An Assessment of the Vulnerability of Energy Infrastructure to Flood Risks: A Case Study of Odra River Basin in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

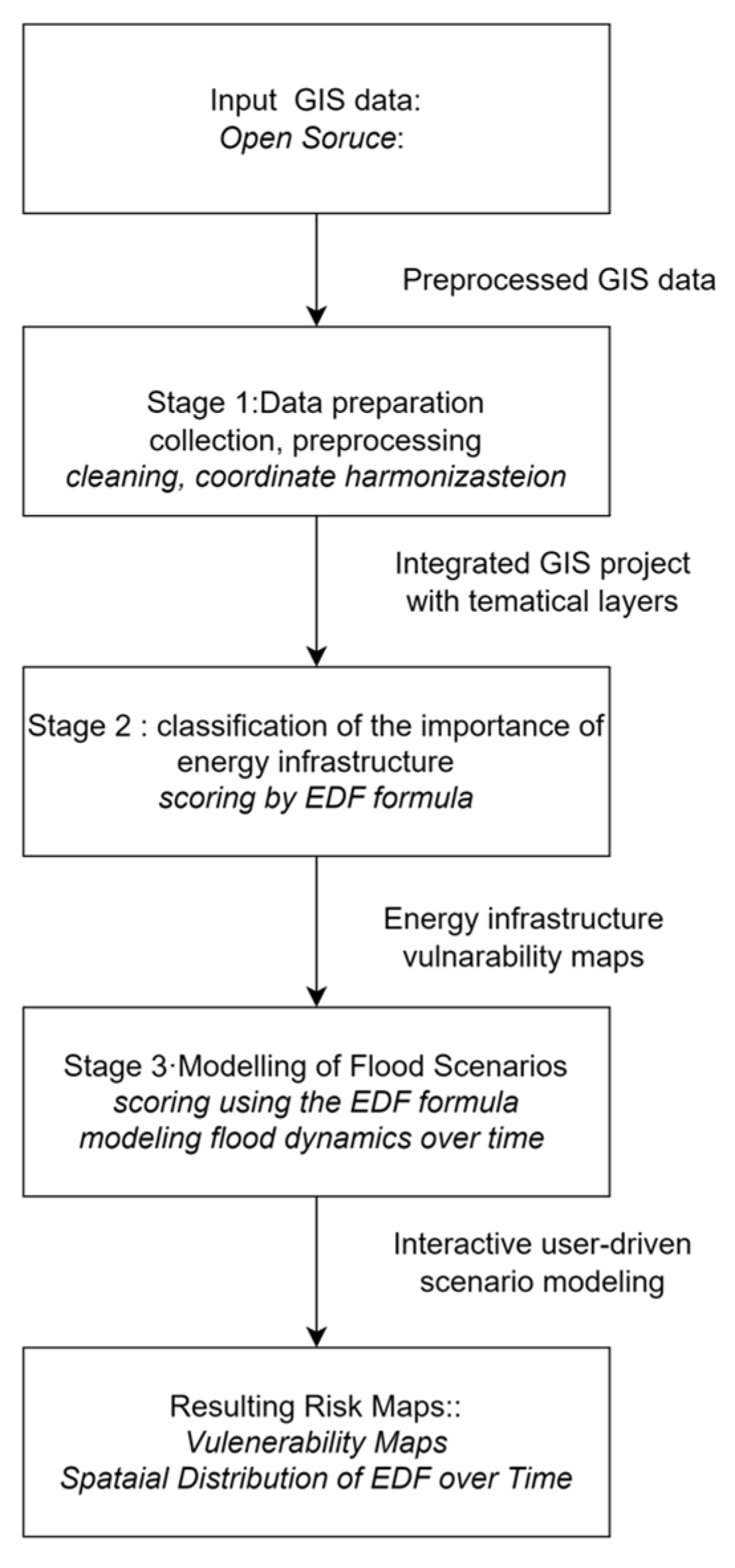

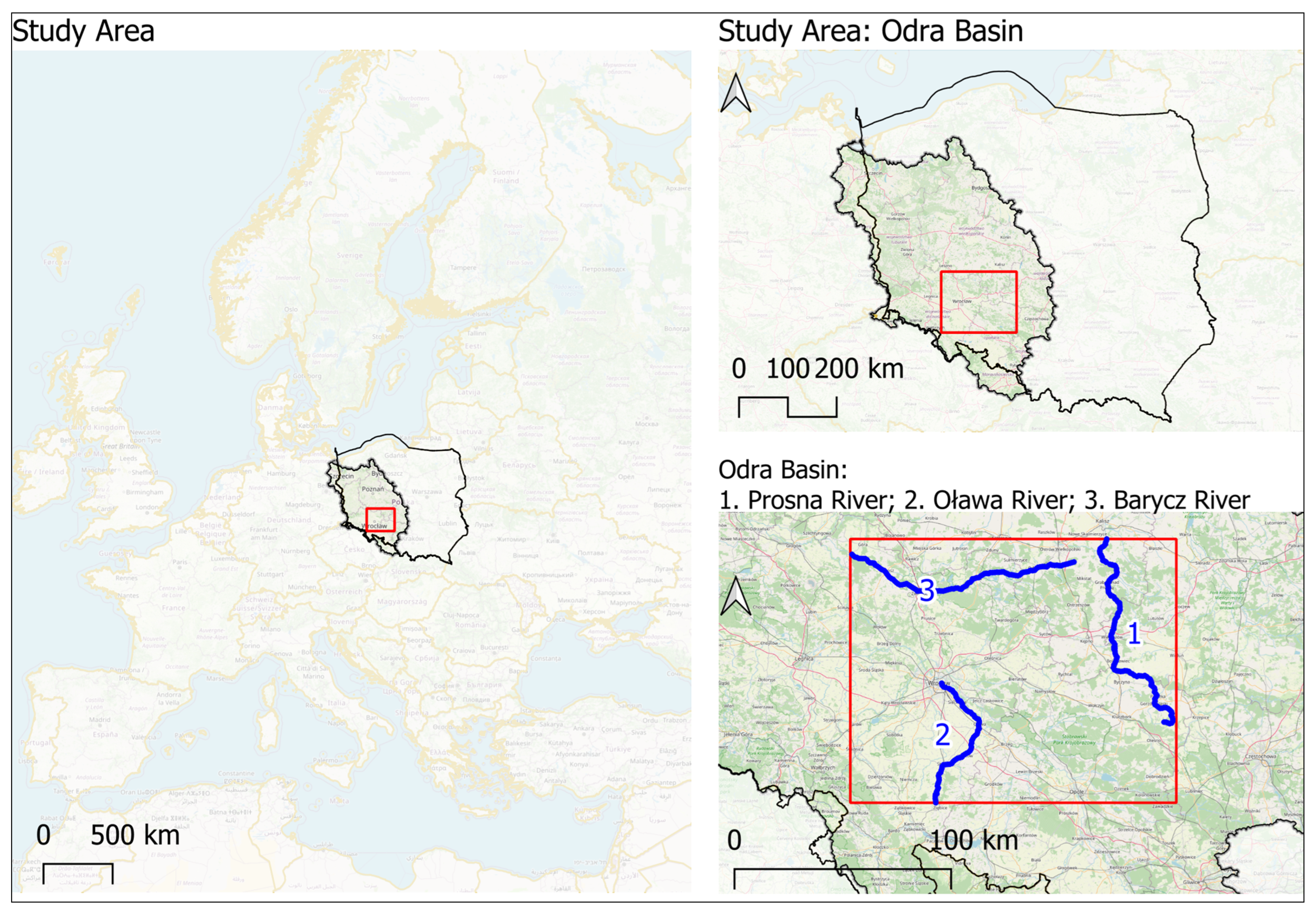

3. Materials and Methods

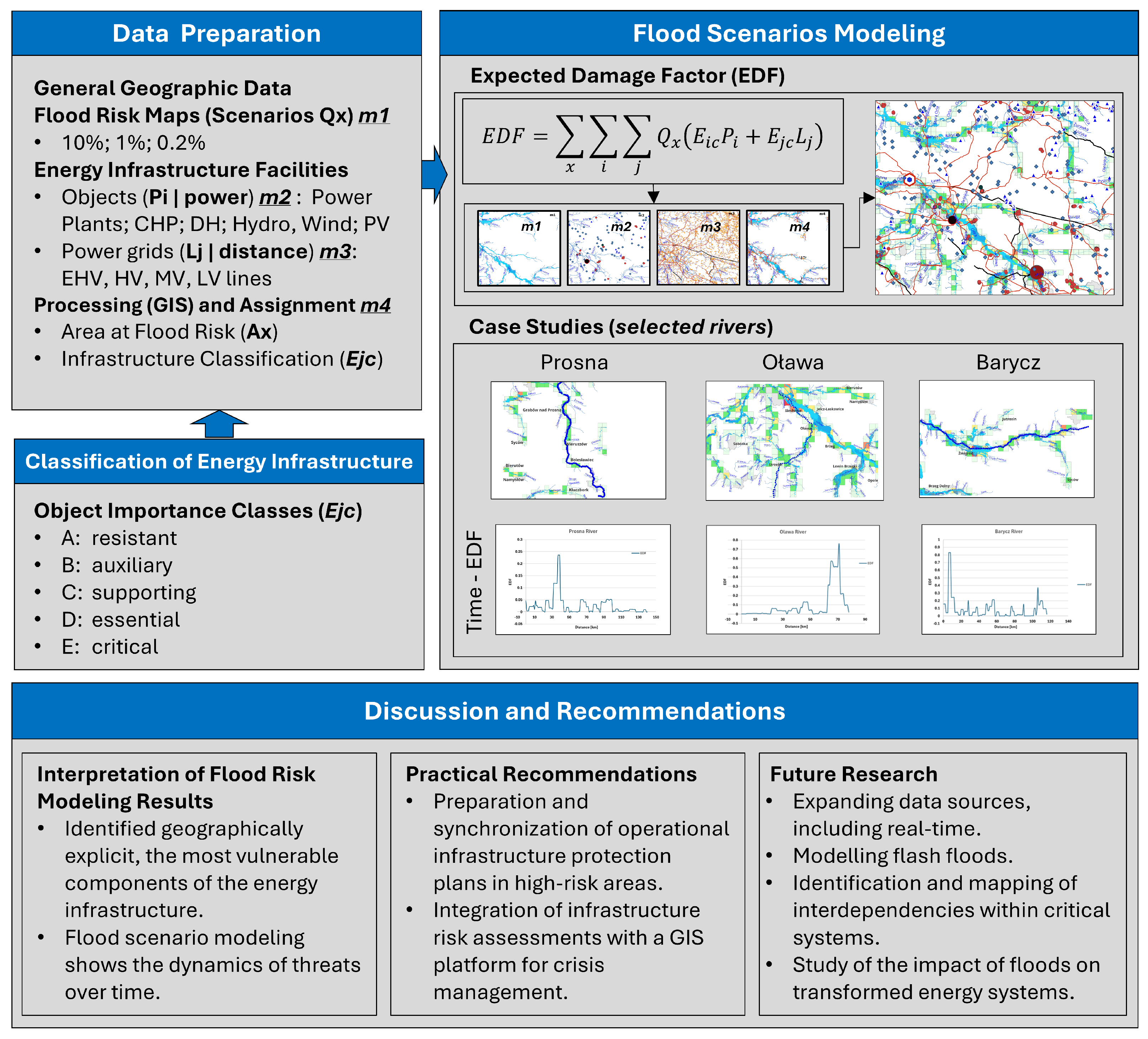

- Data preparation;

- Classification of the importance of energy infrastructure;

- Modelling of flood scenarios.

- Identifying energy infrastructure facilities located in flood risk areas with assigned probabilities of occurrence and then assessing the effects of disruption.

- Mapping energy infrastructure and flood-prone areas on a grid of a specified size (5 × 5 km).

- For each grid element, calculate the dimensionless Expected Damage Factor (EDF), which refers to the EAD (Expected Annual Damage) parameter used in flood damage estimation [65].

- x—flood scenario;

- c—importance class of the energy infrastructure facility;

- i—spot type of energy infrastructure;

- j—linear type of energy infrastructure;

- Q—flood scenario, expressed as the probability of its occurrence;

- P—facility power in MW;

- L—length of the facility in kilometres;

- E—facility significance factor.

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Subjectivity in weight assignment—the classification of the importance of objects is based on expert assumptions, which may vary depending on the local context.

- Dominance of high-power objects—individual power plants can dominate the analysis, which requires the use of normalisation techniques (e.g., logarithmisation).

- Lack of consideration of system redundancy—currently, the method does not analyse the system’s ability to compensate for losses (e.g., through reserve networks).

- Limited time dynamics—flood scenarios are static and do not take into account variability over time (e.g., seasonality, climate change).

- Planning for the protection of critical infrastructure should take into account the location of facilities in flood risk areas and their systemic importance.

- Infrastructure operators should implement technical and organisational measures to increase resilience, e.g., raising the level of installations, creating backup power sources, network segmentation.

- Public authorities can use the results of the analyses to update their crisis management plans, critical infrastructure protection plans and reports required by the CER Directive.

- Cross-sector cooperation (e.g., energy–transport–health) is essential for effective systemic risk management.

- An application of the presented approach to a dynamic decision support environment, in which the model and data architecture enable the user to dynamically model ad hoc scenarios, taking into account real-time changes in the importance parameters.

- Extending the scope of data to include other elements of critical infrastructure of social importance (e.g., water supply and telecommunications networks), which will also allow for comprehensive modelling of cascade effects.

- Modelling flash floods, whose dynamics and local nature pose different challenges.

- Integration with early warning systems–enabling dynamic risk updates.

- Development of methods integrating vulnerability assessment with potential loss costs and adaptation investment planning.

- International comparisons to verify the scalability of the proposed method.

- In the context of energy transition and the growing share of renewable energy sources, it is necessary to take into account new types of risks related to their variability and location. The method can be adapted to assess the vulnerability of wind farms, PV installations and energy storage facilities.

- In the context of the CER Directive, further research on the integration of the method with risk and resilience management systems, including national critical infrastructure protection plans and GISs used by public administration.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDOT | Topographic Objects Database |

| BDOG | General Geographic Objects Database |

| CER | Critical Entities Resilience |

| EAD | Expected Annual Damage |

| EDF | Expected Damage Factor |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

Appendix A. Description of Data Sources and Processing

| Input/Source Data | Description | Key Data Processing Steps | Final Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grid–Study Area | Polygon/5 × 5 km | Grid Generation | Grid 5 × 5 km |

| Flood Hazard Areas In Case of Embankment Destruction | Vector/Polygon Open Data Service (BDOT/BDOG) [69,70] | QGIS, reprojection, layer merging | Flood Risk Map |

| Flood Hazard Areas 10% | as above | as above | as above |

| Flood Hazard Areas 1% | as above | as above | as above |

| Flood Hazard Areas 0.2% | as above | as above | ss above |

| Extra-High-Voltage Lines (EHV) | Vector/Lines Open Data Service [69] | Join attributes by location, Field Calculator | Infrastructure density in km per grid |

| High-Voltage Lines (HV) | as above | as above | as above |

| Medium-Voltage-Lines (MV) | as above | as above | as above |

| Low-Voltage Lines (LV) | as above | as above | as above |

| Power Plants | Vector/Points Own study, based on [74] | Join attributes by location, Field Calculator | Infrastructure density in MW installed capacity per grid |

| Hydro | Points | as above | as above |

| Wind Turbines | as above | as above | Grid with number of installations and total installed capacity (MW) |

| CHP | Vector/Points Own study based Energy Regulatory Office register | as above | as above |

| District Heating | as above | as above | as above |

| Heating-Other 1 | as above | as above | as above |

| PV (50 kW−1 MW) (own elaboration based on statistics | as above | as above | as above |

| EDF | Using Equation (1) in the Area Calculator | Selection, Field calculator | Grid with EDF values |

| EDF–case studies | Cartographic visualization | Combining layers, selecting, reclassifying, exporting result data | Multi-layer visualization |

Appendix B. Flood Risk Characteristics

| Scale | Probability | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very Low | Occurs in exceptional circumstances. |

| 2 | Low, 500-year flood (0.02%) | Not expected to occur and/or not documented at all, does not exist in people’s accounts and/or events have not occurred in similar organisations, devices, communities and/or there is little chance, reason or other circumstances for events to occur. They may occur once every five hundred years. |

| 3 | Moderate, 100-year flood (1%) | May occur within a specified time frame and/or few, rarely documented events, or partially transmitted orally and/or very few events, and/or there is a certain chance, reason or device causing the event to occur. |

| 4 | High, 10-year flood (10%) | It is likely to occur in most circumstances. Floods are systematically documented and communicated in the form of It may occur once every ten years. Due to the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, it has been assumed that the probability is higher than historical data suggest. |

| 5 | Extreme (100%) | Expected to occur in most circumstances and/or these events are very well documented and/or are known among residents and communicated orally. May occur once a year or more often. |

References

- Kanno, T.; Koike, S.; Suzuki, T.; Furuta, K. Human-Centered Modeling Framework of Multiple Interdependency in Urban Systems for Simulation of Post-Disaster Recovery Processes. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2019, 21, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skomra, W.; Wiśniewski, M. Logistics Services as an Element of Critical Infrastructure. Przem. Chem. 2019, 98, 1018–1021. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Baubion, C. OECD Risk Management: Strategic Crisis Management; OECD Working Papers on Public Governance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; No. 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M. Review on Modeling and Simulation of Interdependent Critical Infrastructure Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014, 121, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Ye, Y.; Gao, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, T. Empirical Patterns of Interdependencies among Critical Infrastructures in Cascading Disasters: Evidence from a Comprehensive Multi-Case Analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, M.; Han, C.; Liu, L. Critical Infrastructure Failure Interdependencies in the 2008 Chinese Winter Storms. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Management and Service Science, Wuhan, China, 24–26 August 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, S.M.; Peerenboom, J.P.; Kelly, T.K. Identifying, Understanding, and Analyzing Critical Infrastructure Interdependencies. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2001, 21, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostek, K.; Wiśniewski, M.; Skomra, W. Analysis and Evaluation of Business Continuity Measures Employed in Critical Infrastructure during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoeiro, H.; Davies, G.; Marques, C.; Maidment, G. Heat Recovery Opportunities from Electrical Substation Transformers. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 2931–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhu, B.; Halff, A.; Davis, S.J.; Liu, Z.; Bowring, S.; Arous, S.B.; Ciais, P. Europe’s Adaptation to the Energy Crisis: Reshaped Gas Supply–Transmission–Consumption Structures and Driving Factors from 2022 to 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 3431–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, L.; Carvajal, A.B.F.; De Tejada, V.F. Improving the Concept of Energy Security in an Energy Transition Environment: Application to the Gas Sector in the European Union. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2022, 9, 101045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, B.-J.; Heinrichs, H.U.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Adapting the Theory of Resilience to Energy Systems: A Review and Outlook. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2019, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCB. National Crisis Management Plan—Part B; Government Center for Security (RCB): Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- Ligenza, P.; Tokarczyk, T.; Adynkiewicz-Piragas, M. (Eds.) Course and Effects of Selected Floods in the Odra River Basin from the 19th Century to the Present; Seria publikacji naukowo-badawczych IMGW–PIB; Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—National Research Institute (IMGW–PIB): Warsaw, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-64979-45-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Infrastructure. Journal of Law 2022, Item 2714. Regulation of 26 October 2022 on the Adoption of the Flood Risk Management Plan for the Odra River Basin District 2022. Available online: https://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/DU/2022/2714 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Journal of Laws 2017, Item 1566, as Amended the Act of 20 July 2017, Water Law. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20170001566 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- RCB. National Crisis Management Plan—Part A; Government Center for Security (RCB): Warsaw, Poland, 2022. (In Polish)

- Ashley, S.T.; Ashley, W.S. Flood Fatalities in the United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2008, 47, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paprotny, D.; Sebastian, A.; Morales-Nápoles, O.; Jonkman, S.N. Trends in Flood Losses in Europe over the Past 150 Years. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawiła-Niedźwiecki, J. Operational Risk as a Problematic Triad: Risk, Resource Security, Business Continuity; Edu-Libri: Kraków, Poland, 2014; ISBN 978-83-63804-42-8. [Google Scholar]

- Skomra, W.; Abramowicz, A.; Wróblewski, D.; Duda, D.; Szufnara, P.; Mizera, M.; Pukacka, M.; Pudzianowski, J.; Marczyński, D. (Eds.) Standards and Good Practices to Ensure Efficient Functioning and Continuity of Critical Infrastructure; War Studies University: Warsaw, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-8263-366-5. [Google Scholar]

- RCB. Procedure for the Preparation of a Partial Report. An Integral Part with a Spreadsheet for the Report on National Security Threats; Government Centre for Security (RCB): Warsaw, Poland, 2010.

- Skomra, W. (Ed.) Risk Assessment Methodology for the Needs of the Crisis Management System of the Republic of Poland; Fire University; BEL Studio: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-83-7798-165-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zawiła-Niedźwiecki, J.; Kisilowski, M.; Kunikowski, G.; Skomra, W.; Wiśniewski, M. Introduction to Public Crisis Management: Collective Work; Warsaw University Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; ISBN 978-83-8156-105-1. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the Assessment and Management of Flood Risks; Official Journal of the European Union L288 on 6.11.2007; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; pp. 27–34.

- Nik, V.M.; Perera, A.T.D.; Chen, D. Towards Climate Resilient Urban Energy Systems: A Review. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Effective Crisis Management; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-83-7930-616-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, A.C.R.; Costoya, X.; Nieto, R.; Liberato, M.L.R. Extreme Weather Events on Energy Systems: A Comprehensive Review on Impacts, Mitigation, and Adaptation Measures. Sustain. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritzalis, D.; Stergiopoulos, G.; Theocharidou, M. (Eds.) Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience: Theories, Methods, Tools and Technologies. In Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing Imprint: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-00024-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, S.M.; Peerenboom, J.P.; Kelly, T.K. Identifying Critical Infrastructure Sectors and Their Dependencies: An Indian Scenario. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2014, 7, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC Directive (EU) 2022/2557 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on the Resilience of Critical Entities and Repealing Council Directive 2008/114/EC 2022; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- Wiśniewski, M. Method of Eliminating Interdependencies of Essential Services Raising the Risk of Loss of Business Continuity. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 159380–159399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunikowski, G. The Resilience of the Energy Supply System in the Example of the Heating System. NSZ 2024, 19, 55–74. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyub, B.M. Systems Resilience for Multihazard Environments: Definition, Metrics, and Valuation for Decision Making. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierney, K.; Bruneau, M. Conceptualizing and Measuring Resilience: A Key to Disaster Loss Reduction; TR News; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, F. Resilience Thinking as an Interdisciplinary Guiding Principle for Energy System Transitions. Resources 2016, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, S.H.; Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, M.; Bohensky, E.; Cundill, G.; Dakos, V.; Daw, T.; Kotschy, K.; Leitch, A.; et al. Applying Resilience Thinking: Seven Principles for Building Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems; Stockholm Resilience Centre: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, M.L. Principles for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-107-08265-6. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, T.B.; Nakicenovic, N.; Patwardhan, A.; Gomez-Echeverri, L. (Eds.) Global Energy Assessment (GEA): Toward a Sustainable Future; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-511-79367-7. [Google Scholar]

- WEC. Energy Transition Toolkit User Guide; World Energy Council: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MkiŚ. Poland’s Energy Policy Until 2040. Annex to Resolution No. 22/2021 of the Council of Ministers of 2 February 2021; Ministry of Climate and Environment (MKiŚ): Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- Dołęga, W. National Grid Electrical Infrastructure—Threats and Challenges 2023. Polityka Energetyczna–Energy Policy J. 2018, 21, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MkiŚ. Assumptions for the Update of Poland’s Energy Policy Until 2040; Ministry of Climate and Environment (MKiŚ): Warsaw, Poland, 2023.

- Kunikowski, G. Energy Security—Assessment, Trends and the Need to Raise Awareness of the Social Dimension. In Contemporary Needs and Requirements for Education in Security; Kunikowski, J., Araucz-Boruc, A., Wierzbicki, G., Eds.; Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities Publishing House: Siedlce, Poland, 2018; pp. 427–442. ISBN 978-83-946062-0-6. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kunikowski, G.; Zawiła-Niedźwiecki, J. Current Trends in the Development of Energy Technologies in the Context of the National Critical Infrastructure Security—Identification and Evaluation of the Relationship between Energy Technologies and the Level of Security of Critical Infrastructure Subsystem (Energy). In Current Trends in Management: Business and Public Administration; Świrska, A., Ed.; Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities Publishing House: Siedlce, Poland, 2015; pp. 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- PSE. Integrated Impact Report 2023; Polskie Sieci Elektroenergetyczne: Konstancin-Jeziorna, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Janowicz, L.; Kunikowski, G. Assessment of Renewable Resources Based on Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Inżynieria Rol. 2008, 4, 329–335. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; M’Ikiugu, M.; Kinoshita, I. A GIS-Based Approach in Support of Spatial Planning for Renewable Energy: A Case Study of Fukushima, Japan. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2087–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omitaomu, O.A.; Blevins, B.R.; Jochem, W.C.; Mays, G.T.; Belles, R.; Hadley, S.W.; Harrison, T.J.; Bhaduri, B.L.; Neish, B.S.; Rose, A.N. Adapting a GIS-Based Multicriteria Decision Analysis Approach for Evaluating New Power Generating Sites. Appl. Energy 2012, 96, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baky, M.A.A.; Islam, M.; Paul, S. Flood Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment for Different Land Use Classes Using a Flow Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 4, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Huo, A.; Ullah, W.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, A.; Zhong, F. Flood Vulnerability Assessment in the Flood Prone Area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1303976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, I.; Kuleshov, Y. Flood Vulnerability Assessment and Mapping: A Case Study for Australia’s Hawkesbury-Nepean Catchment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, Q.; Sun, H. Risk and Vulnerability Assessment of Energy-Transportation Infrastructure Systems to Extreme Weather. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, R.J.; Apan, A.; McDougall, K. Vulnerability Assessment and Interdependency Analysis of Critical Infrastructures for Climate Adaptation and Flood Mitigation. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2015, 6, 313–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweco. Expect the Unexpected: Floods and Critical Infrastructure; Sweco: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fekete, A. Critical Infrastructure and Flood Resilience: Cascading Effects beyond Water. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L.F.; Battemarco, B.P.; Oliveira, A.K.B.; Miguez, M.G. A New Approach to Assess Cascading Effects of Urban Floods. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 8357–8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, B.; Guldåker, N.; Johansson, J. A Methodological Approach for Mapping and Analysing Cascading Effects of Flooding Events. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2023, 21, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Priesmeier, P.; Fekete, A.; Lichte, D.; Fiedrich, F. Cascading Effects of Critical Infrastructures in a Flood Scenario: A Case Study in the City of Cologne. In Proceedings of the 21st International ISCRAM Conference (ISCRAM 2024), Münster, Germany, 25–29 May 2024; Volume 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, F.; Geng, L. A Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework of Urban Infrastructure Cascading Disasters Using Scientometric Methods. Buildings 2025, 15, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Fan, C.; Farahmand, H.; Coleman, N.; Esmalian, A.; Lee, C.-C.; Patrascu, F.I.; Zhang, C.; Dong, S.; Mostafavi, A. Smart Flood Resilience: Harnessing Community-Scale Big Data for Predictive Flood Risk Monitoring, Rapid Impact Assessment, and Situational Awareness. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2022, 2, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, R.; Thacker, S.; Hall, J.W.; Alderson, D.; Barr, S. Critical Infrastructure Impact Assessment Due to Flood Exposure. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.; Flachsbarth, F.; Plaga, L.S.; Braun, M.; Härtel, P. Energy Security and Resilience: Reviewing Concepts and Advancing Planning Perspectives for Transforming Integrated Energy Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.18396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiak, R. Large-Scale Two-Dimensional Cascade Modeling of the Odra River for Flood Hazard Management. Water 2023, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.; Zhou, Q.; Linde, J.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K. Comparing Methods of Calculating Expected Annual Damage in Urban Pluvial Flood Risk Assessments. Water 2015, 7, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ładysz, J. GIS Technology in Security Engineering; General Tadeusz Kościuszko Military University of Land Forces: Wrocław, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-83-63900-23-6. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. CORINE Land Cover 2018 (Vector), Europe, 6-Yearly—Version 2020_20u1, May 2020; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020.

- European Environment Agency (EEA). European Catchments and Rivers Network System (ECRINS), Natural Sub-Basins of EUROPE–Version 0. Dec. 2011. EEA Geospatial Data Catalogue. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/a9844d0c-6dfb-4c0c-a693-7d991cc82e6e?activeAccordion=814%2C1273 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- KPRM Central Public Data Portal. 2025. Available online: https://dane.gov.pl/pl (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Journal of Laws 2021, Item 1412 Regulation of the Minister of Development, Labour and Technology of 27 July 2021, on the Database of Topographic Objects and the Database of General Geographic Objects, as Well as Standard Cartographic Studies. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20210001412 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Wielkopolska Chamber of Agriculture the Barycz River Keeps Flooding. Available online: https://wir.org.pl/asp/barycz-ciagle-wylewa,1,artykul,1,1006 (accessed on 10 September 2025). (In Polish).

- Viavattene, C.; Fadipe, D.; Old, J.; Thompson, V.; Thorburn, K. Estimation of Scottish Pluvial Flooding Expected Annual Damages Using Interpolation Techniques. Water 2022, 14, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, R.; Bachmann, D. Integrating Critical Infrastructure Networks into Flood Risk Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przedlacki, W.; Charkowska, Z.; Kubiczek, P.; Swoczyna, B.; Żelisko, W.; Borowczyk, Z.; Siwiński, P. Database of Thermal Power Plants and Combined Heat and Power Plants in Poland; Fundacja Instrat: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Scale | Effects | Value | Description | Related Facilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Resistant (replaceable, insignificant) | 0.2 | They serve a supplementary function and do not affect everyday functioning. | Spots 1: Resources such as power generators, Fuel reserves. Lines 2: none |

| B | Auxiliary (relevant to a limited extent) | 0.4 | Only local impact, to a limited extent | Spots: Local heating plants with a capacity of up to 0.5 MW; Auxiliary equipment Linear: none |

| C | Supporting (important on a local scale) | 0.6 | Auxiliary facilities that affect quality of life but do not directly threaten life or cause major damage. Continuity of operation can be restored within 12 h (facilities have reserve capacity/redundancy). | Spots: Local CHP up to 5 MW capacity; Local heating plants. Linear: Distribution lines |

| D | Significant (important on a local and system scale) | 0.8 | They do not affect the continuity of supply at the national level. | Spots: Medium CHP (5–20 MWel), heating plants; Wind farms Linear: Low and medium voltage lines. |

| E | Critical (important for system stability) | 1.0 | They cause local disruptions to energy supply, affect quality, and cause temporary interruptions in supply. | Spots: System power plants and combined heat and power plants Linear: Extra-high voltage transmission lines; High-voltage transmission lines. |

| No | Name | Symbol | Unit | Class | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Power Plants < 5 MW | PowerPlant1 | MW | D | 0.8 |

| 2 | Power Plants > 5 MW | PowerPlant2 | MW | E | 1 |

| 3 | CHP < 5 MW | CHP1 | MW | D | 0.8 |

| 4 | CHP > 5 MW | CHP2 | MW | E | 1 |

| 5 | Hydroelectric power plants < 5 MW | Hydro1 | MW | B | 0.4 |

| 6 | Hydroelectric power plants > 5 MW | Hydro2 | MW | E | 1.0 |

| 7 | PV | PV | MW | B | 0.4 |

| 8 | Wind | WND | MW | C | 0.6 |

| 9 | District Heating | DH | MW | C | 0.6 |

| 10 | Heat Other | H | MW | B | 0.4 |

| 11 | Extra High Voltage Lines | EHV | km | E | 1.0 |

| 12 | High voltage lines | HV | km | D | 0.8 |

| 13 | Medium Voltage Lines | MV | km | C | 0.6 |

| 14 | Low Voltage Lines (distribution) | LV | km | B | 0.4 |

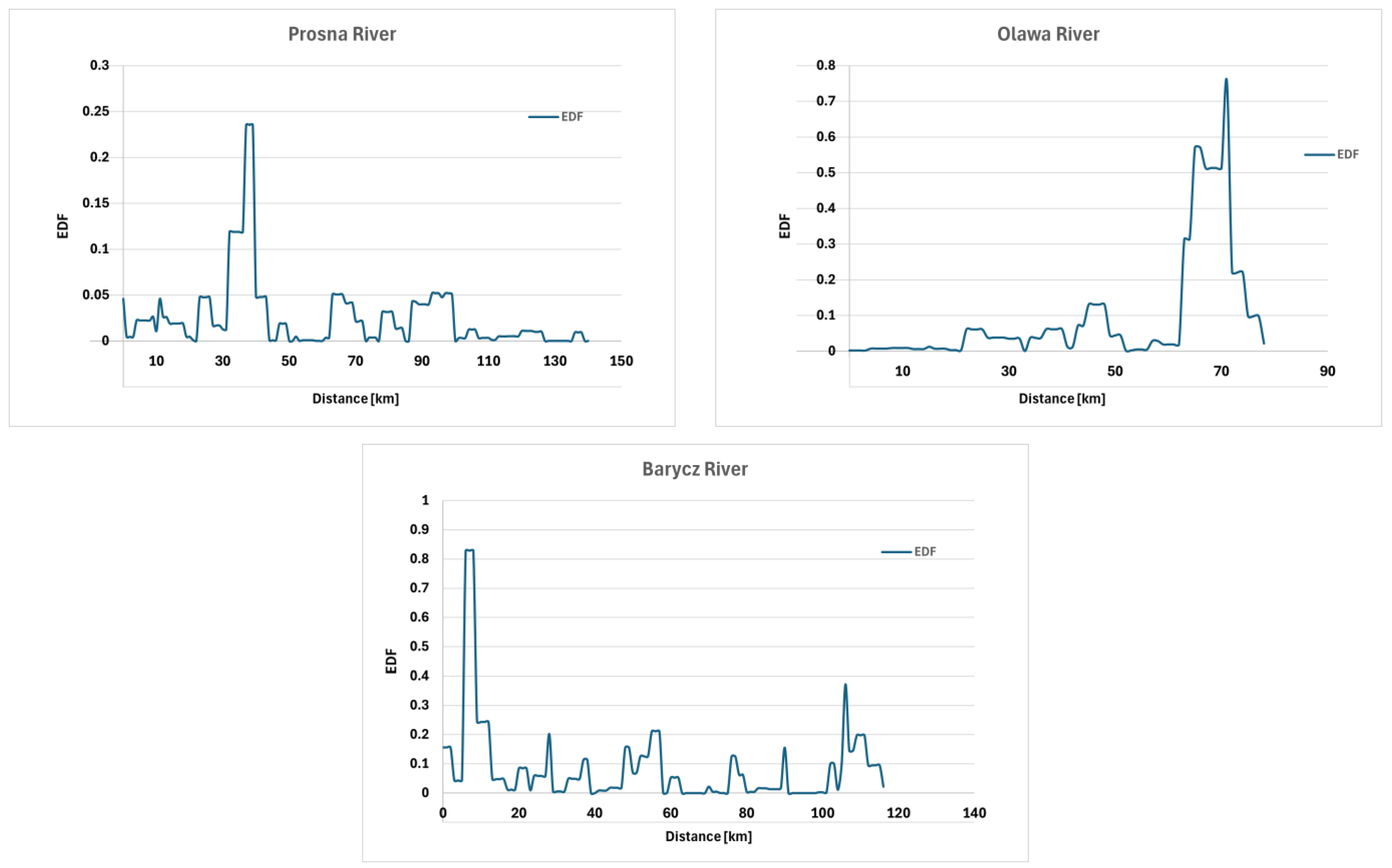

| River | Threats | Infrastructure | EDF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prosna | diffuse threat; river runs through low-population areas | a large share of HV and EHV transmission lines, fewer point facilities | max 0.24 37–39 km |

| Oława | river flowing into Wrocław, where threats accumulate, lines, and urbanised areas | share of HV and EHV transmission lines, short distances between the river and highly urbanised areas | max 0.77 71 km |

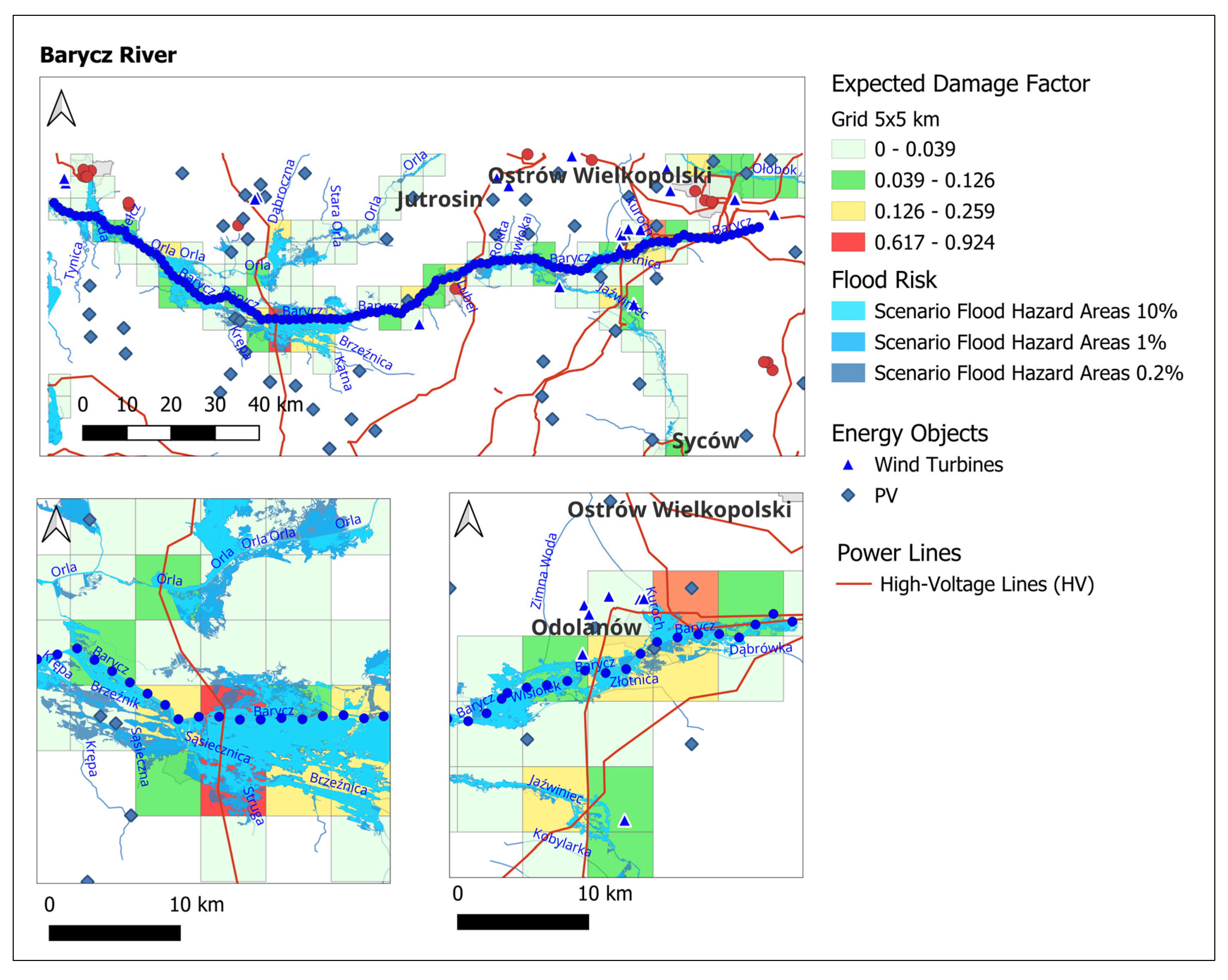

| Barycz | river floods in a wide valley, lower infrastructure intensity | Long section of HV line in floodplain for flood risk scenarios 10% 1%, 0.02% | max 0.82 6–8 km |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duda, D.; Kunikowski, G.; Skomra, W.; Zawiła-Niedźwiecki, J. An Assessment of the Vulnerability of Energy Infrastructure to Flood Risks: A Case Study of Odra River Basin in Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 6453. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246453

Duda D, Kunikowski G, Skomra W, Zawiła-Niedźwiecki J. An Assessment of the Vulnerability of Energy Infrastructure to Flood Risks: A Case Study of Odra River Basin in Poland. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6453. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246453

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuda, Dorota, Grzegorz Kunikowski, Witold Skomra, and Janusz Zawiła-Niedźwiecki. 2025. "An Assessment of the Vulnerability of Energy Infrastructure to Flood Risks: A Case Study of Odra River Basin in Poland" Energies 18, no. 24: 6453. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246453

APA StyleDuda, D., Kunikowski, G., Skomra, W., & Zawiła-Niedźwiecki, J. (2025). An Assessment of the Vulnerability of Energy Infrastructure to Flood Risks: A Case Study of Odra River Basin in Poland. Energies, 18(24), 6453. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246453