The Research on V2G Grid Optimization and Incentive Pricing Considering Battery Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Travel chain-based V2G flexibility modeling. Instead of assuming exogenous plug-in profiles, the available charging/discharging capacity of the EV fleet is derived from the statistical distributions of the departure times, return times, and trip distances. This links the time-varying and location-dependent V2G potential more explicitly to the user travel behavior.

- (2)

- SOH- and cycle-aware incentive pricing. A degradation-aware incentive tariff was designed, in which both the battery state of health (SOH) and accumulated equivalent cycle count are incorporated through an explicit compensation term. In this way, grid-side peak-shaving requirements are considered together with user-side degradation costs and participation thresholds within the same pricing mechanism.

- (3)

- Two-stage coordination of grid and user objectives. A two-stage optimization framework was adopted, where a meta-heuristic method in the upper stage determines the charging/discharging time slots and a quadratic programming model in the lower stage optimizes power allocation. This structure seeks a practical trade-off between load smoothing and user economic benefits, and its performance is illustrated through numerical case studies and SOC/SOH sensitivity analysis.

2. Modeling V2G Mobility Behavior

2.1. Travel Chain Model

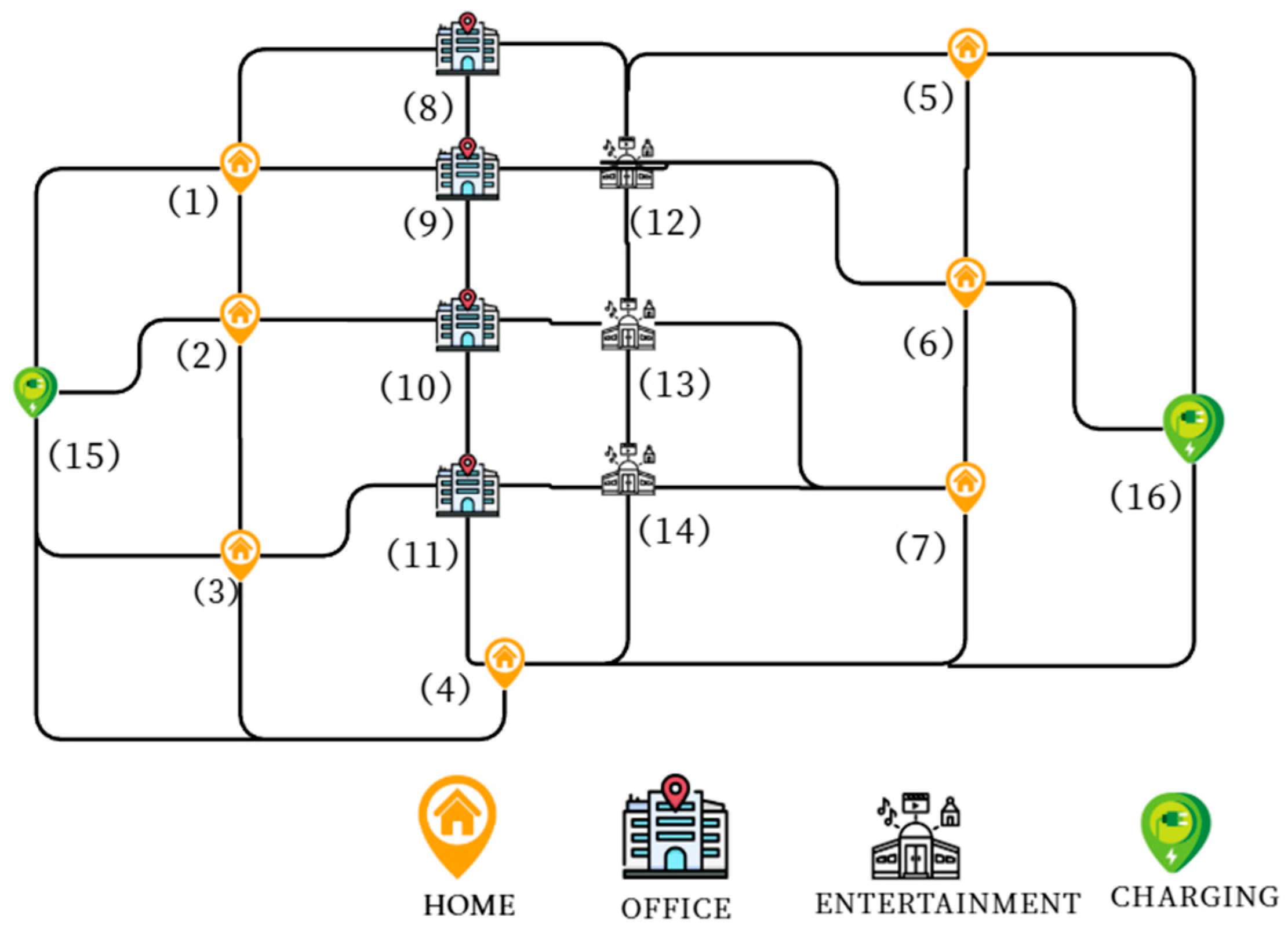

2.2. Modeling Spatiotemporal Parameters of Journeys

2.2.1. Departure Return Time Coupling Model

2.2.2. Path Selection and Distance Configuration

3. Modeling Electric Vehicle Battery Degradation and V2G Electricity Consumption

3.1. Battery Degradation Model

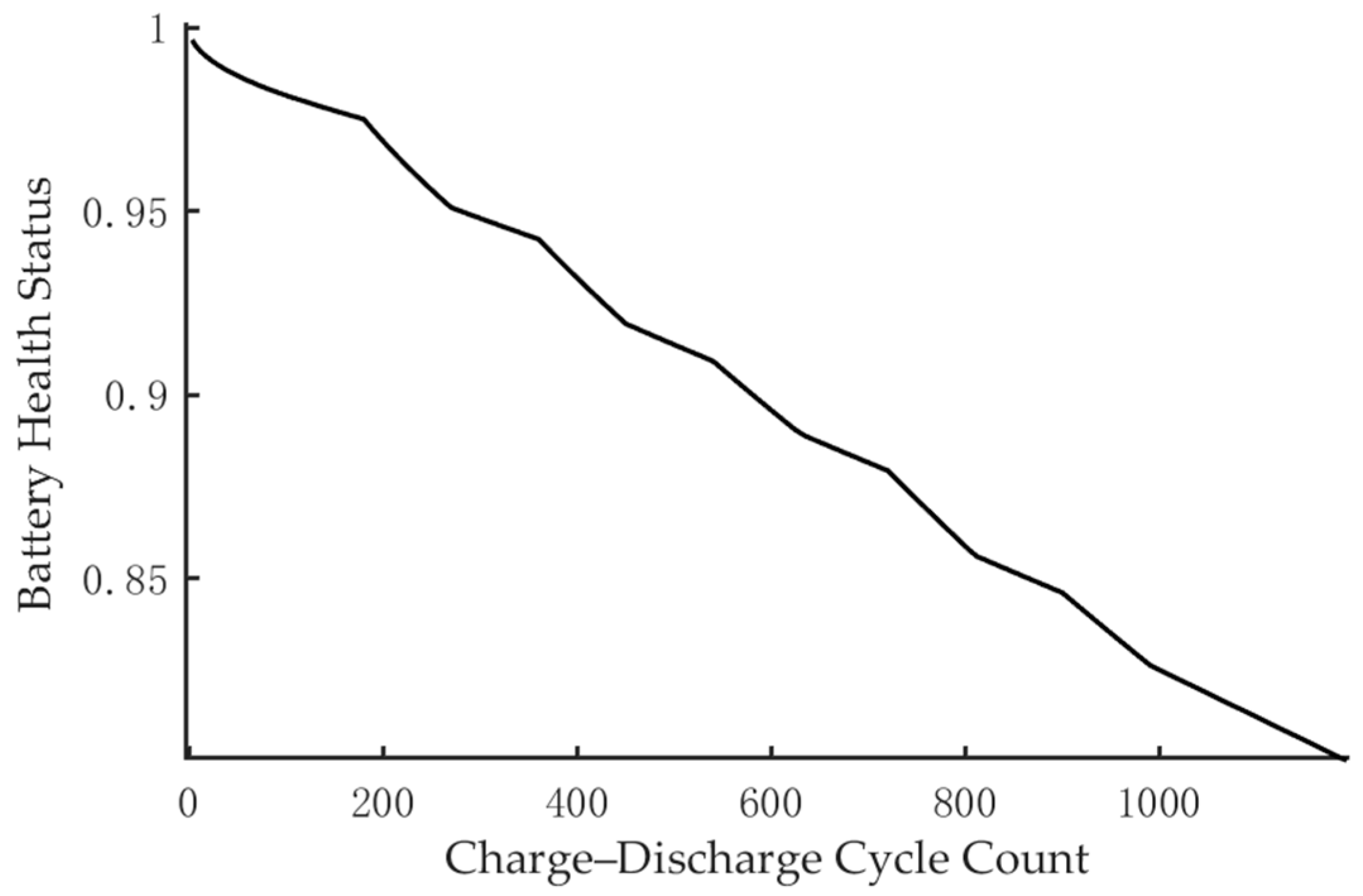

3.2. Cycle Count-Driven Dynamic Capacity Degradation

3.3. Electric Vehicle Power Consumption Model

3.4. Battery Health-Coupled Dynamic Pricing Model

4. Two-Stage Optimization Model for Electric Vehicles Based on Supply and Demand Requirements

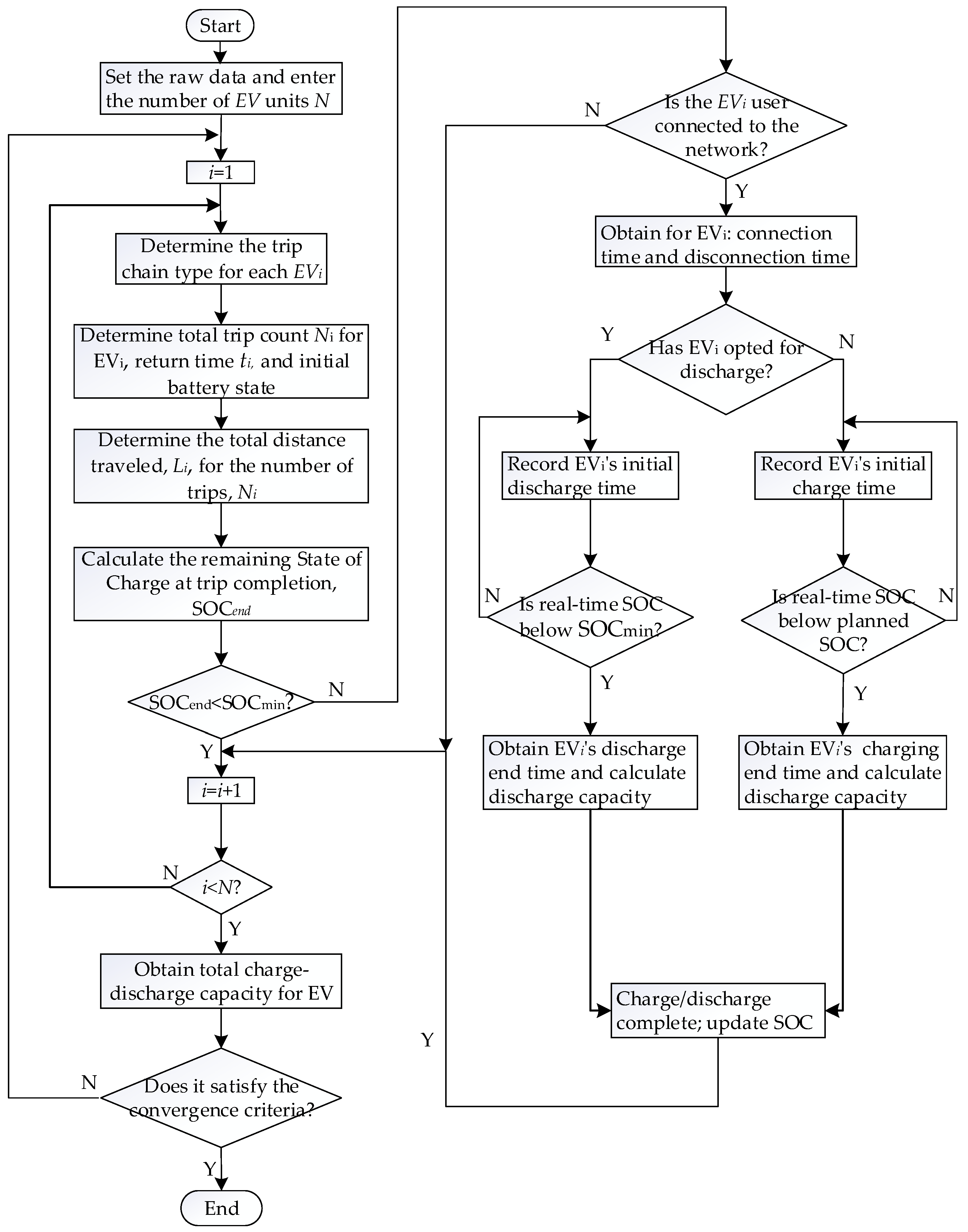

4.1. Framework for Electric Vehicle Charging and Discharging Scenarios

4.2. Multi-Objective Function Formulation

4.2.1. Grid Side: Minimization of Daily Load Variance

4.2.2. User Side: Minimizing User-Side Costs

4.2.3. Constraints

4.3. Solution Algorithm for Multi-Objective Coordinated Scheduling Models

5. Case Study Analysis

5.1. Parameter Settings

- (1)

- Vehicle parameters: Fifty BYD e6 models were selected, with lithium iron phosphate batteries specified and a battery capacity of 60 kWh.

- (2)

- Battery cost parameters: The cost of automotive lithium ion batteries ranges from 0.5–0.8 CNY/Wh [27].

- (3)

- SOH degradation stratification: Classified into four tiers based on the battery state of health (SOH ≥ 0.95, 0.90 ≤ SOH < 0.95, 0.85 ≤ SOH < 0.90, and 0.80 ≤ SOH < 0.85), with stratification proportions of 30%, 30%, 20%, and 20%, respectively.

- (4)

- Initial SOC distribution: Assume that, at the initial time point each day, follows a uniform distribution over [0.6, 1]. Similarly, the initial time point for the EV battery the following day follows a uniform distribution over [0.6, 1].

- (5)

- Travel chain proportion: Four travel chain patterns are defined (H-W-H, H-O-H, H-W-O-H, and H-O-W-H), with respective proportions of 30%, 10%, 30%, and 30%.

- (6)

- Only scenarios where EV users charge at home are considered. EV users whose battery charge during travel falls short of meeting daily travel requirements will be excluded.

- (7)

- Multi-objective weighting: Set parameters to balance grid peak-shaving and user economic objectives, preventing dominance by any single objective.

- (8)

- Time-of-use electricity pricing: Referencing industrial electricity tariffs in a Chinese city. Specific values are shown in Table 4.

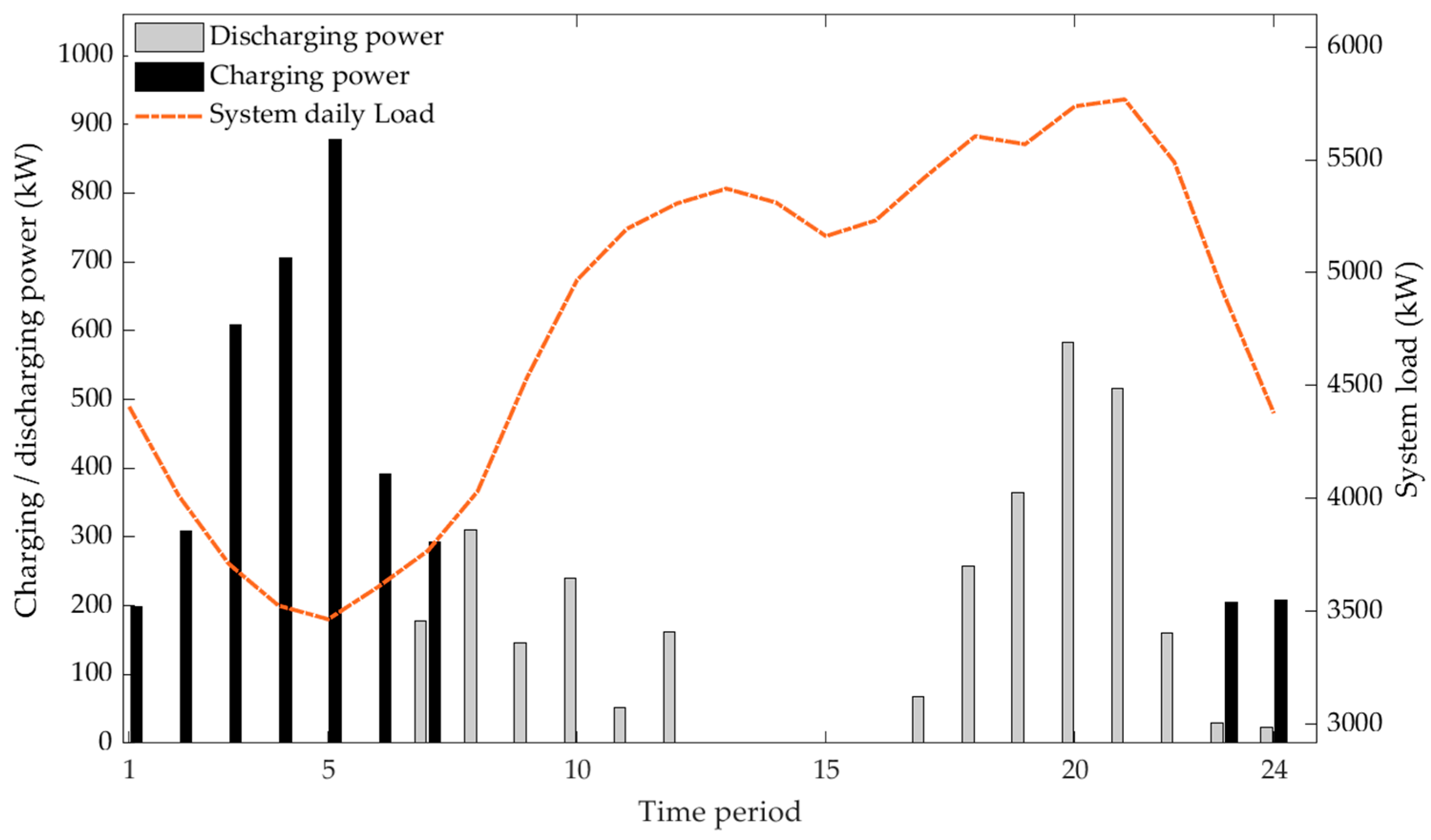

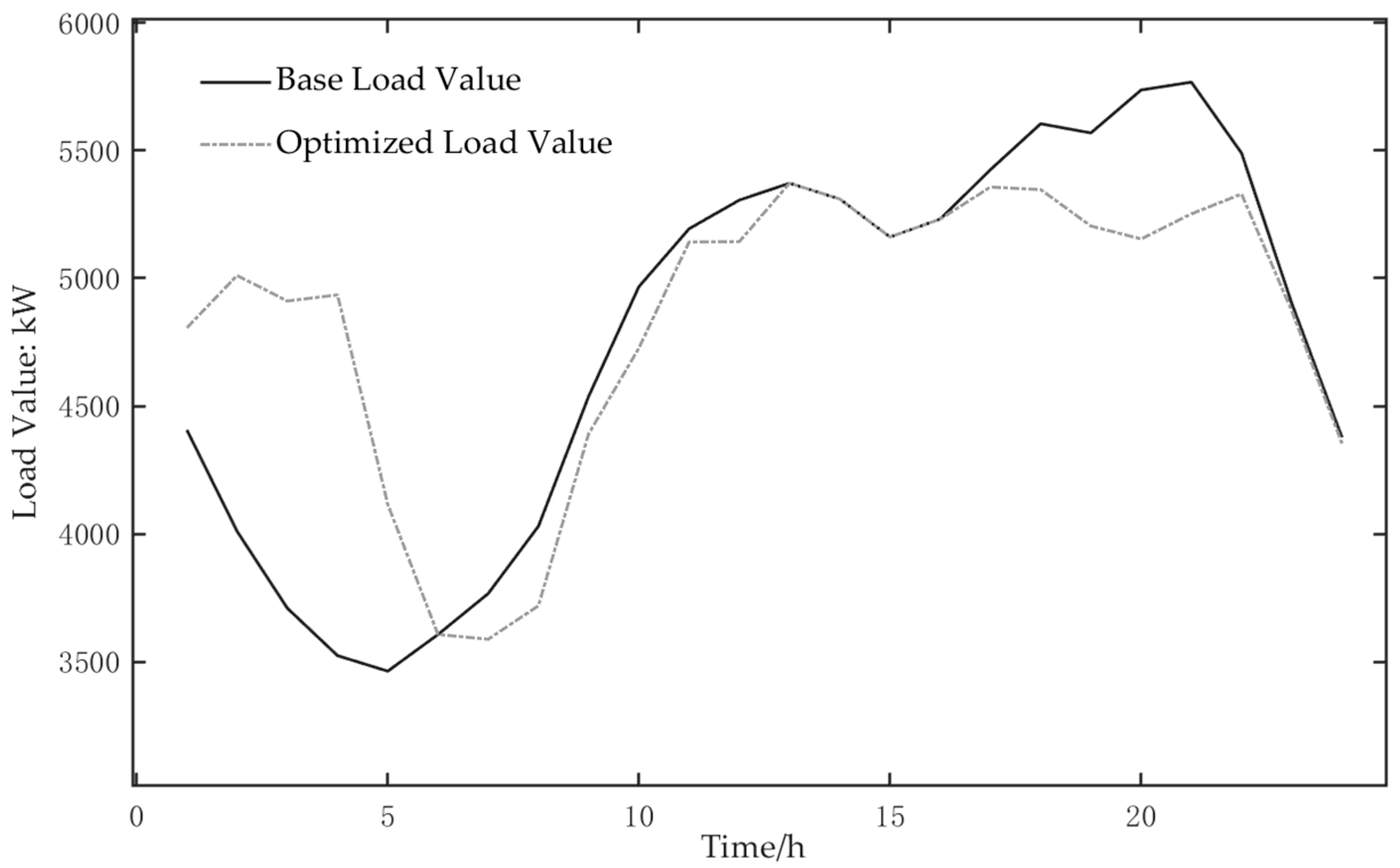

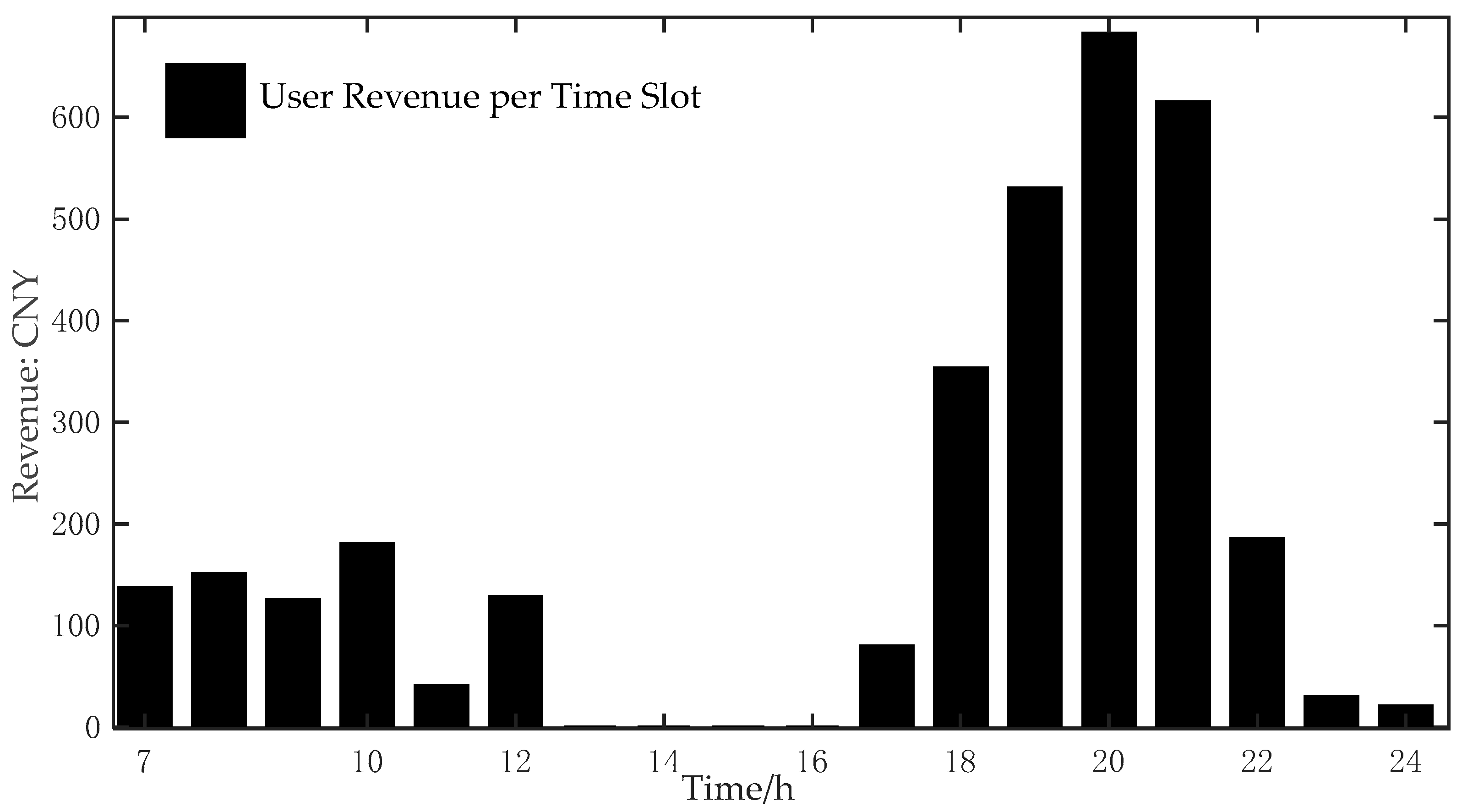

5.2. Analysis of Simulation Results

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under the given scenarios, introducing V2G and optimizing charging/discharging periods and power levels smooths the daily load profile to a noticeable extent. The daily peak–valley difference of the base load is reduced from 2302.75 kW to 1782.82 kW (a reduction of about 22.6%), and the daily load variance decreases by approximately 46.5%, while the total daily energy remains essentially unchanged. This corresponds to the expected peak-shaving and valley-filling effect.

- (2)

- The initial SOC distribution and the fleet SOH composition influence the available flexibility and the achievable peak-shaving performance. In the numerical example, the reduction in the peak–valley difference was about 23.7% in the high-SOC scenario and about 14.8% in the low-SOC scenario. Across different SOH scenarios, a higher proportion of high-SOH batteries leads to slightly lower peak loads and better peak shaving, whereas fleets dominated by lower-SOH batteries show weaker peak reduction but still maintain a clear load-smoothing effect.

- (3)

- Incorporating the SOH and equivalent cycle count into the incentive tariff allows battery degradation cost to be directly reflected in the user-side compensation, linking economic returns more closely to battery usage intensity. For the 50-EV fleet in the 24 h case study, the total charging cost was about CNY 2368.86 and the total discharging revenue was about CNY 3259.58, resulting in a positive net benefit, while the SOC constraints prevented deep discharges and ensured that subsequent travel demands were met. The results indicate that high-SOH vehicles achieve higher individual revenues, whereas low-SOH vehicles are more strongly constrained by capacity and lifetime limits. But, at the fleet level, it is still possible to obtain both economic benefits and a useful contribution to load regulation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dik, A.; Omer, S.; Boukhanouf, R. Electric vehicles: V2G for rapid, safe, and green EV penetration. Energies 2022, 15, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tan, Y.; Liu, X.; Liao, Q.; Sun, B.; Cao, G.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. A cost-benefit analysis of V2G electric vehicles supporting peak shaving in Shanghai. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 179, 106058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, S. Potential regulation ability and economy analysis of auxiliary service by V2G: Taking Shanghai area for an example. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2021, 41, 105–141. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Shao, Z.; Jian, L. The peak load shaving assessment of developing a user-oriented vehicle-to-grid scheme with multiple operation modes: The case study of Shenzhen, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecchino, A.; Prostejovsky, A.M.; Ziras, C.; Marinelli, M. Large-scale provision of frequency control via V2G: The Bornholm power system case. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2019, 170, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Yang, J.; Xiao, J.; Xu, B.; Liu, W.; Li, Y. A frequency control strategy for multimicrogrids with V2G based on the improved robust model predictive control. Energy 2021, 222, 119963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, R.; Guo, H.; Zheng, K.; Sun, M.; Chen, Q. Co-optimizing bidding and power allocation of an EV aggregator providing real-time frequency regulation service. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 4594–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ye, C.; Ding, Y.; Tang, J.; Liu, S. A distributed MPC to exploit reactive power V2G for real-time voltage regulation in distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 13, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amamra, S.A.; Marco, J. Vehicle-to-grid aggregator to support power grid and reduce electric vehicle charging cost. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 178528–178538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yuan, M.; Jiao, X. Electric vehicle charging and discharging scheduling strategy based on dynamic electricity price. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.P.; Singh, M. Time-of-Use tariff rates estimation for optimal demand-side management using electric vehicles. Energy 2023, 273, 127243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Shen, X.; Liang, P.; Ding, L.; Yan, J.; Xing, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Spatial–temporal optimal pricing for charging stations: A model-driven approach based on group price response behavior of EVs. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 8869–8880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lu, L.; Xiang, Y. Coordinated scheduling strategy of electric vehicles for peak shaving considering V2G price incentive. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2022, 42, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Manzolli, J.A.; Trovao, J.P.; Antunes, C.H. Electric bus coordinated charging strategy considering V2G and battery degradation. Energy 2022, 254, 124252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, S.; Nizami, M.S.; Irshad, U.B.; Hossain, M.J.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C. A two-stage multi-objective stochastic optimization strategy to minimize cost for electric bus depot operators. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 129856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qi, J.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Wei, H. EV dispatch control for supplementary frequency regulation considering the expectation of EV owners. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 9, 3763–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, F. An urban charging load forecasting model based on trip chain model for private passenger electric vehicles: A case study in Beijing. Energy 2024, 299, 130844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Tao, S.; Xiao, X.; Luo, C.; Liao, K. Analysis on charging demand of EV based on stochastic simulation of trip chain. Power Syst. Technol. 2015, 39, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Du, Z.; Chen, L.; Guan, L.; Zhou, B. Trip simulation based charging load forecasting model and vehicle-to-grid evaluation of electric vehicles. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 43, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Lee, Z.; Li, G. A calculation model of charge and discharge capacity of electric vehicle cluster based on trip chain. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 142026–142042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Coignard, J.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, C.; Saxena, S. Quantifying electric vehicle battery degradation from driving vs. vehicle-to-grid services. J. Power Sources 2016, 332, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, M.; Prada, E.; Sauvant-Moynot, V. Development of an empirical aging model for Li-ion batteries and application to assess the impact of Vehicle-to-Grid strategies on battery lifetime. Appl. Energy 2016, 172, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Deng, X.; Yue, H.; Sun, T.; Liu, Z. Coordinated Optimization Strategy of Electric Vehicle Cluster Participating in Energy and Frequency Regulation Markets Considering Battery Lifetime Degradation. Diangong Jishu Xuebao/Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2022, 37, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Guo, P.; Wu, Z.; Du, J. Vehicle–Grid Interaction Pricing Optimization Considering Travel Probability and Battery Degradation to Minimize Community Peak–Valley Load. Batteries 2025, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudeja, C.; Kumar, P. An improved weighted sum-fuzzy Dijkstra’s algorithm for shortest path problem (iWSFDA). Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 3217–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, A.M. Promising cathode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries: A review. J. Sustain. Energy 2023, 14, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- An, F.Q.; Zhao, H.L.; Cheng, Z.; Qiu Ji, Y.C.; Zhou, W.N.; LI, P. Development status and research progress of power battery for pure electric vehicles. Chin. J. Eng. 2019, 41, 22–42. [Google Scholar]

| Road Section | Road Length/km | Road Section | Road Length/km | Road Section | Road Length/km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, 2 | 7.60 | 4, 11 | 6.54 | 7, 13 | 3.62 |

| 1, 8 | 7.85 | 4, 14 | 8.76 | 7, 14 | 7.10 |

| 1, 9 | 4.08 | 4, 15 | 3.83 | 7, 16 | 3.17 |

| 1, 15 | 3.88 | 4, 16 | 6.72 | 8, 9 | 5.87 |

| 2, 3 | 3.30 | 5, 6 | 9.26 | 9, 10 | 7.48 |

| 2, 10 | 8.82 | 5, 8 | 9.54 | 9, 12 | 8.15 |

| 2, 15 | 3.27 | 5, 12 | 4.21 | 10, 11 | 8.07 |

| 3, 4 | 8.41 | 5, 16 | 3.12 | 10, 13 | 4.79 |

| 3, 11 | 7.81 | 6, 7 | 8.80 | 11, 14 | 9.23 |

| 3, 15 | 3.30 | 6, 12 | 8.80 | 12, 13 | 7.52 |

| 4, 7 | 4.59 | 6, 16 | 2.20 | 13, 14 | 9.73 |

| Symbol | Meaning | Unit/Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Incentive tariff for EV | CNY/kWh | |

| Base electricity tariff (time-of-use price) for EV | CNY/kWh | |

| Load–pressure compensation coefficient | – | |

| Battery compensation coefficient for EV i | – | |

| Real-time grid load in interval t | kW | |

| Baseline/control load for peak shaving | kW | |

| Peak-shaving demand price compensation factor | – | |

| State of health of EV i | – | |

| Accumulated equivalent cycle count of EV i | – | |

| Weighting factor for health-related compensation | – | |

| Weighting factor for cycle-related compensation | – | |

| Saturation exponent of the cycle compensation term | – |

| Algorithm | T/s | Maximum Number of Iterations | Final Objective J |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO-QP (proposed) | 1.88 | 115 | 0.517 |

| Single-layer PSO (baseline) | 3.06 | 260 | 0.530 |

| Time Slot | Electricity Price (CNY/kWh) | |

|---|---|---|

| Off-Peak Hours | 0:00–6:00, 12:00–14:00 | 0.4 |

| Shoulder Hours | 6:00–12:00, 14:00–16:00 | 0.65 |

| On-Peak Hours | 16:00–18:00, 20:00–24:00 | 0.88 |

| Super-Peak Hours | 18:00–20:00 | 1.02 |

| Indicator | Base Load | With V2G Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Peak–valley difference ΔP (kW) | 2302.75 | 1782.82 (−22.6%) |

| Daily load variance (kW2) | (−46.5%) | |

| 24 h charging cost (CNY) | - | 2368.86 |

| 24 h discharging revenue (CNY) | - | 3259.58 |

| Net user benefit (CNY) | - | 890.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Xu, Z. The Research on V2G Grid Optimization and Incentive Pricing Considering Battery Health. Energies 2025, 18, 6450. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246450

Chen J, Xu Z. The Research on V2G Grid Optimization and Incentive Pricing Considering Battery Health. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6450. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246450

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jianghong, and Ziyong Xu. 2025. "The Research on V2G Grid Optimization and Incentive Pricing Considering Battery Health" Energies 18, no. 24: 6450. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246450

APA StyleChen, J., & Xu, Z. (2025). The Research on V2G Grid Optimization and Incentive Pricing Considering Battery Health. Energies, 18(24), 6450. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246450