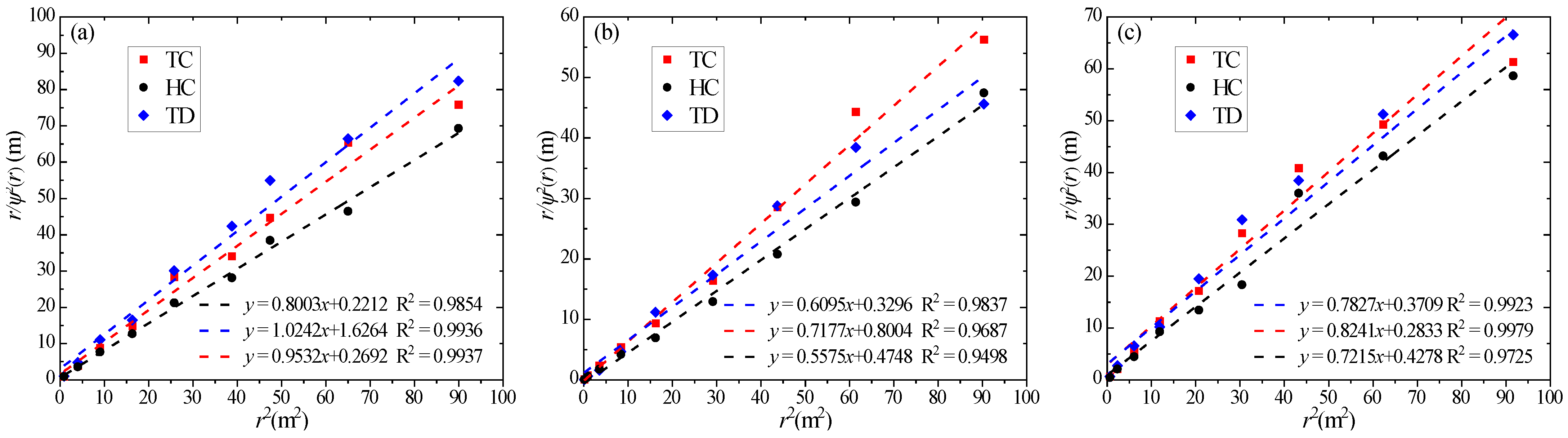

4.3. Scale of Fluctuation

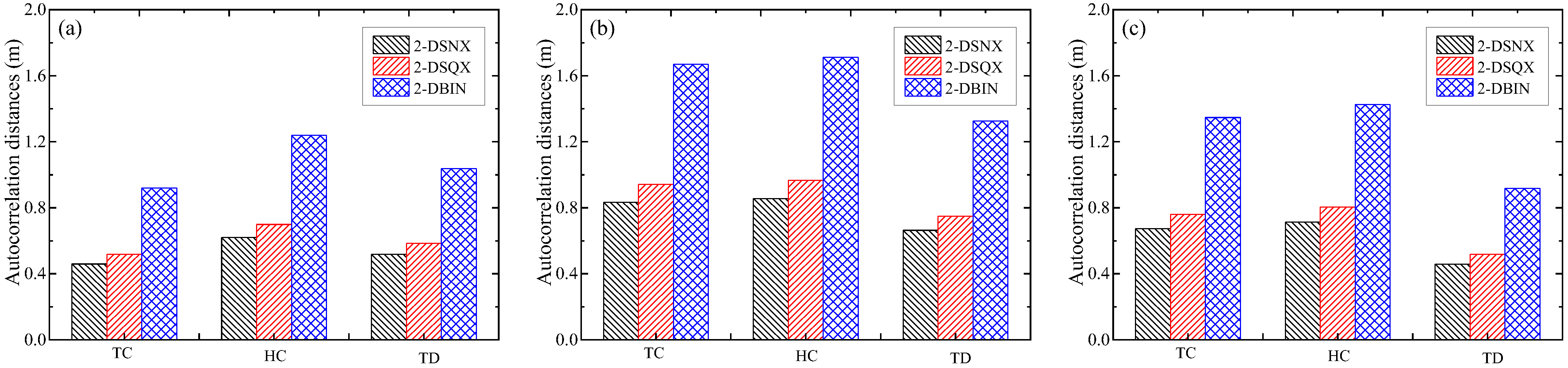

4.4. Autocorrelation Distances

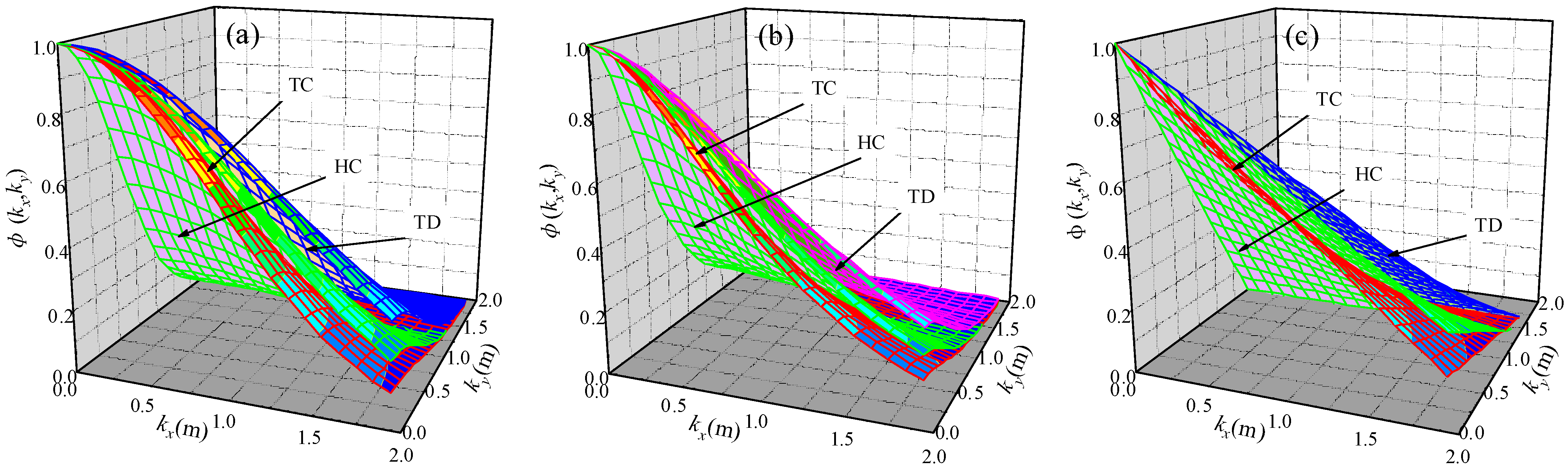

4.5. Autocorrelation Structure

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The Copula–Bootstrap method effectively constructs joint distributions for TC, HC, and TD from sparse data, decoupling marginal behaviors and dependency structures. By resampling and integrating Copula functions, it captures non-linear correlations and spatial heterogeneity overlooked by traditional methods. Validation via scatter plots and statistical metrics shows simulated data closely match measurements, with deviations under 5% in mean values.

- (2)

- Thermodynamic properties exhibit strong direction-dependent heterogeneity. Horizontal TC stabilizes fastest, while vertical HC/TD requires longer averaging distances, indicating stronger vertical spatial correlations. The 45° oblique direction shows intermediate values, blending horizontal and vertical influences. The VRF confirms anisotropic decay rates, with vertical VRF declining 30% slower than horizontal.

- (3)

- The 2-DBIN stochastic field consistently yields the longest autocorrelation distances, reflecting gradual spatial decay, while 2-DSNX shows the shortest. HC maintains 20% longer correlations than TC/TD due to sensitivity to mineral layering. Vertical orientations exhibit 25% larger autocorrelation scales than horizontal, aligning with tectonic fracture anisotropy. These model-specific differences underscore the need for calibrated covariance functions in simulating heat flow pathways.

- (4)

- VRF demonstrates close alignment between theoretical predictions and test data across TC, HC, and TD. Despite minor deviations, the consistent decay of VRF with increasing local average distance confirms the model’s ability to capture spatial heterogeneity. Similarly, SOF simulations replicate measured data trends, verifying the framework’s reliability for characterizing soft rock thermodynamic variability under limited-data constraints.

- (5)

- Autocorrelation decays slowest for HC under 2-DSQX, suggesting strong large-scale coherence, while TD declines steepest across models, indicating localized spatial correlations. TC exhibits broader correlation ranges in 2-DBIN than in 2-DSNX, revealing model-dependent representations of thermal conductivity heterogeneity. These structures emphasize that thermodynamic processes governed by HC involve slower energy transfer, whereas TD responds acutely to microscale changes, impacting geothermal reservoir design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, X.; Meng, T.; Ma, L.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Liu, P.; Cui, S. Experimental study on triaxial mechanical properties and energy conversion characteristics of salt rock under thermo-mechanical loading: Implication for underground energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafin, S. Thermophysical properties of reservoir rocks. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 129, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Rong, G.; Chen, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z. Experimental evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of geothermal reservoir rock after different cooling treatments. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 4967–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Dong, W.; Li, H.; Guo, B. Experimental comparison of mechanical properties and fractal characteristics of geothermal reservoir rocks after different cooling treatments. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 5158–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.S.; Wang, X.W.; Shen, S.L.; Zhou, A. Distribution characteristics and utilization of shallow geothermal energy in China. Energy Build. 2020, 229, 110479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Kang, Y. Experimental investigation of thermal cycling effect on fracture characteristics of granite in a geothermal-energy reservoir. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2020, 235, 107180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, F.; Dong, Z.; Li, H.; Shi, X.; Xu, Z.; Meng, X.; Yang, C. Study on the influence of temperature on the damage evolution of hot dry rock in the development of geothermal resources. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 241, 213171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Li, X. Geothermal energy for sustainable and green energy supply in the future. Deep Undergr. Sci. Eng. 2024, 3, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Noval, C.; Álvarez, R.; García-Cortés, S.; García, C.; Alberquilla, F.; Ordóñez, A. Definition of a thermal conductivity map for geothermal purposes. Geotherm. Energy 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, M.C.; Kolawole, O.; Olorode, O. Geothermo-mechanical alterations due to heat energy extraction in enhanced geothermal systems: Overview and prospective directions. Deep Undergr. Sci. Eng. 2024, 3, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Cui, M.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Huo, J.; Yin, Y. Rapid Temperature Prediction Model for Large-Scale Seasonal Borehole Thermal Energy Storage Unit. Energies 2025, 18, 5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Guo, F.; Yang, X. An inversion method to estimate the thermal properties of heterogeneous soil for a large-scale borehole thermal energy storage system. Energy Build. 2022, 263, 112045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lin, H.; Ren, K.; Gao, J.; Wang, D. Sensitivity Analysis of Different Hydrothermal Characteristics in the Variable Thermodynamic Processes of Soft Clay Rock. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, A.A.; Rogers, A.D.; Edwards, C.S.; Piqueux, S. Thermophysical properties and surface heterogeneity of landing sites on mars from overlapping thermal emission imaging system (THEMIS) Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2021, 126, e2020JE006713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Numerical simulation of geothermal reservoir thermal recovery of heterogeneous discrete fracture network-rock matrix system. Energy 2024, 305, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plúa, C.; Vu, M.-N.; Seyedi, D.M.; Armand, G. Effects of inherent spatial variability of rock properties on the thermo-hydro-mechanical responses of a high-level radioactive waste repository. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 145, 104682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Long, H.; Chen, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, J.; Cheng, W. A Thermo-Mechanical Coupled Gradient Damage Model for Heterogeneous Rocks Based on the Weibull Distribution. Energies 2025, 18, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.Q.; Chen, Q.M.; Chen, G. Scale dependency of anisotropic thermal conductivity of heterogeneous geomaterials. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tao, M.; Fei, W.; Yin, T.; Ranjith, P.G. Grain-based coupled thermo-mechanical modeling for stressed heterogeneous granite under thermal shock. Undergr. Space 2025, 20, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; He, J.; Gao, L.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, Z. LWIR hyperspectral image classification based on a tempera-ture-emissivity residual network and conditional random field model. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 3744–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Li, P.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y. Modeling seepage flow and spatial variability of soil thermal conductivity during artificial ground freezing for tunnel excavation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricketts, E.J.; Cleall, P.J.; Jefferson, A.; Kerfriden, P.; Lyons, P. Representation of three-dimensional unsaturated flow in heterogeneous soil through tractable Gaussian random fields. Géotechnique 2024, 74, 1868–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Zhou, X.; Ling, T. Novel cooling–solidification annealing reconstruction of rock models. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 1785–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.S.; Phan, T.N.; Likitlersuang, S.; Bergado, D.T. Characterization of stationary and nonstationary random fields with different copulas on undrained shear strength of soils: Probabilistic analysis of embankment stability on soft ground. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04022109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, T.; Sheng, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, G. A Copula method for modeling the intensity characteristic of geotechnical strata of roof based on small sample test data. Geomech. Eng. 2024, 36, 601–618. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, K.; Tang, D.; Hu, B.; Kelata, Y. Spatial random fields-based Bayesian method for calibrating ge-otechnical parameters with ground surface settlements induced by shield tunneling. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 1503–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, S.; Gao, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M. Stochastic Risk Assessment Framework of Deep Shale Reservoirs by a Deep Learning Method and Random Field Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Xie, L.; Qin, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, G. Study on strength characteristics of soft and hard rock masses based on thermal-mechanical coupling. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 963434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasheen, E.S.R.; Rashwan, M.A.; Azer, M.K. Effect of mineralogical variations on physico-mechanical and thermal properties of granitic rocks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Chang, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Cai, N.; Fan, L. Responses of multi-scale microstructures, physical-mechanical and hydraulic characteristics of roof rocks caused by the supercritical CO2-water-rock reaction. Energy 2022, 238, 121727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, L.; Lin, J. Analysis of physico-mechanical properties and pore structure characteristics of thermally damaged sandstone. Deep Resour. Eng. 2025, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, T.; Feng, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Correlation Characterization Method for Thermal Parameters of Frozen Soil Under Incomplete Probability Information. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2025, 49, 2003–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Reheman, Y.; Wang, X.; Fei, K.; Zhou, J.; Jiao, D. Failure probability analysis of high fill levee considering multiple uncertainties and correlated failure modes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Fan, Y.; Li, C.; Zhan, H.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.; Du, Z. A Bayesian bootstrap-Copula coupled method for slope reliability analysis considering bivariate distribution of shear strength parameters. Landslides 2024, 21, 2557–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrina-Teatino, M.A.; Araujo, J.J.M.; Mamani-Quispe, J.N.; Arango-Retamozo, S.M.; Gonzalez-Vasquez, J.A.; Vega-Gonzalez, J.A. Mineral resource estimation using spatial copulas and machine learning optimized with metaheuristics in a copper deposit. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhou, S.; Zhuang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wu, R. Phase-Field Modeling of a Single Horizontal Fluid-Driven Fracture Propagation in Spatially Variable Rock Mass. Int. J. Comput. Methods 2022, 19, 2142003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Zhang, D.-M.; Huang, H.W.; Phoon, K.K.; Tang, C.; Li, G. Hybrid machine learning model with random field and limited CPT data to quantify horizontal scale of fluctuation of soil spatial variability. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar]

| NO. | Density (g/cm3) | Dry Density (g/cm3) | Moisture Content (%) | Hydraulic Conductivity (10−6 cm/s) | Porosity (%) | Void Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 2.506 | 2.369 | 5.802 | 21.766 | 0.748 | 0.428 |

| 2# | 2.464 | 2.332 | 5.684 | 18.783 | 0.682 | 0.405 |

| 3# | 2.688 | 2.547 | 5.529 | 11.620 | 0.768 | 0.434 |

| 4# | 2.788 | 2.649 | 5.242 | 20.337 | 0.784 | 0.439 |

| 5# | 2.405 | 2.271 | 5.884 | 9.484 | 0.688 | 0.408 |

| 6# | 2.168 | 2.061 | 5.164 | 16.814 | 0.746 | 0.427 |

| 7# | 2.537 | 2.411 | 5.220 | 16.069 | 0.653 | 0.395 |

| 8# | 2.571 | 2.446 | 5.107 | 26.961 | 0.646 | 0.393 |

| 9# | 2.652 | 2.520 | 5.234 | 22.877 | 0.567 | 0.362 |

| Copula | C(u1,u2; θ) | D(u1,u2; θ) | Range of θ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | [−1, 1] | ||

| Frank | |||

| Gumbel |

| Statistics | Measured Data | Simulated Data | Comparative Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC W/m/°C | HC | TD | TC | HC | TD | TC | HC | TD | |

| Mean | 3.112 | 2.336 | 1.365 | 3.110 | 2.346 | 1.378 | 0.002 | −0.010 | −0.013 |

| SD | 0.391 | 0.301 | 0.296 | 0.335 | 0.256 | 0.136 | 0.056 | 0.045 | 0.160 |

| COV | 0.126 | 0.129 | 0.217 | 0.108 | 0.109 | 0.198 | 0.018 | 0.020 | 0.019 |

| Max | 4.136 | 3.118 | 2.202 | 4.052 | 3.047 | 1.861 | 0.084 | 0.071 | 0.341 |

| Min | 2.175 | 1.616 | 0.791 | 2.141 | 1.555 | 0.821 | 0.034 | 0.061 | −0.030 |

| Skewness | 0.262 | 0.384 | 0.336 | 0.246 | 0.324 | 0.289 | 0.016 | 0.060 | 0.047 |

| Peakedness | −0.378 | −0.252 | −0.403 | −0.373 | −0.231 | −0.423 | −0.005 | −0.021 | 0.020 |

| Function Type | Mathematical Expression | Relationship Between Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 2-DSNX | ||

| 2-DSQX | ||

| 2-DBIN |

| Length | Statistical Data Analysis Process | Variance | VRF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔL | … | DE1 | ||||||

| 2ΔL | … | DE2 | ||||||

| 3ΔL | … | DE3 | ||||||

| 4ΔL | … | DE4 | ||||||

| … | … | … | … | … | ||||

| mΔL | … | DEm | ||||||

| NO. | Horizontal Direction | Vertical Direction | Oblique Direction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | HC | TD | TC | HC | TD | TC | HC | TD | |

| 1# | 1.049 | 1.250 | 0.977 | 1.395 | 1.795 | 1.642 | 0.924 | 1.387 | 1.277 |

| 2# | 1.006 | 1.197 | 0.948 | 1.243 | 1.738 | 1.555 | 0.964 | 1.305 | 1.208 |

| 3# | 1.092 | 1.304 | 0.961 | 1.261 | 1.797 | 1.596 | 0.901 | 1.384 | 1.402 |

| 4# | 1.018 | 1.226 | 0.781 | 1.421 | 1.538 | 1.599 | 0.875 | 1.581 | 1.452 |

| 5# | 0.903 | 1.306 | 0.935 | 1.183 | 1.767 | 1.741 | 0.822 | 1.472 | 1.380 |

| 6# | 1.068 | 1.233 | 0.907 | 1.471 | 1.641 | 1.763 | 0.869 | 1.461 | 1.340 |

| 7# | 1.190 | 1.397 | 0.979 | 1.309 | 1.764 | 1.713 | 0.939 | 1.432 | 1.245 |

| 8# | 1.059 | 1.019 | 0.952 | 1.260 | 1.613 | 1.799 | 1.008 | 1.354 | 1.383 |

| 9# | 0.948 | 1.212 | 0.831 | 1.398 | 1.753 | 1.609 | 0.959 | 1.454 | 1.433 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Nie, W.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, G.; Xu, Y. Characterizing the Spatial Variability of Thermodynamic Properties for Heterogeneous Soft Rock Using Random Field Theory and Copula Statistical Method. Energies 2025, 18, 6499. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246499

Wang T, Nie W, Zeng X, Zhou G, Xu Y. Characterizing the Spatial Variability of Thermodynamic Properties for Heterogeneous Soft Rock Using Random Field Theory and Copula Statistical Method. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6499. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246499

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tao, Wen Nie, Xuemin Zeng, Guoqing Zhou, and Ying Xu. 2025. "Characterizing the Spatial Variability of Thermodynamic Properties for Heterogeneous Soft Rock Using Random Field Theory and Copula Statistical Method" Energies 18, no. 24: 6499. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246499

APA StyleWang, T., Nie, W., Zeng, X., Zhou, G., & Xu, Y. (2025). Characterizing the Spatial Variability of Thermodynamic Properties for Heterogeneous Soft Rock Using Random Field Theory and Copula Statistical Method. Energies, 18(24), 6499. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246499