Diagnosis of Cascaded Open/Short-Circuit Fault in Three-Phase Inverter Using Two-Stage Interval Sliding Mode Observer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fault Analysis and Modeling

2.1. Operating Status and Fault Analysis of Three-Phase Inverter

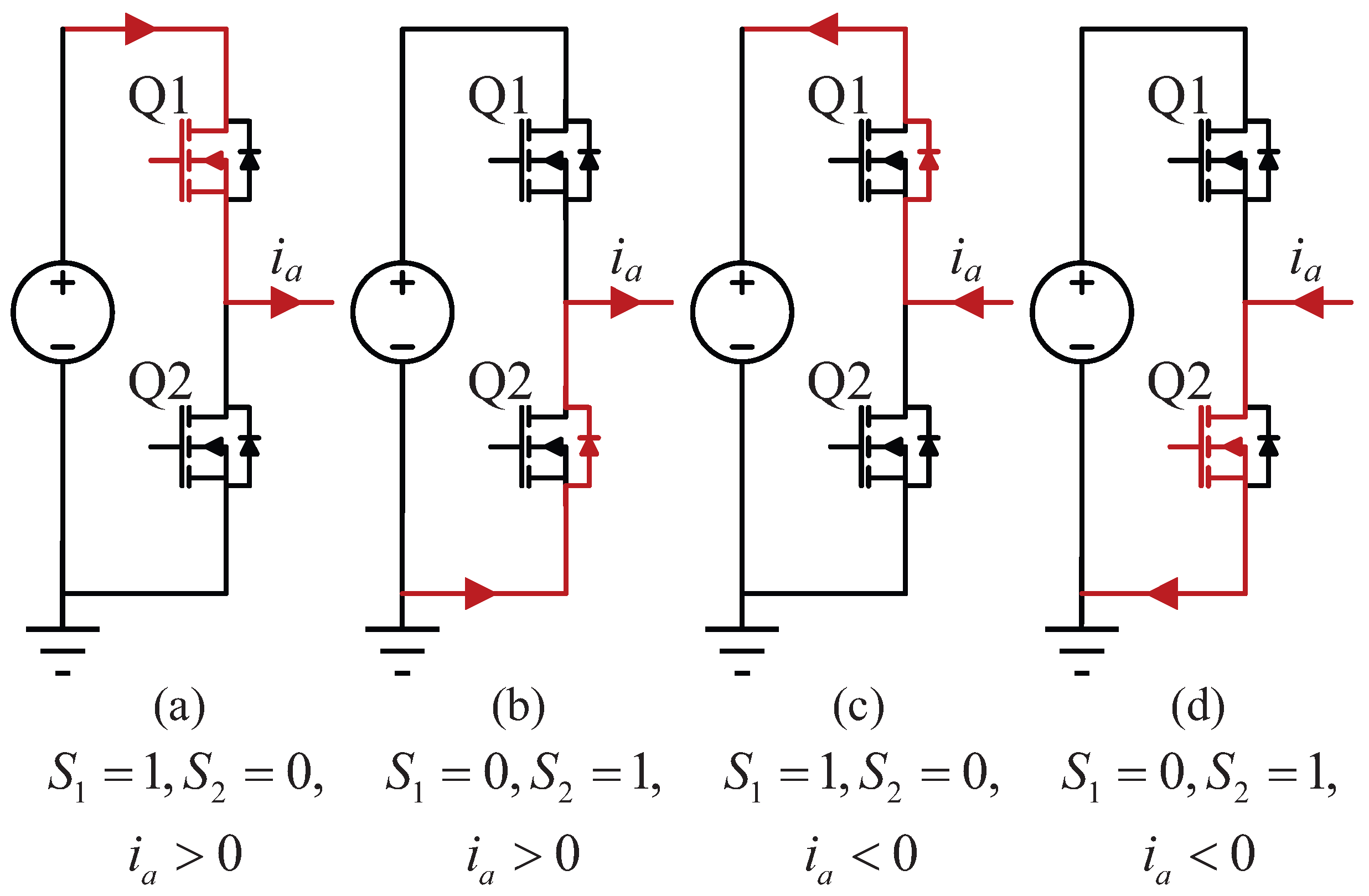

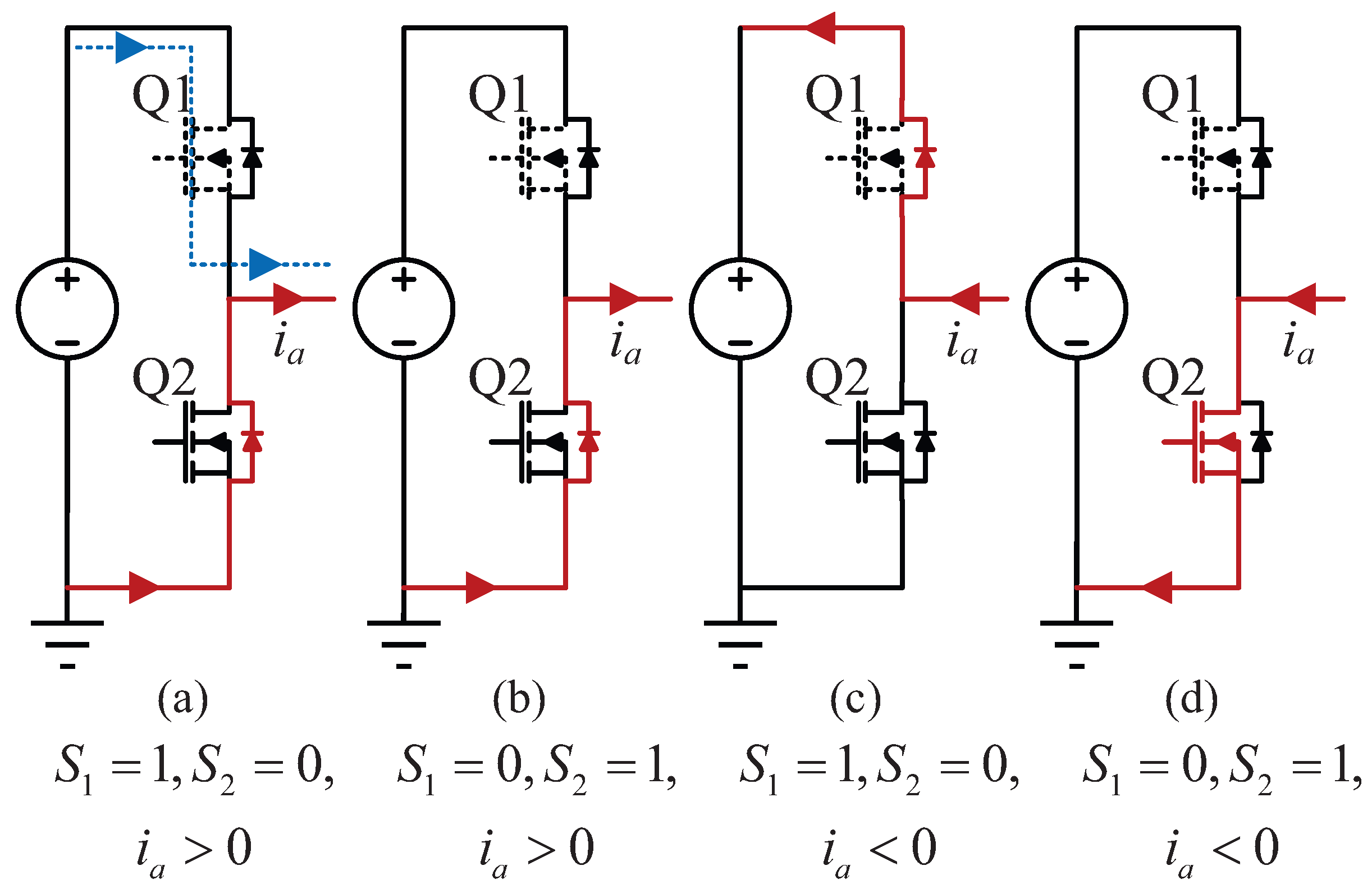

2.1.1. OC Fault Analysis

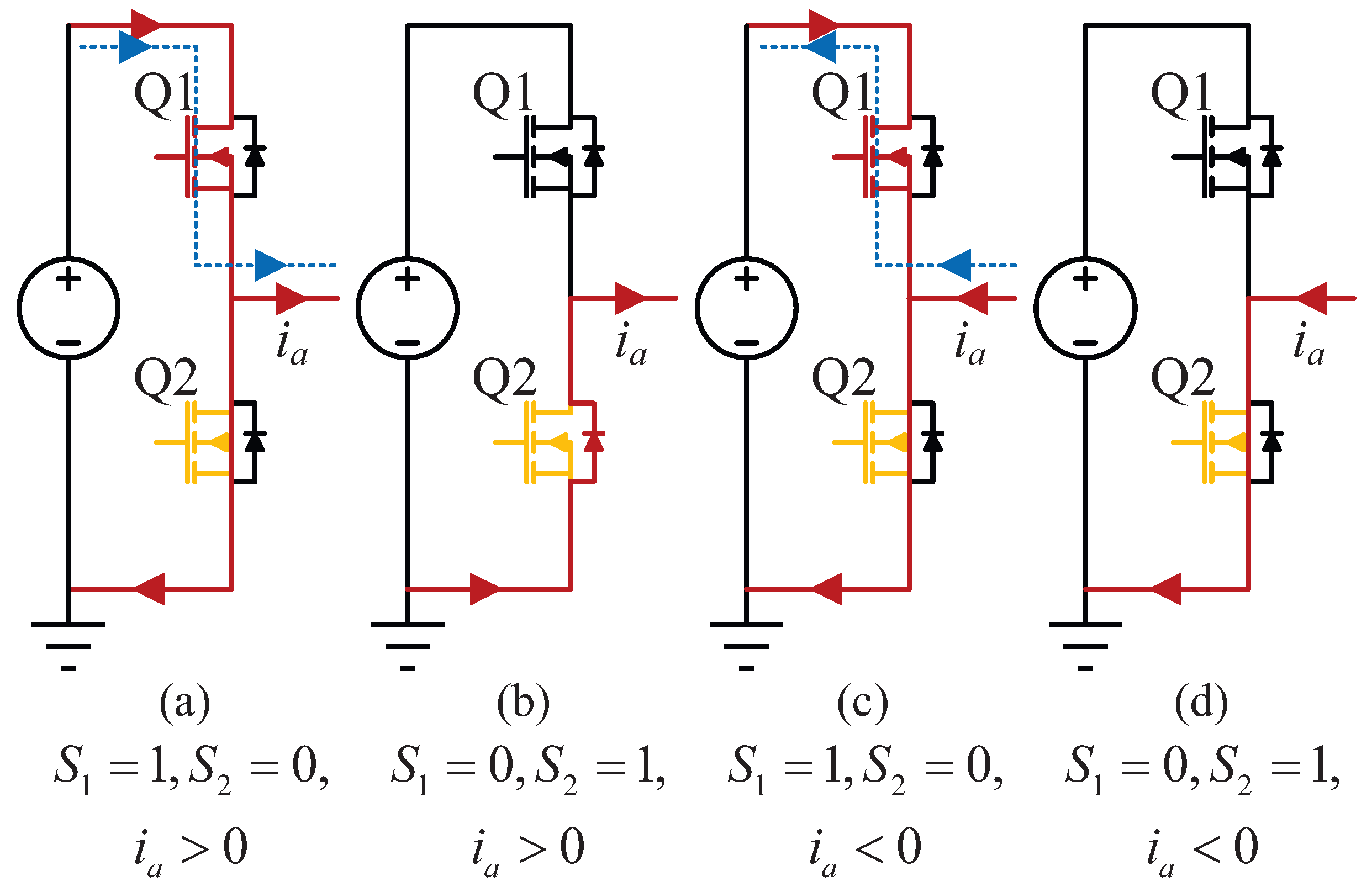

2.1.2. SC Fault Analysis

2.2. Modeling of Three-Phase Inverters Considering Faults

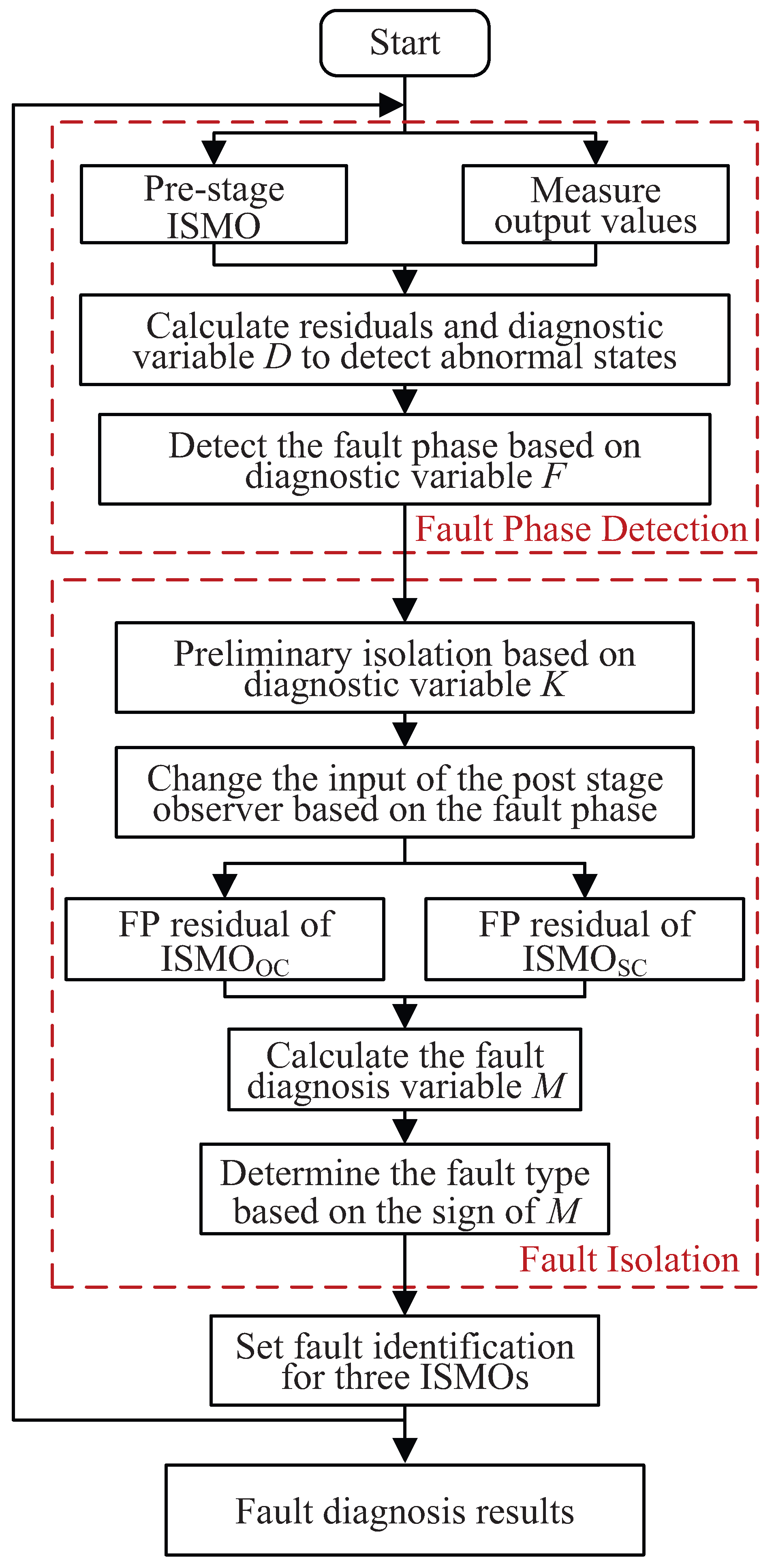

3. Fault Diagnosis Method

3.1. Design of Observer

- (1)

- is observable.

- (2)

- Matrix is Metzler matrix.

- (3)

- The input and the disturbance is positive at any time.

- (4)

- satisfies .

3.2. Fault Phase Detection Strategy

3.3. Fault Isolation Strategy

4. Simulation and Experiment Verification

4.1. Simulation Analysis

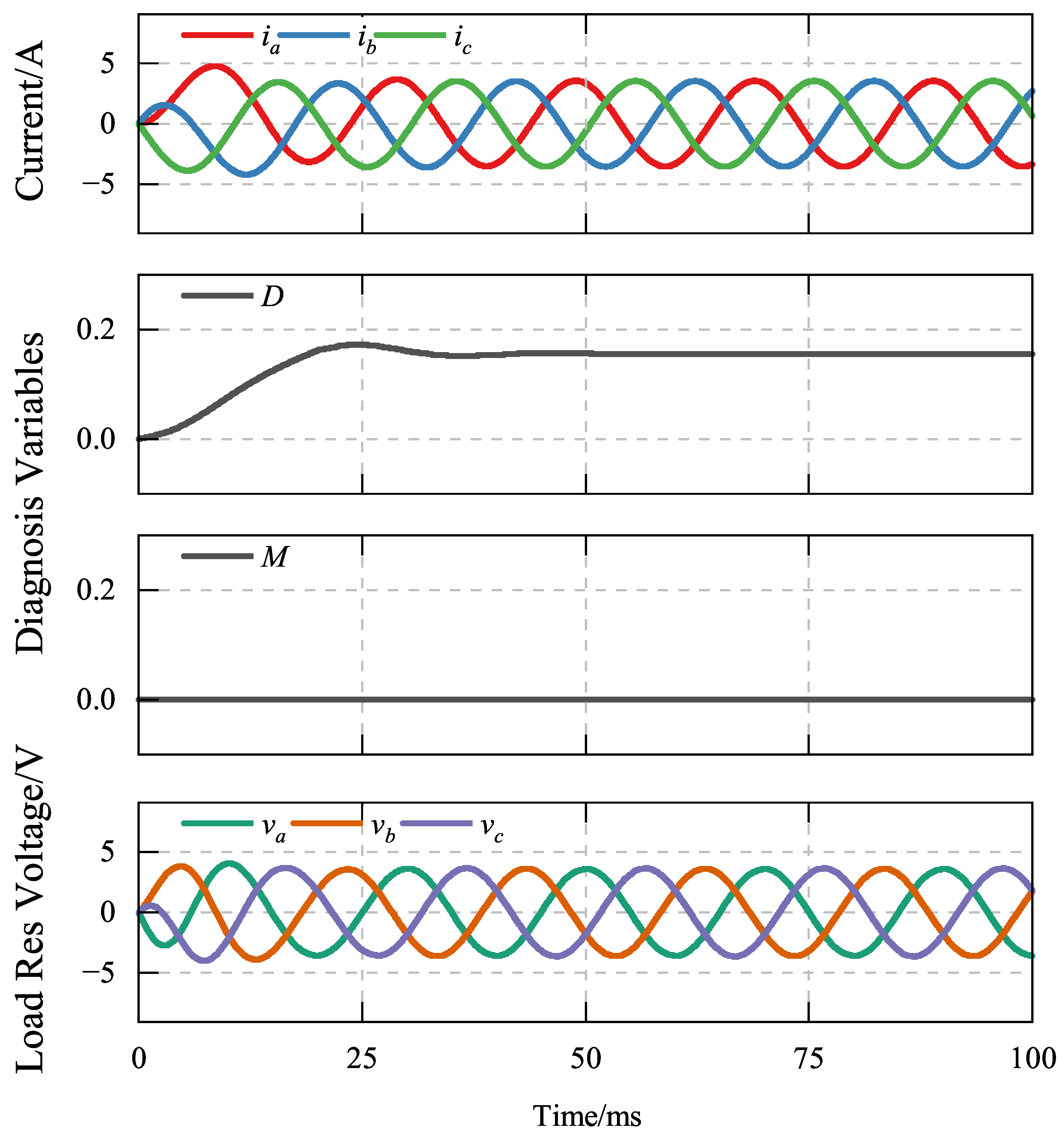

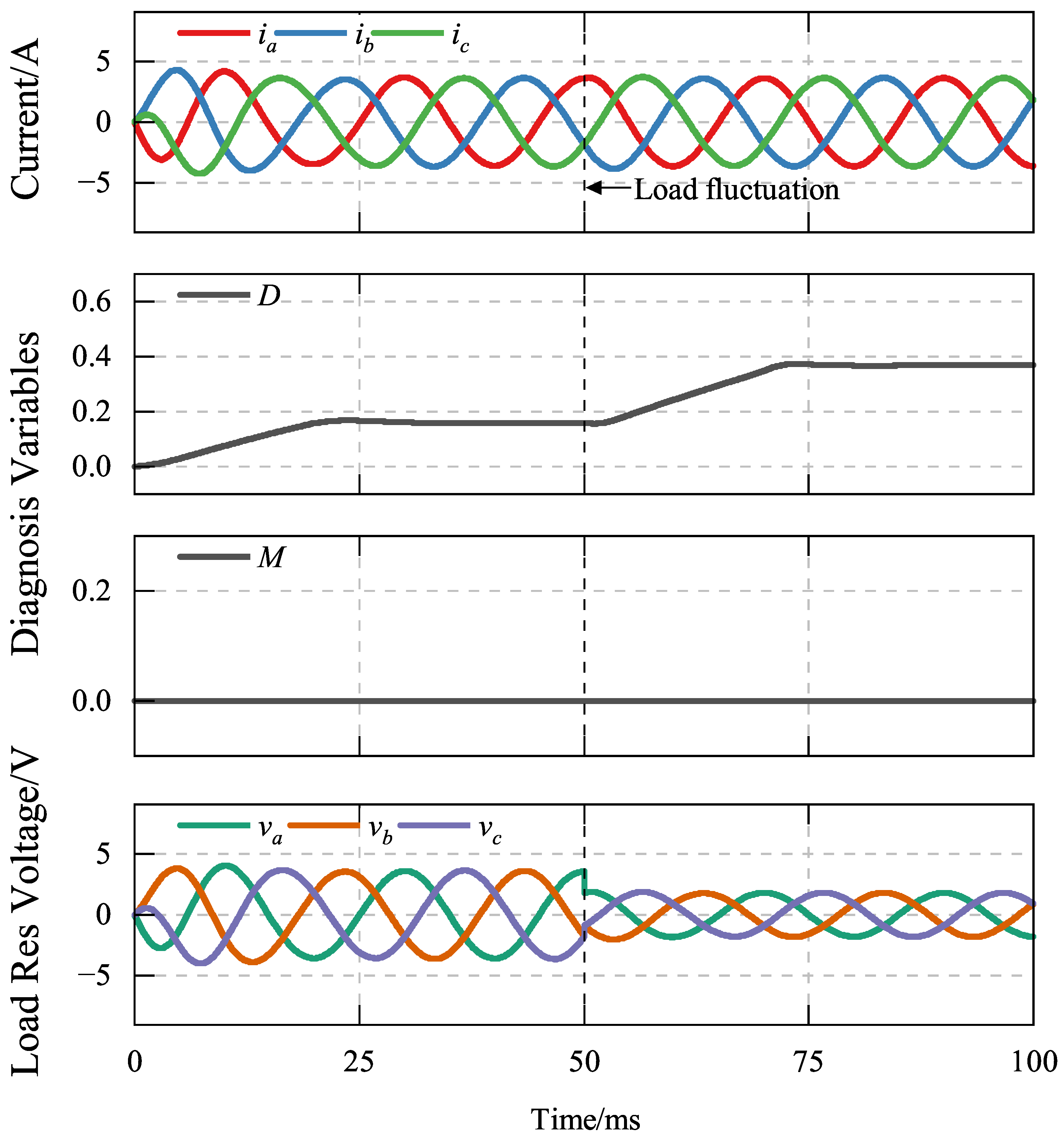

4.1.1. Robustness Verification

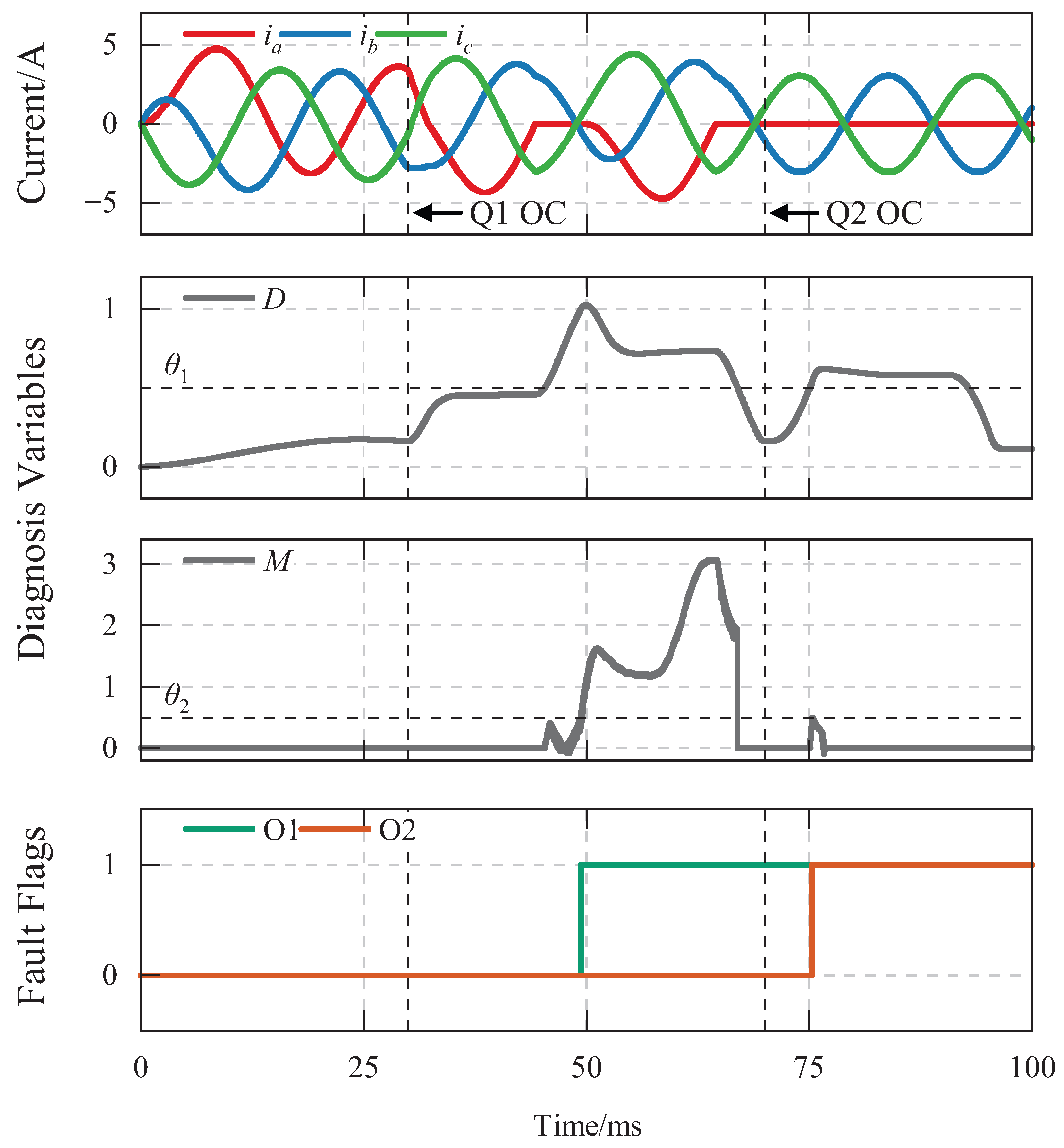

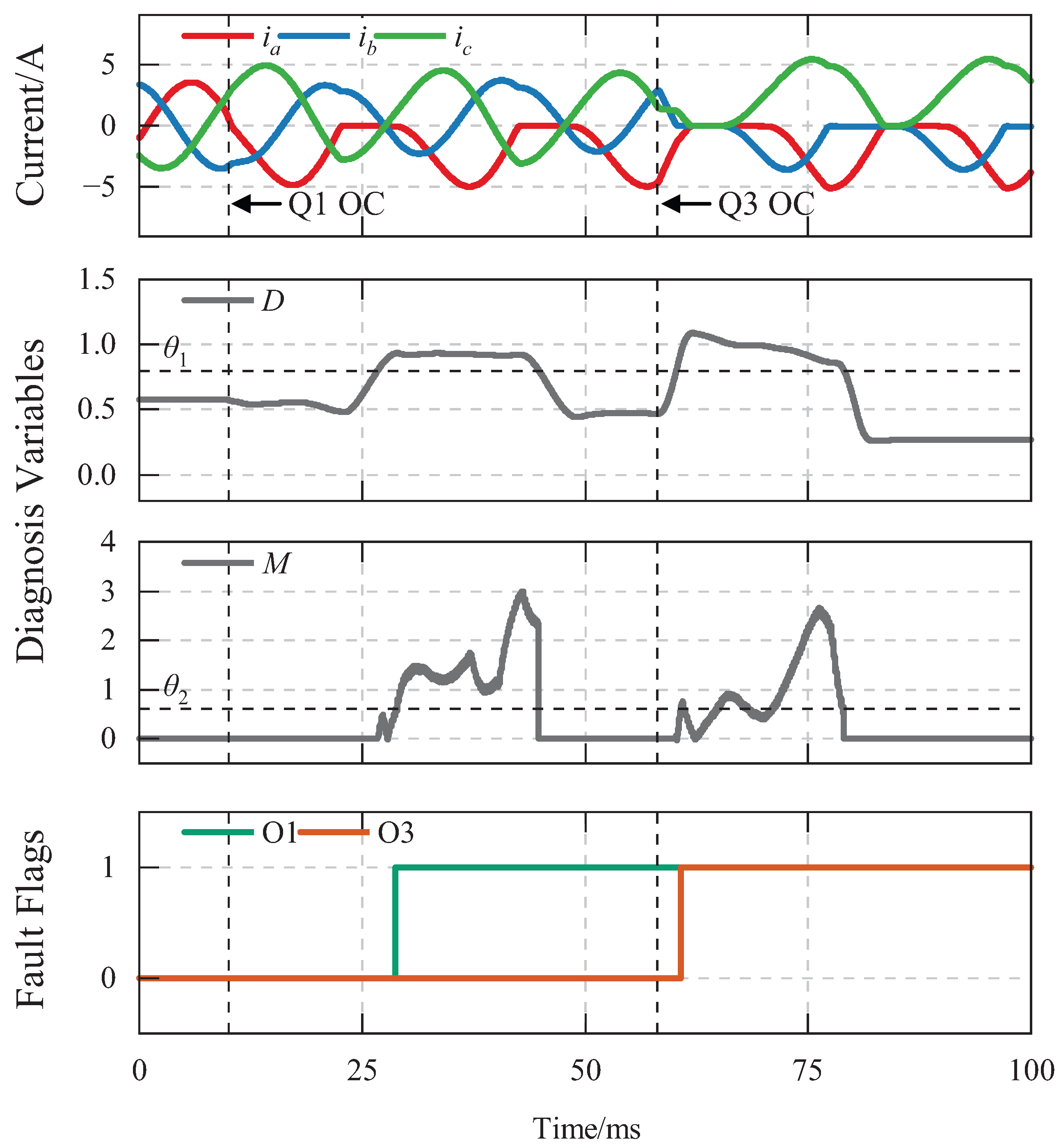

4.1.2. OC–OC Cascaded Fault Simulation

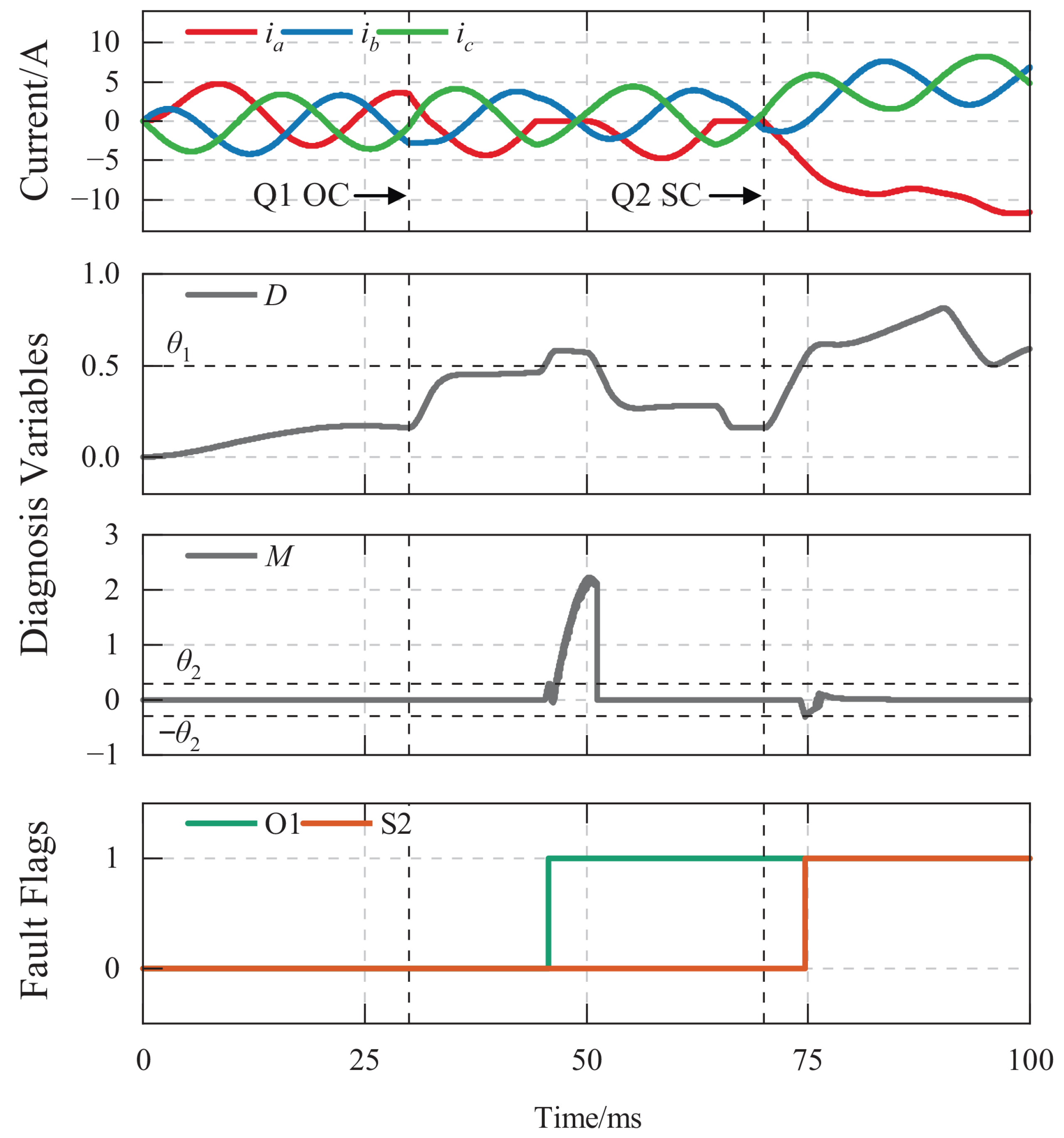

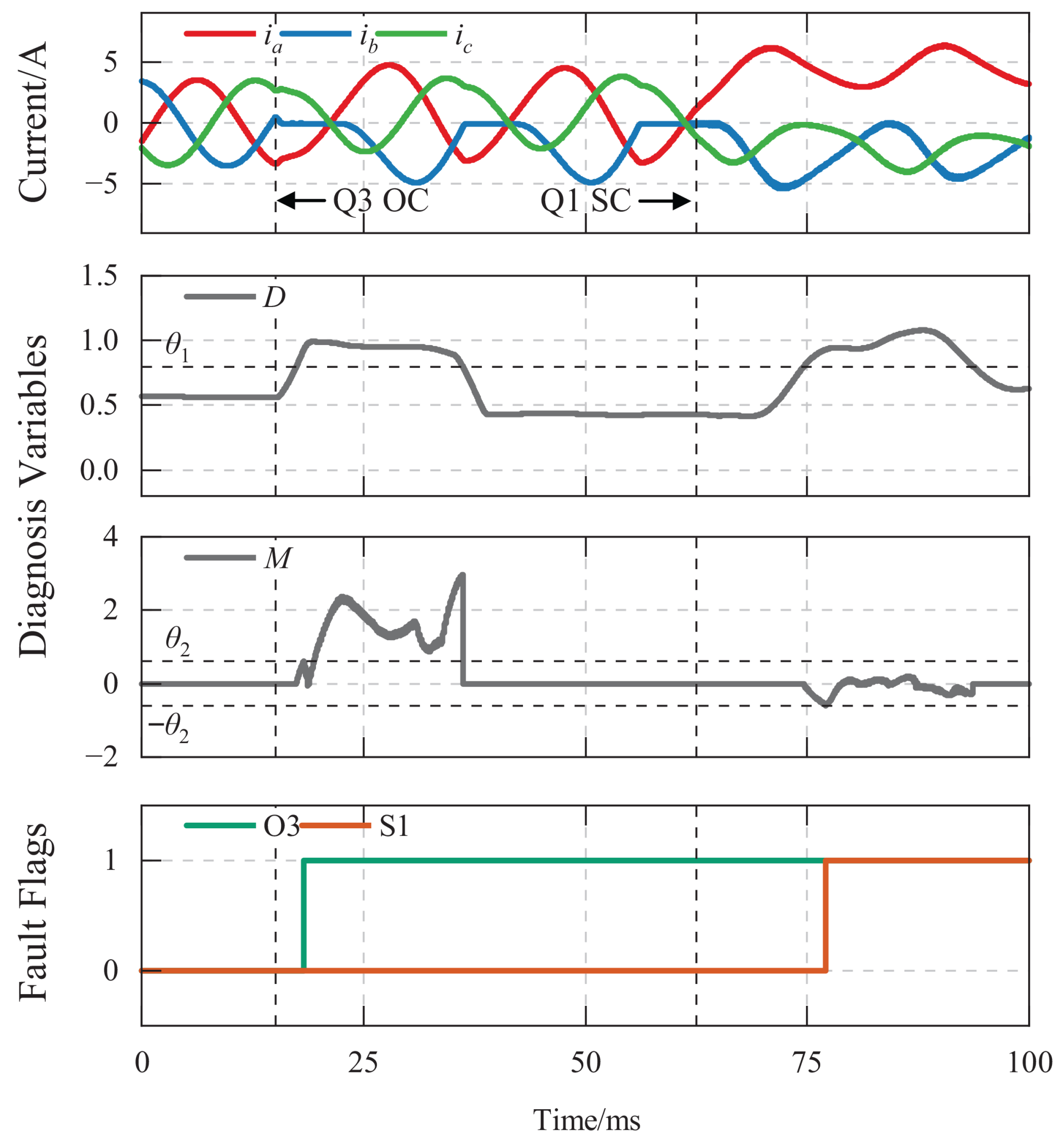

4.1.3. OC–SC Cascaded Fault Simulation

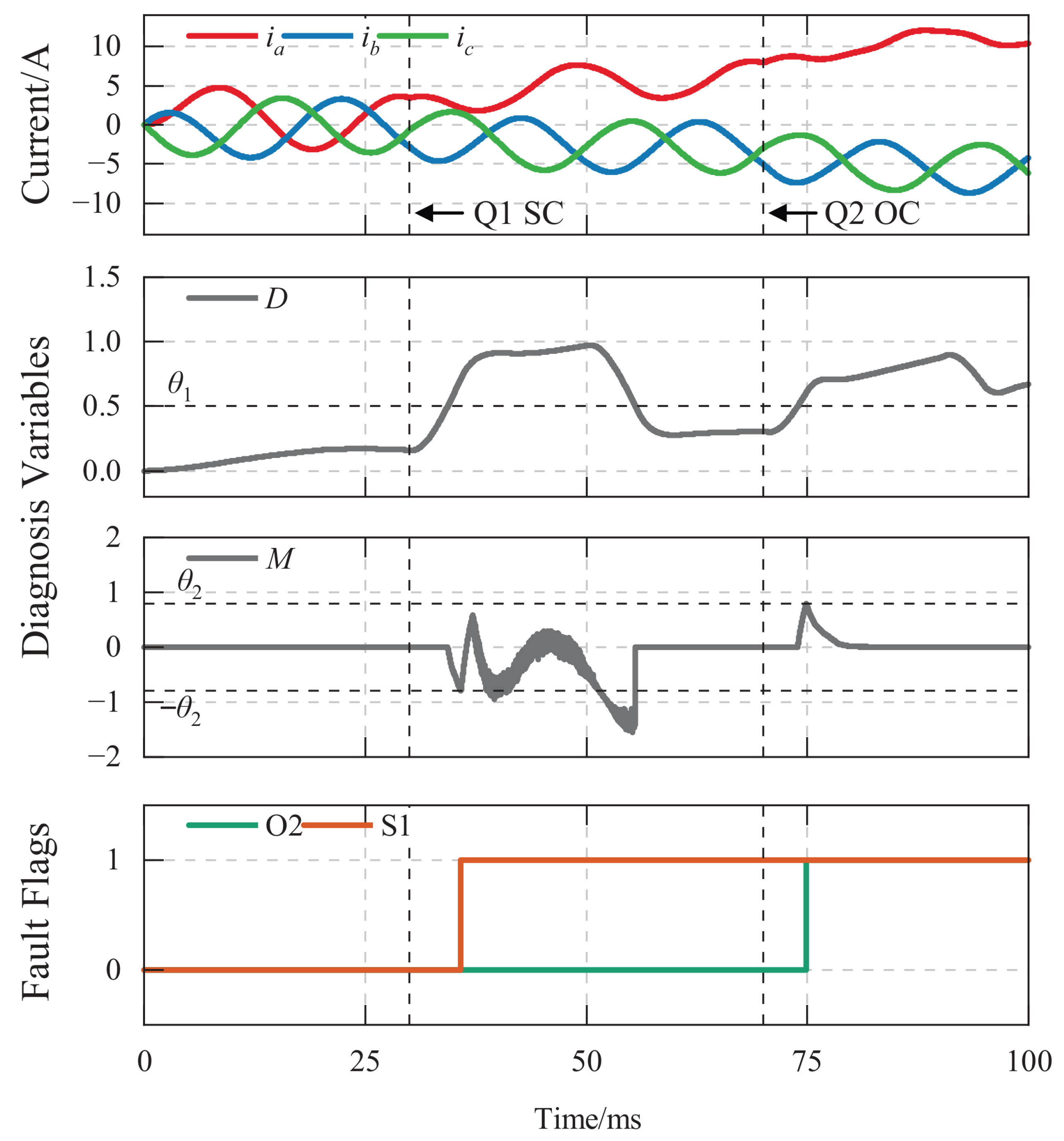

4.1.4. SC–OC Cascaded Fault Simulation

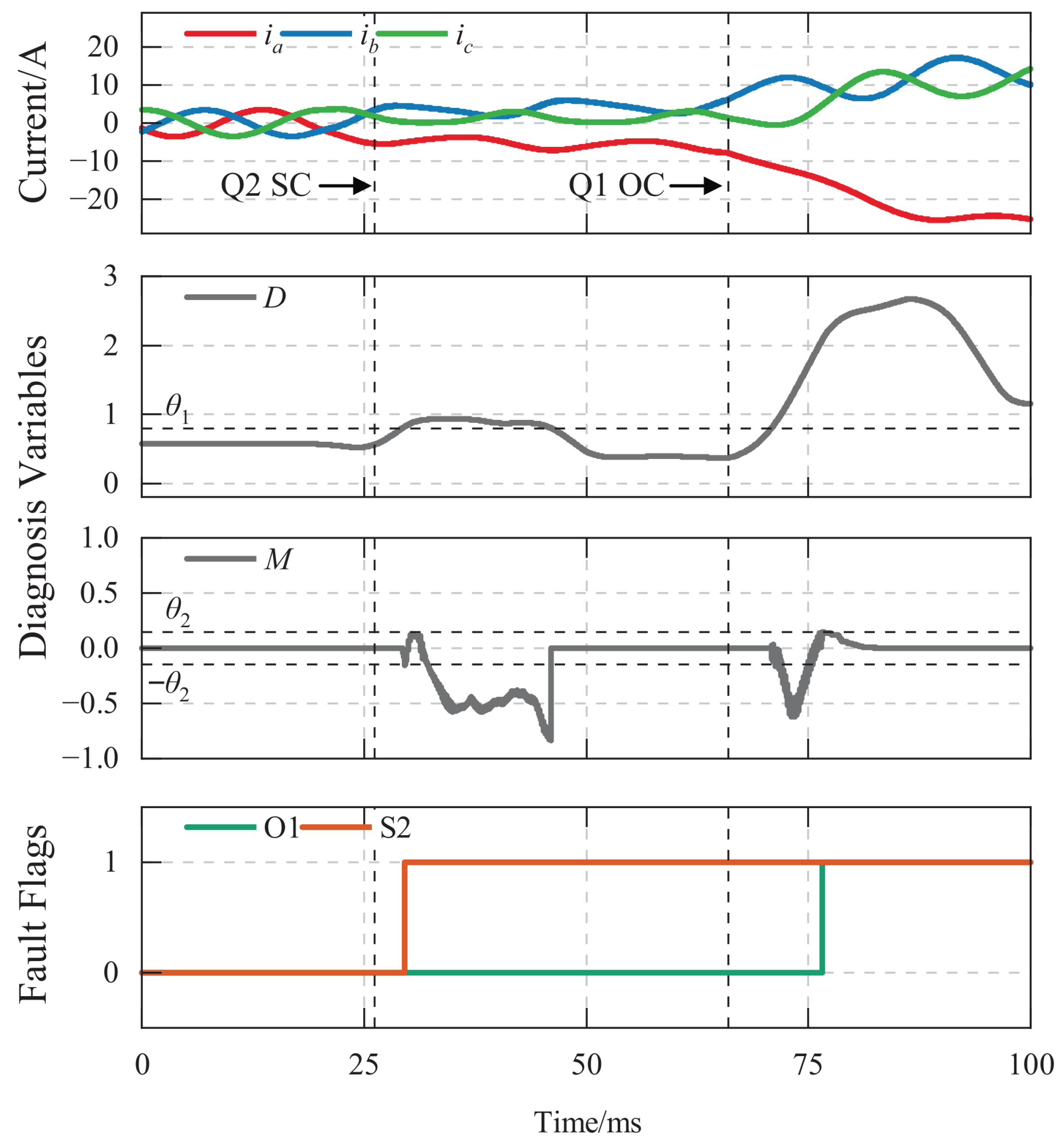

4.2. Experimental Verification

4.2.1. OC–OC Cascaded Fault Experiment

4.2.2. OC–SC Cascaded Fault Experiment

4.2.3. SC–OC Cascaded Fault Experiment

4.3. Accuracy of Proposed Fault Diagnosis Method

4.4. Comparison with Existing Fault Diagnosis Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Jia, H.; Ji, Y.; Dragicevic, T.; Teodorescu, R.; Blaabjerg, F. A Novel Detection and Localization Approach of Open-Circuit Switch Fault for the Grid-Connected Modular Multilevel Converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bryant, A.; Mawby, P.; Xiang, D.; Ran, L.; Tavner, P. An Industry-Based Survey of Reliability in Power Electronic Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Applicat. 2011, 47, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, G.; Lin, J. A Domain Generalization Network Exploiting Causal Representations and Non-Causal Representations for Three-Phase Converter Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 2509713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Cecati, C.; Ding, S.X. A Survey of Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Techniques—Part I: Fault Diagnosis with Model-Based and Signal-Based Approaches. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 3757–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Cecati, C.; Ding, S. A Survey of Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Techniques Part II: Fault Diagnosis with Knowledge-Based and Hybrid/Active Approaches. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 3768–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Wu, X.; Xiang, C.; Li, Z. A Diagnostic Method for Open-Circuit Faults of Loads and Semiconductors in 3L-NPC Inverters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 2577–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, R.; Cherif, B.D.E.; Bendiabdellah, A.; Kaddour, A. An Open-Circuit Faults Diagnosis Approach for Three-Phase Inverters Based on an Improved Variational Mode Decomposition, Correlation Coefficients, and Statistical Indicators. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3510109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Malanche, J.A.; Villalobos-Pina, F.J.; Cabal-Yepez, E.; Alvarez-Salas, R.; Rodriguez-Donate, C. Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis in Power Inverters Through Currents Analysis in Time Domain. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3517512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kang, S.; Wang, P. Current Vector Phase Based Weak Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis of Voltage-Source Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Li, K.; Li, K. Real-Time Diagnosis of Open Circuit Faults in Three-Phase Voltage Source Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 7572–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huangfu, Y.; Gao, F. Sliding Mode Observer-Based Robust Switch Fault Diagnosis of Bidirectional Interleaved Converters for Energy Storage System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 9853–9863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Feng, X.; Wang, R. Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives Based on Voltage Residual Analysis. Energies 2023, 16, 5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Z. A Fast Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis Method of Parallel Wind-Turbine Converters via Zero-Sequence Circulating Current Informed Residual Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Guo, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, P. A Novel Short-Circuit Fault Diagnosis Method for Three-Phase Current Source Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 16792–16802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Qiu, R.; Li, C. Open-Circuit, Current Sensor Fault Diagnosis of Three-Phase Four-Wire Inverters Based on Fourier Fitting. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 3522813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Ma, H. A Model-Data-Hybrid-Driven Diagnosis Method for Open-Switch Faults in Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 4965–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, B.; Xu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Deng, Q.; Ge, X. An Online Data-Driven Method for Simultaneous Diagnosis of IGBT and Current Sensor Fault of Three-Phase PWM Inverter in Induction Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 13281–13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yao, X.; Zhang, H. Multi-Switches Fault Diagnosis Based on Small Low-Frequency Data for Voltage-Source Inverters of PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 6845–6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Luo, H.; Xu, S.; Du, K. Inverter Fault Diagnosis for a Three-Phase Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motor Drive System Based on SDAE-GAN-LSTM. Electronics 2023, 12, 4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaghloul, C.; Tehrani, K.; Vurpillot, F. Open-Circuit Fault Detection in a 5-Level Cascaded H-Bridge Inverter Using 1D CNN and LSTM. Energies 2025, 18, 5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ji, Y.; Meng, G.; Chen, W.; Bai, X. Three-Phase Inverter Fault Diagnosis Based on an Improved Deep Residual Network. Electronics 2023, 12, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, Y. A Transferrable Data-Driven Method for IGBT Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis in Three-Phase Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 13478–13488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Wei, L.; Li, M. Adaptive Sparse Attention Wavelet Network for the Robust Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis in PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 3514611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Li, M.; Ding, S.; Hang, J. Circulating Current-Based Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis for Parallel Inverters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 2902–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Zheng, W.; Wang, J.; Chai, Y.; Ma, M. A Simultaneous Diagnosis Method for Power Switch and Current Sensor Faults in Grid-Connected Three-Level NPC Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, H.; Chai, Y.; Zheng, W.X.; Chen, H. A Novel Adaptive SMO-Based Simultaneous Diagnosis Method for IGBT Open-Circuit Faults and Current Sensor Incipient Faults of Inverters in PMSM Drives for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3526915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Deng, Y.; Hu, X.; Deng, Z.; He, X. A Concurrent Diagnosis Method of IGBT Open-Circuit Faults in Modular Multilevel Converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. A Real-Time Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Hybrid Model Flux Observer for Voltage Source Inverter Fed Sensorless Vector Controlled Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 2539–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sun, J.; Cui, P.; Lu, Y.; Lu, M.; Yu, Y. A Fast and Robust Open-Switch Fault Diagnosis Method for Variable-Speed PMSM System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 2598–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Chai, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Ma, M.; Zheng, W.X. Multiple Open-Switch Fault Diagnosis for Three-Phase Four-Leg Inverter Under Unbalanced Loads via Interval Sliding Mode Observer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 7607–7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Chai, Y.; Ma, M.; Zheng, W.X. Multiple Open-Switch Fault Diagnosis of Grid-Connected Three-Phase Inverters Under Unknown Parameter Conditions Using ICRLS and Disturbance Sliding Mode Observer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 8631–8647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B.; Fu, Y.; Li, J. Inverter Open Circuit Fault Diagnosis Based on Residual Performance Evaluation. IET Power Electron. 2023, 16, 2560–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubabas, H.; Djennoune, S.; Bettayeb, M. Interval Sliding Mode Observer Design for Linear and Nonlinear Systems. J. Process Control 2018, 61, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liao, M.; Song, L.; Guo, X.; Liang, Y. A Fault Diagnosis Method for Open-Circuit Faults Based Voltage Vector Trajectory Distortion Characteristics in Three-Level T-Type Inverters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 5317–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gou, B. A Data-Driven Method for IGBT Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis Based on Hybrid Ensemble Learning and Sliding-Window Classification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2020, 16, 5223–5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fault Phase | K | Possible Fault Type |

|---|---|---|

| A | O1 or S2 | |

| S1 or O2 | ||

| B | O3 or S4 | |

| S3 or O4 | ||

| C | O5 or S6 | |

| S5 or O6 |

| D | Fault Phase | K | M | Diagnostic Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | Health | |||

| A | O1 | |||

| S2 | ||||

| O2 | ||||

| S1 | ||||

| B | O3 | |||

| S4 | ||||

| O4 | ||||

| S3 | ||||

| C | O5 | |||

| S6 | ||||

| O6 | ||||

| S5 | ||||

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Output frequency | 50 Hz |

| DC input voltage | 20 V |

| Switching frequency | 10 kHz |

| Load resistance | 1 |

| Inductance | 5 mH |

| Output current | 3.6 A |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Output frequency | 50 Hz |

| DC input voltage | 20 V |

| Switching frequency | 10 kHz |

| Load resistance | 1 |

| Inductance | 5 mH |

| Output current | 3.6 A |

| Fault Type | T/MA/FA | Fault Type | T/MA/FA |

|---|---|---|---|

| O1O2 | 20/0/0 | O2O1 | 20/0/0 |

| O1S2 | 20/0/0 | S2O1 | 19/1/0 |

| S1O2 | 18/2/0 | O2S1 | 20/0/0 |

| O1O3 | 20/0/0 | O2O4 | 20/0/0 |

| O1O4 | 20/0/0 | O2O3 | 20/0/0 |

| S1O3 | 19/0/1 | S2O4 | 19/1/0 |

| S1O4 | 18/2/0 | S2O3 | 18/1/1 |

| O3S1 | 19/1/0 | O4S2 | 19/0/1 |

| O3S2 | 19/1/0 | O4S1 | 19/0/1 |

| Diagnosis Method | Fault Type | Diagnosis Time | Consider Multi-Switch Faults | Consider Load Change | Microcontroller Realizability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-based [34] | OC | 0.05∼0.55 | Yes | Yes | Easy |

| Signal-based [14] | SC | < | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Data-driven [35] | OC | > | Yes | Yes | Hard |

| Model-based [25] | OC and Sensor fault | < | No | Yes | Yes |

| Model-based [24] | OC | < | No | No | Yes |

| Proposed | OC and SC | ≤ | Yes | Yes | Medium |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.; Du, H.; Ye, X.; Nie, X.; Wang, C.; Zhai, G. Diagnosis of Cascaded Open/Short-Circuit Fault in Three-Phase Inverter Using Two-Stage Interval Sliding Mode Observer. Energies 2025, 18, 6498. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246498

Chen C, Du H, Ye X, Nie X, Wang C, Zhai G. Diagnosis of Cascaded Open/Short-Circuit Fault in Three-Phase Inverter Using Two-Stage Interval Sliding Mode Observer. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6498. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246498

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Cen, He Du, Xuerong Ye, Xiaowen Nie, Chunqing Wang, and Guofu Zhai. 2025. "Diagnosis of Cascaded Open/Short-Circuit Fault in Three-Phase Inverter Using Two-Stage Interval Sliding Mode Observer" Energies 18, no. 24: 6498. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246498

APA StyleChen, C., Du, H., Ye, X., Nie, X., Wang, C., & Zhai, G. (2025). Diagnosis of Cascaded Open/Short-Circuit Fault in Three-Phase Inverter Using Two-Stage Interval Sliding Mode Observer. Energies, 18(24), 6498. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246498